Holloway (HM Prison) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HM Prison Holloway was a

Holloway prison was opened in 1852 as a mixed-sex prison, but due to growing demand for space for female prisoners, particularly due to the closure of

Holloway prison was opened in 1852 as a mixed-sex prison, but due to growing demand for space for female prisoners, particularly due to the closure of

* Amelia Sach and Annie Walters (3 February 1903)

*

* Amelia Sach and Annie Walters (3 February 1903)

*

Updown.org.uk – Upstairs, Downstairs: ''A Special Mischief''

Retrieved 30 September 2014

Ministry of Justice page on Holloway

* 'Bad Girls': a History of Holloway Priso

* 'Rare Birds – Voices of Holloway Prison

{{Authority control Prisons in London, Holloway 1852 establishments in England Buildings and structures in the London Borough of Islington Holloway Holloway Women in London

closed category In category theory, a branch of mathematics, a closed category is a special kind of category.

In a locally small category, the ''external hom'' (''x'', ''y'') maps a pair of objects to a set of morphisms. So in the category of sets, this is an o ...

prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol (dated, standard English, Australian, and historically in Canada), penitentiary (American English and Canadian English), detention center (or detention centre outside the US), correction center, correc ...

for adult women and young offenders in Holloway, London

Holloway is an inner-city district of the London Borough of Islington, north of Charing Cross, which follows the line of the Holloway Road ( A1). At the centre of Holloway is the Nag's Head commercial area which sits between the more residential ...

, England, operated by His Majesty's Prison Service

His Majesty's Prison Service (HMPS) is a part of HM Prison and Probation Service (formerly the National Offender Management Service), which is the part of His Majesty's Government charged with managing most of the prisons within England and Wal ...

. It was the largest women's prison in western Europe, until its closure in 2016.

History

Holloway prison was opened in 1852 as a mixed-sex prison, but due to growing demand for space for female prisoners, particularly due to the closure of

Holloway prison was opened in 1852 as a mixed-sex prison, but due to growing demand for space for female prisoners, particularly due to the closure of Newgate

Newgate was one of the historic seven gates of the London Wall around the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. Newgate lay on the west side of the wall and the road issuing from it headed over the River Fleet to M ...

, it became female-only in 1903.

Before the first world war, Holloway was used to imprison those suffragettes

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to member ...

who broke the law. These included Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

, Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and a militant fighte ...

, Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, Irish nationalism, nationalist, suffragist, soc ...

(also imprisoned for her part in the Irish Rebellion), Charlotte Despard

Charlotte Despard (née French; 15 June 1844 – 10 November 1939) was an Anglo-Irish suffragist, socialist, pacifist, Sinn Féin activist, and novelist. She was a founding member of the Women's Freedom League, Women's Peace Crusade, and the I ...

, Mary Richardson

Mary Raleigh Richardson (1882/3 – 7 November 1961) was a Canadian suffragette active in the women's suffrage movement in the United Kingdom, an arsonist, a socialist parliamentary candidate and later head of the women's section of the B ...

, Dora Montefiore, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington

Johanna Mary Sheehy Skeffington (née Sheehy; 24 May 1877 – 20 April 1946) was a suffragette and Irish nationalist. Along with her husband Francis Sheehy Skeffington, Margaret Cousins and James Cousins, she founded the Irish Women's Franchise ...

, and Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended t ...

.

In 1959, Joanna Kelley became Governor of Holloway. Kelley ensured that long-term prisoners received the best accommodation and they were allowed to have their own crockery, pictures and curtains. The prison created "family" groups of prisoners, group therapy and psychiatrists to support some prisoners where required.

In 1965, there was a change in responsibilities and the Probation Service

Probation in criminal law is a period of supervision over an offender, ordered by the court often in lieu of incarceration.

In some jurisdictions, the term ''probation'' applies only to community sentences (alternatives to incarceration), such ...

was tasked with looking after prisoners once they had served their sentence. Kelley was not keen on the idea. With Kelley's encouragement they formed the ''Griffins Society''. The name of the society came from the statues of two griffins that had been either side of the gates as women entered Holloway.

