Henry Hunt (politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry "Orator" Hunt (6 November 1773 – 13 February 1835) was a British radical speaker and agitator remembered as a pioneer of working-class radicalism and an important influence on the later

Hunt became a prosperous farmer. He was first drawn into radical politics during the

Hunt became a prosperous farmer. He was first drawn into radical politics during the

Hunt was invited by the Patriotic Union Society, formed by the ''

Hunt was invited by the Patriotic Union Society, formed by the ''

Breviary Stuff Publications

2012. . * * ''Memoirs of Henry Hunt, Esq. Written by himself in his Majesty's Jail at Ilchester'', three volumes, 1820–1822 * ''Addresses to the Radical Reformers of England, Ireland and Scotland 1820–1822'', Henry Hunt * ''Addresses from Henry Hunt, Esq. M.P. to the Radical Reformers of England, Ireland and Scotland, on the measures of the Whig Ministers since they have been in place and power'', 1–13, 1831–1832 * ''The Preston Cock's Reply to the Kensington Dunghill'', 1831 * ''The Casualties of Peterloo'', Bush, Michael, 2006

Guide to the Henry Hunt Papers MS 563 1760-1838

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hunt, Henry 1773 births 1835 deaths Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies UK MPs 1830–1831 UK MPs 1831–1832 People from Wiltshire British radicals

Chartist movement

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

. He advocated parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

reform and the repeal of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. They were ...

. He was the first member of parliament to advocate for women's suffrage; in 1832 he presented a petition to parliament from a woman asking for the right to vote.

Background

Hunt was born on 6 November 1773 inUpavon

Upavon is a rural village and civil parish in the county of Wiltshire, England. As its name suggests, it is on the upper portion of the River Avon which runs from north to south through the village. It is on the north edge of Salisbury Plain ...

, Wiltshire.

Career

Hunt became a prosperous farmer. He was first drawn into radical politics during the

Hunt became a prosperous farmer. He was first drawn into radical politics during the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

, becoming a supporter of Francis Burdett

Sir Francis Burdett, 5th Baronet (25 January 1770 – 23 January 1844) was a British politician and Member of Parliament who gained notoriety as a proponent (in advance of the Chartists) of universal male suffrage, equal electoral districts, vo ...

. His talent for public speaking became noted in the electoral politics of Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

, where he denounced the complacency of both the Whigs and the Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

, and proclaimed himself a supporter of democratic radicalism. It was thanks to his particular talents that a new programme beyond the narrow politics of the day made steady progress in the difficult years that followed the conclusion of the war with France.

Orator

After his rousing speeches at mass meetings held inSpa Fields

Spa Fields is a park and its surrounding area in the London Borough of Islington, bordering Finsbury and Clerkenwell. Historically it is known for the Spa Fields riots of 1816 and an Owenite community which existed there between 1821 and 1824. The ...

in London in 1816, Hunt became known as the "Orator", a nickname attributed to Robert Southey

Robert Southey ( or ; 12 August 1774 – 21 March 1843) was an English poet of the Romantic school, and Poet Laureate from 1813 until his death. Like the other Lake Poets, William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Southey began as a ra ...

. He embraced a programme that included annual parliaments and universal suffrage, promoted openly and with none of the conspiratorial element of the old Jacobin clubs. The tactic he most favoured was that of 'mass pressure', which he felt, if given enough weight, could achieve reform without insurrection.

His efforts at mass politics

Mass politics is a political order resting on the emergence of mass political parties.

The emergence of mass politics generally associated with the rise of mass society coinciding with the Industrial Revolution in the West. However, because of ...

had the effect of radicalising large sections of the community unrepresented in Parliament, although the direct success of these efforts was limited.

