Heinrich Rau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Heinrich Gottlob "Heiner" Rau (2 April 1899 – 23 March 1961) was a German

The revolution in November 1918 led in Württemberg, like everywhere in Germany, to the end of the monarchy. King William II left Stuttgart on 9 November, shortly after a revolutionary crowd had stormed his residence, the Wilhelm Palais and flown a red flag above the building. On the very same day the demonstrators were also able to seize some of Stuttgart's barracks, where parts of the garrisons openly joined them. Rau took active part in the events in Stuttgart's streets on this and the following day.

These happenings were a first cumulation of a civil commotion, that had started a few days earlier with large strikes and demonstrations. On 4 November 1918, a first

The revolution in November 1918 led in Württemberg, like everywhere in Germany, to the end of the monarchy. King William II left Stuttgart on 9 November, shortly after a revolutionary crowd had stormed his residence, the Wilhelm Palais and flown a red flag above the building. On the very same day the demonstrators were also able to seize some of Stuttgart's barracks, where parts of the garrisons openly joined them. Rau took active part in the events in Stuttgart's streets on this and the following day.

These happenings were a first cumulation of a civil commotion, that had started a few days earlier with large strikes and demonstrations. On 4 November 1918, a first

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

politician during the time of the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

; subsequently, during the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

, he was a leading member of the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed ...

and after World War II a leading East German

East Germany, officially the German Democratic Republic (GDR; german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, , DDR, ), was a country that existed from its creation on 7 October 1949 until its dissolution on 3 October 1990. In these years the state ...

statesman.

Rau grew up in a suburb of Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the S ...

, where early on he became active in socialist youth organizations. After military service in World War I, he participated in the German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

of 1918–19. From 1920 onward, he was a leading agricultural policy maker of the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West Germa ...

(KPD). This ended in 1933, when Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

came to power. Shortly afterward Rau was thrown in jail for two years. As an enemy of the Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

regime in Germany he was imprisoned, in total, for more than half of the time of Hitler's rule. After his first imprisonment he emigrated in 1935 to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(USSR). From there, in 1937, he went on to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, where he participated in the Spanish Civil War as a leader of one of the International Brigades. In 1939, he was arrested in France, and was delivered by the Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a spa and resort town and in World War II was the capital of Vichy ...

regime back to Nazi Germany in 1942. After a few months in a Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

prison, he was transferred to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp

Mauthausen was a Nazi concentration camp on a hill above the market town of Mauthausen (roughly east of Linz), Upper Austria. It was the main camp of a group with nearly 100 further subcamps located throughout Austria and southern German ...

in March 1943. While in the concentration camp he participated in conspiratorial prisoner activities, which led to a camp uprising in the final days before the end of World War II in Europe.

After the war he played an important role in the political scene of East Germany. Before the establishment of an East German state he was the chairman of the German Economic Commission

The German Economic Commission (german: Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission; DWK) was the top administrative body in the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany prior to the creation of the German Democratic Republic (german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik). ...

, the precursor to the East German government. Subsequently, he became chairman of the National Planning Commission of East Germany and a deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers. He was a leading economic politician and diplomat of East Germany and led various ministries at different times. Within East Germany's ruling Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germa ...

(SED) he was a member of the party's CC Politburo.

Origins and early political career

Stuttgart

Early years until World War I

Rau was born in Feuerbach, now a part ofStuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the S ...

, in the German Kingdom of Württemberg

The Kingdom of Württemberg (german: Königreich Württemberg ) was a German state that existed from 1805 to 1918, located within the area that is now Baden-Württemberg. The kingdom was a continuation of the Duchy of Württemberg, which exist ...

, the son of a peasant who later became a factory worker. He grew up in the adjacent city of Zuffenhausen, now also a part of Stuttgart. After finishing school in spring 1913, he started work as a press operator in a shoe factory. In November 1913 he changed his employer and moved to the Bosch factory works in Feuerbach. There he completed his training as metal presser and remained until autumn 1920, with interruptions due to war service during 1917-1918 and the subsequent German Revolution

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

of 1918–1919.

From 1913 Rau also was active in the labour movement. In that year he joined the metal workers' union (''Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband'') and a social democratic youth group in Zuffenhausen. During the following years, which saw the beginning of World War I, Rau's youth group, whose leader he became in 1916, was significantly influenced by the left wing of the Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, ; SPD, ) is a centre-left social democratic political party in Germany. It is one of the major parties of contemporary Germany.

Saskia Esken has been ...

(SPD). The leftists considered the war a conflict between "imperialist

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

powers". A few local members of a far left SPD group, among them Edwin Hoernle and Albert Schreiner, who later became well-known members of the Spartacus League

The Spartacus League (German: ''Spartakusbund'') was a Marxist revolutionary movement organized in Germany during World War I. It was founded in August 1914 as the "International Group" by Rosa Luxemburg, Karl Liebknecht, Clara Zetkin, and ...

(''Spartakusbund''), visited the youth group in Zuffenhausen and gave lectures. In 1916, Rau joined the Spartacists as well and became a co-founder of their youth organisation. In accordance with the politics of the Spartacists, in 1917 he joined the left-wing Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany

The Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (german: Unabhängige Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, USPD) was a short-lived political party in Germany during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic. The organization was establis ...

(USPD) and in 1919 the Communist Party of Germany

The Communist Party of Germany (german: Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands, , KPD ) was a major political party in the Weimar Republic between 1918 and 1933, an underground resistance movement in Nazi Germany, and a minor party in West Germa ...

(KPD), which had been founded mainly by members of the Spartacus League.

In spring 1917, Rau, by this time an elected trade union official in his firm, participated in the attempt to organise a strike against the war. His action led to a reprimand from his employer, and may have hastened his conscription into the army in August 1917. In the army he was trained in the Zuffenhausen-garrisoned Infantry Regiment 126 and deployed to the Western Front as member of a machine gun company. In September 1918 a shell splinter penetrated his lungs. In the following weeks, he was treated in military hospitals in Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state of Thuringia, Germany. It is located in Central Germany between Erfurt in the west and Jena in the east, approximately southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together with the neighbourin ...

and in Stuttgart's neighbouring town Ludwigsburg

Ludwigsburg (; Swabian: ''Ludisburg'') is a city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, about north of Stuttgart city centre, near the river Neckar. It is the largest and primary city of the Ludwigsburg district with about 88,000 inhabitants. It is ...

. While in Ludwigsburg, Rau managed to get leave at short notice on 8 November 1918 and joined the in those days developing revolution in Stuttgart.

Revolution

The revolution in November 1918 led in Württemberg, like everywhere in Germany, to the end of the monarchy. King William II left Stuttgart on 9 November, shortly after a revolutionary crowd had stormed his residence, the Wilhelm Palais and flown a red flag above the building. On the very same day the demonstrators were also able to seize some of Stuttgart's barracks, where parts of the garrisons openly joined them. Rau took active part in the events in Stuttgart's streets on this and the following day.

These happenings were a first cumulation of a civil commotion, that had started a few days earlier with large strikes and demonstrations. On 4 November 1918, a first

The revolution in November 1918 led in Württemberg, like everywhere in Germany, to the end of the monarchy. King William II left Stuttgart on 9 November, shortly after a revolutionary crowd had stormed his residence, the Wilhelm Palais and flown a red flag above the building. On the very same day the demonstrators were also able to seize some of Stuttgart's barracks, where parts of the garrisons openly joined them. Rau took active part in the events in Stuttgart's streets on this and the following day.

