Horatio Herbert Kitchener on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Horatio Herbert Kitchener, 1st Earl Kitchener, (; 24 June 1850 – 5 June 1916) was a senior

Kitchener was born in Ballylongford near

Kitchener was born in Ballylongford near

During the

During the

In late 1902 Kitchener was appointed Commander-in-Chief, India, and arrived there to take up the position in November, in time to be in charge during the January 1903

In late 1902 Kitchener was appointed Commander-in-Chief, India, and arrived there to take up the position in November, in time to be in charge during the January 1903  Later events proved Curzon was right in opposing Kitchener's attempts to concentrate all military decision-making power in his own office. Although the offices of Commander-in-Chief and Military Member were now held by a single individual, senior officers could approach only the Commander-in-Chief directly. In order to deal with the Military Member, a request had to be made through the Army Secretary, who reported to the Indian Government and had right of access to the Viceroy. There were even instances when the two separate bureaucracies produced different answers to a problem, with the Commander-in-Chief disagreeing with himself as Military Member. This became known as "the canonisation of duality". Kitchener's successor,

Later events proved Curzon was right in opposing Kitchener's attempts to concentrate all military decision-making power in his own office. Although the offices of Commander-in-Chief and Military Member were now held by a single individual, senior officers could approach only the Commander-in-Chief directly. In order to deal with the Military Member, a request had to be made through the Army Secretary, who reported to the Indian Government and had right of access to the Viceroy. There were even instances when the two separate bureaucracies produced different answers to a problem, with the Commander-in-Chief disagreeing with himself as Military Member. This became known as "the canonisation of duality". Kitchener's successor,  Kitchener was promoted to the highest Army rank,

Kitchener was promoted to the highest Army rank,

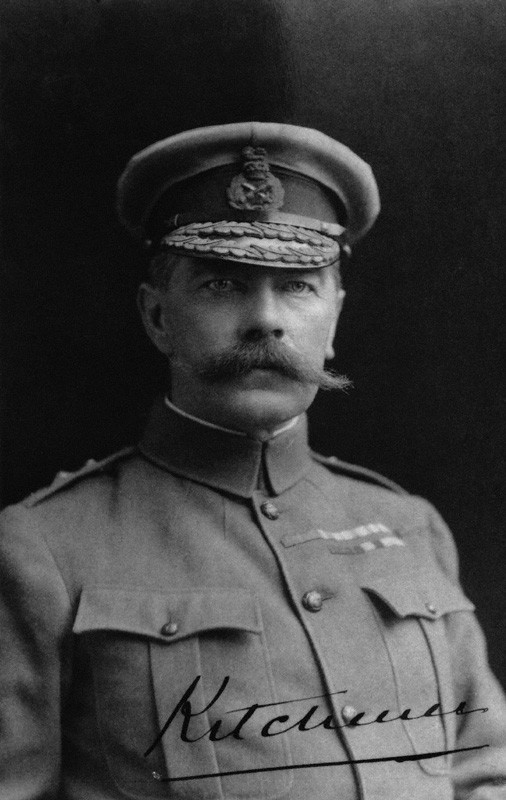

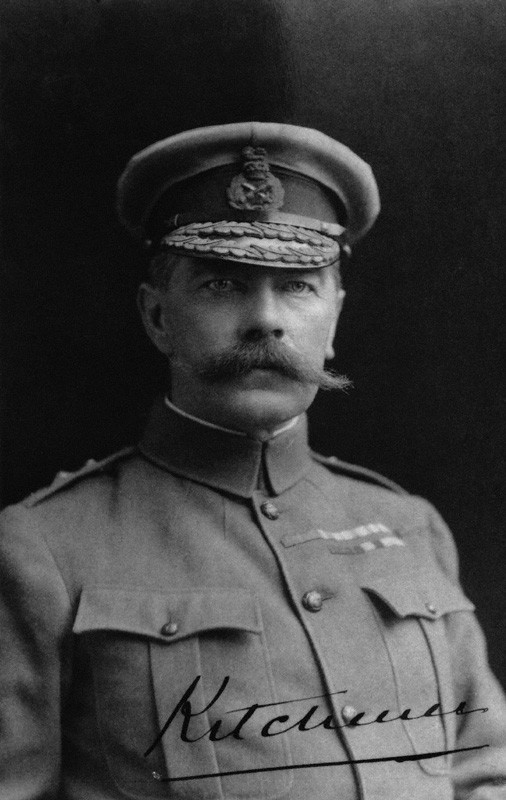

Against cabinet opinion, Kitchener correctly predicted a long war that would last at least three years, require huge new armies to defeat Germany, and cause huge casualties before the end would come. Kitchener stated that the conflict would plumb the depths of manpower "to the last million". A massive recruitment campaign began, which soon featured a distinctive poster of Kitchener, taken from a magazine front cover. It may have encouraged large numbers of volunteers, and has proven to be one of the most enduring images of the war, having been copied and parodied many times since. Kitchener built up the "New Armies" as separate units because he distrusted the Territorials from what he had seen with the French Army in 1870. This may have been a mistaken judgement, as the British reservists of 1914 tended to be much younger and fitter than their French equivalents a generation earlier.

Cabinet Secretary

Against cabinet opinion, Kitchener correctly predicted a long war that would last at least three years, require huge new armies to defeat Germany, and cause huge casualties before the end would come. Kitchener stated that the conflict would plumb the depths of manpower "to the last million". A massive recruitment campaign began, which soon featured a distinctive poster of Kitchener, taken from a magazine front cover. It may have encouraged large numbers of volunteers, and has proven to be one of the most enduring images of the war, having been copied and parodied many times since. Kitchener built up the "New Armies" as separate units because he distrusted the Territorials from what he had seen with the French Army in 1870. This may have been a mistaken judgement, as the British reservists of 1914 tended to be much younger and fitter than their French equivalents a generation earlier.

Cabinet Secretary

Kitchener sailed from

Kitchener sailed from

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer and colonial administrator. Kitchener came to prominence for his imperial campaigns, his scorched earth

A scorched-earth policy is a military strategy that aims to destroy anything that might be useful to the enemy. Any assets that could be used by the enemy may be targeted, which usually includes obvious weapons, transport vehicles, communi ...

policy against the Boers

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled this area ...

, his expansion of Lord Roberts' concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

and his central role in the early part of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

Kitchener was credited in 1898 for having won the Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert Kitchener and a Sudanese army of the M ...

and securing control of the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

for which he was made

Made or MADE may refer to:

Entertainment Film

* ''Made'' (1972 film), United Kingdom

* ''Made'' (2001 film), United States Music

* ''Made'' (Big Bang album), 2016

* ''Made'' (Hawk Nelson album), 2013

* ''Made'' (Scarface album), 2007

*'' M.A.D.E. ...

Baron Kitchener

Earl Kitchener, of Khartoum and of Broome Park, Broome in the County of Kent, was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1914 for the famous soldier Field marshal (United Kingdom), Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener, 1st Ea ...

of Khartoum. As Chief of Staff (1900–1902) in the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

he played a key role in Roberts' conquest of the Boer Republics, then succeeded Roberts as commander-in-chief – by which time Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

forces had taken to guerrilla fighting and British forces imprisoned Boer civilians in concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

. His term as Commander-in-Chief (1902–1909) of the Army in India saw him quarrel with another eminent proconsul

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

In the Roman Republic, military command, or ' ...

