Hagia Sophia ( '

Holy Wisdom

Holy Wisdom (Greek: , la, Sancta Sapientia, russian: Святая София Премудрость Божия, translit=Svyataya Sofiya Premudrost' Bozhiya "Holy Sophia, Divine Wisdom") is a concept in Christian theology.

Christian theology ...

'; ; ; ), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque ( tr, Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i Şerifi),

is a

mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

and major cultural and historical site in

Istanbul

)

, postal_code_type = Postal code

, postal_code = 34000 to 34990

, area_code = +90 212 (European side) +90 216 (Asian side)

, registration_plate = 34

, blank_name_sec2 = GeoTLD

, blank_i ...

,

Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with a small portion on the Balkan Peninsula ...

. The cathedral was originally built as a

Greek Orthodox church

The term Greek Orthodox Church ( Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also cal ...

which lasted from 360 AD until the

conquest

Conquest is the act of military subjugation of an enemy by force of arms.

Military history provides many examples of conquest: the Roman conquest of Britain, the Mauryan conquest of Afghanistan and of vast areas of the Indian subcontinent, ...

of

Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis (" ...

by the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

in 1453. It served as a mosque until 1935, when it became a museum. In 2020, the site once again became a mosque.

The current structure was built by the eastern

Roman emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

as the Christian

cathedral

A cathedral is a church that contains the ''cathedra'' () of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually specific to those Christian denominations ...

of Constantinople for the

state church of the Roman Empire

Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire when Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica in 380, which recognized the catholic orthodoxy of Nicene Christians in the Great Church as the Roman Empire's state religion ...

between 532 and 537, and was designed by the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

geometers

Isidore of Miletus

Isidore of Miletus ( el, Ἰσίδωρος ὁ Μιλήσιος; Medieval Greek pronunciation: ; la, Isidorus Miletus) was one of the two main Byzantine Greek architects (Anthemius of Tralles was the other) that Emperor Justinian I commissioned ...

and

Anthemius of Tralles

Anthemius of Tralles ( grc-gre, Ἀνθέμιος ὁ Τραλλιανός, Medieval Greek: , ''Anthémios o Trallianós''; – 533 558) was a Greek from Tralles who worked as a geometer and architect in Constantinople, the ca ...

. It was formally called the Church of the Holy Wisdom ()

and upon completion became the world's largest interior space and among

the first to employ a fully

pendentive

In architecture, a pendentive is a constructional device permitting the placing of a circular dome over a square room or of an elliptical dome over a rectangular room. The pendentives, which are triangular segments of a sphere, taper to point ...

dome. It is considered the epitome of

Byzantine architecture

Byzantine architecture is the architecture of the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire.

The Byzantine era is usually dated from 330 AD, when Constantine the Great moved the Roman capital to Byzantium, which became Constantinople, until t ...

and is said to have "changed the history of architecture".

The present Justinianic building was the third church of the same name to occupy the site, as the prior one had been destroyed in the

Nika riots. As the

episcopal see

An episcopal see is, in a practical use of the phrase, the area of a bishop's ecclesiastical jurisdiction.

Phrases concerning actions occurring within or outside an episcopal see are indicative of the geographical significance of the term, mak ...

of the

ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople ( Istanbul), New Rome and '' primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of ...

, it remained the world's largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years, until

Seville Cathedral

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See ( es, Catedral de Santa María de la Sede), better known as Seville Cathedral, is a Roman Catholic cathedral in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along ...

was completed in 1520. Beginning with subsequent

Byzantine architecture

Byzantine architecture is the architecture of the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire.

The Byzantine era is usually dated from 330 AD, when Constantine the Great moved the Roman capital to Byzantium, which became Constantinople, until t ...

, Hagia Sophia became the paradigmatic

Orthodox church form, and its architectural style was emulated by

Ottoman mosques

Ottoman is the Turkish spelling of the Arabic masculine given name Uthman ( ar, عُثْمان, ‘uthmān). It may refer to:

Governments and dynasties

* Ottoman Caliphate, an Islamic caliphate from 1517 to 1924

* Ottoman Empire, in existence f ...

a thousand years later.

It has been described as "holding a unique position in the

Christian world

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

"

and as an architectural and

cultural icon

A cultural icon is a person or an artifact that is identified by members of a culture as representative of that culture. The process of identification is subjective, and "icons" are judged by the extent to which they can be seen as an authentic ...

of

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

and

Eastern Orthodox civilization.

[.]

The religious and spiritual centre of the

Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops via ...

for nearly one thousand years, the church was

dedicated to the

Holy Wisdom

Holy Wisdom (Greek: , la, Sancta Sapientia, russian: Святая София Премудрость Божия, translit=Svyataya Sofiya Premudrost' Bozhiya "Holy Sophia, Divine Wisdom") is a concept in Christian theology.

Christian theology ...

.

[Janin (1953), p. 471.] It was where the

excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to end or at least regulate the communion of a member of a congregation with other members of the religious institution who are in normal communion with each other. The purpose ...

of Patriarch

Michael I Cerularius

Michael I Cerularius or Keroularios ( el, Μιχαήλ Α΄ Κηρουλάριος; 1000 – 21 January 1059 AD) was the Patriarch of Constantinople from 1043 to 1059 AD. His disputes with Pope Leo IX over church practices in the 11th century p ...

was officially delivered by

Humbert of Silva Candida

Humbert of Silva Candida, O.S.B., also known as Humbert of Moyenmoutier (between 1000 and 1015 – 5 May 1061), was a French Benedictine abbot and later a cardinal. It was his act of excommunicating the Patriarch of Constantinople Michael I Cer ...

, the envoy of

Pope Leo IX

Pope Leo IX (21 June 1002 – 19 April 1054), born Bruno von Egisheim-Dagsburg, was the head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 12 February 1049 to his death in 1054. Leo IX is considered to be one of the most historically ...

in 1054, an act considered the start of the

East–West Schism

The East–West Schism (also known as the Great Schism or Schism of 1054) is the ongoing break of communion between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches since 1054. It is estimated that, immediately after the schism occurred, a ...

. In 1204, it was converted during the

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

into a Catholic cathedral under the

Latin Empire

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byza ...

, before being returned to the Eastern Orthodox Church upon the restoration of the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

in 1261. The

doge of Venice

The Doge of Venice ( ; vec, Doxe de Venexia ; it, Doge di Venezia ; all derived from Latin ', "military leader"), sometimes translated as Duke (compare the Italian '), was the chief magistrate and leader of the Republic of Venice between 726 ...

who led the

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

and the 1204

Sack of Constantinople

The sack of Constantinople occurred in April 1204 and marked the culmination of the Fourth Crusade. Crusader armies captured, looted, and destroyed parts of Constantinople, then the capital of the Byzantine Empire. After the capture of the ...

,

Enrico Dandolo

Enrico Dandolo (anglicised as Henry Dandolo and Latinized as Henricus Dandulus; c. 1107 – May/June 1205) was the Doge of Venice from 1192 until his death. He is remembered for his avowed piety, longevity, and shrewdness, and is known for his r ...

, was buried in the church.

After the

Fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city fell on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 53-day siege which had begun o ...

to the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University ...

in 1453,

[Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 112.] it was

converted to a mosque by

Mehmed the Conqueror

Mehmed II ( ota, محمد ثانى, translit=Meḥmed-i s̱ānī; tr, II. Mehmed, ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror ( ota, ابو الفتح, Ebū'l-fetḥ, lit=the Father of Conquest, links=no; tr, Fâtih Su ...

and became the

principal mosque of Istanbul until the 1616 construction of the

Sultan Ahmed Mosque

The Blue Mosque in Istanbul, also known by its official name, the Sultan Ahmed Mosque ( tr, Sultan Ahmet Camii), is an Ottoman-era historical imperial mosque located in Istanbul, Turkey. A functioning mosque, it also attracts large numbers ...

.

[Hagia Sophia]

." ArchNet. Upon its conversion, the

bells

Bells may refer to:

* Bell, a musical instrument

Places

* Bells, North Carolina

* Bells, Tennessee

* Bells, Texas

* Bells Beach, Victoria, an internationally famous surf beach in Australia

* Bells Corners, Ontario

Music

* Bells, directly st ...

,

altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, churches, and other places of worship. They are used particularly in pagan ...

,

iconostasis

In Eastern Christianity, an iconostasis ( gr, εἰκονοστάσιον) is a wall of icons and religious paintings, separating the nave from the sanctuary in a church. ''Iconostasis'' also refers to a portable icon stand that can be placed a ...

,

ambo, and

baptistery

In Christian architecture the baptistery or baptistry (Old French ''baptisterie''; Latin ''baptisterium''; Greek , 'bathing-place, baptistery', from , baptízein, 'to baptize') is the separate centrally planned structure surrounding the baptism ...

were removed, while

iconography

Iconography, as a branch of art history, studies the identification, description and interpretation of the content of images: the subjects depicted, the particular compositions and details used to do so, and other elements that are distinct fro ...

, such as the

mosaic

A mosaic is a pattern or image made of small regular or irregular pieces of colored stone, glass or ceramic, held in place by plaster/mortar, and covering a surface. Mosaics are often used as floor and wall decoration, and were particularly pop ...

depictions of Jesus,

Mary

Mary may refer to:

People

* Mary (name), a feminine given name (includes a list of people with the name)

Religious contexts

* New Testament people named Mary, overview article linking to many of those below

* Mary, mother of Jesus, also calle ...

