Henry Morton Stanley on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A former hospital in

A former hospital in

Stanley and Livingstone

Original reports from The Times * * * *

H M Stanley Hospital

''How I Found Livingstone''

illustrated. From

''In darkest Africa; or, The quest, rescue, and retreat of Emin, governor of Equatoria. Volume 1''

(1890), illustrated. From

''In darkest Africa; or, The quest, rescue, and retreat of Emin, governor of Equatoria. Volume 2''

(1890), illustrated. From

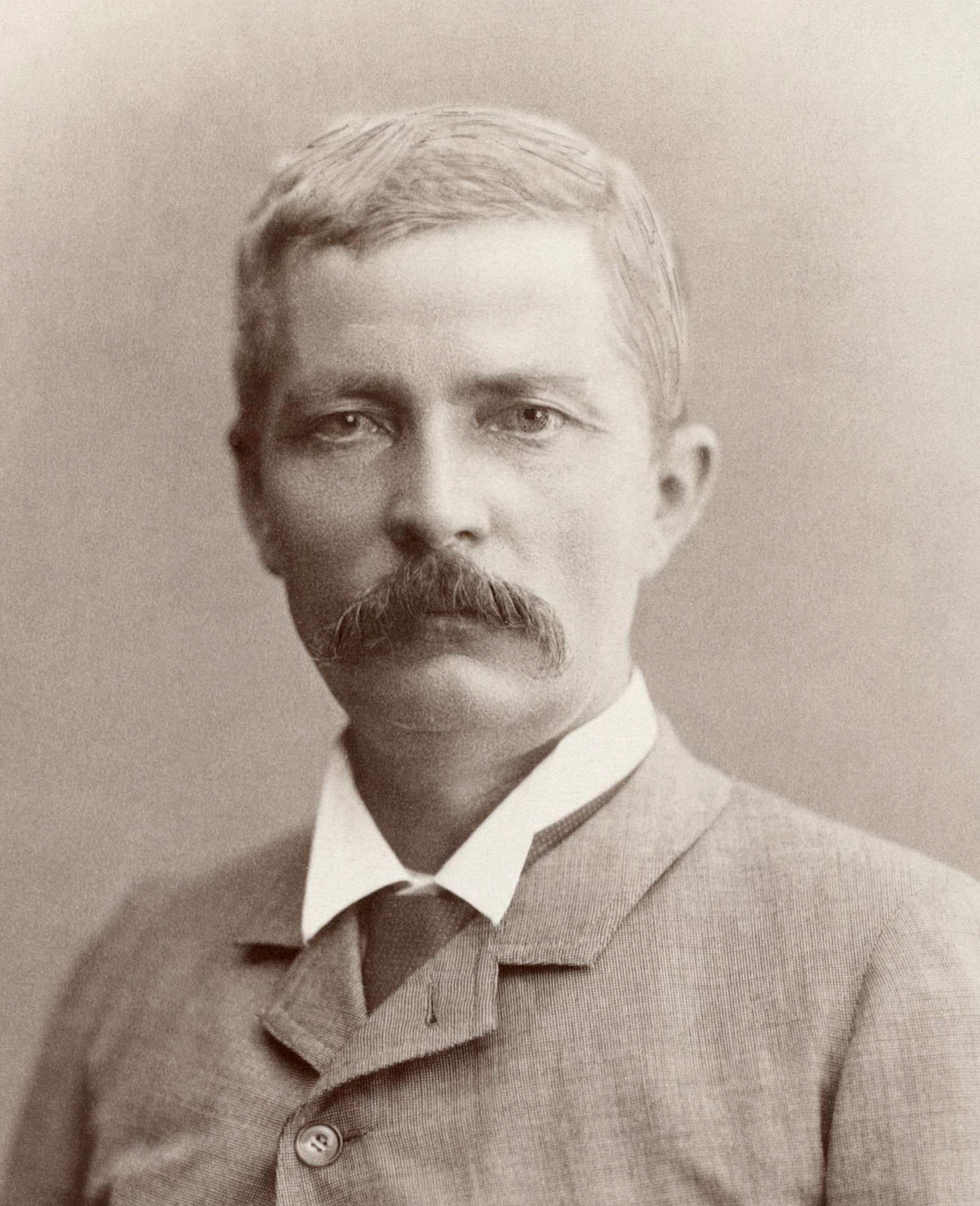

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (1841–1904), Explorer and journalist

Sitter associated with 27 portraits

Letters and maps associated with HM Stanley from Gathering the Jewels

HM Stanley and Knife Crime

* * Collected journalism of Henry Stanley a

*

Archive Henry Morton Stanley

Royal Museum for Central Africa {{DEFAULTSORT:Stanley, Henry Morton 1841 births 1904 deaths 19th-century American journalists 19th-century British journalists 19th-century Welsh writers American Civil War prisoners of war American explorers American male journalists American war correspondents British people of the American Civil War Burials in Surrey Confederate States Army soldiers Liberal Unionist Party MPs for English constituencies The Daily Telegraph people Explorers of Africa Foreign Confederate military personnel Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath New York Herald people People from Denbigh People from St Asaph UK MPs 1895–1900 Union Army soldiers Union Navy sailors Welsh emigrants to the United States Welsh explorers Welsh journalists Welsh-speaking journalists International Association of the Congo 19th-century English businesspeople

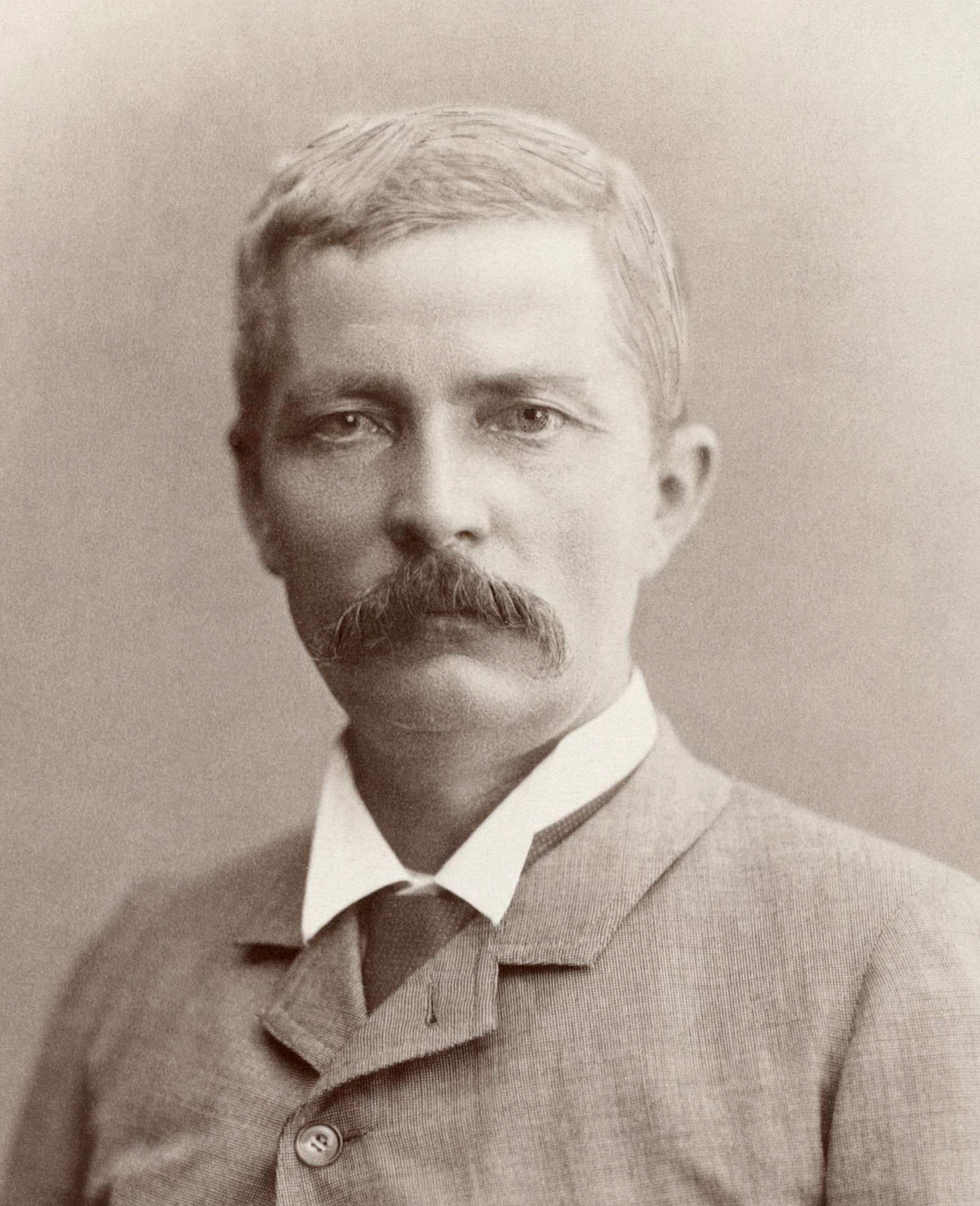

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author and politician who was famous for his exploration of

Henry Stanley was born as John Rowlands in

Henry Stanley was born as John Rowlands in

Following the American Civil War, Stanley became a journalist in the days of frontier expansion in the

Following the American Civil War, Stanley became a journalist in the days of frontier expansion in the

Stanley travelled to

Stanley travelled to  Stanley found

Stanley found ' s own first account of the meeting, published 1 July 1872, reports:

In 1874, the ''

In 1874, the '' It was therefore essential that Stanley should trace the course of the Lualaba downstream (northward) from

It was therefore essential that Stanley should trace the course of the Lualaba downstream (northward) from

Stanley was approached by King Leopold II of the Belgians, the monarch who had already established the

Stanley was approached by King Leopold II of the Belgians, the monarch who had already established the

Stanley, much more familiar with the rigors of the African climate and the complexities of local politics than

Stanley, much more familiar with the rigors of the African climate and the complexities of local politics than  In 1879, Stanley left for Africa for his first mission under Leopold's orders. King Leopold II gave Stanley clear instructions: "''It is not about Belgian colonies. It is about establishing a new state that is as large as possible and about its governance. It should be clear that in this project there can be no question of granting the Negroes the slightest form of political power. That would be ridiculous. The whites, who lead the posts, have all the power.''"

