Havelock Ellis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician,

In November 1891, at the age of 32, and reportedly still a virgin, Ellis married the English writer and proponent of

In November 1891, at the age of 32, and reportedly still a virgin, Ellis married the English writer and proponent of

Ellis resigned from his position as a Fellow of the Eugenics Society over its stance on sterilization in January 1931.

Ellis spent the last year of his life at

Ellis resigned from his position as a Fellow of the Eugenics Society over its stance on sterilization in January 1931.

Ellis spent the last year of his life at

* '' The Criminal'' (1890)

* ''The New Spirit'' (1890)

* ''The Nationalisation of Health'' (1892)

* ''Man and Woman: A Study of Secondary and Tertiary Sexual Characteristics'' (1894) (revised 1929)

* translator: '' Germinal'' (by

* '' The Criminal'' (1890)

* ''The New Spirit'' (1890)

* ''The Nationalisation of Health'' (1892)

* ''Man and Woman: A Study of Secondary and Tertiary Sexual Characteristics'' (1894) (revised 1929)

* translator: '' Germinal'' (by

Havelock Ellis papers (MS 195). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

*

Henry Havelock Ellis papers from the Historic Psychiatry Collection, Menninger Archives, Kansas Historical Society

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ellis, Havelock 1859 births 1939 deaths 19th-century English non-fiction writers 20th-century English non-fiction writers Alumni of King's College London Alumni of St Thomas's Hospital Medical School British sexologists English eugenicists English psychologists People from Croydon British psychedelic drug advocates British relationships and sexuality writers Medical writers on LGBT topics British social reformers Transgender studies academics Victorian writers Translators of Émile Zola

eugenicist

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

, writer, progressive intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and reflection about the reality of society, and who proposes solutions for the normative problems of society. Coming from the world of culture, either as a creator or a ...

and social reformer

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

who studied human sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to peop ...

in 1897, and also published works on a variety of sexual practices and inclinations, as well as on transgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through tr ...

psychology. He is credited with introducing the notions of narcissism

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive interest in one's physical appearance or image and an excessive preoccupation with one's own needs, often at the expense of others.

Narcissism exists on a co ...

and autoeroticism

Autoeroticism or autosexuality is a practice of sexually stimulating oneself, especially one's own body through accumulation of internal stimuli.

The term was popularized toward the end of the 19th century by British sexologist Havelock Elli ...

, later adopted by psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek: + . is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques"What is psychoanalysis? Of course, one is supposed to answer that it is many things — a theory, a research method, a therapy, a body of knowledge. In what might b ...

.

Ellis was among the pioneering investigators of psychedelic drugs

Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary states of consciousness (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips").Pollan, Michael (2018). ''How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of ...

and the author of one of the first written reports to the public about an experience with mescaline

Mescaline or mescalin (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a naturally occurring psychedelic protoalkaloid of the substituted phenethylamine class, known for its hallucinogenic effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin.

Biological sou ...

, which he conducted on himself in 1896. He supported eugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and served as one of 16 vice-presidents of the Eugenics Society

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

from 1909 to 1912.

Early life and career

Ellis, son of Edward Peppen Ellis and Susannah Mary Wheatley, was born inCroydon

Croydon is a large town in south London, England, south of Charing Cross. Part of the London Borough of Croydon, a local government district of Greater London. It is one of the largest commercial districts in Greater London, with an extensi ...

, Surrey

Surrey () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South East England, bordering Greater London to the south west. Surrey has a large rural area, and several significant urban areas which form part of the Greater London Built-up Area. ...

(now part of Greater London

Greater may refer to:

*Greatness, the state of being great

*Greater than, in inequality (mathematics), inequality

*Greater (film), ''Greater'' (film), a 2016 American film

*Greater (flamingo), the oldest flamingo on record

*Greater (song), "Greate ...

). He had four sisters, none of whom married. His father was a sea captain and an Anglican, while his mother was the daughter of a sea captain who had many other relatives that lived on or near the sea. When he was seven his father took him on one of his voyages, during which they called at Sydney

Sydney ( ) is the capital city of the state of New South Wales, and the most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Located on Australia's east coast, the metropolis surrounds Sydney Harbour and extends about towards the Blue Mountain ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

; Callao

Callao () is a Peruvian seaside city and Regions of Peru, region on the Pacific Ocean in the Lima metropolitan area. Callao is Peru's chief seaport and home to its main airport, Jorge Chávez International Airport. Callao municipality consists o ...

, Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

; and Antwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

. After his return, Ellis attended the French and German College near Wimbledon

Wimbledon most often refers to:

* Wimbledon, London, a district of southwest London

* Wimbledon Championships, the oldest tennis tournament in the world and one of the four Grand Slam championships

Wimbledon may also refer to:

Places London

* ...

, and afterward attended a school in Mitcham

Mitcham is an area within the London Borough of Merton in South London, England. It is centred southwest of Charing Cross. Originally a village in the county of Surrey, today it is mainly a residential suburb, and includes Mitcham Common. It h ...

.

