The presence of German-speaking populations in

Central and Eastern Europe

Central and Eastern Europe is a term encompassing the countries in the Baltics, Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Southeast Europe (mostly the Balkans), usually meaning former communist states from the Eastern Bloc and Warsaw Pact in Europ ...

is rooted in centuries of history, with the settling in northeastern Europe of

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

predating even the founding of the Roman Empire. The presence of independent

German states in the region (particularly

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

), and later the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

as well as other multi-ethnic countries with German-speaking minorities, such as

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

,

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

,

Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. The ...

, etc., demonstrates the extent and duration of German-speaking settlements.

The number of ethnic Germans in

Central

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known a ...

and

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

dropped dramatically as the result of the post-1944

German flight and expulsion from Central and Eastern Europe. There are still substantial numbers of ethnic Germans in the countries that are now Germany and Austria's neighbors to the east—

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

,

Czechia

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The Cz ...

,

Slovakia

Slovakia (; sk, Slovensko ), officially the Slovak Republic ( sk, Slovenská republika, links=no ), is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the ...

, and

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

.

Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bot ...

, the

Baltics

The Baltic states, et, Balti riigid or the Baltic countries is a geopolitical term, which currently is used to group three countries: Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. All three countries are members of NATO, the European Union, the Eurozone, ...

(

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

,

Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

,

Lithuania

Lithuania (; lt, Lietuva ), officially the Republic of Lithuania ( lt, Lietuvos Respublika, links=no ), is a country in the Baltic region of Europe. It is one of three Baltic states and lies on the eastern shore of the Baltic Sea. Lithuania ...

), the

Balkans

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

(

Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

,

Croatia

, image_flag = Flag of Croatia.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Croatia.svg

, anthem = " Lijepa naša domovino"("Our Beautiful Homeland")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capi ...

,

Bosnia

Bosnia and Herzegovina ( sh, / , ), abbreviated BiH () or B&H, sometimes called Bosnia–Herzegovina and Pars pro toto#Geography, often known informally as Bosnia, is a country at the crossroads of Southern Europe, south and southeast Euro ...

,

Serbia

Serbia (, ; Serbian: , , ), officially the Republic of Serbia ( Serbian: , , ), is a landlocked country in Southeastern and Central Europe, situated at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin and the Balkans. It shares land borders with Hu ...

,

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

,

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

,

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

) and the

former Soviet Union

The post-Soviet states, also known as the former Soviet Union (FSU), the former Soviet Republics and in Russia as the near abroad (russian: links=no, ближнее зарубежье, blizhneye zarubezhye), are the 15 sovereign states that wer ...

(

Moldova

Moldova ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Moldova ( ro, Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south. The unrecognised state of Transnistri ...

,

Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inva ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

,

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

,

Armenia

Armenia (), , group=pron officially the Republic of Armenia,, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of Western Asia.The UNbr>classification of world regions places Armenia in Western Asia; the CIA World Factbook , , and ''O ...

,

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

) also have smaller but still significant numbers of citizens of German descent.

Early Middle Ages settlement area

During the 4th and 5th centuries, in what is known as the

Migration Period, Germanic peoples (ancient Germans) seized control of the decaying

Western Roman Empire

The Western Roman Empire comprised the western provinces of the Roman Empire at any time during which they were administered by a separate independent Imperial court; in particular, this term is used in historiography to describe the period ...

in the South and established new kingdoms within it. Meanwhile, formerly Germanic areas in

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whi ...

and present-day Eastern Germany, were settled by

Slavs.

In the

early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th or early 6th century to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Mi ...

,

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( , ) or Charles the Great ( la, Carolus Magnus; german: Karl der Große; 2 April 747 – 28 January 814), a member of the Carolingian dynasty, was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and the first ...

had subdued a variety of

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

in

Central Europe

Central Europe is an area of Europe between Western Europe and Eastern Europe, based on a common historical, social and cultural identity. The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) between Catholicism and Protestantism significantly shaped the a ...

dwelling in an area roughly bordered by the

Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

in the South, the

Vosges Mountains

The Vosges ( , ; german: Vogesen ; Franconian and gsw, Vogese) are a range of low mountains in Eastern France, near its border with Germany. Together with the Palatine Forest to the north on the German side of the border, they form a single ...

in the West, the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

and

Elbe

The Elbe (; cs, Labe ; nds, Ilv or ''Elv''; Upper and dsb, Łobjo) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Re ...

River in the North and the

Saale

The Saale (), also known as the Saxon Saale (german: Sächsische Saale) and Thuringian Saale (german: Thüringische Saale), is a river in Germany and a left-bank tributary of the Elbe. It is not to be confused with the smaller Franconian Saale ...

River in the East. These inhomogeneous Germanic peoples comprised several tribes and groups who either formed, stayed or migrated into this area during the

Migration Period.

After the

Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–888) was a large Frankish-dominated empire in western and central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the ...

was divided, these people found themselves in the eastern part, known as

East Francia or ''Regnum Teutonicum'', and over time became known as

Germans

, native_name_lang = de

, region1 =

, pop1 = 72,650,269

, region2 =

, pop2 = 534,000

, region3 =

, pop3 = 157,000

3,322,405

, region4 =

, pop4 = ...

