Hydroxyarenes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Phenol (also called carbolic acid) is an

C6H5OH <=> C6H5O- + H+

Phenol is more acidic than aliphatic alcohols. The differing pKa is attributed to

Phenol is more acidic than aliphatic alcohols. The differing pKa is attributed to

Phenol exhibits

Phenol exhibits

Phenol is highly reactive toward

Phenol is highly reactive toward C6H5OH + NaOH -> C6H5ONa + H2O

When a mixture of phenol and C6H5COCl + HOC6H5 -> C6H5CO2C6H5 + HCl

Phenol is reduced to C6H5OH + Zn -> C6H6 + ZnO

When phenol is treated with C6H5OH + CH2N2 -> C6H5OCH3 + N2

When phenol reacts with iron(III) chloride solution, an intense violet-purple solution is formed.

Accounting for 95% of production (2003) is the

Accounting for 95% of production (2003) is the

C6H6 + O -> C6H5OH

C6H5CH3 + 2 O2 -> C6H5OH + CO2 + H2O

The reaction is proposed to proceed via formation of benzyoylsalicylate.

C6H5SO3H + 2 NaOH -> C6H5OH + Na2SO3 + H2O

C6H5Cl + NaOH -> C6H5OH + NaCl

:C6H5Cl + H2O -> C6H5OH + HCl

These methods suffer from the cost of the chlorobenzene and the need to dispose of the chloride by product.