Until 1991, the Prison was staffed by Home Office appointed, female Prison Officers. Male hospital officers from H.M.P. Pentonville were on weekly secondments until 1976. Their mission was to provide support for the agency nurses who worked in Holloway. However, The first 'Male, basic grade' Prison Officer to be posted to HMP Holloway in its (Female inmates only) history, was Prison Officer (Trg) Thomas Ainsworth, who joined the establishment direct from HMP College Wakefield in May 1991.

After the death from suicide in January 2016 of inmate Sarah Reed, a paranoid schizophrenic being held on remand, the subsequent inquest in July 2017 identified failings in the care system. Shortly after Reed died, a report concluded she was unfit to plead at a trial.

Rebuilding

Holloway's Governor Joanna Kelley was promoted to assistant director of prisons (women) in 1966. In 1967, they began to rebuild Holloway Prison. The previous design had been a "star" design where a single warder could oversee many potentially troublesome prisoners and then act promptly to summon assistance. Kelley felt this was wrong as at the time most women prisoners were not violent. It was her ideas that inspired the redesigned prison based on her experience as governor. It was completed in 1977. During that time she had become an OBE in 1973. The new design allowed for "family" groups of sixteen prisoners. Her ideas were in the design of the buildings but her ideas were never enacted. The redevelopment resulted in the loss of the "grand turreted" gateway to the prison, which had been built in 1851; architectural criticGavin Stamp

Gavin Mark Stamp (15 March 194830 December 2017) was a British writer, television presenter and architectural historian.

Education

Stamp was educated at Dulwich College in South London from 1959 to 1967 as part of the "Dulwich Experiment", then ...

later regretted the loss and said that the climate of opinion at the time was such that the Victorian Society

The Victorian Society is a UK amenity society and membership organisation that campaigns to preserve and promote interest in Victorian and Edwardian architecture and heritage built between 1837 and 1914 in England and Wales. It is a registered ...

felt unable to object.Use

Holloway Prison held female adults and young offendersremanded

Remand may refer to:

* Remand (court procedure), when an appellate court sends a case back to the trial court or lower appellate court

* Pre-trial detention, detention of a suspect prior to a trial, conviction, or sentencing

See also

*'' Remando ...

or sentenced by the local courts. Accommodation at the prison was mostly single cells; however, there was also some dormitory accommodation.

Holloway Prison offered both full-time and part-time education to inmates, with courses including skills training workshops, British Industrial Cleaning Science (BICS), gardening, and painting.

There was a family-friendly visitors' centre, run by the Prison Advice and Care Trust

The Prison Advice and Care Trust (Pact) is an independent UK charity that provides practical services for prisoners and prisoners' families. First established as the Catholic Prisoners Aid Society in 1898, Pact works at several prisons across E ...

(pact), an independent charity.

Closure

The Chancellor of the Exchequer,George Osborne

George Gideon Oliver Osborne (born Gideon Oliver Osborne; 23 May 1971) is a former British politician and newspaper editor who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2010 to 2016 and as First Secretary of State from 2015 to 2016 in the ...

, announced in his Autumn Statement on 25 November 2015 that the prison would close and would be sold for housing. It closed in July 2016, with prisoners being moved to HMP Downview and HMP Bronzefield

HMP Bronzefield is an adult and young offender female prison located on the outskirts of Ashford in Surrey, England. Bronzefield is the only purpose-built private prison solely for women in the UK, and is the largest female prison in Europe. The ...

, both in Surrey.

As of September 2017, the prison buildings still stand, with draft proposals for the site including housing, a public open green space, playground, women's centre and a small amount of commercial space.

Notable inmates

Suffragettes

For decades, British campaigners had argued forvotes for women

A vote is a formal method of choosing in an election.

