The history of Italy covers the

ancient period

Ancient history is a time period from the beginning of writing and recorded human history to as far as late antiquity. The span of recorded history is roughly 5,000 years, beginning with the Sumerian cuneiform script. Ancient history cove ...

, the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

, and the

modern era

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is appli ...

. Since

classical antiquity

Classical antiquity (also the classical era, classical period or classical age) is the period of cultural history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD centred on the Mediterranean Sea, comprising the interlocking civilizations of ...

, ancient

Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

, various

Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the Indo-European speaking peoples who inhabited Italy from at lea ...

(such as the

Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

,

Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they f ...

, and

Umbri

The Umbri were an Italic people of ancient Italy. A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the ancient Umbria.

Most ancient Umbrian cities were settled in the 9th-4th centuries BC on ...

),

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

, ''

Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; the ...

'' colonists, and other

ancient peoples have inhabited the

Italian Peninsula. In antiquity, Italy was the

homeland of the

Romans and the

metropole

A metropole (from the Greek '' metropolis'' for "mother city") is the homeland, central territory or the state exercising power over a colonial empire.

From the 19th century, the English term ''metropole'' was mainly used in the scope of ...

of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

's provinces.

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

was founded as a

Kingdom in 753 BC and became a republic in 509 BC, when the

Roman monarchy was overthrown

The overthrow of the Roman monarchy was an event in ancient Rome that took place between the 6th and 5th centuries BC where a political revolution replaced the then-existing Roman monarchy under Lucius Tarquinius Superbus with a republic. ...

in favor of a government of the

Senate and the People

SPQR, an abbreviation for (; en, "The Roman Senate and People"; or more freely "The Senate and People of Rome"), is an emblematic abbreviated phrase referring to the government of the ancient Roman Republic. It appears on Roman currency, ...

. The

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

then

unified Italy at the expense of the

Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

,

Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

, and

Greek colonists of the peninsula. Rome led ''

Socii

The ''socii'' ( in English) or '' foederati'' ( in English) were confederates of Rome and formed one of the three legal denominations in Roman Italy (''Italia'') along with the Roman citizens (''Cives'') and the '' Latini''. The ''Latini'', who ...

'', a

confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical iss ...

of the

Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group identified by their use of Italic languages, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

The Italic peoples are descended from the Indo-European speaking peoples who inhabited Italy from at lea ...

, and later with the

rise of Rome dominated Western Europe, Northern Africa, and the Near East.

The Roman Republic saw its fall after the

assassination of Julius Caesar

Julius Caesar, the Roman dictator, was assassinated by a group of senators on the Ides of March (15 March) of 44 BC during a meeting of the Senate at the Curia of Pompey of the Theatre of Pompey in Rome where the senators stabbed Caesar 23 t ...

. The

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Roman Republic, Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings aro ...

later dominated Western Europe and the Mediterranean for many centuries, making immeasurable contributions to the development of Western philosophy, science and art. After the

fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its v ...

in AD 476, Italy was fragmented in numerous

city-states and regional polities; despite seeing famous personalities from its territory and closely related ones (such as

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

,

Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 14522 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested on ...

,

Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (; 6 March 1475 – 18 February 1564), known as Michelangelo (), was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was ins ...

,

Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli ( , , ; 3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527), occasionally rendered in English as Nicholas Machiavel ( , ; see below), was an Italian diplomat, author, philosopher and historian who lived during the Renaissance. ...

,

Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He ...

, and

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

) rise, it remained politically divided to a large extent. The

maritime republics, in particular

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

and

Genoa

Genoa ( ; it, Genova ; lij, Zêna ). is the capital of the Italian region of Liguria and the sixth-largest city in Italy. In 2015, 594,733 people lived within the city's administrative limits. As of the 2011 Italian census, the Province of ...

, rose to great prosperity through shipping, commerce, and banking, acting as Europe's main port of entry for Asian and Near Eastern imported goods and laying the groundwork for

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, private ...

.

Central Italy remained under the

Papal States

The Papal States ( ; it, Stato Pontificio, ), officially the State of the Church ( it, Stato della Chiesa, ; la, Status Ecclesiasticus;), were a series of territories in the Italian Peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope fro ...

, while

Southern Italy

Southern Italy ( it, Sud Italia or ) also known as ''Meridione'' or ''Mezzogiorno'' (), is a macroregion of the Italian Republic consisting of its southern half.

The term ''Mezzogiorno'' today refers to regions that are associated with the pe ...

remained largely

feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

due to a succession of

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

,

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

,

Norman,

Spanish, and

Bourbon crowns.

The

Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

spread to the rest of Europe, bringing a renewed interest in

humanism

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential and agency of human beings. It considers human beings the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "human ...

,

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

,

exploration

Exploration refers to the historical practice of discovering remote lands. It is studied by geographers and historians.

Two major eras of exploration occurred in human history: one of convergence, and one of divergence. The first, covering most ...

, and

art with the start of the

modern era

The term modern period or modern era (sometimes also called modern history or modern times) is the period of history that succeeds the Middle Ages (which ended approximately 1500 AD). This terminology is a historical periodization that is appli ...

.

Italian explorers (including

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in '' The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

,

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

( it, Cristoforo Colombo), and

Amerigo Vespucci) discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the

Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (or the Age of Exploration), also known as the early modern period, was a period largely overlapping with the Age of Sail, approximately from the 15th century to the 17th century in European history, during which seafa ...

,

although the Italian states had no occasions to found colonial empires outside of the

Mediterranean Basin

In biogeography, the Mediterranean Basin (; also known as the Mediterranean Region or sometimes Mediterranea) is the region of lands around the Mediterranean Sea that have mostly a Mediterranean climate, with mild to cool, rainy winters and wa ...

.

