History Of Baton Rouge, Louisiana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The foundation of

''Southeastern Archaeology'', Vol. 13, No. 2, Winter 1994, accessed November 4, 2011 Proto-

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge ( ; ) is a city in and the capital of the U.S. state of Louisiana. Located the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, it is the parish seat of East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana's most populous parish—the equivalent of counties ...

, dates to 1721, at the site of a ''bâton rouge'' or "red stick" Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsLouisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

in 1849.

Prehistory

Human habitation in the Baton Rouge area has been dated to about 8000 BC based on evidence found along the Mississippi, Comite, and Amite rivers. Earthwork mounds were built by hunter-gatherer societies in the Middle Archaic period, from roughly the 4th millennium BC.Rebecca Saunders, "The Case for Archaic Period Mounds in Southeastern Louisiana"''Southeastern Archaeology'', Vol. 13, No. 2, Winter 1994, accessed November 4, 2011 Proto-

Muskogean

Muskogean (also Muskhogean, Muskogee) is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally div ...

divided into its daughter languages by about 1000 BC; a cultural boundary between either side of Mobile Bay

Mobile Bay ( ) is a shallow inlet of the Gulf of Mexico, lying within the state of Alabama in the United States. Its mouth is formed by the Fort Morgan Peninsula on the eastern side and Dauphin Island, a barrier island on the western side. The ...

and the Black Warrior River

The Black Warrior River is a waterway in west-central Alabama in the southeastern United States. The river rises in the extreme southern edges of the Appalachian Highlands and flows 178 miles (286 km) to the Tombigbee River, of which the ...

begins to appear between about 1200 BC and 500 BC, the Middle "Gulf Formational Stage". Eastern Muskogean began to diversify internally in the first half of the 1st millennium AD.

The early Muskogean nations were the bearers of the Mississippian culture which formed around AD 800.

By the time the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

made their first forays inland from the shores of the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico ( es, Golfo de México) is an ocean basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, largely surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United ...

in the early 16th century, many political centers of the Mississippians were already in decline, or abandoned, the region at the time presenting as a collection of moderately-sized native chiefdoms interspersed with autonomous villages and tribal groups.

Colonial period

1699–1763: French period

French explorer Sieur d'Iberville led an exploration party up theMississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

in 1699.

The explorers saw a red pole marking the boundary between the Houma and Bayagoula The Bayagoula were a Native American tribe from what is now called Mississippi and Louisiana in the southern United States. Due to transcription errors amongst cartographers who mistakenly rewrote the tribe's name as their name is erroneously assu ...

tribal hunting grounds. The French name ''le bâton rouge'' ("the red pole") is the translation of a native term rendered as

''Istrouma'', possibly a corruption of the Choctaw ''iti humma'' "red pole";

André-Joseph Pénicaut, a carpenter traveling with d'Iberville, published the first full-length account of the expedition in 1723. According to Pénicaut,

From there [ Manchacq] we went five leagues higher and found very high banks called ''écorts'' in that region, and in savage called ''Istrouma'' which means red stick 'bâton rouge'' as at this place there is a post painted red that the savages have sunk there to mark the land line between the two nations, namely: the land of the Bayagoulas which they were leaving and the land of another nation—thirty leagues upstream from the ''baton rouge''—named the Oumas.See also Red Sticks for the ceremonial use of red sticks among the

Muscogee

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy ( in the Muscogee language), are a group of related indigenous (Native American) peoples of the Southeastern WoodlandsSouthern University.Irene Stocksieker Di Maio (ed.), ''Gerstäcker's Louisiana: Fiction and Travel Sketches from Antebellum Times Through Reconstruction'', LSU Press (2006

p. 307

It was reportedly a thirty-foot-high painted pole adorned with fish bones. The settlement of Baton Rouge by Europeans began in 1721 when a military post was established by French colonists.