These happenings were a first cumulation of a civil commotion, that had started a few days earlier with large strikes and demonstrations. On 4 November 1918, a first workers' council

A workers' council or labor council is a form of political and economic organization in which a workplace or municipality is governed by a council made up of workers or their elected delegates. The workers within each council decide on what thei ...

under the leadership of the 23-year-old Spartacist Fritz Rück had been established in Stuttgart.For Fritz Rück and the workers' councils in Württemberg, see

*

For Albert Schreiner and the soldiers' councils in Württemberg, see

* During the following days and weeks more spontaneously elected worker and soldier councils were formed, and took over a large part of Württemberg. Rau was elected leader of the military police in his home city of Zuffenhausen, a part of Stuttgart's urban area.

As early as 9 November, about 150 councillors gathered for a two-day meeting in Stuttgart. A majority of the councillors entrusted the leaders of the SPD and USPD political parties, who had been invited to the meeting, with the establishment of a provisional government in Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Württ ...

. The Spartacist Albert Schreiner, then chairman of a soldier council, initially assumed the key position of Minister of War in this quickly established first government, which for the time being shared power with the councils. However, he resigned already a few days later, after disputes about the future course of the government. While the Spartacists considered as their ideal aim the kinds of results achieved by the previous year's October Revolution

The October Revolution,. officially known as the Great October Socialist Revolution. in the Soviet Union, also known as the Bolshevik Revolution, was a revolution in Russia led by the Bolshevik Party of Vladimir Lenin that was a key moment ...

in Russia, the position of the other USPD politicians was unclear and the SPD leaders supported a parliamentary democracy and early elections in Württemberg.

During the ensuing months the communists tried repeatedly to seize power in Stuttgart and other cities in Württemberg through armed rebellion, accompanied by large-scale strikes. They seized public buildings and print offices. During one such an attempt - at the beginning of April 1919 when the Bavarian Soviet Republic

The Bavarian Soviet Republic, or Munich Soviet Republic (german: Räterepublik Baiern, Münchner Räterepublik),Hollander, Neil (2013) ''Elusive Dove: The Search for Peace During World War I''. McFarland. p.283, note 269. was a short-lived unre ...

was formally proclaimed in Munich

Munich ( ; german: München ; bar, Minga ) is the capital and most populous city of the German state of Bavaria. With a population of 1,558,395 inhabitants as of 31 July 2020, it is the third-largest city in Germany, after Berlin and H ...

- a general strike took place in the Stuttgart area. The government in Stuttgart imposed a state of emergency and 16 people died in street fights. At the time of these events, Rau used his position as chief of the military police in Zuffenhausen to shut down companies that remained operational while the strike was ongoing. However, when the strike collapsed, Rau was removed from office by the government.

Rau resumed his employment at Bosch in Feuerbach. During another general strike in several Württemberg cities, from 28 August to 4 September 1920, he led the strike committee in his firm, which resulted in his dismissal.

Influences

From 1919 until 1920 Rau was head of the local KPD group in Zuffenhausen, and chaired the KPD organisation in Stuttgart. The party leader inWürttemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Württ ...

at this time was Edwin Hoernle. Hoernle had visited Rau's youth group in Zuffenhausen and had become a long-standing friend; he was an influential teacher for Rau and made his voluminous library available to Rau to use.For Edwin Hoernle (short biographies), see

*

*

For Hoernle as member of the ECCI in 1922, see:

* / Extraction:

The most outstanding ideological authority of the movement in Stuttgart, during the time of Rau's political involvement there, was however Clara Zetkin

Clara Zetkin (; ; ''née'' Eißner ; 5 July 1857 – 20 June 1933) was a German Marxist theorist, communist activist, and advocate for women's rights.

Until 1917, she was active in the Social Democratic Party of Germany. She then joined the I ...

. She was a founding member of the Second International

The Second International (1889–1916) was an organisation of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties, formed on 14 July 1889 at two simultaneous Paris meetings in which delegations from twenty countries participated. The Second Internatio ...

, about whom Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

''

After the outbreak of the

After the outbreak of the

In September 1945, the Soviets appointed Rau a member of the provisional chairmanship of the Province of

In September 1945, the Soviets appointed Rau a member of the provisional chairmanship of the Province of

In March 1948 Rau became chairman of the

In March 1948 Rau became chairman of the

Likewise in 1949, the ruling SED implemented traditional leadership structures of communist parties and Rau became a member of the newly established Central Committee of the SED and candidate member of its Politburo; in 1950 he became a full member of the Politburo as well as deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers.

Between 1949 and 1950, Rau was Minister for Planning of the GDR and in 1950–1952 chairman of the National Planning Commission. In this position, as the key figure of the economic development, Rau came into conflict with SED

Likewise in 1949, the ruling SED implemented traditional leadership structures of communist parties and Rau became a member of the newly established Central Committee of the SED and candidate member of its Politburo; in 1950 he became a full member of the Politburo as well as deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers.

Between 1949 and 1950, Rau was Minister for Planning of the GDR and in 1950–1952 chairman of the National Planning Commission. In this position, as the key figure of the economic development, Rau came into conflict with SED

Unlike some other rebels in the leadership, Rau kept most of his positions. He remained a member of the Politburo and deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. In the Politburo he continued to be responsible for the industry of the GDR. However, his position had been weakened. Bruno Leuschner, a follower of Ulbricht and Rau's successor as chairman of the National Planning Commission, now became a new candidate member of the Politburo. During the ensuing period, Leuschner, often supported by Ulbricht, gradually superseded Rau as the senior leader for the economy as a whole. The official GDR press never mentioned the dissension between Rau and Leuschner and always described their cooperation as a success story.

Concentrating on his tasks in the SED leadership and as a minister, Rau – despite occasional internal criticism – avoided giving the impression of any disagreement with Ulbricht, at least in public. In 1954, Rau received in the Order of Merit for the Fatherland (''Vaterländischer Verdienstorden'') in gold. Later, Ulbricht stated in a 1964 interview about the "introduction of socialism" in the GDR, that only three people were heavily involved in the economic development during that time, "namely Heinrich Rau, Bruno Leuschner and me. Others were not consulted!"

In 1953–1955 Rau led the new established Ministry for Machine Construction, which combined the responsibilities of three existing ministries. His deputy in this ministry was Erich Apel, who would, in the early 1960s, become an initiator and architect of an economic reform, which became known as the New Economic System (NES).

This later reform was presaged by a reform in the middle of the 1950s; the economic historian Jörg Roesler considers the NES in the 1960s as a continuation of this reform. The origin of the reform in the 1950s was a scientific study, commissioned by Rau's ministry in 1953, to assess the need for greater economic efficiency in the factories. The subsequent results from this study promised enhanced economic efficiency by shifting more responsibility from the National Planning Commission to the enterprises themselves. Thenceforward, already in spring 1954, Rau advocated such a planning reform, while planning boss Bruno Leuschner quite consistently opposed it. In August 1954, Rau's ministry sent a concept for such a reform to Leuschner's State Planning Commission. Eventually this reform got under way, after Ulbricht, perhaps under the influence of his new personal economic adviser Wolfgang Berger, had approved such a policy at the end of 1954 too. Subsequently, the reform accelerated until 1956. It found however its early end in the generally aggravated political atmosphere in 1957. Unrests in other Eastern Bloc countries during the previous year 1956, in particular in Hungary, had awoken the desire for more central control again. The subsequent unsatisfying economic development, however, during the following years eventually led in the 1960s to the concept of a new planning reform, the NES.

Unlike some other rebels in the leadership, Rau kept most of his positions. He remained a member of the Politburo and deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. In the Politburo he continued to be responsible for the industry of the GDR. However, his position had been weakened. Bruno Leuschner, a follower of Ulbricht and Rau's successor as chairman of the National Planning Commission, now became a new candidate member of the Politburo. During the ensuing period, Leuschner, often supported by Ulbricht, gradually superseded Rau as the senior leader for the economy as a whole. The official GDR press never mentioned the dissension between Rau and Leuschner and always described their cooperation as a success story.

