Homage to Catalonia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Homage to Catalonia'' is

The

The

Eyewitness in Barcelona - George Orwell , Workers' Liberty

was rejected by editor

and a praiseful review of

He describes the deficiencies of the POUM workers' militia, the absence of weapons, the recruits mostly boys of sixteen or seventeen ignorant of the meaning of war, half-complains about the sometimes frustrating tendency of Spaniards to put things off until "''mañana''" (tomorrow), notes his struggles with Spanish (or more usually, the local use of

He describes the deficiencies of the POUM workers' militia, the absence of weapons, the recruits mostly boys of sixteen or seventeen ignorant of the meaning of war, half-complains about the sometimes frustrating tendency of Spaniards to put things off until "''mañana''" (tomorrow), notes his struggles with Spanish (or more usually, the local use of

Orwell himself went on to write a poem about the Italian militiaman he described in the book's opening pages. The poem was included in Orwell's 1942 essay "Looking Back on the Spanish War", published in '' New Road'' in 1943. The closing phrase of the poem, "No bomb that ever burst shatters the crystal spirit", was later taken by

Orwell himself went on to write a poem about the Italian militiaman he described in the book's opening pages. The poem was included in Orwell's 1942 essay "Looking Back on the Spanish War", published in '' New Road'' in 1943. The closing phrase of the poem, "No bomb that ever burst shatters the crystal spirit", was later taken by

"In Canada and Abroad: The Diverse Publishing Career of George Woodcock".

Retrieved 19 August 2013. In 1995

''Homage to Catalonia''

– Searchable, indexed etext.

Complete book with publication data and search option.

''Homage to Catalonia''

Complete book as plain text.

– an essay written 6 years later. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Homage To Catalonia 1938 non-fiction books Anarchism in Spain Barcelona in popular culture Books about anarchism Books by George Orwell History of Catalonia Political autobiographies POUM Secker & Warburg books Spanish Civil War books Works about Stalinism

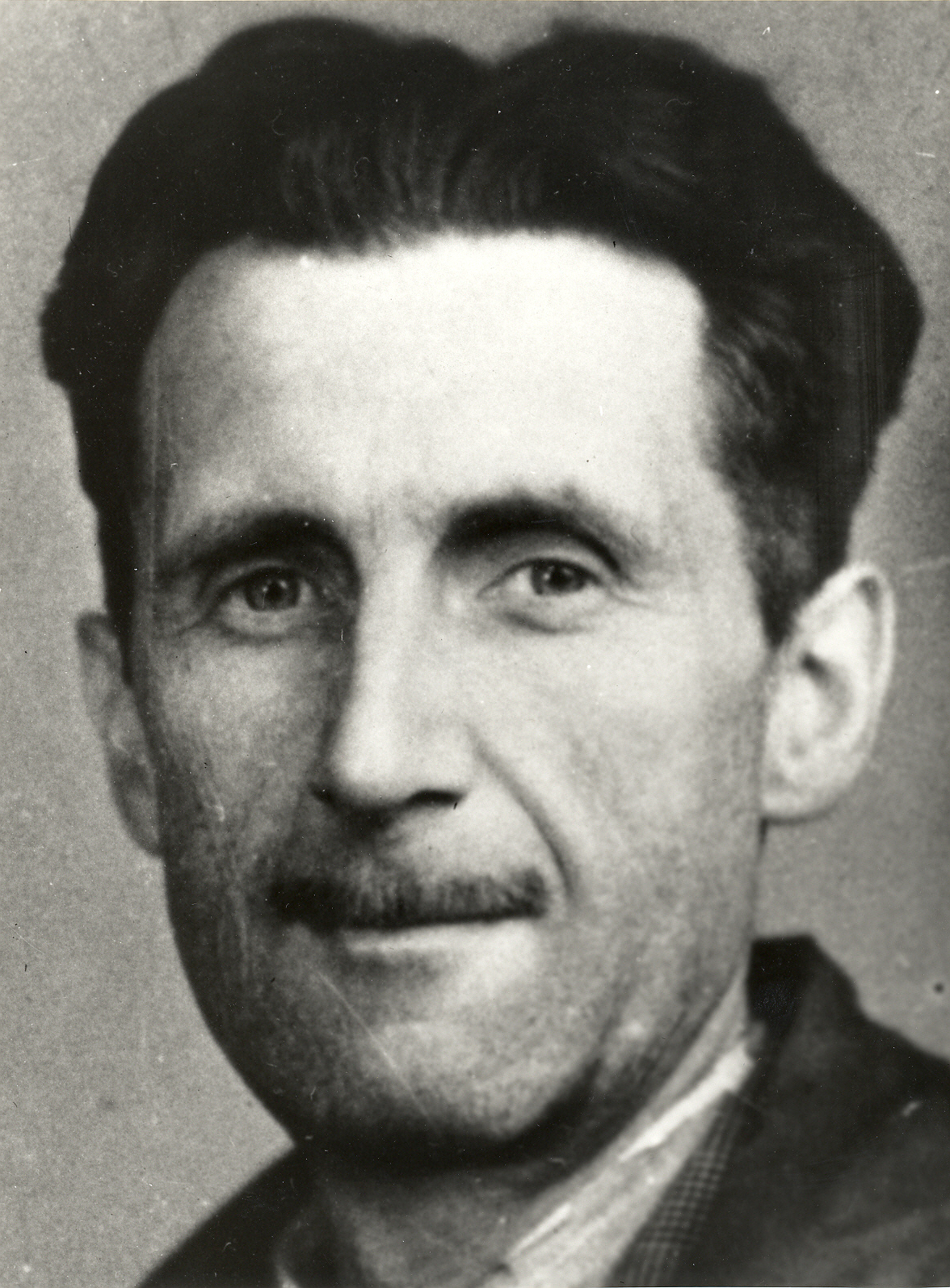

George Orwell

Eric Arthur Blair (25 June 1903 – 21 January 1950), better known by his pen name George Orwell, was an English novelist, essayist, journalist, and critic. His work is characterised by lucid prose, social criticism, opposition to totalitar ...

