Haywood S. Hansell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

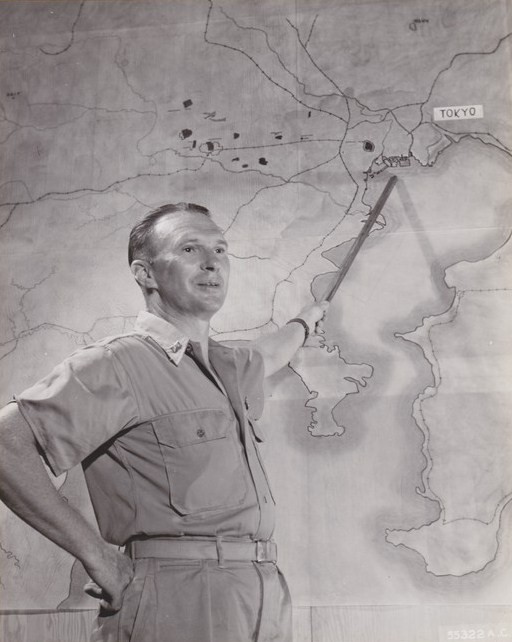

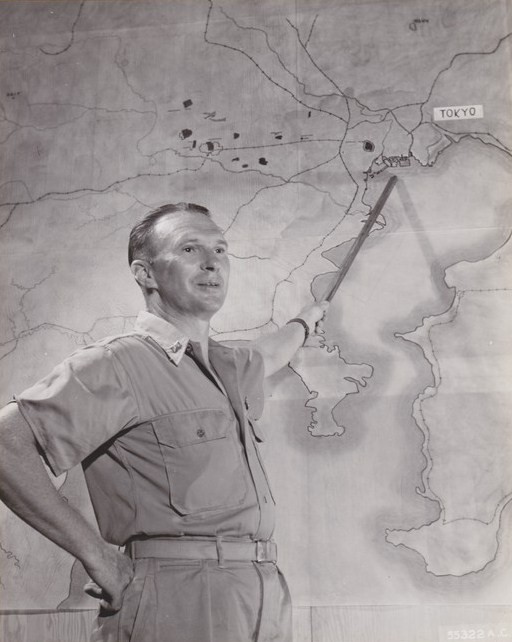

Haywood Shepherd Hansell Jr. (September 28, 1903 – November 14, 1988) was a general officer in the

On February 23, 1928, Hansell was appointed a flying cadet. He completed primary and basic flying schools at

On February 23, 1928, Hansell was appointed a flying cadet. He completed primary and basic flying schools at

Kenneth Wolfe

Orvil A. Anderson,

Hansell commanded the 1st Wing during six critical months when the B-17 force, with only four inexperienced groups, struggled to prove itself. Among the combat doctrines that Hansell developed himself or approved were use of the defensive combat box formation, detailed mission Standard Operating Procedures, and all aircraft bombing in unison with the lead bomber, each designed to improve bombing accuracy.

Hansell recognized the most serious flaws in the daylight precision bombardment theory, that:

*

Hansell commanded the 1st Wing during six critical months when the B-17 force, with only four inexperienced groups, struggled to prove itself. Among the combat doctrines that Hansell developed himself or approved were use of the defensive combat box formation, detailed mission Standard Operating Procedures, and all aircraft bombing in unison with the lead bomber, each designed to improve bombing accuracy.

Hansell recognized the most serious flaws in the daylight precision bombardment theory, that:

*

In October 1943, General Hansell was appointed chief of the Combined and Joint Staff Division, in the Office of the Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Plans, located at Headquarters USAAF. As such he became Air Planner on the Joint Planning Staff. He immediately affected planning of strategic air attacks on Japan. The JPS draft outline denigrated strategic bombing and declared that an invasion of the home islands was the only means of defeating Japan, but Hansell successfully argued that an invasion should only be a contingency if bombing and a sea blockade of Japan failed to compel a surrender.

Hansell accompanied President Roosevelt and the Joint Chiefs aboard the to the Sextant Conference in November, then was appointed Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in December, working directly with Arnold. His main responsibility was developing the operational plans for the

In October 1943, General Hansell was appointed chief of the Combined and Joint Staff Division, in the Office of the Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Plans, located at Headquarters USAAF. As such he became Air Planner on the Joint Planning Staff. He immediately affected planning of strategic air attacks on Japan. The JPS draft outline denigrated strategic bombing and declared that an invasion of the home islands was the only means of defeating Japan, but Hansell successfully argued that an invasion should only be a contingency if bombing and a sea blockade of Japan failed to compel a surrender.

Hansell accompanied President Roosevelt and the Joint Chiefs aboard the to the Sextant Conference in November, then was appointed Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in December, working directly with Arnold. His main responsibility was developing the operational plans for the

On August 28, 1944, Arnold made Hansell commander of the

On August 28, 1944, Arnold made Hansell commander of the  High altitude daylight B-29 raids against the Japanese aircraft industry began November 24, 1944 with operation '' San Antonio I'', despite misgivings about high losses by both combat crews and Arnold.Only one B-29 was lost on the mission, rammed in the tail by a damaged interceptor. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 5, p. 559). They were hampered by bad weather and jet stream winds, and as a result, appeared unproductive. Pressured by Arnold (through Norstad as an intermediary) for results, Hansell subjected his command to intensive corrective measures that caused more resentment among his aircrews. At the same time commanders in China were strongly recommending removal of

High altitude daylight B-29 raids against the Japanese aircraft industry began November 24, 1944 with operation '' San Antonio I'', despite misgivings about high losses by both combat crews and Arnold.Only one B-29 was lost on the mission, rammed in the tail by a damaged interceptor. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 5, p. 559). They were hampered by bad weather and jet stream winds, and as a result, appeared unproductive. Pressured by Arnold (through Norstad as an intermediary) for results, Hansell subjected his command to intensive corrective measures that caused more resentment among his aircrews. At the same time commanders in China were strongly recommending removal of

Air Force Combat Units of World War II

'. Office of Air Force History. * * * * * * * ;USAF Historical Studies *No. 89: *No. 91: *No. 100:

Air Force Link biography: Major General Haywood Hansell, Jr.

SOURCE: USAF Historical Study 91, ''Biographical Data on Air Force General Officers 1917–1952'' (1953) Air Force Historical Research Agency *

Distinguished Service Medal (June 30, 1943)

*

Distinguished Service Medal (June 30, 1943)

* Silver Star (January 15, 1943)

*

Silver Star (January 15, 1943)

* Legion of Merit (June 30, 1943)

*

Legion of Merit (June 30, 1943)

* Distinguished Flying Cross (September 16, 1943)

*

Distinguished Flying Cross (September 16, 1943)

*

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

*

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

* European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

*

European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

*

Combat Observer

* Technical Observer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hansell, Haywood S.

