Hohenasperg on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Hohenasperg, located in the federal state of

Hohenasperg, located in the federal state of

Around 500 BC, the Hohenasperg was a

Around 500 BC, the Hohenasperg was a  The first time Asperg was referred to was in the year 819, as the Shire Gozberg granted local suzerainty to Weissenburg Abbey in the

The first time Asperg was referred to was in the year 819, as the Shire Gozberg granted local suzerainty to Weissenburg Abbey in the

The use of the fortress as a prison is responsible for the fact that Hohenasperg is jokingly referred to as "Württemberg's highest mountain" as they say "it takes only five minutes to come to the top, but years to come back down again."

The use of the fortress as a prison is responsible for the fact that Hohenasperg is jokingly referred to as "Württemberg's highest mountain" as they say "it takes only five minutes to come to the top, but years to come back down again."

was constructed, which also supports police radio antennas. Since 1894, a prison for the civil penal system has been located on Hohenasperg hill. In the meantime the central hospital for the Baden-Württemberg penal system was placed on the Hohenasperg.

In May 1940, the prison was used as a way station during the first centrally planned

In May 1940, the prison was used as a way station during the first centrally planned

1946-1947 The U.S. Seventh Army used Hohenasperg as an Internment camp.

In the book, "The Prison Called Hohenasperg", American born and raised author Arthur D. Jacobs provides his experience as a twelve- and thirteen-year-old prisoner in Hohenasperg.

In June 1959

1946-1947 The U.S. Seventh Army used Hohenasperg as an Internment camp.

In the book, "The Prison Called Hohenasperg", American born and raised author Arthur D. Jacobs provides his experience as a twelve- and thirteen-year-old prisoner in Hohenasperg.

In June 1959

Keltischer Fuerstensitz Hohenasperg

Patrick Nowak & Daniel Behrmann: Asberg - Auschwitz. Der NS-Völkermord an den Sinti und Roma am Beispiel der Pfalz

- Auschwitz.pdf

{{Authority control Prisons in Germany

Hohenasperg, located in the federal state of

Hohenasperg, located in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg (; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million inhabitants across a ...

near Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; Swabian: ; ) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is located on the Neckar river in a fertile valley known as the ''Stuttgarter Kessel'' (Stuttgart Cauldron) and lies an hour from the ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, of which it is administratively part, is an ancient fortress and prison overlooking the town of Asperg

Asperg () is a town in the district of Ludwigsburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

History

Asperg was established by the County Palatine of Tübingen, whose ruling house had a cadet named Asperg, around a preexisting castle. The town and castle ...

.

It was an important Celtic oppidum

An ''oppidum'' (plural ''oppida'') is a large fortified Iron Age settlement or town. ''Oppida'' are primarily associated with the Celtic late La Tène culture, emerging during the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, spread across Europe, stretchi ...

, and a number of very important "princely" burials are close by, in particular the Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave

The Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave is a richly-furnished Celtic burial chamber near Hochdorf an der Enz (municipality of Eberdingen) in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, dating from 530 BC in the Hallstatt culture period. It was discovered in 1968 by an ...

. Geography

Hohenasperg is located on a 90-metre-highLate Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch ...

hill. The hill is located in an upland area, but because of its steep overhangs and wide plateau, it is visible from a long distance and offers an ideal location for a fortification

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

.

History

Around 500 BC, the Hohenasperg was a

Around 500 BC, the Hohenasperg was a Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

principality with a refuge. Numerous Celtic burial sites in the surrounding area are aligned so as to offer a line of sight to the Hohenasperg, e.g. the large Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave

The Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave is a richly-furnished Celtic burial chamber near Hochdorf an der Enz (municipality of Eberdingen) in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, dating from 530 BC in the Hallstatt culture period. It was discovered in 1968 by an ...

, the Grafenbühl grave or the gravesite on the Katharinenlinde by Schwieberdingen

Schwieberdingen is a municipality of the Ludwigsburg district in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. The town itself is located about from Stuttgart, the state capital, and from Ludwigsburg, the district capital. Schwieberdingen belongs to the Stu ...