's personal account of his experiences and observations fighting in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

for the POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification ( es, Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, POUM; ca, Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active a ...

militia of the Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

army.

Published in 1938 (about a year before the war ended) with little commercial success, it gained more attention in the 1950s following the success of Orwell's better-known works ''Animal Farm

''Animal Farm'' is a beast fable, in the form of satirical allegorical novella, by George Orwell, first published in England on 17 August 1945. It tells the story of a group of farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, hoping to c ...

'' (1945) and ''Nineteen Eighty-Four

''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' (also stylised as ''1984'') is a dystopian social science fiction novel and cautionary tale written by the English writer George Orwell. It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Orwell's ninth and final ...

'' (1949).

Covering the period between December 1936 and June 1937, Orwell recounts Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

's revolutionary fervor during his training in Barcelona, his boredom on the front lines in Aragon

Aragon ( , ; Spanish and an, Aragón ; ca, Aragó ) is an autonomous community in Spain, coextensive with the medieval Kingdom of Aragon. In northeastern Spain, the Aragonese autonomous community comprises three provinces (from north to sou ...

, his involvement in the interfactional May Days

The May Days, sometimes also called May Events, refer to a series of clashes between 3 and 8 May 1937 during which factions on the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War engaged one another in street battles in various parts of Catalonia, ...

conflict back in Barcelona on leave, his getting shot in the throat back on the front lines, and his escape to France after the POUM was declared an illegal organization.

The war was one of the defining events of his political outlook and a significant part of what led him to write in 1946, "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, ''against'' totalitarianism and ''for'' democratic socialism

Democratic socialism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing political philosophy that supports political democracy and some form of a socially owned economy, with a particular emphasis on economic democracy, workplace democracy, and workers' self- ...

, as I understand it."

Background

Historical context

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

broke out with a military coup in July 1936 after months of tension following a narrow victory by the leftist Popular Front

A popular front is "any coalition of working-class and middle-class parties", including liberal and social democratic ones, "united for the defense of democratic forms" against "a presumed Fascist assault".

More generally, it is "a coalition ...

in the February 1936 Spanish general election. Rebelling forces coalesced as the Nationalists

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a group of people), Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: The ...

under the leadership of General Francisco Franco

Francisco Franco Bahamonde (; 4 December 1892 – 20 November 1975) was a Spanish general who led the Nationalist forces in overthrowing the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War and thereafter ruled over Spain from 193 ...

and attempted to take over cities that remained under government control.

The Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

side, which viewed the Nationalists as fascists, was made up of several factions including socialists, anarchists, and communists. There was infighting between these factions, which Orwell details in his chapters on the May Days of Barcelona

The May Days, sometimes also called May Events, refer to a series of clashes between 3 and 8 May 1937 during which factions on the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War engaged one another in street ...

.

Biographical context

Joining the war

Orwell left for Spain just before Christmas 1936, shortly after submitting ''The Road to Wigan Pier

''The Road to Wigan Pier'' is a book by the English writer George Orwell, first published in 1937. The first half of this work documents his sociological investigations of the bleak living conditions among the working class in Lancashire and Yor ...

'' for publication, the first book in which he explicitly espouses socialism.

Within the first few pages of ''Homage to Catalonia'', Orwell writes, "I had come to Spain with some notion of writing newspaper articles, but I had joined the militia almost immediately, because at that time and in that atmosphere it seemed the only conceivable thing to do." However, it has been suggested that Orwell intended all along to enlist.

Orwell had been told that he would not be permitted to enter Spain without some supporting documents from a British left-wing organisation, so he sought the assistance of the British Communist Party

The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) was the largest communist organisation in Britain and was founded in 1920 through a merger of several smaller Marxist groups. Many miners joined the CPGB in the 1926 general strike. In 1930, the CPGB ...

. When its leader, Harry Pollitt

Harry Pollitt (22 November 1890 – 27 June 1960) was a British communist who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) from 1929 to September 1939 and again from 1941 until his death in 1960. Pollitt spent ...

, asked if he would join the International Brigades

The International Brigades ( es, Brigadas Internacionales) were military units set up by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The organization existed f ...

, Orwell replied that he wanted to see for himself what was happening first. After Pollitt refused to help, Orwell contacted the Independent Labour Party (ILP), whose officials agreed to help him. They accredited Orwell as a correspondent for their weekly paper, the ''New Leader

''The New Leader'' (1924–2010) was an American political and cultural magazine.

History

''The New Leader'' began in 1924 under a group of figures associated with the Socialist Party of America, such as Eugene V. Debs and Norman Thomas. It was p ...

'', which provided Orwell the means to go legitimately to Spain. The ILP issued him a letter of introduction to their representative in Barcelona, John McNair.

Upon arriving in Spain, Orwell is reported to have told McNair, "I have come to Spain to join the militia to fight against Fascism." While McNair also describes Orwell as expressing a desire to write "some articles" for the ''New Statesman and Nation'' with an intention "to stir working-class opinion in Britain and France", when presented the opportunity to write, Orwell told him writing "was quite secondary and his main reason for coming was to fight against Fascism." McNair took Orwell to the POUM

The Workers' Party of Marxist Unification ( es, Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista, POUM; ca, Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista) was a Spanish communist party formed during the Second Spanish Republic, Second Republic and mainly active a ...

(Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

: ''Partit Obrer d'Unificació Marxista;'' English: Workers' Party of Marxist Unification), an anti-Stalinist

The anti-Stalinist left is an umbrella term for various kinds of left-wing political movements that opposed Joseph Stalin, Stalinism and the actual system of governance Stalin implemented as leader of the Soviet Union between 1927 and 1953. Th ...

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a s ...

party.

