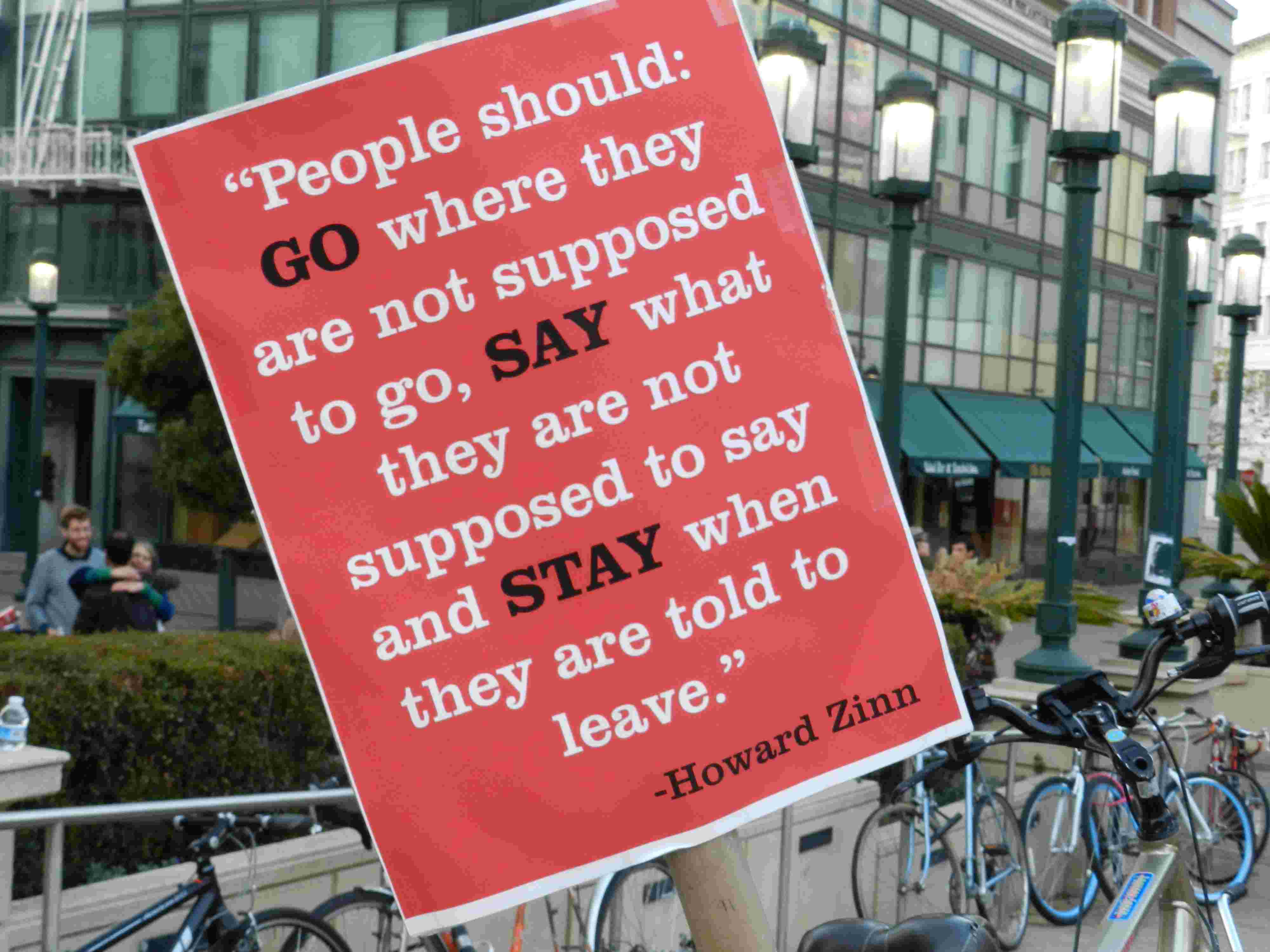

Howard Zinn on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

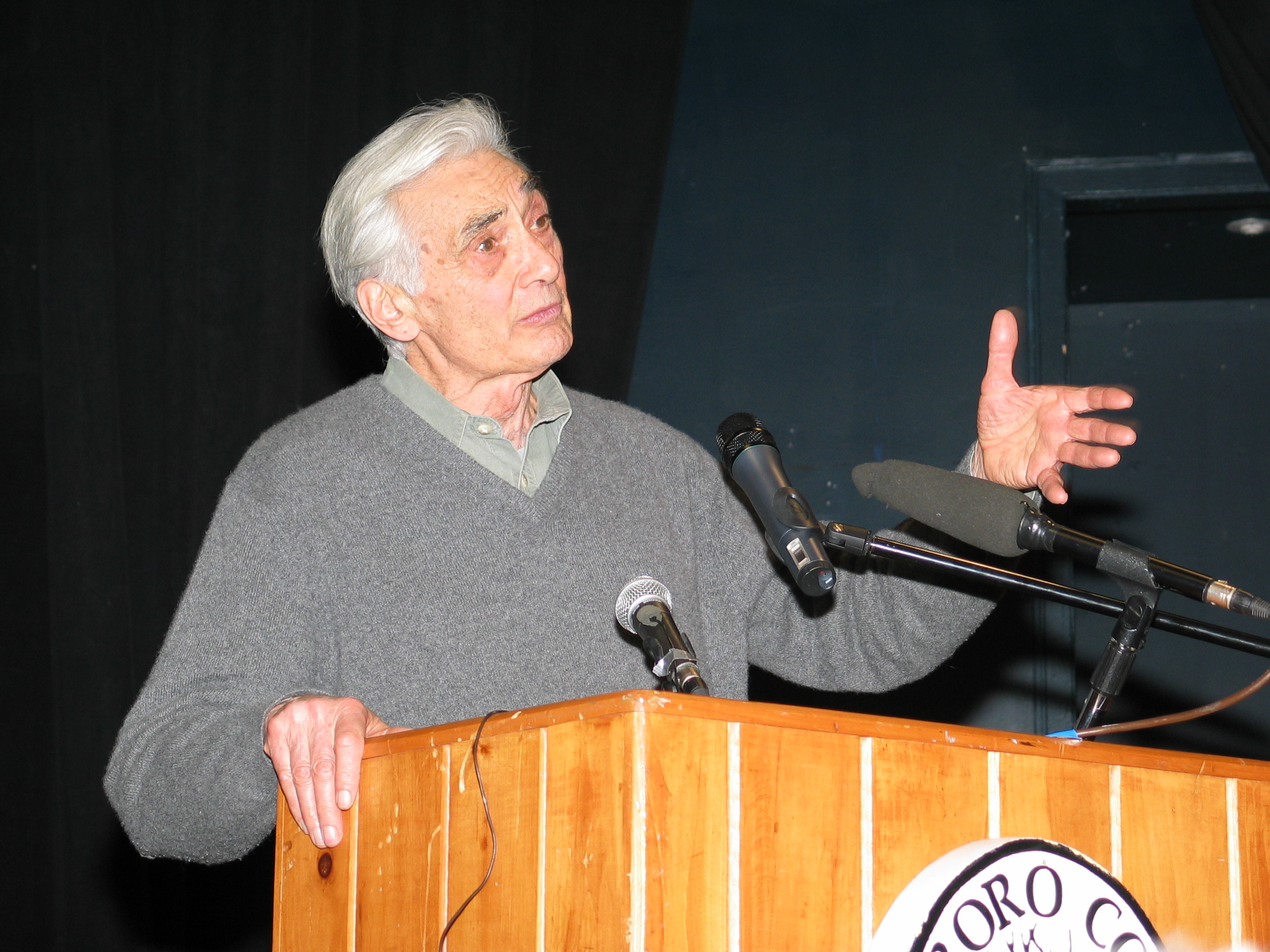

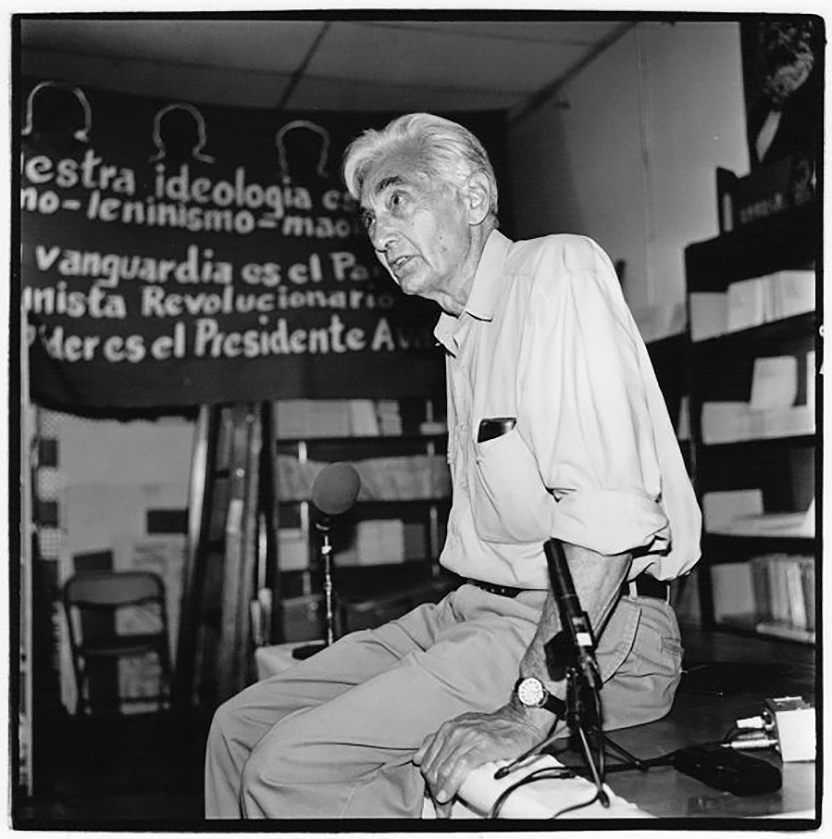

Howard Zinn (August 24, 1922January 27, 2010) was an American

Zinn opposed the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq and wrote several books about it. In an interview with ''

Zinn opposed the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq and wrote several books about it. In an interview with ''

On July 30, 2010, a

On July 30, 2010, a

Zinn married Roslyn Shechter in 1944. They remained married until her death in 2008. They had a daughter, Myla, and a son,

Zinn married Roslyn Shechter in 1944. They remained married until her death in 2008. They had a daughter, Myla, and a son,

(pamphlet, 1995)

. *''The Zinn Reader: Writings on Disobedience and Democracy'' (1997) ; 2nd edition (2009) . *''The Cold War & the University: Toward an Intellectual History of the Postwar Years'' (

historian

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the stu ...

, playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

, philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

thinker and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

veteran

A veteran () is a person who has significant experience (and is usually adept and esteemed) and expertise in a particular occupation or field. A military veteran is a person who is no longer serving in a military.

A military veteran that has ...

. He was chair of the history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

and social sciences

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of soci ...

department at Spelman College

Spelman College is a private, historically black, women's liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. It is part of the Atlanta University Center academic consortium in Atlanta. Founded in 1881 as the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, Spelman re ...

, and a political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

professor at Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with its original campu ...

. Zinn wrote over 20 books, including his best-selling and influential '' A People's History of the United States'' in 1980. In 2007, he published a version of it for younger readers, ''A Young People's History of the United States''.

Zinn described himself as "something of an anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

, something of a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. Maybe a democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within a ...

." He wrote extensively about the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

, the anti-war movement

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to ...

and labor history of the United States

The labor history of the United States describes the history of organized labor, US labor law, and more general history of working people, in the United States. Beginning in the 1930s, unions became important allies of the Democratic Party.

