Henry Halleck on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

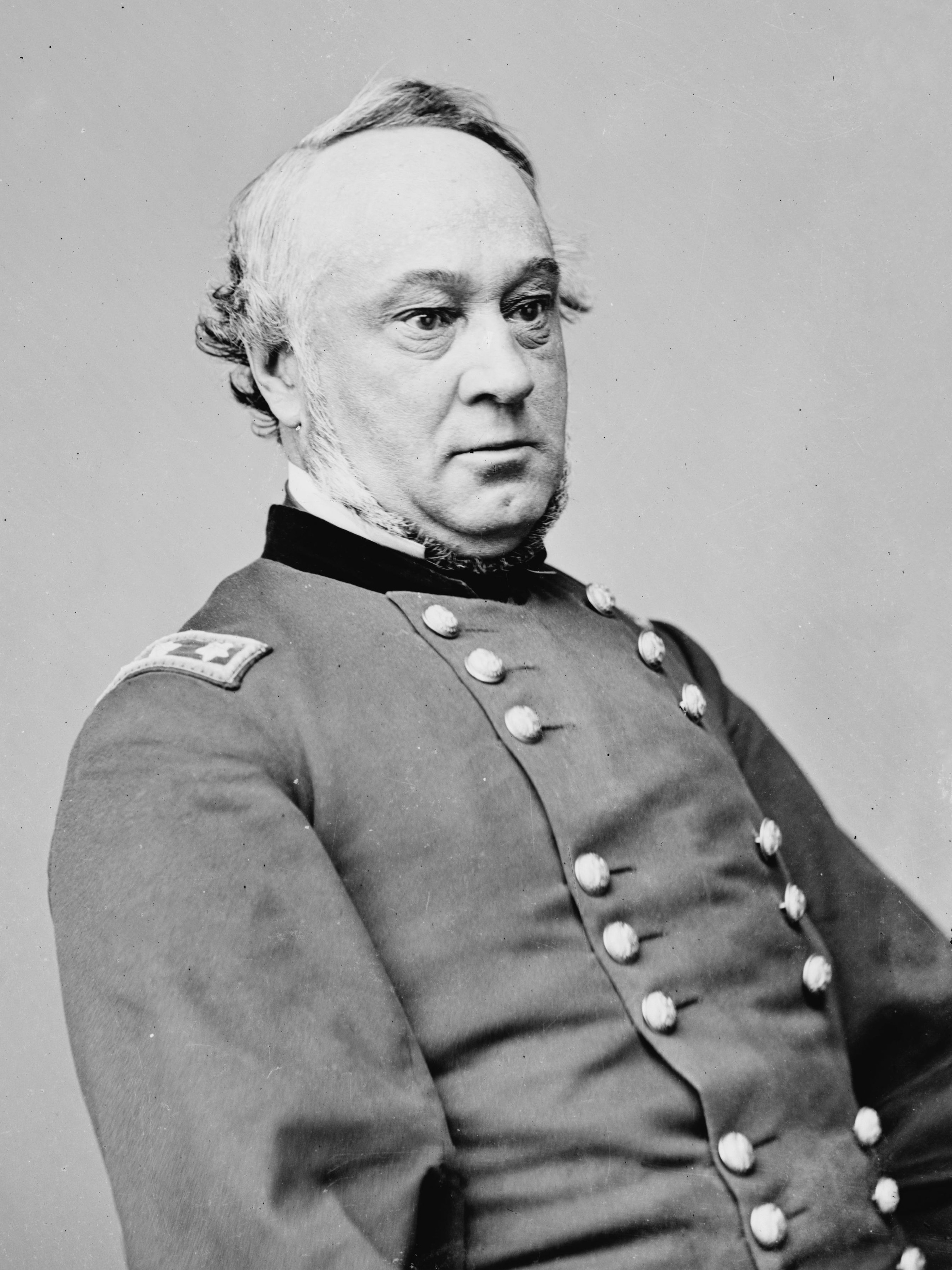

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior

/ref> His work, one of the first expressions of American military professionalism, was well received by his colleagues and was considered one of the definitive tactical treatises used by officers in the coming Civil War. His scholarly pursuits earned him the (later derogatory) nickname "Old Brains." During the

During the

Historian

Historian

In the aftermath of the failed Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, President Lincoln summoned Halleck to the East to become General in Chief of the Armies of the United States, as of July 23, 1862. Lincoln hoped that Halleck could prod his subordinate generals into taking more coordinated, aggressive actions across all of the theaters of war, but he was quickly disappointed, and was quoted as regarding him as "little more than a first rate clerk."Warner, pp. 195–97. Grant replaced Halleck in command of most forces in the West, but Buell's Army of the Ohio was separated and Buell reported directly to Halleck, as a peer of Grant. Halleck began transferring divisions from Grant to Buell; by September, four divisions had moved, leaving Grant with 46,000 men.