By Orwell's own admission, it was somewhat by chance that he joined the POUM: "I had only joined the P.O.U.M. militia rather than any other because I happened to arrive in Barcelona with I.L.P. papers." He later notes, "As far as my purely personal preferences went I would have liked to join the Anarchists." He also nearly joined Communist International

The Communist International (Comintern), also known as the Third International, was a Soviet-controlled international organization founded in 1919 that advocated world communism. The Comintern resolved at its Second Congress to "struggle by a ...

's International Column midway through his tour because he thought they were likeliest to send him to Madrid, where he wanted to join the action.

Writing

Orwell wrote diaries, made press-cuttings, and took photographs during his time in Spain, but they were all stolen before he left. In May 1937, he wrote the publisher of his previous books saying, "I greatly hope I come out of this alive if only to write a book about it." According to his eventual publisher, "''Homage'' was begun in February937

Year 937 ( CMXXXVII) was a common year starting on Sunday (link will display the full calendar) of the Julian calendar.

Events

By place

Europe

* A Hungarian army invades Burgundy, and burns the city of Tournus. Then they go southward ...

in the trenches, written on scraps, the backs of envelopes, toilet paper. The written material was sent to Barcelona to McNair's office, where his wife Eileen Blair

Eileen Maud Blair (née O'Shaughnessy, 25 September 1905 – 29 March 1945) was the first wife of George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair). During World War II, she worked for the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information in London and ...

, working as a volunteer, typed it out section by section. Slowly it grew into a sizable parcel. McNair kept it in his own room."

Upon escaping across the French border in June 1937, he stopped at the first post office available to telegram the ''National Statesman'', asking if it would like a first-hand article. The offer was accepted but the article, "Eye-witness in BarcelonaEyewitness in Barcelona - George Orwell , Workers' Liberty

was rejected by editor

Kingsley Martin

Basil Kingsley Martin (28 July 1897 – 16 February 1969) usually known as Kingsley Martin, was a British journalist who edited the left-leaning political magazine the ''New Statesman'' from 1930 to 1960.

Early life

He was the son of (Dav ...

on grounds that his writing "could cause trouble" (it was picked up by ''Controversy''). In the months after leaving Spain, Orwell wrote a number of essays on the war, notably " Spilling the Spanish Beansbr>Spilling the Spanish Beans , The Orwell Foundationand a praiseful review of

Franz Borkenau

Franz Borkenau (December 15, 1900 – May 22, 1957) was an Austrian writer. Borkenau was born in Vienna, Austria, the son of a civil servant. As a university student in Leipzig, his main interests were Marxism and psychoanalysis. Borkenau is kno ...

's ''The Spanish Cockpit

''The Spanish Cockpit'' is a personal account of the Spanish Civil War written by Franz Borkenau and published in late 1937. It was based on his two wartime visits to Spain in August 1936 and January 1937, visiting Barcelona, Madrid, Toledo, Va ...

''.

Writing from his cottage at Wallington, Hertfordshire

Wallington is a small village and civil parish in the North Hertfordshire district, in the county of Hertfordshire, England, near the town of Baldock. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 Census was 150. Nearby villages include Rushden ...

, he finished around New Year's Day 1938.

Publication

The first edition was published in the United Kingdom in April 1938 bySecker & Warburg

Harvill Secker is a British publishing company formed in 2005 from the merger of Secker & Warburg and the Harvill Press.

History

Secker & Warburg

Secker & Warburg was formed in 1935 from a takeover of Martin Secker, which was in receivership, ...

after being rejected by Gollancz, the publisher of all Orwell's previous books, over concerns about the book's criticism of the Stalinists

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

in Spain. "Gollancz is of course part of the Communism-racket," Orwell wrote to Rayner Heppenstall

John Rayner Heppenstall (27 July 1911 in Lockwood, Huddersfield, Yorkshire, England – 23 May 1981 in Deal, Kent, England) was a British novelist, poet, diarist, and a BBC radio producer.John Wakeman, ''World Authors 1950-1970 : a companion volu ...

in July 1937. Orwell had learned of Warburg's potential willingness to publish anti-Stalinist socialist content in June, and in September a deal was signed for an advance of £150 (). "Ten years ago it was almost impossible to get anything printed in favour of Communism; today it is almost impossible to get anything printed in favour of Anarchism or 'Trotskyism'," Orwell wrote bitterly in 1938.

The book was not published in the United States until February 1952, with a preface by Lionel Trilling

Lionel Mordecai Trilling (July 4, 1905 – November 5, 1975) was an American literary critic, short story writer, essayist, and teacher. He was one of the leading U.S. critics of the 20th century who analyzed the contemporary cultural, social, ...

.

The only translation published in Orwell's lifetime was into Italian, in December 1948. A French translation by Yvonne Davet—with whom Orwell corresponded, commenting on her translation and providing explanatory notes—in 1938–39, was not published until 1955, five years after Orwell's death.

Per Orwell's wishes, the original chapters 5 and 11 were turned into appendices in some later editions. In 1986, Peter Davison

Peter Malcolm Gordon Moffett (born 13 April 1951), known professionally as Peter Davison, is an English actor with many credits in television dramas and sitcoms. He made his television acting debut in 1975 and became famous in 1978 as Tristan ...

published an edition with a few footnotes based on Orwell's own footnotes found among his papers after he died.

Chapter summaries

The appendices in this summary correspond to chapters 5 and 11 in editions that do not include appendices. Orwell felt these chapters, as journalistic accounts of the political situation in Spain, were out of place in the midst of the narrative and should be moved so that readers could ignore them if they wished.Chapter one

Orwell describes the atmosphere ofBarcelona

Barcelona ( , , ) is a city on the coast of northeastern Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within ci ...

in December 1936. "The anarchists were still in virtual control of Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

and the revolution was still in full swing ... It was the first time that I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle ... every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle

The hammer and sickle (Unicode: "☭") zh, s=锤子和镰刀, p=Chuízi hé liándāo or zh, s=镰刀锤子, p=Liándāo chuízi, labels=no is a symbol meant to represent proletarian solidarity, a union between agricultural and industri ...