Concentrating on his tasks in the SED leadership and as a minister, Rau – despite occasional internal criticism – avoided giving the impression of any disagreement with Ulbricht, at least in public. In 1954, Rau received in the Order of Merit for the Fatherland (''Vaterländischer Verdienstorden'') in gold. Later, Ulbricht stated in a 1964 interview about the "introduction of socialism" in the GDR, that only three people were heavily involved in the economic development during that time, "namely Heinrich Rau, Bruno Leuschner and me. Others were not consulted!"

In 1953–1955 Rau led the new established Ministry for Machine Construction, which combined the responsibilities of three existing ministries. His deputy in this ministry was Erich Apel, who would, in the early 1960s, become an initiator and architect of an economic reform, which became known as the New Economic System (NES).

This later reform was presaged by a reform in the middle of the 1950s; the economic historian Jörg Roesler considers the NES in the 1960s as a continuation of this reform. The origin of the reform in the 1950s was a scientific study, commissioned by Rau's ministry in 1953, to assess the need for greater economic efficiency in the factories. The subsequent results from this study promised enhanced economic efficiency by shifting more responsibility from the National Planning Commission to the enterprises themselves. Thenceforward, already in spring 1954, Rau advocated such a planning reform, while planning boss Bruno Leuschner quite consistently opposed it. In August 1954, Rau's ministry sent a concept for such a reform to Leuschner's State Planning Commission. Eventually this reform got under way, after Ulbricht, perhaps under the influence of his new personal economic adviser Wolfgang Berger, had approved such a policy at the end of 1954 too. Subsequently, the reform accelerated until 1956. It found however its early end in the generally aggravated political atmosphere in 1957. Unrests in other Eastern Bloc countries during the previous year 1956, in particular in Hungary, had awoken the desire for more central control again. The subsequent unsatisfying economic development, however, during the following years eventually led in the 1960s to the concept of a new planning reform, the NES.

Between 1955 and 1961 Rau served as Minister for Foreign Trade and Inter-German Trade. The term "Inter-German Trade" meant the trade with

Between 1955 and 1961 Rau served as Minister for Foreign Trade and Inter-German Trade. The term "Inter-German Trade" meant the trade with

''

Wilhelm II

, house = Hohenzollern

, father = Frederick III, German Emperor

, mother = Victoria, Princess Royal

, religion = Lutheranism (Prussian United)

, signature = Wilhelm II, German Emperor Signature-.svg

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor ...

is said to have referred to her as the "worst witch in Germany".For Engels' letter to Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

' daughter Laura Lafargue, where he writes about Clara Zetkin, see

* / Extraction: Speech manuscript of a lecture by the Stuttgart local historian Dr. Hans-Georg Müller in Stuttgart-Sillenbuch on 16 November 1995. She had been living in a Stuttgart suburb since 1891 and, since then, been gathering a circle of Württemberg Marxists

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectic ...

around her, among them Rau's friend Hoernle, who had been editing with her the magazine '' Die Gleichheit''. Her house, built in 1903 in Sillenbuch (now a part of Stuttgart), had become a meeting place of leading national and local left-wing and communist activists. It was also visited by international communist leaders like Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

, who stayed there overnight in 1907. In 1920, when Zetkin was elected to the Reichstag in Berlin, Hoernle and Rau moved to Berlin as well.

Berlin

In November 1920 Rau became a full-time party functionary and the secretary of the agricultural division of theCentral Committee

Central committee is the common designation of a standing administrative body of communist parties, analogous to a board of directors, of both ruling and nonruling parties of former and existing socialist states. In such party organizations, the c ...

of the KPD in Berlin. Between 1921 and 1930 he lectured at the Land

Land, also known as dry land, ground, or earth, is the solid terrestrial surface of the planet Earth that is not submerged by the ocean or other bodies of water. It makes up 29% of Earth's surface and includes the continents and various islan ...

and Federal schools of the KPD, and edited a few left-wing agricultural journals.

The head of the Central Committee's Division for Agriculture initially was Edwin Hoernle, with whom Rau had come from Stuttgart. Hoernle had been elected to the Executive Committee of the Comintern (ECCI) in November 1922 and Rau succeeded him as division chief the following year. Afterwards, Rau also became a leading member of various national and international left wing farmer and peasant organisations. From 1923 onward, he was a member of the Secretariat of the International Committee of the Agricultural and Forest Workers and beginning in 1924 of the executive committee of the Reich Peasant Federation (''Reichsbauernbund''). In 1930 this was followed with a membership on the International Peasants' Council in Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 millio ...

and in 1931 he became an office member of the European Peasant Committee. From 1928 to 1933 he was also member of the Preußischer Landtag

The Landtag of Prussia (german: Preußischer Landtag) was the representative assembly of the Kingdom of Prussia implemented in 1849, a bicameral legislature consisting of the upper House of Lords (''Herrenhaus'') and the lower House of Representa ...

, the Prussian federal state parliament. There he joined the committee on agricultural affairs of the parliament and became its chairman.

Imprisonment, International Brigades, World War II

After Hitler's rise to power in January 1933 and the subsequent suppression of the KPD, Rau became a Central Committee's party instructor for southwest Germany and was active in building an underground party organisation there. On 23 May 1933 Rau was arrested and on 11 December 1934 convicted, together with Bernhard Bästlein, for "preparations to commit high treason" by the People's Court of Germany. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment. After his release from custody, he emigrated to theUSSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

in August 1935, via Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, and became a deputy chairman of the International Agrarian Institute in Moscow.

After the outbreak of the

After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

and following the formation of the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed ...

, Rau attended a school for military commanders in Ryazan

Ryazan ( rus, Рязань, p=rʲɪˈzanʲ, a=ru-Ryazan.ogg) is the largest city and administrative center of Ryazan Oblast, Russia. The city is located on the banks of the Oka River in Central Russia, southeast of Moscow. As of the 2010 Ce ...

(USSR), and subsequently went to Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

. After his arrival in April 1937, he joined the XI International Brigade and participated in the civil war as political commissar, beginning in May 1937, then as chief of staff and finally commander of the brigade, until March 1938, when he was injured.

Although the brigade achieved some temporary successes during these months, Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from ...

's troops were already on the road to victory. Rau's brigade saw combat in the battles of Brunete

Brunete () is a town located on the outskirts of Madrid, Spain with a population of 10,730 people.

History

There was no military garrison in Brunete and there was no rebel attempt to seize the city during the coup of July 1936. Brunete remain ...

, Belchite, Teruel and the Aragon Offensive

The Aragon Offensive was an important military campaign during the Spanish Civil War, which began after the Battle of Teruel. The offensive, which ran from March 7, 1938, to April 19, 1938, smashed the Republican forces, overran Aragon, and conq ...

, where Rau was wounded. / Extraction:

When Rau took charge of the XI Brigade, he might have been at odds with his predecessor, Richard Staimer, the future son-in-law of KPD leader Wilhelm Pieck. This was the time of the Great Purge

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secret ...

which had its echos in Spain, and it could be perilous to have powerful enemies. André Marty

André Marty (6 November 1886 – 23 November 1956) was a leading figure in the French Communist Party (PCF) for nearly thirty years. He was also a member of the National Assembly, with some interruptions, from 1924 to 1955; Secretary of Comintern ...

, the chief commissar of the International Brigades based at Albacete

Albacete (, also , ; ar, ﭐَلبَسِيط, Al-Basīṭ) is a city and municipality in the Spanish autonomous community of Castilla–La Mancha, and capital of the province of Albacete.

Lying in the south-east of the Iberian Peninsula, the ...

