Hesselberg (; 689 m above sea level) is the highest point in

Middle Franconia

Middle Franconia (german: Mittelfranken, ) is one of the three administrative regions of Franconia in Bavaria, Germany. It is located in the west of Bavaria and borders the state of Baden-Württemberg. The administrative seat is Ansbach; however ...

and the

Franconian Jura

The Franconian Jura ( , , or ) is an upland in Franconia, Bavaria, Germany. Located between two rivers, the Danube in the south and the Main in the north, its peaks reach elevations of up to and it has an area of some 7053.8 km2. Emil Meyn ...

and is situated 60 km south west of

Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

, Germany. The mountain stands isolated and far from the center of the Franconian Jura, in its southwestern border region, 4 km to the north west of

Wassertrüdingen. The mountain's first recorded name was ''Öselberg'', which probably derived from ''öder Berg'' (bleak mountain). This name later changed to ''Eselsberg'' and finally to the current name ''Hesselberg''. As a

butte

__NOTOC__

In geomorphology, a butte () is an isolated hill with steep, often vertical sides and a small, relatively flat top; buttes are smaller landforms than mesas, plateaus, and tablelands. The word ''butte'' comes from a French word me ...

the mountain provides an insight into

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

geology. It has also witnessed an eventful history, many incidents were handed down from generation to generation and these mixed with facts have become legends. Nowadays many people visit Hesselberg in order to enjoy nature and the wonderful vista. When the weather is clear the

Alps

The Alps () ; german: Alpen ; it, Alpi ; rm, Alps ; sl, Alpe . are the highest and most extensive mountain range system that lies entirely in Europe, stretching approximately across seven Alpine countries (from west to east): France, Swi ...

150 km away can be seen.

Shape, location, and dimension

The mountain has a length of approximately 6 km and an average width of 1 to 2 km. All of its slopes except for those on the southern side are covered with

coniferous or

mixed forest

Temperate broadleaf and mixed forest is a temperate climate terrestrial habitat type defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature, with broadleaf tree ecoregions, and with conifer and broadleaf tree mixed coniferous forest ecoregions.

These fo ...

. On the upper slopes, and especially on the eastern slope of the ''Röckinger mountain'', there are large areas of

deciduous forest

In the fields of horticulture and Botany, the term ''deciduous'' () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, ...

. The upper part of the prominent southern side is free of forest. On the southern and north-eastern slopes there are large areas of neglected grassland with their typical

juniper bushes. Hesselberg can be divided into 5 sections along its center-line (see panorama image).

* On the western slope there is mainly coniferous forest. This is the starting point for the geological

nature trail.

* The western

plateau

In geology and physical geography, a plateau (; ; ), also called a high plain or a tableland, is an area of a highland consisting of flat terrain that is raised sharply above the surrounding area on at least one side. Often one or more sides ...

, also called ''Gerolfinger mountain'', has an especially unspoilt appearance with its

sinkhole

A sinkhole is a depression or hole in the ground caused by some form of collapse of the surface layer. The term is sometimes used to refer to doline, enclosed depressions that are locally also known as ''vrtače'' and shakeholes, and to openi ...

-like depressions,

hedges and

shrubs. The depressions were, however, not formed naturally, they are the result of

mining

Mining is the extraction of valuable minerals or other geological materials from the Earth, usually from an ore body, lode, vein, seam, reef, or placer deposit. The exploitation of these deposits for raw material is based on the economic ...

of material for road construction and lime burning.

* Since 1994 the central part, known as ''Ehinger mountain'', with the main peak and the transmitter tower has been accessible again; previously there was a restricted military area of the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land warfare, land military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight Uniformed services of the United States, U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army o ...

here.

* The woodless eastern plateau, which is called ''Osterwiese'' or ''Röckinger mountain'' is the most important area for tourism. This section serves as a launching zone for

model planes and

hang-gliders and as an observation platform. On especially clear days one can see the

Zugspitze

The Zugspitze (), at above sea level, is the highest peak of the Wetterstein Mountains as well as the highest mountain in Germany. It lies south of the town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen, and the Austria–Germany border runs over its western su ...

in the Alps can be seen.

* The highly afforested eastern foothill, known for its legends, has the name ''Schlössleinsbuck''. This small hill top is also called ''Small Hesselberg''. The ''Röckinger mountain'' and the ''Schlössleinsbuck'' are separated by the ''

Druid's valley''.

Origin and geological structure

Hesselberg is amongst the most important

geotopes in

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

. On September 24, 2005 it was awarded the cachet ''Bayerns schönste Geotope'' (Bavarian's most beautiful geotopes) by Georg Schlapp (director of the Bavarian Environmental Protection Office) in the course of a ceremony.

Jurassic origin

200 million years ago the

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately Mya. The Jurassic constitutes the middle period of ...

sea extended from the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea, epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the ...

basin far to the South and covered the

late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch of the Triassic Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch and followed by the Early Jurassic Epoch. ...

land. At that time the Hesselberg region was on the border of that sea. Many

affluxes brought huge masses of

rubble

Rubble is broken stone, of irregular size, shape and texture; undressed especially as a filling-in. Rubble naturally found in the soil is known also as 'brash' (compare cornbrash)."Rubble" def. 2., "Brash n. 2. def. 1. ''Oxford English Dictionar ...

from the eastern mainland and formed a multilayer seafloor, which had a rich

flora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous (ecology), indigenous) native plant, native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' ...

and

fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is ''funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as ''Biota (ecology ...

. During more than 40 million years the different layers of Jurassic rock consecutively deposited: the

Black Jurassic

The Black Jurassic or Black Jura (german: Schwarzer Jura) in earth history refers to the lowest of the three lithostratigraphic units of the South German Jurassic, the latter being understood not as a geographical, but a geological term in the ...

at the bottom, the

Brown Jurassic

The Brown Jurassic or Brown Jura (german: Brauner Jura or ''Braunjura'') in earth history refers to the middle of the three lithostratigraphic units of the South German Jurassic, the latter being understood not as a geographical, but a geological ...

above, and the

White Jurassic at the top. Each of these layers is characterised by the typical rock and embedded

fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s that are specific for each era. Because certain fossils are solely found in certain layers, they are referred to as

index fossil

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. “Biostratigraphy.” ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of Bio ...

s. In Jurassic rock

ammonites are the index fossils. In the course of time the Jurassic sea silted up completely. Because during the Early Jurassic Hesselberg was located in a sheltered basin it was not as eroded by wind and water as the plain between the mountain and the

Hahnenkamm. The hard rock resisted erosion and left Hesselberg as a distinctive

Zeugenberg rising above the landscape like an island. This kind of mountain-formation is known as

inverted relief

Inverted relief, inverted topography, or topographic inversion refers to landscape features that have reversed their elevation relative to other features. It most often occurs when low areas of a landscape become filled with lava or sediment th ...

.