In April 1875, Ellis sailed on his father's ship for Australia; soon after his arrival in Sydney, he obtained a position as a master at a private school. After the discovery of his lack of training, he was fired and became a tutor for a family living a few miles from Carcoar, New South Wales

Carcoar is a town in the Central West (New South Wales), Central West region of New South Wales, Australia, in Blayney Shire. In 2016, the town had a population of 200 people. It is situated just off the Mid-Western Highway 258 km west of ...

. He spent a year there and then obtained a position as a master at a grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented secondary school ...

in Grafton, New South Wales

Grafton ( Bundjalung-Yugambeh: Gumbin Gir) is a city in the Northern Rivers region of the Australian state of New South Wales. It is located on the Clarence River, approximately by road north-northeast of the state capital Sydney. The closest m ...

. The headmaster had died and Ellis carried on at the school for that year, but was unsuccessful.

At the end of the year, he returned to Sydney and, after three months' training, was given charge of two government part-time elementary schools, one at Sparkes Creek, near Scone, New South Wales

Scone is a town in the Upper Hunter Shire in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia. At the 2006 census, Scone had a population of 5,624 people. It is on the New England Highway north of Muswellbrook about 270 kilometres north of Sydn ...

, and the other at Junction Creek. He lived at the school house on Sparkes Creek for a year. He wrote in his autobiography, "In Australia, I gained health of body, I attained peace of soul, my life task was revealed to me, I was able to decide on a professional vocation, I became an artist in literature; these five points covered the whole activity of my life in the world. Some of them I should doubtless have reached without the aid of the Australian environment, scarcely all, and most of them I could never have achieved so completely if chance had not cast me into the solitude of the Liverpool Range

The Liverpool Range is a mountain range and a lava-field province in New South Wales, Australia.

The eastern peaks of the range were the traditional territory of the Wonnarua people.

Geography

The Liverpool Range starts from the volcanic plate ...

."

Medicine and psychology

Ellis returned to England in April 1879. He had decided to take up the study of sex and felt his first step must be to qualify as a physician. He studied at St Thomas's Hospital Medical School, now part ofKing's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King's ...

, but never had a regular medical practice. His training was aided by a small legacy

In law, a legacy is something held and transferred to someone as their inheritance, as by will and testament. Personal effects, family property, marriage property or collective property gained by will of real property.

Legacy or legacies may refer ...

and also income earned from editing works in the Mermaid Series of lesser known Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. He joined The Fellowship of the New Life

The Fellowship of the New Life was a British organisation in the 19th century, most famous for a splinter group, the Fabian Society.

It was founded in 1883, by the Scottish intellectual Thomas Davidson. Fellowship members included the poet Edw ...

in 1883, meeting other social reformers Eleanor Marx

Jenny Julia Eleanor Marx (16 January 1855 – 31 March 1898), sometimes called Eleanor Aveling and known to her family as Tussy, was the English-born youngest daughter of Karl Marx. She was herself a socialist activist who sometimes worked as a ...

, Edward Carpenter

Edward Carpenter (29 August 1844 – 28 June 1929) was an English utopian socialist, poet, philosopher, anthologist, an early activist for gay rightsWarren Allen Smith: ''Who's Who in Hell, A Handbook and International Directory for Human ...

and George Bernard Shaw

George Bernard Shaw (26 July 1856 – 2 November 1950), known at his insistence simply as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from ...

.

The 1897 English translation of Ellis's book ''Sexual Inversion'', co-authored with John Addington Symonds

John Addington Symonds, Jr. (; 5 October 1840 – 19 April 1893) was an English poet and literary critic. A cultural historian, he was known for his work on the Renaissance, as well as numerous biographies of writers and artists. Although m ...

and originally published in German in 1896, was the first English medical textbook on homosexuality. It describes male homosexual relations as well as adolescent rape. Ellis wrote the first objective study of homosexuality, as he did not characterise it as a disease, immoral, or a crime. The work assumes that same-sex love transcended age taboos

A taboo or tabu is a social group's ban, prohibition, or avoidance of something (usually an utterance or behavior) based on the group's sense that it is excessively repulsive, sacred, or allowed only for certain persons.''Encyclopædia Britannica ...

as well as gender taboo. The work also uses the term bisexual throughout.The first edition of the book was bought-out by the executor of Symond's estate, who forbade any mention of Symonds in the second edition.

In 1897 a bookseller was prosecuted for stocking Ellis's book. Although the term ''homosexual'' is attributed to Ellis, he wrote in 1897, "'Homosexual' is a barbarously hybrid word, and I claim no responsibility for it." In fact, the word ''homosexual'' was coined in 1868 by the Hungarian author Karl-Maria Kertbeny

Károly Mária Kertbeny (or Karl Maria Benkert) (28 February 1824 – 23 January 1882) was a Hungarian journalist, translator, memoirist and human rights campaigner. He is best known for coining the words ''heterosexual'' and ''homosexual'' as ...

.

Ellis may have developed psychological concepts of autoeroticism

Autoeroticism or autosexuality is a practice of sexually stimulating oneself, especially one's own body through accumulation of internal stimuli.

The term was popularized toward the end of the 19th century by British sexologist Havelock Elli ...

and narcissism

Narcissism is a self-centered personality style characterized as having an excessive interest in one's physical appearance or image and an excessive preoccupation with one's own needs, often at the expense of others.

Narcissism exists on a co ...

, both of which were later developed further by Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies explained as originatin ...