... every shop and café had an inscription saying that it had been collectivized

Collective farming and communal farming are various types of, "agricultural production in which multiple farmers run their holdings as a joint enterprise". There are two broad types of communal farms: agricultural cooperatives, in which member ...

." Further to this, " The Anarchists" (referring to the Spanish CNT and FAI) were "in control", tipping was prohibited by workers themselves, and servile forms of speech, such as "''Señor''" or "''Don''", were abandoned. At the Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 19 ...

Barracks (formerly the Lepanto Barracks), militiamen were given instruction in the form of "parade-ground drill of the most antiquated, stupid kind; right turn, left turn, about turn, marching at attention in column of threes and all the rest of that useless nonsense".

He describes the deficiencies of the POUM workers' militia, the absence of weapons, the recruits mostly boys of sixteen or seventeen ignorant of the meaning of war, half-complains about the sometimes frustrating tendency of Spaniards to put things off until "''mañana''" (tomorrow), notes his struggles with Spanish (or more usually, the local use of

He describes the deficiencies of the POUM workers' militia, the absence of weapons, the recruits mostly boys of sixteen or seventeen ignorant of the meaning of war, half-complains about the sometimes frustrating tendency of Spaniards to put things off until "''mañana''" (tomorrow), notes his struggles with Spanish (or more usually, the local use of Catalan

Catalan may refer to:

Catalonia

From, or related to Catalonia:

* Catalan language, a Romance language

* Catalans, an ethnic group formed by the people from, or with origins in, Northern or southern Catalonia

Places

* 13178 Catalan, asteroid #1 ...

). He praises the generosity of the Catalan working class. Orwell leads to the next chapter by describing the "conquering-hero stuff"—parades through the streets and cheering crowds—that the militiamen experienced at the time he was sent to the Aragón front.

Chapter two

In January 1937, Orwell'scenturia

''Centuria'' (, plural ''centuriae'') is a Latin term (from the stem ''centum'' meaning one hundred) denoting military units originally consisting of 100 men. The size of the century changed over time, and from the first century BC through most ...

arrives in Alcubierre

Alcubierre is a municipality located in the province of Huesca, Aragon, Spain. According to the 2004 census (INE), the municipality has a population of 439 inhabitants.

This town gives its name to the Sierra de Alcubierre

Sierra de Alcubierre ...

, just behind the line fronting Zaragoza

Zaragoza, also known in English as Saragossa,''Encyclopædia Britannica'"Zaragoza (conventional Saragossa)" is the capital city of the Zaragoza Province and of the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributari ...

. He sketches the squalor of the region's villages and the "Fascist deserters" indistinguishable from themselves. On the third day rifles are handed out. Orwell's "was a German Mauser

Mauser, originally Königlich Württembergische Gewehrfabrik ("Royal Württemberg Rifle Factory"), was a German arms manufacturer. Their line of bolt-action rifles and semi-automatic pistols has been produced since the 1870s for the German arme ...

dated 1896 ... it was corroded and past praying for." The chapter ends on his centuria's arrival at trenches near Zaragoza and the first time a bullet nearly hit him. To his dismay, instinct made him duck.

Chapter three

In the hills around Zaragoza, Orwell experiences "mingled boredom and discomfort of stationary warfare," the mundaneness of a situation in which "each army had dug itself in and settled down on the hill-tops it had won." He praises the Spanishmilitia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

s for their relative social equality

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all individuals within a specific society have equal rights, liberties, and status, possibly including civil rights, freedom of expression, autonomy, and equal access to certain public goods and ...

, for their holding of the front while the army was trained in the rear, and for the "democratic 'revolutionary' type of discipline ... more reliable than might be expected." "'Revolutionary' discipline depends on political consciousness—on an understanding of ''why'' orders must be obeyed; it takes time to diffuse this, but it also takes time to drill a man into an automaton on the barrack-square."

Throughout the chapter Orwell describes the various shortages and problems at the front—firewood ("We were between two and three thousand feet above sea-level, it was mid winter and the cold was unspeakable"), food, candles, tobacco, and adequate munitions—as well as the danger of accidents inherent in a badly trained and poorly armed group of soldiers.

Chapter four

After some three weeks at the front, Orwell and the other English militiaman in his unit, Williams, join a contingent of fellow Englishmen sent out by theIndependent Labour Party

The Independent Labour Party (ILP) was a British political party of the left, established in 1893 at a conference in Bradford, after local and national dissatisfaction with the Liberals' apparent reluctance to endorse working-class candidates ...

to a position at Monte Oscuro, within sight of Zaragoza. "Perhaps the best of the bunch was Bob Smillie—the grandson of the famous miners' leader—who afterwards died such an evil and meaningless death in Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

." In this new position he witnesses the sometimes propagandistic shouting between the Rebel and Loyalist trenches and hears of the fall of Málaga

Málaga (, ) is a municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 578,460 in 2020, it is the second-most populous city in Andalusia after Seville and the sixth most pop ...

. "... every man in the militia believed that the loss of Malaga was due to treachery. It was the first talk I had heard of treachery or divided aims. It set up in my mind the first vague doubts about this war in which, hitherto, the rights and wrongs had seemed so beautifully simple." In February, he is sent with the other POUM militiamen 50 miles to make a part of the army besieging Huesca

Huesca (; an, Uesca) is a city in north-eastern Spain, within the autonomous community of Aragon. It is also the capital of the Spanish province of the same name and of the comarca of Hoya de Huesca. In 2009 it had a population of 52,059, almo ...

; he mentions the running joke phrase, "Tomorrow we'll have coffee in Huesca," attributed to a general commanding the Government troops who, months earlier, made one of many failed assaults on the town.

