Huntington Garden on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Huntington Library, Art Museum and Botanical Gardens, known as The Huntington, is a collections-based educational and research institution established by Henry E. Huntington (1850–1927) and

As a landowner,

As a landowner,

The library building was designed in 1920 by the southern California architect

The library building was designed in 1920 by the southern California architect

The European collection, consisting largely of 18th- and 19th-century British & French paintings, sculptures and decorative arts, is housed in The Huntington Art Gallery, the original Huntington residence. The permanent installation also includes selections from the Arabella D. Huntington Memorial Art Collection, which contains Italian and Northern Renaissance paintings and a spectacular collection of 18th-century French tapestries, porcelain, and furniture. Some of the best known works in the European collection include ''

The European collection, consisting largely of 18th- and 19th-century British & French paintings, sculptures and decorative arts, is housed in The Huntington Art Gallery, the original Huntington residence. The permanent installation also includes selections from the Arabella D. Huntington Memorial Art Collection, which contains Italian and Northern Renaissance paintings and a spectacular collection of 18th-century French tapestries, porcelain, and furniture. Some of the best known works in the European collection include ''

The Huntington's

The Huntington's  The Camellia Collection, recognized as an International Camellia Garden of Excellence, includes nearly eighty different

The Camellia Collection, recognized as an International Camellia Garden of Excellence, includes nearly eighty different

A

A

The Desert Garden, one of the world's largest and oldest outdoor collections of

The Desert Garden, one of the world's largest and oldest outdoor collections of

In 1911, art dealer George Turner Marsh (who also created the

In 1911, art dealer George Turner Marsh (who also created the

File:Huntington Lib Flowers.jpg, Colorful flowers

File:Jungle garden.JPG, Jungle Garden

File:Herb Garden, Spring Blooms, Huntington.jpg, Spring bloom in the Herb Garden

File:huntington_library_japanese_gong.jpg, Japanese Garden bell

File:Huntington SW05.jpg, Classical Garden Pavilion

File:Huntington SW06.jpg, Fountain on the Great Lawn

File:Blooming roses at Huntington Library in Pasadena, California. April 2022 20220418 160140.jpg, Blooming Roses in April 2022

File:Huntington SW07.jpg, Neo-Classical garden sculpture

File:Cactus in Huntington Library Botanical Garden, California.jpg, Succulent plants in the Desert Garden

File:Rose Garden at Huntington Library in Pasadena, California. April 2022 20220418 160351.jpg, Rose Garden in bloom, April 2022

File:Rose at Huntington Library garden.JPG,

File:Ficus auriculata leaves.jpg.jpg, Ficus auriculata leavesA Californian's Guide to the Trees Among Us, Matt Ritter, 2011, Heyday, Berkeley, CA,

File:Agathis_robusta_at_the_Huntington_Library_Rose_Garden_in_San_Marino_California.jpg, Agathis robusta located in the Huntington Library Rose Garden in San Marino, California

Virtual tour

* Hathi Trust

Publications of the Huntington Library

fulltext, various dates * * {{Authority control Art museums and galleries in California Botanical gardens in California Libraries in Los Angeles County, California Museums in Los Angeles County, California Art in Greater Los Angeles Parks in Los Angeles County, California San Marino, California Sculpture gardens, trails and parks in California Chinese gardens Former private collections in the United States Gardens in California Historic house museums in California Japanese gardens in California Landscape design history of the United States Literary archives in the United States Open-air museums in California Outdoor sculptures in Greater Los Angeles Rare book libraries in the United States Research libraries in the United States Special collections libraries in the United States San Gabriel Valley San Rafael Hills Libraries established in 1928 Museums established in 1928 1928 establishments in California Elmer Grey buildings Myron Hunt buildings Neoclassical architecture in California Tourist attractions in Los Angeles County, California Greenhouses in California Herb gardens Gilded Age mansions

Arabella Huntington

Arabella Duval Huntington (née Yarrington; 1850/1851 – September 16, 1924) was an American philanthropist and once known as the richest woman in the country. She was the force behind the art collection that is housed at the Huntington Librar ...

(c.1851–1924) in San Marino, California

San Marino is a residential city in Los Angeles County, California, United States. It was incorporated on April 25, 1913. At the 2010 census the population was 13,147. The city is one of the wealthiest places in the nation in terms of househol ...

, United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. In addition to the library, the institution houses an extensive art collection with a focus on 18th- and 19th-century European art

The art of Europe, or Western art, encompasses the history of art, history of visual art in Europe. European prehistoric art started as mobile Upper Paleolithic rock art, rock and cave painting and petroglyph art and was characteristic of the ...

and 17th- to mid-20th-century American art

Visual art of the United States or American art is visual art made in the United States or by U.S. artists. Before colonization there were many flourishing traditions of Native American art, and where the Spanish colonized Spanish Colonial arc ...

. The property also includes approximately of specialized botanical landscaped gardens, most notably the "Japanese Garden", the "Desert Garden", and the "Chinese Garden" (Liu Fang Yuan).

History

As a landowner,

As a landowner, Henry Edwards Huntington

Henry Edwards Huntington (February 27, 1850 – May 23, 1927) was an American railroad magnate and collector of art and rare books. Huntington settled in Los Angeles, where he owned the Pacific Electric Railway as well as substantial real estate ...

(1850–1927) played a major role in the growth of Southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most po ...

. Huntington was born in 1850, in Oneonta, New York

Oneonta ( ) is a city in southern Otsego County, New York, United States. It is one of the northernmost cities of the Appalachian Region. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, Oneonta had a population of 13,079. Its nickname is "City of the Hil ...

, and was the nephew and heir of Collis P. Huntington

Collis Potter Huntington (October 22, 1821 – August 13, 1900) was an American industrialist and railway magnate. He was one of the Big Four of western railroading (along with Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker) who invested ...

(1821–1900), one of the famous "Big Four" railroad tycoons of 19th century California history

The California Historical Society (CHS) is the official historical society of California. It was founded in 1871, by a group of prominent Californian intellectuals at Santa Clara University. It was officially designated as the Californian state ...

. In 1892, Huntington relocated to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

with his first wife, Mary Alice Prentice, as well as their four children. He divorced Mary Alice Prentice in 1906; in 1913, he married his uncle's widow, Arabella Huntington

Arabella Duval Huntington (née Yarrington; 1850/1851 – September 16, 1924) was an American philanthropist and once known as the richest woman in the country. She was the force behind the art collection that is housed at the Huntington Librar ...