1903 births

1988 deaths

Air Corps Tactical School alumni

Georgia Tech alumni

People from Hampton, Virginia

Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

Recipients of the Legion of Merit

Recipients of the Silver Star

United States Air Force generals

United States Army Air Forces generals

United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II

United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

Burials in Colorado

Recipients of the Air Medal

United States Army Air Forces generals of World War II

Combat Observer

* Technical Observer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hansell, Haywood S.

1903 births

1988 deaths

Air Corps Tactical School alumni

Georgia Tech alumni

People from Hampton, Virginia

Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (US Army)

Recipients of the Legion of Merit

Recipients of the Silver Star

United States Air Force generals

United States Army Air Forces generals

United States Army Air Forces pilots of World War II

United States Army Command and General Staff College alumni

Burials in Colorado

Recipients of the Air Medal

United States Army Air Forces generals of World War II

United States Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

(USAAF) during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, and later the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

. He became an advocate of the doctrine of strategic bombardment

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

, and was one of the chief architects of the concept of daylight precision bombing that governed the use of airpower by the USAAF in the war.

Hansell played a key and largely unsung role in the strategic planning of air operations by the United States. This included drafting both the strategic air war plans (AWPD-1 and AWPD-42) and the plan for the Combined Bomber Offensive

The Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) was an Allied offensive of strategic bombing during World War II in Europe. The primary portion of the CBO was directed against Luftwaffe targets which was the highest priority from June 1943 to 1 April 1944. ...

in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located entirel ...

; obtaining a base of operations for the B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 F ...

in the Mariana Islands; and devising the command structure of the Twentieth Air Force

The Twentieth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) (20th AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Francis E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyoming.

20 AF's primary mission is Interco ...

, the first global strategic air force and forerunner of the Strategic Air Command. He made precision air attack, as both the most humane and effective means of achieving military success, a lifelong personal crusade that eventually became the key tenet of American airpower employment. Unfortunately, his air bombardment campaign over Japan proved to be a failure due to various elements, such as the interference of a powerful and consistent jet stream in that nation's airspace. He was replaced by General Curtis LeMay

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was an American Air Force general who implemented a controversial strategic bombing campaign in the Pacific theater of World War II. He later served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air ...

, who reoriented his air forces' tactics in reverse of Hansell's methods for an extremely destructive nighttime area

Area is the quantity that expresses the extent of a region on the plane or on a curved surface. The area of a plane region or ''plane area'' refers to the area of a shape or planar lamina, while '' surface area'' refers to the area of an ope ...

fire bombing

Firebombing is a bombing technique designed to damage a target, generally an urban area, through the use of fire, caused by incendiary devices, rather than from the blast effect of large bombs.

In popular usage, any act in which an incendiary d ...

campaign over Japan.

Hansell also held combat commands during the war, carrying out the very plans and doctrines he helped draft. He pioneered strategic bombardment of both Germany and Japan, as commander of the first B-17 Flying Fortress combat wing in Europe, and as the first commander of the B-29 force in the Marianas.

Childhood

Hansell was born inFort Monroe, Virginia

Fort Monroe, managed by partnership between the Fort Monroe Authority for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the National Park Service as the Fort Monroe National Monument, and the City of Hampton, is a former military installation in Hampton, Virgi ...

, on September 28, 1903, the son of First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

(later Colonel) Haywood S. Hansell, an Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

surgeon, and Susan Watts Hansell, both considered members of the "southern aristocracy" from Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

. His great-great-great-grandfather John W. Hansell served in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

, his great-great-grandfather William Young Hansell was an officer in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States, United States of America and its Indigenous peoples of the Americas, indigenous allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom ...

, and his great-grandfather Andrew Jackson Hansell was a general in the Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

and Georgia's adjutant general

An adjutant general is a military chief administrative officer.

France

In Revolutionary France, the was a senior staff officer, effectively an assistant to a general officer. It was a special position for lieutenant-colonels and colonels in staf ...

.Griffith, ''The Quest'', p.24. His grandfather, William Andrew Hansell, graduated from Georgia Military Institute

The Georgia Military Institute (GMI) was established on in Marietta, Georgia, United States, on July 1, 1851. It was burned by the Union Army during the Civil War and was never rebuilt.

The current GMI is a reactivation of the name for a Georgia ...

and also served as an officer in the Confederate Army, first in the 35th Alabama, then as a topographical

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the land forms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sc ...

engineer

Engineers, as practitioners of engineering, are professionals who invent, design, analyze, build and test machines, complex systems, structures, gadgets and materials to fulfill functional objectives and requirements while considering the limit ...

.According to Banning, p. 98, William Andrew Hansell was enrolled at LaGrange Military Academy when the 35th Alabama was formed from its faculty and cadets, and served as its adjutant and a lieutenant in Company B. He resigned in 1862 to become a captain of CSA Engineers.

Shortly after his birth, the family was stationed in Beijing

}

Beijing ( ; ; ), alternatively romanized as Peking ( ), is the capital of the People's Republic of China. It is the center of power and development of the country. Beijing is the world's most populous national capital city, with over 21 ...

, China, then in the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and Hansell learned both Chinese

Chinese can refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people of Chinese nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**''Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic concept of the Chinese nation

** List of ethnic groups in China, people of ...

and Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Can ...

at an early age.Benton, ''They Served Here'', p.31.Griffith, ''The Quest'', p.26. Captain Hansell was next stationed at Fort McPherson, Georgia, in 1913, and then at Fort Benning. His father, a firm disciplinarian, sent Hansell to live on a small, family-owned ranch in New Mexico

)

, population_demonym = New Mexican ( es, Neomexicano, Neomejicano, Nuevo Mexicano)

, seat = Santa Fe

, LargestCity = Albuquerque

, LargestMetro = Tiguex

, OfficialLang = None

, Languages = English, Spanish ( New Mexican), Navajo, Ke ...

because of a perceived lack of discipline in his schooling. There he learned horsemanship, shooting

Shooting is the act or process of discharging a projectile from a ranged weapon (such as a gun, bow, crossbow, slingshot, or blowpipe). Even the acts of launching flame, artillery, darts, harpoons, grenades, rockets, and guided missiles ...

, and studied with a tutor.

Education

Hansell entered Sewanee Military Academy, nearChattanooga, Tennessee

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020 ...

, in 1916, where he acquired the lifelong nickname " Possum." Although his biographers offer a number of explanations behind the nickname, the most likely is that his facial features gave him the appearance of a possum. At Sewanee he developed a fondness for English literature. As a senior Hansell rose to cadet captain and developed a reputation as a martinet

The martinet ( OED ''s.v.'' ''martinet'', ''n.''2, "'' N.E.D.'' (1905) gives the pronunciation as (mā·ɹtinėt) /ˈmɑːtɪnɪt/ .") is a punitive device traditionally used in France and other parts of Europe. The word also has other usages, de ...

