History of Central Asia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Central Asia concerns the history of the various peoples that have inhabited Central Asia. The lifestyle of such people has been determined primarily by the area's climate and

The history of Central Asia concerns the history of the various peoples that have inhabited Central Asia. The lifestyle of such people has been determined primarily by the area's climate and

Anatomically modern humans (''

Anatomically modern humans ('' Paleolithic

Paleolithic

In the 2nd and 1st millennia BC, a series of large and powerful states developed on the southern periphery of Central Asia (the

In the 2nd and 1st millennia BC, a series of large and powerful states developed on the southern periphery of Central Asia (the

83–144

/ref> The vast fortified settlement of Kamenka on the

It was during the Sui and Tang dynasties that China expanded into eastern Central Asia. Chinese foreign policy to the north and west now had to deal with Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia. To handle and avoid any threats posed by the Turks, the Sui government repaired fortifications and received their trade and tribute missions. They sent royal princesses off to marry Turkic clan leaders, a total of four of them in 597, 599, 614, and 617. The Sui army intervened in Turks’ civil war and stirred conflict amongst ethnic groups against the Turks.

As early as the Sui dynasty, the Turks had become a major militarised force employed by the Chinese. When the Khitans began raiding north-east China in 605, a Chinese general led 20,000 Turks against them, distributing Khitan livestock and women to the Turks as a reward. On two occasions between 635 and 636, Tang royal princesses were married to Turk mercenaries or generals in Chinese service.

Throughout the Tang dynasty until the end of 755, there were approximately ten Turkic generals serving under the Tang. While most of the Tang army was made of '' fubing(府兵)'' Chinese conscripts, the majority of the troops led by Turkic generals were of non-Chinese origin, campaigning largely in the western frontier where the presence of '' fubing(府兵)'' troops was low. Some "Turkic" troops were nomadisized Han Chinese, a desinicized people.

Civil war in China was almost totally diminished by 626, along with the defeat in 628 of the Ordos Chinese warlord

It was during the Sui and Tang dynasties that China expanded into eastern Central Asia. Chinese foreign policy to the north and west now had to deal with Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia. To handle and avoid any threats posed by the Turks, the Sui government repaired fortifications and received their trade and tribute missions. They sent royal princesses off to marry Turkic clan leaders, a total of four of them in 597, 599, 614, and 617. The Sui army intervened in Turks’ civil war and stirred conflict amongst ethnic groups against the Turks.

As early as the Sui dynasty, the Turks had become a major militarised force employed by the Chinese. When the Khitans began raiding north-east China in 605, a Chinese general led 20,000 Turks against them, distributing Khitan livestock and women to the Turks as a reward. On two occasions between 635 and 636, Tang royal princesses were married to Turk mercenaries or generals in Chinese service.

Throughout the Tang dynasty until the end of 755, there were approximately ten Turkic generals serving under the Tang. While most of the Tang army was made of '' fubing(府兵)'' Chinese conscripts, the majority of the troops led by Turkic generals were of non-Chinese origin, campaigning largely in the western frontier where the presence of '' fubing(府兵)'' troops was low. Some "Turkic" troops were nomadisized Han Chinese, a desinicized people.

Civil war in China was almost totally diminished by 626, along with the defeat in 628 of the Ordos Chinese warlord  The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who invaded the Western Turks ruled by the qaghan Ashina Helu in 657 with an army led by

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who invaded the Western Turks ruled by the qaghan Ashina Helu in 657 with an army led by

The Tang Empire competed with the

The Tang Empire competed with the

Over time, as new technologies were introduced, the nomadic horsemen grew in power. The