. Ellis's influence may have reached Radclyffe Hall

Marguerite Antonia Radclyffe Hall (12 August 1880 – 7 October 1943) was an English poet and author, best known for the novel ''The Well of Loneliness'', a groundbreaking work in lesbian literature. In adulthood, Hall often went by the name Jo ...

, who would have been about 17 years old at the time ''Sexual Inversion'' was published. She later referred to herself as a sexual invert and wrote of female "sexual inverts" in ''Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself

Miss (pronounced ) is an English language honorific typically used for a girl, for an unmarried woman (when not using another title such as "Doctor" or " Dame"), or for a married woman retaining her maiden name. Originating in the 17th century, i ...

'' and ''The Well of Loneliness

''The Well of Loneliness'' is a lesbian novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928 by Jonathan Cape. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose " sexual inversion" (hom ...

''. When Ellis bowed out as the star witness in the trial of ''The Well of Loneliness

''The Well of Loneliness'' is a lesbian novel by British author Radclyffe Hall that was first published in 1928 by Jonathan Cape. It follows the life of Stephen Gordon, an Englishwoman from an upper-class family whose " sexual inversion" (hom ...

'' on 14 May 1928, Norman Haire

Norman Haire, born Norman Zions (21 January 1892, Sydney – 11 September 1952, London) was an Australian medical practitioner and sexologist. He has been called "the most prominent sexologist in Britain" between the wars.

Life

When Norman was b ...

was set to replace him but no witnesses were called.

Eonism

Ellis studied what today are calledtransgender

A transgender (often abbreviated as trans) person is someone whose gender identity or gender expression does not correspond with their sex assigned at birth. Many transgender people experience dysphoria, which they seek to alleviate through tr ...

phenomena. Together with Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician and sexologist.

Hirschfeld was educated in philosophy, philology and medicine. An outspoken advocate for sexual minorities, Hirschfeld founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Com ...

, Havelock Ellis is considered a major figure in the history of sexology to establish a new category that was separate and distinct from homosexuality. Aware of Hirschfeld's studies of transvestism

Transvestism is the practice of dressing in a manner traditionally associated with the opposite sex. In some cultures, transvestism is practiced for religious, traditional, or ceremonial reasons. The term is considered outdated in Western ...

, but disagreeing with his terminology, in 1913 Ellis proposed the term ''sexo-aesthetic inversion'' to describe the phenomenon. In 1920 he coined the term ''eonism'', which he derived from the name of a historical figure, the Chevalier d'Éon

Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d'Éon de Beaumont or Charlotte-Geneviève-Louise-Augusta-Andréa-Timothéa d'Éon de Beaumont (5 October 172821 May 1810), usually known as the Chevalier d'Éon or the Chevalière d'Éon ( is t ...

. Ellis explained:

Ellis found eonism to be "a remarkably common anomaly", and "next in frequency to homosexuality among sexual deviation

Paraphilia (previously known as sexual perversion and sexual deviation) is the experience of intense sexual arousal to atypical objects, situations, fantasies, behaviors, or individuals. It has also been defined as sexual interest in anything o ...

s", and categorized it as "among the transitional or intermediate forms of sexuality". As in the Freudian tradition, Ellis postulated that a "too close attachment to the mother" may encourage eonism, but also considered that it "probably invokes some defective endocrine balance".

Marriage

In November 1891, at the age of 32, and reportedly still a virgin, Ellis married the English writer and proponent of

In November 1891, at the age of 32, and reportedly still a virgin, Ellis married the English writer and proponent of women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st centuries. In some countries, ...

Edith Lees. From the beginning, their marriage was unconventional, as Edith Lees was openly bisexual. At the end of the honeymoon, Ellis went back to his bachelor rooms in Paddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Paddi ...

. She lived at Fellowship House. Their "open marriage

Open marriage is a form of non-monogamy in which the partners of a dyadic marriage agree that each may engage in extramarital sexual relationships, without this being regarded by them as infidelity, and consider or establish an open relatio ...

" was the central subject in Ellis's autobiography, ''My Life''. Ellis reportedly had an affair with Margaret Sanger

Margaret Higgins Sanger (born Margaret Louise Higgins; September 14, 1879September 6, 1966), also known as Margaret Sanger Slee, was an American birth control activist, sex educator, writer, and nurse. Sanger popularized the term "birth control ...

.

According to Ellis in ''My Life'', his friends were much amused at his being considered an expert on sex. Some knew that he reportedly suffered from impotence

Erectile dysfunction (ED), also called impotence, is the type of sexual dysfunction in which the penis fails to become or stay erect during sexual activity. It is the most common sexual problem in men.Cunningham GR, Rosen RC. Overview of mal ...

until the age of 60. He then discovered that he could become aroused by the sight of a woman urinating. Ellis named this "undinism". After his wife died, Ellis formed a relationship with a French woman, Françoise Lafitte.

