Habeas Corpus Suspension Act (1863) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, (1863), entitled ''An Act relating to Habeas Corpus, and regulating Judicial Proceedings in Certain Cases,'' was an

''Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman''

LSU Press, 2011. p. 106 May's bill passed the House in summer 1862, and it would later be included in the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, which would require actual indictments for suspected traitors.White

''Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman''

p. 107 In September, faced with opposition to his calling up of the militia, Lincoln again suspended habeas corpus, this time through the entire country, and made anyone charged with interfering with the draft, discouraging enlistments, or aiding the Confederacy subject to

When the Thirty-seventh Congress of the United States opened its third session in December 1862, Representative

When the Thirty-seventh Congress of the United States opened its third session in December 1862, Representative  The Senate spent the evening of March 2 into the early morning of the next day debating the conference committee amendments.''Congressional Globe'', Thirty-Seventh Congress, Third Session (1862–63), pp. 1435–1438, 1459–1477. There, several Democratic Senators attempted a

The Senate spent the evening of March 2 into the early morning of the next day debating the conference committee amendments.''Congressional Globe'', Thirty-Seventh Congress, Third Session (1862–63), pp. 1435–1438, 1459–1477. There, several Democratic Senators attempted a

The Act allowed the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus so long as the Civil War was ongoing.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 1. Normally, a judge would issue a writ of habeas corpus to compel a jailer to state the reason for holding a particular prisoner and, if the judge was not satisfied that the prisoner was being held lawfully, could release him. As a result of the Act, the jailer could now reply that a prisoner was held under the authority of the president and this response would suspend further proceedings in the case until the president lifted the suspension of habeas corpus or the Civil War ended.

The Act also provided for the release of prisoners in a section originally authored by Maryland Congressman

The Act allowed the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus so long as the Civil War was ongoing.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 1. Normally, a judge would issue a writ of habeas corpus to compel a jailer to state the reason for holding a particular prisoner and, if the judge was not satisfied that the prisoner was being held lawfully, could release him. As a result of the Act, the jailer could now reply that a prisoner was held under the authority of the president and this response would suspend further proceedings in the case until the president lifted the suspension of habeas corpus or the Civil War ended.

The Act also provided for the release of prisoners in a section originally authored by Maryland Congressman

1267

Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus as viewed by Congress

'. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin—Madison, 1907. * Wicek, William. "The Reconstruction of Federal Judicial Power, 1863–1875." ''American Journal of Legal History'' 13, no. 4 (October 1969): 333–63. * White, Jonathan W. (2011). ''Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman''. Baton Rouge: LSU Press. .

Text of Act

Text of House Bill

Text of Senate Bill

{{American Civil War United States habeas corpus law Emergency laws in the United States United States federal legislation Politics of the American Civil War Political repression in the United States 1863 in American law

Act of Congress

An Act of Congress is a statute enacted by the United States Congress. Acts may apply only to individual entities (called private laws), or to the general public ( public laws). For a bill to become an act, the text must pass through both house ...

that authorized the president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

to suspend the right of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

in response to the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

and provided for the release of political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

s. It began in the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

as an indemnity

In contract law, an indemnity is a contractual obligation of one Party (law), party (the ''indemnitor'') to Financial compensation, compensate the loss incurred by another party (the ''indemnitee'') due to the relevant acts of the indemnitor or ...

bill, introduced on December 5, 1862, releasing the president and his subordinates from any liability for having suspended habeas corpus without congressional approval. The Senate amended the House's bill, and the compromise reported out of the conference committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

altered it to qualify the indemnity and to suspend habeas corpus on Congress's own authority. Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

signed the bill into law on March 3, 1863, and suspended habeas corpus under the authority it granted him six months later. The suspension was partially lifted with the issuance of Proclamation 148 by Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

, and the Act became inoperative with the end of the Civil War. The exceptions to his Proclamation 148 were the States of Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Texas, the District of Columbia, and the Territories of New Mexico and Arizona.

Background

At the outbreak of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and t ...

in April 1861, Washington, D.C., was largely undefended, rioters in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic, and the 30th most populous city in the United States with a population of 585,708 in 2020. Baltimore wa ...

threatened to disrupt the reinforcement of the capital by rail, and Congress was not in session. The military situation made it dangerous to call Congress into session. In that same month (April 1861), Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

, the president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

, therefore authorized his military commanders to suspend the writ of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, ...

between Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia (and later up through New York City). Numerous individuals were arrested, including John Merryman

John Merryman (August 9, 1824 – November 15, 1881) of Baltimore County, Maryland, was arrested in May 1861 and held prisoner in Fort McHenry in Baltimore and was the petitioner in the case ''" Ex parte Merryman"'' which was one of the best ...

and a number of Baltimore police commissioners; the administration of justice in Baltimore was carried out through military officials. When Judge William Fell Giles

William Fell Giles (April 8, 1807 – March 21, 1879) was a United States representative from Maryland and later a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the District of Maryland.

Education and career

Born on April ...

of the United States District Court for the District of Maryland

The United States District Court for the District of Maryland (in case citations, D. Md.) is the federal district court whose jurisdiction is the state of Maryland. Appeals from the District of Maryland are taken to the United States Court ...

issued a writ of habeas corpus, the commander of Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attac ...

, Major W. W. Morris, wrote in reply, "At the date of issuing your writ, and for two weeks previous, the city in which you live, and where your court has been held, was entirely under the control of revolutionary authorities."

Merryman's lawyers appealed, and in early June 1861, U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

, writing as the United States Circuit Court

The United States circuit courts were the original intermediate level courts of the United States federal court system. They were established by the Judiciary Act of 1789. They had trial court jurisdiction over civil suits of diversity jurisdi ...

for Maryland, ruled in '' ex parte Merryman'' that Article I, section 9 of the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

reserves to Congress the power to suspend habeas corpus and thus that the president's suspension was invalid. The rest of the Supreme Court had nothing to do with ''Merryman'', and the other two Justices from the South, John Catron

John Catron (January 7, 1786 – May 30, 1865) was an American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1837 to 1865, during the Taney Court.