(1851–1924), relocating from the financial and political center of Northern California

Northern California (colloquially known as NorCal) is a geographic and cultural region that generally comprises the northern portion of the U.S. state of California. Spanning the state's northernmost 48 counties, its main population centers incl ...

, San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, to the state's newer southern major metropolis, Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

. He purchased a property of more than that was then known as the "San Marino Ranch" and went on to purchase other large tracts of land in the Pasadena

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commercial district.

Its ...

and Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

areas of Los Angeles County

Los Angeles County, officially the County of Los Angeles, and sometimes abbreviated as L.A. County, is the most populous county in the United States and in the U.S. state of California, with 9,861,224 residents estimated as of 2022. It is the ...

for urban and suburban development. As president of the Pacific Electric Railway Company

The Pacific Electric Railway Company, nicknamed the Red Cars, was a privately owned mass transit system in Southern California consisting of electrically powered streetcars, interurban cars, and buses and was the largest electric railway system ...

, the regional streetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport are ...

and public transit system for the Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

metropolitan area and southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most po ...

and also of the Los Angeles Railway Company, (later the Southern California Railway

Southern California Railway was formed on November 7, 1889. it was formed by consolidation of

California Southern Railroad Company, the California Central Railway Company, and the Redondo Beach Railway Company.

A second consolidation and reformi ...

), he spearheaded urban and regional transportation efforts to link together far-flung communities, supporting growth of those communities as well as promoting commerce, recreation and tourism. He was one of the founders of the City of San Marino

The City of San Marino ( it, Città di San Marino; also known simply as San Marino and locally as Città) is the capital city of the Republic of San Marino. It has a population of 4,061. It is on the western slopes of San Marino's highest poi ...

, incorporated in 1913.

Huntington's interest in art was influenced in large part by his second wife, Arabella Huntington

Arabella Duval Huntington (née Yarrington; 1850/1851 – September 16, 1924) was an American philanthropist and once known as the richest woman in the country. She was the force behind the art collection that is housed at the Huntington Librar ...

(1851–1924), and with art experts to guide him, he benefited from a post-World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

European market that was "ready to sell almost anything". Before his death in 1927, Huntington amassed "far and away the greatest group of 18th-century British portraits ever assembled by any one man". In accordance with Huntington's will, the collection, then worth $50 million, was opened to the public in 1928.

On October 17, 1985, a fire erupted in an elevator shaft of the Huntington Art Gallery and destroyed Sir Joshua Reynolds

Sir Joshua Reynolds (16 July 1723 – 23 February 1792) was an English painter, specialising in portraits. John Russell said he was one of the major European painters of the 18th century. He promoted the "Grand Style" in painting which depend ...

's 1777 portrait of Mrs. Edwin Lascelles. After a year-long, $1 million refurbishing project, the Huntington Gallery reopened in 1986, with its artworks cleaned of soot and stains. Most of the funds for the cleanup and refurbishing of the Georgian mansion and its artworks came from donations from the Michael J. Connell Foundation, corporations and individuals. Both the Federal art-supporting establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts

The National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) is an independent agency of the United States federal government that offers support and funding for projects exhibiting artistic excellence. It was created in 1965 as an independent agency of the federal ...

and the National Endowment for the Humanities

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) is an independent federal agency of the U.S. government, established by thNational Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965(), dedicated to supporting research, education, preserv ...

gave emergency grants, the former of $17,500 to "support conservation and other related costs resulting from a serious fire at the Gallery of Art", and the latter of $30,000 to "support the restoration of several fire-damaged works of art that depict the story of Western culture."

On September 5, 2019, The Huntington kicked off a year-long celebration of its centennial year with exhibitions, special programs, initiatives, a special Huntington 100th rose, and a float in the 2020 Rose Parade

The Rose Parade, also known as the Tournament of Roses Parade (or simply the Tournament of Roses), is an annual parade held mostly along Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena, California, United States, on New Year's Day (or on Monday, January 2 if N ...

in nearby Pasadena, California

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commercial district.

I ...

.

Management

The current executive leaders of The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens are: * President: Karen R. Lawrence * Chief Financial Officer: Janet Alberti * Chief Human Resources Officer: Misty Bennett * Director of the Library: Sandra Ludig Brooke * Director of the Botanical Gardens: James Folsom (retired), Nicole Cavender (May 17, 2021) * Director of the Art Museum: Christina Nielsen * Vice Presidents and other executive leaders: Heather Hart, Steve Hindle, Thomas Polansky, Randy Shulman, Susan Turner-Lowe, and Elizabeth (Elee) Wood With an endowment of more than $400 million (and half a billion dollars raised between 2001 and 2013), the Huntington is among the wealthiest cultural institutions in the United States. It has undertaken major restorations and construction including a $60 million education and visitors center opened in 2015. Each year some 1,700 scholars conduct research there, and 600,000 people visit.Library

The library building was designed in 1920 by the southern California architect

The library building was designed in 1920 by the southern California architect Myron Hunt

Myron Hubbard Hunt (February 27, 1868 – May 26, 1952) was an American architect whose numerous projects include many noted landmarks in Southern California and Evanston, Illinois. Hunt was elected a Fellow in the American Institute of Archi ...

in the Mediterranean Revival

Mediterranean Revival is an architectural style introduced in the United States, Canada, and certain other countries in the 19th century. It incorporated references from Spanish Renaissance, Spanish Colonial, Italian Renaissance, French Colonial ...

style. Hunt's previous commissions for Mr. and Mrs. Huntington included the Huntington's residence in San Marino

San Marino (, ), officially the Republic of San Marino ( it, Repubblica di San Marino; ), also known as the Most Serene Republic of San Marino ( it, Serenissima Repubblica di San Marino, links=no), is the fifth-smallest country in the world an ...