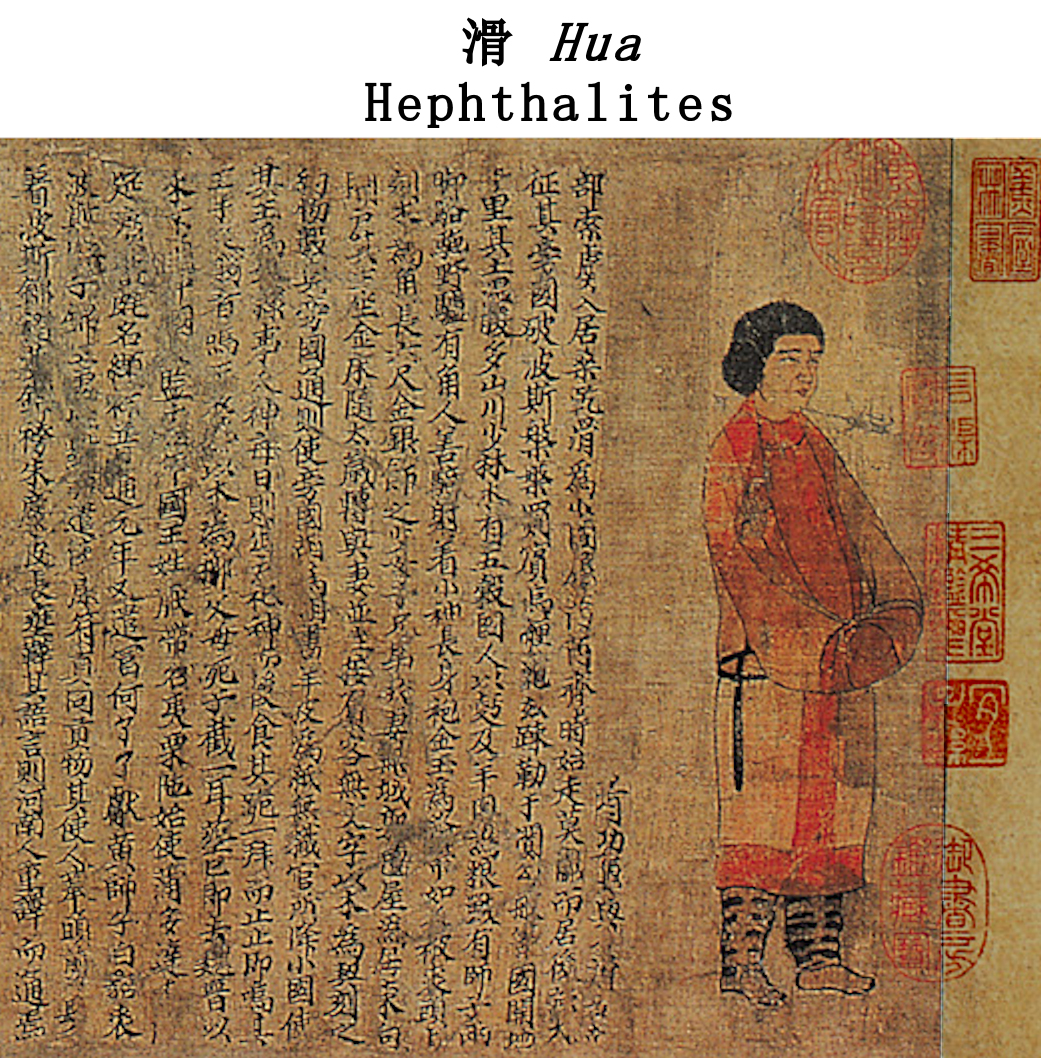

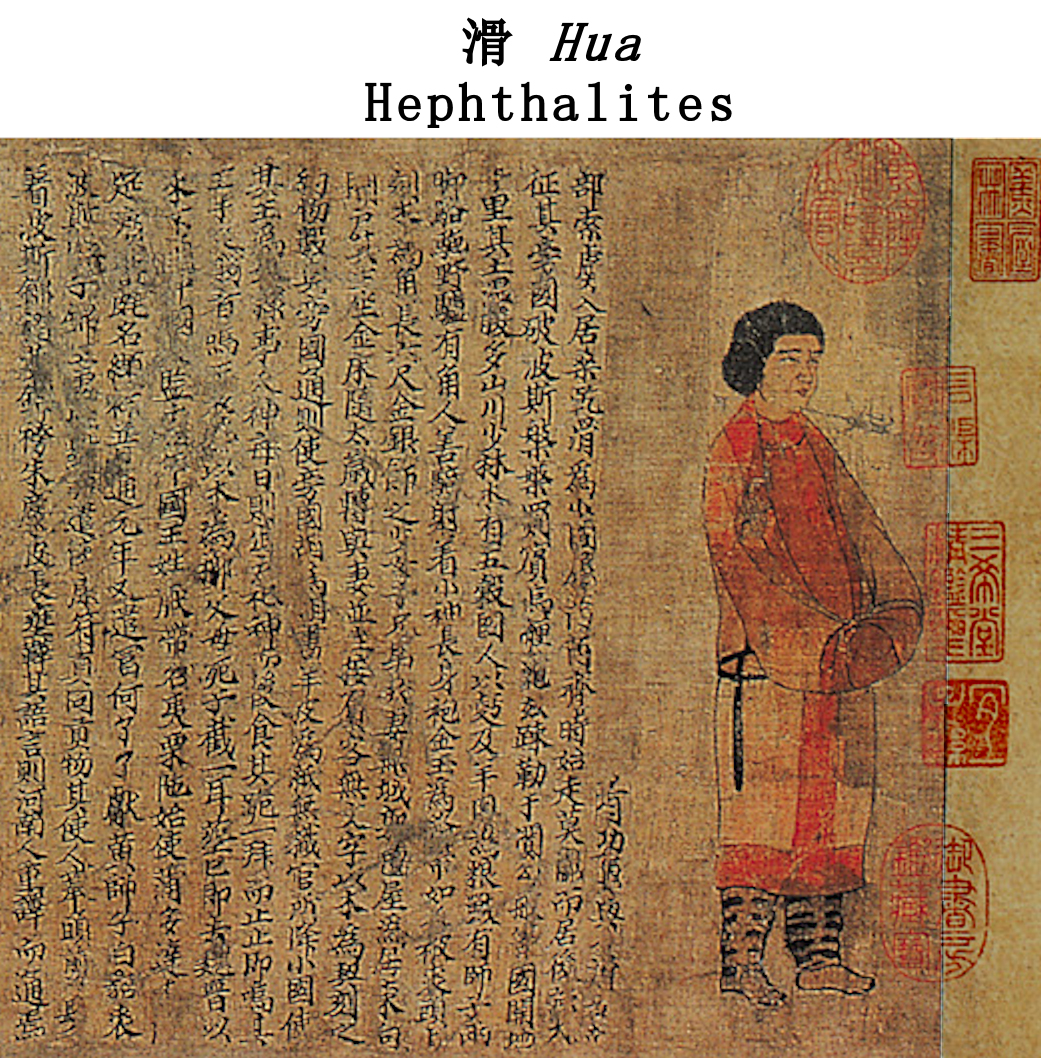

Over time, as new technologies were introduced, the nomadic horsemen grew in power. The  Once the foreign powers were expelled, several indigenous empires formed in Central Asia. The Hephthalites were the most powerful of these nomad groups in the 6th and 7th century and controlled much of the region. In the 10th and 11th centuries the region was divided between several powerful states including the Samanid dynasty, that of the Seljuk Turks, and the Khwarezmid Empire.

The most spectacular power to rise out of Central Asia developed when Genghis Khan united the tribes of Mongolia. Using superior military techniques, the Mongol Empire spread to comprise all of Central Asia and China as well as large parts of Russia, and the Middle East. After Genghis Khan died in 1227, most of Central Asia continued to be dominated by the Mongol successor Chagatai Khanate. This state proved to be short lived, as in 1369 Timur, a Turco-Mongol ruler, conquered most of the region.

Even harder than keeping a steppe empire together was governing conquered lands outside the region. While the steppe peoples of Central Asia found conquest of these areas easy, they found governing almost impossible. The diffuse political structure of the steppe confederacies was maladapted to the complex states of the settled peoples. Moreover, the armies of the nomads were based upon large numbers of horses, generally three or four for each warrior. Maintaining these forces required large stretches of grazing land, not present outside the steppe. Any extended time away from the homeland would thus cause the steppe armies to gradually disintegrate. To govern settled peoples the steppe peoples were forced to rely on the local bureaucracy, a factor that would lead to the rapid assimilation of the nomads into the culture of those they had conquered. Another important limit was that the armies, for the most part, were unable to penetrate the forested regions to the north; thus, such states as Republic of Novgorod, Novgorod and Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy began to grow in power.

In the 14th century much of Central Asia, and many areas beyond it, were conquered by Timur (1336–1405) who is known in the west as Tamerlane. It was during Timur's reign that the nomadic steppe culture of Central Asia fused with the settled culture of Iran. One of its consequences was an entirely new visual language that glorified Timur and subsequent Timurid rulers. This visual language was also used to articulate their commitment to Islam. Timur's large empire collapsed soon after his death, however. The region then became divided among a series of smaller Khanates, including the Khanate of Khiva, the Khanate of Bukhara, the Khanate of Kokand, and the Khanate of Kashgar.

Once the foreign powers were expelled, several indigenous empires formed in Central Asia. The Hephthalites were the most powerful of these nomad groups in the 6th and 7th century and controlled much of the region. In the 10th and 11th centuries the region was divided between several powerful states including the Samanid dynasty, that of the Seljuk Turks, and the Khwarezmid Empire.

The most spectacular power to rise out of Central Asia developed when Genghis Khan united the tribes of Mongolia. Using superior military techniques, the Mongol Empire spread to comprise all of Central Asia and China as well as large parts of Russia, and the Middle East. After Genghis Khan died in 1227, most of Central Asia continued to be dominated by the Mongol successor Chagatai Khanate. This state proved to be short lived, as in 1369 Timur, a Turco-Mongol ruler, conquered most of the region.

Even harder than keeping a steppe empire together was governing conquered lands outside the region. While the steppe peoples of Central Asia found conquest of these areas easy, they found governing almost impossible. The diffuse political structure of the steppe confederacies was maladapted to the complex states of the settled peoples. Moreover, the armies of the nomads were based upon large numbers of horses, generally three or four for each warrior. Maintaining these forces required large stretches of grazing land, not present outside the steppe. Any extended time away from the homeland would thus cause the steppe armies to gradually disintegrate. To govern settled peoples the steppe peoples were forced to rely on the local bureaucracy, a factor that would lead to the rapid assimilation of the nomads into the culture of those they had conquered. Another important limit was that the armies, for the most part, were unable to penetrate the forested regions to the north; thus, such states as Republic of Novgorod, Novgorod and Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy began to grow in power.

In the 14th century much of Central Asia, and many areas beyond it, were conquered by Timur (1336–1405) who is known in the west as Tamerlane. It was during Timur's reign that the nomadic steppe culture of Central Asia fused with the settled culture of Iran. One of its consequences was an entirely new visual language that glorified Timur and subsequent Timurid rulers. This visual language was also used to articulate their commitment to Islam. Timur's large empire collapsed soon after his death, however. The region then became divided among a series of smaller Khanates, including the Khanate of Khiva, the Khanate of Bukhara, the Khanate of Kokand, and the Khanate of Kashgar.

An even more important development was the introduction of gunpowder-based weapons. The gunpowder revolution allowed settled peoples to defeat the steppe horsemen in open battle for the first time. Construction of these weapons required the infrastructure and economies of large societies and were thus impractical for nomadic peoples to produce. The domain of the nomads began to shrink as, beginning in the 15th century, the settled powers gradually began to conquer Central Asia.

The last steppe empire to emerge was that of the Dzungars who conquered much of East Turkestan and Mongolia. However, in a sign of the changed times they proved unable to match the Chinese and were decisively defeated by the forces of the

An even more important development was the introduction of gunpowder-based weapons. The gunpowder revolution allowed settled peoples to defeat the steppe horsemen in open battle for the first time. Construction of these weapons required the infrastructure and economies of large societies and were thus impractical for nomadic peoples to produce. The domain of the nomads began to shrink as, beginning in the 15th century, the settled powers gradually began to conquer Central Asia.

The last steppe empire to emerge was that of the Dzungars who conquered much of East Turkestan and Mongolia. However, in a sign of the changed times they proved unable to match the Chinese and were decisively defeated by the forces of the

The Russians also expanded south, first with the transformation of the Ukraine, Ukrainian steppe into an agricultural heartland, and subsequently onto the fringe of the Kazakh steppes, beginning with the foundation of the fortress of Orenburg. The slow Russian conquest of the heart of Central Asia began in the early 19th century, although Peter I of Russia, Peter the Great had sent a failed expedition under Prince Bekovitch-Cherkassky against Khiva as early as the 1720s.