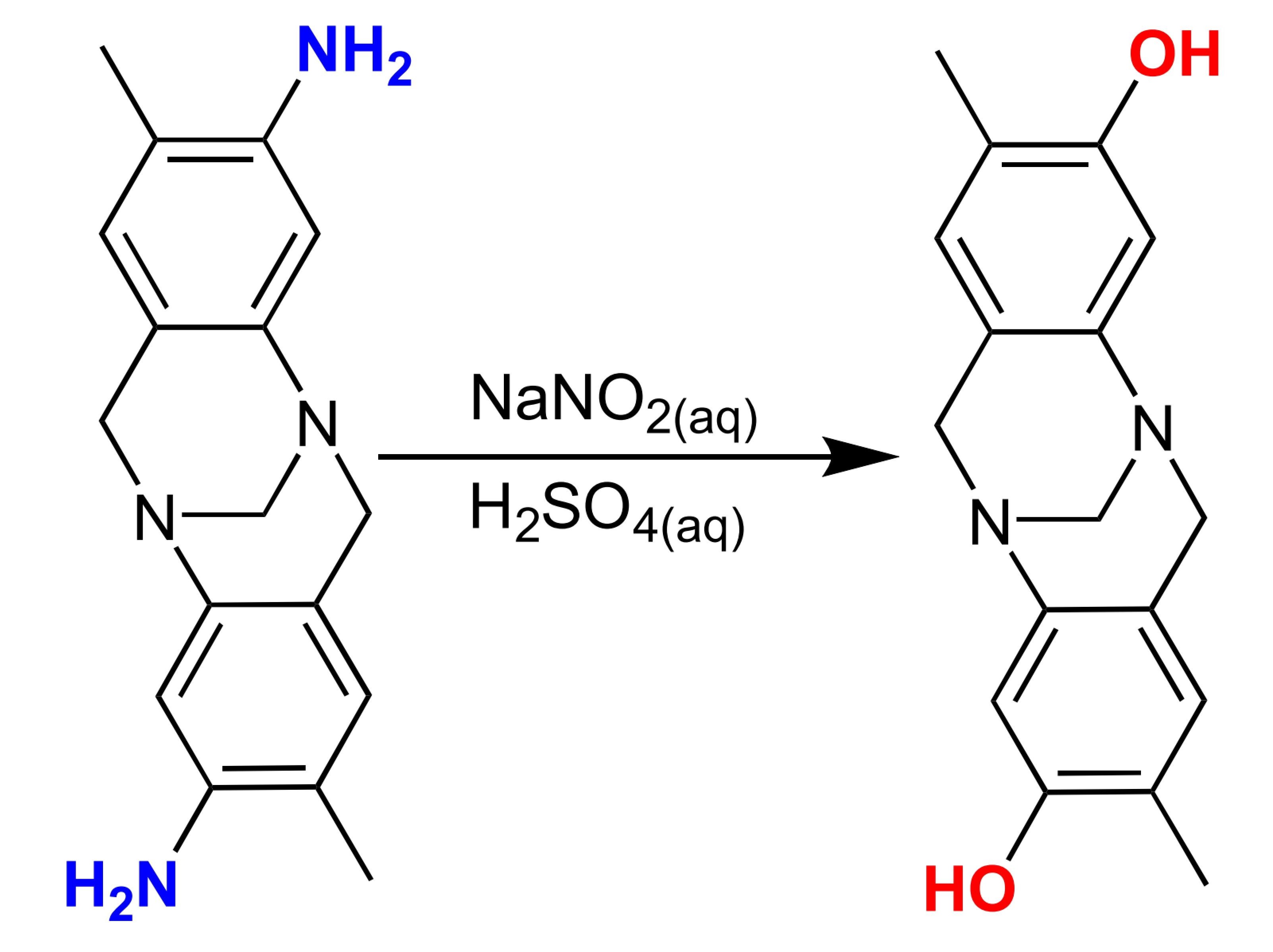

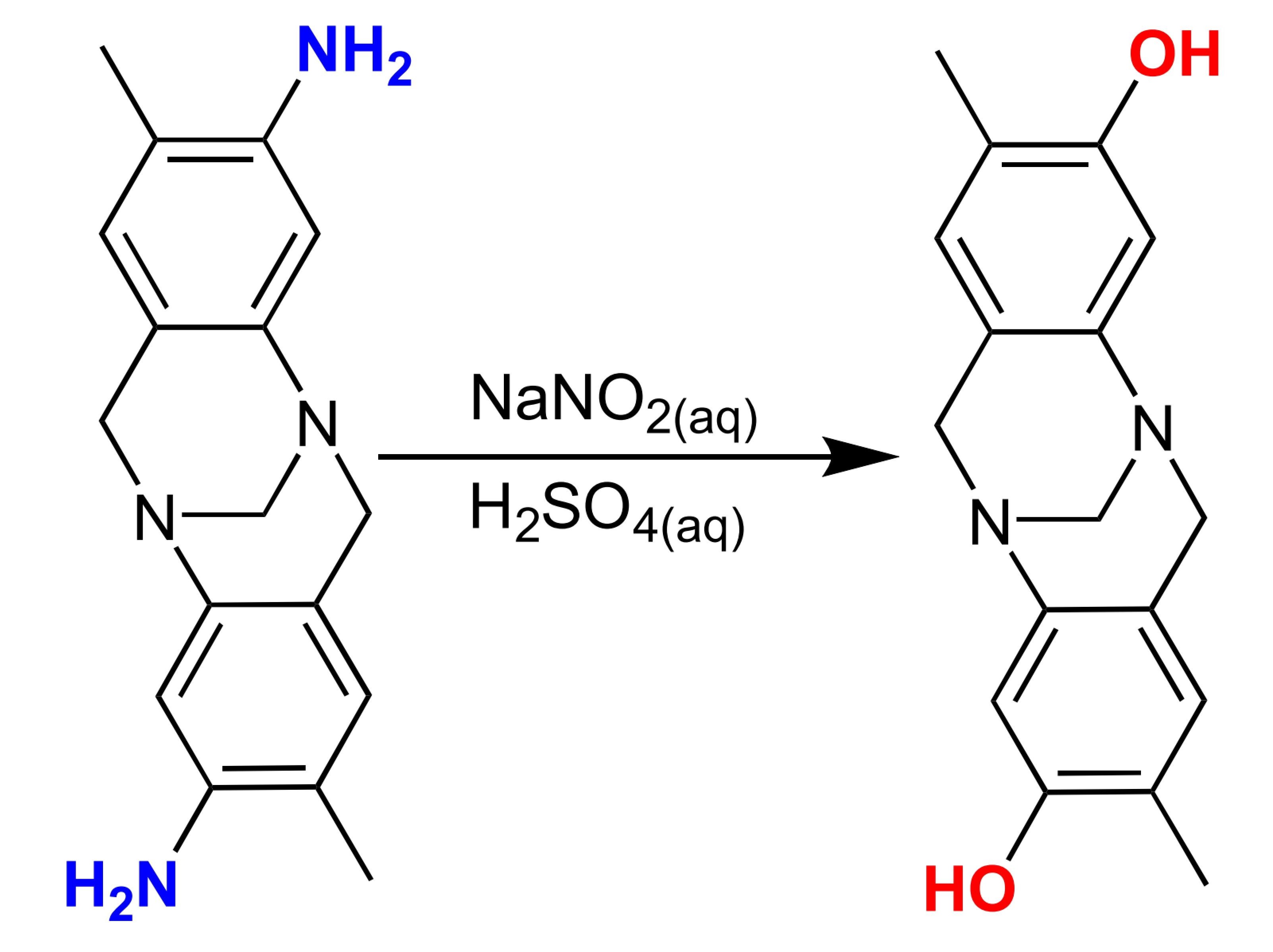

C6H5NH2 + HCl/NaNO2 -> C6H5OH + N2 + H2O + NaCl

:

by Peter Tyson. NOVA It was originally used by the Nazis in 1939 as part of the

, Chapter 14, Killing with Syringes: Phenol Injections. By Dr. Robert Jay Lifton The Germans learned that extermination of smaller groups was more economical by injection of each victim with phenol. Phenol injections were given to thousands of people.

International Chemical Safety Card 0070National Pollutant Inventory: Phenol Fact SheetCDC - Phenol - NIOSH Workplace Safety and Health Topic

{{Authority control Antiseptics Commodity chemicals Hazardous air pollutants Oxoacids Phenyl compounds 1834 in science

aromatic

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic ( ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to satur ...

organic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The ...

with the molecular formula

In science, a formula is a concise way of expressing information symbolically, as in a mathematical formula or a ''chemical formula''. The informal use of the term ''formula'' in science refers to the general construct of a relationship betwee ...

. It is a white crystal

A crystal or crystalline solid is a solid material whose constituents (such as atoms, molecules, or ions) are arranged in a highly ordered microscopic structure, forming a crystal lattice that extends in all directions. In addition, macros ...

line solid

Solid is one of the State of matter#Four fundamental states, four fundamental states of matter (the others being liquid, gas, and Plasma (physics), plasma). The molecules in a solid are closely packed together and contain the least amount o ...

that is volatile. The molecule consists of a phenyl group

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula C6 H5, and is often represented by the symbol Ph. Phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ring, minus a hydrogen ...

() bonded to a hydroxy group

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy ...

(). Mildly acidic

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

, it requires careful handling because it can cause chemical burn

A chemical burn occurs when living tissue is exposed to a corrosive substance (such as a strong acid, base or oxidizer) or a cytotoxic agent (such as mustard gas, lewisite or arsine). Chemical burns follow standard burn classification and may ca ...

s.

Phenol was first extracted from coal tar

Coal tar is a thick dark liquid which is a by-product of the production of coke and coal gas from coal. It is a type of creosote. It has both medical and industrial uses. Medicinally it is a topical medication applied to skin to treat psoriasi ...

, but today is produced on a large scale (about 7 billion kg/year) from petroleum

Petroleum, also known as crude oil, or simply oil, is a naturally occurring yellowish-black liquid mixture of mainly hydrocarbons, and is found in geological formations. The name ''petroleum'' covers both naturally occurring unprocessed crud ...

-derived feedstocks. It is an important industrial commodity

In economics, a commodity is an economic good, usually a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.

The price of a comm ...

as a precursor

Precursor or Precursors may refer to:

*Precursor (religion), a forerunner, predecessor

** The Precursor, John the Baptist

Science and technology

* Precursor (bird), a hypothesized genus of fossil birds that was composed of fossilized parts of unr ...

to many materials and useful compounds. It is primarily used to synthesize plastics

Plastics are a wide range of synthetic polymers, synthetic or semi-synthetic materials that use polymers as a main ingredient. Their Plasticity (physics), plasticity makes it possible for plastics to be Injection moulding, moulded, Extrusion, e ...

and related materials. Phenol and its chemical derivatives

The derivative of a function is the rate of change of the function's output relative to its input value.

Derivative may also refer to:

In mathematics and economics

* Brzozowski derivative in the theory of formal languages

* Formal derivative, an ...

are essential for production of polycarbonate

Polycarbonates (PC) are a group of thermoplastic polymers containing carbonate groups in their chemical structures. Polycarbonates used in engineering are strong, tough materials, and some grades are optically transparent. They are easily work ...

s, epoxies

The Epoxies were an American New wave music, new wave band from Portland, Oregon, formed in 2000. Heavily influenced by new wave, the band jokingly described themselves as robot garage rock. Members included FM Static on synthesizers, guitarist ...

, Bakelite

Polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride, better known as Bakelite ( ), is a thermosetting phenol formaldehyde resin, formed from a condensation reaction of phenol with formaldehyde. The first plastic made from synthetic components, it was developed ...

, nylon

Nylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers composed of polyamides ( repeating units linked by amide links).The polyamides may be aliphatic or semi-aromatic.

Nylon is a silk-like thermoplastic, generally made from petro ...

, detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are more ...

s, herbicide

Herbicides (, ), also commonly known as weedkillers, are substances used to control undesired plants, also known as weeds.EPA. February 201Pesticides Industry. Sales and Usage 2006 and 2007: Market Estimates. Summary in press releasMain page fo ...

s such as phenoxy herbicide

Phenoxy herbicides (or "phenoxies") are two families of chemicals that have been developed as commercially important herbicides, widely used in agriculture. They share the part structure of phenoxyacetic acid. Auxins

The first group to be discover ...

s, and numerous pharmaceutical drug

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and re ...

s.

Properties

Phenol is an organic compound appreciablysoluble

In chemistry, solubility is the ability of a substance, the solute, to form a solution with another substance, the solvent. Insolubility is the opposite property, the inability of the solute to form such a solution.