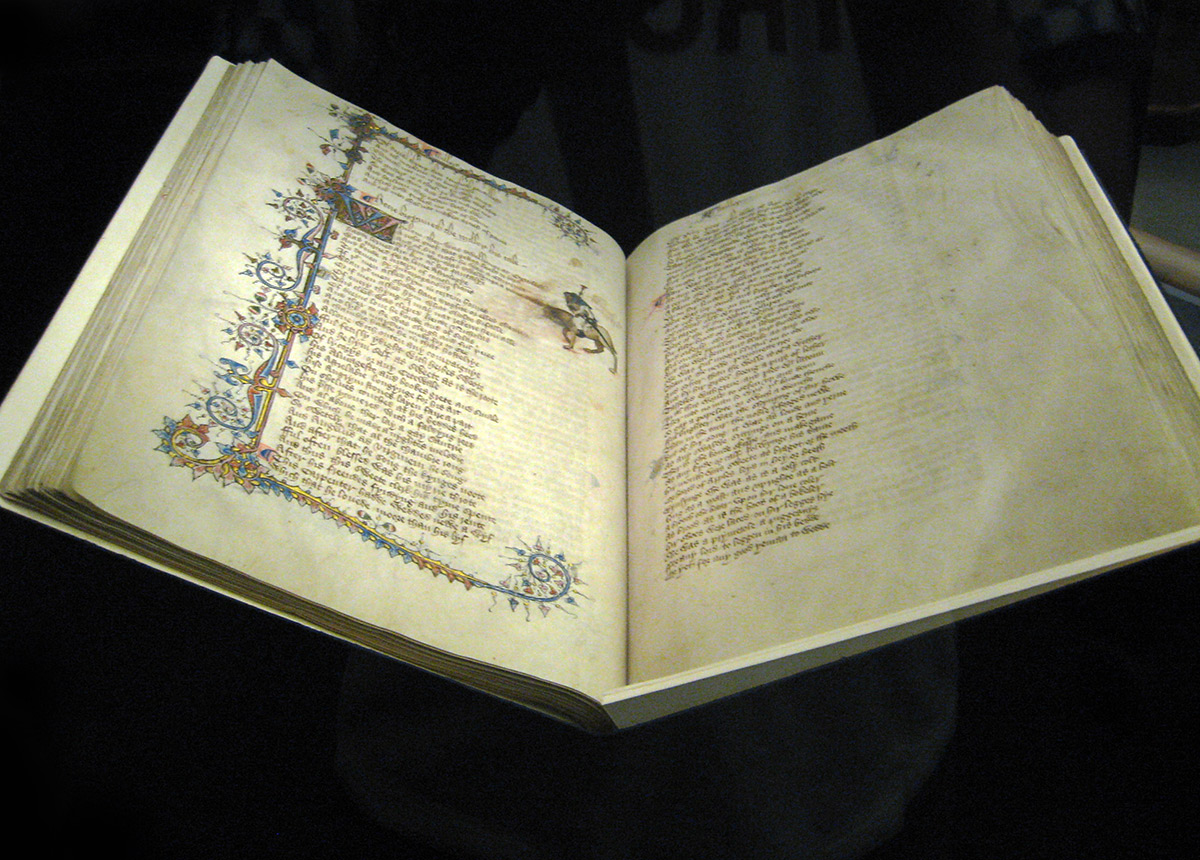

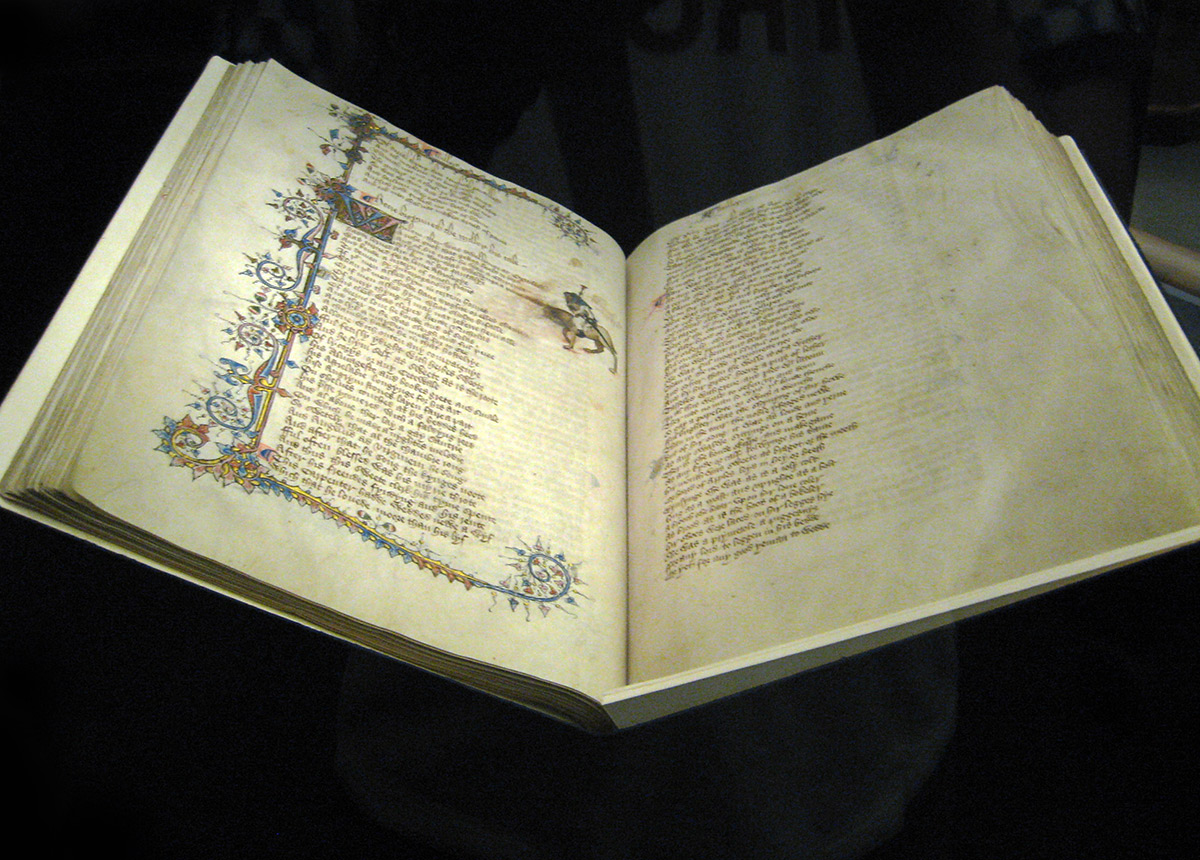

in 1909, and the Huntington Hotel in 1914. The library contains a substantial collection of rare books and manuscripts, concentrated in the fields of British and American history, literature, art, and the history of science. Spanning from the 11th century to the present, the library's holdings contain 7 million manuscript items, over 400,000 rare books, and over a million photographs, prints, and other ephemera

Ephemera are transitory creations which are not meant to be retained or preserved. Its etymological origins extends to Ancient Greece, with the common definition of the word being: "the minor transient documents of everyday life". Ambiguous in ...