. The Kleinaspergle, which has been well-known since an excavation in 1839, is a burial mound lying 1,000 metres south of Hohenasperg, which offers an exceptionally good view of the Hohenasperg.

Around 500 AD, after the victory of the Franks

The Franks ( la, Franci or ) were a group of Germanic peoples whose name was first mentioned in 3rd-century Roman sources, and associated with tribes between the Lower Rhine and the Ems River, on the edge of the Roman Empire.H. Schutz: Tools, ...

over the Alamanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni, were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Caracalla of 213, the Alemanni captured the in 260, and later expanded into pres ...

, Hohenasperg became the seat of the Frankish Lord and Frankish Thing

Thing or The Thing may refer to:

Philosophy

* An object

* Broadly, an entity

* Thing-in-itself (or ''noumenon''), the reality that underlies perceptions, a term coined by Immanuel Kant

* Thing theory, a branch of critical theory that focuses ...

, the legislative assembly. At this time Hohenasperg was called "Ascicberg."

The first time Asperg was referred to was in the year 819, as the Shire Gozberg granted local suzerainty to Weissenburg Abbey in the

The first time Asperg was referred to was in the year 819, as the Shire Gozberg granted local suzerainty to Weissenburg Abbey in the Alsace

Alsace (, ; ; Low Alemannic German/ gsw-FR, Elsàss ; german: Elsass ; la, Alsatia) is a cultural region and a territorial collectivity in eastern France, on the west bank of the upper Rhine next to Germany and Switzerland. In 2020, it had ...