The extent of the solubil ...

in water, with about 84.2 g dissolving in 1000 mL (0.895 M). Homogeneous mixtures of phenol and water at phenol to water mass ratios of ~2.6 and higher are possible. The sodium salt of phenol, sodium phenoxide

Sodium phenoxide (sodium phenolate) is an organic compound with the formula NaOC6H5. It is a white crystalline solid. Its anion, phenoxide, also known as phenolate, is the conjugate base of phenol. It is used as a precursor to many other organic ...

, is far more water-soluble.

Acidity

Phenol is a weak acid. In aqueous solution in the pH range ca. 8 - 12 it is in equilibrium with the phenolateanion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

(also called phenoxide):

:resonance stabilization

In chemistry, resonance, also called mesomerism, is a way of describing bonding in certain molecules or polyatomic ions by the combination of several contributing structures (or ''forms'', also variously known as ''resonance structures'' or '' ...

of the phenoxide anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

. In this way, the negative charge on oxygen is delocalized on to the ortho and para carbon atoms through the pi system. An alternative explanation involves the sigma framework, postulating that the dominant effect is the induction

Induction, Inducible or Inductive may refer to:

Biology and medicine

* Labor induction (birth/pregnancy)

* Induction chemotherapy, in medicine

* Induced stem cells, stem cells derived from somatic, reproductive, pluripotent or other cell t ...

from the more electronegative sp2 hybridised carbons; the comparatively more powerful inductive withdrawal of electron density that is provided by the sp2 system compared to an sp3 system allows for great stabilization of the oxyanion. In support of the second explanation, the p''K''a of the enol

In organic chemistry, alkenols (shortened to enols) are a type of reactive structure or intermediate in organic chemistry that is represented as an alkene ( olefin) with a hydroxyl group attached to one end of the alkene double bond (). The te ...

of acetone

Acetone (2-propanone or dimethyl ketone), is an organic compound with the formula . It is the simplest and smallest ketone (). It is a colorless, highly volatile and flammable liquid with a characteristic pungent odour.

Acetone is miscib ...

in water is 10.9, making it only slightly less acidic than phenol (p''K''a 10.0). Thus, the greater number of resonance structures available to phenoxide compared to acetone enolate seems to contribute very little to its stabilization. However, the situation changes when solvation effects are excluded. A recent ''in silico'' comparison of the gas phase acidities of the vinylogues of phenol and cyclohexanol in conformations that allow for or exclude resonance stabilization leads to the inference that about of the increased acidity of phenol is attributable to inductive effects, with resonance accounting for the remaining difference.

Hydrogen bonding

Incarbon tetrachloride

Carbon tetrachloride, also known by many other names (such as tetrachloromethane, also IUPAC nomenclature of inorganic chemistry, recognised by the IUPAC, carbon tet in the cleaning industry, Halon-104 in firefighting, and Refrigerant-10 in HVAC ...

and alkane solvents phenol hydrogen bonds

In chemistry, a hydrogen bond (or H-bond) is a primarily electrostatic force of attraction between a hydrogen (H) atom which is covalently bound to a more electronegative "donor" atom or group (Dn), and another electronegative atom bearing a ...

with a wide range of Lewis bases such as pyridine

Pyridine is a basic heterocyclic organic compound with the chemical formula . It is structurally related to benzene, with one methine group replaced by a nitrogen atom. It is a highly flammable, weakly alkaline, water-miscible liquid with a d ...

, diethyl ether

Diethyl ether, or simply ether, is an organic compound in the ether class with the formula , sometimes abbreviated as (see Pseudoelement symbols). It is a colourless, highly volatile, sweet-smelling ("ethereal odour"), extremely flammable liq ...

, and diethyl sulfide

Diethyl sulfide (British English: diethyl sulphide) is an organosulfur compound with the chemical formula . It is a colorless, malodorous liquid. Although a common thioether, it has few applications.

Preparation

Diethyl sulfide is a by-product ...

. The enthalpies of adduct formation and the IR frequency shifts accompanying adduct formation have been studied. Phenol is classified as a hard acid which is compatible with the ''C''/''E'' ratio of the ''ECW'' model with ''E''A = 2.27 and ''C''A = 1.07. The relative acceptor strength of phenol toward a series of bases, versus other Lewis acids, can be illustrated by C-B plots.

Phenoxide anion

The phenoxide anion is a strongnucleophile

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

with a nucleophilicity

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they are ...

comparable to the one of carbanions or tertiary amines. It can react at both its oxygen or carbon sites as an ambident nucleophile (see HSAB theory

HSAB concept is a jargon for "hard and soft Lewis acids and bases, (Lewis) acids and bases". HSAB is widely used in chemistry for explaining stability of chemical compound, compounds, reaction mechanisms and pathways. It assigns the terms 'hard' o ...

). Generally, oxygen attack of phenoxide anions is kinetically favored, while carbon-attack is thermodynamically preferred (see Thermodynamic versus kinetic reaction control

Thermodynamic reaction control or kinetic reaction control in a chemical reaction can decide the composition in a reaction product mixture when competing pathways lead to different products and the reaction conditions influence the conversion (che ...

). Mixed oxygen/carbon attack and by this a loss of selectivity is usually observed if the reaction rate reaches diffusion control.

Tautomerism

keto-enol tautomerism

In organic chemistry, alkenols (shortened to enols) are a type of reactive structure or intermediate in organic chemistry that is represented as an alkene ( olefin) with a hydroxyl group attached to one end of the alkene double bond (). The te ...

with its unstable keto tautomer cyclohexadienone, but only a tiny fraction of phenol exists as the keto form. The equilibrium constant for enolisation is approximately 10−13, which means only one in every ten trillion molecules is in the keto form at any moment. The small amount of stabilisation gained by exchanging a C=C bond for a C=O bond is more than offset by the large destabilisation resulting from the loss of aromaticity. Phenol therefore exists essentially entirely in the enol form. 4, 4' Substituted cyclohexadienone can undergo a dienone–phenol rearrangement in acid conditions and form stable 3,4‐disubstituted phenol.

Phenoxides are enolate

In organic chemistry, enolates are organic anions derived from the deprotonation of carbonyl () compounds. Rarely isolated, they are widely used as reagents in the synthesis of organic compounds.

Bonding and structure

Enolate anions are electr ...

s stabilised by aromaticity

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic ( ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to saturate ...

. Under normal circumstances, phenoxide is more reactive at the oxygen position, but the oxygen position is a "hard" nucleophile whereas the alpha-carbon positions tend to be "soft".

Reactions

Phenol is highly reactive toward

Phenol is highly reactive toward electrophilic aromatic substitution

Electrophilic aromatic substitution is an organic reaction in which an atom that is attached to an aromatic system (usually hydrogen) is replaced by an electrophile. Some of the most important electrophilic aromatic substitutions are aromatic ni ...