In 1849, the Louisiana state legislature in New Orleans, dominated in number by wealthy rural planters, decided to move the seat of government to Baton Rouge. The majority of representatives feared a concentration of power in the state's largest city and the continuing strong influence of French Creoles in politics. In 1840, New Orleans' population was slightly over 102,000, then the third-largest city in the United States. Its thriving economy was largely sustained by the by-products of the domestic

In 1849, the Louisiana state legislature in New Orleans, dominated in number by wealthy rural planters, decided to move the seat of government to Baton Rouge. The majority of representatives feared a concentration of power in the state's largest city and the continuing strong influence of French Creoles in politics. In 1840, New Orleans' population was slightly over 102,000, then the third-largest city in the United States. Its thriving economy was largely sustained by the by-products of the domestic

digital version on ''Documents of the American South'', University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Twain wrote further of the city:

Throughout

Throughout

NPR, 13 Jun 2003, accessed 5 Dec 2010 The boycott was led by the newly formed United Defense League (UDL), under the direction of Willis Reed, later publisher of the ''Baton Rouge'' newspaper; Reverend T. J. Jemison and Raymond Scott. A volunteer "free ride" system, coordinated through black churches, supported the efforts and helped provide transportation for African Americans. In response to the boycott, the Baton Rouge city council adopted an ordinance that changed segregated seating so that black patrons would be enabled to fill up seats from the rear forward and whites would fill seats from front to back, both on a first-come-first-served basis. They avoided problems of an earlier ordinance by stipulating that the races did not sit in the same rows. In the view of many historians, the boycott's success in getting justice for black bus riders led the way for larger organized efforts within the civil rights movement. The actions and participants were commemorated June 19–21, 2003, on the 50th anniversary of the boycott. A community forum and events were held by Southern University and"Criminal Anarchy" in Louisiana

~ Civil Rights Movement Archive In 1964 and 1965, passage of federal civil rights legislation ended legal segregation and began to enforce African Americans' constitutional rights as citizens to vote and sit on juries.

p. 307

It was reportedly a thirty-foot-high painted pole adorned with fish bones. The settlement of Baton Rouge by Europeans began in 1721 when a military post was established by French colonists.

1763–1779: British period

On February 10, 1763, theTreaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

was signed following France's defeat by Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It i ...

in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

. France ceded its territory in North America to Britain and Spain; Britain gained all French lands east of the Mississippi, except .

During the Great Expulsion

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian peo ...

concurrent with the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, the North American front of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (175 ...

, British colonial officers expelled about 11,000 Acadians from Acadia

Acadia (french: link=no, Acadie) was a colony of New France in northeastern North America which included parts of what are now the The Maritimes, Maritime provinces, the Gaspé Peninsula and Maine to the Kennebec River. During much of the 17t ...

from eastern Canada. Many were transported to France and subsequently resettled in southern Louisiana (New Spain)

Spanish Louisiana ( es, link=no, la Luisiana) was a governorate and administrative district of the Viceroyalty of New Spain from 1762 to 1801 that consisted of a vast territory in the center of North America encompassing the western basin of t ...

; they settled in an area west and south of Baton Rouge that would come to be known as Acadiana. The first group of Acadian settlers arrived in 1765, with Joseph Broussard

Joseph Broussard (1702–1765), also known as Beausoleil ( en, Beautiful Sun), was a leader of the Acadian people in Acadia; later Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and New Brunswick. Broussard organized a Mi'kmaq and Acadian militias against th ...

. (At this point the Mississippi River was the dividing line between the newly-Spanish jurisdiction on the west, including Acadiana, and the newly-British West Florida

British West Florida was a colony of the Kingdom of Great Britain from 1763 until 1783, when it was ceded to Spain as part of the Peace of Paris.

British West Florida comprised parts of the modern U.S. states of Louisiana, Mississippi, Alab ...

, including Baton Rouge, on the east side.)

Eventually the settlers began calling themselves Cajuns

The Cajuns (; French: ''les Cadjins'' or ''les Cadiens'' ), also known as Louisiana '' Acadians'' (French: ''les Acadiens''), are a Louisiana French ethnicity mainly found in the U.S. state of Louisiana.

While Cajuns are usually described a ...

, a name derived from Acadians (French: ''Acadiens

The Acadians (french: Acadiens , ) are an ethnic group descended from the French who settled in the New France colony of Acadia during the 17th and 18th centuries. Most Acadians live in the region of Acadia, as it is the region where the de ...

''.) They maintained a separate culture from that of later Anglo-American Protestant settlers, continuing their traditions of distinct clothing, music, food, and Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

faith. Today their descendants are part of the rich cultural "stew" of the Baton Rouge area.

