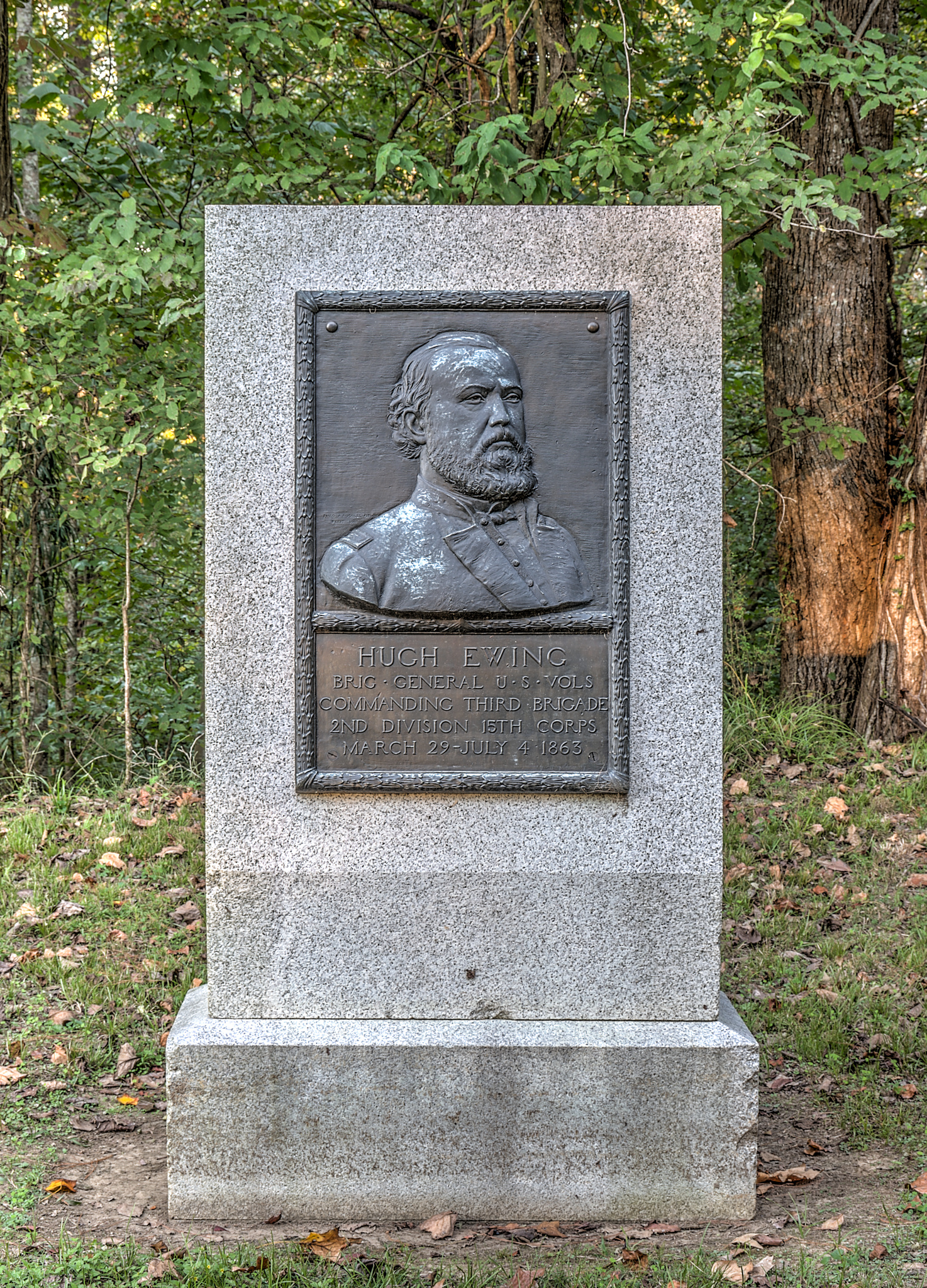

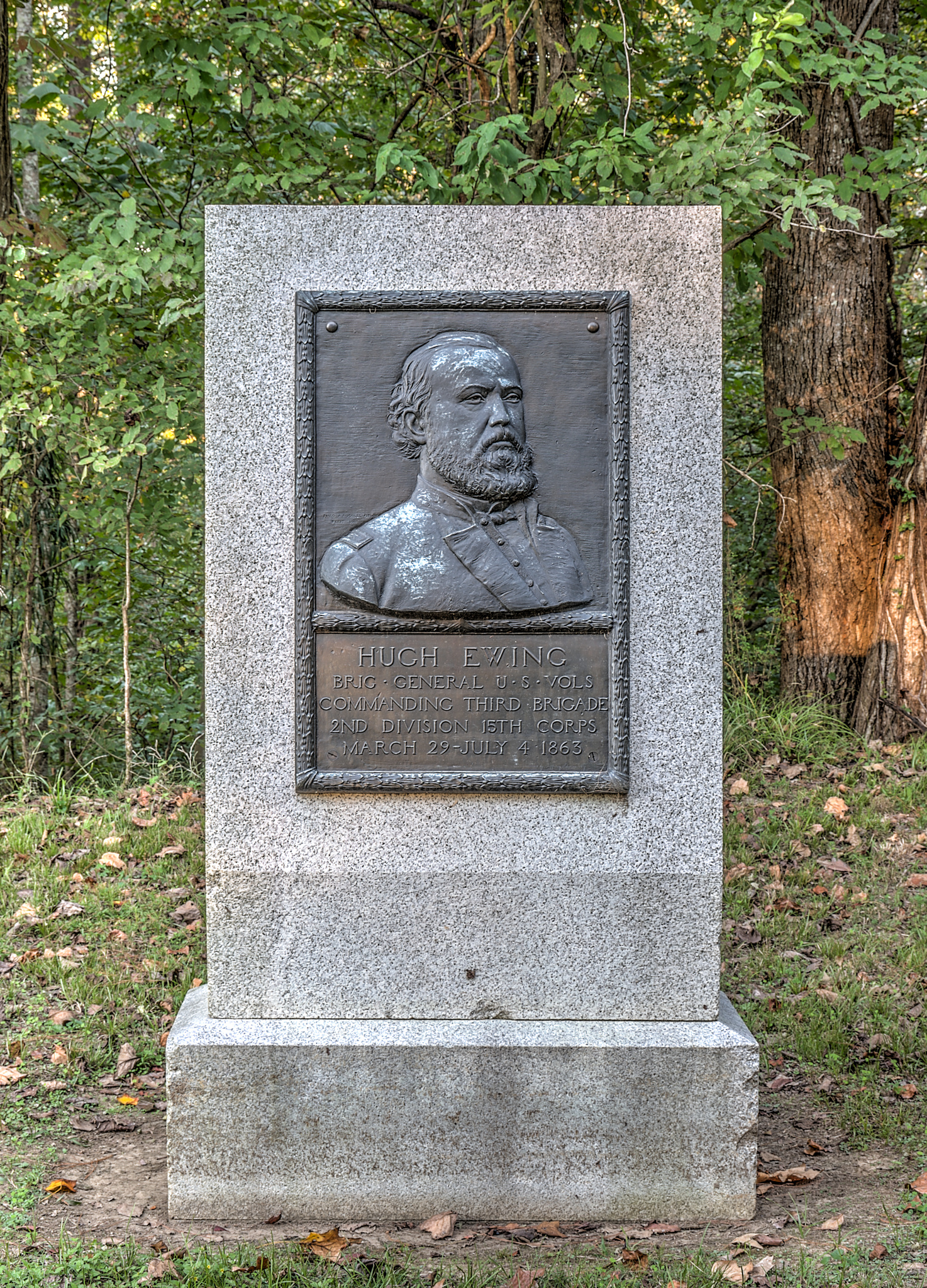

Hugh Boyle Ewing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hugh Boyle Ewing (October 31, 1826 – June 30, 1905) was a diplomat, author, attorney, and