Chapter five (orig. ch. 6)

Orwell complains that on the eastern side of Huesca, where he was stationed, nothing ever seemed to happen—except the onslaught of spring, and, with it,lice

Louse ( : lice) is the common name for any member of the clade Phthiraptera, which contains nearly 5,000 species of wingless parasitic insects. Phthiraptera has variously been recognized as an order, infraorder, or a parvorder, as a result o ...

. He was in a ("so-called") hospital at Monflorite for ten days at the end of March 1937 with a poisoned hand that had to be lanced and put in a sling. He describes rats that "really were as big as cats, or nearly" (in Orwell's novel ''Nineteen Eighty-Four

''Nineteen Eighty-Four'' (also stylised as ''1984'') is a dystopian social science fiction novel and cautionary tale written by the English writer George Orwell. It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Orwell's ninth and final ...

'', the protagonist Winston Smith Winston Smith may refer to:

People

* Winston Smith (artist) (born 1952), American artist

* Winston Smith (athlete) (born 1982), Olympic track and field athlete

* Winston Boogie Smith (born ), American man killed by law enforcement in 2021

* Winst ...

has a phobia of rats that Orwell himself shared to a lesser degree). He makes reference to the lack of "religious feeling, in the orthodox sense," and that the Catholic Church was, "to the Spanish people, at any rate in Catalonia and Aragon, a racket, pure and simple." He muses that Christianity may have, to some extent, been replaced by Anarchism. The latter portion of the chapter briefly details various operations in which Orwell took part: silently advancing the Loyalist frontline by night, for example.

Chapter six (orig. ch. 7)

Orwell takes part in a "holding attack" on Huesca, designed to draw the Nationalist troops away from an Anarchist attack on "theJaca

Jaca (; in Aragonese: ''Chaca'' or ''Xaca'') is a city of northeastern Spain in the province of Huesca, located near the Pyrenees and the border with France. Jaca is an ancient fort on the Aragón River, situated at the crossing of two great ea ...

road." He suspects two of the bombs he threw may have killed their targets, but he cannot be sure. They capture the position and pull back with captured rifles and ammunition, but Orwell laments that they fled too hurriedly to bring back a telescope they had discovered, which Orwell sees as more useful than any weapons.

Chapter seven (orig. ch. 8)

Orwell shares memories of the 115 days he spent on the war front, and its influence on his political ideas, "... the prevailing mental atmosphere was that of Socialism ... the ordinary class-division of society had disappeared to an extent that is almost unthinkable in the money-tainted air of England ... the effect was to make my desire to see Socialism established much more actual than it had been before." By the time he left Spain, he had become a "convinced democratic Socialist." The chapter ends with Orwell's arrival in Barcelona on the afternoon of 26 April 1937. "And after that the trouble began."Chapter eight (orig. ch. 9)

Orwell details noteworthy changes in the social and political atmosphere of Barcelona when he returns after three months at the front. He describes a lack of revolutionary atmosphere and the class division that he had thought would not reappear, i.e., with visible division between rich and poor and the return of servile language. Orwell had been determined to leave the POUM, and confesses here that he "would have liked to join the Anarchists," but instead sought a recommendation to join the International Column, so that he could go to theMadrid front

The siege of Madrid was a two-and-a-half-year siege of the Republican-controlled Spanish capital city of Madrid by the Nationalist armies, under General Francisco Franco, during the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The city, besieged from Octo ...

. The latter half of this chapter is devoted to describing the conflict between the anarchist CNT and the socialist Unión General de Trabajadores

The Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT, General Union of Workers) is a major Spanish trade union, historically affiliated with the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE).

History

The UGT was founded 12 August 1888 by Pablo Iglesias Posse ...

(UGT) and the resulting cancellation of the May Day demonstration and the build-up to the street fighting of the Barcelona May Days

The May Days, sometimes also called May Events, refer to a series of clashes between 3 and 8 May 1937 during which factions on the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War engaged one another in street battles in various parts of Catalonia, ...

. "It was the antagonism between those who wished the revolution to go forward and those who wished to check or prevent it—ultimately, between Anarchists and Communists."

Chapter nine (orig. ch. 10)

Orwell relates his involvement in the Barcelona street fighting that began on 3 May when the Government Assault Guards tried to take the Telephone Exchange from the CNT workers who controlled it. For his part, Orwell acted as part of the POUM, guarding a POUM-controlled building. Although he realises that he is fighting on the side of the working class, Orwell describes his dismay at coming back to Barcelona on leave from the front only to get mixed up in street fighting. Assault Guards fromValencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

arrive—"All of them were armed with brand-new rifles ... vastly better than the dreadful old blunderbuss

The blunderbuss is a firearm with a short, large caliber barrel which is flared at the muzzle and frequently throughout the entire bore, and used with shot and other projectiles of relevant quantity or caliber. The blunderbuss is commonly consid ...

es we had at the front." The Communist-controlled Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia

The Unified Socialist Party of Catalonia ( ca, Partit Socialista Unificat de Catalunya, PSUC) was a communist political party active in Catalonia between 1936 and 1997. It was the Catalan branch of the Communist Party of Spain and the only party n ...

newspapers declare POUM to be a disguised Fascist organisation—"No one who was in Barcelona then ... will forget the horrible atmosphere produced by fear, suspicion, hatred, censored newspapers, crammed jails, enormous food queues, and prowling gangs ...." In his second appendix to the book, Orwell discusses the political issues at stake in the May 1937 Barcelona fighting, as he saw them at the time and later on, looking back.

Chapter ten (orig. ch. 12)

Orwell speculates on how the Spanish Civil War might turn out. Orwell predicts that the "tendency of the post-war Government ... is bound to be Fascistic." He returns to the front, where he is shot through the throat by a sniper, an injury that takes him out of the war. After spending some time in a hospital inLleida

Lleida (, ; Spanish: Lérida ) is a city in the west of Catalonia, Spain. It is the capital city of the province of Lleida.