Baton Rouge, now part of the newly established British province of West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

, suddenly had strategic significance as the southwesternmost corner of British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestow ...

. Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

for a period had rule of New Orleans and all of the former French lands on the west side of the Mississippi River. They administered numerous historically-French colonial towns, such as St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

and Ste. Genevieve in present-day Missouri.

Baton Rouge slowly developed as a town under British rule. The authorities, headquartered in Pensacola

Pensacola () is the westernmost city in the Florida Panhandle, and the county seat and only incorporated city of Escambia County, Florida, United States. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 54,312. Pensacola is the principal ci ...

, awarded land grants and were successful in attracting European-American settlers. When the older British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America rebelled, beginning in 1775, the newer colony of West Florida — lacking a history of local government and distrustful of the potentially hostile Spanish nearby — remained loyal to the British Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

.

In 1778 during the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, France declared war on Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, and in 1779 Spain followed suit. That year, the Spanish Governor ''Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

'' Bernardo de Gálvez

Bernardo Vicente de Gálvez y Madrid, 1st Count of Gálvez (23 July 1746 – 30 November 1786) was a Spanish military leader and government official who served as colonial governor of Spanish Louisiana and Cuba, and later as Viceroy of New Sp ...

led a militia of nearly 1,400 soldiers and a small contingent of rebellious English-speaking colonials from New Orleans toward Baton Rouge. They were victorious in the Battle of Fort Bute and the naval Battle of Lake Pontchartrain

The Battle of Lake Pontchartrain was a single-ship action on September 10, 1779, part of the Anglo-Spanish War 1779, Anglo-Spanish War. It was fought between the Kingdom of Great Britain, British sloop-of-war and the Continental Navy schooner ...

, before capturing the recently constructed Fort New Richmond

Fort New Richmond was built by the British in 1779 on the east bank of the Mississippi River in what was later to become Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The Spanish took control of the fort in 1779 and renamed it Fort San Carlos.

Revolutionary War

The ...

in the Battle of Baton Rouge. Spanish officials renamed the site Fort San Carlos and took control of Baton Rouge.

At the conclusion of the Revolutionary War, Great Britain turned West Florida

West Florida ( es, Florida Occidental) was a region on the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico that underwent several boundary and sovereignty changes during its history. As its name suggests, it was formed out of the western part of former S ...

over to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

.

1779–1810: Spanish period

A colony of Pennsylvania German farmers migrated north fromBayou Manchac

Bayou Manchac is an U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed June 20, 2011 bayou in southeast Louisiana, USA. First called the Iberville River ("rivière d'Iberville") by its Frenc ...

, after a series of floods in the 1780s, and settled to the south of Baton Rouge. Known locally as "Dutch Highlanders" ("Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

" being a corruption of ''Deutsch'', in reference to their language), they settled along a line of bluffs that served as barrier to the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it fl ...

floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river which stretches from the banks of its channel to the base of the enclosing valley walls, and which experiences flooding during periods of high discharge.Goudi ...

.

Historic Highland Road, located in the heart of present-day Baton Rouge, was originally established as a supply road for the indigo

Indigo is a deep color close to the color wheel blue (a primary color in the RGB color space), as well as to some variants of ultramarine, based on the ancient dye of the same name. The word "indigo" comes from the Latin word ''indicum'', m ...

and cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fiber that grows in a boll, or protective case, around the seeds of the cotton plants of the genus '' Gossypium'' in the mallow family Malvaceae. The fiber is almost pure cellulose, and can contain minor pe ...

plantations of the early settlers. The ethnic Germans named two major roads in the area, Essen and Siegen

Siegen () is a city in Germany, in the south Westphalian part of North Rhine-Westphalia.

It is located in the district of Siegen-Wittgenstein in the Arnsberg region. The university town (nearly 20,000 students in the 2018–2019 winter semest ...

lanes, after cities in Germany. The Kleinpeter and Staring families were among the most prominent of the early German families in the area. Their descendants have remained active in local business affairs since.

In 1800, the Tessier-Lafayette buildings were built on what is now Lafayette Street and survive today. Development of sections followed. In 1805, the Spanish administrator, the Francophone creole ''Don

Don, don or DON and variants may refer to:

Places

*County Donegal, Ireland, Chapman code DON

*Don (river), a river in European Russia

*Don River (disambiguation), several other rivers with the name

*Don, Benin, a town in Benin

*Don, Dang, a vill ...