. Highlights include one of eleven vellum copies of the Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42) was the earliest major book printed using mass-produced movable metal type in Europe. It marked the start of the "Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of printed b ...

known to exist, the Ellesmere manuscript

The Ellesmere Chaucer, or Ellesmere Manuscript of the Canterbury Tales, is an early 15th-century illuminated manuscript of Geoffrey Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales'', owned by the Huntington Library, in San Marino, California (EL 26 C 9). It is consi ...

of Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for '' The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

(ca. 1410), and letters and manuscripts by George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, and Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

. It is the only library in the world with the first two quartos of ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

''; it holds the manuscript of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

's autobiography, Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

's personal copy of his ''Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

'' with annotations in Newton's own hand, the first seven drafts of Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural su ...

's ''Walden

''Walden'' (; first published in 1854 as ''Walden; or, Life in the Woods'') is a book by American transcendentalist writer Henry David Thoreau. The text is a reflection upon the author's simple living in natural surroundings. The work is part ...

'', John James Audubon

John James Audubon (born Jean-Jacques Rabin; April 26, 1785 – January 27, 1851) was an American self-trained artist, naturalist, and ornithologist. His combined interests in art and ornithology turned into a plan to make a complete pictoria ...

's '' Birds of America'', and first editions and manuscripts from authors such as Charles Bukowski

Henry Charles Bukowski ( ; born Heinrich Karl Bukowski, ; August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994) was a German-American poet, novelist, and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural, and economic ambience of his adopted ...

, Jack London

John Griffith Chaney (January 12, 1876 – November 22, 1916), better known as Jack London, was an American novelist, journalist and activist. A pioneer of commercial fiction and American magazines, he was one of the first American authors to ...

, Alexander Pope

Alexander Pope (21 May 1688 O.S. – 30 May 1744) was an English poet, translator, and satirist of the Enlightenment era who is considered one of the most prominent English poets of the early 18th century. An exponent of Augustan literature, ...

, William Blake

William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his life, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual art of the Romantic Age. ...

, Mark Twain

Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, 1835 – April 21, 1910), known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. He was praised as the "greatest humorist the United States has p ...

, and William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

.Huntington Library ''In Fact'', 2012–2013

The Library's Main Exhibition Hall showcases some of the most outstanding rare books and manuscripts in the collection, while the West Hall of the Library hosts rotating exhibitions. The Dibner Hall of the History of Science is a permanent exhibition on the history of science with a focus on astronomy, natural history, medicine, and light.

With the 2006 acquisition of the Burndy Library

Burndy Library is one of the world's largest collections of books on the history of science and technology.

History

Founded in 1941 in Norwalk, Connecticut by the electrical engineer, industrialist, and historian Bern Dibner, the library holdin ...

, a collection of nearly 60,000 items, the Huntington became one of the top institutions in the world for the study of the history of science and technology

The history of science and technology (HST) is a field of history that examines the understanding of the natural world (science) and the ability to manipulate it (technology) at different points in time. This academic discipline also studies the c ...

.

On December 14, 2022 the library announced they had acquired the archive of American author Thomas Pynchon

Thomas Ruggles Pynchon Jr. ( , ; born May 8, 1937) is an American novelist noted for his dense and complex novels. His fiction and non-fiction writings encompass a vast array of subject matter, genres and themes, including history, music, scie ...

.

Research

Use of the collection for research is restricted to qualified scholars, generally requiring a doctoral degree or at least candidacy for the PhD, and two letters of recommendation from known scholars. Through a rigorous peer-review program, the institution awards approximately 150 grants to scholars in the fields of history, literature, art, and the history of science. The Huntington also hosts numerous scholarly events, lectures, conferences, and workshops. In September 1991, then-director William A. Moffett announced that the library's photographic archive of theDead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the nor ...

would be available to all qualified scholars, not just those approved by the international team of editors that had so long limited access to a chosen few. The collection consists of 3,000 photographs of all the original scrolls.

Through a partnership with the University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in C ...

, The Huntington has established two research centers: the USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute and the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West The Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West is an educational institute created in 2004 by a partnership between the Huntington Library and the University of Southern California. Its goal is to bring together writers, students, scholars, ...

.

Art collections

The Huntington's collections are displayed in permanent installations housed in the Huntington Art Gallery and Virginia Steele Scott Gallery of American Art. Special temporary exhibitions are mounted in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery, with smaller, focused exhibitions displayed in the Works on Paper Room in the Huntington Art Gallery and the Susan and Stephen Chandler Wing of the Scott Galleries. In addition the gallery also hosts different exhibitions of photography throughout the year including those about different social and political subjects.European art

The European collection, consisting largely of 18th- and 19th-century British & French paintings, sculptures and decorative arts, is housed in The Huntington Art Gallery, the original Huntington residence. The permanent installation also includes selections from the Arabella D. Huntington Memorial Art Collection, which contains Italian and Northern Renaissance paintings and a spectacular collection of 18th-century French tapestries, porcelain, and furniture. Some of the best known works in the European collection include ''

The European collection, consisting largely of 18th- and 19th-century British & French paintings, sculptures and decorative arts, is housed in The Huntington Art Gallery, the original Huntington residence. The permanent installation also includes selections from the Arabella D. Huntington Memorial Art Collection, which contains Italian and Northern Renaissance paintings and a spectacular collection of 18th-century French tapestries, porcelain, and furniture. Some of the best known works in the European collection include ''The Blue Boy

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

'' by Thomas Gainsborough

Thomas Gainsborough (14 May 1727 (baptised) – 2 August 1788) was an English portrait and landscape painter, draughtsman, and printmaker. Along with his rival Sir Joshua Reynolds, he is considered one of the most important British artists of ...

, '' Pinkie'' by Thomas Lawrence

Sir Thomas Lawrence (13 April 1769 – 7 January 1830) was an English portrait painter and the fourth president of the Royal Academy. A child prodigy, he was born in Bristol and began drawing in Devizes, where his father was an innkeeper at t ...

, and ''Madonna and Child

In art, a Madonna () is a representation of Mary, either alone or with her child Jesus. These images are central icons for both the Catholic and Orthodox churches. The word is (archaic). The Madonna and Child type is very prevalent in ...

'' by Rogier van der Weyden

Rogier van der Weyden () or Roger de la Pasture (1399 or 140018 June 1464) was an early Netherlandish painter whose surviving works consist mainly of religious triptychs, altarpieces, and commissioned single and diptych portraits. He was highly ...

.