. The area was divided into the

stem duchies of

Swabia (

Alamannia),

Franconia

Franconia (german: Franken, ; Franconian dialect: ''Franggn'' ; bar, Frankn) is a region of Germany, characterised by its culture and Franconian languages, Franconian dialect (German: ''Fränkisch'').

The three Regierungsbezirk, administrative ...

,

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

, and

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

(including

Carinthia). Later, the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

would be constituted largely, but not exclusively of these regions.

Medieval settlements (Ostsiedlung)

The medieval German ''

Ostsiedlung'' (literally ''Settling eastwards''), also known as the ''German eastward expansion'' or ''East colonization'' refers to the expansion of German culture, language, states, and settlements to vast regions of Northeastern, Central and Eastern Europe, previously inhabited since the

Great Migrations

''Great Migrations'' is a seven-episode nature documentary television miniseries that airs on the National Geographic Channel, featuring the great migrations of animals around the globe. The seven-part show is the largest programming event in t ...

by

Balts

The Balts or Baltic peoples ( lt, baltai, lv, balti) are an ethno-linguistic group of peoples who speak the Baltic languages of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages.

One of the features of Baltic languages is the number ...

,

Romanians

The Romanians ( ro, români, ; dated exonym '' Vlachs'') are a Romance-speaking ethnic group. Sharing a common Romanian culture and ancestry, and speaking the Romanian language, they live primarily in Romania and Moldova. The 2011 Roman ...

,

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

and, since about the 6th century, the

Slavs. The affected territory stretched roughly from modern

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

in the North to modern

Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

in the South.

Population growth during the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

stimulated the movement of peoples from the

Rhenish,

Flemish

Flemish (''Vlaams'') is a Low Franconian dialect cluster of the Dutch language. It is sometimes referred to as Flemish Dutch (), Belgian Dutch ( ), or Southern Dutch (). Flemish is native to Flanders, a historical region in northern Belgium; ...

, and

Saxon territories of the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

eastwards into the less populated Baltic region and

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

. These movements were supported by the German nobility, the Slavic kings and dukes, and the medieval Church. The majority of this settlement was peaceful, although it sometimes took place at the expense of Slavs and pagan Balts (see

Northern Crusades

The Northern Crusades or Baltic Crusades were Christian colonization and Christianization campaigns undertaken by Catholic Christian military orders and kingdoms, primarily against the pagan Baltic, Finnic and West Slavic peoples around th ...

). ''Ostsiedlung'' accelerated along the Baltic with the advent of the

Teutonic Order

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians on ...

. Likewise, in

Styria and

Carinthia, German communities took form in areas inhabited by

Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( sl, Slovenci ), are a South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia, and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, culture, history and speak Slovene as their na ...

.

In the middle of the 14th century, the settling progress slowed as a result of the

Black Death; in addition, the most arable and promising regions were largely occupied. Local Slavic leaders in late Medieval

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

and

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

continued inviting German settlers to their territories.

In the outcome, all previously

Wendish territory were settled by a German majority and the Wends were almost completely assimilated. In areas further east, substantial German minorities were established, which either kept their customs or were assimilated by the host population. The density of villages and towns increased dramatically.

German town law was introduced to most towns of the area, regardless of the percentage of German inhabitants.

Areas settled during Ostsiedlung

The following areas saw German settlement during the Ostsiedlung:

* within current

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

:

Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 sq ...

,

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (MV; ; nds, Mäkelborg-Vörpommern), also known by its anglicized name Mecklenburg–Western Pomerania, is a state in the north-east of Germany. Of the country's sixteen states, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern ranks 14th in po ...

,

Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

,

Saxony-Anhalt

Saxony-Anhalt (german: Sachsen-Anhalt ; nds, Sassen-Anholt) is a state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony, Thuringia and Lower Saxony. It covers an area of

and has a population of 2.18 million inhabitants, making it th ...

,

Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label=Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of German ...

* the

former eastern territories of Germany

The former eastern territories of Germany (german: Ehemalige deutsche Ostgebiete) refer in present-day Germany to those territories east of the current eastern border of Germany i.e. Oder–Neisse line which historically had been considered Ger ...

:

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

,

East Brandenburg,

East Prussia,

Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. Silesia is split ...

*

Sudetenland (

Sudeten Germans)

*

Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

as well as significant parts of

Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic alphabet, Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and for ...

(especially

Bukovina) and

Wallachia

Wallachia or Walachia (; ro, Țara Românească, lit=The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country, ; archaic: ', Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: ) is a historical and geographical region of Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and s ...

(

Transylvanian Saxons

The Transylvanian Saxons (german: Siebenbürger Sachsen; Transylvanian Saxon: ''Siweberjer Såksen''; ro, Sași ardeleni, sași transilvăneni/transilvani; hu, Erdélyi szászok) are a people of German ethnicity who settled in Transylvania ( ...

)

*

Carpathian Mountains (

Carpathian Germans

Carpathian Germans (german: Karpatendeutsche, Mantaken, hu, kárpátnémetek or ''felvidéki németek'', sk, karpatskí Nemci) are a group of ethnic Germans. The term was coined by the historian Raimund Friedrich Kaindl (1866–1930), originall ...

)

*

Memelland,

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

and

Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

(

Baltic Germans

Baltic Germans (german: Deutsch-Balten or , later ) were ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their coerced resettlement in 1939, Baltic Germans have markedly declin ...