. His harshness with the Corps of Cadets, combined with an excessive number of demerits acquired while the school was temporarily quartered in Jacksonville, Florida

Jacksonville is a city located on the Atlantic coast of northeast Florida, the most populous city proper in the state and is the List of United States cities by area, largest city by area in the contiguous United States as of 2020. It is the co ...

, following a fire, led to his reduction to cadet private.

Partly as a result of this humiliation, Hansell declined an appointment to the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

to attend the Georgia School of Technology

The Georgia Institute of Technology, commonly referred to as Georgia Tech or, in the state of Georgia, as Tech or The Institute, is a public research university and institute of technology in Atlanta, Georgia. Established in 1885, it is part of ...

, where he was a member of Sigma Nu. Despite problems understanding differential equation

In mathematics, a differential equation is an equation that relates one or more unknown functions and their derivatives. In applications, the functions generally represent physical quantities, the derivatives represent their rates of change, an ...

s, and twice attempting to transfer to another school (which his father would not permit), he overcame his difficulties with complex mathematics and graduated in 1924 with a Bachelor of Science

A Bachelor of Science (BS, BSc, SB, or ScB; from the Latin ') is a bachelor's degree awarded for programs that generally last three to five years.

The first university to admit a student to the degree of Bachelor of Science was the University o ...

degree in mechanical engineering

Mechanical engineering is the study of physical machines that may involve force and movement. It is an engineering branch that combines engineering physics and mathematics principles with materials science, to design, analyze, manufacture, an ...

. While at Georgia Tech he participated in varsity football as a walk-on substitute, and boxing

Boxing (also known as "Western boxing" or "pugilism") is a combat sport in which two people, usually wearing protective gloves and other protective equipment such as hand wraps and mouthguards, throw punches at each other for a predetermine ...

. Hansell was awarded Georgia Tech's highest individual recognition, membership in the ANAK Society.

From 1924 to 1928 he attempted without success to find employment as a civil engineer in California

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

, where his father was now stationed. Instead he worked as an apprentice

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

and journeyman

A journeyman, journeywoman, or journeyperson is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that fie ...

boilermaker

A boilermaker is a tradesperson who fabricates steel, iron, or copper into boilers and other large containers intended to hold hot gas or liquid, as well as maintains and repairs boilers and boiler systems.Bureau of Labor Statistics, US De ...

with the Steel Tank and Pipe Company in Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and E ...

. Advances in aviation

Aviation includes the activities surrounding mechanical flight and the aircraft industry. ''Aircraft'' includes fixed-wing and rotary-wing types, morphable wings, wing-less lifting bodies, as well as lighter-than-air craft such as hot a ...

in the 1920s led Hansell to undertake a career in aeronautical engineering

Aerospace engineering is the primary field of engineering concerned with the development of aircraft and spacecraft. It has two major and overlapping branches: aeronautical engineering and astronautical engineering. Avionics engineering is sim ...

, and to gain flying experience, he decided to join the United States Army Air Corps

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical r ...

.

Personality and family

Short in stature and slightly built, Hansell worked at being an athlete, becoming proficient intennis

Tennis is a racket sport that is played either individually against a single opponent ( singles) or between two teams of two players each ( doubles). Each player uses a tennis racket that is strung with cord to strike a hollow rubber ball ...

, polo, and squash

Squash may refer to:

Sports

* Squash (sport), the high-speed racquet sport also known as squash racquets

* Squash (professional wrestling), an extremely one-sided match in professional wrestling

* Squash tennis, a game similar to squash but pla ...

. Socially, he was a noted dancer, and acquired a reputation as "the unofficial poet laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch ...

of the Air Corps."Benton, ''They Served Here'', p.32. He was fond of Gilbert and Sullivan, Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, and Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was an Early Modern Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best kno ...

' ''Don Quixote

is a Spanish epic novel by Miguel de Cervantes. Originally published in two parts, in 1605 and 1615, its full title is ''The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha'' or, in Spanish, (changing in Part 2 to ). A founding work of West ...

''. General Ira C. Eaker described him as "nervous and high strung," and one biographer noted several incidents of imperious temper in social situations.Griffith, ''The Quest'', p.34. However his correspondence secretary during World War II, T/Sgt. James Cooper, described him as "pleasant and diplomatic," and an aviation historian described him as "a forward-looking optimist with a sense of humor."

While stationed at Langley Field Langley may refer to:

People

* Langley (surname), a common English surname, including a list of notable people with the name

* Dawn Langley Simmons (1922–2000), English author and biographer

* Elizabeth Langley (born 1933), Canadian perfo ...

, Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, Hansell met his wife, Dorothy "Dotta" Rogers, a teacher

A teacher, also called a schoolteacher or formally an educator, is a person who helps students to acquire knowledge, competence, or virtue, via the practice of teaching.

''Informally'' the role of teacher may be taken on by anyone (e.g. whe ...

from Waco, Texas

Waco ( ) is the county seat of McLennan County, Texas, United States. It is situated along the Brazos River and I-35, halfway between Dallas and Austin. The city had a 2020 population of 138,486, making it the 22nd-most populous city in the st ...

, where they were married in 1932. He fathered three children, son "Tony" (Haywood S. Hansell III, born in 1933), daughter Lucia (1940), and son Dennett (1941). While frequent absences, long working hours, and Hansell's autocratic nature severely stressed their marriage during World War II, they remained married for 56 years until his death in 1988. Hansell's eldest son continued the family military tradition, graduating from the United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

in 1955, becoming a colonel in the United States Air Force,Col. Tony Hansell was a KC-97

The Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter is a four-engined, piston-powered United States strategic tanker aircraft based on the Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter. It replaced the KB-29 and was succeeded by the Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker.

Design and developme ...

and KC-135

The Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker is an American military aerial refueling aircraft that was developed from the Boeing 367-80 prototype, alongside the Boeing 707 airliner. It is the predominant variant of the C-135 Stratolifter family of transpo ...

pilot, a Forward Air Controller

Forward air control is the provision of guidance to close air support (CAS) aircraft intended to ensure that their attack hits the intended target and does not injure friendly troops. This task is carried out by a forward air controller (FAC).

...

in Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

, and F-4 Phantom

The McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II is an American tandem two-seat, twin-engine, all-weather, long-range supersonic jet interceptor and fighter-bomber originally developed by McDonnell Aircraft for the United States Navy.Swanborough and Bo ...

pilot with the 80th TFS in Japan. He followed in his father's footsteps by instructing at the Air Command and Staff College

The Air Command and Staff College (ACSC) is located at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama and is the United States Air Force's intermediate-level Professional Military Education (PME) school. It is a subordinate command of the Air Univ ...