American art

Complementing the European collections is the Huntington's American art holdings, a collection of paintings, prints, drawings, sculptures, and photographs dating from the 17th to the mid-20th century. The institution did not begin collecting American art until 1979, when it received a gift of 50 paintings from the Virginia Steele Scott Foundation. Consequently, The Virginia Steele Scott Gallery of American Art was established in 1984. In 2009, the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries were expanded, refurbished, and reinstalled. The new showcase, a $1.6 million project designed to give the Huntington's growing American art collection more space and visibility, combines the original, 1984 American gallery with the Lois and Robert F. Erburu Gallery, a modern classical addition designed by Los Angeles architect Frederick Fisher. Highlights among the American art collections include ''Breakfast in Bed'' byMary Cassatt

Mary Stevenson Cassatt (; May 22, 1844June 14, 1926) was an American painter and printmaker. She was born in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh's North Side), but lived much of her adult life in France, where she befriended Edgar De ...

, ''The Long Leg'' by Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967) was an American realist painter and printmaker. While he is widely known for his oil paintings, he was equally proficient as a watercolorist and printmaker in etching.

Hopper created subdued drama ...

, ''Small Crushed Campbell's Soup Can (Beef Noodle)'' by Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol (; born Andrew Warhola Jr.; August 6, 1928 – February 22, 1987) was an American visual artist, film director, and producer who was a leading figure in the visual art movement known as pop art. His works explore the relationsh ...

, and ''Global Loft (Spread)'' by Robert Rauschenberg

Milton Ernest "Robert" Rauschenberg (October 22, 1925 – May 12, 2008) was an American painter and graphic artist whose early works anticipated the Pop art movement. Rauschenberg is well known for his Combines (1954–1964), a group of artwor ...

. As of 2014, the collection numbers some 12,000 works, ninety percent of them drawings, photographs and prints.

In 2014, the library acquired the Millard Sheets

Millard Owen Sheets (June 24, 1907 – March 31, 1989) was an American artist, teacher, and architectural designer. He was one of the earliest of the California Scene Painting artists and helped define the art movement. Many of his large-scale bu ...

mural ''Southern California landscape'' (1934), the dining room wall painting originally painted for homeowners Fred H. and Bessie Ranke in the Hollywood Hills

The Hollywood Hills are a residential neighborhood in the central region of Los Angeles, California.

Geography

The Hollywood Hills straddle the Cahuenga Pass within the Santa Monica Mountains.

The neighborhood touches Studio City, Univer ...

of Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

.

Acquisitions

In 1999, the Huntington acquired the collection of materials relating to Arts and Crafts artist and designerWilliam Morris

William Morris (24 March 1834 – 3 October 1896) was a British textile designer, poet, artist, novelist, architectural conservationist, printer, translator and socialist activist associated with the British Arts and Crafts Movement. He ...

amassed by Sanford and Helen Berger, comprising stained glass, wallpaper, textiles, embroidery, drawings, ceramics, more than 2,000 books, original woodblock prints, and the complete archives of Morris's decorative arts firm Morris & Co. and its predecessor Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. These materials formed the foundation for the 2002 exhibit "William Morris: Creating the Useful and the Beautiful".

In 2005, actor Steve Martin

Stephen Glenn Martin (born August 14, 1945) is an American actor, comedian, writer, producer, and musician. He has won five Grammy Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, and was awarded an Honorary Academy Award in 2013. Additionally, he was nominated ...

gave $1 million to the Huntington to support exhibitions and acquisitions of American art, with three-quarters of the money to be spent on exhibitions and the rest on purchases of artworks. In 2009, Andy Warhol

Andy Warhol (; born Andrew Warhola Jr.; August 6, 1928 – February 22, 1987) was an American visual artist, film director, and producer who was a leading figure in the visual art movement known as pop art. His works explore the relationsh ...

's painting ''Small Crushed Campbell's Soup Can (Beef Noodle)'' (1962) as well as group of the artist's ''Brillo Boxes'' were donated by the estate of Robert Shapazian, the founding director of Gagosian Gallery

Gagosian is a contemporary art gallery owned and directed by Larry Gagosian. The gallery exhibits some of the most influential artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. There are 16 gallery spaces: five in New York City; three in London; two in Par ...

in Beverly Hills. In 2011, a $1.75 million acquisition fund for post-1945 American art was established by unidentified patrons in honor of the late Shapazian. The first purchase from the fund was the painting ''Global Loft (Spread)'' (1979) by Robert Rauschenberg

Milton Ernest "Robert" Rauschenberg (October 22, 1925 – May 12, 2008) was an American painter and graphic artist whose early works anticipated the Pop art movement. Rauschenberg is well known for his Combines (1954–1964), a group of artwor ...

.

In 2012, the museum acquired its first major work by an African-American artist when it purchased a 22-foot-long carved redwood panel from 1937 by sculptor Sargent Claude Johnson

Sargent Claude Johnson (October 7, 1888 – October 10, 1967) was one of the first African-American artists working in California to achieve a national reputation.

.

Botanical gardens

The Huntington's

The Huntington's botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens, an ...

s cover and showcase plants from around the world. Huntington worked to make them thrive in the generous California climate. Today his many projects of horticulture live on, providing opportunities for botanical research and for enjoyment. The gardens are divided into more than a dozen themes, including the Australian Garden, Camellia Collection, Children's Garden, Desert Garden, Herb Garden, Japanese Garden

are traditional gardens whose designs are accompanied by Japanese aesthetics and philosophical ideas, avoid artificial ornamentation, and highlight the natural landscape. Plants and worn, aged materials are generally used by Japanese garden desig ...

, Lily Ponds, North Vista, Palm Garden, Rose Garden

A rose garden or rosarium is a garden or park, often open to the public, used to present and grow various types of garden roses, and sometimes rose species. Most often it is a section of a larger garden. Designs vary tremendously and roses m ...

, the Shakespeare Garden, Subtropical and Jungle Garden, and the Chinese Garden

The Chinese garden is a landscape garden style which has evolved over three thousand years. It includes both the vast gardens of the Chinese emperors and members of the imperial family, built for pleasure and to impress, and the more intimate ...

(Liu Fang Yuan 流芳園 or the Garden of Flowing Fragrance).

The Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory for Botanical Science has a large tropical plant collection, as well as a carnivorous plant

Carnivorous plants are plants that derive some or most of their nutrients from trapping and consuming animals or protozoans

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryot ...

s wing. The Huntington has a program to protect and propagate endangered plant species. In 1999, 2002, 2009, 2010, 2014, 2018, 2019, 2020 and 2021, specimens of ''Amorphophallus titanum

''Amorphophallus'' (from Ancient Greek , "without form, misshapen" + ''phallos'', "penis", referring to the shape of the prominent spadix) is a large genus of some 200 tropical and subtropical tuberous herbaceous plants from the ''Arum'' family ...