In Washington, Halleck continued to excel at administrative issues and facilitated the training, equipping, and deployment of thousands of Union soldiers over vast areas. He was unsuccessful, however, as a commander of the field armies or as a grand strategist. His cold, abrasive personality alienated his subordinates; one observer described him as a "cold, calculating owl." Historian

In the aftermath of the failed Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, President Lincoln summoned Halleck to the East to become General in Chief of the Armies of the United States, as of July 23, 1862. Lincoln hoped that Halleck could prod his subordinate generals into taking more coordinated, aggressive actions across all of the theaters of war, but he was quickly disappointed, and was quoted as regarding him as "little more than a first rate clerk."Warner, pp. 195–97. Grant replaced Halleck in command of most forces in the West, but Buell's Army of the Ohio was separated and Buell reported directly to Halleck, as a peer of Grant. Halleck began transferring divisions from Grant to Buell; by September, four divisions had moved, leaving Grant with 46,000 men.

In Washington, Halleck continued to excel at administrative issues and facilitated the training, equipping, and deployment of thousands of Union soldiers over vast areas. He was unsuccessful, however, as a commander of the field armies or as a grand strategist. His cold, abrasive personality alienated his subordinates; one observer described him as a "cold, calculating owl." Historian  In Halleck's defense, his subordinate commanders in the Eastern Theater, whom he did not select, were reluctant to move against General

In Halleck's defense, his subordinate commanders in the Eastern Theater, whom he did not select, were reluctant to move against General

After Grant forced Lee's surrender at

After Grant forced Lee's surrender at

''International law, or, Rules regulating the intercourse of states in peace and war'' (1861)

* ''The Mexican War in Baja California: the memorandum of Captain Henry W. Halleck concerning his expeditions in Lower California, 1846–1848'' (posthumous, 1977) * Editor, ''Bitumen: Its Varieties, Properties, and Uses'' (1841) * Translator, ''A Collection of Mining Laws of Spain and Mexico'' (1859) * Translator

''Life of Napoleon'' by Baron Antoine-Henri Jomini

(1864) published by David Van Nostrand, link from

Vol. 8

Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1997. First published 1908 by Federal Publishing Company. * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Woodworth, Steven E. ''Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865''. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. .

California State Military Museum description of Halleck in California

2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. . * Simon, John Y. ''Grant and Halleck: Contrasts in Command''. Frank L. Klement Lectures, No. 5. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1996. .

Biography at Mr. Lincoln's White House

* *

Major General Henry Hallek

at

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, ...

officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important participant in the admission of California as a state and became a successful lawyer and land developer. Halleck served as the General in Chief of the Armies of the United States from 1862 to 1864.

Early in the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

, Halleck was a senior Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

commander in the Western Theater. He commanded operations in the Western Theater from 1861 until 1862, during which time, while the Union armies in the east were defeated and held back, the troops under Halleck's command won many important victories. However, Halleck was not present at the battles, and his subordinates earned most of the recognition. The only operation in which Halleck exercised field command was the siege of Corinth

The siege of Corinth (also known as the first Battle of Corinth) was an American Civil War engagement lasting from April 29 to May 30, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. A collection of Union forces under the overall command of Major General Henry ...

in the spring of 1862, a Union victory which he conducted with extreme caution. Halleck also developed rivalries with many of his subordinate generals, such as Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

and Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles— Shiloh and Per ...

. In July 1862, following Major General George B. McClellan's failed Peninsula Campaign in the Eastern Theater, Halleck was promoted to general in chief. Halleck served in this capacity for about a year and a half.

Halleck was a cautious general who believed strongly in thorough preparations for battle and in the value of defensive fortifications over quick, aggressive action. He was a master of administration, logistics, and the politics necessary at the top of the military hierarchy, but exerted little effective control over field operations from his post in Washington, D.C. His subordinates frequently criticized him and at times ignored his instructions. President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

* President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ...

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

once described him as "little more than a first rate clerk."

In March 1864, Grant was promoted to general in chief, and Halleck was relegated to chief of staff. Without the pressure of having to control the movements of the armies, Halleck performed capably in this task, ensuring that the Union armies were well-equipped.

Early life

Halleck was born on a farm in Westernville,Oneida County, New York

Oneida County is a county in the state of New York, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 232,125. The county seat is Utica. The name is in honor of the Oneida, one of the Five Nations of the Iroquois League or ''Haudenos ...

, third child of 14 of Joseph Halleck, a lieutenant who served in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

, and Catherine Wager Halleck. Young Henry detested the thought of an agricultural life and ran away from home at an early age to be raised by an uncle, David Wager of Utica. He attended Hudson Academy and Union College, then the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

. He became a favorite of military theorist Dennis Hart Mahan and was allowed to teach classes while still a cadet.Fredriksen, pp. 908–911. He graduated in 1839, third in his class of 31 cadets, as a second lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army unt ...

of engineers.Eicher, p. 274. After spending a few years improving the defenses of New York Harbor

New York Harbor is at the mouth of the Hudson River where it empties into New York Bay near the East River tidal estuary, and then into the Atlantic Ocean on the east coast of the United States. It is one of the largest natural harbors in ...