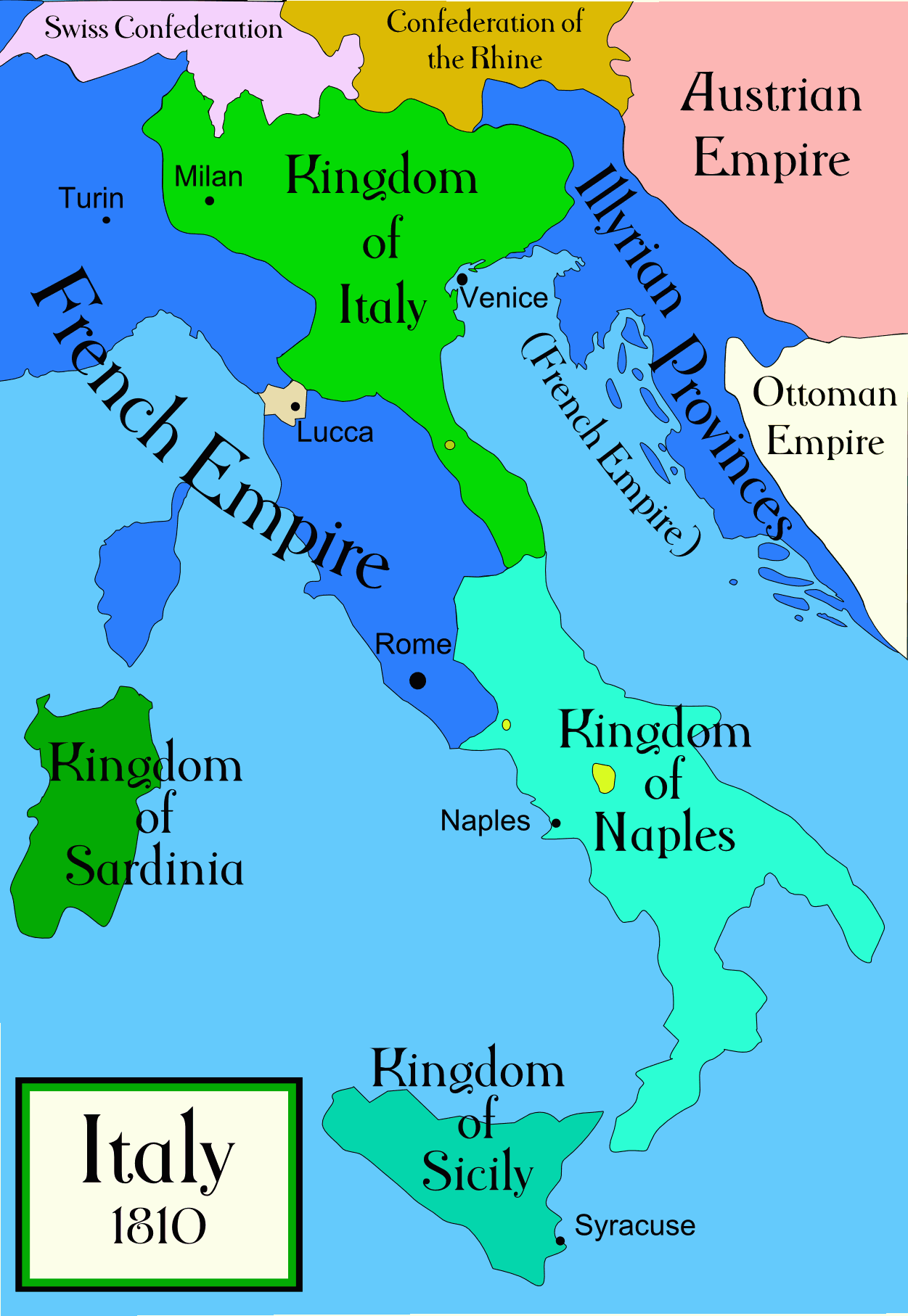

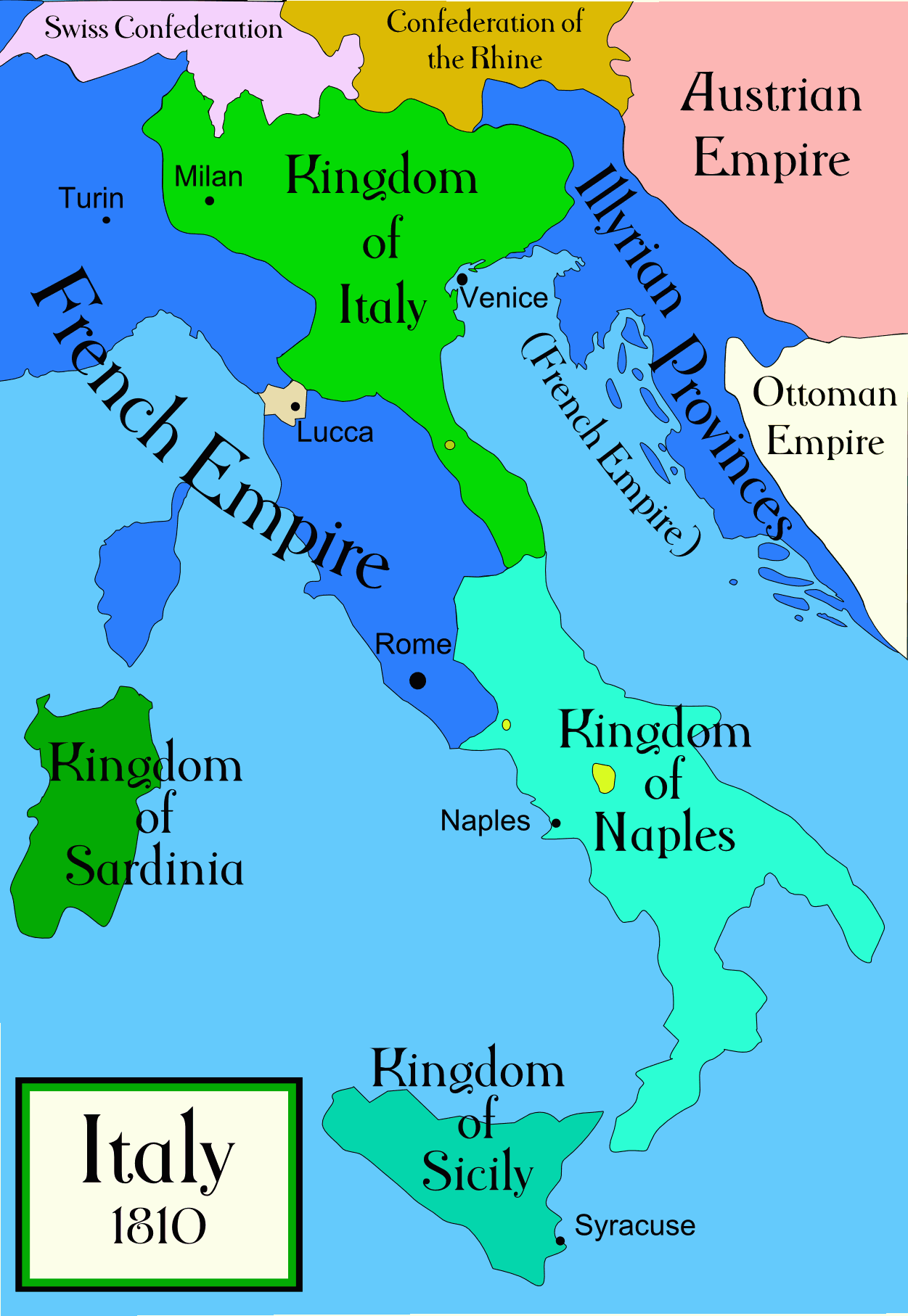

By the mid-19th century, the

Italian unification

The unification of Italy ( it, Unità d'Italia ), also known as the ''Risorgimento'' (, ; ), was the 19th-century political and social movement that resulted in the consolidation of different states of the Italian Peninsula into a single ...

by

Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi ( , ;In his native Ligurian language, he is known as ''Gioxeppe Gaibado''. In his particular Niçard dialect of Ligurian, he was known as ''Jousé'' or ''Josep''. 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general, pa ...

, backed by the

Kingdom of Sardinia, led to the establishment of an Italian nation-state. The new

Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy ( it, Regno d'Italia) was a state that existed from 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 1946, when civil discontent led to ...

, established in 1861, quickly modernized and built a

colonial empire

A colonial empire is a collective of territories (often called colonies), either contiguous with the imperial center or located overseas, settled by the population of a certain state and governed by that state.

Before the expansion of early mode ...

, controlling parts of Africa, and countries along the Mediterranean. At the same time, Southern Italy remained rural and poor, originating the

Italian diaspora

, image = Map of the Italian Diaspora in the World.svg

, image_caption = Map of the Italian diaspora in the world

, population = worldwide

, popplace = Brazil, Argentina, United States, France, Colombia, Canada, P ...