'', or the odiferous "corpse flower", bloomed at the facility. There were a total of fourteen corpse flowers bloomed at Huntington since 1999. Three flowers opened in July, 2021.

The Camellia Collection, recognized as an International Camellia Garden of Excellence, includes nearly eighty different

The Camellia Collection, recognized as an International Camellia Garden of Excellence, includes nearly eighty different camellia

''Camellia'' (pronounced or ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Theaceae. They are found in eastern and southern Asia, from the Himalayas east to Japan and Indonesia. There are more than 220 described species, with some controversy ...

species and some 1,200 cultivated varieties, many of them rare and historic. The Rose Garden contains approximately 1,200 cultivars

A cultivar is a type of Horticulture, cultivated plant that people have selected for desired phenotypic trait, traits and when Plant propagation, propagated retain those traits. Methods used to propagate cultivars include: division, root and st ...

(4,000 individual plants) arranged historically to trace the development of roses from ancient to modern times.

Chinese Garden (Liu Fang Yuan 流芳園)

A

A Chinese garden

The Chinese garden is a landscape garden style which has evolved over three thousand years. It includes both the vast gardens of the Chinese emperors and members of the imperial family, built for pleasure and to impress, and the more intimate ...

, the largest outside of China, was dedicated on February 26, 2008 after artisans from Suzhou, China

Suzhou (; ; Suzhounese: ''sou¹ tseu¹'' , Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Soochow, is a major city in southern Jiangsu province, East China. Suzhou is the largest city in Jiangsu, and a major economic center and focal point of trade ...

spent some six months at Huntington to construct the first phase of the newest facility. On at the northwest corner of the Huntington, the garden features man-made lakes ("Pond of Reflected Greenery" and "Lake of Reflected Fragrance") with pavilions connected by bridges. Unique Chinese names are assigned to many of the facilities in the garden, such as the tea house

A teahouse (mainly Asia) or tearoom (also tea room) is an establishment which primarily serves tea and other light refreshments. A tea room may be a room set aside in a hotel especially for serving afternoon tea, or may be an establishment whic ...

, known as the "Hall of the Jade Camellia". Other pavilions are the "Love for the Lotus Pavilion", "Terrace of the Jade Mirror", and "Pavilion of the Three Friends". The initial phase cost $18.3 million to build.

The second phase, which includes the "Clear and Transcendent Pavilion (Qing Yue Tai 清越臺)", "Lingering Clouds Peak (Liu Yun Xiu 留雲岫)" (with a waterfall), "Waveless Boat (Bu Bo Xiao Ting 不波小艇)", "Crossing through Fragrance" bridge and the "Cloud Steps" bridge, opened on March 8, 2014. There were other pavilions, including the "Flowery Brush Studio", and structures completed under phase two. A place to display its large collections of penjing

''Penjing'', also known as ''penzai'', is the ancient Chinese art of depicting artistically formed trees, other plants, and landscapes in miniature.

Penjing generally fall into one of three categories:

* Shumu penjing (樹木盆景): Tree penjin ...

and bonsai

Bonsai ( ja, 盆栽, , tray planting, ) is the Japanese art of growing and training miniature trees in pots, developed from the traditional Chinese art form of ''penjing''. Unlike ''penjing'', which utilizes traditional techniques to produce ...

has completed.

Desert Garden

cacti

A cactus (, or less commonly, cactus) is a member of the plant family Cactaceae, a family comprising about 127 genera with some 1750 known species of the order Caryophyllales. The word ''cactus'' derives, through Latin, from the Ancient Greek ...

and other succulents

In botany, succulent plants, also known as succulents, are plants with parts that are thickened, fleshy, and engorged, usually to retain water in arid climates or soil conditions. The word ''succulent'' comes from the Latin word ''sucus'', meani ...

, contains plants from extreme environments, many of which were acquired by Henry E. Huntington and William Hertrich (the garden curator). One of the Huntington's most botanically important gardens, the Desert Garden brings together a plant group largely unknown and unappreciated in the beginning of the 1900s. Containing a broad category of xerophyte

A xerophyte (from Ancient Greek language, Greek ξηρός ''xeros'' 'dry' + φυτόν ''phuton'' 'plant') is a species of plant that has adaptations to survive in an environment with little liquid water, such as a desert such as the Sahara or pl ...

s (arid

A region is arid when it severely lacks available water, to the extent of hindering or preventing the growth and development of plant and animal life. Regions with arid climates tend to lack vegetation and are called xeric or desertic. Most ar ...

ity-adapted plants), the Desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

Garden grew to preeminence and remains today among the world's finest, with more than 5,000 species.

Japanese Garden

In 1911, art dealer George Turner Marsh (who also created the

In 1911, art dealer George Turner Marsh (who also created the Japanese Tea Garden

are traditional gardens whose designs are accompanied by Japanese aesthetics and philosophical ideas, avoid artificial ornamentation, and highlight the natural landscape. Plants and worn, aged materials are generally used by Japanese garden desig ...

at the Golden Gate Park) sold his commercial Japanese tea garden to Henry E. Huntington to create the foundations of what is known today as the Japanese Garden. The garden was completed in 1912 and opened to the public in 1928. According to historian Kendall Brown, the garden consists of three gardens: the original stroll garden with koi

or more specifically , are colored varieties of the Amur carp ('' Cyprinus rubrofuscus'') that are kept for decorative purposes in outdoor koi ponds or water gardens.

Koi is an informal name for the colored variants of ''C. rubrofuscus'' ke ...

-filled ponds and a drum or moon bridge, the raked-gravel dry garden added in 1968, and the traditionally landscaped tea garden.

In addition, the gardens feature a large bell, the authentic ceremonial teahouse Seifu-an (the Arbor of Pure Breeze), a fully furnished Japanese house, the Zen Garden, and the bonsai collections with hundreds of trees. The Bonsai Courts at the Huntington is the home of the Golden State Bonsai

Bonsai ( ja, 盆栽, , tray planting, ) is the Japanese art of growing and training miniature trees in pots, developed from the traditional Chinese art form of ''penjing''. Unlike ''penjing'', which utilizes traditional techniques to produce ...