, the Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

Lord Curzon

George Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston, (11 January 1859 – 20 March 1925), styled Lord Curzon of Kedleston between 1898 and 1911 and then Earl Curzon of Kedleston between 1911 and 1921, was a British Conservative statesman ...

, who eventually resigned. Kitchener then returned to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

as British Agent and Consul-General (''de facto'' administrator).

In 1914, at the start of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, Kitchener became Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

, a Cabinet Minister. One of the few to foresee a long war, lasting for at least three years, and also having the authority to act effectively on that perception, he organised the largest volunteer army

The Volunteer Army (russian: Добровольческая армия, translit=Dobrovolcheskaya armiya, abbreviated to russian: Добрармия, translit=Dobrarmiya) was a White Army active in South Russia during the Russian Civil War from ...

that Britain had seen, and oversaw a significant expansion of materiel production to fight on the Western Front. Despite having warned of the difficulty of provisioning for a long war, he was blamed for the shortage of shells in the spring of 1915 – one of the events leading to the formation of a coalition government – and stripped of his control over munitions and strategy.

On 5 June 1916, Kitchener was making his way to Russia on to attend negotiations with Tsar Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Polan ...

when in bad weather the ship struck a German mine west of Orkney

Orkney (; sco, Orkney; on, Orkneyjar; nrn, Orknøjar), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago in the Northern Isles of Scotland, situated off the north coast of the island of Great Britain. Orkney is 10 miles (16 km) north ...

, Scotland, and sank. Kitchener was among 737 who died.

Early life

Kitchener was born in Ballylongford near

Kitchener was born in Ballylongford near Listowel

Listowel ( ; , IPA: �lʲɪsˠˈt̪ˠuəhəlʲ is a heritage market town in County Kerry, Ireland. It is on the River Feale, from the county town, Tralee. The town of Listowel had a population of 4,820 according to the Central Statistics Of ...

, County Kerry

County Kerry ( gle, Contae Chiarraí) is a county in Ireland. It is located in the South-West Region and forms part of the province of Munster. It is named after the Ciarraige who lived in part of the present county. The population of the co ...

, in Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, son of army officer Henry Horatio Kitchener (1805–1894) and Frances Anne Chevallier (died 1864; daughter of John Chevallier, a clergyman, of Aspall Hall, and his third wife, Elizabeth, ''née'' Cole).

Both sides of Kitchener's family were from Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include Lowes ...

, and could trace their descent to the reign of William III; his mother's family was of French Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

descent. His father had only recently sold his commission and bought land in Ireland, under the Encumbered Estates Act of 1849 designed to encourage investment into Ireland after the Irish Famine

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a h ...

. They then moved to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, where the young Kitchener was educated at Montreux

Montreux (, , ; frp, Montrolx) is a Swiss municipality and town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the Alps. It belongs to the district of Riviera-Pays-d'Enhaut in the canton of Vaud in Switzerland, and has a population of approximat ...

, then at the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich

The Royal Military Academy (RMA) at Woolwich, in south-east London, was a British Army military academy for the training of commissioned officers of the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers. It later also trained officers of the Royal Corps of Sig ...

. Pro-French and eager to see action, he joined a French field ambulance unit in the Franco-Prussian War. His father took him back to Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

after he caught pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

while ascending in a balloon to see the French Army of the Loire in action.

Commissioned into the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

on 4 January 1871, his service in France had violated British neutrality, and he was reprimanded by the Duke of Cambridge

Duke of Cambridge, one of several current royal dukedoms in the United Kingdom , is a hereditary title of specific rank of nobility in the British royal family. The title (named after the city of Cambridge in England) is heritable by male de ...

, the commander-in-chief. He served in Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

and Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

as a surveyor, learned Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

, and prepared detailed topographical maps of the areas. His brother, Lt. Gen. Sir Walter Kitchener, had also entered the army, and was Governor of Bermuda from 1908 to 1912.

Survey of western Palestine

In 1874, aged 24, Kitchener was assigned by thePalestine Exploration Fund

The Palestine Exploration Fund is a British society based in London. It was founded in 1865, shortly after the completion of the Ordnance Survey of Jerusalem, and is the oldest known organization in the world created specifically for the study ...

to a mapping-survey of the Holy Land

The Holy Land; Arabic: or is an area roughly located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Eastern Bank of the Jordan River, traditionally synonymous both with the biblical Land of Israel and with the region of Palestine. The term "Holy ...

, replacing Charles Tyrwhitt-Drake

Charles Frederick Tyrwhitt-Drake (2 January 1846 – 23 June 1874) was an explorer, naturalist, archaeologist, and linguist. He died during the PEF Survey of Palestine.

He was the youngest son of Colonel W. Tyrwhitt Drake.

He worked with the Pal ...

, who had died of malaria. By then an officer in the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is a corps of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces and is heade ...

, Kitchener joined fellow officer Claude R. Conder

Claude Reignier Conder (29 December 1848, Cheltenham – 16 February 1910, Cheltenham) was an English soldier, explorer and antiquarian. He was a great-great-grandson of Louis-François Roubiliac and grandson of editor and author Josiah Conder ...

; between 1874 and 1877 they surveyed Palestine, returning to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

only briefly in 1875 after an attack by locals at Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

, in Galilee

Galilee (; he, הַגָּלִיל, hagGālīl; ar, الجليل, al-jalīl) is a region located in northern Israel and southern Lebanon. Galilee traditionally refers to the mountainous part, divided into Upper Galilee (, ; , ) and Lower Galil ...

.

Conder and Kitchener's expedition became known as the Survey of Western Palestine

The PEF Survey of Palestine was a series of surveys carried out by the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF) between 1872 and 1877 for the Survey of Western Palestine and in 1880 for the Survey of Eastern Palestine. The survey was carried out after the ...

because it was largely confined to the area west of the Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan ( ar, نَهْر الْأُرْدُنّ, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn'', he, נְהַר הַיַּרְדֵּן, ''Nəhar hayYardēn''; syc, ܢܗܪܐ ܕܝܘܪܕܢܢ ''Nahrāʾ Yurdnan''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Shariea ...

. The survey collected data on the topography and toponymy of the area, as well as local flora and fauna.

The results of the survey were published in an eight-volume series, with Kitchener's contribution in the first three tomes (Conder and Kitchener 1881–1885). This survey has had a lasting effect on the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

for several reasons:

* It serves as the basis for the grid system used in the modern maps of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

;

* The data compiled by Conder and Kitchener are still consulted by archaeologists and geographers working in the southern Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

;

* The survey itself effectively delineated and defined the political borders of the southern Levant. For example, the modern border between Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

is established at the point in upper Galilee

The Upper Galilee ( he, הגליל העליון, ''HaGalil Ha'Elyon''; ar, الجليل الأعلى, ''Al Jaleel Al A'alaa'') is a geographical-political term in use since the end of the Second Temple period. It originally referred to a mounta ...

where Conder and Kitchener's survey stopped.

