The history of the area that is now the

U.S. state of Louisiana, can be traced back thousands of years to when it was occupied by

indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

. The first indications of permanent settlement, ushering in the

Archaic period, appear about 5,500 years ago. The area that is now Louisiana formed part of the

Eastern Agricultural Complex. The

Marksville culture

The Marksville culture was an archaeological culture in the lower Lower Mississippi valley, Yazoo valley, and Tensas valley areas of present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and extended eastward along the Gulf Coast to the Mobile Bay are ...

emerged about 2,000 years ago out of the earlier

Tchefuncte culture. It is considered ancestral to the

Natchez and

Taensa peoples. Around the year 800 AD, the

Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from approximately 800 CE to 1600 CE, varying regionally. It was known for building large, eart ...

emerged from the

Woodland period

In the classification of archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 BCE to European contact in the eastern part of North America, with some archaeo ...

. The emergence of the

Southeastern Ceremonial Complex coincides with the adoption of

maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

agriculture and

chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

-level complex social organization beginning in circa 1200 AD. The Mississippian culture mostly disappeared around the 16th century, with the exception of some Natchez communities that maintained Mississippian cultural practices into the 1700s.

European influence began in the 1500s, and ''

La Louisiane'' (named after

Louis XIV of France

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of ...

) became a colony of the

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

in 1682, before

passing to Spain in 1763. Louisiana was formed in part of the became part of the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or ap ...

from

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

in 1803. The U.S. would divide that area into two territories, the

Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 180 ...

, which formed what would become the boundaries of Louisiana, and the

District of Louisiana. Louisiana was admitted as the 18th state of the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country Continental United States, primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 U.S. state, states, a Washington, D.C., ...

on April 30, 1812. The final major battle in the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, the

Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815 between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

, was fought in Louisiana and resulted in a U.S. victory.

Antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ar ...

Louisiana was a leading

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

, where by 1860, 47% of the population was enslaved. Louisiana seceded from the

Union on 26 January 1861, joining the

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

.

, the largest city in the entire

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

at the time, and strategically important port city, was taken by

Union troops on 25 April 1862. After the defeat of the

Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighti ...

in 1865, Louisiana would enter the

Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in American history following the American Civil War (1861–1865) and lasting until approximately the Compromise of 1877. During Reconstruction, attempts were made to rebuild the country after the bloo ...

(1865–1877). During Reconstruction, Louisiana was subject to

U.S. Army occupation, as part of the

Fifth Military District.

Following Reconstruction in the 1870s, white Democrats had regained political control in the state. In 1896, the

U.S. Supreme Court decision in the ''

Plessy v. Ferguson'' case ruled that "separate but equal" facilities were constitutional. The lawsuit stemmed from 1892 when

Homer Plessy

Homer Adolph Plessy (born Homère Patris Plessy; 1862 or March 17, 1863 – March 1, 1925) was an American shoemaker and activist, best known as the plaintiff in the United States Supreme Court decision ''Plessy v. Ferguson''. He staged an act o ...

, a mixed-race resident of New Orleans, violated Louisiana's Separate Car Act of 1890, which required "equal, but separate" railroad accommodations for white and non-white passengers. This court decision upheld

Jim Crow laws

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws enforcing racial segregation in the Southern United States. Other areas of the United States were affected by formal and informal policies of segregation as well, but many states outside the S ...

that had started to form in the 1870s. In 1898, white Democrats in the Louisiana state legislature passed a new

disfranchising constitution, whose effects were immediate and long-lasting. The disfranchisement of African Americans in the state did not end until national legislation passed during the

Civil Rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional racial segregation, discrimination, and disenfranchisement throughout the Unite ...

in the 1960s.

In the early-to-mid 20th century, many African Americans would leave the state in the

Great Migration. They moved to mainly urban areas in the North and Midwest. The

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s would hit the states economy hard, as mostly agricultural state at the time, farm prices had dropped to all-time lows. In the states urban areas such as New Orleans, many warehouses and businesses had closed, leaving many unemployed. The

Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progress Admi ...

would help flow money into the state, providing employment opportunities for Louisiana projects.

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

would help accelerate the industrialization of Louisiana's economy and provide further economic growth. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Civil Rights movement had started to gain national attention, and with the passing of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin. It prohibits unequal application of voter registration requi ...

and

Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights m ...

, disfranchisement of African Americans in the state had ended.

In the late

20th Century

The 20th (twentieth) century began on

January 1, 1901 ( MCMI), and ended on December 31, 2000 ( MM). The 20th century was dominated by significant events that defined the modern era: Spanish flu pandemic, World War I and World War II, nucle ...

, Louisiana saw rapid industrialization and rise of economic markets such as oil refineries, petrochemical plants, foundries, along with industries of produce foods, fishing, transportation equipment, and electronic equipment. Tourism also became important to the Louisiana economy, with

Mardi Gras

Mardi Gras (, ) refers to events of the Carnival celebration, beginning on or after the Christian feasts of the Epiphany (Three Kings Day) and culminating on the day before Ash Wednesday, which is known as Shrove Tuesday. is French for "Fa ...

becoming a known major celebration held annually since 1838. In 2005,

Hurricane Katrina

Hurricane Katrina was a destructive Category 5 Atlantic hurricane that caused over 1,800 fatalities and $125 billion in damage in late August 2005, especially in the city of New Orleans and the surrounding areas. It was at the time the cost ...

struck Louisiana and surrounding areas in the

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

, resulting in major damages. A $15 billion dollar new

levee

A levee (), dike (American English), dyke (Commonwealth English), embankment, floodbank, or stop bank is a structure that is usually earthen and that often runs parallel to the course of a river in its floodplain or along low-lying coastli ...

system built in New Orleans would take place from 2006 to 2011.

Prehistory

Lithic stage

The

Dalton tradition

The Dalton tradition is a Late Paleo-Indian and Early Archaic projectile point tradition. These points appeared in most of Southeast North America around 10,000–7,500 BC.

:''"They are distinctive artifacts, having concave bases with "ears" ...

is a Late

Paleo-Indian and Early Archaic

projectile point

In North American archaeological terminology, a projectile point is an object that was hafted to a weapon that was capable of being thrown or projected, such as a javelin, dart, or arrow. They are thus different from weapons presumed to have ...

tradition, appearing in much of Southeast North America around 8500–7900 BC.

