Name and general perception

The Empire was considered by the Roman Catholic Church to be the only legal successor of the Roman Empire during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. Since Charlemagne, the realm was merely referred to as the ''Roman Empire''. The term ''sacrum'' ("holy", in the sense of "consecrated") in connection with the medieval Roman Empire was used beginning in 1157 under Frederick I Barbarossa ("Holy Empire"): the term was added to reflect Frederick's ambition to dominate Italy and the

The Empire was considered by the Roman Catholic Church to be the only legal successor of the Roman Empire during the Middle Ages and the early modern period. Since Charlemagne, the realm was merely referred to as the ''Roman Empire''. The term ''sacrum'' ("holy", in the sense of "consecrated") in connection with the medieval Roman Empire was used beginning in 1157 under Frederick I Barbarossa ("Holy Empire"): the term was added to reflect Frederick's ambition to dominate Italy and the Consequently, Henry I and Otto I, did not begin ''de novo'' to develop a military, administrative, and intellectual infrastructure for their kingdom and empire. They built upon the existing structures that they had inherited from their Carolingian predecessors. An argument for continuity should not, however, be confused with a claim for stasis. The Ottonians, just like their Carolingian predecessors, developed and refined their material, cultural, intellectual, and administrative inheritance in ways that fit their own time. It was the success of the Ottonians in molding the raw materials bequeathed to them into a formidable military machine that made possible the establishment of Germany as the preeminent kingdom in Europe from the tenth through the mid-thirteenth century ..the Carolingians built upon the military organization that they had inherited from their Merovingian and ultimately late-Roman predecessors."Bachrach argues that the Ottonian empire was hardly an archaic kingdom of primitive Germans, maintained by personal relationships only and driven by the desire of the magnates to plunder and divide the rewards among themselves (as argued by Timothy Reuter), but instead, notable for their abilities to amass sophisticated economic, administrative, educational and cultural resources that they used to serve their enormous war machine. Until the end of the 15th century, the empire was in theory composed of three major blocks – Italy,

History

Early Middle Ages

Carolingian period

Post-Carolingian Eastern Frankish Kingdom

Around 900, East Francia's autonomous

High Middle Ages

Investiture controversy

Kings often employed bishops in administrative affairs and often determined who would be appointed to ecclesiastical offices. In the wake of the Cluniac Reforms, this involvement was increasingly seen as inappropriate by the Papacy. The reform-minded Pope Gregory VII was determined to oppose such practices, which led to the Investiture Controversy with Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV (r. 1056–1106), the King of the Romans and Holy Roman Emperor. Henry IV repudiated the Pope's interference and persuaded his bishops to excommunicate the Pope, whom he famously addressed by his born name "Hildebrand", rather than his regnal name "Pope Gregory VII". The Pope, in turn, excommunicated the king, declared him deposed, and dissolved the oaths of loyalty made to Henry. The king found himself with almost no political support and was forced to make the famous Walk to Canossa in 1077, by which he achieved a lifting of the excommunication at the price of humiliation. Meanwhile, the German princes had elected another king, Rudolf of Swabia.

Henry managed to defeat Rudolf, but was subsequently confronted with more uprisings, renewed excommunication, and even the rebellion of his sons. After his death, his second son, Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, Henry V, reached an agreement with the Pope and the bishops in the 1122 Concordat of Worms. The political power of the Empire was maintained, but the conflict had demonstrated the limits of the ruler's power, especially in regard to the Church, and it robbed the king of the sacral status he had previously enjoyed. The Pope and the German princes had surfaced as major players in the political system of the empire.

Henry IV repudiated the Pope's interference and persuaded his bishops to excommunicate the Pope, whom he famously addressed by his born name "Hildebrand", rather than his regnal name "Pope Gregory VII". The Pope, in turn, excommunicated the king, declared him deposed, and dissolved the oaths of loyalty made to Henry. The king found himself with almost no political support and was forced to make the famous Walk to Canossa in 1077, by which he achieved a lifting of the excommunication at the price of humiliation. Meanwhile, the German princes had elected another king, Rudolf of Swabia.

Henry managed to defeat Rudolf, but was subsequently confronted with more uprisings, renewed excommunication, and even the rebellion of his sons. After his death, his second son, Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor, Henry V, reached an agreement with the Pope and the bishops in the 1122 Concordat of Worms. The political power of the Empire was maintained, but the conflict had demonstrated the limits of the ruler's power, especially in regard to the Church, and it robbed the king of the sacral status he had previously enjoyed. The Pope and the German princes had surfaced as major players in the political system of the empire.

Ostsiedlung

As the result of Ostsiedlung, less-populated regions of Central Europe (i.e. sparsely populated border areas in present-day Poland and the Czech Republic) received a significant number of German speakers. Silesia became part of the Holy Roman Empire as the result of the local Piast dynasty, Piast dukes' push for autonomy from the Polish Crown. From the late 12th century, the Duchy of Pomerania was under the suzerainty of the Holy Roman Empire and the conquests of the Teutonic Order made that region German-speaking.Hohenstaufen dynasty

Kingdom of Bohemia

Interregnum

After the death of Frederick II in 1250, the German kingdom was divided between his son Conrad IV of Germany, Conrad IV (died 1254) and the Anti-king#Germany, anti-king, Count William II of Holland, William of Holland (died 1256). Conrad's death was followed by the Interregnum, during which no king could achieve universal recognition, allowing the princes to consolidate their holdings and become even more independent as rulers. After 1257, the crown was contested between Richard of Cornwall, who was supported by the Guelphs and Ghibellines, Guelph party, and Alfonso X of Castile, who was recognized by the Hohenstaufen party but never set foot on German soil. After Richard's death in 1273, Rudolf I of Germany, a minor pro-Hohenstaufen count, was elected. He was the first of the Habsburgs to hold a royal title, but he was never crowned emperor. After Rudolf's death in 1291, Adolf, King of the Romans, Adolf and Albert I of Germany, Albert were two further weak kings who were never crowned emperor. Albert was assassinated in 1308. Almost immediately, King Philip IV of France began aggressively seeking support for his brother, Charles, Count of Valois, Charles of Valois, to be elected the next King of the Romans. Philip thought he had the backing of the French Pope, Pope Clement V, Clement V (established at Avignon in 1309), and that his prospects of bringing the empire into the orbit of the French royal house were good. He lavishly spread French money in the hope of bribing the German electors. Although Charles of Valois had the backing of pro-French Heinrich II of Virneburg, Henry, Archbishop of Cologne, many were not keen to see an expansion of French power, least of all Clement V. The principal rival to Charles appeared to be Rudolf II, Count Palatine of the Rhine, Rudolf, the Count Palatine. But the electors, the great territorial magnates who had lived without a crowned emperor for decades, were unhappy with both Charles and Rudolf. Instead Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor, Henry, Count of Luxembourg, with the aid of his brother, Baldwin, Archbishop of Trier, was elected as Henry VII with six votes at Frankfurt on 27 November 1308. Though a vassal of king Philip, Henry was bound by few national ties, and thus suitable as a compromise candidate. Henry VII was crowned king at Aachen on 6 January 1309, and emperor by Pope Clement V on 29 June 1312 in Rome, ending the interregnum.Changes in political structure

During the 13th century, a general structural change in how land was administered prepared the shift of political power towards the rising bourgeoisie at the expense of the aristocratic feudalism that would characterize the Late Middle Ages. The rise of the Free imperial city, cities and the emergence of the new Burgher (title), burgher class eroded the societal, legal and economic order of feudalism. Instead of personal duties, money increasingly became the common means to represent economic value in agriculture.

Peasants were increasingly required to pay tribute to their landlords. The concept of "property" began to replace more ancient forms of jurisdiction, although they were still very much tied together. In the territories (not at the level of the Empire), power became increasingly bundled: whoever owned the land had jurisdiction, from which other powers derived. However, that jurisdiction at the time did not include legislation, which was virtually non-existent until well into the 15th century. Court practice heavily relied on traditional customs or rules described as customary.

During this time, territories began to transform into the predecessors of modern states. The process varied greatly among the various lands and was most advanced in those territories that were almost identical to the lands of the old Germanic tribes, ''e.g.'', Bavaria. It was slower in those scattered territories that were founded through imperial privileges.

