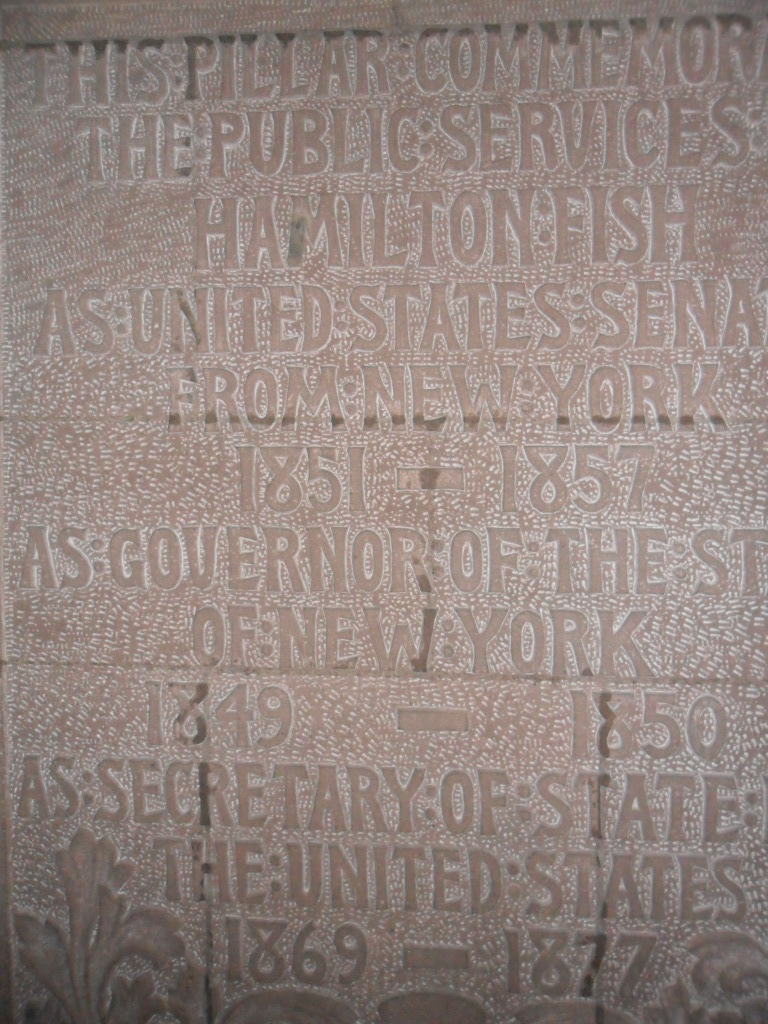

Hamilton Fish (August 3, 1808September 7, 1893) was an American politician who served as the

16th

16 (sixteen) is the natural number following 15 and preceding 17. 16 is a composite number, and a square number, being 42 = 4 × 4. It is the smallest number with exactly five divisors, its proper divisors being , , and .

In English speech, ...

Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has ...

from 1849 to 1850, a

United States Senator

The United States Senate is the Upper house, upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives being the Lower house, lower chamber. Together they compose the national Bica ...

from

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

from 1851 to 1857 and the 26th

United States Secretary of State

The United States secretary of state is a member of the executive branch of the federal government of the United States and the head of the U.S. Department of State. The office holder is one of the highest ranking members of the president's Ca ...

from 1869 to 1877. Fish is recognized as the "pillar" of the

presidency of Ulysses S. Grant

The presidency of Ulysses S. Grant began on March 4, 1869, when Ulysses S. Grant was inaugurated as the 18th president of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1877. The Reconstruction era took place during Grant's two terms of office. The Ku ...

and considered one of the best U.S. Secretaries of State by scholars, known for his judiciousness and efforts towards reform and diplomatic moderation.

[(December 1981), ''The Ten Best Secretaries Of State...''.] Fish settled the controversial

''Alabama'' Claims with Great Britain through his development of the concept of

international arbitration.

Fish and Grant kept the United States out of war with Spain over Cuban independence by coolly handling the volatile

''Virginius'' Incident.

In 1875, Fish initiated the

Overthrow of the Kingdom of Hawaii

The overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom was a ''coup d'état'' against Queen Liliʻuokalani, which took place on January 17, 1893, on the island of Oahu and led by the Committee of Safety (Hawaii), Committee of Safety, composed of seven foreign ...

that would ultimately lead to Hawaiian statehood, by having negotiated a

reciprocal trade treaty for the island nation's sugar production.

He also organized a peace conference and treaty in Washington D.C. between South American countries and Spain.

[United States Department of State (December 4, 1871), ''Foreign relations of the United States'', pp. 775–777.] Fish worked with

James Milton Turner

James Milton Turner (1840 – November 1, 1915) was a Reconstruction Era political leader, activist, educator, and diplomat. As consul general to Liberia, he was the first African-American to serve in the U.S. diplomatic corps.

Early life

Turn ...

, America's first African American consul, to settle the

Liberian-Grebo war.

President Grant said he trusted Fish the most for political advice.

Fish came from prominence and wealth, his family being of

Dutch American

Dutch Americans ( nl, Nederlandse Amerikanen) are Americans of Dutch descent whose ancestors came from the Netherlands in the recent or distant past. Dutch settlement in the Americas started in 1613 with New Amsterdam, which was exchanged with ...

heritage long-established in

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. He attended

Columbia College, and later passed the bar. Initially working as New York's

commissioner of deeds, he ran unsuccessfully for New York State Assembly as a Whig candidate in 1834. After marrying, he returned to politics and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1843. Fish ran for New York's lieutenant governor in 1846, falling to a Democratic

Anti-Rent Party contender. When the office was vacated in 1847, Fish ran and was elected to the position. In 1848 he ran and was elected governor of New York, serving one term. In 1851, he was elected U.S. Senator for the state of New York, serving one term. Fish gained valuable experience serving on the

U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pr ...

. During the 1850s he became a Republican after the Whig party dissolved. In terms of the slavery issue, Fish was a moderate, having disapproved of the

Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

and the expansion of slavery.

