History Of Wisconsin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Wisconsin encompasses the story not only of the people who have lived in

The first known inhabitants of what is now Wisconsin were Paleo-Indians, who first arrived in the region in about 10,000 BC at the end of the

The first known inhabitants of what is now Wisconsin were Paleo-Indians, who first arrived in the region in about 10,000 BC at the end of the  People of the

People of the

The first European known to have landed in Wisconsin was

The first European known to have landed in Wisconsin was

The British gradually took over Wisconsin during the

The British gradually took over Wisconsin during the

The United States did not firmly exercise control over Wisconsin until the

The United States did not firmly exercise control over Wisconsin until the

The resolution of these Indian conflicts opened the way for Wisconsin's settlement. Many of the region's first settlers were drawn by the prospect of

The resolution of these Indian conflicts opened the way for Wisconsin's settlement. Many of the region's first settlers were drawn by the prospect of

Wisconsin enrolled 91,379 soldiers in the

Wisconsin enrolled 91,379 soldiers in the

Agriculture was a major component of the Wisconsin economy during the 19th century.

Agriculture was a major component of the Wisconsin economy during the 19th century.

Agriculture was not viable in the densely forested northern and central parts of Wisconsin. Settlers came to this region for

Agriculture was not viable in the densely forested northern and central parts of Wisconsin. Settlers came to this region for

Wisconsin was a regional and national model for innovation and organization in the

Wisconsin was a regional and national model for innovation and organization in the

Background on land offices and settlement

''Wisconsin in Three Centuries, 1684-1905''

(4 vols.

1234

1906), highly detailed popular history * Conant, James K. ''Wisconsin Politics And Government: America's Laboratory of Democracy'' (2006) * Current, Richard. ''Wisconsin: A History'' (2001

online

*Current, Richard Nelson. ''History of Wisconsin, Volume 2: The Civil War Era, 1848–1873''. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1976. standard state history * Gara, Larry. ''A Short History of Wisconsin'' (1962) * Glad, Paul W. ''War, a New Era, and Depression, 1914-1940'' (Volume 5 of History of Wisconsin) (1990

excerpt

* Holmes, Fred L. ''Wisconsin'' (5 vols., Chicago, 1946), detailed popular history with many biographies * Klement, Frank L. ''Wisconsin in the Civil War: The Home Front and the Battle Front, 1861-1865''. (State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1997)

online

* Nesbit, Robert C. ''Wisconsin: A History'' (rev. ed. 1989

online

*Nesbit, Robert C. ''The History of Wisconsin, Volume 3: Industrialization and Urbanization 1873–1893''. (Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1973). * Quaife, Milo M. ''Wisconsin, Its History and Its People, 1634-1924'' (4 vols., 1924), detailed popular history & biographies * Raney, William Francis. ''Wisconsin: A Story of Progress'' (1940) * Robinson, A. H. and J. B. Culver, ed., ''The Atlas of Wisconsin'' (1974

online

* Smith, Alice. ''The History of Wisconsin, Volume 1: From Exploration to Statehood''. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1973. * Van Ells, Mark D. ''Wisconsin'' n-The-Road Histories (2009). * Vogeler, Ingolf, et al. ''Wisconsin: A Geography'' (Routledge, 2021

online

* Weber, Ronald E. ''Crane and Hagensick's Wisconsin government and politics'' (2004) rane and Hagensick's Wisconsin government and politics online* ''Wisconsin biographical dictionary: people of all times and all places who have been important to the history and life of the state'' (1991

online

* Wisconsin Cartographers' Guild. ''Wisconsin's Past and Present: A Historical Atlas'' (2002) * Works Progress Administration.

Wisconsin: A Guide to the Badger State

' (1941) detailed guide to every town and city, and cultural history

online

*Braun, John A. ''Together in Christ: A History of the Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod'' (2000) *Brøndal, Jørn. ''Ethnic Leadership and Midwestern Politics: Scandinavian Americans and the Progressive Movement in Wisconsin, 1890–1914.'' (2004) *Butts, Porter. ''Art in Wisconsin'' (1936) *Clark, James I. ''Education in Wisconsin'' (1958) *Cochran, Thomas C. ''The Pabst Brewing Company'' (1948) *Corenthal, Mike ''Illustrated History of Wisconsin Music 1840–1990: 150 Years'' (1991) *Curti, Merle and Carstensen, Vernon. ''The University of Wisconsin: A History'' (2 vols., 1949) *Curti, Merle. ''The Making of an American Community A Case Study of Democracy in a Frontier County'' (1969), in-depth quantitative social history * Fowler, Robert Booth, ''Wisconsin votes : an electoral history'' (2008

online

* Fries, Robert F. ''Empire in Pine: The Story of Lumbering in Wisconsin, 1830–1900'' (1951). *Geib, Paul. "From Mississippi to Milwaukee: A Case Study of the Southern Black Migration to Milwaukee, 1940–1970" ''The Journal of Negro History'', Vol. 83, 199

online

* Gough, Robert J. ''Farming the cutover: A social history of northern Wisconsin, 1900-1940'' (University Press of Kansas, 1997). * Haney, Richard C. ''A history of the Democratic Party of Wisconsin, 1949-1989'' (1989) * Haney, Richard C. ''A concise history of the modern Republican Party of Wisconsin, 1925-1975'' (1976) * Holter, Darryl. "Labor Law and the Road to Taft-Hartley: Wisconsin's Little Wagner Act, 1935-1945." ''Labor studies Journal'' 15 (1990): 20+. *Jensen, Richard ''The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–1896'' (1971