In the 12th century the Hanseatic League established itself as a commercial and defensive alliance of the merchant guilds of towns and cities in the empire and all over northern and central Europe. It dominated marine trade in the Baltic Sea, the North Sea and along the connected navigable rivers. Each of the affiliated cities retained the legal system of its sovereign and, with the exception of the Free imperial city, Free imperial cities, had only a limited degree of political autonomy. By the late 14th century, the powerful league enforced its interests with military means, if necessary. This culminated in Second Danish-Hanseatic War, a war with the sovereign Kingdom of Denmark from 1361 to 1370. The league declined after 1450.

During the 13th century, a general structural change in how land was administered prepared the shift of political power towards the rising bourgeoisie at the expense of the aristocratic feudalism that would characterize the Late Middle Ages. The rise of the Free imperial city, cities and the emergence of the new Burgher (title), burgher class eroded the societal, legal and economic order of feudalism. Instead of personal duties, money increasingly became the common means to represent economic value in agriculture.

Peasants were increasingly required to pay tribute to their landlords. The concept of "property" began to replace more ancient forms of jurisdiction, although they were still very much tied together. In the territories (not at the level of the Empire), power became increasingly bundled: whoever owned the land had jurisdiction, from which other powers derived. However, that jurisdiction at the time did not include legislation, which was virtually non-existent until well into the 15th century. Court practice heavily relied on traditional customs or rules described as customary.

During this time, territories began to transform into the predecessors of modern states. The process varied greatly among the various lands and was most advanced in those territories that were almost identical to the lands of the old Germanic tribes, ''e.g.'', Bavaria. It was slower in those scattered territories that were founded through imperial privileges.

In the 12th century the Hanseatic League established itself as a commercial and defensive alliance of the merchant guilds of towns and cities in the empire and all over northern and central Europe. It dominated marine trade in the Baltic Sea, the North Sea and along the connected navigable rivers. Each of the affiliated cities retained the legal system of its sovereign and, with the exception of the Free imperial city, Free imperial cities, had only a limited degree of political autonomy. By the late 14th century, the powerful league enforced its interests with military means, if necessary. This culminated in Second Danish-Hanseatic War, a war with the sovereign Kingdom of Denmark from 1361 to 1370. The league declined after 1450.

Late Middle Ages

Rise of the territories after the Hohenstaufens

The difficulties in electing the king eventually led to the emergence of a fixed college of prince-electors (''Kurfürsten''), whose composition and procedures were set forth in the Golden Bull of 1356, issued by Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV (reigned 1355–1378, King of the Romans since 1346), which remained valid until 1806. This development probably best symbolizes the emerging duality between emperor and realm (''Kaiser und Reich''), which were no longer considered identical. The Golden Bull also set forth the system for election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The emperor now was to be elected by a majority rather than by consent of all seven electors. For electors the title became hereditary, and they were given the right to mint coins and to exercise jurisdiction. Also it was recommended that their sons learn the imperial languages – German language, German, Latin, Italian language, Italian, and Czech language, Czech. The decision by Charles IV is the subject of debates: on one hand, it helped to restore peace in the lands of the Empire, that had been engulfed in civil conflicts after the end of the Hohenstaufen era; on the other hand, the "blow to central authority was unmistakable". Thomas Brady Jr. opines that Charles IV's intention was to end contested royal elections (from the Luxembourghs' perspective, they also had the advantage that the King of Bohemia had a permanent and preeminent status as one of the Electors himself). At the same time, he built up Bohemia as the Luxembourghs' core land of the Empire and their dynastic base. His reign in Bohemia is often considered the land's Golden Age. According to Brady Jr. though, under all the glitter, one problem arose: the government showed an inability to deal with the German immigrant waves into Bohemia, thus leading to religious tensions and persecutions. The imperial project of the Luxembourgh halted under Charles's son Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia, Wenceslaus (reigned 1378–1419 as King of Bohemia, 1376–1400 as King of the Romans), who also faced opposition from 150 local baronial families.

The shift in power away from the emperor is also revealed in the way the post-Hohenstaufen kings attempted to sustain their power. Earlier, the Empire's strength (and finances) greatly relied on the Empire's own lands, the so-called ''Reichsgut'', which always belonged to the king of the day and included many Imperial Cities. After the 13th century, the relevance of the ''Reichsgut'' faded, even though some parts of it did remain until the Empire's end in 1806. Instead, the ''Reichsgut'' was increasingly pawned to local dukes, sometimes to raise money for the Empire, but more frequently to reward faithful duty or as an attempt to establish control over the dukes. The direct governance of the ''Reichsgut'' no longer matched the needs of either the king or the dukes.

The kings beginning with Rudolf I of Germany increasingly relied on the lands of their respective dynasties to support their power. In contrast with the ''Reichsgut'', which was mostly scattered and difficult to administer, these territories were relatively compact and thus easier to control. In 1282, Rudolf I thus lent Austria and Styria (duchy), Styria to his own sons. In 1312, Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg was crowned as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Frederick II. After him all kings and emperors relied on the lands of their own family (''Hausmacht''): Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Louis IV of Wittelsbach (king 1314, emperor 1328–47) relied on his lands in Bavaria; Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV of Luxembourg, the grandson of Henry VII, drew strength from his own lands in Bohemia. It was thus increasingly in the king's own interest to strengthen the power of the territories, since the king profited from such a benefit in his own lands as well.

The difficulties in electing the king eventually led to the emergence of a fixed college of prince-electors (''Kurfürsten''), whose composition and procedures were set forth in the Golden Bull of 1356, issued by Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV (reigned 1355–1378, King of the Romans since 1346), which remained valid until 1806. This development probably best symbolizes the emerging duality between emperor and realm (''Kaiser und Reich''), which were no longer considered identical. The Golden Bull also set forth the system for election of the Holy Roman Emperor. The emperor now was to be elected by a majority rather than by consent of all seven electors. For electors the title became hereditary, and they were given the right to mint coins and to exercise jurisdiction. Also it was recommended that their sons learn the imperial languages – German language, German, Latin, Italian language, Italian, and Czech language, Czech. The decision by Charles IV is the subject of debates: on one hand, it helped to restore peace in the lands of the Empire, that had been engulfed in civil conflicts after the end of the Hohenstaufen era; on the other hand, the "blow to central authority was unmistakable". Thomas Brady Jr. opines that Charles IV's intention was to end contested royal elections (from the Luxembourghs' perspective, they also had the advantage that the King of Bohemia had a permanent and preeminent status as one of the Electors himself). At the same time, he built up Bohemia as the Luxembourghs' core land of the Empire and their dynastic base. His reign in Bohemia is often considered the land's Golden Age. According to Brady Jr. though, under all the glitter, one problem arose: the government showed an inability to deal with the German immigrant waves into Bohemia, thus leading to religious tensions and persecutions. The imperial project of the Luxembourgh halted under Charles's son Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia, Wenceslaus (reigned 1378–1419 as King of Bohemia, 1376–1400 as King of the Romans), who also faced opposition from 150 local baronial families.

The shift in power away from the emperor is also revealed in the way the post-Hohenstaufen kings attempted to sustain their power. Earlier, the Empire's strength (and finances) greatly relied on the Empire's own lands, the so-called ''Reichsgut'', which always belonged to the king of the day and included many Imperial Cities. After the 13th century, the relevance of the ''Reichsgut'' faded, even though some parts of it did remain until the Empire's end in 1806. Instead, the ''Reichsgut'' was increasingly pawned to local dukes, sometimes to raise money for the Empire, but more frequently to reward faithful duty or as an attempt to establish control over the dukes. The direct governance of the ''Reichsgut'' no longer matched the needs of either the king or the dukes.

The kings beginning with Rudolf I of Germany increasingly relied on the lands of their respective dynasties to support their power. In contrast with the ''Reichsgut'', which was mostly scattered and difficult to administer, these territories were relatively compact and thus easier to control. In 1282, Rudolf I thus lent Austria and Styria (duchy), Styria to his own sons. In 1312, Henry VII, Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VII of the House of Luxembourg was crowned as the first Holy Roman Emperor since Frederick II. After him all kings and emperors relied on the lands of their own family (''Hausmacht''): Louis IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Louis IV of Wittelsbach (king 1314, emperor 1328–47) relied on his lands in Bavaria; Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV of Luxembourg, the grandson of Henry VII, drew strength from his own lands in Bohemia. It was thus increasingly in the king's own interest to strengthen the power of the territories, since the king profited from such a benefit in his own lands as well.