'' Carlos Louis Boucher de Grand Pré, commissioned a plan for the area today known as Spanish Town. In 1806, Elias Beauregard led a planning commission for what is today known as Beauregard Town.

Statehood to Civil War

1810–1812: Republic of West Florida & Orleans Territory

As a result of the United States' 1803Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, it gained the former French territory in North America ( retroceded by Spain to France). At that point, Spanish West Florida

Spanish West Florida (Spanish: ''Florida Occidental'') was a province of the Spanish Empire from 1783 until 1821, when both it and East Florida were ceded to the United States.

The region of West Florida initially had the same borders as the er ...

was almost entirely surrounded by the United States and its possessions. The Spanish fort at Baton Rouge became the only non-U.S. military post on the Mississippi River.

Several of the inhabitants of the Baton Rouge District began to organize conventions to plan a rebellion, among them Fulwar Skipwith

Fulwar Skipwith (February 21, 1765 – January 7, 1839) was an American soldier, diplomat, politician and farmer. who served as a U.S. Consul in Martinique, and later as the U.S. Consul-General in France. He was instrumental in negotiating the L ...

, a Baton Rouge citizen. At least one meeting was held in a house on a street which has since been renamed Convention Street, in their honor. On September 23, 1810, the rebels overcame the Spanish garrison at Fort San Carlos; they unfurled the flag of the new Republic of West Florida, known as the Bonnie Blue Flag. The West Florida Republic existed for almost ninety (90) days, during which St. Francisville in present-day West Feliciana Parish served as its capital.

Seizing the opportunity, President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for h ...

ordered W. C. C. Claiborne to move in and seize the fledgling republic to annex into the Territory of Orleans

The Territory of Orleans or Orleans Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from October 1, 1804, until April 30, 1812, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Louisiana.

History

In 180 ...

. Madison used the premise that the territory had been a part of the U.S. since 1803, citing the terms of the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

, an explanation largely believed to be a deliberate error. The rebels provided no resistance to Claiborne's forces. With minor resentment, they watched the " Stars and Stripes" raised on December 10, 1810. For the first time, nearly all of the land that would become the state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

of Louisiana lay within U.S. territorial borders.

1812–1860: Early statehood & incorporation as capital

In 1812, Louisiana was admitted to the Union as astate

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

, and in 1817 Baton Rouge was incorporated. As the town was a strategic military post, between 1819 and 1822 the U.S. Army built the Pentagon Barracks, which became a major command post through the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

(1846–1848). Lieutenant Colonel Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

supervised construction of the Pentagon Barracks and served as its commander. In the 1830s, what is known today as the "Old Arsenal" was built. The unique structure originally served as a gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

magazine for the U.S. Army post.

In 1825, Baton Rouge was visited by the Marquis de Lafayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

, French hero of the American Revolution, as part of his triumphal tour of the United States. The town feted him as the guest of honor at a banquet and ball. To celebrate the occasion and honor him, the city changed the name of Second Street to Lafayette Street.

In 1849, the Louisiana state legislature in New Orleans, dominated in number by wealthy rural planters, decided to move the seat of government to Baton Rouge. The majority of representatives feared a concentration of power in the state's largest city and the continuing strong influence of French Creoles in politics. In 1840, New Orleans' population was slightly over 102,000, then the third-largest city in the United States. Its thriving economy was largely sustained by the by-products of the domestic

In 1849, the Louisiana state legislature in New Orleans, dominated in number by wealthy rural planters, decided to move the seat of government to Baton Rouge. The majority of representatives feared a concentration of power in the state's largest city and the continuing strong influence of French Creoles in politics. In 1840, New Orleans' population was slightly over 102,000, then the third-largest city in the United States. Its thriving economy was largely sustained by the by-products of the domestic slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

in addition to shipping; the city itself was the largest slave market in the nation. Products from the center of the country flowed through New Orleans for export, and ships arrived with a range of goods for the city and for towns and cities upriver. The 1840 population of Baton Rouge, on the other hand, was only 2,269.