,

Christian saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Ort ...

and

angel

In various theistic religious traditions an angel is a supernatural spiritual being who serves God.

Abrahamic religions often depict angels as benevolent celestial intermediaries between God (or Heaven) and humanity. Other roles ...

s were removed or plastered over.

[Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 91.] Islamic architectural additions included four

minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

s, a

minbar

A minbar (; sometimes romanized as ''mimber'') is a pulpit in a mosque where the imam (leader of prayers) stands to deliver sermons (, '' khutbah''). It is also used in other similar contexts, such as in a Hussainiya where the speaker sits a ...

and a

mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla ...

. The Byzantine architecture of the Hagia Sophia served as inspiration for many other religious buildings including the

Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki,

Panagia Ekatontapiliani

Panagia Ekatontapiliani (literally ''the church with 100 doors'') or Panagia Katapoliani is a historic Byzantine church complex in Parikia town, on the island of Paros in Greece. The church complex contains a main chapel surrounded by two more ...

, the

Şehzade Mosque

The Şehzade Mosque ( tr, Şehzade Camii, from the original Persian شاهزاده ''Šāhzādeh'', meaning "prince") is a 16th-century Ottoman imperial mosque located in the district of Fatih, on the third hill of Istanbul, Turkey. It was com ...

, the

Süleymaniye Mosque

The Süleymaniye Mosque ( tr, Süleymaniye Camii, ) is an Ottoman imperial mosque located on the Third Hill of Istanbul, Turkey. The mosque was commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent and designed by the imperial architect Mimar Sinan. An ...

, the

Rüstem Pasha Mosque and the

Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex. The patriarchate moved to the

Church of the Holy Apostles

The Church of the Holy Apostles ( el, , ''Agioi Apostoloi''; tr, Havariyyun Kilisesi), also known as the ''Imperial Polyándreion'' (imperial cemetery), was a Byzantine Eastern Orthodox church in Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman E ...

, which became the city's cathedral.

The complex remained a mosque until 1931, when it was closed to the public for four years. It was re-opened in 1935 as a museum under the

secular

Secularity, also the secular or secularness (from Latin ''saeculum'', "worldly" or "of a generation"), is the state of being unrelated or neutral in regards to religion. Anything that does not have an explicit reference to religion, either negativ ...

Republic of Turkey, and the building is Turkey's most visited tourist attraction .

In July 2020, the

Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

annulled the 1934 decision to establish the museum, and the Hagia Sophia was reclassified as a mosque. The 1934 decree was ruled to be unlawful under both Ottoman and Turkish law as Hagia Sophia's ''

waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or '' mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitab ...

'', endowed by Sultan Mehmed, had designated the site a mosque; proponents of the decision argued the Hagia Sophia was the personal property of the sultan. This redesignation drew condemnation from the Turkish opposition,

UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a List of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international coope ...

, the

World Council of Churches

The World Council of Churches (WCC) is a worldwide Christian inter-church organization founded in 1948 to work for the cause of ecumenism. Its full members today include the Assyrian Church of the East, the Oriental Orthodox Churches, most ju ...

, the

International Association of Byzantine Studies International Association of Byzantine Studies (french: Association Internationale des Études Byzantines, AIEB) was launched in 1948. It is an international co-ordinating body that links national Byzantine Studies member groups.

Background and A ...

, and many international leaders.

History

Church of Constantius II

The first church on the site was known as the ()

[Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 84.] because of its size compared to the sizes of the contemporary churches in the city.

According to the ''

Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

'', the church was

consecrated

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service. The word ''consecration'' literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different gro ...

on 15 February 360, during the reign of the emperor

Constantius II

Constantius II (Latin: ''Flavius Julius Constantius''; grc-gre, Κωνστάντιος; 7 August 317 – 3 November 361) was Roman emperor from 337 to 361. His reign saw constant warfare on the borders against the Sasanian Empire and Germanic ...

() by the

Arian

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by God ...

bishop

Eudoxius of Antioch

Eudoxius (Ευδόξιος; died 370) was the eighth bishop of Constantinople from January 27, 360 to 370, previously bishop of Germanicia and of Antioch. Eudoxius was one of the most influential Arianism, Arians.

Biography

Eudoxius was from Ara ...

.

[Janin (1953), p. 472.] It was built next to the area where the

Great Palace was being developed. According to the 5th-century ecclesiastical historian

Socrates of Constantinople

Socrates of Constantinople ( 380 – after 439), also known as Socrates Scholasticus ( grc-gre, Σωκράτης ὁ Σχολαστικός), was a 5th-century Greek Christian church historian, a contemporary of Sozomen and Theodoret.

He is the ...

, the emperor Constantius had "constructed the Great Church alongside that called Irene which because it was too small, the emperor's father

onstantinehad enlarged and beautified".

A tradition which is not older than the 7th or 8th century reports that the edifice was built by Constantius' father,

Constantine the Great

Constantine I ( , ; la, Flavius Valerius Constantinus, ; ; 27 February 22 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337, the first one to convert to Christianity. Born in Naissus, Dacia Mediterran ...

().

Hesychius of Miletus

Hesychius of Miletus ( el, Ἡσύχιος ὁ Μιλήσιος, translit=Hesychios o Milesios), Greek chronicler and biographer, surnamed Illustrius, son of an advocate, lived in Constantinople in the 6th century AD during the reign of Justinian ...

wrote that Constantine built Hagia Sophia with a wooden roof and removed 427 (mostly pagan) statues from the site. The 12th-century chronicler

Joannes Zonaras

Joannes or John Zonaras ( grc-gre, Ἰωάννης Ζωναρᾶς ; 1070 – 1140) was a Byzantine Greek historian, chronicler and theologian who lived in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). Under Emperor Alexios I Komnenos he hel ...

reconciles the two opinions, writing that Constantius had repaired the edifice consecrated by

Eusebius of Nicomedia

Eusebius of Nicomedia (; grc-gre, Εὐσέβιος; died 341) was an Arian priest who baptized Constantine the Great on his deathbed in 337. A fifth-century legend evolved that Pope Saint Sylvester I was the one to baptize Constantine, but thi ...

, after it had collapsed.

Since Eusebius was the

bishop

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ...

of Constantinople from 339 to 341, and Constantine died in 337, it seems that the first church was erected by Constantius.

The nearby

Hagia Irene

Hagia Irene ( el, Αγία Ειρήνη) or Hagia Eirene ( grc-x-byzant, Ἁγία Εἰρήνη , "Holy Peace", tr, Aya İrini), sometimes known also as Saint Irene, is an Eastern Orthodox church located in the outer courtyard of Topkapı Palac ...

("Holy Peace") church was completed earlier and served as cathedral until the Great Church was completed. Besides Hagia Irene, there is no record of major churches in the city-centre before the late 4th century.

Rowland Mainstone argued the 4th-century church was not yet known as Hagia Sophia. Though its name as the 'Great Church' implies that it was larger than other Constantinopolitan churches, the only other major churches of the 4th century were the

Church of St Mocius

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* Chri ...

, which lay outside the Constantinian walls and was perhaps attached to a cemetery, and the

Church of the Holy Apostles

The Church of the Holy Apostles ( el, , ''Agioi Apostoloi''; tr, Havariyyun Kilisesi), also known as the ''Imperial Polyándreion'' (imperial cemetery), was a Byzantine Eastern Orthodox church in Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman E ...

.

The church itself is known to have had a timber roof, curtains, columns, and an entrance that faced west.

It likely had a

narthex

The narthex is an architectural element typical of early Christian and Byzantine basilicas and churches consisting of the entrance or lobby area, located at the west end of the nave, opposite the church's main altar. Traditionally the narth ...

and is described as being shaped like a

Roman circus

The Roman circus (from the Latin word that means "circle") was a large open-air venue used for public events in the ancient Roman Empire. The circuses were similar to the ancient Greek hippodromes, although circuses served varying purposes and di ...

. This may mean that it had a U-shaped plan like the basilicas of

San Marcellino e Pietro and

Sant'Agnese fuori le mura

The church of Saint Agnes Outside the Walls ( it, Sant'Agnese fuori le mura) is a titulus church, minor basilica in Rome, on a site sloping down from the Via Nomentana, which runs north-east out of the city, still under its ancient name. Wha ...

in

Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

.

However, it may also have been a more conventional three-, four-, or five-aisled basilica, perhaps resembling the original

Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, hy, Սուրբ Հարության տաճար, la, Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri, am, የቅዱስ መቃብር ቤተክርስቲያን, he, כנסיית הקבר, ar, كنيسة القيامة is a church i ...

in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem (; he, יְרוּשָׁלַיִם ; ar, القُدس ) (combining the Biblical and common usage Arabic names); grc, Ἱερουσαλήμ/Ἰεροσόλυμα, Hierousalḗm/Hierosóluma; hy, Երուսաղեմ, Erusałēm. i ...

or the

Church of the Nativity

The Church of the Nativity, or Basilica of the Nativity,; ar, كَنِيسَةُ ٱلْمَهْد; el, Βασιλική της Γεννήσεως; hy, Սուրբ Ծննդեան տաճար; la, Basilica Nativitatis is a basilica located in B ...

in

Bethlehem

Bethlehem (; ar, بيت لحم ; he, בֵּית לֶחֶם '' '') is a city in the central West Bank, Palestine, about south of Jerusalem. Its population is approximately 25,000,Amara, 1999p. 18.Brynen, 2000p. 202. and it is the capital ...