Archaic period

During the

Archaic period, Louisiana was home to the earliest mound complex in

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and th ...

and one of the earliest dated complex constructions in the Americas. The

Watson Brake site is an arrangement of human-made

mound

A mound is a heaped pile of earth, gravel, sand, rocks, or debris. Most commonly, mounds are earthen formations such as hills and mountains, particularly if they appear artificial. A mound may be any rounded area of topographically highe ...

s located in the floodplain of the

Ouachita River

The Ouachita River ( ) is a river that runs south and east through the U.S. states of Arkansas and Louisiana, joining the Tensas River to form the Black River near Jonesville, Louisiana. It is the 25th-longest river in the United State ...

near

Monroe in northern Louisiana. It has been dated to about 3400 BC. The site appears to have been abandoned about 2800.

By 2200 BC, during the Late Archaic period the

Poverty Point culture occupied much of Louisiana and was spread into several surrounding states. Evidence of this culture has been found at more than 100 sites, including the

Jaketown Site near

Belzoni, Mississippi. The largest and best-known site is near modern-day

Epps, Louisiana at

Poverty Point. The Poverty Point culture may have hit its peak around 1500, making it the first complex culture, and possibly the first tribal culture, not only in the

Mississippi Delta

The Mississippi Delta, also known as the Yazoo–Mississippi Delta, or simply the Delta, is the distinctive northwest section of the U.S. state of Mississippi (and portions of Arkansas and Louisiana) that lies between the Mississippi and Yaz ...

but in the present-day United States. Its people were in villages that extended for nearly 100 miles across the Mississippi River. It lasted until approximately 700 BC.

Woodland period

The Poverty Point culture was followed by the

Tchefuncte and

Lake Cormorant cultures of the

Tchula period The Tchula period is an early period in an archaeological chronology, covering the early development of permanent settlements, agriculture, and large societies.

The Tchula period (800 BCE – 200 CE) encompasses the Tchefuncte and Lake Cormorant ...

, local manifestations of Early

Woodland period

In the classification of archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 BCE to European contact in the eastern part of North America, with some archaeo ...

. These descendant cultures differed from Poverty Point culture in trading over shorter distances, creating less massive public projects, completely adopting ceramics for storage and cooking. The Tchefuncte culture were the first people in Louisiana to make large amounts of pottery. Ceramics from the Tchefuncte culture have been found in sites from eastern Texas to eastern Florida, and from coastal Louisiana to southern Arkansas.

These cultures lasted until 200 AD.

The Middle Woodland period started in Louisiana with the

Marksville culture

The Marksville culture was an archaeological culture in the lower Lower Mississippi valley, Yazoo valley, and Tensas valley areas of present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and extended eastward along the Gulf Coast to the Mobile Bay are ...

in the southern and eastern part of the state

and the

Fourche Maline culture in the northwestern part of the state. The Marksville culture takes its name from the

Marksville Prehistoric Indian Site in

Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. These cultures were contemporaneous with the

Hopewell cultures of

Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

and

Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

, and participated in the Hopewell Exchange Network.

At this time populations became more sedentary and began to establish semi-permanent villages and to practice

agriculture

Agriculture or farming is the practice of cultivating plants and livestock. Agriculture was the key development in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created food surpluses that enabled people ...

,

[ planting various cultigens of the Eastern Agricultural Complex. The populations began to expand, and trade with various non-local peoples also began to increase. Trade with peoples to the southwest brought the bow and ]arrow

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers ...

burial mound

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and objec ...

s are built at this time.[ Political power begins to be consolidated; the first ]platform mound

Platform may refer to:

Technology

* Computing platform, a framework on which applications may be run

* Platform game, a genre of video games

* Car platform, a set of components shared by several vehicle models

* Weapons platform, a system or ...

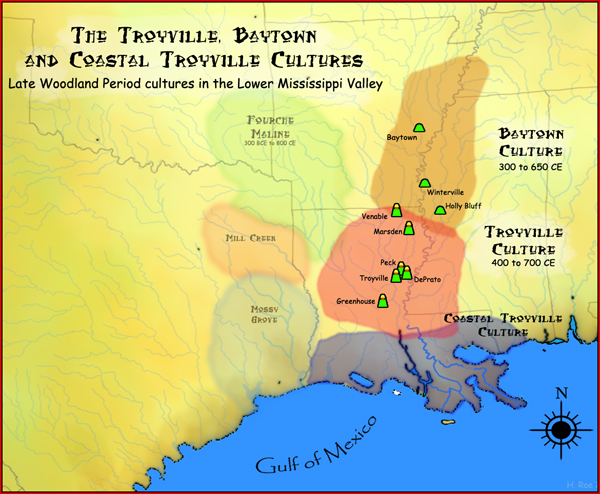

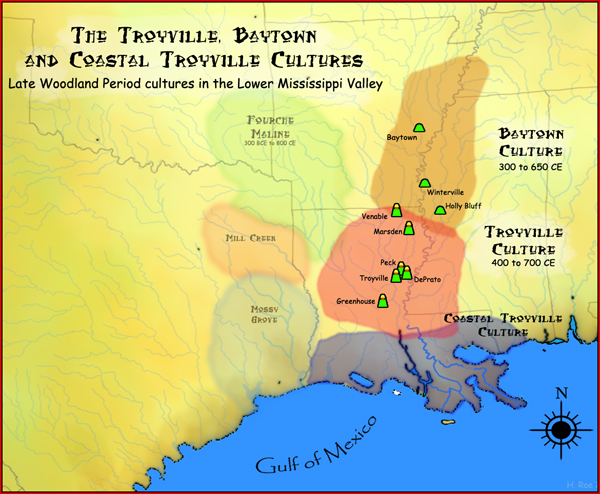

s and ritual centers were constructed as part of the development of a hereditary political and religious leadership. By 400 AD in the eastern part of the state, the Late Woodland period had begun with the Baytown and Troyville cultures (named for the Troyville Earthworks in Jonesville, Louisiana), and later the Coles Creek culture. Archaeologists have traditionally viewed the Late Woodland as a time of cultural decline after the florescence of the Hopewell peoples. Late Woodland sites, with the exception of sites along the Florida Gulf Coast, tend to be small when compared with Middle Woodland sites. Although settlement size was small, there was an increase in the number of Late Woodland sites over Middle Woodland sites, indicating a population increase. These factors tend to mark the Late Woodland period as an expansive period, not one of a cultural collapse. Where the Baytown peoples began to build more dispersed settlements, the Troyville people instead continued building major earthwork centers. The type site for the culture, the Troyville Earthworks, once had the second tallest precolumbian mound in North America and the tallest in Louisiana at in height.