Geographically, it is located in the Catalan Central Depression. It is also the capital city of the Segrià comarca, as ...

, he was moved to Tarragona

Tarragona (, ; Phoenician: ''Tarqon''; la, Tarraco) is a port city located in northeast Spain on the Costa Daurada by the Mediterranean Sea. Founded before the fifth century BC, it is the capital of the Province of Tarragona, and part of Tar ...

where his wound was finally examined more than a week after he'd left the front.

Chapter eleven (orig. ch. 13)

Orwell tells us of his various movements between hospitals in Siétamo,Barbastro

Barbastro (Latin: ''Barbastrum'' or ''Civitas Barbastrensis'', Aragonese: ''Balbastro'') is a city in the Somontano county, province of Huesca, Spain. The city (also known originally as Barbastra or Bergiduna) is at the junction of the rivers Cinc ...

, and Monzón

Monzón is a small city and municipality in the autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. Its population was 17,176 as of 2014. It is in the northeast (specifically the Cinca Medio district of the province of Huesca) and adjoins the rivers Cinca and ...

while getting his discharge papers stamped, after being declared medically unfit. He returns to Barcelona only to find that the POUM had been "suppressed": it had been declared illegal the very day he had left to obtain discharge papers and POUM members were being arrested without charge. "The attack on Huesca

Huesca (; an, Uesca) is a city in north-eastern Spain, within the autonomous community of Aragon. It is also the capital of the Spanish province of the same name and of the comarca of Hoya de Huesca. In 2009 it had a population of 52,059, almo ...

was beginning ... there must have been numbers of men who were killed without ever learning that the newspapers in the rear were calling them Fascists. This kind of thing is a little difficult to forgive." He sleeps that night in the ruins of a church; he cannot go back to his hotel because of the danger of arrest.

Chapter twelve (orig. ch. 14)

This chapter describes his visits accompanied by his wife toGeorges Kopp

Georges Kopp (October 10, 1902 – July 15, 1951) was a Belgian educated engineer and inventor of Russian descent, who volunteered in the fight against Nazism and is best known for his friendship with George Orwell, whom he commanded in the Spani ...

, unit commander of the ILP Contingent while Kopp was held in a Spanish makeshift jail—"really the ground floor of a shop." Having done all he could to free Kopp, ineffectively and at great personal risk, Orwell decides to leave Spain. Crossing the Pyrenees

The Pyrenees (; es, Pirineos ; french: Pyrénées ; ca, Pirineu ; eu, Pirinioak ; oc, Pirenèus ; an, Pirineus) is a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. It extends nearly from its union with the Cantabrian Mountains to C ...

frontier, he and his wife arrived in France "without incident".

Appendix one (orig. ch. 5)

Orwell explains the divisions within the Republican side: "On the one side the C.N.T.-F.A.I., the P.O.U.M., and a section of the Socialists, standing for workers’ control: on the other side the Right-wing Socialists, Liberals, and Communists, standing for centralized government and a militarized army." He also writes, "One of the dreariest effects of this war has been to teach me that the Left-wing press is every bit as spurious and dishonest as that of the Right."Appendix two (orig. ch. 11)

An attempt to dispel some of the myths in the foreign press at the time (mostly the pro-Communist press) about theMay Days

The May Days, sometimes also called May Events, refer to a series of clashes between 3 and 8 May 1937 during which factions on the Republican faction of the Spanish Civil War engaged one another in street battles in various parts of Catalonia, ...

, the street fighting that took place in Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

in early May 1937. This was between anarchists and POUM members, against Communist/government forces which sparked off when local police forces occupied the Telephone Exchange, which had until then been under the control of CNT workers. He relates the suppression of the POUM on 15–16 June 1937, gives examples of the Communist Press of the world—(''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were m ...

'', 21 June, "Spanish Trotskyists Plot With Franco"), indicates that Indalecio Prieto

Indalecio Prieto Tuero (30 April 1883 – 11 February 1962) was a Spanish politician, a minister and one of the leading figures of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) in the years before and during the Second Spanish Republic.

Early life ...

hinted, "fairly broadly ... that the government could not afford to offend the Communist Party while the Russians were supplying arms." He quotes Julián Zugazagoitia

Julián Zugazagoitia Mendieta (5 February 1899, Bilbao – 9 November 1940, Madrid) was a Spanish journalist and politician.

A member of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, he was close to Indalecio Prieto and the editor of the '' El Socialist ...

, the Minister of the Interior; "We have received aid from Russia and have had to permit certain actions which we did not like."

Reception

Sales

''Homage to Catalonia'' was initially commercially unsuccessful, selling only 683 copies in its first 6 months. By the time of Orwell's death in 1950, its initial print run of 1,500 copies had still not all sold. ''Homage to Catalonia'' re-emerged in the 1950s, following on the success of Orwell's later books.Reviews

Contemporary

Contemporary reviews of the book were mixed.John Langdon-Davies

John Eric Langdon-Davies (18 March 1897 – 5 December 1971) was a British author and journalist. He was a war correspondent during the Spanish Civil War and the Soviet-Finnish War. As a result of his experiences in Spain, he founded the Foster ...

wrote in the Communist Party's ''Daily Worker

The ''Daily Worker'' was a newspaper published in New York City by the Communist Party USA, a formerly Comintern-affiliated organization. Publication began in 1924. While it generally reflected the prevailing views of the party, attempts were m ...

'' that "the value of the book is that it gives an honest picture of the sort of mentality that toys with revolutionary romanticism but shies violently at revolutionary discipline. It should be read as a warning". Some Conservative and Catholic opponents of the Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), commonly known as the Second Spanish Republic (), was the form of government in Spain from 1931 to 1939. The Republic was proclaimed on 14 April 1931, after the deposition of King Alfonso XIII, and was dissolved on 1 A ...

felt vindicated by Orwell's attack on the role of the Communists in Spain; ''The Spectator

''The Spectator'' is a weekly British magazine on politics, culture, and current affairs. It was first published in July 1828, making it the oldest surviving weekly magazine in the world.