Early and family life

Little is known of Catron's ...

and James Moore Wayne acted as Unionists; for instance, Catron's charge to a Saint Louis grand jury, saying that armed resistance to the federal government was treason, was quoted in the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'' of July 14, 1861. The President's advisers said the circuit court's ruling was invalid and it was ignored.William H. Rehnquist, ''All the Laws But One'', 26–39.

When Congress was called into special session, July 4, 1861, President Lincoln issued a message to both houses defending his various actions, including the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, arguing that it was both necessary and constitutional for him to have suspended it without Congress. Early in the session, Senator Henry Wilson

Henry Wilson (born Jeremiah Jones Colbath; February 16, 1812 – November 22, 1875) was an American politician who was the 18th vice president of the United States from 1873 until his death in 1875 and a senator from Massachusetts from 1855 ...

introduced a joint resolution

In the United States Congress, a joint resolution is a legislative measure that requires passage by the Senate and the House of Representatives and is presented to the President for their approval or disapproval. Generally, there is no legal diff ...

"to approve and confirm certain acts of the President of the United States, for suppressing insurrection and rebellion", including the suspension of habeas corpus (S. No. 1). Senator Lyman Trumbull

Lyman Trumbull (October 12, 1813 – June 25, 1896) was a lawyer, judge, and United States Senator from Illinois and the co-author of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Born in Colchester, Connecticut, Trumbull es ...

, the Republican chairman of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standing committee of 22 U.S. senators whose role is to oversee the Department of Justice (DOJ), consider executive and judicial nominations, a ...

, had reservations about its imprecise wording, so the resolution, also opposed by anti-war Democrats, was never brought to a vote. On July 17, 1861, Trumbull introduced a bill to suppress insurrection and sedition which included a suspension of the writ of habeas corpus upon Congress's authority (S. 33). That bill was not brought to a vote before Congress ended its first session on August 6, 1861 due to obstruction by Democrats, and on July 11, 1862, the Senate Committee on the Judiciary recommended that it not be passed during the second session, either, but its proposed habeas corpus suspension section formed the basis of the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act.

In September 1861 the arrests continued, including a sitting member of Congress from Maryland, Henry May Henry May may refer to:

* Henry May (American politician) (1816–1866), U.S. Representative from Maryland

* Henry May (New Zealand politician) (1912–1995), New Zealand politician

* Henry May (VC) (1885–1941), Scottish recipient of the Victoria ...

, along with one third of the Maryland General Assembly

The Maryland General Assembly is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Maryland that convenes within the State House in Annapolis. It is a bicameral body: the upper chamber, the Maryland Senate, has 47 representatives and the lower chamber ...

, and Lincoln expanded the zone within which the writ was suspended. When Lincoln's dismissal of Justice Taney's ruling was criticized in an editorial that month by a prominent Baltimore newspaper editor Frank Key Howard, Francis Scott Key

Francis Scott Key (August 1, 1779January 11, 1843) was an American lawyer, author, and amateur poet from Frederick, Maryland, who wrote the lyrics for the American national anthem "The Star-Spangled Banner". Key observed the British bombardment ...

's grandson and Justice Taney's grand-nephew by marriage, he was himself arrested by federal troops without trial. He was imprisoned in Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attac ...

, which, as he noted, was the same fort where the Star Spangled Banner

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States. The lyrics come from the "Defence of Fort M'Henry", a poem written on September 14, 1814, by 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the bo ...

had been waving "o'er the land of the free" in his grandfather's song.

In early 1862 Lincoln took a step back from the suspension of habeas corpus controversy. On February 14, he ordered all political prisoners released, with some exceptions (such as the aforementioned newspaper editor) and offered them amnesty

Amnesty (from the Ancient Greek ἀμνηστία, ''amnestia'', "forgetfulness, passing over") is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power offici ...

for past treason or disloyalty, so long as they did not aid the Confederacy. In March 1862 Congressman Henry May, who had been released in December 1861, introduced a bill requiring the federal government to either indict by grand jury or release all other "political prisoners" still held without habeas corpus.Jonathan White''Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman''

LSU Press, 2011. p. 106 May's bill passed the House in summer 1862, and it would later be included in the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, which would require actual indictments for suspected traitors.White

''Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman''

p. 107 In September, faced with opposition to his calling up of the militia, Lincoln again suspended habeas corpus, this time through the entire country, and made anyone charged with interfering with the draft, discouraging enlistments, or aiding the Confederacy subject to

martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

. In the interim, the controversy continued with several calls made for prosecution of those who acted under Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus; former Secretary of War Simon Cameron

Simon Cameron (March 8, 1799June 26, 1889) was an American businessman and politician who represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate and served as United States Secretary of War under President Abraham Lincoln at the start of the Americ ...

had even been arrested in connection with a suit for trespass ''vi et armis'', assault and battery, and false imprisonment. Senator Thomas Holliday Hicks

Thomas Holliday Hicks (September 2, 1798February 14, 1865) was a politician in the divided border-state of Maryland during the American Civil War. As governor, opposing the Democrats, his views accurately reflected the conflicting local loyalt ...

, who had been governor of Maryland during the crisis, told the Senate, "I believe that arrests and arrests alone saved the State of Maryland not only from greater degradation than she suffered, but from everlasting destruction." He also said, "I approved them he arreststhen, and I approve them now; and the only thing for which I condemn the Administration in regard to that matter is that they let some of these men out."