Stanley described in writings his dismay with the terrible scenes taking place in Congo. He also reported of atrocities and cannibalism come in. At the same time, his 'findings' conveyed an idea that the dark continent must submit, willingly or otherwise. Stanley's writings show that he, too, held this view. ''"Only by proving that we are superior to the savages, not only through our power to kill them but through our entire way of life, can we control them as they are now, in their present stage; it is necessary for their own well-being, even more than ours."''

Unexpectedly, France sent its own expedition to the

In 1879, Stanley left for Africa for his first mission under Leopold's orders. King Leopold II gave Stanley clear instructions: "''It is not about Belgian colonies. It is about establishing a new state that is as large as possible and about its governance. It should be clear that in this project there can be no question of granting the Negroes the slightest form of political power. That would be ridiculous. The whites, who lead the posts, have all the power.''"

Stanley described in writings his dismay with the terrible scenes taking place in Congo. He also reported of atrocities and cannibalism come in. At the same time, his 'findings' conveyed an idea that the dark continent must submit, willingly or otherwise. Stanley's writings show that he, too, held this view. ''"Only by proving that we are superior to the savages, not only through our power to kill them but through our entire way of life, can we control them as they are now, in their present stage; it is necessary for their own well-being, even more than ours."''

Unexpectedly, France sent its own expedition to the

Having found the new ruler of the Upper Congo, Stanley had no choice but to negotiate an agreement with him, to stop Tip coming further downstream and attacking Leopoldville,

Having found the new ruler of the Upper Congo, Stanley had no choice but to negotiate an agreement with him, to stop Tip coming further downstream and attacking Leopoldville,

The spread of

The spread of  The records at the National Archives at Kew, London, offer an even deeper insight and show that annexation was a purpose he had been aware of for the expedition. This is because there are a number of treaties curated there (and gathered by Stanley himself from what is present-day

The records at the National Archives at Kew, London, offer an even deeper insight and show that annexation was a purpose he had been aware of for the expedition. This is because there are a number of treaties curated there (and gathered by Stanley himself from what is present-day

In ''Through the Dark Continent'', Stanley observed the peoples of the region, and wrote that "the savage only respects force, power, boldness, and decision". Stanley further wrote: 'If Europeans will only ... study human nature in the vicinity of Stanley Pool (Kinshasa), they will go home thoughtful men, and may return again to this land to put to good use the wisdom they should have gained ... during their peaceful sojourn.'

In ''How I Found Livingstone'', he wrote that he was "prepared to admit any black man possessing the attributes of true manhood, or any good qualities ... to a brotherhood with myself."

Stanley insulted and shouted at

In ''Through the Dark Continent'', Stanley observed the peoples of the region, and wrote that "the savage only respects force, power, boldness, and decision". Stanley further wrote: 'If Europeans will only ... study human nature in the vicinity of Stanley Pool (Kinshasa), they will go home thoughtful men, and may return again to this land to put to good use the wisdom they should have gained ... during their peaceful sojourn.'

In ''How I Found Livingstone'', he wrote that he was "prepared to admit any black man possessing the attributes of true manhood, or any good qualities ... to a brotherhood with myself."

Stanley insulted and shouted at

* '' Stanley and Livingstone'', a 1939 film, stars

* '' Stanley and Livingstone'', a 1939 film, stars

produced a six-part dramatised documentary series entitled ''Search for the Nile''. Much of the series was shot on location, with Stanley played by Central Africa

Central Africa is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries according to different definitions. Angola, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo ...

and his search for missionary and explorer David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

, whom he later claimed to have greeted with the now-famous line: "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?". Besides his discovery of Livingstone, he is mainly known for his search for the sources of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

and Congo rivers, the work he undertook as an agent of King Leopold II of the Belgians which enabled the occupation of the Congo Basin region, and his command of the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition of 1886 to 1889 was one of the last major European expeditions into the interior of Africa in the nineteenth century, ostensibly to the relief of Emin Pasha, General Charles Gordon's besieged governor of Equato ...

. He was knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

ed in 1897, and served in Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as a Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

member for Lambeth North from 1895 to 1900.

More than a century after his death, Stanley's legacy remains the subject of enduring controversy. Although he personally had high regard for many of the native African people who accompanied him on his expeditions, the exaggerated accounts of corporal punishment and brutality in his books fostered a public reputation as a hard-driving, cruel leader, in contrast to the supposedly more humanitarian Livingstone. His contemporary image in Britain also suffered from the inaccurate perception that he was American. In the 20th century, his reputation was also seriously damaged by his role in establishing the Congo Free State

''(Work and Progress)

, national_anthem = Vers l'avenir

, capital = Vivi Boma

, currency = Congo Free State franc

, religion = Catholicism (''de facto'')

, leader1 = Leopo ...

for King Leopold II. Nevertheless, he is recognized for his important contributions to Western knowledge of the geography of Central Africa and for his resolute opposition to the slave trade in East Africa.

Early life

Henry Stanley was born as John Rowlands in

Henry Stanley was born as John Rowlands in Denbigh

Denbigh (; cy, Dinbych; ) is a market town and a community in Denbighshire, Wales. Formerly, the county town, the Welsh name translates to "Little Fortress"; a reference to its historic castle. Denbigh lies near the Clwydian Hills.

History

...

, Denbighshire

Denbighshire ( ; cy, Sir Ddinbych; ) is a county in the north-east of Wales. Its borders differ from the historic county of the same name. This part of Wales contains the country's oldest known evidence of habitation – Pontnewydd (Bontnewy ...

, Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. His mother Elizabeth Parry was 18 years old at the time of his birth. She abandoned him as a very young baby and cut off all communication. Stanley never knew his father, who died within a few weeks of his birth. There is some doubt as to his true parentage. As his parents were unmarried, his birth certificate

A birth certificate is a vital record that documents the birth of a person. The term "birth certificate" can refer to either the original document certifying the circumstances of the birth or to a certified copy of or representation of the ensuin ...

describes him as a bastard

Bastard may refer to:

Parentage

* Illegitimate child, a child born to unmarried parents

** Bastard (law of England and Wales), illegitimacy in English law

People People with the name

* Bastard (surname), including a list of people with that na ...

; he was baptised in the parish of Denbigh on 19 February 1841, the register recording that he had been born on 28 January of that year. The entry states that he was the bastard son of John Rowland of Llys Llanrhaidr and Elizabeth Parry of Castle. The stigma of illegitimacy

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as '' ...

weighed heavily upon him all his life.

The boy was given his father's surname of Rowlands and brought up by his grandfather Moses Parry, a once-prosperous butcher who was living in reduced circumstances. He cared for the boy until he died, when John was five. Rowlands stayed with families of cousins and nieces for a short time, but he was eventually sent to the St. Asaph Union Workhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

for the Poor. The overcrowding and lack of supervision resulted in his being frequently abused by older boys. Historian Robert Aldrich has alleged that the headmaster of the workhouse raped or sexually assaulted Rowlands, and that the older Rowlands was "incontrovertibly bisexual". When Rowlands was ten, his mother and two half-siblings stayed for a short while in this workhouse, but he did not recognize them until the headmaster told him who they were.

Life in the United States

Rowlands emigrated to the United States in 1859 at age 18. He disembarked atNew Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

and, according to his own declarations, became friends by accident with Henry Hope Stanley, a wealthy trader. He saw Stanley sitting on a chair outside his store and asked him if he had any job openings. He did so in the British style: "Do you need a boy, sir?" The childless man had indeed been wishing he had a son, and the inquiry led to a job and a close relationship between them. Out of admiration, John took Stanley's name. Later, he wrote that his adoptive parent died two years after their meeting, but in fact the elder Stanley did not die until 1878. This and other discrepancies led John Bierman to argue that no adoption took place. Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Tim Jeal

John Julian Timothy Jeal, known as Tim Jeal (born 27 January 1945 in London, England), is a British biographer of notable Victorians and is also a novelist. His publications include a memoir and biographies of David Livingstone (1973), Lord Ba ...

goes further, and, in Chapter Two of his biography, subjects Stanley's account in his posthumously published ''Autobiography'' to detailed analysis. Because Stanley got so many basic facts wrong about his purported adoptive family, Jeal concludes that it is very unlikely that he ever met rich Henry Hope Stanley, and that an ordinary grocer, James Speake, was Rowlands' true benefactor until his (Speake's) sudden death in October 1859.

Stanley reluctantly joined in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, first enrolling in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

's 6th Arkansas Infantry Regiment

The 6th Arkansas Infantry Regiment (also known as the "Sixth Arkansas"; June 10, 1861 – May 1, 1865) was a regiment of the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. Organized mainly from volunteer companies, including several prewar ...

and fighting in the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

in 1862. After being taken prisoner at Shiloh, he was recruited at Camp Douglas, Illinois, by its commander Colonel James A. Mulligan

James Adelbert Mulligan (June 30, 1830 – July 26, 1864) was colonel of the 23rd Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War. On February 20, 1865, the United States Senate confirmed the posthumous app ...

as a " Galvanized Yankee." He joined the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

on 4 June 1862 but was discharged 18 days later because of severe illness. After recovering, he served on several merchant ships before joining the US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage of ...

in July 1864. He became a record keeper on board the , and participated in the First Battle of Fort Fisher

The First Battle of Fort Fisher was a naval siege in the American Civil War, when the Union tried to capture the fort guarding Wilmington, North Carolina, the South's last major Atlantic port. Led by Major General Benjamin Butler, it lasted fro ...

and the Second Battle of Fort Fisher

The Second Battle of Fort Fisher was a successful assault by the Union Army, Navy and Marine Corps against Fort Fisher, south of Wilmington, North Carolina, near the end of the American Civil War in January 1865. Sometimes referred to as the "Gib ...