By 400 AD in the eastern part of the state, the Late Woodland period had begun with the Baytown and Troyville cultures (named for the Troyville Earthworks in Jonesville, Louisiana), and later the Coles Creek culture. Archaeologists have traditionally viewed the Late Woodland as a time of cultural decline after the florescence of the Hopewell peoples. Late Woodland sites, with the exception of sites along the Florida Gulf Coast, tend to be small when compared with Middle Woodland sites. Although settlement size was small, there was an increase in the number of Late Woodland sites over Middle Woodland sites, indicating a population increase. These factors tend to mark the Late Woodland period as an expansive period, not one of a cultural collapse. Where the Baytown peoples began to build more dispersed settlements, the Troyville people instead continued building major earthwork centers. The type site for the culture, the Troyville Earthworks, once had the second tallest precolumbian mound in North America and the tallest in Louisiana at in height.chiefdom

A chiefdom is a form of hierarchical political organization in non-industrial societies usually based on kinship, and in which formal leadership is monopolized by the legitimate senior members of select families or 'houses'. These elites form a ...

societies are not yet manifested, by 1000 CE the formation of simple elite polities had begun. Coles Creek sites are found in present-day Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Texas. Many Coles Creek sites were erected over earlier Woodland period mortuary

A morgue or mortuary (in a hospital or elsewhere) is a place used for the storage of human corpses awaiting identification (ID), removal for autopsy, respectful burial, cremation or other methods of disposal. In modern times, corpses have cu ...

mounds, leading researchers to speculate that emerging elites were symbolically and physically appropriating dead ancestors to emphasize and project their own authority.

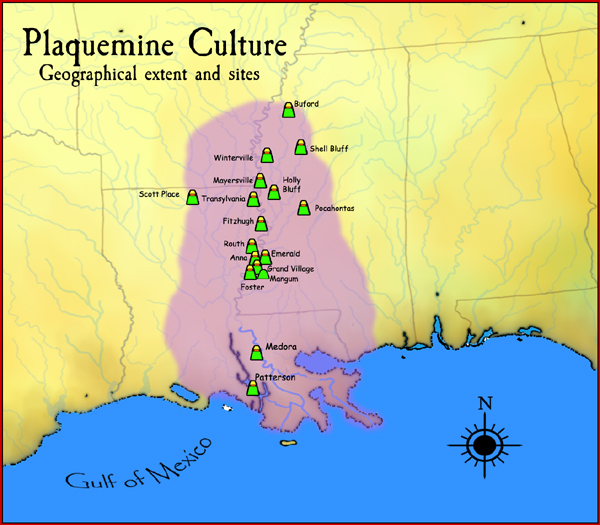

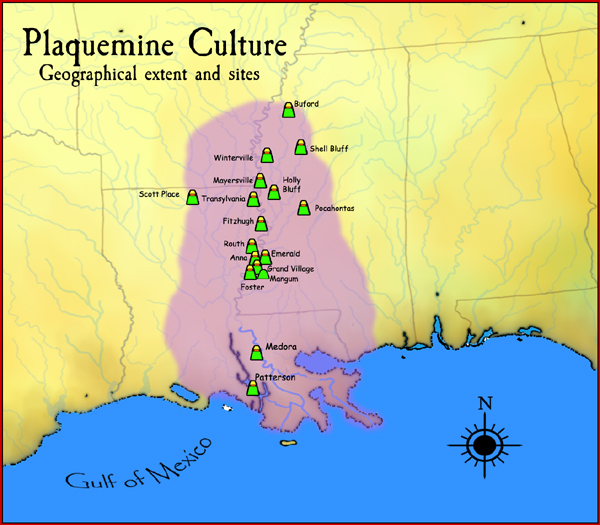

Mississippian period

The

The Mississippian period

The Mississippian ( , also known as Lower Carboniferous or Early Carboniferous) is a subperiod in the geologic timescale or a subsystem of the geologic record. It is the earlier of two subperiods of the Carboniferous period lasting from rough ...

in Louisiana saw the emergence of the Plaquemine and Caddoan Mississippian culture

The Caddoan Mississippian culture was a prehistoric Native American culture considered by archaeologists as a variant of the Mississippian culture. The Caddoan Mississippians covered a large territory, including what is now Eastern Oklahoma, Wes ...

s. This was the period when extensive maize

Maize ( ; ''Zea mays'' subsp. ''mays'', from es, maíz after tnq, mahiz), also known as corn (North American English, North American and Australian English), is a cereal grain first domesticated by indigenous peoples of Mexico, indigenous ...

agriculture was adopted. The Plaquemine culture in the lower Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

Valley in western Mississippi and eastern Louisiana began in 1200 AD and continued until about 1600 AD. Good examples of this culture are the Medora site

The Medora site ( 16WBR1) is an archaeological site that is a type site for the prehistoric Plaquemine culture period. The name for the culture is taken from the proximity of Medora to the town of Plaquemine, Louisiana. The site is in West Bato ...

(the type site

In archaeology, a type site is the site used to define a particular archaeological culture or other typological unit, which is often named after it. For example, discoveries at La Tène and Hallstatt led scholars to divide the European Iron A ...

for the culture and period), Fitzhugh Mounds, Transylvania Mounds, and Scott Place Mounds in Louisiana and the Anna

Anna may refer to:

People Surname and given name

* Anna (name)

Mononym

* Anna the Prophetess, in the Gospel of Luke

* Anna (wife of Artabasdos) (fl. 715–773)

* Anna (daughter of Boris I) (9th–10th century)

* Anna (Anisia) (fl. 1218 to 1221) ...

, Emerald

Emerald is a gemstone and a variety of the mineral beryl (Be3Al2(SiO3)6) colored green by trace amounts of chromium or sometimes vanadium.Hurlbut, Cornelius S. Jr. and Kammerling, Robert C. (1991) ''Gemology'', John Wiley & Sons, New York, p ...