Imperial Reform

The "constitution" of the Empire still remained largely unsettled at the beginning of the 15th century. Feuds often happened between local rulers. The "Robber baron (feudalism), robber baron" (''Raubritter'') became a social factor. Simultaneously, the Catholic Church experienced crises of its own, with wide-reaching effects in the Empire. The conflict between several papal claimants (two anti-popes and the "legitimate" Papacy, Pope) ended only with the Council of Constance (1414–1418); after 1419 the Papacy directed much of its energy to suppressing the Hussites. The medieval idea of unifying all Christendom into a single political entity, with the Church and the Empire as its leading institutions, began to decline. With these drastic changes, much discussion emerged in the 15th century about the Empire itself. Rules from the past no longer adequately described the structure of the time, and a reinforcement of earlier ''Landfrieden'' was urgently needed. The vision for a simultaneous reform of the Empire and the Church on a central level began with Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund (reigned 1433–1437, King of the Romans since 1411), who, according to historian Thomas Brady Jr., "possessed a breadth of vision and a sense of grandeur unseen in a German monarch since the thirteenth century". But external difficulties, self-inflicted mistakes and the extinction of the Luxembourg male line made this vision unfulfilled. Frederick III had been very careful regarding the reform movement in the empire. For most of his reign, he considered reform as a threat to his imperial prerogatives. He avoided direct confrontations, which might lead to humiliation if the princes refused to give way. After 1440, the reform of the Empire and Church was sustained and led by local and regional powers, particularly the territorial princes. In his last years, however, there was more on pressure on taking action from a higher level. Berthold von Henneberg, the Archbishop of Mainz, who spoke on behalf of reform-minded princes (who wanted to reform the Empire without strengthening the imperial hand), capitalized on Frederick's desire to secure the imperial election for Maximilian. Thus, in his last years, he presided over the initial phase of Imperial Reform, which would mainly unfold under his son Maximilian. Maximilian himself was more open to reform, although naturally he also wanted to preserve and enhance imperial prerogatives. After Frederick retired to Linz in 1488, as a compromise, Maximilian acted as mediator between the princes and his father. When he attained sole rule after Frederick's death, he would continue this policy of brokerage, acting as the impartial judge between options suggested by the princes.= Creation of institutions

= Major measures for the Reform was launched at the 1495 Reichstag at Worms, Germany, Worms. A new organ was introduced, the ''Reichskammergericht'', that was to be largely independent from the Emperor. A new tax was launched to finance it, the ''Gemeine Pfennig'', although this would only be collected under Charles V and Ferdinand I, and not fully.

To create a rival for the ''Reichskammergericht'', in 1497 Maximilian establish the ''Aulic Council, Reichshofrat'', which had its seat in Vienna. During Maximilian's reign, this council was not popular though. In the long run, the two Courts functioned in parallel, sometimes overlapping.

In 1500, Maximilian agreed to establish an organ called the ''Reichsregiment'' (central imperial government, consisting of twenty members including the Electors, with the Emperor or his representative as its chairman), first organized in 1501 in Nuremberg. But Maximilian resented the new organization, while the Estates failed to support it. The new organ proved politically weak, and its power returned to Maximilian in 1502.

The most important governmental changes targeted the heart of the regime: the chancery. Early in Maximilian's reign, the Court Chancery at Innsbruck competed with the Imperial Chancery (which was under the elector-archbishop of Mainz, the senior Imperial chancellor). By referring the political matters in Tyrol, Austria as well as Imperial problems to the Court Chancery, Maximilian gradually centralized its authority. The two chanceries became combined in 1502. In 1496, the emperor created a general treasury (''Hofkammer'') in Innsbruck, which became responsible for all the hereditary lands. The chamber of accounts (''Raitkammer'') at Vienna was made subordinate to this body. Under :de:Paul von Liechtenstein-Kastelkorn, Paul von Liechtenstein, the ''Hofkammer'' was entrusted with not only hereditary lands' affairs, but Maximilian's affairs as the German king too.

A new organ was introduced, the ''Reichskammergericht'', that was to be largely independent from the Emperor. A new tax was launched to finance it, the ''Gemeine Pfennig'', although this would only be collected under Charles V and Ferdinand I, and not fully.

To create a rival for the ''Reichskammergericht'', in 1497 Maximilian establish the ''Aulic Council, Reichshofrat'', which had its seat in Vienna. During Maximilian's reign, this council was not popular though. In the long run, the two Courts functioned in parallel, sometimes overlapping.

In 1500, Maximilian agreed to establish an organ called the ''Reichsregiment'' (central imperial government, consisting of twenty members including the Electors, with the Emperor or his representative as its chairman), first organized in 1501 in Nuremberg. But Maximilian resented the new organization, while the Estates failed to support it. The new organ proved politically weak, and its power returned to Maximilian in 1502.

The most important governmental changes targeted the heart of the regime: the chancery. Early in Maximilian's reign, the Court Chancery at Innsbruck competed with the Imperial Chancery (which was under the elector-archbishop of Mainz, the senior Imperial chancellor). By referring the political matters in Tyrol, Austria as well as Imperial problems to the Court Chancery, Maximilian gradually centralized its authority. The two chanceries became combined in 1502. In 1496, the emperor created a general treasury (''Hofkammer'') in Innsbruck, which became responsible for all the hereditary lands. The chamber of accounts (''Raitkammer'') at Vienna was made subordinate to this body. Under :de:Paul von Liechtenstein-Kastelkorn, Paul von Liechtenstein, the ''Hofkammer'' was entrusted with not only hereditary lands' affairs, but Maximilian's affairs as the German king too.

= Reception of Roman Law

= At the 1495 Diet of Worms, the Reception of Roman Law was accelerated and formalized. The Roman Law was made binding in German courts, except in the case it was contrary to local statutes. In practice, it became the basic law throughout Germany, displacing Germanic local law to a large extent, although Germanic law was still operative at the lower courts. Other than the desire to achieve legal unity and other factors, the adoption also highlighted the continuity between the Ancient Roman empire and the Holy Roman Empire. To realize his resolve to reform and unify the legal system, the emperor frequently intervened personally in matters of local legal matters, overriding local charters and customs. This practice was often met with irony and scorn from local councils, who wanted to protect local codes.

The legal reform seriously weakened the ancient Vehmic court (''Vehmgericht'', or Secret Tribunal of Westphalia, traditionally held to be instituted by

At the 1495 Diet of Worms, the Reception of Roman Law was accelerated and formalized. The Roman Law was made binding in German courts, except in the case it was contrary to local statutes. In practice, it became the basic law throughout Germany, displacing Germanic local law to a large extent, although Germanic law was still operative at the lower courts. Other than the desire to achieve legal unity and other factors, the adoption also highlighted the continuity between the Ancient Roman empire and the Holy Roman Empire. To realize his resolve to reform and unify the legal system, the emperor frequently intervened personally in matters of local legal matters, overriding local charters and customs. This practice was often met with irony and scorn from local councils, who wanted to protect local codes.

The legal reform seriously weakened the ancient Vehmic court (''Vehmgericht'', or Secret Tribunal of Westphalia, traditionally held to be instituted by =National political culture

= Maximilian and Charles V (despite the fact both emperors were internationalists personally) were the first who mobilized the rhetoric of the Nation, firmly identified with the Reich by the contemporary humanists. With encouragement from Maximilian and his humanists, iconic spiritual figures were reintroduced or became notable. The humanists rediscovered the work ''Germania (book), Germania'', written by Tacitus. According to Peter H. Wilson, the female figure of Germania (personification), Germania was reinvented by the emperor as the virtuous pacific Mother of Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Whaley further suggests that, despite the later religious divide, "patriotic motifs developed during Maximilian's reign, both by Maximilian himself and by the humanist writers who responded to him, formed the core of a national political culture."