, which led him into freelance journalism. Stanley and a junior colleague jumped ship on 10 February 1865 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire

Portsmouth is a city in Rockingham County, New Hampshire, United States. At the 2020 census it had a population of 21,956. A historic seaport and popular summer tourist destination on the Piscataqua River bordering the state of Maine, Portsmou ...

, in search of greater adventures. Stanley was possibly the only man to serve in all three of the Confederate Army, the Union Army, and the Union Navy.

Journalist

American West

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Far West, and the West) is the region comprising the westernmost states of the United States. As American settlement in the U.S. expanded westward, the meaning of the term ''the Wes ...

. He then organised an expedition to the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

that ended catastrophically when he was imprisoned. He eventually talked his way out of jail and received restitution for damaged expedition equipment.

In 1867, the emperor of Ethiopia

The emperor of Ethiopia ( gez, ንጉሠ ነገሥት, nəgusä nägäst, "King of Kings"), also known as the Atse ( am, ዐፄ, "emperor"), was the hereditary monarchy, hereditary ruler of the Ethiopian Empire, from at least the 13th century ...

, Tewodros II

, spoken = ; ''djānhoi'', lit. ''"O steemedroyal"''

, alternative = ; ''getochu'', lit. ''"Our master"'' (pl.)

Tewodros II ( gez, ዳግማዊ ቴዎድሮስ, baptized as Gebre Kidan; 1818 – 13 April 1868) was Emperor of Ethiopi ...

, held a British envoy and others hostage, and a force was sent to effect the release of the hostages. Stanley accompanied that force as a special correspondent of the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

''. Stanley's report on the Battle of Magdala

The Battle of Magdala was the conclusion of the British Expedition to Abyssinia fought in April 1868 between British and Abyssinian forces at Magdala, from the Red Sea coast. The British were led by Robert Napier, while the Abyssinians were ...

in 1868 was the first to be published. Subsequently, he was assigned to report on Spain's Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

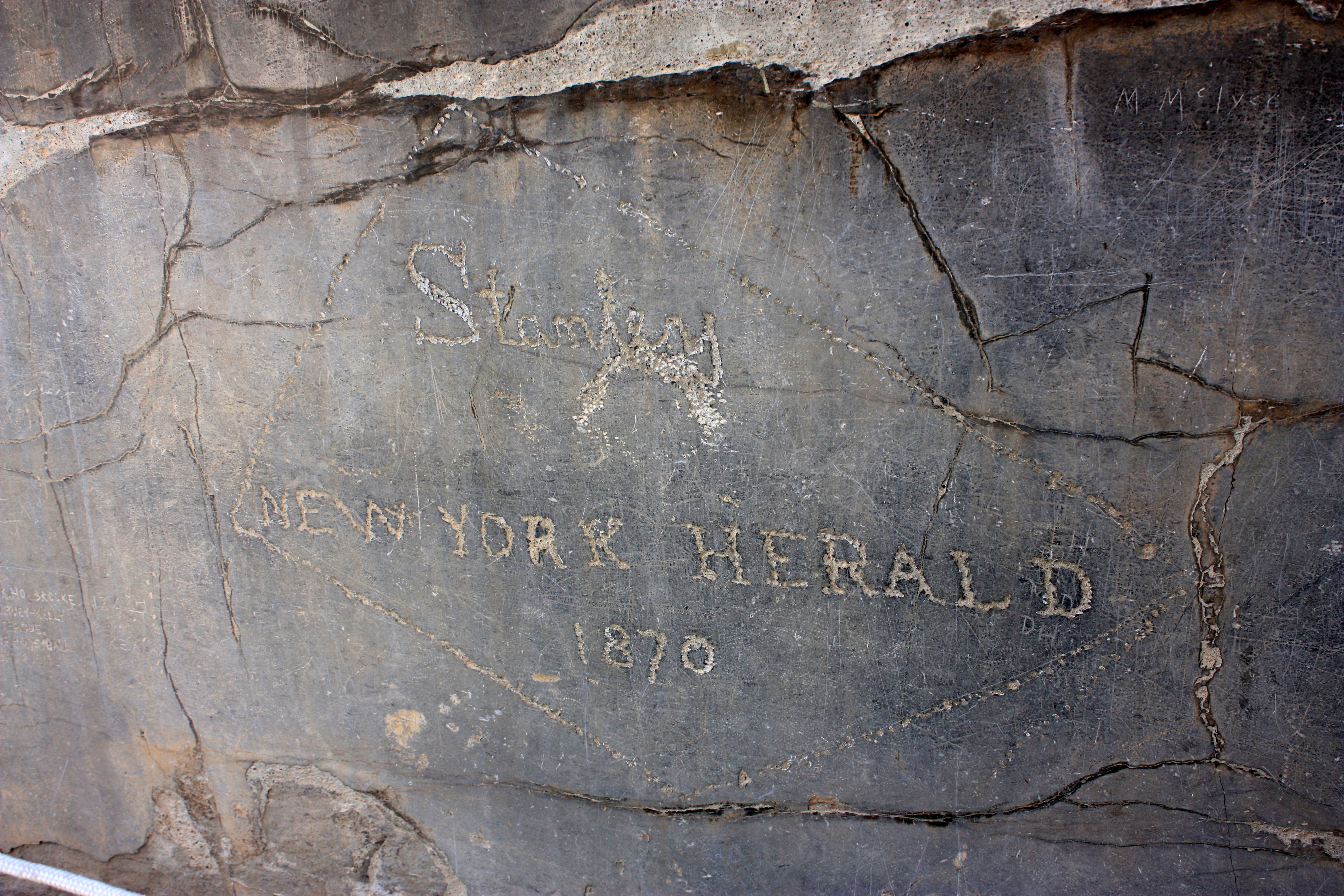

in 1868. In 1870, Stanley undertook several assignments for the ''Herald'' in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

and the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal mediterranean sea of the Atlantic Ocean lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bounded by Bulgaria, Georgia, Roma ...

region, visiting Egypt, Jerusalem, Constantinople, the Crimea, the Caucasus, Persia and India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, during which time he apparently carved his name into the stones of the ancient palace at Persepolis

, native_name_lang =

, alternate_name =

, image = Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.jpg

, image_size =

, alt =

, caption = Ruins of the Gate of All Nations, Persepolis.

, map =

, map_type ...

in Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

.

Finding David Livingstone

Stanley travelled to

Stanley travelled to Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islands ...

in March 1871, later claiming that he outfitted an expedition with 192 porters Porters may refer to:

* Porters, Virginia, an unincorporated community in Virginia, United States

* Porters, Wisconsin, an unincorporated community in Wisconsin, United States

* Porters Ski Area, a ski resort in New Zealand

* ''Porters'' (TV ser ...

. In his first dispatch to the ''New York Herald'', however, he stated that his expedition numbered only 111. This was in line with figures in his diaries. James Gordon Bennett Jr.

James Gordon Bennett Jr. (May 10, 1841May 14, 1918) was publisher of the ''New York Herald'', founded by his father, James Gordon Bennett Sr. (1795–1872), who emigrated from Scotland. He was generally known as Gordon Bennett to distinguish him ...

, publisher of the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'' and funder of the expedition, had delayed sending to Stanley the money he had promised, so Stanley borrowed money from the United States Consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states throug ...

.

During the expedition through the tropical forest, his thoroughbred stallion died within a few days after a bite from a tsetse fly

Tsetse ( , or ) (sometimes spelled tzetze; also known as tik-tik flies), are large, biting flies that inhabit much of tropical Africa. Tsetse flies include all the species in the genus ''Glossina'', which are placed in their own family, Glo ...

, many of his porters deserted, and the rest were decimated by tropical diseases.

Stanley found

Stanley found David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, and pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, an explorer in Africa, and one of the most popular British heroes of t ...

on 10 November 1871 in Ujiji

Ujiji is a historic town located in Kigoma-Ujiji District of Kigoma Region in Tanzania. The town is the oldest in western Tanzania. In 1900, the population was estimated at 10,000 and in 1967 about 41,000. The site is a registered National His ...

, near Lake Tanganyika

Lake Tanganyika () is an African Great Lake. It is the second-oldest freshwater lake in the world, the second-largest by volume, and the second-deepest, in all cases after Lake Baikal in Siberia. It is the world's longest freshwater lake. ...

in present-day Tanzania

Tanzania (; ), officially the United Republic of Tanzania ( sw, Jamhuri ya Muungano wa Tanzania), is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It borders Uganda to the north; Kenya to the northeast; Comoro Islands and ...

. He later claimed to have greeted him with the now-famous line, " Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" However, this line does not appear in his journal from the time—the two pages directly following the recording of his initial spotting of Livingstone were torn out of the journal at some point—and it is likely that Stanley simply embellished the pithy line sometime afterwards. Neither man mentioned it in any of the letters they wrote at this time, and Livingstone tended to instead recount the reaction of his servant, Susi, who cried out: "An Englishman coming! I see him!" The phrase is first quoted in a summary of Stanley's letters published by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' on 2 July 1872. Stanley biographer Tim Jeal

John Julian Timothy Jeal, known as Tim Jeal (born 27 January 1945 in London, England), is a British biographer of notable Victorians and is also a novelist. His publications include a memoir and biographies of David Livingstone (1973), Lord Ba ...

argued that the explorer invented it afterwards to help raise his standing because of "insecurity about his background", though ironically the phrase was mocked in the press for being absurdly formal for the situation.