Legislative history

When the Thirty-seventh Congress of the United States opened its third session in December 1862, Representative

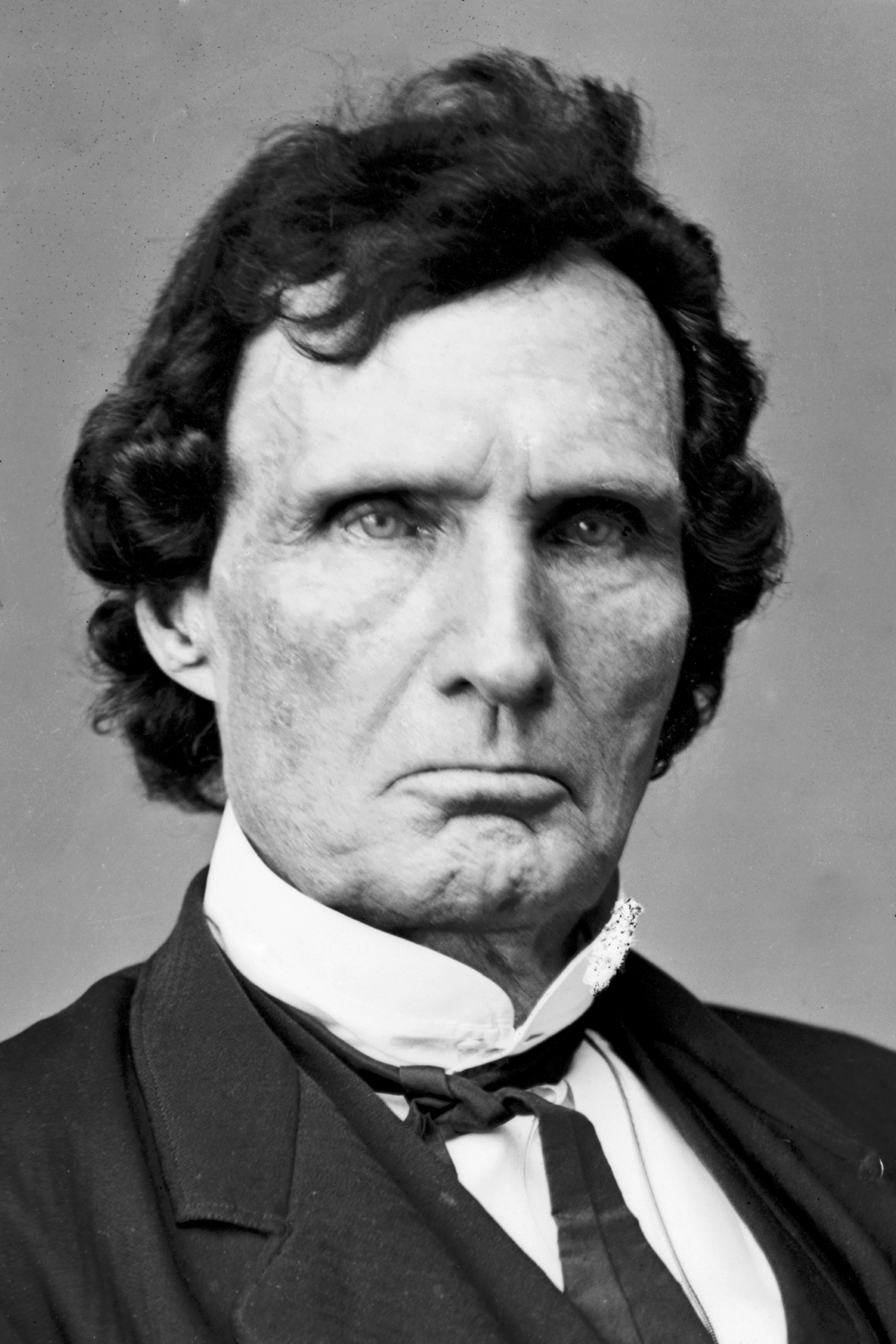

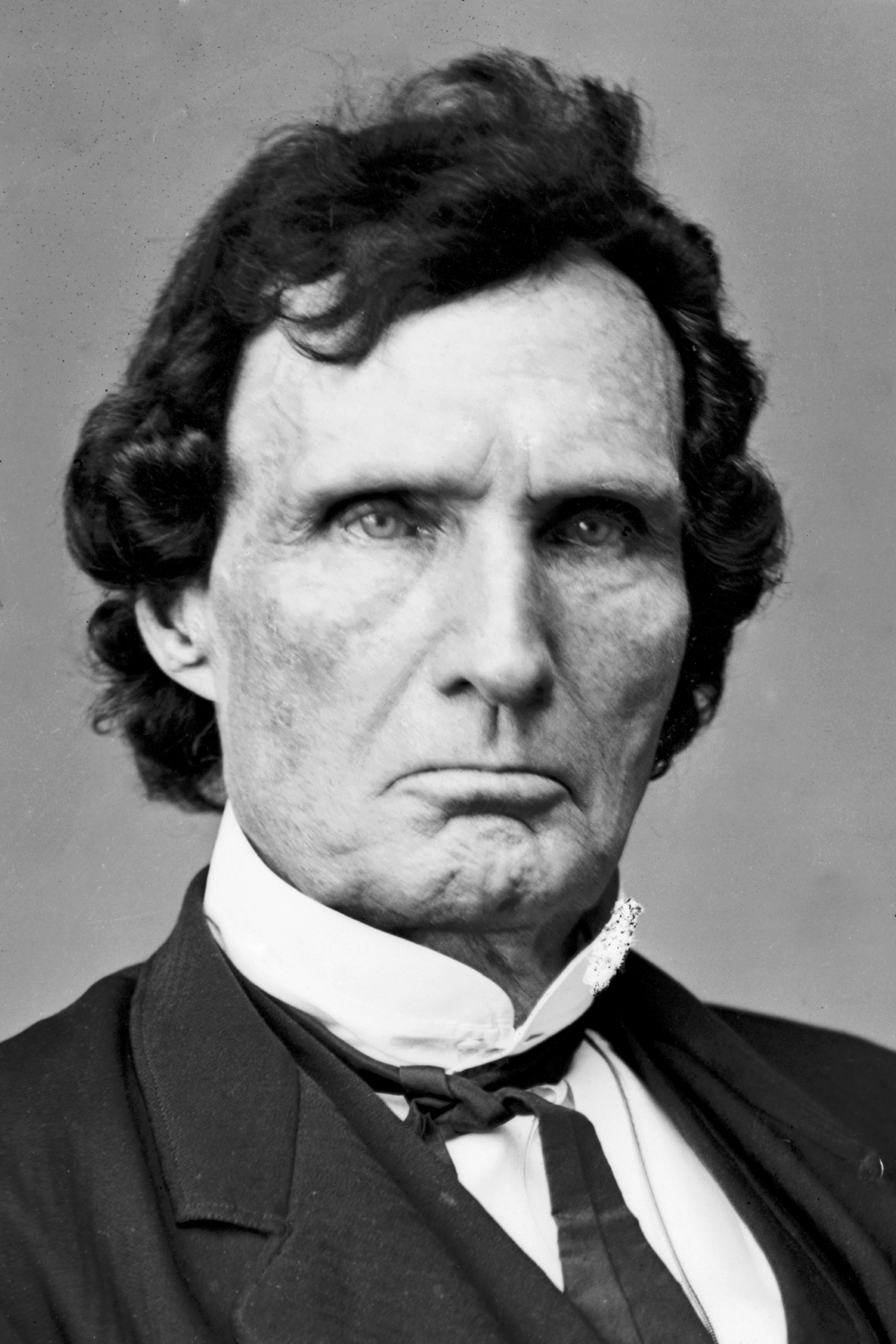

When the Thirty-seventh Congress of the United States opened its third session in December 1862, Representative Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

