Hideyo Noguchi on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

, also known as , was a prominent Japanese

/ref> was born to a family of farmers for generations in In 1883, Noguchi entered Mitsuwa elementary school. Thanks to generous contributions from his teacher Kobayashi and his friends, he was able to receive surgery on his badly burned hand. He recovered about 70% mobility and functionality in his left hand through the operation.

Noguchi decided to become a doctor to help those in need. He apprenticed himself to , the same doctor who had performed the surgery. He entered Saisei Gakusha, which later became

In 1883, Noguchi entered Mitsuwa elementary school. Thanks to generous contributions from his teacher Kobayashi and his friends, he was able to receive surgery on his badly burned hand. He recovered about 70% mobility and functionality in his left hand through the operation.

Noguchi decided to become a doctor to help those in need. He apprenticed himself to , the same doctor who had performed the surgery. He entered Saisei Gakusha, which later became

Hideyo Noguchi's Research on Yellow Fever (1918-1928) In The Pre-Electron Microscope Era

" ''Kitasato Arch. of Exp. Med.'', 62.1 (1989), pp.1-9 It turned out he had confused yellow fever with leptospirosis. The vaccine he developed against "yellow fever" was successfully used to treat the latter disease.

While Noguchi was influential during his lifetime, later research was not able to reproduce many of his claims, including having discovered the causes of polio, rabies, syphilis, trachoma, and yellow fever. His finding that ''Noguchia granulosis'' causes trachoma was questioned within a year of his death, and overturned shortly thereafter. His identification of the rabies pathogen was wrong, because the medium he invented to cultivate bacteria was seriously prone to contamination. A fellow Rockefeller Institute researcher said that Noguchi "knew nothing about the pathology of yellow fever" and criticized him for being unwilling to issue retractions for false claims, saying, "I don't think that Noguchi was an honest scientist". Noguchi's failures have often been attributed to his tendency to work in isolation without the skeptical eye of fellow researchers. What are considered flaws in the Rockefeller Institute's system of peer review is also a frequent subject of criticism.

Noguchi's most famous contribution is his identification of the causative agent of syphilis (the bacteria ''Treponema pallidum'') in the brain tissues of patients with partial paralysis due to meningoencephalitis. Other lasting contributions include the use of snake venom in serums, the identification of the leishmaniasis pathogen and of Carrion's disease with Oroya fever. His claim to have grown a culture of syphilis is considered irreproducible.

While Noguchi was influential during his lifetime, later research was not able to reproduce many of his claims, including having discovered the causes of polio, rabies, syphilis, trachoma, and yellow fever. His finding that ''Noguchia granulosis'' causes trachoma was questioned within a year of his death, and overturned shortly thereafter. His identification of the rabies pathogen was wrong, because the medium he invented to cultivate bacteria was seriously prone to contamination. A fellow Rockefeller Institute researcher said that Noguchi "knew nothing about the pathology of yellow fever" and criticized him for being unwilling to issue retractions for false claims, saying, "I don't think that Noguchi was an honest scientist". Noguchi's failures have often been attributed to his tendency to work in isolation without the skeptical eye of fellow researchers. What are considered flaws in the Rockefeller Institute's system of peer review is also a frequent subject of criticism.

Noguchi's most famous contribution is his identification of the causative agent of syphilis (the bacteria ''Treponema pallidum'') in the brain tissues of patients with partial paralysis due to meningoencephalitis. Other lasting contributions include the use of snake venom in serums, the identification of the leishmaniasis pathogen and of Carrion's disease with Oroya fever. His claim to have grown a culture of syphilis is considered irreproducible.

''The Action of Snake Venom Upon Cold-blooded Animals.''

:::Washington, D.C.:

''Snake Venoms: An Investigation of Venomous Snakes with Special Reference to the Phenomena of Their Venoms.''

:::Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution. CLC 14796920* 1911:

''Serum Diagnosis of Syphilis and the Butyric Acid Test for Syphilis.''

:::Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. CLC 3201239* 1923:

''Laboratory Diagnosis of Syphilis: A Manual for Students and Physicians.''

:::New York: P. B. Hoeber. CLC 14783533

''Time.'' May 18, 1931. When Noguchi was awarded an honorary doctorate at Yale,

''New York Times.'' June 23, 1921. *

Noguchi & Latin America

/ref> *

Noguchi's remains were returned to the United States and buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in

Noguchi's remains were returned to the United States and buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in

Centro de Investigaciones Regionales Dr. Hideyo Noguchi

at the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. A 2.1 km street in

The Japanese Government established the

The Japanese Government established the

Noguchi, life events

The Prize is expected to be awarded every five years. The prize has been made possible through a combination of government funding and private donations.