Maximilian's reign also witnessed the gradual emergence of the German common language, with the notable roles of the imperial chancery and the chancery of the Wettin Elector Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise. The development of the printing industry together with the emergence of the postal system (Kaiserliche Reichspost, the first modern one in the world), initiated by Maximilian himself with contribution from Frederick III and Charles the Bold, led to a revolution in communication and allowed ideas to spread. Unlike the situation in more centralized countries, the decentralized nature of the Empire made censorship difficult.

Terence McIntosh comments that the expansionist, aggressive policy pursued by Maximilian I and Charles V at the inception of the early modern German nation (although not to further the aims specific to the German nation per se), relying on German manpower as well as utilizing fearsome Landsknechte and mercenaries, would affect the way neighbours viewed the German polity, although in the longue durée, Germany tended to be at peace.

Maximilian and Charles V (despite the fact both emperors were internationalists personally) were the first who mobilized the rhetoric of the Nation, firmly identified with the Reich by the contemporary humanists. With encouragement from Maximilian and his humanists, iconic spiritual figures were reintroduced or became notable. The humanists rediscovered the work ''Germania (book), Germania'', written by Tacitus. According to Peter H. Wilson, the female figure of Germania (personification), Germania was reinvented by the emperor as the virtuous pacific Mother of Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. Whaley further suggests that, despite the later religious divide, "patriotic motifs developed during Maximilian's reign, both by Maximilian himself and by the humanist writers who responded to him, formed the core of a national political culture."

Maximilian's reign also witnessed the gradual emergence of the German common language, with the notable roles of the imperial chancery and the chancery of the Wettin Elector Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise. The development of the printing industry together with the emergence of the postal system (Kaiserliche Reichspost, the first modern one in the world), initiated by Maximilian himself with contribution from Frederick III and Charles the Bold, led to a revolution in communication and allowed ideas to spread. Unlike the situation in more centralized countries, the decentralized nature of the Empire made censorship difficult.

Terence McIntosh comments that the expansionist, aggressive policy pursued by Maximilian I and Charles V at the inception of the early modern German nation (although not to further the aims specific to the German nation per se), relying on German manpower as well as utilizing fearsome Landsknechte and mercenaries, would affect the way neighbours viewed the German polity, although in the longue durée, Germany tended to be at peace.

=Imperial power

= Maximilian was "the first Holy Roman Emperor in 250 years who ruled as well as reigned". In the early 1500s, he was true master of the Empire, although his power weakened during the last decade before his death. Whaley notes that, despite struggles, what emerged at the end of Maximilian's rule was a strengthened monarchy and not an oligarchy of princes. Benjamin Curtis opines that while Maximilian was not able to fully create a common government for his lands (although the chancellery and court council were able to coordinate affairs across the realms), he strengthened key administrative functions in Austria and created central offices to deal with financial, political and judicial matters – these offices replaced the feudal system and became representative of a more modern system that was administered by professionalized officials. After two decades of reforms, the emperor retained his position as first among equals, while the empire gained common institutions through which the emperor shared power with the estates. By the early sixteenth century, the Habsburg rulers had become the most powerful in Europe, but their strength relied on their composite monarchy as a whole, and not only the Holy Roman Empire (see also: Empire of Charles V). Maximilian had seriously considered combining the Burgundian lands (inherited from his wife Mary of Burgundy) with his Austrian lands to form a powerful core (while also extending towards the east). After the unexpected addition of Spain to the Habsburg Empire, at one point he intended to leave Austria (raised to a kingdom) to his younger grandson Ferdinand. Charles V later gave most of the Burgundian lands to the Spanish branch.Early capitalism

While particularism prevented the centralization of the Empire, it gave rise to early developments of capitalism. In Italian and Hanseatic cities like Genoa and Venice, Hamburg and Lübeck, warrior-merchants appeared and pioneered raiding-and-traiding maritime empires. These practices declined before 1500, but they managed to spread to the maritime periphery in Portugal, Spain, the Netherlands and England, where they "provoked emulation in grander, oceanic scale". William Thompson agrees with M.N.Pearson that this distinctively European phenomenon happened because in the Italian and Hanseatic cities which lacked resources and were "small in size and population", the rulers (whose social status was not much higher than the merchants) had to pay attention to trade. Thus the warrior-merchants gained the state's coercive powers, which they could not gain in Mughal or other Asian realms – whose rulers had few incentives to help the merchant class, as they controlled considerable resources and their revenue was land-bound. In the 1450s, the economic development in Southern Germany gave rise to banking empires, cartels and monopolies in cities such as Ulm, Regensburg and Augsburg. Augsburg in particular, associated with the reputation of the Fugger, Welser and Baumgartner families, is considered the capital city of early capitalism. Augsburg benefitted majorly from the establishment and expansion of the Kaiserliche Reichspost in the late 15th and early 16th century. Even when the Habsburg empire began to extend to other parts of Europe, Maximilian's loyalty to Augsburg, where he conducted a lot of his endeavours, meant that the imperial city became "the dominant centre of early capitalism" of the sixteenth century, and "the location of the most important post office within the Holy Roman Empire". From Maximilian's time, as the "terminuses of the first transcontinental post lines" began to shift from Innsbruck to Venice and from Brussels to Antwerp, in these cities, the communication system and the news market started to converge. As the Fuggers as well as other trading companies based their most important branches in these cities, these traders gained access to these systems as well. The 1557, 1575 and 1607 bankruptcies of the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs though damaged the Fuggers substantially. Moreover, "Discovery of water routes to India and the New World shifted the focus of European economic development from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic - emphasis shifted from Venice and Genoa to Lisbon and Antwerp. Eventually American mineral developments reduced the importance of Hungarian and Tyrolean mineral wealth. The nexus of the European continent remained landlocked until the time of expedient land conveyances in the form of primarily rail and canal systems, which were limited in growth potential; in the new continent, on the other hand, there were ports in abundance to release the plentiful goods obtained from those new lands." The economic pinnacles achieved in Germany in the period between 1450 and 1550 would never be seen again until the end of the nineteenth century. In the Netherlands part of the empire, financial centres evolved together with markets of commodities. Topographical development in the fifteenth century made Antwerp a port city. Boosted by the privileges it received as a loyal city after the Flemish revolts against Maximilian of Austria, Flemish revolts against Maximilian, it became the leading seaport city in Northern Europe and served as "the conduit for a remarkable 40% of world trade". Conflicts with the Habsburg-Spanish government in 1576 and 1585 though made merchants relocate to Amsterdam, which eventually replaced it as the leading port city.Protestant Reformation and Renaissance

In 1516, Ferdinand II of Aragon, grandfather of the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, died. Charles initiated his reign in Castile and Aragon, a union which evolved into Spanish Crown, Spain, in conjunction with his mother Joanna of Castile.

In 1519, already reigning as ''Carlos I'' in Spain, Charles took up the imperial title as ''Karl V''. The Holy Roman Empire would end up going to a more junior branch of the Habsburgs in the person of Charles's brother Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand, while the senior branch continued to rule in Spain and the Burgundian inheritance in the person of Charles's son, Philip II of Spain. Many factors contribute to this result. For James D.Tracy, it was the polycentric character of the European civilization that made it hard to maintain "a dynasty whose territories bestrode the continent from the Low Countries to Sicily and from Spain to Hungary—not to mention Spain's overseas possessions". Others point out the religious tensions, fiscal problems and obstruction from external forces including France and the Ottomans. On a more personal level, Charles failed to persuade the German princes to support his son Philip, whose "awkward and withdrawn character and lack of German language skills doomed this enterprise to failure".

Before Charles's reign in the Holy Roman Empire began, in 1517, Martin Luther launched what would later be known as the Protestant Reformation, Reformation. The empire then became divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities – Strasbourg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg – becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Roman Catholic, Catholic.