By the 1800s, the locals could do little to resist the Russian advance, although the Kazakhs of the Great Horde under Kenesary Kasimov rose in rebellion from 1837 to 1846. Until the 1870s, for the most part, Russian interference was minimal, leaving native ways of life intact and local government structures in place. With the conquest of Turkestan after 1865 and the consequent securing of the frontier, the Russians gradually expropriated large parts of the steppe and gave these lands to Russian farmers, who began to arrive in large numbers. This process was initially limited to the northern fringes of the steppe and it was only in the 1890s that significant numbers of Russians began to settle farther south, especially in Zhetysu (Semirechye).

The Russians also expanded south, first with the transformation of the Ukraine, Ukrainian steppe into an agricultural heartland, and subsequently onto the fringe of the Kazakh steppes, beginning with the foundation of the fortress of Orenburg. The slow Russian conquest of the heart of Central Asia began in the early 19th century, although Peter I of Russia, Peter the Great had sent a failed expedition under Prince Bekovitch-Cherkassky against Khiva as early as the 1720s.

By the 1800s, the locals could do little to resist the Russian advance, although the Kazakhs of the Great Horde under Kenesary Kasimov rose in rebellion from 1837 to 1846. Until the 1870s, for the most part, Russian interference was minimal, leaving native ways of life intact and local government structures in place. With the conquest of Turkestan after 1865 and the consequent securing of the frontier, the Russians gradually expropriated large parts of the steppe and gave these lands to Russian farmers, who began to arrive in large numbers. This process was initially limited to the northern fringes of the steppe and it was only in the 1890s that significant numbers of Russians began to settle farther south, especially in Zhetysu (Semirechye).

The forces of the khanates were poorly equipped and could do little to resist Russia's advances, although the Kokandian commander Alimqul led a Quixotism, quixotic campaign before being killed outside Chimkent. The main opposition to Russian expansion into Turkestan came from the United Kingdom, British, who felt that Russia was growing too powerful and threatening the northwest frontiers of British India. This rivalry came to be known as The Great Game, where both powers competed to advance their own interests in the region. It did little to slow the pace of conquest north of the Oxus, but did ensure that

The forces of the khanates were poorly equipped and could do little to resist Russia's advances, although the Kokandian commander Alimqul led a Quixotism, quixotic campaign before being killed outside Chimkent. The main opposition to Russian expansion into Turkestan came from the United Kingdom, British, who felt that Russia was growing too powerful and threatening the northwest frontiers of British India. This rivalry came to be known as The Great Game, where both powers competed to advance their own interests in the region. It did little to slow the pace of conquest north of the Oxus, but did ensure that

China’s Belt and Road Initiative through the Lens of Central Asia

��, in Fanny M. Cheung and Ying-yi Hong (eds) ''Regional Connection under the Belt and Road Initiative. The Prospects for Economic and Financial Cooperation''. London: Routledge, p. 116.

UNESCO History of Civilizations of Central Asia

' (Paris: UNESCO) 1992– *Hildinger, Erik. ''Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia, 500 BC. to 1700 AD.'' (Cambridge: Da Capo) 2001. *Guzel Maitdinova, Maitdinova, Guzel. The Dialogue of Civilizations in the Central Asian area of the Silk Road, Great Silk Route: Historical experience of integration and reference points of XXI century. Dushanbe: 2015. *Guzel Maitdinova, Maitdinova, Guzel. The Kirpand State – an Empire in Middle Asia. Dushanbe: 2011. *O'Brien, Patrick K. (General Editor). ''Oxford Atlas of World History.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. *Olcott, Martha Brill. ''Central Asia's New States: Independence, Foreign policy, and Regional security.'' (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press) 1996. *Sinor, Denis ''The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia'' (Cambridge) 1990 (2nd Edition). *S. Frederick Starr,

Rediscovering Central Asia

'

Encyclopædia Iranica: Central Asia in pre-Islamic Times (R. Fryer)

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20090224083111/http://www.iranica.com/newsite/search/searchpdf.isc?ReqStrPDFPath=%2Fhome%2Firanica%2Fpublic_html%2Fnewsite%2Fpdfarticles%2Fv5_articles%2Fcentral_asia%2Fmongol_and_timurid_periods&OptStrLogFile=%2Fhome%2Firanica%2Fpublic_html%2Fnewsite%2Flogs%2Fpdfdownload.html Encyclopædia Iranica: Central Asia in the Mongol and Timurid Periods (B. Spuler)]

Encyclopædia Iranica: Central Asia from the 16th to the 18th centuries (R.D. McChesney)

(Yuri Bregel)

Center for the Study of Eurasian Nomads

perseus project

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

New Directions Post-Independence

from th

Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

{{Authority control History of Central Asia, Archaeology of Central Asia Prehistoric Asia Geography of Central Asia

The history of Central Asia concerns the history of the various peoples that have inhabited Central Asia. The lifestyle of such people has been determined primarily by the area's climate and

The history of Central Asia concerns the history of the various peoples that have inhabited Central Asia. The lifestyle of such people has been determined primarily by the area's climate and geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

. The arid

A region is arid when it severely lacks available water, to the extent of hindering or preventing the growth and development of plant and animal life. Regions with arid climates tend to lack vegetation and are called xeric or desertic. Most ...

ity of the region makes agriculture difficult and distance from the sea cut it off from much trade. Thus, few major cities developed in the region. Nomad

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

ic horse peoples of the steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate gras ...

dominated the area for millennia.

Relations between the steppe nomads and the settled people in and around Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

were marked by conflict. The nomadic lifestyle was well suited to warfare, and the steppe horse riders became some of the most militarily potent people in the world, due to the devastating techniques and ability of their horse archers. Periodically, tribal leaders or changing conditions would cause several tribes to organize themselves into a single military force, which would then often launch campaigns of conquest, especially into more 'civilized' areas. A few of these types of tribal coalitions included the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

' invasion of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, various Turkic migrations into Transoxiana

Transoxiana or Transoxania (Land beyond the Oxus) is the Latin name for a region and civilization located in lower Central Asia roughly corresponding to modern-day eastern Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, parts of southern Kazakhstan, parts of Tu ...

, the Wu Hu attacks on China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and most notably the Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

conquest of much of Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

.

The dominance of the nomads ended in the 16th century as firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

s allowed settled people to gain control of the region. The Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War ...

, the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

, and other powers expanded into the area and seized the bulk of Central Asia by the end of the 19th century. After the Russian Revolution of 1917

The Russian Revolution was a period of political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and adopt a socialist form of government ...

, the Soviet Union incorporated most of Central Asia; only Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

and Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

remained nominally independent, although Mongolia existed as a Soviet satellite state and Soviet troops invaded Afghanistan in the late 20th century. The Soviet areas of Central Asia saw much industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and construction of infrastructure, but also the suppression of local cultures and a lasting legacy of ethnic tensions and environmental problems.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, five Central Asian countries gained independence — Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a transcontinental country located mainly in Central Asia and partly in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the north and west, China to the east, Kyrgyzstan to the southeast, Uzbeki ...

, Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked co ...

, Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan ( or ; tk, Türkmenistan / Түркменистан, ) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the s ...

, Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan,, pronounced or the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Kyrgyzstan is bordered by Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the south, and the People's Republic of China to the ea ...

, and Tajikistan

Tajikistan (, ; tg, Тоҷикистон, Tojikiston; russian: Таджикистан, Tadzhikistan), officially the Republic of Tajikistan ( tg, Ҷумҳурии Тоҷикистон, Jumhurii Tojikiston), is a landlocked country in Centr ...

. In all of the new states, former Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of '' The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engel ...

officials retained power as local strongmen, with the partial exception of Kyrgyzstan which, despite ousting three post-Soviet presidents in popular uprisings, has as yet been unable to consolidate a stable democracy.

Prehistory

Anatomically modern humans (''

Anatomically modern humans (''Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture ...