)

*

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

(''see

History of Poland during the Piast dynasty

The period of rule by the Piast dynasty between the 10th and 14th centuries is the first major stage of the history of the Polish state. The dynasty was founded by a series of dukes listed by the chronicler Gall Anonymous in the early 12th cen ...

'')

::

Walddeutsche

Walddeutsche (lit. "Forest Germans" or ''Taubdeutsche'' – "Deaf Germans"; pl, Głuchoniemcy – "deaf Germans") was the name for a group of German-speaking people, originally used in the 16th century for two language islands around Łańcut a ...

*

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Macedo ...

(''see

Germans in Bulgaria )

, population = 436–45,000

, languages = Bulgarian, German

, religions = Roman Catholicism and Protestantism (i.e. Evangelical Lutheranism)

, related-c = German diaspora

Germans ( bg, немци, ''nemtsi'' or ге ...

'')

*

Slovenia

Slovenia ( ; sl, Slovenija ), officially the Republic of Slovenia (Slovene: , abbr.: ''RS''), is a country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the southeast, and ...

(''see

Gottscheers Gottscheers are the German settlers of the Kočevje region (a.k.a. Gottschee) of Slovenia, formerly Gottschee County. Until the Second World War, their main language of communication was Gottscheerish, a Bavarian dialect of German.

Origins

Th ...

'')

* and others

German-run enterprises resulting in German settlements

Hanseatic League

Between the 13th and 17th centuries, trade in the Baltic Sea and Central Europe (beyond Germany) became dominated by German trade through the

Hanseatic League (german: die Hanse). The league was a

Low-German

:

:

:

:

:

(70,000)

(30,000)

(8,000)

, familycolor = Indo-European

, fam2 = Germanic

, fam3 = West Germanic

, fam4 = North Sea Germanic

, ancestor = Old Saxon

, ancestor2 = Middle L ...

-speaking

military alliance

A military alliance is a formal agreement between nations concerning national security. Nations in a military alliance agree to active participation and contribution to the defense of others in the alliance in the event of a crisis. (Online) ...

of

trading

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct excha ...

guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular area. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradesmen belonging to a professional association. They sometimes ...

s that established and maintained a trade

monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situation where a speci ...

over the

Baltic and to a certain extent the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

. Hanseatic towns and trade stations usually hosted relatively large German populations, with merchant dynasties being the wealthiest and political dominant fractions.

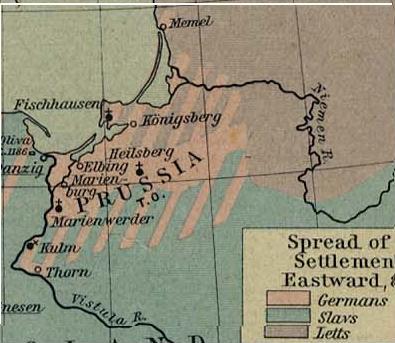

Teutonic Knights

From the second half of the 13th century to the 15th century, the crusading

Teutonic Knights

The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem, commonly known as the Teutonic Order, is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. It was formed to aid Christians o ...

ruled

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

through their

monastic state. As a consequence, German settlement accelerated along the southeastern coast of the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and ...

. These areas, centered around

Gdańsk (Danzig) and

Königsberg

Königsberg (, ) was the historic Prussian city that is now Kaliningrad, Russia. Königsberg was founded in 1255 on the site of the ancient Old Prussian settlement ''Twangste'' by the Teutonic Knights during the Northern Crusades, and was name ...

, remained one of the largest closed German settlement area outside the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

.

17th to 19th century settlements

Thirty Years' War aftermath

When the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

devastated Central Europe, many areas were completely deserted, others suffered severe population drops. These areas were in part resettled by Germans from areas hit less. Some of the deserted villages, however, were not repopulated - that is why the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

' density of settlements was higher than today's.

Poland

In the 16th and 17th centuries, settlers from the Netherlands and Friesland, often of Mennonite faith, founded villages in Royal Prussia, along the Vistula River and its tributaries, and in Kujawy, Mazovia and Wielkopolska. The law under which these villages were organized was called the Dutch or ''Olęder'' law; such villages were called ''Holendry'' or ''Olędry.'' The inhabitants of such villages were called

Olędrzy, regardless of their ethnicity. In fact, the vast majority of Olęder villages in Poland were settled by ethnic Germans, usually

Lutherans

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Catholic Church launched ...

, who spoke the

Low German dialect called

Plautdietsch.

Danube Swabians of Hungary and the Balkans

With the decline of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, German settlers were called into devastated areas of

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

, by then comprising a larger area than today, in the late 17th century. The

Danube Swabians

The Danube Swabians (german: Donauschwaben ) is a collective term for the ethnic German-speaking population who lived in various countries of central-eastern Europe, especially in the Danube River valley, first in the 12th century, and in grea ...

settled in

Swabian Turkey and other areas, more settlers were called in even throughout the 18th century, in part to secure Hungary's frontier with the Ottomans. The

Banat Swabians and

Satu Mare Swabians

The Satu Mare Swabians or Sathmar Swabians (German: Sathmarer Schwaben) are a German ethnic group in the Satu Mare (german: Sathmar) region of Romania.Monica Barcan, Adalbert Millitz, ''The German Nationality in Romania'' (1978), page 42: "The Sa ...

are examples of Danube Swabian settlers from the 18th century.