.

The building was likely preceded by an

atrium, as in the later churches on the site.

According to

Ken Dark

Ken Dark (born in Brixton, London in 1961) is a British archaeologist who works on the 1st millennium AD in Europe (including Roman and immediately post-Roman Britain) and the Roman and Byzantine Middle East, on the archaeology of religion (esp ...

and Jan Kostenec, a further remnant of the 4th century basilica may exist in a wall of alternating brick and stone banded masonry immediately to the west of the Justinianic church.

The top part of the wall is constructed with bricks stamped with brick-stamps dating from the 5th century, but the lower part is of constructed with bricks typical of the 4th century.

This wall was probably part of the

propylaeum at the west front of both the Constantinian and Theodosian Great Churches.

The building was accompanied by a

baptistery

In Christian architecture the baptistery or baptistry (Old French ''baptisterie''; Latin ''baptisterium''; Greek , 'bathing-place, baptistery', from , baptízein, 'to baptize') is the separate centrally planned structure surrounding the baptism ...

and a ''

skeuophylakion''.

A

hypogeum

A hypogeum or hypogaeum (plural hypogea or hypogaea, pronounced ; literally meaning "underground", from Greek ''hypo'' (under) and ''ghê'' (earth)) is an underground temple or tomb.

Hypogea will often contain niches for cremated human r ...

, perhaps with an

martyrium

A martyrium (Latin) or martyrion ( Greek), plural ''martyria'', sometimes anglicized martyry (pl. martyries), is a church or shrine built over the tomb of a Christian martyr. It is associated with a specific architectural form, centered on a cen ...

above it, was discovered before 1946, and the remnants of a brick wall with traces of marble revetment were identified in 2004.

The hypogeum was a tomb which may have been part of the 4th-century church or may have been from the pre-Constantinian city of

Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion ( grc, Βυζάντιον) was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium' ...

.

The ''skeuophylakion'' is said by

Palladius to have had a circular floor plan, and since some U-shaped basilicas in Rome were funerary churches with attached circular mausolea (the

Mausoleum of Constantina and the

Mausoleum of Helena

The Mausoleum of Helena is an ancient building in Rome, Italy, located on the Via Casilina, corresponding to the 3rd mile of the ancient Via Labicana. It was built by the Roman emperor Constantine I between 326 and 330, originally as a tomb for ...

), it is possible it originally had a funerary function, though by 405 its use had changed.

A later account credited a woman called Anna with donating the land on which the church was built in return for the right to be buried there.

Excavations on the western side of the site of the first church under the propylaeum wall reveal that the first church was built atop a road about wide.

According to early accounts, the first Hagia Sophia was built on the site of an ancient pagan temple, although there are no artefacts to confirm this.

The Patriarch of Constantinople

John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of ...

came into a conflict with Empress

Aelia Eudoxia

Aelia Eudoxia (; ; died 6 October 404) was a Roman empress consort by marriage to the Roman emperor Arcadius. The marriage was the source of some controversy, as it was arranged by Eutropius, one of the eunuch court officials, who was attempt ...

, wife of the emperor

Arcadius

Arcadius ( grc-gre, Ἀρκάδιος ; 377 – 1 May 408) was Roman emperor from 383 to 408. He was the eldest son of the ''Augustus'' Theodosius I () and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and the brother of Honorius (). Arcadius ruled the ...

(), and was sent into exile on 20 June 404. During the subsequent riots, this first church was largely burnt down.

Palladius noted that the 4th-century ''skeuophylakion'' survived the fire.

According to Dark and Kostenec, the fire may only have affected the main basilica, leaving the surrounding ancillary buildings intact.

Church of Theodosius II

A second church on the site was ordered by

Theodosius II

Theodosius II ( grc-gre, Θεοδόσιος, Theodosios; 10 April 401 – 28 July 450) was Roman emperor for most of his life, proclaimed ''augustus'' as an infant in 402 and ruling as the eastern Empire's sole emperor after the death of his ...

(), who inaugurated it on 10 October 415. The ''

Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae

The ''Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae'' is an ancient "regionary", i.e., a list of monuments, public buildings and civil officials in Constantinople during the mid-5th century (between 425 and the 440s), during the reign of the emperor Theodosi ...

,'' a fifth-century list of monuments, names Hagia Sophia as , while the former cathedral Hagia Irene is referred to as . At the time of Socrates of Constantinople around 440, "both churches

ereenclosed by a single wall and served by the same clergy".

Thus, the complex would have encompassed a large area including the future site of the

Hospital of Samson.

If the fire of 404 destroyed only the 4th-century main basilica church, then the 5th century Theodosian basilica could have been built surrounded by a complex constructed primarily during the fourth century.

During the reign of Theodosius II, the emperor's elder sister, the ''Augusta''

Pulcheria () was challenged by the patriarch

Nestorius

Nestorius (; in grc, Νεστόριος; 386 – 451) was the Archbishop of Constantinople from 10 April 428 to August 431. A Christian theologian, several of his teachings in the fields of Christology and Mariology were seen as contr ...

().

The patriarch denied the ''Augusta'' access to the sanctuary of the "Great Church", likely on 15 April 428.

According to the anonymous ''Letter to Cosmas'', the virgin empress, a promoter of the

cult of the Virgin Mary who habitually partook in the

Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was institu ...

at the sanctuary of Nestorius's predecessors, claimed right of entry because of her equivalent position to the ''

Theotokos

''Theotokos'' ( Greek: ) is a title of Mary, mother of Jesus, used especially in Eastern Christianity. The usual Latin translations are ''Dei Genitrix'' or '' Deipara'' (approximately "parent (fem.) of God"). Familiar English translations a ...

'' – the Virgin Mary – "having given birth to God".

Their theological differences were part of the controversy over the title ''theotokos'' that resulted in the

Council of Ephesus

The Council of Ephesus was a council of Christian bishops convened in Ephesus (near present-day Selçuk in Turkey) in AD 431 by the Roman Emperor Theodosius II. This third ecumenical council, an effort to attain consensus in the church t ...

and the stimulation of

Monophysitism

Monophysitism ( or ) or monophysism () is a Christological term derived from the Greek (, "alone, solitary") and (, a word that has many meanings but in this context means " nature"). It is defined as "a doctrine that in the person of the inc ...

and

Nestorianism

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

, a doctrine, which like Nestorius, rejects the use of the title.

Pulcheria along with

Pope Celestine I

Pope Celestine I ( la, Caelestinus I) (c. 376 – 1 August 432) was the bishop of Rome from 10 September 422 to his death on 1 August 432. Celestine's tenure was largely spent combatting various ideologies deemed heretical. He supported the missi ...

and Patriarch

Cyril of Alexandria

Cyril of Alexandria ( grc, Κύριλλος Ἀλεξανδρείας; cop, Ⲡⲁⲡⲁ Ⲕⲩⲣⲓⲗⲗⲟⲩ ⲁ̅ also ⲡⲓ̀ⲁⲅⲓⲟⲥ Ⲕⲓⲣⲓⲗⲗⲟⲥ; 376 – 444) was the Patriarch of Alexandria from 412 to 44 ...

had Nestorius overthrown, condemned at the ecumenical council, and exiled.

The area of the western entrance to the Justinianic Hagia Sophia revealed the western remains of its Theodosian predecessor, as well as some fragments of the Constantinian church.

German archaeologist

Alfons Maria Schneider began conducting

archaeological excavations

In archaeology, excavation is the exposure, processing and recording of archaeological remains. An excavation site or "dig" is the area being studied. These locations range from one to several areas at a time during a project and can be condu ...

during the mid-1930s, publishing his final report in 1941.

Excavations in the area that had once been the 6th-century atrium of the Justinianic church revealed the monumental western entrance and atrium, along with columns and sculptural fragments from both 4th- and 5th-century churches.

Further digging was abandoned for fear of harming the structural integrity of the Justinianic building, but parts of the excavation trenches remain uncovered, laying bare the foundations of the Theodosian building.

The basilica was built by architect Rufinus. The church's main entrance, which may have had gilded doors, faced west, and there was an additional entrance to the east.

There was a central

pulpit

A pulpit is a raised stand for preachers in a Christian church. The origin of the word is the Latin ''pulpitum'' (platform or staging). The traditional pulpit is raised well above the surrounding floor for audibility and visibility, acces ...

and likely an upper gallery, possibly employed as a

matroneum (women's section).

The exterior was decorated with elaborate carvings of rich Theodosian-era designs, fragments of which have survived, while the floor just inside the portico was embellished with polychrome mosaics.

The surviving carved gable end from the centre of the western façade is decorated with a cross-roundel.

Fragments of a

frieze

In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor ...

of

relief

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces are bonded to a solid background of the same material. The term '' relief'' is from the Latin verb ''relevo'', to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

s with 12 lambs representing the

12 apostles

In Christian theology and ecclesiology, the apostles, particularly the Twelve Apostles (also known as the Twelve Disciples or simply the Twelve), were the primary disciples of Jesus according to the New Testament. During the life and ministry ...

also remain; unlike Justinian's 6th-century church, the Theodosian Hagia Sophia had both colourful floor mosaics and external decorative sculpture.

At the western end, surviving stone fragments of the structure show there was

vaulting

In architecture, a vault (French ''voûte'', from Italian ''volta'') is a self-supporting arched form, usually of stone or brick, serving to cover a space with a ceiling or roof. As in building an arch, a temporary support is needed while ring ...

