HMS Courageous (50) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Courageous'' was the

''Courageous'' could carry up to 48 aircraft; following completion of her trials and embarking stores and personnel, she sailed for

''Courageous'' could carry up to 48 aircraft; following completion of her trials and embarking stores and personnel, she sailed for

''Courageous'' served with the Home Fleet at the start of World War II with 811 and 822 Squadrons aboard, each squadron equipped with a dozen Fairey Swordfish. In the early days of the war, hunter-killer groups were formed around the fleet's aircraft carriers to find and destroy U-boats. On 31 August 1939 she went to her war station at Portland and embarked the two squadrons of Swordfish. ''Courageous'' departed Plymouth on the evening of 3 September 1939 for an anti-submarine patrol in the

''Courageous'' served with the Home Fleet at the start of World War II with 811 and 822 Squadrons aboard, each squadron equipped with a dozen Fairey Swordfish. In the early days of the war, hunter-killer groups were formed around the fleet's aircraft carriers to find and destroy U-boats. On 31 August 1939 she went to her war station at Portland and embarked the two squadrons of Swordfish. ''Courageous'' departed Plymouth on the evening of 3 September 1939 for an anti-submarine patrol in the

Photo gallery of ''Courageous'' and ''Glorious''

Data on as-fitted design and equipment

IWM Interview with survivor Walter Young

IWM Interview with survivor Gordon Smerdon

IWM Interview with survivor Patrick Cannon

{{DEFAULTSORT:Courageous (50) 1916 ships Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Courageous-class aircraft carriers Maritime incidents in September 1939 Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II Ships built on the River Tyne World War I battlecruisers of the United Kingdom World War II aircraft carriers of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean

lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very complex and may ...

of her class of three battlecruisers built for the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Designed to support the Baltic Project

The Baltic Project was a plan promoted by the Admiral Lord Fisher to procure a speedy victory during the First World War over Germany. It involved landing a substantial force, either British or Russian soldiers, on the flat beaches of Pomerania o ...

championed by First Sea Lord

The First Sea Lord and Chief of the Naval Staff (1SL/CNS) is the military head of the Royal Navy and Naval Service of the United Kingdom. The First Sea Lord is usually the highest ranking and most senior admiral to serve in the British Armed Fo ...

John Fisher

John Fisher (c. 19 October 1469 – 22 June 1535) was an English Catholic bishop, cardinal, and theologian. Fisher was also an academic and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge. He was canonized by Pope Pius XI.

Fisher was executed by o ...

, the ship was very lightly armoured and armed with only a few heavy guns. ''Courageous'' was completed in late 1916 and spent the war patrolling the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. She participated in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight

The Second Battle of Heligoland Bight, also the Action in the Helgoland Bight and the , was an inconclusive naval engagement fought between British and German squadrons on 17 November 1917 during the First World War.

Background

British minela ...

in November 1917 and was present when the German High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet (''Hochseeflotte'') was the battle fleet of the German Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. The formation was created in February 1907, when the Home Fleet (''Heimatflotte'') was renamed as the High Seas ...

surrendered a year later.

''Courageous'' was decommissioned after the war, then rebuilt as an aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

during the mid-1920s. She could carry 48 aircraft compared to the 36 carried by her half-sister

A sibling is a relative that shares at least one parent with the subject. A male sibling is a brother and a female sibling is a sister. A person with no siblings is an only child.

While some circumstances can cause siblings to be raised separat ...

on approximately the same displacement. After recommissioning she spent most of her career operating off Great Britain and Ireland. She briefly became a training ship

A training ship is a ship used to train students as sailors. The term is mostly used to describe ships employed by navies to train future officers. Essentially there are two types: those used for training at sea and old hulks used to house classr ...

, but reverted to her normal role a few months before the start of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

in September 1939. ''Courageous'' was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

later that month, going down with the loss of more than 500 of her crew.