An influx of Danube Swabians also occurred toward the Adriatic coast in what would later become

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

.

Settlers from

Salzkammergut

The Salzkammergut (; ; bar, Soizkaumaguad, label=Central Austro-Bavarian) is a resort area in Austria, stretching from the city of Salzburg eastwards along the Alpine Foreland and the Northern Limestone Alps to the peaks of the Dachstein Mou ...

were called into Transylvania to repopulate areas devastated by the wars with the Turks. They became known as

Transylvanian Landler

, native_name_lang = German

, image = Sibiu, Transylvania, Evangelische Stadtpfarrkirche, Glasfenster 1908, oesterreichische Protestanten.jpg

, image_caption = Detail of a church window in Sibiu/Hermannstadt dedicated to the memo ...

.

Galicia

After the

First Partition of Poland the

Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence ...

took control of south Poland, later known as

Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria

The Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria,, ; pl, Królestwo Galicji i Lodomerii, ; uk, Королівство Галичини та Володимирії, Korolivstvo Halychyny ta Volodymyrii; la, Rēgnum Galiciae et Lodomeriae also known as ...

. The colonization of the new crown land began afterwards, especially under the rule of

Joseph II

Joseph II (German: Josef Benedikt Anton Michael Adam; English: ''Joseph Benedict Anthony Michael Adam''; 13 March 1741 – 20 February 1790) was Holy Roman Emperor from August 1765 and sole ruler of the Habsburg lands from November 29, 1780 un ...

.

Russian Empire

Since 1762, Russia called in German settlers. Some settled the

Volga

The Volga (; russian: Во́лга, a=Ru-Волга.ogg, p=ˈvoɫɡə) is the longest river in Europe. Situated in Russia, it flows through Central Russia to Southern Russia and into the Caspian Sea. The Volga has a length of , and a catchm ...

area northwest of

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

and therefore became known as

Volga Germans

The Volga Germans (german: Wolgadeutsche, ), russian: поволжские немцы, povolzhskiye nemtsy) are ethnic Germans who settled and historically lived along the Volga River in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov a ...

. Others settled toward the coast of the

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Rom ...

(

Black Sea Germans

The Black Sea Germans (german: Schwarzmeerdeutsche; russian: черноморские немцы; uk, чорноморські німці) are ethnic Germans who left their homelands (starting in the late-18th century, but mainly in the e ...

, including

Bessarabia Germans

The Bessarabia Germans (german: Bessarabiendeutsche, ro, Germani basarabeni, uk, Бессарабські німці) were an ethnic group who lived in Bessarabia (today part of the Republic of Moldova and south-western Ukraine) between 1814 ...

,

Dobrujan Germans The Dobrujan Germans (german: Dobrudschadeutsche) were an ethnic German group, within the larger category of Black Sea Germans, for over one hundred years. German-speaking colonists entered the approximately 23,000 km2 area of Dobruja around 18 ...

, and

Crimea Germans

The Crimea Germans (german: Krimdeutsche) were ethnic German settlers who were invited to settle in the Crimea as part of the East Colonization.

History

From 1783 onwards, there was a systematic settlement of Russians, Ukrainians, and Germans to ...

) and the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, mainly comprising Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia (country), Georgia, and parts of Southern Russia. The Caucasus Mountains, including the Greater Caucasus range ...

area (

Caucasus Germans

Caucasus Germans (german: Kaukasiendeutsche) are part of the German minority in Russia and the Soviet Union. They migrated to the Caucasus largely in the first half of the 19th century and settled in the North Caucasus, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armeni ...

). These settlements occurred throughout the late 18th and the 19th centuries.

In the late 19th century, many

Vistula Germans (or

Olędrzy) immigrated to

Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, as did descendants of early

Mennonite settlers, whose ancestors had lived in

West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

since the

Ostsiedlung.

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

imposed heavy taxes due to their pacifist beliefs. In Russia, they became hence known as

Russian Mennonite

The Russian Mennonites (german: Russlandmennoniten it. "Russia Mennonites", i.e., Mennonites of or from the Russian Empire occasionally Ukrainian Mennonites) are a group of Mennonites who are descendants of Dutch Anabaptists who settled for abo ...

s.

According to the 1926 (1939) census, there were 1,238,000 (1,424,000) Germans living in the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

, respectively.

Turkey

Since the 1840s, Germans moved to

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

who by then had become an ally of the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

. Those settling in the

Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

area became known as

Bosporus Germans.

1871–1914

By the 19th century, every city of even modest size as far east as Russia had a German quarter and a Jewish quarter. Travellers along any road would pass through, for example, a German village, then a Czech village, then a Polish village, etc., depending on the region.

Certain parts of Central and Eastern Europe beyond Germany, especially those close to the border of Germany contained areas in which ethnic Germans constituted a majority.

German Empire and European nationalism

The latter half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century saw the rise of

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

in Europe. Previously, a country consisted largely of whatever peoples lived on the land that was under the dominion of a particular ruler. Thus, as principalities and kingdoms grew through conquest and marriage, a ruler could wind up with peoples of many different ethnicities under his dominion.

