History of Georgia Tech on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology can be traced back to

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology can be traced back to

As noted by a historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus, the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held

As noted by a historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus, the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held  With authorization from the

With authorization from the  McDaniel appointed a commission in January 1886 to organize and run the school. This commission elected Harris chairman, a position he would hold until his death. Other members included Samuel M. Inman, Oliver S. Porter, Judge Columbus Heard, and Edward R. Hodgson; each was known either for political or industrial experience. Their first task was to select a location for the new school. Letters were sent to communities throughout the state, and five bids were presented by the October 1, 1886, deadline:

McDaniel appointed a commission in January 1886 to organize and run the school. This commission elected Harris chairman, a position he would hold until his death. Other members included Samuel M. Inman, Oliver S. Porter, Judge Columbus Heard, and Edward R. Hodgson; each was known either for political or industrial experience. Their first task was to select a location for the new school. Letters were sent to communities throughout the state, and five bids were presented by the October 1, 1886, deadline:

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings, under the leadership of professor and pastor Isaac S. Hopkins. One building (now Tech Tower, the main administrative complex) had classrooms to teach students; the other featured a

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings, under the leadership of professor and pastor Isaac S. Hopkins. One building (now Tech Tower, the main administrative complex) had classrooms to teach students; the other featured a  John Saylor Coon was appointed the first Mechanical Engineering and Drawing Professor at the Georgia School of Technology in 1889. He was also the first chair of the mechanical engineering department.

Coon assumed the role of superintendent of shops in 1896. During his tenure at Georgia Tech, he moved the curriculum away from vocational training. Coon emphasized a balance between the shop and the classroom. Coon taught his students more modern quantification methods to solve engineering problems instead of outdated and more costly trial and error methods. He also played a significant role in developing mechanical engineering into a professional degree program, with a focus on ethics, design and testing, analysis and problem solving, and mathematics.

Tech began its football program with several students forming a loose-knit troop of footballers called the Blacksmiths. The first season saw Tech play three games and lose all three. Discouraged by these results, the Blacksmiths sought a coach to improve their record.

John Saylor Coon was appointed the first Mechanical Engineering and Drawing Professor at the Georgia School of Technology in 1889. He was also the first chair of the mechanical engineering department.

Coon assumed the role of superintendent of shops in 1896. During his tenure at Georgia Tech, he moved the curriculum away from vocational training. Coon emphasized a balance between the shop and the classroom. Coon taught his students more modern quantification methods to solve engineering problems instead of outdated and more costly trial and error methods. He also played a significant role in developing mechanical engineering into a professional degree program, with a focus on ethics, design and testing, analysis and problem solving, and mathematics.

Tech began its football program with several students forming a loose-knit troop of footballers called the Blacksmiths. The first season saw Tech play three games and lose all three. Discouraged by these results, the Blacksmiths sought a coach to improve their record.  The words to Georgia Tech's famous fight song, "

The words to Georgia Tech's famous fight song, "

In 1888,

In 1888,  Hall died on August 16, 1905, during a vacation at a New York health resort. His death while still in office was attributed to stress from his strenuous fundraising activities (this time, for a new chemistry building). Later that year, the school's trustees named the new chemistry building the "Lyman Hall Laboratory of Chemistry" in his honor.

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President

Hall died on August 16, 1905, during a vacation at a New York health resort. His death while still in office was attributed to stress from his strenuous fundraising activities (this time, for a new chemistry building). Later that year, the school's trustees named the new chemistry building the "Lyman Hall Laboratory of Chemistry" in his honor.

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President

Upon his hiring in 1904,

Upon his hiring in 1904,  The bitter rivalry between Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia flared up in 1919, when UGA mocked Tech's continuation of football during the United States' involvement in World War I. Because Tech was a military training ground, it had a complete assembly of male students. Many schools, such as UGA, lost all of their able-bodied male students to the war effort, forcing them to temporarily suspend football during the war. In fact, UGA did not play a game from 1917 to 1918.

When UGA renewed its program in 1919, their student body staged a parade which mocked Tech's continuation of football during times of war. The parade featured a

The bitter rivalry between Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia flared up in 1919, when UGA mocked Tech's continuation of football during the United States' involvement in World War I. Because Tech was a military training ground, it had a complete assembly of male students. Many schools, such as UGA, lost all of their able-bodied male students to the war effort, forcing them to temporarily suspend football during the war. In fact, UGA did not play a game from 1917 to 1918.

When UGA renewed its program in 1919, their student body staged a parade which mocked Tech's continuation of football during times of war. The parade featured a  In its first decades, Georgia Tech slowly grew from a trade school into a university. The state and federal governments provided little initiative for the school to grow significantly until 1919. That year, the Georgia General Assembly passed an act entitled "Establishing State Engineering Experiment Station at the Georgia School of Technology". This change coincided with federal debate about the establishment of Engineering Experiment Stations in a move similar to the

In its first decades, Georgia Tech slowly grew from a trade school into a university. The state and federal governments provided little initiative for the school to grow significantly until 1919. That year, the Georgia General Assembly passed an act entitled "Establishing State Engineering Experiment Station at the Georgia School of Technology". This change coincided with federal debate about the establishment of Engineering Experiment Stations in a move similar to the

On August 1, 1922, Marion L. Brittain was elected as the school's president. He noted in the 1923 annual report that "there are more students in Georgia Tech than in any other two colleges in Georgia, and we have the smallest appropriation of them all." He was able to convince the state of Georgia to increase the school's funding during his tenure. Additionally, a $300,000 grant () from the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics allowed Brittain to establish the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics. In 1930, Brittain's decision to use the money for a new school of aeronautics, headed by Montgomery Knight, was controversial; today, the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering boasts the second largest faculty in the United States behind MIT. Other accomplishments during Brittain's administration included a doubling of Georgia Tech's enrollment,

On August 1, 1922, Marion L. Brittain was elected as the school's president. He noted in the 1923 annual report that "there are more students in Georgia Tech than in any other two colleges in Georgia, and we have the smallest appropriation of them all." He was able to convince the state of Georgia to increase the school's funding during his tenure. Additionally, a $300,000 grant () from the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics allowed Brittain to establish the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics. In 1930, Brittain's decision to use the money for a new school of aeronautics, headed by Montgomery Knight, was controversial; today, the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering boasts the second largest faculty in the United States behind MIT. Other accomplishments during Brittain's administration included a doubling of Georgia Tech's enrollment,  The

The  The EES's early work was conducted in the basement of the Shop Building, and Vaughan's office was in the Aeronautical Engineering Building. By 1938, the EES was producing useful technology, and the station needed a method to conduct contract work outside of the state budget. Consequently, the Industrial Development Council (IDC) was formed. It was created by the Chancellor of the university system and the president of