In April 1861,

In April 1861,

/ref> After Antietam, Ewing was placed on sick leave because of chronic

Photos of General Ewing at generalsandbrevts.comEwing Family History Pages

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ewing, Hugh Boyle 1826 births 1905 deaths People from Lancaster, Ohio American historical novelists American autobiographers Novelists from Ohio People of Ohio in the American Civil War Union Army generals Ambassadors of the United States to the Netherlands 19th-century American diplomats American male novelists 19th-century American novelists 19th-century American male writers American male non-fiction writers Ewing family (politics and military)

Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

general during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. He was a member of the prestigious Ewing family, son of Thomas Ewing

Thomas Ewing Sr. (December 28, 1789October 26, 1871) was a National Republican and Whig politician from Ohio. He served in the U.S. Senate as well as serving as the secretary of the treasury and the first secretary of the interior. He is also ...

, the eldest brother of Thomas Ewing, Jr. and Charles Ewing, and the foster brother and brother-in-law of William T. Sherman

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

. General Ewing was an ambitious, literate, and erudite officer who held a strong sense of responsibility for the men under his command. He combined his West Point experience with the Civil War system of officer election.

Ewing's wartime service was characterized by several incidents which would have a unique impact on history. In 1861, his political connections helped save the reputation of his brother-in-law, William T. Sherman, who went on to become one of the north's most successful generals. Ewing himself went on to become Sherman's most trusted subordinate. His campaigning eventually led to the near-banishment of Lorenzo Thomas

Lorenzo Thomas (October 26, 1804 – March 2, 1875) was a career United States Army officer who was Adjutant General of the Army at the beginning of the American Civil War. After the war, he was appointed temporary Secretary of War by U.S. ...

, a high-ranking regular army

A regular army is the official army of a state or country (the official armed forces), contrasting with irregulars, irregular forces, such as volunteer irregular militias, private armies, mercenary, mercenaries, etc. A regular army usually has the ...

officer who had intrigued against Sherman. He was present at the Battle of Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union G ...

, where his brigade saved the flank of the Union Army late in the day. During the Vicksburg campaign

The Vicksburg campaign was a series of maneuvers and battles in the Western Theater of the American Civil War directed against Vicksburg, Mississippi, a fortress city that dominated the last Confederate-controlled section of the Mississippi Riv ...

, Ewing accidentally came across personal correspondence from Confederate President

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and was the commander-in-chief of the Confederate Army and the Confe ...

Jefferson F. Davis to former President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. He was a northern Democrat who believed that the abolitionist movement was a fundamental threat to the nation's unity ...

which eventually ruined the reputation of the latter. Ewing was also present in Kentucky during Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

Stephen G. Burbridge's "reign of terror", where he worked to oppose Burbridge's harsh policies against civilians, but was hampered by debilitating rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including art ...

. He ended the war with an independent command, a sign he held the confidence of his superiors, acting in concert with Sherman to trap Confederate Gen.

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; Hebrew language, Hebrew: בְּרֵאשִׁית ''Bəreʾšīt'', "In hebeginning") is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its i ...

Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia secede ...

in North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

.

After the war, Ewing spent time as Ambassador to the Netherlands and became a noted author. He died in 1905 on his family farm.

Early life and career

Hugh Ewing was born inLancaster, Ohio

Lancaster ( ) is a city in Fairfield County, Ohio, in the south-central part of the state. As of the 2020 census, the city population was 40,552. The city is near the Hocking River, about southeast of Columbus and southwest of Zanesville. It is ...

. He was educated at the United States Military Academy at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a fort, since it sits on strategic high groun ...