, was also an executor of the Great Purge in Spain. Following Rau's injury, Marty managed to imprison him under a pretext for a brief time. A report, written in Moscow in 1940, described Rau as a "political criminal", who had had contact with the Spanish anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

and members of the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification (POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification ( es, Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, POUM; ca, Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Republic and mainly active around the Spanish Civil ...

), which was demonized as "Trotskyist". These were serious allegations in this time, when accusations of Trotskyism frequently led to a death sentence if the accused was within reach of the authorities.

It seems, however, that Rau also had influential friends. He was released from prison and expelled from Spain. He moved to France in May 1938. There, he was in charge of the emergency committee of the German and Austrian Spain fighters and member of the KPD country leadership in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

until 1939. At the beginning of 1939 Rau crossed the border to Spain again and subsequently led, together with Ludwig Renn, the remainders of the XI Brigade. Together with other remaining international units – now combined in the " Agrupación Internacional" – they fought on Spain's northern border after the fall of Barcelona, protecting the stream of refugees escaping to France. Thus the Agrupación enabled the escape of perhaps some 470,000 civilians and soldiers.

Rau was arrested by the French authorities in September 1939 and sent to Camp Vernet

Le Vernet Internment Camp, or Camp Vernet, was a concentration camp in Le Vernet, Ariège, near Pamiers, in the French Pyrenees. Built in 1918 as a barracks but after WWI used as an internment camp for prisoners of war. From February 1939 to June ...

, an internment centre in France, and in November 1941 to a secret prison in Castres

Castres (; ''Castras'' in the Languedocian dialect of Occitan) is the sole subprefecture of the Tarn department in the Occitanie region in Southern France. It lies in the former province of Languedoc, although not in the former region of Langue ...

. In June 1942, he was handed over to the Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

by the Vichy

Vichy (, ; ; oc, Vichèi, link=no, ) is a city in the Allier department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of central France, in the historic province of Bourbonnais.

It is a spa and resort town and in World War II was the capital of Vichy ...

regime and was held until March 1943 in the Gestapo prison in the Prince Albrecht Street. Afterwards he was sent to the Mauthausen Concentration Camp

Mauthausen was a Nazi concentration camp on a hill above the market town of Mauthausen (roughly east of Linz), Upper Austria. It was the main camp of a group with nearly 100 further subcamps located throughout Austria and southern German ...

, where he remained until May 1945, when he participated in a camp rebellion as one of the organisers of a secret military camp organisation.

East Germany

1945–1949

New start in Brandenburg

When the war was over, Rau went toVienna

en, Viennese

, iso_code = AT-9

, registration_plate = W

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code =

, timezone = CET

, utc_offset = +1

, timezone_DST ...

for some weeks and helped the KPD representatives in the city gather liberated political prisoners from Germany. He left Vienna in July 1945, when he led a car convoy with 120 former Mauthausen inmates to the Soviet occupied part of Berlin.