At the beginning of Charles's reign, another ''Reichsregiment'' was set up again (1522), although Charles declared that he would only tolerate it in his absence and its chairman had to be a representative of his. Charles V was absent in Germany from 1521 to 1530. Similar to the one set up in the early 1500s, the ''Reichsregiment'' failed to create a federal authority independent of the emperor, due to the unsteady participation and differences between princes. Charles V defeated the Protestant princes in 1547 in the Schmalkaldic War, but the momentum was lost and the Protestant estates were able to survive politically despite military defeat. In the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, Charles V, through his brother Ferdinand, officially recognized the right of rulers to choose Catholicism or Lutheranism (Zwinglians, Calvinists and radicals were not included). In 1555, Pope Paul IV, Paul IV was elected pope and took the side of France, whereupon an exhausted Charles finally gave up his hopes of a world Christian empire.

In 1516, Ferdinand II of Aragon, grandfather of the future Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, died. Charles initiated his reign in Castile and Aragon, a union which evolved into Spanish Crown, Spain, in conjunction with his mother Joanna of Castile.

In 1519, already reigning as ''Carlos I'' in Spain, Charles took up the imperial title as ''Karl V''. The Holy Roman Empire would end up going to a more junior branch of the Habsburgs in the person of Charles's brother Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand, while the senior branch continued to rule in Spain and the Burgundian inheritance in the person of Charles's son, Philip II of Spain. Many factors contribute to this result. For James D.Tracy, it was the polycentric character of the European civilization that made it hard to maintain "a dynasty whose territories bestrode the continent from the Low Countries to Sicily and from Spain to Hungary—not to mention Spain's overseas possessions". Others point out the religious tensions, fiscal problems and obstruction from external forces including France and the Ottomans. On a more personal level, Charles failed to persuade the German princes to support his son Philip, whose "awkward and withdrawn character and lack of German language skills doomed this enterprise to failure".

Before Charles's reign in the Holy Roman Empire began, in 1517, Martin Luther launched what would later be known as the Protestant Reformation, Reformation. The empire then became divided along religious lines, with the north, the east, and many of the major cities – Strasbourg, Frankfurt, and Nuremberg – becoming Protestant while the southern and western regions largely remained Roman Catholic, Catholic.

At the beginning of Charles's reign, another ''Reichsregiment'' was set up again (1522), although Charles declared that he would only tolerate it in his absence and its chairman had to be a representative of his. Charles V was absent in Germany from 1521 to 1530. Similar to the one set up in the early 1500s, the ''Reichsregiment'' failed to create a federal authority independent of the emperor, due to the unsteady participation and differences between princes. Charles V defeated the Protestant princes in 1547 in the Schmalkaldic War, but the momentum was lost and the Protestant estates were able to survive politically despite military defeat. In the 1555 Peace of Augsburg, Charles V, through his brother Ferdinand, officially recognized the right of rulers to choose Catholicism or Lutheranism (Zwinglians, Calvinists and radicals were not included). In 1555, Pope Paul IV, Paul IV was elected pope and took the side of France, whereupon an exhausted Charles finally gave up his hopes of a world Christian empire.

Baroque period

Germany would enjoy relative peace for the next six decades. On the eastern front, the Turks continued to loom large as a threat, although war would mean further compromises with the Protestant princes, and so the Emperor sought to avoid it. In the west, the Rhineland increasingly fell under French influence. After the Dutch revolt against Spain erupted, the Empire remained neutral, ''de facto'' allowing the Netherlands to depart the empire in 1581. A side effect was the Cologne War, which ravaged much of the upper Rhine. Emperor Ferdinand III formally accepted Dutch neutrality in 1653, a decision ratified by the Reichstag in 1728.

After Ferdinand died in 1564, his son Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian II became Emperor, and like his father accepted the existence of Protestantism and the need for occasional compromise with it. Maximilian was succeeded in 1576 by Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, who preferred Ancient Greek philosophy, classical Greek philosophy to Christianity and lived an isolated existence in Bohemia. He became afraid to act when the Catholic Church was forcibly reasserting control in Austria and Hungary, and the Protestant princes became upset over this.

Imperial power sharply deteriorated by the time of Rudolf's death in 1612. When Bohemians rebelled against the Emperor, the immediate result was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), which devastated the Empire. Foreign powers, including France and Sweden, intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting Imperial power, but also seized considerable territory for themselves.

The actual end of the empire did not come for two centuries. The

Germany would enjoy relative peace for the next six decades. On the eastern front, the Turks continued to loom large as a threat, although war would mean further compromises with the Protestant princes, and so the Emperor sought to avoid it. In the west, the Rhineland increasingly fell under French influence. After the Dutch revolt against Spain erupted, the Empire remained neutral, ''de facto'' allowing the Netherlands to depart the empire in 1581. A side effect was the Cologne War, which ravaged much of the upper Rhine. Emperor Ferdinand III formally accepted Dutch neutrality in 1653, a decision ratified by the Reichstag in 1728.

After Ferdinand died in 1564, his son Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian II became Emperor, and like his father accepted the existence of Protestantism and the need for occasional compromise with it. Maximilian was succeeded in 1576 by Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II, who preferred Ancient Greek philosophy, classical Greek philosophy to Christianity and lived an isolated existence in Bohemia. He became afraid to act when the Catholic Church was forcibly reasserting control in Austria and Hungary, and the Protestant princes became upset over this.

Imperial power sharply deteriorated by the time of Rudolf's death in 1612. When Bohemians rebelled against the Emperor, the immediate result was the series of conflicts known as the Thirty Years' War (1618–48), which devastated the Empire. Foreign powers, including France and Sweden, intervened in the conflict and strengthened those fighting Imperial power, but also seized considerable territory for themselves.

The actual end of the empire did not come for two centuries. The Modern period

Prussia and Austria

By the rise of Louis XIV of France, Louis XIV, the Habsburgs were chiefly dependent on their Habsburg monarchy, hereditary lands to counter the rise of Prussia, which possessed territories inside the Empire. Throughout the 18th century, the Habsburgs were embroiled in various European conflicts, such as the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–1714), the War of the Polish Succession (1733–1735), and the War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748). The German dualism between Austria and Prussia dominated the empire's history after 1740.French Revolutionary Wars and final dissolution

From 1792 onwards, French Revolutionary Wars, revolutionary France was at war with various parts of the Empire intermittently.

The German mediatization was the series of mediatizations and secularizations that occurred between 1795 and 1814, during the latter part of the era of the French Revolution and then the Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleonic Era. "Mediatization" was the process of annexation, annexing the lands of one Imperial State, imperial estate to another, often leaving the annexed some rights. For example, the estates of the Imperial Knights were formally mediatized in 1806, having ''de facto'' been seized by the great territorial states in 1803 in the so-called ''Rittersturm''. "Secularization" was the abolition of the temporal power of an ecclesiastical ruler such as a bishop or an abbot and the annexation of the secularized territory to a secular territory.

The empire was dissolved on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire, Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon I of France, Napoleon at Battle of Austerlitz, Austerlitz (see Treaty of Pressburg (1805), Treaty of Pressburg). Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire into the Confederation of the Rhine, a satellite state, French satellite. Francis' House of Lorraine, House of Habsburg-Lorraine survived the demise of the empire, continuing to reign as Emperor of Austria, Emperors of Austria and King of Hungary, Kings of Hungary until the Habsburg empire's final dissolution in 1918 in the aftermath of World War I.

The Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine was replaced by a new union, the German Confederation in 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. It lasted until 1866 when Prussia founded the North German Confederation, a forerunner of the

From 1792 onwards, French Revolutionary Wars, revolutionary France was at war with various parts of the Empire intermittently.

The German mediatization was the series of mediatizations and secularizations that occurred between 1795 and 1814, during the latter part of the era of the French Revolution and then the Napoleon Bonaparte, Napoleonic Era. "Mediatization" was the process of annexation, annexing the lands of one Imperial State, imperial estate to another, often leaving the annexed some rights. For example, the estates of the Imperial Knights were formally mediatized in 1806, having ''de facto'' been seized by the great territorial states in 1803 in the so-called ''Rittersturm''. "Secularization" was the abolition of the temporal power of an ecclesiastical ruler such as a bishop or an abbot and the annexation of the secularized territory to a secular territory.