, he wrote a report for the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

on seacoast defenses, ''Report on the Means of National Defence'', which pleased General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, who rewarded Halleck with a trip to Europe in 1844 to study European fortifications and the French military. Returning home a first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

, Halleck gave a series of twelve lectures at the Lowell Institute in Boston that were subsequently published in 1846 as ''Elements of Military Art and Science''.California State Military Museum/ref> His work, one of the first expressions of American military professionalism, was well received by his colleagues and was considered one of the definitive tactical treatises used by officers in the coming Civil War. His scholarly pursuits earned him the (later derogatory) nickname "Old Brains."

During the

During the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the ...

, Halleck was assigned to duty in California. During his seven-month journey on the transport USS ''Lexington'' around Cape Horn

Cape Horn ( es, Cabo de Hornos, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which are the Diego Ramí ...

, assigned as aide-de-camp to Commodore William Shubrick, he translated Henri Jomini's ''Vie politique et militaire de Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader wh ...

'', which further enhanced his reputation for scholarship. He spent several months in California constructing fortifications, then was first exposed to combat on November 11, 1847, during Shubrick's capture of the port of Mazatlán

Mazatlán () is a city in the Mexican state of Sinaloa. The city serves as the municipal seat for the surrounding '' municipio'', known as the Mazatlán Municipality. It is located at on the Pacific coast, across from the southernmost tip ...

; Lt. Halleck served as lieutenant governor of the occupied city. He was awarded a brevet promotion to captain in 1847 for his "gallant and meritorious service" in California and Mexico. (He would later be appointed captain in the regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the following:

* a standin ...

on July 1, 1853.) He was transferred north to serve under General Bennet Riley, the governor general of the California Territory

The history of California can be divided into the Native American period (about 10,000 years ago until 1542), the European exploration period (1542–1769), the Spanish colonial period (1769–1821), the Mexican period (1821–1848), and Un ...

. Halleck was soon appointed military secretary of state, a position which made him the governor's representative at the 1849 convention in Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

where the California state constitution was written. Halleck became one of the principal authors of the document. The California State Military Museum writes that Halleck "was t the conventionand in a lone measure its brains because he had given more studious thought to the subject than any other, and General Riley had instructed him to help frame the new constitution." He was nominated during the convention to be one of two men to represent the new state in the United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and po ...

, but received only enough votes for third place. During his political activities, he found time to join a law firm in San Francisco, Halleck, Peachy & Billings, which became so successful that he resigned his commission in 1854. The following year, he married Elizabeth Hamilton, granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charle ...

and sister of Union general Schuyler Hamilton. Their only child, Henry Wager Halleck, Jr., was born in 1856, and died in 1882.

Halleck became a wealthy man as a lawyer and land speculator, and a noted collector of "Californiana." He obtained thousands of pages of official documents on the Spanish missions and colonization of California, which were copied and are now maintained by the Bancroft Library

The Bancroft Library in the center of the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, is the university's primary special-collections library. It was acquired from its founder, Hubert Howe Bancroft, in 1905, with the proviso that it reta ...

of the University of California

The University of California (UC) is a public land-grant research university system in the U.S. state of California. The system is composed of the campuses at Berkeley, Davis, University of California, Irvine, Irvine, University of Califor ...

, the originals having been destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

At 05:12 Pacific Standard Time on Wednesday, April 18, 1906, the coast of Northern California was struck by a major earthquake with an estimated moment magnitude of 7.9 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (''Extreme''). High-intensity ...

and fire. He built the Montgomery Block

The Montgomery Block, also known as Monkey Block and Halleck's Folly, was a historic building active from 1853 to 1959, and was located in San Francisco, California. It was San Francisco's first fireproof and earthquake resistant building. It came ...

, San Francisco's first fireproof building, home to lawyers, businessmen, and later, the city's Bohemian

Bohemian or Bohemians may refer to:

*Anything of or relating to Bohemia

Beer

* National Bohemian, a brand brewed by Pabst

* Bohemian, a brand of beer brewed by Molson Coors

Culture and arts

* Bohemianism, an unconventional lifestyle, origin ...

writers and newspapers. He was a director of the Almaden Quicksilver ( Mercury) Company in San Jose, president of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, a builder in Monterey

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bot ...

, and owner of the 30,000 acre (120 km2) Rancho Nicasio Rancho Nicasio was a Mexican land grant of granted to the Coast Miwok indigenous people in 1835, located in the present-day Marin County, California, a tract of land that stretched from San Geronimo to Tomales Bay. Today, Nicasio, California is a ...

in Marin County

Marin County is a county located in the northwestern part of the San Francisco Bay Area of the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 262,231. Its county seat and largest city is San Rafael. Marin County is acros ...

. But he remained involved in military affairs and by early 1861 he was a major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

of the California Militia

The California National Guard is part of the National Guard of the United States, a dual federal-state military reserve force. The CA National Guard has three components: the CA Army National Guard, CA Air National Guard, and CA State Guard. ...