online

*Lampard, Eric E. ''The Rise of the Dairy Industry in Wisconsin'' (1962) * Leahy, Stephen M. ''The Life of Milwaukee's Most Popular Politician, Clement J. Zablocki: Milwaukee Politics and Congressional Foreign Policy'' (Edwin Mellen Press, 2002). * McBride, Genevieve G. ''Women's Wisconsin: From Native Matriarchies to the New Millennium'' (2005

excerpt

*Margulies, Herbert F. ''The Decline of the Progressive Movement in Wisconsin, 1890–1920'' (1968) *Merrill, Horace S. ''William Freeman Vilas: Doctrinaire Democrat'' (1954) Democratic leader in 1880s and 1890s * Olson, Frederick I. ''Milwaukee: At the Gathering of the Waters'' * Ozanne, Robert W. ''The Labor Movement in Wisconsin: A History'' (Wisconsin Historical Society, 2012). * Ostergren, R. C. ''A Community Transplanted: The Trans-Atlantic Experience of a Swedish Immigrant Settlement in the Upper Middle West, 1835-1915'' . (University of Wisconsin Press, 1q988). *Schafer, Joseph.

A History of Agriculture in Wisconsin

' (1922) *Schafer, Joseph.

The Yankee and the Teuton in Wisconsin

. ''Wisconsin Magazine of History'', 6#2 (December 1922), 125–145, compares Yankee and German settlers * Spoolman, Scott. ''Wisconsin Waters: The Ancient History of Lakes, Rivers, and Waterfalls'' (Wisconsin Historical Society, 2022). * Still, Bayrd. ''Milwaukee: The History of a City'' (1948

online

* Teaford, Jon C. ''Cities of the heartland: The rise and fall of the industrial Midwest'' (Indiana University Press, 1993)

online

* Thelen, David. ''Robert M. La Follette and the Insurgent Spirit'' (1976) * Thompson, William F. ''The History of Wisconsin: Volume 6: Continuity and Change 1940-1965''. Madison: State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 1988. * Unger, Nancy C. ''Fighting Bob La Follette: The Righteous Reformer'' (2000) * WPA. ''The WPA guide to Wisconsin'' (1939) reprint of the Federal Writers' Project guide to 1930's Wisconsin

online

full text of many primary source books *''The Badger State: A documentary history of Wisconsin'' (1979)

La Follette's Autobiography, a personal narrative of political experiences, 1913

''Wisconsin Magazine of History'' archive of scholarly articles, Free access

"Turning Points in Wisconsin History" from the Wisconsin Historical Society

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Wisconsin

Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

since it became a state of the U.S., but also that of the Native American tribes who made their homeland in Wisconsin, the French and British colonists who were the first Europeans to live there, and the American settlers who lived in Wisconsin when it was a territory.

Since its admission to the Union on May 29, 1848, as 30th state, Wisconsin has been ethnically heterogeneous, with Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Its various senses depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, residents of the Northern United St ...

s being among the first to arrive from New York and New England. They dominated the state's heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

, finance, politics and education. Large numbers of European immigrants followed them, including German American

German Americans (german: Deutschamerikaner, ) are Americans who have full or partial German ancestry. With an estimated size of approximately 43 million in 2019, German Americans are the largest of the self-reported ancestry groups by the Unite ...

s, mostly between 1850 and 1900, Scandinavians (the largest group being Norwegian Americans

Norwegian Americans ( nb, Norskamerikanere, nn, Norskamerikanarar) are Americans with ancestral roots in Norway. Norwegian immigrants went to the United States primarily in the latter half of the 19th century and the first few decades of the ...

) and smaller groups of Belgian American

Belgian Americans are Americans who can trace their ancestry to people from Belgium who immigrated to the United States. While the first natives of the then-Southern Netherlands arrived in America in the 17th century, the majority of Belgian immi ...

s, Dutch American

Dutch Americans ( nl, Nederlandse Amerikanen) are Americans of Dutch descent whose ancestors came from the Netherlands in the recent or distant past. Dutch settlement in the Americas started in 1613 with New Amsterdam, which was exchanged with ...

s, Swiss American

Swiss Americans are Americans of Swiss descent.

Swiss emigration to America predates the formation of the United States, notably in connection with the persecution of Anabaptism during the Swiss Reformation and the formation of the Amish commun ...

s, Finnish American

Finnish Americans ( fi, amerikansuomalaiset, ) comprise Americans with ancestral roots from Finland or Finnish people who immigrated to and reside in the United States. The Finnish-American population numbers a little bit more than 650,000. Man ...

s, Irish American

, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption = Irish Americans, % of population by state

, caption = Notable Irish Americans

, population =

36,115,472 (10.9%) alone ...

s and others; in the 20th century, large numbers of Polish American

Polish Americans ( pl, Polonia amerykańska) are Americans who either have total or partial Polish ancestry, or are citizens of the Republic of Poland. There are an estimated 9.15 million self-identified Polish Americans, representing about 2.83 ...

s and African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

s came, settling mainly in Milwaukee.

Politically the state was predominantly Republican until recent years, when it became more evenly balanced. The state took a national leadership role in the Progressive Movement

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techno ...

, under the aegis of Robert M. La Follette Sr.

Robert Marion "Fighting Bob" La Follette Sr. (June 14, 1855June 18, 1925), was an American lawyer and politician. He represented Wisconsin in both chambers of Congress and served as the 20th Governor of Wisconsin. A Republican for most of his ...

and his family, who fought the old guard bitterly at the state and national levels. The "Wisconsin Idea

The Wisconsin Idea is a public philosophy that has influenced policy and Ideal (ethics), ideals in the Wisconsin, U.S. state of Wisconsin's education system and politics.

In education, emphasis is often placed on how the Idea articulates educa ...