, Winterville and Holly Bluff sites located in Mississippi. Plaquemine culture was contemporaneous with the Middle Mississippian culture at the Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south- ...

site near St. Louis, Missouri. By 1000 AD in the northwestern part of the state the Fourche Maline culture had evolved into the Caddoan Mississippian culture. By 1400 AD Plaquemine had started to hybridize through contact with Middle Mississippian cultures to the north and became what archaeologist term ''Plaquemine Mississippian''. These peoples are considered ancestral to historic groups encountered by the first Europeans in the area, the Natchez and Taensa peoples.Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, and northwest Louisiana. Archaeological evidence that the cultural continuity is unbroken from prehistory to the present, and that the direct ancestors of the Caddo

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, w ...

and related Caddo language speakers in prehistoric times and at first European contact and the modern Caddo Nation of Oklahoma is unquestioned today.

Native groups at time of European settlement

The following groups are known to have inhabited the state's territory when the Europeans began colonization:

* The Choctaw

The Choctaw (in the Choctaw language, Chahta) are a Native American people originally based in the Southeastern Woodlands, in what is now Alabama and Mississippi. Their Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choctaw people are ...

nation ( Muskogean):

** The Bayougoula, in areas directly north of the Chitimachas in the parishes of St. Helena, Tangipahoa, Washington, East Baton Rouge, West Baton Rouge, Livingston, and St. Tammany. They were allied with the Quinipissa-Mougoulacha in St. Tammany parish.

** The Houma in the East and West Feliciana and Pointe Coupee parishes (about 100 miles (160 km) north of the town named for them).

** The Okelousa in Pointe Coupee parish.

** The Acolapissa in St. Tammany parish. They were allied with the Tangipahoa in Tangipahoa parish.

* The Natchez nation:

*** The Avoyel, in parts of Avoyelles and Concordia parishes along the Mississippi River.

*** The Taensa, in northeastern Louisiana particularly Tensas parish.

* The Caddo Confederacy

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, who ...

:

** The Adai in Natchitoches parish

** The Natchitoches confederacy consisting of the Natchitoches in Natchitoches parish

** The Yatasi The Yatasi (Caddo: Yáttasih) are Native American peoples from northwestern Louisiana that are part of the Natchitoches Confederacy of the Caddo Nation. Today they are enrolled in the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma.

History

Prior to European contact, t ...

and Nakasa in the Caddo and Bossier parishes,

** The Doustioni in Natchitoches parish, and Ouachita in the Caldwell parish.

* The Atakapa

The Atakapa Sturtevant, 659 or Atacapa were an indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, who spoke the Atakapa language and historically lived along the Gulf of Mexico in what is now Texas and Louisiana. They included several distinct band ...

in southwestern Louisiana in Vermilion, Cameron, Lafayette, Acadia, Jefferson Davis, and Calcasieu parishes. They were allied with the Appalousa

The Appalousa (also Opelousa) were an indigenous American people who occupied the area around present-day Opelousas, Louisiana, west of the lower Mississippi River, before European contact in the eighteenth century. At various times in their histo ...

in St. Landry parish.

* The Chitimacha in the southeastern parishes of Iberia, Assumption, St. Mary, lower St. Martin, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Charles, Jefferson, Orleans, St. Bernard, and Plaquemines. They were allied with the Washa in Assumption parish, the Chawasha in Terrebonne parish, and the Yagenechito to the east.

* The Tunica in northeastern parishes of Tensas, Madison, East Carroll and West Carroll, and the related Koroa in East Carroll parish.

Many current place names in the state, including Atchafalaya, Natchitouches (now spelled Natchitoches), Caddo

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, w ...

, Houma, Tangipahoa, and Avoyel (as Avoyelles), are transliterations of those used in various Native American languages.

European contact

The first European explorers to visit Louisiana came in 1528 when a Spanish expedition led by Panfilo de Narváez located the mouth of the Mississippi River. In 1542, Hernando de Soto

Hernando de Soto (; ; 1500 – 21 May, 1542) was a Spanish explorer and ''conquistador'' who was involved in expeditions in Nicaragua and the Yucatan Peninsula. He played an important role in Francisco Pizarro's conquest of the Inca Empire ...

's expedition skirted to the north and west of the state (encountering Caddo and Tunica groups) and then followed the Mississippi River down to the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

in 1543. The expedition encountered hostile tribes all along river. Natives followed the boats in large canoes, shooting arrows at the soldiers for days on end as they drifted through their territory. The Spanish, whose crossbows had long ceased working, had no effective offensive weapons on the water and were forced to rely on their remaining armor and sleeping mats to block the arrows. About 11 Spaniards were killed along this stretch and many more wounded. Neither of the explorations made any claims to the territory for Spain.

French exploration and colonization (1682–1763)

European interest in Louisiana was dormant until the late 17th century, when French expeditions, which had imperial, religious and commercial aims, established a foothold on the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast. With its first settlements, France lay claim to a vast region of North America and set out to establish a commercial empire and French nation stretching from the Gulf of Mexico through Canada. It was also establishing settlements in Canada, from the Maritimes westward along the St. Lawrence River and into the region surrounding the Great Lakes

The Great Lakes, also called the Great Lakes of North America, are a series of large interconnected freshwater lakes in the mid-east region of North America that connect to the Atlantic Ocean via the Saint Lawrence River. There are five lakes ...

.

The French explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle named the region Louisiana in 1682 to honor France's King Louis XIV. The first permanent settlement, Fort Maurepas (at what is now Ocean Springs, Mississippi, near Biloxi), was founded in 1699 by

The French explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle named the region Louisiana in 1682 to honor France's King Louis XIV. The first permanent settlement, Fort Maurepas (at what is now Ocean Springs, Mississippi, near Biloxi), was founded in 1699 by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville

Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville (16 July 1661 – 9 July 1706) or Sieur d'Iberville was a French soldier, explorer, colonial administrator, and trader. He is noted for founding the colony of Louisiana in New France. He was born in Montreal to French ...

, a French military officer from Canada.

The French colony of Louisiana originally claimed all the land on both sides of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

and north to French territory in Canada around the Great Lakes. A royal ordinance of 1722—following the transfer of the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

's governance from Canada to Louisiana—may have featured the broadest definition of the region: all land claimed by France south of the Great Lakes between the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico ...

and the AllegheniesDanville, Illinois

Danville is a city in and the county seat of Vermilion County, Illinois. As of the 2010 census, its population was 33,027. As of 2019, the population was an estimated 30,479.

History

The area that is now Danville was once home to the Miami, K ...

