HMS Hermes (95) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

}

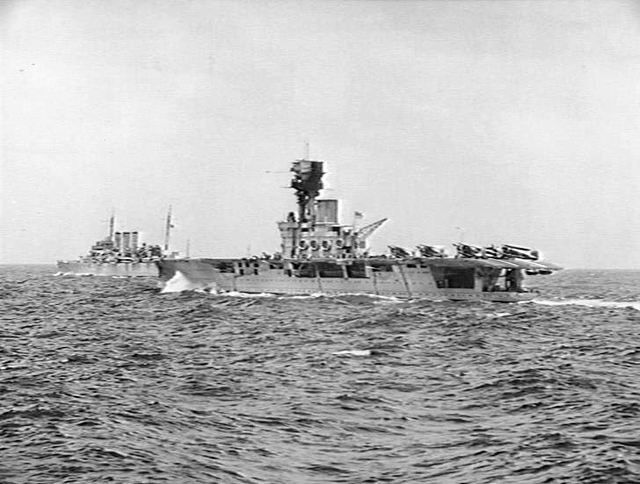

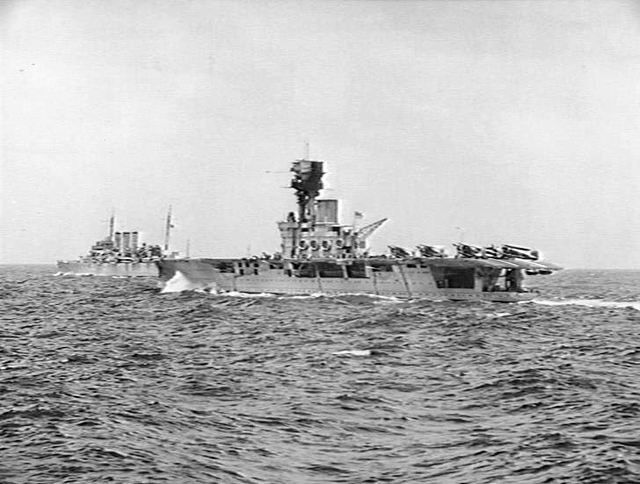

HMS ''Hermes'' was a British

''Hermes'' was laid down by Sir W. G. Armstrong-Whitworth and Company at

''Hermes'' was laid down by Sir W. G. Armstrong-Whitworth and Company at

The ship remained at Wei Hai Wei until the end of August when she sailed up the Yangtze River for

The ship remained at Wei Hai Wei until the end of August when she sailed up the Yangtze River for

Captain Richard F. J. Onslow relieved Captain Hutton on 25 May and ''Hermes'' continued her fruitless patrols. After returning from one such patrol on 29 June, the ship was ordered to leave harbour only nine hours after her arrival and to begin a blockade of Dakar as the Governor of French

Captain Richard F. J. Onslow relieved Captain Hutton on 25 May and ''Hermes'' continued her fruitless patrols. After returning from one such patrol on 29 June, the ship was ordered to leave harbour only nine hours after her arrival and to begin a blockade of Dakar as the Governor of French  On 22 February, the carrier was one of the ships tasked to search for ''Admiral Scheer'' after she was spotted by an aircraft from the light cruiser , but the pocket battleship successfully broke contact. ''Hermes'' arrived in Colombo,

On 22 February, the carrier was one of the ships tasked to search for ''Admiral Scheer'' after she was spotted by an aircraft from the light cruiser , but the pocket battleship successfully broke contact. ''Hermes'' arrived in Colombo,

The merchant ship SS ''Mamari III'' was converted to resemble ''Hermes'' as a decoy ship to confuse the Axis and was redesignated as '' Fleet Tender C''. On 4 June 1941, when she was sailing down the east coast of England to

The merchant ship SS ''Mamari III'' was converted to resemble ''Hermes'' as a decoy ship to confuse the Axis and was redesignated as '' Fleet Tender C''. On 4 June 1941, when she was sailing down the east coast of England to

Fleet Air Arm Archive

WW2DB: Hermes

* ttp://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80016112 IWM Interview with survivor Eric Monaghan

The Story of the SS ''Tungchow'' tod by a Survivor

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hermes (95) 1919 ships Aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy Aircraft carriers sunk by aircraft Maritime incidents in July 1940 Maritime incidents in April 1942 Ships built on the River Tyne World War II aircraft carriers of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Indian Ocean Ships sunk by Japanese aircraft Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Wreck diving sites

aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for Carrier-based aircraft, carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a ...

built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against ...

and was the world's first ship to be designed as an aircraft carrier, although the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

's was the first to be launched and commissioned. The ship's construction began during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fighti ...

, but she was not completed until after the end of the war, having been delayed by multiple changes in her design after she was laid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

. After she was launched, the Armstrong Whitworth

Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd was a major British manufacturing company of the early years of the 20th century. With headquarters in Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne, Armstrong Whitworth built armaments, ships, locomotives, automobiles and ...

shipyard which built her closed, and her fitting out was suspended. Most of the changes made were to optimise her design, in light of the results of experiments with operational carriers.

Finally commissioned in 1924, ''Hermes'' served briefly with the Atlantic Fleet before spending the bulk of her career assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between ...

and the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 18 ...

. In the Mediterranean, she worked with other carriers developing multi-carrier tactics. While showing the flag at the China Station, she helped to suppress piracy in Chinese waters. ''Hermes'' returned home in 1937 and was placed in reserve before becoming a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

in 1938.