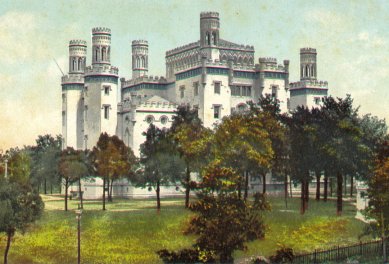

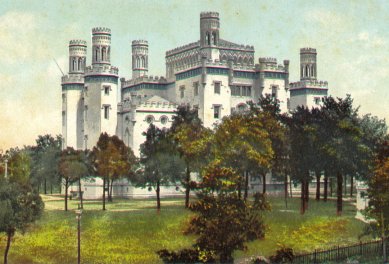

New York architect James H. Dakin was hired to design the new capitol in Baton Rouge. Rather than mimic the federal Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, as so many other capitol designers had done, he conceived a neo-Gothic medieval

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

castle, complete with turrets and crenellations

A battlement in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet (i.e., a defensive low wall between chest-height and head-height), in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at interv ...

, overlooking the Mississippi. In 1859, the Capitol was featured and favorably described in ''DeBow's Review

''DeBow's Review'' was a widely-circulated magazine

"DEBOW'S REVIEW" (publication titles/dates/locations/notes),

APS II, Reels 382 & 383, webpage

of "agricultural, commercial, and industrial progress and resource" in the American South during ...

'', the most prestigious periodical in the antebellum

Antebellum, Latin for "before war", may refer to:

United States history

* Antebellum South, the pre-American Civil War period in the Southern United States

** Antebellum Georgia

** Antebellum South Carolina

** Antebellum Virginia

* Antebellum ...

South. But the riverboat pilot and writer Mark Twain loathed the sight; later in his ''Life on the Mississippi'' (1874), he wrote, "It is pathetic ... that a whitewashed castle, with turrets and things ... should ever have been built in this otherwise honorable place."''Life on the Mississippi'', New York: Houghton and Company, 1874, Chap. 40, pp. 416-17digital version on ''Documents of the American South'', University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Twain wrote further of the city:

Baton Rouge was clothed in flowers, like a bride—no, much more so; like a greenhouse. For we were in the absolute South now—no modifications, no compromises, no half-way measures. TheDuring the first half of the nineteenth century, the city grew steadily as the result of steamboat trade and transportation. By the outbreak of themagnolia ''Magnolia'' is a large genus of about 210 to 340The number of species in the genus ''Magnolia'' depends on the taxonomic view that one takes up. Recent molecular and morphological research shows that former genera ''Talauma'', ''Dugandiodendro ...trees in the Capitol grounds were lovely and fragrant, with their dense rich foliage and huge snowball blossoms. ... We were certainly in the South at last; for here the sugar region begins, and theplantations A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...—vast green levels, with sugar-mill and negro quarters clustered together in the middle distance—were in view.

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states ...

in 1861, the population had more than doubled to nearly 5,500 people. The Civil War halted economic progress, but the city was not physically affected until it was occupied by Union forces in 1862.

1860–1865: Civil War

The first state to secede was South Carolina in December 1860; other states soon followed. In January 1861, Louisiana elected delegates to a state convention to decide the state's course of action. The convention voted for secession 112 to 17. Baton Rouge raised a number of volunteer companies for Confederate service, including the Pelican Rifles, the Delta Rifles, the Creole Guards, and the Baton Rouge Fencibles; about one-third of the town's male population eventually volunteered. The Confederates gave up Baton Rouge (which had a population of 5,429 in 1860) with little resistance, deciding to consolidate their forces elsewhere. In May 1862, Union troops entered the city and began the occupation of Baton Rouge. Confederate soldiers made only one attempt to retake Baton Rouge. However, even with the assistance of an elite group known as the Barbarians—which was based in Louisiana—they were outnumbered and outgunned. The town was severely damaged. However, Baton Rouge escaped the extreme devastation faced by cities that were major conflict points during the Civil War, and it still has many structures that predate it.Reconstruction to Civil rights era

1865–1900: Reconstruction era

The migration of manyfreedmen

A freedman or freedwoman is a formerly enslaved person who has been released from slavery, usually by legal means. Historically, enslaved people were freed by manumission (granted freedom by their captor-owners), emancipation (granted freedom a ...

into towns and cities in the South was reflected in growth in the black population of Baton Rouge. They moved out of rural areas to escape white control and to seek jobs and education more available in towns, as well as the safety of being in their own communities. In 1860, blacks (mostly slaves) made up nearly one-third of the town's population. By the 1880 U.S. census, Baton Rouge was 60 percent black. It was not until the 1920 census that the white population of Baton Rouge exceeded 50 percent of the total.