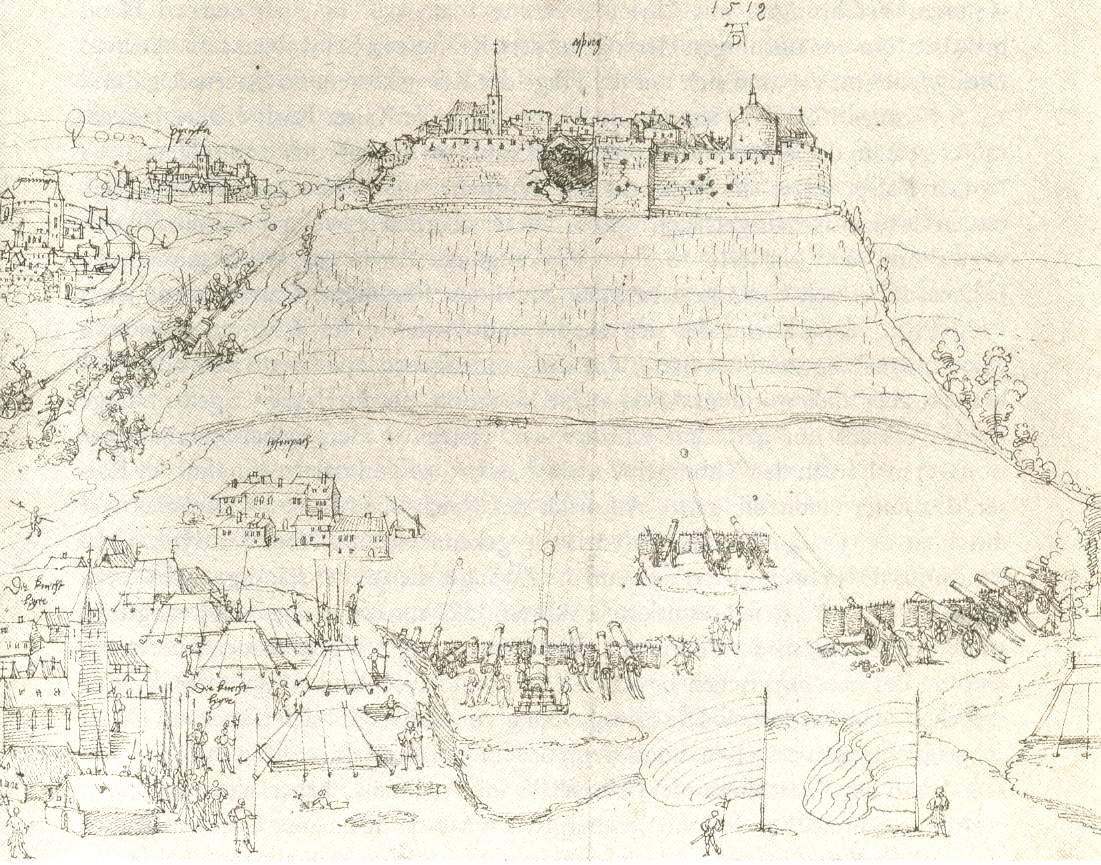

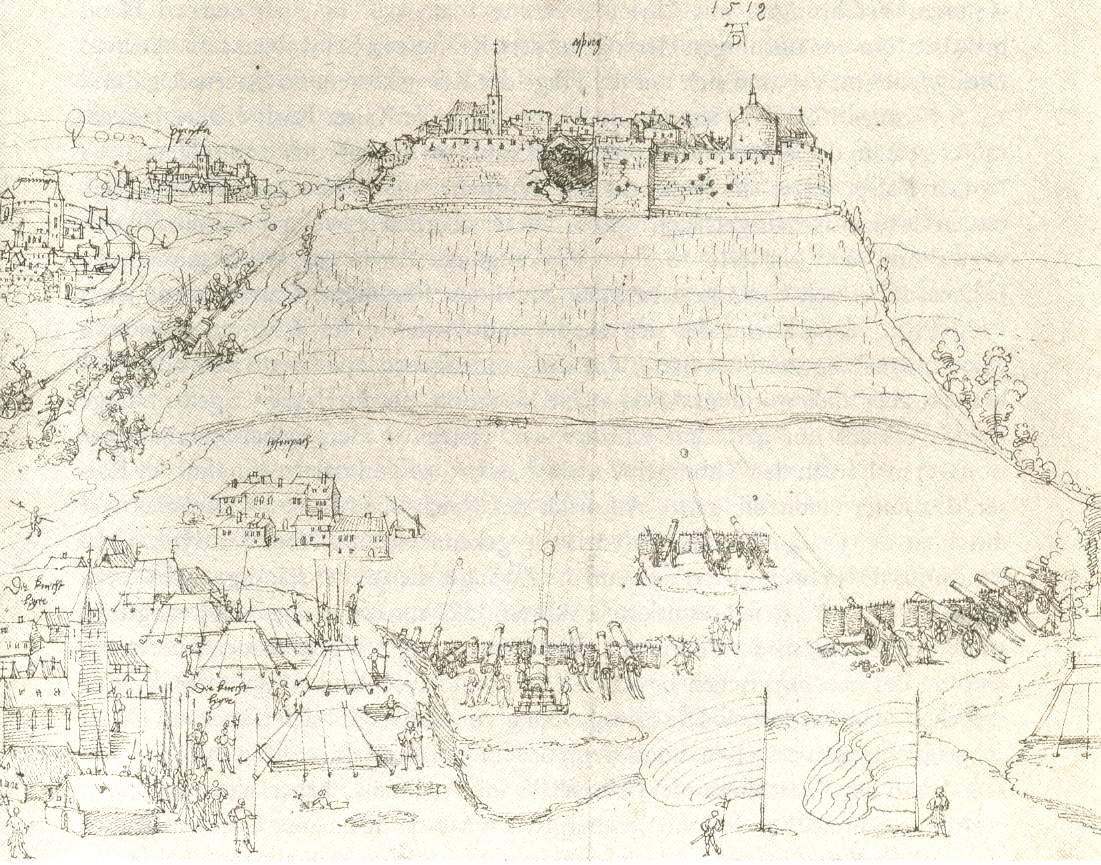

. The location however achieved more importance in the 13th century with the founding of the independent town of Hohenasperg, which lasted until 1909. Hohenasperg was officially chartered in 1510. In 1519, forces of the Swabian League

The Swabian League (''Schwäbischer Bund'') was a mutual defence and peace keeping association of Imperial State, Imperial Estates – free Imperial cities, prelates, principalities and knights – principally in the territory of the early mediev ...

under George von Frundsberg

Georg von Frundsberg (24 September 1473 – 20 August 1528) was a German military and Landsknecht leader in the service of the Holy Roman Empire and Imperial House of Habsburg. An early modern proponent of infantry tactics, he established ...

laid siege to Hohenasperg where Duke Ulrich of Württemberg was holding out.