, and then holding staff positions in Strategy and Doctrine, with a tour as Assistant Deputy Chief of Staff-Plans, Headquarters USAF. Col. Hansell retired in 1985 and died in 2004. General Hansell's granddaughter, Lt. Col. Jennifer T. (Hansell) Perry, a USAF Security Forces

The United States Air Force Security Forces (SF) are the ground combat force and military police service of the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Space Force. USAF Security Forces (SF) were formerly known as Military Police (MP), Air Police (AP), and Sec ...

officer, is the seventh generation to serve in the military, fourth generation career officer, and third generation Air Force. Per West-Point.org and obituary, ''San Antonio Express-News'', December 6, 2004. and marrying Olivia Twining, the daughter of General Nathan F. Twining.

Early Air Corps career

Pursuit pilot

March Field

March is the third month of the year in both the Julian and Gregorian calendars. It is the second of seven months to have a length of 31 days. In the Northern Hemisphere, the meteorological beginning of spring occurs on the first day of Ma ...

, California, then advanced flight training in pursuit flying at Kelly Field, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

. He graduated from pilot training on February 28, 1929, and was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Army Reserve

A military reserve force is a military organization whose members have military and civilian occupations. They are not normally kept under arms, and their main role is to be available when their military requires additional manpower. Reserve ...

. He received a regular commission as a second lieutenant, Air Corps, on May 2, 1929.

Hansell's first duty assignment was with the 2nd Bombardment Group at Langley Field, testing repaired aircraft. In June 1930, he spent three months temporary duty with the 6th Field Artillery at Fort Hoyle, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. In September 1930, he returned to Langley Field and was detached to the Air Corps Tactical School

The Air Corps Tactical School, also known as ACTS and "the Tactical School", was a military professional development school for officers of the United States Army Air Service and United States Army Air Corps, the first such school in the world. C ...

as armament officer. While stationed at Langley, Hansell was involved in two minor accidents in aircraft he was piloting, and in early 1931 was forced to parachute to safety when his Boeing P-12

The Boeing P-12/F4B was an American pursuit aircraft that was operated by the United States Army Air Corps , United States Marine Corps, and United States Navy.

Design and development

Developed as a private venture to replace the Boeing F2B a ...

stalled during a test flight, going into an unrecoverable spin. He was found at fault for the accident and initially charged $10,000 by the Air Corps for the expense of the aircraft, but the cost was eventually written off.Griffith, ''The Quest'', p.32.

In August 1931, Hansell was transferred to Maxwell Field

Maxwell Air Force Base , officially known as Maxwell-Gunter Air Force Base, is a United States Air Force (USAF) installation under the Air Education and Training Command (AETC). The installation is located in Montgomery, Alabama, United States. O ...

, Alabama

(We dare defend our rights)

, anthem = "Alabama"

, image_map = Alabama in United States.svg

, seat = Montgomery

, LargestCity = Huntsville

, LargestCounty = Baldwin County

, LargestMetro = Greater Birmingham

, area_total_km2 = 135,765 ...

, as assistant operations officer, with flying duties in the 54th School Squadron, to support the ACTS, which had located to Maxwell from Langley in July. During that tour of duty he met Captain Claire L. Chennault

Claire Lee Chennault (September 6, 1893 – July 27, 1958) was an American military aviator best known for his leadership of the "Flying Tigers" and the Chinese Air Force in World War II.

Chennault was a fierce advocate of "pursuit" or fighte ...

, an instructor at the Tactical School, and joined "The Men on the Flying Trapeze,"Sometimes incorrectly seen as "Three Men on a Flying Trapeze". an Air Corps aerobatic and demonstration team.The team in 1932 consisted of Chennault, Hansell, Sgt. William C. "Billy" McDonald, and Sgt. John H. "Luke" Williamson. The two sergeants were reserve officers and later became Flying Tigers

The First American Volunteer Group (AVG) of the Republic of China Air Force, nicknamed the Flying Tigers, was formed to help oppose the Japanese invasion of China. Operating in 1941–1942, it was composed of pilots from the United States ...

. The team performed at the National Air Races at Cleveland, Ohio, in September 1934. Hansell also worked with Captain Harold L. George

Harold Lee George (July 19, 1893 – February 24, 1986) was an American aviation pioneer who helped shape and promote the concept of daylight precision bombing. An outspoken proponent of the industrial web theory, George taught at the Air Corps T ...

, chief of the Tactical School's bombardment section, where his military interest shifted from pursuits to bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft designed to attack ground and naval targets by dropping air-to-ground weaponry (such as bombs), launching torpedoes, or deploying air-launched cruise missiles. The first use of bombs dropped from an air ...

s.Harold Lee George's reputation as a bombardment proponent was such that he was known in the service as "Bomber George" to distinguish him from Harold Huston George

Harold Huston George (14 September 1892 – 29 April 1942) was a general officer in the United States Army Air Forces during World War II. He began his military career before World War I when he enlisted as a private in the 3rd New York Infantry ...

, a peer of nearly identical age and service experience, whose status as an ace during World War I and career in fighter units resulted in his moniker of "Pursuit George." The friendship that developed from the working relationship led to George becoming both Hansell's mentor and patron.

Disciple of strategic airpower

Hansell was promoted tofirst lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a ...

on October 1, 1934, and entered the Air Corps Tactical School

The Air Corps Tactical School, also known as ACTS and "the Tactical School", was a military professional development school for officers of the United States Army Air Service and United States Army Air Corps, the first such school in the world. C ...

at Maxwell Field as a student in the comprehensive 845-hour, 36-week course,Finney, ''History of the Air Corps Tactical School'', p.8. studying not only air tactics

Tactic(s) or Tactical may refer to:

* Tactic (method), a conceptual action implemented as one or more specific tasks

** Military tactics, the disposition and maneuver of units on a particular sea or battlefield

** Chess tactics

** Political tact ...

and airpower theory, which comprised more than half of the curriculum

In education, a curriculum (; : curricula or curriculums) is broadly defined as the totality of student experiences that occur in the educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view ...

, but also tactics of other services, combined (joint) warfare, armament and gunnery, logistics

Logistics is generally the detailed organization and implementation of a complex operation. In a general business sense, logistics manages the flow of goods between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet the requirements of ...

, navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, ...

and meteorology

Meteorology is a branch of the atmospheric sciences (which include atmospheric chemistry and physics) with a major focus on weather forecasting. The study of meteorology dates back millennia, though significant progress in meteorology did no ...