. The enhance nucleophilicity is attributed to donation pi electron

In chemistry, pi bonds (π bonds) are covalent chemical bonds, in each of which two lobes of an orbital on one atom overlap with two lobes of an orbital on another atom, and in which this overlap occurs laterally. Each of these atomic orbitals ...

density from O into the ring. Many groups can be attached to the ring, via halogenation

In chemistry, halogenation is a chemical reaction that entails the introduction of one or more halogens into a compound. Halide-containing compounds are pervasive, making this type of transformation important, e.g. in the production of polymers, ...

, acylation

In chemistry, acylation (or alkanoylation) is the chemical reaction in which an acyl group () is added to a compound. The compound providing the acyl group is called the acylating agent.

Because they form a strong electrophile when treated with ...

, sulfonation Aromatic sulfonation is an organic reaction in which a hydrogen atom on an arene is replaced by a sulfonic acid functional group in an electrophilic aromatic substitution. Aryl sulfonic acids are used as detergents, dye, and drugs.

Stoichiometry an ...

, and related processes. Phenol's ring is so strongly activated that bromination and chlorination lead readily to polysubstitution. Phenol reacts with dilute nitric acid at room temperature to give a mixture of 2-nitrophenol and 4-nitrophenol while with concentrated nitric acid, additional nitro groups are introduced, e.g. to give 2,4,6-trinitrophenol

Picric acid is an organic compound with the formula (O2N)3C6H2OH. Its IUPAC name is 2,4,6-trinitrophenol (TNP). The name "picric" comes from el, πικρός (''pikros''), meaning "bitter", due to its bitter taste. It is one of the most acidic ...

.

Aqueous solutions of phenol are weakly acidic and turn blue litmus slightly to red. Phenol is neutralized by sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and alkali ...

forming sodium phenate or phenolate, but being weaker than carbonic acid, it cannot be neutralized by sodium bicarbonate

Sodium bicarbonate (IUPAC name: sodium hydrogencarbonate), commonly known as baking soda or bicarbonate of soda, is a chemical compound with the formula NaHCO3. It is a salt composed of a sodium cation ( Na+) and a bicarbonate anion ( HCO3−) ...

or sodium carbonate

Sodium carbonate, , (also known as washing soda, soda ash and soda crystals) is the inorganic compound with the formula Na2CO3 and its various hydrates. All forms are white, odourless, water-soluble salts that yield moderately alkaline solutions ...

to liberate carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

.

:benzoyl chloride

Benzoyl chloride, also known as benzenecarbonyl chloride, is an organochlorine compound with the formula . It is a colourless, fuming liquid with an irritating odour, and consists of a benzene ring () with an acyl chloride () substituent. It is ...

are shaken in presence of dilute sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula NaOH. It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly caustic base and alkali ...

solution, phenyl benzoate

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic compound, cyclic group of atoms with the formula carbon, C6hydrogen, H5, and is often represented by the symbol Ph. Phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as ...

is formed. This is an example of the Schotten–Baumann reaction

The Schotten–Baumann reaction is a method to synthesize amides from amines and acid chlorides:

Schotten–Baumann reaction also refers to the conversion of acid chloride to esters. The reaction was first described in 1883 by German chemists ...

:

:benzene

Benzene is an organic chemical compound with the molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. Because it contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms, ...

when it is distilled with zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodi ...

dust or when its vapour is passed over granules of zinc at 400 °C:

:diazomethane

Diazomethane is the chemical compound CH2N2, discovered by German chemist Hans von Pechmann in 1894. It is the simplest diazo compound. In the pure form at room temperature, it is an extremely sensitive explosive yellow gas; thus, it is almost u ...

in the presence of boron trifluoride

Boron trifluoride is the inorganic compound with the formula BF3. This pungent, colourless, and toxic gas forms white fumes in moist air. It is a useful Lewis acid and a versatile building block for other boron compounds.

Structure and bondin ...

(), anisole

Anisole, or methoxybenzene, is an organic compound with the formula CH3OC6H5. It is a colorless liquid with a smell reminiscent of anise seed, and in fact many of its derivatives are found in natural and artificial fragrances. The compound is ...

is obtained as the main product and nitrogen gas as a byproduct.

:Production

Because of phenol's commercial importance, many methods have been developed for its production, but the cumene process is the dominant technology.Cumene process

Accounting for 95% of production (2003) is the

Accounting for 95% of production (2003) is the cumene process

The cumene process (cumene-phenol process, Hock process) is an industrial process for synthesizing phenol and acetone from benzene and propylene. The term stems from cumene (isopropyl benzene), the intermediate material during the process. It was i ...

, also called Hock process. It involves the partial oxidation

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

of cumene

Cumene (isopropylbenzene) is an organic compound that contains a benzene ring with an isopropyl substituent. It is a constituent of crude oil and refined fuels. It is a flammable colorless liquid that has a boiling point of 152 °C. Nearl ...

(isopropylbenzene) via the Hock rearrangement

Hock may refer to:

Common meanings:

* Hock (wine), a type of wine

* Hock (anatomy), part of an animal's leg

* To leave an item with a pawnbroker

People:

* Hock (surname)

* Richard "Hock" Walsh (1948-1999), Canadian blues singer

Other uses:

* A ...

: Compared to most other processes, the cumene process uses relatively mild conditions and relatively inexpensive raw materials. For the process to be economical, both phenol and the acetone by-product must be in demand. In 2010, worldwide demand for acetone was approximately 6.7 million tonnes, 83 percent of which was satisfied with acetone produced by the cumene process.

A route analogous to the cumene process begins with cyclohexylbenzene

Cyclohexylbenzene is the organic compound with the structural formula C6H5-C6H11. It is a derivative of benzene with a cyclohexyl substituent (C6H11). It is a colorless liquid.

Formation

Cyclohexylbenzene is produced by the acid-catalyzed alkyla ...

. It is oxidized

Redox (reduction–oxidation, , ) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of substrate change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is the gain of electrons or a d ...

to a hydroperoxide

Hydroperoxides or peroxols are Chemical compound, compounds containing the hydroperoxide functional group (ROOH). If the R is organic, the compounds are called organic hydroperoxides. Such compounds are a subset of organic peroxides, which have t ...

, akin to the production of cumene hydroperoxide

Cumene hydroperoxide is the organic compound with the formula C6H5CMe2OOH (Me = CH3). An oily liquid, it is classified as an organic hydroperoxide. Products of decomposition of cumene hydroperoxide are methylstyrene, acetophenone, and cumyl al ...

. Via the Hock rearrangement, cyclohexylbenzene hydroperoxide cleaves to give phenol and cyclohexanone

Cyclohexanone is the organic compound with the formula (CH2)5CO. The molecule consists of six-carbon cyclic molecule with a ketone functional group. This colorless oily liquid has an odor reminiscent of acetone. Over time, samples of cyclohexan ...

. Cyclohexanone is an important precursor to some nylon

Nylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers composed of polyamides ( repeating units linked by amide links).The polyamides may be aliphatic or semi-aromatic.

Nylon is a silk-like thermoplastic, generally made from petro ...

s.