.

Civil War

Western Theater

As the Civil War began, Halleck was nominally a Democrat and was sympathetic to the South, but he had a strong belief in the value of the Union. His reputation as a military scholar and an urgent recommendation fromWinfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

earned him the rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of ...

in the regular army, effective August 19, 1861, making him the fourth most senior general (after Scott, George B. McClellan, and John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

). He was assigned to command the Department of the Missouri, replacing Frémont in St. Louis on November 9, and his talent for administration quickly sorted out the chaos of fraud and disorder left by his predecessor. He set to work on the "twin goals of expanding his command and making sure that no blame of any sort fell on him."

Historian

Historian Kendall Gott

Kendall D. Gott is an Army veteran of Desert Storm, the Senior Historian at the US Army Combat Studies Institute, and author of several works. He is most noted academically as a Civil War and general military history historian, and is a frequen ...

described Halleck as a department commander:

Halleck established an uncomfortable relationship with the man who would become his most successful subordinate and future commander, Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

. The pugnacious Grant had just completed the minor, but bloody, Battle of Belmont

The Battle of Belmont was fought on November 7, 1861 in Mississippi County, Missouri. It was the first combat test in the American Civil War for Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, the future Union Army general in chief and eventual U.S. president, ...

and had ambitious plans for amphibious operations on the Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 36th-largest by ...

and Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic counties of England, historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th c ...

Rivers. Halleck, by nature a cautious general, but also judging that Grant's reputation for alcoholism in the prewar period made him unreliable, rejected Grant's plans. However, under pressure from President Lincoln to take offensive action, Halleck reconsidered and Grant conducted operations with naval and land forces against Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862, capturing both, along with 14,000 Confederates.

Grant had delivered the first significant Union victory of the war. Halleck obtained a promotion for him to major general of volunteers, along with some other generals in his department, and used the victory as an opportunity to request overall command in the Western Theater, which he currently shared with Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell

Don Carlos Buell (March 23, 1818November 19, 1898) was a United States Army officer who fought in the Seminole War, the Mexican–American War, and the American Civil War. Buell led Union armies in two great Civil War battles— Shiloh and Per ...

, but which was not granted. He briefly relieved Grant of field command of a newly ordered expedition up the Tennessee River

The Tennessee River is the largest tributary of the Ohio River. It is approximately long and is located in the southeastern United States in the Tennessee Valley. The river was once popularly known as the Cherokee River, among other name ...

after Grant met Buell in Nashville

Nashville is the capital city of the U.S. state of Tennessee and the seat of Davidson County. With a population of 689,447 at the 2020 U.S. census, Nashville is the most populous city in the state, 21st most-populous city in the U.S., and th ...

, citing rumors of renewed alcoholism, but soon restored Grant to field command (pressure by Lincoln and the War Department may have been a factor in this about-face). Explaining the reinstatement to Grant, Halleck portrayed it as his effort to correct an injustice, not revealing to Grant that the injustice had originated with him. When Grant wrote to Halleck suggesting "I must have enemies between you and myself," Halleck replied, "You are mistaken. There is no enemy between you and me."

Halleck's department performed well in early 1862, driving the Confederates from the state of Missouri

Missouri is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee): Iowa to the north, Illinois, Kentucky and Tennessee to the east, Arkansas t ...

and advancing into Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the O ...

. They held all of West Tennessee

West Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that roughly comprises the western quarter of the state. The region includes 21 counties between the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers, delineated by state law. Its ...

and half of Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of the U.S. state of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the ...

. Grant, not yet aware of the political maneuvering behind his back, regarded Halleck as "one of the greatest men of the age" and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman described him as the "directing genius" of the events that had given the Union cause such a "tremendous lift" in the previous months. This performance can be attributed to Halleck's strategy, administrative skills, and his good management of resources, and to the excellent execution by his subordinates—Grant, Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis

Samuel Ryan Curtis (February 3, 1805 – December 26, 1866) was an American military officer and one of the first Republicans elected to Congress. He was most famous for his role as a Union Army general in the Trans-Mississippi Theater of the ...

at Pea Ridge, and Maj. Gen. John Pope at Island Number 10. Military historians disagree about Halleck's personal role in providing these victories. Some offer him the credit based on his overall command of the department; others, particularly those viewing his career through the lens of later events, believe that his subordinates were the primary factor.

On March 11, 1862, Halleck's command was enlarged to include Ohio

Ohio () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Of the List of states and territories of the United States, fifty U.S. states, it is the List of U.S. states and territories by area, 34th-l ...

and Kansas

Kansas () is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its Capital city, capital is Topeka, Kansas, Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita, Kansas, Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebras ...

, along with Buell's Army of the Ohio

The Army of the Ohio was the name of two Union armies in the American Civil War. The first army became the Army of the Cumberland and the second army was created in 1863.

History

1st Army of the Ohio

General Orders No. 97 appointed Maj. Gen. ...