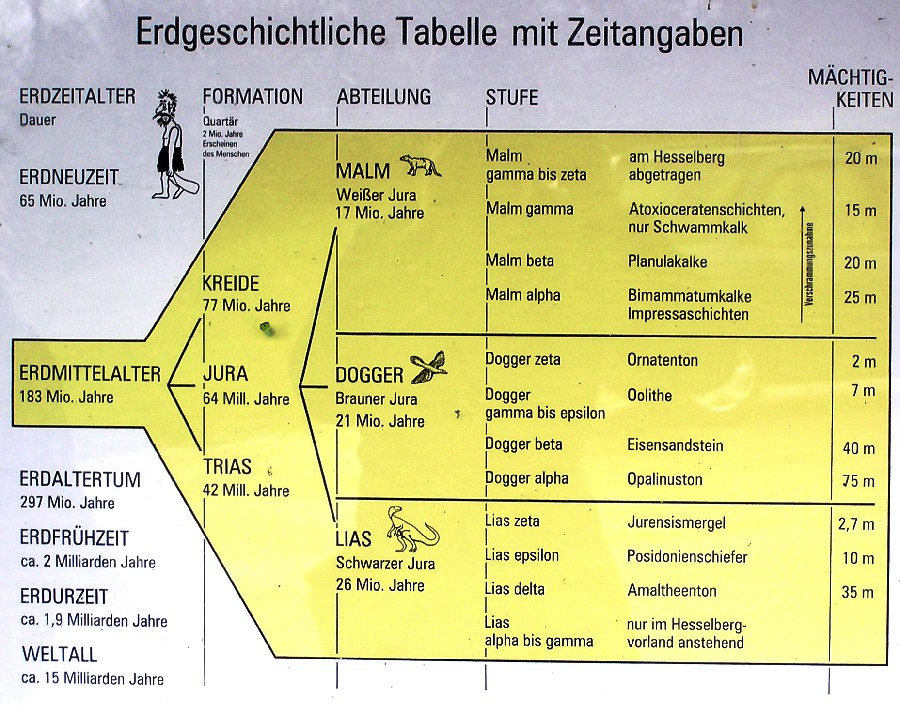

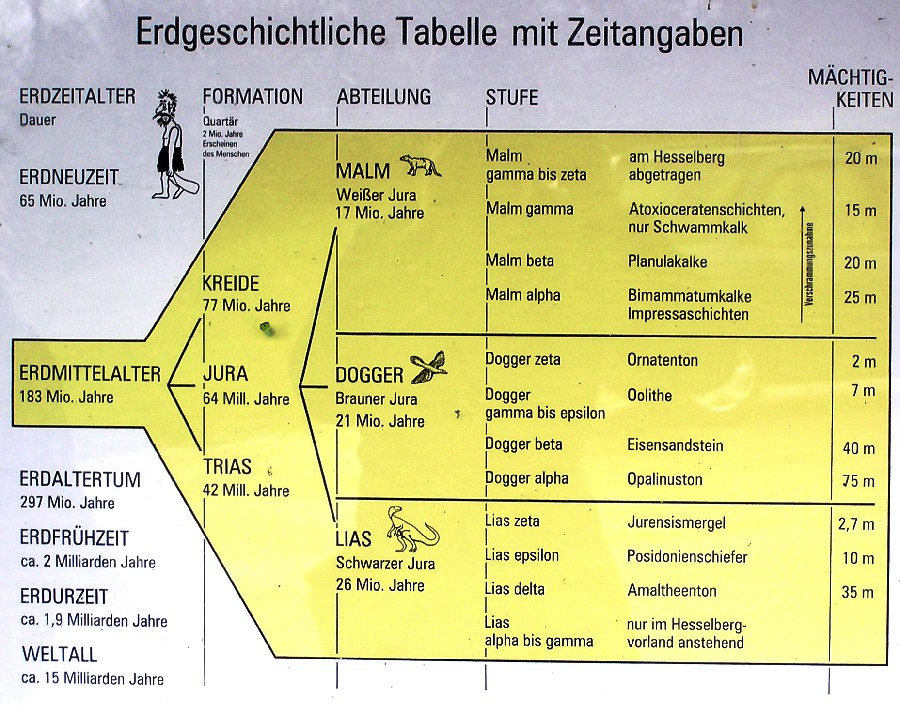

Rock layers of the mountain

There is a geological nature trail on the mountain with signs that describe its origin. Each of the three main parts of the Jurassic era is divided into six sub-divisions, which are numbered with

Greek letters

The Greek alphabet has been used to write the Greek language since the late 9th or early 8th century BCE. It is derived from the earlier Phoenician alphabet, and was the earliest known alphabetic script to have distinct letters for vowels as we ...

alpha to

zeta

Zeta (, ; uppercase Ζ, lowercase ζ; grc, ζῆτα, el, ζήτα, label= Demotic Greek, classical or ''zē̂ta''; ''zíta'') is the sixth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 7. It was derived f ...

(

Quenstedt's classification). The rocks that are found in the different layers are assigned to this classification.

Early Jurassic (Lias) layers

The

Black Jurassic

The Black Jurassic or Black Jura (german: Schwarzer Jura) in earth history refers to the lowest of the three lithostratigraphic units of the South German Jurassic, the latter being understood not as a geographical, but a geological term in the ...

is so called due to the dark colours of

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

and

marl characteristic of this era. This layer is approximately 50 m thick and forms the fertile hilly area around the mountain. Its lowest sub-layers (Lias alpha to gamma) are beneath the surface. The

Amaltheenton (Lias delta) at 35 m is the thickest sub-layer of the Lias. A special feature is the Posidonia

schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock showing pronounced schistosity. This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a low-power hand lens, oriented in such a way that the rock is easily split into thin flakes ...

(Lias epsilon), which is 10 m thick. In this sub-layer fossils from larger animals are also found such as

ichthyosaurs. The cavity of the Posidonia schist, which is at the starting point of the nature trail, is a unique natural geological monument where it is prohibited to search for and to collect fossils. Above these well visible schist layers lies the Jurassic marl (Lias zeta), which is 2.7 m thick.

Middle Jurassic (Dogger) layers

The dark brown colours of the

weathered upper layers give the name to the Brown (or Middle) Jurassic. The colours are a result of highly concentrated

iron

Iron () is a chemical element with Symbol (chemistry), symbol Fe (from la, Wikt:ferrum, ferrum) and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 element, group 8 of the periodic table. It is, Abundanc ...

. The layer of the Dogger which is 135 m thick forms the main part of Hesselberg's slopes. The lowest sub-layer (Dogger alpha) is formed of 75 m thick Opalinus-clay. The soil of these layers is very susceptible to landslides which has resulted in the unevenness of the meadows. On top of the Opalinus-clay lies a layer of iron

sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

(Dogger beta), which is 40 m thick. This layer is very distinctive due to its steep rise. Because the Opalinus-clay layer is impervious to water, a

spring horizon has formed at the transition to the iron sandstone. The layers of Dogger gamma (Sowerbyi layers) (1 m), Dogger delta (

Ostreen-lime) (4 m), and Dogger epsilon (

Oolith-lime) (2 m) are summarised under the term "ooliths". These layers contain many fossils. On the very top of the Middle Jurassic layers is the Ornate's clay layer (Dogger zeta), which is only 2 m thick. This small layer forms a terrace around the Hesselberg. On its southern side the buildings of the

folk high school

Folk high schools (also ''Adult Education Center'', Danish: ''Folkehøjskole;'' Dutch: ''Volkshogeschool;'' Finnish: ''kansanopisto'' and ''työväenopisto'' or ''kansalaisopisto;'' German: ''Volkshochschule'' and (a few) ''Heimvolkshochschule;' ...

were constructed.

Late Jurassic (Malm) layers

The topmost Jurassic layer is called the White Jurassic due to its light colour. These layers can be up to 400 m thick in the Franconian Jura, but at Hesselberg they are mostly ablated; only 85 m is left. The rocks of the Malm are partly

sediments

Sediment is a naturally occurring material that is broken down by processes of weathering and erosion, and is subsequently transported by the action of wind, water, or ice or by the force of gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundame ...

and partly formed from

reefs

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral or similar relatively stable material, lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic processes—deposition of sand, wave erosion planing down rock out ...

of ancient

sea sponge

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through th ...

s. This rock is widely distributed on the main peak. The light-coloured

lime

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a color between yellow and green

Lime may also refer to:

Botany ...

of the White Jurassic was a popular building material for houses (

burnt lime

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, Caustic (substance), caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "''lime (material), lime''" co ...

) and for road construction (

rubble

Rubble is broken stone, of irregular size, shape and texture; undressed especially as a filling-in. Rubble naturally found in the soil is known also as 'brash' (compare cornbrash)."Rubble" def. 2., "Brash n. 2. def. 1. ''Oxford English Dictionar ...

). The depressions on the western plateau are caused by these excavations. The lowest layers form the

Impressa-layers (low Malm alpha), which are approximately 25 m thick, and the

Bimammatum-lime (high Malm alpha). The old name of the

Planula

A planula is the free-swimming, flattened, ciliated, bilaterally symmetric larval form of various cnidarian species and also in some species of Ctenophores. Some groups of Nemerteans also produce larvae that are very similar to the planula, which ...

-lime (Malm beta) is factory lime, which indicates the use as building material. This layer, which is 15 m thick and interspersed with

sponge reef

Sponge reefs are reefs formed by Hexactinellid sponges, which have a skeleton made of silica, and are often referred to as ''glass sponges''. Such reefs are now very rare, and found only in waters off the coast of British Columbia, Washington ( ...

s, forms the plateau of the ''Osterwiese''. The small

quarry

A quarry is a type of open-pit mine in which dimension stone, rock, construction aggregate, riprap, sand, gravel, or slate is excavated from the ground. The operation of quarries is regulated in some jurisdictions to reduce their envir ...

below the main peak consists of Planula-lime in its lower part, and the

Ataxiocerate's layer (Malm gamma) in its upper, which builds up the main peak and is 20 m thick. The top layer of Malm gamma and the layers of Malm delta to Malm zeta have already been eroded away on Hesselberg.