The ''Herald''Preserving a calmness of exterior before the Arabs which was hard to simulate as he reached the group, Mr. Stanley said: – "Doctor Livingstone, I presume?" A smile lit up the features of the pale white man as he answered: "Yes, and I feel thankful that I am here to welcome you."Stanley joined Livingstone in exploring the region, finding that there was no connection between Lake Tanganyika and the Nile. On his return, he wrote a book about his experiences: ''How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa''.

First trans-Africa expedition

In 1874, the ''

In 1874, the ''New York Herald

The ''New York Herald'' was a large-distribution newspaper based in New York City that existed between 1835 and 1924. At that point it was acquired by its smaller rival the ''New-York Tribune'' to form the '' New York Herald Tribune''.

His ...

'' and the ''Daily Telegraph

Daily or The Daily may refer to:

Journalism

* Daily newspaper, newspaper issued on five to seven day of most weeks

* ''The Daily'' (podcast), a podcast by ''The New York Times''

* ''The Daily'' (News Corporation), a defunct US-based iPad new ...

'' financed Stanley on another expedition to Africa. His ambitious objective was to complete the exploration and mapping of the Central African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes ( sw, Maziwa Makuu; rw, Ibiyaga bigari) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. They include Lake Victoria, the second-largest fresh water lake in the ...

and rivers, in the process circumnavigating Lakes Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

and Tanganyika

Tanganyika may refer to:

Places

* Tanganyika Territory (1916–1961), a former British territory which preceded the sovereign state

* Tanganyika (1961–1964), a sovereign state, comprising the mainland part of present-day Tanzania

* Tanzania Main ...

and locating the source of the Nile

The Nile, , Bohairic , lg, Kiira , Nobiin language, Nobiin: Áman Dawū is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa and has historically been considered ...

. Between 1875 and 1876 Stanley succeeded in the first part of his objective, establishing that Lake Victoria had only a single outlet – the one discovered by John Hanning Speke

Captain John Hanning Speke (4 May 1827 – 15 September 1864) was an English explorer and officer in the Indian Army (1895–1947), British Indian Army who made three exploratory expeditions to Africa. He is most associated with the search ...

on 21 July 1862 and named Ripon Falls Ripon Falls at the northern end of Lake Victoria in Uganda was formerly considered the source of the river Nile. In 1862–3 John Hanning Speke

Captain John Hanning Speke (4 May 1827 – 15 September 1864) was an English explorer and offi ...

. If this was not the Nile's source, then the separate massive northward flowing river called by Livingstone, the Lualaba, and mapped by him in its upper reaches, might flow on north to connect with the Nile via Lake Albert and thus be the primary source.

Nyangwe

Nyangwe is a town in Kasongo, Maniema on the right bank of the Lualaba River, Lualaba in the Democratic Republic of Congo (territory of Kasongo). It was an important hub for the Arabs for trade goods like ivory, gold, iron & slaves: it was one of ...

, the point where Livingstone had left it in July 1871. Between November 1876 and August 1877, Stanley and his men navigated the Lualaba up to and beyond the point where it turned sharply westward, away from the Nile, identifying itself as the Congo River

The Congo River ( kg, Nzâdi Kôngo, french: Fleuve Congo, pt, Rio Congo), formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the second largest river in the world by discharge ...

. Having succeeded with this second objective, they then traced the river to the sea. During this expedition, Stanley used sectional boats and dug-out canoes to pass the large cataracts that separated the Congo into distinct tracts. These boats were transported around the rapids before being rebuilt to travel on the next section of river. In passing the rapids many of his men were drowned, including his last white colleague, Frank Pocock. Stanley and his men reached the Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

outpost of Boma, around from the mouth of the Congo River on the Atlantic Ocean, after 999 days on 9 August 1877. Muster lists and Stanley's diary (12 November 1874) show that he started with 228 people and reached Boma with 114 survivors, with he being the only European left alive out of four. In Stanley's ''Through the Dark Continent'' (1878) (in which he coined the term "Dark Continent" for Africa), Stanley said that his expedition had numbered 356, the exaggeration detracting from his achievement.

Stanley attributed his success to his leading African porters, saying that his success was "all due to the pluck and intrinsic goodness of 20 men ... take the 20 out and I could not have proceeded beyond a few days' journey". Professor James Newman has written that "establishing the connection between the Lualaba and Congo Rivers and locating the source of the Victoria Nile" justified him (Newman) in stating that: "In terms of exploration and discovery as defined in nineteenth-century Europe, he (Stanley) clearly stands at the top."

Claiming the Congo for King Leopold II

Stanley was approached by King Leopold II of the Belgians, the monarch who had already established the

Stanley was approached by King Leopold II of the Belgians, the monarch who had already established the International African Association

The International African Association (in full, "International Association for the Exploration and Civilization of Central Africa"; in French ''Association Internationale Africaine,'' and in full ''Association Internationale pour l'Exploration et ...

(a front organization for the later International Association of the Congo

The International Association of the Congo (french: Association internationale du Congo), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Con ...

) at the Brussels Geographic Conference {{Expand French, Conférence géographique de Bruxelles, date=August 2022

The Brussels Geographic Conference was held in Brussels, Belgium in September 1876 at the request of King Leopold II of Belgium. At the conference were invited nearly forty we ...

of 1876. Stanley first hoped to continue his pioneering work in Africa under the British flag. But neither the Foreign Office nor Edward, the Prince of Wales, felt called to receive Stanley after the many rumors of his looting and killing in the interior of the African continent. Leopold II eagerly received a disenchanted Stanley at his palace in June 1878, and signed a contract with him.

Stanley as Leopold's agent

Stanley, much more familiar with the rigors of the African climate and the complexities of local politics than

Stanley, much more familiar with the rigors of the African climate and the complexities of local politics than Leopold

Leopold may refer to:

People

* Leopold (given name)

* Leopold (surname)

Arts, entertainment, and media Fictional characters

* Leopold (''The Simpsons''), Superintendent Chalmers' assistant on ''The Simpsons''

* Leopold Bloom, the protagonist o ...

(who never in his whole life set foot in the Congo), persuaded his patron that the first step should be the construction of a wagon trail around the Congo rapids and a chain of trading stations on the river. Leopold agreed, and in deepest secrecy, Stanley signed a five-year contract at a salary of £1,000 a year and set off to Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islands ...

under an assumed name. To avoid discovery, materials and workers were shipped in by various roundabout routes, and communications between Stanley and Leopold were entrusted to Colonel Maximilien Strauch

Colonel Maximilien Charles Ferdinand Strauch (Lomprez, 4 October 1829 – Beez, 7 June 1911) was a Belgian officer who played a role in the colonization of the Congo. He was a trusted advisor of King Leopold II of Belgium, who entrusted him with ...

.

In 1879, Stanley left for Africa for his first mission under Leopold's orders. King Leopold II gave Stanley clear instructions: "''It is not about Belgian colonies. It is about establishing a new state that is as large as possible and about its governance. It should be clear that in this project there can be no question of granting the Negroes the slightest form of political power. That would be ridiculous. The whites, who lead the posts, have all the power.''"

Stanley described in writings his dismay with the terrible scenes taking place in Congo. He also reported of atrocities and cannibalism come in. At the same time, his 'findings' conveyed an idea that the dark continent must submit, willingly or otherwise. Stanley's writings show that he, too, held this view. ''"Only by proving that we are superior to the savages, not only through our power to kill them but through our entire way of life, can we control them as they are now, in their present stage; it is necessary for their own well-being, even more than ours."''

Unexpectedly, France sent its own expedition to the

In 1879, Stanley left for Africa for his first mission under Leopold's orders. King Leopold II gave Stanley clear instructions: "''It is not about Belgian colonies. It is about establishing a new state that is as large as possible and about its governance. It should be clear that in this project there can be no question of granting the Negroes the slightest form of political power. That would be ridiculous. The whites, who lead the posts, have all the power.''"

Stanley described in writings his dismay with the terrible scenes taking place in Congo. He also reported of atrocities and cannibalism come in. At the same time, his 'findings' conveyed an idea that the dark continent must submit, willingly or otherwise. Stanley's writings show that he, too, held this view. ''"Only by proving that we are superior to the savages, not only through our power to kill them but through our entire way of life, can we control them as they are now, in their present stage; it is necessary for their own well-being, even more than ours."''

Unexpectedly, France sent its own expedition to the Congo Basin

The Congo Basin (french: Bassin du Congo) is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It con ...

. Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza

Pietro Paolo Savorgnan di Brazzà, later known as Pierre Paul François Camille Savorgnan de Brazza; 26 January 1852 – 14 September 1905), was an Italian-born, naturalized French explorer. With his family's financial help, he explored the Ogoou� ...

undermined Stanley's mission by concluding contracts himself with native heads of state. The creation of a station that would later be called Brazzaville

Brazzaville (, kg, Kintamo, Nkuna, Kintambo, Ntamo, Mavula, Tandala, Mfwa, Mfua; Teke: ''M'fa'', ''Mfaa'', ''Mfa'', ''Mfoa''Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, ''Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture'', ABC-CLI ...

could not be prevented. King Leopold was furious writing angrily to Strauch: "''The terms of the treaties Stanley has made with native chiefs do not satisfy me. There must at least be an added article to the effect that they delegate to us their sovereign rights ... the treaties must be as brief as possible and in a couple of articles must grant us everything.''"

Since everything in Central Africa was about the balance of power between the superpowers, Leopold thought about his next moves and sent an envoy to Berlin to press for a conference

A conference is a meeting of two or more experts to discuss and exchange opinions or new information about a particular topic.

Conferences can be used as a form of group decision-making, although discussion, not always decisions, are the main p ...