During the Reconstruction Era, state-level offices were located in New Orleans, which was a base for U.S. troops. Elections after 1868 were increasingly accompanied by violence and fraud as whites sought to regain power and suppress black voting. Following a disputed gubernatorial election in 1872, in 1874 thousands of paramilitary White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

members took over state government buildings in New Orleans for several days. Blacks continued to be elected to local office. Before the end of Reconstruction, signified by the withdrawal of Federal troops in 1877, the white Democratic Party politicians regained control of the state's and the city's political institutions. They had benefited from the violence and intimidation by white paramilitary groups such as the White League

The White League, also known as the White Man's League, was a white paramilitary terrorist organization started in the Southern United States in 1874 to intimidate freedmen into not voting and prevent Republican Party political organizing. Its f ...

to suppress black voting.

By 1880, Baton Rouge was recovering economically from the war years. The city's population that year reached 7,197, while its boundaries were unchanged. The biracial coalition of the Reconstruction years had been replaced at the state level by white Democrats who loathed the Republicans, eulogized the Confederacy, and preached white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White s ...

. At the end of the century, white Democrats in the state legislature effectively disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

freedmen and other blacks, including educated Louisiana Creole people, through changes to voter registration laws and the state constitution. They passed laws imposing legal racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

and " Jim Crow," imposing second-class status on African Americans. This system held into the 1960s until after passage of Federal civil rights legislation.

In 1886, a statue of a Confederate soldier was dedicated at the corner of Third Street and North Boulevard, in honor of those who fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. In the early 21st century, the statue was removed to enable construction, beginning in 2010, of the North Boulevard Town Square, located directly behind the Old Louisiana State Capitol. After construction is completed, the statue is to be installed at a final site on the grounds of the Old Capitol building.

In the 1890s, a more management-oriented style of conservatism developed among whites

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

in the city that continued into the early 20th century. Increased civic-mindedness and the arrival of the Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railway

The Louisville, New Orleans and Texas Railway was built between 1888 and 1890 and was admitted to the Illinois Central Railroad system in 1892. It ran between Memphis, Tennessee, and New Orleans, Louisiana, through Vicksburg, Mississippi, and Baton ...

stimulated investments in the local economy, attracted new businesses, and led to the development of more forward-looking leadership.

1900–1953: Early to mid-20th century

The city constructed new waterworks, promoted widespreadelectrification

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source.

The broad meaning of the term, such as in the history of technology, economic histor ...

of homes and businesses, and they passed several large bond issues for the construction of public buildings, new schools (which were racially segregated), paving of streets, drainage and sewer improvements, and the establishment of a municipal public health department. Due to the exclusion of blacks

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often in ...

from politics via disfranchisement, the segregated facilities and residential areas for African Americans were under-funded. This segment of the population was under-served in general, although they received no relief from paying taxes.

By the beginning of the twentieth century, Baton Rouge was being industrialized due to its strategic location for the production of petroleum, natural gas, and salt. In 1909 the Standard Oil Company (predecessor of present-day ExxonMobil) built a facility that lured other petrochemical firms. Although the waterfront was flooded in 1912, the city escaped extensive damage then and during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927

The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 was the most destructive river flood in the history of the United States, with inundated in depths of up to over the course of several months in early 1927. The uninflated cost of the damage has been estimat ...

— which did extensive damage in Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

and the Mississippi Delta.

In 1932, during the Great Depression, Governor Huey P. Long directed the construction of a new Louisiana State Capitol

The Louisiana State Capitol (french: Capitole de l'État de Louisiane) is the seat of government for the U.S. state of Louisiana and is located in downtown Baton Rouge. The capitol houses the chambers for the Louisiana State Legislature, made ...