'') reached Central Asia by 50,000 to 40,000 years ago. The Tibetan Plateau

The Tibetan Plateau (, also known as the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau or the Qing–Zang Plateau () or as the Himalayan Plateau in India, is a vast elevated plateau located at the intersection of Central, South and East Asia covering most of the Ti ...

is thought to have been reached by 38,000 years ago. The currently oldest modern human sample found in northern Central Asia, is a 45,000-year-old remain, which was genetically closest to ancient and modern East Asians, but his lineage died out quite early.

Paleolithic

Paleolithic Central Asia

Central Asia, also known as Middle Asia, is a region of Asia that stretches from the Caspian Sea in the west to western China and Mongolia in the east, and from Afghanistan and Iran in the south to Russia in the north. It includes the fo ...

was characterized by an distinctive but deeply European-related population ( Ancient North Eurasian), with subsequent geneflow from Paleo-Siberians, contributing East Asian-related ancestry towards Paleolithic Central Asians. During the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, ancient Central Asia received various migration events from Europe and the Middle East, associated with Indo-Europeans. Bronze Age Central Asia consisted largely of Iranian peoples

The Iranian peoples or Iranic peoples are a diverse grouping of Indo-European peoples who are identified by their usage of the Iranian languages and other cultural similarities.

The Proto-Iranians are believed to have emerged as a separate ...

, with some groups being of Paleo-Siberian and Samoyedic (Uralic) origin. Since the early Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age ( Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age ( Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly ...

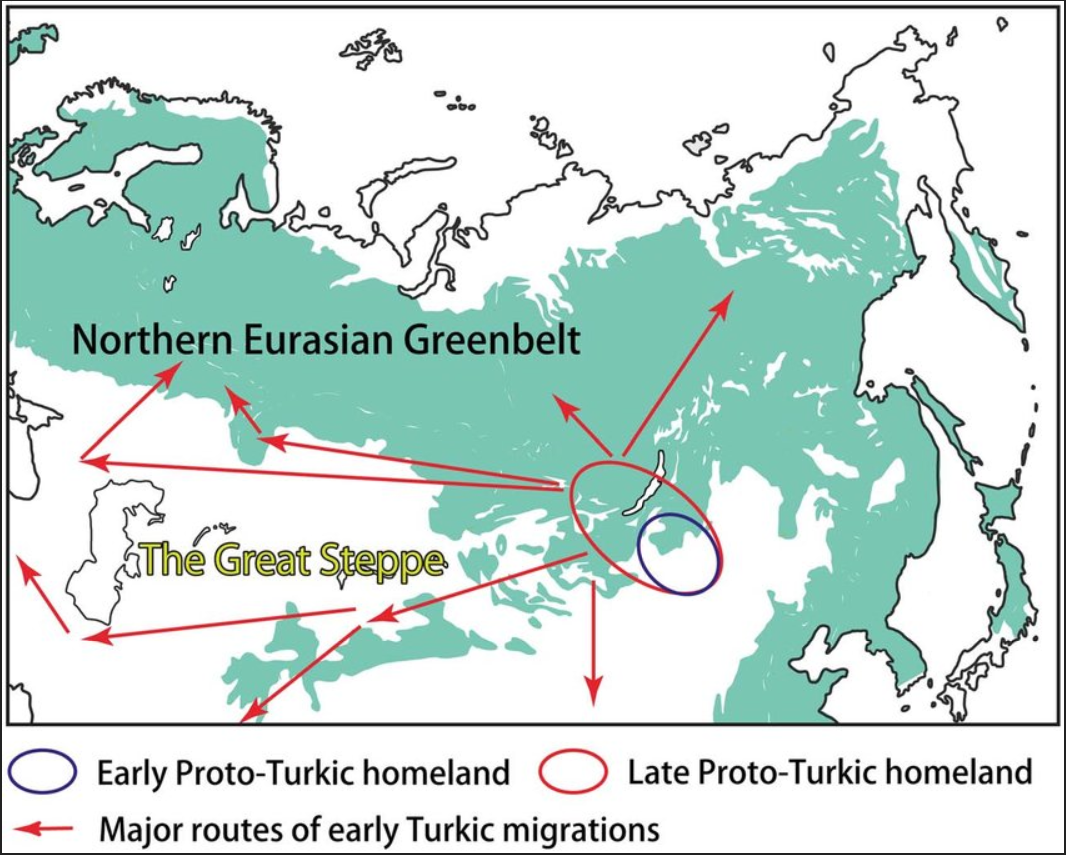

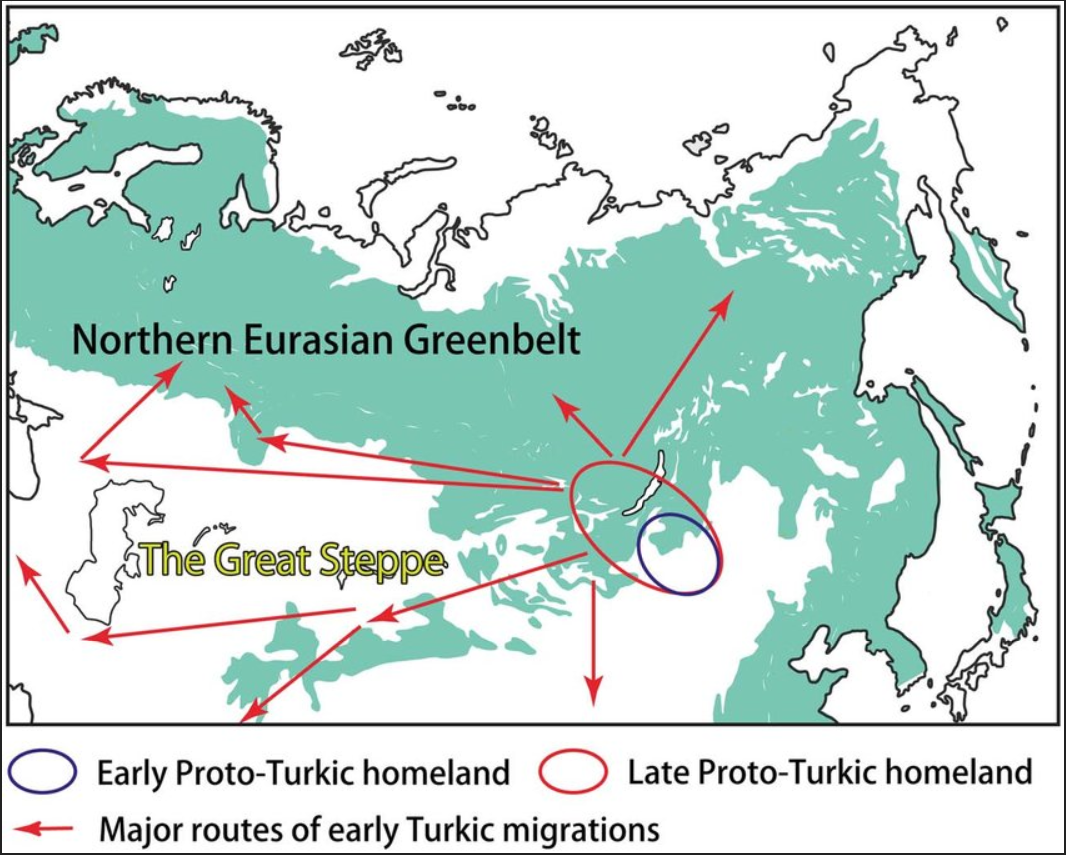

, Central Asia received noteworthy amounts of migration from East Asian-related populations, and became increasingly diverse. The Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging to ...

slowly replaced and assimilated the previous Iranian-speaking locals, turning the population of Central Asia from largely Iranian, into primarily of East Asian descent. Modern Central Asians are characterized by both West-Eurasian and East-Eurasian ancestry, with the majority being of primarily East Asian ancestry, and can be linked to expanding Turkic peoples

The Turkic peoples are a collection of diverse ethnic groups of West, Central, East, and North Asia as well as parts of Europe, who speak Turkic languages.. "Turkic peoples, any of various peoples whose members speak languages belonging to ...

outgoing from Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

and Northeast Asia

Northeast Asia or Northeastern Asia is a geographical subregion of Asia; its northeastern landmass and islands are bounded by the Pacific Ocean.