Federation Southern Collection. Another ancient Japanese art form can be found at the Harry Hirao Suiseki

In traditional Japanese culture, are small naturally occurring or shaped rocks which are appreciated for their aesthetic or decorative value. They are similar to Chinese scholar's rocks.Cousins, Craig. (2006) ''Bonsai Master Class,'' p. 244

...

Court, where visitors can touch the suiseki or viewing stones.

Other gardens

*Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

n Garden

* Camellia

''Camellia'' (pronounced or ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Theaceae. They are found in eastern and southern Asia, from the Himalayas east to Japan and Indonesia. There are more than 220 described species, with some controversy ...

Garden

* Children's Garden

* Conservatory

* Herb

In general use, herbs are a widely distributed and widespread group of plants, excluding vegetables and other plants consumed for macronutrients, with savory or aromatic properties that are used for flavoring and garnishing food, for medicinal ...

Garden

* Jungle

A jungle is land covered with dense forest and tangled vegetation, usually in tropical climates. Application of the term has varied greatly during the past recent century.

Etymology

The word ''jungle'' originates from the Sanskrit word ''jaṅ ...

Garden

* Lily

''Lilium'' () is a genus of Herbaceous plant, herbaceous flowering plants growing from bulbs, all with large prominent flowers. They are the true lilies. Lilies are a group of flowering plants which are important in culture and literature in mu ...

Ponds

* Palm

Palm most commonly refers to:

* Palm of the hand, the central region of the front of the hand

* Palm plants, of family Arecaceae

**List of Arecaceae genera

* Several other plants known as "palm"

Palm or Palms may also refer to:

Music

* Palm (ba ...

Garden

* Ranch

A ranch (from es, rancho/Mexican Spanish) is an area of land, including various structures, given primarily to ranching, the practice of raising grazing livestock such as cattle and sheep. It is a subtype of a farm. These terms are most often ...

Garden

* Rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

Garden

* Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

Garden

* Subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Köppen climate classification, climate zones to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Geographical z ...

Garden

In popular culture

The Huntington Botanical Gardens were honored with a postal stamp as a part of the American Gardens stamps on May 13, 2020. The Desert Garden was featured. The gardens are frequently used as a filming location. Footage shot there has been included in: * ''Mame

MAME (formerly an acronym of Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator) is a free and open-source emulator designed to recreate the hardware of arcade game systems in software on modern personal computers and other platforms. Its intention is to preserve ...

'' (1974)

* " Only Yesterday" (music video) – Carpenters (1975)

* '' Midway'' (1976)

* ''Beverly Hills Cop II

''Beverly Hills Cop II'' is a 1987 American buddy cop action comedy film directed by Tony Scott, written by Larry Ferguson and Warren Skaaren, and starring Eddie Murphy. It is the sequel to the 1984 film ''Beverly Hills Cop'' and the second insta ...

'' (1987)

* '' Justice (Star Trek: The Next Generation)'' (1987)

* ''Heathers

''Heathers'' is a 1989 American black comedy film written by Daniel Waters and directed by Michael Lehmann, in both of their respective film debuts. The film stars Winona Ryder, Christian Slater, Shannen Doherty, Lisanne Falk, Kim Walker, and ...

'' (1988)

* " Ordinary World" (music video) – Duran Duran

Duran Duran () are an English Rock music, rock band formed in Birmingham in 1978 by singer and bassist Stephen Duffy, keyboardist Nick Rhodes and guitarist/bassist John Taylor (bass guitarist), John Taylor. With the addition of drummer Roger ...

(1993)

* ''Indecent Proposal

''Indecent Proposal'' is a 1993 American erotic drama film directed by Adrian Lyne and written by Amy Holden Jones. It is based on the 1988 novel by Jack Engelhard, in which a couple's marriage is disrupted by a stranger's offer of a million d ...

'' (1993)

* ''Beverly Hills Ninja

''Beverly Hills Ninja'' is a 1997 American martial arts comedy film directed by Dennis Dugan, written by Mark Feldberg and Mitch Klebanoff. The film stars Chris Farley, Nicollette Sheridan, Nathaniel Parker, with Chris Rock, and Robin Shou. The m ...

'' (1997)

* '' JAG'' (1997), used as the White House rose garden

* ''The Wedding Singer

''The Wedding Singer'' is a 1998 American romantic comedy film directed by Frank Coraci, written by Tim Herlihy, and produced by Robert Simonds and Jack Giarraputo. The film stars Adam Sandler, Drew Barrymore, and Christine Taylor, and tells the ...

'' (1998)

* ''Mystery Men

''Mystery Men'' is a 1999 American superhero comedy film directed by Kinka Usher (in his feature-length directorial debut) and written by Neil Cuthbert, loosely based on Bob Burden's ''Flaming Carrot Comics'', and starring Ben Stiller, Hank Azari ...

'' (1999)

* ''Charlie's Angels

''Charlie's Angels'' is an American crime drama television series that aired on ABC from September 22, 1976, to June 24, 1981, producing five seasons and 115 episodes. The series was created by Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts and was produced by Aa ...

'' (2000)

* ''The Wedding Planner

''The Wedding Planner'' is a 2001 American romantic comedy film directed by Adam Shankman, in his feature film directorial debut, written by Michael Ellis and Pamela Falk, and starring Jennifer Lopez and Matthew McConaughey.

Plot

Ambitious San ...

'' (2001)

* ''The Hot Chick

''The Hot Chick'' is a 2002 American comedy film written and directed by Tom Brady, with additional writing by Rob Schneider. Schneider stars as Clive Maxtone, a middle-aged criminal who switches bodies with mean-spirited cheerleader Jessica Spe ...

'' (2002)

* ''S1m0ne

''Simone'' (stylized as ''S1M0̸NE'') is a 2002 American satirical science fiction film written, produced, and directed by Andrew Niccol. It stars Al Pacino, Catherine Keener, Evan Rachel Wood, Rachel Roberts, Jay Mohr, and Winona Ryder. Th ...

'' (2002)

* ''Anger Management

Anger management is a psycho-therapeutic program for anger prevention and control. It has been described as deploying anger successfully.Schwarts, Gil. July 2006. Anger Management', July 2006 The Office Politic. Men's Health magazine. Emmaus, PA: ...

'' (2003)

* ''The West Wing

''The West Wing'' is an American serial (radio and television), serial political drama television series created by Aaron Sorkin that was originally broadcast on NBC from September 22, 1999, to May 14, 2006. The series is set primarily in the ...

