High Court of Justice (1649) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The High Court of Justice was the court established by the

The High Court of Justice was the court established by the

The Death Warrant of King Charles I

. House of Lords Record Office.

The trial of King Charles I – defining moment for our constitutional liberties

', to the Anglo-Australasian Lawyers' association, on 22 January 1999. * February 1649 An Act to prevent the printing of any the Proceedings in the High Court of Justice, Erected for Trying of James Earl of Cambridge, and others, Without leave of the House of Commons, or the said Court

British History online

Trial of King Charles I - UK Parliament Living Heritage

Full text of the Ordinance that established the court

* Victor Louis Stater. ''The Political History of Tudor and Stuart England''

p. 144

Charges against Charles I * T. B Howell, T.B. ''A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason other crimes and misdemeanors from the earliest period until the year 1783'' Volume 12 of 21 Charles I to Charles II:

The Trial of Charles Stuart, King of England; Before the High court of Justice, for High Treason

* ttps://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A82426.0001.001/1:1?rgn=div1;view=fulltext Full text of the Act abolishing the Office of King, 17 March, 1649* Geoffrey Robertson, ''The Tyrannicide Brief'' (2005), Chatto & Windus

Contemporary London Gazette report on the trial and execution of Charles I

The High Court of Justice was the court established by the

The High Court of Justice was the court established by the Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rump" ...

to try Charles I, King of England, Scotland and Ireland. Even though this was an ''ad hoc

Ad hoc is a Latin phrase meaning literally 'to this'. In English, it typically signifies a solution for a specific purpose, problem, or task rather than a generalized solution adaptable to collateral instances. (Compare with '' a priori''.)

C ...

'' tribunal that was specifically created for the purpose of trying the king, its name was eventually used by the government as a designation for subsequent courts.

Background

TheEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War (1642β1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

had been raging for nearly an entire decade. After the First English Civil War

The First English Civil War took place in England and Wales from 1642 to 1646, and forms part of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. They include the Bishops' Wars, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Second English Civil War, the Anglo ...

, the parliamentarians accepted the premise that the King, although wrong, had been able to justify his fight, and that he would still be entitled to limited powers as King under a new constitutional settlement. By provoking the Second English Civil War

The Second English Civil War took place between February to August 1648 in Kingdom of England, England and Wales. It forms part of the series of conflicts known collectively as the 1639-1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which include the 1641β ...

even while defeated and in captivity, Charles was held responsible for unjustifiable bloodshed. The secret "Engagement" treaty with the Scots was considered particularly unpardonable; "a more prodigious treason", said Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

, "than any that had been perfected before; because the former quarrel was that Englishmen might rule over one another; this to vassalize us to a foreign nation." Cromwell up to this point had supported negotiations with the king but now rejected further negotiations.

In making war against Parliament, the king had caused the deaths of thousands. Estimated deaths from the first two English civil wars has been reported as 84,830 killed with estimates of another 100,000 dying from war-related disease. The war deaths totalled approximately 3.6% of the population, estimated to be around 5.1 million in 1650.

Following the second civil war, the New Model Army and the Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

s in Parliament were determined that the King should be punished, but they did not command a majority. Parliament debated whether to return the King to power and those who still supported Charles's place on the throne, mainly Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

s, tried once more to negotiate with him.

Furious that Parliament continued to countenance Charles as King, troops of the New Model Army marched on Parliament and purged the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. T ...

in an act later known as "Pride's Purge

Pride's Purge is the name commonly given to an event that took place on 6 December 1648, when soldiers prevented members of Parliament considered hostile to the New Model Army from entering the House of Commons of England.

Despite defeat in the ...

" after the commanding officer of the operation. On Wednesday, 6 December 1648, Colonel Thomas Pride

Colonel Thomas Pride (died 23 October 1658) was a Parliamentarian commander during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, best known as one of the regicides of Charles I and as the instigator of Pride's Purge.

Personal details

Thomas Pride was bor ...

's Regiment of Foot took up position on the stairs leading to the House, while Nathaniel Rich's Regiment of Horse provided backup. Pride himself stood at the top of the stairs. As Members of Parliament (MPs) arrived, he checked them against the list provided to him. Troops arrested 45 MPs and kept 146 out of parliament.