, a public works project that was also a symbol of modernization. He also expanded and improved facilities to provide for the welfare of the people. The growth of the state government contributed to growth in related businesses and amenities for the city. Near the same time, both the Louisiana Institute for the Blind and the School for the Deaf and Dumb were built in Baton Rouge.

Throughout

Throughout World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, military demand for increased production at local chemical plants contributed to the growth of the city, generating many new defense jobs. In the late 1940s, Baton Rouge and East Baton Rouge Parish became a consolidated city/parish with a mayor/president leading the government. It was one of the first cities in the nation to consolidate with county government. The parish surrounds three other incorporated cities: Baker, Zachary, and Central.

1953–1968: Civil rights era

In 1953 Baton Rouge was the site of the first bus boycott by African Americans of the civil rights movement. On June 20, 1953 black citizens of Baton Rouge began an organized boycott of the segregated municipal bus system that lasted for eight days. As they made up 80% of the riders, their boycott strongly affected city revenues and they objected to having the number of seats they could use be limited and to being forced to give up seats to white riders. The boycott served as the model for the more famousMontgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United States ...

of 1955–1956.Debbie Elliott, "The First Civil Rights Bus Boycott: 50 Years Ago, Baton Rouge Jim Crow Protest Made History"NPR, 13 Jun 2003, accessed 5 Dec 2010 The boycott was led by the newly formed United Defense League (UDL), under the direction of Willis Reed, later publisher of the ''Baton Rouge'' newspaper; Reverend T. J. Jemison and Raymond Scott. A volunteer "free ride" system, coordinated through black churches, supported the efforts and helped provide transportation for African Americans. In response to the boycott, the Baton Rouge city council adopted an ordinance that changed segregated seating so that black patrons would be enabled to fill up seats from the rear forward and whites would fill seats from front to back, both on a first-come-first-served basis. They avoided problems of an earlier ordinance by stipulating that the races did not sit in the same rows. In the view of many historians, the boycott's success in getting justice for black bus riders led the way for larger organized efforts within the civil rights movement. The actions and participants were commemorated June 19–21, 2003, on the 50th anniversary of the boycott. A community forum and events were held by Southern University and

Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University (officially Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as LSU) is a public land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The university was founded in 1860 nea ...

.

The wave of student sit-ins

A sit-in or sit-down is a form of direct action that involves one or more people occupying an area for a protest, often to promote political, social, or economic change. The protestors gather conspicuously in a space or building, refusing to mo ...

that started in Greensboro

Greensboro (; formerly Greensborough) is a city in and the county seat of Guilford County, North Carolina, United States. It is the List of municipalities in North Carolina, third-most populous city in North Carolina after Charlotte, North Car ...

, North Carolina, on February 1, 1960, reached Baton Rouge on March 28 when seven Southern University (SU) students were arrested for sitting-in at a Kress lunch counter to seek service. Public education was still segregated and SU was a historically black college

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African-American community. M ...

. The following day, nine more students were arrested for sitting-in at the Greyhound Lines bus terminal. The next day Major Johns, an SU student and Congress of Racial Equality

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) is an African-American civil rights organization in the United States that played a pivotal role for African Americans in the civil rights movement. Founded in 1942, its stated mission is "to bring about ...

(CORE) member, led more than 3,000 students on a march to the state capitol to protest segregation and the arrests.

Major Johns and the 16 students arrested for sitting-in were expelled from SU and barred from all public colleges and universities in the state, threatening their education and future livelihoods. SU students organized a class boycott to win reinstatement of the expelled students. Fearing for the safety of their children, many parents withdrew their sons and daughters from the college. Eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

overturned the convictions of the arrested students. In 2004 they were awarded honorary degrees by Southern University and the state legislature passed a resolution in their honor.

In October 1961, SU students Ronnie Moore, Weldon Rougeau and Patricia Tate revived the Baton Rouge CORE chapter. After negotiations with downtown merchants failed to end segregation in retail stores, they called for a consumer boycott in early December, at the start of the busy holiday shopping season. Fourteen CORE pickets supporting the boycott were arrested in mid-December and held in jail for a month. More than 1,000 SU students marched to the state capitol on December 15 to protest. Police attacked them with dogs and tear-gas, and arrested more than 50 of them. Thousands rallied on the SU campus against segregation and in support of the arrested students. To prevent further disturbances, SU administrators closed the campus four days early for Christmas vacation .