History of colonisation and important incidents in the Hesselberg region

There are illustrated charts in some of the parking lots of the region which provide an insight into the area's settlement history.

Pre- and early history

Hesselberg was used as a shelter and dwelling in prehistoric times. Archaeological artefacts from the

Stone Age (approx. 10,000–2000

BC) have been found mainly on the ''Osterwiese''. In the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

(approx. 2000–1300 BC) it was constantly settled. In the

Urnfield time (approx. 1200–750 BC) the colony at the plateaus was surrounded with

curtain walls, and

moats. Even today the 5 km long remains of the border walls around the ''Osterwiese'', the ''Ehinger mountain'', and the ''Gerolfinger mountain'' provide an idea of the importance of these fortifications. Behind this sheltering stonework an important political, economic, and religious center evolved. For a long time these constructions were thought to be of

celtic origin, but only one artefact (the weapons of a warrior) from the

La Tène period

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

(500–15 BC) indicates any Celtic involvement. In the restless

Migration Period and during the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

the walls of Hesselberg were used as a shelter and for defensive purposes. The city museum of

Oettingen

Oettingen in Bayern (Swabian: ''Eadi'') is a town in the Donau-Ries district, in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany. It is situated northwest of Donauwörth, and northeast of Nördlingen.

Geography

The town is located on the river Wörnitz, a tributary ...

and the museum for pre- and early history in

Gunzenhausen contains many exhibits such as tools and weapons.

Romans

Under the rules of emperors

Domitian

Domitian (; la, Domitianus; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was a Roman emperor who reigned from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Fl ...

(81–96

AD) and

Hadrian (117–138 AD) the Romans pushed the border of their province

Raetia

Raetia ( ; ; also spelled Rhaetia) was a province of the Roman Empire, named after the Rhaetian people. It bordered on the west with the country of the Helvetii, on the east with Noricum, on the north with Vindelicia, on the south-west ...

farther to the North. They expanded the wall of

Limes

Limes may refer to:

* the plural form of lime (disambiguation)

Lime commonly refers to:

* Lime (fruit), a green citrus fruit

* Lime (material), inorganic materials containing calcium, usually calcium oxide or calcium hydroxide

* Lime (color), a ...

in order to protect against the

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and e ...

and equipped it with many watchtowers, and in the immediate vicinity of Hesselberg large

Castella

is a kind of ''wagashi'' (a Japanese traditional confectionery) originally developed in Japan based on the "Nanban confectionery" (confectionery imported from abroad to Japan during the Azuchi–Momoyama period). The batter is poured into larg ...

were built. Under the rule of emperor

Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname "Caracalla" () was Roman emperor from 198 to 217. He was a member of the Severan dynasty, the elder son of Emperor S ...

(around 213 AD) the last and widest extension of the Limes took place. To the west of the mountain the wall crossed the rivers

Wörnitz and

Sulzach in a north-south direction. A few kilometres to the north of

Wittelshofen it turned eastward. Due to this sharp bend the strategically important Hesselberg was included within the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. There were Castella at

Aufkirchen,

Ruffenhofen,

Dambach, and

Unterschwaningen

Unterschwaningen is a municipality in the district of Ansbach in Bavaria in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia ...

.

Castellum Ruffenhofen was the largest in the Hesselberg area. No Roman buildings have been found by archaeologists on the mountain itself. The remains of the Limes now form stone ridges hidden in the woods. Nowadays most of the civil and military wall remains are hidden beneath the ground of local meadows and fields. On top of Castellum Ruffenhofen a Roman park is built. In the local museum of

Weitlingen there are a few Roman exhibits.

Alamanni and Franks

Around 260 AD

Alamannic and Germanic groups entered the region and destroyed the fortifications of the Limes, the Castelli, and many settlements. The Romans had to shift their borders back to the

Danube

The Danube ( ; ) is a river that was once a long-standing frontier of the Roman Empire and today connects 10 European countries, running through their territories or being a border. Originating in Germany, the Danube flows southeast for , p ...

. The Alamanni founded their first

granges and farmed the land as arable and livestock farmers. As well as the local town names that end with "''-ingen''" the

strip cultivation indicates Alamannic foundation. The villages Röck''ingen'', Eh''ingen'', Gerolf''ingen'', Weilt''ingen'', and Irs''ingen'' have their origins in that period. At the end of the 5th century the

Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

emerged from the lower

Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

valley and initiated the second wave of colonisation. From 496 to 506 and under the rule of

Merovingian

The Merovingian dynasty () was the ruling family of the Franks from the middle of the 5th century until 751. They first appear as "Kings of the Franks" in the Roman army of northern Gaul. By 509 they had united all the Franks and northern Gauli ...

king

Clovis I they defeated the

Swabian Alamanni, who lost their northern territories that had formerly reached into the Neuwieder basin, and they were pushed back behind the

Oos-

Hornisgrinde

The Hornisgrinde, 1,164 m (3,820 ft), is the highest mountain in the Northern Black Forest of Germany. The Hornisgrinde lies in northern Ortenaukreis district.

Origin of the name

The name is probably derived from Latin, and essential ...

-

Asperg

Asperg () is a town in the district of Ludwigsburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

History

Asperg was established by the County Palatine of Tübingen, whose ruling house had a cadet named Asperg, around a preexisting castle. The town and castle ...

-Hesselberg line. Today this line closely matches the boundary of the Franconian and the Swabian/Alamannic dialects. Despite the fact that the Franks overrode the Alamanni in a partly violent fashion, mixed settlements, such as Ehingen and Röckingen, almost always with a Franconian mayor, developed in the Hesselberg region. The Franks founded the villages of Lenters''heim'', Obermögers''heim'', Geils''heim'', Franken''hofen'', and Königs''hofen'' amongst others. The Franconian peasants established the three field

crop rotation

Crop rotation is the practice of growing a series of different types of crops in the same area across a sequence of growing seasons. It reduces reliance on one set of nutrients, pest and weed pressure, and the probability of developing resistant ...

with its

Flurzwang (a German system of rules relating to communal farmland in the Middle Ages), which was practiced until the modern consolidation of farming. In the 7th century—under the rule of Merovingian king

Dagobert I

Dagobert I ( la, Dagobertus; 605/603 – 19 January 639 AD) was the king of Austrasia (623–634), king of all the Franks (629–634), and king of Neustria and Burgundy (629–639). He has been described as the last king of the Merovingian dyna ...

—

Christianisation

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

started in

Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ...

. In the 8th century

Anglo-Saxon missionaries founded the monastery of

Heidenheim under Franconian

Carolingian rule.

Middle Ages

In the early

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

the Hesselberg region was part of the king's forests. Sparse castle ruins are found on Ehinger mountain and on Schlössleinsbuck. The construction on Ehinger mountain has its seeds in the

Carolingian-

Ottonian

The Ottonian dynasty (german: Ottonen) was a Saxon dynasty of German monarchs (919–1024), named after three of its kings and Holy Roman Emperors named Otto, especially its first Emperor Otto I. It is also known as the Saxon dynasty after the ...

period (8th–9th centuries). Tombs discovered there point towards a violent end caused by Hungarian soldiers at the end of the 10th century when the

Hungarians

Hungarians, also known as Magyars ( ; hu, magyarok ), are a nation and ethnic group native to Hungary () and historical Hungarian lands who share a common culture, history, ancestry, and language. The Hungarian language belongs to the Urali ...

burnt down the whole castle. The building on Schlössleinsbuck was originally intended for use as a refuge, in the 11th or 12th century it was expanded by the

lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the peerage in the United Kingdom, or are ...

s of Lentersheim and adapted as a well-fortified

knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

's castle. The castle's destruction is related in the

family tree

A family tree, also called a genealogy or a pedigree chart, is a chart representing family relationships in a conventional tree structure. More detailed family trees, used in medicine and social work, are known as genograms.