Oxidation of benzene and toluene

The direct oxidation ofbenzene

Benzene is an organic chemical compound with the molecular formula C6H6. The benzene molecule is composed of six carbon atoms joined in a planar ring with one hydrogen atom attached to each. Because it contains only carbon and hydrogen atoms, ...

() to phenol is theoretically possible and of great interest, but it has not been commercialized:

:Nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide (dinitrogen oxide or dinitrogen monoxide), commonly known as laughing gas, nitrous, or nos, is a chemical compound, an oxide of nitrogen with the formula . At room temperature, it is a colourless non-flammable gas, and has a ...

is a potentially "green" oxidant that is a more potent oxidant than O2. Routes for the generation of nitrous oxide however remain uncompetitive.

An electrosynthesis

Electrosynthesis in chemistry is the synthesis of chemical compounds in an electrochemical cell. Compared to ordinary redox reaction, electrosynthesis sometimes offers improved selectivity and yields. Electrosynthesis is actively studied as a scien ...

employing alternating current

Alternating current (AC) is an electric current which periodically reverses direction and changes its magnitude continuously with time in contrast to direct current (DC) which flows only in one direction. Alternating current is the form in whic ...

gives phenol from benzene.

The oxidation of toluene

Toluene (), also known as toluol (), is a substituted aromatic hydrocarbon. It is a colorless, water-insoluble liquid with the smell associated with paint thinners. It is a mono-substituted benzene derivative, consisting of a methyl group (CH3) at ...

, as developed by Dow Chemical

The Dow Chemical Company, officially Dow Inc., is an American multinational chemical corporation headquartered in Midland, Michigan, United States. The company is among the three largest chemical producers in the world.

Dow manufactures plastics ...

, involves copper-catalyzed reaction of molten sodium benzoate with air:

:Older methods

Early methods relied on extraction of phenol from coal derivatives or the hydrolysis of benzene derivatives.Hydrolysis of benzenesulfonic acid

An early commercial route, developed byBayer

Bayer AG (, commonly pronounced ; ) is a German multinational corporation, multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company and one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world. Headquartered in Leverkusen, Bayer's areas of busi ...

and Monsanto

The Monsanto Company () was an American agrochemical and agricultural biotechnology corporation founded in 1901 and headquartered in Creve Coeur, Missouri. Monsanto's best known product is Roundup, a glyphosate-based herbicide, developed in th ...

in the early 1900s, begins with the reaction of a strong base with benzenesulfonic acid

Benzenesulfonic acid (conjugate base benzenesulfonate) is an organosulfur compound with the formula C6 H6 O3 S. It is the simplest aromatic sulfonic acid. It forms white deliquescent sheet crystals or a white waxy solid that is soluble in water ...

. The conversion is represented by this idealized equation:Wittcoff, H.A., Reuben, B.G. Industrial Organic Chemicals in Perspective. Part One: Raw Materials and Manufacture. Wiley-Interscience, New York. 1980.

:Hydrolysis of chlorobenzene

Chlorobenzene

Chlorobenzene is an aromatic organic compound with the chemical formula C6H5Cl. This colorless, flammable liquid is a common solvent and a widely used intermediate in the manufacture of other chemicals.

Uses

Historical

The major use of chlorob ...

can be hydrolyzed to phenol using base (Dow process

The Dow process is the electrolytic method of bromine extraction from brine, and was Herbert Henry Dow's second revolutionary process for generating bromine commercially.

This process was patented in 1891. In the original invention, bromide-conta ...

) or steam (Raschig–Hooker process

The Raschig–Hooker process is a chemical process for the production of chlorobenzene and phenol.

The Raschig–Hooker process was patented by Friedrich Raschig, a German chemist and politician also known for the Raschig process, the Olin Rasch ...

):

:Coal pyrolysis

Phenol is also a recoverable byproduct ofcoal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when dea ...

pyrolysis.Franck, H.-G., Stadelhofer, J.W. Industrial Aromatic Chemistry. Springer-Verlag, New York. 1988. pp. 148-155. In the Lummus Process Lummus may refer to:

* J. E. Lummus and J. N. Lummus, bankers who moved to Miami in 1895

*Lummus Company, manufacturer of cotton gins, Savannah Georgia

* Lummus Global, a company of Chicago Bridge & Iron Company

* Lummus Island, one of the three is ...

, the oxidation of toluene to benzoic acid

Benzoic acid is a white (or colorless) solid organic compound with the formula , whose structure consists of a benzene ring () with a carboxyl () substituent. It is the simplest aromatic carboxylic acid. The name is derived from gum benzoin, wh ...

is conducted separately.

Miscellaneous methods

Phenyldiazonium

Benzenediazonium tetrafluoroborate is an organic compound with the formula 6H5N2F4. It is a salt of a diazonium cation and tetrafluoroborate. It exists as a colourless solid that is soluble in polar solvents. It is the parent member of the ary ...

salts hydrolyze to phenol. The method is of no commercial interest since the precursor is expensive.

:Salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H4CO2H. A colorless, bitter-tasting solid, it is a precursor to and a metabolite of aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid). It is a plant hormone, and has been listed by the EPA Toxic Substance ...

decarboxylates to phenol.

Uses

The major uses of phenol, consuming two thirds of its production, involve its conversion to precursors for plastics.Condensation

Condensation is the change of the state of matter from the gas phase into the liquid phase, and is the reverse of vaporization. The word most often refers to the water cycle. It can also be defined as the change in the state of water vapor to ...

with acetone gives bisphenol-A

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a chemical compound primarily used in the manufacturing of various plastics. It is a colourless solid which is soluble in most common organic solvents, but has very poor solubility in water. BPA is produced on an industrial s ...

, a key precursor to polycarbonate

Polycarbonates (PC) are a group of thermoplastic polymers containing carbonate groups in their chemical structures. Polycarbonates used in engineering are strong, tough materials, and some grades are optically transparent. They are easily work ...

s and epoxide

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether () with a three-atom ring. This ring approximates an equilateral triangle, which makes it strained, and hence highly reactive, more so than other ethers. They are produced on a large scale for ...

resins. Condensation of phenol, alkylphenols, or diphenols with formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section F ...

gives phenolic resin

Phenol formaldehyde resins (PF) or phenolic resins (also infrequently called phenoplasts) are synthetic polymers obtained by the reaction of phenol or substituted phenol with formaldehyde. Used as the basis for Bakelite, PFs were the first commerc ...

s, a famous example of which is Bakelite

Polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride, better known as Bakelite ( ), is a thermosetting phenol formaldehyde resin, formed from a condensation reaction of phenol with formaldehyde. The first plastic made from synthetic components, it was developed ...

. Partial hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a Catalysis, catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to redox, reduce or S ...

of phenol gives cyclohexanone

Cyclohexanone is the organic compound with the formula (CH2)5CO. The molecule consists of six-carbon cyclic molecule with a ketone functional group. This colorless oily liquid has an odor reminiscent of acetone. Over time, samples of cyclohexan ...

, a precursor to nylon

Nylon is a generic designation for a family of synthetic polymers composed of polyamides ( repeating units linked by amide links).The polyamides may be aliphatic or semi-aromatic.