); from there, northwest to ''le Rocher'' on the Illinois River

The Illinois River ( mia, Inoka Siipiiwi) is a principal tributary of the Mississippi River and is approximately long. Located in the U.S. state of Illinois, it has a drainage basin of . The Illinois River begins at the confluence of the ...

, and from there west to the mouth of the Rock River (at present day Rock Island, Illinois

Rock Island is a city in and the county seat of Rock Island County, Illinois, United States. The original Rock Island, from which the city name is derived, is now called Arsenal Island. The population was 37,108 at the 2020 census. Located on t ...

).Vincennes

Vincennes (, ) is a commune in the Val-de-Marne department in the eastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the centre of Paris. It is next to but does not include the Château de Vincennes and Bois de Vincennes, which are attache ...

and Peoria were the limit of Louisiana's reach; the outposts at Ouiatenon

Ouiatenon ( mia, waayaahtanonki) was a dwelling place of members of the Wea tribe of Native Americans. The name ''Ouiatenon'', also variously given as ''Ouiatanon'', ''Oujatanon'', ''Ouiatano'' or other similar forms, is a French rendering of ...

(on the upper Wabash near present-day Lafayette, Indiana

Lafayette ( , ) is a city in and the county seat of Tippecanoe County, Indiana, United States, located northwest of Indianapolis and southeast of Chicago. West Lafayette, on the other side of the Wabash River, is home to Purdue University, whi ...

), Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Fort Miamis (near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana

Fort Wayne is a city in and the county seat of Allen County, Indiana, United States. Located in northeastern Indiana, the city is west of the Ohio border and south of the Michigan border. The city's population was 263,886 as of the 2020 Censu ...

) and Prairie du Chien operated as dependencies of Canada.Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

. (Although British forces had established control over the "Canadian" posts in the Illinois and Wabash countries in 1761, they did not have control over Vincennes or the Mississippi River settlements at Cahokia and Kaskaskia until 1764, after the ratification of the peace treaty.Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of t ...

, then commandant at Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, explained in 1762 that, although the boundary between Louisiana and Canada wasn't exact, it was understood the upper Mississippi above the mouth of the Illinois was in Canadian trading territory.fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal ecosystem, boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals h ...

in the northern areas, which became increasingly important. It competed with Dutch, and later English merchants, across the northern tier for fur trade with the Native Americans. The fur trade also helped cement alliances between Europeans and Native American tribes.

The settlement of Natchitoches (along the Red River in present-day northwest Louisiana) was established in 1714 by Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, making it the oldest permanent settlement in the territory that then composed the Louisiana colony. The French settlement had two purposes: to establish trade with the Spanish in

The settlement of Natchitoches (along the Red River in present-day northwest Louisiana) was established in 1714 by Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, making it the oldest permanent settlement in the territory that then composed the Louisiana colony. The French settlement had two purposes: to establish trade with the Spanish in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

via the Old San Antonio Road (sometimes called El Camino Real, or Kings Highway)—which ended at Nachitoches—and to deter Spanish advances into Louisiana. The settlement soon became a flourishing river port and crossroads. Sugar cane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of (often hybrid) tall, perennial grass (in the genus '' Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fibrous stalk ...

plantations were developed first. In the nineteenth century, cotton plantations were developed along the river. Over time, planters developed large plantations but also lived in fine homes in a growing town, a pattern repeated in New Orleans and other places.

Louisiana's French settlements contributed to further exploration and outposts. They were concentrated along the banks of the Mississippi and its major tributaries, from Louisiana to as far north as the region called the Illinois Country

The Illinois Country (french: Pays des Illinois ; , i.e. the Illinois people)—sometimes referred to as Upper Louisiana (french: Haute-Louisiane ; es, Alta Luisiana)—was a vast region of New France claimed in the 1600s in what is n ...

, in modern-day Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Rock ...

and Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

.

Initially Mobile, and (briefly) Biloxi served the capital of the colony. In 1722, recognizing the importance of the Mississippi River to trade and military interests, France made the seat of civilian and military authority. The Illinois Country exported its grain surpluses down the Mississippi to New Orleans, which climate could not support their cultivation. The lower country of Louisiana (modern-day Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana) depended on the Illinois French for survival through much of the eighteenth century.

European settlement in the Louisiana colony was not exclusively French; in the 1720s, German immigrants settled along the Mississippi River in a region referred to as the German Coast.

Africans and early slavery

In 1719, two French ships arrived in New Orleans, the '' Duc du Maine'' and the '' Aurore'', carrying the first African slaves to Louisiana for labor. From 1718 to 1750, traders transported thousands of captive Africans to Louisiana from the Senegambian coast, the west African region of the interior of modern Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the nort ...

, and from the coast of modern Democratic Republic of the Congo

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (french: République démocratique du Congo (RDC), colloquially "La RDC" ), informally Congo-Kinshasa, DR Congo, the DRC, the DROC, or the Congo, and formerly and also colloquially Zaire, is a country in ...

-Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

border. French shipping records, in contrast to those of other European nations, contained extensive details of the origins of enslaved Africans taken onboard slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea coast ...

s. Researchers have found that approximately 2,000 persons originated from the upper West African slave ports from Saint-Louis, Senegal

Saint Louis or Saint-Louis ( wo, Ndar), is the capital of Senegal's Saint-Louis Region. Located in the northwest of Senegal, near the mouth of the Senegal River, and 320 km north of Senegal's capital city Dakar, it has a population officially ...

to Cap Appolonia (present-day Ébrié Lagoon, Côte d'Ivoire

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire, officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital is Yamoussoukro, in the centre of the country, while its largest city and economic centre ...

) several hundred kilometers to the south; an additional 2,000 were exported from the port of Whydah (modern Ouidah

Ouidah () or Whydah (; ''Ouidah'', ''Juida'', and ''Juda'' by the French; ''Ajudá'' by the Portuguese; and ''Fida'' by the Dutch) and known locally as Glexwe, formerly the chief port of the Kingdom of Whydah, is a city on the coast of the Repub ...

, Benin

Benin ( , ; french: Bénin , ff, Benen), officially the Republic of Benin (french: République du Bénin), and formerly Dahomey, is a country in West Africa. It is bordered by Togo to the west, Nigeria to the east, Burkina Faso to the nort ...

); and roughly 300 departed from Cabinda.Gwendolyn Midlo Hall

Gwendolyn Midlo Hall (June 27, 1929 – August 29, 2022) was an American historian who focused on the history of slavery in the Caribbean, Latin America, Louisiana (United States), Africa, and the African Diaspora in the Americas. Discovering ext ...

has argued that, due to historical and administrative ties between France and Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣𞤭 ...