Origin and construction

During the First World War,Admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

Fisher was prevented from ordering an improved version of the preceding s by a wartime restriction that banned construction of ships larger than light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s in 1915. To obtain ships suitable for the doctrinal roles of battlecruisers, such as scouting for fleets and hunting enemy raiders, he settled on ships with the minimal armour of a light cruiser and the armament of a battlecruiser. He justified their existence by claiming he needed fast, shallow-draught ships for his Baltic Project

The Baltic Project was a plan promoted by the Admiral Lord Fisher to procure a speedy victory during the First World War over Germany. It involved landing a substantial force, either British or Russian soldiers, on the flat beaches of Pomerania o ...

, a plan to invade Germany via its Baltic coast.Burt 1986, p. 303

''Courageous'' had an overall length

The overall length (OAL) of an ammunition cartridge is a measurement from the base of the brass shell casing to the tip of the bullet, seated into the brass casing. Cartridge overall length, or "COL", is important to safe functioning of reloads i ...

of , a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized grou ...

of , and a draught of at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into wei ...

. She displaced at load and at deep load.Roberts, pp. 64–65 ''Courageous'' and her sisters were the first large warships in the Royal Navy to have geared steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turbin ...

s. To save design time, the installation used in the light cruiser , the first cruiser in the navy with geared turbines, was simply replicated for four turbine sets. The Parsons

Parsons may refer to:

Places

In the United States:

* Parsons, Kansas, a city

* Parsons, Missouri, an unincorporated community

* Parsons, Tennessee, a city

* Parsons, West Virginia, a town

* Camp Parsons, a Boy Scout camp in the state of Washingt ...

turbines were powered by eighteen Yarrow

''Achillea millefolium'', commonly known as yarrow () or common yarrow, is a flowering plant in the family Asteraceae. Other common names include old man's pepper, devil's nettle, sanguinary, milfoil, soldier's woundwort, and thousand seal.

The ...

small-tube boilers. They were designed to produce a total of at a working pressure of . The ship reached an estimated during sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s.

The ship's normal design load was of fuel oil

Fuel oil is any of various fractions obtained from the distillation of petroleum (crude oil). Such oils include distillates (the lighter fractions) and residues (the heavier fractions). Fuel oils include heavy fuel oil, marine fuel oil (MFO), bun ...

, but she could carry a maximum of . At full capacity, she could steam for an estimated at a speed of .Burt 1986, p. 306

''Courageous'' carried four BL 15-inch Mk I guns in two hydraulically powered twin gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, designated 'A' and 'Y' from front to rear. Her secondary armament consisted of eighteen BL 4-inch Mk IX guns mounted in six manually powered mounts. The mount placed three breeches

Breeches ( ) are an article of clothing covering the body from the waist down, with separate coverings for each human leg, leg, usually stopping just below the knee, though in some cases reaching to the ankles. Formerly a standard item of Weste ...

too close together, causing the 23 loaders to get in one another's way, and preventing the intended high rate of fire. A pair of QF 3-inch 20 cwt

The QF 3 inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft gun became the standard anti-aircraft gun used in the home defence of the United Kingdom against German airships and bombers and on the Western Front in World War I. It was also common on British warships i ...

"cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight

The hundredweight (abbreviation: cwt), formerly also known as the centum weight or quintal, is a British imperial and US customary unit of weight or mass. Its value differs between the US and British imperial systems. The two values are distingu ...

, 30 cwt referring to the weight of the gun. anti-aircraft

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

guns were fitted abreast the mainmast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation lig ...

on ''Courageous''. She mounted two submerged tubes

Tube or tubes may refer to:

* ''Tube'' (2003 film), a 2003 Korean film

* ''The Tube'' (TV series), a music related TV series by Channel 4 in the United Kingdom

* "Tubes" (Peter Dale), performer on the Soccer AM television show

* Tube (band), a ...

for 21-inch torpedoes and carried 10 torpedoes for them.