T ...

. His memoir, ''You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train'' (Beacon Press, 2002), was also the title of a 2004 documentary about Zinn's life and work. Zinn died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

in 2010, at age 87.

Early life

Zinn was born to aJew

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""Th ...

ish immigrant family in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

, New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, on August 24, 1922. His father, Eddie Zinn, born in Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

, immigrated to the US with his brother Samuel before the outbreak of World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. His mother, Jenny (Rabinowitz) Zinn, emigrated from the Eastern Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part of ...

n city of Irkutsk

Irkutsk ( ; rus, Иркутск, p=ɪrˈkutsk; Buryat language, Buryat and mn, Эрхүү, ''Erhüü'', ) is the largest city and administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. With a population of 617,473 as of the 2010 Census, Irkutsk is ...

. His parents first became acquainted as workers at the same factory. His father worked as a ditch digger and window cleaner during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

. Eddie and Jenny ran a neighborhood candy store for a brief time, barely getting by. For many years, his father was in the waiters' union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and worked as a waiter for weddings and bar mitzvahs.

Both parents were factory workers with limited education when they met and married, and there were no books or magazines in the series of apartments where they raised their children. Zinn's parents introduced him to literature by sending 10 cents plus a coupon to ''The New York Post

The ''New York Post'' (''NY Post'') is a conservative daily tabloid newspaper published in New York City. The ''Post'' also operates NYPost.com, the celebrity gossip site PageSix.com, and the entertainment site Decider.com.

It was established ...

'' for each of the 20 volumes of Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

' collected works. As a young man, Zinn made the acquaintance of several young Communists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

from his Brooklyn neighborhood. They invited him to a political rally

A political demonstration is an action by a mass group or collection of groups of people in favor of a political or other cause or people partaking in a protest against a cause of concern; it often consists of walking in a mass march formati ...

being held in Times Square

Times Square is a major commercial intersection, tourist destination, entertainment hub, and neighborhood in Midtown Manhattan, New York City. It is formed by the junction of Broadway, Seventh Avenue, and 42nd Street. Together with adjacent ...