''Yomiuri Shimbun'' (Tokyo). March 30, 2008.

''Taller Than Bandai Mountain: The Story of Hideyo Noguchi.''

New York:

''Maverick's Progress.''

New York:

''Dr. Noguchi's Journey: A Life of Medical Search and Discovery''

(tr., Peter Durfee). Tokyo: Kodansha. (cloth) * * * Lederer, Susan E. ''Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995/1997 paperback * * * * * * Sri Kantha, S. "Hideyo Noguchi's research on yellow fever (1918–1928) in the pre-electron microscopic era", ''Kitasato Archives of Experimental Medicine'', April 1989; 62(1): 1–9. * * * *

Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Legon

* Japanese Government Internet TV

* Fukushima Prefecture

* Cabinet Office,

Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize

* Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS)

* National Diet Library

NDL portrait

*

Noguchi -- slightly less than 90% name recognition amongst primary school students in Japan

2008. {{DEFAULTSORT:Noguchi, Hideyo 1876 births 1928 deaths People from Fukushima Prefecture Japanese expatriates in the United States Japanese bacteriologists Japanese microbiologists Ghana–Japan relations People of the Empire of Japan Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun, 2nd class Recipients of the Legion of Honour Laureates of the Imperial Prize Knights of the Order of the Dannebrog Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Order of the Polar Star Deaths from yellow fever Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)

bacteriologist

A bacteriologist is a microbiologist, or similarly trained professional, in bacteriology -- a subdivision of microbiology that studies bacteria, typically pathogenic ones. Bacteriologists are interested in studying and learning about bacteria, ...

who in 1911 discovered the agent of syphilis as the cause of progressive paralytic disease.

Early life

Noguchi Hideyo whose childhood name was Seisaku NoguchiHideyo Noguchi/ref> was born to a family of farmers for generations in

Inawashiro

is a town located in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. , the town had an estimated population of 13,810 in 5309 households, and a population density of 35 persons per km². The total area of the town was . It is noted as the birthplace of the famous ...

, Fukushima prefecture in 1876. When he was one and a half years old, he fell into a fireplace and suffered a burn injury on his left hand. There was no doctor in the small village, but one of the men examined the boy. "The fingers of the left hand are mostly gone," he said, "and the left arm, the left foot, and the right hand are burned; I don't know how badly."

In 1883, Noguchi entered Mitsuwa elementary school. Thanks to generous contributions from his teacher Kobayashi and his friends, he was able to receive surgery on his badly burned hand. He recovered about 70% mobility and functionality in his left hand through the operation.

Noguchi decided to become a doctor to help those in need. He apprenticed himself to , the same doctor who had performed the surgery. He entered Saisei Gakusha, which later became

In 1883, Noguchi entered Mitsuwa elementary school. Thanks to generous contributions from his teacher Kobayashi and his friends, he was able to receive surgery on his badly burned hand. He recovered about 70% mobility and functionality in his left hand through the operation.

Noguchi decided to become a doctor to help those in need. He apprenticed himself to , the same doctor who had performed the surgery. He entered Saisei Gakusha, which later became Nippon Medical School

is a private university in Sendagi (), Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

History

In 1876, Tai Hasegawa () established a medical school in Tokyo. At that time, the Japanese government and the Ministry of Education only permitted one medical school: the Un ...

. He passed the examinations to practice medicine when he was twenty years old in 1897. He showed signs of great talent and was supported in his studies by Dr. Morinosuke Chiwaki

was a dentist and the Chairman of the Japan Dental Association.

He was one of the founders of Takayama Dental School (高山歯科医学院), which was later named Tokyo Dental College (東京歯科大学).

He was known as Hideyo Noguchi's pat ...

. In 1898, he changed his first name to Hideyo after reading a Tsubouchi Shōyō novel of college students whose character had the same name—Seisaku—as him. The character in the story was an intelligent medical student like Noguchi but became lazy and ruined his life.

Career

In 1900 Noguchi travelled on the ''America Maru

was the second of three high speed passenger liners built for the Oriential Steamship Company (Tōyō Kisen). Converted into an armed merchantman during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905, she played a crucial role in the Battle of Tsushima. A ...

'' to the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

, where he obtained a job as a research assistant with Dr. Simon Flexner

Simon Flexner, M.D. (March 25, 1863 in Louisville, Kentucky – May 2, 1946) was a physician, scientist, administrator, and professor of experimental pathology at the University of Pennsylvania (1899–1903). He served as the first director ...

at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (also known as Penn or UPenn) is a private research university in Philadelphia. It is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and is ranked among the highest-regarded universitie ...

and later at the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research

The Rockefeller University is a private biomedical research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and provides doctoral and postdoctoral education. It is classified ...