The concept of nationalism was based on the idea of a people who shared a common bond through race, religion, language and culture. Furthermore, nationalism asserted that each people had a right to its own nation. Thus, much of European history in the latter half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century can be understood as efforts to realign national boundaries with this concept of "one people, one nation".

In 1871, the

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

was founded, partly as a German nation-state. This is closely associated with chancellor

Otto von Bismarck. While the empire included German settled

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n regions formerly outside of its predecessors, it also included areas with

Danish

Danish may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to the country of Denmark

People

* A national or citizen of Denmark, also called a "Dane," see Demographics of Denmark

* Culture of Denmark

* Danish people or Danes, people with a Danish a ...

,

Kashub and other minorities. In some areas, such as the

Province of Posen or the southern part of

Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( pl, Górny Śląsk; szl, Gůrny Ślůnsk, Gōrny Ślōnsk; cs, Horní Slezsko; german: Oberschlesien; Silesian German: ; la, Silesia Superior) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, locate ...

, the majority of the population were

Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, who share a common history, culture, the Polish language and are identified with the country of Poland in C ...

.

Ethnic German

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

remained outside the empire, and so did many German-settled or mixed regions of Central and Eastern Europe. Most German settled regions of South Central and Southeastern Europe were instead included in the multi-ethnic

Habsburg monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

Ostflucht

Starting in the late 19th century, an inner-Prussian migration took place from the very rural eastern to the prospering urban western

provinces of Prussia (notably to the

Ruhr area

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

and

Cologne

Cologne ( ; german: Köln ; ksh, Kölle ) is the largest city of the German western state of North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW) and the fourth-most populous city of Germany with 1.1 million inhabitants in the city proper and 3.6 millio ...

), a phenomenon termed

Ostflucht

The ''Ostflucht'' (; "flight from the East") was the migration of Germans, in the later 19th century and early 20th century, from areas which were then eastern parts of Germany to more industrialized regions in central and western Germany. The ...

. As a consequence, these migrations increased the percentage of the Polish population in

Posen and

West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

.

Andrzej Chwalba

Andrzej Chwalba (born 1949 in Częstochowa) is a Polish historian. Professor of history at the Jagiellonian University (since 1995), the university's prorector of didactics (1999-2002), head of the Institute of Social and Religious History of Eu ...

- Historia Polski 1795-1918 pages 175-184, 461-463

Driven by nationalist intentions, the

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an e ...

n state established a

Settlement Commission as countermeasure, that was to settle more Germans in these regions. In total 21,886 families (154,704 people) out of planned 40,000 were settled by the end of its existence.

The history of the forced expulsions of the Polish population is further explored in the

Expulsion of Poles by Germany

The Expulsion of Poles by Germany was a prolonged anti-Polish campaign of ethnic cleansing by violent and terror-inspiring means lasting nearly half a century. It began with the concept of Pan-Germanism developed in the early 19th century and culm ...

.

1914–1939

World War I

By

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, there were isolated groups of Germans as far southeast as the

Bosporus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

(

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

),

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, and

Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental country located at the boundary of Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is a part of th ...

. After the war, Germany's and Austria-Hungary's territorial losses meant that more Germans than ever were minorities in various countries, the treatment they received varied from country to country, and they were, in places subject to resentful persecution from former enemies of Germany. Perceptions of this persecution filtered back into Germany, where reports were exploited and amplified by the Nazi party as part of their drive to national popularity as savior of the German people.

The advance of allied

German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

and

Habsburg monarchy forces into the

Russian Empire's territory triggered actions of flight, evacuation and deportation of the population living in or near the combat zone. Russian Germans became subject to severe measures because of their ethnicity, including forced resettlement and deportation to Russia's East, ban of

German language

German ( ) is a West Germanic language mainly spoken in Central Europe. It is the most widely spoken and official or co-official language in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Liechtenstein, and the Italian province of South Tyrol. It is als ...

from public life (including books and newspapers), and denial of economical means (jobs and land property) based on "liquidation laws" issued since 1915; also Germans (as well as the rest of the population) were hit by "scorched earth" tactics of the retreating Russians.

About 300,000 Russian Germans became subject to deportations to

Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive region, geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a ...

and the

Bashkir steppe, of those 70,000-200,000 were Germans from

Volhynia

Volhynia (also spelled Volynia) ( ; uk, Воли́нь, Volyn' pl, Wołyń, russian: Волы́нь, Volýnʹ, ), is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between south-eastern Poland, south-western Belarus, and western Ukraine. The ...

, 20,000 were Germans from

Podolia

Podolia or Podilia ( uk, Поділля, Podillia, ; russian: Подолье, Podolye; ro, Podolia; pl, Podole; german: Podolien; be, Падолле, Padollie; lt, Podolė), is a historic region in Eastern Europe, located in the west-central ...

, 10,000 were Germans from the

Kiev area, and another 11,000 were Germans from the

Chernihiv

Chernihiv ( uk, Черні́гів, , russian: Черни́гов, ; pl, Czernihów, ; la, Czernihovia), is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within ...

area.

From Russian areas controlled by the German, Austrian and Hungarian forces, large scale resettlements of Germans to these areas were organized by ''Fürsorgeverein'' ("Welfare Union"), resettling 60,000 Russian Germans, and ''Deutsche Arbeiterzentrale'' ("German Workers' Bureau"), resettling 25,000-40,000 Russian Germans.