After traveling to Europe, Fish returned to America and supported

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

as the Republican candidate for president in 1860. During the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, Fish raised money for the Union war effort and served on Lincoln's presidential commission that made successful arrangements for Union and

Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

troop prisoner exchanges. Fish returned to his law practice after the Civil War, and was thought to have retired from political life. When

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

was elected president in 1868, he appointed Fish as U.S. Secretary of State in 1869. Fish took on the State Department with vigor, reorganized the office, and established

civil service reform. During his 8-year tenure, Fish had to contend with Cuban belligerency, the settlement of the ''Alabama'' claims, Canada–US border disputes, and the ''Virginius'' incident. Fish implemented the new concept of international arbitration, where disputes between countries were settled by negotiations, rather than military conflicts. Fish was involved in a political

feud

A feud , referred to in more extreme cases as a blood feud, vendetta, faida, clan war, gang war, or private war, is a long-running argument or fight, often between social groups of people, especially families or clans. Feuds begin because one part ...

between Senator

Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

and President Grant in the latter's unsuccessful efforts to

annex

Annex or Annexe refers to a building joined to or associated with a main building, providing additional space or accommodations.

It may also refer to:

Places

* The Annex, a neighbourhood in downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada

* The Annex (New H ...

the

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

. Fish organized a naval expedition in an unsuccessful attempt to open trade with

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

in 1871. Leaving office and politics in 1877, Fish returned to private life and continued to serve on various historical associations. Fish died quietly of old age in his luxurious New York State home in 1893.

Historically, Fish has been praised for his calm demeanor under pressure, honesty, loyalty, modesty, and for his talented statesmanship during his tenure under President Grant, briefly serving under President Hayes. The hallmark of his career was the Treaty of Washington, peacefully settling the Alabama Claims. Fish also ably handled the ''Virginus'' incident, keeping the United States out of war with Spain. Fish's lesser-known, but successful South American détente and armistice, has been forgotten by historians. Fish, while Secretary of State, lacked empathy for the plight of

African Americans

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

,

and opposed annexation of

Latin race countries. Fish has been traditionally viewed to be one of America's top ranked Secretaries of State by historians. Fish's male descendants would later serve in the U.S. House of Representatives for three generations.

Early life, education, and career

Hamilton Fish was born on August 3, 1808, at what is now known as the

Hamilton Fish House

The Hamilton Fish House, also known as the Stuyvesant Fish House and Nicholas and Elizabeth Stuyvesant Fish House, is where Hamilton Fish (1808–93), later Governor and Senator of New York, was born and resided from 1808 to 1838. It is at 21 S ...

in

Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

, New York City, to

Nicholas Fish

Nicholas Fish (August 28, 1758 – June 20, 1833) was an American Revolutionary War soldier. He was the first Adjutant General of New York.

Early life

Fish was born on August 28, 1758 into a wealthy New York City family. He was the son of Jon ...

and Elizabeth Stuyvesant (a daughter of

Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant (; in Dutch also ''Pieter'' and ''Petrus'' Stuyvesant, ; 1610 – August 1672)Mooney, James E. "Stuyvesant, Peter" in p.1256 was a Dutch colonial officer who served as the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Net ...

and direct descendant of

New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

's Director-General

Peter Stuyvesant

Peter Stuyvesant (; in Dutch also ''Pieter'' and ''Petrus'' Stuyvesant, ; 1610 – August 1672)Mooney, James E. "Stuyvesant, Peter" in p.1256 was a Dutch colonial officer who served as the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Net ...

). He was named after his parents' friend

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

.

Nicholas Fish (1758–1833) was a leading

Federalist

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

politician and notable figure of the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

. Colonel Fish was active in the

Yorktown Campaign

The Yorktown campaign, also known as the Virginia campaign, was a series of military maneuvers and battles during the American Revolutionary War that culminated in the siege of Yorktown in October 1781. The result of the campaign was the surren ...

that resulted in the surrender of Lord Cornwallis.

Peter Stuyvesant was a prominent founder of New York, then a Dutch Colony, and his family owned much property in Manhattan.

Fish received his primary education at the private school of M. Bancel.

In 1827, Fish graduated from

Columbia College, having obtained high honors.

At Columbia, Fish became fluent in French, a language that would later help him as U.S. Secretary of State.

After his graduation, Fish studied law for three years in the law office of

Peter A. Jay

Peter Augustus Jay (January 24, 1776 – February 20, 1843) was a prominent New York lawyer, politician and the eldest son of Founding Father and first United States Chief Justice John Jay.

Early life

Peter Augustus Jay was born at Liberty ...

, served as president of the

Philolexian Society

The Philolexian Society of Columbia University is one of the oldest college literary and debate societies in the United States, and the oldest student group at Columbia. Founded in 1802, the Society aims to "improve its members in Oratory, Compo ...

, and was

admitted to the New York bar in 1830, practicing briefly with

William Beach Lawrence.

Influenced politically by his father, Fish aligned himself to the

Whig Party.

He served as

commissioner of deeds for the city and county of New York from 1831 through 1833, and was an unsuccessful Whig candidate for

New York State Assembly

The New York State Assembly is the lower house of the New York State Legislature, with the New York State Senate being the upper house. There are 150 seats in the Assembly. Assembly members serve two-year terms without term limits.

The Assem ...

in 1834.

Marriage and family

On December 15, 1836, Hamilton Fish married Julia Kean (a descendant of a New Yorker who was a New Jersey governor,

William Livingston

William Livingston (November 30, 1723July 25, 1790) was an American politician who served as the first governor of New Jersey (1776–1790) during the American Revolutionary War. As a New Jersey representative in the Continental Congress, he sig ...

).

The couple's lengthy married life was described as happy and Mrs. Fish was known for her "sagacity and judgement."

The couple had three sons and five daughters.

Hamilton Fish had multiple notable descendants and relatives.

New York political career

U.S. Representative

For eight years after his defeat as a Representative in the New York State Assembly, Fish was reluctant to run for office.

However, Whig party leaders in 1842 convinced him to run for the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

.