. Despite it being a peaceful rally, mounted police charged the marchers. Zinn was hit and knocked unconscious. This would have a profound effect on his political and social outlook.

Howard Zinn studied creative writing

Creative writing is any writing that goes outside the bounds of normal professional, journalistic, academic, or technical forms of literature, typically identified by an emphasis on narrative craft, character development, and the use of literary ...

at Thomas Jefferson High School in a special program established by principal and poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writte ...

Elias Lieberman.

Zinn initially opposed entry into World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, influenced by his friends, by the results of the Nye Committee

The Nye Committee, officially known as the Special Committee on Investigation of the Munitions Industry, was a United States Senate committee (April 12, 1934 – February 24, 1936), chaired by U.S. Senator Gerald Nye (R-ND). The committee investig ...

, and by his ongoing reading. However, these feelings shifted as he learned more about fascism and its rise in Europe. The book '' Sawdust Caesar'' had a particularly large impact through its depiction of Mussolini. Thus, after graduating from high school in 1940, Zinn took the Civil Service exam and became an apprentice shipfitter

A shipfitter is a marine occupational classification used both by naval activities and among ship builders; however, the term applies mostly to certain workers at commercial and naval shipyards during the construction or repair phase of a ship.

T ...

in the New York Navy Yard

The Brooklyn Navy Yard (originally known as the New York Navy Yard) is a shipyard and industrial complex located in northwest Brooklyn in New York City, New York (state), New York. The Navy Yard is located on the East River in Wallabout Bay, a ...

at the age of 18. Concerns about low wages and hazardous working conditions compelled Zinn and several other apprentices to form the Apprentice Association. At the time, apprentices were excluded from trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and Employee ben ...

and thus had little bargaining power, to which the Apprentice Association was their answer. The head organizers of the association, which included Zinn himself, would meet once a week outside of work to discuss strategy and read books that at the time were considered radical. Zinn was the Activities Director for the group. His time in this group would tremendously influence his political views and created for him an appreciation for unions.

World War II

Eager to fightfascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

, Zinn joined the United States Army Air Corps during World War II and became an officer. He was assigned as a bombardier in the 490th Bombardment Group

The 490th Bombardment Group is a former United States Army Air Forces unit. The group was activated in October 1943 . After training in the United States, it deployed to the European Theater of Operations and participated in the strategic bo ...

, bombing targets in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, and Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia a ...

. As bombardier, Zinn dropped napalm

Napalm is an incendiary mixture of a gelling agent and a volatile petrochemical (usually gasoline (petrol) or diesel fuel). The name is a portmanteau of two of the constituents of the original thickening and gelling agents: coprecipitated al ...

bombs in April 1945 on Royan

Royan (; in the Saintongeais dialect; oc, Roian) is a commune and town in the south-west of France, in the department of Charente-Maritime in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region. Its inhabitants are known as ''Royannais'' and ''Royannaises''. Capi ...

, a seaside resort in western France. The anti-war

An anti-war movement (also ''antiwar'') is a social movement, usually in opposition to a particular nation's decision to start or carry on an armed conflict, unconditional of a maybe-existing just cause. The term anti-war can also refer to pa ...

stance Zinn developed later was informed, in part, by his experiences.

On a post-doctoral research mission nine years later, Zinn visited the resort near Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( , ; Gascon oc, Bordèu ; eu, Bordele; it, Bordò; es, Burdeos) is a port city on the river Garonne in the Gironde department, Southwestern France. It is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the prefectur ...

where he interviewed residents, reviewed municipal documents, and read wartime newspaper clippings at the local library. In 1966, Zinn returned to Royan after which he gave his fullest account of that research in his book, ''The Politics of History''. On the ground, Zinn learned that the aerial bombing attacks in which he participated had killed more than a thousand French civilians as well as some German soldiers hiding near Royan to await the war's end, events that are described "in all accounts" he found as ''"une tragique erreur"'' that leveled a small but ancient city and "its population that was, at least officially, friend, not foe." In ''The Politics of History'', Zinn described how the bombing was ordered—three weeks before the war in Europe ended—by military officials who were, in part, motivated more by the desire for their own career advancement than in legitimate military objectives. He quotes the official history of the U.S. Army Air Forces' brief reference to the Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Force ...

attack on Royan and also, in the same chapter, to the bombing of Plzeň

Plzeň (; German and English: Pilsen, in German ) is a city in the Czech Republic. About west of Prague in western Bohemia, it is the Statutory city (Czech Republic), fourth most populous city in the Czech Republic with about 169,000 inhabita ...

in what was then Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. The official history stated that the Skoda

Škoda means ''pity'' in the Czech and Slovak languages. It may also refer to:

Czech brands and enterprises

* Škoda Auto, automobile and previously bicycle manufacturer in Mladá Boleslav

** Škoda Motorsport, the division of Škoda Auto respons ...

works in Pilsen "received 500 well-placed tons", and that "because of a warning sent out ahead of time the workers were able to escape, except for five persons. "The Americans received a rapturous welcome when they liberated the city.

Zinn wrote:I recalled flying on that mission, too, as deputy lead bombardier, and that we did not aim specifically at the 'Skoda works' (which I would have noted, because it was the one target in Czechoslovakia I had read about) but dropped our bombs, without much precision, on the city of Pilsen. Two Czech citizens who lived in Pilsen at the time told me, recently, that several hundred people were killed in that raid (that is, Czechs)—not five.Zinn said his experience as a wartime bombardier, combined with his research into the reasons for, and effects of the bombing of Royan and Pilsen, sensitized him to the ethical dilemmas faced by G.I.s during wartime. Zinn questioned the justifications for military operations that inflicted massive civilian casualties during the

Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

bombing of cities such as Dresden

Dresden (, ; Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; wen, label=Upper Sorbian, Drježdźany) is the capital city of the German state of Saxony and its second most populous city, after Leipzig. It is the 12th most populous city of Germany, the fourth larg ...

, Royan, Tokyo

Tokyo (; ja, 東京, , ), officially the Tokyo Metropolis ( ja, 東京都, label=none, ), is the capital and largest city of Japan. Formerly known as Edo, its metropolitan area () is the most populous in the world, with an estimated 37.468 ...

, and Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

in World War II, Hanoi

Hanoi or Ha Noi ( or ; vi, Hà Nội ) is the capital and second-largest city of Vietnam. It covers an area of . It consists of 12 urban districts, one district-leveled town and 17 rural districts. Located within the Red River Delta, Hanoi is ...

during the War in Vietnam

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, and Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

during the war in Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

and the civilian casualties during bombings in Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,; prs, امارت اسلامی افغانستان is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. Referred to as the Heart of Asia, it is bordere ...

during the war there. In his pamphlet, ''Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence'' written in 1995, he laid out the case against targeting civilians with aerial bombing.

