Humphrey Winch on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir Humphrey Winch (1555–1625) was an English-born politician and

/ref>

judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

. He had a distinguished career in both Ireland and England, but his reputation was seriously damaged by the Leicester witch trials of 1616, which resulted in the hanging of several innocent women.

Family

He was born inBedfordshire

Bedfordshire (; abbreviated Beds) is a ceremonial county in the East of England. The county has been administered by three unitary authorities, Borough of Bedford, Central Bedfordshire and Borough of Luton, since Bedfordshire County Council wa ...

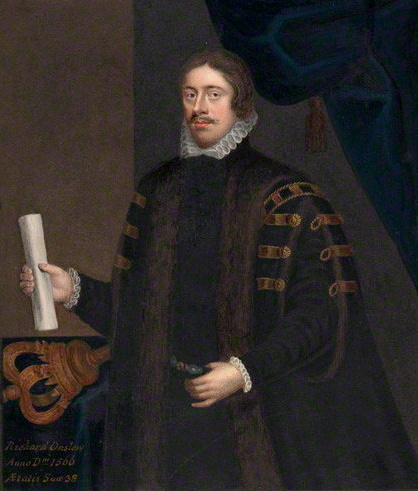

, second son of John Winch (died 1598) of Northill. He married Cicely Onslow, daughter of Richard Onslow (died 1571), Speaker of the House of Commons Speaker of the House of Commons is a political leadership position found in countries that have a House of Commons, where the membership of the body elects a speaker to lead its proceedings.

Systems that have such a position include:

*Speaker of ...

, and his wife Catherine Harding. They had two surviving children, including Onslow, who married a sister of Sir John Burgoyne, 1st Baronet

Sir John Burgoyne, 1st Baronet (c. 1592–1657) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1645 to 1648. He supported the Parliamentarian cause in the English Civil War.

Burgoyne was the son of Roger Burgoyne, of Sutton, B ...

, and was the father of Sir Humphrey Winch, 1st Baronet

Sir Humphrey Winch, 1st Baronet (3 January 1622 – December 1703) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons of England, House of Commons between 1660 and 1689.

Winch was the eldest son of Onslow Winch of Everton, Bedfordshire and ...

. Later notable descendants included Anne, Duchess of Cumberland and Strathearn

Anne, Duchess of Cumberland and Strathearn ( née Luttrell, later Horton; 24 January 1743 – 28 December 1808) was a member of the British royal family, the wife of Prince Henry, Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn. Her sister was Lady Elizab ...

.

Political career

He matriculated fromSt John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corpo ...

; was called to the Bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1581 and became a bencher of Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn is one of the four Inns of Court in London to which barristers of England and Wales belong and where they are called to the Bar. (The other three are Middle Temple, Inner Temple and Gray's Inn.) Lincoln ...

in 1596. He enjoyed the patronage of Oliver St John, 3rd Baron St John of Bletso

Oliver St John, 3rd Baron St John of Bletso (c. 1540–1618) was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1588 until 1596 when he inherited the peerage as Baron St John of Bletso.

St John was a son of Oliver St John, 1st Baron ...

. Through St John's influence, he was elected to the House of Commons as MP for Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population of the Bedford built-up area (including Biddenham and Kempston) was 106,940, making it the second-largest settlement in Bedfordshire, behind Luton, whilst ...

in 1593, and served in each successive Parliament up to 1606.

In the earlier part of his career in Parliament, he was identified with the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

faction in the Commons. He gave great offence to Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is sometimes referred to as the "Virgin Queen".

El ...

in 1593 by supporting a proposal by Sir Peter Wentworth

Sir Peter Wentworth (1529–1596) was a prominent Puritan leader in the Parliament of England. He was the elder brother of Paul Wentworth and entered as member for Barnstaple in 1571. He later sat for the Cornish borough of Tregony in 1578 and ...

, the chief spokesman in the Commons for the Puritans, to introduce a Bill to settle the royal succession

An order of succession or right of succession is the line of individuals necessitated to hold a high office when it becomes vacated such as head of state or an honour such as a title of nobility.barrister's chambers

In law, a barrister's chambers or barristers' chambers are the rooms used by a barrister or a group of barristers. The singular refers to the use by a sole practitioner whereas the plural refers to a group of barristers who, while acting as sol ...

at Lincoln's Inn. Compared to the fate of Wentworth, who was sent to the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is separa ...

and died there three years later, Winch's punishment was mild enough: he was forbidden to leave London for a time, but allowed to continue to attend Parliament. His disgrace was temporary, but thereafter he confined his speeches in the Commons to non-contentious matters. History of Parliament Online – Humphrey Winche/ref>

Judge

In 1606, despite his earlier conflict with the Crown, he was recommended to KingJames I James I may refer to:

People

*James I of Aragon (1208–1276)

*James I of Sicily or James II of Aragon (1267–1327)

*James I, Count of La Marche (1319–1362), Count of Ponthieu

*James I, Count of Urgell (1321–1347)

*James I of Cyprus (1334–13 ...

as a man who was suitable for judicial appointment, by reason of his legal ability and integrity. For this purpose, he was made a serjeant-at-law and knighted

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the Christian denomination, church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood ...

, then appointed Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer

The Chief Baron of the Irish Exchequer was the Baron (judge) who presided over the Court of Exchequer (Ireland). The Irish Court of Exchequer was a mirror of the equivalent court in England and was one of the four courts which sat in the buildin ...