" called for the use of the higher learning in modernizing government, and the state is notable for its strong network of state universities.

Pre-Columbian history

The first known inhabitants of what is now Wisconsin were Paleo-Indians, who first arrived in the region in about 10,000 BC at the end of the

The first known inhabitants of what is now Wisconsin were Paleo-Indians, who first arrived in the region in about 10,000 BC at the end of the Ice Age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

. The retreating glaciers left behind a tundra in Wisconsin inhabited by large animals, such as mammoth

A mammoth is any species of the extinct elephantid genus ''Mammuthus'', one of the many genera that make up the order of trunked mammals called proboscideans. The various species of mammoth were commonly equipped with long, curved tusks and, ...

s, mastodon

A mastodon ( 'breast' + 'tooth') is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus ''Mammut'' (family Mammutidae). Mastodons inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of th ...

s, bison

Bison are large bovines in the genus ''Bison'' (Greek: "wild ox" (bison)) within the tribe Bovini. Two extant and numerous extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American bison, ''B. bison'', found only in North Ame ...

, giant beaver, and muskox

The muskox (''Ovibos moschatus'', in Latin "musky sheep-ox"), also spelled musk ox and musk-ox, plural muskoxen or musk oxen (in iu, ᐅᒥᖕᒪᒃ, umingmak; in Woods Cree: ), is a hoofed mammal of the family Bovidae. Native to the Arctic, i ...

. The Boaz mastodon

The Boaz mastodon is the skeleton of a mastodon found near Boaz, Wisconsin, USA, in 1897. A fluted quartzite spear point found near the Boaz mastodon suggests that humans hunted mastodons in southwestern Wisconsin. It is currently on display at the ...

and the Clovis artifacts discovered in Boaz, Wisconsin

Boaz is a village in Richland County, Wisconsin, United States. According to the 2010 census, the population of the village was 156.

Geography

Boaz is located at (43.330793, -90.527280).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the villag ...

show that the Paleo-Indians hunted these large animals. They also gathered plants as conifer forests grew in the glaciers' wake. With the decline and extinction of many large mammals in the Americas, the Paleo-Indian diet shifted toward smaller mammals like deer and bison.

During the Archaic Period, from 6000 to 1000 BC, mixed conifer-hardwood forests as well as mixed prairie-forests replaced Wisconsin's conifer forests. People continued to depend on hunting and gathering. Around 4000 BC they developed spear-thrower

A spear-thrower, spear-throwing lever or ''atlatl'' (pronounced or ; Nahuatl ''ahtlatl'' ) is a tool that uses leverage to achieve greater velocity in dart or javelin-throwing, and includes a bearing surface which allows the user to store ene ...

s and copper tools such as axes, adze

An adze (; alternative spelling: adz) is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing ...

s, projectile points, knives, perforators, fishhooks and harpoons. Copper ornaments like beaded necklaces also appeared around 1500 BC. These people gathered copper ore at quarries on the Keweenaw Peninsula

The Keweenaw Peninsula ( , sometimes locally ) is the northernmost part of Michigan's Upper Peninsula. It projects into Lake Superior and was the site of the first copper boom in the United States, leading to its moniker of "Copper Country." As o ...

in Michigan and on Isle Royale

Isle Royale National Park is an American national park consisting of Isle Royale – known as Minong to the native Ojibwe – along with more than 400 small adjacent islands and the surrounding waters of Lake Superior, in the state of Michigan ...

in Lake Superior. They may have crafted copper artifacts by hammering and folding the metal and also by heating it to increase its malleability. However it is not certain if these people reached the level of copper smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat to ore, to extract a base metal. It is a form of extractive metallurgy. It is used to extract many metals from their ores, including silver, iron, copper, and other base metals. Smelting uses heat and a ch ...

. Regardless, the Copper Culture of the Great Lakes region reached a level of sophistication unprecedented in North America. The Late Archaic Period also saw the emergence of cemeteries and ritual burials, such as the one in Oconto.

The Early Woodland Period

In the classification of :category:Archaeological cultures of North America, archaeological cultures of North America, the Woodland period of North American pre-Columbian cultures spanned a period from roughly 1000 Common Era, BCE to European con ...

began in 1000 BC as plants became an increasingly important part of the people's diet. Small scale agriculture and pottery arrived in southern Wisconsin at this time. The primary crops were maize, beans and squash. Agriculture, however, could not sufficiently support these people, who also had to hunt and gather. Agriculture at this time was more akin to gardening than to farming. Villages emerged along rivers, streams and lakes, and the earliest earthen burial mounds were constructed. The Havana Hopewell culture

The Havana Hopewell culture were a Hopewellian people who lived in the Illinois River and Mississippi River valleys in Iowa, Illinois, and Missouri from 200 BCE to 400 CE.

Hopewell Interaction Sphere

The Hopewell Exchange system began in the Ohi ...

arrived in Wisconsin in the Middle Woodland Period, settling along the Mississippi River. The Hopewell people connected Wisconsin to their trade practices, which stretched from Ohio to Yellowstone and from Wisconsin to the Gulf of Mexico. They constructed elaborate mounds, made elaborately decorated pottery and brought a wide range of traded minerals to the area. The Hopewell people may have influenced the other inhabitants of Wisconsin, rather than displacing them. The Late Woodland Period began in about 400 AD, following the disappearance of the Hopewell culture from the area. The people of Wisconsin first used the bow and arrow

The bow and arrow is a ranged weapon system consisting of an elastic launching device (bow) and long-shafted projectiles ( arrows). Humans used bows and arrows for hunting and aggression long before recorded history, and the practice was comm ...