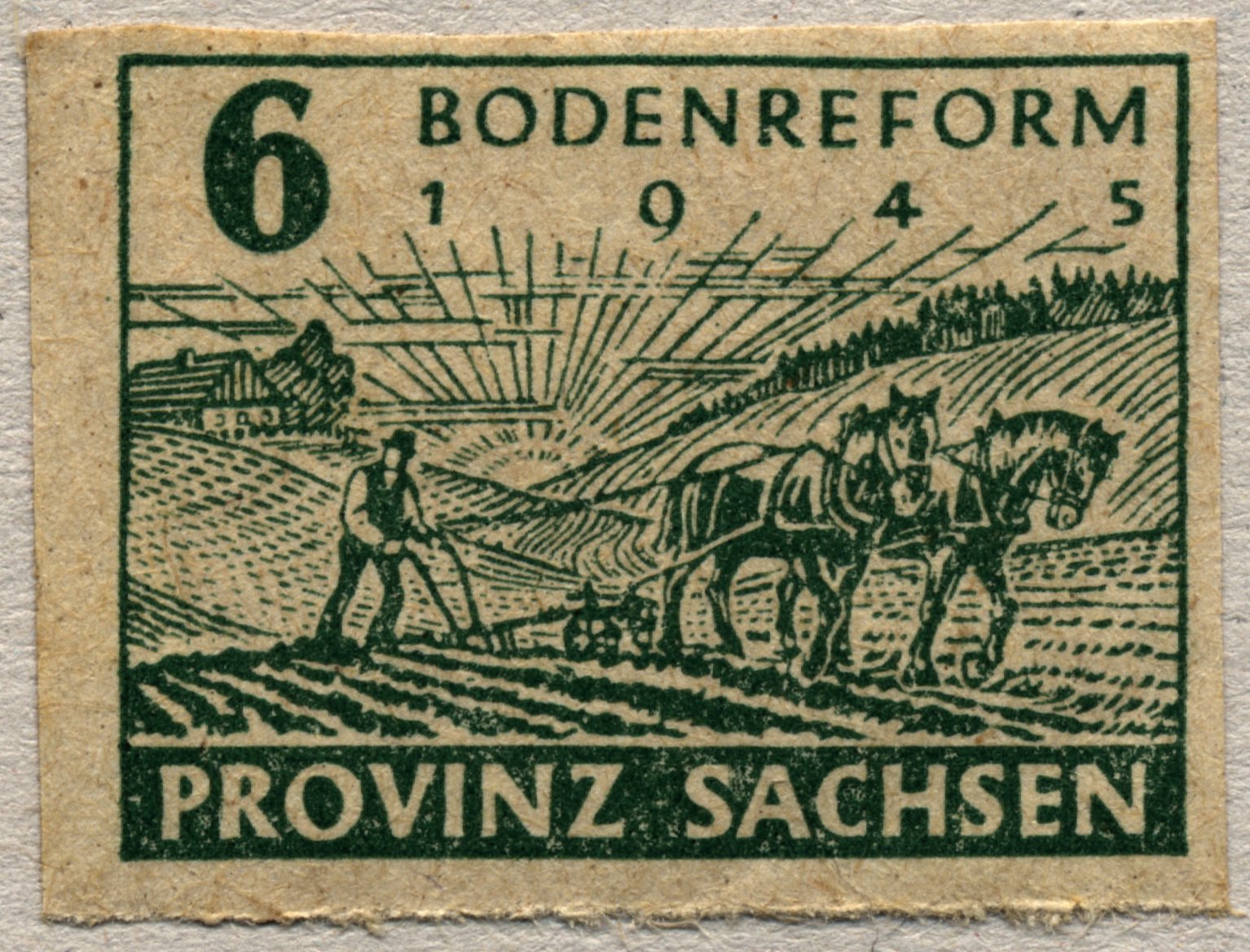

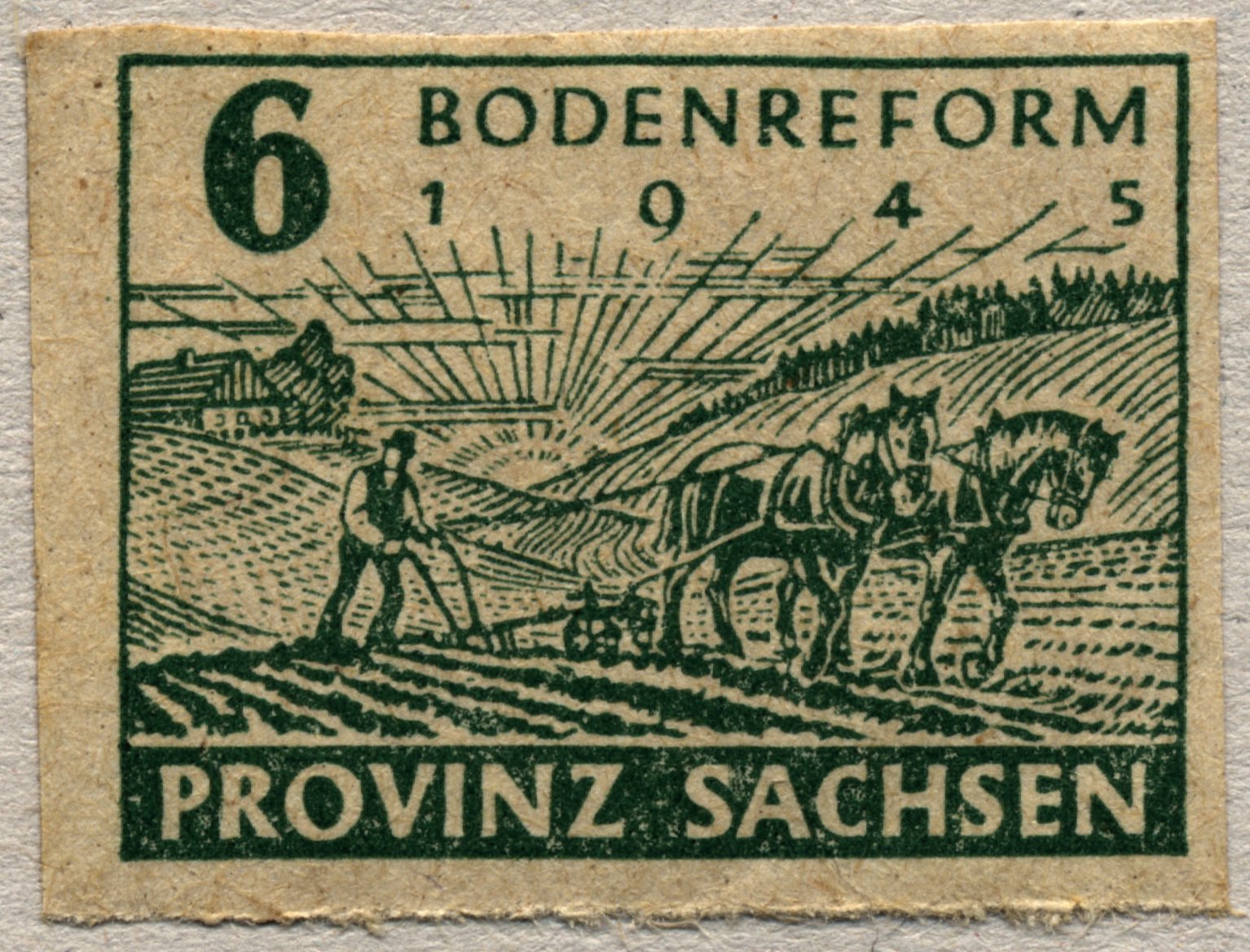

In September 1945, the Soviets appointed Rau a member of the provisional chairmanship of the Province of

In September 1945, the Soviets appointed Rau a member of the provisional chairmanship of the Province of Brandenburg

Brandenburg (; nds, Brannenborg; dsb, Bramborska ) is a state in the northeast of Germany bordering the states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Lower Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, and Saxony, as well as the country of Poland. With an area of 29,480 square ...

with the title of a vice-president and responsibility for food, agriculture and forests. Rau succeeded Edwin Hoernle, who had held this position since the end of June and became chairman of the central administration for agriculture and forests in the Soviet Occupation Zone

The Soviet Occupation Zone ( or german: Ostzone, label=none, "East Zone"; , ''Sovetskaya okkupatsionnaya zona Germanii'', "Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany") was an area of Germany in Central Europe that was occupied by the Soviet Union as a ...

(SBZ). In his new position, Rau was a member of the commission for the execution of the land reform

Land reform is a form of agrarian reform involving the changing of laws, regulations, or customs regarding land ownership. Land reform may consist of a government-initiated or government-backed property redistribution, generally of agricultural ...

in the province. In spring 1946 he assumed responsibility for

economy and transport in Brandenburg. In this capacity, he was, from June 1946 onwards, chairman of the newly established sequester commission in the province. 1946 was also the year of the forced merger of eastern KPD and eastern SPD into the Socialist Unity Party of Germany

The Socialist Unity Party of Germany (german: Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, ; SED, ), often known in English as the East German Communist Party, was the founding and ruling party of the German Democratic Republic (GDR; East Germa ...

(SED), resulting in Rau's membership in the SED. Important 1946 events in Brandenburg were in November elections, which preceded an official status change from a province to a federal state in the following year. Afterwards, from 1946 until 1948, Rau was state parliament delegate and Minister for Economic Planning of Brandenburg.

German Economic Commission

In March 1948 Rau became chairman of the

In March 1948 Rau became chairman of the German Economic Commission

The German Economic Commission (german: Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission; DWK) was the top administrative body in the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany prior to the creation of the German Democratic Republic (german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik). ...

(''Deutsche Wirtschaftskommission'' or ''DWK''), which during this period became the centralised administrative organisation for the Soviet Occupation Zone and the predecessor of the future East German government. The organisation existed during a time of very difficult challenges coming from different sides. A particularly momentous event during this time was the currency reform of 1948. On 20 June 1948 the western German zones introduced a new currency, leaving the eastern zone to use the old common currency. In order to avoid inflation, the DWK under Rau's leadership, was forced to follow quickly with its own reform and issued an own currency too. In doing so, the DWK also exploited the currency reform to redistribute capital by using different exchange rates for private and state-run companies. The disagreement, which of the two new currencies should be used in Berlin, triggered the Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

by the USSR and the western airborne supply of West Berlin

West Berlin (german: Berlin (West) or , ) was a political enclave which comprised the western part of Berlin during the years of the Cold War. Although West Berlin was de jure not part of West Germany, lacked any sovereignty, and was under ...

.

Under Rau's leadership the DWK, still under supervision of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany

The Soviet Military Administration in Germany (russian: Советская военная администрация в Германии, СВАГ; ''Sovyetskaya Voyennaya Administratsiya v Germanii'', SVAG; german: Sowjetische Militäradministrat ...

(German: Sowjetische Militäradministration in Deutschland or SMAD), quickly developed more and more into a partner of the SMAD with its own conceptions and intentions. This policy was also endorsed by the Soviet chief diplomat in Germany, Vladimir Semyonov, the future Chief Commissar of the USSR in Germany, who already in January 1948 correspondingly stated, that SMAD orders, (which accompanied DWK orders,) should have merely the purpose to back the authority of the German orders. One of Rau's aims during the meetings with the SMAD was, to come to agreements, which also obliged the Soviet side, including subordinate Soviet authorities, who still engaged in wild confiscations for reparation purposes. An important success in this direction was a half-year plan for the economic development in the second half of 1948, which was accepted by the SMAD in May 1948. It was followed by a likewise accepted two-year plan for 1949 and 1950.

The biggest obstacle to the plan's implementation soon proved to be the Berlin Blockade by the USSR, which was followed by a western counter-blockade of the Soviet occupation zone. As there were long-established economic ties between the western zone and the eastern, which was highly dependent on supplies from the West, the blockade was more damaging to the East. The West Berlin SPD newspaper ''Sozialdemokrat'' reported in April 1949, how Rau clearly criticized the blockade in a meeting of SED apparatchiks and there is reason to believe that he did the same in the meetings with the SMAD. According to the paper, Rau spoke of a "bad speculation" regarding the undervaluation of the dependence on western supplies, stating that the "broadminded Soviet help" turned out as insufficient and hinting that the blockade would soon be lifted. Finally the Berlin Blockade was lifted on 12 May 1949.

The DWK's increasingly centralised administration resulted in a substantial increase in its staffing level, which grew from about 5000 employees in mid-1948 to 10,000 by the beginning of 1949. In March 1949, Rau, like the representative of a state, signed a first treaty with a foreign state, a trade agreement with Poland.