, staff duties, photography

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating durable images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is employe ...

, combat orders, and antiaircraft defenses. Among his instructors was Captain George, now director of the Department of Air Tactics and Strategy. George's classes were half lecture, half free discussion and conceptualizing, with George or his assistant Capt. Odas Moon expounding theories and having the students critically examine them for flaws and alternative ideas, debates that continued beyond the classroom as well.

Making up the 59 members of his class were five majors, 40 captains, 13 first lieutenants including himself, and one second lieutenant. In addition to 49 Air Corps officers were four Army officers, one from each of that service's combat arms, two Turkish Army

The Turkish Land Forces ( tr, Türk Kara Kuvvetleri), or Turkish Army (Turkish: ), is the main branch of the Turkish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. The army was formed on November 8, 1920, after the collapse of the ...

aviators, one Mexican captain, and three Marine Corps

Marines, or naval infantry, are typically a military force trained to operate in littoral zones in support of naval operations. Historically, tasks undertaken by marines have included helping maintain discipline and order aboard the ship (refl ...

aviators, including two future major generals.The future USMC generals were Lawson Sanderson, who commanded Pappy Boyington

Gregory "Pappy" Boyington (December 4, 1912 – January 11, 1988) was an American combat pilot who was a United States Marine Corps fighter ace during World War II. He received the Medal of Honor and the Navy Cross. A Marine aviator with ...

's air group in World War II, and future Director of Marine Aviation William J. Wallace. Wallace commanded all combat support aviation on Okinawa, including USAAF squadrons. Among Hansell's Air Corps classmates were future generals Muir S. Fairchild, Barney Giles, Laurence S. Kuter, and Hoyt S. Vandenberg; test pilot Lester J. Maitland

Lester James Maitland (February 8, 1899 – March 27, 1990) was an aviation pioneer and career officer in the United States Army Air Forces and its predecessors. Maitland began his career as a Reserve pilot in the U.S. Army Air Service during Wo ...

; and aviation pioneer Major Vernon Burge, who as a corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use in some form by many militaries and by some police forces or other uniformed organizations. The word is derived from the medieval Italian phrase ("head of a body"). The rank is usually the lowest ranking non- ...

in June 1912 had been the first certified enlisted military pilot. Hansell graduated in June 1935 and was invited to become an instructor at ACTS, one of nine in his class to become ACTS instructors, and the youngest in its history. He served on the faculty from 1935 to 1938 in the Department of Air Tactic's all-important Air Force Section, first under George, then Major Donald Wilson (another strategic bombing advocate), and lastly Fairchild.Griffith, ''The Quest'', p.46.

Hansell became a member of a group known as the "Bomber Mafia

The Bomber Mafia were a close-knit group of American military men who believed that long-range heavy bomber aircraft in large numbers were able to win a war. The derogatory term "Bomber Mafia" was used before and after World War II by those in t ...

," ACTS instructors who were both outspoken proponents of the doctrine of daylight precision strategic bombardment and advocates for an independent Air Force. Among the students instructed by Hansell were Eaker, Twining, Elwood R. Quesada, Earle E. PartridgeKenneth Wolfe

Orvil A. Anderson,

John K. Cannon

General John Kenneth Cannon (March 9, 1892 – January 12, 1955) was a World War II Mediterranean combat commander and former chief of United States Air Forces in Europe for whom Cannon Air Force Base, Clovis, New Mexico, is named.

Biography

Joh ...

, and Newton Longfellow, all of whom became general officers and strategic airpower advocates during World War II. During this time, Hansell also had a permanent falling out with Chennault after Chennault tried to recruit him to go to China to fly fighters for the Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT), also referred to as the Guomindang (GMD), the Nationalist Party of China (NPC) or the Chinese Nationalist Party (CNP), is a major political party in the Republic of China, initially on the Chinese mainland and in Tai ...

government.

In September 1938, still a first lieutenant, Hansell entered the Command and General Staff School

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

at Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., and the oldest perma ...

, Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to th ...

, from which he was graduated in June 1939, shortly after promotion to captain. He then was assigned to the Office, Chief of Air Corps (OCAC), under General Henry H. Arnold

Henry Harley Arnold (June 25, 1886 – January 15, 1950) was an American general officer holding the ranks of General of the Army and later, General of the Air Force. Arnold was an aviation pioneer, Chief of the Air Corps (1938–1941), ...

, working a series of assignments as Arnold assembled an Air Staff to plan and execute a massive expansion of the Air Corps.

After duty in the Public Relations Section, OCAC from July 1 to September 5, 1939, he became assistant Executive Officer, OCAC to Ira Eaker from September 6 to November 20, 1939. In November 1939 he created, with Major Thomas D. White, the Intelligence Section, Information Division, OCAC. Hansell was its Officer in Charge, Air Corps Intelligence from November 21, 1939, to June 30, 1940; and its Chief, Operations Planning Branch, Foreign Intelligence Section from July 1, 1940, to June 30, 1941. He was promoted to major on March 15, 1941.Fogerty, Historical Study 91.

In the Air Intelligence Section, Hansell became responsible for setting up strategic air intelligence and analysis operations, creating three sections: analysis of foreign air forces and their doctrines, analysis of airfields worldwide including climate data, and preparation of target selection for major foreign powers. Much of the work was accomplished despite hindrance from the War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War (1789–1947)

See also

* War Office, a former department of the British Government

* Ministry of defence

* Ministry of War

* Ministry of Defence

* D ...

's G-2 office, which felt that such analysis was not "proper military intelligence." Development of sources of information for such analyses also was primitive, and he used his assignment to OPB to recruit a number of civilian economic experts who had recently been commissioned in the military. Hansell also created contacts among Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the United Kingdom's air and space force. It was formed towards the end of the First World War on 1 April 1918, becoming the first independent air force in the world, by regrouping the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) an ...

officers stationed in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

to enhance his sources.Griffith, ''The Quest'', p.63.

On July 7, 1941, Hansell went to London, England

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a major s ...

, as a special observer attached to the military attaché, where he was privy to the inner workings of RAF intelligence and their target folders on the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

industrial infrastructure. In his memoir, Hansell stated that in the exchange of information, the AAF received nearly a ton of material, shipped back to the United States in a bomber.

AWPD-1

On July 12, 1941, Hansell, just returned from London, was recruited by Harold George to join the Air War Plans Division of the newly created AAF Air Staff in Washington, D.C., as its Chief of European Branch. There a strategic planning team of former "bomber mafia" members (himself, George, Kuter, and War Plans Group chief Lt. Col. Kenneth N. Walker), put together an estimate for PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

of the numbers of aircraft and personnel needed to win a war against the Axis Powers, well beyond the scope requested of it by the War Plans Division of the General Staff.