Vote(s) or The Vote may also refer to:

Music

*''V.O.T.E.'', an album by Chris Stamey and Yo La Tengo, 2004

*"Vote", a song by the Submarines from ''Declare a New State!'', 2006

Television

* ...

. It was only when a number of suffragist

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

s, despairing of change through peaceful means, decided to turn to militant protest that the "suffragette

A suffragette was a member of an activist women's organisation in the early 20th century who, under the banner "Votes for Women", fought for the right to vote in public elections in the United Kingdom. The term refers in particular to members ...

" was born. These women broke the law in pursuit of their aims, and many were imprisoned at Holloway for their criminal activity. They were not treated as political prisoners, the authorities arguing they were imprisoned for their vandalism, not their opinions. In protest, some went on hunger strike and were force fed so Holloway has a large symbolic role in the history of women's rights in the UK for those in sympathy with the movement. Suffragettes imprisoned there include Emmeline Pankhurst

Emmeline Pankhurst ('' née'' Goulden; 15 July 1858 – 14 June 1928) was an English political activist who organised the UK suffragette movement and helped women win the right to vote. In 1999, ''Time'' named her as one of the 100 Most Impo ...

, Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and a militant fighte ...

, Violet Mary Doudney

Violet Mary Doudney (5 March 1889 – 14 January 1952) was a teacher and militant suffragette who went on hunger strike in Holloway Prison where she was force-fed. She was awarded the Hunger Strike Medal by the Women's Social and Political ...

, Katie Edith Gliddon, Isabella Potbury, Evaline Hilda Burkitt

Evaline Hilda Burkitt (19 July 1876 – 7 March 1955) was a British suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). A militant activist for Women's suffrage, women's rights, she went on hunger strike in prison and was ...

, Georgina Fanny Cheffins

Georgina Fanny Cheffins (1863 – 29 July 1932) was an English militant suffragette who on her imprisonment in 1912 went on hunger strike for which action she received the Hunger Strike Medal from the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). ...

, Constance Bryer, Florence Tunks

Florence Olivia Tunks (19 July 1891 – 22 February 1985) was a militant suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who with Hilda Burkitt engaged in a campaign of arson in Suffolk in 1914 for which they both received ...

, Janie Terrero

Janie Terrero (14 April 1858 – 22 June 1944) was a militant suffragette who, as a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), was imprisoned and force-fed for which she received the WSPU's Hunger Strike Medal.

Early life

Bo ...

, Doreen Allen

Doreen Allen (1879 – 18 June 1963) was a militant English suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), who on being imprisoned was force-fed, for which she received the WSPU's Hunger Strike Medal For Valour ...

, Bertha Ryland

Bertha Wilmot Ryland (12 October 1882 – April 1977) was a militant suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who after slashing a painting in Birmingham Art Gallery in 1914 went on hunger strike in Winson Green ...

, Katharine Gatty, Charlotte Despard

Charlotte Despard (née French; 15 June 1844 – 10 November 1939) was an Anglo-Irish suffragist, socialist, pacifist, Sinn Féin activist, and novelist. She was a founding member of the Women's Freedom League, Women's Peace Crusade, and the I ...

, Janet Boyd

Janet Augusta Boyd (née Haig; 1850 – 22 September 1928) was a member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and militant suffragette who in 1912 went on hunger strike in prison for which action she was awarded the WSPU's Hunger Str ...

, Genie Sheppard, Mary Ann Aldham

Mary Ann Aldham (born Mary Ann Mitchell Wood; 28 September 1858 – 1940) was an English militant suffragette and member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) who was imprisoned at least seven times.Mary Richardson

Mary Raleigh Richardson (1882/3 – 7 November 1961) was a Canadian suffragette active in the women's suffrage movement in the United Kingdom, an arsonist, a socialist parliamentary candidate and later head of the women's section of the B ...

, Muriel and Arabella Scott

Arabella Scott (7 May 1886 – 27 August 1980) was a Scottish teacher, suffragette and campaigner. As a member of the Women's Freedom League (WFL) she took a petition to Downing Street in July 1909. She subsequently adopted more militant tact ...