In November, Fish was elected to the House of Representatives; having defeated

Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

John McKeon

John McKeon (March 29, 1808, Albany, New York – November 22, 1883, New York City) was an American lawyer and politician from New York. From 1835 to 1837, and 1841 to 1843, he served two non-consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representativ ...

and serving in the

28th Congress from

New York's 6th District between 1843 and 1845.

The Whigs at this time were in the minority in the House; however, Fish gained valued national experience serving on the Committee of Military Affairs.

Fish failed to win a re-election bid for a second term in the House.

Lieutenant Governor

Fish was the Whig candidate for

Lieutenant Governor of New York

The lieutenant governor of New York is a constitutional office in the executive branch of the Government of the State of New York. It is the second highest-ranking official in state government. The lieutenant governor is elected on a ticket wit ...

in 1846, but

was defeated by Democrat

Addison Gardiner

Addison Gardiner (March 19, 1797 – June 5, 1883) was an American lawyer and politician who served as Lieutenant governor of New York from 1845 to 1847 and Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals from 1854 to 1855.

Early life and career

...

who had been endorsed by the

Anti-Rent Party.

Leasing farmers in New York refused to pay rent to large land tract owners and sometimes resorted to violence and intimidation.

Fish had opposed the Anti-Rent Party for the use of illegal tactics not to pay rent.

Gardiner

was elected in May 1847 a judge of the

New York Court of Appeals

The New York Court of Appeals is the highest court in the Unified Court System of the State of New York. The Court of Appeals consists of seven judges: the Chief Judge and six Associate Judges who are appointed by the Governor and confirmed by t ...

and vacated the office of lieutenant governor.

Fish was then in

November 1847 elected to fill the vacancy, and was Lieutenant Governor in 1848.

Lieut. Gov. Fish had a favorable reputation for being "conciliatory" and for his "firmness" over the New York Senate.

Governor

In

November 1848, he was elected

Governor of New York

The governor of New York is the head of government of the U.S. state of New York. The governor is the head of the executive branch of New York's state government and the commander-in-chief of the state's military forces. The governor has ...

, defeating

John A. Dix and

Reuben H. Walworth

Reuben Hyde Walworth (October 26, 1788 – November 27, 1867) was an American lawyer, jurist and politician. Although nominated three times to the United States Supreme Court by President John Tyler in 1844, the U.S. Senate never attempted a ...

, and served from January 1, 1849, to December 31, 1850.

At 40 years of age, Fish was one of the youngest governors to be elected in New York history.

Fish advocated and signed into law free public education facilities throughout New York state.

He also advocated and signed into law the building of an asylum and school for the

intellectually disabled

Intellectual disability (ID), also known as general learning disability in the United Kingdom and formerly mental retardation, Rosa's Law, Pub. L. 111-256124 Stat. 2643(2010). is a generalized neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by signifi ...

.

During his tenure the canal system in the state of New York was increased.

In 1850, Fish recommended that the state legislature form a committee to collect and publish the Colonial Laws of New York.

None of the bills that Governor Fish

vetoed

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto pow ...

were overturned by the New York legislature.

In his annual messages Fish spoke out against the extension of slavery from land acquired from the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

, including California and New Mexico.

His anti-slavery messages gave Fish national attention and President

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader who served as the 12th president of the United States from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States Army, rising to th ...

, also a Whig, was going to nominate Fish to the Treasury Department in a cabinet shakeup.

However Taylor died in office before he could nominate Fish.

Despite his national popularity Fish was not renominated for Governor.

U.S. Senator

After Governor Fish had retired from office he did not openly seek the nomination to be elected U.S. Senator.

However, Fish's supporters, the

William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

-

Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was ins ...

Whigs, in January 1851 nominated him as a candidate for U.S. Senator.

A deadlock ensued over his nomination because one New York legislature Whig Senator was upset about Fish not publicly supporting the

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that defused a political confrontation between slave and free states on the status of territories acquired in the Mexican–Ame ...

.

Before the election Fish had only stated government should enforce the laws.

Although Fish did not favor the spread of slavery he was hesitant to support the

free soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

movement. Finally, when two Democratic Senators who were against Fish's nomination were conspicuously absent, the Senate took action and voted. On March 19, 1851, Fish

was elected a

U.S. Senator from New York

Below is a list of U.S. senators who have represented the State of New York in the United States Senate since 1789. The date of the start of the tenure is either the first day of the legislative term (Senators who were elected regularly before th ...

and he took his seat on December 1, serving alongside future Secretary of State William H. Seward.

In the

United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

, he was a member of the

U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pr ...

until the end of his term on March 4, 1857.

Fish became friends with President

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

's Secretary of State

William L. Marcy and Attorney General

Caleb Cushing

Caleb Cushing (January 17, 1800 – January 2, 1879) was an American Democratic politician and diplomat who served as a Congressman from Massachusetts and Attorney General under President Franklin Pierce. He was an eager proponent of territor ...

.

He was a

Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

for the latter part of his term and was part of a moderately anti-slavery faction. During the 1850s, the Republican Party replaced the Whig Party as the central party against the Democratic Party.

By 1856, Fish privately considered himself a Whig although he knew that the Whig Party was no longer viable politically. Fish was a quiet Senator, rather than an orator, who liked to keep to himself.

Fish often was in disagreement with Senator Sumner, who was firmly opposed to slavery and advocated equality for blacks.

His policy was to vote for legislation on the side of "justice, economy, and public virtue."

He strongly opposed the

repeal

A repeal (O.F. ''rapel'', modern ''rappel'', from ''rapeler'', ''rappeler'', revoke, ''re'' and ''appeler'', appeal) is the removal or reversal of a law. There are two basic types of repeal; a repeal with a re-enactment is used to replace the law ...

of the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and ...

.

Fish often voted with the

Free Soil

The Free Soil Party was a short-lived coalition political party in the United States active from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party. The party was largely focused on the single issue of opposing the expansion of slavery into ...

faction and was strongly against the

Kansas-Nebraska Bill. In February 1855, merchants represented by

Moses H. Grinnell, criticized Fish's bill on immigration and maritime commerce. Fish's bill was designed to protect Irish and German immigrants who were dying on merchant ships during oceanic passage to America. The merchants believed that Fish's bill was oppressive to commercial interests over human interests.