The empire was dissolved on 6 August 1806, when the last Holy Roman Emperor Francis II of the Holy Roman Empire, Francis II (from 1804, Emperor Francis I of Austria) abdicated, following a military defeat by the French under Napoleon I of France, Napoleon at Battle of Austerlitz, Austerlitz (see Treaty of Pressburg (1805), Treaty of Pressburg). Napoleon reorganized much of the Empire into the Confederation of the Rhine, a satellite state, French satellite. Francis' House of Lorraine, House of Habsburg-Lorraine survived the demise of the empire, continuing to reign as Emperor of Austria, Emperors of Austria and King of Hungary, Kings of Hungary until the Habsburg empire's final dissolution in 1918 in the aftermath of World War I.

The Napoleonic Confederation of the Rhine was replaced by a new union, the German Confederation in 1815, following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. It lasted until 1866 when Prussia founded the North German Confederation, a forerunner of the The Holy Roman Empire and the imperial families' dynastic empires

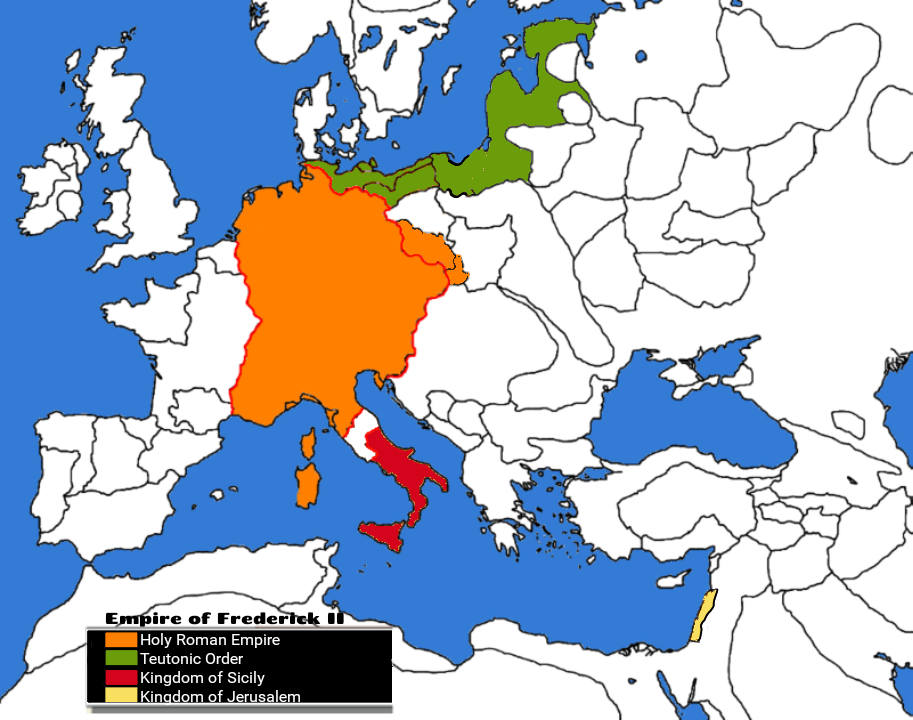

Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, inheriting both German aspirations for imperial sovereignty and the Norman Sicilian kings' dream of hegemony in the Mediterranean, had ambitious design for a world empire. Boettcher remarks that marriage policy also played an important role here, "The marital policy of the Staufer ranged from Iberia to Russia, from Scandinavia to Sicily, from England to Byzantium and to the crusader states in the East. Henry was already casting his eyes beyond Africa and Greece, to Asia Minor and Syria and of course on Jerusalem." His annexation of Sicily changed the strategic balance in the Italian peninsula. The emperor, who wanted to make all his lands hereditary, also asserted that papal fiefs were imperial fiefs. On his death at the age of 31 though, he was unable to pass his powerful position to his son, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, who had only been elected King of the Romans. The union between Sicily and the Empire thus remained personal union. Frederick II became King of Sicily in 1225 through marriage to Isabella II of Jerusalem, Isabella II (or Yolande) of Jerusalem and regained Bethlehem and Nazareth for the Christian side through negotiation with Al-Kamil. The Hohenstaufen dream of world empire ended with Frederick's death in 1250 though.

In its earlier days, the Empire provided the principal medium for Christianity to infiltrate the pagans' realms in the North and the East (Scandinavians, Magyars, Slavic people etc.). By the Reform era, the Empire, in its nature, was defensive and not aggressive, desiring of both internal peace and security against invading forces, a fact that even warlike princes such as Maximilian I appreciated. In the Early Modern age, the association with the Church (the Church Universal for the Luxemburgs, and the Catholic Church for the Habsburgs) as well as the emperor's responsibility for the defence of Central Europe remained a reality though. Even the trigger for the conception of the Imperial Reform under Sigismund was the idea of helping the Church to put its house in order.

Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, inheriting both German aspirations for imperial sovereignty and the Norman Sicilian kings' dream of hegemony in the Mediterranean, had ambitious design for a world empire. Boettcher remarks that marriage policy also played an important role here, "The marital policy of the Staufer ranged from Iberia to Russia, from Scandinavia to Sicily, from England to Byzantium and to the crusader states in the East. Henry was already casting his eyes beyond Africa and Greece, to Asia Minor and Syria and of course on Jerusalem." His annexation of Sicily changed the strategic balance in the Italian peninsula. The emperor, who wanted to make all his lands hereditary, also asserted that papal fiefs were imperial fiefs. On his death at the age of 31 though, he was unable to pass his powerful position to his son, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II, who had only been elected King of the Romans. The union between Sicily and the Empire thus remained personal union. Frederick II became King of Sicily in 1225 through marriage to Isabella II of Jerusalem, Isabella II (or Yolande) of Jerusalem and regained Bethlehem and Nazareth for the Christian side through negotiation with Al-Kamil. The Hohenstaufen dream of world empire ended with Frederick's death in 1250 though.

In its earlier days, the Empire provided the principal medium for Christianity to infiltrate the pagans' realms in the North and the East (Scandinavians, Magyars, Slavic people etc.). By the Reform era, the Empire, in its nature, was defensive and not aggressive, desiring of both internal peace and security against invading forces, a fact that even warlike princes such as Maximilian I appreciated. In the Early Modern age, the association with the Church (the Church Universal for the Luxemburgs, and the Catholic Church for the Habsburgs) as well as the emperor's responsibility for the defence of Central Europe remained a reality though. Even the trigger for the conception of the Imperial Reform under Sigismund was the idea of helping the Church to put its house in order.

Traditionally, German dynasties had exploited the potential of the imperial title to bring Eastern Europe into the fold, in addition to their lands north and south of the Alps. Marriage and inheritance strategies, following by (usually defensive) warfare, played a great role both for the Luxemburgs and the Habsburgs. It was under Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund of the Luxemburg, who married Mary, Queen of Hungary, Mary, Queen regnal and the rightful heir of Hungary and later consolidated his power with the marriage to the capable and well-connected noblewoman Barbara of Cilli, that the emperor's personal empire expanded to a kingdom outside the boundary of the Holy Roman Empire: Hungary. This last monarch of the Luxemburg dynasty (who wore four royal crowns) had managed to gain an empire almost comparable in scale to the later Habsburg empire, although at the same time they lost the Kingdom of Burgundy and control over Italian territories. The Luxemburgs' focus on the East, especially Hungary, allowed the new Burgundian rulers from the Valois dynasty to foster discontent among German princes. Thus, the Habsburgs were forced to refocus their attention on the West. Frederick III's cousin and predecessor, Albert II of Germany (who was Sigismund's son-in-law and heir through his marriage with Elizabeth of Luxembourg) had managed to combine the crowns of Germany, Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia under his rule, but he died young. During his rule, Maximilian I had a double focus on both the East and the West. The successful expansion (with the notable role of marriage policy) under Maximilian bolstered his position in the Empire, and also created more pressure for an Imperial Reform, imperial reform, so that they could get more resources and coordinated help from the German territories to defend their realms and counter hostile powers such as France. Ever since he became King of the Romans in 1486, the Empire provided essential help for his activities in Burgundian Netherlands as well as dealings with Bohemia, Hungary and other eastern polities. In the reigns of his grandsons, Croatia and the remaining rump of the Hungarian kingdom chose Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand as their ruler after he managed to rescue Silesia and Bohemia from Hungary's fate against the Ottoman. Simms notes that their choice was a contractual one, tying Ferdinand's rulership in these kingdoms and territories to his election as King of the Romans and his ability to defend Central Europe. In turn, the Habsburgs' imperial rule also "depended on holding these additional extensive lands as independent sources of wealth and prestige."