When the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

began in September 1939, the ship was briefly assigned to the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the Firs ...

and conducted anti-submarine patrols in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

. She was transferred to Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 20 ...

in October to cooperate with the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

in hunting down German commerce raider

Commerce raiding (french: guerre de course, "war of the chase"; german: Handelskrieg, "trade war") is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than enga ...

s and blockade runner

A blockade runner is a merchant vessel used for evading a naval blockade of a port or strait. It is usually light and fast, using stealth and speed rather than confronting the blockaders in order to break the blockade. Blockade runners usual ...

s. Aside from a brief refit, ''Hermes'' remained there until the fall of France and the establishment of Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

at the end of June 1940. Supported by several cruisers, the ship then blockaded Dakar and attempted to sink the by exploding depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive hydraulic shock. Most depth charges use h ...

s underneath her stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

, as well as sending Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also used ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s to attack her at night. While returning from this mission, ''Hermes'' rammed a British armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

in a storm and required several months of repairs in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the Atlantic Ocean, South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the ...

, then resumed patrolling for Axis shipping in the South Atlantic and the Indian Ocean.

In February 1941, the ship supported Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. Historically, it has been synonymous with "republic". The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the ...

forces in Italian Somaliland

Italian Somalia ( it, Somalia Italiana; ar, الصومال الإيطالي, Al-Sumal Al-Italiy; so, Dhulka Talyaaniga ee Soomaalida), was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia. Ruled in the 19th centur ...

during the East African Campaign and did much the same two months later in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The body ...

during the Anglo-Iraqi War

The Anglo-Iraqi War was a British-led Allied military campaign during the Second World War against the Kingdom of Iraq under Rashid Gaylani, who had seized power in the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état, with assistance from Germany and Italy. The ca ...

. After that campaign, ''Hermes'' spent most of the rest of the year patrolling the Indian Ocean. She was refitted in South Africa between November 1941 and February 1942 and then joined the Eastern Fleet

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

* Eastern Air ...

at Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

.

''Hermes'' was berthed in Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

on 8 April when a warning of an Indian Ocean raid

The Indian Ocean raid, also known as Operation C or Battle of Ceylon in Japanese, was a naval sortie carried out by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) from 31 March to 10 April 1942. Japanese aircraft carriers under Admiral Chūichi Nagumo ...

by the Japanese fleet was received, and she sailed that day for the Maldives

Maldives (, ; dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖެ, translit=Dhivehi Raajje, ), officially the Republic of Maldives ( dv, ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ ޖުމްހޫރިއްޔާ, translit=Dhivehi Raajjeyge Jumhooriyyaa, label=none, ), is an archipela ...

with no aircraft on board. On 9 April a Japanese scout plane spotted her near Batticaloa

Batticaloa ( ta, மட்டக்களப்பு, ''Maṭṭakkaḷappu''; si, මඩකලපුව, ''Maḍakalapuwa'') is a major city in the Eastern Province, Sri Lanka, and its former capital. It is the administrative capital of the B ...

, and she was attacked by several dozen dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s shortly afterwards. With no air cover, the carrier was quickly sunk by the Japanese aircraft. Most of the survivors were rescued by a nearby hospital ship, although 307 men from ''Hermes'' were lost in the sinking.

Development

Like ''Hōshō'', ''Hermes'' was based on a cruiser-type hull and she was initially designed to carry both wheeled aircraft andseaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tec ...

s. The ship's design was derived from a 1916 seaplane carrier design by Gerard Holmes and Sir John Biles, but was considerably enlarged by Sir Eustace d'Eyncourt, the Director of Naval Construction

The Director of Naval Construction (DNC) also known as the Department of the Director of Naval Construction and Directorate of Naval Construction and originally known as the Chief Constructor of the Navy was a senior principal civil officer res ...

(DNC), in his April 1917 sketch design. Her most notable feature was the seaplane slipway

A slipway, also known as boat ramp or launch or boat deployer, is a ramp on the shore by which ships or boats can be moved to and from the water. They are used for building and repairing ships and boats, and for launching and retrieving small ...

that comprised three sections. The seaplanes would taxi onto the rigid submerged portion aft and dock with a trolley that would carry the aircraft into the hangar. A flexible submerged portion separated the rear section from the rigid forward portion of the slipway to prevent the submerged part from rolling with the ship's motion. The entire slipway could be retracted into the ship, and a gantry crane

A gantry crane is a crane built atop a gantry, which is a structure used to straddle an object or workspace. They can range from enormous "full" gantry cranes, capable of lifting some of the heaviest loads in the world, to small shop cranes, us ...

ran the length of the slipway to help recover the seaplanes. The design showed two islands

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

with the full-length flight deck

The flight deck of an aircraft carrier is the surface from which its aircraft take off and land, essentially a miniature airfield at sea. On smaller naval ships which do not have aviation as a primary mission, the landing area for helicopters ...

running between them. Each island contained one funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construc ...

; a large net could be strung between them to stop out-of-control aircraft. Aircraft were transported between the hangar and the flight deck by two aircraft lifts (elevators); the forward lift measured and the rear . This design displaced and accommodated six large Short Type 184

The Short Admiralty Type 184, often called the Short 225 after the power rating of the engine first fitted, was a British two-seat reconnaissance, bombing and torpedo carrying folding-wing seaplane designed by Horace Short of Short Brothers. It ...

seaplanes and six smaller Sopwith Baby

The Sopwith Baby is a British single-seat floatplane that was operated by the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) from 1915.

Development and design

The Baby (also known as the Admiralty 8200 Type) was a development of the two-seat Sopwith Schneide ...

seaplanes. The ship's armament consisted of six guns.