On 12 May 1525, the peasant leader, Jäcklein Rohrbach, was taken prisoner by the governor of Asperg. He was held there until the surrender of the Steward of Waldburg-Zeil

Waldburg-Zeil was a County and later Principality within Holy Roman Empire, ruled by the House of Waldburg, located in southeastern Baden-Württemberg, Germany, located around Schloss Zeil, near Leutkirch im Allgäu.

History

Waldburg-Zeil w ...

. After 1535, the castle was expanded and turned into a fortress. The residents were resettled at the foot of the hill.

Between 1634 and 1635, during the Thirty Years War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an es ...

, the castle was defended against imperial troops by a garrison of Protestants

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century against what its followers perceived to b ...

from Württemberg, reinforced by Swedish

Swedish or ' may refer to:

Anything from or related to Sweden, a country in Northern Europe. Or, specifically:

* Swedish language, a North Germanic language spoken primarily in Sweden and Finland

** Swedish alphabet, the official alphabet used by ...

forces. The siege ended finally with the surrender to the imperial troops, who occupied the fortress until 1649.

After the Thirty Years War, the fortress was returned to the rule of Württemberg. In 1688 and 1693, it was occupied by French troops; afterwards it lost its importance as a defensive fortress and became a garrison and a state prison. In 1718, Asperg was integrated into the district Ludwigsburg

Ludwigsburg (; Swabian: ''Ludisburg'') is a city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, about north of Stuttgart city centre, near the river Neckar. It is the largest and primary city of the Ludwigsburg district with about 88,000 inhabitants. It is ...

, but 17 years later became its own district. In 1781, Asperg was permanently incorporated into the district of Ludwigsburg.

Prisoners

The use of the fortress as a prison is responsible for the fact that Hohenasperg is jokingly referred to as "Württemberg's highest mountain" as they say "it takes only five minutes to come to the top, but years to come back down again."

The use of the fortress as a prison is responsible for the fact that Hohenasperg is jokingly referred to as "Württemberg's highest mountain" as they say "it takes only five minutes to come to the top, but years to come back down again."

Old Empire

In 1737,Joseph Süß Oppenheimer

Joseph Süß Oppenheimer (1698? – February 4, 1738) was a German Jewish banker and court Jew for Duke Karl Alexander of Württemberg in Stuttgart. Throughout his career, Oppenheimer made scores of powerful enemies, some of whom conspired to b ...

, a Jew and the financial adviser to the Duke of Württemberg, was arrested and, in a dubious political trial, was sentenced to death. The poet C. F. D. Schubart was held prisoner there between 1777 and 1787. Schubart's fate became the subject of Friedrich Schiller

Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller (, short: ; 10 November 17599 May 1805) was a German playwright, poet, and philosopher. During the last seventeen years of his life (1788–1805), Schiller developed a productive, if complicated, friends ...

's Drama "The Robber." Schiller himself had escaped the confinement of the Hohenasperg by fleeing to Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (german: Universitätsstadt Mannheim), is the second-largest city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg after the state capital of Stuttgart, and Germany's 2 ...

in the neighboring Electorate of the Palatinate

The Electoral Palatinate (german: Kurpfalz) or the Palatinate (), officially the Electorate of the Palatinate (), was a state that was part of the Holy Roman Empire. The electorate had its origins under the rulership of the Counts Palatine of ...

.

19th century

During the rule of KingFrederick of Württemberg Frederick may refer to:

People

* Frederick (given name), the name

Nobility

Anhalt-Harzgerode

*Frederick, Prince of Anhalt-Harzgerode (1613–1670)

Austria

* Frederick I, Duke of Austria (Babenberg), Duke of Austria from 1195 to 1198

* Frederi ...