Only seventy-five people were allowed to enter and, even then, only at the army's bidding. On 13 December, the "Rump Parliament

The Rump Parliament was the English Parliament after Colonel Thomas Pride commanded soldiers to purge the Long Parliament, on 6 December 1648, of those members hostile to the Grandees' intention to try King Charles I for high treason.

"Rump" ...

", as the purged House of Commons came to be known, broke off negotiations with the King. Two days later, the Council of Officers

The Army Council was a body established in 1647 to represent the views of all levels of the New Model Army. It originally consisted of senior commanders, like Sir Thomas Fairfax, and representatives elected by their regiments, known as Agitators ...

of the New Model Army voted that the King be moved to Windsor

Windsor may refer to:

Places Australia

* Windsor, New South Wales

** Municipality of Windsor, a former local government area

* Windsor, Queensland, a suburb of Brisbane, Queensland

**Shire of Windsor, a former local government authority around Wi ...

"in order to the bringing of him speedily to justice". In the middle of December, the King was moved from Windsor to London.

The role of Parliament in ending a reign

Neither the involvement of Parliament in ending a reign nor the idea of trying a monarch was entirely novel. In two prior examples, the parliament had requested both the abdication of Edward II, and that of Richard II, in 1327 and 1399 respectively. However, in both these cases, Parliament acted at the behest of the new monarch. Parliament had established a regency council for Henry VI, although this was at the instigation of senior noblemen and Parliament claimed to be acting in the King's name. In the case of Lady Jane Grey, Parliament rescinded her proclamation as queen. She was subsequently tried, convicted and executed forhigh treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, but she was not brought to trial while still a reigning monarch.

Establishing the court

After the King had been moved to London, the Rump Parliament passed a Bill setting up what was described as a ''High Court of Justice in order to try Charles I forhigh treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