Representations of ...

of the lords of Lentersheim: ''When Conrad of Lentersheim returned from the northern Italian campaigns of king Frederick II. in 1246, his castle was completely destroyed. Thereupon he began building a new castle in Neuenmuhr.'' In fact, soldiers from the Hesselberg region accompanied the mentioned

Hohenstaufen

The Hohenstaufen dynasty (, , ), also known as the Staufer, was a noble family of unclear origin that rose to rule the Duchy of Swabia from 1079, and to royal rule in the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages from 1138 until 1254. The dynast ...

king

Frederick II to Italy in 1239 in order to fight against

pope Gregory IX

Pope Gregory IX ( la, Gregorius IX; born Ugolino di Conti; c. 1145 or before 1170 – 22 August 1241) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 March 1227 until his death in 1241. He is known for issuing the '' Decre ...

. Until they died off at the beginning 19th century, the lords of Lentersheim lived at their castles in Alten- and Neuenmuhr, today's

Muhr am See. After this direct colonisation of Hesselberg ended.

Aufkirchen, which was fortified during medieval times, had a

city wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications with towers, bastions and gates ...

and four

city gates. At that time Aufkirchen had

town privileges

Town privileges or borough rights were important features of European towns during most of the second millennium. The city law customary in Central Europe probably dates back to Italian models, which in turn were oriented towards the traditio ...

.

Age of burgraves and margraves

The age of

burgrave

Burgrave, also rendered as burggrave (from german: Burggraf, la, burgravius, burggravius, burcgravius, burgicomes, also praefectus), was since the medieval period in Europe (mainly Germany) the official title for the ruler of a castle, especia ...

s in Middle Franconia had its origin in the

High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD 150 ...

when king

Henry VI feoffed

Frederick III, who originated from

Swabia, with the heritable fiefdom of the

Nuremberg

Nuremberg ( ; german: link=no, Nürnberg ; in the local East Franconian dialect: ''Nämberch'' ) is the second-largest city of the German state of Bavaria after its capital Munich, and its 518,370 (2019) inhabitants make it the 14th-largest ...

burgrave office in 1192. Frederick III founded the Frankish line of the

House of Hohenzollern

The House of Hohenzollern (, also , german: Haus Hohenzollern, , ro, Casa de Hohenzollern) is a German royal (and from 1871 to 1918, imperial) dynasty whose members were variously princes, electors, kings and emperors of Hohenzollern, Brandenbu ...

under the name "Burgrave Frederick I of Nuremberg". Due to clever marriages and trade-offs the Frankish Zollern gained increasing wealth and influence.

In 1331 the burgraves moved to Ansbach. In 1363 they were elevated to

sovereigns and in 1417 they were feoffed with the

margrave

Margrave was originally the medieval title for the military commander assigned to maintain the defence of one of the border provinces of the Holy Roman Empire or of a kingdom. That position became hereditary in certain feudal families in the Em ...

of

Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 sq ...

. Expensive holding of court and persistent conflicts with the imperial city Nuremberg lead to a high level of debt of the young

principality and consequently they imposed an unbearable burden of taxes upon their subjects. As a consequence, on 6 May 1525 the

German Peasants' War also broke out in southern Franconia. On this day rebellious peasants gathered on Hesselberg's peak, thence they went to

Wassertrüdingen and captured the margrave

vogt

During the Middle Ages, an (sometimes given as modern English: advocate; German: ; French: ) was an office-holder who was legally delegated to perform some of the secular responsibilities of a major feudal lord, or for an institution such as ...

. Afterwards they plundered the monastery of

Auhausen. On their way to

Heidenheim the peasants were captured or killed by margrave soldiers from

Gunzenhausen.

During the

Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battle ...

(1618–1648) large areas of today's Middle Franconia were devastated and depopulated. It was not until the end of the 17th century that the economic and financial situation of the margraves improved. The margraves allowed Austrian and French religious

refugees to become nationals and supported

Jew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

ish merchants in building up an existence, therefore a large number of Jews settled down in villages around Hesselberg. In addition the margraves ran

mercantilistic politics and expanded agricultural education. The last margrave

Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

handed over the principality, now free from debt, to the

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

ns in 1791.

19th and 20th century

An important date in the mountain's history was June 10, 1803, when the Prussian king

Frederick Wilhelm III climbed Hesselberg during his visit to his Frankish estates. In memory of this event the king endowed the ''Hesselberg Mass''. In 1806 the Hesselberg region was handed over to

Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

in the course of an exchange of lands between Bavaria and Prussia: Bavaria received the Prussian principality Ansbach including Hesselberg and in return Prussia obtained the

Wittelsbach

The House of Wittelsbach () is a German dynasty, with branches that have ruled over territories including Bavaria, the Palatinate, Holland and Zeeland, Sweden (with Finland), Denmark, Norway, Hungary (with Romania), Bohemia, the Electorate ...

's

earldom

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form ''jarl'', and meant " chieftain", particula ...

of

Berg Berg may refer to:

People

*Berg (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

*Berg Ng (born 1960), Hong Kong actor

* Berg (footballer) (born 1989), Brazilian footballer

Former states

* Berg (state), county and duchy of the Hol ...

(capital city

Düsseldorf

Düsseldorf ( , , ; often in English sources; Low Franconian and Ripuarian language, Ripuarian: ''Düsseldörp'' ; archaic nl, Dusseldorp ) is the capital city of North Rhine-Westphalia, the most populous state of Germany. It is the second- ...

), located at the

Niederrhein (Bavarian-Prussian Contract of Paris, February 15, 1806). In 1808 the first

local code provided the basis for municipal autonomy, which was expanded by the second Bavarian municipal

edict

An edict is a decree or announcement of a law, often associated with monarchism, but it can be under any official authority. Synonyms include "dictum" and "pronouncement".

''Edict'' derives from the Latin edictum.

Notable edicts

* Telepinu Pro ...

in 1818. Following this many small villages became self-administrating and received the status of a municipality—by the means of law as

juristic person

A juridical person is a non-human legal person that is not a single natural person but an organization recognized by law as a fictitious person such as a corporation, government agency, NGO or International (inter-governmental) Organization (suc ...

s.

Prior to World War II Jewish life and culture played an important role in the whole Hesselberg region. Jewish settlers had already been mentioned in writs in the 14th century and many Jews achieved eminence as merchants and scholars. The

National Socialists

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

were active in the villages around Hesselberg, they destroyed

synagogues and expelled or displaced Jews to

internment camps. The notorious anti-semitic publisher

Julius Streicher

Julius Streicher (12 February 1885 – 16 October 1946) was a member of the Nazi Party, the ''Gauleiter'' (regional leader) of Franconia and a member of the '' Reichstag'', the national legislature. He was the founder and publisher of the virul ...

, as the head of the Frankish Nazi district, established Hesselberg as a meeting place of the Nazis. After the

NSDAP

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that created and supported t ...

came to power in 1933 the annual ''Frankish Days'' (held until 1939) developed from party manifestations. Those were the largest manifestations in Franconia besides the

Nuremberg rally

The Nuremberg Rallies (officially ', meaning ''Reich Party Congress'') refer to a series of celebratory events coordinated by the Nazi Party in Germany. The first rally held took place in 1923. This rally was not particularly large or impactful; ...

.

Hermann Göring

Hermann Wilhelm Göring (or Goering; ; 12 January 1893 – 15 October 1946) was a German politician, military leader and convicted war criminal. He was one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi Party, which ruled Germany from 1933 to 1 ...

attended the Frankish Days twice as a speaker and

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

also once attended. Up to 100,000 visitors on the Osterwiese listened to the virulently

anti-Semitic speeches of Julius Streicher. At that time Hesselberg was named ''Heiliger Berg der Franken'' (Holy Mountain of the Franks). No remains of this dark time are left on Hesselberg. The lofty Nazi plans were never put into practice—the construction of the Adolf-Hitler-School was not realised, nor the Julius-Streicher-

Mausoleum. Prior to World War II the Nazis could only finish an administration building with a garage. Later this garage was used as a chapel by the refugees that were placed on Hesselberg.

Since 1951 Hesselberg has been important to the local

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

s. In this year the Lutheran adult education center was founded and the

Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria (german: Evangelisch-Lutherische Kirche in Bayern) is a Lutheran member church of the Evangelical Church in Germany in the German state of Bavaria.

The seat of the church is in Munich. The '' Landesbischo ...