It is owned by Frederick Barclay, who also owns ''The ...

''s review concluded that this "dismal record of intrigue, injustice, incompetence, quarrelling, lying communist propaganda, police spying, illegal imprisonment, filth and disorder" was evidence that the Republic deserved to fall. A mixed review was supplied by V. S. Pritchett who called Orwell naïve about Spain but added that "no one excels him in bringing to the eyes, ears and nostrils the nasty ingredients of fevered situations; and I would recommend him warmly to all who are concerned about the realities of personal experience in a muddled cause".

Notably positive reviews came from Geoffrey Gorer

Geoffrey Edgar Solomon Gorer (26 March 1905 – 24 May 1985) was an English anthropologist and writer, noted for his application of psychoanalytic techniques to anthropology.

Born into a non-practicing Jewish family, he was educated at Charterhou ...

in ''Time and Tide

Time and Tide (usually derived from the proverb ''Time and tide wait for no man'') may refer to:

Music

Albums

* ''Time and Tide'' (Greenslade album), 1975

* ''Time and Tide'' (Basia album), 1987

* ''Time and Tide'' (Battlefield Band album), ...

'', and from Philip Mairet

Philip Mairet (; full name: Philippe Auguste Mairet; 1886–1975) was a British designer, writer and journalist. He had a wide range of interest: crafts, Alfred Adler and psychiatry, and Social Credit. He translated major figures including Jean- ...

in the ''New English Weekly

''The New English Weekly'' was a leading British review of "Public Affairs, Literature and the Arts."

It was founded in April 1932 by Alfred Richard Orage shortly after his return from Paris. One of Britain's most prestigious editors, Orage had ed ...

''. Gorer concluded, "Politically and as literature it is a work of first-class importance". Mairet observed, "It shows us the heart of innocence that lies in revolution; also the miasma of lying that, far more than the cruelty, takes the heart out of it." Franz Borkenau

Franz Borkenau (December 15, 1900 – May 22, 1957) was an Austrian writer. Borkenau was born in Vienna, Austria, the son of a civil servant. As a university student in Leipzig, his main interests were Marxism and psychoanalysis. Borkenau is kno ...

, in a letter to Orwell of June 1938, called the book, together with his own ''The Spanish Cockpit

''The Spanish Cockpit'' is a personal account of the Spanish Civil War written by Franz Borkenau and published in late 1937. It was based on his two wartime visits to Spain in August 1936 and January 1937, visiting Barcelona, Madrid, Toledo, Va ...

'', a complete "picture of the revolutionary phase of the Spanish War".

Hostile notices came from ''The Tablet

''The Tablet'' is a Catholic international weekly review published in London. Brendan Walsh, previously literary editor and then acting editor, was appointed editor in July 2017.

History

''The Tablet'' was launched in 1840 by a Quaker convert ...

'', where a critic wondered why Orwell had not troubled to get to know Fascist fighters and enquire about their motivations, and from ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication i ...

'' and '' The Listener'', "the first misrepresenting what Orwell had said and the latter attacking the POUM, but never mentioning the book".

Later

The book was praised byNoam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American public intellectual: a linguist, philosopher, cognitive scientist, historian, social critic, and political activist. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is ...

in 1969. Raymond Carr

Sir Albert Raymond Maillard Carr (11 April 1919 – 19 April 2015) was an English historian specialising in the history of Spain, Latin America, and Sweden. From 1968 to 1987, he was Warden of St Antony's College, Oxford.

Early life

Carr w ...

praised Orwell in 1971 for being "determined to set down the truth as he saw it."

In his 1971 memoir, Herbert Matthews

Herbert Lionel Matthews (January 10, 1900 – July 30, 1977) was a reporter and editorialist for ''The New York Times'' who, at the age of 57, won widespread attention after revealing that the 30-year-old Fidel Castro was still alive and living i ...

of ''The New York Times'' declared, "The book did more to blacken the Loyalist cause than any work written by enemies of the Second Republic." In 1984 Lawrence and Wishart

Lawrence & Wishart is a British publishing company formerly associated with the Communist Party of Great Britain. It was formed in 1936, through the merger of Martin Lawrence, the Communist Party's press, and Wishart Ltd, a family-owned Left-wing ...

published ''Inside the Myth'', a collection of essays "bringing together a variety of standpoints hostile to Orwell in an obvious attempt to do as much damage to his reputation as possible," per John Newsinger

John Newsinger (born 21 May 1948) is a British historian and academic, who is an emeritus professor of history at Bath Spa University.

Newsinger is a book reviewer for ''Race & Class'' and the ''New Left Review''. He is also author of numerous bo ...

.

Aftermath

Within weeks of leaving Spain, a deposition (discovered in 1989) was presented to the Tribunal for Espionage & High Treason,Valencia

Valencia ( va, València) is the capital of the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, Valencia and the Municipalities of Spain, third-most populated municipality in Spain, with 791,413 inhabitants. It is ...

, charging the Orwells with 'rabid Trotskyism

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

' and being agents of the POUM. The trial of the leaders of the POUM and of Orwell (in his absence) took place in Barcelona, in October and November 1938. Observing events from French Morocco

The French protectorate in Morocco (french: Protectorat français au Maroc; ar, الحماية الفرنسية في المغرب), also known as French Morocco, was the period of French colonial rule in Morocco between 1912 to 1956. The prote ...

, Orwell wrote that they were "only a by-product of the Russian Trotskyist trials and from the start every kind of lie, including flagrant absurdities, has been circulated in the Communist press."

Georges Kopp

Georges Kopp (October 10, 1902 – July 15, 1951) was a Belgian educated engineer and inventor of Russian descent, who volunteered in the fight against Nazism and is best known for his friendship with George Orwell, whom he commanded in the Spani ...