In 1878, having completed the survey of western Palestine, Kitchener was sent to Cyprus

Cyprus ; tr, Kıbrıs (), officially the Republic of Cyprus,, , lit: Republic of Cyprus is an island country located south of the Anatolian Peninsula in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Its continental position is disputed; while it is geo ...

to undertake a survey of that newly acquired British protectorate. He became vice-consul in Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The re ...

in 1879.

Egypt

On 4 January 1883 Kitchener was promoted tocaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

, given the Turkish rank binbasi (major), and dispatched to Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, where he took part in the reconstruction of the Egyptian Army.

Egypt had recently become a British puppet state, its army led by British officers, although still nominally under the sovereignty of the Khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Kh ...

(Egyptian viceroy) and his nominal overlord the (Ottoman) Sultan of Turkey. Kitchener became second-in-command of an Egyptian cavalry regiment in February 1883, and then took part in the failed expedition to relieve Charles George Gordon

Major-general (United Kingdom), Major-General Charles George Gordon Companion of the Order of the Bath, CB (28 January 1833 – 26 January 1885), also known as Chinese Gordon, Gordon Pasha, and Gordon of Khartoum, was a British Army officer and ...

in the Sudan

Sudan ( or ; ar, السودان, as-Sūdān, officially the Republic of the Sudan ( ar, جمهورية السودان, link=no, Jumhūriyyat as-Sūdān), is a country in Northeast Africa. It shares borders with the Central African Republic t ...

in late 1884.

Fluent in Arabic, Kitchener preferred the company of the Egyptians over the British, and the company of no-one over the Egyptians, writing in 1884 that: "I have become such a solitary bird that I often think I were happier alone". Kitchener spoke Arabic so well that he was able to effortlessly adopt the dialects of the different Bedouin

The Bedouin, Beduin, or Bedu (; , singular ) are nomadic Arab tribes who have historically inhabited the desert regions in the Arabian Peninsula, North Africa, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. The Bedouin originated in the Syrian Desert and A ...

tribes of Egypt and the Sudan.

Promoted to brevet

Brevet may refer to:

Military

* Brevet (military), higher rank that rewards merit or gallantry, but without higher pay

* Brevet d'état-major, a military distinction in France and Belgium awarded to officers passing military staff college

* Aircre ...

major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

on 8 October 1884 and to brevet lieutenant-colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

on 15 June 1885, he became the British member of the Zanzibar

Zanzibar (; ; ) is an insular semi-autonomous province which united with Tanganyika in 1964 to form the United Republic of Tanzania. It is an archipelago in the Indian Ocean, off the coast of the mainland, and consists of many small islands ...

boundary commission in July 1885. He became Governor of the Egyptian Provinces of Eastern Sudan and Red Sea Littoral (which in practice consisted of little more than the Port of Suakin

Suakin or Sawakin ( ar, سواكن, Sawákin, Beja: ''Oosook'') is a port city in northeastern Sudan, on the west coast of the Red Sea. It was formerly the region's chief port, but is now secondary to Port Sudan, about north.

Suakin used to b ...

) in September 1886, also Pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, gener ...

the same year, and led his forces in action against the followers of the Mahdi

''The Mahdi'' is a 1981 thriller novel by Philip Nicholson, writing as A. J. Quinnell. The book was published in 1981 by Macmillan Publishers, Macmillan in the UK then in January 1982 by William Morrow & Co in the US and deals with political po ...

at Handub in January 1888, when he was injured in the jaw.

Kitchener was promoted to brevet colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

on 11 April 1888 and to the substantive rank of major on 20 July 1889 and led the Egyptian cavalry at the Battle of Toski

The Battle of Toski (''Tushkah'') was part of the Mahdist War. It took place on August 3, 1889 in southern Egypt between the Anglo-Egyptian forces and the Mahdist forces of the Sudan.

Since 1882, the British had taken control of Egypt and found ...

in August 1889. At the beginning of 1890 he was appointed Inspector General of the Egyptian police 1888–92 before moving to the position of Adjutant-General of the Egyptian Army in December of the same year and Sirdar

The rank of Sirdar ( ar, سردار) – a variant of Sardar – was assigned to the British Commander-in-Chief of the British-controlled Egyptian Army in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Sirdar resided at the Sirdaria, a three-blo ...

(Commander-in-Chief) of the Egyptian Army with the local rank of brigadier in April 1892.

Kitchener was worried that, although his moustache was bleached white by the sun, his blond hair refused to turn grey, making it harder for Egyptians to take him seriously. His appearance added to his mystique: his long legs made him appear taller, whilst a cast in his eye made people feel he was looking right through them. Kitchener, at , towered over most of his contemporaries.

Sir Evelyn Baring

Evelyn Baring, 1st Earl of Cromer, (; 26 February 1841 – 29 January 1917) was a British statesman, diplomat and colonial administrator. He served as the British controller-general in Egypt during 1879, part of the international control whic ...

, the ''de facto'' British ruler of Egypt, thought Kitchener "the most able (soldier) I have come across in my time". In 1890, a War Office

The War Office was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, when its functions were transferred to the new Ministry of Defence (MoD). This article contains text from ...

evaluation of Kitchener concluded: "A good brigadier, very ambitious, not popular, but has of late greatly improved in tact and manner ... a fine gallant soldier and good linguist and very successful in dealing with Orientals" n the 19th century, Europeans called the Middle East the Orient

While in Egypt, Kitchener was initiated into Freemasonry

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

in 1883 in the Italian-speaking La Concordia Lodge No. 1226, which met in Cairo. In November 1899 he was appointed the first District Grand Master of the District Grand Lodge of Egypt and the Sudan, under the United Grand Lodge of England

The United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE) is the governing Masonic lodge for the majority of freemasons in England, Wales and the Commonwealth of Nations. Claiming descent from the Masonic grand lodge formed 24 June 1717 at the Goose & Gridiron T ...

.

Sudan and Khartoum

In 1896, the British Prime Minister,Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

, was concerned with keeping France out of the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

. A French expedition under the command of Jean-Baptiste Marchand

:''for others with similar names, see Jean Marchand

General Jean-Baptiste Marchand (22 November 1863 – 14 January 1934) was a French military officer and explorer in Africa. Marchand is best known for commanding the French expeditionary ...

had left Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; wo, Ndakaaru) (from daqaar ''tamarind''), is the capital and largest city of Senegal. The city of Dakar proper has a population of 1,030,594, whereas the population of the Dakar metropolitan area is estimated at 3.94 million in 2 ...

in March 1896 with the aim of conquering the Sudan, seizing control of the Nile as it flowed into Egypt, and forcing the British out of Egypt; thus restoring Egypt to the place within the French sphere of influence that it had had prior to 1882. Salisbury feared that if the British did not conquer the Sudan, the French would. He had supported Italy's ambitions to conquer Ethiopia in the hope that the Italians would keep the French out of Ethiopia. The Italian attempt to conquer Ethiopia, however, was going very badly by early 1896, and ended with the Italians being annihilated at the Battle of Adowa

The Battle of Adwa (; ti, ውግእ ዓድዋ; , also spelled ''Adowa'') was the climactic battle of the First Italo-Ethiopian War. The Ethiopian forces defeated the Italian invading force on Sunday 1 March 1896, near the town of Adwa. The de ...

in March 1896. In March 1896, with the Italians visibly failing and the ''Mahdiyah'' state threatening to conquer Eritrea, Salisbury ordered Kitchener to invade northern Sudan, ostensibly for the purpose of distracting the ''Ansar'' (whom the British called "Dervishes") from attacking the Italians.