Congress took place for the first time. Since then thousands of

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

have gathered on

Whit Monday

Whit Monday or Pentecost Monday, also known as Monday of the Holy Spirit, is the holiday celebrated the day after Pentecost, a moveable feast in the Christian liturgical calendar. It is moveable because it is determined by the date of Easter. I ...

to celebrate this ceremony of faith. Between 1945 and 1992 the area around the main peak served as a

radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

station for the

U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

. In 1972 the

Landkreis

In all German states, except for the three city states, the primary administrative subdivision higher than a '' Gemeinde'' (municipality) is the (official term in all but two states) or (official term in the states of North Rhine-Westphalia ...

(district) of Dinkelsbühl and the Hesselberg municipalities was closed in the course of the district reform and incorporated into the

Landkreis Ansbach. In the course of latter reforms many small autonomous municipalities merged into the municipalities of today.

Hesselberg region today

Facilities and events

The most important annual event is the Bavarian Protestant Church Congress. This well known beyond the region and each year on

Whit Monday

Whit Monday or Pentecost Monday, also known as Monday of the Holy Spirit, is the holiday celebrated the day after Pentecost, a moveable feast in the Christian liturgical calendar. It is moveable because it is determined by the date of Easter. I ...

it attracts thousands of Protestants. In a tradition dating from 1803 the Hesselberg Mass has been held on the Osterwiese on the first Sunday in July; it was on this day that king

Frederick William III of Prussia and his wife Luise visited the mountain.

The ''Protestant-Lutheran Adult Education Center Hesselberg'' was founded on May 14, 1951; it was the first Bavarian adult education center. Its main task is adult education for the rural

deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

ry (family nursing, village assistant, business assistant). On September 15, 2005 it was renamed to ''Protestant Education Center Hesselberg'' (''EBZ Hesselberg'' - ''Evangelisches Bildungszentrum Hesselberg''). According to

Reverend Bernd Reuther, chairman of the new education center, its mission is the expansion of the range of education available with emphasis on ''"Faith, Rural Space, and Development of Personality"'' furthermore guest groups should be addressed with their own education programme.

The Protestant-

Lutheran

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

deaconry

Ansbach

Ansbach (; ; East Franconian: ''Anschba'') is a city in the German state of Bavaria. It is the capital of the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Ansbach is southwest of Nuremberg and north of Munich, on the river Fränkische Rezat, ...

has made a popular youth center out of the old Hesselberg house near the peak.

The afar visible television tower with its 119 m is a terrestrial transmitter of the

ZDF and of the ''Bayerisches Fernsehen'' (Bavarian television) for the Franconian region. This tower, which is located at 49° 4' 12" N and 10° 31' 37" E, has an unusual construction: It is a so-called "hybrid tower" and consists of a free-standing steel

skeleton framing base and a wired transmission tower on top. It also broadcasts the

UKW radio programme ''Radio 8''.

In addition radio amateurs maintain a small

relay

A relay

Electromechanical relay schematic showing a control coil, four pairs of normally open and one pair of normally closed contacts

An automotive-style miniature relay with the dust cover taken off

A relay is an electrically operated switch ...

station on the mountain for

voice radio,

packet radio, and amateur television. The energy for this station is supplied by

solar cell

A solar cell, or photovoltaic cell, is an electronic device that converts the energy of light directly into electricity by the photovoltaic effect, which is a physical and chemical phenomenon. s and

wind power

Wind power or wind energy is mostly the use of wind turbines to generate electricity. Wind power is a popular, sustainable, renewable energy source that has a much smaller impact on the environment than burning fossil fuels. Historically ...

.

The four municipalities around the mountain

The borders of four municipalities cross at the mountain. It is noteworthy that the main villages of these municipalities are located at the mountain's foot, whereas the other municipal parts form a starlike pattern around these centers. In the north is

Ehingen

Ehingen (Donau) (; Swabian: ''Eegne'') is a town in the Alb-Donau district in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, situated on the left bank of the Danube, approx. southwest of Ulm and southeast of Stuttgart.

The city, like the entire district of ...

with about 2,100 inhabitants and an area of 47 square kilometres. A trail leads from here through meadows with fruit trees then the afforested northern slope towards the peak. The signs on this trail contain information about

beekeeping. In the east is the small municipality

Röckingen with about 800 inhabitants and an area of . The predominantly sunny trail towards the Osterwiese leads through a picturesque, shady

linden avenue in its final part. On the southern slope lies

Gerolfingen

Gerolfingen is a municipality in the district of Ansbach in Bavaria in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and ...

with about 1,100 inhabitants and an area of 13 km

2 with a road to the parking lots on Hesselberg. A trail leads from Gerolfingen through meadows with fruit trees and a beautiful

chestnut avenue, whose older part was complemented with new plantations in autumn 2004. The village of

Aukirchen with its historical town-hall and St. John's Church, which is visible from afar, belongs to Gerolfingen. In the west is

Wittelshofen with about 1,300 inhabitants and an area of , at the confluence of

Wörnitz and

Sulzach rivers. The town is the starting point of the geological nature trail.

Together with the municipality of

Unterschwaningen

Unterschwaningen is a municipality in the district of Ansbach in Bavaria in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia ...

these four municipalities form the administrative collective of Hesselberg.

Recreational region

The Hesselberg municipalities of

Ehingen

Ehingen (Donau) (; Swabian: ''Eegne'') is a town in the Alb-Donau district in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, situated on the left bank of the Danube, approx. southwest of Ulm and southeast of Stuttgart.

The city, like the entire district of ...

,

Gerolfingen

Gerolfingen is a municipality in the district of Ansbach in Bavaria in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and ...

,

Röckingen, and

Wittelshofen joined with the municipalities of

Dürrwangen,

Langfurth,

Mönchsroth,

Unterschwaningen

Unterschwaningen is a municipality in the district of Ansbach in Bavaria in Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia ...

,

Wassertrüdingen,

Weiltingen, and

Wilburgstetten on January 31, 1973 to form the ''Fremdenverkehrsverband Hesselberg e. V.'' (Tourist Association Hesselberg e. V.). Dürrwangen has since left the association. On the occasion of its 30th anniversary the ''Fremdenverkehrsverband Hesselberg e. V'' changed its name to ''Touristikverband Hesselberg e. V.''. Its headquarters is in Wassertrüdingen. The term ''Hesselberg recreational region'' refers to the combined area of these member municipalities. The German Limes road leads through this region from the West to the East. The ''Entwicklungsgesellschaft Region Hesselberg mbH'' (Development Incorporation of Hesselberg Region) was founded on October 5, 1999. This is a federation of municipalities that extends far beyond the borders of the Hesselberg region. The tasks and spheres of influences of this incorporation are very broad and contain amongst others the economy, culture, and tourism. The main office resides at castle Unterschwaningen.

The huge number of meadows containing fruit trees has led to the formation of the ''Interessengemeinschaft Moststraße'' (Community of Interest

Must-Road) by several

commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

s. The Must-Road around Hesselberg is planned for the near future, both to better market the fruit products and as a new tourist attraction.

In and around the Hesselberg area there are many trails. The two main trails have many signs containing information for the hiker. The geological nature trail, which is 3 km long, leads from its starting point near Wittelshofen to the mountain's peak. The signs along the route tell of the geological history and structure of the mountain. The Hesselberg-trail forms a round-trip of Hesselberg's heights. Both trails are well combinable. The Osterwiese is meeting point for

model plane pilots, the launch areas for

hang-gliders and

paraglider

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a harness or lies supine in a cocoon-like ' ...

s can be found there too. The regional

gliding airfield is in nearby Irsingen.

Sporting clays was prohibited by the Nature Conservation Agency due to

lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

exposure. The Hesselberg Tourist Office, the ''Bund Naturschutz in Bayern'' (Bavarian Nature Conservation Alliance) (Ansbach district group), and the ''Landesbund für Vogelschutz in Bayern'' (Bavarian State Bird Conservation Alliance) (Ansbach district group) organise guided excursions and walking tours. At the mountain's foot anglers can indulge their passion at the Wörnitz and Sulzach rivers. The

German Alpine Association (Hesselberg section with an office in

Bechhofen) have built a small hut on the northern slope in order to support winter sports.

Tourist destinations include:

* the old cities of

Nördlingen

Nördlingen (; Swabian: ''Nearle'' or ''Nearleng'') is a town in the Donau-Ries district, in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, with a population of approximately 20,674. It is located approximately east of Stuttgart, and northwest of Munich. It was b ...