During his tenure, the nation and Congress were in tremendous political upheaval over slavery, that included violence, disorder, and disturbances of the peace.

In 1856, pro-slavery advocates invaded Kansas and used violent tactics against those who were anti-slavery.

In May 1856, Senator Charles Sumner was viciously attacked by

Preston Brooks

Preston Smith Brooks (August 5, 1819 – January 27, 1857) was an American politician and member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina, serving from 1853 until his resignation in July 1856 and again from August 1856 until his ...

in the Senate Chamber.

At the expiration of his term, he traveled with his family to Europe and remained there until shortly before the opening of the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

, when he returned to begin actively campaigning for the election of

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

While in France, Fish studied foreign policy with diplomats and distinguished Americans; having gained valuable experience that would eventually benefit his tenure as Secretary of State.

American Civil War

Fish had several important roles during the American Civil War. Fish's private secretary was involved in the attempt of the merchant ship ''

Star of the West

''Star of the West'' was an American merchant steamship that was launched in 1852 and scuttled by Confederate forces in 1863. In January 1861, the ship was hired by the government of the United States to transport military supplies and reinforc ...

'' to bring relief supplies to

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a sea fort built on an artificial island protecting Charleston, South Carolina from naval invasion. Its origin dates to the War of 1812 when the British invaded Washington by sea. It was still incomplete in 1861 when the Battl ...

in Charleston harbor. During this period, Fish often met with General

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

, commander-in-chief of the

US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

. Fish was dining with Scott in New York when a telegram reported that Confederates had fired on ''Star of the West''. Fish said that this meant war; Scott replied "Don't utter that word, my friend. You don't know what a horrid thing war is."

In 1861–1862, Fish participated in the "Union Defense Committee of the State of New York", which co-operated with the City of New York in raising and equipping

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

troops, and disbursed more than $1 million for the relief of New York volunteers and their families. The committee included chairman John A. Dix,

William M. Evarts

William Maxwell Evarts (February 6, 1818February 28, 1901) was an American lawyer and statesman from New York who served as U.S. Secretary of State, U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator from New York. He was renowned for his skills as a li ...

,

William E. Dodge,

A.T. Stewart

Alexander Turney Stewart (October 12, 1803 – April 10, 1876) was an American entrepreneur who moved to New York and made his multimillion-dollar fortune in the most extensive and lucrative dry goods store in the world.

Stewart was born in L ...

,

John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

, and other New York men. Fish was appointed chairman of the committee after Dix joined the Union Army.

In 1862, President Lincoln appointed Fish and Bishop

Edward R. Ames as commissioners to visit Union prisoners in

Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. The Confederate government, however, would not allow them to enter the city. Instead, Fish and Rev. Ames started the prisoner exchange program which continued virtually unchanged throughout the war. After the war ended, Fish went back to private practice as a lawyer in New York.

From 1860 to 1869, Fish was trustee of

The Bank for Savings in the City of New-York

The Bank for Savings in the City of New York (1819–1982) was one of the earliest banks in the United States and the first savings bank in New York City. Founded in 1816, it was first advertised as "a bank for the poor". It was merged with the Bu ...

stepping down from that role when he became US Secretary of State.

U.S. Secretary of State

Hamilton Fish was appointed

Secretary of State by President

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

and served between March 17, 1869, and March 12, 1877. He was President Grant's longest-serving

Cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

officer. Upon assuming office in 1869, Fish was initially underrated by some statesmen including former Secretaries of State William H. Seward and

John Bigelow

John Bigelow Sr. (November 25, 1817 – December 19, 1911) was an American lawyer, statesman, and historian who edited the complete works of Benjamin Franklin and the first autobiography of Franklin taken from Franklin's previously lost origina ...

. Fish, however, immediately took on the responsibilities of his office with diligence, zeal, and intelligence. Fish's tenure as Secretary of State was lengthy, almost eight years, and he had to contend with many foreign policy issues including the Cuban insurrection, the ''Alabama'' Claims, and the

Franco-Prussian War.

[

During ]Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*'' Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Unio ...

, Fish was not known to sympathize with Grant's policy to eradicate the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and ...

, racism in the Southern states, and promote African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

equality. Fish complained of being bored at Grant's cabinet meetings when Grant's U.S. Attorney General Amos T. Akerman told of atrocities of the Klan against black citizens.Alabama Claims

The ''Alabama'' Claims were a series of demands for damages sought by the government of the United States from the United Kingdom in 1869, for the attacks upon Union merchant ships by Confederate Navy commerce raiders built in British shipyards ...

, Fish told Grant he would resign on August 1, 1871. Grant, however, needed Fish's professional advice and pleaded with Fish to remain in office. Grant told Fish he could not replace him. Fish remained in office, 13 years Grant's senior, even under ill health.

Reformed U.S. State Department 1869

When Fish assumed office he immediately began a series of reforms in the Department of State

The United States Department of State (DOS), or State Department, is an executive department of the U.S. federal government responsible for the country's foreign policy and relations. Equivalent to the ministry of foreign affairs of other nati ...

.[

The method of record keeping, however, was cumbersome, having remained the same since ]John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

.[ Rather than world regions, countries were listed in alphabetical order; the correspondence was embedded in bound diplomatic and consular category archives, rather than by subject matter.][ Added to countries' information was a miscellaneous category filed chronologically.][ This resulted in a tedious and time-consuming process to make briefings for Congress.][ Diplomatic ministers, only 23 in 1877, were not kept informed of current world events that took place in other parts of the world.][

]

Cuban belligerency and insurrection 1869–1870

By 1869, Cuban nationals were in open rebellion against their mother country Spain, due to the unpopularity of Spanish rule. American sentiment favored the Cuban rebels and President Grant appeared to be on the verge of acknowledging Cuban belligerency. Fish, who desired settlement over the ''Alabama'' Claims, did not approve of recognizing the Cuban rebels, since Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until Death and state funeral of Queen Victoria, her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 21 ...

and her government had recognized Confederate belligerency in 1861. Recognizing Cuban belligerency would have jeopardized settlement and arbitration with Great Britain. In February 1870, Senator John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

authored a Senate resolution that would have recognized Cuban belligerency. Working behind the scenes Fish counseled Sherman that Cuban recognition would ultimately lead to war with Spain. The resolution went to the House of Representatives and was ready to pass, however, Fish worked out an agreement with President Grant to send a special message to Congress that urged not to acknowledge the Cuban rebels. On June 13, 1870, the message written by Fish was sent to Congress by the President and Congress, after much debate, decided not to recognize Cuban belligerency. President Grant continued the policy of Cuban belligerent non recognition for the rest of his two administrations. This policy, however, was tested in 1873 with the ''Virginius'' Affair.