Kitchener won victories at the Battle of Ferkeh in June 1896 and the Battle of Hafir in September 1896, earning him national fame in the United Kingdom and promotion to major-general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

on 25 September 1896. Kitchener's cold personality and his tendency to drive his men hard made him widely disliked by his fellow officers. One officer wrote about Kitchener in September 1896: "He was always inclined to bully his own entourage, as some men are rude to their wives. He was inclined to let off his spleen on those around him. He was often morose and silent for hours together ... he was even morbidly afraid of showing any feeling or enthusiasm, and he preferred to be misunderstood rather than be suspected of human feeling." Kitchener had served on the Wolseley expedition to rescue General Gordon at Khartoum, and was convinced that the expedition failed because Wolseley had used boats coming up the Nile to bring his supplies. Kitchener wanted to build a railroad to supply the Anglo-Egyptian army, and assigned the task of constructing the Sudan Military Railroad to a Canadian railroad builder, Percy Girouard, for whom he had specifically asked.

Kitchener achieved further successes at the Battle of Atbara

The Battle of Atbara also known as the Battle of the Atbara River took place during the Second Sudan War. Anglo-Egyptian forces defeated 15,000 Sudanese rebels, called Mahdists or Dervishes, on the banks of the River Atbara. The battle proved to ...

in April 1898, and then the Battle of Omdurman

The Battle of Omdurman was fought during the Anglo-Egyptian conquest of Sudan between a British–Egyptian expeditionary force commanded by British Commander-in-Chief (sirdar) major general Horatio Herbert Kitchener and a Sudanese army of the M ...

in September 1898. After marching to the walls of Khartoum, he placed his army into a crescent shape with the Nile to the rear, together with the gunboats in support. This enabled him to bring overwhelming firepower against any attack of the ''Ansar'' from any direction, though with the disadvantage of having his men spread out thinly, with hardly any forces in reserve. Such an arrangement could have proven disastrous if the ''Ansar'' had broken through the thin khaki line. At about 5 a.m. on 2 September 1898, a huge force of ''Ansar'', under the command of the Khalifa himself, came out of the fort at Omdurman, marching under their black banners inscribed with Koranic quotations in Arabic; this led Bennet Burleigh, the Sudan correspondent of ''The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a national British daily broadsheet newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed across the United Kingdom and internationally.

It was fo ...

'', to write: "It was not alone the reverberation of the tread of horses and men's feet I heard and seemed to feel as well as hear, but a voiced continuous shouting and chanting-the Dervish invocation and battle challenge "Allah e Allah Rasool Allah el Mahdi!" they reiterated in vociferous rising measure, as they swept over the intervening ground". Kitchener had the ground carefully studied so that his officers would know the best angle of fire, and had his army open fire on the ''Ansar'' first with artillery, then machine guns and finally rifles as the enemy advanced. A young Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

, serving as an army officer, wrote of what he saw: "A ragged line of men were coming on desperately, struggling forward in the face of the pitiless fireblack banners tossing and collapsing; white figures subsiding in dozens to the ground ... valiant men were struggling on through a hell of whistling metal, exploding shells, and spurting dustsuffering, despairing, dying". By about 8:30 am, much of the Dervish army was dead; Kitchener ordered his men to advance, fearing that the Khalifa might escape with what was left of his army to the fort of Omdurman, forcing Kitchener to lay siege to it.

Viewing the battlefield from horseback on the hill at Jebel Surgham, Kitchener commented: "Well, we have given them a damn good dusting". As the British and Egyptians advanced in columns, the Khalifa attempted to outflank and encircle the columns; this led to desperate hand-to-hand fighting. Churchill wrote of his own experience as the 21st Lancers cut their way through the ''Ansar'': "The collision was prodigious and for perhaps ten wonderful seconds, no man heeded his enemy. Terrified horses wedged in the crowd, bruised and shaken men, sprawling in heaps, struggle dazed and stupid, to their feet, panted and looked about them". The Lancers' onslaught carried them through the 12-men-deep ''Ansar'' line with the Lancers losing 71 dead and wounded while killing hundreds of the enemy. Following the annihilation of his army, the Khalifa ordered a retreat and early in the afternoon, Kitchener rode in triumph into Omdurman and immediately ordered that the thousands of Christians enslaved by the ''Ansar'' were now all free people. Kitchener lost fewer than 500 men while killing about 11,000 and wounding 17,000 of the ''Ansar''. Burleigh summed the general mood of the British troops: "At Last! Gordon has been avenged and justified. The dervishes have been overwhelming routed, Mahdism has been "smashed", while the Khalifa's capital of Omdurman has been stripped of its barbaric halo of sanctity and invulnerability. Kitchener promptly had the Mahdi's tomb

The Mahdi's tomb or ''qubba'' ( ar, قُبَّة) is located in Omdurman, Sudan. It was the burial place of Muhammad Ahmad, the leader of an Islamic revolt against the Ottoman-Egyptian occupation of Sudan in the late 19th century.

The Mahdist ...

blown up to prevent it from becoming a rallying point for his supporters, and had his bones scattered. Queen Victoria, who had wept when she heard of General Gordon's death, now wept for the man who had vanquished Gordon, asking whether it had been really necessary for Kitchener to desecrate the Mahdi's tomb.The body of the Mahdi was disinterred and beheaded. This symbolic decapitation echoed General Gordon's death at the hands of the Mahdist forces in 1885. The headless body of the Mahdi was thrown into the Nile. Kitchener kept the Mahdī's skull and it was rumoured that he intended to use it as a drinking cup or ink well. In a letter to his mother, Churchill wrote that the victory at Omdurman had been "disgraced by the inhuman slaughter of the wounded and ... Kitchener is responsible for this". There is no evidence that Kitchener ordered his men to shoot the wounded ''Ansar'' on the field of Omdurman, but he did give before the battle what the British journalist Mark Urban

Mark Lee Urban (born 26 January 1961) is a British journalist, historian, and broadcaster, and is currently the Diplomatic Editor and occasional presenter for BBC Two's ''Newsnight''.

His older brother is the film-maker Stuart Urban.

Educati ...

called a "mixed message", saying that mercy should be given, while at the same time saying "Remember Gordon" and that the enemy were all "murderers" of Gordon. The victory at Omdurman made Kitchener into a popular war hero, and gave him a reputation for efficiency and as a man who got things done. The journalist G. W. Steevens wrote in the ''Daily Mail

The ''Daily Mail'' is a British daily middle-market tabloid newspaper and news websitePeter Wilb"Paul Dacre of the Daily Mail: The man who hates liberal Britain", ''New Statesman'', 19 December 2013 (online version: 2 January 2014) publish ...

'' that "He itcheneris more like a machine than a man. You feel that he ought to be patented and shown with pride at the Paris International Exhibition. British Empire: Exhibit No. 1 ''hors concours'', the Sudan Machine". The shooting of the wounded at Omdurman, along with the desecration of the Mahdi's tomb, gave Kitchener a reputation for brutality that was to dog him for the rest of his life, and posthumously.