. He thrived in this environment. At this time his work concerned venomous snakes

Venomous snakes are species of the suborder Serpentes that are capable of producing venom, which they use for killing prey, for defense, and to assist with digestion of their prey. The venom is typically delivered by injection using hollow or gr ...

. In part, his move was motivated by difficulties in obtaining a medical position in Japan, as prospective employers were concerned that his hand deformity would discourage potential patients. In a research setting, he did not have a handicap. He and his peers learned from their work and from each other. In this period, a fellow research assistant in Flexner's lab was Frenchman Alexis Carrel

Alexis Carrel (; 28 June 1873 – 5 November 1944) was a French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturing techniques. He invented the first perfusion pump with Charl ...

, who would go on to win a Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1912.

Noguchi's work later attracted the Prize committee's scrutiny. In the 21st century, the Nobel Foundation archives were opened for public inspection and research. Historians found that Noguchi was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, accord ...

: in 1913–1915, 1920, 1921 and 1924–1927. During the 1920s, his work was being increasingly criticized for inaccuracies. In 1921, he was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

.

While working at the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research

The Rockefeller University is a private biomedical research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and provides doctoral and postdoctoral education. It is classified ...

in 1911, he was accused of inoculating orphan children with syphilis in the course of a clinical study. He was acquitted of any wrongdoing at the time but, since the late 20th century, his conduct of the study has come to be considered an early instance of unethical human experimentation

Unethical human experimentation is human experimentation that violates the principles of medical ethics. Such practices have included denying patients the right to informed consent, using pseudoscientific frameworks such as race science, and tortu ...

. At the time, society had not developed a consensus about how to conduct human experimentation and feelings varied about the medical research community. Antivivisectionists linked their concerns for animals with concerns about humans. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children was founded in the late 19th century ''after'' the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

In 1913, Noguchi demonstrated the presence of ''Treponema pallidum

''Treponema pallidum'', formerly known as ''Spirochaeta pallida'', is a spirochaete bacterium with various subspecies that cause the diseases syphilis, bejel (also known as endemic syphilis), and yaws. It is transmitted only among humans. It is ...

'' (syphilitic spirochete) in the brain of a progressive paralysis patient, proving that the spirochete was the cause of the disease. Dr. Noguchi's name is remembered in the binomial attached to another spirochete, ''Leptospira noguchii

''Leptospira noguchii'' is a gram-negative, pathogenic organism named for Japanese bacteriologist Dr. Hideyo Noguchi who named the genus ''Leptospira''.Zuerner, Richard L. "Leptospira." Bergey's Manual of Systemic Bacteriology. 2nd ed. Vol. 4th. ...

''.

In 1918, Noguchi traveled extensively in Central America

Central America ( es, América Central or ) is a subregion of the Americas. Its boundaries are defined as bordering the United States to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. ...

and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the sout ...

working with the International Health Board to conduct research to develop a vaccine

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified.

for yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

, and to research Oroya fever, poliomyelitis and trachoma

Trachoma is an infectious disease caused by bacterium '' Chlamydia trachomatis''. The infection causes a roughening of the inner surface of the eyelids. This roughening can lead to pain in the eyes, breakdown of the outer surface or cornea of ...

. He believed that yellow fever was caused by spirochaete

A spirochaete () or spirochete is a member of the phylum Spirochaetota (), (synonym Spirochaetes) which contains distinctive diderm (double-membrane) gram-negative bacteria, most of which have long, helically coiled (corkscrew-shaped or s ...

bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometr ...

instead of a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsk ...

. He worked for much of the next ten years trying to prove this theory. His work on yellow fever was widely criticized as taking an inaccurate approach that was contradictory to contemporary research, and confusing yellow fever with other pathogens. In 1927-28 three different papers appeared in medical journals that discredited his theories.SS Kantha.Hideyo Noguchi's Research on Yellow Fever (1918-1928) In The Pre-Electron Microscope Era

" ''Kitasato Arch. of Exp. Med.'', 62.1 (1989), pp.1-9 It turned out he had confused yellow fever with leptospirosis. The vaccine he developed against "yellow fever" was successfully used to treat the latter disease.