Nylon is a silk-like thermoplastic, generally made from petro ...

. Nonionic detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with cleansing properties when in dilute solutions. There are a large variety of detergents, a common family being the alkylbenzene sulfonates, which are soap-like compounds that are more ...

s are produced by alkylation of phenol to give the alkylphenol

Alkylphenols are a family of organic compounds obtained by the alkylation of phenols. The term is usually reserved for commercially important propylphenol, butylphenol, amylphenol, heptylphenol, octylphenol, nonylphenol, dodecylphenol and related ...

s, e.g., nonylphenol

Nonylphenols are a family of closely related organic compounds composed of phenol bearing a 9 carbon-tail. Nonylphenols can come in numerous structures, all of which may be considered alkylphenols. They are used in manufacturing antioxidants, lub ...

, which are then subjected to ethoxylation

Ethoxylation is a chemical reaction in which ethylene oxide adds to a substrate. It is the most widely practiced alkoxylation, which involves the addition of epoxides to substrates.

In the usual application, alcohols and phenols are converted i ...

.

Phenol is also a versatile precursor to a large collection of drugs, most notably aspirin

Aspirin, also known as acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and/or inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions which aspirin is used to treat inc ...

but also many herbicide

Herbicides (, ), also commonly known as weedkillers, are substances used to control undesired plants, also known as weeds.EPA. February 201Pesticides Industry. Sales and Usage 2006 and 2007: Market Estimates. Summary in press releasMain page fo ...

s and pharmaceutical drug

A medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy (pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the medical field and re ...

s.

Phenol is a component in liquid–liquid phenol–chloroform extraction Phenol–chloroform extraction is a liquid-liquid extraction technique in molecular biology used to separate nucleic acids from proteins and lipids.

Process

Aqueous samples, lysed cells, or homogenised tissue are mixed with equal volumes of a pheno ...

technique used in molecular biology

Molecular biology is the branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecular basis of biological activity in and between cells, including biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactions. The study of chemical and physi ...

for obtaining nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

s from tissues or cell culture samples. Depending on the pH of the solution either DNA or RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

can be extracted.

Medical

Phenol is widely used as anantiseptic

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putre ...

. Its use was pioneered by Joseph Lister (see section).

From the early 1900s to the 1970s it was used in the production of carbolic soap

Carbolic soap, sometimes referred to as red soap, is a mildly antiseptic soap containing carbolic acid (phenol) and/or cresylic acid (cresol), both of which are phenols derived from either coal tar or petroleum sources.

History

In 1834, German c ...

. Concentrated phenol liquids are commonly used for permanent treatment of ingrown toe and finger nails, a procedure known as a chemical matrixectomy

Surgical treatments of ingrown toenails include a number of different options. If conservative treatment of a minor ingrown toenail does not succeed or if the ingrown toenail is severe, surgical management by a podiatrist is recommended. The i ...

. The procedure was first described by Otto Boll in 1945. Since that time it has become the chemical of choice for chemical matrixectomies performed by podiatrists.

Concentrated liquid phenol can be used topically as a local anesthetic for otology procedures, such as myringotomy and tympanotomy tube placement, as an alternative to general anesthesia or other local anesthetics. It also has hemostatic and antiseptic qualities that make it ideal for this use.

Phenol spray, usually at 1.4% phenol as an active ingredient, is used medically to treat sore throat. It is the active ingredient in some oral analgesics such as Chloraseptic

Chloraseptic is an American brand of oral analgesic that is produced by Tarrytown, New York-based Prestige Consumer Healthcare, used for the relief of sore throat and mouth pain. Its active ingredient is phenol (just in Sore Throat Spray, not in ...

spray, TCP and Carmex

Carmex is a brand of lip balm produced by Carma Laboratories, Inc. It is sold in jars, sticks, and squeezable containers.

History

Carma Laboratories, Inc. began in Wisconsin in the early 1930s when Alfred Woelbing began experimenting with creat ...

.

Niche uses

Phenol is so inexpensive that it attracts many small-scale uses. It is a component of industrialpaint stripper

Paint stripper, or paint remover, is a chemical product designed to remove paint, finishes, and coatings, while also cleaning the underlying surface.

The product's material safety data sheet provides more safety information than its product la ...

s used in the aviation industry for the removal of epoxy, polyurethane and other chemically resistant coatings.

Phenol derivatives have been used in the preparation of cosmetics

Cosmetics are constituted mixtures of chemical compounds derived from either natural sources, or synthetically created ones. Cosmetics have various purposes. Those designed for personal care and skin care can be used to cleanse or protect ...

including sunscreen

Sunscreen, also known as sunblock or sun cream, is a photoprotective topical product for the skin that mainly absorbs, or to a much lesser extent reflects, some of the sun's ultraviolet (UV) radiation and thus helps protect against sunburn and ...

s, hair coloring

Hair coloring, or hair dyeing, is the practice of changing the hair color. The main reasons for this are cosmetic: to cover gray or white hair, to change to a color regarded as more fashionable or desirable, or to restore the original hair color ...

s, and skin lightening

Skin whitening, also known as skin lightening and skin bleaching, is the practice of using chemical substances in an attempt to lighten the skin or provide an even skin color by reducing the melanin concentration in the skin. Several chemicals ha ...

preparations. However, due to safety concerns, phenol is banned from use in cosmetic products in the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

and Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

.

History

Phenol was discovered in 1834 byFriedlieb Ferdinand Runge

Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge (8 February 1794 – 25 March 1867) was a German analytical chemist. Runge identified the mydriatic (pupil dilating) effects of belladonna (deadly nightshade) extract, identified caffeine, and discovered the first coal ...

, who extracted it (in impure form) from coal tar

Coal tar is a thick dark liquid which is a by-product of the production of coke and coal gas from coal. It is a type of creosote. It has both medical and industrial uses. Medicinally it is a topical medication applied to skin to treat psoriasi ...

. Runge called phenol "Karbolsäure" (coal-oil-acid, carbolic acid). Coal tar remained the primary source until the development of the petrochemical industry

The petrochemical industry is concerned with the production and trade of petrochemicals. A major part is constituted by the plastics (polymer) industry. It directly interfaces with the petroleum industry, especially the downstream sector.

Compan ...

. The French chemist Auguste Laurent

Auguste Laurent (14 November 1807 – 15 April 1853) was a French chemist who helped in the founding of organic chemistry with his discoveries of anthracene, phthalic acid, and carbolic acid.

He devised a systematic nomenclature for organic chem ...

extracted phenol in its pure form, as a derivative of benzene, in 1841.

In 1836, Auguste Laurent coined the name "phène" for benzene; this is the root of the word "phenol" and "phenyl

In organic chemistry, the phenyl group, or phenyl ring, is a cyclic group of atoms with the formula C6 H5, and is often represented by the symbol Ph. Phenyl group is closely related to benzene and can be viewed as a benzene ring, minus a hydrogen ...

". In 1843, French chemist Charles Gerhardt coined the name "phénol".