After Omdurman, Kitchener opened a special sealed letter from Salisbury that told him that Salisbury's real reason for ordering the conquest of the Sudan was to prevent France from moving into the Sudan, and that the talk of "avenging Gordon" had been just a pretext. Salisbury's letter ordered Kitchener to head south as soon as possible to evict Marchand before he got a chance to become well-established on the Nile. On 18 September 1898, Kitchener arrived at the French fort at Fashoda (present day Kodok, on the west bank of the Nile north of Malakal) and informed Marchand that he and his men had to leave the Sudan at once, a request Merchand refused, leading to a tense stand-off as French and British soldiers aimed their weapons at each other. During what became known as the Fashoda Incident

The Fashoda Incident, also known as the Fashoda Crisis ( French: ''Crise de Fachoda''), was an international incident and the climax of imperialist territorial disputes between Britain and France in East Africa, occurring in 1898. A French exped ...

, Britain and France almost went to war with each other. The Fashoda incident caused much jingoism and chauvinism on both sides of the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

; however, at Fashoda itself, despite the stand-off with the French, Kitchener established cordial relations with Marchand. They agreed that the tricolor would fly equally with the Union Jack and the Egyptian flag over the disputed fort at Fashoda. Kitchener was a Francophile

A Francophile, also known as Gallophile, is a person who has a strong affinity towards any or all of the French language, French history, French culture and/or French people. That affinity may include France itself or its history, language, cuisin ...

who spoke fluent French, and despite his reputation for brusque rudeness was very diplomatic and tactful in his talks with Marchand; for example, congratulating him on his achievement in crossing the Sahara in an epic trek from Dakar to the Nile. In November 1898, the crisis ended when the French agreed to withdraw from the Sudan. Several factors persuaded the French to back down. These included British naval superiority; the prospect of an Anglo-French war leading to the British gobbling up the entire French colonial empire after the defeat of the French Navy

The French Navy (french: Marine nationale, lit=National Navy), informally , is the maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the five military service branches of France. It is among the largest and most powerful naval forces in t ...

; the pointed statement from the Russian Emperor Nicholas II

Nicholas II or Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov; spelled in pre-revolutionary script. ( 186817 July 1918), known in the Russian Orthodox Church as Saint Nicholas the Passion-Bearer,. was the last Emperor of Russia, King of Congress Pola ...

that the Franco-Russian alliance applied only to Europe, and that Russia would not go to war against Britain for the sake of an obscure fort in the Sudan in which no Russian interests were involved; and the possibility that Germany might take advantage of an Anglo-French war to strike France.

Kitchener became Governor-General of the Sudan

This is a list of Egyptian and European colonial administrators (as well as leaders of the Mahdist State) responsible for the territory of the Turkish Sudan and the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, an area equivalent to modern-day Sudan and South Sud ...

in September 1898, and began a programme of restoring good governance. The programme had a strong foundation, based on education at Gordon Memorial College

Gordon Memorial College was an educational institution in Sudan. It was built between 1899 and 1902 as part of Lord Kitchener's wide-ranging educational reforms.

Named for General 'Chinese' Charles George Gordon of the British army, who was kill ...

as its centrepieceand not simply for the children of the local elites, for children from anywhere could apply to study. He ordered the mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

s of Khartoum rebuilt, instituted reforms which recognised Fridaythe Muslim holy dayas the official day of rest, and guaranteed freedom of religion to all citizens of the Sudan. He attempted to prevent evangelical Christian missionaries from trying to convert Muslims to Christianity.