Eugenics

Ellis was a supporter ofeugenics

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

. He served as vice-president to the Eugenics Education Society

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

and wrote on the subject, among others, in ''The Task of Social Hygiene'':

In his early writings, it was clear that Ellis concurred with the notion that there was a system of racial hierarchies, and that non-western cultures were considered to be "lower races". Before explicitly talking about eugenic topics, he used the prevalence of homosexuality in these 'lower races' to indicate the universality of the behavior. In his work, ''Sexual Inversions'', where Ellis presented numerous cases of homosexuality in Britain, he was always careful to mention the race of the subject and the health of the person's 'stock', which included their neuropathic conditions and the health of their parents. However, Ellis was clear to assert that he did not feel that homosexuality was an issue that eugenics needed to actively deal with, as he felt that once the practice was accepted in society, those with homosexual tendencies would comfortably choose not to marry, and thus would cease to pass the 'homosexual heredity' along.

In a debate in the Sociological Society

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of empirical investigation and ...

, Ellis corresponded with the eugenicist Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton, FRS FRAI (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911), was an English Victorian era polymath: a statistician, sociologist, psychologist, anthropologist, tropical explorer, geographer, inventor, meteorologist, proto- ...

, who was presenting a paper in support of marriage restrictions. While Galton analogized eugenics to breeding domesticated animals, Ellis felt that a greater sense of caution was needed before applying the eugenic regulations to populations, as "we have scarcely yet realized how subtle and far-reaching hereditary influences are." Instead, because unlike domesticated animals, humans were in charge of who they mated with, Ellis argued that a greater emphasis was needed on public education about how vital this issue was. Ellis thus held much more moderate views than many contemporary eugenicists. In fact, Ellis also fundamentally disagreed with Galton's leading ideas that procreation restrictions were the same as marriage restrictions. Ellis believed that those who should not procreate should still be able to gain all the other benefits of marriage, and to not allow that was an intolerable burden. This, in his mind, was what led to eugenics being "misunderstood, ridiculed, and regarded as a fad".

Throughout his life, Ellis was both a member and later a council member of the Eugenics Society. Moreover, he played a role on the General Committee of the First International Eugenics Congress.

Sexual impulse in youth

Ellis' 1933 book, ''Psychology of Sex'', is one of the many manifestations of his interest in human sexuality. In this book, he goes into vivid detail of how children can experience sexuality differently in terms of time and intensity. He mentions that it was previously believed that, in childhood, humans had no sex impulse at all. "If it is possible to maintain that the sex impulse has no normal existence in early life, then every manifestation of it at that period must be 'perverse, he adds. He continues by stating that, even in the early development and lower functional levels of the genitalia, there is a wide range of variation in terms of sexual stimulation. He claims that the ability of some infants producing genital reactions, seen as "reflex signs of irritation" are typically not vividly remembered. Since the details of these manifestations are not remembered, there is no possible way to determine them as pleasurable. However, Ellis claims that many people of both sexes can recall having agreeable sensations with the genitalia as a child. "They are not (as is sometimes imagined) repressed." They are, however, not usually mentioned to adults. Ellis argues that they typically stand out and are remembered for the sole contrast of the intense encounter to any other ordinary experience. Ellis claims that sexual self-excitement is known to happen at an early age. He references authors like Marc, Fonssagrives, and Perez in France, who published their findings in the nineteenth century. These "early ages" are not strictly limited to ages close to puberty, as can be seen in their findings. These authors provide cases for children of both sexes who have masturbated from the age of three or four. Ellis references Robie's findings that boys' first sex feelings appear between the ages of five and fourteen. For girls, this age ranges from eight to nineteen. For both sexes, these first sexual experiences arise more frequently during the later years as opposed to the earlier years. Ellis then references G.V. Hamilton's studies that found twenty percent of males and fourteen percent of females have pleasurable experiences with their sex organs before the age of six. This is only supplemented by Ellis' reference to Katharine Davis' studies, which found that twenty to twenty-nine percent of boys and forty-nine to fifty-one percent of girls were masturbating by the age of eleven. However, in the next three years after, boys' percentages exceeded those of girls. Ellis also contributed to the idea of varying levels of sexual excitation. He asserts it is a mistake to assume all children are able to experience genital arousal or pleasurable erotic sensations. He proposes cases where an innocent child is led to believe that stimulation of the genitalia will result in a pleasurable erection. Some of these children may fail and not be able to experience this, either pleasure or an erection, until puberty. Ellis concludes, then, that children are capable of a "wide range of genital and sexual aptitude". Ellis even considers ancestry as a contributions to different sexual excitation levels, stating that children of "more unsound heredity" and/or hypersexual parents are "more precociously excitable".Auto-eroticism

Ellis' views of auto-eroticism were very comprehensive, including much more than masturbation. Auto-eroticism, according to Ellis, includes a wide range of phenomena. Ellis states in his 1897 book ''Studies in the Psychology of Sex'', that auto-eroticism ranges from erotic day-dreams, marked by a passivity shown by the subject, to "unshamed efforts at sexual self-manipulation witnessed among the insane". Ellis also argues that auto-erotic impulses can be heightened by bodily processes like menstrual flow. During this time, he says, women, who would otherwise not feel a strong propensity for auto-eroticism, increase their masturbation patterns. This trend is absent, however, in women without a conscious acceptance of their sexual feelings and in a small percentage of women suffering from a sexual or general ailment which result in a significant amount of "sexual anesthesia". Ellis also raises social concern over how auto-erotic tendencies affect marriages. He goes on to tying auto-eroticism to declining marriage rates. As these rates decline, he concludes that auto-eroticism will only increase in both amount and intensity for both men and women. Therefore, he states, this is an important issue to both the moralist and physician to investigate psychological underpinnings of these experiences and determine an attitude toward them.Smell