[Jochen Oltmer, ''Migration und Politik in der Weimarer Republik'', 2005, p.154, , 9783525362822] Two thirds of these persons were resettled to

East Prussia, most of the remaining in the northeastern

provinces of Prussia and

Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; nds, label= Low German, Mękel(n)borg ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schweri ...

.

Danzig and the Polish corridor

When Poland regained its independence after

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the Poles hoped to regain the city of Danzig to provide the free access to the sea which they had been promised by the

Allies on the basis of

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

's "

Fourteen Points

U.S. President Woodrow Wilson

The Fourteen Points was a statement of principles for peace that was to be used for peace negotiations in order to end World War I. The principles were outlined in a January 8, 1918 speech on war aims and peace terms ...

". Since the population of the city was predominantly German it was not placed under Polish sovereignty. It became the

Free City of Danzig, an independent quasi-state under the auspices of the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

governed by its German residents but with its external affairs largely under Polish control. The Free City had its own constitution, national anthem, parliament (''Volkstag''), and government (''Senat''). It issued its own stamps and currency, bearing the legend "''Freie Stadt Danzig''" and symbols of the city's maritime orientation and history.

From the

Polish Corridor

The Polish Corridor (german: Polnischer Korridor; pl, Pomorze, Polski Korytarz), also known as the Danzig Corridor, Corridor to the Sea or Gdańsk Corridor, was a territory located in the region of Pomerelia (Pomeranian Voivodeship, easter ...

, many ethnic Germans were forced to leave throughout the 1920s and 1930s, while Poles settled in the region building the sea port city

Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

(Gdingen) next to Danzig.

The vast majority of Danzig's population favoured eventual return to Germany. In the early 1930s the

Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

Party capitalized on these pro-German sentiments, and in 1933 garnered 38 percent of vote for the Danzig ''Volkstag''. Thereafter, the Nazis under the

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

-born

Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a '' Gau'' or '' Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest rank in the Nazi political leadership, subordinate only to '' Reichsleiter'' and to ...

Albert Forster achieved dominance in the city government - which, nominally, was still overseen by the League of Nations' High Commissioner.

Nazi demands, at their minimum, would have seen the return of Danzig to Germany and a one kilometer, state-controlled route for easier access across the Polish Corridor, from

Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pòmòrskô''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to ...

to Danzig (and from there to

East Prussia). Originally, the Poles had rejected this proposal, but later appeared willing to negotiate (as did the British) by August. By this time, however, Hitler had

Soviet backing and had decided to attack Poland. Germany feigned an interest in diplomacy (delaying the ''

Case White'' deadline twice), to try to drive a wedge between Britain and Poland.

Nazi claims to ''Lebensraum'' and resettlements of Germans before the war

In the 19th century, the rise of

romantic nationalism in Germany had led to the concepts of

Pan-Germanism and

Drang nach Osten

(; 'Drive to the East',Ulrich Best''Transgression as a Rule: German–Polish cross-border cooperation, border discourse and EU-enlargement'' 2008, p. 58, , Edmund Jan Osmańczyk, Anthony Mango, ''Encyclopedia of the United Nations and Interna ...

, which in part gave rise to the concept of

Lebensraum

(, ''living space'') is a German concept of settler colonialism, the philosophy and policies of which were common to German politics from the 1890s to the 1940s. First popularized around 1901, '' lso in:' became a geopolitical goal of Imper ...

.

German

nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

used the existence of large German minorities in other countries as a basis for territorial claims. Many of the

propaganda themes of the Nazi regime against

Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

and

Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populou ...

claimed that the ethnic Germans (''

Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

'') in those territories were persecuted. There were many incidents of persecution of Germans in the interwar period, including the French invasion of Germany proper in the 1920s.

The German state was weak until 1933 and could not even protect itself under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles. The status of ethnic Germans, and the lack of contiguity of German majority lands resulted in numerous repatriation pacts whereby the German authorities would organize population transfers (especially the

Nazi-Soviet population transfers arranged between Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, and others with Benito Mussolini's Italy) so that both Germany and the other country would increase their homogeneity.

However, these population transfers were considered but a drop in the pond, and the "

Heim ins Reich" rhetoric over the continued disjoint status of enclaves such as Danzig and Königsberg was an agitating factor in the politics leading up to World War II, and is considered by many to be among the major causes of Nazi aggressiveness and thus the war.

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

used these issues as a pretext for waging wars of aggression against Czechoslovakia and Poland.

Nazi settlement concepts during World War II (1939–45)

The status of ethnic Germans, and the lack of contiguity resulted in numerous repatriation pacts whereby the German authorities would organize population transfers (especially the

Nazi–Soviet population transfers arranged between

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secretar ...

, and others with

Benito Mussolini's Italy) so that both Germany and the other country would increase their "ethnic

homogeneity

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts often used in the sciences and statistics relating to the Uniformity (chemistry), uniformity of a Chemical substance, substance or organism. A material or image that is homogeneous is uniform in compos ...

".