. In

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

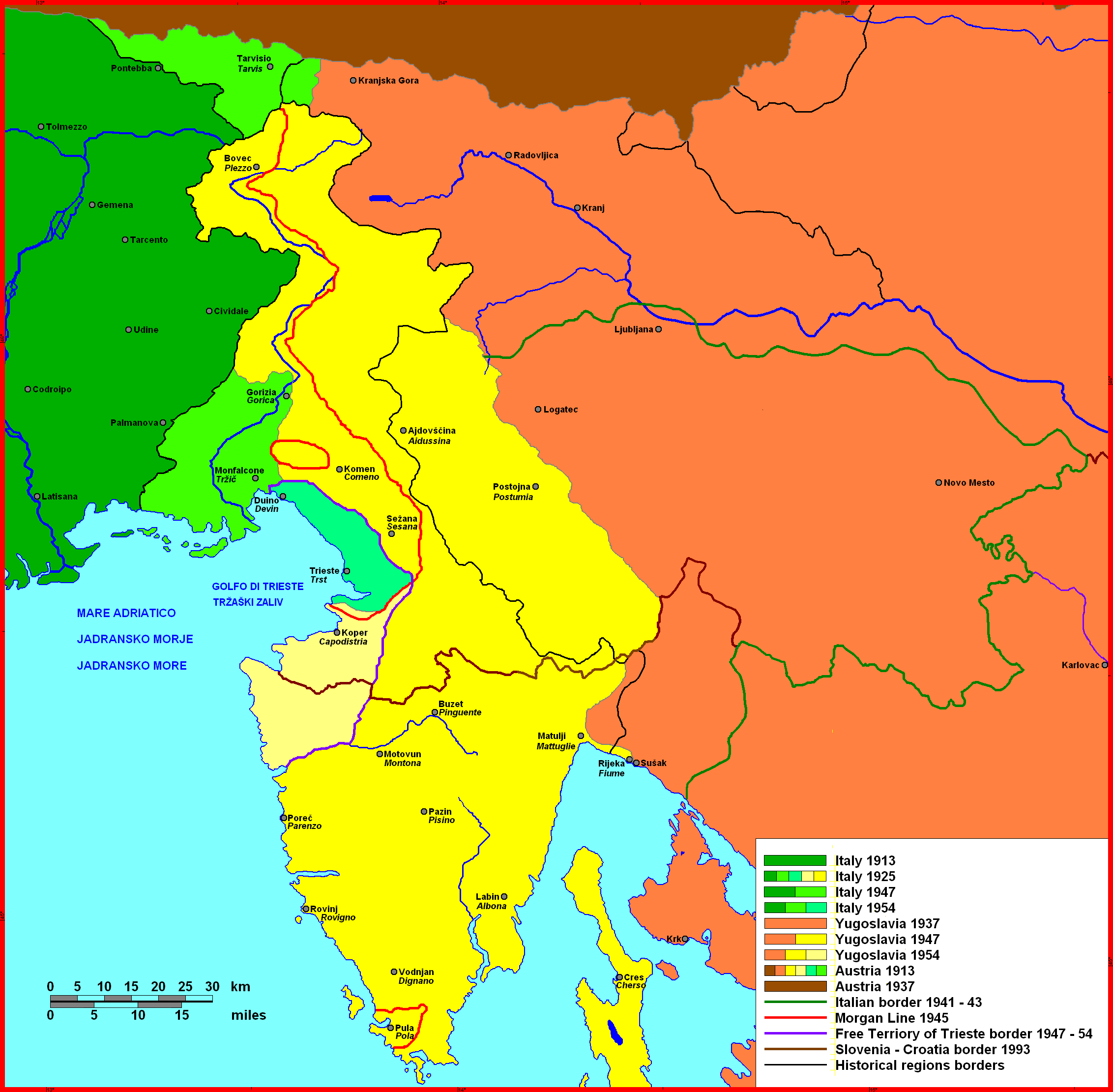

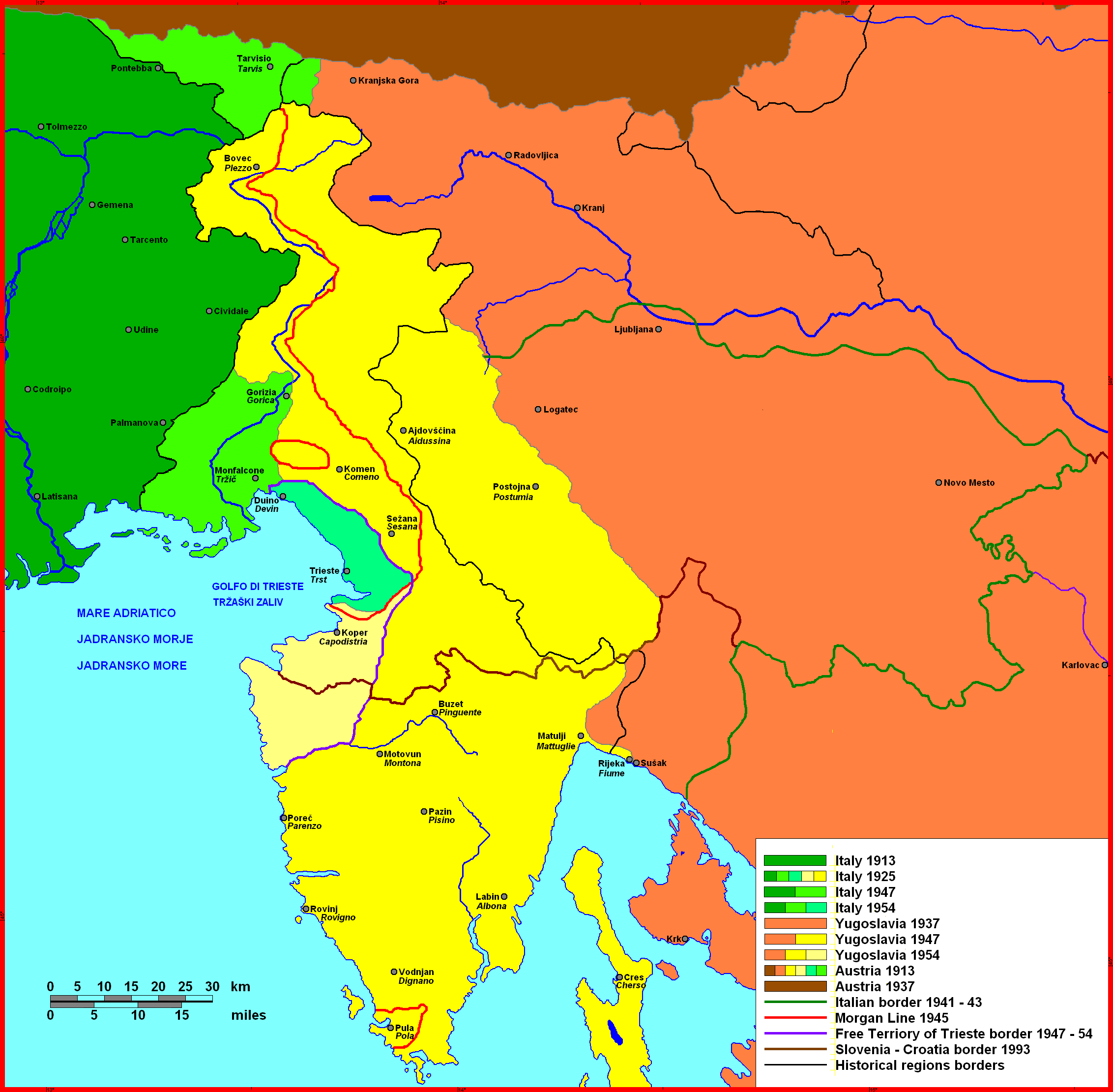

, Italy completed the unification by acquiring

Trento

Trento ( or ; Ladin and lmo, Trent; german: Trient ; cim, Tria; , ), also anglicized as Trent, is a city on the Adige River in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol in Italy. It is the capital of the autonomous province of Trento. In the 16th centu ...

and

Trieste

Trieste ( , ; sl, Trst ; german: Triest ) is a city and seaport in northeastern Italy. It is the capital city, and largest city, of the autonomous region of Friuli Venezia Giulia, one of two autonomous regions which are not subdivided into pr ...

, and gained a permanent seat in the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference th ...

's executive council.