introduced a bill "to indemnify the President and other persons for suspending the writ of habeas corpus, and acts done in pursuance thereof" (H.R. 591). This bill passed the House over relatively weak opposition on December 8, 1862.George Clarke Sellery, ''Lincoln's Suspension of Habeas Corpus'', 34–51.

When it came time for the Senate to consider Stevens' indemnity bill, however, the Committee on the Judiciary Committee on the Judiciary may mean:

* United States House Committee on the Judiciary

* United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary

The United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary, informally the Senate Judiciary Committee, is a standi ...

's amendment substituted an entirely new bill for it. The Senate version referred all suits and prosecutions regarding arrest and imprisonment to the regional federal circuit court with the stipulation that no one acting under the authority of the president could be faulted if "there was reasonable or probable cause", or if they acted "in good faith", until after the adjournment of the next session of Congress. Unlike Stevens' bill, it did not suggest that the president's suspension of habeas corpus upon his own authority had been legal.

The Senate passed its version of the bill on January 28, 1863, and the House took it up in mid-February before voting to send the bill to a conference committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

on February 19. The House appointed Thaddeus Stevens, John Bingham

John Armor Bingham (January 21, 1815 – March 19, 1900) was an American politician who served as a Republican representative from Ohio and as the United States ambassador to Japan. In his time as a congressman, Bingham served as both ass ...

, and George H. Pendleton to the conference committee. The Senate agreed to a conference the following day and appointed Lyman Trumbull, Jacob Collamer, and Waitman T. Willey

Waitman Thomas Willey (October 18, 1811May 2, 1900) was an American lawyer and politician from Morgantown, West Virginia. One of the founders of the state of West Virginia during the American Civil War, he served in the United States Senate ...

. Stevens, Bingham, Trumbull, and Collamer were all Republicans; Willey was a Unionist; Pendleton was the only Democrat.

On February 27, the conference committee issued its report. The result was an entirely new bill authorizing the explicit suspension of habeas corpus.

In the House, several members left, depriving the chamber of a quorum

A quorum is the minimum number of members of a deliberative assembly (a body that uses parliamentary procedure, such as a legislature) necessary to conduct the business of that group. According to '' Robert's Rules of Order Newly Revised'', the ...

. The Sergeant-at-Arms

A serjeant-at-arms, or sergeant-at-arms, is an officer appointed by a deliberative body, usually a legislature, to keep order during its meetings. The word "serjeant" is derived from the Latin ''serviens'', which means "servant". Historically, ...

was dispatched to compel attendance and several representatives were fined for their absence. The following Monday, March 2, the day before the Thirty-Seventh Congress had previously voted to adjourn

In parliamentary procedure, an adjournment ends a meeting. It could be done using a motion to adjourn.

A time for another meeting could be set using the motion to fix the time to which to adjourn. This motion establishes an adjourned meeting.

...

, the House voted to accept the new bill, with 99 members voting in the affirmative and 44 against.

The Senate spent the evening of March 2 into the early morning of the next day debating the conference committee amendments.''Congressional Globe'', Thirty-Seventh Congress, Third Session (1862–63), pp. 1435–1438, 1459–1477. There, several Democratic Senators attempted a

The Senate spent the evening of March 2 into the early morning of the next day debating the conference committee amendments.''Congressional Globe'', Thirty-Seventh Congress, Third Session (1862–63), pp. 1435–1438, 1459–1477. There, several Democratic Senators attempted a filibuster

A filibuster is a political procedure in which one or more members of a legislative body prolong debate on proposed legislation so as to delay or entirely prevent decision. It is sometimes referred to as "talking a bill to death" or "talking out ...

. Cloture

Cloture (, also ), closure or, informally, a guillotine, is a motion or process in parliamentary procedure aimed at bringing debate to a quick end. The cloture procedure originated in the French National Assembly, from which the name is taken. ' ...

had not yet been adopted as a rule in the Senate, so there was no way to prevent a minuscule minority from holding up business by refusing to surrender the floor

A floor is the bottom surface of a room or vehicle. Floors vary from simple dirt in a cave to many layered surfaces made with modern technology. Floors may be stone, wood, bamboo, metal or any other material that can support the expected load ...

. First James Walter Wall of New Jersey spoke until midnight, when Willard Saulsbury, Sr., of Delaware gave Republicans an opportunity to surrender by moving to adjourn

In parliamentary procedure, an adjournment ends a meeting. It could be done using a motion to adjourn.

A time for another meeting could be set using the motion to fix the time to which to adjourn. This motion establishes an adjourned meeting.

...