Ellis believed that the sense of smell, although ineffective at long ranges, still contributes to sexual attraction, and therefore, to mate selection. In his 1905 book, ''Sexual selection in man'', Ellis makes a claim for the sense of smell in the role of sexual selection. He asserts that while we have evolved out of a great necessity for the sense of smell, we still rely on our sense of smell with sexual selection. The contributions that smell makes in sexual attraction can even be heightened with certain climates. Ellis states that with warmer climates come a heightened sensitivity to sexual and other positive feelings of smell among normal populations. Because of this, he believes people are often delighted by odors in the East, particularly in India, in "Hebrew and Mohammedan lands". Ellis then continues by describing the distinct odours in various races, noting that the Japanese race has the least intense of bodily odours. Ellis concludes his argument by stating, "On the whole, it may be said that in the usual life of man odours play a not inconsiderable part and raise problems which are not without interest, but that their demonstrable part in actual sexual selection is comparatively small."Views on women and birth control

Ellis favoured feminism from a eugenic perspective, feeling that the enhanced social, economic, and sexual choices that feminism provided for women would result in women choosing partners who were more eugenically sound. In his view, intelligent women would not choose, nor be forced to marry and procreate with feeble-minded men. Ellis viewed birth control as merely the continuation of an evolutionary progression, noting that natural progress has always consisted of increasing impediments to reproduction, which lead to a lower quantity of offspring, but a much higher quality of them. From a eugenic perspective, birth control was an invaluable instrument for the elevation of the race. However, Ellis noted that birth control could not be used randomly in a way that could have a detrimental impact by reducing conception, but rather needed to be used in a targeted manner to improve the qualities of certain 'stocks'. He observed that it was unfortunately the 'superior stocks' who had knowledge of and used birth control while the 'inferior stocks' propagated without checks. Ellis's solution to this was a focus on contraceptives in education, as this would disseminate the knowledge in the populations that he felt needed them the most. Ellis argued that birth control was the only available way of making eugenic selection practicable, as the only other option was wide-scale abstention from intercourse for those who were 'unfit'.Views on sterilization

Ellis was strongly opposed to the idea of castration of either sex for eugenic purposes. In 1909, regulations were introduced at the Cantonal Asylum inBern

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

which allowed those deemed 'unfit' and with strong sexual inclinations to be mandatorily sterilized. In a particular instance, several men and women, including epileptics and paedophiles, were castrated, some of whom voluntarily requested it. While the results were positive, in that none of the subjects were found guilty of any more sexual offences, Ellis remained staunchly opposed to the practice. His view on the origin of these inclinations was that sexual impulses do not reside in the sexual organs, but rather they persist in the brain. Moreover, he posited that the sexual glands provided an important source of internal secretions vital for the functioning of the organism, and thus the glands' removal could greatly injure the patient.

However, already in his time, Ellis was witness to the rise of vasectomies and ligatures of the Fallopian tubes, which performed the same sterilization without removing the whole organ. In these cases, Ellis was much more favourable, yet still maintaining that "sterilization of the unfit, if it is to be a practical and humane measure commanding general approval, must be voluntary on the part of the person undergoing it, and never compulsory." His opposition to such a system was not only rooted in morality. Rather, Ellis also considered the practicality of the situation, hypothesizing that if an already mentally unfit man is forced to undergo sterilization, he would only become more ill-balanced, and would end up committing more anti-social acts.

Though Ellis was never at ease with the idea of forced sterilizations, he was willing to find ways to circumvent that restriction. His focus was on the social ends of eugenics, and as a means to it, Ellis was in no way against 'persuading' 'volunteers' to undergo sterilization by withdrawing Poor Relief from them. While he preferred to convince those he deemed unfit using education, Ellis supported coercion as a tool. Furthermore, he supported adding ideas about eugenics and birth control to the education system in order to restructure society, and to promote social hygiene. For Ellis, sterilization seemed to be the only eugenic instrument that could be used on the mentally unfit. In fact, in his publication ''The Sterilization of the Unfit'', Ellis argued that even institutionalization could not guarantee the complete prevention of procreation between the unfit, and thus, "the burdens of society, to say nothing of the race, are being multiplied. It is not possible to view sterilization with enthusiasm when applied to any class of people…but what, I ask myself, is the practical alternative?"