, "Two-thirds of the slaves brought to Louisiana by the French slave trade came from Senegambia." This assertion is not universally accepted. This region between the Senegal and Gambia

The Gambia,, ff, Gammbi, ar, غامبيا officially the Republic of The Gambia, is a country in West Africa. It is the smallest country within mainland AfricaHoare, Ben. (2002) ''The Kingfisher A-Z Encyclopedia'', Kingfisher Publicatio ...

rivers had peoples who were closely related through history: three of the principal languages, Sereer

The Serer people are a West African ethnoreligious group. , Wolof and Pulaar

Pulaar (in Adlam: , in Ajami: ) is a Fula language spoken primarily as a first language by the Fula and Toucouleur peoples in the Senegal River valley area traditionally known as Futa Tooro and further south and east. Pulaar speakers, known a ...

were related, and Malinke, spoken by the Mande people Mande may refer to:

* Mandé peoples of western Africa

* Mande languages

* Manding, a term covering a subgroup of Mande peoples, and sometimes used for one of them, Mandinka

* Garo people of northeastern India and northern Bangladesh

* Mande Rive ...

to the east, was "mutually intelligible" with them. Hall thinks that this concentration of peoples from one region of Africa helped shape the Creole culture in Louisiana.

Peter Caron says that the geographic and perhaps linguistic connection among many African captives did not necessarily imply developing a common culture in Louisiana. They likely differed in religions. Some slaves from Senegambia were Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

while most followed their traditional spiritual practices. Many were likely captives taken in the Islamic jihads that engulfed the region from Futa Djallon to Futa Toro

Futa Toro ( Wolof and ff, Fuuta Tooro ''𞤆𞤵𞥄𞤼𞤢 𞤚𞤮𞥄𞤪𞤮''; ar, فوتا تورو), often simply the Futa, is a semidesert region around the middle run of the Senegal River. This region is along the border of Senegal and ...

and Futa Bundu (modern Upper Niger River

The Niger River ( ; ) is the main river of West Africa, extending about . Its drainage basin is in area. Its source is in the Guinea Highlands in south-eastern Guinea near the Sierra Leone border. It runs in a crescent shape through Mal ...

) in the early 18th century.

Spanish interregnum (1763–1803)

France ceded most of its territory east of the Mississippi to the

France ceded most of its territory east of the Mississippi to the Kingdom of Great Britain

The Kingdom of Great Britain (officially Great Britain) was a sovereign country in Western Europe from 1 May 1707 to the end of 31 December 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, wh ...

after its defeat in the Seven Years' War. The area around and the parishes around Lake Pontchartrain

Lake Pontchartrain ( ) is an estuary located in southeastern Louisiana in the United States. It covers an area of with an average depth of . Some shipping channels are kept deeper through dredging. It is roughly oval in shape, about from w ...

, along with the rest of Louisiana, became a possession of Spain after the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754 ...

by the Treaty of Paris of 1763.

Spanish rule did not affect the pace of francophone immigration to the territory, which increased due to the expulsion of the Acadians

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

. Several thousand French-speaking refugees from Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17th and earl ...

(now Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, Canada) migrated to colonial Louisiana. The first group of around 200 arrived in 1765, led by Joseph Broussard

Joseph Broussard (1702–1765), also known as Beausoleil ( en, Beautiful Sun), was a leader of the Acadian people in Acadia; later Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick. Broussard organized a Mi'kmaq and Acadian militias against th ...

(also referrerd to as "Beausoleil"). They settled chiefly in the southwestern Louisiana region now called Acadiana

Acadiana (French and Louisiana French: ''L'Acadiane''), also known as the Cajun Country ( Louisiana French: ''Le Pays Cadjin'', es, País Cajún), is the official name given to the French Louisiana region that has historically contained ...

. The Acadian refugees were welcomed by the Spanish as additions of Catholic population. Their white descendants came to be called Cajun

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana ''Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

While Cajuns are usually described as ...

s and their black descendants, mixed with African ancestry came to be called Creole. Additionally, some Creole Louisianians also have Native American and/or Spanish ancestry.

Many Spanish-speaking immigrants arrived such as the Canary Islanders of Spain, which are known as the Isleños and Andalusians from the south of Spain called Malagueños. The Isleños and Malagueños immigrated to Louisiana between 1778 and 1783. The Isleños settled in southeast Louisiana mainly in St. Bernard Parish, just outside of New Orleans, as well as near the area just below Baton Rouge. The Malagueños settled mainly around New Iberia, but some spread to other parts of southern Louisiana.

Both free and enslaved populations increased rapidly during the years of Spanish rule, as new settlers and Creoles imported large numbers of slaves to work on plantations. Although some American settlers brought slaves with them who were native to Virginia or North Carolina, the Pointe Coupee inventories of the late eighteenth century showed that most slaves brought by traders came directly from Africa. In 1763 settlements from New Orleans to Pointe Coupee (north of Baton Rouge) included 3,654 free persons and 4,598 slaves. By the 1800 census, which included West Florida, there were 19,852 free persons and 24,264 slaves in Lower Louisiana. Although the censuses do not always cover the same territory, the slaves became the majority of the population during these years. Records during Spanish rule were not as well documented as with the French slave trade, making it difficult to trace African origins. The volume of slaves imported from Africa resulted in what historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall

Gwendolyn Midlo Hall (June 27, 1929 – August 29, 2022) was an American historian who focused on the history of slavery in the Caribbean, Latin America, Louisiana (United States), Africa, and the African Diaspora in the Americas. Discovering ext ...

called "the re-Africanization" of Lower Louisiana, which strongly influenced the culture.

In 1800, France's Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

reacquired Louisiana from Spain in the Treaty of San Ildefonso, an arrangement kept secret for some two years. Documents have revealed that he harbored secret ambitions to reconstruct a large colonial empire in the Americas

The Americas, which are sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North and South America. The Americas make up most of the land in Earth's Western Hemisphere and comprise the New World.

Along with th ...

. This notion faltered, however, after the French attempt to reconquer Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1804. The name derives from the Spanish main city in the island, Santo Domingo, which came to ref ...

after its revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

ended in failure, with the loss of two-thirds of the more than 20,000 troops sent to the island to suppress the revolution. After French withdrawal in 1803, Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and s ...

declared its independence in 1804 as the second republic in the Western Hemisphere

The Western Hemisphere is the half of the planet Earth that lies west of the prime meridian (which crosses Greenwich, London, United Kingdom) and east of the antimeridian. The other half is called the Eastern Hemisphere. Politically, the te ...