Italian nationalists

Italian nationalism is a movement which believes that the Italians are a nation with a single homogeneous identity, and therefrom seeks to promote the cultural unity of Italy as a country. From an Italian nationalist perspective, Italianness is ...

considered World War I a ''

mutilated victory'' because Italy did not have all the territories promised by the

Treaty of London (1915) and that sentiment led to the rise of the

Fascist

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

dictatorship of

Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in ...

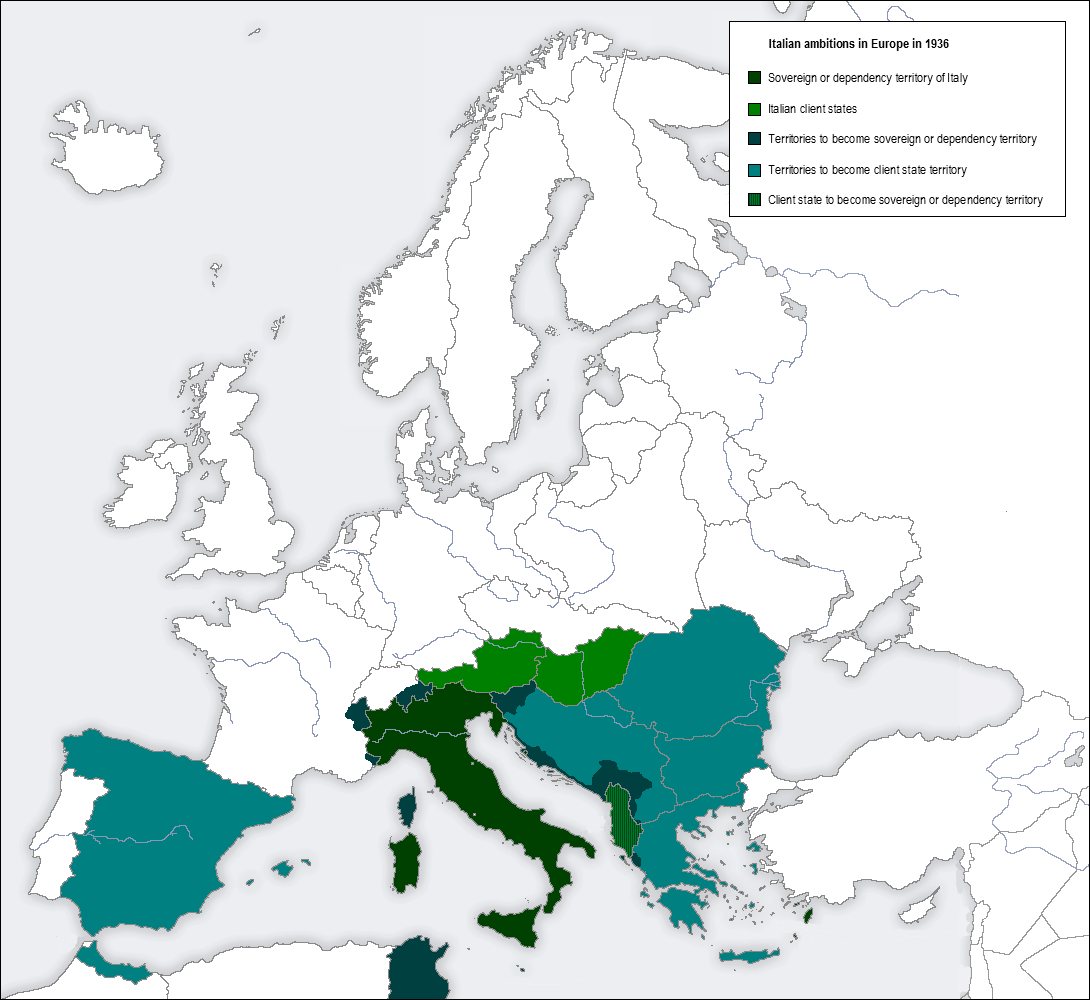

in 1922. The subsequent participation in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

with the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

, together with

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the

Empire of Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent form ...

, ended in military defeat, Mussolini's arrest and escape (aided by the German dictator

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and the ...

), and the

Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War ( Italian: ''Guerra civile italiana'', ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during World War II by Italian Fascists against the Italian partisans (mostly politically organized in the National Liberation Committ ...

between the

Italian Resistance (aided by the Kingdom, now a

co-belligerent

Co-belligerence is the waging of a war in cooperation against a common enemy with or without a formal treaty of military alliance. Generally, the term is used for cases where no alliance exists. Likewise, allies may not become co-belligerents in a ...

of the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

) and a

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

-fascist

puppet state known as the

Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic ( it, Repubblica Sociale Italiana, ; RSI), known as the National Republican State of Italy ( it, Stato Nazionale Repubblicano d'Italia, SNRI) prior to December 1943 but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò ...

.

Following the

liberation of Italy, the fall of the Social Republic, and the killing of Mussolini at the hands of the Resistance, the

1946 Italian constitutional referendum

An institutional referendum ( it, referendum istituzionale, or ) was held in Italy on 2 June 1946, Dieter Nohlen & Philip Stöver (2010) ''Elections in Europe: A data handbook'', p1047 a key event of Italian contemporary history.

Until 19 ...

abolished the monarchy and became a republic, reinstated democracy, enjoyed an

economic miracle

Economic miracle is an informal economic term for a period of dramatic economic development that is entirely unexpected or unexpectedly strong. Economic miracles have occurred in the recent histories of a number of countries, often those undergoing ...

, and founded the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational union, supranational political union, political and economic union of Member state of the European Union, member states that are located primarily in Europe, Europe. The union has a total area of ...

(

Treaty of Rome),

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two N ...

, and the

Group of Six

The Group of Seven (G7) is an intergovernmental political forum consisting of Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States; additionally, the European Union (EU) is a "non-enumerated member". It is offici ...

(later

G7 and

G20). It remains a strong economic, cultural, military, and political factor in the 21st century.

Prehistory

The arrival of the first

hominins was 850,000 years ago at

Monte Poggiolo

Monte Poggiolo is a hill near Forlì, Italy in the Emilia-Romagna area. The hill overlooks the Montone River valley from an elevation

of 212 m.

At Monte Poggiolo is a Florentine castle.

The fort was designed by Giuliano da Maiano

Giuliano da ...

.

[National Geographic Italia – Erano padani i primi abitanti d'Italia](_blank)

The presence of the ''

Homo neanderthalensis'' has been demonstrated in archaeological findings near Rome and

Verona

Verona ( , ; vec, Verona or ) is a city on the Adige River in Veneto, Italy, with 258,031 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region. It is the largest city municipality in the region and the second largest in nor ...

dating to c. 50,000 years ago (late

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( , often referred to as the ''Ice age'') is the geological Epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fina ...

).

Homo sapiens sapiens appeared during the upper

Palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic (), also called the Old Stone Age (from Greek: παλαιός '' palaios'', "old" and λίθος ''lithos'', "stone"), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone too ...

: the earliest sites in Italy dated 48,000 years ago is

Riparo Mochi

The Balzi Rossi caves (Ligurian: ''baussi rossi'' "red rocks") in Ventimiglia '' comune'', Liguria, Italy, is one of the most important archaeological sites of the early Upper Paleolithic in Western Europe.

*Riparo Mochi remains, evidence for t ...

(Italy). In November 2011 tests conducted at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit in England on what were previously thought to be Neanderthal baby teeth, which had been unearthed in 1964 dating from between 43,000 and 45,000 years ago.

Remains of the later prehistoric age have been found in Lombardy (stone carvings in

Valcamonica) and in

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

(

nuraghe

The nuraghe (, ; plural: Logudorese Sardinian , Campidanese Sardinian , Italian ), or also nurhag in English, is the main type of ancient megalithic edifice found in Sardinia, developed during the Nuragic Age between 1900 and 730 B. ...