, deserters, military prisoners, and separatists from the Radical Pietist

Pietism (), also known as Pietistic Lutheranism, is a movement within Lutheranism that combines its emphasis on biblical doctrine with an emphasis on individual piety and living a holy Christianity, Christian life, including a social concern for ...

group from the circle of Rottenacker were kept at Fort Hohenasperg. By 1813, about 400 prisoners were arrested on the fortress. When his son King William I of Württemberg

King is the title given to a male monarch in a variety of contexts. The female equivalent is queen, which title is also given to the consort of a king.

*In the context of prehistory, antiquity and contemporary indigenous peoples, the tit ...

became ruler in 1817, corporal punishment, such as running the gauntlet

Running is a method of terrestrial locomotion allowing humans and other animals to move rapidly on foot. Running is a type of gait characterized by an aerial phase in which all feet are above the ground (though there are exceptions). This is ...

, was abolished.

Further inmates in Fort Hohenasperg included the writer Berthold Auerbach

Berthold Auerbach (28 February 1812 – 8 February 1882) was a German-Jewish poet and author. He was the founder of the German "tendency novel", in which fiction is used as a means of influencing public opinion on social, political, moral, and r ...

, who was kept here between 1837 and 1838; Friedrich Kammerer (1833); the doctor and poet Theobald Kerner (1850–1851); the theologian Karl Hase

Karl August von Hase (25 August 1800 – 3 January 1890) was a German Protestant theologian and church historian.

Background

He was born at Steinbach (near Penig) in Saxony. He studied at Leipzig and Erlangen, and in 1829 was called to Je ...

; the satirist Johannes Nefflen; the poet Leo von Seckendorff, the writer Theodor Griesinger; and many more, mostly political dissidents, who in general were held prisoner because of their anti-monarchistic views.

In 1887 and 1888 a water tower

A water tower is an elevated structure supporting a water tank constructed at a height sufficient to pressurize a water distribution system, distribution system for potable water, and to provide emergency storage for fire protection. Water towe ...

br>was constructed, which also supports police radio antennas. Since 1894, a prison for the civil penal system has been located on Hohenasperg hill. In the meantime the central hospital for the Baden-Württemberg penal system was placed on the Hohenasperg.

Early years of the Nazi era

During spring and summer 1933, numerous members of Hitler's opposition, the Social Democracy, Social Democrats andCommunists

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a so ...

, were imprisoned at Hohenasperg. Amongst these prisoners was the Governor of Württemberg, Eugen Bolz

Eugen Anton Bolz (15 December 1881 – 23 January 1945) was a German politician and a member of the resistance to the Nazi régime.

Life

Born in Rottenburg am Neckar, Bolz was his parents' twelfth child. His father Joseph Bolz was a salesman ...

, who was murdered during ''Aktion Gitter

Aktion Gitter was a "mass arrest action" by the Gestapo which took place in Germany between 22 and 23 August 1944. It came just over a month after the failed attempt to assassinate the country's leader, Adolf Hitler, on 20 July 1944. The program ...

'' in Berlin in 1945. At least 101 prisoners died in Hohenasperg under its hard penal system, and 20 of their names have been identified by the Ludwigsburg

Ludwigsburg (; Swabian: ''Ludisburg'') is a city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, about north of Stuttgart city centre, near the river Neckar. It is the largest and primary city of the Ludwigsburg district with about 88,000 inhabitants. It is ...

VVN, an antifascist organization. These names are remembered on a plaque in the Prisoner's Cemetery.

Transit camp for deportation to concentration camps (1940–1943)

In May 1940, the prison was used as a way station during the first centrally planned

In May 1940, the prison was used as a way station during the first centrally planned deportation

Deportation is the expulsion of a person or group of people from a place or country. The term ''expulsion'' is often used as a synonym for deportation, though expulsion is more often used in the context of international law, while deportation ...

of Sinti

The Sinti (also ''Sinta'' or ''Sinte''; masc. sing. ''Sinto''; fem. sing. ''Sintesa'') are a subgroup of Romani people mostly found in Germany and Central Europe that number around 200,000 people. They were traditionally itinerant, but today o ...

out of southwest Germany, west of the Rhine River (Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main (river), Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-we ...

, Ingelheim

Ingelheim (), officially Ingelheim am Rhein ( en, Ingelheim upon Rhine), is a town in the Mainz-Bingen district in the Rhineland-Palatinate state of Germany. The town sprawls along the Rhine's west bank. It has been Mainz-Bingen's district seat ...