The term Northeast Asia was popularized during the 1930s by American historian and political scient ...

.

The term Ceramic Mesolithic

The Mesolithic ( Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymou ...

is used of late Mesolithic cultures of Central Asia, during the 6th to 5th millennia BC

(in Russian archaeology, these cultures are described as Neolithic even though farming is absent). It is characterized by its distinctive type of pottery, with point or knob base and flared rims, manufactured by methods not used by the Neolithic farmers. The earliest manifestation of this type of pottery may be in the region around Lake Baikal in Siberia. It appears in the Elshan or Yelshanka or Samara culture on the Volga in Russia by about 7000 BC. and from there spread via the Dnieper-Donets culture to the Narva culture

Narva culture or eastern Baltic was a European Neolithic archaeological culture found in present-day Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Kaliningrad Oblast (former East Prussia), and adjacent portions of Poland, Belarus and Russia. A successor of ...

of the Eastern Baltic.

The Botai culture

The Botai culture is an archaeological culture (c. 3700–3100 BC) of prehistoric northern Central Asia. It was named after the settlement of Botai in today's northern Kazakhstan. The Botai culture has two other large sites: Krasnyi ...

(c. 3700–3100 BC) is suggested to be the earliest culture to have domesticated the horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

. The four analyzed Botai samples had about 2/3 European-related and 1/3 East Asian-related ancestry. The Botai samples also showed high affinity towards the Mal'ta boy sample in Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

.

In the Pontic–Caspian steppe

The Pontic–Caspian steppe, formed by the Caspian steppe and the Pontic steppe, is the steppeland stretching from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the Pontus Euxinus of antiquity) to the northern area around the Caspian Sea. It extend ...

, Chalcolithic

The Copper Age, also called the Chalcolithic (; from grc-gre, χαλκός ''khalkós'', "copper" and ''líthos'', "Rock (geology), stone") or (A)eneolithic (from Latin ''wikt:aeneus, aeneus'' "of copper"), is an list of archaeologi ...

cultures develop in the second half of the 5th millennium BC, small communities in permanent settlements which began to engage in agricultural practices as well as herding. Around this time, some of these communities began the domestication of the horse

A number of hypotheses exist on many of the key issues regarding the domestication of the horse. Although horses appeared in Paleolithic cave art as early as 30,000 BCE, these were wild horses and were probably hunted for meat.

How and when ho ...

. According to the Kurgan hypothesis

The Kurgan hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory, Kurgan model, or steppe theory) is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages spread out throughout Europe and pa ...

, the north-west of the region is also considered to be the source of the root of the Indo-European languages

The Indo-European languages are a language family native to the overwhelming majority of Europe, the Iranian plateau, and the northern Indian subcontinent. Some European languages of this family, English, French, Portuguese, Russian, D ...

.

The horse-drawn chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&n ...

appears in the 3rd millennium BC, by 2000 BC, in the form of war chariots with spoked wheels, thus being made more maneuverable, and dominated the battlefields. The growing use of the horse, combined with the failure, roughly around 2000 BC, of the always precarious irrigation systems that had allowed for extensive agriculture in the region, gave rise and dominance of pastoral nomadism by 1000 BC, a way of life that would dominate the region for the next several millennia, giving rise to the Scythia

Scythia ( Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

...

n expansion of the Iron Age.

Scattered nomadic groups maintained herds of sheep, goats, horses, and camels, and conducted annual migrations to find new pastures (a practice known as transhumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and lower val ...

). The people lived in yurt

A yurt (from the Turkic languages) or ger ( Mongolian) is a portable, round tent covered and insulated with skins or felt and traditionally used as a dwelling by several distinct nomadic groups in the steppes and mountains of Central Asia ...

s (or gers) – tents made of hides and wood that could be disassembled and transported. Each group had several yurts, each accommodating about five people.

While the semi-arid plains were dominated by the nomads, small city-states and sedentary agrarian societies arose in the more humid areas of Central Asia. The Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex of the early 2nd millennium BC was the first sedentary civilization of the region, practicing irrigation farming of wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

and barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley p ...

and possibly a form of writing. Bactria-Margiana probably interacted with the contemporary Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

nomads of the Andronovo culture

The Andronovo culture (russian: Андроновская культура, translit=Andronovskaya kul'tura) is a collection of similar local Late Bronze Age cultures that flourished 2000–1450 BC,Grigoriev, Stanislav, (2021)"Andronovo ...

, the originators of the spoke-wheeled chariot

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&n ...

, who lived to their north in western Siberia, Russia, and parts of Kazakhstan, and survived as a culture until the 1st millennium BC. These cultures, particularly Bactria-Margiana, have been posited as possible representatives of the hypothetical Aryan

Aryan or Arya (, Indo-Iranian *''arya'') is a term originally used as an ethnocultural self-designation by Indo-Iranians in ancient times, in contrast to the nearby outsiders known as 'non-Aryan' (*''an-arya''). In Ancient India, the term ...

culture ancestral to the speakers of the Indo-Iranian languages

The Indo-Iranian languages (also Indo-Iranic languages or Aryan languages) constitute the largest and southeasternmost extant branch of the Indo-European language family (with over 400 languages), predominantly spoken in the geographical subr ...

(see Indo-Iranians

Indo-Iranian peoples, also known as Indo-Iranic peoples by scholars, and sometimes as Arya or Aryans from their self-designation, were a group of Indo-European peoples who brought the Indo-Iranian languages, a major branch of the Indo-European l ...

).

Later the strongest of Sogdian city-states of the Fergana Valley rose to prominence. After the 1st century BC, these cities became home to the traders of the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

and grew wealthy from this trade. The steppe nomads were dependent on these settled people for a wide array of goods that were impossible for transient populations to produce. The nomads traded for these when they could, but because they generally did not produce goods of interest to sedentary people, the popular alternative was to carry out raids.

A wide variety of people came to populate the steppes. Nomadic groups in Central Asia included the Huns and other Turks, as well as Indo-Europeans such as the Tocharians

The Tocharians, or Tokharians ( US: or ; UK: ), were speakers of Tocharian languages, Indo-European languages known from around 7600 documents from around 400 to 1200 AD, found on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (modern Xinjiang, China). ...

, Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian. ...

, Scythia

Scythia ( Scythian: ; Old Persian: ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) or Scythica (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ), also known as Pontic Scythia, was a kingdom created by the Scythians during the 6th to 3rd centuries BC in the Pontic–Caspian steppe.

...

ns, Saka

The Saka ( Old Persian: ; Kharoṣṭhī: ; Ancient Egyptian: , ; , old , mod. , ), Shaka (Sanskrit ( Brāhmī): , , ; Sanskrit (Devanāgarī): , ), or Sacae (Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were a group of nomadic Iranian peoples who histo ...

, Yuezhi

The Yuezhi (;) were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat ...

, Wusun, and others, and a number of Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

groups. Despite these ethnic and linguistic differences, the steppe lifestyle led to the adoption of very similar culture across the region.

Ancient era

In the 2nd and 1st millennia BC, a series of large and powerful states developed on the southern periphery of Central Asia (the

In the 2nd and 1st millennia BC, a series of large and powerful states developed on the southern periphery of Central Asia (the Ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

). These empires launched several attempts to conquer the steppe people but met with only mixed success. The Median Empire

The Medes ( Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, ...

and Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

both ruled parts of Central Asia. The Xiongnu

The Xiongnu (, ) were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 20 ...

Empire (209 BC-93 (156) AD) may be seen as the first central Asian empire which set an example for later Göktürk and Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

empires.Christoph Baumer "The History of Central Asia – The Age of the Silk Roads (Volume 2); PART I: EARLY EMPIRES AND KINGDOMS IN EAST CENTRAL ASIA 1. The Xiongnu, the First Steppe Nomad Empire" Xiongnu's ancestor Xianyu tribe founded Zhongshan state (c. 6th century BC – c. 296 BC) in Hebei

Hebei or , (; alternately Hopeh) is a northern province of China. Hebei is China's sixth most populous province, with over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. The province is 96% Han Chinese, 3% Manchu, 0.8% Hui, and ...

province, China. The title chanyu

Chanyu () or Shanyu (), short for Chengli Gutu Chanyu (), was the title used by the supreme rulers of Inner Asian nomads for eight centuries until superseded by the title "'' Khagan''" in 402 CE. The title was most famously used by the rulin ...

was used by the Xiongnu rulers before Modun Chanyu so it is possible that statehood

A state is a centralized political organization that imposes and enforces rules over a population within a territory. There is no undisputed definition of a state. One widely used definition comes from the German sociologist Max Weber: a "st ...

history of the Xiongnu began long before Modun's rule.