The DNC produced a detailed design in January 1918 that made some changes to his original sketch, including the addition of a rotating bow catapult

A catapult is a ballistic device used to launch a projectile a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden release of stored ...

to allow the ship to launch aircraft regardless of wind direction, and the ship was laid down that month to the revised design. Progress was slow, as most of the resources of the shipyard were being used to finish the conversion of from a battleship to an aircraft carrier. The leisurely pace of construction allowed for more time with which to rework the ship's design. By mid-June the slipway had been deleted from the design and the ship's armament had been revised to consist of eleven guns and only a single anti-aircraft gun. By this time, the uncertainty about the best configuration for an aircraft carrier had increased to the point that the Admiralty forbade the builder from working above the hangar deck without express permission. Later that year the ship's design was revised again to incorporate a single island, her lifts were changed to a uniform size of , and her armament was altered to ten 6-inch guns and four 4-inch anti-aircraft guns. These changes increased her displacement to .Friedman, p. 73

Construction was suspended after ''Hermes'' was launched in September 1919 as the Admiralty awaited the results of flight trials with ''Eagle'' and . Her design was modified in March 1920 with an island superstructure and funnel to starboard, and the forward catapult was removed.McCart, p. 11 The logic behind placing the island to starboard was that pilots generally preferred to turn to port when recovering from an aborted landing. A prominent tripod mast was added to house the fire-control system

A fire-control system (FCS) is a number of components working together, usually a gun data computer, a director, and radar, which is designed to assist a ranged weapon system to target, track, and hit a target. It performs the same task as a hu ...

s for her guns.

The last revisions were made to the ship's design in May 1921, after the trials with ''Argus'' and ''Eagle''. The lifts were moved further apart to allow for more space for the arresting gear and they were enlarged to allow the wings of her aircraft to be spread in the hangar. Her anti-ship armament was reduced to six guns and her flight deck was faired into the bow.

Description

''Hermes'' had anoverall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads ...

of , a beam of , and a draught of at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. She displaced at standard load. Each of the ship's two sets of Parsons geared steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

s drove one propeller shaft

A drive shaft, driveshaft, driving shaft, tailshaft (Australian English), propeller shaft (prop shaft), or Cardan shaft (after Girolamo Cardano) is a component for transmitting mechanical power and torque and rotation, usually used to connect ...

at a speed of . Steam was supplied by six Yarrow

''Achillea millefolium'', commonly known as yarrow () or common yarrow, is a flowering plant in the family Asteraceae. Other common names include old man's pepper, devil's nettle, sanguinary, milfoil, soldier's woundwort, and thousand seal.

T ...

boilers

A boiler is a closed vessel in which fluid (generally water) is heated. The fluid does not necessarily boil. The heated or vaporized fluid exits the boiler for use in various processes or heating applications, including water heating, central h ...

Preston, p. 71 operating at a pressure of . The turbines were designed for a total of , but they produced during her sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s, giving ''Hermes'' a speed of . The ship carried of fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

which gave her a range of at .

The ship's flight deck was long and her lifts' dimensions were . Her hangar

A hangar is a building or structure designed to hold aircraft or spacecraft. Hangars are built of metal, wood, or concrete. The word ''hangar'' comes from Middle French ''hanghart'' ("enclosure near a house"), of Germanic origin, from Frankish ...

was long, wide and high. ''Hermes'' was fitted with longitudinal arresting gear. A large crane was positioned behind the island. Because of her size, the ship was able to carry only about 20 aircraft. Bulk petrol

Gasoline (; ) or petrol (; ) (see ) is a transparent, petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines (also known as petrol engines). It consists mostly of organic c ...

storage consisted of . The ship's crew totalled 33 officers and 533 men, exclusive of the air group, in 1939.

For self-defence against enemy warships, ''Hermes'' had six BL 5.5-inch Mk I guns, three on each side of the ship. All three of her QF Mk V 4-inch anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

guns were positioned on the flight deck. The ship's waterline belt armour was thick and her flight deck, which was also the ship's strength deck, was thick. ''Hermes'' had a metacentric height

The metacentric height (GM) is a measurement of the initial static stability of a floating body. It is calculated as the distance between the centre of gravity of a ship and its metacentre. A larger metacentric height implies greater initial stab ...

of and handled well in heavy weather. However, she had quite a large surface area exposed to the wind and required as much as 25 to 30 degrees of weather helm Weather helm is the tendency of sailing vessels to turn towards the source of wind, creating an unbalanced helm that requires pulling the tiller to windward (i.e. 'to weather') in order to counteract the effect.

Weather helm is the opposite of ...

at low speed when the wind was blowing from the side.

Service

''Hermes'' was laid down by Sir W. G. Armstrong-Whitworth and Company at

''Hermes'' was laid down by Sir W. G. Armstrong-Whitworth and Company at Walker

Walker or The Walker may refer to:

People

*Walker (given name)

* Walker (surname)

* Walker (Brazilian footballer) (born 1982), Brazilian footballer

Places

In the United States

* Walker, Arizona, in Yavapai County

* Walker, Mono County, Californ ...

on the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden Rock near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The Meeting of the Water ...

on 15 January 1918 as the world's first purpose-designed aircraft carrier, and was launched on 11 September 1919. She was christened by Mrs. A. Cooper, daughter of the First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, Walter Long. The shipyard was scheduled to close at the end of 1919 and the Admiralty ordered the ship towed to Devonport, where she arrived in January 1920 for completion.