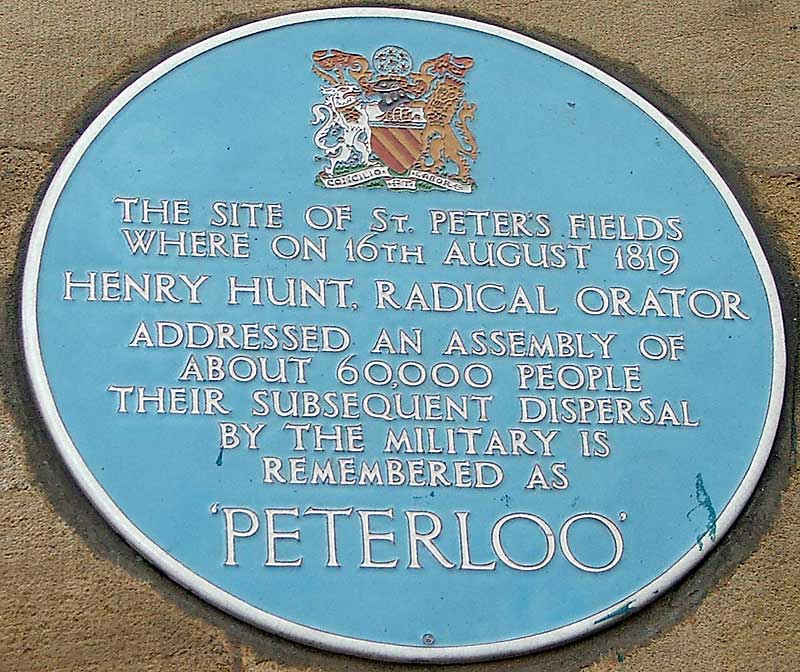

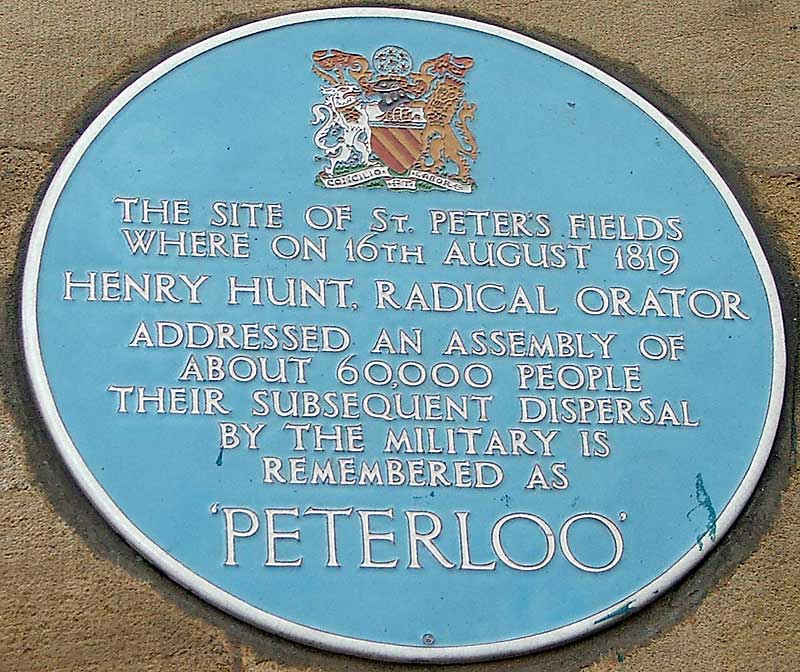

Peterloo

Hunt was invited by the Patriotic Union Society, formed by the ''

Hunt was invited by the Patriotic Union Society, formed by the ''Manchester Observer

The ''Manchester Observer'' was a short-lived non-conformist Liberal newspaper based in Manchester, England. Its radical agenda led to an invitation to Henry "Orator" Hunt to speak at a public meeting in Manchester, which subsequently led to th ...

'', to be one of the scheduled speakers at a rally in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

on 16 August 1819, which turned into the Peterloo massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliament ...

. Arrested for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

and convicted of the lesser charge of seditious conspiracy

Seditious conspiracy is a crime in various jurisdictions of Conspiracy (criminal), conspiring against the authority or legitimacy of the state. As a form of sedition, it has been described as a serious but lesser counterpart to treason, targeting ...

, he was sentenced to a term of 30 months at Ilchester Gaol. For the establishment, Hunt believed in some concepts that could threaten the profits of the business establishment: equal rights, universal suffrage, parliamentary reform, and an end to child labour.

The debacle at Peterloo, caused by an over-reaction of the local Manchester authorities, added greatly to his prestige. Moral force was not sufficient in itself, and physical force entailed too great a risk. Although urged to do so after Peterloo, Hunt refused to give his approval to schemes for a full-scale insurrection. Thereby momentum was lost, as more desperate souls turned to worn out cloak-and-dagger schemes, which surfaced in the Cato Street conspiracy

The Cato Street Conspiracy was a plot to murder all the British cabinet ministers and the Prime Minister Lord Liverpool in 1820. The name comes from the meeting place near Edgware Road in London. The police had an informer; the plotters fell into ...

.