). The most famous is perhaps that of

Ötzi the Iceman, the mummy of a mountain hunter found in the

Similaun glacier in South Tyrol, dating to c. 3400–3100 BC (

Copper Age

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', " stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin '' aeneus'' "of copper"), is an archaeological period characterized by regular ...

).

During the

Copper Age

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', " stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin '' aeneus'' "of copper"), is an archaeological period characterized by regular ...

, Indoeuropean people migrated to Italy. Approximately four waves of population from north to the Alps have been identified. A first Indoeuropean migration occurred around the mid-3rd millennium BC, from a population who imported

coppersmithing

A coppersmith, also known as a brazier, is a person who makes artifacts from copper and brass. Brass is an alloy of copper and zinc. The term "redsmith" is used for a tinsmith that uses tinsmithing tools and techniques to make copper items.

Hi ...

. The

Remedello culture

The Remedello culture (Italian ''Cultura di Remedello'') developed during the Copper Age (4th and 3rd millennium BC) in Northern Italy, particularly in the area of the Po valley. The name comes from the town of Remedello (Brescia) where several ...

took over the

Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic ex ...

. The second wave of immigration occurred in the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, from the late 3rd to the early 2nd millennium BC, with tribes identified with the

Beaker culture and by the use of

bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals, such as phosphorus, or metalloids suc ...

smithing, in the

Padan Plain, in

Tuscany

it, Toscano (man) it, Toscana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Citizenship

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 = Italian

, demogra ...

and on the coasts of

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

and

Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

.

In the mid-2nd millennium BC, a third wave arrived, associated with the

Apenninian civilization and the

Terramare culture

Terramare, terramara, or terremare is a technology complex mainly of the central Po valley, in Emilia, Northern Italy, dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Age c. 1700–1150 BC. It takes its name from the "black earth" residue of settleme ...

which takes its name from the black earth (terremare) residue of settlement mounds, which have long served the fertilizing needs of local farmers.

The occupations of the Terramare people as compared with their Neolithic predecessors may be inferred with comparative certainty. They were still hunters, but had domesticated animals; they were fairly skilful metallurgists, casting bronze in moulds of stone and clay, and they were also agriculturists, cultivating beans, the vine, wheat and flax.

In the late Bronze Age, from the late 2nd millennium to the early 1st millennium BC, a fourth wave, the

Proto-Villanovan culture, related to the Central European

Urnfield culture, brought iron-working to the Italian peninsula. Proto-Villanovan culture was part of the central European

Urnfield culture system. Similarity has also been noted with the regional groups of

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total l ...

-

Upper Austria

Upper Austria (german: Oberösterreich ; bar, Obaöstareich) is one of the nine states or of Austria. Its capital is Linz. Upper Austria borders Germany and the Czech Republic, as well as the other Austrian states of Lower Austria, Styria, an ...

[M. Gimbutas ''Bronze Age Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe'' pp. 339–345] and of the middle-

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , pa ...

.

Another hypothesis, however, is that it was a derivation from the previous

Terramare culture

Terramare, terramara, or terremare is a technology complex mainly of the central Po valley, in Emilia, Northern Italy, dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Age c. 1700–1150 BC. It takes its name from the "black earth" residue of settleme ...

of the

Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain ( it, Pianura Padana , or ''Val Padana'') is a major geographical feature of Northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetic ex ...

. Various authors, such as

Marija Gimbutas

Marija Gimbutas ( lt, Marija Gimbutienė, ; January 23, 1921 – February 2, 1994) was a Lithuanian archaeologist and anthropologist known for her research into the Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures of " Old Europe" and for her Kurgan hypothesis ...

, associated this culture with the arrival, or the spread, of the proto-

Italics

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Owing to the influence from calligraphy, italics normally slant slightly to the right. Italics are a way to emphasise key points in a printed t ...

into the

Italian peninsula.

In Sicily, small dolmens dating back to the end of the third millennium BC have recently been found, similar to those found in Spain, Balearic Islands, Sardinia and Apulia. The discoverer of this Culture (whom he named in Sicily "Dolmens Culture") associates it with the arrival on the west coast of Sicily of a cultural wave bringing, the bell-shaped goblet, coming from the Sardinian coast.

Nuragic civilization

Born in

Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; it, Sardegna, label=Italian, Corsican and Tabarchino ; sc, Sardigna , sdc, Sardhigna; french: Sardaigne; sdn, Saldigna; ca, Sardenya, label= Algherese and Catalan) is the second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, aft ...

and

southern Corsica

Corse-du-Sud (; co, link=no, Corsica suttana , or ; en, Southern Corsica) is (as of 2019) an administrative department of France, consisting of the southern part of the island of Corsica. The corresponding departmental territorial collect ...

, the

Nuraghe

The nuraghe (, ; plural: Logudorese Sardinian , Campidanese Sardinian , Italian ), or also nurhag in English, is the main type of ancient megalithic edifice found in Sardinia, developed during the Nuragic Age between 1900 and 730 B. ...

civilization lasted from the early

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

(18th century BC) to the 2nd century AD, when the islands were already

Romanized

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, and ...

.

They take their name from the characteristic Nuragic towers, which evolved from the pre-existing megalithic culture, which built

dolmen

A dolmen () or portal tomb is a type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the early Neolithic (40003000 BCE) and were some ...

s and

menhirs. Today more than 7,000 nuraghes dot the Sardinian landscape.

No written records of this civilization have been discovered, apart from a few possible short epigraphic documents belonging to the last stages of the Nuragic civilization.

The only written information there comes from classical literature of the

Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

and

Romans, and may be considered more mythological than historical.

The language (or languages) spoken in Sardinia during the Bronze Age is (are) unknown since there are no written records from the period, although recent research suggests that around the 8th century BC, in the

Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

, the Nuragic populations may have adopted an alphabet similar to that used in

Euboea

Evia (, ; el, Εύβοια ; grc, Εὔβοια ) or Euboia (, ) is the second-largest Greek island in area and population, after Crete. It is separated from Boeotia in mainland Greece by the narrow Euripus Strait (only at its narrowest poi ...

.

According to

Eduardo Blasco Ferrer

Eduardo Blasco Ferrer ( Barcelona, 1956 – Bastia, 12 January 2017) was a Spanish-Italian linguist and a professor at the University of Cagliari, Sardinia. He is best known as the author of several studies about the Paleo-Sardinian and Sardini ...

, the

Paleo-Sardinian language was akin to

Proto-Basque

Proto-Basque ( eu, aitzineuskara; es, protoeuskera, protovasco; french: proto-basque), or Pre-Basque, is the reconstructed predecessor of the Basque language before the Roman conquests in the Western Pyrenees.

Background

The first linguist w ...

and

ancient Iberian with faint

Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

traces, but others believe it was related to

Etruscan. Some scholars theorize that there were actually various linguistic areas (two or more) in Nuragic Sardinia, possibly

Pre-Indo-Europeans Pre-Indo-European means "preceding Indo-European languages".

Pre-Indo-European may refer to:

* Pre-Indo-European languages, several (not necessarily related) ancient languages in prehistoric Europe and South Asia before the arrival of Indo-European ...

and

Indo-Europeans.

[

]

Iron Age

Italy gradually enters the proto-historical period in the 8th century BC, with the introduction of the Phoenician script

The Phoenician alphabet is an alphabet (more specifically, an abjad) known in modern times from the Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions found across the Mediterranean region. The name comes from the Phoenician civilization.

The Phoenician alpha ...

and its adaptation in various regional variants.