1920s

Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Arthur Stopford was appointed as the ship's commanding officer in February 1923 and the ship began her sea trials in August. After fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

, ''Hermes'' was commissioned on 19 February 1924 and later assigned to the Atlantic Fleet. She conducted flying trials with the Fairey IIID reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmishers ...

biplanes

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While a ...

for the next several months. ''Hermes'' participated in the fleet review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

conducted by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Quee ...

on 26 July in Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshir ...

. Afterwards she was refitted until November and then transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet. She arrived at Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

on 22 November and needed some repairs to fix storm damage suffered en route. At this time the ship embarked No. 403 Flight with Fairey Flycatcher

The Fairey Flycatcher was a British single-seat biplane carrier-borne fighter aircraft made by Fairey Aviation Company which served from 1923 to 1934. It was produced with a conventional undercarriage for carrier use, although this could be ex ...

fighters

Fighter(s) or The Fighter(s) may refer to:

Combat and warfare

* Combatant, an individual legally entitled to engage in hostilities during an international armed conflict

* Fighter aircraft, a warplane designed to destroy or damage enemy warplanes ...

and 441 Flight with Fairey IIIDs. ''Hermes'' conducted flying exercises with ''Eagle'' and the rest of the Mediterranean Fleet in early 1925 before she began a seven-week refit in Malta on 27 March, then sailed for Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dense ...

where she arrived on 29 May after her aircraft had flown ashore.

''Hermes'' sailed for the China Station on 17 June with 403 and 441 Flights aboard, but made a lengthy pause en route in the Mediterranean during which Captain Stopford was replaced by Captain C. P. Talbot. She arrived at Hong Kong

Hong Kong ( (US) or (UK); , ), officially the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China ( abbr. Hong Kong SAR or HKSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China on the eastern Pearl River Delta ...

on 10 August 1925. The ship made her first foreign port visit to Amoy

Xiamen ( , ; ), also known as Amoy (, from Hokkien pronunciation ), is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Strait. It is divided into six districts: Huli, Siming, Jimei, Tong'an, ...

in November. ''Hermes'' returned to the Mediterranean in early 1926 and was refitted at Malta between April and June. 441 Flight was transferred to ''Eagle'' at this time in exchange for 440 Flight which flew aboard in September. 442 Flight also joined the ship at this time; both flights were equipped with Fairey IIIs. The ship exercised with the Mediterranean Fleet after her refit was completed and Captain R. Elliot relieved Captain Talbot on 14 August. ''Hermes'' returned to Hong Kong on 11 October and conducted routine training until she sailed to the naval base at Wei Hai Wei on 27 July 1927 to escape the summer heat. The ship rendezvoused in September with ''Argus'', which was to replace her on the China Station. Before she departed the area, however, both ships attacked the pirate base at Bias Bay

Daya Bay (), formerly known as Bias Bay, is a bay of the South China Sea on the south coast of Guangdong Province in China. It is bordered by Shenzhen's Dapeng Peninsula to the west and Huizhou to the north and east.

History

The bay was a hideou ...

and their fleet of junks

A junk (Chinese: 船, ''chuán'') is a type of Chinese sailing ship with fully battened sails. There are two types of junk in China: northern junk, which developed from Chinese river boats, and southern junk, which developed from Austronesian ...

and sampan

A sampan is a relatively flat-bottomed Chinese and Malay wooden boat. Some sampans include a small shelter on board and may be used as a permanent habitation on inland waters. The design closely resembles Western hard chine boats like t ...

s. ''Hermes'' reached the United Kingdom on 26 October and began a refit at Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham (at its most extensive, in the early 20th centur ...

at the beginning of November. One of her 4-inch guns was removed at this time. Sometime after this refit, the ship was provided with two single 2-pounder "pom-pom" AA guns.Friedman, p. 89

Captain Eliot was relieved by Captain G. Hopwood on 2 December and the ship sailed for the China Station on 21 January 1928. The Fairey IIIDs of 440 Flight had been replaced by IIIFs, and the ship kept the same three flights for this deployment. En route to Hong Kong, ''Hermes'' stopped at Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estimated populatio ...

, Siam

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

, in March for four days and was inspected by King Rama VII

Prajadhipok ( th, ประชาธิปก, RTGS: ''Prachathipok'', 8 November 1893 – 30 May 1941), also Rama VII, was the seventh monarch of Siam of the Chakri dynasty. His reign was a turbulent time for Siam due to political an ...

. She reached Hong Kong on 18 March, relieving ''Argus''. The ship spent a month in the port of Chefoo

Yantai, formerly known as Chefoo, is a coastal prefecture-level city on the Shandong Peninsula in northeastern Shandong province of People's Republic of China. Lying on the southern coast of the Bohai Strait, Yantai borders Qingdao on the ...

in May and then the following three weeks in Wei Hai Wei. While visiting Chinwangtao in July, one of her Fairey IIIF seaplanes made a forced landing outside the port; the rescued the pilot and towed the aircraft back to the carrier. During the rest of the year, the ship visited Shanghai

Shanghai (; , , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ) is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of the People's Republic of China (PRC). The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowin ...

, Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is highly urbanized and, as of 2019, was the world's most densely populated ...

, as well as Kudat

Kudat ( ms, Pekan Kudat) is the capital of the Kudat District in the Kudat Division of Sabah, Malaysia. Its population was estimated to be around 29,025 in 2010. It is located on the Kudat Peninsula, about north of Kota Kinabalu, the state c ...

and Jesselton

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = From top, left to right, bottom:Kota Kinabalu skyline, Wawasan intersection, Tun Mustapha Tower, Kota Kinabalu Coastal Highway, the Kota Kinabalu City Mosque, the Wism ...

in Borneo

Borneo (; id, Kalimantan) is the third-largest island in the world and the largest in Asia. At the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, in relation to major Indonesian islands, it is located north of Java, west of Sulawesi, and ea ...