, but was forced to resign on the eve of graduation after failing an engineering exam, which was a major embarrassment to his family. While a member of the cadet corps, he was close friends with future Union generals John Buford Jr., Nathaniel C. McLean, and John C. Tidball. His father appointed Philip Sheridan

General of the Army Philip Henry Sheridan (March 6, 1831 – August 5, 1888) was a career United States Army officer and a Union general in the American Civil War. His career was noted for his rapid rise to major general and his close as ...

to the open seat.

During the gold rush

A gold rush or gold fever is a discovery of gold—sometimes accompanied by other precious metals and rare-earth minerals—that brings an onrush of miners seeking their fortune. Major gold rushes took place in the 19th century in Australia, New Z ...

in 1849, Ewing went to California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

, where he joined an expedition ordered by his father, then Secretary of the Interior Secretary of the Interior may refer to:

* Secretary of the Interior (Mexico)

* Interior Secretary of Pakistan

* Secretary of the Interior and Local Government (Philippines)

* United States Secretary of the Interior

See also

*Interior ministry ...

, to rescue immigrants who were trapped in the Sierra by heavy snows. He returned in 1852 with dispatches for the government.

He then completed his course in law and settled in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. He practiced law there from 1854 to 1856, when he moved with his young brother, Thomas Jr., and brothers-in-law William T. Sherman and Hampden B. Denman to Leavenworth, Kansas

Leavenworth () is the county seat and largest city of Leavenworth County, Kansas, United States and is part of the Kansas City metropolitan area. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 37,351. It is located on the west bank of t ...

, and began speculating in lands, roads, and government housing. They quickly established one of the leading law firms of Leavenworth, as well as a financially powerful land agency.

In 1858, Ewing married Henrietta Young, daughter of George W. Young, a large planter of the District of Columbia

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, whose family was prominent in the settlement and history of Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

. He soon afterward took charge of his father's salt works in Ohio.

Civil War

In April 1861,

In April 1861, Governor

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political ...

William Dennison appointed Ewing as the brigade-inspector of Ohio volunteers. He served under Rosecrans and McClellan in western Virginia

Western Virginia is a geographic region in Virginia comprising the Shenandoah Valley and Southwest Virginia. Generally, areas in Virginia located west of, or (in many cases) within, the piedmont region are considered part of western Virginia.

T ...

. Ewing became colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

of the 30th Ohio Volunteer Infantry in August 1861.

In November 1861, when his brother-in-law William T. Sherman was relieved of his command in disgrace, Ewing aided his younger sister Ellen Ewing Sherman

Eleanor Boyle Ewing Sherman (October 4, 1824 – November 28, 1888) was the wife of General William Tecumseh Sherman, a leading Union general in the American Civil War. She was also a prominent figure of the times in her own right.

Early yea ...

in making the rounds of Washington D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, Na ...

, denying sensationalist media claims that Sherman was insane, and personally lobbying the President for Sherman's reinstatement. Ewing and his sister argued that Sherman's requests for men and material in Kentucky had been denied in Washington, and that the charges of insanity had been part of a conspiracy orchestrated by Adjutant General Lorenzo Thomas

Lorenzo Thomas (October 26, 1804 – March 2, 1875) was a career United States Army officer who was Adjutant General of the Army at the beginning of the American Civil War. After the war, he was appointed temporary Secretary of War by U.S. ...

. Eventually the political influence of the Ewing family persevered, and with the assistance of Henry Halleck

Henry Wager Halleck (January 16, 1815 – January 9, 1872) was a senior United States Army officer, scholar, and lawyer. A noted expert in military studies, he was known by a nickname that became derogatory: "Old Brains". He was an important par ...

, Sherman was returned to command.Heidler, Jeanne, Heidler, David, & Coles, David. ''Encyclopedia of the American Civil War: A Political, Social, and Military History''. Santa Barbara, California, ABC-CLIO: 2000. President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

praised Sherman's "talent & conduct" publicly to a large group of important officers, and later banished Thomas to a meaningless post on recruiting duty in the Trans-Mississippi Theater.