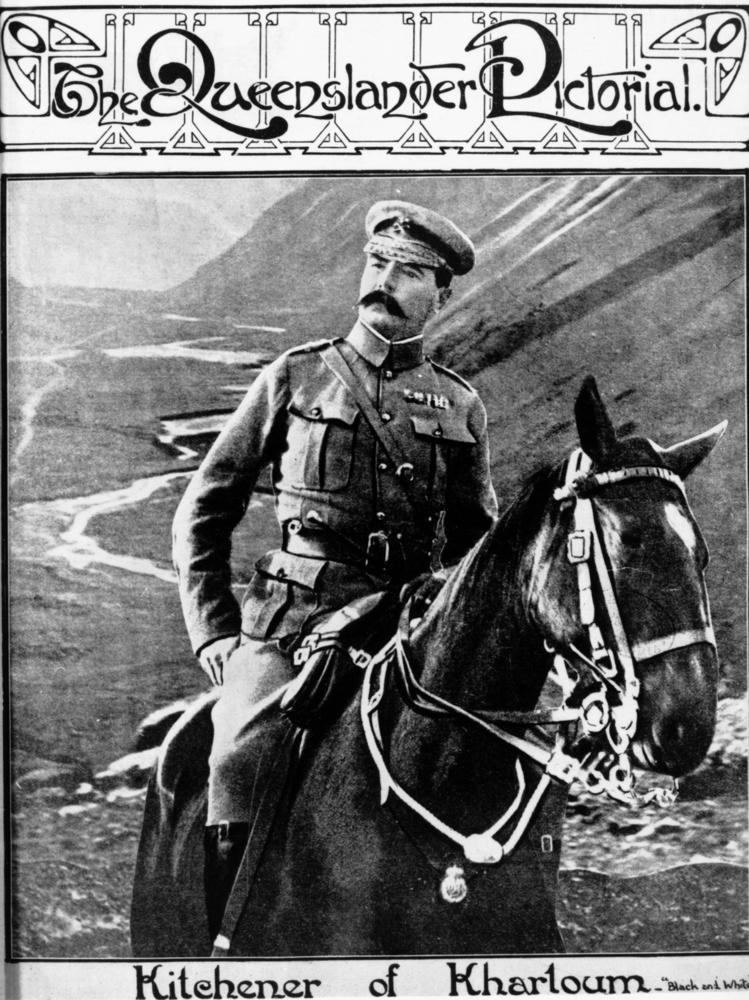

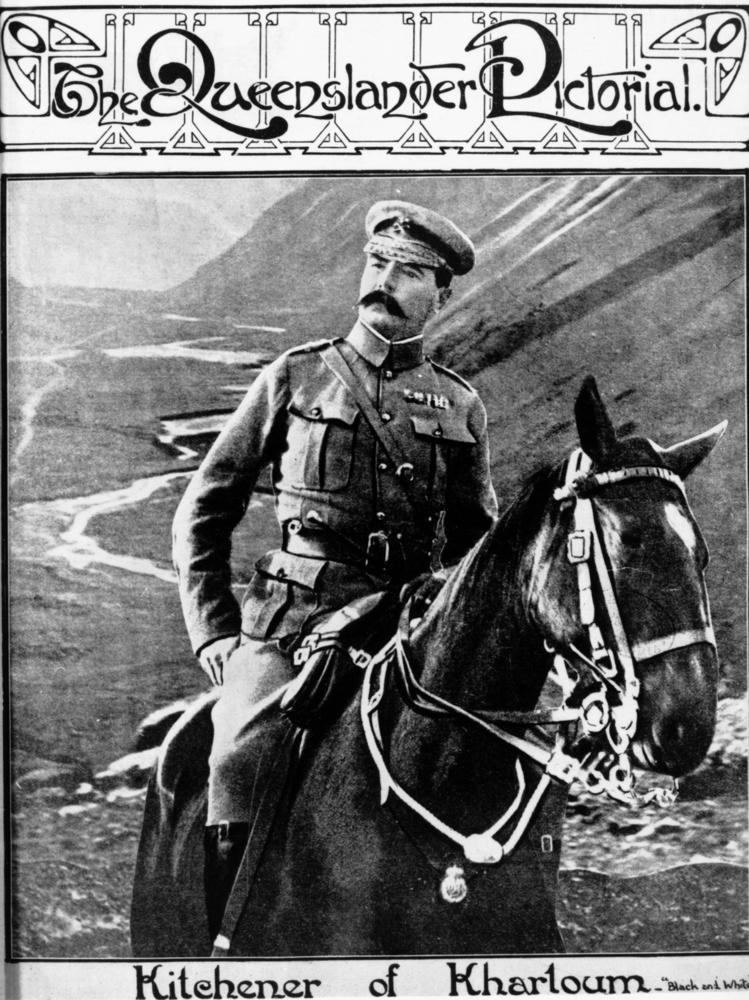

At this stage of his career Kitchener was keen to exploit the press, cultivating G. W. Steevens of the ''Daily Mail'' who wrote a book ''With Kitchener to Khartum''. Later, as his legend had grown, he was able to be rude to the press, on one occasion in the Second Boer War bellowing: "Get out of my way, you drunken swabs". He was created Baron Kitchener, of Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

and of Aspall in the County of Suffolk, on 31 October 1898.

Anglo-Boer War

During the

During the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

, Kitchener arrived in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

with Field Marshal Lord Roberts on the RMS '' Dunottar Castle'' along with massive British reinforcements in December 1899. Officially holding the title of chief of staff, he was in practice a second-in-command and was present at the relief of Kimberley

The siege of Kimberley took place during the Second Boer War at Kimberley, Cape Colony (present-day South Africa), when Boer forces from the Orange Free State and the Transvaal besieged the diamond mining town. The Boers moved quickly to tr ...

before leading an unsuccessful frontal assault at the Battle of Paardeberg

The Battle of Paardeberg or Perdeberg ("Horse Mountain") was a major battle during the Second Anglo-Boer War. It was fought near ''Paardeberg Drift'' on the banks of the Modder River in the Orange Free State near Kimberley.

Lord Methuen a ...

in February 1900. Kitchener was mentioned in despatches

To be mentioned in dispatches (or despatches, MiD) describes a member of the armed forces whose name appears in an official report written by a superior officer and sent to the high command, in which their gallant or meritorious action in the face ...

from Roberts several times during the early part of the war; in a despatch from March 1900 Roberts wrote how he was "greatly indebted to him for his counsel and cordial support on all occasions".

Following the defeat of the conventional Boer

Boers ( ; af, Boere ()) are the descendants of the Dutch-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape Colony, Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controll ...

forces, Kitchener succeeded Roberts as overall commander in November 1900. He was also promoted to lieutenant-general

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a three-star military rank (NATO code OF-8) used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the ...

on 29 November 1900 and to local general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

on 12 December 1900. He subsequently inherited and expanded the successful strategies devised by Roberts to force the Boer commandos

Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin">40_Commando.html" ;"title="Royal Marines from 40 Commando">Royal Marines from 40 Commando on patrol in the Sangin area of Afghanistan are pictured

A commando is a combatant, or operativ ...

to submit, including concentration camps and the burning of farms. Conditions in the concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, which had been conceived by Roberts as a form of control of the families whose farms he had destroyed, began to degenerate rapidly as the large influx of Boers outstripped the ability of the minuscule British force to cope. The camps lacked space, food, sanitation, medicine, and medical care, leading to rampant disease and a very high death rate for those Boers who entered. Eventually 26,370 women and children (81% were children) died in the concentration camps. The biggest critic of the camps was the English humanitarian and welfare worker Emily Hobhouse

Emily Hobhouse (9 April 1860 – 8 June 1926) was a British welfare campaigner, anti-war activist, and pacifist. She is primarily remembered for bringing to the attention of the British public, and working to change, the deprived conditions in ...

. She published a prominent report that highlighted atrocities committed by Kitchener's soldiers and administration, creating considerable debate in London about the war. Kitchener blocked Hobhouse from returning to South Africa by invoking martial law provisions.

Historian Caroline Elkins

Caroline Elkins (American, born Caroline Fox, 1969) is Professor of History and African and African American Studies at Harvard University, the Thomas Henry Carroll/Ford Foundation Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School ...

characterized Kitchener's conduct of the war as a "scorched earth policy", as his forces razed homesteads, poisoned wells and implemented concentration camps, as well as turned women and children into targets in the war.

The Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided f ...

, ending the War, was signed in May 1902 following a tense six months. During this period Kitchener struggled against Sir Alfred Milner

Alfred Milner, 1st Viscount Milner, (23 March 1854 – 13 May 1925) was a British statesman and colonial administrator who played a role in the formulation of British foreign and domestic policy between the mid-1890s and early 1920s. From D ...

, the Governor of the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

, and the British government. Milner was a hard-line conservative and wanted forcibly to Anglicise the Afrikaans people (the Boers), and Milner and the British government wanted to assert victory by forcing the Boers to sign a humiliating peace treaty; Kitchener wanted a more generous compromise peace treaty that would recognize certain rights for the Afrikaners and promise future self-government. He even entertained a peace treaty proposed by Louis Botha

Louis Botha (; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first prime minister of the Union of South Africa – the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer war hero during the Second Boer War, ...

and the other Boer leaders, although he knew the British government would reject the offer; this would have maintained the sovereignty of the South African Republic

The South African Republic ( nl, Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek, abbreviated ZAR; af, Suid-Afrikaanse Republiek), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer Republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it ...

and the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( nl, Oranje Vrijstaat; af, Oranje-Vrystaat;) was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeat ...

while requiring them to sign a perpetual treaty of alliance with the UK and grant major concessions to the British, such as equal rights for English with Dutch in their countries, voting rights for Uitlanders, and a customs and railway union with the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony ( nl, Kaapkolonie), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope, which existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when i ...

and Natal

NATAL or Natal may refer to:

Places

* Natal, Rio Grande do Norte, a city in Brazil

* Natal, South Africa (disambiguation), a region in South Africa

** Natalia Republic, a former country (1839–1843)

** Colony of Natal, a former British colony ( ...

. During Kitchener's posting in South Africa, Kitchener became acting High Commissioner of South Africa, and administrator of Transvaal and Orange River Colony in 1901.

Kitchener, who had been promoted to the substantive rank of general on 1 June 1902, was hosted to a farewell reception at Cape Town on 23 June, and left for the United Kingdom in the SS ''Orotava'' on the same day. He received an enthusiastic welcome on his arrival the following month. Landing in Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

on 12 July, he was greeted by the corporation, who presented him with the Freedom of the borough

The Freedom of the City (or Borough in some parts of the UK) is an honour bestowed by a municipality upon a valued member of the community, or upon a visiting celebrity or dignitary. Arising from the medieval practice of granting respected ...