. She began a refit in Hong Kong in January 1929 and Captain J. D. Campbell assumed command on 28 March. After refit was completed in April,'' Hermes'' conducted flying training before sailing up the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

to visit Nanking

Nanjing (; , Mandarin pronunciation: ), alternately romanized as Nanking, is the capital of Jiangsu province of the People's Republic of China. It is a sub-provincial city, a megacity, and the second largest city in the East China region. T ...

the following month. Afterwards she spent the next four months at Wei Hei Wei. She made visits to Tsingtao

Qingdao (, also spelled Tsingtao; , Mandarin: ) is a major city in eastern Shandong Province. The city's name in Chinese characters literally means "azure island". Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, it is a major nodal city of the One Belt ...

and Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

before returning to Hong Kong on 29 October where she remained for the rest of the year.

1930s

On 28 January 1930, ''Hermes'' transported the British Minister to China, SirMiles Lampson

Miles Wedderburn Lampson, 1st Baron Killearn, (24 August 1880 – 18 September 1964) was a British diplomat.

Background and education

Miles Lampson was the son of Norman Lampson, and grandson of Sir Curtis Lampson, 1st Baronet. His mothe ...

, to Nanking for talks with the Chinese Government

The Government of the People's Republic of China () is an authoritarian political system in the People's Republic of China under the exclusive political leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It consists of legislative, executive, mili ...

over the Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded Manchuria on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden Incident. At the war's end in February 1932, the Japanese established the puppet state of Manchukuo. Their occupation lasted until the ...

and she remained there until she sailed downriver to Shanghai on 2 March. By the end of the month, the carrier was back in Hong Kong and remained there until June when she returned to Wei Hai Wei for her annual summer visit. The ship briefly returned to Hong Kong before departing for Great Britain on 7 August. ''Hermes'' reached Portsmouth on 23 September, but remained there only six days before transferring to Sheerness

Sheerness () is a town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 11,938, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby town ...

. Captain E. J. G. MacKinnon relieved Captain Campbell there on 2 October. She was given a brief refit at Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham (at its most extensive, in the early 20th centur ...

before sailing for the China Station. The ship had aboard only 403 and 440 Flights on this deployment and transported six Blackburn Ripon

The Blackburn T.5 Ripon was a carrier-based torpedo bomber and reconnaissance biplane designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Blackburn Aircraft. It was the basis for both the license-produced Mitsubishi B2M and the improve ...

s to deliver to Malta and HMS ''Eagle''. Hermes departed Portsmouth on 12 November and reached Hong Kong on 2 January 1931. En route to her summer refuge at Wei Hai Wei, the ship received a report on 9 June that the submarine had been sunk there while on exercise. Captain MacKinnon took command of the rescue effort when ''Hermes'' arrived at the accident site an hour afterwards. Eight of the submarine's crewmen managed to escape through the forward torpedo hatch, but only six of those reached the surface where they were picked up and treated in ''Hermes''s sickbay

A sick bay is a compartment in a ship, or a section of another organisation, such as a school or college, used for medical purposes.

The sick bay contains the ship's medicine chest, which may be divided into separate cabinets, such as a refrigera ...

; two of those six subsequently died.

The ship remained at Wei Hai Wei until the end of August when she sailed up the Yangtze River for

The ship remained at Wei Hai Wei until the end of August when she sailed up the Yangtze River for Hankow

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers whe ...

. She reached the inland port on 5 September and dispatched armed guards to put down unrest on several British-owned merchant ships. Her primary purpose, though, was to aid the Chinese government's survey of the massive flooding in the area. Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance ...

and his wife, Anne Morrow Lindbergh

Anne Spencer Morrow Lindbergh (June 22, 1906 – February 7, 2001) was an American writer and aviator. She was the wife of decorated pioneer aviator Charles Lindbergh, with whom she made many exploratory flights.

Raised in Englewood, New Jerse ...

, were also in the city to survey the flooding with their Lockheed Sirius float-plane and they were invited to use the carrier as their base. Unfortunately, their aircraft was flipped on the morning of 2 October by a strong current as it was being hoisted back into the water by ''Hermes''s crane. They were quickly rescued by a boat from the carrier, but their aircraft was damaged. Captain MacKinnon offered to take them and their aircraft to Shanghai where it could be repaired and the ship departed the next day. She remained in Shanghai until 2 November, when she sailed for Hong Kong. ''Hermes'' received a distress message on 3 November from a Japanese merchantman, SS ''Ryinjin Maru'', that had run aground on the Tan Rocks near the Chinese mainland at the mouth of the Taiwan Strait

The Taiwan Strait is a -wide strait separating the island of Taiwan and continental Asia. The strait is part of the South China Sea and connects to the East China Sea to the north. The narrowest part is wide.

The Taiwan Strait is itself a ...

. The ship managed to rescue nine crew members before she was relieved by the and could proceed to Hong Kong. She reached the city on 7 November and remained in the area until April 1932.

Captain MacKinnon took sick the next month and he was relieved by Captain W. B. Mackenzie on 25 February. After a short refit, the carrier, escorted by the destroyer ''Whitehall

Whitehall is a road and area in the City of Westminster, Central London. The road forms the first part of the A3212 road from Trafalgar Square to Chelsea. It is the main thoroughfare running south from Trafalgar Square towards Parliament Squ ...