Six years later, he wrote:Recall that in the midst of theGulf War The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ..., the U.S. military bombed anair raid shelter Air raid shelters are structures for the protection of non-combatants as well as combatants against enemy attacks from the air. They are similar to bunkers in many regards, although they are not designed to defend against ground attack (but many ..., killing 400 to 500 men, women, and children who were huddled to escape bombs. The claim was that it was a military target, housing a communications center, but reporters going through the ruins immediately afterward said there was no sign of anything like that. I suggest that the history of bombing—and no one has bombed more than this nation—is a history of endless atrocities, all calmly explained by deceptive and deadly language like "accident", "military target", and "collateral damage Collateral damage is any death, injury, or other damage inflicted that is an incidental result of an activity. Originally coined by military operations, it is now also used in non-military contexts. Since the development of precision guided ...".

Education

After World War II, Zinn attendedNew York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then-Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, the ...

on the GI Bill

The Servicemen's Readjustment Act of 1944, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, was a law that provided a range of benefits for some of the returning World War II veterans (commonly referred to as G.I.s). The original G.I. Bill expired in 1956, bu ...

, graduating with a B.A. in 1951. At Columbia University

Columbia University (also known as Columbia, and officially as Columbia University in the City of New York) is a private research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Church in Manhatt ...

, he earned an M.A. (1952) and a Ph.D. in history with a minor in political science (1958). His master's thesis examined the Colorado coal strikes of 1914. His doctoral dissertation

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: ...

''Fiorello LaGuardia in Congress'' was a study of Fiorello LaGuardia

Fiorello Henry LaGuardia (; born Fiorello Enrico LaGuardia, ; December 11, 1882September 20, 1947) was an American attorney and politician who represented New York in the House of Representatives and served as the 99th Mayor of New York City from ...

's congressional career, and it depicted "the conscience of the twenties" as LaGuardia fought for public power, the right to strike, and the redistribution of wealth by taxation. "His specific legislative program," Zinn wrote, "was an astonishingly accurate preview of the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

." It was published by the Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

Press for the American Historical Association

The American Historical Association (AHA) is the oldest professional association of historians in the United States and the largest such organization in the world. Founded in 1884, the AHA works to protect academic freedom, develop professional s ...

. ''Fiorello LaGuardia in Congress'' was nominated for the American Historical Association's Beveridge Prize as the best English-language book on American history.

His professors at Columbia included Harry Carman

Harry Carman (January 22, 1884 – December 26, 1964) was an American historian. Having attended Syracuse University followed by studies at Columbia, he became a professor at the latter, and served from 1943 to 1950 he served as its dean. During h ...

, Henry Steele Commager

Henry Steele Commager (1902–1998) was an American historian. As one of the most active and prolific liberal intellectuals of his time, with 40 books and 700 essays and reviews, he helped define modern liberalism in the United States.

In the 19 ...

, and David Donald. But it was Columbia historian Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter (August 6, 1916October 24, 1970) was an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century.

Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier historic ...

's ''The American Political Tradition

''The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It'' is a 1948 book by Richard Hofstadter, an account of the ideology of previous Presidents of the United States and other political figures.

Contents

Hofstadter's introduction argues that ...

'' that made the most lasting impression. Zinn regularly included it in his lists of recommended readings, and, after Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II ( ; born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who served as the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, Obama was the first African-American president of the U ...

was elected President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, Zinn wrote, "If Richard Hofstadter were adding to his book ''The American Political Tradition'', in which he found both 'conservative' and 'liberal' Presidents, both Democrats and Republicans, maintaining for dear life the two critical characteristics of the American system, nationalism and capitalism, Obama would fit the pattern."

In 1960–61, Zinn was a post-doctoral

A postdoctoral fellow, postdoctoral researcher, or simply postdoc, is a person professionally conducting research after the completion of their doctoral studies (typically a Doctor of Philosophy, PhD). The ultimate goal of a postdoctoral rese ...

fellow in East Asian Studies

East Asian studies is a distinct multidisciplinary field of scholarly enquiry and education that promotes a broad humanistic understanding of East Asia past and present. The field includes the study of the region's culture, written language, histo ...

at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

.

Career

Academic career

Zinn was professor of history atSpelman College

Spelman College is a private, historically black, women's liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. It is part of the Atlanta University Center academic consortium in Atlanta. Founded in 1881 as the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, Spelman re ...

in Atlanta from 1956 to 1963, and visiting professor at both the University of Paris

, image_name = Coat of arms of the University of Paris.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of Arms

, latin_name = Universitas magistrorum et scholarium Parisiensis

, motto = ''Hic et ubique terrarum'' (Latin)

, mottoeng = Here and a ...

and University of Bologna

The University of Bologna ( it, Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna, UNIBO) is a public research university in Bologna, Italy. Founded in 1088 by an organised guild of students (''studiorum''), it is the oldest university in continuo ...

. At the end of the academic year in 1963, Zinn was fired from Spelman for insubordination. His dismissal came from Dr. Albert Manley, the first African-American president of that college, who felt Zinn was radicalizing Spelman students.

In 1964, he accepted a position at Boston University

Boston University (BU) is a private research university in Boston, Massachusetts. The university is nonsectarian, but has a historical affiliation with the United Methodist Church. It was founded in 1839 by Methodists with its original campu ...

(BU), after writing two books and participating in the Civil Rights Movement in the South. His classes in civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

were among the most popular at the university with as many as 400 students subscribing each semester to the non-required class. A professor of political science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thought, political behavior, and associated constitutions and la ...

, he taught at BU for 24 years and retired in 1988 at age 66.

"He had a deep sense of fairness and justice for the underdog. But he always kept his sense of humor. He was a happy warrior," said Caryl Rivers, journalism

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation (profes ...

professor at BU. Rivers and Zinn were among a group of faculty members who in 1979 defended the right of the school's clerical workers to strike and were threatened with dismissal after refusing to cross a picket line.

Zinn came to believe that the point of view expressed in traditional history books was often limited. Biographer Martin Duberman

Martin Bauml Duberman (born August 6, 1930) is an American historian, biographer, playwright, and gay rights activist. Duberman is Professor of History Emeritus at Lehman College, Herbert Lehman College in the Bronx, New York City.

Early life

Du ...

noted that when he was asked directly if he was a Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

, Zinn replied, "Yes, I'm something of a Marxist." He especially was influenced by the liberating vision of the young Marx in overcoming alienation, and disliked what he perceived to be Marx's later dogmatism. In later life he moved more toward anarchism

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessa ...

.

He wrote a history text, '' A People's History of the United States'', to provide other perspectives on American history. The book depicts the struggles of Native Americans against European and U.S. conquest and expansion, slaves against slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, unionists and other workers against capitalists, women against patriarchy

Patriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and privilege are primarily held by men. It is used, both as a technical anthropological term for families or clans controlled by the father or eldest male or group of males a ...

, and African-Americans for civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and political life of ...