. In London, he was met at the train station by The Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales ( cy, Tywysog Cymru, ; la, Princeps Cambriae/Walliae) is a title traditionally given to the heir apparent to the English and later British throne. Prior to the conquest by Edward I in the 13th century, it was used by the rulers o ...

, drove in a procession through streets lined by military personnel from 70 different units and watched by thousands of people, and received a formal welcome at St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Altho ...

. He also visited King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

, who was confined to his room recovering from his recent operation for appendicitis

Appendicitis is inflammation of the appendix. Symptoms commonly include right lower abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and decreased appetite. However, approximately 40% of people do not have these typical symptoms. Severe complications of a rup ...

, but wanted to meet the general on his arrival and to personally bestow on him the insignia of the Order of Merit

The Order of Merit (french: link=no, Ordre du Mérite) is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or for the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by K ...

(OM). Kitchener was created Viscount Kitchener, of Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum ( ; ar, الخرطوم, Al-Khurṭūm, din, Kaartuɔ̈m) is the capital of Sudan. With a population of 5,274,321, its metropolitan area is the largest in Sudan. It is located at the confluence of the White Nile, flowing n ...

and of the Vaal in the Colony of Transvaal

The Transvaal Colony () was the name used to refer to the Transvaal region during the period of direct British rule and military occupation between the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 when the South African Republic was dissolved, and the ...

and of Aspall in the County of Suffolk, on 28 July 1902.

Court-martial of Breaker Morant

In the Breaker Morant case, five Australian officers and one English officer of an irregular unit, the Bushveldt Carbineers, werecourt-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed for summarily executing twelve Boer prisoners, and also for the murder of a German missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Tho ...

believed to be a Boer sympathiser, all allegedly under unwritten orders approved by Kitchener. The celebrated horseman and bush poet Lt. Harry "Breaker" Morant and Lt. Peter Handcock

Peter Joseph Handcock (17 February 1868 – 27 February 1902) was an Australian-born Veterinary Lieutenant and convicted war criminal who served in the Bushveldt Carbineers during the Boer War in South Africa.

After a court martial, Handcock (a ...

were found guilty, sentenced to death, and shot by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French ''fusil'', rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are us ...

at Pietersburg

Polokwane (, meaning "Sanctuary" in Northern SothoPolokwane - The Heart of the Limpopo Province ...

on 27 February 1902. Their death warrants were personally signed by Kitchener. He reprieved a third soldier, Lt. George Witton, who served 28 months before being released.

India

In late 1902 Kitchener was appointed Commander-in-Chief, India, and arrived there to take up the position in November, in time to be in charge during the January 1903

In late 1902 Kitchener was appointed Commander-in-Chief, India, and arrived there to take up the position in November, in time to be in charge during the January 1903 Delhi Durbar

The Delhi Durbar ( lit. "Court of Delhi") was an Indian imperial-style mass assembly organized by the British at Coronation Park, Delhi, India, to mark the succession of an Emperor or Empress of India. Also known as the Imperial Durbar, it was ...

. He immediately began the task of reorganising the Indian Army

The Indian Army is the land-based branch and the largest component of the Indian Armed Forces. The President of India is the Supreme Commander of the Indian Army, and its professional head is the Chief of Army Staff (COAS), who is a four- ...

. Kitchener's plan "The Reorganisation and Redistribution of the Army in India" recommended preparing the Indian Army for any potential war by reducing the size of fixed garrisons and reorganising it into two armies, to be commanded by Generals Sir Bindon Blood and George Luck.

While many of the Kitchener Reforms

The British Indian Army, commonly referred to as the Indian Army, was the main military of the British Raj before its dissolution in 1947. It was responsible for the defence of the British Indian Empire, including the princely states, which co ...

were supported by the Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory. The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the French word ''roy'', meaning "k ...

, Lord Curzon of Kedleston, who had originally lobbied for Kitchener's appointment, the two men eventually came into conflict. Curzon wrote to Kitchener advising him that signing himself "Kitchener of Khartoum" took up too much time and space – Kitchener commented on the pettiness of this (Curzon simply signed himself "Curzon" as an hereditary peer, although he later took to signing himself "Curzon of Kedleston"). They also clashed over the question of military administration, as Kitchener objected to the system whereby transport and logistics were controlled by a "Military Member" of the Viceroy's Council. The Commander-in-Chief won the crucial support of the government in London, and the Viceroy chose to resign.

Later events proved Curzon was right in opposing Kitchener's attempts to concentrate all military decision-making power in his own office. Although the offices of Commander-in-Chief and Military Member were now held by a single individual, senior officers could approach only the Commander-in-Chief directly. In order to deal with the Military Member, a request had to be made through the Army Secretary, who reported to the Indian Government and had right of access to the Viceroy. There were even instances when the two separate bureaucracies produced different answers to a problem, with the Commander-in-Chief disagreeing with himself as Military Member. This became known as "the canonisation of duality". Kitchener's successor,

Later events proved Curzon was right in opposing Kitchener's attempts to concentrate all military decision-making power in his own office. Although the offices of Commander-in-Chief and Military Member were now held by a single individual, senior officers could approach only the Commander-in-Chief directly. In order to deal with the Military Member, a request had to be made through the Army Secretary, who reported to the Indian Government and had right of access to the Viceroy. There were even instances when the two separate bureaucracies produced different answers to a problem, with the Commander-in-Chief disagreeing with himself as Military Member. This became known as "the canonisation of duality". Kitchener's successor, General

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of highest military ranks, high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air forces, space forces, and marines or naval infantry.

In some usages the term "general officer" refers t ...

Sir O'Moore Creagh, was nicknamed "no More K", and concentrated on establishing good relations with the Viceroy, Lord Hardinge.

Kitchener presided over the Rawalpindi Parade in 1905 to honour the Prince and Princess of Wales's visit to India. That same year Kitchener founded the Indian Staff College at Quetta

Quetta (; ur, ; ; ps, کوټه) is the tenth List of cities in Pakistan by population, most populous city in Pakistan with a population of over 1.1 million. It is situated in Geography of Pakistan, south-west of the country close to the ...

(now the Pakistan Command and Staff College

( ''romanized'': Pir Sho Biyamooz Saadi)English: Grow old, learning Saadi

ur, سیکھتے ہوئے عمر رسیدہ ہو جاؤ، سعدی

, established = (as the ''Army Staff College'' in Deolali, British India)

, closed ...

), where his portrait still hangs. His term of office as Commander-in-Chief, India, was extended by two years in 1907.

Kitchener was promoted to the highest Army rank,

Kitchener was promoted to the highest Army rank, Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, ordinarily senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army and as such few persons are appointed to it. It is considered as ...

, on 10 September 1909 and went on a tour of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

. He aspired to be Viceroy of India

The Governor-General of India (1773–1950, from 1858 to 1947 the Viceroy and Governor-General of India, commonly shortened to Viceroy of India) was the representative of the monarch of the United Kingdom and after Indian independence in 19 ...

, but the Secretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India Secretary or the Indian Secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of th ...

, John Morley

John Morley, 1st Viscount Morley of Blackburn, (24 December 1838 – 23 September 1923) was a British Liberal statesman, writer and newspaper editor.

Initially, a journalist in the North of England and then editor of the newly Liberal-leani ...