The EES's early work was conducted in the basement of the Shop Building, and Vaughan's office was in the Aeronautical Engineering Building. By 1938, the EES was producing useful technology, and the station needed a method to conduct contract work outside of the state budget. Consequently, the Industrial Development Council (IDC) was formed. It was created by the Chancellor of the university system and the president of

Founded as the ''Georgia School of Technology'', the school assumed its present name on July 1, 1948, to reflect a growing focus on advanced technological and scientific research. The name change was first proposed on June 12, 1906, but did not gain momentum until Blake R. Van Leer's presidency. Unlike similarly named universities such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology, the Georgia Institute of Technology is a

Founded as the ''Georgia School of Technology'', the school assumed its present name on July 1, 1948, to reflect a growing focus on advanced technological and scientific research. The name change was first proposed on June 12, 1906, but did not gain momentum until Blake R. Van Leer's presidency. Unlike similarly named universities such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology, the Georgia Institute of Technology is a

Enraged, Tech students organized an impromptu protest rally on campus. At midnight, a large group of students hung the governor in effigy and ignited a bonfire. They then marched to Five Points, the

Enraged, Tech students organized an impromptu protest rally on campus. At midnight, a large group of students hung the governor in effigy and ignited a bonfire. They then marched to Five Points, the

Around 1960, state law mandated "an immediate cut-off of state funds to any white institution that admitted a black student". At a meeting in the Old Gym on January 17, 1961, an overwhelming majority of the 2,741 students present voted to endorse integration of qualified applicants, regardless of race. Three years after the meeting, and one year after the University of Georgia's violent integration, Georgia Tech became the first university in the

Around 1960, state law mandated "an immediate cut-off of state funds to any white institution that admitted a black student". At a meeting in the Old Gym on January 17, 1961, an overwhelming majority of the 2,741 students present voted to endorse integration of qualified applicants, regardless of race. Three years after the meeting, and one year after the University of Georgia's violent integration, Georgia Tech became the first university in the  James E. Boyd, assistant director of Research at the Engineering Experiment Station since 1954, was appointed Director of the station from July 1, 1957, a post in which he served until 1961. While at Tech, Boyd wrote an influential article about the role of research centers at institutes of technology, which argued that research should be integrated with education; he correspondingly involved undergraduates in his research. Under Boyd's purview, the EES gained many electronics-related contracts, to the extent that an Electronics Division was created in 1959; it would focus on radar and communications. The establishment of research facilities was also championed by Boyd. In 1955, Van Leer had appointed Boyd to Georgia Tech's Nuclear Science Committee, which recommended the creation of a Radioisotopes Laboratory Facility and a large research reactor. The $4.5 million ($ million in ) Frank H. Neely Research Reactor would be completed in 1963 and would operate until 1996.

Harrison's administration also addressed the disparity between salaries at Georgia Tech and competing institutions. This was solved via the "Joint Tech-Georgia Development Fund" developed by the

James E. Boyd, assistant director of Research at the Engineering Experiment Station since 1954, was appointed Director of the station from July 1, 1957, a post in which he served until 1961. While at Tech, Boyd wrote an influential article about the role of research centers at institutes of technology, which argued that research should be integrated with education; he correspondingly involved undergraduates in his research. Under Boyd's purview, the EES gained many electronics-related contracts, to the extent that an Electronics Division was created in 1959; it would focus on radar and communications. The establishment of research facilities was also championed by Boyd. In 1955, Van Leer had appointed Boyd to Georgia Tech's Nuclear Science Committee, which recommended the creation of a Radioisotopes Laboratory Facility and a large research reactor. The $4.5 million ($ million in ) Frank H. Neely Research Reactor would be completed in 1963 and would operate until 1996.

Harrison's administration also addressed the disparity between salaries at Georgia Tech and competing institutions. This was solved via the "Joint Tech-Georgia Development Fund" developed by the  James E. Boyd, who had assumed the vice chancellorship of the University System of Georgia the previous month, was appointed Acting President of Georgia Tech by Chancellor George L. Simpson in May 1971. Simpson's selection of Boyd as interim president was influenced by Boyd's previous experience as an academic administrator, his experience as director of the Engineering Experiment Station, and his ongoing position on the station's board of directors. The chancellor hoped this combination would help resolve a brewing controversy over whether the EES should be integrated into Georgia Tech's academic units to improve both entities' competitiveness for federal money.

The EES had sizable and growing support from the state of Georgia and its Industrial Development Council, which developed products and methods and provided technical assistance for Georgia industry. However, due in part to efforts made by Boyd and previous station director Gerald Rosselot, the station increasingly relied on electronics research funding from the federal government. In 1971, funding to both Georgia Tech's academic units and the EES began to suffer due to a sharp decline in state funds combined with cuts to federal science, research, and education funding after the end of the

James E. Boyd, who had assumed the vice chancellorship of the University System of Georgia the previous month, was appointed Acting President of Georgia Tech by Chancellor George L. Simpson in May 1971. Simpson's selection of Boyd as interim president was influenced by Boyd's previous experience as an academic administrator, his experience as director of the Engineering Experiment Station, and his ongoing position on the station's board of directors. The chancellor hoped this combination would help resolve a brewing controversy over whether the EES should be integrated into Georgia Tech's academic units to improve both entities' competitiveness for federal money.

The EES had sizable and growing support from the state of Georgia and its Industrial Development Council, which developed products and methods and provided technical assistance for Georgia industry. However, due in part to efforts made by Boyd and previous station director Gerald Rosselot, the station increasingly relied on electronics research funding from the federal government. In 1971, funding to both Georgia Tech's academic units and the EES began to suffer due to a sharp decline in state funds combined with cuts to federal science, research, and education funding after the end of the  Boyd had to deal with intense public pressure to fire Yellow Jackets football coach

Boyd had to deal with intense public pressure to fire Yellow Jackets football coach

In October 1990, Tech opened its first overseas campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine (GTL). A non-profit corporation operating under French law, GTL primarily focuses on graduate education, sponsored research, and an undergraduate summer program. In 1997 GTL was sued on the grounds that the course descriptions on its internet site did not comply with the Toubon Law, which requires that advertisements must be provided in French. The case was dismissed on a technicality; the GTL site subsequently offers course descriptions in English, French and German.

Crecine was instrumental in securing the

In October 1990, Tech opened its first overseas campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine (GTL). A non-profit corporation operating under French law, GTL primarily focuses on graduate education, sponsored research, and an undergraduate summer program. In 1997 GTL was sued on the grounds that the course descriptions on its internet site did not comply with the Toubon Law, which requires that advertisements must be provided in French. The case was dismissed on a technicality; the GTL site subsequently offers course descriptions in English, French and German.