1949–1953

Establishment and difficult first years of a new state

The time of Rau's German Economic Commission ended in October 1949 with the establishment of the East German state, theGerman Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

(GDR). The GDR was proclaimed on 7 October 1949, at a ceremony in the former Air Ministry Building in Berlin, until then the seat of Rau's organisation. Five days later, the DWK was formally abolished on 12 October 1949. Rau thereupon became a delegate of the People's Chamber

__NOTOC__

The Volkskammer (, ''People's Chamber'') was the unicameral legislature of the German Democratic Republic (colloquially known as East Germany).

The Volkskammer was initially the lower house of a bicameral legislature. The upper house w ...

, the newly established parliament of the GDR and joined the new government.

Likewise in 1949, the ruling SED implemented traditional leadership structures of communist parties and Rau became a member of the newly established Central Committee of the SED and candidate member of its Politburo; in 1950 he became a full member of the Politburo as well as deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers.

Between 1949 and 1950, Rau was Minister for Planning of the GDR and in 1950–1952 chairman of the National Planning Commission. In this position, as the key figure of the economic development, Rau came into conflict with SED

Likewise in 1949, the ruling SED implemented traditional leadership structures of communist parties and Rau became a member of the newly established Central Committee of the SED and candidate member of its Politburo; in 1950 he became a full member of the Politburo as well as deputy chairman of the East German Council of Ministers.

Between 1949 and 1950, Rau was Minister for Planning of the GDR and in 1950–1952 chairman of the National Planning Commission. In this position, as the key figure of the economic development, Rau came into conflict with SED General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the organization. The term is derived ...

Walter Ulbricht

Walter Ernst Paul Ulbricht (; 30 June 18931 August 1973) was a German communist politician. Ulbricht played a leading role in the creation of the Weimar-era Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and later (after spending the years of Nazi rule in ...

. In the face of an imminent economic collapse, Rau blamed the "Bureau Ulbricht" for the wrong policy. In response East Germany's old president Wilhelm Pieck renewed the old accusation of Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a r ...

against Rau. In a later letter to Pieck of 28 November 1951, Rau protested at the manner in which the Secretariat usurped the Politburo by censoring his speech on economic affairs.

In 1952–1953, Rau led the newly established Coordination Centre for Industry and Traffic at the East German Council of Ministers. The purpose of this office was effective control of the economy in order to overcome the difficulties, which were caused by a grown bureaucracy and unclear decision paths. Prime Minister Otto Grotewohl described this in a talk with Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as General Secreta ...

.

After the death of Stalin in March 1953, the new collective Soviet leadership started to advocate a New Course. Moscow favored replacing East Germany's Stalinist party leader Walter Ulbricht and made inquiries about Rau as a potential candidate. In response, the leading SED party ideologist, Rudolf Herrnstadt, a candidate member of the Poliburo, with assistance from Rau drew up a concept for just such a New Course in East Germany. However, the workers' uprising, which was suppressed by the Soviet army on 17 June led to a backlash. Three weeks later, during a session of the then eight person Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the executive committee for communist parties. It is present in most former and existing communist states.

Names

The term "politburo" in English comes from the Russian ''Politbyuro'' (), itself a contraction ...

(plus six candidate members) on 8 July 1953, Rau made a recommendation that Ulbricht be replaced, while Rau's Spanish Civil War comrade, Stasi

The Ministry for State Security, commonly known as the (),An abbreviation of . was the state security service of the East Germany from 1950 to 1990.

The Stasi's function was similar to the KGB, serving as a means of maintaining state authori ...

chief Wilhelm Zaisser

Wilhelm Zaisser (20 June 1893 – 3 March 1958) was a German communist politician and statesman who served as the founder and first Minister for State Security of the German Democratic Republic (1950–1953).

Early life

Born in Gelsenkirch ...

, who in Spain had been known as 'General Gómez', accused Ulbricht of having perverted the party. The majority was against Ulbricht. His only supporters were Hermann Matern and Erich Honecker

Erich Ernst Paul Honecker (; 25 August 1912 – 29 May 1994) was a German communist politician who led the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) from 1971 until shortly before the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. He held the posts ...

. At that moment however there was no viable candidate who could replace Ulbricht immediately. Suggested were first Rudolf Herrnstadt and then Heinrich Rau, but both were hesitant, thus a decision was postponed. The very next day after the meeting Ulbricht went by plane to Moscow and the Soviet leadership, who in part also feared that deposing Ulbricht might be construed as a sign of weakness, now secured Ulbricht's position. Subsequently, five members and candidate members of the Politburo lost their positions.

1953–1961

Competition in the Politburo and economic reform

Unlike some other rebels in the leadership, Rau kept most of his positions. He remained a member of the Politburo and deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. In the Politburo he continued to be responsible for the industry of the GDR. However, his position had been weakened. Bruno Leuschner, a follower of Ulbricht and Rau's successor as chairman of the National Planning Commission, now became a new candidate member of the Politburo. During the ensuing period, Leuschner, often supported by Ulbricht, gradually superseded Rau as the senior leader for the economy as a whole. The official GDR press never mentioned the dissension between Rau and Leuschner and always described their cooperation as a success story.

Concentrating on his tasks in the SED leadership and as a minister, Rau – despite occasional internal criticism – avoided giving the impression of any disagreement with Ulbricht, at least in public. In 1954, Rau received in the Order of Merit for the Fatherland (''Vaterländischer Verdienstorden'') in gold. Later, Ulbricht stated in a 1964 interview about the "introduction of socialism" in the GDR, that only three people were heavily involved in the economic development during that time, "namely Heinrich Rau, Bruno Leuschner and me. Others were not consulted!"

In 1953–1955 Rau led the new established Ministry for Machine Construction, which combined the responsibilities of three existing ministries. His deputy in this ministry was Erich Apel, who would, in the early 1960s, become an initiator and architect of an economic reform, which became known as the New Economic System (NES).

This later reform was presaged by a reform in the middle of the 1950s; the economic historian Jörg Roesler considers the NES in the 1960s as a continuation of this reform. The origin of the reform in the 1950s was a scientific study, commissioned by Rau's ministry in 1953, to assess the need for greater economic efficiency in the factories. The subsequent results from this study promised enhanced economic efficiency by shifting more responsibility from the National Planning Commission to the enterprises themselves. Thenceforward, already in spring 1954, Rau advocated such a planning reform, while planning boss Bruno Leuschner quite consistently opposed it. In August 1954, Rau's ministry sent a concept for such a reform to Leuschner's State Planning Commission. Eventually this reform got under way, after Ulbricht, perhaps under the influence of his new personal economic adviser Wolfgang Berger, had approved such a policy at the end of 1954 too. Subsequently, the reform accelerated until 1956. It found however its early end in the generally aggravated political atmosphere in 1957. Unrests in other Eastern Bloc countries during the previous year 1956, in particular in Hungary, had awoken the desire for more central control again. The subsequent unsatisfying economic development, however, during the following years eventually led in the 1960s to the concept of a new planning reform, the NES.

Unlike some other rebels in the leadership, Rau kept most of his positions. He remained a member of the Politburo and deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers. In the Politburo he continued to be responsible for the industry of the GDR. However, his position had been weakened. Bruno Leuschner, a follower of Ulbricht and Rau's successor as chairman of the National Planning Commission, now became a new candidate member of the Politburo. During the ensuing period, Leuschner, often supported by Ulbricht, gradually superseded Rau as the senior leader for the economy as a whole. The official GDR press never mentioned the dissension between Rau and Leuschner and always described their cooperation as a success story.