First World War

''Courageous'' waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one o ...

on 26 March 1915, launched on 5 February 1916 and completed on 4 November. During her sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s later that month, she sustained structural damage while running at full speed in a rough head sea

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple animals may ...

; the exact cause is uncertain.Roberts, p. 54 The forecastle deck was deeply buckled in three places between the breakwater

Breakwater may refer to:

* Breakwater (structure), a structure for protecting a beach or harbour

Places

* Breakwater, Victoria, a suburb of Geelong, Victoria, Australia

* Breakwater Island

Breakwater Island () is a small island in the Palme ...

and the forward turret. The side plating was visibly buckled between the forecastle and upper decks. Water had entered the submerged torpedo room and rivets had sheared in the angle irons securing the deck armour in place. The ship was stiffened with of steel in response. As of 23 November 1916, she cost £2,038,225 to build.

Upon commissioning, ''Courageous'' was assigned to the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron of the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the F ...

. She became flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the fi ...

of the 1st Cruiser Squadron near the end of 1916 when that unit was re-formed after most of its ships had been sunk at the Battle of Jutland in May.Parkes, p. 621 The ship was temporarily fitted as a minelayer

A minelayer is any warship, submarine or military aircraft deploying explosive mines. Since World War I the term "minelayer" refers specifically to a naval ship used for deploying naval mines. "Mine planting" was the term for installing controll ...

in April 1917 by the addition of mine rails on her quarterdeck that could hold over 200 mines, but never laid any mines. In mid-1917, she received half a dozen torpedo mounts, each with two tubes: one mount on each side of the mainmast

The mast of a sailing vessel is a tall spar, or arrangement of spars, erected more or less vertically on the centre-line of a ship or boat. Its purposes include carrying sails, spars, and derricks, and giving necessary height to a navigation lig ...

on the upper deck and two mounts on each side of the rear turret on the quarterdeck.Burt 1986, p. 314 On 30 July 1917, Rear-Admiral Trevylyan Napier

Vice Admiral Sir Trevylyan Dacres Willes Napier, (19 April 1867 – 30 July 1920) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Commander-in-Chief, America and West Indies Station.

Naval career

Napier was the son of Ella Louisa (Wilson) an ...

assumed command of the 1st Cruiser Squadron and was appointed Acting Vice-Admiral Commanding the Light Cruiser Force until he was relieved on 26 October 1918.

On 16 October 1917, the Admiralty received word of German ship movements, possibly indicating a raid. Admiral Beatty, the commander of the Grand Fleet, ordered most of his light cruisers and destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, manoeuvrable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy or battle group and defend them against powerful short range attackers. They were originally developed in ...

s to sea in an effort to locate the enemy ships. ''Courageous'' and ''Glorious'' were not initially included amongst them, but were sent to reinforce the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron patrolling the central part of the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

later that day. Two German light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s managed to slip through the gaps between the British patrols and destroy a convoy bound for Norway during the morning of 17 October, but no word was received of the engagement until that afternoon. The 1st Cruiser Squadron was ordered to intercept, but was unsuccessful as the German cruisers were faster than expected.

Second Battle of Heligoland Bight

Throughout 1917 the Admiralty was becoming more concerned about German efforts to sweep paths through the British-laid minefields intended to restrict the actions of the High Seas Fleet and Germansubmarine

A submarine (or sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability. The term is also sometimes used historically or colloquially to refer to remotely op ...

s. A preliminary raid on German minesweeping forces on 31 October by light forces destroyed ten small ships. Based on intelligence reports, the Admiralty allocated the 1st Cruiser Squadron on 17 November 1917, with cover provided by the reinforced 1st Battlecruiser Squadron and distant cover by the battleship

A battleship is a large armored warship with a main battery consisting of large caliber guns. It dominated naval warfare in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The term ''battleship'' came into use in the late 1880s to describe a type of ...

s of the 1st Battle Squadron, to destroy the minesweeper

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

s and their light cruiser escorts.