, and was renamed the Department of the Mississippi. Grant's Army of the Tennessee

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

was attacked on April 6 at Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, in the Battle of Shiloh

The Battle of Shiloh (also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing) was fought on April 6–7, 1862, in the American Civil War. The fighting took place in southwestern Tennessee, which was part of the war's Western Theater. The battlefield i ...

. With reinforcements from Buell, on April 7 Grant managed to repulse the Confederate Army under Generals Albert Sidney Johnston

Albert Sidney Johnston (February 2, 1803 – April 6, 1862) served as a general in three different armies: the Texian Army, the United States Army, and the Confederate States Army. He saw extensive combat during his 34-year military career, figh ...

and P.G.T. Beauregard, but at high cost in casualties. Pursuant to an earlier plan, Halleck arrived to take personal command of his massive army in the field for the first time. Grant was under public attack over the slaughter at Shiloh, and Halleck replaced Grant as a wing commander and assigned him instead to serve as second-in-command of the entire 100,000 man force, a job which Grant complained was a censure and akin to an arrest. Halleck proceeded to conduct operations against Beauregard's army in Corinth, Mississippi

Corinth is a city in and the county seat of Alcorn County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 14,573 at the 2010 census. Its ZIP codes are 38834 and 38835. It lies on the state line with Tennessee.

History

Corinth was founded i ...

, called the siege of Corinth

The siege of Corinth (also known as the first Battle of Corinth) was an American Civil War engagement lasting from April 29 to May 30, 1862, in Corinth, Mississippi. A collection of Union forces under the overall command of Major General Henry ...

because Halleck's army, twice the size of Beauregard's, moved so cautiously and stopped daily to erect elaborate field fortifications; Beauregard eventually abandoned Corinth without a fight.

General in Chief

In the aftermath of the failed Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, President Lincoln summoned Halleck to the East to become General in Chief of the Armies of the United States, as of July 23, 1862. Lincoln hoped that Halleck could prod his subordinate generals into taking more coordinated, aggressive actions across all of the theaters of war, but he was quickly disappointed, and was quoted as regarding him as "little more than a first rate clerk."Warner, pp. 195–97. Grant replaced Halleck in command of most forces in the West, but Buell's Army of the Ohio was separated and Buell reported directly to Halleck, as a peer of Grant. Halleck began transferring divisions from Grant to Buell; by September, four divisions had moved, leaving Grant with 46,000 men.

In Washington, Halleck continued to excel at administrative issues and facilitated the training, equipping, and deployment of thousands of Union soldiers over vast areas. He was unsuccessful, however, as a commander of the field armies or as a grand strategist. His cold, abrasive personality alienated his subordinates; one observer described him as a "cold, calculating owl." Historian

In the aftermath of the failed Peninsula Campaign in Virginia, President Lincoln summoned Halleck to the East to become General in Chief of the Armies of the United States, as of July 23, 1862. Lincoln hoped that Halleck could prod his subordinate generals into taking more coordinated, aggressive actions across all of the theaters of war, but he was quickly disappointed, and was quoted as regarding him as "little more than a first rate clerk."Warner, pp. 195–97. Grant replaced Halleck in command of most forces in the West, but Buell's Army of the Ohio was separated and Buell reported directly to Halleck, as a peer of Grant. Halleck began transferring divisions from Grant to Buell; by September, four divisions had moved, leaving Grant with 46,000 men.

In Washington, Halleck continued to excel at administrative issues and facilitated the training, equipping, and deployment of thousands of Union soldiers over vast areas. He was unsuccessful, however, as a commander of the field armies or as a grand strategist. His cold, abrasive personality alienated his subordinates; one observer described him as a "cold, calculating owl." Historian Steven E. Woodworth

Steven E. Woodworth (born January 28, 1961) is an American historian specializing in studies of the American Civil War. He has written numerous books concerning the Civil War, and as a professor has taught classes on the Civil War, the Reconstructi ...

wrote, "Beneath the ponderous dome of his high forehead, the General would gaze goggle-eyed at those who spoke to him, reflecting long before answering and simultaneously rubbing both elbows all the while, leading one observer to quip that "the great intelligence he was reputed to possess must be located in his elbows." This disposition also made him unpopular with the Union press corps, who criticized him frequently.

Halleck, more a bureaucrat than a soldier, was able to impose little discipline or direction on his field commanders. Strong personalities such as George B. McClellan, John Pope, and Ambrose Burnside routinely ignored his advice and instructions. A telling example of his lack of control was during the Northern Virginia Campaign of 1862, when Halleck was unable to motivate McClellan to reinforce Pope in a timely manner, contributing to the Union defeat at the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confedera ...