Dominican Republic annexation treaty 1869–1870

After President Grant assumed office on March 4, 1869, one of his immediate foreign policy interests was the annexation of the Caribbean island nation of the Dominican Republic, at that time referred to as Santo Domingo, to the United States. President Grant believed the annexation of Santo Domingo would increase the United States' mineral resources and alleviate the effects of racism against African Americans in the South. Hamilton Fish, though loyal to President Grant, racially opposed annexation of Latin American countries, saying "the incorporation of those peopled by the Latin race would be but the beginnings of years of conflict and anarchy." The divided island nation, run by mulatto leader President Buenaventura Báez

Ramón Buenaventura Báez Méndez (July 14, 1812March 14, 1884), was a Dominican politician and military figure. He was president of the Dominican Republic for five nonconsecutive terms. His rule was characterized by being very corrupt and govern ...

, had been troubled with civil strife.Orville Babcock

Orville Elias Babcock (December 25, 1835 – June 2, 1884) was an American engineer and general in the Union Army during the Civil War. An aide to General Ulysses S. Grant during and after the war, he was President Grant's military private secret ...

"special agent" status to search the island.Samaná Bay

Samaná Bay is a bay in the eastern Dominican Republic. The Yuna River flows into Samaná Bay, and it is located south of the town of Samaná and the Samaná Peninsula.

Wildlife

Among its features are protected islands that serve as nesting site ...

would be leased to the United States for $150,000 yearly payment; Santo Domingo would eventually be given statehood.

In a private conference with President Grant, Fish agreed to support the Santo Domingo annexation if President Grant sent Congress a non-belligerency statement not to get involved with the Cuban rebellion against Spain. Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American statesman and United States Senator from Massachusetts. As an academic lawyer and a powerful orator, Sumner was the leader of the anti-slavery forces in the state and a leader of th ...

, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for overseeing and funding foreign aid pro ...

, was against the treaty, believing that Santo Domingo needed to remain independent, and that racism against U.S. black citizens in the South needed to be dealt with in the continental United States. Sumner believed that blacks on Santo Domingo did not share Anglo-American values. On January 10, 1870, Grant submitted the Santo Domingo treaty to the United States Senate. Fish believed Senators would vote for annexation only if statehood was withdrawn; however, President Grant refused this option.J. Lothrop Motley

John Lothrop Motley (April 15, 1814 – May 29, 1877) was an American author and diplomat. As a popular historian, he is best known for his works on the Netherlands, the three volume work ''The Rise of the Dutch Republic'' and four volume ''His ...

, Grant's ambassador to England, for disregarding Fish's instructions regarding the ''Alabama'' Claims. Grant believed that Sumner had in January 1870 stated his support for the Santo Domingo treaty. Sumner was then deprived of his chairmanship of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in 1871 by Grant's allies in the Senate.

Colombian inter-oceanic canal treaty 1870

President Grant and Secretary Fish were interested in establishing an inter-oceanic canal through Panama

Panama ( , ; es, link=no, Panamá ), officially the Republic of Panama ( es, República de Panamá), is a transcontinental country spanning the southern part of North America and the northern part of South America. It is bordered by Cos ...

.Colombia

Colombia (, ; ), officially the Republic of Colombia, is a country in South America with insular regions in North America—near Nicaragua's Caribbean coast—as well as in the Pacific Ocean. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Car ...

that established a Panama route for the inter-oceanic canal.[ The Colombian Senate, however, amended the treaty so much that the strategic value of the inter-oceanic canal construction became ineffective. As a result, the United States Senate refused to ratify the treaty.][

]

Treaty of Washington 1871

During the previous administration of President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, Secretary of State Seward attempted to resolve the ''Alabama'' Claims with the Johnson-Clarendon convention and treaty. The ''Alabama'' Claims had arisen out of the American Civil War, when Confederate raiding ships built in British ports (most notably the C.S.S. ''Alabama'') had sunk a significant number of Union merchant ships.

The Johnson-Clarendon treaty, presented to Congress by President Ulysses S. Grant, was overwhelmingly defeated by the Senate and the claims remained unresolved. Anglophobia led by Charles Sumner was at an all-time high when Fish became Secretary of State. Sumner had demanded Britain cede Canada to the United States as payment for the ''Alabama'' Claims. In late 1870, an opportunity arrived to settle the ''Alabama'' Claims under Prime Minister William Gladstone. Fish, who was determined to improve relations with Britain, along with President Grant and Senate supporters, had Charles Sumner removed by vote from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and the door was open for renewed negotiations with Britain.

On January 9, 1871, Fish met with British representative Sir John Rose in Washington and an agreement was made, after much negotiation, to establish a Joint Commission to settle the ''Alabama'' Claims to be held in Washington under the direction of Hamilton Fish. At stake was the financing of America's debt with British bankers during the Civil War, and peace with Britain was required. On February 14, 1871, both distinguished High Commissioners representing Britain, led by the Earl of Ripon, George Robinson, and the United States, led by Fish, met in Washington D.C. and negotiations over settlement went remarkably well. Also representing Britain was Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (January 10 or 11, 1815 – June 6, 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891. The dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, he had a political career that sp ...