,

Dinkelsbühl

Dinkelsbühl () is a historic town in Central Franconia, a region of Germany that is now part of the state of Bavaria, in southern Germany. Dinkelsbühl is a former free imperial city of the Holy Roman Empire. In local government terms, Dinkelsb� ...

,

Feuchtwangen

Feuchtwangen is a city in Ansbach district in the administrative region of Middle Franconia in Bavaria, Germany with around 12,000 citizens and 137km² of landmass making it the biggest city in the Ansbach district by Population and Landmass. In t ...

,

Rothenburg,

Ansbach

Ansbach (; ; East Franconian: ''Anschba'') is a city in the German state of Bavaria. It is the capital of the administrative region of Middle Franconia. Ansbach is southwest of Nuremberg and north of Munich, on the river Fränkische Rezat, ...

, and

Gunzenhausen

* the Franconian lakeland

* the

Hahnenkamm

*

Altmühltal nature park

*

Ruffenhofen Latin park

Landscape conservation

Sheep

grazing

In agriculture, grazing is a method of animal husbandry whereby domestic livestock are allowed outdoors to roam around and consume wild vegetations in order to convert the otherwise indigestible (by human gut) cellulose within grass and other ...

of the herding areas is necessary for the conservation of the semidry and dry meadows. However, encroachment of scrub such as

blackthorne,

rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

,

juniper, and

ash has greatly increased at many places on the mountain despite the presence of herds belonging to two sheep farms (northern side: approx. 600

ewes, southern side: approx. 1000 ewes). Without additional mechanical maintenance the open space on the mountain will not remain open in the long term. Since 1997 the municipality of Ehingen has struck out in new directions to deal with the conservation of these vast herding areas on Hesselberg's northern slopes. Annual civil campaigns of important "descrubbing" and maintenance tasks are performed as a collaboration between the ''Landschaftspflegeverband Mittelfranken'' (Middle Franconian Landscape Conservation Association) and the shepherd Hans Goth. Under the banner phrase "One day for the mountain" many teenagers, seniors citizens, farmers, and non-farmers make a pilgrimage to the mountain on a particular day each autumn and work together. The work gets done in just four hours of working time, interrupted by a short snack and finished with lunch. On average there are 40 people voluntarily working in Ehingen. This active support of sheep farming by the citizens ("descrubbing" significantly improves the pasture conditions) has multiple functions:

* Novel working methods in the fields of landscape and nature conservation

* Active support of Goth sheep farm by the community (board cost, use of the municipal tractors, etc.) and by the citizens encourages neighbourliness and reduces prejudices.

* Exemplary activity for the conservation of flora and fauna (active landscape and nature conservation) within the nearby cultural landscape (reinforcement of the identification with the homeland)

* Social-communicative aspects: The participants are farmers and non-farmers. With their participation awareness of the problems of land use is raised also within unrelated to agriculture.

* Shared work, snacks and lunch bring together the participants.

* Participants of different age groups (from 16 to 70) are brought together and prejudices are reduced ("Today's youth isn't interested in anything").

* Due to its volunteers the municipality is independent from state interventions.

* Since 2001 the Hesselberg municipalities of Röckingen and Gerolfingen have followed this positive and successful example. They also hold activity days under the flag of "One day for the mountain".

Flora and fauna

Due to its multilayered rock, soil, climate, and cultivation, Hesselberg has bred a variety of

vegetation

Vegetation is an assemblage of plant species and the ground cover they provide. It is a general term, without specific reference to particular taxa, life forms, structure, spatial extent, or any other specific botanical or geographic characte ...

with some plant communities particular to the area.

Vegetation of the neglected grassland

An important task of the

landscape maintenance

Landscape maintenance (or groundskeeping) is the art and vocation of keeping a landscape healthy, clean, safe and attractive, typically in a garden, yard, park, institutional setting or estate. Using tools, supplies, knowledge, physical exerti ...

is the conservation of the dry and non-forested neglected meadows and dry meadowy slopes. Botanists have named this type of vegetation ''Magerrasen'' (neglected grassland). The ground there is covered with thin dry grass and a typical feature are the irregularly spaced

juniper bushes. Well over 40 different species of flowering plants grow on this nutrient-poor, non-fertilised soil. Often different small species of

gentian

''Gentiana'' is a genus of flowering plants belonging to the gentian family (Gentianaceae), the tribe Gentianeae, and the monophyletic subtribe Gentianinae. With about 400 species it is considered a large genus. They are notable for their mostl ...

can be found. In late summer

pasqueflower

The genus ''Pulsatilla'' contains about 40 species of herbaceous perennial plants native to meadows and prairies of North America, Europe, and Asia. Derived from the Hebrew word for Passover, "pasakh", the common name pasque flower refers to the ...

and

Carline thistle bloom. From April until June

orange tips fly over the sunny slopes. One of the most important tasks for conservation of the neglected grassland is traditional

herding

Herding is the act of bringing individual animals together into a group (herd), maintaining the group, and moving the group from place to place—or any combination of those. Herding can refer either to the process of animals forming herds in ...

. Grazing with

sheep

Sheep or domestic sheep (''Ovis aries'') are domesticated, ruminant mammals typically kept as livestock. Although the term ''sheep'' can apply to other species in the genus '' Ovis'', in everyday usage it almost always refers to domesticated ...

is a prerequisite for the long-lasting conservation of this grassland. If the amount of herding was reduced, initially more thorny and needle-bearing shrubs would grow because these are eschewed by sheep - the large number of juniper bushes thrive for the same reason. Under cover of these thornbushes and hedges other groves and the first trees would develop. In the final stage the mountain would become mostly overgrown with forest. The herbs and grasses of the neglected grassland have a positive influence on the quality of the sheep's meat. Due to this fact the restaurants of the Hesselberg region increasingly offer dishes of ''Hesselberg lamb''.

Meadows, hedges, and wells

In many ways the fruitful meadows and fields of the Early Jurassic soil in Hesselberg's vicinity are the opposite of the nutrient-poor neglected grassland. This region has been traditionally used for agriculture. In its fields

wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

,

rye,

oat

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural, unlike other cereals and pseudocereals). While oats are suitable for human con ...

,

beetroot, and

corn are cultivated. On the farms

pigs

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

and

cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, cloven-hooved, herbivores. They are a prominent modern member of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus ''Bos''. Adult females are referred to as cows and adult ma ...

are raised and

dairy farming

Dairy farming is a class of agriculture for long-term production of milk, which is processed (either on the farm or at a dairy plant, either of which may be called a dairy) for eventual sale of a dairy product. Dairy farming has a history th ...

is performed.