. It was from this incident that Halleck fell from grace. Abraham Lincoln said that he had given Halleck full power and responsibility as general in chief. "He ran it on that basis till Pope's defeat; but ever since that event he has shrunk from responsibility whenever it was possible." In Halleck's defense, his subordinate commanders in the Eastern Theater, whom he did not select, were reluctant to move against General

In Halleck's defense, his subordinate commanders in the Eastern Theater, whom he did not select, were reluctant to move against General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of Nor ...

and the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

. Many of his generals in the West, other than Grant, also lacked aggressiveness. And despite Lincoln's pledge to give the general in chief full control, both he and Secretary of War

The secretary of war was a member of the U.S. president's Cabinet, beginning with George Washington's administration. A similar position, called either "Secretary at War" or "Secretary of War", had been appointed to serve the Congress of the ...

Edwin M. Stanton micromanaged many aspects of the military strategy of the nation. Halleck wrote to Sherman, "I am simply a military advisor of the Secretary of War and the President, and must obey and carry out what they decide upon, whether I concur in their decisions or not. As a good soldier I obey the orders of my superiors. If I disagree with them I say so, but when they decide, is my duty faithfully to carry out their decision."

Chief of staff

On March 12, 1864, afterUlysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union A ...

, Halleck's former subordinate in the West, was promoted to lieutenant general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on th ...

and general in chief, Halleck was relegated to chief of staff

The title chief of staff (or head of staff) identifies the leader of a complex organization such as the armed forces, institution, or body of persons and it also may identify a principal staff officer (PSO), who is the coordinator of the supporti ...

, responsible for the administration of the vast U.S. armies. Grant and the War Department took special care to let Halleck down gently. Their orders stated that Halleck had been relieved as general in chief "at his own request."

Now that there was an aggressive general in the field, Halleck's administrative capabilities complemented Grant's field operations and they worked well together. Throughout the arduous Overland Campaign and Richmond-Petersburg Campaign of 1864, Halleck saw to it that Grant was properly supplied, equipped, and reinforced on a scale that wore down the Confederates. He agreed with Grant and Sherman on the implementation of a hard war toward the Southern economy and endorsed both Sherman's March to the Sea

Sherman's March to the Sea (also known as the Savannah campaign or simply Sherman's March) was a military campaign of the American Civil War conducted through Georgia from November 15 until December 21, 1864, by William Tecumseh Sherman, maj ...

and Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close a ...

's destruction of the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridg ...

. However, the 1864 Red River Campaign, a doomed attempt to occupy Eastern Texas, had been advocated by Halleck, over the objections of Nathaniel P. Banks

Nathaniel Prentice (or Prentiss) Banks (January 30, 1816 – September 1, 1894) was an American politician from Massachusetts and a Union general during the Civil War. A millworker by background, Banks was prominent in local debating societies, ...

, who commanded the operation. When the campaign failed, Halleck claimed to Grant that it had been Banks' idea in the first place, not his - an example of Halleck's habit of deflecting blame.

Still, his contributions to military theory are credited with encouraging a new spirit of professionalism in the army.

Postbellum career

After Grant forced Lee's surrender at

After Grant forced Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House Appomattox Court House could refer to:

* The village of Appomattox Court House, now the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, in central Virginia (U.S.), where Confederate army commander Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union commander Ulyss ...

, Halleck was assigned to command the Military Division of the James

The Military Division of the James was an administrative division or formation of the United States Army which existed for ten weeks at the end of the American Civil War. This military division controlled military operations between April 19, 1865 ...

, headquartered at Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, Californi ...

. He was present at Lincoln's death and a pall-bearer at Lincoln's funeral. He lost his friendship with General William T. Sherman when he quarreled with him over Sherman's tendency to be lenient toward former Confederates. In August 1865 he was transferred to the Division of the Pacific in California, essentially in military exile.Fredriksen, pp. 910–11. While holding this command he accompanied photographer Eadweard Muybridge

Eadweard Muybridge (; 9 April 1830 – 8 May 1904, born Edward James Muggeridge) was an English photographer known for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture projection. He adopted the first ...

to the newly purchased Russian America

Russian America (russian: Русская Америка, Russkaya Amerika) was the name for the Russian Empire's colonial possessions in North America from 1799 to 1867. It consisted mostly of present-day Alaska in the United States, but a ...

. He and Senator Charles Sumner are credited with applying the name "Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U ...

" to that region. In March 1869, he was assigned to command the Military Division of the South

Military Division of the South was a U. S. Army unit established in 1869 during the period of Reconstruction, but had an earlier life after the War of 1812 through 1821 when Andrew Jackson held that command and the military division was discontinu ...

, headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

.