Concentrating on his tasks in the SED leadership and as a minister, Rau – despite occasional internal criticism – avoided giving the impression of any disagreement with Ulbricht, at least in public. In 1954, Rau received in the Order of Merit for the Fatherland (''Vaterländischer Verdienstorden'') in gold. Later, Ulbricht stated in a 1964 interview about the "introduction of socialism" in the GDR, that only three people were heavily involved in the economic development during that time, "namely Heinrich Rau, Bruno Leuschner and me. Others were not consulted!"

In 1953–1955 Rau led the new established Ministry for Machine Construction, which combined the responsibilities of three existing ministries. His deputy in this ministry was Erich Apel, who would, in the early 1960s, become an initiator and architect of an economic reform, which became known as the New Economic System (NES).

This later reform was presaged by a reform in the middle of the 1950s; the economic historian Jörg Roesler considers the NES in the 1960s as a continuation of this reform. The origin of the reform in the 1950s was a scientific study, commissioned by Rau's ministry in 1953, to assess the need for greater economic efficiency in the factories. The subsequent results from this study promised enhanced economic efficiency by shifting more responsibility from the National Planning Commission to the enterprises themselves. Thenceforward, already in spring 1954, Rau advocated such a planning reform, while planning boss Bruno Leuschner quite consistently opposed it. In August 1954, Rau's ministry sent a concept for such a reform to Leuschner's State Planning Commission. Eventually this reform got under way, after Ulbricht, perhaps under the influence of his new personal economic adviser Wolfgang Berger, had approved such a policy at the end of 1954 too. Subsequently, the reform accelerated until 1956. It found however its early end in the generally aggravated political atmosphere in 1957. Unrests in other Eastern Bloc countries during the previous year 1956, in particular in Hungary, had awoken the desire for more central control again. The subsequent unsatisfying economic development, however, during the following years eventually led in the 1960s to the concept of a new planning reform, the NES.

Foreign trade and foreign policy

Between 1955 and 1961 Rau served as Minister for Foreign Trade and Inter-German Trade. The term "Inter-German Trade" meant the trade with

Between 1955 and 1961 Rau served as Minister for Foreign Trade and Inter-German Trade. The term "Inter-German Trade" meant the trade with West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 ...

. In this time both German states still saw German reunification as their own aim, but both envisaging different political systems. The West German position was that they, as the only freely elected government, had an exclusive mandate for the entire German people. In consequence of this, the GDR's official diplomatic relationships with other states were narrowed to the states of the Eastern Bloc. Practically no other states recognized the GDR. As a result, Rau's ministry established numerous new "trade missions" in other states, which served as a kind of surrogate for nonexistent embassies. It was a corollary, that Rau, in addition to his responsibility for the export-oriented industry, also chaired the Foreign Policy Commission of the SED Politburo (''Außenpolitische Kommission beim Politbüro'' or ''APK'') since 1955, in this period the actual decision-making body for foreign affairs, and visited other states in different parts of the world in this capacity. Among the visited states were, beside the core states of the Soviet Bloc

The Eastern Bloc, also known as the Communist Bloc and the Soviet Bloc, was the group of socialist states of Central and Eastern Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Latin America under the influence of the Soviet Union that existed du ...

, also then Eastern Bloc peripheral states, like China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

and Albania

Albania ( ; sq, Shqipëri or ), or , also or . officially the Republic of Albania ( sq, Republika e Shqipërisë), is a country in Southeastern Europe. It is located on the Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea and shares l ...

and leading states of the crystallizing Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

like India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

and Yugoslavia

Yugoslavia (; sh-Latn-Cyrl, separator=" / ", Jugoslavija, Југославија ; sl, Jugoslavija ; mk, Југославија ;; rup, Iugoslavia; hu, Jugoszlávia; rue, label= Pannonian Rusyn, Югославия, translit=Juhoslavij ...

(after the Bandung Conference

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference ( id, Konferensi Asia–Afrika)—also known as the Bandung Conference—was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on 18–2 ...

). Between 1955 and 1957 he visited, as part of a diplomatic advertisement campaign in the Arab world, various Arabic states, among them repeatedly Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Medite ...

. One of his last deals, which he closed as minister, was a trade agreement with Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbe ...

, signed by Cuba's minister Ernesto 'Che' Guevara, on 17 December 1960 in East Berlin

East Berlin was the ''de facto'' capital city of East Germany from 1949 to 1990. Formally, it was the Soviet sector of Berlin, established in 1945. The American, British, and French sectors were known as West Berlin. From 13 August 1961 ...

.

Rau, in poor health during his final years, died of a heart attack in East Berlin, in March 1961.