Under McClellan, Ewing commanded a regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, service and/or a specialisation.

In Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of front-line soldiers, recruited or conscripted ...

and then a brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute a division.

Br ...

in the Kanawha Division

The Kanawha Division was a Union Army division which could trace its origins back to a brigade originally commanded by Jacob D. Cox. This division served in western Virginia and Maryland and was at times led by such famous personalities as George ...

in the IX Corps 9 Corps, 9th Corps, Ninth Corps, or IX Corps may refer to:

France

* 9th Army Corps (France)

* IX Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French Army during the Napoleonic Wars

Germany

* IX Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial Germ ...

. In the Battle of South Mountain

The Battle of South Mountain—known in several early Southern accounts as the Battle of Boonsboro Gap—was fought on September 14, 1862, as part of the Maryland campaign of the American Civil War. Three pitched battles were fought for posses ...

, he led the assault which drove the enemy from the summit; and at midnight of that day, he received an order placing him in command of the brigade of Colonel Eliakim P. Scammon, who was in temporary command of the Kanawha division after its commander Major General Jacob D. Cox

Jacob Dolson Cox, Jr. (October 27, 1828August 4, 1900), was a statesman, lawyer, Union Army general during the American Civil War, Republican politician from Ohio, Liberal Republican Party founder, educator, author, and recognized microbiologist ...

had been elevated to command of the IX Corps, replacing the fallen Major General Jesse Lee Reno

Jesse Lee Reno (April 20, 1823 – September 14, 1862) was a career United States Army officer who served in the Mexican–American War, in the Utah War, on the western frontier and as a Union General during the American Civil War from West Virg ...

who was killed earlier that day. At Antietam

The Battle of Antietam (), or Battle of Sharpsburg particularly in the Southern United States, was a battle of the American Civil War fought on September 17, 1862, between Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia and Union ...

his brigade was placed upon the extreme left of the army, where, according to the report of the commander of the left wing, General Ambrose Burnside, "by a brilliant change of front he saved the left from being completely driven in."Report of. Maj. Gen. Ambrose E. Burnside, U. S. Army, Commanding Right Wing, Army of the Potomac, Of Operations September 7-19./ref> After Antietam, Ewing was placed on sick leave because of chronic

dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, and was promoted to Brigadier General on November 29, 1862. He transferred West and served throughout the campaign before Vicksburg, leading the assaults made by General Sherman; and upon its fall was placed in command of a division

Division or divider may refer to:

Mathematics

*Division (mathematics), the inverse of multiplication

*Division algorithm, a method for computing the result of mathematical division

Military

*Division (military), a formation typically consisting ...

in the XVI Corps. At Chattanooga

Chattanooga ( ) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Tennessee, United States. Located along the Tennessee River bordering Georgia, it also extends into Marion County on its western end. With a population of 181,099 in 2020, ...

, he was given command of the 4th Division of the XV Corps 15th Corps, Fifteenth Corps, or XV Corps may refer to:

*XV Corps (British India)

* XV Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Army prior to and during World War I

* 15th Army Corps (Russian Empire), a unit in World War I

*XV Royal Bav ...

, which formed the advance of Sherman's army and carried Missionary Ridge.Sword, p. 157 Prior to the Battle of Chattanooga, Ewing's command led a diversionary raid that resulted in the destruction of the Empire State Iron Works in Dade County, Georgia

Dade County is a county in the U.S. state of Georgia. It occupies the northwest corner of Georgia, and the county's own northwest corner is the westernmost point in the state. As of the 2020 census, the population is 16,251. The county seat and ...

, which was being refurbished to increase the South's manufacturing capability. Sherman considered Ewing his most reliable division commander.