Etruscan civilization

The

The Etruscan civilization

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

flourished in central Italy after 800 BC. The origins of the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

are lost in prehistory. The main hypotheses are that they are indigenous, probably stemming from the Villanovan culture

The Villanovan culture (c. 900–700 BC), regarded as the earliest phase of the Etruscan civilization, was the earliest Iron Age culture of Italy. It directly followed the Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture which branched off from the Urnfiel ...

. A mitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA or mDNA) is the DNA located in mitochondria, cellular organelles within eukaryotic cells that convert chemical energy from food into a form that cells can use, such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial D ...

study of 2013 has suggested that the Etruscans were probably an indigenous population.Indo-European language

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

. Some inscriptions in a similar language have been found on the Aegean island of Lemnos. Etruscans were a monogamous society that emphasized pairing. The historical Etruscans had achieved a form of state with remnants of chiefdom and tribal forms. The Etruscan religion was an immanent polytheism, in which all visible phenomena were considered to be a manifestation of divine power, and deities continually acted in the world of men and could, by human action or inaction, be dissuaded against or persuaded in favor of human affairs.

Etruscan expansion was focused across the

Etruscan expansion was focused across the Apennines

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains (; grc-gre, links=no, Ἀπέννινα ὄρη or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; la, Appenninus or – a singular with plural meaning;''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which wou ...

. Some small towns in the 6th century BC have disappeared during this time, ostensibly consumed by greater, more powerful neighbors. However, there exists no doubt that the political structure of the Etruscan culture was similar, albeit more aristocratic, to Magna Graecia in the south. The mining and commerce of metal, especially copper and iron, led to an enrichment of the Etruscans and to the expansion of their influence in the Italian peninsula and the western Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

sea. Here their interests collided with those of the Greeks, especially in the 6th century BC, when Phoceans

Phocaea or Phokaia ( Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Greek colonists from Phocaea founded the colony of Massalia (modern-day Marseille, in ...

of Italy founded colonies along the coast of France, Catalonia and Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

. This led the Etruscans to ally themselves with the Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

, whose interests also collided with the Greeks.Battle of Alalia

The naval Battle of Alalia took place between 540 BC and 535 BC off the coast of Corsica between Greeks and the allied Etruscans and Carthaginians. A Greek force of 60 Phocaean ships defeated a Punic-Etruscan fleet of 120 ships while emigrating ...

led to a new distribution of power in the western Mediterranean Sea. Although the battle had no clear winner, Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

managed to expand its sphere of influence at the expense of the Greeks, and Etruria saw itself relegated to the northern Tyrrhenian Sea

The Tyrrhenian Sea (; it, Mar Tirreno , french: Mer Tyrrhénienne , sc, Mare Tirrenu, co, Mari Tirrenu, scn, Mari Tirrenu, nap, Mare Tirreno) is part of the Mediterranean Sea off the western coast of Italy. It is named for the Tyrrhenian pe ...

with full ownership of Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

. From the first half of the 5th century, the new international political situation meant the beginning of the Etruscan decline after losing their southern provinces. In 480 BC, Etruria's ally Carthage was defeated by a coalition of Magna Graecia cities led by Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

.Latium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil ( Old Latium) on w ...

and Campania weakened, and it was taken over by Romans and Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they f ...

. In the 4th century, Etruria saw a Gallic invasion end its influence over the Po valley and the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Sea) to the ...

coast. Meanwhile, Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

had started annexing Etruscan cities. This led to the loss of their north provinces. Etruscia

Etruria () was a region of Central Italy, located in an area that covered part of what are now most of Tuscany, northern Lazio, and northern and western Umbria.

Etruscan Etruria

The ancient people of Etruria

are identified as Etruscans. Their ...

was assimilated by Rome around 500 BC.

Italic peoples

The Italic peoples were an

The Italic peoples were an ethnolinguistic group

An ethnolinguistic group (or ethno-linguistic group) is a group that is unified by both a common ethnicity and language. Most ethnic groups share a first language. However, "ethnolinguistic" is often used to emphasise that language is a major ...

identified by their use of Italic languages

The Italic languages form a branch of the Indo-European language family, whose earliest known members were spoken on the Italian Peninsula in the first millennium BC. The most important of the ancient languages was Latin, the official languag ...

, a branch of the Indo-European

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, Du ...

language family. Among the Italic peoples in the Italian peninsula were the Osci

The Osci (also called Oscans, Opici, Opsci, Obsci, Opicans) were an Italic people of Campania and Latium adiectum before and during Roman times. They spoke the Oscan language, also spoken by the Samnites of Southern Italy. Although the languag ...

, the Veneti, the Samnites

The Samnites () were an ancient Italic people who lived in Samnium, which is located in modern inland Abruzzo, Molise, and Campania in south-central Italy.

An Oscan-speaking people, who may have originated as an offshoot of the Sabines, they f ...

, the Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

and the Umbri

The Umbri were an Italic people of ancient Italy. A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the ancient Umbria.

Most ancient Umbrian cities were settled in the 9th-4th centuries BC on ...

.

In the region south of the Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

(''Latium Vetus''), the Latial culture of the Latins

The Latins were originally an Italic tribe in ancient central Italy from Latium. As Roman power and colonization spread Latin culture during the Roman Republic.

Latins culturally "Romanized" or "Latinized" the rest of Italy, and the word Latin ...

emerged, while in the north-east of the peninsula the Este culture of the Veneti appeared. Roughly in the same period, from their core area in central Italy (modern-day Umbria

it, Umbro (man) it, Umbra (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, ...

and Sabina region), the Osco-Umbri

The Umbri were an Italic people of ancient Italy. A region called Umbria still exists and is now occupied by Italian speakers. It is somewhat smaller than the ancient Umbria.

Most ancient Umbrian cities were settled in the 9th-4th centuries BC on ...

ans began to emigrate in various waves, through the process of Ver sacrum, the ritualized extension of colonies, in southern Latium, Molise

it, Molisano (man) it, Molisana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 ...

and the whole southern half of the peninsula, replacing the previous tribes, such as the Opici The Opici were an ancient italic people of the Latino-Faliscan group who lived in the region of Campania. They settled in the area in the late Bronze Age but their territory was later conquered during the Iron Age by the Osci, another Italic people ...

and the Oenotrians

The Oenotrians (Οἴνωτρες, meaning "tribe led by Oenotrus" or "people from the land of vines - Οἰνωτρία") were an ancient Italic people who inhabited a territory in Southern Italy from Paestum to southern Calabria. By the sixth ...

. This corresponds with the emergence of the Terni culture, which had strong similarities with the Celtic cultures of Hallstatt and La Tène. The Umbrian necropolis of Terni

Terni ( , ; lat, Interamna (Nahars)) is a city in the southern portion of the region of Umbria in central Italy. It is near the border with Lazio. The city is the capital of the province of Terni, located in the plain of the Nera river. It i ...

, which dates back to the 10th century BCE, was identical in every aspect to the Celtic necropolis of the Golasecca culture.

Before and during the period of the arrival of the Greek and Phoenician immigrants, the island of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

was already inhabited by native Italics, which are divided into 3 major groups, the Elymians in the west, the Sicani in the centre, and the Sicels

The Sicels (; la, Siculi; grc, Σικελοί ''Sikeloi'') were an Italic tribe who inhabited eastern Sicily during the Iron Age. Their neighbours to the west were the Sicani. The Sicels gave Sicily the name it has held since antiquity, b ...

in the east. The Sicels gave Sicily the name it has held since antiquity.

Among the populations who inhabited northern Italy in the Iron Age, one of the most prominent were the Ligures. It is generally believed that around 2000 BC, they occupied a large area of the Italian peninsula, including much of north-western Italy and all of northern Tuscany (the part that lies north of the Arno river

The Arno is a river in the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the most important river of central Italy after the Tiber.