Resettlement of Germans from the Baltic States and Bessarabia

German populations affected by the population exchanges were primarily the

Baltic Germans

Baltic Germans (german: Deutsch-Balten or , later ) were ethnic German inhabitants of the eastern shores of the Baltic Sea, in what today are Estonia and Latvia. Since their coerced resettlement in 1939, Baltic Germans have markedly declin ...

and

Bessarabia Germans

The Bessarabia Germans (german: Bessarabiendeutsche, ro, Germani basarabeni, uk, Бессарабські німці) were an ethnic group who lived in Bessarabia (today part of the Republic of Moldova and south-western Ukraine) between 1814 ...

and others who were forced to resettle west of the

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to ...

. The

Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union that enabled those powers to partition Poland between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ri ...

had defined "spheres of interest", assigning the states between

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

to either one of those.

Except for

Memelland, the

Baltic states were assigned to the Soviet Union, and Germany started pulling out the Volksdeutsche population after reaching respective agreements with

Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, an ...

and

Latvia

Latvia ( or ; lv, Latvija ; ltg, Latveja; liv, Leţmō), officially the Republic of Latvia ( lv, Latvijas Republika, links=no, ltg, Latvejas Republika, links=no, liv, Leţmō Vabāmō, links=no), is a country in the Baltic region of ...

in October 1939. The Baltic Germans were to be resettled in occupied Poland and compensated for their losses with confiscated property at their new settlements. Though resettlement was voluntary, most Germans followed the call because they feared repression once the Soviets would move in.

[Valdis O. Lumans, ''Himmler's Auxiliaries, pp 158ff]

Eventually, this actually happened to the ones who stayed. The Baltic Germans were moved to Germany's northeastern port cities by ship. Poles were expelled from

West Prussia

The Province of West Prussia (german: Provinz Westpreußen; csb, Zôpadné Prësë; pl, Prusy Zachodnie) was a province of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and 1878 to 1920. West Prussia was established as a province of the Kingdom of Prussia in 177 ...

to make space available for resettlement, but due to quarrels with the

Gauleiter

A ''Gauleiter'' () was a regional leader of the Nazi Party (NSDAP) who served as the head of a '' Gau'' or '' Reichsgau''. ''Gauleiter'' was the third-highest rank in the Nazi political leadership, subordinate only to '' Reichsleiter'' and to ...

Albert Forster, resettlement stalled and further "repatriants" were moved to

Posen.

Resettlement of Germans from Italy

On October 6, 1939,

Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

announced a resettlement program for the German-speaking population of the Italian province of

South Tyrol

it, Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige lld, Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol

, settlement_type = Autonomous area, Autonomous Provinces of Italy, province

, image_skyline = ...

. With an initial thought to resettle the population in occupied Poland or the Crimea, they were actually moved to places in nearby

Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. Also affected were German speakers from other areas in northern Italy, like the Kanaltal and

Grödnertal valleys. Resettlement stopped with the collapse of Mussolini's regime and the subsequent occupation of Italy by Nazi Germany.

German "Volksdeutsche" in Nazi-occupied Europe

The actions of Germany ultimately had extremely negative consequences for most ethnic Germans in Central and Eastern Europe (termed

Volksdeutsche

In Nazi German terminology, ''Volksdeutsche'' () were "people whose language and culture had German origins but who did not hold German citizenship". The term is the nominalised plural of '' volksdeutsch'', with ''Volksdeutsche'' denoting a sin ...

to distinguish them from Germans from within the

Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, the

Reichsdeutsche

', literally translated "Germans of the ", is an archaic term for those ethnic Germans who resided within the German state that was founded in 1871. In contemporary usage, it referred to German citizens, the word signifying people from the Germ ...

), who often fought on the side of the Nazi regime - some were drafted, others volunteered or worked through the paramilitary organisations such as

Selbstschutz

''Selbstschutz'' (German for "self-protection") is the name given to different iterations of ethnic-German self-protection units formed both after the First World War and in the lead-up to the Second World War.

The first incarnation of the ''Selb ...

, which supported the German invasion of Poland and murdered tens of thousands of Poles.

In places such as

Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label=Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavija ...

, Germans were drafted by their country of residence, served loyally, and were even held as

POWs by the Nazis, and yet later found themselves drafted again, this time by the Nazis after their takeover. Because it was technically not permissible to draft non-citizens, many ethnic Germans ended up being (oxymoronically) forcibly volunteered for the

Waffen-SS

The (, "Armed SS") was the combat branch of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscripts from both occup ...

. In general, those closest to

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

were the most involved in fighting for her, but the Germans in remote places like the Caucasus were likewise accused of collaboration.

German exodus after Nazi Germany's defeat

The 20th century wars annihilated most Eastern and East Central European German settlements, and the remaining sparse pockets of settlement were subject to emigration to Germany in the late 20th century for economical reasons.

Evacuation, and flight of Germans during the end of World War II

By late 1944, after the Soviet success of the

Belorussian Offensive in August 1944, the Eastern Front became relatively stable. Romania and Bulgaria had been forced to surrender and declare war on Germany. The Germans had lost Budapest and most of the rest of Hungary. The plains of Poland were now open to the Soviet Red Army. Starting on January 12, 1945, the Red Army began the

Vistula–Oder Offensive which was followed a day later by the start of the Red Army's

East Prussian Offensive.