. Leopold wanted the International Association of the Congo

The International Association of the Congo (french: Association internationale du Congo), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Con ...

boundaries drawn by Stanley to be officially confirmed, thus giving the Association an official status.

On 26 February 1885, the Berlin Act was signed. The Act regulated an immense free trade zone in the Congo Basin and made it a neutral territory. Furthermore, the Act declared war on slavery. The act contained only one article that Leopold disliked: Article 17 gave the superpowers the right to establish an international commission to supervise the freedom of trade and navigation in Congo. As a result, Leopold wouldn't be able to collect customs duties on the Congo River

In 1890, on the 25th anniversary of Leopold's reign as Belgian monarch, Stanley was taken from one banquet hall to another, proclaimed a hero. Leopold honored him with the Order of Leopold. Together they examined the entire Congolese situation. The key question was how the Free State could become profitable. Stanley pointed out to the monarch, among other things, the potential of rubber mining. Stanley wrote: ''"You can find it on almost any tree. As we made our way through the forest, it was literally raining rubber juice. Our clothes were full of it. The Congo has so many tributaries that a well-organized company can easily extract a few tons of rubber per year here. You only have to sail up such a river and the branches with rubber hang almost up to your ship."''

In 1891, rubber extraction was divided among concessionaires. This soon led to abuses, when the switch was made to "forced labour".

In later years, Stanley would write that the most vexing part of his duties was not the work itself but was keeping order in the ill-assorted collection of white men he had brought with him as overseers and officers, who squabbled constantly over small matters of rank or status. "Almost all of them", he wrote, "clamored for expenses of all kinds, which included ... wine, tobacco, cigars, clothes, shoes, board and lodging, and certain nameless extravagances."

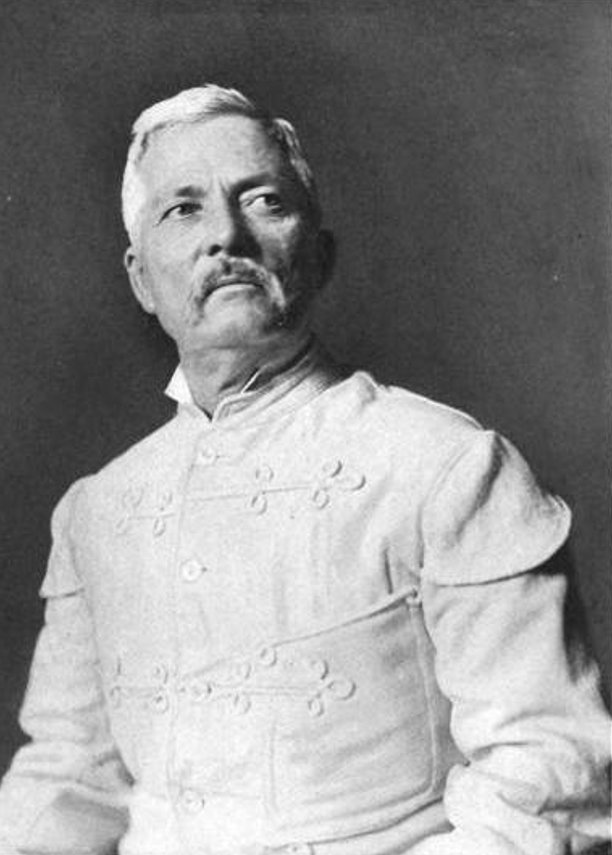

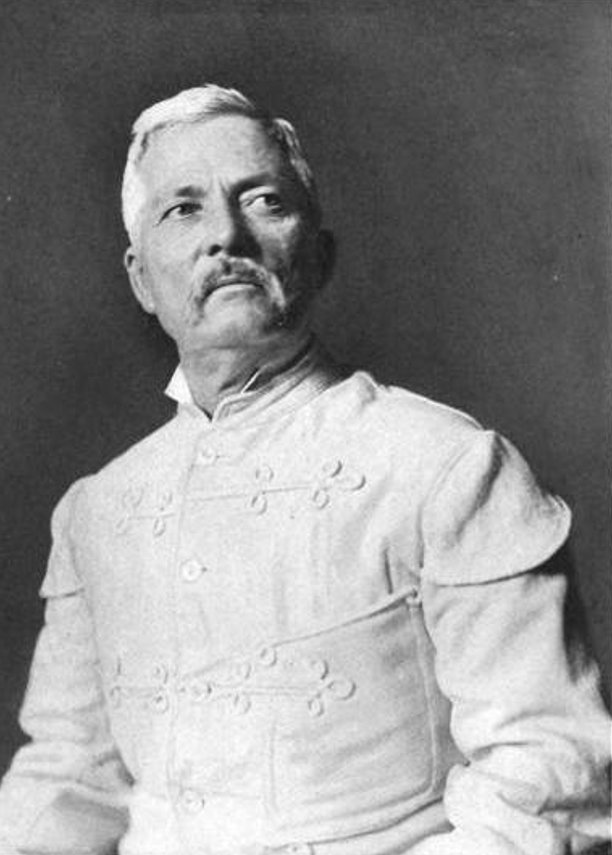

Dealings with Zanzibari slave traders

Tippu Tip

Tippu Tip, or Tippu Tib (1832 – June 14, 1905), real name Ḥamad ibn Muḥammad ibn Jumʿah ibn Rajab ibn Muḥammad ibn Saʿīd al Murjabī ( ar, حمد بن محمد بن جمعة بن رجب بن محمد بن سعيد المرجبي), ...

, the most powerful of Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islands ...

's slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

traders of the 19th century, was well known to Stanley, as was the social chaos and devastation brought by slave-hunting. It had only been through Tippu Tip's help that Stanley had found Livingstone, who had survived years on the Lualaba under Tippu Tip's friendship. Now, Stanley discovered that Tippu Tip's men had reached still further west in search of fresh populations to enslave.

Four years earlier, the Zanzibaris had thought the Congo deadly and impassable and warned Stanley not to attempt to go there, but when Tippu Tip learned in Zanzibar that Stanley had survived, he was quick to act. Villages throughout the region had been burned and depopulated. Tippu Tip had raided 118 villages, killed 4,000 Africans, and, when Stanley reached his camp, had 2,300 slaves, mostly young women and children, in chains ready to transport halfway across the continent to the markets of Zanzibar.

Having found the new ruler of the Upper Congo, Stanley had no choice but to negotiate an agreement with him, to stop Tip coming further downstream and attacking Leopoldville,

Having found the new ruler of the Upper Congo, Stanley had no choice but to negotiate an agreement with him, to stop Tip coming further downstream and attacking Leopoldville, Kinshasa

Kinshasa (; ; ln, Kinsásá), formerly Léopoldville ( nl, Leopoldstad), is the capital and largest city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Once a site of fishing and trading villages situated along the Congo River, Kinshasa is now one o ...

and other stations. To achieve this, he had to allow Tip to build his final river station just below Stanley Falls, which prevented vessels from sailing further upstream. At the end of his physical resources, Stanley returned home, to be replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Francis de Winton, a former British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer.