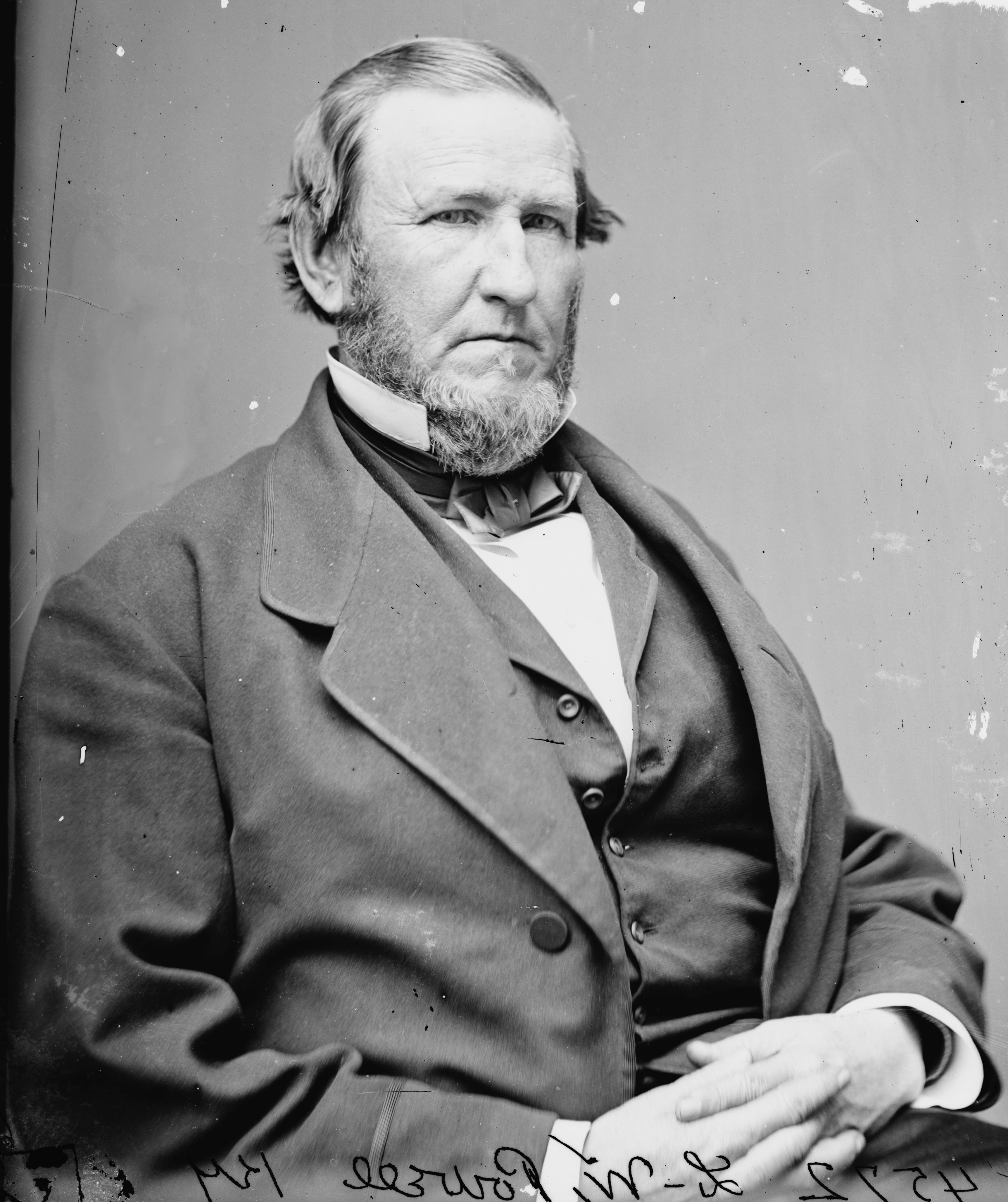

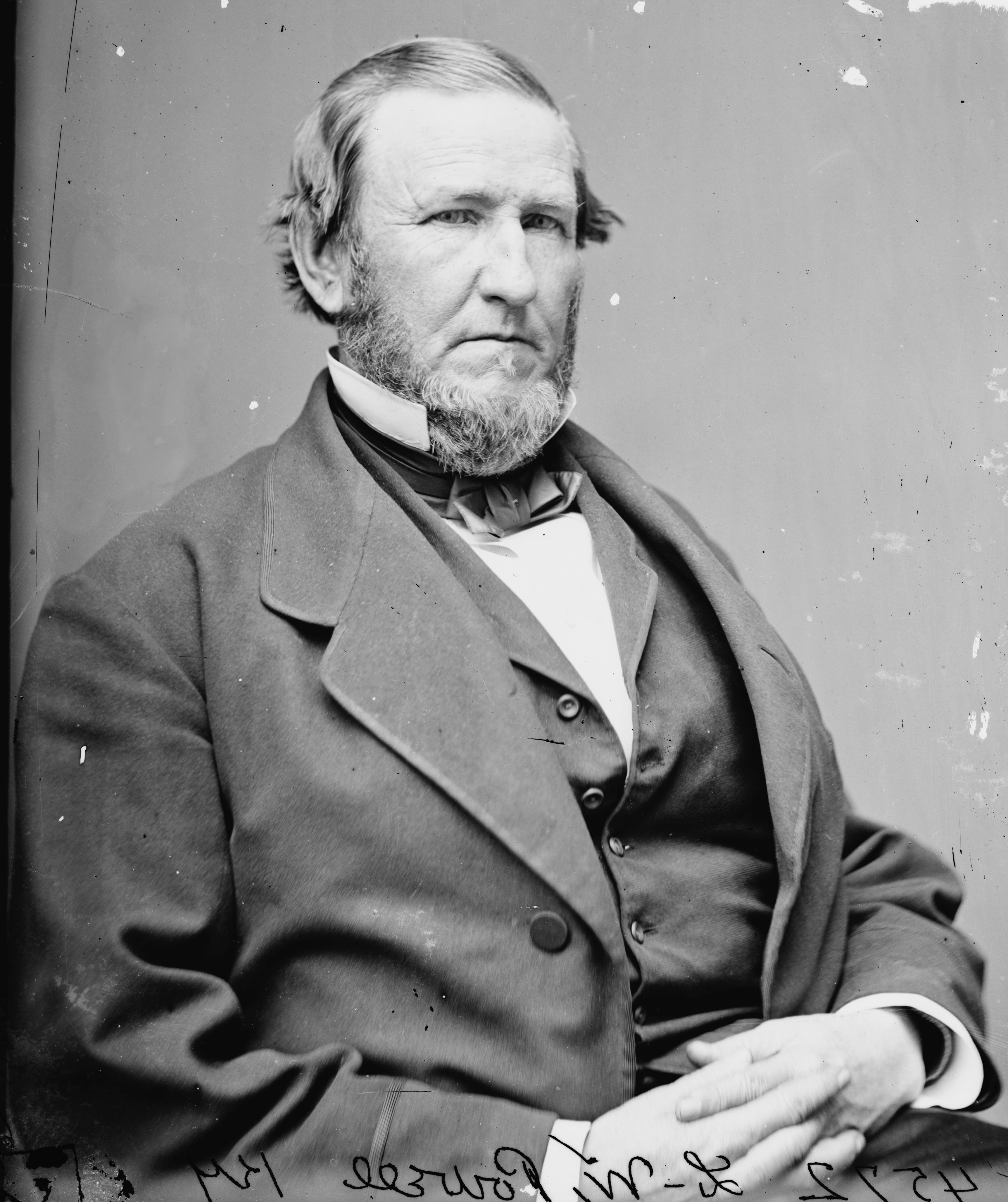

. That motion was defeated 5–31, after which Lazarus W. Powell

Lazarus Whitehead Powell (October 6, 1812 – July 3, 1867) was the 19th Governor of Kentucky, serving from 1851 to 1855. He was later elected to represent Kentucky in the U.S. Senate from 1859 to 1865.

The reforms enacted during Powell's term ...

of Kentucky began to speak, yielding for a motion to adjourn from William Alexander Richardson

William Alexander Richardson (January 16, 1811 – December 27, 1875) was a prominent Illinois Democratic politician before and during the American Civil War.

Born near Lexington, Kentucky, Richardson attended Transylvania University, and th ...

of Illinois forty minutes later, which was also defeated, 5–30. Powell continued to speak, entertaining some hostile questions from Edgar Cowan

Edgar Cowan (September 19, 1815August 31, 1885) was an American lawyer and Republican politician from Greensburg, Pennsylvania. He represented Pennsylvania in the United States Senate during the American Civil War.

A native of Sewickley Towns ...

of Pennsylvania which provoked further discussion, but retaining control of the floor. At seven minutes past two in the morning, James A. Bayard Jr.

James Asheton Bayard Jr. (November 15, 1799 – June 13, 1880) was an American lawyer and politician from Delaware. He was a member of the Democratic Party and served as U.S. Senator from Delaware.

Early life

Bayard was born in Wilmington, ...

, of Delaware motioned to adjourn, the motion again failing, 4–35, and Powell retained control of the floor. Powell yielded the floor to Bayard, who then began to speak. At some point later, Powell made a motion to adjourn, but Bayard apparently had not yielded to him for that motion. When this was pointed out, Powell told Bayard to sit down so he could make the motion, assuming that Bayard would retain control of the floor if the motion failed, as it did, 4–33. The presiding officer, Samuel C. Pomeroy

Samuel Clarke Pomeroy (January 3, 1816 – August 27, 1891) was a United States senator from Kansas in the mid-19th century. He served in the United States Senate during the American Civil War. Pomeroy also served in the Massachusetts House of ...

of Kansas, immediately called the question of concurring in the report of the conference committee and declared that the ayes had it, and Trumbull immediately moved that the Senate move on to other business, which motion was agreed to. The Democrats objected that Bayard still had the floor, that he had merely yielded it for a motion to adjourn, but Pomeroy said he had no record of why Bayard had yielded the floor, meaning the floor was open once Powell's motion to adjourn had failed, meaning that the presiding officer was free to call the question. In this way, the bill cleared the Senate.

The next day, Senate Democrats protested the manner in which the bill had passed. During the ensuring discussion, the president pro tempore

A president pro tempore or speaker pro tempore is a constitutionally recognized officer of a legislative body who presides over the chamber in the absence of the normal presiding officer. The phrase '' pro tempore'' is Latin "for the time being". ...

asked permission "to sign a large number of enrolled bills", among which was the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act. The House had already been informed that the Senate had passed the bill, and the engrossed bills were sent to the president, who immediately signed the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act into law.

Provisions