Aftermath and legacy

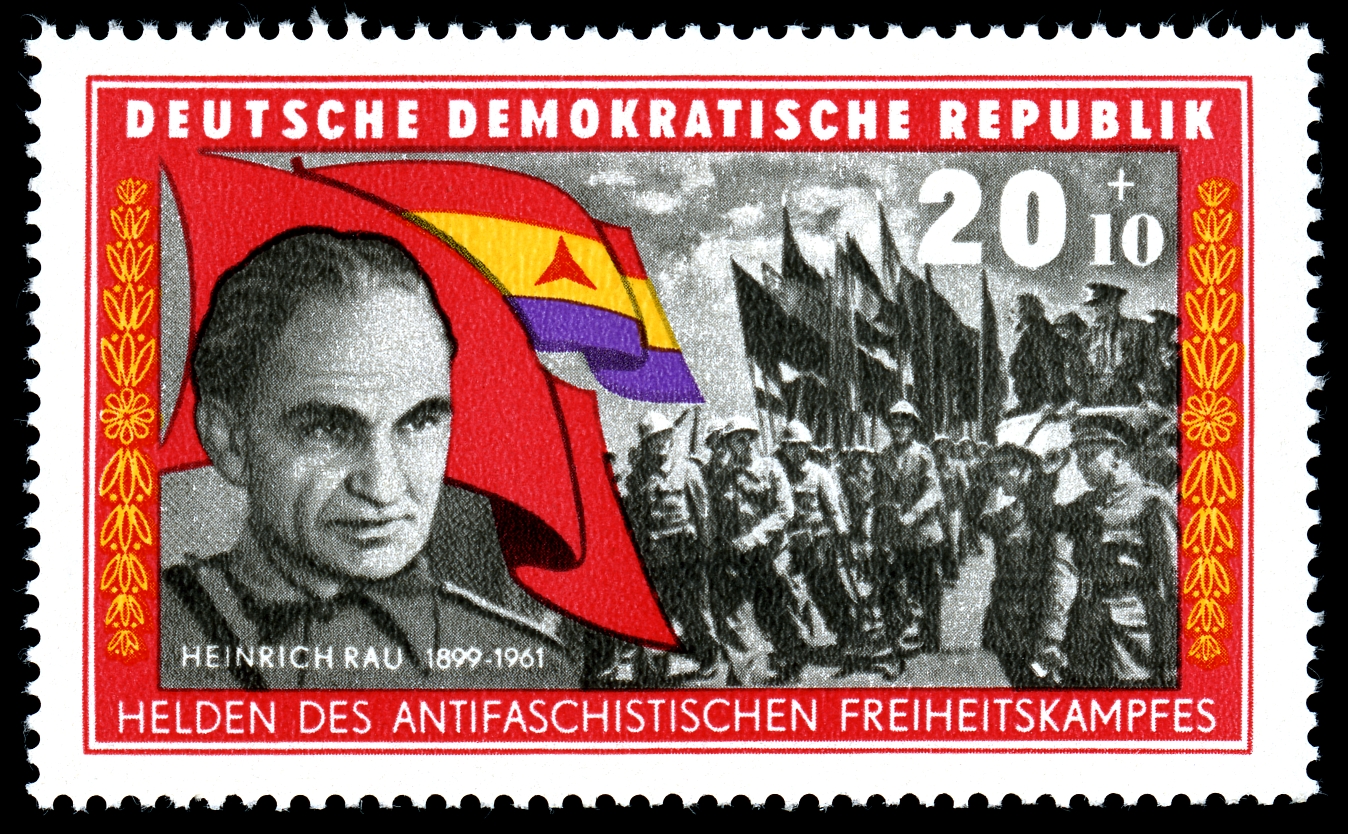

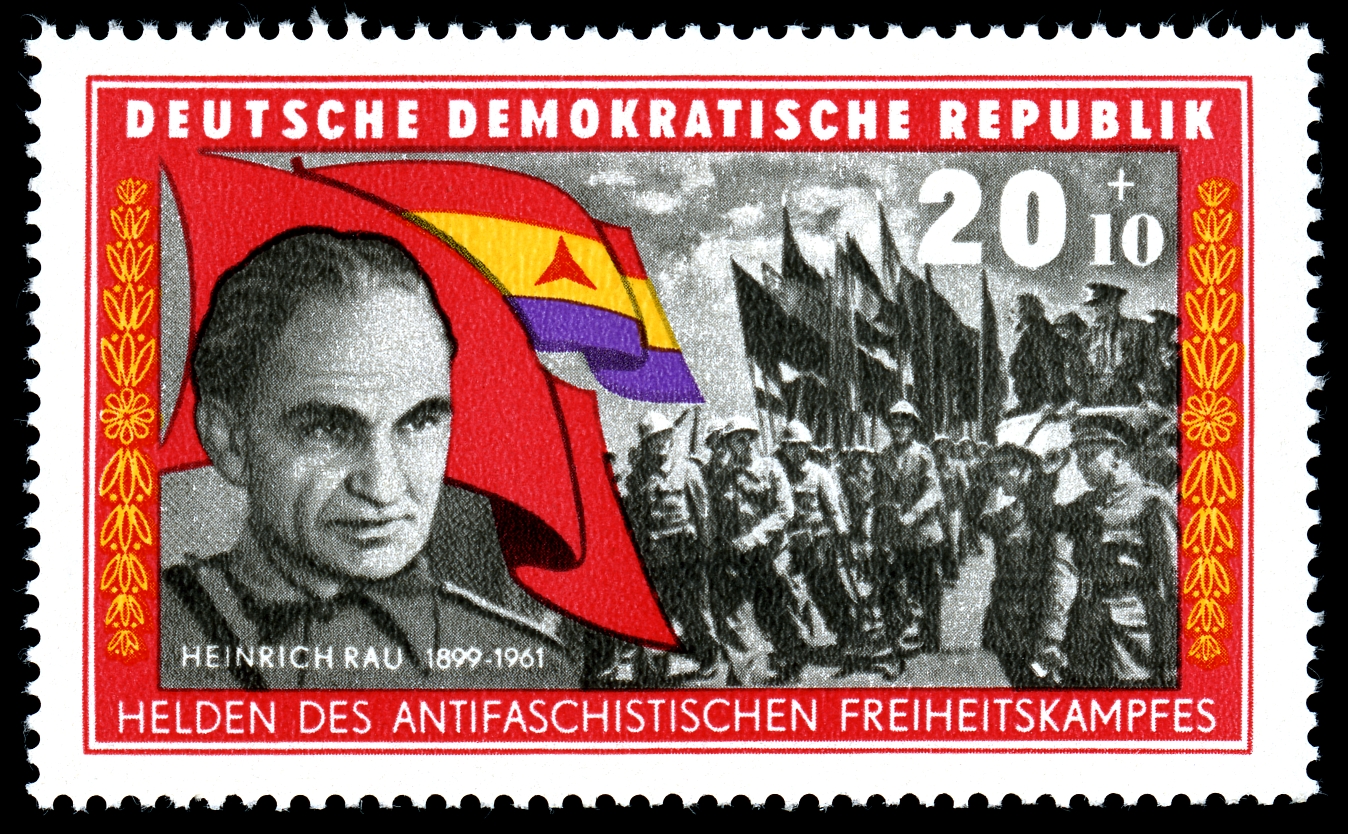

After his death, firms, schools, recreation homes, numerous streets, and a fighter squadron were named after him. The GDR issued a stamp with his picture three times. Rau was married twice and had three sons and a daughter. Like the other members of the Politburo, he lived until 1960 in a secured area of East Berlin's districtPankow

Pankow () is the most populous and the second-largest borough by area of Berlin. In Berlin's 2001 administrative reform, it was merged with the former boroughs of Prenzlauer Berg and Weißensee; the resulting borough retained the name Pankow. ...

and moved in 1960 to the Waldsiedlung near Wandlitz

Wandlitz is a municipality in the district of Barnim, in Brandenburg, Germany. It is situated 25 km north of Berlin, and 15 km east of Oranienburg. The municipality was established in 2004 by merger of the nine villages '' Basdorf'', ...

. In Pankow he had lived in Majakowskiring no. 50. In 1963, Rau's widow Elisabeth moved to this street again.

When the prominent West German SPD politician and future President of Germany

The president of Germany, officially the Federal President of the Federal Republic of Germany (german: link=no, Bundespräsident der Bundesrepublik Deutschland),The official title within Germany is ', with ' being added in international corres ...

Johannes Rau

Johannes Rau (; 16 January 193127 January 2006) was a German politician ( SPD). He was the president of Germany from 1 July 1999 until 30 June 2004 and the minister president of North Rhine-Westphalia from 20 September 1978 to 9 June 1998. In t ...

visited an SPD rally in the East German city of Erfurt

Erfurt () is the capital and largest city in the Central German state of Thuringia. It is located in the wide valley of the Gera river (progression: ), in the southern part of the Thuringian Basin, north of the Thuringian Forest. It sits in ...

during the time of German reunification, he was introduced as "Prime Minister 'Heinrich Rau. Thereupon Johannes Rau ironically commented on this lapse by observing that Heinrich Rau was a "Minister of Trade, a Swabian and a communist" and he was none of the three.

See also

*International Brigades order of battle

The International Brigades (IB) were volunteer military units of foreigners who fought on the side of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The number of combatant volunteers has been estimated at between 32,000–35,000, thoug ...

* East German mark

*Hallstein Doctrine

The Hallstein Doctrine (), named after Walter Hallstein, was a key principle in the foreign policy of the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) from 1955 to 1970. As usually presented, it prescribed that the Federal Republic would not esta ...

*History of East Germany

The German Democratic Republic (GDR), german: Deutsche Demokratische Republik (''DDR''), often known in English as East Germany, existed from 1949 to 1990. It covered the area of the present-day German states of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenbu ...

* Medal for Fighters Against Fascism

Notes and references

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * (Shows an American view in 1953) *External links

;Pictures * – Picture with Rau, Richard Staimer and Kurt Frank in Spain, 1937. * – The children's home "Ernst Thälmann" near Madrid was established in 1937 by the XI International Brigade as a home for war orphans. * – Picture with Rau and Guevara in East Berlin. * – Picture of Rau's wife Elisabeth with Patrice Lumumba's children in Egypt. ( Lumumba was the first Prime Minister of the Congo. His family moved into exile in Egypt after or shortly before his violent death. ) ;Others * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Rau, Heinrich 1899 births 1961 deaths Politicians from Stuttgart People from the Kingdom of Württemberg Independent Social Democratic Party politicians Communist Party of Germany politicians Members of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany Government ministers of East Germany Members of the Provisional Volkskammer Members of the 1st Volkskammer Members of the 2nd Volkskammer Members of the 3rd Volkskammer Members of the Landtag of Brandenburg German atheists German Army personnel of World War I Refugees from Nazi Germany in the Soviet Union German people of the Spanish Civil War International Brigades personnel Communists in the German Resistance Mauthausen concentration camp survivors Recipients of the Patriotic Order of Merit in gold Recipients of the Banner of Labor