In January 1962, U.S. Federal Judge Gordon West issued an injunction against CORE that banned all forms of protest of any kind at SU. The university expelled many activist students and state police troopers occupied the campus to quell further protests. Judge West's order was finally overturned by a higher court in 1964, but during the intervening years, civil rights activity was effectively suppressed.

In February 1962, Dion Diamond, a Freedom Rider

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions ''Morgan v. Virginia'' ...

and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field secretary, was arrested for entering the SU campus to meet with students. He was charged with "criminal anarchy" — attempting to overthrow the government of the State of Louisiana. SNCC Chairman Chuck McDew and white field secretary Bob Zellner

John Robert Zellner (born April 5, 1939) is an American civil rights activist. He graduated from Huntingdon College in 1961 and that year became a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as its first white field secretary. ...

were also arrested and charged with "criminal anarchy" when they visited Diamond in jail. Zellner was put in a cell with white prisoners, who attacked him as a "race-mixer" while the guards looked on. After years of legal proceedings, the charges against Diamond were dropped, but Diamond was forced to serve 60 days for other charges.~ Civil Rights Movement Archive

Late 20th century to present

In the 1970s, Baton Rouge experienced a boom in the petrochemical industry that resulted in expansion of the city away from the original center, resulting in the modern suburban sprawl. In recent years, however, government and business have begun a move back to the central district. A building boom that began in the 1990s continues today. At the turn of the 21st century, Baton Rouge maintained steady population growth and became a technological leader among cities in the South. Earning a rank of Number 1 on the list of America's ''most wired cities'' (more wired than and most of the 25 largest cities in the United States), Baton Rouge integrated advanced traffic camera systems, an extensive municipal broadband wireless network, and an advanced cellular telecommunications network into the city infrastructure. The city's 2000 Census population surpassed 225,000, exceeding that of regionally comparable cities includingMobile

Mobile may refer to:

Places

* Mobile, Alabama, a U.S. port city

* Mobile County, Alabama

* Mobile, Arizona, a small town near Phoenix, U.S.

* Mobile, Newfoundland and Labrador

Arts, entertainment, and media Music Groups and labels

* Mobile ( ...

and Montgomery in Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

and Corpus Christi in Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

.

On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Louisiana Gulf Coast

The Gulf Coast of the United States, also known as the Gulf South, is the coast, coastline along the Southern United States where they meet the Gulf of Mexico. The list of U.S. states and territories by coastline, coastal states that have a shor ...

. Although the damage was relatively minor in Baton Rouge, the city had power outages and service disruptions due to the hurricane. In addition, the city provided refuge for residents from New Orleans. Baton Rouge served as a headquarters for Federal (on site) and State emergency coordination and disaster relief in Louisiana.

By the end of the 2000s decade, Baton Rouge was one of the largest mid-sized American business cities and one of the fastest-growing metropolitan areas with populations under 1 million — with 633,261 residents in 2000 and an estimated 750,000 in 2008. (Baton Rouge's city population mushroomed after Hurricane Katrina as residents from the New Orleans metropolitan area

The New Orleans metropolitan area, designated the New Orleans–Metairie metropolitan statistical area by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget, or simply Greater New Orleans (french: Grande Nouvelle-Orléans, es, Gran Nueva Orleans), is a me ...

moved to escape the devastation; estimates in late 2005 put the displaced population at about 200,000 in the Baton Rouge area. Most returned to their original locations.)

Due to the hurricane refugees returning home and native Baton Rouge residents migrating to outlying parishes such as Livingston and Ascension, the U.S. Census Bureau in its 2007–08 estimate designated Baton Rouge as the second-fastest city in declining population. Baton Rouge has embarked on a process of urban growth and renewal, concentrating on downtown attractions. North Boulevard Town Square, for instance, provides both a place for city-center events and re-creates a connection to the river.

See also

* Timeline of Baton Rouge, Louisiana *History of Louisiana

The history of the area that is now the U.S. state of Louisiana, can be traced back thousands of years to when it was occupied by indigenous peoples. The first indications of permanent settlement, ushering in the Archaic period, appear about 5, ...

References

Further reading

* * Meyers, Rose. '' A History of Baton Rouge, 1699-1812'' (1976) {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Baton Rouge