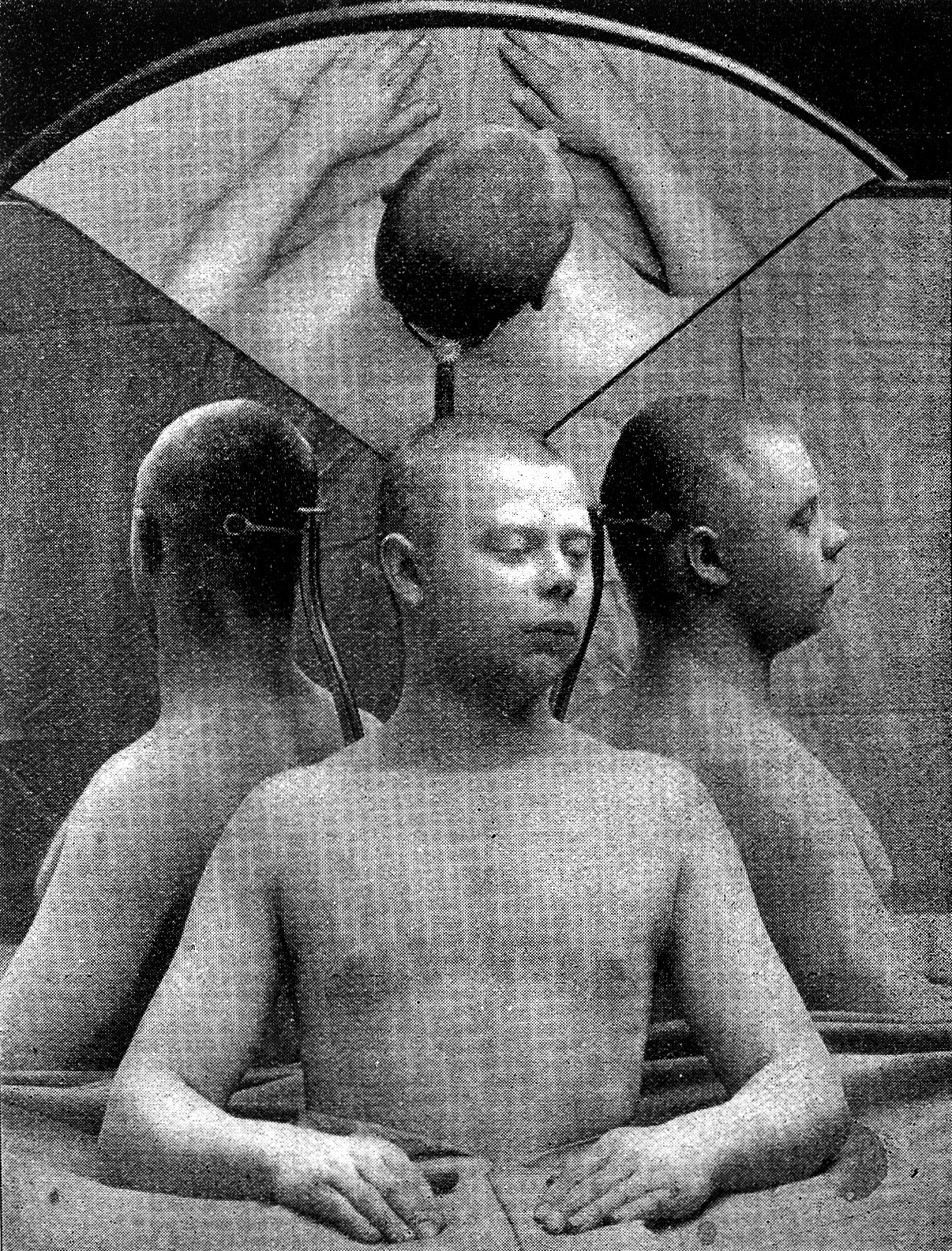

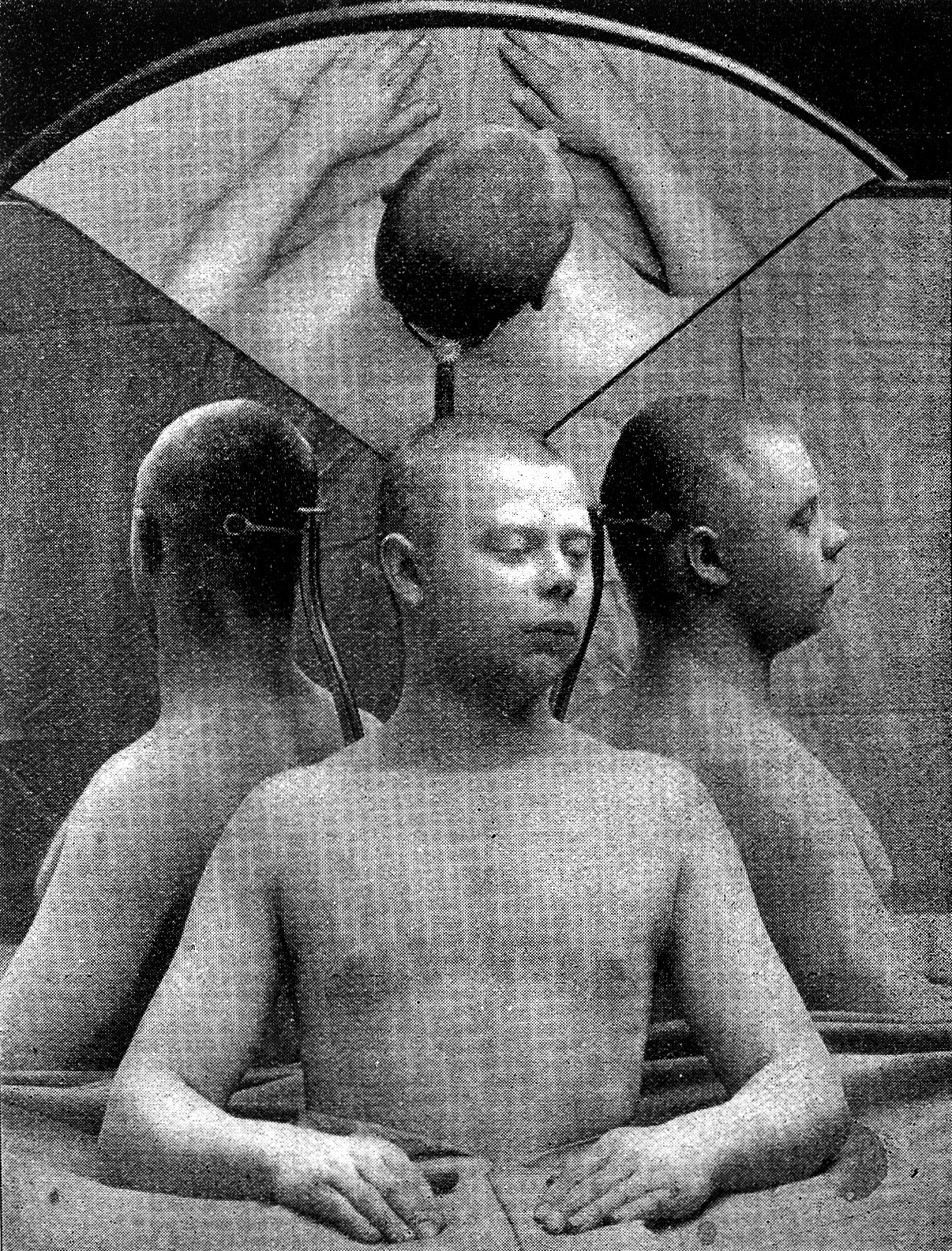

Psychedelics

Ellis was among the pioneering investigators ofpsychedelic drug

Psychedelics are a subclass of hallucinogenic drugs whose primary effect is to trigger non-ordinary states of consciousness (known as psychedelic experiences or "trips").Pollan, Michael (2018). ''How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science o ...

s and the author of one of the first written reports to the public about an experience with mescaline

Mescaline or mescalin (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenethylamine) is a naturally occurring psychedelic protoalkaloid of the substituted phenethylamine class, known for its hallucinogenic effects comparable to those of LSD and psilocybin.

Biological sou ...

, which he conducted on himself in 1896. He consumed a brew made of three ''Lophophora williamsii

The peyote (; ''Lophophora williamsii'' ) is a small, spineless cactus which contains psychoactive alkaloids, particularly mescaline. ''Peyote'' is a Spanish word derived from the Nahuatl (), meaning "caterpillar cocoon", from a root , "to ...

'' buds in the afternoon of Good Friday

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Hol ...

alone in his apartment in Temple, London

The Temple is an area of London surrounding Temple Church. It is one of the main legal districts in London and a notable centre for English law, historically and in the present day. It consists of the Inner Temple and the Middle Temple, which a ...

. During the experience, lasting for about 24 hours, he noted a plethora of extremely vivid, complex, colourful, pleasantly smelling hallucination

A hallucination is a perception in the absence of an external stimulus that has the qualities of a real perception. Hallucinations are vivid, substantial, and are perceived to be located in external objective space. Hallucination is a combinatio ...

s, consisting both of abstract geometrical patterns and objects such as butterflies and other insects. He published the account of the experience in ''The Contemporary Review

''The Contemporary Review'' is a British biannual, formerly quarterly, magazine. It has an uncertain future as of 2013.

History