, Worms Worms may refer to:

*Worm, an invertebrate animal with a tube-like body and no limbs

Places

*Worms, Germany

Worms () is a city in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany, situated on the Upper Rhine about south-southwest of Frankfurt am Main. It had ...

). The deportation was carried using a special train, families were escorted through the village by foot, with police surveillance. In the prison, examinations were conducted by the Ritter Research Institute, which decided the fate of the inmates. The institute was named for the "scientific racist" Robert Ritter. Further deportations were sent to the General Government

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

, the area of Germany-occupied Poland. Non-gypsies were sent back.

At least until the beginning of 1943, the prison was used as a way station for Sinti who were being sent to concentration camps. Later deportations led to the Gypsy Family Camp, the concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau

Auschwitz concentration camp ( (); also or ) was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It con ...

, where prisoners were murdered.Reutlingen 1930 - 1950; Nationalsozialismus und Nachkriegszeit". hrsg 1995 v.der Stadt Reutlingen, Schul-, Kultur- und Sportamt mit dem Reutlinger Stadtarchiv pp. 159-160.

Post-war period

1946-1947 The U.S. Seventh Army used Hohenasperg as an Internment camp.

In the book, "The Prison Called Hohenasperg", American born and raised author Arthur D. Jacobs provides his experience as a twelve- and thirteen-year-old prisoner in Hohenasperg.

In June 1959

1946-1947 The U.S. Seventh Army used Hohenasperg as an Internment camp.

In the book, "The Prison Called Hohenasperg", American born and raised author Arthur D. Jacobs provides his experience as a twelve- and thirteen-year-old prisoner in Hohenasperg.

In June 1959 Karl Jäger

Karl Jäger (; 20 September 1888 – 22 June 1959) was a German mid-ranking official in the '' SS'' of Nazi Germany and '' Einsatzkommando'' leader who perpetrated acts of genocide during the Holocaust.

Early life and career

Jäger was born in Sc ...

a former Einsatzgruppen

(, ; also ' task forces') were (SS) paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany that were responsible for mass murder, primarily by shooting, during World War II (1939–1945) in German-occupied Europe. The had an integral role in the im ...

officer hung himself in Hohenasperg prison.

Today

The prison later became a civil prison for the detention of non-political prisoners and now also houses the central hospital of the prison service in Baden-Württemberg. The serial killer Heinrich Pommerenke died in Hohenasperg in the central hospital on 27 December 2008. There is a small museum detailing the lives of some of the prison's notable inmates ("Hohenasperg. Ein deutsches Gefängnis").Literature

*M. Biffart: ''Geschichte der württembergischen Feste Hohenasperg und ihrer merkwürdigen Gefangenen''. Stuttgart, 1858 *Theodor Bolay: ''Der Hohenasperg - Vergangenheit und Gegenwart''. Bietigheim, 1972 *Horst Brandstätter: ''Asperg - Ein deutsches Gefängnis'', Berlin: Wagenbachs Taschenbücherei 1978. *Erwin Haas: ''Die sieben württembergischen Landesfestungen Hohenasperg, Hohenneufen, Hohentübingen, Hohenurach, Hohentwiel, Kirchheim/Teck, Schorndorf''. Reutlingen, 1996 *Paul Sauer: ''Der Hohenasperg - Fürstensitz, Höhenburg, Bollwerk der Landesverteidigung.'' Leinfelden-Echterdingen, 2004. *Theodor Schön: ''Die Staatsgefangenen auf Hohenasperg''. Stuttgart, 1899References

*Schön, 1899. ''Die Staatsgefangenen von Hohenasperg''. Stuttgart. *Biffart, 1858. ''Geschichte der Württembergischen Feste Hohenasperg''. Stuttgart.External links

Keltischer Fuerstensitz Hohenasperg

Patrick Nowak & Daniel Behrmann: Asberg - Auschwitz. Der NS-Völkermord an den Sinti und Roma am Beispiel der Pfalz

- Auschwitz.pdf

{{Authority control Prisons in Germany