Hansell's responsibility in the plan, designated AWPD–1, was information on German targets. Arnold had given George nine days to write the plan, which would be "Annex 2, Air Requirements" to "The Victory Program," a plan of strategic estimates involving the entire U.S. military.

Beginning on August 4, 1941, they drew up the plan in accordance with strategic policies promulgated earlier that year, outlined in the ABC-1 agreement with the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

, and Rainbow 5, the U.S. war plan. The group completed AWPD-1 in the allotted nine days and carefully rehearsed a presentation to the Army General Staff. Its forecast figures, despite planning errors from lack of accurate information about weather and the German economic commitment to the war, were within 2 percent of the units and 5.5 percent of the personnel ultimately mobilized, and it accurately predicted the time frame when the invasion of Europe by the Allies would take place.Griffith, ''The Quest'', p.77.

Hansell's contribution to the plan was based on a serious mistake, however. As had most observers, Hansell assumed that the Nazi economy

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with the ...

was working at maximum capacity, when in fact it was still at 1938 levels of production, an error that led to an underestimation of the numbers of sorties, bomb tonnage, and time required for bombing to have a decisive effect. However, a more significant error in planning, the omission of long-range fighter escorts for the bombers, seriously affected the strategic bombing campaign that later took place. Hansell deeply regretted the omission but noted that it reflected the best available information at the time on fighter aircraft capabilities, which was that any means then available to extend range would also seriously degrade a fighter's air combat performance. Hansell wrote, "Failure to see this issue through proved one of the Air Corps Tactical School's major shortcomings."

A lack of knowledge about the capability of radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

to create an effective centralized early warning system also contributed to the over-reliance on the self-defense capabilities of bombers. However Hansell also argued that ignorance of radar was fortuitous in the long run. He surmised that had radar been a factor in making doctrine, many theorists would have reasoned that massed defenses would make all strategic air attacks too costly, inhibiting if not entirely suppressing the concepts that proved decisive in World War II and essential to the creation of the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Aerial warfare, air military branch, service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part ...

.

World War II service

Planning duties

Following the entry of the United States into World War II, Hansell received a rapid series of promotions, to lieutenant colonel on January 5, 1942,colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge o ...

on March 1, 1942, and brigadier general

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

on August 10, 1942. In January 1942, he assisted George and Walker in presenting an organizational plan to the War Department for maintaining the Air Corps as part of the Army during World War II, while dividing the Army into three autonomous branches, a reorganization adopted on March 9, 1942, with the creation of the Army Air Forces, Army Ground Forces

The Army Ground Forces were one of the three autonomous components of the Army of the United States during World War II, the others being the Army Air Forces and Army Service Forces. Throughout their existence, Army Ground Forces were the large ...

and Services of Supply

The Services of Supply or "SOS" branch of the Army of the USA was created on 28 February 1942 by Executive Order Number 9082 "Reorganizing the Army and the War Department" and War Department Circular No. 59, dated 2 March 1942. Services of Supp ...

. On March 10, 1942, Hansell was transferred from AWPD to the Strategy and Policy Group, Operations Division of the War Department General Staff and served on the eight-member Joint Strategy Committee as the USAAF representative.

Hansell, at the request of Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

, was assigned on July 12, 1942, as Officer in Charge, Air Section, ETOUSA

The European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) was a Theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout the European theatre of World War II, from 1942 to 1945. It commanded Army Ground For ...

headquarters, and simultaneously as deputy theater air officer for Major General Carl A. Spaatz, commander of the Eighth Air Force. His duties were to mold Eisenhower's opinion on the use of airpower, guided by Spaatz, but there is little indication that he succeeded. He also flew combat in a B-17 to gain first-hand experience with daylight precision bombing, attacking the Longueau

Longueau (; pcd, Londjeu) is a commune in the Somme department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

Geography

Longueau is situated southeast of Amiens, a suburb just by the airport, on the N29 road. Longueau station has rail connections to ...

marshalling yard at Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

, on August 20, 1942. During the mission he developed frostbite

Frostbite is a skin injury that occurs when exposed to extreme low temperatures, causing the freezing of the skin or other tissues, commonly affecting the fingers, toes, nose, ears, cheeks and chin areas. Most often, frostbite occurs in the ha ...

on his hands and spent several days recovering from the effects.

On August 26, 1942, he was recalled to USAAF Headquarters to head the planning team for AWPD–42, a revision of the air strategy plan in light of ongoing crises in the war, completing it in 11 days. Even though the Navy rejected the plan outright (because it did not participate in its writing) and the Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

did not accept it, presidential advisor Harry Hopkins recommended to Roosevelt that he follow the precepts unofficially, which was done. Hansell then returned to England, where he was ironically tasked with diverting a large portion of the strategic bomber force to the Twelfth Air Force

The Twelfth Air Force (12 AF; Air Forces Southern, (AFSOUTH)) is a Numbered Air Force of the United States Air Force Air Combat Command (ACC). It is headquartered at Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, Arizona.

The command is the air component to ...

to support Operation Torch.

Combat wing commander in Europe

On December 5, 1942, Hansell received his first combat command, the 3rd Bombardment Wing. Originally one of the three wings ofGeneral Headquarters Air Force

The United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) was the aerial warfare service component of the United States Army between 1926 and 1941. After World War I, as early aviation became an increasingly important part of modern warfare, a philosophical ri ...

,Maurer, ''Combat Units'', p. 414.The 3rd Bombardment Wing was later redesignated the 98th Bomb Wing of the Ninth Air Force

The Ninth Air Force (Air Forces Central) is a Numbered Air Force of the United States Air Force headquartered at Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina. It is the Air Force Service Component of United States Central Command (USCENTCOM), a joint De ...

. the 3rd was now part of the Eighth Air Force in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, planned as a Martin B-26 Marauder

The Martin B-26 Marauder is an American twin-engined medium bomber that saw extensive service during World War II. The B-26 was built at two locations: Baltimore, Maryland, and Omaha, Nebraska, by the Glenn L. Martin Company.

First used in t ...

unit with the mission of supporting the Eighth's heavy bomber operations by bombing Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

fighter airfields. However the wing had no aircraft or units yet assigned, and on January 2, 1943, Hansell was shifted to command the 1st Bombardment Wing

The 1st Bombardment Wing is a disbanded United States Army Air Force unit. It was initially formed in France in 1918 during World War I as a command and control organization for the Pursuit Groups of the First Army Air Service.

Demobilized after ...

, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress component of VIII Bomber Command

8 (eight) is the natural number following 7 and preceding 9.

In mathematics

8 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being , , and . It is twice 4 or four times 2.

* a power of two, being 2 (two cubed), and is the first number of ...