The magazine was established in 1866 by Alexander Strahan and a group of intellectuals anxious to promote intellig ...

'' in 1898 (''Mescal: A New Artificial Paradise''). The title of the article alludes to an earlier work on the effects of mind-altering substances

A psychoactive drug, psychopharmaceutical, psychoactive agent or psychotropic drug is a chemical substance, that changes functions of the nervous system, and results in alterations in perception, mood, consciousness, cognition or behavior.

T ...

, an 1860 book '' Les Paradis artificiels'' by French poet Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poetry, French poet who also produced notable work as an essayist and art critic. His poems exhibit mastery in the handling of rhyme and rhythm, contain an exoticis ...

(containing descriptions of experiments with opium

Opium (or poppy tears, scientific name: ''Lachryma papaveris'') is dried latex obtained from the seed capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid morphine, which i ...

and hashish).

Ellis was so impressed with the aesthetic quality of the experience that he gave some specimens of peyote to the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

poet W.B. Yeats, a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn ( la, Ordo Hermeticus Aurorae Aureae), more commonly the Golden Dawn (), was a secret society devoted to the study and practice of occult Hermeticism and metaphysics during the late 19th and early 20th ...

, an organisation of which another mescaline researcher, Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley (; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, painter, novelist, and mountaineer. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pro ...

, was also a member.

Later life and death

Ellis resigned from his position as a Fellow of the Eugenics Society over its stance on sterilization in January 1931.

Ellis spent the last year of his life at

Ellis resigned from his position as a Fellow of the Eugenics Society over its stance on sterilization in January 1931.

Ellis spent the last year of his life at Hintlesham

Hintlesham is a small village in Suffolk, England, situated roughly halfway between Ipswich and Hadleigh. It is in the Belstead Brook electoral division of Suffolk County Council.