The German ships—four light cruisers of II Scouting Force, eight destroyers, three divisions of minesweepers, eight ''Sperrbrecher

A ''Sperrbrecher'' (German; informally translated as "pathfinder" but literally meaning "mine barrage breaker"), was a German auxiliary ship of the First World War and the Second World War that served as a type of minesweeper, steaming ahead of ot ...

''s (cork-filled trawlers) and two other trawlers to mark the swept route—were spotted at 7:30 am.The times used in this article are in UTC, which is one hour behind CET

CET or cet may refer to:

Places

* Cet, Albania

* Cet, standard astronomical abbreviation for the constellation Cetus

* Colchester Town railway station (National Rail code CET), in Colchester, England

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Comcast En ...

, which is often used in German works. ''Courageous'' and the light cruiser opened fire with their forward guns seven minutes later. The Germans responded by laying an effective smoke screen

A smoke screen is smoke released to mask the movement or location of military units such as infantry, tanks, aircraft, or ships.

Smoke screens are commonly deployed either by a canister (such as a grenade) or generated by a vehicle (such as ...

. The British continued in pursuit, but lost track of most of the smaller ships in the smoke and concentrated fire on the light cruisers. ''Courageous'' fired 92 fifteen-inch shells and 180 four-inch shells during the battle, and the only damage she received was from her own muzzle blast

A muzzle blast is an explosive shockwave created at the muzzle of a firearm during shooting. Before a projectile leaves the gun barrel, it obturates the bore and "plugs up" the pressurized gaseous products of the propellant combustion behind i ...

. One fifteen-inch shell hit a gun shield of the light cruiser but did not affect her speed. At 9:30 the 1st Cruiser Squadron broke off their pursuit so that they would not enter a minefield marked on their maps; the ships turned south, playing no further role in the battle.

After the battle, the mine fittings on ''Courageous'' were removed, and she spent the rest of the war intermittently patrolling the North Sea. In 1918, short take-off platforms were fitted for a Sopwith Camel

The Sopwith Camel is a British First World War single-seat biplane fighter aircraft that was introduced on the Western Front in 1917. It was developed by the Sopwith Aviation Company as a successor to the Sopwith Pup and became one of the b ...

and a Sopwith 1½ Strutter on both turrets. The ship was present at the surrender of the German High Seas fleet on 21 November 1918. ''Courageous'' was placed in reserve at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style suburb ...

on 1 February 1919 and she again became Napier's flagship as he was appointed Vice-Admiral Commanding the Rosyth Reserve until 1 May, The ship was assigned to the Gunnery School at Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is administered by Portsmouth City Council.

Portsmouth is the most dens ...

the following year as a turret drill ship. She became flagship of the Rear-Admiral Commanding the Reserve at Portsmouth in March 1920. Captain Sidney Meyrick

Admiral Sir Sidney Julius Meyrick KCB (28 March 1879 – 18 December 1973) was a Royal Navy officer who went on to be Commander-in-Chief, America and West Indies Station.

Naval career

Meyrick joined the Royal Navy in 1893. He served in the ...

became her Flag Captain

In the Royal Navy, a flag captain was the captain of an admiral's flagship. During the 18th and 19th centuries, this ship might also have a "captain of the fleet", who would be ranked between the admiral and the "flag captain" as the ship's "First ...

in 1920. He was relieved by Capt John Casement in August 1921.

Between the wars

Conversion

TheWashington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was a treaty signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting naval construction. It was negotiated at the Washington Nav ...

of 1922 severely limited capital ship tonnage, and the Royal Navy was forced to scrap many of its older battleships and battlecruisers. The treaty allowed the conversion of existing ships totalling up to into aircraft carriers, and the ''Courageous'' class's combination of a large hull and high speed made these ships ideal candidates. The conversion of ''Courageous'' began on 29 June 1924 at Devonport. Her fifteen-inch turrets were placed into storage and reused during the Second World War for , the Royal Navy's last battleship. The conversion into an aircraft carrier cost £2,025,800.