.Hansell's predecessor was Laurence Kuter, who had been transferred to North Africa as part of "Torch". Hansell flew his first mission with his new command the next day to bomb the submarine pens at Saint-Nazaire, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan area ...

. He saw first hand the effectiveness of German interceptors, as both wingmen of Hansell's bomber were shot down. Later that month, on a January 13 mission to Lille, France

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France region, the prefecture of the Nord ...

, the pilot of the B-17 in which he flew was killed in action and the plane nearly shot down on.

Hansell commanded the 1st Wing during six critical months when the B-17 force, with only four inexperienced groups, struggled to prove itself. Among the combat doctrines that Hansell developed himself or approved were use of the defensive combat box formation, detailed mission Standard Operating Procedures, and all aircraft bombing in unison with the lead bomber, each designed to improve bombing accuracy.

Hansell recognized the most serious flaws in the daylight precision bombardment theory, that:

*

Hansell commanded the 1st Wing during six critical months when the B-17 force, with only four inexperienced groups, struggled to prove itself. Among the combat doctrines that Hansell developed himself or approved were use of the defensive combat box formation, detailed mission Standard Operating Procedures, and all aircraft bombing in unison with the lead bomber, each designed to improve bombing accuracy.

Hansell recognized the most serious flaws in the daylight precision bombardment theory, that:

* radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, we ...

early warning and the lack of long-range escort fighters made deep penetration raids by massed bombers too costly to achieve strategic goals until a means of air superiority was attained, and that

* German industry, rather than being fragile and fixed, proved to be resilient and mobile.

These factors later influenced his planning of similar daylight raids against Japan.

On March 23, 1943, he headed up a committee of USAAF and RAF commanders to draw up a plan for the Combined Bomber Offensive

The Combined Bomber Offensive (CBO) was an Allied offensive of strategic bombing during World War II in Europe. The primary portion of the CBO was directed against Luftwaffe targets which was the highest priority from June 1943 to 1 April 1944. ...

(CBO).Hansell,''The Air Plan That Defeated Hitler'', p. 157 Despite the fact that it altered the target system priorities outlined in AWPD-42, and changed the overall goal of the offensive from knocking Germany out of the war using airpower to one of preparing for the invasion of Europe, Hansell approved the designation of the German aircraft industry as its most important target and the destruction of the German ''Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

'' as its top priority. Hansell wrote the final draft of the CBO plan himself. Although Hansell did not personally participate in later strategic bombing operations against Germany, he had been instrumental in setting in motion the plans and policies that led to the near total destruction of German war industry.

He continued to fly combat missions at the same rate as his group commanders, with his final mission to Antwerp on May 4, 1943, the date that the Joint Chiefs approved the CBO plan. On June 15, 1943, noting signs of fatigue and stress, Eaker decided to replace Hansell in command of the 1st Wing with veteran commander Brigadier General Frank A. Armstrong Jr.,Armstrong did not command the wing long, injured in a fire in his quarters in July. but retained him as a staff officer, first as an air planner in the COSSAC (Chief of Staff Supreme Allied Commander) headquarters until August 1, 1943, when Eisenhower named him deputy commander of the Allied Expeditionary Air Force. He conjointly was part of the Tactical Air Force Planning Committee, where he oversaw the planning for Operation Tidal Wave

Operation Tidal Wave was an air attack by bombers of the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) based in Libya on nine oil refineries around Ploiești, Romania on 1 August 1943, during World War II. It was a strategic bombing mission and part of ...

, the low-level bombing of oil refineries

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, lique ...

at Ploieşti, Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, and ...

, on August 1, 1943, and recommended approval of the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission. While in Washington on this task, he was "captured" by Arnold and accompanied him to the Quadrant Conference in August, where he personally briefed President Roosevelt on strategic bombing to that point.

B-29 operations planning

In October 1943, General Hansell was appointed chief of the Combined and Joint Staff Division, in the Office of the Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Plans, located at Headquarters USAAF. As such he became Air Planner on the Joint Planning Staff. He immediately affected planning of strategic air attacks on Japan. The JPS draft outline denigrated strategic bombing and declared that an invasion of the home islands was the only means of defeating Japan, but Hansell successfully argued that an invasion should only be a contingency if bombing and a sea blockade of Japan failed to compel a surrender.

Hansell accompanied President Roosevelt and the Joint Chiefs aboard the to the Sextant Conference in November, then was appointed Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in December, working directly with Arnold. His main responsibility was developing the operational plans for the

In October 1943, General Hansell was appointed chief of the Combined and Joint Staff Division, in the Office of the Assistant Chief of Air Staff for Plans, located at Headquarters USAAF. As such he became Air Planner on the Joint Planning Staff. He immediately affected planning of strategic air attacks on Japan. The JPS draft outline denigrated strategic bombing and declared that an invasion of the home islands was the only means of defeating Japan, but Hansell successfully argued that an invasion should only be a contingency if bombing and a sea blockade of Japan failed to compel a surrender.

Hansell accompanied President Roosevelt and the Joint Chiefs aboard the to the Sextant Conference in November, then was appointed Deputy Chief of the Air Staff in December, working directly with Arnold. His main responsibility was developing the operational plans for the B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 F ...

, and he succeeded in gaining three key decisions from the JCS: there would be no diversion of B-29s to General Douglas MacArthur, the schedule for Operation Forager

The Mariana and Palau Islands campaign, also known as Operation Forager, was an offensive launched by United States forces against Imperial Japanese forces in the Mariana Islands and Palau in the Pacific Ocean between June and November 1944 du ...

was moved forward more than a year to secure bases for the B-29 in the Mariana Islands,The invasion, a pet project of CNO Admiral Ernest J. King, had tentatively been set for early 1946, if at all. and Twentieth Air Force

The Twentieth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) (20th AF) is a numbered air force of the United States Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Francis E. Warren Air Force Base, Wyoming.

20 AF's primary mission is Interco ...

operations would be entirely independent of control by all three Pacific theater commanders (MacArthur, Chester W. Nimitz, and Joseph Stilwell

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell (March 19, 1883 – October 12, 1946) was a United States Army general who served in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. An early American popular hero of the war for leading a column walking o ...

), reporting directly to the JCS.

Hansell drew up the tactical doctrine, SOPs, and the table of organization and equipment

A table of organization and equipment (TOE or TO&E) is the specified organization, staffing, and equipment of units. Also used in acronyms as 'T/O' and 'T/E'. It also provides information on the mission and capabilities of a unit as well as the u ...

of the Twentieth Air Force, which was to be commanded by Arnold personally, including use of AAF Air Staff as the staff of the Twentieth. In addition to his own Air Staff duties, Hansell became chief of staff of the Twentieth Air Force on April 6, 1944. When Arnold was incapacitated by a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

in May, Hansell acted as ''de facto'' commander of the Twentieth Air Force.