. After 37 meetings, on May 8, 1871, the Treaty of Washington was signed at the State Department and became a "landmark of international conciliation". The Senate ratified the treaty on May 24, 1871. On August 25, 1872, the settlement for the ''Alabama'' claims was made by an international arbitration

Arbitration is a form of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) that resolves disputes outside the judiciary courts. The dispute will be decided by one or more persons (the 'arbitrators', 'arbiters' or 'arbitral tribunal'), which renders the ' ...

committee meeting in Geneva and the United States was awarded $15,500,000 in gold for damage done by the Confederate warships. Under the treaty settlement over disputed Atlantic fisheries and the San Juan Boundary (concerning the Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

boundary line) was made. The treaty was considered an "unprecedented accomplishment", having solved border disputes, reciprocal trade, and navigation issues. A friendly perpetual relationship between Great Britain and America was established, with Britain having expressed regret over the ''Alabama'' damages.

South American détente and armistice 1871

On April 11, 1871, a peace-trade conference, presided over by Hamilton Fish, was held in Washington D.C. between Spain and the South American republics of Peru

, image_flag = Flag of Peru.svg

, image_coat = Escudo nacional del Perú.svg

, other_symbol = Great Seal of the State

, other_symbol_type = Seal (emblem), National seal

, national_motto = "Fi ...

, Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in the western part of South America. It is the southernmost country in the world, and the closest to Antarctica, occupying a long and narrow strip of land between the Andes to the east a ...

, Ecuador

Ecuador ( ; ; Quechua: ''Ikwayur''; Shuar: ''Ecuador'' or ''Ekuatur''), officially the Republic of Ecuador ( es, República del Ecuador, which literally translates as "Republic of the Equator"; Quechua: ''Ikwadur Ripuwlika''; Shuar: ''Eku ...

, and Bolivia

, image_flag = Bandera de Bolivia (Estado).svg

, flag_alt = Horizontal tricolor (red, yellow, and green from top to bottom) with the coat of arms of Bolivia in the center

, flag_alt2 = 7 × 7 square p ...

, which resulted in an armistice between the countries.détente

Détente (, French: "relaxation") is the relaxation of strained relations, especially political ones, through verbal communication. The term, in diplomacy, originates from around 1912, when France and Germany tried unsuccessfully to reduc ...

meeting between the five countries. The signed armistice treaty consisted of seven articles; hostilities were to cease for a minimum of three years and the countries would allow commercial trade with neutral countries.

Korean expedition and conflict 1871

In 1871,

In 1871, Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

was known as the "Hermit Kingdom", a country determined to remain isolated from other nations, specifically from commerce and trade from Western nations, including the United States.[Nahne (April 1968), ''"Our Little War With The Heathen"''] In 1866, U.S. relations with Korea were troubled when Christian missionaries were beheaded by the Korean ''Daewongun

Heungseon Daewongun (흥선대원군, 興宣大院君, 21 December 1820 – 22 February 1898; ), also known as the Daewongun (대원군, 大院君), Guktaegong (국태공, 國太公, "The Great Archduke") or formally Internal King Heungseon Heon ...

'', regent to King Kojong, and the crew of the ''General Sherman'', a U.S. trading ship, were massacred.John Rodgers John Rodgers may refer to:

Military

* John Rodgers (1728–1791), colonel during the Revolutionary War and owner of Rodgers Tavern, Perryville, Maryland

* John Rodgers (naval officer, born 1772), U.S. naval officer during the War of 1812, first ...

, commander of the Asiatic Squadron, voyaged to Korea with five warships, eighty-five guns, and 1,230 sailors and marines.Hugh W. McKee

Hugh Wilson McKee (April 23, 1844 – June 11, 1871) was an American United States Navy, naval officer in the 1870s who participated in the United States expedition to Korea in 1871.

Early life and military service

McKee was born in Lexington, K ...

was the first U.S. Navy officer to die in battle in Korea.Matthew Perry

Matthew Langford Perry (born August 19, 1969) is an American-Canadian actor. He is best known for his role as Chandler Bing on the NBC television sitcom ''Friends'' (1994–2004).

As well as starring in the short-lived television series ''Stud ...

in 1854 had approached the opening of Japan. Korea, however, proved to be more isolated than Japan. In 1881, Commodore Robert W. Shufeldt, without using a naval fleet, went to a more conciliatory Korean government and made a commercial treaty. The U.S. was the first Western nation to establish formal trade with Korea.

''Virginius'' affair 1873

During the 1870s,

During the 1870s, Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribbea ...

was in a state of rebellion against Spain. In the United States, Americans were divided on whether to militarily aid the rebel Cubans. Many jingoists believed the United States needed to fight for the Cuban rebels and pressured the Grant Administration to take action.Morant Bay

Morant Bay is a town in southeastern Jamaica and the capital of the parish of St. Thomas, located about 25 miles east of Kingston, the capital. The parish has a population of 94,410.

During the nineteenth century, the parish was an area of sug ...

, Jamaica.

Hawaiian reciprocal trade treaty 1875

Fish also negotiated the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875

The Treaty of reciprocity between the United States of America and the Hawaiian Kingdom ( Hawaiian: ''Kuʻikahi Pānaʻi Like'') was a free trade agreement signed and ratified in 1875 that is generally known as the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875.

T ...

with the Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, or Kingdom of Hawaiʻi ( Hawaiian: ''Ko Hawaiʻi Pae ʻĀina''), was a sovereign state located in the Hawaiian Islands. The country was formed in 1795, when the warrior chief Kamehameha the Great, of the independent island ...

under the reign of King Kalākaua

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the ti ...

. Hawaiian sugar was made duty-free, while the importation of manufactured goods and clothing was allowed into the island kingdom. By opening Hawaii to free trade the process for annexation and eventual statehood into the United States had begun.

Liberian-Grebo war 1876

The U.S. settled the Liberian- Grebo war in 1876 when Hamilton Fish dispatched the USS ''Alaska'', under President Grant's authority, to Liberia

Liberia (), officially the Republic of Liberia, is a country on the West African coast. It is bordered by Sierra Leone to Liberia–Sierra Leone border, its northwest, Guinea to its north, Ivory Coast to its east, and the Atlantic Ocean ...

. Liberia was in practice an American colony. U.S. envoy James Milton Turner

James Milton Turner (1840 – November 1, 1915) was a Reconstruction Era political leader, activist, educator, and diplomat. As consul general to Liberia, he was the first African-American to serve in the U.S. diplomatic corps.