Following the success of the Han–Xiongnu War, Chinese states would also regularly strive to extend their power westwards. Despite their military might, these states found it difficult to conquer the whole region.

When faced by a stronger force, the nomads could simply retreat deep into the steppe and wait for the invaders to leave. With no cities and little wealth other than the herds they took with them, the nomads had nothing they could be forced to defend. An example of this is given by Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria (Italy). He is known fo ...

's detailed account of the futile Persian campaigns against the Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

. The Scythians, like most nomad empires, had permanent settlements of various sizes, representing various degrees of civilisation.Herodotus, IV83–144

/ref> The vast fortified settlement of Kamenka on the

Dnieper

}

The Dnieper () or Dnipro (); , ; . is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. It is the longest river of Ukraine an ...

River, settled since the end of the 5th century BC, became the centre of the Scythian kingdom ruled by Ateas, who lost his life in a battle against Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon ( grc-gre, Φίλιππος ; 382 – 21 October 336 BC) was the king ('' basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

in 339 BC.

Some empires, such as the Persian and Macedon

Macedonia (; grc-gre, Μακεδονία), also called Macedon (), was an ancient kingdom on the periphery of Archaic and Classical Greece, and later the dominant state of Hellenistic Greece. The kingdom was founded and initially ruled ...

ian empires, did make deep inroads into Central Asia by founding cities and gaining control of the trading centres. Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

's conquests spread Hellenistic civilisation

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

all the way to Alexandria Eschate

Alexandria Eschate ( grc-x-attic, Ἀλεξάνδρεια Ἐσχάτη, grc-x-doric, Αλεχάνδρεια Ἐσχάτα, Alexandria Eschata, "Furthest Alexandria") was a city founded by Alexander the Great, at the south-western end of the Fe ...

(Lit. “Alexandria the Furthest”), established in 329 BC in modern Tajikistan. After Alexander's death in 323 BC, his Central Asian territory fell to the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

during the Wars of the Diadochi

The Wars of the Diadochi ( grc, Πόλεμοι τῶν Διαδόχων, '), or Wars of Alexander's Successors, were a series of conflicts that were fought between the generals of Alexander the Great, known as the Diadochi, over who would rule ...

.

In 250 BC, the Central Asian portion of the empire (Bactria

Bactria (; Bactrian: , ), or Bactriana, was an ancient region in Central Asia in Amu Darya's middle stream, stretching north of the Hindu Kush, west of the Pamirs and south of the Gissar range, covering the northern part of Afghanistan, sou ...

) seceded as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

The Bactrian Kingdom, known to historians as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom or simply Greco-Bactria, was a Hellenistic-era Greek state, and along with the Indo-Greek Kingdom, the easternmost part of the Hellenistic world in Central Asia and the Ind ...

, which had extensive contacts with India and China until its end in 125 BC. The Indo-Greek Kingdom, mostly based in the Punjab region

Punjab (; Punjabi: پنجاب ; ਪੰਜਾਬ ; ; also romanised as ''Panjāb'' or ''Panj-Āb'') is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia, specifically in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising a ...

but controlling a fair part of Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is borde ...

, pioneered the development of Greco-Buddhism. The Kushan Kingdom thrived across a wide swath of the region from the 2nd century BC to the 4th century AD, and continued Hellenistic and Buddhist traditions. These states prospered from their position on the Silk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

linking China and Europe.

Likewise, in eastern Central Asia, the Chinese Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

expanded into the region at the height of its imperial power. From roughly 115 to 60 BC, Han forces fought the Xiongnu over control of the oasis city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

s in the Tarim Basin. The Han was eventually victorious and established the Protectorate of the Western Regions in 60 BC, which dealt with the region's defence and foreign affairs. Chinese rule in Tarim Basin was replaced successively with Kushans and Hephthalites

The Hephthalites ( xbc, ηβοδαλο, translit= Ebodalo), sometimes called the White Huns (also known as the White Hunas, in Iranian as the ''Spet Xyon'' and in Sanskrit as the ''Sveta-huna''), were a people who lived in Central Asia during th ...

.

Later, external powers such as the Sassanid Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the History of Iran, last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th cen ...

would come to dominate this trade. One of those powers, the Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conqu ...

, was of Central Asian origin, but adopted Persian-Greek cultural traditions. This is an early example of a recurring theme of Central Asian history: occasionally nomads of Central Asian origin would conquer the kingdoms and empires surrounding the region, but quickly merge into the culture of the conquered peoples.

At this time Central Asia was a heterogeneous region with a mixture of cultures and religions. Buddhism remained the largest religion, but was concentrated in the east. Around Persia, Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheisti ...

became important. Nestorian Christianity entered the area, but was never more than a minority faith. More successful was Manichaeism

Manichaeism (;

in New Persian ; ) is a former major religionR. van den Broek, Wouter J. Hanegraaff ''Gnosis and Hermeticism from Antiquity to Modern Times''SUNY Press, 1998 p. 37 founded in the 3rd century AD by the Parthian prophet Mani (A ...

, which became the third largest faith.

Turkic expansion began in the 6th century; the Turkic speaking Uyghurs

The Uyghurs; ; ; ; zh, s=, t=, p=Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: ( ), alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central Asia, Cent ...

were one of many distinct cultural groups brought together by the trade of the Silk Route at Turfan

Turpan (also known as Turfan or Tulufan, , ug, تۇرپان) is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of and a population of 632,000 (2015).

Geonyms

The original name of the cit ...

, which was then ruled by China's Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

. The Uyghurs, primarily pastoral nomads, observed a number of religions including Manichaeism, Buddhism, and Nestorian Christianity. Many of the artefacts from this period were found in the 19th century in this remote desert region.

Medieval

Sui and early Tang dynasty

It was during the Sui and Tang dynasties that China expanded into eastern Central Asia. Chinese foreign policy to the north and west now had to deal with Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia. To handle and avoid any threats posed by the Turks, the Sui government repaired fortifications and received their trade and tribute missions. They sent royal princesses off to marry Turkic clan leaders, a total of four of them in 597, 599, 614, and 617. The Sui army intervened in Turks’ civil war and stirred conflict amongst ethnic groups against the Turks.

As early as the Sui dynasty, the Turks had become a major militarised force employed by the Chinese. When the Khitans began raiding north-east China in 605, a Chinese general led 20,000 Turks against them, distributing Khitan livestock and women to the Turks as a reward. On two occasions between 635 and 636, Tang royal princesses were married to Turk mercenaries or generals in Chinese service.

Throughout the Tang dynasty until the end of 755, there were approximately ten Turkic generals serving under the Tang. While most of the Tang army was made of '' fubing(府兵)'' Chinese conscripts, the majority of the troops led by Turkic generals were of non-Chinese origin, campaigning largely in the western frontier where the presence of '' fubing(府兵)'' troops was low. Some "Turkic" troops were nomadisized Han Chinese, a desinicized people.

Civil war in China was almost totally diminished by 626, along with the defeat in 628 of the Ordos Chinese warlord

It was during the Sui and Tang dynasties that China expanded into eastern Central Asia. Chinese foreign policy to the north and west now had to deal with Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia. To handle and avoid any threats posed by the Turks, the Sui government repaired fortifications and received their trade and tribute missions. They sent royal princesses off to marry Turkic clan leaders, a total of four of them in 597, 599, 614, and 617. The Sui army intervened in Turks’ civil war and stirred conflict amongst ethnic groups against the Turks.

As early as the Sui dynasty, the Turks had become a major militarised force employed by the Chinese. When the Khitans began raiding north-east China in 605, a Chinese general led 20,000 Turks against them, distributing Khitan livestock and women to the Turks as a reward. On two occasions between 635 and 636, Tang royal princesses were married to Turk mercenaries or generals in Chinese service.