The ship's new design improved on her half-sister HMS ''Furious'', which lacked an island

An island (or isle) is an isolated piece of habitat that is surrounded by a dramatically different habitat, such as water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island ...

and a conventional funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construct ...

. All superstructure, guns, torpedo tubes, and fittings down to the main deck were removed. A two-storey hangar was built on top of the remaining hull; each level was high and long. The upper hangar level opened onto a short flying-off deck, below and forward of the main flight deck. The flying-off deck improved launch and recovery cycle Aircraft carrier air operations include a launch and recovery cycle of embarked aircraft. Launch and recovery cycles are scheduled to support efficient use of naval aircraft for searching, defensive patrols, and offensive airstrikes. The relative ...

flexibility until new fighters requiring longer takeoff rolls made the lower deck obsolete in the 1930s. Two lifts were installed fore and aft in the flight deck. An island with the bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

, flying control station and funnel was added on the starboard side, since islands had been found not to contribute significantly to turbulence. By 1939 the ship could carry of petrol for her aircraft.

''Courageous'' received a dual-purpose armament of sixteen QF 4.7-inch Mk VIII guns in single HA Mark XII mounts. Each side of the lower flight deck had a mount, and two were on the quarterdeck. The remaining twelve mounts were distributed along the sides of the ship. During refits in the mid-1930s, ''Courageous'' received three quadruple Mk VII mounts for 2-pounder "pom-pom" anti-aircraft gun

Anti-aircraft warfare, counter-air or air defence forces is the battlespace response to aerial warfare, defined by NATO as "all measures designed to nullify or reduce the effectiveness of hostile air action".AAP-6 It includes surface based, ...

s, two of which were transferred from the battleship . Each side of the flying-off deck had a mount, forward of the 4.7-inch guns, and one was behind the island on the flight deck. She also received four water-cooled .50-calibre Mk III anti-aircraft machine guns in a single quadruple mounting. This was placed in a sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercraft

On watercraft, a spon ...

on the port side aft.

The reconstruction was completed on 21 February 1928, and the ship spent the next several months on trials and training before she was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet to be based at Malta, in which she served from May 1928 to June 1930.Burt 1993, pp. 281, 285 In August 1929, the 1929 Palestine riots

The 1929 Palestine riots, Buraq Uprising ( ar, ثورة البراق, ) or the Events of 1929 ( he, מאורעות תרפ"ט, , ''lit.'' Events of 5689 Anno Mundi), was a series of demonstrations and riots in late August 1929 in which a longst ...

broke out, and ''Courageous'' was ordered to respond. When she arrived off Palestine, her air wing was disembarked to carry out operations to help to suppress the disorder.Sturtivant ''Air Enthusiast''September–December 1988, p. 13. The ship was relieved from the Mediterranean by ''Glorious'' and refitted from June to August 1930. She was assigned to the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

and Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the First ...

s from 12 August 1930 to December 1938, aside from a temporary attachment to the Mediterranean Fleet in 1936. In the early 1930s, traverse arresting gear was installed and she received two hydraulic aircraft catapult

An aircraft catapult is a device used to allow aircraft to take off from a very limited amount of space, such as the deck of a vessel, but can also be installed on land-based runways in rare cases. It is now most commonly used on aircraft carrier ...

s on the upper flight deck before March 1934. ''Courageous'' was refitted again between October 1935 and June 1936 with her pom-pom mounts. She was present at the Coronation Fleet Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

on 20 May 1937 for King George VI

George VI (Albert Frederick Arthur George; 14 December 1895 – 6 February 1952) was King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Commonwealth from 11 December 1936 until Death and state funeral of George VI, his death in 1952. ...