Crecine was instrumental in securing the

In 1994,

In 1994,  The master plan for the school's physical growth and development—created in 1912 and significantly revised in 1952, 1965, and 1991—saw two further revisions under Clough's guidance in 1997 and 2002. While Clough was in office, around $1 billion was spent on expanding and improving the campus. These projects include the construction of the Manufacturing Related Disciplines Complex, 10th and Home, Tech Square, The Biomedical Complex, the completion and subsequent renovations of several west campus dorms, the Student Center renovation, the expanded 5th Street Bridge, the Georgia Tech Aquatic Center's renovation into the CRC, the new Health Center, the Klaus Advanced Computing Building, the Molecular Science and Engineering Building, and the Nanotechnology Research Center.

The school has also taken care to maintain its Historic District, with several projects dedicated to the preservation or improvement of Tech Tower, the school's first and oldest building and its primary administrative center. As part of Phase I of the Georgia Tech Master Plan of 1997, the area was made more pedestrian-friendly by the removal of access roads and the addition of landscaping improvements, benches, and other facilities. The

The master plan for the school's physical growth and development—created in 1912 and significantly revised in 1952, 1965, and 1991—saw two further revisions under Clough's guidance in 1997 and 2002. While Clough was in office, around $1 billion was spent on expanding and improving the campus. These projects include the construction of the Manufacturing Related Disciplines Complex, 10th and Home, Tech Square, The Biomedical Complex, the completion and subsequent renovations of several west campus dorms, the Student Center renovation, the expanded 5th Street Bridge, the Georgia Tech Aquatic Center's renovation into the CRC, the new Health Center, the Klaus Advanced Computing Building, the Molecular Science and Engineering Building, and the Nanotechnology Research Center.

The school has also taken care to maintain its Historic District, with several projects dedicated to the preservation or improvement of Tech Tower, the school's first and oldest building and its primary administrative center. As part of Phase I of the Georgia Tech Master Plan of 1997, the area was made more pedestrian-friendly by the removal of access roads and the addition of landscaping improvements, benches, and other facilities. The  On September 16, 2017, Scout Schultz, a 21-year-old student at the institute, was shot dead by a Georgia Tech Police officer on campus, in what appeared to be a

On September 16, 2017, Scout Schultz, a 21-year-old student at the institute, was shot dead by a Georgia Tech Police officer on campus, in what appeared to be a

Georgia Institute of Technology Campus Historic Preservation Plan Update 2009

* Pictures of Original Shop and Administration Buildings circa 188

Photo1

http://history.library.gatech.edu/items/show/1411 Photo2]

Georgia Tech Integration

Civil Rights Digital Library. {{good article Georgia Tech, History of Georgia Tech

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology can be traced back to

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology can be traced back to Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

-era plans to develop the industrial base of the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Founded on October 13, 1885, in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

as the Georgia School of Technology, the university opened in 1888 after the construction of Tech Tower and a shop building and only offered one degree in mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering is the study of physical machines that may involve force and movement. It is an engineering branch that combines engineering physics and mathematics principles with materials science, to design, analyze, manufacture, ...

. By 1901, degrees in electrical

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

, civil, textile

Textile is an Hyponymy and hypernymy, umbrella term that includes various Fiber, fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, Staple (textiles)#Filament fiber, filaments, Thread (yarn), threads, different #Fabric, fabric types, etc. At f ...

, and chemical engineering

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials in ...

were also offered. In 1948, the name was changed to the Georgia Institute of Technology to reflect its evolution from an engineering school to a full technical institute and research university

A research university or a research-intensive university is a university that is committed to research as a central part of its mission. They are the most important sites at which knowledge production occurs, along with "intergenerational kn ...

.

The Georgia Institute of Technology

The Georgia Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Georgia Tech or, in the state of Georgia, as Tech or The Institute, is a public research university and institute of technology in Atlanta, Georgia. Established in 1885, it is part ...

(Georgia Tech) is the birthplace of two other Georgia universities: Georgia State University

Georgia State University (Georgia State, State, or GSU) is a public research university in Atlanta, Georgia. Founded in 1913, it is one of the University System of Georgia's four research universities. It is also the largest institution of hig ...

and the former Southern Polytechnic State University. Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce, established in 1912 and moved to the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

in 1931, was independently established as Georgia State University in 1955. Although Georgia Tech did not officially allow women to enroll until 1952 (and did not fully integrate the curriculum until 1968), the night school enrolled female students as early as the fall of 1917. The Southern Technical Institute (now Southern Polytechnic College of Engineering and Engineering Technology of Kennesaw State University and formerly known as Southern Polytechnic State University) was founded by president Blake R. Van Leer as an extension of Georgia Tech in 1948 as a technical trade school for World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

veterans and became an independent university in 1981.

The Great Depression saw a consistent squeeze on Georgia Tech's budget, but World War II–inspired research activity combined with post–World War II enrollment more than compensated for the school's difficulties. Georgia Tech desegregated peacefully and without a court order in 1961, in contrast to other southern universities. Similarly, it did not experience any protests due to the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. The growth of the graduate and research programs combined with diminishing federal support for universities in the 1980s led President John Patrick Crecine

John Patrick "Pat" Crecine (August 22, 1939 – April 28, 2008) was an American educator and economist who served as President of Georgia Tech, Dean at Carnegie Mellon University, business executive, and professor. After receiving his early ...

to restructure the university in 1988 amid significant controversy. The 1990s were marked by continued expansion of the undergraduate programs and the satellite campuses in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and is the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Br ...

, and Metz

Metz ( , , lat, Divodurum Mediomatricorum, then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle and the Seille rivers. Metz is the prefecture of the Moselle department and the seat of the parliament of the Grand ...

, France. In 1996, Georgia Tech was the site of the athletes' village and a venue for a number of athletic events for the Summer Olympics

The Summer Olympic Games (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques d'été), also known as the Games of the Olympiad, and often referred to as the Summer Olympics, is a major international multi-sport event normally held once every four years. The ina ...

. Recently, the school has gradually improved its academic rankings and has paid significant attention to modernizing the campus, increasing historically low retention rates, and establishing degree options emphasizing research and international perspectives.

Establishment (Before 1888)

As noted by a historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus, the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held

As noted by a historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus, the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere ...

s built to protect Atlanta during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

. The surrender of the city took place on the southwestern boundary of the modern Georgia Tech campus in 1864. The next twenty years were a time of rapid industrial expansion; during this period, Georgia's manufacturing capital, railroad track mileage, and property values would each increase by a factor of three to four.

The establishment of a school of technology was proposed in 1882 during the Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

* Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

period. Major

Major ( commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicato ...