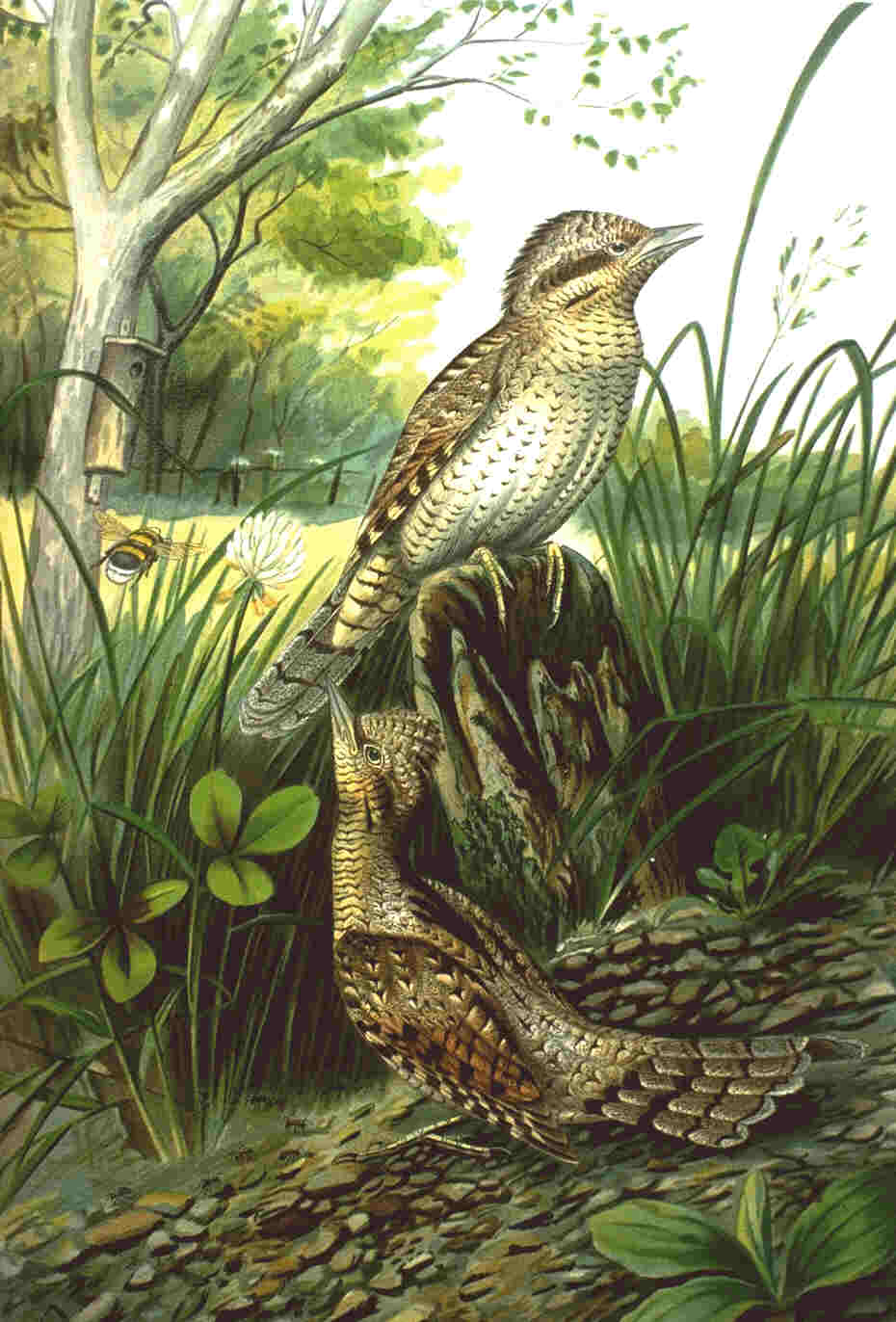

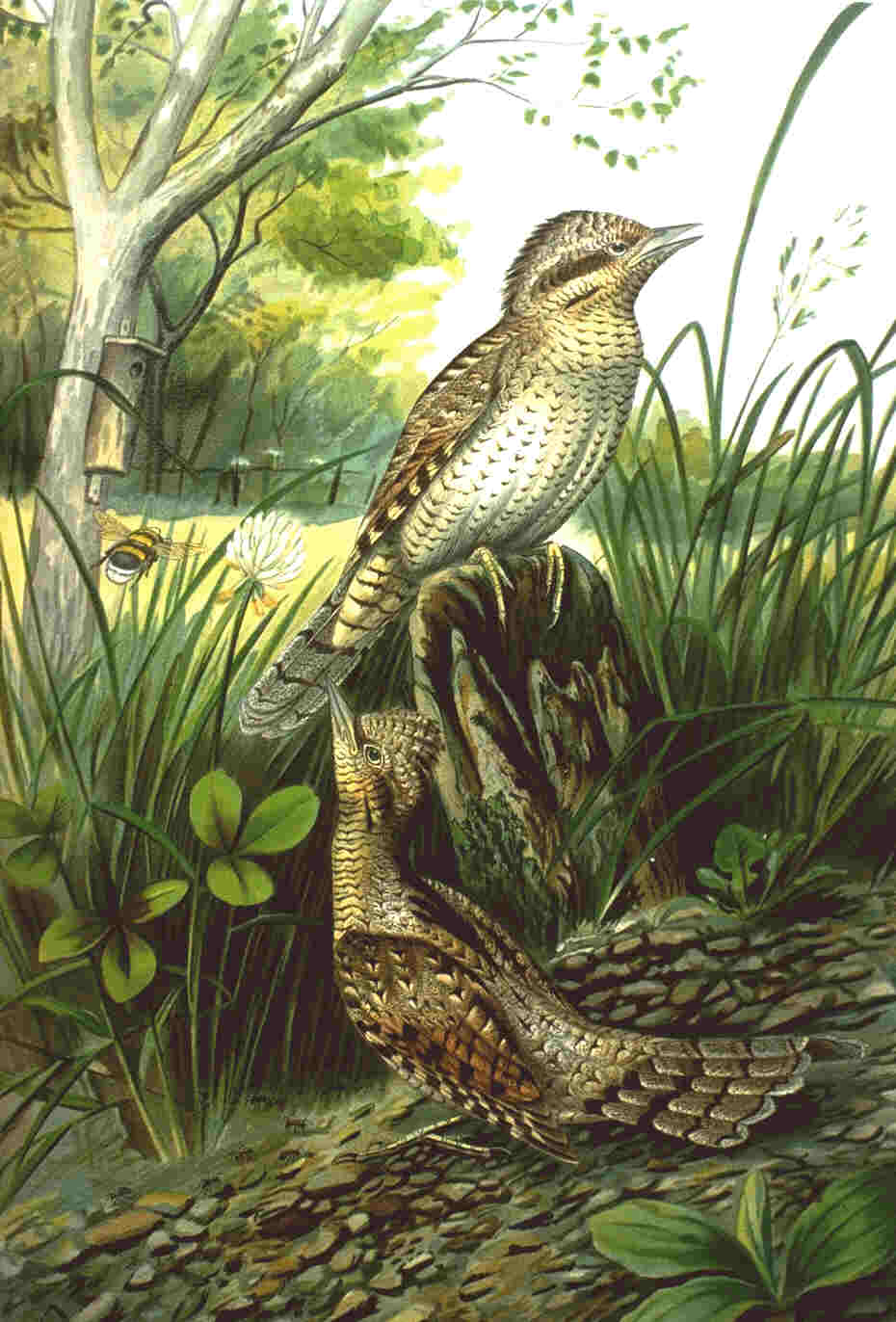

In the lower and middle parts of the slopes old and non-fertilised meadows with fruit trees offer a blaze of colour of different flowers. With their high trunks the fruit groves provide the optimal habitat for a diversity of small animals, birds, and plants. The

wryneck

The wrynecks (genus ''Jynx'') are a small but distinctive group of small Old World woodpeckers. ''Jynx'' is from the Ancient Greek ''iunx'', the Eurasian wryneck.

These birds get their English name from their ability to turn their heads almos ...

is one of the typical inhabitants of these meadows, because they avoid bleak areas and dense forests. Just as important for the small animals, birds, and plants are the various hedges and shrubs, which can be found everywhere on and around Hesselberg. In our farmed landscape hedges have the largest variety of microhabitats. In addition to the groves there is a herb layer—rich in species—a sunny herb fringe,

coarse woody debris

Coarse woody debris (CWD) or coarse woody habitat (CWH) refers to fallen dead trees and the remains of large branches on the ground in forests and in rivers or wetlands.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). C ...

, and possibly special

biotopes, such as the piles of stones. Because of the transition from water-permeable to impermeable rock layers several spring horizons have emerged, explaining the richness of the springs. On Hesselberg there are several deep wells, but most springs appear in the form of flat

swamps. The special flora and fauna of the wells is not immediately obvious, because most of the organisms are

microscopic

The microscopic scale () is the scale of objects and events smaller than those that can easily be seen by the naked eye, requiring a lens or microscope to see them clearly. In physics, the microscopic scale is sometimes regarded as the scale be ...

.

Sundew

''Drosera'', which is commonly known as the sundews, is one of the largest genera of carnivorous plants, with at least 194 species. 2 volumes. These members of the family Droseraceae lure, capture, and digest insects using stalked mucilaginou ...

is a very rare plant found in these wetlands.

Biodiversity of the forest

On Hesselberg all forms (

high forest,

coppice-with-standards,

coppice

Coppicing is a traditional method of woodland management which exploits the capacity of many species of trees to put out new shoots from their stump or roots if cut down. In a coppiced wood, which is called a copse, young tree stems are repeate ...

) and types (

temperate coniferous forest

Temperate coniferous forest is a terrestrial biome defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature. Temperate coniferous forests are found predominantly in areas with warm summers and cool winters, and vary in their kinds of plant life. In some, needle ...

,

mixed forest

Temperate broadleaf and mixed forest is a temperate climate terrestrial habitat type defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature, with broadleaf tree ecoregions, and with conifer and broadleaf tree mixed coniferous forest ecoregions.