. The ship became a training carrier in December 1938 when joined the Home Fleet. She was relieved of that duty by her half-sister ''Furious'' in May 1939. ''Courageous'' participated in the Portland

Portland most commonly refers to:

* Portland, Oregon, the largest city in the state of Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States

* Portland, Maine, the largest city in the state of Maine, in the New England region of the northeas ...

Fleet Review on 9 August 1939.

Air group

''Courageous'' could carry up to 48 aircraft; following completion of her trials and embarking stores and personnel, she sailed for

''Courageous'' could carry up to 48 aircraft; following completion of her trials and embarking stores and personnel, she sailed for Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshire ...

on 14 May 1928. The following day, a Blackburn Dart

The Blackburn Dart was a carrier-based torpedo bomber biplane designed and manufactured by the British aviation company Blackburn Aircraft. It was the standard single-seat torpedo bomber operated by the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) between 1923 and 19 ...

of 463 Flight made the ship's first deck landing. The Dart was followed by the Fairey Flycatcher

The Fairey Flycatcher was a British single-seat biplane carrier-borne fighter aircraft made by Fairey Aviation Company which served from 1923 to 1934. It was produced with a conventional undercarriage for carrier use, although this could be exc ...

s of 404 and 407 Flights, the Fairey IIIF

The Fairey Aviation Company Fairey III was a family of British reconnaissance biplanes that enjoyed a very long production and service history in both landplane and seaplane variants. First flying on 14 September 1917, examples were still in us ...

s of 445 and 446 Flights and the Darts of 463 and 464 Flight. The ship sailed for Malta on 2 June to join the Mediterranean Fleet.

From 1933 to the end of 1938 ''Courageous'' carried No. 800 Squadron, which flew a mixture of nine Hawker Nimrod

The Hawker Nimrod is a British carrier-based single-engine, single-seat biplane fighter aircraft built in the early 1930s by Hawker Aircraft.

Design and development

In 1926 the Air Ministry specification N.21/26 was intended to produce a suc ...

and three Hawker Osprey

The Hawker Hart is a British two-seater biplane light bomber aircraft that saw service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was designed during the 1920s by Sydney Camm and manufactured by Hawker Aircraft. The Hart was a prominent British aircra ...

fighters. 810

__NOTOC__

Year 810 ( DCCCX) was a common year starting on Tuesday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Byzantine Empire

* Spring – The Venetian dukes change sides again, submitting to Ki ...

, 820

__NOTOC__

Year 820 ( DCCCXX) was a leap year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place Abbasid Caliphate

*Abbasid caliph Al-Ma'mun appointed Isa ibn Yazid al-Juludi as Abbasid gove ...

and 821 Squadrons were embarked for reconnaissance and anti-ship attack missions during the same period. They flew the Blackburn Baffin

The Blackburn B-5 Baffin biplane torpedo bomber designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Blackburn Aircraft. It was a development of the Blackburn Ripon, Ripon, the chief change being that a 545 hp (406 kW) Bristol Pe ...

, the Blackburn Shark, the Blackburn Ripon

The Blackburn T.5 Ripon was a carrier-based torpedo bomber and reconnaissance biplane designed and produced by the British aircraft manufacturer Blackburn Aircraft. It was the basis for both the license-produced Mitsubishi B2M and the improved ...

and the Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also us ...

torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carrying the weight ...

s as well as Fairey Seal

The Fairey Seal was a British carrier-borne spotter-reconnaissance aircraft, operated in the 1930s. The Seal was derived – like the Gordon – from the IIIF. To enable the Fairey Seal to be launched by catapult from warships, it could be f ...

reconnaissance aircraft. As a deck landing training carrier, in early 1939 ''Courageous'' embarked the Blackburn Skua

The Blackburn B-24 Skua was a carrier-based low-wing, two-seater, single- radial engine aircraft by the British aviation company Blackburn Aircraft. It was the first Royal Navy carrier-borne all-metal cantilever monoplane aircraft, as well as t ...

and Gloster Sea Gladiator

The Gloster Gladiator is a British biplane fighter. It was used by the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) (as the Sea Gladiator variant) and was exported to a number of other air forces during the late 1930s.