. The book was a finalist for the National Book Award

The National Book Awards are a set of annual U.S. literary awards. At the final National Book Awards Ceremony every November, the National Book Foundation presents the National Book Awards and two lifetime achievement awards to authors.

The Nat ...

in 1981.

In the years since the first publication of ''A People's History'' in 1980, it has been used as an alternative to standard textbooks in many college history courses, and it is one of the most widely known examples of critical pedagogy

Critical pedagogy is a philosophy of education and social movement that developed and applied concepts from critical theory and related traditions to the field of education and the study of culture.

It insists that issues of social justice and de ...

. The ''New York Times Book Review

''The New York Times Book Review'' (''NYTBR'') is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times'' in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely rea ...

'' stated in 2006 that the book "routinely sells more than 100,000 copies a year."

In 2004, Zinn published ''Voices of a People's History of the United States

''Voices of a People's History of the United States'' () is an anthology edited by Howard Zinn and Anthony Arnove. First released in 2004 by Seven Stories Press, ''Voices'' is the primary source companion to Zinn's ''A People's History of the Unit ...

'' with Anthony Arnove. ''Voices'' is a sourcebook of speeches, articles, essays, poetry and song lyrics by the people themselves whose stories are told in ''A People's History.''

In 2008, the Zinn Education Project was launched to support educators using ''A People's History of the United States'' as a source for middle and high school history. The project was started when William Holtzman, a former student of Zinn who wanted to bring Zinn's lessons to students around the country, provided the financial backing to allow two other organizations, Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change to coordinate the project. The project hosts a website with hundreds of free downloadable lesson plans to complement ''A People's History of the United States''.

''The People Speak

The People Speak is an online community of young people who want to get involved in global issues. The community engages people of all ages and backgrounds in thoughtful discussions about the value of international cooperation for the United State ...

'', released in 2010, is a documentary movie based on ''A People's History of the United States'' and inspired by the lives of ordinary people who fought back against oppressive conditions over the course of the history of the United States. The film, narrated by Zinn, includes performances by Matt Damon

Matthew Paige Damon (; born October 8, 1970) is an American actor, film producer, and screenwriter. Ranked among ''Forbes'' most bankable stars, the films in which he has appeared have collectively earned over $3.88 billion at the North Americ ...

, Morgan Freeman

Morgan Freeman (born June 1, 1937) is an American actor, director, and narrator. He is known for his distinctive deep voice and various roles in a wide variety of film genres. Throughout his career spanning over five decades, he has received ...

, Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Often regarded as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture during a career sp ...

, Bruce Springsteen

Bruce Frederick Joseph Springsteen (born September 23, 1949) is an American singer and songwriter. He has released 21 studio albums, most of which feature his backing band, the E Street Band. Originally from the Jersey Shore, he is an originat ...

, Eddie Vedder

Eddie Jerome Vedder (born Edward Louis Severson III; December 23, 1964) is an American singer, musician, and songwriter best known as the lead vocalist and one of four guitarists of the rock band Pearl Jam. He also appeared as a guest vocalist i ...

, Viggo Mortensen

Viggo Peter Mortensen Jr. R (; born October 20, 1958) is an American actor, writer, director, producer, musician, and multimedia artist. Born and raised in the State of New York to a Danish father and American mother, he also lived in Argentin ...

, Josh Brolin

Joshua James Brolin (; born February 12, 1968) is an American actor. He has appeared in films such as ''The Goonies'' (1985), ''Mimic'' (1997), ''Hollow Man'' (2000), ''Grindhouse'' (2007), ''No Country for Old Men'' (2007), '' American Gangste ...

, Danny Glover

Danny Lebern Glover (; born July 22, 1946) is an American actor, film director, and political activist. He is widely known for his lead role as Roger Murtaugh in the ''Lethal Weapon'' film series. He also had leading roles in his films include ...

, Marisa Tomei

Marisa Tomei ( , ; born December 4, 1964) is an American actress. She came to prominence as a cast member on '' The Cosby Show'' spin-off '' A Different World'' in 1987. After having minor roles in a few films, she came to international attentio ...

, Don Cheadle

Donald Frank Cheadle Jr. (; born November 29, 1964) is an American actor. He is the recipient of multiple accolades, including two Grammy Awards, a Tony Award, two Golden Globe Awards and two Screen Actors Guild Awards. He has also earned ...

, and Sandra Oh

Sandra Miju Oh (born July 20, 1971) is a Canadian–American actress. She is best known for her starring roles as Rita Wu on the HBO comedy '' Arliss'' (1996–2002), Dr. Cristina Yang on the ABC medical drama series ''Grey's Anatomy'' (2005 ...

.

Civil rights movement

From 1956 through 1963, Zinn chaired the Department of History and Social Sciences atSpelman College

Spelman College is a private, historically black, women's liberal arts college in Atlanta, Georgia. It is part of the Atlanta University Center academic consortium in Atlanta. Founded in 1881 as the Atlanta Baptist Female Seminary, Spelman re ...

. He participated in the Civil Rights Movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

and lobbied with historian August Meier "to end the practice of the Southern Historical Association

The Southern Historical Association is a professional academic organization of historians focusing on the history of the Southern United States. It was organized on November 2, 1934. Its objectives are the promotion of interest and research in Sou ...

of holding meetings at segregated hotels."

While at Spelman, Zinn served as an adviser to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, often pronounced ) was the principal channel of student commitment in the United States to the civil rights movement during the 1960s. Emerging in 1960 from the student-led sit-ins at segrega ...

(SNCC) and wrote about sit-ins and other actions by SNCC for ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'' and ''Harper's''. In 1964, Beacon Press

Beacon Press is an American left-wing non-profit book publisher. Founded in 1854 by the American Unitarian Association, it is currently a department of the Unitarian Universalist Association. It is known for publishing authors such as James B ...

published his book '' SNCC: The New Abolitionists''.

In 1964 Zinn, with the SNCC, began developing an educational program so that the 200 volunteer SNCC civil rights workers in the South, many of whom were college dropouts, could continue with their civil rights work and at the same time be involved in an educational system. Up until then many of the volunteers had been dropping out of school so they could continue their work with SNCC. Other volunteers had not spent much time in college. The program had been endorsed by the SNCC in December 1963 and was envisioned by Zinn as having a curriculum that ranged from novels to books about "major currents" in 20th-century world history, such as fascism, communism, and anti-colonial movements. This occurred while Zinn was in Boston.

Zinn also attended an assortment of SNCC meetings in 1964, traveling back and forth from Boston. One of those trips was to Hattiesburg, Mississippi

Hattiesburg is a city in the U.S. state of Mississippi, located primarily in Forrest County, Mississippi, Forrest County (where it is the county seat and largest city) and extending west into Lamar County, Mississippi, Lamar County. The city popu ...

, in January 1964 to participate in a SNCC voter registration drive. The local newspaper, the ''Hattiesburg American'', described the SNCC volunteers in town for the voter registration drive as "outside agitators" and told local blacks "to ignore whatever goes on, and interfere in no way..." At a mass meeting held during the visit to Hattiesburg, Zinn and another SNCC representative, Ella Baker

Ella Josephine Baker (December 13, 1903 – December 13, 1986) was an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and t ...