, Alice Maud Shipley, Katherine Douglas Smith

Katherine Douglas Smith (1878 – after 1947) was a militant British suffragette and from 1908 a paid organiser of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU). She was also a member of the International Suffrage Club.

Activism

Douglas Smith ...

, Dora Montefiore, Christabel Pankhurst

Dame Christabel Harriette Pankhurst, (; 22 September 1880 – 13 February 1958) was a British suffragette born in Manchester, England. A co-founder of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), she directed its militant actions from exil ...

, Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington

Johanna Mary Sheehy Skeffington (née Sheehy; 24 May 1877 – 20 April 1946) was a suffragette and Irish nationalist. Along with her husband Francis Sheehy Skeffington, Margaret Cousins and James Cousins, she founded the Irish Women's Franchise ...

, Emily Townsend, Leonora Tyson, Ethel Smyth

Dame Ethel Mary Smyth (; 22 April 18588 May 1944) was an English composer and a member of the women's suffrage movement. Her compositions include songs, works for piano, chamber music, orchestral works, choral works and operas.

Smyth tended t ...

and the American Alice Paul

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American Quaker, suffragist, feminist, and women's rights activist, and one of the main leaders and strategists of the campaign for the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ...

. Detainees later received the Holloway brooch. In 1912 the anthem of the suffragettes – " The March of the Women", composed by Ethel Smyth with lyrics by Cicely Hamilton – was performed there.

Irish Republicans

Holloway held three important people closely associated with the Easter Rebellion of 1916:Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne MacBride ( ga, Maud Nic Ghoinn Bean Mhic Giolla Bhríghde; 21 December 1866 – 27 April 1953) was an English-born Irish republican revolutionary, suffragette and actress. Of Anglo-Irish descent, she was won over to Irish nationalism ...

, Kathleen Clarke

Kathleen Clarke (; ga, Caitlín Bean Uí Chléirigh; 11 April 1878 – 29 September 1972) was a founder member of Cumann na mBan, a women's paramilitary organisation formed in Ireland in 1914, and one of very few privy to the plans of the Eas ...

and Constance Markievicz

Constance Georgine Markievicz ( pl, Markiewicz ; ' Gore-Booth; 4 February 1868 – 15 July 1927), also known as Countess Markievicz and Madame Markievicz, was an Irish politician, revolutionary, Irish nationalism, nationalist, suffragist, soc ...

.

Fascists

Holloway held Diana Mitford underDefence Regulation 18B

Defence Regulation 18B, often referred to as simply 18B, was one of the Defence Regulations used by the British Government during and before the Second World War. The complete name for the rule was Regulation 18B of the Defence (General) Regula ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, and after a personal intervention from Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is ...

Winston Churchill, her husband Sir Oswald Mosley

Sir Oswald Ernald Mosley, 6th Baronet (16 November 1896 – 3 December 1980) was a British politician during the 1920s and 1930s who rose to fame when, having become disillusioned with mainstream politics, he turned to fascism. He was a member ...

was moved there. The couple lived together in a cottage in the prison grounds. They were released in 1943.

Norah Elam

Norah Elam, also known as Norah Dacre Fox (née Norah Doherty, 1878–1961), was a militant suffragette, anti-vivisectionist, feminist and fascist in the United Kingdom. Born at 13 Waltham Terrace in Dublin to John Doherty, a partner in a pap ...

had the distinction of being detained during both World Wars, three times during 1914 as a suffragette prisoner under the name Dacre Fox, then as a detainee under Regulation 18B in 1940, when she was part of the social circle that gathered around the Mosleys during their early internment period. Later, after her release, Elam had the further distinction of being the only former member of the British Union of Fascists

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was a British fascist political party formed in 1932 by Oswald Mosley. Mosley changed its name to the British Union of Fascists and National Socialists in 1936 and, in 1937, to the British Union. In 1939, ...

to be granted a visit with Oswald Mosley during his period of detention there.