Developed private ...

fighters of 801 Squadron and the Swordfish torpedo bombers of 811 Squadron, although both of these squadrons were disembarked when the ship was relieved of her training duties in May.

Second World War and sinking

''Courageous'' served with the Home Fleet at the start of World War II with 811 and 822 Squadrons aboard, each squadron equipped with a dozen Fairey Swordfish. In the early days of the war, hunter-killer groups were formed around the fleet's aircraft carriers to find and destroy U-boats. On 31 August 1939 she went to her war station at Portland and embarked the two squadrons of Swordfish. ''Courageous'' departed Plymouth on the evening of 3 September 1939 for an anti-submarine patrol in the

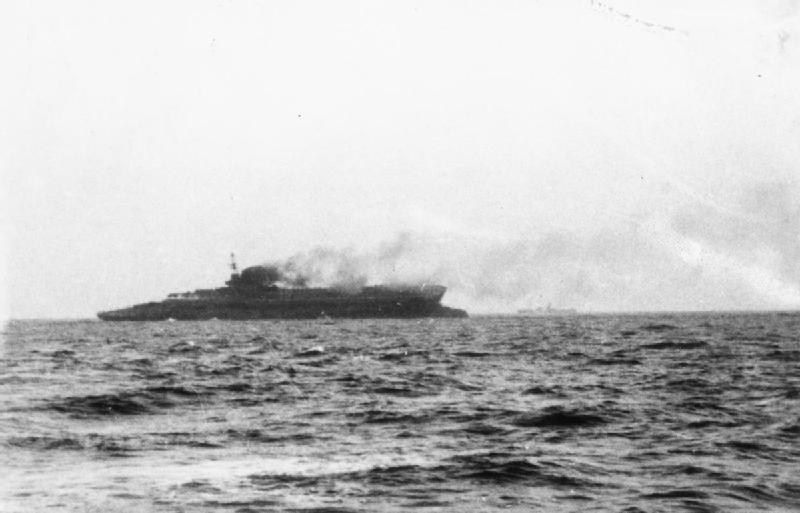

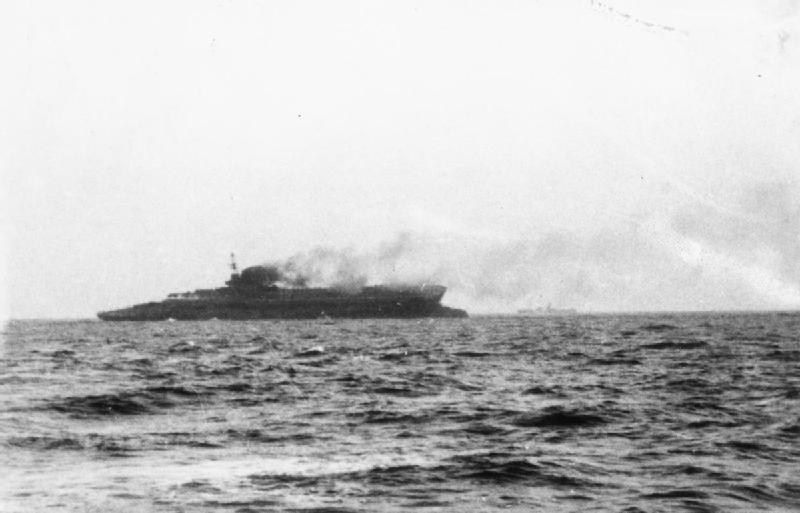

''Courageous'' served with the Home Fleet at the start of World War II with 811 and 822 Squadrons aboard, each squadron equipped with a dozen Fairey Swordfish. In the early days of the war, hunter-killer groups were formed around the fleet's aircraft carriers to find and destroy U-boats. On 31 August 1939 she went to her war station at Portland and embarked the two squadrons of Swordfish. ''Courageous'' departed Plymouth on the evening of 3 September 1939 for an anti-submarine patrol in the Western Approaches

The Western Approaches is an approximately rectangular area of the Atlantic Ocean lying immediately to the west of Ireland and parts of Great Britain. Its north and south boundaries are defined by the corresponding extremities of Britain. The c ...