'', made a brief visit to Amoy in late April before sailing for Wei Hai Wei where she stayed until 17 September. On that day, ''Hermes'' sailed for the Japanese city of Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the Na ...

and then spent four weeks in Shanghai. The ship did not return to Hong Kong until 28 October and spent the next few months there. In January 1933, the carrier visited the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

for several weeks before returning to Hong Kong where she was given a brief refit. After short visits to Tsingtao and Wei Hai Wei, ''Hermes'' departed Hong Kong in mid-June for Great Britain. She reached Sheerness on 22 July, but the ship was transferred shortly afterwards to Chatham Dockyard and opened to the public during Navy Week in early August. She sailed the next month for Devonport Dockyard for a thorough refit. Transverse arresting gear was fitted and her machinery was thoroughly overhauled. Sometime in 1932, the two single 2-pounders were replaced by two quadruple .50-calibre Mark III machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, rifled autoloading firearm designed for sustained direct fire with rifle cartridges. Other automatic firearms such as automatic shotguns and automatic rifles (including assault rifles and battle rifles ...

mounts.

Captain the Honourable G. Fraser was appointed on 15 August 1934 as the new commanding officer and the ship began trials of the new equipment in early November.McCart, p. 32 At the same time the nine Fairey Seal

The Fairey Seal was a British carrier-borne spotter-reconnaissance aircraft, operated in the 1930s. The Seal was derived – like the Gordon – from the IIIF. To enable the Fairey Seal to be launched by catapult from warships, it could be fi ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s of 824 Squadron joined the ship. ''Hermes'' left Portsmouth on 18 November for the China Station and arrived at Hong Kong on 4 January 1935. The Hawker Osprey reconnaissance biplanes of 803 Squadron were transferred aboard from ''Eagle'' before that ship left Hong Kong. Pirates captured a British-owned merchant ship, SS ''Tungchow'', with 90 British and American children on board on 29 January and ''Hermes'' was ordered to search for the ship when she failed to arrive at Chefoo at her scheduled time. Three Seals spotted her in Bias Bay on 1 February and the pirates abandoned the ship when it was found, leaving the passengers unharmed. ''Hermes'' remained in the vicinity of Hong Kong until mid-May when she steamed to Wei Hai Wei. There she remained until 12 September when the Admiralty decided to transfer her to Singapore where she was closer to East Africa in case a military response to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia was deemed necessary. The ship arrived on 19 September and remained in the area for the next five months.

The ship's aircraft were detailed to search for the missing '' Lady Southern Cross'' of Sir Charles Kingsford Smith

Sir Charles Edward Kingsford Smith (9 February 18978 November 1935), nicknamed Smithy, was an Australian aviation pioneer. He piloted the first transpacific flight and the first flight between Australia and New Zealand.

Kingsford Smith was b ...

when it failed to arrive at Singapore on 8 November during an attempt to set a new speed record between Britain and Australia. No sign was found of either the aircraft or its crew despite a month-long search. ''Hermes'' returned to Hong Kong at the beginning of March 1936 before beginning a tour of Japan on 21 April, escorted by the destroyers and . She summered at Wei Hai Wei and did not return to Hong Kong until the end of October. For most of January 1937, the carrier, accompanied by the heavy cruiser

The heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in caliber, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Tr ...

and the destroyers ''Duncan'' and , toured the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies ( nl, Nederlands(ch)-Indië; ), was a Dutch colony consisting of what is now Indonesia. It was formed from the nationalised trading posts of the Dutch East India Company, which ...

. The ship's torpedo bombers practised torpedo attacks on the cruisers and ''Dorsetshire'' in February, working with the Royal Air Force's torpedo bombers based at RAF Seletar, Singapore. ''Hermes'' left Singapore on 17 March, leaving 803 Squadron behind, and reached Plymouth on 3 May 1937. Following the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead on 20 May for King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until his death in 1952. He was also the last Emperor of Indi ...

, she was assigned to the Reserve Fleet

A reserve fleet is a collection of naval vessels of all types that are fully equipped for service but are not currently needed; they are partially or fully decommissioned. A reserve fleet is informally said to be "in mothballs" or "mothballed"; a ...

. On 16 July 1938, ''Hermes'' was transferred from the Reserve Fleet and became a training ship at Devonport.

Plans were made in 1937 to replace ''Hermes''s three single 4-inch guns with two twin 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, one forward and another aft of the island, as well as two octuple 2-pounder mounts. A single High-Angle Control System would have been fitted to control these guns, but the dockyard was overwhelmed with other work and couldn't begin to design the changes until July 1938. They were scheduled to be installed between September and December 1939, but the beginning of the war intervened and nothing was done. The ship's petrol storage was to be increased to in April 1940, but this also does not seem to have occurred.