Early life

Turn ...

, the first African American ambassador, requested a warship to protect American property in Liberia. Turner, bolstered by U.S. naval presence in harbor and support of the USS ''Alaska'' captain, negotiated the incorporation of Grebo people into Liberian society and the ousting of foreign traders from Liberia.

Republican convention 1876

As the 1876 Republican convention approached during the U.S. Presidential Election, President Grant, unknown to Fish, had written a letter to Republican leaders to nominate Fish for the Presidential ticket. The letter was never read at the convention and Fish was never nominated. President Grant believed that Fish was a good compromise choice between the rival factions of James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

. Cartoonist Thomas Nast

Thomas Nast (; ; September 26, 1840December 7, 1902) was a German-born American caricaturist and editorial cartoonist often considered to be the "Father of the American Cartoon".

He was a critic of Democratic Party (United States), Democratic U ...

drew a caricature of Fish and Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford Birchard Hayes (; October 4, 1822 – January 17, 1893) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 19th president of the United States from 1877 to 1881, after serving in the U.S. House of Representatives and as governor ...

as the Republican Party ticket. Fish, who was ready to retire to private life, did not desire to run for president and was content at returning to private life. Fish found out later President Grant had written the letter to the convention.

Nicaragua inter-oceanic canal negotiations 1877

President Grant at the close of his second term, and Secretary Fish, remained interested in establishing an inter-oceanic canal treaty.[ Fish and the State Department negotiated with a special envoy from ]Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

in February 1877 for an inter-oceanic treaty.[ Negotiations, however, failed as the status of the neutral zone could not be established.][

]

Later life and health

After leaving the Grant Cabinet in 1877 and briefly serving under President Hayes, Fish retired from public office and returned to private life practicing law and managing his real estate in New York City. Fish was revered in the New York community and enjoyed spending time with his family.

Fish resided in Glen Clyffe, his estate near

After leaving the Grant Cabinet in 1877 and briefly serving under President Hayes, Fish retired from public office and returned to private life practicing law and managing his real estate in New York City. Fish was revered in the New York community and enjoyed spending time with his family.

Fish resided in Glen Clyffe, his estate near Garrison, New York

Garrison is a hamlet in Putnam County, New York, United States. It is part of the town of Philipstown, on the east side of the Hudson River, across from the United States Military Academy at West Point. The Garrison Metro-North Railroad ...

, in Putnam County, New York

Putnam County is a county located in the U.S. state of New York. As of the 2020 census, the population was 97,668. The county seat is Carmel. Putnam County formed in 1812 from Dutchess County and is named for Israel Putnam, a hero in the ...

, in the Hudson River Valley

The Hudson Valley (also known as the Hudson River Valley) comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York. The region stretches from the Capital District including Albany and Troy south to Yo ...

. His health remained good until around 1884, having suffered from neuralgia

Neuralgia (Greek ''neuron'', "nerve" + ''algos'', "pain") is pain in the distribution of one or more nerves, as in intercostal neuralgia, trigeminal neuralgia, and glossopharyngeal neuralgia.

Classification

Under the general heading of neuralg ...

.

Death, funeral, and burial

On September 6, 1893, Fish had retired from the evening having played cards with his daughter. The following morning on September 7, Fish, at the age of 85, suddenly died. His death was attributed to advanced age.

On September 11, 1893, Fish was buried in Garrison at St. Philip's Church-in-the-Highlands Cemetery under waving trees on the hills along the Hudson River shoreline. He was buried next to his wife and oldest daughter. Fish was buried near the grave of Edwards Pierrepont

Edwards Pierrepont (March 4, 1817 – March 6, 1892) was an American attorney, reformer, jurist, traveler, New York U.S. Attorney, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Minister to England, and orator.''West's Encyclopedia of American Law'' (2005), "Pierre ...

, President Grant's U.S. Attorney General. Many notable persons attended Fish's funeral, while Bishop Potter conducted services. Julia Grant

Julia Boggs Grant (née Dent; January 26, 1826 – December 14, 1902) was the first lady of the United States and wife of President Ulysses S. Grant. As first lady, she became a national figure in her own right. Her memoirs, '' The Personal Memo ...

, widowed wife of Ulysses S. Grant, attended Fish's funeral.

Historical reputation

Charles Francis Adams described Fish as "a quiet and easy-going man; but, when aroused, by being, as he thought, 'put upon', he became very formidable. Neither was it possible to placate him." Fish's 20th Century biographer, A. Elwood Corning, stated that Fish was free from "petty jealousies and prejudices which so often drag the reputation of statesmen down to the level of politicians" and that Fish "used the language and practiced the manners of a gentleman." As an invaluable member of the Grant Administration, Fish commanded "men's confidence, and respect by his firmness, candor, and justice."

A survey of scholars in the December 1981 American Heritage Magazine ranked Fish number 3 on a list of top ten Secretary of States noting his settling of the ''Alabama'' Claims in 1871, for his peaceful settlement of the ''Virginius'' Incident obtaining Spanish reparations, and for his Hawaiian treaty, ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1875, starting the annexation process leading to the eventual statehood of Hawaii.

Charles Francis Adams described Fish as "a quiet and easy-going man; but, when aroused, by being, as he thought, 'put upon', he became very formidable. Neither was it possible to placate him." Fish's 20th Century biographer, A. Elwood Corning, stated that Fish was free from "petty jealousies and prejudices which so often drag the reputation of statesmen down to the level of politicians" and that Fish "used the language and practiced the manners of a gentleman." As an invaluable member of the Grant Administration, Fish commanded "men's confidence, and respect by his firmness, candor, and justice."

A survey of scholars in the December 1981 American Heritage Magazine ranked Fish number 3 on a list of top ten Secretary of States noting his settling of the ''Alabama'' Claims in 1871, for his peaceful settlement of the ''Virginius'' Incident obtaining Spanish reparations, and for his Hawaiian treaty, ratified by the U.S. Senate in 1875, starting the annexation process leading to the eventual statehood of Hawaii.Cathedral of All Saints (Albany, New York)

The Cathedral of All Saints, Albany, New York, is located on Elk Street in central Albany, New York, United States. It is the central church of the Episcopal Diocese of Albany and the seat of the Episcopal Bishop of Albany. Built in the 1880s ...