John Fletcher Hanson and Nathaniel Edwin Harris

Nathaniel Edwin Harris (January 21, 1846 – September 21, 1929) was an American lawyer and politician, and the 61st Governor of Georgia.

Early life

Harris was born in Jonesboro, Tennessee on January 21, 1846 to Edna (née Haynes) and Alexa ...

, two former Confederate officers who became prominent citizens in the town of Macon, Georgia, after the war, strongly believed that the South needed to improve its technology to compete with the industrial revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

that was occurring throughout the North. Many Southerners at this time agreed with this idea, known as the " New South Creed". Its strongest proponent was Henry W. Grady, editor of ''The Atlanta Constitution

''The Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the only major daily newspaper in the metropolitan area of Atlanta, Georgia. It is the flagship publication of Cox Enterprises. The ''Atlanta Journal-Constitution'' is the result of the merger between ...

'' during the 1880s. A technology school was thought necessary because the American South of that era was mostly agrarian, and few technical developments were occurring. Georgians needed technical training to advance the state's industry.

With authorization from the

With authorization from the Georgia General Assembly

The Georgia General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is bicameral, consisting of the Senate and the House of Representatives.

Each of the General Assembly's 236 members serve two-year terms and are direct ...

, Harris and a committee of prominent Georgians visited renowned technology schools in the Northeast in 1883; these included the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of th ...

(MIT), the Worcester Polytechnic Institute

Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) is a Private university, private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts. Founded in 1865 in Worcester, WPI was one of the United States' first engineering and technology universities and now has 14 ac ...

, Stevens Institute of Technology

Stevens Institute of Technology is a private research university in Hoboken, New Jersey. Founded in 1870, it is one of the oldest technological universities in the United States and was the first college in America solely dedicated to mechanical ...

, and Cooper Union

The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art (Cooper Union) is a private college at Cooper Square in New York City. Peter Cooper founded the institution in 1859 after learning about the government-supported École Polytechnique ...

. Using these examples, the committee reported that the Worcester model, which stressed a combination of "theory and practice was the embodiment of the best conception of industrial education". The "practice" component of the Worcester model included student employment and production of consumer items to generate revenue for the school.

When the committee returned, they submitted their findings to the Georgia General Assembly as House Bill 732 on July 24, 1883. The bill, written by Harris, met significant opposition from various sources and was defeated. Reasons for opposition included the general resistance to education, specifically technical education, concerns voiced by agricultural interests, and fiscal concerns relating to the limited treasury of the Georgia government; the state's 1877 constitution prohibited spending beyond its means as a reactionary measure to excessive spending by "carpetbaggers

In the history of the United States, carpetbagger is a largely historical term used by Southerners to describe opportunistic Northerners who came to the Southern states after the American Civil War, who were perceived to be exploiting the ...

and Negro leaders".

In February 1883, Harris submitted a second version, this time with the support of contemporary political leaders Joseph M. Terrell and R. B. Russell as well as the popular support of the influential State Agricultural Society and the leaders of the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

, the latter of which would be the "parent college" of any state technical school. In 1885, House Bill 732 was submitted and passed the House 94–62. The bill was passed in the Senate with two amendments, and the amended bill was defeated in the House 65–53. After back-room work by Harris, the bill finally passed 69–44. On October 13, 1885, Georgia Governor Henry D. McDaniel signed the bill to create and fund the new school. The legislature then established a committee to determine the location of the new school. The school was officially established, and subsequent efforts to repeal the law were suppressed by supporter and Speaker of the House W. A. Little.

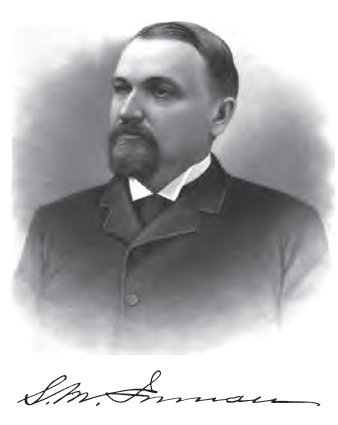

McDaniel appointed a commission in January 1886 to organize and run the school. This commission elected Harris chairman, a position he would hold until his death. Other members included Samuel M. Inman, Oliver S. Porter, Judge Columbus Heard, and Edward R. Hodgson; each was known either for political or industrial experience. Their first task was to select a location for the new school. Letters were sent to communities throughout the state, and five bids were presented by the October 1, 1886, deadline:

McDaniel appointed a commission in January 1886 to organize and run the school. This commission elected Harris chairman, a position he would hold until his death. Other members included Samuel M. Inman, Oliver S. Porter, Judge Columbus Heard, and Edward R. Hodgson; each was known either for political or industrial experience. Their first task was to select a location for the new school. Letters were sent to communities throughout the state, and five bids were presented by the October 1, 1886, deadline: Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates a ...

, Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,7 ...

, Macon, Penfield, and Milledgeville. The commission inspected the proposed sites from October 7 to October 18. Patrick Hues Mell, the president of the University of Georgia at that time, believed that it should be located in Athens with the university's main campus, like the Agricultural and Mechanical Schools.

The committee members voted exclusively for their respective home cities until the 21st ballot when Porter switched to Atlanta; on the 24th ballot, Atlanta finally emerged victorious. Students at the University of Georgia burned Judge Heard in effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

after the final vote was announced. Atlanta's bid included US$50,000 from the city, $20,000 from private citizens (including $5,000 from Samuel M. Inman), and $2,500 in guaranteed yearly support, along with a gift of of land from Atlanta pioneer Richard Peters instead of the initially proposed site in Atlanta's bid, which was near land that Lemuel P. Grant was developing, including Grant Park.

The school's new location was bounded on the south by North Avenue, and on the west by Cherry Street. Peters sold five adjoining acres of land to the state for $10,000. This land was situated on what was then Atlanta's northern city limits. The act that created the school had also appropriated $65,000 towards the construction of new buildings.

Early years (1888–1896)

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings, under the leadership of professor and pastor Isaac S. Hopkins. One building (now Tech Tower, the main administrative complex) had classrooms to teach students; the other featured a

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings, under the leadership of professor and pastor Isaac S. Hopkins. One building (now Tech Tower, the main administrative complex) had classrooms to teach students; the other featured a workshop

Beginning with the Industrial Revolution era, a workshop may be a room, rooms or building which provides both the area and tools (or machinery) that may be required for the manufacture or repair of manufactured goods. Workshops were the ...

with a foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

, forge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to th ...

, boiler room, and engine room

On a ship, the engine room (ER) is the compartment where the machinery for marine propulsion is located. To increase a vessel's safety and chances of surviving damage, the machinery necessary for the ship's operation may be segregated into var ...