Source and route

The river originates on Monte Falterona in the Casentino area of the Apennines, and initially takes a so ...

). Since many scholars consider the language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

of this ancient population to be Pre-Indo-European, they are often not classified as Italics

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Owing to the influence from calligraphy, italics normally slant slightly to the right. Italics are a way to emphasise key points in a printed t ...

.Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

were growing in power and influence. After the Latins had liberated themselves from Etruscan rule they acquired a dominant position among the Italic tribes. Frequent conflict between various Italic tribes followed. The best documented of these are the wars between the Latins and the Samnites.Marsi

The Marsi were an Italic people of ancient Italy, whose chief centre was Marruvium, on the eastern shore of Lake Fucinus (which was drained for agricultural land in the late 19th century). The area in which they lived is now called Marsica. D ...

and the Samnites, rebelled against Roman rule. This conflict is called the Social War. After Roman victory was secured, all peoples in Italy, except for the Celts

The Celts (, see pronunciation for different usages) or Celtic peoples () are. "CELTS location: Greater Europe time period: Second millennium B.C.E. to present ancestry: Celtic a collection of Indo-European peoples. "The Celts, an ancient ...

of the Po Valley, were granted Roman citizenship. In the subsequent centuries, Italic tribes adopted Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

language and culture in a process known as Romanization

Romanization or romanisation, in linguistics, is the conversion of text from a different writing system to the Roman (Latin) script, or a system for doing so. Methods of romanization include transliteration, for representing written text, a ...

.

Magna Graecia

In the eighth and seventh centuries BC, for various reasons, including demographic crisis (famine, overcrowding, etc.), the search for new commercial outlets and ports, and expulsion from their homeland, Greeks began to settle in Southern Italy (Cerchiai, pp. 14–18). Also during this period, Greek colonies were established in places as widely separated as the eastern coast of the

In the eighth and seventh centuries BC, for various reasons, including demographic crisis (famine, overcrowding, etc.), the search for new commercial outlets and ports, and expulsion from their homeland, Greeks began to settle in Southern Italy (Cerchiai, pp. 14–18). Also during this period, Greek colonies were established in places as widely separated as the eastern coast of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

, Eastern Libya and Massalia (Marseille

Marseille ( , , ; also spelled in English as Marseilles; oc, Marselha ) is the prefecture of the French department of Bouches-du-Rhône and capital of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region. Situated in the camargue region of southern Fra ...

) in Gaul. They included settlements in Sicily and the southern part of the Italian peninsula.

The Romans called the area of Sicily and the foot of Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical ...

Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia (, ; , , grc, Μεγάλη Ἑλλάς, ', it, Magna Grecia) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of Southern Italy in the present-day Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania and Sicily; the ...

(Latin, "Great Greece"), since it was densely inhabited by the Greeks

The Greeks or Hellenes (; el, Έλληνες, ''Éllines'' ) are an ethnic group and nation indigenous to the Eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea regions, namely Greece, Cyprus, Albania, Italy, Turkey, Egypt, and, to a lesser extent, ot ...

. The ancient geographers differed on whether the term included Sicily or merely Apulia

it, Pugliese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographic ...

, Campania

(man), it, Campana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demog ...

and Calabria

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

—Strabo

Strabo''Strabo'' (meaning "squinty", as in strabismus) was a term employed by the Romans for anyone whose eyes were distorted or deformed. The father of Pompey was called " Pompeius Strabo". A native of Sicily so clear-sighted that he could s ...

being the most prominent advocate of the wider definitions.

With this colonization, Greek culture

The culture of Greece has evolved over thousands of years, beginning in Minoan and later in Mycenaean Greece, continuing most notably into Classical Greece, while influencing the Roman Empire and its successor the Byzantine Empire. Other cul ...

was exported to Italy, in its dialects of the Ancient Greek language, its religious rites and its traditions of the independent ''polis

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

''. An original Hellenic civilization soon developed, later interacting with the native Italic and Latin civilisations. The most important cultural transplant was the Chalcidean/ Cumaean variety of the Greek alphabet

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BCE. It is derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and was the earliest known alphabetic script to have distinct letters for vowels as ...

, which was adopted by the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

; the Old Italic alphabet

The Old Italic scripts are a family of similar ancient writing systems used in the Italian Peninsula between about 700 and 100 BC, for various languages spoken in that time and place. The most notable member is the Etruscan alphabet, which ...

subsequently evolved into the Latin alphabet

The Latin alphabet or Roman alphabet is the collection of letters originally used by the ancient Romans to write the Latin language. Largely unaltered with the exception of extensions (such as diacritics), it used to write English and the ...

, which became the most widely used alphabet in the world. Many of the new Hellenic cities became very rich and powerful, like ''Neapolis'' (Νεάπολις,

Many of the new Hellenic cities became very rich and powerful, like ''Neapolis'' (Νεάπολις, Naples

Naples (; it, Napoli ; nap, Napule ), from grc, Νεάπολις, Neápolis, lit=new city. is the regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 909,048 within the city's adm ...

, "New City"), ''Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

* Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

* Province of Syracuse

United States

*Syracuse, New York

**East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

'', '' Acragas'', and '' Sybaris'' (Σύβαρις). Other cities in Magna Graecia included ''Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

'' (Τάρας), '' Epizephyrian Locri'' (Λοκροί Ἐπιζεφύριοι), ''Rhegium

Reggio di Calabria ( scn, label= Southern Calabrian, Riggiu; el, label=Calabrian Greek, Ρήγι, Rìji), usually referred to as Reggio Calabria, or simply Reggio by its inhabitants, is the largest city in Calabria. It has an estimated popul ...

'' (Ῥήγιον), '' Croton'' (Κρότων), ''Thurii

Thurii (; grc-gre, Θούριοι, Thoúrioi), called also by some Latin writers Thurium (compare grc-gre, Θούριον in Ptolemy), for a time also Copia and Copiae, was a city of Magna Graecia, situated on the Tarentine gulf, within a s ...

'' (Θούριοι), '' Elea'' (Ἐλέα), ''Nola

Nola is a town and a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Naples, Campania, southern Italy. It lies on the plain between Mount Vesuvius and the Apennines. It is traditionally credited as the diocese that introduced bells to Christian wo ...

'' (Νῶλα), ''Ancona

Ancona (, also , ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region in central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona and of the region. The city is located northeast of Rome, on the Adriatic ...

'' (Ἀγκών), '' Syessa'' (Σύεσσα), ''Bari

Bari ( , ; nap, label= Barese, Bare ; lat, Barium) is the capital city of the Metropolitan City of Bari and of the Apulia region, on the Adriatic Sea, southern Italy. It is the second most important economic centre of mainland Southern Ital ...

'' (Βάριον), and others.

After Pyrrhus of Epirus failed in his attempt to stop the spread of Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

* Rome, the capital city of Italy

* Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lett ...

hegemony in 282 BC, the south fell under Roman domination and remained in such a position well into the barbarian invasions

The Migration Period was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman ...

(the Gladiator War

The Third Servile War, also called the Gladiator War and the War of Spartacus by Plutarch, was the last in a series of slave rebellions against the Roman Republic known as the Servile Wars. This third rebellion was the only one that directly ...

is a notable suspension of imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas

...

control). It was held by the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

after the fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its v ...

in the West and even the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the ''History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

failed to consolidate it, though the centre of the south was theirs from Zotto's conquest in the final quarter of the 6th century.