. The Hamilton Fish Newburgh-Beacon Bridge, which spans the Hudson River 50 miles north of New York City between Dutchess

Dutchess County is a County (United States), county in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population was 295,911. The county seat is the city of Poughkeepsie, New York, Poughkeeps ...

and Orange

Orange most often refers to:

*Orange (fruit), the fruit of the tree species '' Citrus'' × ''sinensis''

** Orange blossom, its fragrant flower

*Orange (colour), from the color of an orange, occurs between red and yellow in the visible spectrum

* ...

Counties, is named after Fish.

Society of Cincinnati

Fish was a long time member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of military officers wh ...

by right of his father's service as an officer in the Continental Army. Fish succeeded to his father's "seat" in the Society upon his father's death in 1833. In 1848, Fish became the Vice President General of the national Society and, in 1854, he became its President General. In 1855 Fish was elected President of the New York Society. Fish served as both President General of the national Society and President of the New York Society until his death in 1893. His 39-year tenure in office as President General is by far the longest in the Society's history.

Notable descendants

150px, Hamilton Fish II

Three of Fish's direct descendants, all named Hamilton, served in the U.S. House of Representatives for the state of New York. Hamilton Fish II

Hamilton Fish II (April 17, 1849 – January 15, 1936) was an American lawyer and politician who served as Speaker of the New York State Assembly and a member of the United States House of Representatives.

Early life

Fish was born in Albany, Ne ...

, Fish's son, served one term as U.S. Representative from 1909 to 1911. Fish II also served as assistant to Secretary of State Hamilton Fish. Hamilton Fish III

Hamilton Fish III (born Hamilton Stuyvesant Fish and also known as Hamilton Fish Jr.; December 7, 1888 – January 18, 1991) was an American soldier and politician from New York State. Born into a family long active in the state, he served in t ...

, Fish's grandson, served as U.S. Representative from 1920 to 1945. Hamilton Fish IV, Fish's great-grandson, served as U.S. Representative from 1969 to 1995. Another son Stuyvesant Fish

Stuyvesant Fish (June 24, 1851 – April 10, 1923) was an American businessman and member of the Fish family who served as president of the Illinois Central Railroad. He owned grand residences in New York City and Newport, Rhode Island, entertain ...

was an important railroad executive. Another son, Nicholas Fish II

Nicholas Fish II (February 19, 1846–September 16, 1902) was a United States diplomat who served as the ambassador to Switzerland from 1877 to 1881 and the ambassador to Belgium from 1882 to 1885. In a widely reported crime of the time know ...

, was a U.S. diplomat, who was appointed second secretary of legation at Berlin in 1871, became secretary in 1874, and was chargé d'affaires at Berne

german: Berner(in)french: Bernois(e) it, bernese

, neighboring_municipalities = Bremgarten bei Bern, Frauenkappelen, Ittigen, Kirchlindach, Köniz, Mühleberg, Muri bei Bern, Neuenegg, Ostermundigen, Wohlen bei Bern, Zollikofen

, website ...

in 1877–1881, and minister to Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to th ...

in 1882–1886, after which he engaged in banking in New York City. Hamilton Fish

Hamilton Fish (August 3, 1808September 7, 1893) was an American politician who served as the 16th Governor of New York from 1849 to 1850, a United States Senator from New York from 1851 to 1857 and the 26th United States Secretary of State fro ...

, Fish's grandson by Nicholas, was an 1895 graduate of Columbia College, saw service in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

as one of the storied Rough Riders

The Rough Riders was a nickname given to the 1st United States Volunteer Cavalry, one of three such regiments raised in 1898 for the Spanish–American War and the only one to see combat. The United States Army was small, understaffed, and diso ...

. He was the first member of that regiment to be killed in action, at the Battle of Las Guasimas

The Battle of Las Guasimas of June 24, 1898 was a Spanish rearguard action by Major General Antero Rubín against advancing columns led by Major General "Fighting Joe" Wheeler and the first land engagement of the Spanish–American War. The ba ...

, Cuba.

References

Sources

Books

* scholarly review and response by Calhoun at

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Journals and newspapers

American Heritage

*

*

*

New York Times

*

*

Internet

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Archives

*

*

External links

U-S-History.com: Article

Desmond-Fish Library

Public Library co-founded by Hamilton Fish IV. Library has many Fish family artifacts, papers and portraits on display.

Contains many online documents on the Fish Family.

*

, -

, -

, -

, -

, -

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fish, Hamilton

1808 births

1893 deaths

19th-century American Episcopalians

American people of English descent

Columbia College (New York) alumni

Hamilton Hamilton may refer to:

People

* Hamilton (name), a common British surname and occasional given name, usually of Scottish origin, including a list of persons with the surname

** The Duke of Hamilton, the premier peer of Scotland

** Lord Hamilt ...

Governors of New York (state)

Grant administration cabinet members

Lieutenant Governors of New York (state)

Livingston family

New York (state) Republicans

People of New York (state) in the American Civil War

Schuyler family

Winthrop family

Woodhull family

United States Secretaries of State

United States senators from New York (state)

Whig Party United States senators

American people of Dutch descent

Whig Party members of the United States House of Representatives from New York (state)

Whig Party state governors of the United States

19th-century American politicians

Presidents of the Saint Nicholas Society of the City of New York

Presidents of the New York Public Library

In the

In the

In 1871,

In 1871,  During the 1870s,

During the 1870s,  After leaving the Grant Cabinet in 1877 and briefly serving under President Hayes, Fish retired from public office and returned to private life practicing law and managing his real estate in New York City. Fish was revered in the New York community and enjoyed spending time with his family.

Fish resided in Glen Clyffe, his estate near

After leaving the Grant Cabinet in 1877 and briefly serving under President Hayes, Fish retired from public office and returned to private life practicing law and managing his real estate in New York City. Fish was revered in the New York community and enjoyed spending time with his family.

Fish resided in Glen Clyffe, his estate near