, escorted by four destroyers. On the evening of 17 September 1939, she was on one such patrol off the coast of Ireland. Two of her four escorting destroyers had been sent to help a merchant ship

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which are u ...

under attack and all her aircraft had returned from patrols. During this time, ''Courageous'' was stalked for over two hours by , commanded by Captain-Lieutenant

Captain lieutenant or captain-lieutenant is a military rank, used in a number of navies worldwide and formerly in the British Army.

Northern Europe Denmark, Norway and Finland

The same rank is used in the navies of Denmark (), Norway () and Finl ...

Otto Schuhart

Otto Schuhart (4 September 1909 – 10 March 1990) was a German submarine commander during World War II, who commanded the U-boat and was credited with the sinking of the aircraft carrier on 17 September 1939, the first British warship t ...

. The carrier then turned into the wind to launch her aircraft. This put the ship right across the bow of the submarine, which fired three torpedoes. Two of the torpedoes struck the ship on her port side

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Ham ...

before any aircraft took off, knocking out all electrical power, and she capsized

Capsizing or keeling over occurs when a boat or ship is rolled on its side or further by wave action, instability or wind force beyond the angle of positive static stability or it is upside down in the water. The act of recovering a vessel fro ...

and sank in 20 minutes with the loss of 519 of her crew, including her captain. The survivors were rescued by the Dutch ocean liner

An ocean liner is a passenger ship primarily used as a form of transportation across seas or oceans. Ocean liners may also carry cargo or mail, and may sometimes be used for other purposes (such as for pleasure cruises or as hospital ships).

Ca ...

''Veendam'' and the British freighter ''Collingworth''. The two escorting destroyers counterattacked ''U-29'' for four hours, but the submarine escaped.

An earlier unsuccessful attack on ''Ark Royal'' by on 14 September, followed by the sinking of ''Courageous'' three days later, prompted the Royal Navy to withdraw its carriers from anti-submarine patrols. ''Courageous'' was the first British warship to be sunk by German forces. (The submarine had been sunk a week earlier by friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while en ...

from the British submarine .)Rohwer, pp. 1–3 The commander of the German submarine force, Commodore Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz (sometimes spelled Doenitz; ; 16 September 1891 24 December 1980) was a German admiral who briefly succeeded Adolf Hitler as head of state in May 1945, holding the position until the dissolution of the Flensburg Government follo ...

, regarded the sinking of ''Courageous'' as "a wonderful success" and it led to widespread jubilation in the ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

'' (German navy). Grand Admiral Erich Raeder

Erich Johann Albert Raeder (24 April 1876 – 6 November 1960) was a German admiral who played a major role in the naval history of World War II. Raeder attained the highest possible naval rank, that of grand admiral, in 1939, becoming the f ...

, commander of the ''Kriegsmarine'', directed that Schuhart be awarded the Iron Cross First Class

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

and that all other members of the crew receive the Iron Cross Second Class.Blair, p. 91

Notes

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Photo gallery of ''Courageous'' and ''Glorious''

Data on as-fitted design and equipment

IWM Interview with survivor Walter Young

IWM Interview with survivor Gordon Smerdon

IWM Interview with survivor Patrick Cannon

{{DEFAULTSORT:Courageous (50) 1916 ships Ships built by Armstrong Whitworth Courageous-class aircraft carriers Maritime incidents in September 1939 Ships sunk by German submarines in World War II Ships built on the River Tyne World War I battlecruisers of the United Kingdom World War II aircraft carriers of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Atlantic Ocean