World War II

The ship was given a brief refit in early August 1939 and Captain F. E. P. Hutton assumed command on 23 August. She was recommissioned the following day, and 12 Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers of 814 Squadron flew aboard on 1 September. ''Hermes'' conductedanti-submarine

An anti-submarine weapon (ASW) is any one of a number of devices that are intended to act against a submarine and its crew, to destroy (sink) the vessel or reduce its capability as a weapon of war. In its simplest sense, an anti-submarine weapo ...

patrols in mid-September in an effort to find and destroy U-boats in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

. On 18 September, the day after the fleet carrier was sunk on one such patrol, ''Hermes'' located a submarine, but attacks by her escorting destroyers, and , were ineffective. The carrier was then ordered to return to Devonport where she was fitted with degaussing

Degaussing is the process of decreasing or eliminating a remnant magnetic field. It is named after the gauss, a unit of magnetism, which in turn was named after Carl Friedrich Gauss. Due to magnetic hysteresis, it is generally not possible to redu ...

gear during another brief refit. On 7 October, the ship rendezvoused with the and they arrived at Dakar in French West Africa

French West Africa (french: Afrique-Occidentale française, ) was a federation of eight French colonial territories in West Africa: Mauritania, Senegal, French Sudan (now Mali), French Guinea (now Guinea), Ivory Coast, Upper Volta (now Burkin ...

on 16 October. Designated as Force X, they began searching for German ships in the Atlantic on 25 October. ''Hermes'' performed these patrols with no sightings until the end of December when she escorted a convoy to Britain where she could be refitted from 9 January to 10 February 1940; the ship then returned to Dakar and resumed her patrols for German commerce raiders and blockade runners.

Captain Richard F. J. Onslow relieved Captain Hutton on 25 May and ''Hermes'' continued her fruitless patrols. After returning from one such patrol on 29 June, the ship was ordered to leave harbour only nine hours after her arrival and to begin a blockade of Dakar as the Governor of French

Captain Richard F. J. Onslow relieved Captain Hutton on 25 May and ''Hermes'' continued her fruitless patrols. After returning from one such patrol on 29 June, the ship was ordered to leave harbour only nine hours after her arrival and to begin a blockade of Dakar as the Governor of French Senegal

Senegal,; Wolof: ''Senegaal''; Pulaar: 𞤅𞤫𞤲𞤫𞤺𞤢𞥄𞤤𞤭 (Senegaali); Arabic: السنغال ''As-Sinighal'') officially the Republic of Senegal,; Wolof: ''Réewum Senegaal''; Pulaar : 𞤈𞤫𞤲𞤣𞤢𞥄𞤲𞤣� ...

had declared the colony's allegiance to the Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

regime. On the night of 7/8 July, a boat from ''Hermes'' attempted to drop four depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon. It is intended to destroy a submarine by being dropped into the water nearby and detonating, subjecting the target to a powerful and destructive hydraulic shock. Most depth charges use h ...

s underneath the French battleship ''Richelieu'''s stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. Ori ...

in conjunction with a torpedo attack by the Swordfish of 814 Squadron. The boat was successful in reaching the French ship, but the depth charges failed to detonate. The torpedo attack was more successful as one of the battleship's propellers was damaged. French aircraft attacked the British forces several times in retaliation, but without success. While returning to Freetown after the attack, ''Hermes'' accidentally rammed the armed merchant cruiser HMS ''Corfu'' during a rainstorm in the dark on 10 July. The impact injured three of the carrier's crew, one of whom subsequently died of his injuries, but no one from ''Corfu''s crew was injured. The two ships were locked together so that ''Corfu''s crew could walk from one to the other when Captain Onslow ordered most of her crew to be evacuated onto ''Hermes''. They were pulled apart by a combination of the carrier's turbines at full speed astern and blowing of ballast tank

A ballast tank is a compartment within a boat, ship or other floating structure that holds water, which is used as ballast to provide hydrostatic stability for a vessel, to reduce or control buoyancy, as in a submarine, to correct trim or li ...

s on board ''Corfu'' to lighten that ship forward. ''Hermes'' had crumpled the forward of her bow, mostly above water, and was able to proceed to Freetown at , but ''Corfu'' had to be towed stern first to Freetown where she arrived three days later. The carrier joined a convoy to South Africa on 5 August and began repairs at Simonstown 12 days later. The repairs were completed on 2 November and the ship arrived back at Freetown on 29 November after working up.

The ship was joined by the light cruiser on 2 December to search for German commerce raiders in the South Atlantic. They mostly operated from Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

during the month and were later joined by the armed merchant cruiser to search for the pocket battleship

The ''Deutschland'' class was a series of three ''Panzerschiffe'' (armored ships), a form of heavily armed cruiser, built by the ''Reichsmarine'' officially in accordance with restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. The ships of the cl ...

, without success. The force sailed for Simonstown on 31 December and ''Hermes'' was dispatched to search off the South African coast for Vichy French blockade runners. One such ship was spotted on 26 January, but she returned to Madagascar. On 4 February, the ship headed north to rendezvous with the heavy cruisers and to blockade the Somali port of Kismayo

Kismayo ( so, Kismaayo, Maay: ''Kismanyy'', ar, كيسمايو, ; it, Chisimaio) is a port city in the southern Lower Juba (Jubbada Hoose) province of Somalia. It is the commercial capital of the autonomous Jubaland region.

The city is situa ...

which was under siege by Commonwealth forces. ''Hawkins'' captured three Italian merchantmen and ''Hermes'' captured one on 12 February.

On 22 February, the carrier was one of the ships tasked to search for ''Admiral Scheer'' after she was spotted by an aircraft from the light cruiser , but the pocket battleship successfully broke contact. ''Hermes'' arrived in Colombo,

On 22 February, the carrier was one of the ships tasked to search for ''Admiral Scheer'' after she was spotted by an aircraft from the light cruiser , but the pocket battleship successfully broke contact. ''Hermes'' arrived in Colombo, Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, on 4 March and continued to search for Axis shipping. She was sent to the Persian Gulf in April to support British operations in Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

, Iraq, and remained there until mid-June when she returned to patrolling the Indian Ocean between Ceylon and the Seychelles Islands

Seychelles (, ; ), officially the Republic of Seychelles (french: link=no, République des Seychelles; Creole: ''La Repiblik Sesel''), is an archipelagic state consisting of 115 islands in the Indian Ocean. Its capital and largest city, ...