. It was designed specifically as a "contract shop" where students would work to produce goods to sell, creating revenue for the school while the students learned vocational skills in a "hands-on" manner. Such a method was seen as appropriate given the Southern United States' need for industrial development. The two buildings were equal in size and staffing (five professors and five shop supervisors) to show the importance of teaching both the mind and the hands. At the time, there was some disagreement as to whether the machine shop should have been used to turn a profit. The contract shop system ended in 1896 due to its lack of profitability, after which point the items produced were used to furnish the offices and dorms on the campus.

The first class of students at the Georgia School of Technology was small and homogeneous, and educational options were limited. Eighty-five students signed up on the first registration day, October 7, 1888, and the enrollment for the first year climbed to a total of 129 by January 7, 1889. The first student to register was William H. Glenn. All but one or two of the students were from Georgia. Tuition was free for Georgia residents and $150 () for out-of-state students. The only degree offered was a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

in mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering is the study of physical machines that may involve force and movement. It is an engineering branch that combines engineering physics and mathematics principles with materials science, to design, analyze, manufacture, ...

, and no elective courses were available. All students were required to follow exactly the same program, which was so rigorous that nearly two thirds of the first class failed to complete it. The first graduating class consisted of two students in 1890, Henry L. Smith and George G. Crawford, who decided their graduation order on the flip of a coin.

John Saylor Coon was appointed the first Mechanical Engineering and Drawing Professor at the Georgia School of Technology in 1889. He was also the first chair of the mechanical engineering department.

Coon assumed the role of superintendent of shops in 1896. During his tenure at Georgia Tech, he moved the curriculum away from vocational training. Coon emphasized a balance between the shop and the classroom. Coon taught his students more modern quantification methods to solve engineering problems instead of outdated and more costly trial and error methods. He also played a significant role in developing mechanical engineering into a professional degree program, with a focus on ethics, design and testing, analysis and problem solving, and mathematics.

Tech began its football program with several students forming a loose-knit troop of footballers called the Blacksmiths. The first season saw Tech play three games and lose all three. Discouraged by these results, the Blacksmiths sought a coach to improve their record.

John Saylor Coon was appointed the first Mechanical Engineering and Drawing Professor at the Georgia School of Technology in 1889. He was also the first chair of the mechanical engineering department.

Coon assumed the role of superintendent of shops in 1896. During his tenure at Georgia Tech, he moved the curriculum away from vocational training. Coon emphasized a balance between the shop and the classroom. Coon taught his students more modern quantification methods to solve engineering problems instead of outdated and more costly trial and error methods. He also played a significant role in developing mechanical engineering into a professional degree program, with a focus on ethics, design and testing, analysis and problem solving, and mathematics.

Tech began its football program with several students forming a loose-knit troop of footballers called the Blacksmiths. The first season saw Tech play three games and lose all three. Discouraged by these results, the Blacksmiths sought a coach to improve their record. Leonard Wood

Leonard Wood (October 9, 1860 – August 7, 1927) was a United States Army major general, physician, and public official. He served as the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, Military Governor of Cuba, and Governor-General of the Philipp ...

, an army officer who had played football at Harvard and was then stationed in Atlanta and taking graduate courses at the school, volunteered to serve as the team's player-coach. In 1893, Tech played its first game against the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

(Georgia). Tech defeated Georgia 28–6 for the school's first-ever victory. The angry Georgia fans threw stones and other debris at the Tech players during and after the game. The poor treatment of the Blacksmiths by the Georgia faithful gave birth to the rivalry now known as Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate

Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate is an American college football rivalry between the Georgia Bulldogs and the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets. The two Southern universities are located in the U.S. state of Georgia and are separated by . They have been he ...

.

The words to Georgia Tech's famous fight song, "

The words to Georgia Tech's famous fight song, "Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech

"(I'm a) Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech" is the fight song of the Georgia Institute of Technology, better known as Georgia Tech. The composition is based on "Son of a Gambolier", composed by Charles Ives in 1895, the lyrics of which are bas ...

", are said to have come from an early baseball game against rival Georgia. Some sources credit Billy Walthall, a member of the first four-year graduating class, with the lyrics. According to a 1954 article in ''Sports Illustrated

''Sports Illustrated'' (''SI'') is an American sports magazine first published in August 1954. Founded by Stuart Scheftel, it was the first magazine with circulation over one million to win the National Magazine Award for General Excellence tw ...

'', "Ramblin' Wreck" was written around 1893 by a Tech football player on his way to an Auburn game. In 1905, Georgia Tech adopted it in roughly the current form as its official fight song, although it had apparently been the unofficial fight song for several years. It was published for the first time in the school's first yearbook, the 1908 '' Blue Print'', under the heading "What causes Whitlock to Blush." Words such as "hell" and "helluva" were censored in this first printing as "certain words retoo hot to print." After Michael A. Greenblatt, the first bandmaster

A bandmaster is the leader and conductor of a band, usually a concert band, military band, brass band or a marching band.

British Armed Forces

In the British Army, bandmasters of the Royal Corps of Army Music now hold the rank of staff ...

of the Georgia Tech Marching Band, heard the band playing the song to the tune of Charles Ives's "A Son of a Gambolier", he wrote a modern musical version. In 1911, Frank Roman succeeded Greenblatt as bandmaster; Roman embellished the song with trumpet flourishes and publicized it. Roman copyrighted the song in 1919.

Tech's first student publication was the ''Technologian'', which ran for a short time in 1891. The next student publication was ''The Georgia Tech'', established in 1894. ''The Georgia Tech'' published a "Commencement Issue" that reviewed sporting events and gave information about each class. '' The Technique'' was founded in 1911; its first issue was published on November 17, 1911, by editors Albert Blohm and E. A. Turner, and the content revolved around the upcoming rivalry football game against the University of Georgia. The ''Technique'' has been published weekly ever since, with the exception of a brief period during which the paper was published twice weekly. ''The Georgia Tech'' was merged into the ''Technique'' in 1916.

Engineering school (1896–1905)

In 1888,

In 1888, Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Lyman Hall

Lyman Hall (April 12, 1724 – October 19, 1790) was an American Founding Father, physician, clergyman, and statesman who signed the United States Declaration of Independence as a representative of Georgia. Hall County is named after him. He ...

was appointed Georgia Tech's first mathematics professor, a position he held until his appointment as the school's second president in 1896. Hall had a solid background in engineering due to his time at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

and often incorporated surveying and other engineering applications into his coursework. He had an energetic personality and quickly assumed a leadership position among the faculty. As president, Hall was noted for his aggressive fundraising and improvements to the school, including his special project, the A. French Textile School. In February 1899, Georgia Tech opened the first textile engineering

Textile Manufacturing or Textile Engineering is a major industry. It is largely based on the conversion of fibre into yarn, then yarn into fabric. These are then dyed or printed, fabricated into cloth which is then converted into useful goods ...

school in the Southern United States, with $10,000 from the Georgia General Assembly, $20,000 of donated machinery, and $13,500 from supporters. It named the A. French Textile School after its chief donor and supporter, Aaron S. French. The textile engineering program would move to the Harrison Hightower Textile Engineering Building in 1949.