, at least at the western end.

The Theodosian building had a monumental propylaeum hall with a portico that may account for this vaulting, which was thought by the original excavators in the 1930s to be part of the western entrance of the church itself.

The propylaeum opened onto an atrium which lay in front of the basilica church itself. Preceding the propylaeum was a steep monumental staircase following the contours of the ground as it sloped away westwards in the direction of the

Strategion, the Basilica, and the harbours of the

Golden Horn

The Golden Horn ( tr, Altın Boynuz or ''Haliç''; grc, Χρυσόκερας, ''Chrysókeras''; la, Sinus Ceratinus) is a major urban waterway and the primary inlet of the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey. As a natural estuary that connects with t ...

.

This arrangement would have resembled the steps outside the atrium of the Constantinian

Old St Peter's Basilica

Old St. Peter's Basilica was the building that stood, from the 4th to 16th centuries, where the new St. Peter's Basilica stands today in Vatican City. Construction of the basilica, built over the historical site of the Circus of Nero, began durin ...

in Rome.

Near the staircase, there was a cistern, perhaps to supply a fountain in the atrium or for worshippers to wash with before entering.

The 4th-century ''skeuophylakion'' was replaced in the 5th century by the present-day structure, a

rotunda constructed of banded masonry in the lower two levels and of plain brick masonry in the third.

Originally this rotunda, probably employed as a treasury for liturgical objects, had a second-floor internal gallery accessed by an external spiral staircase and two levels of niches for storage.

A further row of windows with marble window frames on the third level remain bricked up.

The gallery was supported on monumental

consoles with carved

acanthus designs, similar to those used on the late 5th-century

Column of Leo.

A large

lintel

A lintel or lintol is a type of beam (a horizontal structural element) that spans openings such as portals, doors, windows and fireplaces. It can be a decorative architectural element, or a combined ornamented structural item. In the case of ...

of the ''skeuophylakion''

's western entrance – bricked up during the Ottoman era – was discovered inside the rotunda when it was archaeologically cleared to its foundations in 1979, during which time the brickwork was also

repointed

Repointing is the process of renewing the pointing, which is the external part of mortar joints, in masonry construction. Over time, weathering and decay cause voids in the joints between masonry units, usually in bricks, allowing the undesirable e ...

.

The ''skeuophylakion'' was again restored in 2014 by the

Vakıflar.

A fire started during the tumult of the

Nika Revolt, which had begun nearby in the

Hippodrome of Constantinople, and the second Hagia Sophia was burnt to the ground on 13–14 January 532. The court historian

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea ( grc-gre, Προκόπιος ὁ Καισαρεύς ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; la, Procopius Caesariensis; – after 565) was a prominent late antique Greek scholar from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman gen ...

wrote:

Greek cross

The Christian cross, with or without a figure of Christ included, is the main religious symbol of Christianity. A cross with a figure of Christ affixed to it is termed a ''crucifix'' and the figure is often referred to as the ''corpus'' (La ...

File:Theodosius's Hagia Sophia 3.jpg, Porphyry column; column capital; impost block

In architecture, an impost or impost block is a projecting block resting on top of a column or embedded in a wall, serving as the base for the springer or lowest voussoir of an arch.

Ornamental training

The imposts are left smooth or profiled ...

File:Hagia Sophia Theodosius 2007 007.jpg, Soffits and cornice

In architecture, a cornice (from the Italian ''cornice'' meaning "ledge") is generally any horizontal decorative moulding that crowns a building or furniture element—for example, the cornice over a door or window, around the top edge of a ...

File:Hagia Sophia Theodosius 2007 010.JPG, Columns and other fragments

File:Istanbul.Hagia Sophia010.jpg, Frieze with lambs

File:CapCorBizPil1SSofiaTeod-19Lato.jpg, Theodosian capital

File:CapCorBizPil1SSofiaTeod-19.jpg, Theodosian capital for a pilaster

In classical architecture, a pilaster is an architectural element used to give the appearance of a supporting column and to articulate an extent of wall, with only an ornamental function. It consists of a flat surface raised from the main wal ...

, one of the few remains of the church of Theodosius II

File:Theodosius's Hagia Sophia 17.jpg, Soffit

A soffit is an exterior or interior architectural feature, generally the horizontal, aloft underside of any construction element. Its archetypal form, sometimes incorporating or implying the projection of beams, is the underside of eaves (t ...