The Act allowed the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus so long as the Civil War was ongoing.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 1. Normally, a judge would issue a writ of habeas corpus to compel a jailer to state the reason for holding a particular prisoner and, if the judge was not satisfied that the prisoner was being held lawfully, could release him. As a result of the Act, the jailer could now reply that a prisoner was held under the authority of the president and this response would suspend further proceedings in the case until the president lifted the suspension of habeas corpus or the Civil War ended.

The Act also provided for the release of prisoners in a section originally authored by Maryland Congressman

The Act allowed the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus so long as the Civil War was ongoing.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 1. Normally, a judge would issue a writ of habeas corpus to compel a jailer to state the reason for holding a particular prisoner and, if the judge was not satisfied that the prisoner was being held lawfully, could release him. As a result of the Act, the jailer could now reply that a prisoner was held under the authority of the president and this response would suspend further proceedings in the case until the president lifted the suspension of habeas corpus or the Civil War ended.

The Act also provided for the release of prisoners in a section originally authored by Maryland Congressman Henry May Henry May may refer to:

* Henry May (American politician) (1816–1866), U.S. Representative from Maryland

* Henry May (New Zealand politician) (1912–1995), New Zealand politician

* Henry May (VC) (1885–1941), Scottish recipient of the Victoria ...

, who had been arrested without recourse to habeas in 1861, while serving in Congress. It required the secretaries of State

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

and War

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

to provide the judges of the federal district

A district is a type of administrative division that, in some countries, is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivision ...

and circuit courts with a list of every person who was held as a state or political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although nu ...

and not as a prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of ...

wherever the federal courts were still operational.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 2. If the secretaries did not include a prisoner on the list, the judge was ordered to free them. If a grand jury

A grand jury is a jury—a group of citizens—empowered by law to conduct legal proceedings, investigate potential criminal conduct, and determine whether criminal charges should be brought. A grand jury may subpoena physical evidence or a p ...

failed to indict

An indictment ( ) is a formal accusation that a person has committed a crime. In jurisdictions that use the concept of felonies, the most serious criminal offence is a felony; jurisdictions that do not use the felonies concept often use that of an ...

anyone on the list before the end of its session, that prisoner was to be released, so long as they took an oath of allegiance and swore that they would not aid the rebellion. Judges could, if they concluded that the public safety required it, set bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

before releasing such unindicted prisoners. If the grand jury did indict a prisoner, that person could still be set free on bail

Bail is a set of pre-trial restrictions that are imposed on a suspect to ensure that they will not hamper the judicial process. Bail is the conditional release of a defendant with the promise to appear in court when required.