Human experimentation scandal

In 1911 and 1912 at the Rockefeller Institute in New York City, Noguchi was working to develop a syphilis skin test similar to the tuberculin skin test. The subjects were recruited from clinics and hospitals in New York. In the experiment, Noguchi injected an extract of syphilis, called luetin, under the subjects' upper arm skin. Skin reactions were studied, as they varied among healthy subjects and syphilis patients, based on the disease's stage and its treatment. Of the 571 subjects, 315 had syphilis. The remaining subjects were "controls;" they were orphans or hospital patients who did not have syphilis. The hospital patients were already being treated for various non-syphilitic diseases, such as malaria, leprosy, tuberculosis, and pneumonia. Finally, the controls were normal individuals, mostly children between the ages of 2 and 18 years. Critics at the time, mainly from the anti-vivisectionist movement, noted that Noguchi violated the rights of vulnerable orphans and hospital patients. There was concern on the part of anti-vivisectionists that the children would get syphilis from Noguchi's experiments.Lederer, Susan E. ''Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995/1997 paperback It became a public scandal and the media discussed it. The editor of ''Life

Life is a quality that distinguishes matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for Cell growth, growth, reaction to Stimu ...

'' pointed out:

If the researcher had said to these patients: "Have I your permission to inject into your system a concoction more or less related to a hideous disease?"—the invalids might have declined.In Noguchi's defense, Rockefeller Institute business manager Jerome D. Greene wrote a letter to the anti-

vivisection

Vivisection () is surgery conducted for experimental purposes on a living organism, typically animals with a central nervous system, to view living internal structure. The word is, more broadly, used as a pejorative catch-all term for Animal testi ...

society, which had protested the experiment. Greene pointed out that Noguchi had tested the extract on himself before administering it to subjects, and his fellow researchers had done the same, so it was impossible that the injections could cause syphilis. However, Noguchi himself was diagnosed with untreated syphilis in 1913, for which he refused treatment from Rockefeller Hospital. At the time, Greene's explanation was considered a demonstration of the importance of the studies and care the doctors were taking in research. In May 1912 the New York Society for the Prevention for Cruelty to Children asked the New York district attorney to press charges against Noguchi; he declined.

In the United States, it was not until the late 20th century that sufficient consensus developed about human experimentation to gain passage of laws to protect subjects. Along the way, more protocols were developed about informed consent and rights of patients/subjects.

Death

Following the death of British pathologist Adrian Stokes of yellow fever in September 1927, it became increasingly evident that yellow fever was caused by a virus, not by the bacillus ''Leptospira icteroides'', as Noguchi believed. Feeling his reputation was at stake, Noguchi hastened to Lagos to carry out additional research. However, he found the working conditions in Lagos did not suit him. At the invitation of Dr. William Alexander Young, the young director of the British Medical Research Institute, Accra,Gold Coast

Gold Coast may refer to:

Places Africa

* Gold Coast (region), in West Africa, which was made up of the following colonies, before being established as the independent nation of Ghana:

** Portuguese Gold Coast (Portuguese, 1482–1642)

** Dutch G ...

(modern-day Ghana

Ghana (; tw, Gaana, ee, Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and To ...

), he moved to Accra and made this his base in 1927.

However, Noguchi proved a very difficult guest and by May 1928 Young regretted his invitation. Noguchi was secretive and volatile, working almost entirely at night to avoid contact with fellow researchers. The diaries of Oskar Klotz, another researcher with the Rockefeller Foundation, describe Noguchi's temper and behavior as erratic and bordering on the paranoid. His methods were haphazard.

According to Klotz, he inoculated huge numbers of monkeys with yellow fever, but failed to keep proper records. He may have believed himself immune to yellow fever, having been inoculated with a vaccine of his own development. Possibly his erratic and irresponsible behavior was caused by the untreated syphilis with which he was diagnosed in 1913, and which may have progressed to neurosyphilis

Neurosyphilis refers to infection of the central nervous system in a patient with syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been reported in HIV-infected patients. Meningitis is the most common neurologic ...

.

Despite repeated promises to Young, Noguchi failed to keep infected mosquitoes in their specially designed secure housing. In May 1928, having failed to find evidence for his theories, Noguchi was set to return to New York, but was taken ill in Lagos.

He boarded his ship to sail home, but on 12 May was put ashore at Accra and taken to a hospital with yellow fever. After lingering for some days, he died on 21 May.

In a letter home, Young states, "He died suddenly noon Monday. I saw him Sunday afternoon – he smiled – and amongst other things, said, “Are you sure you are quite well?" "Quite." I said, and then he said "I don’t understand."

Seven days later, despite exhaustive sterilisation of the site and most particularly of Noguchi's laboratory, Young himself died of yellow fever.

Legacy

Selected works

* 1904:''The Action of Snake Venom Upon Cold-blooded Animals.''