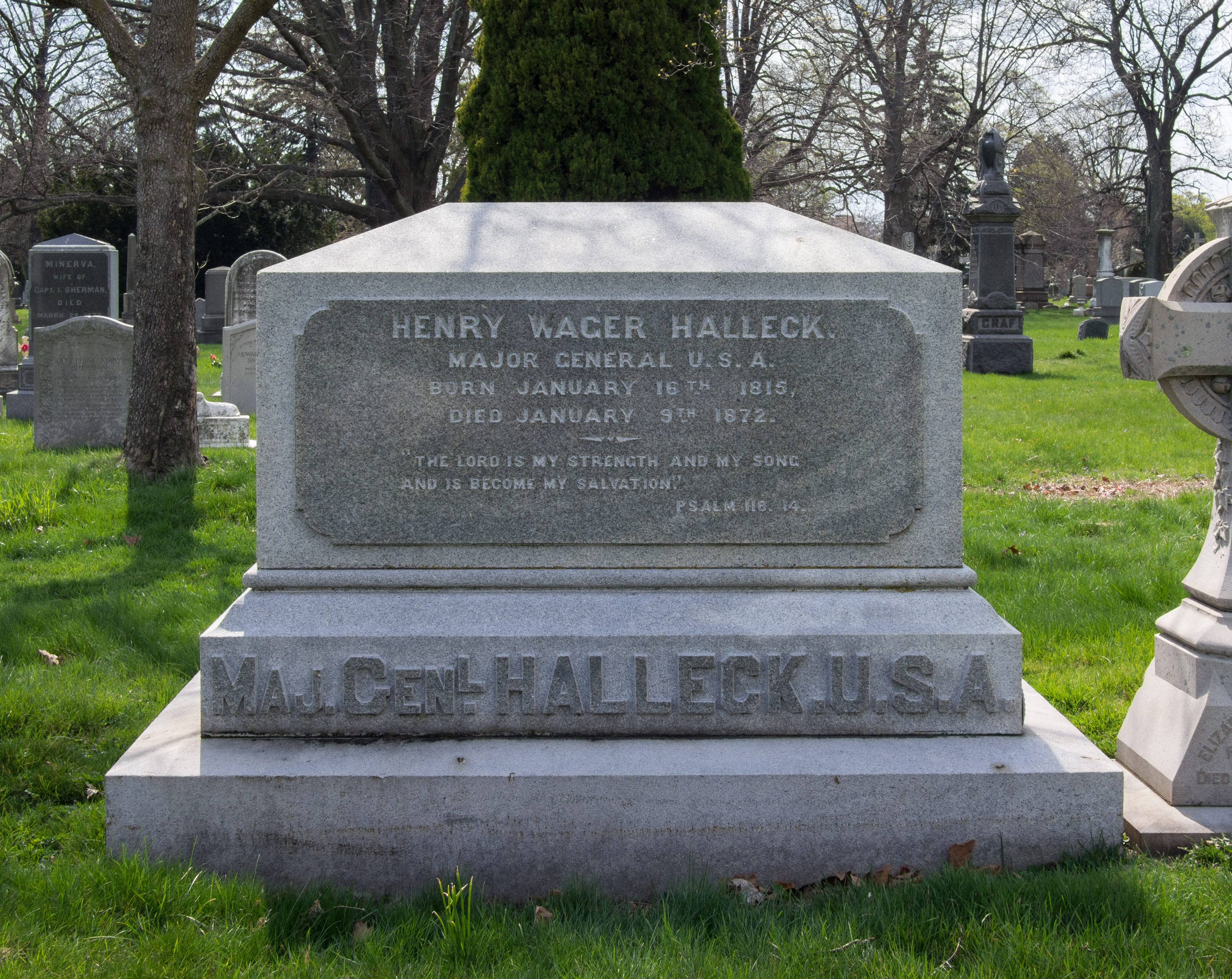

Henry Halleck became ill in early 1872 and his condition was diagnosed as edema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels tight, the area ma ...

caused by liver disease. He died at his post in Louisville. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery

Green-Wood Cemetery is a cemetery in the western portion of Brooklyn, New York City. The cemetery is located between South Slope/ Greenwood Heights, Park Slope, Windsor Terrace, Borough Park, Kensington, and Sunset Park, and lies several blo ...

, in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, and is commemorated by a street named for him in San Francisco and a statue in Golden Gate Park

Golden Gate Park, located in San Francisco, California, United States, is a large urban park consisting of of public grounds. It is administered by the San Francisco Recreation & Parks Department, which began in 1871 to oversee the developm ...

. He left no memoirs for posterity and apparently destroyed his private correspondence and memoranda. His estate at his death showed a net value of $474,773.16 ($ in dollars). His widow, Elizabeth, married Col. George Washington Cullum

George Washington Cullum (25 February 1809 – 28 February 1892) was an American soldier, engineer and writer. He worked as the supervising engineer on the building and repair of many fortifications across the country. Cullum served as a general ...

in 1875. Cullum had served as Halleck's chief of staff in the Western Theater and then on his staff in Washington.

Dates of rank

Selected works

* ''Report on the Means of National Defence'' (1843) * ''Elements of Military Art and Science'' (1846)''International law, or, Rules regulating the intercourse of states in peace and war'' (1861)

* ''The Mexican War in Baja California: the memorandum of Captain Henry W. Halleck concerning his expeditions in Lower California, 1846–1848'' (posthumous, 1977) * Editor, ''Bitumen: Its Varieties, Properties, and Uses'' (1841) * Translator, ''A Collection of Mining Laws of Spain and Mexico'' (1859) * Translator

''Life of Napoleon'' by Baron Antoine-Henri Jomini

(1864) published by David Van Nostrand, link from

Google books

Google Books (previously known as Google Book Search, Google Print, and by its code-name Project Ocean) is a service from Google Inc. that searches the full text of books and magazines that Google has scanned, converted to text using optical ...