in the final centuries of the Woodland Period, and agriculture continued to be practiced in the southern part of the state. The effigy mound

An effigy mound is a raised pile of earth built in the shape of a stylized animal, symbol, religious figure, human, or other figure. The Effigy Moundbuilder culture is primarily associated with the years 550-1200 CE during the Late Woodland Peri ...

culture dominated Southern Wisconsin during this time, building earthen mounds in the shapes of animals. Unlike earlier mounds, many of these were not used for burials. Examples of effigy mounds still exist at High Cliff State Park

High Cliff State Park is a Wisconsin state park near Sherwood, Wisconsin. It is the only state-owned recreation area located on Lake Winnebago. The park got its name from cliffs of the Niagara Escarpment, a land formation east of the shore of L ...

and at Lizard Mound County Park

Lizard Mound State Park is a state park in the Town of Farmington, Washington County, Wisconsin near the city of West Bend. Established in 1950, it was acquired by Washington County from the state of Wisconsin in 1986. It contains a significant ...

. In northern Wisconsin people continued to survive on hunting and gathering, and constructed conical mounds.

People of the

People of the Mississippian culture

The Mississippian culture was a Native Americans in the United States, Native American civilization that flourished in what is now the Midwestern United States, Midwestern, Eastern United States, Eastern, and Southeastern United States from appr ...

expanded into Wisconsin around 1050 AD and established a settlement at Aztalan

Aztalan State Park is a Wisconsin state park in the Town of Aztalan, Jefferson County. Established in 1952, it was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966. The park cover ...

along the Crawfish River

The Crawfish River is a tributary of the Rock River, long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed May 13, 2011 in south-central Wisconsin in the United States. Via the Rock Riv ...

. While begun by the Caddoan people, other cultures began to borrow & adapt the Mississippian cultural structure. This elaborately planned site may have been the northernmost outpost of Cahokia

The Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site ( 11 MS 2) is the site of a pre-Columbian Native American city (which existed 1050–1350 CE) directly across the Mississippi River from modern St. Louis, Missouri. This historic park lies in south-w ...

, although it is also now known that some Siouan peoples along the Mississippi River may have taken part in the culture as well. Regardless, the Mississippian site traded with and was clearly influenced in its civic and defensive planning, as well as culturally, by its much larger southern neighbor. A rectangular wood-and-clay stockade surrounded the twenty acre site, which contained two large earthen mounds and a central plaza. One mound may have been used for food storage, as a residence for high-ranking officials, or as a temple, and the other may have been used as a mortuary. The Mississippian culture cultivated maize intensively, and their fields probably stretched far beyond the stockade at Aztalan, although modern agriculture has erased any traces of Mississippian practices in the area. Some rumors also speculate that the people of Aztalan may have experimented slightly with stone architecture in the making of a man-made, stone-line pond, at the very least. While the first settler on the land of what is now the city supposedly reported this, he filled it in and it has yet to be rediscovered.

Both Woodland and Mississippian peoples inhabited Aztalan, which was connected to the extensive Mississippian trade network. Shells from the Gulf of Mexico, copper from Lake Superior and Mill Creek chert

Mill Creek chert is a type of chert found in Southern Illinois and heavily exploited by members of the Mississippian culture (800 to 1600 CE). Artifacts made from this material are found in archaeological sites throughout the American Midwest and ...

have been found at the site. Aztalan was abandoned around 1200 AD. The Oneota

Oneota is a designation archaeologists use to refer to a cultural complex that existed in the eastern plains and Great Lakes area of what is now occupied by the United States from around AD 900 to around 1650 or 1700. Based on classification de ...

people later built agriculturally based villages, similar to those of the Mississippians but without the extensive trade networks, in the state.

By the time the first Europeans arrived in Wisconsin, the Oneota had disappeared. The historically documented inhabitants, as of the first European incursions, were the Siouan speaking Dakota Oyate to the northwest, the Chiwere

Chiwere (also called Iowa-Otoe-Missouria or Báxoje-Jíwere-Ñút'achi) is a Siouan language originally spoken by the Missouria, Otoe, and Iowa peoples, who originated in the Great Lakes region but later moved throughout the Midwest and plains. T ...

speaking Ho-Chunk

The Ho-Chunk, also known as Hoocągra or Winnebago (referred to as ''Hotúŋe'' in the neighboring indigenous Iowa-Otoe language), are a Siouan-speaking Native American people whose historic territory includes parts of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iow ...

(Winnebago) and he Algonquian Menominee

The Menominee (; mez, omǣqnomenēwak meaning ''"Menominee People"'', also spelled Menomini, derived from the Ojibwe language word for "Wild Rice People"; known as ''Mamaceqtaw'', "the people", in the Menominee language) are a federally recog ...

to the northeast, with their lands beginning approximately north of Green Bay. The Chiwere lands were south of Green Bay and followed rivers to the southwest. Over time, other tribes moved to Wisconsin, including the Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

, the Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, the Fauk, the Sauk and the Mahican

The Mohican ( or , alternate spelling: Mahican) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that historically spoke an Algonquian language. As part of the Eastern Algonquian family of tribes, they are related to the neighboring Lenape, who ...

. The Mahican were one of the last groups to arrived, coming from New York after the U.S. congress passed the Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act was signed into law on May 28, 1830, by United States President Andrew Jackson. The law, as described by Congress, provided "for an exchange of lands with the Indians residing in any of the states or territories, and for ...

of 1830.