The antiseptic

An antiseptic (from Greek ἀντί ''anti'', "against" and σηπτικός ''sēptikos'', "putrefactive") is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue/skin to reduce the possibility of infection, sepsis, or putre ...

properties of phenol were used by Sir Joseph Lister

Joseph Lister, 1st Baron Lister, (5 April 182710 February 1912) was a British surgeon, medical scientist, experimental pathologist and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery and preventative medicine. Joseph Lister revolutionised the craft of s ...

(1827–1912) in his pioneering technique of antiseptic surgery. Lister decided that the wounds themselves had to be thoroughly cleaned. He then covered the wounds with a piece of rag or lint covered in carbolic acid (phenol). The skin irritation caused by continual exposure to phenol eventually led to the introduction of aseptic (germ-free) techniques in surgery.

Joseph Lister was a student at University College London under Robert Liston, later rising to the rank of Surgeon at Glasgow Royal Infirmary. Lister experimented with cloths covered in carbolic acid after studying the works and experiments of his contemporary, Louis Pasteur in sterilizing various biological media. Lister was inspired to try to find a way to sterilize living wounds, which could not be done with the heat required by Pasteur's experiments. In examining Pasteur's research, Lister began to piece together his theory: that patients were being killed by germs. He theorized that if germs could be killed or prevented, no infection would occur. Lister reasoned that a chemical could be used to destroy the micro-organisms that cause infection.

Meanwhile, in Carlisle, England, officials were experimenting with sewage treatment using carbolic acid to reduce the smell of sewage cesspools. Having heard of these developments, and having himself previously experimented with other chemicals for antiseptic purposes without much success, Lister decided to try carbolic acid as a wound antiseptic. He had his first chance on August 12, 1865, when he received a patient: an eleven-year-old boy with a tibia bone fracture which pierced the skin of his lower leg. Ordinarily, amputation would be the only solution. However, Lister decided to try carbolic acid. After setting the bone and supporting the leg with splints, he soaked clean cotton towels in undiluted carbolic acid and applied them to the wound, covered with a layer of tin foil, leaving them for four days. When he checked the wound, Lister was pleasantly surprised to find no signs of infection, just redness near the edges of the wound from mild burning by the carbolic acid. Reapplying fresh bandages with diluted carbolic acid, the boy was able to walk home after about six weeks of treatment.

By 16 March 1867, when the first results of Lister's work were published in the Lancet, he had treated a total of eleven patients using his new antiseptic method. Of those, only one had died, and that was through a complication that was nothing to do with Lister's wound-dressing technique. Now, for the first time, patients with compound fractures were likely to leave the hospital with all their limbs intact :— Richard Hollingham, ''Blood and Guts: A History of Surgery'', p. 62

Before antiseptic operations were introduced at the hospital, there were sixteen deaths in thirty-five surgical cases. Almost one in every two patients died. After antiseptic surgery was introduced in the summer of 1865, there were only six deaths in forty cases. The mortality rate had dropped from almost 50 per cent to around 15 per cent. It was a remarkable achievement :— Richard Hollingham, ''Blood and Guts: A History of Surgery'', p. 63Phenol was the main ingredient of the Carbolic Smoke Ball, an ineffective device marketed in London in the 19th century as protection against influenza and other ailments, and the subject of the famous law case ''

Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company

''Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Company'' 892EWCA Civ 1is an English contract law decision by the English Court of Appeal">Court of Appeal, which held an advertisement containing certain terms to get a reward constituted a binding unilateral of ...

''.

Second World War

The toxic effect of phenol on the central nervous system, discussed below, causes sudden collapse and loss of consciousness in both humans and animals; a state of cramping precedes these symptoms because of the motor activity controlled by the central nervous system. Injections of phenol were used as a means of individual execution byNazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.''The Experiments''by Peter Tyson. NOVA It was originally used by the Nazis in 1939 as part of the

Aktion T4

(German, ) was a campaign of mass murder by involuntary euthanasia in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-war trials against doctors who had been involved in the killings. The name T4 is an abbreviation of 4, a street address of ...

euthanasia program.''The Nazi Doctors'', Chapter 14, Killing with Syringes: Phenol Injections. By Dr. Robert Jay Lifton The Germans learned that extermination of smaller groups was more economical by injection of each victim with phenol. Phenol injections were given to thousands of people.

Maximilian Kolbe

Maximilian Maria Kolbe (born Raymund Kolbe; pl, Maksymilian Maria Kolbe; 1894–1941) was a Polish Catholic priest and Conventual Franciscan friar who volunteered to die in place of a man named Franciszek Gajowniczek in the German death camp ...

was also killed with a phenol injection after surviving two weeks of dehydration and starvation in Auschwitz

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

when he volunteered to die in place of a stranger

''A Stranger'' ( hr, Obrana i zaštita; ) is a 2013 Croatian drama film directed by Bobo Jelčić.

Cast

* Bogdan Diklić — Slavko

* Nada Đurevska — Milena

* Ivana Roščić — Zehra

* Rakan Rushaidat — Krešo

* Vinko Kraljević — Mil ...

. Approximately one gram is sufficient to cause death.

Occurrences

Phenol is a normal metabolic product, excreted in quantities up to 40 mg/L in human urine. Thetemporal gland

Temporins are a family of peptides isolated originally from the skin secretion of the European red frog, ''Rana temporaria''. Peptides belonging to the temporin family have been isolated also from closely related North American frogs, such as ''R ...

secretion of male elephant

Elephants are the largest existing land animals. Three living species are currently recognised: the African bush elephant, the African forest elephant, and the Asian elephant. They are the only surviving members of the family Elephantidae an ...

s showed the presence of phenol and 4-methylphenol

''para''-Cresol, also 4-methylphenol, is an organic compound with the formula CH3C6H4(OH). It is a colourless solid that is widely used intermediate in the production of other chemicals. It is a derivative of phenol and is an isomer of O-Cres ...

during musth

Musth or must (from Persian, )''The Oxford Dictionary and Thesaurus: American edition'', published 1996 by Oxford University Press; p. 984 is a periodic condition in bull (male) elephants characterized by aggressive behavior and accompanied by ...

.

It is also one of the chemical compounds found in castoreum

Castoreum is a yellowish exudate from the castor sacs of mature beavers. Beavers use castoreum in combination with urine to scent mark their territory. Both beaver sexes have a pair of castor sacs and a pair of anal glands, located in two cavities ...

. This compound is ingested from the plants the beaver eats.

Occurrence in whisky

Phenol is a measurable component in the aroma and taste of the distinctive Islay scotch whisky, generally ~30 ppm, but it can be over 160ppm in the maltedbarley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

used to produce whisky

Whisky or whiskey is a type of distilled alcoholic beverage made from fermented grain mash. Various grains (which may be malted) are used for different varieties, including barley, corn, rye, and wheat. Whisky is typically aged in wooden c ...

. This amount is different from and presumably higher than the amount in the distillate.

Biodegradation

''Cryptanaerobacter phenolicus

''Cryptanaerobacter phenolicus'' is a gram-positive anaerobic bacterial species in the genus ''Cryptanaerobacter''.