In some countrie ...

if they were charged with a crime that in peacetime would ordinarily make them eligible for bail.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 3. These provisions for those held as "political prisoners", as Henry May felt he had been, were first proposed by Congressman May in a bill in March 1862.

The Act further restricted how and why military and civilian officials could be sued. Anyone acting in an official capacity could not be convicted for false arrest

False arrest, Unlawful arrest or Wrongful arrest is a common law tort, where a plaintiff alleges they were held in custody without probable cause, or without an order issued by a court of competent jurisdiction. Although it is possible to sue ...

, false imprisonment

False imprisonment or unlawful imprisonment occurs when a person intentionally restricts another person’s movement within any area without legal authority, justification, or the restrained person's permission. Actual physical restraint is ...

, trespass

Trespass is an area of tort law broadly divided into three groups: trespass to the person, trespass to chattels, and trespass to land.

Trespass to the person historically involved six separate trespasses: threats, assault, battery, woundi ...

ing, or any crime related to a search and seizure

Search and seizure is a procedure used in many civil law and common law legal systems by which police or other authorities and their agents, who, suspecting that a crime has been committed, commence a search of a person's property and confisca ...

; this applied to actions done under Lincoln's prior suspensions of habeas corpus as well as future ones.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 4. If anyone brought a suit against a civilian or military official in any state court, or if state prosecutors went after them, the official could request that the trial instead take place in the (friendlier) federal court system.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 5. Moreover, if the official won the case, they could collect double in damages

At common law, damages are a remedy in the form of a monetary award to be paid to a claimant as compensation for loss or injury. To warrant the award, the claimant must show that a breach of duty has caused foreseeable loss. To be recognised at ...

from the plaintiff

A plaintiff ( Π in legal shorthand) is the party who initiates a lawsuit (also known as an ''action'') before a court. By doing so, the plaintiff seeks a legal remedy. If this search is successful, the court will issue judgment in favor of t ...

. Any case could be appeal

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

ed to the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

on a writ of error

In law, an appeal is the process in which cases are reviewed by a higher authority, where parties request a formal change to an official decision. Appeals function both as a process for error correction as well as a process of clarifying and ...

.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 6. Any suits to be brought against civilian or military officials had to be brought within two years of the arrest or the passage of the Act, whichever was later.Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, , sec. 7.

Aftermath

President Lincoln used the authority granted him under the Act on September 15, 1863, to suspend habeas corpus throughout the Union in any case involvingprisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

, spies, traitors

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

, or any member of the military. He subsequently both suspended habeas corpus and imposed martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

in Kentucky on July 5, 1864. An objection was made to the Act that it did not itself suspend the writ of habeas corpus but instead conferred that authority upon the president, and that the Act therefore violated the nondelegation doctrine

The doctrine of nondelegation (or non-delegation principle) is the theory that one branch of government must not authorize another entity to exercise the power or function which it is constitutionally authorized to exercise itself. It is explicit ...

prohibiting Congress from transferring its legislative authority, but no court adopted that view. Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a De ...

restored civilian courts to Kentucky in October, 1865, and revoked the suspension of habeas corpus in states and territories that had not joined the rebellion on December 1 later that year. At least one court had already ruled that the authority of the president to suspend the privilege of the writ had expired with the end of the rebellion a year and a half earlier.

One of those arrested while habeas corpus was suspended was Lambdin P. Milligan. Milligan was arrested in Indiana on October 5, 1864, for conspiring with four others to steal weapons and invade Union prisoner-of-war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war ...

camps to release Confederate prisoners. They were tried before a military tribunal

Military justice (also military law) is the legal system (bodies of law and procedure) that governs the conduct of the active-duty personnel of the armed forces of a country. In some nation-states, civil law and military law are distinct bod ...

, found guilty, and sentenced to hang. In '' ex parte Milligan'', the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

held that the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act did not authorize military tribunals, that as a matter of constitutional law

Constitutional law is a body of law which defines the role, powers, and structure of different entities within a state, namely, the executive, the parliament or legislature, and the judiciary; as well as the basic rights of citizens and, in fe ...

the suspension of habeas corpus did not itself authorize trial by military tribunals, and that neither the Act nor the laws of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war ('' jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territ ...

permitted the imposition of martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Martia ...

where civilian courts were open and operating unimpeded.

The Court had earlier avoided the questions arising in ''ex parte Milligan'' regarding the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act in a case concerning former Congressman and Ohio Copperhead politician Clement Vallandigham

Clement Laird Vallandigham ( ; July 29, 1820 – June 17, 1871) was an American politician and leader of the Copperhead faction of anti-war Democrats during the American Civil War. He served two terms for Ohio's 3rd congressional district in t ...

. General Ambrose E. Burnside

Ambrose Everett Burnside (May 23, 1824 – September 13, 1881) was an American army officer and politician who became a senior Union general in the Civil War and three times Governor of Rhode Island, as well as being a successful inventor ...

had him arrested in May 1863 claiming his anti-Lincoln and anti-war speeches continued to give aid to the enemy after his having been warned to cease doing so. Vallandigham was tried by a military tribunal and sentenced to two years in a military prison. Lincoln quickly commuted his sentence to banishment to the Confederacy. Vallandigham appealed his sentence, arguing that the Enrollment Act

The Enrollment Act of 1863 (, enacted March 3, 1863) also known as the Civil War Military Draft Act, was an Act passed by the United States Congress during the American Civil War to provide fresh manpower for the Union Army. The Act was the firs ...

did not authorize his trial by a military tribunal rather than in ordinary civilian courts, that he was not ordinarily subject to court martial, and that General Burnside could not expand the jurisdiction of military courts on his own authority. The Supreme Court did not address the substance of Vallandigham's appeal, instead denying that it possessed the jurisdiction to review the proceedings of military tribunals upon a writ of habeas corpus without explicit congressional authorization. Vallandigham was subsequently deported to the South where he turned himself in for arrest as a Union citizen behind enemy lines and was placed in a Confederate prison.