The village is notable for Hintlesham Hall, a 16th-century Grad ...

, Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

, where he died in July 1939. He is buried in Golders Green Crematorium

Golders Green Crematorium and Mausoleum was the first crematorium to be opened in London, and one of the oldest crematoria in Britain. The land for the crematorium was purchased in 1900, costing £6,000 (the equivalent of £135,987 in 2021), ...

, in North London.

Works

* '' The Criminal'' (1890)

* ''The New Spirit'' (1890)

* ''The Nationalisation of Health'' (1892)

* ''Man and Woman: A Study of Secondary and Tertiary Sexual Characteristics'' (1894) (revised 1929)

* translator: '' Germinal'' (by

* '' The Criminal'' (1890)

* ''The New Spirit'' (1890)

* ''The Nationalisation of Health'' (1892)

* ''Man and Woman: A Study of Secondary and Tertiary Sexual Characteristics'' (1894) (revised 1929)

* translator: '' Germinal'' (by Zola Zola may refer to:

People

* Zola (name), a list of people with either the surname or given name

* Zola (musician) (born 1977), South African entertainer

* Zola (rapper), French rapper

* Émile Zola, a major nineteenth-century French writer

Plac ...

) (1895) (reissued 1933)

* with J.A. Symonds

* Studies in the Psychology of Sex (1897–1928) six volumes (listed below)

*

* ''Affirmations'' (1898)

*

* ''The Nineteenth Century'' (1900)

*

*

* ''A Study of British Genius

''A Study of British Genius'' is a 1904 book by Havelock Ellis published by Hurst and Blackett.

Contents

There is an introduction and then the books delves into chapters on race and nationality, social class, heredity, childhood, marriage, l ...

'' (1904)

*

*

* ''The Soul of Spain'' (1908)

*

*

* ''The Problem of Race-Regeneration'' (1911)

* ''The World of Dreams'' (1911) (new edition 1926)

*

*

* ''The Task of Social Hygiene'' (1912)

*

* ''The Philosophy of Conflict'' (1919)

* ''On Life and Sex: Essays of Love and Virtue'' (1921)

*

* '' Little Essays of Love and Virtue'' (1922)

*

*

* ''Sonnets, with Folk Songs from the Spanish'' (1925)

* ''Eonism

Henry Havelock Ellis (2 February 1859 – 8 July 1939) was an English physician, eugenicist, writer, Progressivism, progressive intellectual and social reformer who studied human sexuality. He co-wrote the first medical textbook in English on ho ...

and Other Supplementary Studies'' (1928)

* ''Studies in the Psychology of Sex Vol. 7

''Studies in the Psychology of Sex: Volume 7'' is a book published in 1928 by the English physician and writer Havelock Ellis (1859–1939). Ellis was an expert of human sexuality but was impotent until the age of 60 and married to an open lesbia ...

'' (1928)

* ''The Art of Life'' (1929) (selected and arranged by Mrs. S. Herbert)

* ''More Essays of Love and Virtue'' (1931)

* ed.: ''James Hinton: Life in Nature'' (1931)

*

*

* ed.: ''Imaginary Conversations

''Imaginary Conversations'' is Walter Savage Landor's most celebrated prose work. Begun in 1823, sections were constantly revised and were ultimately published in a series of five volumes. The conversations were in the tradition of dialogues with ...

and Poems: A Selection'', by Walter Savage Landor

Walter Savage Landor (30 January 177517 September 1864) was an English writer, poet, and activist. His best known works were the prose ''Imaginary Conversations,'' and the poem "Rose Aylmer," but the critical acclaim he received from contempora ...

(1933)

* ''Chapman'' (1934)

* ''My Confessional'' (1934)

* ''Questions of Our Day'' (1934)

* ''From Rousseau to Proust'' (1935)

* ''Selected Essays'' (1936)

* ''Poems'' (1937) (selected by John Gawsworth

Terence Ian Fytton Armstrong (29 June 1912 – 23 September 1970), better known as John Gawsworth (and also sometimes known as T. I. F. Armstrong), was a British writer, poet and compiler of anthologies, both of poetry and of short stories. He ...

; pseudonym of T. Fytton Armstrong)

* ''Love and Marriage'' (1938) (with others)

*

* ''Sex Compatibility in Marriage'' (1939)

* ''From Marlowe to Shaw'' (1950) (ed. by J. Gawsworth)

* ''The Genius of Europe'' (1950)

* ''Sex and Marriage'' (1951) (ed. by J. Gawsworth)

* ''The Unpublished Letters of Havelock Ellis to Joseph Ishill'' (1954)

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * (U.S. title)External links

* * *Havelock Ellis papers (MS 195). Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library

*

Henry Havelock Ellis papers from the Historic Psychiatry Collection, Menninger Archives, Kansas Historical Society

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Ellis, Havelock 1859 births 1939 deaths 19th-century English non-fiction writers 20th-century English non-fiction writers Alumni of King's College London Alumni of St Thomas's Hospital Medical School British sexologists English eugenicists English psychologists People from Croydon British psychedelic drug advocates British relationships and sexuality writers Medical writers on LGBT topics British social reformers Transgender studies academics Victorian writers Translators of Émile Zola