Hall's other goals included enlarging Tech and attracting more students, so he expanded the school's offerings beyond mechanical engineering; new degrees introduced during Hall's administration included electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

and civil engineering

Civil engineering is a professional engineering discipline that deals with the design, construction, and maintenance of the physical and naturally built environment, including public works such as roads, bridges, canals, dams, airports, sewa ...

in December 1896, textile engineering in February 1899, and engineering chemistry

Chemical engineering is an engineering field which deals with the study of operation and design of chemical plants as well as methods of improving production. Chemical engineers develop economical commercial processes to convert raw materials int ...

in January 1901. Hall also became infamous as a disciplinarian, even suspending the entire senior class of 1901 for returning from Christmas vacation a day late.

Hall died on August 16, 1905, during a vacation at a New York health resort. His death while still in office was attributed to stress from his strenuous fundraising activities (this time, for a new chemistry building). Later that year, the school's trustees named the new chemistry building the "Lyman Hall Laboratory of Chemistry" in his honor.

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President

Hall died on August 16, 1905, during a vacation at a New York health resort. His death while still in office was attributed to stress from his strenuous fundraising activities (this time, for a new chemistry building). Later that year, the school's trustees named the new chemistry building the "Lyman Hall Laboratory of Chemistry" in his honor.

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

visited the Georgia Tech campus. On the steps of Tech Tower, Roosevelt presented a speech about the importance of technological education:

Roosevelt then shook hands with every student. Tech was later visited by president-elect William H. Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

on January 16, 1909, and president Franklin D. Roosevelt on November 29, 1935.

World War I (1905–1922)

Upon his hiring in 1904,

Upon his hiring in 1904, John Heisman

John William Heisman (October 23, 1869 – October 3, 1936) was a player and coach of American football, baseball, and basketball, as well as a sportswriter and actor. He served as the head football coach at Oberlin College, Buchtel College ...

(for whom the Heisman Trophy

The Heisman Memorial Trophy (usually known colloquially as the Heisman Trophy or The Heisman) is awarded annually to the most outstanding player in college football. Winners epitomize great ability combined with diligence, perseverance, and har ...

is named) insisted that the school acquire its own football field. Previously, the team had used area parks, especially the playing fields of Piedmont Park

Piedmont Park is an urban park in Atlanta, Georgia, located about northeast of Downtown, between the Midtown and Virginia Highland neighborhoods. Originally the land was owned by Dr. Benjamin Walker, who used it as his out-of-town gentlema ...

. Georgia Tech took out a seven-year lease on what is now the southern end of Grant Field, although the land was not adequate for sports, due to its unleveled, rocky nature. In 1905, Heisman had 300 convict laborers clear rocks, remove tree stumps, and level out the field for play; Tech students then built a grandstand on the property. The land was purchased by 1913, and John W. Grant

John W. Grant (July 26, 1867, West Point, Georgia – March 8, 1938) was a member of the Georgia School of Technology board of trustees and a well-known Atlanta, Georgia, merchant around the 1880s.

He was the grandson of John T. Grant and the ...

donated $15,000 () towards the construction of the field's first permanent stands. The field was named Grant Field in honor of the donor's deceased son, Hugh Inman Grant.

Attempts at forming an alumni association had been made since 1896; a charter was applied for by J. B. McCrary and William H. Glenn on June 28, 1906, and was approved by Fulton County on June 20, 1908. The Georgia Tech Alumni Association

The Georgia Tech Alumni Association is the official alumni association for the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech). Originally known as the Georgia Tech National Alumni Association, it was chartered in June 1908 and incorporated in 1947. ...

published its first annual report in 1908, but the group was largely dormant during World War I. The organization played an important role in the 1920s Greater Georgia Tech Campaign, which consolidated all existing alumni clubs and funded a significant expansion of Georgia Tech's campus.

Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce began holding classes in 1912. The school admitted its first female student in 1917, although the state legislature did not officially authorize attendance by women until 1920. Anna Teitelbaum Wise became the first female graduate in 1919 and went on to become Georgia Tech's first female faculty member the following year.

World War I caused several changes at the school. During the conflict and for some time afterwards, Georgia Tech hosted a school for cadet aviators, supply officers, and army technicians. Tech also started a Reserve Officer Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC ( or )) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

Overview

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all ...

unit; the first in the Southern United States, it became a permanent addition to the school. World War I affected the school academically as well: the United States government asked for and financed an automotive school for army officers, a rehabilitation program for disabled soldiers, and a geology department. Federal aid also helped to establish Tech's industrial education department, courtesy of the Smith–Hughes Act of 1917. The war also placed on hold extensive fundraising efforts for a new power plant, and made it difficult to find engineers willing to teach at the school; Matheson toured Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, and MIT in 1919 but failed to secure a single hire, as none of the students wished to work for such low wages.

The bitter rivalry between Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia flared up in 1919, when UGA mocked Tech's continuation of football during the United States' involvement in World War I. Because Tech was a military training ground, it had a complete assembly of male students. Many schools, such as UGA, lost all of their able-bodied male students to the war effort, forcing them to temporarily suspend football during the war. In fact, UGA did not play a game from 1917 to 1918.

When UGA renewed its program in 1919, their student body staged a parade which mocked Tech's continuation of football during times of war. The parade featured a

The bitter rivalry between Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia flared up in 1919, when UGA mocked Tech's continuation of football during the United States' involvement in World War I. Because Tech was a military training ground, it had a complete assembly of male students. Many schools, such as UGA, lost all of their able-bodied male students to the war effort, forcing them to temporarily suspend football during the war. In fact, UGA did not play a game from 1917 to 1918.

When UGA renewed its program in 1919, their student body staged a parade which mocked Tech's continuation of football during times of war. The parade featured a tank

A tank is an armoured fighting vehicle intended as a primary offensive weapon in front-line ground combat. Tank designs are a balance of heavy firepower, strong armour, and good battlefield mobility provided by tracks and a powerful ...