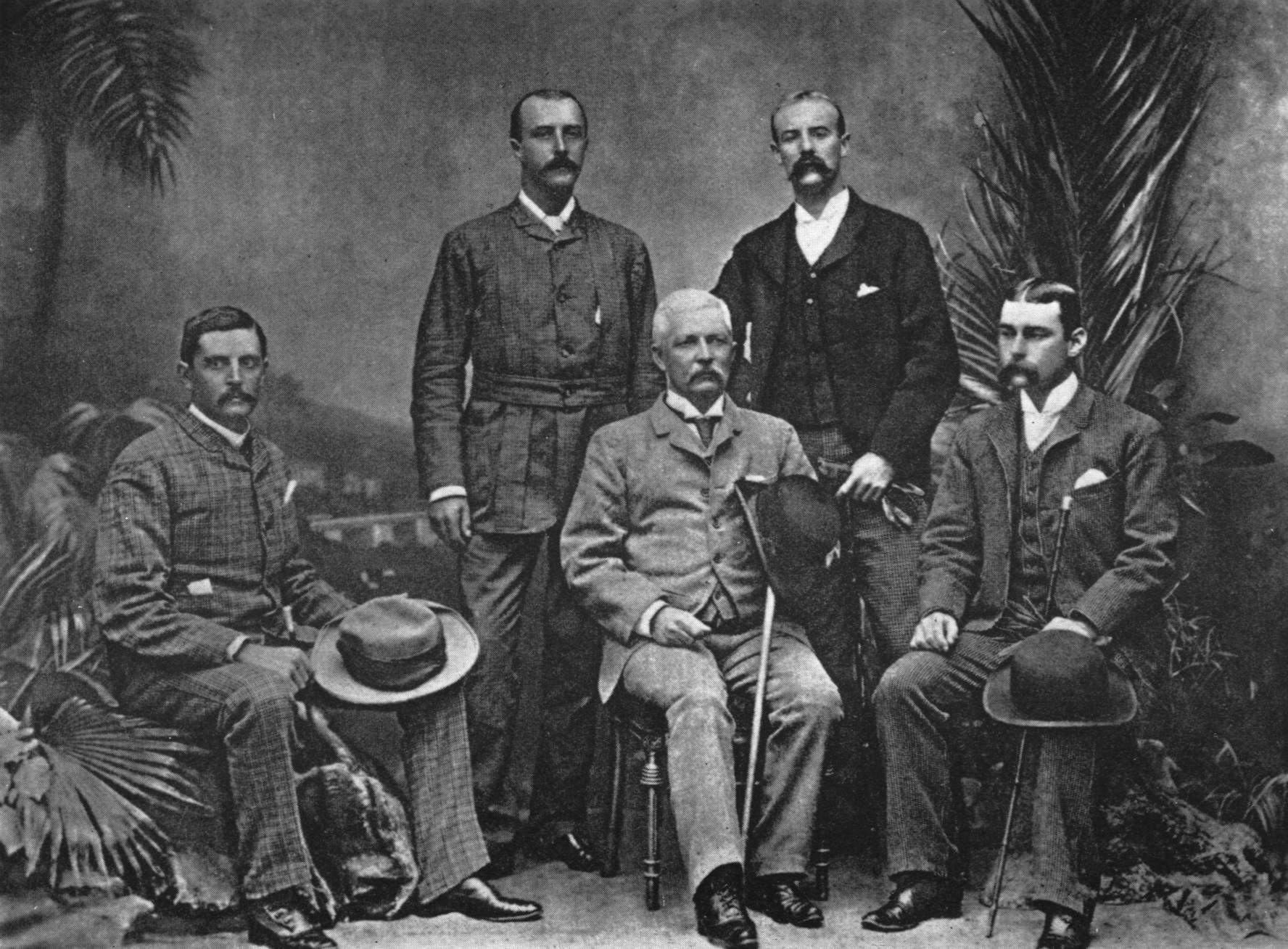

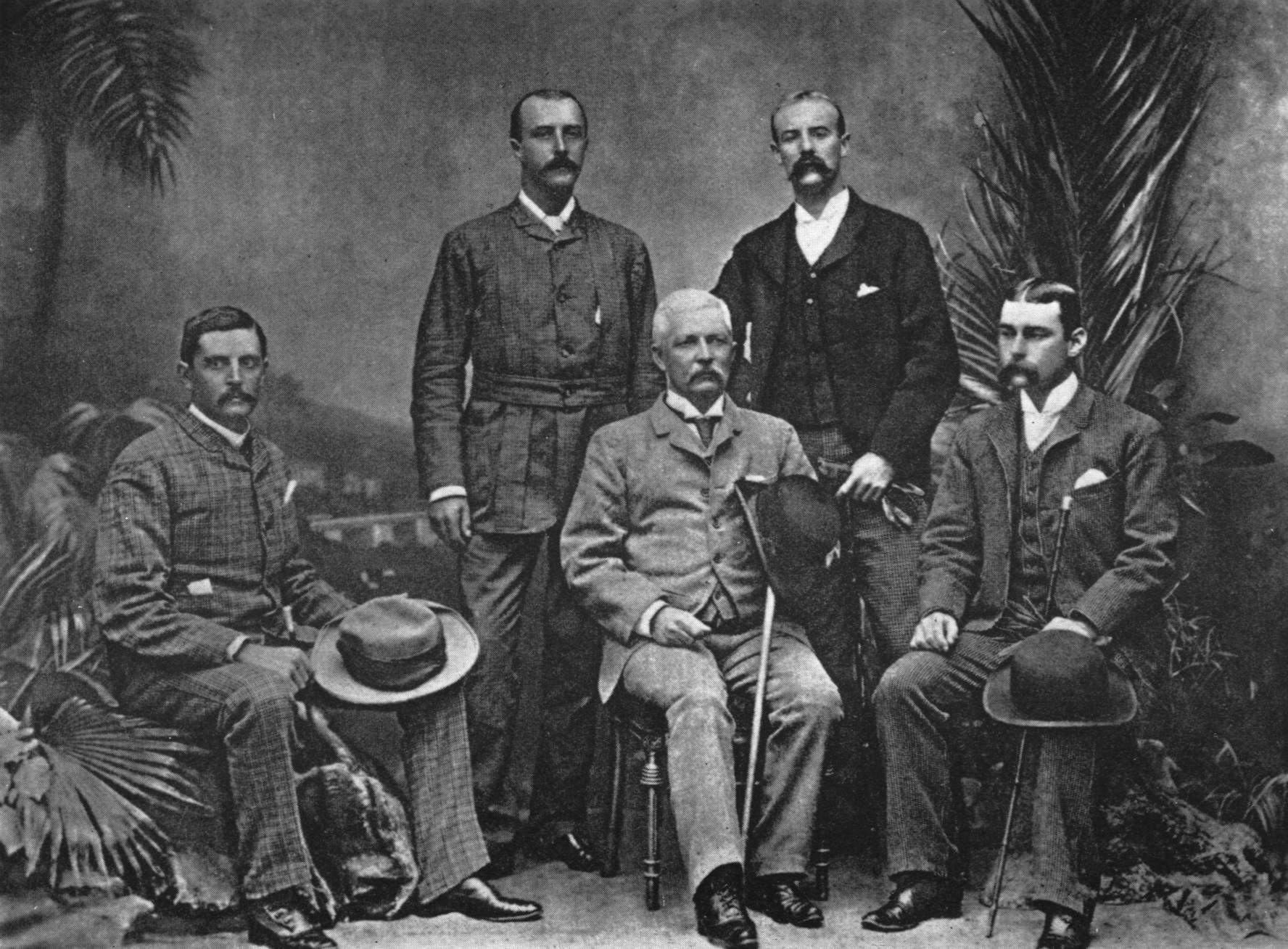

Emin Pasha Relief Expedition

In 1886, Stanley led theEmin Pasha Relief Expedition

The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition of 1886 to 1889 was one of the last major European expeditions into the interior of Africa in the nineteenth century, ostensibly to the relief of Emin Pasha, General Charles Gordon's besieged governor of Equato ...

to "rescue" Emin Pasha

185px, Schnitzer in 1875

Mehmed Emin Pasha (born Isaak Eduard Schnitzer, baptized Eduard Carl Oscar Theodor Schnitzer; March 28, 1840 – October 23, 1892) was an Ottoman physician of German Jewish origin, naturalist, and governor of the Egyp ...

, the governor of Equatoria

Equatoria is a region of southern South Sudan, along the upper reaches of the White Nile. Originally a province of Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, it also contained most of northern parts of present-day Uganda, including Lake Albert and West Nile. It ...

in the southern Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

, who was threatened by Mahdist forces. King Leopold II demanded that Stanley take the longer route via the Congo River, hoping to acquire more territory and perhaps even Equatoria After immense hardships and great loss of life, Stanley met Emin in 1888, charted the Ruwenzori Range

The Ruwenzori, also spelled Rwenzori and Rwenjura, are a range of mountains in eastern equatorial Africa, located on the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The highest peak of the Ruwenzori reaches , and the range' ...

and Lake Edward

Lake Edward (locally Rwitanzigye or Rweru) is one of the smaller African Great Lakes. It is located in the Albertine Rift, the western branch of the East African Rift, on the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Uganda, ...

, and emerged from the interior with Emin and his surviving followers at the end of 1890. But this expedition tarnished Stanley's name because of the conduct of the other Europeans on the expedition. Army Major Edmund Musgrave Barttelot was killed by an African porter after behaving with extreme cruelty. James Sligo Jameson, heir to Irish whiskey

Irish whiskey ( ga, Fuisce or ''uisce beatha'') is whiskey made on the island of Ireland. The word 'whiskey' (or whisky) comes from the Irish , meaning ''water of life''. Irish whiskey was once the most popular spirit in the world, though a lo ...

manufacturer Jameson's, bought an 11-year-old girl and offered her to cannibals to document and sketch how she was cooked and eaten. Stanley found out only when Jameson had died of fever.

The spread of

The spread of sleeping sickness

African trypanosomiasis, also known as African sleeping sickness or simply sleeping sickness, is an insect-borne parasitic infection of humans and other animals. It is caused by the species ''Trypanosoma brucei''. Humans are infected by two typ ...

across areas of central and eastern Africa that were previously free of the disease has been attributed to this expedition, but this hypothesis has been disputed. Sleeping sickness had been endemic in these regions for generations and then flared into epidemics as colonial trade increased trade throughout Africa during the ensuing decades.

In a number of publications made after the expedition, Stanley asserts that the purpose of the effort was singular; to offer relief to Emin Pasha. For example, he writes the following while explaining the final route decision.

The advantages of the Congo route were about five hundred miles shorter land journey, and less opportunities for deserting. It also quieted the fears of the French and Germans that, behind this professedly humanitarian quest, we might have annexation projects.However, Stanley's other writings point to a secondary goal which was precisely territorial annexation. He writes in his book on the expedition about his meeting with the Sultan of Zanzibar, when he arrived there at the start of the expedition, and a certain matter that was discussed at that meeting. At first, he is not explicit on the agenda but it is clear enough.

We then entered heartily into our business; how absolutely necessary it was that he should promptly enter into an agreement with the English within the limits assigned by Anglo-German treaty. It would take too long to describe the details of the conversation, but I obtained from him the answer needed.A few pages further in the same book, Stanley explains what the matter was about and this time, he makes it clear that indeed, it had to do with annexation.

I have settled several little commissions at Zanzibar satisfactorily. One was to get the Sultan to sign the concessions which Mackinnon tried to obtain a long time ago. As the Germans have magnificent territory east of Zanzibar, it was but fair that England should have some portion for the protection she has accorded to Zanzibar since 1841 . ... The concession that we wished to obtain embraced a portion of East African coast, of whichMombasa Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of the British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital city status. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...andMalindi Malindi is a town on Malindi Bay at the mouth of the Sabaki River, lying on the Indian Ocean coast of Kenya. It is 120 kilometres northeast of Mombasa. The population of Malindi was 119,859 as of the 2019 census. It is the largest urban centre ...were the principal towns. For eight years, to my knowledge, the matter had been placed before His Highness, but the Sultan's signature was difficult to obtain.