.

Incorporation into the United States and antebellum years (1803–1860)

As a result of his setbacks, Napoleon gave up his dreams of American empire and sold

As a result of his setbacks, Napoleon gave up his dreams of American empire and sold Louisiana (New France)

Louisiana (french: La Louisiane; ''La Louisiane Française'') or French Louisiana was an administrative district of New France. Under French control from 1682 to 1769 and 1801 (nominally) to 1803, the area was named in honor of King Louis XIV, ...

to the United States. The U.S. divided the land into two territories: the Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 180 ...

, which became the state of Louisiana in 1812, and the District of Louisiana, which consisted of the vast lands not included in the Orleans Territory, extending west of the Mississippi River north to Canada. The Florida Parishes

The Florida Parishes ( es, Parroquias de Florida, french: Paroisses de Floride), on the east side of the Mississippi River—an area also known as the Northshore or Northlake region—are eight List of parishes in Louisiana, parishes in the southe ...

were annexed from the short-lived and strategically important Republic of West Florida

The Republic of West Florida ( es, República de Florida Occidental, french: République de Floride occidentale), officially the State of Florida, was a short-lived republic in the western region of Spanish West Florida for just over months ...

, by proclamation of President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

in 1810.

The Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution (french: révolution haïtienne ; ht, revolisyon ayisyen) was a successful insurrection by self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolt began on ...

(1791-1804) resulted in a major emigration of refugees to Louisiana, where they settled chiefly in New Orleans. Thousands of Saint Dominican refugees arrived to Louisiana, which included Creoles of color

The Creoles of color are a historic ethnic group of Creole people that developed in the former French and Spanish colonies of Louisiana (especially in the city of New Orleans), Mississippi, Alabama, and Northwestern Florida i.e. Pensacola, Flor ...

, white Creoles, and slaves. Some refugees had earlier gone to Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

, and were expelled from Cuba in another wave of immigration in 1809. The Saint Dominicans increased the Creole community of New Orleans substantionally, enlarging the French-speaking

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in No ...

community.

In 1811, the largest slave revolt

A slave rebellion is an armed uprising by enslaved people, as a way of fighting for their freedom. Rebellions of enslaved people have occurred in nearly all societies that practice slavery or have practiced slavery in the past. A desire for freed ...

in American history, the German Coast Uprising, took place in the Orleans Territory. Between 64 and 500 slaves rose up on the " German Coast," forty miles upriver of New Orleans, and marched to within of the city gates. All of the limited number of U.S. troops were gathered to suppress the revolt, as well as citizen militias.

U.S. statehood

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is bord ...

became a U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

on April 30, 1812. The western boundary of Louisiana with Spanish Texas remained in dispute until the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, which was formally ratified in 1821, The area referred to as the Sabine Free State served as a neutral buffer zone.

With the growth of settlement in the Midwest (formerly the Northwest Territory) and Deep South during the early decades of the 19th century, trade and shipping increased markedly in New Orleans. Produce and products moved out of the Midwest down the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the List of longest rivers of the United States (by main stem), second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest Drainage system (geomorphology), drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson B ...

for shipment overseas, and international ships docked at New Orleans with imports to send into the interior. The port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as H ...

was crowded with steamboat

A steamboat is a boat that is marine propulsion, propelled primarily by marine steam engine, steam power, typically driving propellers or Paddle steamer, paddlewheels. Steamboats sometimes use the ship prefix, prefix designation SS, S.S. or S/S ...

s, flatboats

A flatboat (or broadhorn) was a rectangular flat-bottomed boat with square ends used to transport freight and passengers on inland waterways in the United States. The flatboat could be any size, but essentially it was a large, sturdy tub with a ...

, and sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing square-rigged or fore-and-aft sails. Some ships ...

s, and workers speaking languages from many nations. New Orleans was the major port for the export of cotton and sugar. The city's population grew and the region became quite wealthy. More than the rest of the Deep South, it attracted immigrants for the many jobs in the city. The richest citizens imported fine goods of wine, furnishings, and fabrics.

By 1840 New Orleans had the biggest slave market in the United States, which contributed greatly to the economy. It had become one of the wealthiest cities and the third-largest city in the nation. The ban on importation of slaves had increased demand in the domestic market. During these decades after the American Revolutionary War, more than one million enslaved African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

underwent forced migration

Forced displacement (also forced migration) is an involuntary or coerced movement of a person or people away from their home or home region. The UNHCR defines 'forced displacement' as follows: displaced "as a result of persecution, conflict, g ...

from the Upper South

The Upland South and Upper South are two overlapping cultural and geographic subregions in the inland part of the Southern and lower Midwestern United States. They differ from the Deep South and Atlantic coastal plain by terrain, history, econom ...

to the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion in the Southern United States. The term was first used to describe the states most dependent on plantations and slavery prior to the American Civil War. Following the wa ...

, two thirds of them in the slave trade. Others were transported by slaveholders as they moved west for new lands.

With changing agriculture in the Upper South as planters shifted from tobacco to less labor-intensive mixed agriculture, planters had excess laborers. Many sold slaves to traders to take to the Deep South. Slaves were driven by traders overland from the Upper South or transported to New Orleans and other coastal markets by ship in the coastwise slave trade

The coastwise slave trade existed along the eastern coastal areas of the United States in the antebellum years prior to 1861. Shiploads and boatloads of slaves in the domestic trade were transported from place to place on the waterways. Hundreds o ...

. After sales in New Orleans, steamboats operating on the Mississippi transported slaves upstream to markets or plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

destinations at Natchez and Memphis.

Secession and the American Civil War (1860–1865)

With its plantation economy, Louisiana was a state that generated wealth from the labor of and trade in enslaved Africans. It also had one of the largest free black populations in the United States, totaling 18,647 people in 1860. Most of the free blacks (or

With its plantation economy, Louisiana was a state that generated wealth from the labor of and trade in enslaved Africans. It also had one of the largest free black populations in the United States, totaling 18,647 people in 1860. Most of the free blacks (or free people of color

In the context of the history of slavery in the Americas, free people of color (French: ''gens de couleur libres''; Spanish: ''gente de color libre'') were primarily people of mixed African, European, and Native American descent who were not ...