B-29 commander

On August 28, 1944, Arnold made Hansell commander of the

On August 28, 1944, Arnold made Hansell commander of the XXI Bomber Command

The XXI Bomber Command was a unit of the Twentieth Air Force in the Mariana Islands for strategic bombing during World War II.

The command was established at Smoky Hill Army Air Field, Kansas on 1 March 1944. After a period of organization an ...

, despite misgivings among several senior leaders that while a superb staff officer, he did not have the "temperament" to be a combat commander. Aware of Arnold's legendary impatience, deputy AAF commander General Barney Giles, who was doubtful that Hansell could accomplish the task given him—setting up an effective air campaign in a brief period using an untried aircraft—obtained a commitment from Arnold that he would not relieve Hansell in only a few months. However Hansell's tenure was threatened from the start because his replacement on the Air Staff, Major General Lauris Norstad

Lauris Norstad (March 24, 1907 – September 12, 1988) was an American General officer, general officer in the United States Army and United States Air Force.

Early life and military career

Lauris Norstad was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Minn ...

, did not support the concept of daylight precision bombing, instead advocating massive destruction of Japanese cities by firebombing

Firebombing is a bombing technique designed to damage a target, generally an urban area, through the use of fire, caused by incendiary devices, rather than from the blast effect of large bombs.

In popular usage, any act in which an incendiary d ...

, a tactic that had been promoted in AAF planning circles as early as November 1943. Fire raids on Japan were rapidly gaining widespread acceptance among AAF leaders, including Arnold, both to defeat Japan before an invasion was mounted and to satisfy a perception that the American public wanted revenge for three bloody years of war. Hansell, however, opposed the tactic as both morally repugnant and militarily unnecessary.

XXI Bomber Command arrived on Saipan on October 12, 1944, and from the start Hansell was beset by a host of serious command problems, the worst of which were continued teething problems with the B-29, tardy delivery of aircraft, aircrews untrained in high altitude formation flying, primitive airfield conditions, lack of an air service command for logistical support, no repair depots, a total absence of target intelligence, stubborn internal resistance to daylight operations by his sole combat wing,Strong resistance by the Japanese during the seizure of the Marianas and subsequent low construction priorities assigned by the Navy resulted in up to two months' delay in the deployment of two additional wings scheduled to begin operations in December 1944 and January 1945. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 5, pp. 515–522, 569) subordinates in the XXI Bomber Command who lobbied for his removal, and Hansell's inferiority in rank in dealing with other AAF commanders in the theater.Hansell's difficulties were exacerbated by petty jurisdictional resistance from the Army commander of the Pacific Ocean Area in Hawaii, General Robert C. Richardson, Jr., and by low priorities assigned to the buildup of Hansell's facilities in the Marianas by Nimitz's staff in favor of roads and naval installations, despite XXI BC being the only force on the islands conducting continuous combat operations. (Craven And Cate, Vol. 5, pp. 533–534, and 542). Furthermore, Hansell was soon prohibited from flying combat missions with his command, possibly because of limited knowledge of the atomic bomb or the perception that he knew the existence of Ultra

adopted by British military intelligence in June 1941 for wartime signals intelligence obtained by breaking high-level encrypted enemy radio and teleprinter communications at the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) at Bletchley Park. ' ...

.

High altitude daylight B-29 raids against the Japanese aircraft industry began November 24, 1944 with operation '' San Antonio I'', despite misgivings about high losses by both combat crews and Arnold.Only one B-29 was lost on the mission, rammed in the tail by a damaged interceptor. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 5, p. 559). They were hampered by bad weather and jet stream winds, and as a result, appeared unproductive. Pressured by Arnold (through Norstad as an intermediary) for results, Hansell subjected his command to intensive corrective measures that caused more resentment among his aircrews. At the same time commanders in China were strongly recommending removal of

High altitude daylight B-29 raids against the Japanese aircraft industry began November 24, 1944 with operation '' San Antonio I'', despite misgivings about high losses by both combat crews and Arnold.Only one B-29 was lost on the mission, rammed in the tail by a damaged interceptor. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 5, p. 559). They were hampered by bad weather and jet stream winds, and as a result, appeared unproductive. Pressured by Arnold (through Norstad as an intermediary) for results, Hansell subjected his command to intensive corrective measures that caused more resentment among his aircrews. At the same time commanders in China were strongly recommending removal of XX Bomber Command

The XX Bomber Command was a United States Army Air Forces bomber formation. Its last assignment was with Twentieth Air Force, based on Okinawa. It was inactivated on 16 July 1945.

History

The idea of basing Boeing B-29 Superfortresses in ...

to another theater as soon as possible, making Major General Curtis E. LeMay

Curtis Emerson LeMay (November 15, 1906 – October 1, 1990) was an American Air Force general who implemented a controversial strategic bombing campaign in the Pacific theater of World War II. He later served as Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air F ...

, now superior to Hansell in rank, available for command.

On January 6, 1945, Norstad visited Hansell's headquarters and abruptly relieved him of command, replacing him with LeMay.Norstad and Hansell had worked closely together before Hansell's assignment to XXI BC and were personal friends. (Craven and Cate, Vol. 5, p. 567) Hansell was offered the option of commanding XX Bomber Command while it transitioned to Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, then becoming LeMay's deputy. Although he and LeMay were friends, LeMay had been Hansell's subordinate in England, and Hansell declined the offer. While all the command problems factored into his relief, the main reasons were Hansell's persistence in daylight precision attacks, reluctance to night firebombing, Norstad's view that Hansell was an impediment to instituting incendiary attacks, and a perception by Arnold and Norstad that the public relations

Public relations (PR) is the practice of managing and disseminating information from an individual or an organization (such as a business, government agency, or a nonprofit organization) to the public in order to influence their perception. ...

effort by XXI Bomber Command had been unsatisfactory in preparing the American public for such attacks.

Hansell left Guam on January 21, 1945. Unknown at the time, his precision daylight attacks had succeeded, first in Japan's immediate and inefficient dispersion of its aircraft engine industry, and later in terms of actual destruction caused by the final raid under his command.Morrison, ''Point of No Return'', p.199. A more immediate legacy of his command was his creation, in conjunction with the U.S. Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage o ...

, of an effective air-sea rescue

Air-sea rescue (ASR or A/SR, also known as sea-air rescue), and aeronautical and maritime search and rescue (AMSAR) by the ICAO and IMO, is the coordinated search and rescue (SAR) of the survivors of emergency water landings as well as people ...

system that saved half of all B-29 crews downed at sea in 1945.

Impact on strategic doctrine