The records at the National Archives at Kew, London, offer an even deeper insight and show that annexation was a purpose he had been aware of for the expedition. This is because there are a number of treaties curated there (and gathered by Stanley himself from what is present-day

The records at the National Archives at Kew, London, offer an even deeper insight and show that annexation was a purpose he had been aware of for the expedition. This is because there are a number of treaties curated there (and gathered by Stanley himself from what is present-day Uganda

}), is a landlocked country in East Africa

East Africa, Eastern Africa, or East of Africa, is the eastern subregion of the African continent. In the United Nations Statistics Division scheme of geographic regions, 10-11-(16*) territor ...

during the Emin Pasha Expedition), ostensibly gaining British protection for a number of African chiefs. Amongst these were a number that have long been identified as possible frauds. A good example is treaty number 56, supposedly agreed upon between Stanley and the people of "Mazamboni, Katto, and Kalenge". These people had signed over to Stanley, "the Sovereign Right and Right of Government over our country for ever in consideration of value received and for the protection he has accorded us and our Neighbours against KabbaRega and his Warasura."

Later years

On his return to Europe, Stanley married Welsh artistDorothy Tennant

Dorothy Tennant (22 March 1855 – 5 October 1926) was an English painter of the Victorian era neoclassicism. She was married to the explorer Henry Morton Stanley.

Biography

Tennant was born in Russell Square, London, the second daughter of ...

. They adopted a child named Denzil, who was the son of one of Stanley's first cousins, though Stanley concealed this fact from the public and possibly even from Dorothy. Denzil later donated around 300 items to the Stanley archives at the Royal Museum of Central Africa

The Royal Museum for Central Africa or RMCA ( nl, Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Afrika or KMMA; french: Musée royal de l'Afrique centrale or MRAC; german: Königliches Museum für Zentralafrika or KMZA), also officially known as the AfricaMuse ...

in Tervuren

Tervuren () is a municipality in the province of Flemish Brabant, in Flanders, Belgium. The municipality comprises the villages of Duisburg, Tervuren, Vossem and Moorsel. On January 1, 2006, Tervuren had a total population of 20,636. The total a ...

, Belgium in 1954. He died in 1959.

Mainly at his wife's behest, Stanley entered Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as a Liberal Unionist

The Liberal Unionist Party was a British political party that was formed in 1886 by a faction that broke away from the Liberal Party. Led by Lord Hartington (later the Duke of Devonshire) and Joseph Chamberlain, the party established a political ...

member for Lambeth North, serving from 1895 to 1900. He disliked politics and made little impression on Parliament. He became Sir Henry Morton Stanley when he was made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

The Most Honourable Order of the Bath is a British order of chivalry founded by George I of Great Britain, George I on 18 May 1725. The name derives from the elaborate medieval ceremony for appointing a knight, which involved Bathing#Medieval ...

in the 1899 Birthday Honours

The Queen's Birthday Honours 1899 were announced on 3 June 1899 in celebration of the birthday of Queen Victoria. The list included appointments to various orders and honours of the United Kingdom and British India.

The list was published in '' ...

, in recognition of his service to the British Empire in Africa. In 1890, he was given the Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold by King Leopold II.

Stanley died at his home at 2 Richmond Terrace, Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A roads in Zone 3 of the Great Britain numbering scheme, A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea, London, Chelsea. It is the main ...

, London on 10 May 1904. At his funeral, he was eulogised by Daniel P. Virmar. His grave is in the churchyard of St Michael and All Angels' Church in Pirbright

Pirbright ( ) is a village in Surrey, England. Pirbright is in the borough of Guildford and has a civil parish council covering the traditional boundaries of the area. Pirbright contains one buffered sub-locality, Stanford Common near the nati ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

, marked by a large piece of granite inscribed with the words "Henry Morton Stanley, Bula Matari, 1841–1904, Africa". Bula Matari translates as "Breaker of Rocks" or "Breakstones" in Kongo

Congo or The Congo may refer to either of two countries that border the Congo River in central Africa:

* Democratic Republic of the Congo, the larger country to the southeast, capital Kinshasa, formerly known as Zaire, sometimes referred to a ...

and was Stanley's name among locals in Congo. It can be translated as a term of endearment for, as the leader of Leopold's expedition, he commonly worked with the labourers breaking rocks with which they built the first modern road along the Congo River

The Congo River ( kg, Nzâdi Kôngo, french: Fleuve Congo, pt, Rio Congo), formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the second largest river in the world by discharge ...

. Author Adam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild (; born October 5, 1942) is an American author, journalist, historian and lecturer. His best-known works include ''King Leopold's Ghost'' (1998), '' To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914–1918'' (2011), ''Bur ...

suggested that Stanley understood it as a heroic epithet, but there is evidence that Nsakala, the man who coined it, had meant it humorously.

Controversies

Overview

Having survived for ten years of his childhood in theworkhouse

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

at St Asaph

St Asaph (; cy, Llanelwy "church on the Elwy") is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and community (Wales), community on the River Elwy in Denbighshire, Wales. In the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 Census it had a population of 3,355 ...

, it is postulated that he needed as a young man to be thought of as harder and more formidable than other explorers. This made him exaggerate punishments and hostile encounters. It was a serious error of judgement for which his reputation continues to pay a heavy price. In the conclusion to his account of a fight with a fellow boy while in the workhouse, Stanley remarked, "Often since have I learned how necessary is the application of force for the establishment of order. There comes a time when pleading is of no avail." He was accused of indiscriminate cruelty against Africans by contemporaries, which included men who served under him or otherwise had first-hand information. Stanley himself acknowledged, "Many people have called me hard, but they are always those whose presence a field of work could best dispense with, and whose nobility is too nice to be stained with toil".

About society women, Stanley wrote that they were "toys to while slow time" and "trifling human beings". When he met the American journalist and traveller May Sheldon

Mary French Sheldon (10 May 1847 – 10 February 1936), as author May French Sheldon, was an American author and explorer.

Early years and education

Mary French was born May 10, 1847, at Bridgewater, Pennsylvania. Her father was Joseph French, ...

, he was attracted because she was a modern woman who insisted on serious conversation and not social chit-chat. "She soon lets you know that chaff won't do", he wrote. The authors of the book ''The Congo: Plunder and Resistance'' tried to argue that Stanley had "a pathological fear of women, an inability to work with talented co-workers, and an obsequious love of the aristocratic rich", This is not only at odds with his opinions about society women, but Stanley's intimate correspondence in the Royal Museum of Central Africa

The Royal Museum for Central Africa or RMCA ( nl, Koninklijk Museum voor Midden-Afrika or KMMA; french: Musée royal de l'Afrique centrale or MRAC; german: Königliches Museum für Zentralafrika or KMZA), also officially known as the AfricaMuse ...

, between him and his two fiancées, Katie Gough Roberts and Alice Pike, as well as between him and the American journalist May Sheldon

Mary French Sheldon (10 May 1847 – 10 February 1936), as author May French Sheldon, was an American author and explorer.

Early years and education

Mary French was born May 10, 1847, at Bridgewater, Pennsylvania. Her father was Joseph French, ...

, and between him and his wife Dorothy Tennant

Dorothy Tennant (22 March 1855 – 5 October 1926) was an English painter of the Victorian era neoclassicism. She was married to the explorer Henry Morton Stanley.

Biography

Tennant was born in Russell Square, London, the second daughter of ...

, shows that he enjoyed close relationships with those women, but both Roberts and Pike

Pike, Pikes or The Pike may refer to:

Fish

* Blue pike or blue walleye, an extinct color morph of the yellow walleye ''Sander vitreus''

* Ctenoluciidae, the "pike characins", some species of which are commonly known as pikes

* ''Esox'', genus of ...

ultimately rejected him when he refused to abandon his protracted travels.

When Stanley married Dorothy

Dorothy may refer to:

*Dorothy (given name), a list of people with that name.

Arts and entertainment

Characters

*Dorothy Gale, protagonist of ''The Wonderful Wizard of Oz'' by L. Frank Baum

* Ace (''Doctor Who'') or Dorothy, a character playe ...

, he invited his friend, Arthur Mounteney Jephson, to visit while they were on their honeymoon. Dr. Thomas Parke also came because Stanley was seriously ill at the time. Stanley's good relations with these two colleagues from the Emin Pasha Expedition could possibly be seen as demonstrating that he could get along with colleagues.

General opinion about African people

In ''Through the Dark Continent'', Stanley observed the peoples of the region, and wrote that "the savage only respects force, power, boldness, and decision". Stanley further wrote: 'If Europeans will only ... study human nature in the vicinity of Stanley Pool (Kinshasa), they will go home thoughtful men, and may return again to this land to put to good use the wisdom they should have gained ... during their peaceful sojourn.'

In ''How I Found Livingstone'', he wrote that he was "prepared to admit any black man possessing the attributes of true manhood, or any good qualities ... to a brotherhood with myself."

Stanley insulted and shouted at

In ''Through the Dark Continent'', Stanley observed the peoples of the region, and wrote that "the savage only respects force, power, boldness, and decision". Stanley further wrote: 'If Europeans will only ... study human nature in the vicinity of Stanley Pool (Kinshasa), they will go home thoughtful men, and may return again to this land to put to good use the wisdom they should have gained ... during their peaceful sojourn.'

In ''How I Found Livingstone'', he wrote that he was "prepared to admit any black man possessing the attributes of true manhood, or any good qualities ... to a brotherhood with myself."

Stanley insulted and shouted at William Grant Stairs

William Grant Stairs (1 July 1863 – 9 June 1892) was a Canadian-British explorer, soldier, and adventurer who had a leading role in two of the most controversial expeditions in the Scramble for Africa.

Education

Born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, ...

and Arthur Jephson for mistreating the Wangwana. He described the history of Boma as "two centuries of pitiless persecution of black men by sordid whites". He also wrote about what he thought was the superior beauty of black people in comparison with whites. According to Jeal, Stanley was not a racist, unlike his contemporaries Sir Richard Burton

Sir Richard Francis Burton (; 19 March 1821 – 20 October 1890) was a British explorer, writer, orientalist scholar,and soldier. He was famed for his travels and explorations in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, as well as his extraordinary kn ...

and Sir Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker, KCB, FRS, FRGS (8 June 1821 – 30 December 1893) was an English explorer, officer, naturalist, big game hunter, engineer, writer and abolitionist. He also held the titles of Pasha and Major-General in the Ottoman ...