Traditionally, German dynasties had exploited the potential of the imperial title to bring Eastern Europe into the fold, in addition to their lands north and south of the Alps. Marriage and inheritance strategies, following by (usually defensive) warfare, played a great role both for the Luxemburgs and the Habsburgs. It was under Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, Sigismund of the Luxemburg, who married Mary, Queen of Hungary, Mary, Queen regnal and the rightful heir of Hungary and later consolidated his power with the marriage to the capable and well-connected noblewoman Barbara of Cilli, that the emperor's personal empire expanded to a kingdom outside the boundary of the Holy Roman Empire: Hungary. This last monarch of the Luxemburg dynasty (who wore four royal crowns) had managed to gain an empire almost comparable in scale to the later Habsburg empire, although at the same time they lost the Kingdom of Burgundy and control over Italian territories. The Luxemburgs' focus on the East, especially Hungary, allowed the new Burgundian rulers from the Valois dynasty to foster discontent among German princes. Thus, the Habsburgs were forced to refocus their attention on the West. Frederick III's cousin and predecessor, Albert II of Germany (who was Sigismund's son-in-law and heir through his marriage with Elizabeth of Luxembourg) had managed to combine the crowns of Germany, Hungary, Bohemia and Croatia under his rule, but he died young. During his rule, Maximilian I had a double focus on both the East and the West. The successful expansion (with the notable role of marriage policy) under Maximilian bolstered his position in the Empire, and also created more pressure for an Imperial Reform, imperial reform, so that they could get more resources and coordinated help from the German territories to defend their realms and counter hostile powers such as France. Ever since he became King of the Romans in 1486, the Empire provided essential help for his activities in Burgundian Netherlands as well as dealings with Bohemia, Hungary and other eastern polities. In the reigns of his grandsons, Croatia and the remaining rump of the Hungarian kingdom chose Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor, Ferdinand as their ruler after he managed to rescue Silesia and Bohemia from Hungary's fate against the Ottoman. Simms notes that their choice was a contractual one, tying Ferdinand's rulership in these kingdoms and territories to his election as King of the Romans and his ability to defend Central Europe. In turn, the Habsburgs' imperial rule also "depended on holding these additional extensive lands as independent sources of wealth and prestige."

The later Austrian Habsburgs from Ferdinand I were careful to maintain a distinction between their dynastic empire and the Holy Roman Empire. Peter Wilson argues that the institutions and structures developed by the Imperial Reform mostly served German lands and, although the Habsburg monarchy "remained closely entwined with the Empire", the Habsburgs deliberately refrained from including their other territories in its framework. "Instead, they developed their own institutions to manage what was, effectively, a parallel dynastic-territorial empire and which gave them an overwhelming superiority of resources, in turn allowing them to retain an almost unbroken grip on the imperial title over the next three centuries." Ferdinand had an interest in keeping Bohemia separate from imperial jurisdiction and making the connection between Bohemia and the Empire looser (Bohemia did not have to pay taxes to the Empire). As he refused the rights of an Imperial Elector as King of Bohemia (which provided him with half of his revenue), he was able to give Bohemia (as well as associated territories such as Upper and Lower Alsatia, Silesia and Moravia) the same privileged status as Austria, therefore affirming his superior position in the Empire. The Habsburgs also tried to mobilize imperial aid for Hungary (which, throughout the sixteenth century, cost the dynasty more money in defence expenditure than the total revenue it yielded). Since 1542, Charles V and Ferdinand had been able to collect the Common Penny tax, or ''Türkenhilfe'' (Turkish aid), designed to protect the Empire against the Ottomans or France. But as Hungary, unlike Bohemia, was not part of the Empire, the imperial aid for Hungary depended on political factors. The obligation was only in effect if Vienna or the Empire were threatened. Wilson notes that, "In the early 1520s the Reichstag hesitated to vote aid for Hungary’s King Louis II, because it regarded him as a foreign prince. This changed once Hungary passed to the Habsburgs on Louis’ death in battle in 1526 and the main objective of imperial taxation across the next 90 years was to subsidize the cost of defending the Hungarian frontier against the Ottomans. The bulk of the weaponry and other military materiel was supplied by firms based in the Empire and financed by German banks. The same is true of the troops who eventually evicted the Ottomans from Hungary between 1683 and 1699. The imperial law code of 1532 was used in parts of Hungary until the mid-seventeenth century, but otherwise Hungary had its own legal system and did not import Austrian ones. Hungarian nobles resisted the use of Germanic titles like Graf for count until 1606, and very few acquired the personal status of imperial prince."

Responding to the opinion that the Habsburg's dynastic concerns were damaging to the Holy Roman Empire, Whaley writes that, "There was no fundamental incompatibility between dynasticism and participation in the empire, either for the Habsburgs or for the Saxons or others." Imperial marriage strategies had double-edged effects for the Holy Roman Empire though. The Spanish connection was an example: while it provided a powerful partner in the defence of Christendom against the Ottomans, it allowed Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V to transfer the Burgundian Netherlands, Franche-Comte as well as other imperial fiefs such as Milan to his son Philip II of Spain, Philip II's Spanish Empire.

Other than the imperial families, other German princes possessed foreign lands as well, and foreign rulers could also acquire imperial fiefs and thus become imperial princes. This phenomenon contributed to the fragmentation of sovereignty, in which imperial vassals remained semi-sovereign, while strengthening the interconnections (and chances of mutual interference) between the Kingdom of Germany and the Empire in general with other kingdoms such as Denmark and Sweden, who accepted the status of imperial vassals on behalf of their German possessions (which were subjected to imperial laws). The two Scandinanvian monarchies honoured the obligations to come to the aid of the Empire in the wars of seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. They also imported German princely families as rulers, although in both cases, this did not produce direct unions. Denmark consistently tried to take advantage of its influence in imperial institutions to gain new imperial fiefs along the Elbe, although these attempts generally did not succeed.

The later Austrian Habsburgs from Ferdinand I were careful to maintain a distinction between their dynastic empire and the Holy Roman Empire. Peter Wilson argues that the institutions and structures developed by the Imperial Reform mostly served German lands and, although the Habsburg monarchy "remained closely entwined with the Empire", the Habsburgs deliberately refrained from including their other territories in its framework. "Instead, they developed their own institutions to manage what was, effectively, a parallel dynastic-territorial empire and which gave them an overwhelming superiority of resources, in turn allowing them to retain an almost unbroken grip on the imperial title over the next three centuries." Ferdinand had an interest in keeping Bohemia separate from imperial jurisdiction and making the connection between Bohemia and the Empire looser (Bohemia did not have to pay taxes to the Empire). As he refused the rights of an Imperial Elector as King of Bohemia (which provided him with half of his revenue), he was able to give Bohemia (as well as associated territories such as Upper and Lower Alsatia, Silesia and Moravia) the same privileged status as Austria, therefore affirming his superior position in the Empire. The Habsburgs also tried to mobilize imperial aid for Hungary (which, throughout the sixteenth century, cost the dynasty more money in defence expenditure than the total revenue it yielded). Since 1542, Charles V and Ferdinand had been able to collect the Common Penny tax, or ''Türkenhilfe'' (Turkish aid), designed to protect the Empire against the Ottomans or France. But as Hungary, unlike Bohemia, was not part of the Empire, the imperial aid for Hungary depended on political factors. The obligation was only in effect if Vienna or the Empire were threatened. Wilson notes that, "In the early 1520s the Reichstag hesitated to vote aid for Hungary’s King Louis II, because it regarded him as a foreign prince. This changed once Hungary passed to the Habsburgs on Louis’ death in battle in 1526 and the main objective of imperial taxation across the next 90 years was to subsidize the cost of defending the Hungarian frontier against the Ottomans. The bulk of the weaponry and other military materiel was supplied by firms based in the Empire and financed by German banks. The same is true of the troops who eventually evicted the Ottomans from Hungary between 1683 and 1699. The imperial law code of 1532 was used in parts of Hungary until the mid-seventeenth century, but otherwise Hungary had its own legal system and did not import Austrian ones. Hungarian nobles resisted the use of Germanic titles like Graf for count until 1606, and very few acquired the personal status of imperial prince."