In the aftermath of Vicksburg, Ewing's command wrecked Confederate President Jefferson Davis's Fleetwood Plantation, and Ewing turned over Davis' personal correspondence to his brother-in-law, Sherman. However, Ewing also sent copies of the letters to a few people he had known in Ohio, which, after the documents were published, permanently sullied the reputation of former President Franklin Pierce of New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

. Their release coincided with that of Pierce's book, ''Our Old Home''. As early as 1860, Pierce had written to Davis about "the madness of northern abolitionism", and other letters uncovered stated that he would "never justify, sustain, or in any way or to any extent uphold this cruel, heartless, aimless unnecessary war", and that "the true purpose of the war was to wipe out the states and destroy property."

In October 1863, Ewing was placed in command of the occupation forces in Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border ...

. He was unfortunate enough to serve during Maj. Gen. Stephen Gano Burbridge's "reign of terror," where martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

was declared several times. On August 11, 1864, Burbridge ordered soldiers from the 26th Kentucky to select four men to be taken from prison in Louisville to Eminence, Kentucky

Eminence is a home rule class city in Henry County, Kentucky, in the United States. The population was 2,498 at the 2010 census, up from 2,231 at the 2000 census. Eminence is the largest city in Henry County. Eminence is home to the loudspeake ...

, to be shot for unknown outrages, and on August 20, several suspected Confederate guerrillas were also to be taken from Louisville and executed. General Ewing declared their innocence and sought a pardon from Burbridge, but he refused to give the pardon and the men were shot.

In his autobiography, Ewing describes an incident in October 1862 with Colonel Augustus Moor, who had struck a member of Ewing's regiment with his sword when the enlisted soldier had fallen out of a march. Ewing immediately confronted Moor. In his own words:

Colonel Moor quickly apologized. While General Ewing respected the discipline of the German regiment, he preferred a different atmosphere in his own command, better suited to Americans. He was capable of recognizing the military tradition of other units while accommodating the unique needs of his own. General Ewing was ordered to North Carolina in 1865, and was planning an expedition up the Roanoke river to co-operate with the Army of the James

The Army of the James was a Union Army that was composed of units from the Department of Virginia and North Carolina and served along the James River (Virginia), James River during the final operations of the American Civil War in Virginia.

Histor ...

, when Lee surrendered.Brown vol. III, p. 24

In 1864, Ewing suffered an attack of rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including art ...

, and received treatment several times thereafter, often being confined to his chair. He was likely prostrated with illness as Commander of Louisville during Burbridge's madness in Kentucky. He was made a brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

on March 13, 1865. After leaving the Army, he experienced painful attacks for the rest of his life, often bedridden for periods of up to forty days.

Postbellum career

PresidentAndrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

appointed Ewing as U.S. Minister to Holland

Holland is a geographical regionG. Geerts & H. Heestermans, 1981, ''Groot Woordenboek der Nederlandse Taal. Deel I'', Van Dale Lexicografie, Utrecht, p 1105 and former province on the western coast of the Netherlands. From the 10th to the 16th c ...

, where he served from 1866 to 1870. This appointment may have drawn the ire of the Radical Republicans

The Radical Republicans (later also known as " Stalwarts") were a faction within the Republican Party, originating from the party's founding in 1854, some 6 years before the Civil War, until the Compromise of 1877, which effectively ended Reco ...

, for Speaker of the House

The speaker of a deliberative assembly, especially a legislative body, is its presiding officer, or the chair. The title was first used in 1377 in England.

Usage

The title was first recorded in 1377 to describe the role of Thomas de Hungerf ...

James G. Blaine urged President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

that Ewing be recalled and replaced with his brother, Charles Ewing. Blaine told the President that Hugh was 'acting badly'. Blaine himself was disingenuous, having represented to prominent politicians in Ohio including Senator John Sherman

John Sherman (May 10, 1823October 22, 1900) was an American politician from Ohio throughout the Civil War and into the late nineteenth century. A member of the Republican Party, he served in both houses of the U.S. Congress. He also served as ...

that he was doing everything possible to nominate his close personal friend, former Ohio General Roeliff Brinkerhoff, for the post. Nonetheless, Blaine's request to recall General Ewing was never acted upon, possibly due to the influence of his sister, whose husband General Sherman was a very close friend to President Grant. Ewing was related to Blaine through Blaine's mother Maria Louise Gillespie Blaine.