.

Opinion about mixed African-Arab peoples

The Wangwana of Zanzibar were of mixed Arabian and African ancestry: "Africanized Arabs", in Stanley's words. They became the backbone of all his major expeditions and were referred to as "his dear pets" by sceptical young officers on the Emin Pasha Expedition, who resented their leader for favouring the Wangwana above themselves. "All are dear to me", Stanley told William Grant Stairs and Arthur Jephson, "who do their duty and the Zanzibaris have quite satisfied me on this and on previous expeditions." Stanley came to think of an individual Wangwana as "superior in proportion to his wages to ten Europeans". When Stanley first met a group of his Wangwana assistants, he was surprised: "They were an exceedingly fine looking body of men, far more intelligent in appearance than I could ever have believed African barbarians could be". On the other hand, in one of his books, Stanley said about mixed Afro-Arab people: "For the half-castes I have great contempt. They are neither black nor white, neither good nor bad, neither to be admired nor hated. They are all things, at all times. ... If I saw a miserable, half-starved negro, I was always sure to be told, he belonged to a half-caste. Cringing and hypocritical, cowardly and debased, treacherous and mean ... this syphilitic, blear-eyed, pallid-skinned, abortion of an Africanized Arab."Accounts of cruel treatment toward African people

TheBritish House of Commons

The House of Commons is the lower house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the upper house, the House of Lords, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England.

The House of Commons is an elected body consisting of 650 mem ...

appointed a committee to investigate missionary reports of Stanley's mistreatment of native populations in 1871, which was likely secured by Horace Waller, a member on the committee of the Anti-slavery Society and fellow of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

. The British vice consul in Zanzibar, John Kirk (Waller's brother-in-law) conducted the investigation. Stanley was charged with excessive violence, wanton destruction, the selling of labourers into slavery, the sexual exploitation of native women and the plundering of villages for ivory and canoes. Kirk

Kirk is a Scottish and former Northern English word meaning "church". It is often used specifically of the Church of Scotland. Many place names and personal names are also derived from it.

Basic meaning and etymology

As a common noun, ''kirk'' ...

's report to the British Foreign Office

The Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) is a department of the Government of the United Kingdom. Equivalent to other countries' ministries of foreign affairs, it was created on 2 September 2020 through the merger of the Foreign ...

was never published, but in it, he claimed: "If the story of this expedition were known it would stand in the annals of African discovery unequalled for the reckless use of power that modern weapons placed in his hands over natives who never before heard a gun fired." When Kirk was appointed to investigate reports of brutality against Stanley, he was delighted because he had hated Stanley for almost a decade. Firstly, for having publicly exposed him (Kirk) for having failed to send provisions to Dr Livingstone from Zanzibar during the late 1860s; secondly, because Stanley had revealed in the press that Kirk had sent slaves to David Livingstone as porters, rather than the free men Livingstone had made very plain he wanted. Kirk was related to Horace Waller by marriage; and so Waller also hated Stanley on Kirk's behalf. He used his membership of the executive committee of the Universities Mission to Central Africa to persuade the Rev. J.P. Farler (a missionary in East Africa) to name Stanley's assistants who might provide evidence against the explorer and be prepared to be interviewed by Dr Kirk in Zanzibar. An American merchant in Zanzibar, Augustus Sparhawk, wrote that several of Stanley's African assistants, including Manwa Sera –– "a big rascal and too fond of money" –– had been bribed to tell Kirk what he wanted to hear. Stanley was accused, in Kirk's report, of cruelty to his Wangwana carriers and guards whom he idolized and who re-enlisted with him again and again. He wrote to the owner of the ''Daily Telegraph'', insisting that he (Lawson) force the British government

ga, Rialtas a Shoilse gd, Riaghaltas a Mhòrachd

, image = HM Government logo.svg

, image_size = 220px

, image2 = Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom (HM Government).svg

, image_size2 = 180px

, caption = Royal Arms

, date_es ...

to send a warship to take the Wangwana home to Zanzibar and to pay all their back wages. If a ship was not sent, they would die on their overland journey home. The ship was sent. Stanley's hatred of the promiscuity that had caused his illegitimacy and his legendary shyness with women, made the Kirk report's claim that he had accepted an African mistress offered to him by Kabaka Mutesa exceedingly implausible. Both Stanley and his colleague, Frank Pocock, loathed slavery and the slave trade and wrote about this loathing in letters and diaries at this time, which speaks against the likelihood that they sold their own men. The report was never shown to Stanley, so he had been unable to defend himself.

In a letter to the Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

in the 1870s, Conservative MP and treasurer of the Aborigines' Protection Society

The Aborigines' Protection Society (APS) was an international human rights organisation founded in 1837,

...

, Sir Robert Fowler, who believed Kirk's report and refused to "whitewash Stanley", insisted that his "heartless butchery of unfortunate natives has brought dishonour on the British flag and must have rendered the course of future travellers more perilous and difficult."

General ...

Charles George Gordon

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Charles George Gordon Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and ...

remarked in a letter to Richard Francis Burton

Sir Richard Francis Burton (; 19 March 1821 – 20 October 1890) was a British explorer, writer, orientalist scholar,and soldier. He was famed for his travels and explorations in Asia, Africa, and the Americas, as well as his extraordinary kn ...

that Stanley shared Samuel Baker

Sir Samuel White Baker, Order of the Bath, KCB, Royal Society, FRS, Royal Geographical Society, FRGS (8 June 1821 – 30 December 1893) was an English List of explorers, explorer, Officer (armed forces), officer, naturalist, big game hunter, ...

's tendency to write openly about deploying firearms against Africans in self-defense: "These things may be done, but not advertised", Burton himself wrote that Stanley "shoots negros as if they were monkeys" in an October 1876 letter to John Kirk. He also loathed Stanley for disproving his long-held theory that Lake Tanganyika, which he was the first European to discover, was the true source of the Nile, which may have influenced Burton to misrepresent Stanley's activities in Africa.

In 1877, not long after one of Stanley's expeditions, Reverend J. P. Farler met with African porters who had been part of the expedition and wrote, "Stanley's followers give dreadful accounts to their friends of the killing of inoffensive natives, stealing their ivory and goods, selling their captives, and so on. I do think a commission ought to inquire into these charges, because if they are true, it will do untold harm to the great cause of emancipating Africa. ... I cannot understand all the killing that Stanley has found necessary". Stanley, when reporting the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

as a young reporter, had been encouraged by his editors to exaggerate the number of Indians killed by the US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

. The legacy for Stanley, of being a helpless illegitimate boy, deserted by both parents, was a deep sense of inferiority that could only be kept at bay by claims of being much more powerful and feared than he was. Tim Jeal, in his biography of Stanley, has shown by a study of Stanley's diary and his colleague Frank Pocock's diary that on almost every occasion when there was conflict with Africans on the Congo in 1875–76, Stanley exaggerated the scale of the conflict and the deaths on both sides. On 14 February 1877, according to his colleague, Frank Pocock's diary, Stanley's nine canoes, and his sectional boat the ''Lady Alice'', were attacked and followed by eight canoes, crewed by Africans with firearms. In Stanley's book, ''Through the Dark Continent'', Stanley inflated this incident into a major battle, by increasing the number of hostile canoes to 60 and adjusting the casualties accordingly.

Stanley wrote with some measure of satisfaction when describing how Captain John Hanning Speke

Captain John Hanning Speke (4 May 1827 – 15 September 1864) was an English explorer and officer in the Indian Army (1895–1947), British Indian Army who made three exploratory expeditions to Africa. He is most associated with the search ...

, the first European to visit Uganda, had been punched in the teeth for disobedience to Sidi Mubarak Bombay

Sidi Mubarak Bombay (1820–1885) was a waYao explorer and guide, who participated in numerous expeditions by 19th century British explorers to East Africa.

He was a waYao, a subgroup of the Bantu peoples, born in 1820 on the border of Tanzani ...

, a caravan leader also employed by Stanley, which made Stanley claim that he would never allow Bombay to have the audacity to stand up for a boxing match with him. In the same paragraph, Stanley described how he several months later administered punishment to the African.

William Grant Stairs

William Grant Stairs (1 July 1863 – 9 June 1892) was a Canadian-British explorer, soldier, and adventurer who had a leading role in two of the most controversial expeditions in the Scramble for Africa.

Education

Born in Halifax, Nova Scotia, ...

found Stanley during the Emina Pasha expedition to be cruel, secretive and selfish. John Rose Troup, in his book about the Emin Pasha expedition, said that he saw Stanley's self-serving and vindictive side: "In the forgoing letter he brings forward disgraceful charges, that really do not refer to me at all, although he blames me for what happened. The injustice of his accusations, made as they are without documentary or, as far as I can learn, any evidence, can hardly be made clear to the public, but they must be aware, when they read what has preceded this correspondence, that he has acted as no one in his position should have acted".

By way of counterpoint, it may be noted that, in later in life, Stanley rebuked subordinates for inflicting needless corporal punishment. For beating one of his most trusted African's servants, he told Lieutenant Carlos Branconnier "that cruelty was not permissible" and that he would dismiss him for a future offense, and he did. Stanley was admired by Arthur Jephson, whom William Bonny, the acerbic medical assistant, described as the "most honourable" officer on the expedition. Jephson wrote, "Stanley never fights where there is the smallest chance of making friends with the natives and he is wonderfully patient & long suffering with them". Writer Tim Jeal

John Julian Timothy Jeal, known as Tim Jeal (born 27 January 1945 in London, England), is a British biographer of notable Victorians and is also a novelist. His publications include a memoir and biographies of David Livingstone (1973), Lord Ba ...