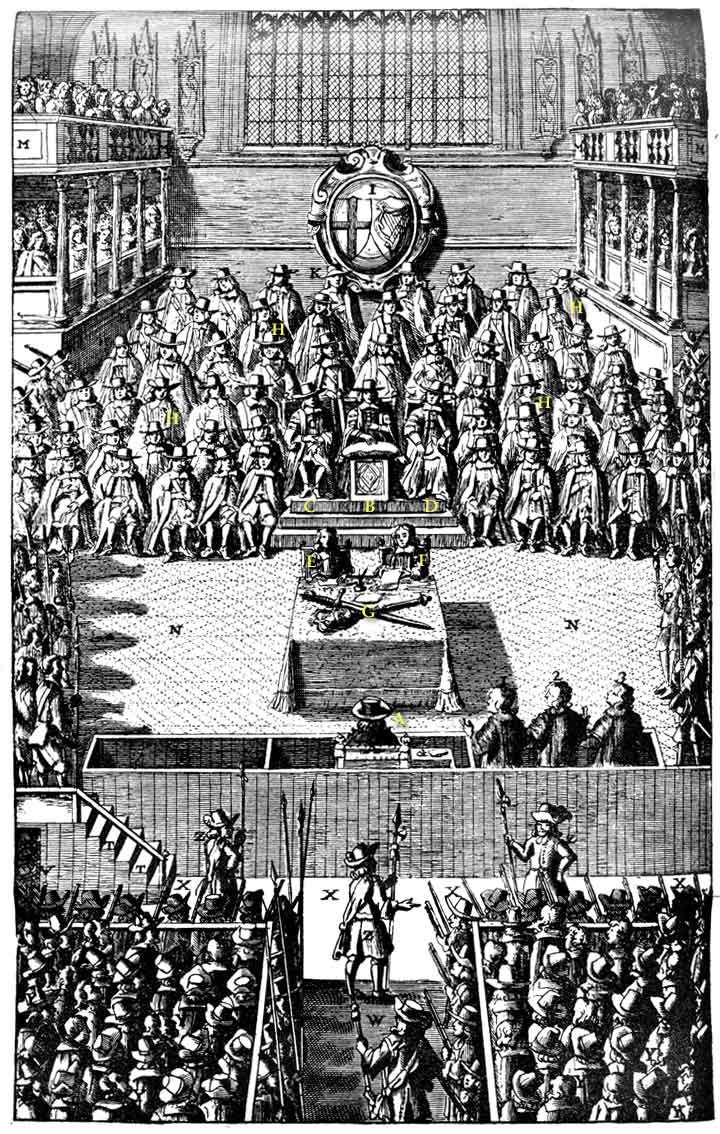

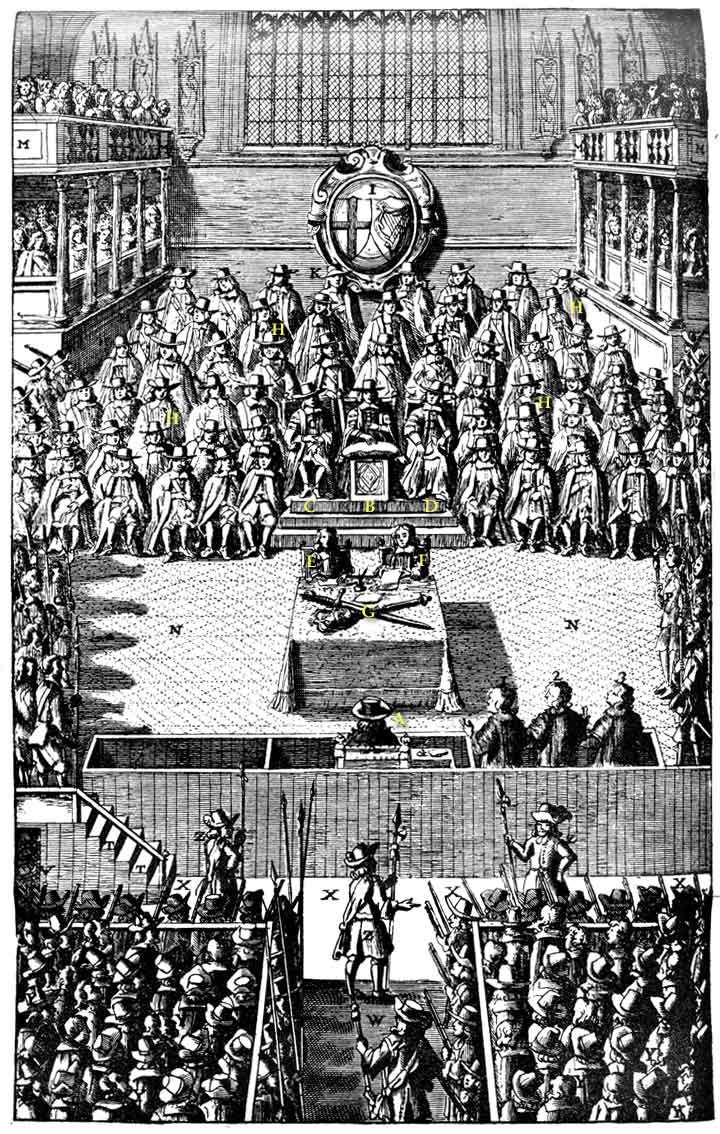

'' in the name of the people of England. The bill initially nominated 3 judges and 150 commissioners, but following opposition in the House of Lords, the judges and members of the Lords were removed. When the trial began, there were 135 commissioners who were empowered to try the King, but only 68 would ever sit in judgement. The Solicitor General John Cook was appointed prosecutor.

Charles was accused of treason against England by using his power to pursue his personal interest rather than the good of England. The charge against Charles I stated that the king, "for accomplishment of such his designs, and for the protecting of himself and his adherents in his and their wicked practices, to the same ends hath traitorously and maliciously levied war against the present Parliament, and the people therein represented", that the "wicked designs, wars, and evil practices of him, the said Charles Stuart, have been, and are carried on for the advancement and upholding of a personal interest of will, power, and pretended prerogative to himself and his family, against the public interest, common right, liberty, justice, and peace of the people of this nation". The indictment held him "guilty of all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars, or occasioned thereby".

Although the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

refused to pass the bill and the Royal Assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in oth ...

naturally was lacking, the Rump Parliament referred to the ordinance as an "Act" and pressed on with the trial anyway. The intention to place the King on trial was re-affirmed on 6 January by a vote of 29 to 26 with ''An Act of the Commons Assembled in Parliament''. citing Wedgwood, p. 122. At the same time, the number of commissioners was reduced to 135 any twenty of whom would form a quorum when the judges, members of the House of Lords and others who might be sympathetic to the King were removed.