Namesakes

* Fort Halleck (1862–66): Military outpost inDakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of N ...

built to protect travelers on the Overland Trail

The Overland Trail (also known as the Overland Stage Line) was a stagecoach and wagon trail in the American West during the 19th century. While portions of the route had been used by explorers and trappers since the 1820s, the Overland Trail was ...

.

* Halleck, Nevada

Halleck is an unincorporated community in central Elko County, northeastern Nevada, in the Western United States.

Geography

Halleck lies at the interchange of Interstate 80 and State Route 229 northeast of the city of Elko. Its elevation ...

, an unincorporated community

* Halleck Street in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish for " Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the fourth most populous in California and 17t ...

near the Presidio.''The Chronicle'' 12 April 1987 p.7

*Halleck Cottage was the name given to one of the homes at the San Francisco Protestant Orphanage (current name: Edgewood Center) in remembrance to a donation made to Mrs. Haight and Mrs. Waller who served as board managers at the time for the San Francisco Orphan Asylum Society (SFOA).

In popular media

* Halleck is a character in some American Civil War alternate histories, including the novels ''Stars and Stripes Forever'' (1998) by Harry Harrison and '' Gettysburg: A Novel of the Civil War'' (2003) byNewt Gingrich

Newton Leroy Gingrich (; né McPherson; born June 17, 1943) is an American politician and author who served as the 50th speaker of the United States House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999. A member of the Republican Party, he was the U. ...

and William R. Forstchen

William R. Forstchen (born October 11, 1950) is an American historian and author. A Professor of History and Faculty Fellow at Montreat College, in Montreat, North Carolina, he received his doctorate from Purdue University.

He has published nu ...

. In Harrison's novel, while Halleck's role is fairly important, he does not personally appear.

* In the 1941 film '' They Died With Their Boots On'', Sydney Greenstreet plays General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, however the fictionalized Scott is a conflation partly based on Halleck.

* In the 1994 film ''Quiz Show'', Halleck is the correct answer to an 11-point question posed to Charles Van Doren

Charles Lincoln Van Doren (February 12, 1926 – April 9, 2019) was an American writer and editor who was involved in a television quiz show scandal in the 1950s. In 1959 he testified before the U.S. Congress that he had been given the corr ...

that gives him his first victory on ''Twenty-One''.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-rank ...

* '' Halleck: Lincoln's Chief of Staff''

Notes

References

* Anders, Curt ''Henry Halleck's War: A Fresh Look at Lincoln's Controversial General-in-Chief''. Guild Press of Indiana,1999. . * Ambrose, Stephen. '' Halleck: Lincoln's Chief of Staff''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1999. . * Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. ''Civil War High Commands''. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. . * Fredriksen, John C. "Henry Wager Halleck." In ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History'', edited by David S. Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2000. . * Gott, Kendall D. ''Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862''. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. . * Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. ''How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War''. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. . * Marszalek, John F. ''Commander of All Lincoln's Armies: A Life of General Henry W. Halleck''. Boston: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004. . * Nevin, David, and the Editors of Time-Life Books. ''The Road to Shiloh: Early Battles in the West''. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983. . * Smith, Jean Edward. ''Grant''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. . * Schenker, Carl R., Jr. "Ulysses in His Tent: Halleck, Grant, Sherman, and 'The Turning Point of the War'." ''Civil War History'' (June 2010), vol. 56, no. 2, 175. * ''The Union Army; A History of Military Affairs in the Loyal States, 1861–65 — Records of the Regiments in the Union Army — Cyclopedia of Battles — Memoirs of Commanders and Soldiers''Vol. 8

Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing, 1997. First published 1908 by Federal Publishing Company. * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1964. . * Woodworth, Steven E. ''Nothing but Victory: The Army of the Tennessee, 1861–1865''. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. .

California State Military Museum description of Halleck in California

Further reading

* Grant, Ulysses S.br>''Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant''2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. . * Simon, John Y. ''Grant and Halleck: Contrasts in Command''. Frank L. Klement Lectures, No. 5. Milwaukee, WI: Marquette University Press, 1996. .

External links

Biography at Mr. Lincoln's White House

* *

Major General Henry Hallek

at

World Digital Library

The World Digital Library (WDL) is an international digital library operated by UNESCO and the United States Library of Congress.

The WDL has stated that its mission is to promote international and intercultural understanding, expand the volume ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Halleck, Henry Wager

1815 births

1872 deaths

People from Westernville, New York

United States Military Academy alumni

Union Army generals

People of California in the American Civil War

American militia generals

Burials at Green-Wood Cemetery

Union College (New York) alumni

Law in the San Francisco Bay Area

Commanding Generals of the United States Army

19th-century American lawyers