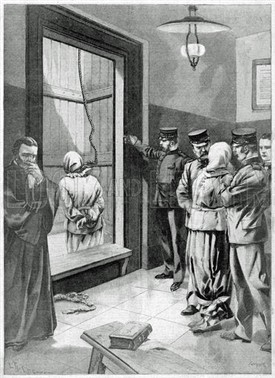

Executions

A total of fivejudicial execution

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty, is the state-sanctioned practice of deliberately killing a person as a punishment for an actual or supposed crime, usually following an authorized, rule-governed process to conclude that t ...

s by hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary' ...

took place at Holloway Prison between 1903 and 1955:

* Amelia Sach and Annie Walters (3 February 1903)

*

* Amelia Sach and Annie Walters (3 February 1903)

* Edith Thompson

Edith Jessie Thompson (25 December 1893 – 9 January 1923) and Frederick Edward Francis Bywaters (27 June 1902 – 9 January 1923) were a British couple executed for the murder of Thompson's husband Percy. Their case became a ''cause c ...

(9 January 1923)

* Styllou Christofi (13 December 1954)

* Ruth Ellis (13 July 1955)

The bodies of all executed prisoners were buried in unmarked graves within the walls of the prison, as was customary. In 1971 the prison underwent an extensive programme of rebuilding, during which the remains of all the executed women were exhumed. With the exception of Ruth Ellis (who was reburied in the churchyard of St Mary's Church, Old Amersham

St Mary's Church is a Church of England parish church in Old Amersham, Amersham in Buckinghamshire, England. The church is a grade I listed building.

History

The site of St Mary's Church has had Christian associations for many centuries. Early ...

), the remains of the four other women were subsequently reburied in a single grave at Brookwood Cemetery

Brookwood Cemetery, also known as the London Necropolis, is a burial ground in Brookwood, Surrey, England. It is the largest cemetery in the United Kingdom and one of the largest in Europe. The cemetery is listed a Grade I site in the Regi ...

near Woking

Woking ( ) is a town and borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in northwest Surrey, England, around from central London. It appears in Domesday Book as ''Wochinges'' and its name probably derives from that of a Anglo-Saxon settlement o ...

, Surrey. In 2018, the remains of Edith Thompson were reburied in her parents' grave in the City of London Cemetery

The City of London Cemetery and Crematorium is a cemetery and crematorium in the east of London. It is owned and operated by the City of London Corporation. It is designated Grade I on the Historic England National Register of Historic Park ...

.

Other inmates

Noteworthy inmates that were held at the original 1852-era prison includeOscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

, William Thomas Stead

William Thomas Stead (5 July 184915 April 1912) was a British newspaper editor who, as a pioneer of investigative journalism, became a controversial figure of the Victorian era. Stead published a series of hugely influential campaigns whilst ed ...

, Isabella Glyn, F. Digby Hardy, Kitty Byron

Emma 'Kitty' Byron (1878 – after 1908) was a British murderer found guilty in 1902 of stabbing to death her lover Arthur Reginald Baker, for which crime she received the death sentence. This was subsequently commuted to life imprisonment.

...

, Lady Ida Sitwell, wife of Sir George Sitwell, and Kate Meyrick the 'Night Club Queen'. Robber Zoe Progl became the first woman to escape over the wall of the prison in 1960.

More recently it housed, in 1966, Moors murderess Myra Hindley

The Moors murders were carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley between July 1963 and October 1965, in and around Manchester, England. The victims were five children—Pauline Reade, John Kilbride, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey, and Edward E ...

; in 1967, Kim Newell, a Welsh woman who was involved in the Red Mini Murder; also in the late 1960s, National Socialist supporter Françoise Dior

Marie Françoise Suzanne Dior (7 April 1932 – 20 January 1993) was a French socialite and neo-Nazi underground financier. She was the niece of French fashion designer Christian Dior and Resistance fighter Catherine Dior, who publicly distance ...