:::Washington, D.C.:

Carnegie Institution

The Carnegie Institution of Washington (the organization's legal name), known also for public purposes as the Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), is an organization in the United States established to fund and perform scientific research. T ...

. CLC 2377892* 1909: ''Snake Venoms: An Investigation of Venomous Snakes with Special Reference to the Phenomena of Their Venoms.''

:::Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution. CLC 14796920* 1911:

''Serum Diagnosis of Syphilis and the Butyric Acid Test for Syphilis.''

:::Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. CLC 3201239* 1923:

''Laboratory Diagnosis of Syphilis: A Manual for Students and Physicians.''

:::New York: P. B. Hoeber. CLC 14783533

Honors during Noguchi's lifetime

Noguchi was honored with Japanese and foreign decorations. He received honorary degrees from a number of universities. He was self-effacing in his public life, and he often referred to himself as "funny Noguchi." Those who knew him well said that he "gloated in honors.""Funny Noguchi,"''Time.'' May 18, 1931. When Noguchi was awarded an honorary doctorate at Yale,

William Lyon Phelps

William Lyon Phelps (January 2, 1865 New Haven, Connecticut – August 21, 1943 New Haven, Connecticut) was an American author, critic and scholar. He taught the first American university course on the modern novel. He had a radio show, wrote ...

observed that the kings of Spain, Denmark and Sweden had conferred awards, but "perhaps he appreciates even more than royal honors the admiration and the gratitude of the people." "Angll Inaugurated at Yale Graduation; New President Takes Office Before a Distinguished Audience of University Men; 784 Degrees are given; Mme. Curie, Sir Robert Jones, Archibald Marshall, J.W. Davis and Others Honored,"''New York Times.'' June 23, 1921. *

Kyoto Imperial University

, mottoeng = Freedom of academic culture

, established =

, type = Public (National)

, endowment = ¥ 316 billion (2.4 billion USD)

, faculty = 3,480 (Teaching Staff)

, administrative_staff = 3,978 (Total Staff)

, students = ...

, Doctor of Medicine

Doctor of Medicine (abbreviated M.D., from the Latin ''Medicinae Doctor'') is a medical degree, the meaning of which varies between different jurisdictions. In the United States, and some other countries, the M.D. denotes a professional degree. T ...

, 1909.

* Knight of the Order of Dannebrog

The Order of the Dannebrog ( da, Dannebrogordenen) is a Danish order of chivalry instituted in 1671 by Christian V. Until 1808, membership in the order was limited to fifty members of noble or royal rank, who formed a single class known ...

, 1913 (Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establish ...

).

* Commander of the Order of Isabella the Catholic

The Order of Isabella the Catholic ( es, Orden de Isabel la Católica) is a Spanish civil order and honor granted to persons and institutions in recognition of extraordinary services to the homeland or the promotion of international relations a ...

, 1913 (Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

).

* Commander of the Order of the Polar Star

The Royal Order of the Polar Star ( Swedish: ''Kungliga Nordstjärneorden'') is a Swedish order of chivalry created by King Frederick I on 23 February 1748, together with the Order of the Sword and the Order of the Seraphim.

The Order of t ...

, 1914 ( Sweden).Kita, p. 182.

* Tokyo Imperial University

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

, Doctor of Science

Doctor of Science ( la, links=no, Scientiae Doctor), usually abbreviated Sc.D., D.Sc., S.D., or D.S., is an academic research degree awarded in a number of countries throughout the world. In some countries, "Doctor of Science" is the degree used f ...

, 1914.

* Order of the Rising Sun, Gold Rays with Rosette, 1915.

* Imperial Award, Imperial Academy (Japan), 1915.

* Central University of Ecuador, 1919, (Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

).Japan, Ministry of Foreign AffairsNoguchi & Latin America

/ref> *

National University of San Marcos

The National University of San Marcos ( es, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, link=no, UNMSM) is a public research university located in Lima, the capital of Peru. It is considered the most important, recognized and representative educ ...

, 1920, (Peru)

* Medicine School of Merida, "Doctor ''Honoris Causa'' en Medicina y Cirugía", 1920 (México)

* University of Guayaquil, 1919, Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ' ...

.

* Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Sta ...

, 1921, (United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territori ...

).

* Knight of the Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour (french: Ordre national de la Légion d'honneur), formerly the Royal Order of the Legion of Honour ('), is the highest French order of merit, both military and civil. Established in 1802 by Napoleon ...

of France, 1924Japanese Wikipedia

* Senior fifth rank in the order of precedence, Japanese government, 1925

Posthumous honors

Noguchi's remains were returned to the United States and buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in

Noguchi's remains were returned to the United States and buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New Y ...