-shaped float marked " Argonne" with a sign "Georgia in France 1917" followed by an automobile with three people in Tech sweaters and caps bearing a sign "Tech in Atlanta". A printed program was subsequently distributed in the stands with a similar point. While the Tech faculty was able to prevent a riot, no apology was made, and this act led directly to Tech cutting athletic ties with UGA and canceling several of UGA's home football games at Grant Field (UGA commonly used Grant Field as its home field). Tech and UGA did not compete in athletics until the 1921 Southern Conference

The Southern Conference (SoCon) is a collegiate athletic conference affiliated with the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I. Southern Conference football teams compete in the Football Championship Subdivision (formerly k ...

basketball tournament. Despite intense pressure on Tech to make amends, Matheson stated that he would never change his mind unless "due apologies" were offered, and if he was overruled, he would resign. Regular season competition did not renew until after Matheson's retirement, in a 1925 agreement between the two institutions negotiated by athletic director

An athletic director (commonly "athletics director" or "AD") is an administrator at many American clubs or institutions, such as colleges and universities, as well as in larger high schools and middle schools, who oversees the work of coaches and ...

s J. B. Crenshaw and S. V. Sanford.

In 1916 Georgia Tech's football team, still coached by John Heisman, defeated Cumberland 222–0, the largest margin of victory in college football history. Cumberland's total net yardage was −28 and it had only one play for positive yards. Cumberland beat Georgia Tech's baseball team 22 to 0 the previous year, reportedly with the help of professional players Cumberland had hired as "ringers", an act which infuriated Heisman. Heisman amassed 104 wins over 16 seasons and led Tech to its first national title in 1917. After divorcing from his wife, Heisman moved to Pennsylvania in 1919, leaving Tech's Yellow Jackets in the hands of William Alexander.

In its first decades, Georgia Tech slowly grew from a trade school into a university. The state and federal governments provided little initiative for the school to grow significantly until 1919. That year, the Georgia General Assembly passed an act entitled "Establishing State Engineering Experiment Station at the Georgia School of Technology". This change coincided with federal debate about the establishment of Engineering Experiment Stations in a move similar to the

In its first decades, Georgia Tech slowly grew from a trade school into a university. The state and federal governments provided little initiative for the school to grow significantly until 1919. That year, the Georgia General Assembly passed an act entitled "Establishing State Engineering Experiment Station at the Georgia School of Technology". This change coincided with federal debate about the establishment of Engineering Experiment Stations in a move similar to the Hatch Act of 1887

The Hatch Act of 1887 (ch. 314, , enacted 1887-03-02, et seq.) gave federal funds, initially of $15,000 each, to state land-grant colleges in order to create a series of agricultural experiment stations, as well as pass along new information, es ...

's establishment of agricultural experiment station

An agricultural experiment station (AES) or agricultural research station (ARS) is a scientific research center that investigates difficulties and potential improvements to food production and agribusiness. Experiment station scientists work with ...

s; each Engineering Experiment Station would be a consultant

A consultant (from la, consultare "to deliberate") is a professional (also known as ''expert'', ''specialist'', see variations of meaning below) who provides advice and other purposeful activities in an area of specialization.

Consulting servi ...

group dedicated to assisting a region's industrial efforts. The EES at Georgia Tech was established with the goal of the "encouragement of industries and commerce" within the state. The coinciding federal effort failed, however, and the state did not finance Georgia Tech's EES, so the new organization existed only on paper.

The latter years of Matheson's presidency were troubled by a chronic shortage of funds. In 1919–1920, facilities designed for 700 students had to serve 1,365 students, and the school received the same $100,000 appropriation () that it had received since 1915, made worse by inflation which nearly halved its value in that time. Matheson was able to acquire a $25,000 increase from the General Assembly that year. In 1920–1921, though, an increase of $125,000 (to $250,000) was passed but subsequently tabled due to differences between the House and Senate version of the bill unrelated to Tech. To continue running the school, a frantic scramble for funds was undertaken, resulting in $40,000 from the General Education Board, $30,000 from a loan fund organized by the Georgia Rotary Club

Rotary International is one of the largest service organizations in the world. Its stated mission is to "provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through hefellowship of business, prof ...

, and a grant from the Atlanta City Council

The Atlanta City Council is the main municipal legislative body for the city of Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It consists of 16 members primarily elected from 12 districts within the city. The Atlanta City Government is divided into three bo ...

. The University of Georgia, in a similar financial condition, was forced to cut its faculty's salary. After this drama, the situation still did not improve: in 1922–1923, only $112,500 of the requested $250,000 had been appropriated, leading Matheson to reluctantly start charging in-state students for tuition. The rates were $100 for in-state students () and $175 for out-of-state students (). Georgia Tech still needed a $125,000 line of credit against its first professional fund-raising effort, the "Greater Georgia Tech Campaign".

As Matheson was leaving for the presidency of Drexel Institute

Drexel University is a private research university with its main campus in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Drexel's undergraduate school was founded in 1891 by Anthony J. Drexel, a financier and philanthropist. Founded as Drexel Institute of Ar ...

in late 1921, he wrote in ''The Atlanta Constitution'' that while Georgia Tech was "my first love" he found it a "humiliating burden" to get enough money from the state legislature to run and enlarge the school. The Board of Trustees offered him a substantial pay increase, but his issue was with the politics of the time, and not with his financial situation. In 1921, Matheson wrote:

Technological university (1922–1944)

On August 1, 1922, Marion L. Brittain was elected as the school's president. He noted in the 1923 annual report that "there are more students in Georgia Tech than in any other two colleges in Georgia, and we have the smallest appropriation of them all." He was able to convince the state of Georgia to increase the school's funding during his tenure. Additionally, a $300,000 grant () from the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics allowed Brittain to establish the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics. In 1930, Brittain's decision to use the money for a new school of aeronautics, headed by Montgomery Knight, was controversial; today, the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering boasts the second largest faculty in the United States behind MIT. Other accomplishments during Brittain's administration included a doubling of Georgia Tech's enrollment,

On August 1, 1922, Marion L. Brittain was elected as the school's president. He noted in the 1923 annual report that "there are more students in Georgia Tech than in any other two colleges in Georgia, and we have the smallest appropriation of them all." He was able to convince the state of Georgia to increase the school's funding during his tenure. Additionally, a $300,000 grant () from the Daniel Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics allowed Brittain to establish the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics. In 1930, Brittain's decision to use the money for a new school of aeronautics, headed by Montgomery Knight, was controversial; today, the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering boasts the second largest faculty in the United States behind MIT. Other accomplishments during Brittain's administration included a doubling of Georgia Tech's enrollment, accreditation

Accreditation is the independent, third-party evaluation of a conformity assessment body (such as certification body, inspection body or laboratory) against recognised standards, conveying formal demonstration of its impartiality and competence to ...

from the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools

The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) is an educational accreditor recognized by the United States Department of Education and the Council for Higher Education Accreditation. This agency accredits over 13,000 public and priv ...