, charged with arson against synagogues; in 1977, American Joyce McKinney of the "Manacled Mormon case

The Manacled Mormon case, also known as the Mormon sex in chains case, was a case of reputed sexual assault and kidnap by an American woman, Joyce McKinney, of a young American Mormon missionary, Kirk Anderson, in England in 1977. Because McKi ...

"; between 1991 and 1993, Michelle and Lisa Taylor, the sisters convicted of the murder of Alison Shaughnessy

On 3 June 1991, 21 year old Alison Shaughnessy ( Blackmore; born 7 November 1969) was stabbed to death in the stairwell of her flat near Clapham Junction station. Shaughnessy was newly married, but her husband was having an affair with a 20-ye ...

before being controversially released on appeal a year later; Sheila Bowler, the music teacher wrongly imprisoned for the murder of her elderly aunt, was detained there before being transferred to Bullwood Hall

HM Prison Bullwood Hall is a former Category C women's prison and Young Offenders Institution, located in Hockley, Essex, England. The prison was operated by Her Majesty's Prison Service.

History

Bullwood Hall was built in the 1960s originall ...

; and in 2002, Maxine Carr, who gave a false alibi for Soham murderer Ian Huntley. In 2000, Dena Thompson

Dena Thompson (born 1960), commonly known as The Black Widow, is a convicted murderer, confidence trickster and bigamist. She habitually met men through lonely hearts columns and stole their money. She is currently in prison for murdering for ...

was also known to have been imprisoned at Holloway for attempted murder, before she was convicted of murdering another victim. Sharon Carr, Britain's youngest female murderer who killed aged only 12, also spent time at Holloway.

Other inmates included Linda Calvey

Linda Calvey (born Linda E P Welford, 8 April 1948 in Ilford, Essex, England) is an English murderer, author and former armed robber, convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for killing her lover Ronnie Cook. She was known as the "Black Wi ...

, Chantal McCorkle, and Emma Humphreys

Emma Clare Humphreys (30 October 1967 – 11 July 1998) was a Welsh woman who was imprisoned in England in December 1985 at Her Majesty's pleasure, after being convicted of the murder of her violent 33-year-old boyfriend and pimp, Trevor Armitage ...

.

In 2014 disgraced judge and barrister Constance Briscoe

Constance Briscoe (born 18 May 1957 in England) is a former barrister, and was one of the first black female Recorder (judge), recorders in England and Wales. In May 2014, she was jailed for three counts of doing an act tending to Perverting the c ...

began a 16-month sentence at the prison.

Inspections, inquiries and reports

In October 1999, it was announced that healthcare campaigner andagony aunt

An advice column is a column in a question and answer format. Typically, a (usually anonymous) reader writes to the media outlet with a problem in the form of a question, and the media outlet provides an answer or response.

The responses are wr ...

Claire Rayner had been called in to advise on an improved healthcare provision at Holloway Prison. Rayner's appointment was announced after the introduction of emergency measures at the prison's healthcare unit after various failures.

In September 2001, an inspection report from His Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons

His Majesty's Chief Inspector of Prisons is the head of HM Inspectorate of Prisons and the senior inspector of prisons, young offender institutions and immigration service detention and removal centres in England and Wales. The current chief inspe ...

claimed that Holloway Prison was failing many of its inmates, mainly due to financial pressures. However, the report stated that the prison had improved in a number of areas, and praised staff working at the jail.

In March 2002, Managers at Holloway were transferred to other prisons following an inquiry by the Prison Service. The inquiry followed a number of allegations from prison staff concerning sexual harassment, bullying and intimidation from managers. The inquiry supported some of these claims.

An inspection report from in June 2003, stated that conditions had improved at Holloway Prison. However the report criticised levels of hygiene at the jail, as well as the lack of trained staff, and poor safety for inmates. A further inspection report in September 2008 again criticised safety levels for inmates of Holloway, claiming that bullying and theft were rife at the prison. The report also noted high levels of self-harm and poor mental health among the inmates.