s

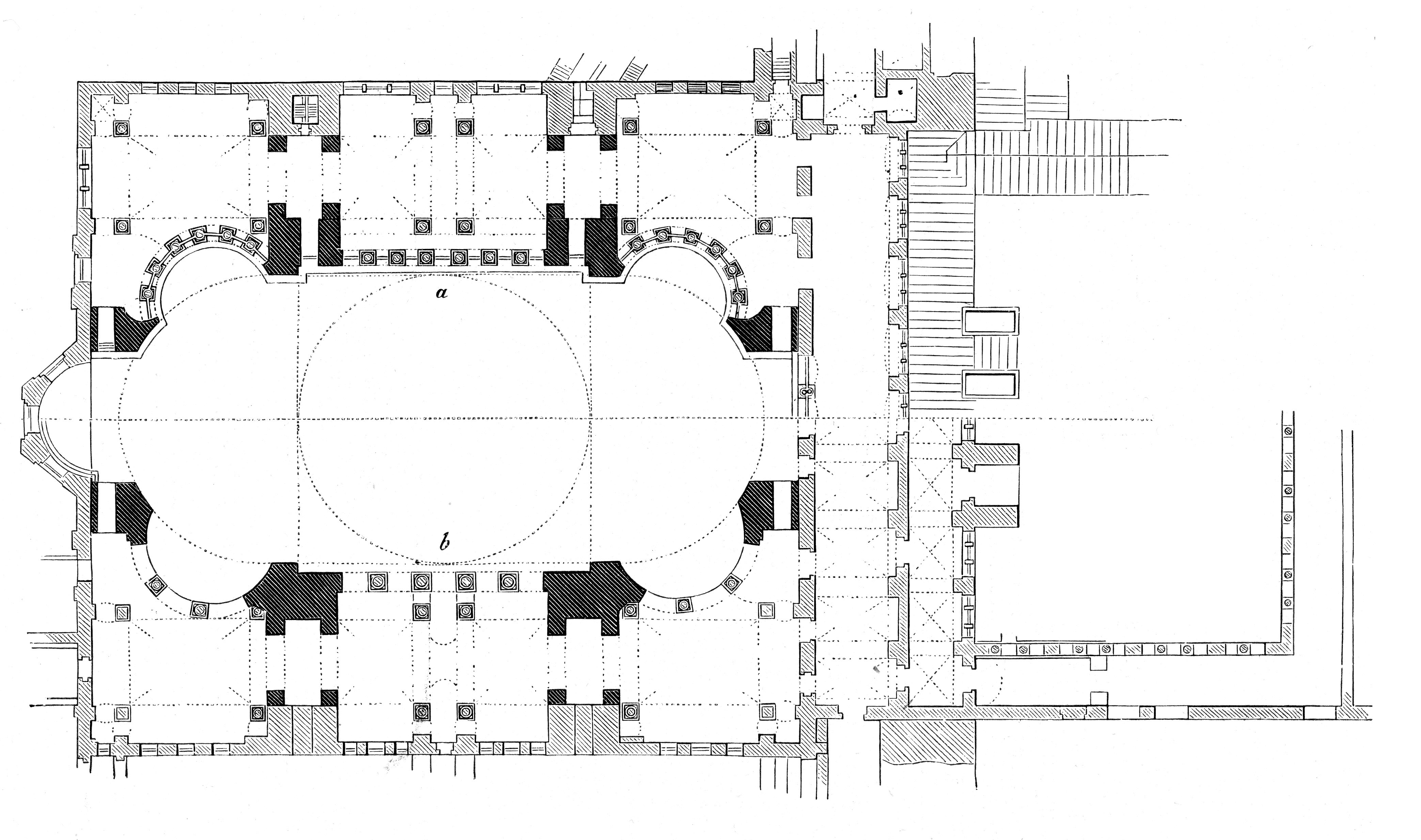

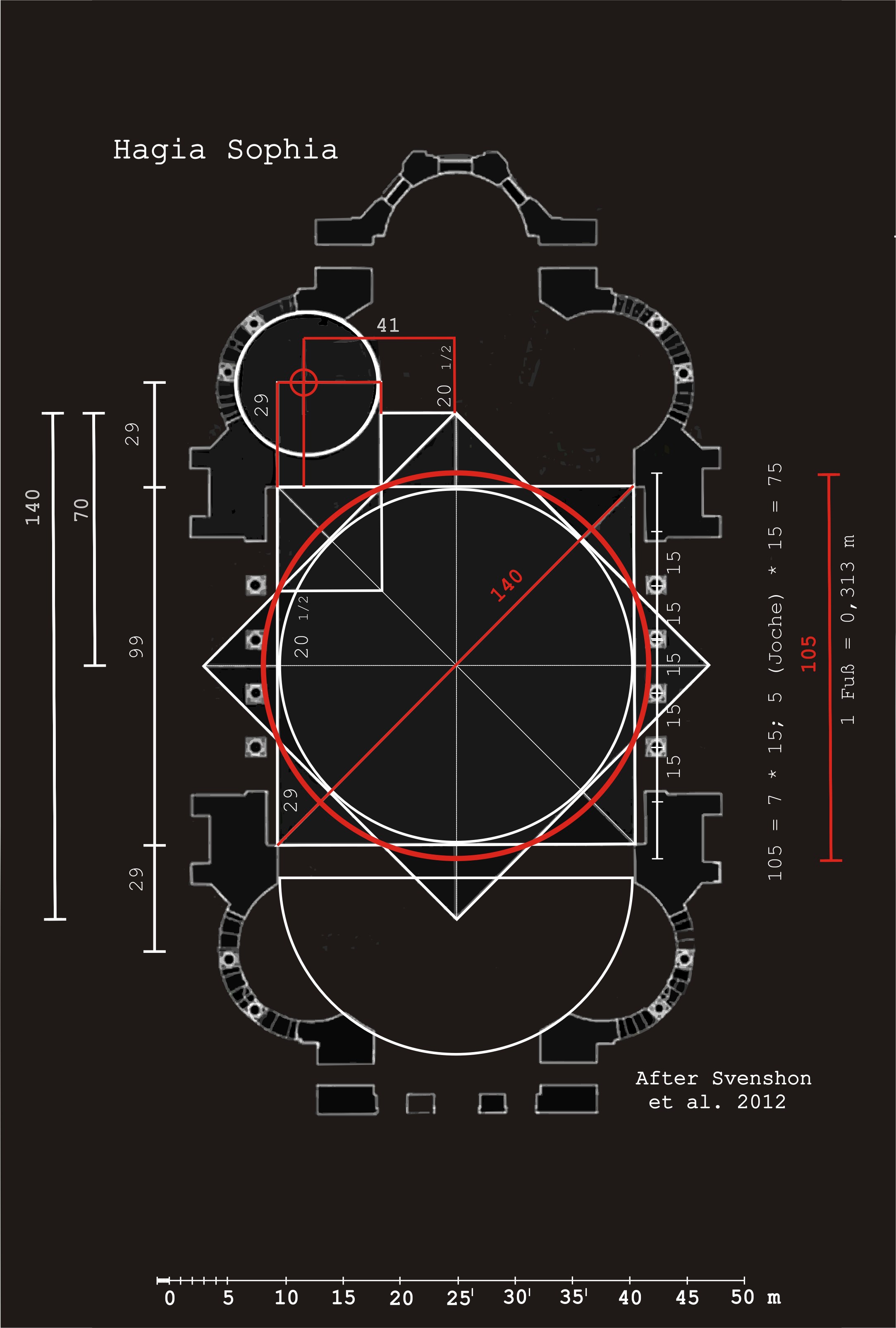

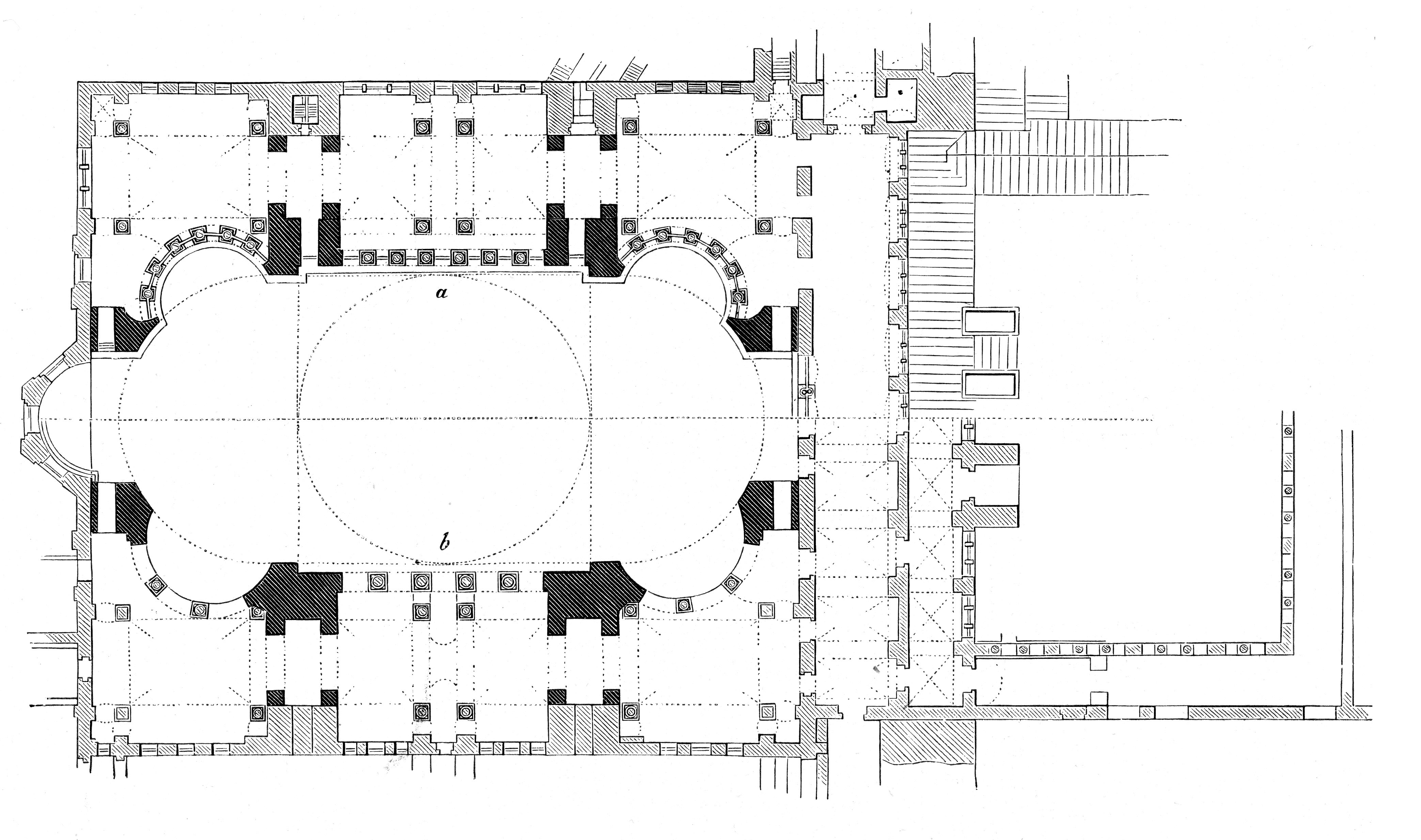

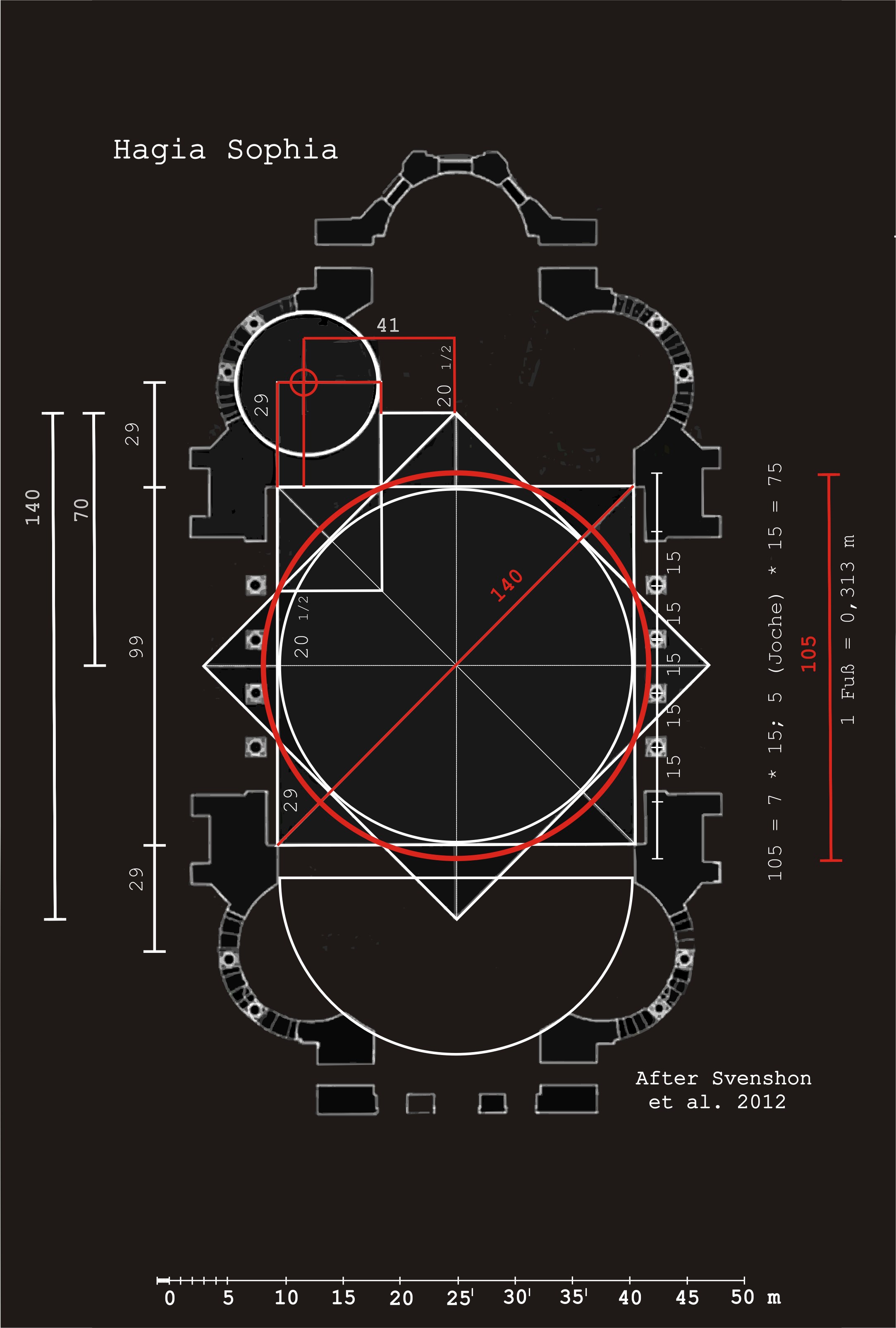

Church of Justinian I (current structure)