, New York City.

In 1928, the Japanese government awarded Noguchi the Order of the Rising Sun, Gold and Silver Star, which represents the second highest of eight classes associated with the award.

In 1979, the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research (NMIMR) was founded with funds donated by the Japanese government at the University of Ghana

The University of Ghana is a public university located in Accra, Ghana. It the oldest and largest of the thirteen Ghanaian national public universities.

The university was founded in 1948 as the University College of the Gold Coast in the Br ...

in Legon, a suburb north of Accra.

In 1981, the Instituto Nacional de Salud Mental (National Institute of Mental Health) "Honorio Delgado - Hideyo Noguchi" was founded with founds of the Peruvian Government and the JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) in Lima - Perú.

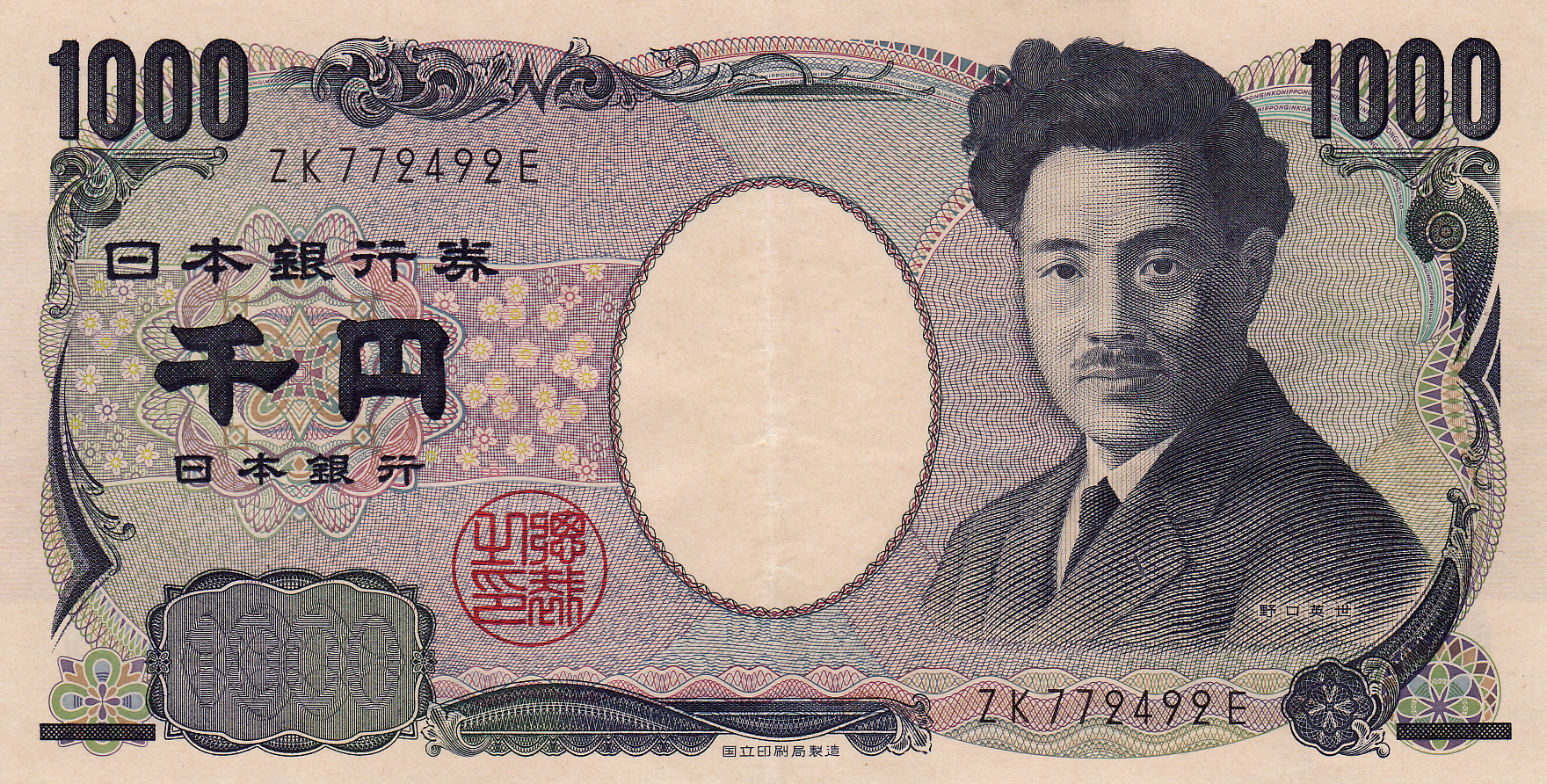

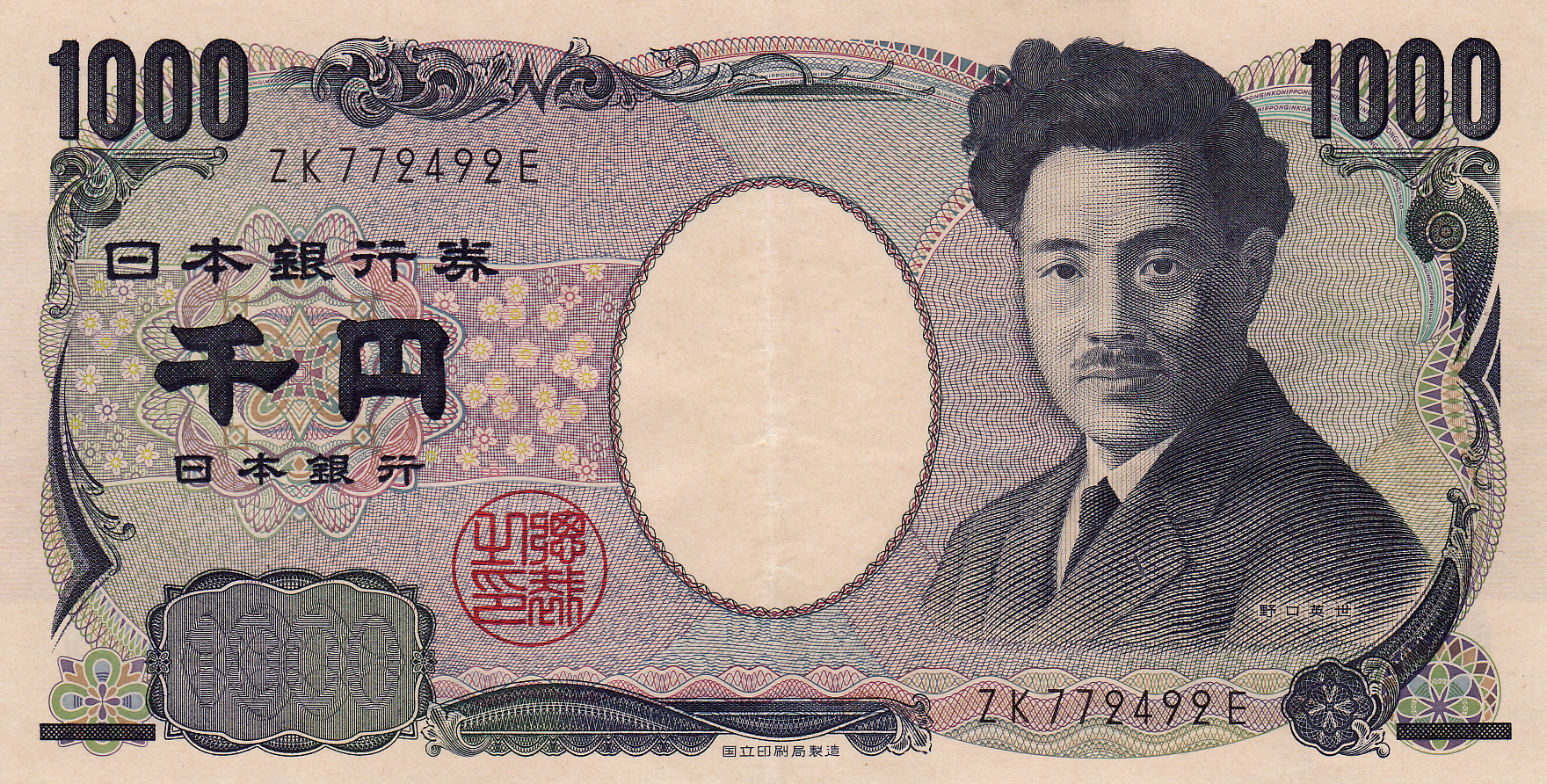

Dr. Noguchi's portrait has been printed on Japanese 1000-yen

The is the official currency of Japan. It is the third-most traded currency in the foreign exchange market, after the United States dollar (US$) and the euro. It is also widely used as a third reserve currency after the US dollar and the e ...

banknotes

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

since 2004. In addition, the house near Inawashiro where he was born and brought up is preserved. It is operated as part of a museum to his life and achievements.