The commissioners met to make arrangements for the trial on 8 January when well under half were present a pattern that was to be repeated at subsequent sessions. On 10 January, John Bradshaw was chosen as President of the Court. During the following ten days, arrangements for the trial were completed; the charges were finalised and the evidence to be presented was collected.

Trial

The trial began on 20 January 1649 inWestminster Hall

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north bank ...

, with a moment of high drama. After the proceedings were declared open, Solicitor General John Cook rose to announce the indictment

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of a ...

; standing immediately to the right of the King, he began to speak, but he had uttered only a few words when Charles attempted to stop him by tapping him sharply on the shoulder with his cane and ordering him to "Hold". Cook ignored this and continued, so Charles poked him a second time and rose to speak; despite this, Cook continued. At this point Charles, incensed at being thus ignored, struck Cook across the shoulder so forcefully that the ornate silver tip of the cane broke off, rolled down Cook's gown and clattered onto the floor between them. With nobody willing to pick it up for him, Charles had to stoop down to retrieve it himself.

When given the opportunity to speak, Charles refused to enter a plea, claiming that no court had jurisdiction over a monarch. He believed that his own authority to rule had been due to the divine right of kings given to him by God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

, and by the traditions and laws of England when he was crowned and anointed, and that the power wielded by those trying him was simply that of force of arms. Charles insisted that the trial was illegal, explaining, "No learned lawyer will affirm that an impeachment can lie against the King ... one of their maxims is, that the King can do no wrong." Charles asked "I would know by what power I am called hither. I would know by what authority, I mean lawful uthority. Charles maintained that the House of Commons on its own could not try anybody, and so he refused to plead. The court challenged the doctrine of sovereign immunity

Sovereign immunity, or crown immunity, is a legal doctrine whereby a sovereign or state cannot commit a legal wrong and is immune from civil suit or criminal prosecution, strictly speaking in modern texts in its own courts. A similar, stronger ...

and proposed that "the King of England was not a person, but an office whose every occupant was entrusted with a limited power to govern 'by and according to the laws of the land and not otherwise'."

The court proceeded as if the king had pleaded guilty (''pro confesso''), rather than subjecting Charles to the ''peine forte et dure

' (Law French for "hard and forceful punishment") was a method of torture formerly used in the common law legal system, in which a defendant who refused to plead ("stood mute") would be subjected to having heavier and heavier stones placed upon ...

'', that is, pressing with stones, as was standard practice in case of a refusal to plead. However, witnesses were heard by the judges for "the further and clearer satisfaction of their own judgement and consciences".

Thirty witnesses were summoned, but some were later excused. The evidence was heard in the Painted Chamber

The Painted Chamber was part of the medieval Palace of Westminster. It was gutted by fire in 1834, and has been described as "perhaps the greatest artistic treasure lost in the fire". The room was re-roofed and re-furnished to be used tempora ...

rather than Westminster Hall. King Charles was not present to hear the evidence against him and he had no opportunity to question witnesses.

The King was declared guilty at a public session on Saturday 27 January 1649 and sentenced to death. His sentence read: "That the court being satisfied that he, Charles Stuart, was guilty of the crimes of which he had been accused, did judge him tyrant, traitor, murderer, and public enemy to the good people of the nation, to be put to death by the severing of his head from his body." To show their agreement with the sentence, all of the 67 Commissioners who were present rose to their feet. During the rest of that day and on the following day, signatures were collected for his death warrant. This was eventually signed by 59 of the Commissioners, including two who had not been present when the sentence was passed.. House of Lords Record Office.

Execution

King Charles was beheaded in front of theBanqueting House

In English architecture, mainly from the Tudor period onwards, a banqueting house is a separate pavilion-like building reached through the gardens from the main residence, whose use is purely for entertaining, especially eating. Or it may be b ...

of the Palace of Whitehall on 30 January 1649. He declared that he had desired the liberty and freedom of the people as much as any;

but I must tell you that their liberty and freedom consists in having government. ... It is not their having a share in the government; that is nothing appertaining unto them. A subject and a sovereign are clean different things.Francis Allen arranged payments and prepared accounts for the execution event.