Responding to the opinion that the Habsburg's dynastic concerns were damaging to the Holy Roman Empire, Whaley writes that, "There was no fundamental incompatibility between dynasticism and participation in the empire, either for the Habsburgs or for the Saxons or others." Imperial marriage strategies had double-edged effects for the Holy Roman Empire though. The Spanish connection was an example: while it provided a powerful partner in the defence of Christendom against the Ottomans, it allowed Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V to transfer the Burgundian Netherlands, Franche-Comte as well as other imperial fiefs such as Milan to his son Philip II of Spain, Philip II's Spanish Empire.

Other than the imperial families, other German princes possessed foreign lands as well, and foreign rulers could also acquire imperial fiefs and thus become imperial princes. This phenomenon contributed to the fragmentation of sovereignty, in which imperial vassals remained semi-sovereign, while strengthening the interconnections (and chances of mutual interference) between the Kingdom of Germany and the Empire in general with other kingdoms such as Denmark and Sweden, who accepted the status of imperial vassals on behalf of their German possessions (which were subjected to imperial laws). The two Scandinanvian monarchies honoured the obligations to come to the aid of the Empire in the wars of seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. They also imported German princely families as rulers, although in both cases, this did not produce direct unions. Denmark consistently tried to take advantage of its influence in imperial institutions to gain new imperial fiefs along the Elbe, although these attempts generally did not succeed.

Institutions

The Holy Roman Empire was neither a centralized State (polity), state nor a nation-state. Instead, it was divided into dozens – eventually hundreds – of individual entities governed by kings, dukes, counts, bishops, abbots, and other rulers, collectively known as Princes of the Holy Roman Empire, princes. There were also some areas ruled directly by the Emperor. From the High Middle Ages onwards, the Holy Roman Empire was marked by an uneasy coexistence with the princes of the local territories who were struggling to take power (sociology), power away from it. To a greater extent than in other medieval kingdoms such asImperial estates

The number of territories represented in the Imperial Diet was considerable, numbering about 300 at the time of theKing of the Romans

Imperial Diet (''Reichstag'')

The Imperial Diet (''Reichstag'', or ''Reichsversammlung'') was not a legislative body as is understood today, as its members envisioned it to be more like a central forum, where it was more important to negotiate than to decide. The Diet was theoretically superior to the emperor himself. It was divided into three classes. The first class, the Council of Electors, consisted of the electors, or the princes who could vote for King of the Romans. The second class, the Council of Princes, consisted of the other princes. The Council of Princes was divided into two "benches", one for secular rulers and one for ecclesiastical ones. Higher-ranking princes had individual votes, while lower-ranking princes were grouped into "colleges" by geography. Each college had one vote.

The third class was the Council of Imperial Cities, which was divided into two colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. The Council of Imperial Cities was not fully equal with the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The representation of the Free Cities at the Diet had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation was formally acknowledged only as late as 1648 with the

The Imperial Diet (''Reichstag'', or ''Reichsversammlung'') was not a legislative body as is understood today, as its members envisioned it to be more like a central forum, where it was more important to negotiate than to decide. The Diet was theoretically superior to the emperor himself. It was divided into three classes. The first class, the Council of Electors, consisted of the electors, or the princes who could vote for King of the Romans. The second class, the Council of Princes, consisted of the other princes. The Council of Princes was divided into two "benches", one for secular rulers and one for ecclesiastical ones. Higher-ranking princes had individual votes, while lower-ranking princes were grouped into "colleges" by geography. Each college had one vote.

The third class was the Council of Imperial Cities, which was divided into two colleges: Swabia and the Rhine. The Council of Imperial Cities was not fully equal with the others; it could not vote on several matters such as the admission of new territories. The representation of the Free Cities at the Diet had become common since the late Middle Ages. Nevertheless, their participation was formally acknowledged only as late as 1648 with the Imperial courts

The Empire also had two courts: the ''Reichshofrat'' (also known in English as the Aulic Council) at the court of the King/Emperor, and the ''Reichskammergericht'' (Imperial Chamber Court), established with the Imperial Reform of 1495 by Maximillian I. The Reichskammergericht and the Auclic Council were the two highest judicial instances in the Old Empire. The Imperial Chamber court's composition was determined by both the Holy Roman Emperor and the subject states of the Empire. Within this court, the Emperor appointed the chief justice, always a highborn aristocrat, several divisional chief judges, and some of the other puisne judges. The Aulic Council held standing over many judicial disputes of state, both in concurrence with the Imperial Chamber court and exclusively on their own. The provinces Imperial Chamber Court extended to breaches of the public peace, cases of arbitrary distraint or imprisonment, pleas which concerned the treasury, violations of the Emperor's decrees or the laws passed by the Imperial Diet, disputes about property between Imperial Estate, immediate tenants of the Empire or the subjects of different rulers, and finally suits against immediate tenants of the Empire, with the exception of criminal charges and matters relating to imperial fiefs, which went to the Aulic Council. The Aulic Council even allowed the emperors the means to depose rulers who did not live up to expectations.Imperial circles

As part of the Imperial Reform, six Imperial Circles were established in 1500; four more were established in 1512. These were regional groupings of most (though not all) of the various states of the Empire for the purposes of defense, imperial taxation, supervision of coining, peace-keeping functions, and public security. Each circle had its own parliament, known as a ''Kreistag'' ("Circle Diet"), and one or more directors, who coordinated the affairs of the circle. Not all imperial territories were included within the imperial circles, even after 1512; the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were excluded, as were Old Swiss Confederacy, Switzerland, the imperial fiefs in northern Italy, the lands of the Imperial Knights, and certain other small territories like the Lordship of Jever.

As part of the Imperial Reform, six Imperial Circles were established in 1500; four more were established in 1512. These were regional groupings of most (though not all) of the various states of the Empire for the purposes of defense, imperial taxation, supervision of coining, peace-keeping functions, and public security. Each circle had its own parliament, known as a ''Kreistag'' ("Circle Diet"), and one or more directors, who coordinated the affairs of the circle. Not all imperial territories were included within the imperial circles, even after 1512; the Lands of the Bohemian Crown were excluded, as were Old Swiss Confederacy, Switzerland, the imperial fiefs in northern Italy, the lands of the Imperial Knights, and certain other small territories like the Lordship of Jever.

Army

The Army of the Holy Roman Empire (German ''Reichsarmee'', ''Reichsheer'' or ''Reichsarmatur''; Latin ''exercitus imperii'') was created in 1422 and as a result of the Napoleonic Wars came to an end even before the Empire. It must not be confused with the Imperial Army (Holy Roman Empire), Imperial Army (''Kaiserliche Armee'') of the Emperor. Despite appearances to the contrary, the Army of the Empire did not constitute a permanent standing army that was always at the ready to fight for the Empire. When there was danger, an Army of the Empire was mustered from among the elements constituting it, in order to conduct an imperial military campaign or ''Reichsheerfahrt''. In practice, the imperial troops often had local allegiances stronger than their loyalty to the Emperor.Administrative centres

Throughout the first half of its history the Holy Roman Empire was reigned over by a Itinerant court, travelling court. Kings and emperors toured between the numerous Kaiserpfalzes (Imperial palaces), usually resided for several weeks or months and furnished local legal matters, law and administration. Most rulers maintained one or a number of favourites Imperial palace sites, where they would advance development and spent most of their time: Charlemagne (Foreign relations

The Habsburg royal family had its own diplomats to represent its interests. The larger principalities in the Holy Roman Empire, beginning around 1648, also did the same. The Holy Roman Empire did not have its own dedicated ministry of foreign affairs and therefore the Imperial Diet (Holy Roman Empire), Imperial Diet had no control over these diplomats; occasionally the Diet criticised them. When Regensburg served as the site of the Diet, France and, in the late 1700s, Russia, had diplomatic representatives there. Denmark, Great Britain, and Sweden had land holdings in Germany and so had representation in the Diet itself. The Netherlands also had envoys in Regensburg. Regensburg was the place where envoys met as it was where representatives of the Diet could be reached.Demographics

Population