On 23 February 532, only a few weeks after the destruction of the second basilica, Emperor

Justinian I

Justinian I (; la, Iustinianus, ; grc-gre, Ἰουστινιανός ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was the Byzantine emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign is marked by the ambitious but only partly realized '' renov ...

inaugurated the construction of a third and entirely different basilica, larger and more majestic than its predecessors. Justinian appointed two architects, mathematician

Anthemius of Tralles

Anthemius of Tralles ( grc-gre, Ἀνθέμιος ὁ Τραλλιανός, Medieval Greek: , ''Anthémios o Trallianós''; – 533 558) was a Greek from Tralles who worked as a geometer and architect in Constantinople, the ca ...

and geometer and engineer

Isidore of Miletus

Isidore of Miletus ( el, Ἰσίδωρος ὁ Μιλήσιος; Medieval Greek pronunciation: ; la, Isidorus Miletus) was one of the two main Byzantine Greek architects (Anthemius of Tralles was the other) that Emperor Justinian I commissioned ...

, to design the building.

Construction of the church began in 532 during the short tenure of Phocas as

praetorian prefect

The praetorian prefect ( la, praefectus praetorio, el, ) was a high office in the Roman Empire. Originating as the commander of the Praetorian Guard, the office gradually acquired extensive legal and administrative functions, with its holders be ...

.

Although Phocas had been arrested in 529 as a suspected practitioner of

paganism

Paganism (from classical Latin ''pāgānus'' "rural", "rustic", later "civilian") is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Judaism. I ...

, he replaced

John the Cappadocian

John the Cappadocian ( el, Ἰωάννης ὁ Καππαδόκης) (''fl.'' 530s, living 548) was a praetorian prefect of the East (532–541) in the Byzantine Empire under Emperor Justinian I (r. 527–565). He was also a patrician and the '' ...

after the Nika Riots saw the destruction of the Theodosian church.

According to

John the Lydian

John the Lydian or John Lydus ( el, ; la, Ioannes Laurentius Lydus) (ca. AD 490 – ca. 565) was a Byzantine administrator and writer on antiquarian subjects.

Life and career

He was born in 490 AD at Philadelphia in Lydia, whence his cognomen ...

, Phocas was responsible for funding the initial construction of the building with 4,000

Roman pound

The ancient Roman units of measurement were primarily founded on the Hellenic system, which in turn was influenced by the Egyptian system and the Mesopotamian system. The Roman units were comparatively consistent and well documented.

Length

T ...

s of gold, but he was dismissed from office in October 532.

[John Lydus, ''De Magistratibus reipublicae Romanae'' III.76] John the Lydian wrote that Phocas had acquired the funds by moral means, but

Evagrius Scholasticus

Evagrius Scholasticus ( el, Εὐάγριος Σχολαστικός) was a Syrian scholar and intellectual living in the 6th century AD, and an aide to the patriarch Gregory of Antioch. His surviving work, ''Ecclesiastical History'' (), compris ...

later wrote that the money had been obtained unjustly.

According to

Anthony Kaldellis

Anthony Kaldellis ( gr, Αντώνιος Καλδέλλης; born 29 November 1971) is a Greek historian who is Professor and a faculty member of the Department of Classics at the University of Chicago. He is a specialist in Greek historiograph ...

, both of Hagia Sophia's architects named by Procopius were associated with to the

school

A school is an educational institution designed to provide learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers. Most countries have systems of formal education, which is sometimes co ...

of the pagan philosopher

Ammonius of Alexandria.

It is possible that both they and John the Lydian considered Hagia Sophia a great temple for the supreme

Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some id ...

deity

A deity or god is a supernatural being who is considered divine or sacred. The ''Oxford Dictionary of English'' defines deity as a god or goddess, or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greate ...

who manifestated through light and the sun. John the Lydian describes the church as the "''

temenos

A ''temenos'' ( Greek: ; plural: , ''temenē''). is a piece of land cut off and assigned as an official domain, especially to kings and chiefs, or a piece of land marked off from common uses and dedicated to a god, such as a sanctuary, holy gr ...

'' of the Great God" ().

Originally the exterior of the church was covered with

marble veneer, as indicated by remaining pieces of marble and surviving attachments for lost panels on the building's western face.

The white marble

cladding

Cladding is an outer layer of material covering another. It may refer to the following:

*Cladding (boiler), the layer of insulation and outer wrapping around a boiler shell

*Cladding (construction), materials applied to the exterior of buildings

...

of much of the church, together with

gilding

Gilding is a decorative technique for applying a very thin coating of gold over solid surfaces such as metal (most common), wood, porcelain, or stone. A gilded object is also described as "gilt". Where metal is gilded, the metal below was tradi ...

of some parts, would have given Hagia Sophia a shimmering appearance quite different from the brick- and plaster-work of the modern period, and would have significantly increased its visibility from the sea.

The cathedral's interior surfaces were sheathed with polychrome marbles, green and white with purple

porphyry, and gold mosaics. The exterior was clad in

stucco

Stucco or render is a construction material made of aggregates, a binder, and water. Stucco is applied wet and hardens to a very dense solid. It is used as a decorative coating for walls and ceilings, exterior walls, and as a sculptural and a ...

that was tinted yellow and red during the 19th-century restorations by the

Fossati architects.

The construction is described by Procopius in ''On Buildings'' (, ).

Columns and other marble elements were imported from throughout the Mediterranean, although the columns were once thought to be

spoils from cities such as Rome and Ephesus. Even though they were made specifically for Hagia Sophia, they vary in size. More than ten thousand people were employed during the construction process. This new church was contemporaneously recognized as a major work of architecture. Outside the church was an elaborate array of monuments around the bronze-plated

Column of Justinian

The Column of Justinian was a Roman triumphal column erected in Constantinople by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I in honour of his victories in 543. It stood in the western side of the great square of the Augustaeum, between the Hagia Sophia ...

, topped by an equestrian statue of the emperor which dominated the

Augustaeum

The ''Augustaion'' ( el, ) or, in Latin, ''Augustaeum'', was an important ceremonial square in ancient and medieval Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey), roughly corresponding to the modern ''Aya Sofya Meydanı'' ( Turkish, "Hagia Sophia Squa ...

, the open square outside the church which connected it with the

Great Palace complex through the

Chalke Gate

The Chalke Gate ( el, ), was the main ceremonial entrance (vestibule) to the Great Palace of Constantinople in the Byzantine period. The name, which means "the Bronze Gate", was given to it either because of the bronze portals or from the gilde ...

. At the edge of the Augustaeum was the

Milion

The Milion ( grc-gre, Μίλιον or , ''Míllion''; tr, Milyon taşı) was a monument erected in the early 4th century AD in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). It was the Byzantine zero-mile marker, the starting-place for the measu ...

and the Regia, the first stretch of Constantinople's main thoroughfare, the

''Mese''. Also facing the Augustaeum were the enormous Constantinian ''

thermae

In ancient Rome, (from Greek , "hot") and (from Greek ) were facilities for bathing. usually refers to the large imperial bath complexes, while were smaller-scale facilities, public or private, that existed in great numbers throughout ...

'', the

Baths of Zeuxippus

The Baths of Zeuxippus were popular public baths in the city of Constantinople. They took their name because they were built on a site previously occupied by a temple of Zeus,Gilles, P. p. 70 on the earlier Greek Acropolis in Byzantion. Constructe ...

, and the Justinianic civic basilica under which was the vast

cistern

A cistern (Middle English ', from Latin ', from ', "box", from Greek ', "basket") is a waterproof receptacle for holding liquids, usually water. Cisterns are often built to catch and store rainwater. Cisterns are distinguished from wells by ...

known as the

Basilica Cistern

The Basilica Cistern, or Cisterna Basilica ( el, βασιλική κινστέρνή, tr, Yerebatan Sarnıcı or tr, Yerebatan Saray, label=none, "Subterranean Cistern" or "Subterranean Palace"), is the largest of several hundred ancient ciste ...

. On the opposite side of Hagia Sophia was the former cathedral, Hagia Irene.

Referring to the destruction of the Theodosian Hagia Sophia and comparing the new church with the old, Procopius lauded the Justinianic building, writing in ''De aedificiis'':

Upon seeing the finished building, the Emperor reportedly said: ''"Salomon, I have surpassed thee''" ().

Justinian and

Patriarch Menas

Menas (Minas) ( grc, Μηνάς) (died 25 August 552) considered a saint in the Calcedonian affirming church and by extension both the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church of our times, was born in Alexandria, and enters the record ...

inaugurated the new basilica on 27 December 537, 5 years and 10 months after construction started, with much pomp.

[Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 86.] Hagia Sophia was the seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople and a principal setting for Byzantine imperial ceremonies, such as

coronation

A coronation is the act of placement or bestowal of a crown upon a monarch's head. The term also generally refers not only to the physical crowning but to the whole ceremony wherein the act of crowning occurs, along with the presentation of o ...

s. The basilica offered

sanctuary from persecution to criminals, although there was disagreement about whether Justinian had intended for murderers to be eligible for asylum.

Earthquakes in August 553 and on

14 December 557 caused cracks in the main dome and eastern

semi-dome. According to the ''Chronicle'' of

John Malalas

John Malalas ( el, , ''Iōánnēs Malálas''; – 578) was a Byzantine chronicler from Antioch (now Antakya, Turkey).

Life

Malalas was of Syrian descent, and he was a native speaker of Syriac who learned how to write in Greek later ...

, during a subsequent earthquake on 7 May 558,

the eastern semi-dome collapsed, destroying the

ambon, altar, and

ciborium. The collapse was due mainly to the excessive

bearing load and to the enormous

shear load

Shear may refer to:

Textile production

*Animal shearing, the collection of wool from various species

**Sheep shearing

*The removal of nap during wool cloth production

Science and technology Engineering

* Shear strength (soil), the shear strengt ...

of the dome, which was too flat.

These caused the deformation of the piers which sustained the dome.

Justinian ordered an immediate restoration. He entrusted it to Isidorus the Younger, nephew of Isidore of Miletus, who used lighter materials. The entire vault had to be taken down and rebuilt 20 Byzantine feet () higher than before, giving the building its current interior height of . Moreover, Isidorus changed the dome type, erecting a ribbed dome with

pendentives

In architecture, a pendentive is a constructional device permitting the placing of a circular dome over a square room or of an elliptical dome over a rectangular room. The pendentives, which are triangular segments of a sphere, taper to point ...

whose diameter was between 32.7 and 33.5 m.

Under Justinian's orders, eight

Corinthian columns

The Corinthian order ( Greek: Κορινθιακός ρυθμός, Latin: ''Ordo Corinthius'') is the last developed of the three principal classical orders of Ancient Greek architecture and Roman architecture. The other two are the Doric ord ...

were disassembled from

Baalbek

Baalbek (; ar, بَعْلَبَكّ, Baʿlabakk, Syriac-Aramaic: ܒܥܠܒܟ) is a city located east of the Litani River in Lebanon's Beqaa Valley, about northeast of Beirut. It is the capital of Baalbek-Hermel Governorate. In Greek and Roman ...

, Lebanon and shipped to Constantinople around 560. This reconstruction, which gave the church its present 6th-century form, was completed in 562. The poet

Paul the Silentiary composed an ''

ekphrasis

The word ekphrasis, or ecphrasis, comes from the Greek for the written description of a work of art produced as a rhetorical or literary exercise, often used in the adjectival form ekphrastic. It is a vivid, often dramatic, verbal descrip ...

'', or long visual poem, for the re-dedication of the basilica presided over by

Patriarch Eutychius on 23 December 562. Paul the Silentiary's poem is conventionally known under the Latin title ''Descriptio Sanctae Sophiae'', and he was also author of another ''ekphrasis'' on the ambon of the church, the ''Descripto Ambonis''.

According to the history of the patriarch

Nicephorus I

Nikephoros I or Nicephorus I ( gr, Νικηφόρος; 750 – 26 July 811) was Byzantine emperor from 802 to 811. Having served Empress Irene as '' genikos logothetēs'', he subsequently ousted her from power and took the throne himself. In r ...

and the chronicler

Theophanes the Confessor

Theophanes the Confessor ( el, Θεοφάνης Ὁμολογητής; c. 758/760 – 12 March 817/818) was a member of the Byzantine aristocracy who became a monk and chronicler. He served in the court of Emperor Leo IV the Khazar before taking ...

, various liturgical vessels of the cathedral were melted down on the order of the emperor

Heraclius

Heraclius ( grc-gre, Ἡράκλειος, Hērákleios; c. 575 – 11 February 641), was Eastern Roman emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the exarch of Africa, led a revol ...

() after the capture of

Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandri ...

and

Roman Egypt

, conventional_long_name = Roman Egypt

, common_name = Egypt

, subdivision = Province

, nation = the Roman Empire

, era = Late antiquity

, capital = Alexandria

, title_leader = Praefectus Augustalis

, image_map = Roman E ...

by the

Sasanian Empire

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

during the

Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 was the final and most devastating of the series of wars fought between the Byzantine / Roman Empire and the Sasanian Empire of Iran. The previous war between the two powers had ended in 591 after ...

.

Theophanes states that these were made into gold and silver coins, and a tribute was paid to the

Avars.

The Avars attacked the extramural areas of Constantinople in 623, causing the Byzantines to move the "garment" relic () of Mary, mother of Jesus to Hagia Sophia from its usual shrine of the

Church of the ''Theotokos'' at

Blachernae

Blachernae ( gkm, Βλαχέρναι) was a suburb in the northwestern section of Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire. It is the site of a water source and a number of prominent churches were built there, most notably the grea ...

just outside the

Theodosian Walls

The Walls of Constantinople ( el, Τείχη της Κωνσταντινουπόλεως) are a series of defensive stone walls that have surrounded and protected the city of Constantinople (today Istanbul in Turkey) since its founding as the ...

. On 14 May 626, the ''

Scholae Palatinae

The ''Scholae Palatinae'' (literally "Palatine Schools", in gr, Σχολαί, Scholai) were an elite military guard unit, usually ascribed to the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great as a replacement for the '' equites singulares Augusti'', the c ...

'', an elite body of soldiers, protested in Hagia Sophia against a planned increase in bread prices, after a stoppage of the ''

Cura Annonae'' rations resulting from the loss of the grain supply from Egypt. The Persians under

Shahrbaraz

Shahrbaraz (also spelled Shahrvaraz or Shahrwaraz; New Persian: ), was shah (king) of the Sasanian Empire from 27 April 630 to 9 June 630. He usurped the throne from Ardashir III, and was killed by Iranian nobles after forty days. Before usurp ...

and the Avars together laid the

siege of Constantinople

The following is a list of sieges of Constantinople, a historic city located in an area which is today part of Istanbul, Turkey. The city was built on the land that links Europe to Asia through Bosporus and connects the Sea of Marmara and the ...

in 626; according to the ''

Chronicon Paschale

''Chronicon Paschale'' (the ''Paschal'' or ''Easter Chronicle''), also called ''Chronicum Alexandrinum'', ''Constantinopolitanum'' or ''Fasti Siculi'', is the conventional name of a 7th-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world. Its name com ...

'', on 2 August 626,

Theodore Syncellus, a

deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

and

presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros,'' which means elder or senior, although many in the Christian antiquity would understand ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning a ...

of Hagia Sophia, was among those who negotiated unsuccessfully with the ''

khagan

Khagan or Qaghan (Mongolian:; or ''Khagan''; otk, 𐰴𐰍𐰣 ), or , tr, Kağan or ; ug, قاغان, Qaghan, Mongolian Script: ; or ; fa, خاقان ''Khāqān'', alternatively spelled Kağan, Kagan, Khaghan, Kaghan, Khakan, Khakhan ...

'' of the Avars.

A

homily

A homily (from Greek ὁμιλία, ''homilía'') is a commentary that follows a reading of scripture, giving the "public explanation of a sacred doctrine" or text. The works of Origen and John Chrysostom (known as Paschal Homily) are considered ex ...

, attributed by existing

manuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand – or, once practical typewriters became available, typewritten – as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced i ...

to Theodore Syncellus and possibly delivered on the anniversary of the event, describes the translation of the Virgin's garment and its ceremonial re-translation to Blachernae by the patriarch

Sergius I after the threat had passed.

Another eyewitness account of the Avar–Persian siege was written by

George of Pisidia, a deacon of Hagia Sophia and an administrative official in for the patriarchate from

Antioch in Pisidia

Antioch in Pisidia – alternatively Antiochia in Pisidia or Pisidian Antioch ( el, Ἀντιόχεια τῆς Πισιδίας) and in Roman Empire, Latin: ''Antiochia Caesareia'' or ''Antiochia Colonia Caesarea'' – was a city in th ...

.

Both George and Theodore, likely members of Sergius's literary circle, attribute the defeat of the Avars to the intervention of the ''Theotokos'', a belief that strengthened in following centuries.

In 726, the emperor

Leo the Isaurian

Leo III the Isaurian ( gr, Λέων ὁ Ἴσαυρος, Leōn ho Isauros; la, Leo Isaurus; 685 – 18 June 741), also known as the Syrian, was Byzantine Emperor from 717 until his death in 741 and founder of the Isaurian dynasty. He put an en ...

issued a series of edicts against the veneration of images, ordering the army to destroy all icons – ushering in the period of

Byzantine iconoclasm

The Byzantine Iconoclasm ( gr, Εικονομαχία, Eikonomachía, lit=image struggle', 'war on icons) were two periods in the history of the Byzantine Empire when the use of religious images or icons was opposed by religious and imperial a ...

. At that time, all religious pictures and statues were removed from the Hagia Sophia. Following a brief hiatus during the reign of Empress

Irene

Irene is a name derived from εἰρήνη (eirēnē), the Greek for "peace".