A further inspection in 2010 again noted improvements but found that most prisoners said they felt unsafe and that there remained 35 incidents a week of self-harm. The prison's operational capacity is 501.

Sarah Reed case

On 11 January 2016, Sarah Reed, an inmate at Holloway, was found dead in her cell. Her family were told by prison staff that she had strangled herself while lying on her bed. For ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper Sunday editions, published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group, Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. ...

'', Yvonne Roberts

Yvonne Roberts (born 1948) is an English journalist. She was born in Newport Pagnell, Buckinghamshire.

Her family moved to Madrid for three years when she was a few months old and she lived in a number of locations through the rest of her childh ...

wrote "Sarah's final days were harrowing. She was hallucinating, chanting, without the medication she had relied on for years, sleepless, complaining a demon punched her awake at night. She was on a basic regime, punishment for what was classed as bad behaviour. In spite of her mental and physical fragility, she was isolated, the cell hatch closed, without hot water, heating or a properly cleaned cell. 'For safety and security' a four-strong 'lockdown' team of prison officers delivered basic care." Observations of Reed had been cut to only one an hour though she was obviously severely psychotic, had threatened suicide and had self harm

Self-harm is intentional behavior that is considered harmful to oneself. This is most commonly regarded as direct injury of one's own skin tissues usually without a suicidal intention. Other terms such as cutting, self-injury and self-mutilati ...

ed. A prison officer told Reed's mother, "We deal with restraint and maintaining the law. We're not designed to deal with health issues."

The jury at her inquest decided that Reed took her own life when the balance of her mind was disturbed, but were unclear whether she had intended to kill herself. They said failure to manage her medication and the failure to complete the fitness to plead assessment in a reasonable time were factors in her death. The jury were also concerned about how Reed was monitored and claimed Reed received inadequate treatment in prison for her distress.

Deborah Coles of Inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a co ...

said: "Sarah Reed was a woman in torment, imprisoned for the sake of two medical assessments to confirm what was resoundingly clear, that she needed specialist care not prison. Her death was a result of multi-agency failures to protect a woman in crisis. Instead of providing her with adequate support, the prison treated her ill mental health as a discipline, control and containment issue."

In popular culture

Film

* One of the characters in the 1997 Canadian sci-fi/horror movie ''Cube

In geometry, a cube is a three-dimensional solid object bounded by six square faces, facets or sides, with three meeting at each vertex. Viewed from a corner it is a hexagon and its net is usually depicted as a cross.

The cube is the on ...

'' is named after Holloway Prison.

Literature

* InElizabeth George

Susan Elizabeth George (born February 26, 1949) is an American writer of mystery novels set in Great Britain.

She is best known for a series of novels featuring Inspector Thomas Lynley. The 21st book in the series appeared in January 2022. T ...

's 1994 novel '' Playing for the Ashes'', a character is expected to be sent to Holloway if convicted.

* In Dorothy L. Sayers

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (; 13 June 1893 – 17 December 1957) was an English crime writer and poet. She was also a student of classical and modern languages.

She is best known for her mysteries, a series of novels and short stories set between th ...

's novel ''Strong Poison

''Strong Poison'' is a 1930 mystery novel by Dorothy L. Sayers, her fifth featuring Lord Peter Wimsey and the first in which Harriet Vane appears.

Plot

The novel opens with mystery author Harriet Vane on trial for the murder of her former lov ...

'', Harriet Vane

Harriet Deborah Vane, later Lady Peter Wimsey, is a fictional character in the works of British writer Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957).

Vane, a mystery writer, initially meets Lord Peter Wimsey while she is on trial for poisoning her lover (' ...

is held in HM Holloway Prison during the trial.

Music

*Belle and Sebastian

Belle and Sebastian are a Scottish indie pop band formed in Glasgow in 1996. Led by Stuart Murdoch, the band has released eleven albums. They are often compared with acts such as The Smiths and Nick Drake. The name "Belle and Sebastian" comes ...