While in prison for his role at Peterloo, Hunt turned to writing to disseminate his message, through a variety of forms including an autobiography. After his release he attempted to recover some of his lost fortune through new business ventures in London, which included the production and marketing of a roasted corn ''Breakfast Powder'', the "most salubrious and nourishing Beverage that can be substituted for the use of Tea and Coffee, which are always exciting, and frequently the most irritating to the Stomach and Bowels." He also made shoe-blacking bottles, which carried the slogan "Equal Laws, Equal Rights, Annual Parliaments, Universal Suffrage, and the Ballot." Synthetic coal, intended specifically for the French market, was another of his schemes. After the July Revolution

The French Revolution of 1830, also known as the July Revolution (french: révolution de Juillet), Second French Revolution, or ("Three Glorious ays), was a second French Revolution after the first in 1789. It led to the overthrow of King ...

in 1830 he sent samples to Gilbert du Motier, marquis de La Fayette

Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834), known in the United States as Lafayette (, ), was a French aristocrat, freemason and military officer who fought in the American Revolutio ...

and other political heroes, along with fraternal greetings.

Parliament

Business interests notwithstanding, he still found time for practical politics, fighting battles over a whole range of issues, and always pushing for reform and accountability. In 1830 he became a member of Parliament for Preston defeating the future British Prime Minister Edward Stanley, but was defeated when standing for re-election in 1833. As a consistent champion of the working classes, a term he used with increasing frequency, he opposed the Whigs, both old and new, and theReform Act 1832

The Representation of the People Act 1832 (also known as the 1832 Reform Act, Great Reform Act or First Reform Act) was an Act of Parliament, Act of Parliament of the United Kingdom (indexed as 2 & 3 Will. IV c. 45) that introduced major chan ...

, which he believed did not go far enough in the extension of the franchise. He gave speeches addressed to the "Working Classes and no other", urging them to press for full equal rights. In 1832 he presented the first petition in support of women's suffrage to Parliament. It was received however with much ribald laughter and antagonism. Also in that year, he petitioned parliament on behalf of the radical preacher John Ward, who had been imprisoned for blasphemy.

In his opposition to the Reform Bill, Orator Hunt revived the Great Northern Union ttp://www.gnusings.com/ The Great Northern Unionwas a men's barbershop chorus based in the Minneapolis-St. Paul area. They performed four-part harmony in the barbershop style. Officially, they were the Hilltop, Minnesota chapter of the Barbershop ...

, a pressure group he set up some years before, intended to unite the northern industrial workers behind a platform of full democratic reform; and it is in this specifically that his influence on Chartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, w ...

can be detected.

Death

Hunt's health declined during 1834, and in early 1835 he suffered a severe stroke at Alresford, Hampshire, where he died on 13 February 1835. He was buried atParham Park

Parham Park is an Elizabethan house and estate in the civil parish of Parham, west of the village of Cootham, and between Storrington and Pulborough, West Sussex, South East England. The estate was originally owned by the Monastery of Westmins ...

, Sussex.

Legacy

A monument to Hunt was erected in 1842 by "the working people", in Every Street, Manchester, in Scholefield's Chapel Yard. A "spiral" march was held on the anniversary of Peterloo, from Piccadilly around the town past the Peterloo site, down to Deansgate and through Ancoats to the monument. The monument's stonework deteriorated, and it was demolished in 1888.In popular culture

InMike Leigh

Mike Leigh (born 20 February 1943) is an English film and theatre director, screenwriter and playwright. He studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) and further at the Camberwell School of Art, the Central School of Art and Design ...

's 2018 film ''Peterloo

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliamen ...

'', Hunt is portrayed by Rory Kinnear

Rory Michael Kinnear (born 17 February 1978) is an English actor and playwright who has worked with the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal National Theatre. In 2014, he won the Olivier Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of William S ...

.

See also

*Peterloo Massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Fifteen people died when cavalry charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who had gathered to demand the reform of parliament ...

References

* Belchem, John. ''"Orator" Hunt: Henry Hunt and English Working-Class Radicalism''. Clarendon, 1985. . Republished bBreviary Stuff Publications

2012. . * * ''Memoirs of Henry Hunt, Esq. Written by himself in his Majesty's Jail at Ilchester'', three volumes, 1820–1822 * ''Addresses to the Radical Reformers of England, Ireland and Scotland 1820–1822'', Henry Hunt * ''Addresses from Henry Hunt, Esq. M.P. to the Radical Reformers of England, Ireland and Scotland, on the measures of the Whig Ministers since they have been in place and power'', 1–13, 1831–1832 * ''The Preston Cock's Reply to the Kensington Dunghill'', 1831 * ''The Casualties of Peterloo'', Bush, Michael, 2006

External links

* * *Guide to the Henry Hunt Papers MS 563 1760-1838

at th

University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hunt, Henry 1773 births 1835 deaths Members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies UK MPs 1830–1831 UK MPs 1831–1832 People from Wiltshire British radicals