Irene, and related names, may refer to:

* Irene (given name)

Places

* Irene, Gauteng, South Africa

* Irene, South Dakota, United States

* Irene, Texas, United State ...

(797–802), the iconoclasts returned. Emperor

Theophilus

Theophilus is a male given name with a range of alternative spellings. Its origin is the Greek word Θεόφιλος from θεός (God) and φιλία (love or affection) can be translated as "Love of God" or "Friend of God", i.e., it is a theoph ...

() had two-winged bronze doors with his

monogram

A monogram is a motif made by overlapping or combining two or more letters or other graphemes to form one symbol. Monograms are often made by combining the initials of an individual or a company, used as recognizable symbols or logos. A series ...

s installed at the southern entrance of the church.

The basilica suffered damage, first in a great fire in 859, and again in an earthquake on 8 January 869 that caused the collapse of one of the half-domes.

Emperor

Basil I

Basil I, called the Macedonian ( el, Βασίλειος ὁ Μακεδών, ''Basíleios ō Makedṓn'', 811 – 29 August 886), was a Byzantine Emperor who reigned from 867 to 886. Born a lowly peasant in the theme of Macedonia, he rose in the ...

ordered repair of the tympanas, arches, and vaults.

In his book ''

De caerimoniis aulae Byzantinae'' ("Book of Ceremonies"), the emperor

Constantine VII

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe ...

() wrote a detailed account of the ceremonies held in the Hagia Sophia by the emperor and the patriarch.

In the 940s or 950s, probably around 954 or 955, after the

Rus'–Byzantine War of 941 and the death of the

Grand Prince of Kiev,

Igor I

Igor may refer to:

People

* Igor (given name), an East Slavic given name and a list of people with the name

* Mighty Igor (1931–2002), former American professional wrestler

* Igor Volkoff, a professional wrestler from NWA All-Star Wrestling

* ...

(), his widow

Olga of Kiev

Olga ( orv, Вольга, Volĭga; (); russian: Ольга (); uk, Ольга (). Old Norse: '; Lith: ''Alge''; Christian name: ''Elena''; c. 890–925 – 969) was a regent of Kievan Rus' for her son Sviatoslav from 945 until 960. Following ...

– regent for her infant son

Sviatoslav I () – visited the emperor Constantine VII and was received as queen of the

Rus' in Constantinople.

She was probably baptized in Hagia Sophia's baptistery, taking the name of the reigning ''augusta'',

Helena Lecapena

Helena Lekapene ( grc-x-byzant, Ἑλένη Λεκαπηνή, translit=Lecapena) (c. 910 – 19 September 961) was the empress consort of Constantine VII, known to have acted as his political adviser and ''de facto'' co-regent. She was a daughter ...

, and receiving the titles

''zōstē patrikía'' and the styles of ''

archon

''Archon'' ( gr, ἄρχων, árchōn, plural: ἄρχοντες, ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem αρχ-, mean ...

tissa'' and

hegemon

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

of the Rus'.

Her baptism was an important step towards the

Christianization of the Kievan Rus'

Christianization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise.2C -ize .28-isation.2C -ization.29, or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of ...

, though the emperor's treatment of her visit in ''De caerimoniis'' does not mention baptism.

Olga is deemed a saint and

equal-to-the-apostles

Equal-to-apostles or equal-to-the-apostles (; la, aequalis apostolis; ar, معادل الرسل, ''muʿādil ar-rusul''; ka, მოციქულთასწორი, tr; ro, întocmai cu Apostolii; russian: равноапостольный, ...

() in the Eastern Orthodox Church. According to an early 14th-century source, the second church in Kiev,

Saint Sophia's, was founded in ''

anno mundi

(from Latin "in the year of the world"; he, לבריאת העולם, Livryat haOlam, lit=to the creation of the world), abbreviated as AM or A.M., or Year After Creation, is a calendar era based on the biblical accounts of the creation of ...

'' 6460 in the

Byzantine calendar

The Byzantine calendar, also called the Roman calendar, the Creation Era of Constantinople or the Era of the World ( grc, Ἔτη Γενέσεως Κόσμου κατὰ Ῥωμαίους, also or , abbreviated as ε.Κ.; literal translation of ...

, or .

The name of this future cathedral of Kiev probably commemorates Olga's baptism at Hagia Sophia.

After the great earthquake of 25 October 989, which collapsed the western dome arch, Emperor

Basil II

Basil II Porphyrogenitus ( gr, Βασίλειος Πορφυρογέννητος ;) and, most often, the Purple-born ( gr, ὁ πορφυρογέννητος, translit=ho porphyrogennetos).. 958 – 15 December 1025), nicknamed the Bulgar S ...

asked for the Armenian architect

Trdat, creator of the

Cathedral of Ani

The Cathedral of Ani ( hy, Անիի մայր տաճար, ''Anii mayr tačar''; tr, Ani Katedrali) is the largest standing building in Ani, the capital city of medieval Bagratid Armenia, located in present-day eastern Turkey, on the border with ...

, to direct the repairs. He erected again and reinforced the fallen dome arch, and rebuilt the west side of the dome with 15 dome ribs.

[Müller-Wiener (1977), p. 87.] The extent of the damage required six years of repair and reconstruction; the church was re-opened on 13 May 994. At the end of the reconstruction, the church's decorations were renovated, including the addition of four immense paintings of cherubs; a new depiction of Christ on the dome; a burial cloth of Christ shown on Fridays, and on the

apse

In architecture, an apse (plural apses; from Latin 'arch, vault' from Ancient Greek 'arch'; sometimes written apsis, plural apsides) is a semicircular recess covered with a hemispherical vault or semi-dome, also known as an '' exedra''. ...

a new depiction of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus, between the apostles Peter and Paul.

[Mamboury (1953) p. 287] On the great side arches were painted the prophets and the teachers of the church.

According to the 13th-century Greek historian

Niketas Choniates

Niketas or Nicetas Choniates ( el, Νικήτας Χωνιάτης; c. 1155 – 1217), whose actual surname was Akominatos (Ἀκομινάτος), was a Byzantine Greek government official and historian – like his brother Michael Akominatos, w ...

, the emperor

John II Comnenus celebrated a revived

Roman triumph

The Roman triumph (') was a civil ceremony and religious rite of ancient Rome, held to publicly celebrate and sanctify the success of a military commander who had led Roman forces to victory in the service of the state or in some historical tra ...

after his victory over the

Danishmendids

The Danishmendids or Danishmends ( fa, دودمان دانشمند; tr, Dânişmendliler) was a Turkish beylik that ruled in north-central and eastern Anatolia from 1071/1075 to 1178. The dynasty centered originally around Sivas, Tokat, and N ...

at the siege of

Kastamon

Kastamonu is the capital district of the Kastamonu Province, Turkey. According to the 2000 census, population of the district is 102,059 of which 64,606 live in the urban center of Kastamonu. (Population of the urban center in 2010 is 91,012.) The ...

in 1133. After proceeding through the streets on foot carrying a cross with a silver ''

quadriga

A () is a car or chariot drawn by four horses abreast and favoured for chariot racing in Classical Antiquity and the Roman Empire until the Late Middle Ages. The word derives from the Latin contraction of , from ': four, and ': yoke.

The four- ...

'' bearing the icon of the Virgin Mary, the emperor participated in a ceremony at the cathedral before entering the imperial palace. In 1168, another triumph was held by the emperor

Manuel I Comnenus

Manuel I Komnenos ( el, Μανουήλ Κομνηνός, translit=Manouíl Komnenos, translit-std=ISO; 28 November 1118 – 24 September 1180), Latinized Comnenus, also called Porphyrogennetos (; " born in the purple"), was a Byzantine empero ...

, again preceding with a gilded silver ''quadriga'' bearing the icon of the Virgin from the now-demolished East Gate (or Gate of St Barbara, later the ) in the

Propontis Wall, to Hagia Sophia for a thanks-giving service, and then to the imperial palace.

In 1181, the daughter of the emperor Manuel I,

Maria Comnena, and her husband, the ''

caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, an ...

''

Renier of Montferrat

Renier or Rénier may refer to:

Given name:

* Renier Botha (born 1992), South African rugby union player

* Renier Coetzee PS, General Officer in the South African Army

* François Renier Duminy (1747–1811), French mariner, navigator, cartograph ...

, fled to Hagia Sophia at the culmination of their dispute with the empress

Maria of Antioch, regent for her son, the emperor

Alexius II Comnenus.

Maria Comnena and Renier occupied the cathedral with the support of the patriarch, refusing the imperial administration's demands for a peaceful departure.

According to Niketas Choniates, they "transformed the sacred courtyard into a military camp", garrisoned the entrances to the complex with locals and mercenaries, and despite the strong opposition of the patriarch, made the "house of prayer into a den of thieves or a well-fortified and precipitous stronghold, impregnable to assault", while "all the dwellings adjacent to Hagia Sophia and adjoining the Augusteion were demolished by

aria'smen".

[Niketas Choniates, ''Annals,'' CCXXX–CCXLII. ] A battle ensued in the Augustaion and around the

Milion

The Milion ( grc-gre, Μίλιον or , ''Míllion''; tr, Milyon taşı) was a monument erected in the early 4th century AD in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, Turkey). It was the Byzantine zero-mile marker, the starting-place for the measu ...