'' (2003), used as the National Arboretum

* ''Intolerable Cruelty

''Intolerable Cruelty'' is a 2003 American romantic comedy film directed and co-written by Joel and Ethan Coen, and produced by Brian Grazer and the Coens. The script was written by Robert Ramsey and Matthew Stone and Ethan and Joel Coen, with the ...

'' (2003)

* ''Starsky & Hutch

''Starsky & Hutch'' is an American action television series, which consisted of a 72-minute pilot movie (originally aired as a ''Movie of the Week'' entry) and 92 episodes of 50 minutes each. The show was created by William Blinn (inspired by th ...

'' (2004)

* ''Monster-in-Law

''Monster-in-Law'' is a 2005 romantic comedy film directed by Robert Luketic, written by Anya Kochoff and starring Jennifer Lopez, Jane Fonda, Michael Vartan and Wanda Sykes. It marked a return to cinema for Fonda, being her first film in 15 year ...

'' (2005)

* ''Memoirs of a Geisha

''Memoirs of a Geisha'' is a historical fiction novel by American author Arthur Golden, published in 1997. The novel, told in first person perspective, tells the story of Nitta Sayuri and the many trials she faces on the path to becoming and wo ...

'' (2005)

* ''Serenity

Serenity may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Serenity'' (2019 film), a thriller starring Matthew McConaughey, Anne Hathaway and Diane Lane

* Sailor Moon (character), also known as Princess Serenity and Neo-Queen Serenity, in the ' ...

'' (2005)

* ''Ned's Declassified Field Trip'', the final episode of ''Ned's Declassified School Survival Guide

''Ned's Declassified School Survival Guide'' (sometimes shortened to ''Ned's Declassified'') is an American live action sitcom on Nickelodeon that debuted on the Nickelodeon Sunday night TEENick scheduling block on September 12, 2004. The series ...

'' (2007)

* '' National Treasure: Book of Secrets'' (2007), used as the White House rose garden

* ''CSI Miami

''CSI: Miami'' (''Crime Scene Investigation: Miami'') is an American police procedural drama television series that ran from September 23, 2002 until April 8, 2012 on CBS. Featuring David Caruso as Lieutenant Horatio Caine, Emily Procter as Dete ...

'', in '' You May Now Kill the Bride'' (2008)

* '' G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra'' (2009), used during the flashback fighting scenes between ten-year-old Snake Eyes and Storm Shadow.

* "A Beautiful End" (music video) – J.R. Richards

John Robert Richards later Reid-Richards (born April 30, 1967) is an American singer-songwriter, musician, record producer and television and film composer. Richards was the original lead singer and principal songwriter for the alternative ro ...

(2009)

* ''The Muppets

The Muppets are an American ensemble cast of puppet characters known for an absurdist, burlesque, and self-referential style of variety- sketch comedy. Created by Jim Henson in 1955, they are the focus of a media franchise that encompasses ...

'' (2011)

* ''Bridesmaids

Bridesmaids are members of the bride's party in a Western traditional wedding ceremony. A bridesmaid is typically a young woman and often a close friend or relative. She attends to the bride on the day of a wedding or marriage ceremony. Traditi ...

'' (2011), the driveway to Helen's bridal shower

* ''Parks and Recreation

''Parks and Recreation'' (also known as ''Parks and Rec'') is an American political satire mockumentary sitcom television series created by Greg Daniels and Michael Schur. The series aired on NBC from April 9, 2009, to February 24, 2015, for 125 ...

'', used as Five Mile Grounds, the new Eagleton park, in the episode "Pawnee Commons" (2012)

* ''The Good Place

''The Good Place'' is an American fantasy comedy television series created by Michael Schur. It premiered on NBC on September 19, 2016, and concluded on January 30, 2020, after four seasons and 53 episodes.

Although the plot evolves significa ...

'', as the afterlife's fictional setting (2016–2020)

*" Garden Song" by singer-songwriter Phoebe Bridgers

Phoebe Lucille Bridgers (born August 17, 1994) is an American musician, singer, songwriter, and record producer. She has released two solo albums, ''Stranger in the Alps'' (2017) and ''Punisher'' (2020), both of which received critical acclaim ...

mentions the Huntington by name.

Gallery

Rose

A rose is either a woody perennial flowering plant of the genus ''Rosa'' (), in the family Rosaceae (), or the flower it bears. There are over three hundred species and tens of thousands of cultivars. They form a group of plants that can be ...

File:Huntington Library Gardens Wisteria arbor, 2009.jpg, Wisteria

''Wisteria'' is a genus of flowering plants in the legume family, Fabaceae (Leguminosae), that includes ten species of woody twining vines that are native to China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, Southern Canada, the Eastern United States, and north o ...

arbor, April 2009

File:Water lily 1.jpg, Water lily

File:Snapdragons at Huntington Library garden.JPG, Snapdragons

''Antirrhinum'' is a genus of plants commonly known as dragon flowers, snapdragons and dog flower because of the flowers' fancied resemblance to the face of a dragon that opens and closes its mouth when laterally squeezed. They are native to r ...

See also

*List of botanical gardens in the United States

This list is intended to include all significant botanical gardens and arboretums in the United States.The Constance Perkins House

The Constance Perkins House is a house designed by Richard Neutra and built in Pasadena, California, United States, from 1952 to 1955.

Design and construction

In 1947, Constance Perkins started working as a professor of Art History at Occidental ...

, donated to the Library in 1991

* List of museums in California

This list of museums in California is a list of museums, defined for this context as institutions (including nonprofit organizations, government entities, and private businesses) that collect and care for objects of cultural, artistic, scientifi ...

References

Footnotes CitationsAdditional sources

*External links

*Virtual tour

* Hathi Trust

Publications of the Huntington Library

fulltext, various dates * * {{Authority control Art museums and galleries in California Botanical gardens in California Libraries in Los Angeles County, California Museums in Los Angeles County, California Art in Greater Los Angeles Parks in Los Angeles County, California San Marino, California Sculpture gardens, trails and parks in California Chinese gardens Former private collections in the United States Gardens in California Historic house museums in California Japanese gardens in California Landscape design history of the United States Literary archives in the United States Open-air museums in California Outdoor sculptures in Greater Los Angeles Rare book libraries in the United States Research libraries in the United States Special collections libraries in the United States San Gabriel Valley San Rafael Hills Libraries established in 1928 Museums established in 1928 1928 establishments in California Elmer Grey buildings Myron Hunt buildings Neoclassical architecture in California Tourist attractions in Los Angeles County, California Greenhouses in California Herb gardens Gilded Age mansions