's "The Boy with the Arab Strap" draws inspiration from a drive past the prison for the first verse.

* The band Bush wrote a song about the prison called "Personal Holloway," on their album ''Razorblade Suitcase

''Razorblade Suitcase'' is the second studio album by English rock band Bush, released on 19 November 1996 by Trauma and Interscope Records. The follow-up to their 1994 debut '' Sixteen Stone'', it was recorded at Abbey Road Studios in London ...

''.

* The Kinks

The Kinks were an English rock band formed in Muswell Hill, north London, in 1963 by brothers Ray and Dave Davies. They are regarded as one of the most influential rock bands of the 1960s. The band emerged during the height of British rhyt ...

' "Holloway Jail" appears on ''Muswell Hillbillies

''Muswell Hillbillies'' is the tenth studio album by the English rock group the Kinks. Released in November 1971, it was the band's first album for RCA Records. The album is named after the Muswell Hill area of North London, where band leader ...

''.

* Marillion

Marillion are a British rock band, formed in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, in 1979. They emerged from the post-punk music scene in Britain and existed as a bridge between the styles of punk rock and classic progressive rock, becoming the mos ...

's song "Holloway Girl" is on their album '' Seasons End''.

* Million Dead

Million Dead were an English post-hardcore band from London, active between 2000 and 2005.

History

The band was founded in 2000 by Cameron Dean and Julia Ruzicka, after both came to London from Australia. They were joined by Ben Dawson, who h ...

have "Holloway Prison Blues" on their album '' Harmony No Harmony''.

* In Potter Payper's 2013 album ''Training day'', it is mentioned his mother attended Holloway prison in the song 'Purple Rain'- “ 99 they said my mummy went on holiday, I found out my mummy was in Holloway“

Television

* In theThames Television

Thames Television, commonly simplified to just Thames, was a Broadcast license, franchise holder for a region of the British ITV (TV network), ITV television network serving Greater London, London and surrounding areas from 30 July 1968 until th ...

series ''Rumpole Of The Bailey

''Rumpole of the Bailey'' is a British television series created and written by the British writer and barrister John Mortimer. It starred Leo McKern as Horace Rumpole, a middle-aged London barrister who defended a broad variety of clients, oft ...

'' episode "Rumpole and the Alternative Society," the girl whom Rumpole was defending (until she admitted her guilt to him) was sentenced to three years imprisonment which she served at HM Holloway Prison.

* In the TV series ''Upstairs, Downstairs Upstairs Downstairs may refer to:

Television

*Upstairs, Downstairs (1971 TV series), ''Upstairs, Downstairs'' (1971 TV series), a British TV series broadcast on ITV from 1971 to 1975

*Upstairs Downstairs (2010 TV series), ''Upstairs Downstairs'' ...

'', the second-season episode "A Special Mischief" has Elizabeth Bellamy joining a band of suffragettes who go out one night vandalising wealthy homes. Rose, the parlourmaid, follows them; they are apprehended by the police. Rose is mistakenly thought to be a suffragette and is put in a ladies' prison, and Holloway is very much implied. Elizabeth is spared going to jail as her bail is paid for by Julius Karekin, one of the rich men being targeted. Elizabeth and Karekin bail Rose out of prison.Retrieved 30 September 2014

Caitlin Davies

Caitlin Davies (born 6 March 1964) is an English author, journalist and teacher. Her parents are Hunter Davies and Margaret Forster, both well-known writers.

has written ''Bad Girls'' (published by John Murray), a history of Holloway Prison. The prison closed in July 2016; the site is being redeveloped for housing and a Women's Building as a transformative justice project. Davies was the only journalist granted access to the prison and its archives.

References

External links

Ministry of Justice page on Holloway

* 'Bad Girls': a History of Holloway Priso

* 'Rare Birds – Voices of Holloway Prison

{{Authority control Prisons in London, Holloway 1852 establishments in England Buildings and structures in the London Borough of Islington Holloway Holloway Women in London