, emphasized the risks that went along with their efforts, a subject probably in their minds since a well-known civil rights activist, Medgar Evers

Medgar Wiley Evers (; July 2, 1925June 12, 1963) was an American civil rights activist and the NAACP's first field secretary in Mississippi, who was murdered by Byron De La Beckwith. Evers, a decorated U.S. Army combat veteran who had served i ...

, had been murdered getting out of his car in the driveway of his home in Jackson, Mississippi, only six months earlier. Evers had been the state field secretary for the NAACP.

Zinn was also involved in what became known as Freedom Summer

Freedom Summer, also known as the Freedom Summer Project or the Mississippi Summer Project, was a volunteer campaign in the United States launched in June 1964 to attempt to register as many African-American voters as possible in Mississippi. ...

in Mississippi in the summer of 1964. Freedom Summer involved bringing 1,000 college students to Mississippi to work for the summer in various roles as civil rights activists. Part of the program involved organizing "Freedom Schools". Zinn's involvement included helping to develop the curriculum for the Freedom Schools. He was also concerned that bringing 1,000 college students to Mississippi to work as civil rights activists could lead to violence and killings. As a consequence, Zinn recommended approaching Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett

Ross Robert Barnett (January 22, 1898November 6, 1987) was the Governor of Mississippi from 1960 to 1964. He was a Southern Democrat who supported racial segregation.

Early life

Background and learning

Born in Standing Pine in Leake Count ...

and President Lyndon Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

to request protection for the young civil rights volunteers. Protection was not forthcoming. Planning for the summer went forward under the umbrella of the SNCC, the Congress of Racial Equality ("CORE") and the Council of Federated Organizations ("COFO").

On June 20, 1964, just as civil rights activists were beginning to arrive in Mississippi, CORE activists James Chaney

James Earl Chaney (May 30, 1943 – June 21, 1964) was one of three Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) civil rights workers killed in Philadelphia, Mississippi, by members of the Ku Klux Klan on June 21, 1964. The others were Andrew Goodman an ...

, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner were en route to investigate the burning of Mount Zion Methodist Church in Neshoba County when two carloads of KKK members led by deputy sheriff Cecil Price

Cecil Ray Price (April 15, 1938 – May 6, 2001) was accused of the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in 1964. At the time of the murders, he was 26 years old and a deputy sheriff in Neshoba County, Mississippi. He was a member of the Wh ...

abducted and murdered

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification or valid excuse, especially the unlawful killing of another human with malice aforethought. ("The killing of another person without justification or excuse, especially the c ...

them. Two months later, after their bodies were located, Zinn and other representatives of the SNCC attended a memorial service for the three at the ruins of Mount Zion Methodist Church.

Zinn collaborated with historian Staughton Lynd mentoring student activists, among them Alice Walker

Alice Malsenior Tallulah-Kate Walker (born February 9, 1944) is an American novelist, short story writer, poet, and social activist. In 1982, she became the first African-American woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, which she was aw ...

, who would later write ''The Color Purple

''The Color Purple'' is a 1982 epistolary novel by American author Alice Walker which won the 1983 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and the National Book Award for Fiction.

,'' and Marian Wright Edelman

Marian Wright Edelman (born June 6, 1939) is an American activist for civil rights and children's rights. She is the founder and president emerita of the Children's Defense Fund. She influenced leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Hillary ...

, founder and president of the Children's Defense Fund

The Children's Defense Fund (CDF) is an American 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Washington, D.C., that focuses on child advocacy and research. It was founded in 1973 by Marian Wright Edelman.

History

The CDF was founded in 1973, citi ...

. Edelman identified Zinn as a major influence in her life and, in the same journal article, tells of his accompanying students to a sit-in at the segregated white section of the Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

state legislature. Zinn also co-wrote a column in ''The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'' with fellow activist Eric Mann, "Left Field Stands".

Although Zinn was a tenured professor, he was dismissed in June 1963 after siding with students in the struggle against segregation. As Zinn described in ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

,'' though Spelman administrators prided themselves for turning out refined "young ladies", its students were likely to be found on the picket line, or in jail for participating in the greater effort to break down segregation in public places in Atlanta. Zinn's years at Spelman are recounted in his autobiography ''You Can't Be Neutral on a Moving Train: A Personal History of Our Times''. His seven years at Spelman College, Zinn said, "are probably the most interesting, exciting, most educational years for me. I learned more from my students than my students learned from me."

While living in Georgia, Zinn wrote that he observed 30 violations of the First

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

and Fourteenth amendments to the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven ar ...

in Albany, Georgia

Albany ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Georgia. Located on the Flint River, it is the seat of Dougherty County, and is the sole incorporated city in that county. Located in southwest Georgia, it is the principal city of the Albany, Georgia ...

, including the rights to freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recogni ...

, freedom of assembly

Freedom of peaceful assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ide ...

and equal protection

The Equal Protection Clause is part of the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The clause, which took effect in 1868, provides "''nor shall any State ... deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal ...

under the law. In an article on the civil rights movement in Albany, Zinn described the people who participated in the Freedom Rides

Freedom Riders were civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated Southern United States in 1961 and subsequent years to challenge the non-enforcement of the United States Supreme Court decisions '' Morgan v. Virginia ...

to end segregation, and the reluctance of President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

to enforce the law. Zinn said that the Justice Department

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

under Robert F. Kennedy

Robert Francis Kennedy (November 20, 1925June 6, 1968), also known by his initials RFK and by the nickname Bobby, was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 64th United States Attorney General from January 1961 to September 1964, ...

and the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

, headed by J. Edgar Hoover

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972) was an American law enforcement administrator who served as the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He was appointed director of the Bureau of Investigation � ...

, did little or nothing to stop the segregationists from brutalizing civil rights workers.

Zinn wrote about the struggle for civil rights, as both participant and historian. His second book, '' The Southern Mystique'', was published in 1964, the same year as his ''SNCC: The New Abolitionists'' in which he describes how the sit-ins against segregation were initiated by students and, in that sense, were independent of the efforts of the older, more established civil rights organizations.

In 2005, forty-one years after he was sacked from Spelman, Zinn returned to the college, where he was given an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters. He delivered the commencement address, titled "Against Discouragement", and said that "the lesson of that history is that you must not despair, that if you are right, and you persist, things will change. The government may try to deceive the people, and the newspapers and television may do the same, but the truth has a way of coming out. The truth has a power greater than a hundred lies."

Anti-war efforts

Vietnam

Zinn wrote one of the earliest books calling for the U.S. withdrawal from its war inVietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

. ''Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal'' was published by Beacon Press in 1967 based on his articles in ''Commonweal

Commonweal or common weal may refer to:

* Common good, what is shared and beneficial for members of a given community

* Common Weal, a Scottish think tank and advocacy group

* Commonweal (magazine), ''Commonweal'' (magazine), an American lay-Cath ...

'', ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

,'' and '' Ramparts''. In the opinion of Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

, ''The Logic of Withdrawal'' was Zinn's most important book:"He was the first person to say—loudly, publicly, very persuasively—that this simply has to stop; we should get out, period, no conditions; we have no right to be there; it's an act of aggression; pull out. It was so surprising at the time that there wasn't even a review of the book. In fact, he asked me if I would review it in ''Ramparts'' just so that people would know about the book."Zinn's diplomatic visit to Hanoi with Reverend

Daniel Berrigan

Daniel Joseph Berrigan (May 9, 1921 – April 30, 2016) was an American Jesuit priest, anti-war activist, Christian pacifist, playwright, poet, and author.

Berrigan's active protest against the Vietnam War earned him both scorn and admi ...

, during the Tet Offensive in January 1968, resulted in the return of three American airmen, the first American POWs released by the North Vietnamese since the U.S. bombing of that nation had begun. The event was widely reported in the news media and discussed in a variety of books including ''Who Spoke Up? American Protest Against the War in Vietnam 1963–1975'' by Nancy Zaroulis and Gerald Sullivan. Zinn and the Berrigan brothers, Dan and Philip

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

, remained friends and allies over the years.

Also in January 1968, he signed the "Writers and Editors War Tax Protest

Tax resistance, the practice of refusing to pay taxes that are considered unjust, has probably existed ever since rulers began imposing taxes on their subjects. It has been suggested that tax resistance played a significant role in the collapse of ...

" pledge, vowing to refuse tax payments in protest against the war.

In December 1969, radical historians tried unsuccessfully to persuade the American Historical Association

The American Historical Association (AHA) is the oldest professional association of historians in the United States and the largest such organization in the world. Founded in 1884, the AHA works to protect academic freedom, develop professional s ...

to pass an anti-Vietnam War resolution. "A debacle unfolded as Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

historian (and AHA president in 1968) John Fairbank literally wrestled the microphone from Zinn's hands."

Daniel Ellsberg

Daniel Ellsberg (born April 7, 1931) is an American political activist, and former United States military analyst. While employed by the RAND Corporation, Ellsberg precipitated a national political controversy in 1971 when he released the ''Pent ...

, a former RAND

The RAND Corporation (from the phrase "research and development") is an American nonprofit global policy think tank created in 1948 by Douglas Aircraft Company to offer research and analysis to the United States Armed Forces. It is financed ...

consultant who had secretly copied ''The Pentagon Papers

The ''Pentagon Papers'', officially titled ''Report of the Office of the Secretary of Defense Vietnam Task Force'', is a United States Department of Defense history of the United States' political and military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 ...

'', which described the history of the United States' military involvement in Southeast Asia, gave a copy to Howard and Roslyn Zinn. Along with Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

, Zinn edited and annotated the copy of ''The Pentagon Papers'' that Senator Mike Gravel

Maurice Robert "Mike" Gravel ( ; May 13, 1930 – June 26, 2021) was an American politician and writer who served as a United States Senator from Alaska from 1969 to 1981 as a member of the Democratic Party, and who later in life twice ran for ...

read into the Congressional Record and that was subsequently published by Beacon Press

Beacon Press is an American left-wing non-profit book publisher. Founded in 1854 by the American Unitarian Association, it is currently a department of the Unitarian Universalist Association. It is known for publishing authors such as James B ...

.

Announced on August 17 and published on October 10, 1971, this four-volume, relatively expensive set became the "Senator Gravel Edition", which studies from Cornell University

Cornell University is a private statutory land-grant research university based in Ithaca, New York. It is a member of the Ivy League. Founded in 1865 by Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White, Cornell was founded with the intention to teach an ...

and the Annenberg Center for Communication The Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership & Policy (CCLP) at the University of Southern California promotes interdisciplinary research in communications between the USC School of Cinematic Arts, Viterbi School of Engineering, and the separat ...

have labeled as the most complete edition of the Pentagon Papers to be published. The "Gravel Edition" was edited and annotated by Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn, and included an additional volume of analytical articles on the origins and progress of the war, also edited by Chomsky and Zinn.

Zinn testified as an expert witness at Ellsberg's criminal trial for theft, conspiracy, and espionage in connection with the publication of the ''Pentagon Papers'' by ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

''. Defense attorneys asked Zinn to explain to the jury the history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam from World War II through 1963. Zinn discussed that history for several hours, and later reflected on his time before the jury. I explained there was nothing in the papers of military significance that could be used to harm the defense of the United States, that the information in them was simply ''embarrassing'' to our government because what was revealed, in the government's own interoffice memos, was how it had lied to the American public. ... The secrets disclosed in the Pentagon Papers might embarrass politicians, might hurt the profits of corporations wanting tin, rubber, oil, in far-off places. But this was not the same as hurting the nation, the people.Most of the jurors later said that they voted for acquittal. However, the federal judge who presided over the case dismissed it on grounds it had been tainted by the

Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 to 1974. A member of the Republican Party, he previously served as a representative and senator from California and was ...

administration's burglary of the office of Ellsberg's psychiatrist.

Zinn's testimony on the motivation for government secrecy was confirmed in 1989 by Erwin Griswold

Erwin Nathaniel Griswold (; July 14, 1904 – November 19, 1994) was an American appellate attorney who argued many cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Griswold served as Solicitor General of the United States (1967–1973) under Presidents Lynd ...

, who as U.S. solicitor general during the Nixon administration sued ''The New York Times'' in the Pentagon Papers case in 1971 to stop publication. Griswold persuaded three Supreme Court justices to vote to stop ''The New York Times'' from continuing to publish the Pentagon Papers, an order known as "prior restraint

Prior restraint (also referred to as prior censorship or pre-publication censorship) is censorship imposed, usually by a government or institution, on expression, that prohibits particular instances of expression. It is in contrast to censorship ...

" that has been held to be illegal under the First Amendment

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

to the U.S. Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. The papers were simultaneously published in ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', effectively nullifying the effect of the prior restraint order. In 1989, Griswold admitted there had been no national security damage resulting from publication. In a column in ''The Washington Post'', Griswold wrote: "It quickly becomes apparent to any person who has considerable experience with classified material that there is massive over-classification and that the principal concern of the classifiers is not with national security, but with governmental embarrassment of one sort or another."

Zinn supported the G.I. anti-war movement during the U.S. war in Vietnam. In the 2001 film '' Unfinished Symphony: Democracy and Dissent'', Zinn provides a historical context for the 1971 anti-war march by Vietnam Veterans against the War

Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW) is an American tax-exempt non-profit organization and corporation founded in 1967 to oppose the United States policy and participation in the Vietnam War. VVAW says it is a national veterans' organization ...