Throughout the Tang dynasty until the end of 755, there were approximately ten Turkic generals serving under the Tang. While most of the Tang army was made of '' fubing(府兵)'' Chinese conscripts, the majority of the troops led by Turkic generals were of non-Chinese origin, campaigning largely in the western frontier where the presence of '' fubing(府兵)'' troops was low. Some "Turkic" troops were nomadisized Han Chinese, a desinicized people.

Civil war in China was almost totally diminished by 626, along with the defeat in 628 of the Ordos Chinese warlord Liang Shidu

Liang Shidu (梁師都) (died June 3, 628) was an agrarian leader who rebelled against the rule of the Chinese dynasty Sui Dynasty near the end of the reign of Emperor Yang of Sui. He, claiming the title of Emperor of Liang with the aid from Ea ...

; after these internal conflicts, the Tang began an offensive against the Turks. In the year 630, Tang armies captured areas of the Ordos Desert, modern-day Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

province, and southern Mongolia

Mongolia; Mongolian script: , , ; lit. "Mongol Nation" or "State of Mongolia" () is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south. It covers an area of , with a population of just 3.3 million ...

from the Turks.

After this military victory, Emperor Taizong won the title of Great Khan amongst the various Turks in the region who pledged their allegiance to him and the Chinese empire (with several thousand Turks traveling into China to live at Chang'an). On June 11, 631, Emperor Taizong also sent envoys to the Eastern Turkic tribes bearing gold and silk in order to persuade the release of enslaved Chinese prisoners who were captured during the transition from Sui to Tang from the northern frontier; this embassy succeeded in freeing 80,000 Chinese men and women who were then returned to China.

While the Turks were settled in the Ordos region (former territory of the Xiongnu

The Xiongnu (, ) were a tribal confederation of nomadic peoples who, according to ancient Chinese sources, inhabited the eastern Eurasian Steppe from the 3rd century BC to the late 1st century AD. Modu Chanyu, the supreme leader after 20 ...

), the Tang government took on the military policy of dominating the central steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without trees apart from those near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the temperate gras ...

. Like the earlier Han dynasty, the Tang dynasty, along with Turkic allies like the Uyghurs, conquered and subdued Central Asia during the 640s and 650s. During Emperor Taizong's reign alone, large campaigns were launched against not only the Göktürks, but also separate campaigns against the Tuyuhun, and the Xueyantuo

The Xueyantuo were an ancient Tiele tribe and khaganate in Northeast Asia who were at one point vassals of the Göktürks, later aligning with the Tang dynasty against the Eastern Göktürks.

Names Xue

''Xue'' 薛 appeared earlier as ' ...

. Taizong also launched campaigns against the oasis states of the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hyd ...

, beginning with the annexation of Gaochang in 640. The nearby kingdom of Karasahr was captured by the Tang in 644 and the kingdom of Kucha was conquered in 649.

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who invaded the Western Turks ruled by the qaghan Ashina Helu in 657 with an army led by

The expansion into Central Asia continued under Taizong's successor, Emperor Gaozong, who invaded the Western Turks ruled by the qaghan Ashina Helu in 657 with an army led by Su Dingfang

Su Dingfang () (591–667), formal name Su Lie () but went by the courtesy name of Dingfang, formally Duke Zhuang of Xing (), was a Chinese military general of the Tang Dynasty who succeeded in destroying the Western Turkic Khaganate in 657. He wa ...

. Ashina was defeated and the khaganate was absorbed into the Tang empire. The territory was administered through the Anxi Protectorate and the Four Garrisons of Anxi

The Four Garrisons of Anxi were Chinese military garrisons installed by the Tang dynasty between 648 and 658. They were stationed at the Indo-European city-states of Qiuci (Kucha), Yutian (Hotan), Shule (Kashgar) and Yanqi ( Karashahr). The ...

. Tang hegemony beyond the Pamir Mountains

The Pamir Mountains are a mountain range between Central Asia and Pakistan. It is located at a junction with other notable mountains, namely the Tian Shan, Karakoram, Kunlun, Hindu Kush and the Himalaya mountain ranges. They are among the wor ...

in Afghanistan ended with revolts by the Turks in 665, but the Tang retained a military presence in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. These holdings were later invaded by the Tibetan Empire

The Tibetan Empire (, ; ) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of imperial expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. The empire further expanded under the 3 ...

to the south in 670.

Tang rivalry with the Tibetan Empire

The Tang Empire competed with the

The Tang Empire competed with the Tibetan Empire

The Tibetan Empire (, ; ) was an empire centered on the Tibetan Plateau, formed as a result of imperial expansion under the Yarlung dynasty heralded by its 33rd king, Songtsen Gampo, in the 7th century. The empire further expanded under the 3 ...

for control of areas in Inner and Central Asia, which was at times settled with marriage alliances such as the marrying of Princess Wencheng (d. 680) to Songtsän Gampo (d. 649). A Tibetan tradition mentions that after Songtsän Gampo's death in 649 AD, Chinese troops captured Lhasa. The Tibetan scholar Tsepon W. D. Shakabpa

Tsepon Wangchuk Deden Shakabpa (, January 11, 1907 – February 23, 1989) was a Tibetan nobleman, scholar, statesman and former Finance Minister of the government of Tibet.

Biography

Tsepon Shakabpa was born in Lhasa Tibet. His father, Laja Tas ...

believes that the tradition is in error and that "those histories reporting the arrival of Chinese troops are not correct" and claims that the event is mentioned neither in the Chinese annals nor in the manuscripts of Dunhuang

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in Northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Dunhuang was a major s ...

.

There was a long string of conflicts with Tibet over territories in the Tarim Basin

The Tarim Basin is an endorheic basin in Northwest China occupying an area of about and one of the largest basins in Northwest China.Chen, Yaning, et al. "Regional climate change and its effects on river runoff in the Tarim Basin, China." Hyd ...

between 670–692 and in 763 the Tibetans even captured the capital of China, Chang'an

Chang'an (; ) is the traditional name of Xi'an. The site had been settled since Neolithic times, during which the Yangshao culture was established in Banpo, in the city's suburbs. Furthermore, in the northern vicinity of modern Xi'an, Qin ...

, for fifteen days during the An Shi Rebellion

The An Lushan Rebellion was an uprising against the Tang dynasty of China towards the mid-point of the dynasty (from 755 to 763), with an attempt to replace it with the Yan dynasty. The rebellion was originally led by An Lushan, a general office ...

. In fact, it was during this rebellion that the Tang withdrew its western garrisons stationed in what is now Gansu

Gansu (, ; alternately romanized as Kansu) is a province in Northwest China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeast part of the province.

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibe ...

and Qinghai

Qinghai (; alternately romanized as Tsinghai, Ch'inghai), also known as Kokonor, is a landlocked province in the northwest of the People's Republic of China. It is the fourth largest province of China by area and has the third smallest po ...

, which the Tibetans then occupied along with the territory of Central Asia. Hostilities between the Tang and Tibet continued until they signed a formal peace treaty in 821. The terms of this treaty, including the fixed borders between the two countries, are recorded in a bilingual inscription on a stone pillar outside the Jokhang temple in Lhasa.

Arrival of Islam

In the 8th century, Islam began to penetrate the region, the desert nomads ofArabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Pl ...

could militarily match the nomads of the steppe, and the early Caliphate, Arab Empire gained control over parts of Central Asia. The early conquests under Qutayba ibn Muslim (705–715) were soon reversed by a combination of native uprisings and invasion by the Turgesh, but the collapse of the Turgesh khaganate after 738 opened the way for the re-imposition of Muslim authority under Nasr ibn Sayyar.

The Arab invasion also saw Chinese influence expelled from western Central Asia. At the Battle of Talas in 751 an Arab army decisively defeated a Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

force, and for the next several centuries Middle Eastern influences would dominate the region. Large-scale Islamization however did not begin until the 9th century, running parallel with the fragmentation of Abbasid political authority and the emergence of local Iranian and Turkic dynasties like the Samanids.