Roman period

Roman Kingdom

Little is certain about the history of the Roman Kingdom, as nearly no written records from that time survive, and the histories about it that were written during the

Little is certain about the history of the Roman Kingdom, as nearly no written records from that time survive, and the histories about it that were written during the Republic

A republic () is a " state in which power rests with the people or their representatives; specifically a state without a monarchy" and also a "government, or system of government, of such a state." Previously, especially in the 17th and 18th ...

and Empire

An empire is a "political unit" made up of several territories and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) ex ...

are largely based on legends. However, the history of the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding, traditionally dated to 753 BC with settlements around the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; la, Collis Palatium or Mons Palatinus; it, Palatino ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city and has been called "the first nucleus of the Roman Empire." ...

along the river Tiber

The Tiber ( ; it, Tevere ; la, Tiberis) is the third-longest river in Italy and the longest in Central Italy, rising in the Apennine Mountains in Emilia-Romagna and flowing through Tuscany, Umbria, and Lazio, where it is joined by th ...

in Central Italy, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic in about 509 BC.

The site of Rome had a ford where the Tiber could be crossed. The Palatine Hill and hills surrounding it presented easily defensible positions in the wide fertile plain surrounding them. All of these features contributed to the success of the city.

The traditional account of Roman history, which has come down to us through Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for hi ...

, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and others, is that in Rome's first centuries it was ruled by a succession of seven kings. The traditional chronology, as codified by Varro

Marcus Terentius Varro (; 116–27 BC) was a Roman polymath and a prolific author. He is regarded as ancient Rome's greatest scholar, and was described by Petrarch as "the third great light of Rome" (after Vergil and Cicero). He is sometimes calle ...

, allots 243 years for their reigns, an average of almost 35 years, which, since the work of Barthold Georg Niebuhr, has been generally discounted by modern scholarship.

The Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

destroyed much of Rome's historical records when they sacked the city after the Battle of the Allia in 390 BC (Varronian, according to Polybius

Polybius (; grc-gre, Πολύβιος, ; ) was a Greek historian of the Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , which covered the period of 264–146 BC and the Punic Wars in detail.

Polybius is important for his analysis of the mixed ...

the battle occurred in 387/6) and what was left was eventually lost to time or theft. With no contemporary records of the kingdom existing, all accounts of the kings must be carefully questioned.

According to the founding myth of Rome, the city was founded

Founding may refer to:

* The formation of a corporation, government, or other organization

* The laying of a building's Foundation

* The casting of materials in a mold

See also

* Foundation (disambiguation)

* Incorporation (disambiguation)

In ...

on 21 April 753 BC by twin brothers Romulus and Remus

In Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus (, ) are twin brothers whose story tells of the events that led to the founding of the city of Rome and the Roman Kingdom by Romulus, following his fratricide of Remus. The image of a she-wolf sucklin ...

, who descended from the Trojan prince Aeneas

In Greco-Roman mythology, Aeneas (, ; from ) was a Trojan hero, the son of the Trojan prince Anchises and the Greek goddess Aphrodite (equivalent to the Roman Venus). His father was a first cousin of King Priam of Troy (both being grandsons ...

and who were grandsons of the Latin King, Numitor of Alba Longa

Alba Longa (occasionally written Albalonga in Italian sources) was an ancient Latin city in Central Italy, 12 miles (19 km) southeast of Rome, in the vicinity of Lake Albano in the Alban Hills. Founder and head of the Latin League, it wa ...

.

Roman Republic

According to tradition and later writers such as

According to tradition and later writers such as Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding in ...

, the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Ki ...

was established around 509 BC, when the last of the seven kings of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, was deposed by Lucius Junius Brutus

Lucius Junius Brutus ( 6th century BC) was the semi-legendary founder of the Roman Republic, and traditionally one of its first consuls in 509 BC. He was reputedly responsible for the expulsion of his uncle the Roman king Tarquinius Superbus after ...

, and a system based on annually elected magistrates

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judic ...

and various representative assemblies was established. A constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

set a series of checks and balances, and a separation of powers

Separation of powers refers to the division of a state's government into branches, each with separate, independent powers and responsibilities, so that the powers of one branch are not in conflict with those of the other branches. The typi ...

. The most important magistrates were the two consuls, who together exercised executive authority as '' imperium'', or military command. The consuls had to work with the senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, which was initially an advisory council of the ranking nobility, or patricians, but grew in size and power.

In the 4th century BC the Republic came under attack by the Gauls

The Gauls ( la, Galli; grc, Γαλάται, ''Galátai'') were a group of Celtic peoples of mainland Europe in the Iron Age and the Roman period (roughly 5th century BC to 5th century AD). Their homeland was known as Gaul (''Gallia''). They sp ...

, who initially prevailed and sacked Rome. The Romans then took up arms and drove the Gauls back, led by Camillus. The Romans gradually subdued the other peoples on the Italian peninsula, including the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization () was developed by a people of Etruria in ancient Italy with a common language and culture who formed a federation of city-states. After conquering adjacent lands, its territory covered, at its greatest extent, roug ...

. The last threat to Roman hegemony in Italy came when Tarentum Tarentum may refer to:

* Taranto, Apulia, Italy, on the site of the ancient Roman city of Tarentum (formerly the Greek colony of Taras)

**See also History of Taranto

* Tarentum (Campus Martius), also Terentum, an area in or on the edge of the Camp ...

, a major Greek colony, enlisted the aid of Pyrrhus of Epirus in 281 BC, but this effort failed as well.

In the 3rd century BC Rome had to face a new and formidable opponent: the powerful Phoenician city-state of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classi ...

. In the three Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146BC fought between Rome and Carthage. Three conflicts between these states took place on both land and sea across the western Mediterranean region and involved a total of forty-three ye ...

, Carthage was eventually destroyed and Rome gained control over Hispania, Sicily and North Africa. After defeating the Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled ...

ian and Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

s in the 2nd century BC, the Romans became the dominant people of the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on ...

.[Bagnall 1990] The conquest of the Hellenistic kingdoms provoked a fusion between Roman and Greek cultures and the Roman elite, once rural, became a luxurious and cosmopolitan one. By this time Rome was a consolidated empire – in the military view – and had no major enemies.

The one open sore was Spain (Hispania). Roman armies occupied Spain in the early 2nd century BC but encountered stiff resistance from that time down to the age of Augustus. The Celtiberian stronghold of Numantia became the centre of Spanish resistance to Rome in the 140s and 130s BC. Numantia fell and was completely razed to the ground in 133 BC. In 105 BC, the Celtiberians still retained enough of their native vigour and ferocity to drive the

The one open sore was Spain (Hispania). Roman armies occupied Spain in the early 2nd century BC but encountered stiff resistance from that time down to the age of Augustus. The Celtiberian stronghold of Numantia became the centre of Spanish resistance to Rome in the 140s and 130s BC. Numantia fell and was completely razed to the ground in 133 BC. In 105 BC, the Celtiberians still retained enough of their native vigour and ferocity to drive the Cimbri

The Cimbri (Greek Κίμβροι, ''Kímbroi''; Latin ''Cimbri'') were an ancient tribe in Europe. Ancient authors described them variously as a Celtic people (or Gaulish), Germanic people, or even Cimmerian. Several ancient sources indicate ...

and Teutones

The Teutons ( la, Teutones, , grc, Τεύτονες) were an ancient northern European tribe mentioned by Roman authors. The Teutons are best known for their participation, together with the Cimbri and other groups, in the Cimbrian War with t ...

from northern Spain, though these had crushed Roman arms in southern Gaul, inflicting 80,000 casualties on the Roman army which opposed them. The conquest of Hispania was completed in 19 BC—but at a heavy cost and severe losses.

Towards the end of the 2nd century BC, a huge migration of Germanic tribes took place, led by the Cimbri and the Teutones. These tribes overwhelmed the peoples with whom they came into contact and posed a real threat to Italy itself. At the