, and the creation of a new ceramic engineering

Ceramic engineering is the science and technology of creating objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials. This is done either by the action of heat, or at lower temperatures using precipitation reactions from high-purity chemical solutions ...

department, building, and major that attracted the American Ceramics Society's national convention to Atlanta.

In 1929, some Georgia Tech faculty members belonging to Sigma Xi

Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society () is a highly prestigious, non-profit honor society for scientists and engineers. Sigma Xi was founded at Cornell University by a junior faculty member and a small group of graduate students in 1886 ...

started a research club that met once a month at Tech. One of the monthly subjects, proposed by ceramic engineering professor W. Harry Vaughan, was a collection of issues related to Tech, such as library development, and the development of a state engineering station. Such a station would theoretically assist local businesses with engineering problems via Georgia Tech's established faculty and resources. This group investigated the forty existing engineering experiments at universities around the country, and the report was compiled by Harold Bunger, Montgomery Knight, and Vaughan in December 1929.

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

threatened the already tentative nature of Georgia Tech's funding. In a speech on April 27, 1930, Brittain proposed that the university system be reorganized under a central body, rather than having each university under its own board. As a result, the Georgia General Assembly and Governor Richard Russell Jr.

Richard Brevard Russell Jr. (November 2, 1897 – January 21, 1971) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, he served as the 66th Governor of Georgia from 1931 to 1933 before serving in the United States Senate for almos ...

passed an act in 1931 that established the University System of Georgia (USG) and the corresponding Georgia Board of Regents; unfortunately for Brittain and Georgia Tech, the board was composed almost entirely of graduates of the University of Georgia. In its final act on January 7, 1932, the Tech Board of Trustees sent a letter to the chairman of the Georgia Board of Regents outlining its priorities for the school. The Depression also affected enrollment, which dropped from 3,271 in 1931–1932 to a low of 2,482 in 1933–1934, and only gradually increased afterwards. It also caused a decrease in funding from the State of Georgia, which in turn caused a decrease in faculty salaries, firing of graduate student assistants, and a postponing of building renovations.

As a cost-saving move, effective on July 1, 1934, the Georgia Board of Regents transferred control of the relatively large Evening School of Commerce to the University of Georgia and moved the small civil engineering program at UGA to Tech. The move was controversial, and both students and faculty protested against it, fearing that the Board of Regents would remove other programs from Georgia Tech and reduce it to an engineering department of the University of Georgia. Brittain suggested that the lack of Georgia Tech alumni on the Board of Regents contributed to their decision. Despite the pressure, the Board of Regents held its ground. The Depression also had a significant impact on the athletic program, as most athletes were in the commerce school, and resulted in the elimination of athletic scholarship

An athletic scholarship is a form of scholarship to attend a college or university or a private high school awarded to an individual based predominantly on his or her ability to play in a sport. Athletic scholarships are common in the United ...

s, which were replaced by a loan program. Plans for an industrial management

In economics, industrial organization is a field that builds on the theory of the firm by examining the structure of (and, therefore, the boundaries between) firms and markets. Industrial organization adds real-world complications to the perf ...

department to replace and supersede the Evening School of Commerce were first made in fall 1934. The department was established in 1935, and evolved into Tech's College of Management.

In 1933, S. V. Sanford, president of the University of Georgia, proposed that a "technical research activity" be established at Tech. Brittain and Dean William Vernon Skiles examined the Research Club's 1929 report, and moved to create such an organization. W. Harry Vaughan was selected as its acting director in April 1934, and $5,000 in funds were allocated directly from the Georgia Board of Regents. These funds went to the previously established Engineering Experiment Station (EES); its initial areas of focus were textiles, ceramics, and helicopter engineering. Georgia Tech's EES later became the Georgia Tech Research Institute

The Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) is the nonprofit applied research arm of the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. GTRI employs around 2,400 people, and is involved in approximately $600 millio ...

(GTRI).

The EES's early work was conducted in the basement of the Shop Building, and Vaughan's office was in the Aeronautical Engineering Building. By 1938, the EES was producing useful technology, and the station needed a method to conduct contract work outside of the state budget. Consequently, the Industrial Development Council (IDC) was formed. It was created by the Chancellor of the university system and the president of

The EES's early work was conducted in the basement of the Shop Building, and Vaughan's office was in the Aeronautical Engineering Building. By 1938, the EES was producing useful technology, and the station needed a method to conduct contract work outside of the state budget. Consequently, the Industrial Development Council (IDC) was formed. It was created by the Chancellor of the university system and the president of Georgia Power Company

Georgia Power is an electric utility headquartered in Atlanta, Georgia, United States. It was established as the Georgia Railway and Power Company and began operations in 1902 running streetcars in Atlanta as a successor to the Atlanta Consolidat ...

, and the EES's director was a member of the council. The IDC later became the Georgia Tech Research Corporation

The Georgia Tech Research Corporation (GTRC) is a contracting organization that supports research and technological development at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

History

The GTRC, then named the Industrial Development Council, was founded ...

, which currently serves as the sole contract organization for all Georgia Tech faculty and departments.

In 1939, EES director Vaughan became the director of the School of Ceramic Engineering. He was the director of the station until 1940, when he accepted a higher-paying job at the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolin ...

and was replaced by Harold Bunger (the first chairman of Georgia Tech's chemical engineering department). When the ceramics department was temporarily discontinued due to World War II, the current students found wartime employment. The department would be reincarnated after the war under the guidance of Lane Mitchell.

The Cocking affair occurred in 1941 and 1942 when Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge exerted direct control over the state's educational system, particularly through the firing of University of Georgia professor Walter Cocking, who had been hired to raise the relatively low academic standards at UGA's College of Education. Talmadge justified his actions by asserting that Cocking intended to integrate a part of the University of Georgia. Cocking's removal and the subsequent removal of members of the Georgia Board of Regents (including the vice chancellor) who disagreed with the decision were particularly controversial. Talmadge attempted to place Tech football star Red Barron in a new position as vice president of Georgia Tech; the move was widely criticized by Georgia Tech alumni, who marched on the capitol, and Barron subsequently declined to accept the position. In response to the actions of Governor Talmadge, the Southern Association of Independent Schools {{Cleanup-spam, date=April 2011

The Southern Association of Independent Schools (SAIS) is a U.S.-based voluntary organization of more than 380 independent elementary and secondary schools through the South, representing more than 220,000 students.

...

withdrew accreditation from all Georgia state-supported colleges for whites, including Georgia Tech. The controversy was instrumental in Talmadge's loss in the 1943 gubernatorial elections to Ellis Arnall

Ellis Gibbs Arnall (March 20, 1907December 13, 1992) was an American politician who served as the 69th Governor of Georgia from 1943 to 1947. A liberal Democrat, he helped lead efforts to abolish the poll tax and to reduce Georgia's voting age ...

.