These fo ...

,

deciduous forest

In the fields of horticulture and Botany, the term ''deciduous'' () means "falling off at maturity" and "tending to fall off", in reference to trees and shrubs that seasonally shed leaves, usually in the autumn; to the shedding of petals, ...

) of forests can be found. The coppice in the upper regions of the northern slope has the strangest appearance. After

coppicing

Coppicing is a traditional method of woodland management which exploits the capacity of many species of trees to put out new shoots from their stump or roots if cut down. In a coppiced wood, which is called a copse, young tree stems are repeate ...

more light reaches the ground and thermophile animals such as the

sand lizard

The sand lizard (''Lacerta agilis'') is a lacertid lizard distributed across most of Europe from France and across the continent to Lake Baikal in Russia. It does not occur in European Turkey. Its distribution is often patchy. In the sand lizard' ...

thrive. Later, when the canopy closes again, many other specialised animals such as the

Eurasian woodcock

The Eurasian woodcock (''Scolopax rusticola'') is a medium-small wading bird found in temperate and subarctic Eurasia. It has cryptic camouflage to suit its woodland habitat, with reddish-brown upperparts and buff-coloured underparts. Its eyes ...

find a suitable habitat. All

game that is typical of German forests (for example

hare,

roe

Roe ( ) or hard roe is the fully ripe internal egg masses in the ovaries, or the released external egg masses, of fish and certain marine animals such as shrimp, scallop, sea urchins and squid. As a seafood, roe is used both as a cooked in ...

,

red fox, and

squirrel) are present in Hesselberg's woods. The drumming of

woodpecker

Woodpeckers are part of the bird family Picidae, which also includes the piculets, wrynecks, and sapsuckers. Members of this family are found worldwide, except for Australia, New Guinea, New Zealand, Madagascar, and the extreme polar regions. ...

s and the crying of

cuckoos

Cuckoos are birds in the Cuculidae family, the sole taxon in the order Cuculiformes . The cuckoo family includes the common or European cuckoo, roadrunners, koels, malkohas, couas, coucals and anis. The coucals and anis are sometimes separa ...

contribute to the mood of the wood as well as the singing of countless birds. Various

Ranunculaceae

Ranunculaceae (buttercup or crowfoot family; Latin "little frog", from "frog") is a family of over 2,000 known species of flowering plants in 43 genera, distributed worldwide.

The largest genera are ''Ranunculus'' (600 species), ''Delphinium' ...

—such as

liverworts and

wood anemones—are the signs of spring in Hesselberg's forests. In May

ramsons turn the ground of the deciduous forest into a carpet of green and white blooms. After blooming the intense odour of garlic fills the air. The various species of

orchid

Orchids are plants that belong to the family Orchidaceae (), a diverse and widespread group of flowering plants with blooms that are often colourful and fragrant.

Along with the Asteraceae, they are one of the two largest families of flowerin ...

s such as the

red helleborine have become increasingly rare. The

Turk's-cap lily, which belongs to the

lily family, can still be found relatively often but flower's diversity is in need of protection. The ''

erica

Erica or ERICA may refer to:

* Erica (given name)

* ''Erica'' (plant), a flowering plant genus

* Erica (chatbot), a service of Bank of America

* ''Erica'' (video game), a 2019 FMV video game

* ''Erica'' (spider), a jumping spider genus

* E ...

'' and the ''

Cytisus scoparius

''Cytisus scoparius'' ( syn. ''Sarothamnus scoparius''), the common broom or Scotch broom, is a deciduous leguminous shrub native to western and central Europe. In Britain and Ireland, the standard name is broom; this name is also used for oth ...

'' prefer the iron sandstone layers of the lower parts of the slopes.

Image:Türkenbund_ganz.jpg

Image:Türkenbund_gefleckt.jpg

Image:Türkenbund_dunkel.jpg

Image:Türkenbund_lila.jpg

Image:Türkenbund_lila2.jpg

Image:Türkenbund_hell.jpg

Appendix: sagas and legends

It is unsurprising that such a peculiar mountain with its associated history is shrouded in legends, sagas and prophesies of destiny, many of these contain recognisable parallels to the real history of the area. In heavy thunder storms people recognised the remaining walls of the ruins as eerie figures and specters, which they associated with the former inhabitants of the castles. Later the castle remains were carried away and used as construction material elsewhere strengthening the image of castles sunk into the mountain. Four examples from the numerous legends of Hesselberg are provided:

The legend of the Devil's Hole

A long time ago some young lads herded sheep on Hesselberg. At that time there was a deep cave on the mountain, which is buried today. Bursting with curiosity they wanted to know what was inside. One of them was lowered by rope down into the deep hole. Beforehand the boys had decided to pull him up immediately when he gave a tug on the rope. Soon after the boy went into the cave, a three-legged rabbit hobbled across the way, the other lads followed it spontaneously in order to catch it, but the farther they chased the faster the rabbit ran. Finally they gave up. When they returned to the cave they remembered their fellow in the hole and they immediately pulled the rope up. It was stained with blood and at its end there hung a goat's hoof and a note with the mark 'Skrap' upon it, but the boy was gone forever.

The mountain's specter

Legend has it that a long time ago a big fortress stood upon Hesselberg, known as Owl Castle. In that castle there lived a lord and his only daughter. The girl kept the house and had the keys for all the rooms. At that time the

Huns

The Huns were a nomadic people who lived in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Eastern Europe between the 4th and 6th century AD. According to European tradition, they were first reported living east of the Volga River, in an area that was part ...

invaded the Hesselberg region, they burnt down the castle and the girl died within the ruins. Legend has it that she still haunts the mountain carrying her bunch of keys on her belt. She is seen mostly in Saturday night after the four

Ember days.

The unsaved virgins of Schlößleinsbruck

Locals tell the story of the specters of three cursed virgins that live on the Schlößleinsbuck: daughters of the local bishop Stuart Ward. Two of them are dressed completely in white, but the third one wears a black skirt. The three virgins appeared to a farm laborer, who tilled a field near the mountain. They begged him to follow them into the mountain to release them and that because he is of pure heart, he need not fear the evil forces of darkness. They told him that on the way into the mountain they would first meet six men who have beards to the floor and sit around a table, the Pipianer. In the second room there would be sat a black dog with fervid eyes, holding a key in its mouth, the Jaksland. The farm laborer should take this key, even if the dog is spitting fire. With this key would then be able to get into a chamber containing a great treasure, which would then belong to him. But the farm laborer became very scared and left the virgins unsaved. It is further told that the virgins still speak to brave men, who should follow them into the mountain in order to save them.

The tale of Viktor of Hesselberg

There were once rumours of a deep network of caves known as the Regensen grottoes. Within the cave network there were many goblins, organised into different unions with peculiar names like Hof, Ping and Konvencio. One day, an innocent young boy named Viktor fell into the caves. He lived there for many months, uncertain of how to escape.

When the traditional Yule celebrations began, he joined with the Konvencio union, becoming King of the Goblins, and leading them to victory against the other unions! Each Christmas, walkers can call out 'Konvencio' into the wind, and hear the other goblins grumble about their defeat. One day it is prophesied that Viktor will be reincarnated, return to Konvencio, and lead them to victory once again.

References

All references are in German.

* Johann Schrenk, Karl Friedrich Zink, Walter E. Keller: ''Vom Hahnenkamm zum Hesselberg.'' Bilder einer fränkischen Kulturlandschaft. Keller, Treuchtlingen 2000.

* Arthur Berger: ''Der Hesselberg. Funde und Ausgrabungen bis 1985.'' Lassleben, Kallmünz 1994.

* Hermann Schmidt-Kaler: ''Vom Neuen Fränkischen Seenland zum Hahnenkamm und Hesselberg.'' Wanderungen in die Erdgeschichte. Vol. . Pfeil, München 1991.

* Albert Schlagbauer: ''Der Hesselberg zwischen Franken und Schwaben.'' Steinmeier, Nördlingen 1980.

* Albert Schlagbauer: ''Die Frankenhöhe, im oberen Wörnitzgrund, im Tal der Sulzach, rund um den Hesselberg.'' Steinmeier, Nördlingen 1988.

* Schlagbauer Albert, Fischer Adolf: ''Rund um den Hesselberg.'' Fränkisch-Schwäbischer Heimatverlag, Oettingen 1965.