, as they were called in the French tradition) lived in the New Orleans region and southern part of the state. More than in other areas of the South, most of the free people of color were of mixed race. Many '' gens de couleur libre'' in New Orleans were middle class and educated; many were also property owners. In contrast, according to the 1860 census, 331,726 people were enslaved, nearly 47% of the state's total population of 708,002.

Construction and elaboration of the levee system was critical to the state's ability to cultivate its commodity crops of cotton and sugar cane. Enslaved Africans built the first levees under planter direction. Later levees were expanded, heightened and added to mostly by Irish immigrant laborers, whom contractors hired when doing work for the state. As the 19th century progressed, the state had an interest in ensuring levee construction. By 1860, Louisiana had built of levees on the Mississippi River and another of levees on its outlets. These immense earthworks were built mostly by hand. They averaged six feet in height, and up to twenty feet in some areas.

Enfranchised elite whites' strong economic interest in maintaining the slave system contributed to Louisiana's decision to secede from the Union in 1861. It followed other Southern states in seceding after the election of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

as President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

. Louisiana's secession was announced on January 26, 1861, and it became part of the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

.

The state was quickly overtaken by Union troops in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, a result of Union strategy to cut the Confederacy in two by seizing the Mississippi. Federal troops captured New Orleans on April 25, 1862. Due to a large enough portion of the population having Union sympathies (or compatible commercial interests), the Federal government took the unusual step of designating the areas of Louisiana under Federal control as a state within the Union, with its own elected representatives to the U.S. Congress.

Twentieth century

Reconstruction, disenfranchisement, and segregation (1865–1929)

In the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War, many Confederates regained public office. Legislature across the South passed Black Codes

The Black Codes, sometimes called the Black Laws, were laws which governed the conduct of African Americans (free and freed blacks). In 1832, James Kent wrote that "in most of the United States, there is a distinction in respect to political p ...

that restricted the rights of freedmen, such as the right to travel, and forced them to sign year-long contracts with planters. Anyone without proof of a contract by the start of the year was considered a vagrant and could be arrested, imprisoned, and leased out to work through the convict leasing

Convict leasing was a system of forced penal labor which was practiced historically in the Southern United States, the laborers being mainly African-American men; it was ended during the 20th century. (Convict labor in general continues; f ...

system that discriminated against Blacks. With the passage of the Reconstruction Acts, Congress took control of Reconstruction and the South, excluding Tennessee, was placed under the supervision of military governors under congressional control. Louisiana was grouped with Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

in what was administered as the Fifth Military District. Congress dictated that for reentry into the Union, the late rebel state would have to ratify the 14th Amendment and pass new constitutions that enfranchised the freedmen. Louisiana's 1868 Constitution abolished the Black Codes, granted full civil and political equality to freedmen, disenfranchised several classes of ex-Confederates, and included the state's first formal bill of rights. African Americans began to live as citizens with some measure of equality before the law. Both freedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom ...

and people of color who had been free before the war began to make more advances in education, family stability and jobs. At the same time, there was tremendous social volatility in the aftermath of war, with many whites actively resisting defeat. White insurgents

An insurgency is a violent, armed rebellion against authority waged by small, lightly armed bands who practice guerrilla warfare from primarily rural base areas. The key descriptive feature of insurgency is its asymmetric nature: small irr ...

mobilized to enforce white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

, first in Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

chapters.

In the 1870s, whites accelerated their insurgency to regain control of political power in the state. The Red River area, where new parishes had been created by the Reconstruction legislature, was an area of conflict. On Easter Sunday 1873, an estimated 85 to more than 100 blacks were killed in the Colfax massacre, as white militias had gathered to challenge Republican officeholders after the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872.

Paramilitary groups

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units car ...

such as the White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

, formed in 1874, used violence and outright assassination to turn Republicans out of office, and intimidate African Americans and suppress black voting, control their work, and limit geographic movement in an effort to control labor. Among violent acts attributed to the White League in 1874 was the Coushatta massacre, where they killed six Republican officeholders, including four family members of the local state senator, and twenty freedmen as witnesses.

Later, 5,000 White Leaguers battled 3,500 members of the Metropolitan Police and state militia in New Orleans after demanding the resignation of Governor William Pitt Kellogg. They hoped to replace him with the Democratic candidate of the disputed 1872 elections, John McEnery

John McEnery (1 November 1943 – 12 April 2019) was an English actor and writer.

Born in Birmingham, he trained (1962–1964) at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School, playing, among others, Mosca in Ben Jonson's ''Volpone'' and Gaveston ...

. The White League briefly took over the statehouse and city hall before Federal troops arrived. In 1876, the white Democrats regained control of Louisiana.

Through the 1880s, white Democrats began to reduce voter registration of blacks and poor whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

by making registration and elections more complicated. They imposed institutionalized forms of racial discrimination and also conducted voter intimidation and violence against black Republicans. The rate of lynchings of blacks increased through the century, reaching a peak in the late 1800s, but with lynchings continuing well into the 20th century. Blacks came out in force in the April 1896 elections, in areas where they could freely vote, to support a Republican-Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term develop ...

fusion ticket that might overturn the conservative Democrats. Blacks were threatened by increasing talk about restricting their vote, and Mississippi had already passed a new constitution in 1890 that disenfranchised most blacks. Racial tensions and violence were high, and there were 21 lynchings of blacks in Louisiana that year, surpassing the total for any state. Returns from Democratic-controlled plantation parishes were doctored, and the Democrats won the race. The legislature "refused to investigate what everyone knew was a stolen election."[William Ivy Hair, ''Carnival of Fury: Robert Charles and the New Orleans Race Riot of 1900''](_blank)

LSU Press, 2008, pp. 104-105

In 1898, the white Democratic, planter-dominated legislature passed a new disenfranchising constitution, with provisions for voter registration, such as poll taxes, residency requirements and literacy tests

A literacy test assesses a person's literacy skills: their ability to read and write have been administered by various governments, particularly to immigrants. In the United States, between the 1850s and 1960s, literacy tests were administered t ...

, to raise barriers to black voter registration, as Mississippi had successfully done. The effect was immediate and long lasting. In 1896, there were 130,334 black voters on the rolls and about the same number of white voters, in proportion to the state population, which was evenly divided.

The state population in 1900 was 47% African-American: 652,013 citizens, of whom many in New Orleans were descendants of Creoles of color