Exploration and colonization

French period

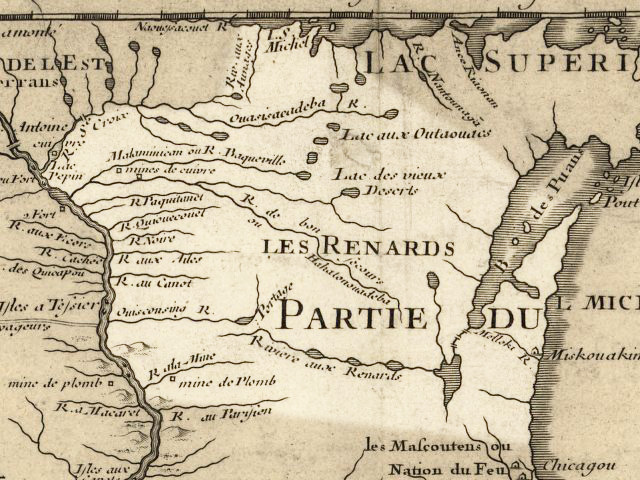

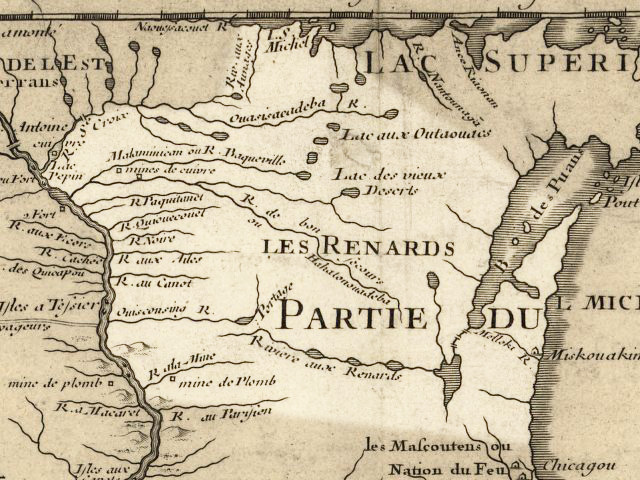

The first European known to have landed in Wisconsin was

The first European known to have landed in Wisconsin was Jean Nicolet

Jean Nicolet (Nicollet), Sieur de Belleborne (October 1642) was a French '' coureur des bois'' noted for exploring Lake Michigan, Mackinac Island, Green Bay, and being the first European to set foot in what is now the U.S. state of Wisconsin.

...

. In 1634, Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (; Fichier OrigineFor a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see RitchThe baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth. – 25 December 1635) was a Fre ...

, governor of New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

, sent Nicolet to contact the Ho-Chunk people, make peace between them and the Huron

Huron may refer to:

People

* Wyandot people (or Wendat), indigenous to North America

* Wyandot language, spoken by them

* Huron-Wendat Nation, a Huron-Wendat First Nation with a community in Wendake, Quebec

* Nottawaseppi Huron Band of Potawatomi ...

and expand the fur trade

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mos ...

, and possibly to also find a water route to Asia. Accompanied by seven Huron guides, Nicolet left New France and canoed through Lake Huron

Lake Huron ( ) is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. Hydrology, Hydrologically, it comprises the easterly portion of Lake Michigan–Huron, having the same surface elevation as Lake Michigan, to which it is connected by the , Strait ...

and Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

, and then became the first European known to have entered Lake Michigan

Lake Michigan is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is the second-largest of the Great Lakes by volume () and the third-largest by surface area (), after Lake Superior and Lake Huron. To the east, its basin is conjoined with that o ...

. Nicolet proceeded into Green Bay, which he named ''La Baie des Puants'' (literally "The Stinking Bay"), and probably came ashore near the Red Banks. He made contact with the Ho-Chunk and Menominee living in the area and established peaceful relations. Nicolet remained with the Ho-Chunk the winter before he returned to Quebec.

The Beaver Wars

The Beaver Wars ( moh, Tsianì kayonkwere), also known as the Iroquois Wars or the French and Iroquois Wars (french: Guerres franco-iroquoises) were a series of conflicts fought intermittently during the 17th century in North America throughout t ...

fought between the Iroquois and the French prevented French explorers from returning to Wisconsin until 1652–1654, when Pierre Radisson

Pierre-Esprit Radisson (1636/1640–1710) was a French fur trader and explorer in New France. He is often linked to his brother-in-law Médard des Groseilliers. The decision of Radisson and Groseilliers to enter the English service led to the fo ...

and Médard des Groseilliers

Médard Chouart des Groseilliers (1618–1696) was a French explorer and fur trader in Canada. He is often paired with his brother-in-law Pierre-Esprit Radisson, who was about 20 years younger. The pair worked together in fur trading and explora ...

arrived at ''La Baie des Puants'' to trade furs. They returned to Wisconsin in 1659–1660, this time at Chequamegon Bay

Chequamegon Bay ( ) is an inlet of Lake Superior in Ashland and Bayfield counties in the extreme northern part of Wisconsin.

History

A Native American village, known as ''Chequamegon'', developed here in the mid-17th century. It was developed b ...

on Lake Superior. On their second voyage they found that the Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

had expanded into northern Wisconsin, as they continued to prosper in the fur trade. They also were the first Europeans to contact the Santee Dakota. They built a trading post and wintered near Ashland, before returning to Montreal.

In 1665 Claude-Jean Allouez

Claude Jean Allouez (June 6, 1622 – August 28, 1689) was a Jesuit missionary and French explorer of North America. He established a number of missions among the indigenous people living near Lake Superior.

Biography

Allouez was born in Sai ...

, a Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionary, built a mission on Lake Superior. Five years later he abandoned the mission, and journeyed to ''La Baie des Puants''. Two years later he built St. Francis Xavier Mission

The mission of St. Francis Xavier was a seventeenth-century Jesuit mission located on the rapids of the Fox River near De Pere, Wisconsin.