Upon his eventual return to the United States, Ewing retired to a farm near Lancaster, Ohio, where he died of old age.

He was the author of: ''The Black List; A Tale of Early California'' (1887); ''A Castle in the Air'' (1887); ''The Gold Plague'', and other works.

See also

*List of American Civil War generals (Union)

Union generals

__NOTOC__

The following lists show the names, substantive ranks, and brevet ranks (if applicable) of all general officers who served in the United States Army during the Civil War, in addition to a small selection of lower-ranke ...

*Louisville in the American Civil War

Louisville in the American Civil War was a major stronghold of Union forces, which kept Kentucky firmly in the Union. It was the center of planning, supplies, recruiting and transportation for numerous campaigns, especially in the Western Theate ...

Notes

References

* Allen, Felicity. ''Jefferson Davis, Unconquerable Heart.'' St. Louis, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. 1999. . * Beach, Damian. ''Civil War Battles, Skirmishes, and Events in Kentucky.'' Louisville, Kentucky: Different Drummer Books. 1995. * Brinkerhoff, Roliff. ''Recollections of a Lifetime.'' Whitefish, Montana: Kessinger Publishing Company. 2007. . * The Diary of John Beatty, ''Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly'', Vol. 59 * Brown, J.H. ''The Cyclopaedia of American Biography: Comprising the Men and Women of the United States.'' New York City, New York: Kessinger Publishing, 2006. . * Burton, William L. ''Melting Pot Soldiers: The Union's Ethnic Regiments.'' New York City, New York: Fordham University Press. 1998. * Crist, Lynda Lasswel. ''A Bibliographical Note: Jefferson Davis's Personal Library: All Lost, Some Found.'' Journal of Mississippi History 45 (1983): 186–93. * Ewing, H.B. ''Autobiography of a Tramp.'' Columbus, Ohio Historical Society * Felt, Thomas E., ''Hugh Boyle Ewing Papers''. Museum Echoes, XXXIII (1960), 78–79. * Longacre, Edward. ''General John Buford: A Military Biography''. New York City, New York: Da Capo Press, 2003. . * Rossman, Kenneth R. ''Historical Essays in Honor of Kenneth R. Rossman.'' Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan. 1980. * Sears, Stephen W., Neely, Mark E., Fellman, Michael, and Simon, John Y., ed. by Boritt, Gabor S. ''Lincoln's Generals.'' Oxford University Press. 1994. . * Smith, Ronald D., ''Thomas Ewing Jr., Frontier Lawyer and Civil War General''. Columbia:University of Missouri Press, 2008, . * Sword, Wiley. ''Mountains Touched With Fire: Chattanooga Besieged, 1863.'' New York City, New York: St. Martin's Press. 1997. . * ''The Twentieth Century Biographical Dictionary of Notable Americans'' Vols. I-X (4). Boston, MA: The Biographical Society, 1904. * Warner, Ezra J. ''Generals in Blue: Lives of the Union Commanders''. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: LSU Press. 1964. . * Welsh, Jack D. ''Medical Histories of Union Generals.'' Columbus, Ohio: Kent State University Press. 1996. .External links

Photos of General Ewing at generalsandbrevts.com

{{DEFAULTSORT:Ewing, Hugh Boyle 1826 births 1905 deaths People from Lancaster, Ohio American historical novelists American autobiographers Novelists from Ohio People of Ohio in the American Civil War Union Army generals Ambassadors of the United States to the Netherlands 19th-century American diplomats American male novelists 19th-century American novelists 19th-century American male writers American male non-fiction writers Ewing family (politics and military)