Steppe empires

Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths, and sometimes also referred to as the Classical Scythians and the Pontic Scythians, were an ancient Eastern

* : "In modern scholarship the name 'Sakas' is reserved for the ancient tribes of northern and eastern Cent ...

developed the saddle, and by the time of the Alans the use of the stirrup had begun. Horses continued to grow larger and sturdier so that chariots were no longer needed as the horses could carry men with ease. This greatly increased the mobility of the nomads; it also freed their hands, allowing them to use the bow and arrow, bow from horseback.

Using small but powerful composite bows, the steppe people gradually became the most powerful military force in the world. From a young age, almost the entire male population was trained in riding and archery, both of which were necessary skills for survival on the steppe. By adulthood, these activities were second nature. These mounted archers were more mobile than any other force at the time, being able to travel forty miles per day with ease.

The steppe peoples quickly came to dominate Central Asia, forcing the scattered city states and kingdoms to pay them tribute or face annihilation. The martial ability of the steppe peoples was limited, however, by the lack of political structure within the tribes. Confederations of various groups would sometimes form under a ruler known as a Khan (title), khan. When large numbers of nomads acted in unison they could be devastating, as when the Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

arrived in Western Europe. However, tradition dictated that any dominion conquered in such wars should be divided among all of the khan's sons, so these empires often declined as quickly as they formed.

Once the foreign powers were expelled, several indigenous empires formed in Central Asia. The Hephthalites were the most powerful of these nomad groups in the 6th and 7th century and controlled much of the region. In the 10th and 11th centuries the region was divided between several powerful states including the Samanid dynasty, that of the Seljuk Turks, and the Khwarezmid Empire.

The most spectacular power to rise out of Central Asia developed when Genghis Khan united the tribes of Mongolia. Using superior military techniques, the Mongol Empire spread to comprise all of Central Asia and China as well as large parts of Russia, and the Middle East. After Genghis Khan died in 1227, most of Central Asia continued to be dominated by the Mongol successor Chagatai Khanate. This state proved to be short lived, as in 1369 Timur, a Turco-Mongol ruler, conquered most of the region.

Even harder than keeping a steppe empire together was governing conquered lands outside the region. While the steppe peoples of Central Asia found conquest of these areas easy, they found governing almost impossible. The diffuse political structure of the steppe confederacies was maladapted to the complex states of the settled peoples. Moreover, the armies of the nomads were based upon large numbers of horses, generally three or four for each warrior. Maintaining these forces required large stretches of grazing land, not present outside the steppe. Any extended time away from the homeland would thus cause the steppe armies to gradually disintegrate. To govern settled peoples the steppe peoples were forced to rely on the local bureaucracy, a factor that would lead to the rapid assimilation of the nomads into the culture of those they had conquered. Another important limit was that the armies, for the most part, were unable to penetrate the forested regions to the north; thus, such states as Republic of Novgorod, Novgorod and Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy began to grow in power.

In the 14th century much of Central Asia, and many areas beyond it, were conquered by Timur (1336–1405) who is known in the west as Tamerlane. It was during Timur's reign that the nomadic steppe culture of Central Asia fused with the settled culture of Iran. One of its consequences was an entirely new visual language that glorified Timur and subsequent Timurid rulers. This visual language was also used to articulate their commitment to Islam. Timur's large empire collapsed soon after his death, however. The region then became divided among a series of smaller Khanates, including the Khanate of Khiva, the Khanate of Bukhara, the Khanate of Kokand, and the Khanate of Kashgar.

Once the foreign powers were expelled, several indigenous empires formed in Central Asia. The Hephthalites were the most powerful of these nomad groups in the 6th and 7th century and controlled much of the region. In the 10th and 11th centuries the region was divided between several powerful states including the Samanid dynasty, that of the Seljuk Turks, and the Khwarezmid Empire.

The most spectacular power to rise out of Central Asia developed when Genghis Khan united the tribes of Mongolia. Using superior military techniques, the Mongol Empire spread to comprise all of Central Asia and China as well as large parts of Russia, and the Middle East. After Genghis Khan died in 1227, most of Central Asia continued to be dominated by the Mongol successor Chagatai Khanate. This state proved to be short lived, as in 1369 Timur, a Turco-Mongol ruler, conquered most of the region.

Even harder than keeping a steppe empire together was governing conquered lands outside the region. While the steppe peoples of Central Asia found conquest of these areas easy, they found governing almost impossible. The diffuse political structure of the steppe confederacies was maladapted to the complex states of the settled peoples. Moreover, the armies of the nomads were based upon large numbers of horses, generally three or four for each warrior. Maintaining these forces required large stretches of grazing land, not present outside the steppe. Any extended time away from the homeland would thus cause the steppe armies to gradually disintegrate. To govern settled peoples the steppe peoples were forced to rely on the local bureaucracy, a factor that would lead to the rapid assimilation of the nomads into the culture of those they had conquered. Another important limit was that the armies, for the most part, were unable to penetrate the forested regions to the north; thus, such states as Republic of Novgorod, Novgorod and Grand Duchy of Moscow, Muscovy began to grow in power.

In the 14th century much of Central Asia, and many areas beyond it, were conquered by Timur (1336–1405) who is known in the west as Tamerlane. It was during Timur's reign that the nomadic steppe culture of Central Asia fused with the settled culture of Iran. One of its consequences was an entirely new visual language that glorified Timur and subsequent Timurid rulers. This visual language was also used to articulate their commitment to Islam. Timur's large empire collapsed soon after his death, however. The region then became divided among a series of smaller Khanates, including the Khanate of Khiva, the Khanate of Bukhara, the Khanate of Kokand, and the Khanate of Kashgar.

Early modern period (16th to 19th centuries)

The lifestyle that had existed largely unchanged since 500 BCE began to disappear after 1500. Important changes to the world economy in the 14th and 15th century reflected the impact of the development of nautical technology. Ocean trade routes were pioneered by the Europeans, who had been cut off from theSilk Road

The Silk Road () was a network of Eurasian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 miles), it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and rel ...

by the Muslim states that controlled its western termini. The long-distance trade linking East Asia and India to Western Europe increasingly began to move over the seas and not through Central Asia. However, the emergence of Russia as a world power enabled Central Asia to continue its role as a conduit for overland trade of other sorts, now linking India with Russia on a north–south axis.

An even more important development was the introduction of gunpowder-based weapons. The gunpowder revolution allowed settled peoples to defeat the steppe horsemen in open battle for the first time. Construction of these weapons required the infrastructure and economies of large societies and were thus impractical for nomadic peoples to produce. The domain of the nomads began to shrink as, beginning in the 15th century, the settled powers gradually began to conquer Central Asia.

The last steppe empire to emerge was that of the Dzungars who conquered much of East Turkestan and Mongolia. However, in a sign of the changed times they proved unable to match the Chinese and were decisively defeated by the forces of the

An even more important development was the introduction of gunpowder-based weapons. The gunpowder revolution allowed settled peoples to defeat the steppe horsemen in open battle for the first time. Construction of these weapons required the infrastructure and economies of large societies and were thus impractical for nomadic peoples to produce. The domain of the nomads began to shrink as, beginning in the 15th century, the settled powers gradually began to conquer Central Asia.

The last steppe empire to emerge was that of the Dzungars who conquered much of East Turkestan and Mongolia. However, in a sign of the changed times they proved unable to match the Chinese and were decisively defeated by the forces of the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

. In the 18th century the Qing emperors, themselves originally from the far eastern edge of the steppe, campaigned in the west and in Mongolia, with the Qianlong Emperor taking control of Xinjiang in 1758. The Mongol threat was overcome and much of Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China. Its border includes most of the length of China's border with the country of Mongolia. Inner Mongolia also accounts for a ...

was annexed to China.

One Turko-Mongolic dynasty that remained prominent during this period was the Mughal Empire, whose founder Babur traced descent to Timur. While the Mughals were never able to conquer Babur's original domains in Fergana Valley, which fell to the Shaybanids, they maintained influence in the Afghanistan region until the late 17th century even as they dominated India. After the Mughal Empire's decline in the 18th century, the Durrani Empire from Afghanistan would briefly overrun the North Western region of India, by the 19th century, the rise of the British Empire would limit the impact of Afghan conquerors.