It was founded in 1671 by Claude Allouez to proselytize the native peoples of the western Great Lakes. In ...

near present-day De Pere

De Pere ( ) is a city located in Brown County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 25,410 according to the 2020 Census. De Pere is part of the Green Bay Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

At the arrival of the first European, J ...

. In his journeys through Wisconsin, he encountered groups of Native Americans who had been displaced by Iroquois in the Beaver Wars. He evangelized the Algonquin-speaking Potawatomi

The Potawatomi , also spelled Pottawatomi and Pottawatomie (among many variations), are a Native American people of the western Great Lakes region, upper Mississippi River and Great Plains. They traditionally speak the Potawatomi language, a m ...

, who had settled on the Door Peninsula

The Door Peninsula is a peninsula in eastern Wisconsin, separating the southern part of the Green Bay (Lake Michigan), Green Bay from Lake Michigan. The peninsula includes northern Kewaunee County, Wisconsin, Kewaunee County, northeaster ...

after fleeing Iroquois attacks in Michigan. He also encountered the Algonquin-speaking Sauk, who had been forced into Michigan by the Iroquois, and then had been forced into central Wisconsin by the Ojibwe and the Huron.

The next major expedition into Wisconsin was that of Father Jacques Marquette

Jacques Marquette S.J. (June 1, 1637 – May 18, 1675), sometimes known as Père Marquette or James Marquette, was a French Jesuit missionary who founded Michigan's first European settlement, Sault Sainte Marie, and later founded Saint Igna ...

and Louis Jolliet

Louis Jolliet (September 21, 1645after May 1700) was a French-Canadian explorer known for his discoveries in North America. In 1673, Jolliet and Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit Catholic priest and missionary, were the first non-Natives to explore an ...

in 1673. After hearing rumors from Indians telling of the existence of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, Marquette and Joliet set out from St. Ignace

St. Ignace is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan and the county seat of Mackinac County. The city had a population of 2,452 at the 2010 census. St. Ignace Township is located just to the north of the city, but the two are administered auto ...

, in what is now Michigan, and entered the Fox River at Green Bay. They canoed up the Fox until they reached the river's westernmost point, and then portaged, or carried their boats, to the nearby Wisconsin River

The Wisconsin River is a tributary of the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. At approximately 430 miles (692 km) long, it is the state's longest river. The river's name, first recorded in 1673 by Jacques Marquette as "Meskousi ...

, where they resumed canoeing downstream to the Mississippi River. Marquette and Joliet reached the Mississippi near what is now Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin

Prairie du Chien () is a city in and the county seat of Crawford County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 5,506 at the 2020 census. Its ZIP Code is 53821.

Often referred to as Wisconsin's second oldest city, Prairie du Chien was esta ...

in June, 1673.

Nicolas Perrot

Nicolas Perrot (–1717), a French explorer, fur trader, and diplomat, was one of the first European men to travel in the Upper Mississippi Valley, in what is now Wisconsin and Minnesota.

Biography

Nicolas Perrot was born in France between 1641 ...

, French commander of the west, established Fort St. Nicholas at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin in May, 1685, near the southwest end of the Fox-Wisconsin Waterway. Perrot also built a fort on the shores of Lake Pepin

Lake Pepin is a naturally occurring lake on the Mississippi River on the border between the U.S. states of Minnesota and Wisconsin. It is located in a valley carved by the outflow of an enormous glacial lake at the end of the last Ice Age. The ...

called Fort St. Antoine in 1686, and a second fort, called Fort Perrot, on an island on Lake Peppin shortly after. In 1727, Fort Beauharnois

Fort Beauharnois was a French fort, serving as a fur trading post and Catholic mission, built on the shores of Lake Pepin, a wide section of the upper Mississippi River, in 1727. The location chosen was on lowlands and the fort was rebuilt in 17 ...

was constructed on what is now the Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

side of Lake Pepin to replace the two previous forts. A fort and a Jesuit mission were also built on the shores of Lake Superior

Lake Superior in central North America is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface areaThe Caspian Sea is the largest lake, but is saline, not freshwater. and the third-largest by volume, holding 10% of the world's surface fresh wa ...

at La Pointe, in present-day Wisconsin, in 1693 and operated until 1698. A second fort was built on the same site in 1718 and operated until 1759. These were not military posts, but rather small storehouses for furs.

During the French colonial period, the first black people came to Wisconsin. The first record of a black person comes from 1725, when a black slave was killed along with four Frenchmen in a Native American raid on Green Bay. Other French fur traders and military personnel brought slaves with them to Wisconsin later in 1700s.

None of the French posts had permanent settlers; fur traders and missionaries simply visited them from time to time to conduct business.

The Second Fox War

In the 1720s, the anti-FrenchFox tribe

The Meskwaki (sometimes spelled Mesquaki), also known by the European exonyms Fox Indians or the Fox, are a Native American people. They have been closely linked to the Sauk people of the same language family. In the Meskwaki language, the ...

, led by war chief Kiala, raided French settlements on the Mississippi River and disrupted French trade on Lake Michigan. From 1728 to 1733, the Fox fought against the French-supported Potawatomi, Ojibwa, Huron and Ottawa tribes. In 1733, Kiala was captured and sold into slavery in the West Indies

The West Indies is a subregion of North America, surrounded by the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea that includes 13 independent island countries and 18 dependencies and other territories in three major archipelagos: the Greater A ...

along with other captured Fox.