The genus ''Cryptanaerobacter'' contains a single species, namely ''C. phenolicus'' (Type species of the genus).; New Latin noun ...

'' is a bacterium species that produces benzoate

Benzoic acid is a white (or colorless) solid organic compound with the formula , whose structure consists of a benzene ring () with a carboxyl () substituent. It is the simplest aromatic carboxylic acid. The name is derived from gum benzoin, wh ...

from phenol via 4-hydroxybenzoate

4-Hydroxybenzoic acid, also known as ''p''-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHBA), is a monohydroxybenzoic acid, a phenolic derivative of benzoic acid. It is a white crystalline solid that is slightly soluble in water and chloroform but more soluble in polar ...

. ''Rhodococcus phenolicus

''Rhodococcus phenolicus'' is a bacterium species in the genus ''Rhodococcus''. ''Phenolicus'' comes from New Latin noun ''phenol'' -''olis'', phenol; Latin masculine gender

In linguistics, grammatical gender system is a specific form of no ...

'' is a bacterium species able to degrade phenol as sole carbon source.

Toxicity

Phenol and its vapors are corrosive to the eyes, the skin, and the respiratory tract. Its corrosive effect on skin and mucous membranes is due to a protein-degenerating effect. Repeated or prolonged skin contact with phenol may causedermatitis

Dermatitis is inflammation of the skin, typically characterized by itchiness, redness and a rash. In cases of short duration, there may be small blisters, while in long-term cases the skin may become thickened. The area of skin involved can v ...

, or even second and third-degree burns. Inhalation of phenol vapor may cause lung edema

Edema, also spelled oedema, and also known as fluid retention, dropsy, hydropsy and swelling, is the build-up of fluid in the body's Tissue (biology), tissue. Most commonly, the legs or arms are affected. Symptoms may include skin which feels t ...

. The substance may cause harmful effects on the central nervous system and heart, resulting in dysrhythmia, seizure

An epileptic seizure, informally known as a seizure, is a period of symptoms due to abnormally excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain. Outward effects vary from uncontrolled shaking movements involving much of the body with los ...

s, and coma

A coma is a deep state of prolonged unconsciousness in which a person cannot be awakened, fails to respond normally to painful stimuli, light, or sound, lacks a normal wake-sleep cycle and does not initiate voluntary actions. Coma patients exhi ...

. The kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blood ...

s may be affected as well. Long-term or repeated exposure of the substance may have harmful effects on the liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

and kidney

The kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped organs found in vertebrates. They are located on the left and right in the retroperitoneal space, and in adult humans are about in length. They receive blood from the paired renal arteries; blood ...

s. There is no evidence that phenol causes cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

in humans. Besides its hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the physical property of a molecule that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water (known as a hydrophobe). In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, th ...

effects, another mechanism for the toxicity of phenol may be the formation of phenoxyl

In chemistry, the alkoxy group is an alkyl group which is singularly bonded to oxygen; thus . The range of alkoxy groups is vast, the simplest being methoxy (). An ethoxy group () is found in the organic compound ethyl phenyl ether (, also kn ...

radicals.

Since phenol is absorbed through the skin relatively quickly, systemic poisoning can occur in addition to the local caustic burns. Resorptive poisoning by a large quantity of phenol can occur even with only a small area of skin, rapidly leading to paralysis of the central nervous system and a severe drop in body temperature. The for oral toxicity is less than 500 mg/kg for dogs, rabbits, or mice; the minimum lethal human dose was cited as 140 mg/kg. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services states the fatal dose for ingestion of phenol is from 1 to 32 g.

Chemical burn

A chemical burn occurs when living tissue is exposed to a corrosive substance (such as a strong acid, base or oxidizer) or a cytotoxic agent (such as mustard gas, lewisite or arsine). Chemical burns follow standard burn classification and may ca ...

s from skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other cuticle, animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have diffe ...

exposures can be decontaminated by washing with polyethylene glycol

Polyethylene glycol (PEG; ) is a polyether compound derived from petroleum with many applications, from industrial manufacturing to medicine. PEG is also known as polyethylene oxide (PEO) or polyoxyethylene (POE), depending on its molecular we ...

, isopropyl alcohol

Isopropyl alcohol (IUPAC name propan-2-ol and also called isopropanol or 2-propanol) is a colorless, flammable organic compound with a pungent alcoholic odor. As an isopropyl group linked to a hydroxyl group (chemical formula ) it is the simple ...

, or perhaps even copious amounts of water. Removal of contaminated clothing is required, as well as immediate hospital

A hospital is a health care institution providing patient treatment with specialized health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically has an emerge ...

treatment for large splashes. This is particularly important if the phenol is mixed with chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane, is an organic compound with chemical formula, formula Carbon, CHydrogen, HChlorine, Cl3 and a common organic solvent. It is a colorless, strong-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to ...

(a commonly used mixture in molecular biology for DNA and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

purification). Phenol is also a reproductive toxin causing increased risk of miscarriage and low birth weight indicating retarded development in utero.

Phenols

The word ''phenol'' is also used to refer to any compound that contains a six-memberedaromatic

In chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property of cyclic ( ring-shaped), ''typically'' planar (flat) molecular structures with pi bonds in resonance (those containing delocalized electrons) that gives increased stability compared to satur ...

ring, bonded directly to a hydroxyl group

In chemistry, a hydroxy or hydroxyl group is a functional group with the chemical formula and composed of one oxygen atom covalently bonded to one hydrogen atom. In organic chemistry, alcohols and carboxylic acids contain one or more hydroxy g ...

(-OH). Thus, phenols are a class of organic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The ...

s of which the phenol discussed in this article is the simplest member.

See also

*Bamberger rearrangement The Bamberger rearrangement is the chemical reaction of phenylhydroxylamines with strong aqueous acid, which will rearrange to give 4-aminophenols. It is named for the German chemist Eugen Bamberger (1857–1932).

The starting phenylhydroxylam ...

*Claisen rearrangement

The Claisen rearrangement is a powerful carbon–carbon bond-forming chemical reaction discovered by Rainer Ludwig Claisen. The heating of an allyl vinyl ether will initiate a ,3sigmatropic rearrangement to give a γ,δ-unsaturated carbonyl, d ...

*Cresol

Cresols (also hydroxytoluene or cresylic acid) are a group of aromatic organic compounds. They are widely-occurring phenols (sometimes called ''phenolics'') which may be either natural or manufactured. They are also categorized as methylphenols. ...

*Fries rearrangement

The Fries rearrangement, named for the German chemist Karl Theophil Fries, is a rearrangement reaction of a phenolic ester to a hydroxy aryl ketone by catalysis of Lewis acids.

It involves migration of an acyl group of phenol ester to the aryl ...

*Polyphenol

Polyphenols () are a large family of naturally occurring organic compounds characterized by multiples of phenol units. They are abundant in plants and structurally diverse. Polyphenols include flavonoids, tannic acid, and ellagitannin, some of ...

References

External links

International Chemical Safety Card 0070

{{Authority control Antiseptics Commodity chemicals Hazardous air pollutants Oxoacids Phenyl compounds 1834 in science