Aftermath

Following the execution of Charles I, there was further large-scale fighting inIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, Γire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a Anglo-Scottish border, border with England to the southeast ...

and England, known collectively as the Third English Civil War

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1β60 of a ''second'', or 1β3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* H ...

. A year and a half after the execution, Prince Charles was proclaimed King Charles II by the Scots and he led an invasion of England where he was defeated at the Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 in and around the city of Worcester, England and was the last major battle of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Parliamentarian army of around 28,000 under Oliver Cromwell d ...

. This marked the end of the civil wars.

The High Court of Justice during the Interregnum

The name continued to be used during the interregnum (the period from the execution of Charles I until the restoration). James Earl of Cambridge was tried and executed on 9 March 1649 by the 'High Court of Justice'. In subsequent years the High Court of Justice was reconstituted under the following Acts, all voided upon the Restoration since they did not receive royal assent: * 26 March 1650: An Act for Establishing an High Court of Justice * 27 August 1650: An Act giving further Power to the High Court of Justice * 10 December 1650: An Act for Establishing an High Court of Justice within the Counties of Norfolk, Suffolk, Huntington, Cambridge, Lincoln, and the Counties of the Cities of Norwich and Lincoln, and within the Isle of Ely. * 21 November 1653: An Act For The Establishing An High Court of Justice. On 30 June 1654,John Gerard

John Gerard (also John Gerarde, c. 1545β1612) was an English herbalist with a large garden in Holborn, now part of London. His 1,484-page illustrated ''Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes'', first published in 1597, became a popular gard ...

and Peter Vowell were tried for high treason by the High Court of Justice sitting in Westminster Hall. They had planned to assassinate the Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell and restore Charles II as king. The plotters were found guilty and executed.

The restoration and beyond

After the Restoration in 1660, all who had been active in the court that had tried and sentenced Charles I were targets for the new king. Most of those who were still alive attempted to flee the country. Many fled to the Continent while several of the regicides were sheltered by leaders ofNew Haven Colony

The New Haven Colony was a small English colony in North America from 1638 to 1664 primarily in parts of what is now the state of Connecticut, but also with outposts in modern-day New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

The history of ...

. With the exception of the repentant and eventually pardoned Richard Ingoldsby

Colonel Sir Richard Ingoldsby (10 August 1617 β 9 September 1685) was an English officer in the New Model Army during the English Civil War and a politician who sat in the House of Commons variously between 1647 and 1685. As a Commissione ...

, all those that were captured were executed or sentenced to life imprisonment.

The charges against the king were echoed in the American colonists against George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

a century later, that the king had been "trusted with a limited power to govern by and according to the laws of the land, and not otherwise; and by his trust, oath, and office, being obliged to use the power committed to him for the good and benefit of the people, and for the preservation of their rights and liberties; yet, nevertheless, out of a wicked design to erect and uphold in himself an unlimited and tyrannical power to rule according to his will, and to overthrow the rights and liberties of the people..."

References

* * The Hon Justice Michael Kirby AC CMGThe trial of King Charles I – defining moment for our constitutional liberties

', to the Anglo-Australasian Lawyers' association, on 22 January 1999. * February 1649 An Act to prevent the printing of any the Proceedings in the High Court of Justice, Erected for Trying of James Earl of Cambridge, and others, Without leave of the House of Commons, or the said Court

British History online

Further reading

Trial of King Charles I - UK Parliament Living Heritage

Full text of the Ordinance that established the court

* Victor Louis Stater. ''The Political History of Tudor and Stuart England''

p. 144

Charges against Charles I * T. B Howell, T.B. ''A Complete Collection of State Trials and Proceedings for High Treason other crimes and misdemeanors from the earliest period until the year 1783'' Volume 12 of 21 Charles I to Charles II:

The Trial of Charles Stuart, King of England; Before the High court of Justice, for High Treason

* ttps://quod.lib.umich.edu/e/eebo/A82426.0001.001/1:1?rgn=div1;view=fulltext Full text of the Act abolishing the Office of King, 17 March, 1649* Geoffrey Robertson, ''The Tyrannicide Brief'' (2005), Chatto & Windus

Contemporary London Gazette report on the trial and execution of Charles I

Footnotes

{{reflistEnglish Civil War

The English Civil War (1642β1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

Trials in London

17th century in London

1649 in law

1649 establishments in England

Charles I of England

Treason trials