Before the war, the Fox tribe numbered 1500, but by 1733, only 500 Fox were left. As a result, the Fox joined the Sauk people

The Sauk or Sac are a group of Native Americans of the Eastern Woodlands culture group, who lived primarily in the region of what is now Green Bay, Wisconsin, when first encountered by the French in 1667. Their autonym is oθaakiiwaki, and th ...

.

The details are unclear, but this war appears to have been part of the conflict that expelled the Dakota & Illinois peoples out onto the Great Plains, causing further displacement of other Chiwere, Caddoan & Algonquian peoples there—including the ancestors of the Ioway

The Iowa, also known as Ioway, and the Bah-Kho-Je or Báxoje (English: grey snow; Chiwere: Báxoje ich'é) are a Native American Siouan people. Today, they are enrolled in either of two federally recognized tribes, the Iowa Tribe of Oklahoma and ...

, Osage The Osage Nation, a Native American tribe in the United States, is the source of most other terms containing the word "osage".

Osage can also refer to:

* Osage language, a Dhaegin language traditionally spoken by the Osage Nation

* Osage (Unicode b ...

, Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska

* ...

, Arikara

Arikara (), also known as Sahnish,

''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

, A'ani, ''Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation.'' (Retrieved Sep 29, 2011)

Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

, Hidatsa

The Hidatsa are a Siouan people. They are enrolled in the federally recognized Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation in North Dakota. Their language is related to that of the Crow, and they are sometimes considered a parent t ...

, Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

& Blackfoot

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'' or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Bla ...

.

The British period

The British gradually took over Wisconsin during the

The British gradually took over Wisconsin during the French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the ...

, taking control of Green Bay in 1761, gaining control of all of Wisconsin in 1763, and annexing the area to the Province of Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirteen p ...

in 1774. Like the French, the British were interested in little but the fur trade. One notable event in the fur trading industry in Wisconsin occurred in 1791, when two free African Americans set up a fur trading post among the Menominee at present day Marinette. The first permanent settlers, mostly French Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fren ...

s, some Anglo-New Englanders and a few African American freedmen, arrived in Wisconsin while it was under British control. Charles Michel de Langlade

Charles Michel Mouet de Langlade (9 May 1729 – after 26 July 1801)''Dictionnaire Généalogique Tanguay'' was a Great Lakes fur trader and war chief who was important in protecting French territory in North America. His mother was Ottawa and hi ...

is generally recognized as the first settler, establishing a trading post at Green Bay in 1745, and moving there permanently in 1764. In 1766 the Royal Governor of the new territory, Robert Rogers Robert Rogers may refer to:

Politics

* Robert Rogers (Irish politician) (died 1719), Irish politician, MP for Cork City 1692–1699

*Robert Rogers (Manitoba politician) (1864–1936), Canadian politician

* Robert Rogers, Baron Lisvane (born 1950), ...

, engaged Jonathan Carver

Jonathan Carver (April 13, 1710 – January 31, 1780) was a captain in a Massachusetts colonial unit, explorer, and writer. After his exploration of the northern Mississippi valley and western Great Lakes region, he published an account of his exp ...

to explore and map the newly acquired territories for the Crown, and to search for a possible Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

. Carver left Fort Michilimackinac

Fort Michilimackinac was an 18th-century French, and later British, fort and trading post at the Straits of Mackinac; it was built on the northern tip of the lower peninsula of the present-day state of Michigan in the United States. Built arou ...

that spring and spent the next three years exploring and mapping what is now Wisconsin and parts of Minnesota.

Settlement began at Prairie du Chien around 1781. The French residents at the trading post in what is now Green Bay, referred to the town as "La Bey", however British fur traders referred to it as "Green Bay", because the water and the shore assumed green tints in early spring. The old French title was gradually dropped, and the British name of "Green Bay" eventually stuck. The region coming under British rule had virtually no adverse effect on the French residents as the British needed the cooperation of the French fur traders and the French fur traders needed the goodwill of the British. During the French occupation of the region licenses for fur trading had been issued scarcely and only to select groups of traders, whereas the British, in an effort to make as much money as possible from the region, issued licenses for fur trading freely, both to British and French residents. The fur trade in what is now Wisconsin reached its height under British rule, and the first self-sustaining farms in the state were established at this time as well. From 1763 to 1780, Green Bay was a prosperous community which produced its own foodstuff, built graceful cottages and held dances and festivities.

The territorial period

The United States acquired Wisconsin in theTreaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of George III, King George III of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and representatives of the United States, United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the Ame ...

. Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

claimed the territory east of the Mississippi River between the present-day Wisconsin-Illinois border and present-day La Crosse, Wisconsin

La Crosse is a city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of La Crosse County. Positioned alongside the Mississippi River, La Crosse is the largest city on Wisconsin's western border. La Crosse's population as of the 2020 census w ...

. Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

claimed the territory north of La Crosse to Lake Superior and all of present-day Minnesota east of the Mississippi River. Shortly afterward, in 1787, the Americans made Wisconsin part of the new Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. Later, in 1800, Wisconsin became part of Indiana Territory

The Indiana Territory, officially the Territory of Indiana, was created by a United States Congress, congressional act that President of the United States, President John Adams signed into law on May 7, 1800, to form an Historic regions of the U ...

. Despite the fact that Wisconsin belonged to the United States at this time, the British continued to control the local fur trade and maintain military alliances with Wisconsin Indians in an effort to stall American expansion westward by creating a pro-British Indian barrier state

The Indian barrier state or buffer state was a British proposal to establish a Native American state in the portion of the Great Lakes region of North America. It was never created. The idea was to create it west of the Appalachian Mountains, b ...

.