Mary Elizabeth Jenkins Surratt (May 1823 – July 7, 1865) was an American boarding house owner who was convicted of taking part in the conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln. She was sentenced to death but her lawyers Clampitt and Aiken had not finished trying to save their client. On the morning of July 7, they asked a District of Columbia court for a writ of habeas corpus, arguing that the military tribunal had no jurisdiction over their client. The court issued the writ at 3 A.M., and it was served on General Winfield Scott Hancock. Hancock was ordered to produce Surratt by 10 A.M. General Hancock sent an aide to General John F. Hartranft, who commanded the Old Capitol Prison, ordering him not to admit any United States marshal (as this would prevent the marshal from serving a similar writ on Hartranft). President Johnson was informed that the court had issued the writ, and promptly cancelled it at 11:30 A.M. under the authority granted to him by the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act of 1863. General Hancock and United States Attorney General James Speed personally appeared in court and informed the judge of the cancellation of the writ. Mary Surratt was hanged, becoming the first woman executed by the United States federal government.

Because all of the provisions of the Act referred to the Civil War, they were rendered inoperative with the conclusion of the war and no longer remain in effect. The Habeas Corpus Act of 1867 partially restored habeas corpus, extending federal habeas corpus protection to anyone "restrained of his or her liberty in violation of the constitution, or of any treaty or law of the United States", while continuing to deny habeas relief to anyone who had already been arrested for a military offense or for aiding the Confederacy. The provisions for the release of prisoners were incorporated into the Civil Rights Act of 1871

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend ...

, which authorized the suspension of habeas corpus in order to break the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and Cat ...

. Congress strengthened the protections for officials sued for actions arising from the suspension of habeas corpus in 1866 and 1867. Its provisions were omitted from the Revised Statutes of the United States

The Revised Statutes of the United States (in citations, Rev. Stat.) was the first official codification of the Acts of Congress. It was enacted into law in 1874. The purpose of the ''Revised Statutes'' was to make it easier to research federal l ...

, the codification of federal legislation in effect as of 1873.''Revised Statutes of the United States

The Revised Statutes of the United States (in citations, Rev. Stat.) was the first official codification of the Acts of Congress. It was enacted into law in 1874. The purpose of the ''Revised Statutes'' was to make it easier to research federal l ...

'', Title 13, chap. 13; see also index under "Habeas Corpus", p1267

See also

*Habeas corpus in the United States

In United States law, ''habeas corpus'' () is a recourse challenging the reasons or conditions of a person's confinement under color of law. A petition for ''habeas corpus'' is filed with a court that has jurisdiction over the custodian, and ...

* Suspension clause

Article One of the United States Constitution establishes the legislative branch of the federal government, the United States Congress. Under Article One, Congress is a bicameral legislature consisting of the House of Representatives and the Sen ...

* '' United States ex rel. Murphy v. Porter''

Notes

References

* ''An Act amendatory of "An Act to amend an Act entitled, 'An Act relating to Habeas Corpus, and regulating Judicial Proceedings in certain cases,'" approved May eleventh, eighteen hundred and sixty-six'', (1867). * ''An Act to amend an Act entitled, "An Act relating to Habeas Corpus, and regulating Judicial Proceedings in certain cases," approved March third, eighteen hundred and sixty-three'', (1866). * Catton, Bruce (1961), ''The Coming Fury'', 1967 reprint, New York: Pocket Books, . *Civil Rights Act of 1871

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act, Third Ku Klux Klan Act, Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871, is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend ...

, (1871).

* ''The Congressional Globe

The ''Congressional Record'' is the official record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress, published by the United States Government Publishing Office and issued when Congress is in session. The Congressional Record Inde ...

: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the First Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress.'' Edited by John C. Rives. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Globe Office, 1861.

* ''The Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the Second Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress.'' Edited by John C. Rives. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Globe Office, 1862.

* ''The Congressional Globe: Containing the Debates and Proceedings of the Third Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress.'' Edited by John Rives. Washington, D.C.: Congressional Globe Office, 1863.

*

*

* ''Ex parte Milligan'', .

* ''Ex parte Vallandigham'', .

* Fehrenbacher, Don Edward (1978), '' The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics'', 2001 reprint, New York: Oxford.

* Goodwin, Doris. ''Team of Rivals''. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

* Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, (1863).

* Hurd, Rollin C. ''A Treatise on the Right of Personal Liberty and on the Writ of Habeas Corpus''. Revised with notes by Frank H. Hurd. Albany, 1876.

* Johnson, Andrew. Proclamation 146.

* Johnson, Andrew. Proclamation 148.

* Lincoln, Abraham. Amnesty to Political and State Prisoners.

* Lincoln, Abraham. Order to Suspend Habeas Corpus.

* Lincoln, Abraham. Order to Suspend Habeas Corpus.

* Lincoln, Abraham. Proclamation 94

* Lincoln, Abraham. Proclamation 104

* Lincoln, Abraham. Proclamation 113

* Lossing, Benson John (1866), ''Pictorial Field Book of the Civil War'', 1997 reprint, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

* Rehnquist, William H. ''All the Laws but One: Civil Liberties in Wartime''. New York: Alfred Knopf, 1998.

* ''Revised Statutes of the United States

The Revised Statutes of the United States (in citations, Rev. Stat.) was the first official codification of the Acts of Congress. It was enacted into law in 1874. The purpose of the ''Revised Statutes'' was to make it easier to research federal l ...

, Passed at the First Session of the Forty-Third Congress, 1873–'74''. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1878.

* Sellery, George Clarke. Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus as viewed by Congress

'. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin—Madison, 1907. * Wicek, William. "The Reconstruction of Federal Judicial Power, 1863–1875." ''American Journal of Legal History'' 13, no. 4 (October 1969): 333–63. * White, Jonathan W. (2011). ''Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman''. Baton Rouge: LSU Press. .

External links

Text of Act

Text of House Bill

Text of Senate Bill

{{American Civil War United States habeas corpus law Emergency laws in the United States United States federal legislation Politics of the American Civil War Political repression in the United States 1863 in American law