Noguchi's name is honored at thCentro de Investigaciones Regionales Dr. Hideyo Noguchi

at the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. A 2.1 km street in

Guayaquil, Ecuador

, motto = Por Guayaquil Independiente en, For Independent Guayaquil

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Ecuador#South America

, pushpin_re ...

downtown is named after Dr. Hideyo Noguchi.

Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize

Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize The honors men and women "with outstanding achievements in the fields of medical research and medical services to combat infectious and other diseases in Africa, thus contributing to the health and welfare of the African people and of all humankind ...

in July 2006 as a new international medical research and services award to mark the official visit by Prime Minister Jun'ichirō Koizumi to Africa in May 2006 and the 80th anniversary of Dr. Noguchi's death. The Prize is awarded to individuals with outstanding achievements in combating various infectious diseases in Africa or in establishing innovative medical service systems. The presentation ceremony and laureate lectures coincided with the Fourth Tokyo International Conference on African Development in late April 2008. In 2009, the conference venue was moved from Tokyo to Yokohama as another way of honoring the man after whom the prize was named. In 1899, Dr. Noguchi worked at the Yokohama Port Quarantine Office as an assistant quarantine doctor.Hideyo Noguchi Memorial MuseumNoguchi, life events

The Prize is expected to be awarded every five years. The prize has been made possible through a combination of government funding and private donations.

''Yomiuri Shimbun'' (Tokyo). March 30, 2008.

See also

*List of medicine awards

This list of medicine awards is an index to articles about notable awards for contributions to medicine, the science and practice of establishing the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and prevention of disease. The list is organized by region and ...

* Max Theiler

Max Theiler (30 January 1899 – 11 August 1972) was a South African-American virologist and physician. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1951 for developing a vaccine against yellow fever in 1937, becoming the first ...

- completed Noguchi's work, yellow fever vaccine (1926)

* Human experimentation in the United States

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') are the most abundant and widespread species of primate, characterized by bipedalism and exceptional cognitive skills due to a large and complex brain. This has enabled the development of advanced tools, culture, a ...

* '' Tōki Rakujitsu'' - Japanese film

Notes

References

* * * D'Amelio, Dan''Taller Than Bandai Mountain: The Story of Hideyo Noguchi.''

New York:

Viking Press

Viking Press (formally Viking Penguin, also listed as Viking Books) is an American publishing company owned by Penguin Random House. It was founded in New York City on March 1, 1925, by Harold K. Guinzburg and George S. Oppenheim and then acquir ...

. (cloth) CLC 440466*

* Flexner, James Thomas. (1996)''Maverick's Progress.''

New York:

Fordham University Press

The Fordham University Press is a publishing house, a division of Fordham University, that publishes primarily in the humanities and the social sciences. Fordham University Press was established in 1907 and is headquartered at the university's Li ...

. (cloth)

*

*

* Kita, Atsushi. (2005)''Dr. Noguchi's Journey: A Life of Medical Search and Discovery''

(tr., Peter Durfee). Tokyo: Kodansha. (cloth) * * * Lederer, Susan E. ''Subjected to Science: Human Experimentation in America before the Second World War'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995/1997 paperback * * * * * * Sri Kantha, S. "Hideyo Noguchi's research on yellow fever (1918–1928) in the pre-electron microscopic era", ''Kitasato Archives of Experimental Medicine'', April 1989; 62(1): 1–9. * * * *

External links

Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Legon

* Japanese Government Internet TV

* Fukushima Prefecture

* Cabinet Office,

Government of Japan

The Government of Japan consists of legislative, executive and judiciary branches and is based on popular sovereignty. The Government runs under the framework established by the Constitution of Japan, adopted in 1947. It is a unitary stat ...

Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize

* Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS)

* National Diet Library

NDL portrait

*

Yomiuri Shimbun

The (lit. ''Reading-selling Newspaper'' or ''Selling by Reading Newspaper'') is a Japanese newspaper published in Tokyo, Osaka, Fukuoka, and other major Japanese cities. It is one of the five major newspapers in Japan; the other four are ...

Noguchi -- slightly less than 90% name recognition amongst primary school students in Japan

2008. {{DEFAULTSORT:Noguchi, Hideyo 1876 births 1928 deaths People from Fukushima Prefecture Japanese expatriates in the United States Japanese bacteriologists Japanese microbiologists Ghana–Japan relations People of the Empire of Japan Recipients of the Order of the Rising Sun, 2nd class Recipients of the Legion of Honour Laureates of the Imperial Prize Knights of the Order of the Dannebrog Knights Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic Order of the Polar Star Deaths from yellow fever Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York)