. The marchers traveled from Bunker Hill near Boston to Lexington, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, "which retraced Paul Revere

Paul Revere (; December 21, 1734 O.S. (January 1, 1735 N.S.)May 10, 1818) was an American silversmith, engraver, early industrialist, Sons of Liberty member, and Patriot and Founding Father. He is best known for his midnight ride to ale ...

's ride of 1775 and ended in the massive arrest of 410 veterans and civilians by the Lexington police." The film depicts "scenes from the 1971 Winter Soldier hearings, during which former G.I.s testified about "atrocities" they either participated in or said they had witnessed committed by U.S. forces in Vietnam. Zinn also took part in the 1971 May Day protests (with among others Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

and Daniel Ellsberg

Daniel Ellsberg (born April 7, 1931) is an American political activist, and former United States military analyst. While employed by the RAND Corporation, Ellsberg precipitated a national political controversy in 1971 when he released the ''Pent ...

).

In later years, Zinn was an adviser to the Disarm Education Fund.

Iraq

Zinn opposed the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq and wrote several books about it. In an interview with ''

Zinn opposed the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq and wrote several books about it. In an interview with ''The Brooklyn Rail

''The Brooklyn Rail'' is a publication and platform for the arts, culture, humanities, and politics. The ''Rail'' is based out of Brooklyn, New York. It features in-depth critical essays, fiction, poetry, as well as interviews with artists, criti ...

'' he said, We certainly should not be initiating a war, as it's not a clear and present danger to the United States, or in fact, to anyone around it. If it were, then the states around Iraq would be calling for a war on it. The Arab states around Iraq are opposed to the war, and if anyone's in danger from Iraq, they are. At the same time, the U.S. is violating the U.N. charter by initiating a war on Iraq. Bush made a big deal about the number of resolutions Iraq has violated—and it's true, Iraq has not abided by the resolutions of the Security Council. But it's not the first nation to violate Security Council resolutions. Israel has violated Security Council resolutions every year since 1967. Now, however, the U.S. is violating a fundamental principle of the U.N. Charter, which is that nations can't initiate a war—they can only do so after being attacked. And Iraq has not attacked us.He asserted that the U.S. would end Gulf War II when resistance within the military increased in the same way resistance within the military contributed to ending the U.S. war in Vietnam. Zinn compared the demand by a growing number of contemporary U.S. military families to end the war in Iraq to parallel demands "in the Confederacy in the Civil War, when the wives of soldiers rioted because their husbands were dying and the plantation owners were profiting from the sale of cotton, refusing to grow grains for civilians to eat." Zinn believed that U.S. President George W. Bush and followers of

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi

Abu Musab al-Zarqawi ( ar, أَبُو مُصْعَبٍ ٱلزَّرْقَاوِيُّ, ', ''Father of Musab, from Zarqa''; ; October 30, 1966 – June 7, 2006), born Ahmad Fadeel al-Nazal al-Khalayleh (, '), was a Jordanian jihadist who ran a t ...

, the former leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq

Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI; ar, القاعدة في العراق, al-Qā'idah fī al-ʿIrāq) or Al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia ( ar, القاعدة في بلاد الرافدين, al-Qā'idah fī Bilād ar-Rāfidayn), officially known as ''Tanzim Qaidat a ...

, who was personally responsible for beheadings and numerous attacks designed to cause civil war in Iraq, should be considered moral equivalents.

Jean-Christophe Agnew, Professor of History and American Studies at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, told the ''Yale Daily News

The ''Yale Daily News'' is an independent student newspaper published by Yale University students in New Haven, Connecticut since January 28, 1878. It is the oldest college daily newspaper in the United States. The ''Yale Daily News'' has consis ...

'' in May 2007 that Zinn's historical work is "highly influential and widely used". He observed that it is not unusual for prominent professors such as Zinn to weigh in on current events, citing a resolution opposing the war in Iraq that was recently ratified by the American Historical Association

The American Historical Association (AHA) is the oldest professional association of historians in the United States and the largest such organization in the world. Founded in 1884, the AHA works to protect academic freedom, develop professional s ...

. Agnew added: "In these moments of crisis, when the country is split—so historians are split."

Socialism

Zinn described himself as "something of ananarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

, something of a socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

. Maybe a democratic socialist

Democratic socialism is a left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self-management within a ...

." He suggested looking at socialism in its full historical context as a popular, positive idea that got a bad name from its association with Soviet Communism

The ideology of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) was Bolshevist Marxism–Leninism, an ideology of a centralised command economy with a vanguardist one-party state to realise the dictatorship of the proletariat. The Soviet Un ...

. In Madison, Wisconsin

Madison is the county seat of Dane County and the capital city of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. As of the 2020 census the population was 269,840, making it the second-largest city in Wisconsin by population, after Milwaukee, and the 80th-lar ...

, in 2009, Zinn said:

FBI files

On July 30, 2010, a

On July 30, 2010, a Freedom of Information Act Freedom of Information Act may refer to the following legislations in different jurisdictions which mandate the national government to disclose certain data to the general public upon request:

* Freedom of Information Act 1982, the Australian act

* ...

(FOIA) request resulted in the Federal Bureau of Investigation

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic intelligence and security service of the United States and its principal federal law enforcement agency. Operating under the jurisdiction of the United States Department of Justice, ...

(FBI) releasing a file with 423 pages of information on Howard Zinn's life and activities. During the height of McCarthyism

McCarthyism is the practice of making false or unfounded accusations of subversion and treason, especially when related to anarchism, communism and socialism, and especially when done in a public and attention-grabbing manner.

The term origin ...

in 1949, the FBI first opened a domestic security investigation on Zinn (FBI File # 100-360217), based on Zinn's activities in what the agency considered to be communist front groups

A front organization is any entity set up by and controlled by another organization, such as intelligence agencies, organized crime groups, terrorist organizations, secret societies, banned organizations, religious or political groups, advocacy gr ...

, such as the American Labor Party

The American Labor Party (ALP) was a political party in the United States established in 1936 that was active almost exclusively in the state of New York. The organization was founded by labor leaders and former members of the Socialist Party of ...

, and informant reports that Zinn was an active member of the Communist Party of the United States

The Communist Party USA, officially the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), is a communist party in the United States which was established in 1919 after a split in the Socialist Party of America following the Russian Revo ...

(CPUSA). Zinn denied ever being a member and said that he had participated in the activities of various organizations which might be considered Communist fronts, but that his participation was motivated by his belief that in this country people had the right to believe, think, and act according to their own ideals. According to journalist Chris Hedges, Zinn "steadfastly refused to cooperate in the anti-communist witchhunts in the 1950s."

Later in the 1960s, as a result of Zinn's campaigning against the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

and his communication with Martin Luther King Jr.

Martin Luther King Jr. (born Michael King Jr.; January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American Baptist minister and activist, one of the most prominent leaders in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968 ...

, the FBI designated him a high security risk to the country by adding him to the Security Index, a list of American citizens who could be summarily arrested if a state of emergency