. The ship continued to patrol until 19 November when she arrived in Simonstown for a refit that was not completed until 31 January 1942. ''Hermes'' was assigned to the Eastern Fleet and arrived at Colombo on 14 February. She put to sea on 19 February to receive the Swordfish of 814 Squadron and to rendezvous with the destroyer to conduct an anti-submarine patrol. The squadron was disembarked on 25 February after the ships arrived in Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

Harbour. The two ships were ordered to Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australian vernacular diminutive for ...

, Australia, in mid-March to join the Allied naval forces headquartered there, but they were recalled after three days and assigned to Force B of the Eastern Fleet.

After the raid on Colombo by the Japanese aircraft carriers on 5 April, ''Hermes'' and ''Vampire'' were sent to Trincomalee to prepare for Operation Ironclad

The Battle of Madagascar (5 May – 6 November 1942) was a British campaign to capture the Vichy French-controlled island Madagascar during World War II. The seizure of the island by the British was to deny Madagascar's ports to the Imperial ...

, the British invasion of Madagascar, and 814 Squadron was sent ashore. After advance warning of a Japanese air raid on 9 April 1942, they left Trincomalee and sailed south down the Ceylon coast before it arrived. They were spotted off Batticaloa, however, by a Japanese reconnaissance plane from the battleship . The British intercepted the spot report and ordered the ships to return to Trincomalee with the utmost dispatch and attempted to provide fighter cover for them. The Japanese launched 85 Aichi D3A

The Aichi D3A Type 99 Carrier Bomber ( Allied reporting name "Val") is a World War II carrier-borne dive bomber. It was the primary dive bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) and was involved in almost all IJN actions, including the a ...

dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s, escorted by nine Mitsubishi A6M Zero

The Mitsubishi A6M "Zero" is a long-range carrier-based fighter aircraft formerly manufactured by Mitsubishi Aircraft Company, a part of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, and was operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy from 1940 to 1945. The A6M was ...

fighters, at the two ships. At least 32 attacked them and sank them in quick order despite the arrival of six Fairey Fulmar

The Fairey Fulmar is a British carrier-borne reconnaissance aircraft/fighter aircraft which was developed and manufactured by aircraft company Fairey Aviation. It was named after the northern fulmar, a seabird native to the British Isles. Th ...

II fighters of No. 273 Squadron RAF. Another six Fulmars from 803 and 806 Squadrons arrived after ''Hermes'' had already sunk. The rest of the Japanese aircraft attacked other ships further north, sinking the RFA ''Athelstone'' of 5,571 gross register tonnage (GRT), her escort, the corvette

A corvette is a small warship. It is traditionally the smallest class of vessel considered to be a proper (or " rated") warship. The warship class above the corvette is that of the frigate, while the class below was historically that of the sloop ...

, the oil tanker

An oil tanker, also known as a petroleum tanker, is a ship designed for the bulk cargo, bulk transport of petroleum, oil or its products. There are two basic types of oil tankers: crude tankers and product tankers. Crude tankers move large quant ...

and the Norwegian ship of 2,924 GRT.

''Hermes'' sank at coordinates with the loss of 307 men, including Captain Onslow. ''Vampire''s captain and seven crewmen were also killed. Most of the survivors of the attack were picked up by the hospital ship ''Vita''. Japanese losses to all causes were four D3As lost and five more damaged, while two Fulmars were shot down.

Two HMS ''Hermes''

The merchant ship SS ''Mamari III'' was converted to resemble ''Hermes'' as a decoy ship to confuse the Axis and was redesignated as '' Fleet Tender C''. On 4 June 1941, when she was sailing down the east coast of England to

The merchant ship SS ''Mamari III'' was converted to resemble ''Hermes'' as a decoy ship to confuse the Axis and was redesignated as '' Fleet Tender C''. On 4 June 1941, when she was sailing down the east coast of England to Chatham Dockyard

Chatham Dockyard was a Royal Navy Dockyard located on the River Medway in Kent. Established in Chatham in the mid-16th century, the dockyard subsequently expanded into neighbouring Gillingham (at its most extensive, in the early 20th centur ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces the ...

to be converted back into a cargo ship, the decoy ''Hermes'' hit a submerged wreck off Norfolk

Norfolk () is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in East Anglia in England. It borders Lincolnshire to the north-west, Cambridgeshire to the west and south-west, and Suffolk to the south. Its northern and eastern boundaries are the North ...

during a German aerial attack. Before she could be refloated, she was crippled by German E-boat

E-boat was the Western Allies' designation for the fast attack craft (German: ''Schnellboot'', or ''S-Boot'', meaning "fast boat") of the Kriegsmarine during World War II; ''E-boat'' could refer to a patrol craft from an armed motorboat to a la ...

s and abandoned in place.

Notes

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * *External links

*Fleet Air Arm Archive

WW2DB: Hermes

* ttp://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/80016112 IWM Interview with survivor Eric Monaghan

The Story of the SS ''Tungchow'' tod by a Survivor

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hermes (95) 1919 ships Aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy Aircraft carriers sunk by aircraft Maritime incidents in July 1940 Maritime incidents in April 1942 Ships built on the River Tyne World War II aircraft carriers of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Indian Ocean Ships sunk by Japanese aircraft Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Wreck diving sites