German populations in Central and Eastern Europe took flight from the advancing

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

, resulting in a great population shift. After the final Soviet offensives began in January 1945, hundreds of thousands of German refugees, many of whom had fled to Danzig by foot from

East Prussia (see

evacuation of East Prussia), tried to escape through the city's port in a large-scale evacuation that employed hundreds of German cargo and passenger ships. Some of the ships were sunk by the Soviets, including the ''

Wilhelm Gustloff'', after an evacuation was attempted at neighboring

Gdynia

Gdynia ( ; ; german: Gdingen (currently), (1939–1945); csb, Gdiniô, , , ) is a city in northern Poland and a seaport on the Baltic Sea coast. With a population of 243,918, it is the 12th-largest city in Poland and the second-largest in th ...

. In the process, tens of thousands of refugees were killed.

Cities such as Danzig also endured heavy

Western Allied

The Allies, formally referred to as the Declaration by United Nations, United Nations from 1942, were an international Coalition#Military, military coalition formed during the World War II, Second World War (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis ...

and Soviet bombardment. Those who survived and could not escape encountered the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army ( Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, afte ...

. On 30 March 1945, the Soviets captured the city and left it in ruins.

The Yalta Conference

As it became evident that the Allies were going to defeat Nazi Germany decisively, the question arose as to how to redraw the borders of Central and Eastern European countries after the war. In the context of those decisions, the problem arose of what to do about ethnic minorities within the redrawn borders.

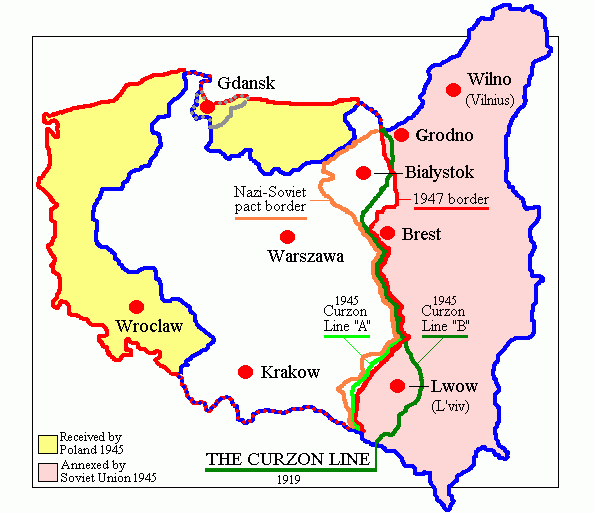

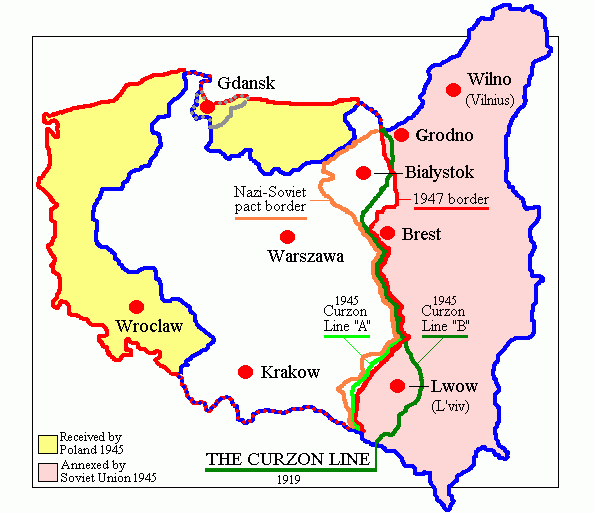

The final decision to move Poland's boundary westward was made by the

US,

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and the Soviets at the

Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (codenamed Argonaut), also known as the Crimea Conference, held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the post ...

, shortly before the end of the war. The precise location of the border was left open. The western Allies also accepted in general the principle of the Oder River as the future western border of Poland and of population transfer as the way to prevent future border disputes. The open question was whether the border should follow the eastern or western Neisse rivers, and whether Stettin, the traditional seaport of Berlin, should remain German or be included in Poland. The western Allies sought to place the border on the eastern Neisse, but Stalin insisted that the border should be on the western Neisse.

The Potsdam Conference

At the

Potsdam Conference

The Potsdam Conference (german: Potsdamer Konferenz) was held at Potsdam in the Soviet occupation zone from July 17 to August 2, 1945, to allow the three leading Allies to plan the postwar peace, while avoiding the mistakes of the Paris P ...

the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union placed the German territories east of the Oder-Neisse line (Poland referred to by the Polish communist government as the "Western Territories" or "

Recovered Territories

The Recovered Territories or Regained Lands ( pl, Ziemie Odzyskane), also known as Western Borderlands ( pl, Kresy Zachodnie), and previously as Western and Northern Territories ( pl, Ziemie Zachodnie i Północne), Postulated Territories ( pl, Z ...

") as formally under Polish administrative control. It was anticipated that a final

peace treaty

A peace treaty is an agreement between two or more hostile parties, usually countries or governments, which formally ends a state of war between the parties. It is different from an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring ...

would follow shortly and either confirm this border or determine whatever alterations might be agreed upon.

The final agreements in effect compensated Poland for 187,000 km

2 located east of the

Curzon Line

The Curzon Line was a proposed demarcation line between the Second Polish Republic and the Soviet Union, two new states emerging after World War I. It was first proposed by The 1st Earl Curzon of Kedleston, the British Foreign Secretary, to ...

with 112,000 km

2 of former German territories. The northerneastern third of East Prussia was directly annexed by the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

and remains part of Russia to this day.