, deemed "quite likely" shot in the book's final chapter, was released in December 1938.

Barcelona fell to Franco's forces on 26 January 1939, and on 1 April 1939, the last of the Republican forces surrendered.

Effect on Orwell

Health

Orwell never knew the source of his tuberculosis, from complications of which he died in 1950. However, in 2018, researchers studying bacteria on his letters announced that there was a "very high probability" that Orwell contracted the disease in a Spanish hospital.Politics

Orwell reflected that he "had ''felt'' what socialism could be like" and, according to biographerGordon Bowker

Gordon Bowker is an American entrepreneur. He began as a writer and went on to co-found Starbucks with Jerry Baldwin and Zev Siegl. He was later a co-owner of Peet's Coffee & Tea and Redhook Ale Brewery.

Biography

Following the death of his ...

, "Orwell never did abandon his socialism: if anything, his Spanish experience strengthened it." In a letter to Cyril Connolly

Cyril Vernon Connolly CBE (10 September 1903 – 26 November 1974) was an English literary critic and writer. He was the editor of the influential literary magazine ''Horizon'' (1940–49) and wrote '' Enemies of Promise'' (1938), which combin ...

, written on 8 June 1937, Orwell said, "At last really believe in Socialism, which I never did before". A decade later he wrote: "Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, ''against'' totalitarianism and ''for'' democratic Socialism, as I understand it."

Orwell's experiences, culminating in his and his wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy

Eileen Maud Blair (née O'Shaughnessy, 25 September 1905 – 29 March 1945) was the first wife of George Orwell (Eric Arthur Blair). During World War II, she worked for the Censorship Department of the Ministry of Information in London and ...

's narrow escape from the communist purges in Barcelona in June 1937, greatly increased his sympathy for the POUM and, while not affecting his moral and political commitment to socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

, made him a lifelong anti-Stalinist.

After reviewing Koestler's bestselling ''Darkness at Noon

''Darkness at Noon'' (german: link=no, Sonnenfinsternis) is a novel by Hungarian-born novelist Arthur Koestler, first published in 1940. His best known work, it is the tale of Rubashov, an Old Bolshevik who is arrested, imprisoned, and tried f ...

'', Orwell decided that fiction was the best way to describe totalitarianism. He soon wrote ''Animal Farm

''Animal Farm'' is a beast fable, in the form of satirical allegorical novella, by George Orwell, first published in England on 17 August 1945. It tells the story of a group of farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, hoping to c ...

'', "his scintillating 1944 satire on Stalinism".Alt URLWorks inspired by the book

Orwell himself went on to write a poem about the Italian militiaman he described in the book's opening pages. The poem was included in Orwell's 1942 essay "Looking Back on the Spanish War", published in '' New Road'' in 1943. The closing phrase of the poem, "No bomb that ever burst shatters the crystal spirit", was later taken by

Orwell himself went on to write a poem about the Italian militiaman he described in the book's opening pages. The poem was included in Orwell's 1942 essay "Looking Back on the Spanish War", published in '' New Road'' in 1943. The closing phrase of the poem, "No bomb that ever burst shatters the crystal spirit", was later taken by George Woodcock

George Woodcock (; May 8, 1912 – January 28, 1995) was a Canadian writer of political biography and history, an anarchist thinker, a philosopher, an essayist and literary critic. He was also a poet and published several volumes of travel wri ...

for the title of his Governor General's Award

The Governor General's Awards are a collection of annual awards presented by the Governor General of Canada, recognizing distinction in numerous academic, artistic, and social fields.

The first award was conceived and inaugurated in 1937 by the ...

-winning critical study of Orwell and his work, ''The Crystal Spirit'' (1966).Hiebert, Matt"In Canada and Abroad: The Diverse Publishing Career of George Woodcock".

Retrieved 19 August 2013. In 1995

Ken Loach

Kenneth Charles Loach (born 17 June 1936) is a British film director and screenwriter. His socially critical directing style and socialist ideals are evident in his film treatment of social issues such as poverty (''Poor Cow'', 1967), homelessne ...

released the film '' Land and Freedom'', heavily inspired by ''Homage to Catalonia''.

''Homage to Catalonia'' influenced Rebecca Solnit

Rebecca Solnit (born 1961) is an American writer. She has written on a variety of subjects, including feminism, the environment, politics, place, and art.

Early life and education

Solnit was born in 1961 in Bridgeport, Connecticut, to a Jewish fa ...

's second book, '' Savage Dreams''.

See also

*Anarchist Catalonia

Revolutionary Catalonia (21 July 1936 – 10 February 1939) was the part of Catalonia (autonomous region in northeast Spain) controlled by various anarchist, communist, and socialist trade unions, parties, and militias of the Spanish Civil W ...

* Bibliography of George Orwell

The bibliography of George Orwell includes journalism, essays, novels, and non-fiction books written by the British writer Eric Blair (1903–1950), either under his own name or, more usually, under his pen name George Orwell. Orwell was a proli ...

* ILP Contingent described in ''Homage to Catalonia''

* ''Les grands cimetières sous la lune

''Les Grands Cimetières sous la Lune'' (1938; English: literally, ''The Great Cemeteries Under the Moon'', English title when published; ''A Diary of My Times'') is a book by novelist Georges Bernanos which fiercely condemns the atrocities carried ...

''

* Spanish Revolution

* William Herrick 'an American Orwell', also disillusioned by Stalinism in Spain

References

External links

*''Homage to Catalonia''

– Searchable, indexed etext.

Complete book with publication data and search option.

''Homage to Catalonia''

Complete book as plain text.

– an essay written 6 years later. * {{DEFAULTSORT:Homage To Catalonia 1938 non-fiction books Anarchism in Spain Barcelona in popular culture Books about anarchism Books by George Orwell History of Catalonia Political autobiographies POUM Secker & Warburg books Spanish Civil War books Works about Stalinism