, was not keen and hoped to send him instead to Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

as Commander-in-Chief of British forces in the Mediterranean, even to the point of announcing the appointment in the newspapers. Kitchener pushed hard for the Viceroyalty, returning to London to lobby Cabinet ministers and the dying King Edward VII

Edward VII (Albert Edward; 9 November 1841 – 6 May 1910) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and Emperor of India, from 22 January 1901 until his death in 1910.

The second child and eldest son of Queen Victoria a ...

, from whom, whilst collecting his field marshal's baton, Kitchener obtained permission to refuse the Malta job. However, Morley could not be moved. This was perhaps in part because Kitchener was thought to be a Tory (the Liberals were in office at the time); perhaps due to a Curzon-inspired whispering campaign; but most importantly because Morley, who was a Gladstonian

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

and thus suspicious of imperialism, felt it inappropriate, after the recent grant of limited self-government under the 1909 Indian Councils Act, for a serving soldier to be Viceroy (in the event, no serving soldier was appointed Viceroy until Lord Wavell in 1943, during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

). The prime minister, H. H. Asquith

Herbert Henry Asquith, 1st Earl of Oxford and Asquith, (12 September 1852 – 15 February 1928), generally known as H. H. Asquith, was a British statesman and Liberal Party politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom f ...

, was sympathetic to Kitchener but was unwilling to overrule Morley, who threatened resignation, so Kitchener was finally turned down for the post of Viceroy of India in 1911.

From 22 to 24 June 1911, Kitchener took part in the Coronation of King George V and Mary. Kitchener assumed the role of Captain of the Escort, responsible for the personal protection of the royals during the coronation. In this capacity, Kitchener was also the Field Marshal, In Command of the Troops, and assumed command of the 55,000 British and imperial soldiers present in London. During the Coronation ceremony itself, Kitchener acted as Third Sword, one of the four swords tasked with guarding the monarch. Later, in November 1911, Kitchener hosted the King and Queen in Port Said

Port Said ( ar, بورسعيد, Būrsaʿīd, ; grc, Πηλούσιον, Pēlousion) is a city that lies in northeast Egypt extending about along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, north of the Suez Canal. With an approximate population of 6 ...

, Egypt while they were on their way to India for the Delhi Durbar

The Delhi Durbar ( lit. "Court of Delhi") was an Indian imperial-style mass assembly organized by the British at Coronation Park, Delhi, India, to mark the succession of an Emperor or Empress of India. Also known as the Imperial Durbar, it was ...

to assume the titles of Emperor and Empress of India.

Return to Egypt

In June 1911 Kitchener then returned to Egypt as British Agent and Consul-General in Egypt during the formal reign ofAbbas Hilmi II

Abbas II Helmy Bey (also known as ''ʿAbbās Ḥilmī Pāshā'', ar, عباس حلمي باشا) (14 July 1874 – 19 December 1944) was the last Khedive ( Ottoman viceroy) of Egypt and Sudan, ruling from 8January 1892 to 19 December 191 ...

as Khedive

Khedive (, ota, خدیو, hıdiv; ar, خديوي, khudaywī) was an honorific title of Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Kh ...

.

At the time of the Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, a ...

(summer 1911), Kitchener told the Committee of Imperial Defence that he expected the Germans to walk through the French "like partridges" and he informed Lord Esher

Viscount Esher, of Esher in the County of Surrey, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created on 11 November 1897 for the prominent lawyer and judge William Brett, 1st Baron Esher, upon his retirement as Master of the Rolls ...

"that if they imagined that he was going to command the Army in France he would see them damned first".

He was created Earl Kitchener

Earl Kitchener, of Khartoum and of Broome in the County of Kent, was a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1914 for the famous soldier Field Marshal Herbert Kitchener, 1st Viscount Kitchener of Khartoum. He had alread ...

, of Khartoum and of Broome in the County of Kent, on 29 June 1914.

During this period he became a proponent of Scouting

Scouting, also known as the Scout Movement, is a worldwide youth movement employing the Scout method, a program of informal education with an emphasis on practical outdoor activities, including camping, woodcraft, aquatics, hiking, backpacking ...

and coined the phrase "once a Scout, always a Scout".

First World War

1914

Raising the New Armies

At the outset of theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the prime minister, Asquith, quickly had Kitchener appointed Secretary of State for War

The Secretary of State for War, commonly called War Secretary, was a secretary of state in the Government of the United Kingdom, which existed from 1794 to 1801 and from 1854 to 1964. The Secretary of State for War headed the War Office and ...

; Asquith had been filling the job himself as a stopgap following the resignation of Colonel Seely over the Curragh Incident

The Curragh incident of 20 March 1914, sometimes known as the Curragh mutiny, occurred in the Curragh, County Kildare, Ireland. The Curragh Camp was then the main base for the British Army in Ireland, which at the time still formed part of the ...

earlier in 1914. Kitchener was in Britain on his annual summer leave, between 23 June and 3 August 1914, and had boarded a cross-Channel steamer to commence his return trip to Cairo when he was recalled to London to meet with Asquith. War was declared at 11pm the next day.

Against cabinet opinion, Kitchener correctly predicted a long war that would last at least three years, require huge new armies to defeat Germany, and cause huge casualties before the end would come. Kitchener stated that the conflict would plumb the depths of manpower "to the last million". A massive recruitment campaign began, which soon featured a distinctive poster of Kitchener, taken from a magazine front cover. It may have encouraged large numbers of volunteers, and has proven to be one of the most enduring images of the war, having been copied and parodied many times since. Kitchener built up the "New Armies" as separate units because he distrusted the Territorials from what he had seen with the French Army in 1870. This may have been a mistaken judgement, as the British reservists of 1914 tended to be much younger and fitter than their French equivalents a generation earlier.

Cabinet Secretary

Against cabinet opinion, Kitchener correctly predicted a long war that would last at least three years, require huge new armies to defeat Germany, and cause huge casualties before the end would come. Kitchener stated that the conflict would plumb the depths of manpower "to the last million". A massive recruitment campaign began, which soon featured a distinctive poster of Kitchener, taken from a magazine front cover. It may have encouraged large numbers of volunteers, and has proven to be one of the most enduring images of the war, having been copied and parodied many times since. Kitchener built up the "New Armies" as separate units because he distrusted the Territorials from what he had seen with the French Army in 1870. This may have been a mistaken judgement, as the British reservists of 1914 tended to be much younger and fitter than their French equivalents a generation earlier.

Cabinet Secretary Maurice Hankey

Maurice Pascal Alers Hankey, 1st Baron Hankey, (1 April 1877 – 26 January 1963) was a British civil servant who gained prominence as the first Cabinet Secretary and later made the rare transition from the civil service to ministerial office. ...

wrote of Kitchener:

However, Ian Hamilton later wrote of Kitchener "he hated organisations; he smashed organisations ... he was a Master of Expedients".

Deploying the BEF

At the War Council (5 August) Kitchener and Lieutenant GeneralSir Douglas Haig

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, (; 19 June 1861 – 29 January 1928) was a senior officer of the British Army. During the First World War, he commanded the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) on the Western Front from late 1915 until ...

argued that the BEF should be deployed at Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; pcd, Anmien, or ) is a city and commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme department in the region of Hauts-de-France. In 2021, the population of ...