.

He received glowing reports as a judge, being praised as "understanding and painstaking". Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

said that Winch's qualities of "quickness, industry and dispatch" made him a model for other judges to emulate. In 1607 he was one of four senior judges who became members of the King's Inns

The Honorable Society of King's Inns ( ir, Cumann Onórach Óstaí an Rí) is the "Inn of Court" for the Bar of Ireland. Established in 1541, King's Inns is Ireland's oldest school of law and one of Ireland's significant historical environment ...

, thus helping to revive an institution which had become almost moribund. He was conscientious in going on assize and was regular in attendance at the Court of Castle Chamber

The Court of Castle Chamber (which was sometimes simply called ''Star Chamber'') was an Irish court of special jurisdiction which operated in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

It was established by Queen Elizabeth I in 1571 to deal with ca ...

(the Irish equivalent of Star Chamber

The Star Chamber (Latin: ''Camera stellata'') was an English court that sat at the royal Palace of Westminster, from the late to the mid-17th century (c. 1641), and was composed of Privy Counsellors and common-law judges, to supplement the judic ...

). After two years he was promoted to the office of Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench in Ireland.

Winch, like many (though by no means all) transplanted English officials disliked the Irish climate and complained of its effect on his health. He also grumbled about the lack of staff to support him and the "humiliating" fees he received (although he did receive an initial payment of £100 towards his expenses). From 1610 onwards he was lobbying for a speedy return to England. Despite the reluctance of the Dublin Government to lose such a valued Crown servant, he was transferred to the English Court of Common Pleas

The Court of Common Pleas, or Common Bench, was a common law court in the English legal system that covered "common pleas"; actions between subject and subject, which did not concern the king. Created in the late 12th to early 13th century afte ...

in 1611. He returned to Ireland on official business in 1613, and was regarded as an expert on Irish matters, sitting on the Privy Council

A privy council is a body that advises the head of state of a state, typically, but not always, in the context of a monarchic government. The word "privy" means "private" or "secret"; thus, a privy council was originally a committee of the mon ...

committees on Irish affairs.

Leicester witch trials

''See main article:Leicester boy

The Leicester boy trial was one of Leicester's most notorious witchcraft cases, in which a thirteen-year-old boy publicly accused 15 women of causing a possession within him. The case took place in Husbands Bosworth, a small village not far from ...

''

Winch's illustrious reputation as a judge was dealt a serious blow by his conduct at the summer assizes in Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest settlement in the East Midlands.

The city l ...

in 1616. Fifteen women had been charged with witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

on the sole evidence of a young boy called John Smith, who claimed that they had possessed him. The judges, Winch and Ranulph Crewe

Sir Ranulph (or Ralulphe, Randolph, or Randall) Crew(e) (1558 – 3 January 1646) was an English judge and Chief Justice of the King's Bench.

Early life and career

Ranulph Crewe was the second son of John Crew of Nantwich, who is said to have ...

, found the boy to be a credible witness: while six of the accused were spared the death penalty in favour of a prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, English language in England, British English, Australian English, Australian, and Huron Historic Gaol, historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention cent ...

sentence, nine were condemned to death and hanged

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging in ...

. A month after the hangings King James I visited Leicester. The King had always shown a keen interest in witchcraft

Witchcraft traditionally means the use of magic or supernatural powers to harm others. A practitioner is a witch. In medieval and early modern Europe, where the term originated, accused witches were usually women who were believed to have us ...

, but, although he was a firm believer in the reality of witches, he could be sceptical about individual cases, and was quite shrewd in detecting impostors. He examined the boy John Smith and promptly declared him to be a fraud. The boy broke down and confessed that he had lied, and the five surviving convicts (one had already died) were released from prison.

Death

Despite the damage to his reputation caused by the witchcraft trial's fiasco, Winch remained on the bench until he died suddenly at Chancery Lane from a stroke in February 1625. An impressive memorial was raised to him in St Mary's Church, Everton. He apologised in his will to his wife for the "poor estate which I must leave her". She outlived him by three or four years. The inadequacy of his reward had been a constant theme of his for many years. Probably by the standards of Jacobean judges, his fortune was not large: but his estates were not negligible. In addition to Everton, he had an estate atPotton

Potton is a town and civil parish in the Central Bedfordshire district of Bedfordshire, England, about east of the county town Bedford. Its population in 2011 was 4,870. In 1783 the Great Fire of Potton destroyed a large part of the town. The ...

, Bedfordshire, and another at Gamlingay

Gamlingay is a village and civil parish in the South Cambridgeshire district of Cambridgeshire, England about west southwest of the county town of Cambridge.

The 2011 census gives the village's population as 3,247 and the civil parish's as 3,5 ...

in Cambridgeshire

Cambridgeshire (abbreviated Cambs.) is a Counties of England, county in the East of England, bordering Lincolnshire to the north, Norfolk to the north-east, Suffolk to the east, Essex and Hertfordshire to the south, and Bedfordshire and North ...

.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Winch, Humphrey English barristers People from Northill Witchcraft in England 1555 births 1625 deaths Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge English MPs 1593 English MPs 1597–1598 English MPs 1601 English MPs 1604–1611 Lords chief justice of Ireland 16th-century English lawyers Chief Barons of the Irish Exchequer