The War of 1812 and the Indian wars

The United States did not firmly exercise control over Wisconsin until the

The United States did not firmly exercise control over Wisconsin until the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

. In 1814, the Americans built Fort Shelby at Prairie du Chien. During the war, the Americans and British fought one battle in Wisconsin, the July, 1814 Siege of Prairie du Chien

The siege of Prairie du Chien was a British victory in the far western theater of the War of 1812. During the war, Prairie du Chien was a small frontier settlement with residents loyal to both American and British causes. By 1814, both nations w ...

, which ended as a British victory. The British captured Fort Shelby and renamed it Fort McKay, after Major William McKay

Lt.-Colonel William McKay (1772 – 18 August 1832) is remembered for leading the Canada, Canadian Forces to victory at the Siege of Prairie du Chien during the War of 1812. After the war, he was appointed Indian Department, Superintendent o ...

, the British commander who led the forces that won the Battle of Prairie du Chien. However, the 1815 Treaty of Ghent

The Treaty of Ghent () was the peace treaty that ended the War of 1812 between the United States and the United Kingdom. It took effect in February 1815. Both sides signed it on December 24, 1814, in the city of Ghent, United Netherlands (now in ...

reaffirmed American jurisdiction over Wisconsin, which was by then a part of Illinois Territory

The Territory of Illinois was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 1, 1809, until December 3, 1818, when the southern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Illinois. Its ca ...

. Following the treaty, British troops burned Fort McKay, rather than giving it back to the Americans, and departed Wisconsin. To protect Prairie du Chien from future attacks, the United States Army constructed Fort Crawford

Fort Crawford was an outpost of the United States Army located in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, during the 19th century.

The army's occupation of Prairie du Chien spanned the existence of two fortifications, both of them named Fort Crawford. The ...

in 1816, on the same site as Fort Shelby. Fort Howard was also built in 1816 in Green Bay.

Significant American settlement in Wisconsin, a part of Michigan Territory

The Territory of Michigan was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 30, 1805, until January 26, 1837, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Michigan. Detroit w ...

beginning in 1818, was delayed by two Indian wars, the minor Winnebago War

The Winnebago War, also known as the Winnebago Uprising, was a brief conflict that took place in 1827 in the Upper Mississippi River region of the United States, primarily in what is now the state of Wisconsin. Not quite a war, the hostilities ...

of 1827 and the larger Black Hawk War

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", crosse ...

of 1832.

The Winnebago War

The Winnebago War started when, in 1826, two Winnebago men were detained at Fort Crawford on charges of murder and then transferred toFort Snelling

Fort Snelling is a former military fortification and National Historic Landmark in the U.S. state of Minnesota on the bluffs overlooking the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. The military site was initially named Fort Saint Anth ...

in present-day Minnesota. The Winnebago in the area believed that both men had been executed. On June 27, 1827, a Winnebago war band led by Chief Red Bird

Red Bird (–16 February 1828) was a leader of the Winnebago (or Ho-Chunk) Native American tribe. He was a leader in the Winnebago War of 1827 against Americans in the United States making intrusions into tribal lands for mining. He was f ...

and the prophet White Cloud (Wabokieshiek) attacked a family of settlers outside of Prairie du Chien, killing two. They then went on to attack two keel-boats on the Mississippi River that were heading toward Fort Snelling, killing two settlers and injuring four more. Seven Winnebago warriors were killed in those attacks. The war band also attacked settlers on the lower Wisconsin River and the lead mines at Galena, Illinois

Galena is the largest city in and the county seat of Jo Daviess County, Illinois, with a population of 3,308 at the 2020 census. A section of the city is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Galena Historic District. The ci ...

. The war band surrendered at Portage, Wisconsin

Portage is a city in and the county seat of Columbia County, Wisconsin, Columbia County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 10,581 at the 2020 census making it the largest city in Columbia County. The city is part of the Madison, Wiscon ...

, rather than fighting the United States Army that was pursuing them.

The Black Hawk War

In the Black Hawk War, Sac, Fox, and Kickapoo Native Americans, otherwise known as the British Band, led byChief Black Hawk

Black Hawk, born ''Ma-ka-tai-me-she-kia-kiak'' (Sauk: ''Mahkatêwe-meshi-kêhkêhkwa'') (1767 – October 3, 1838), was a Sauk leader and warrior who lived in what is now the Midwestern United States. Although he had inherited an important his ...

, who had been relocated from Illinois to Iowa, attempted to resettle in their Illinois homeland on April 5, 1832, in violation of Treaty. On May 10 Chief Black Hawk decided to go back to Iowa. On May 14, Black Hawk's forces met with a group of militiamen led by Isaiah Stillman

Isaiah Stillman (1793–15 April 1861) was an American Cavalry Major who led the Illinois militia in the first armed confrontation of the Black Hawk War against Black Hawk's Sauk Indian Band. The first armed confrontation would be named Bat ...

. All three members of Black Hawk's parley were shot and one was killed. The Battle of Stillman's Run

The Battle of Stillman's Run, also known as the Battle of Sycamore Creek or the Battle of Old Man's Creek, occurred in Illinois on May 14, 1832. The battle was named for the panicked retreat by Major Isaiah Stillman and his detachment of 275 Ill ...

ensued, leaving twelve militiamen and three to five Sac and Fox warriors dead. Of the fifteen battles of the war, six took place in Wisconsin. The other nine as well as several smaller skirmishes took place in Illinois. The first confrontation to take place in Wisconsin was the first attack on Fort Blue Mounds on June 6, in which one member of the local militia was killed outside of the fort. There was also the Spafford Farm Massacre on June 14, the Battle of Horseshoe Bend

The Battle of Horseshoe Bend (also known as ''Tohopeka'', ''Cholocco Litabixbee'', or ''The Horseshoe''), was fought during the War of 1812 in the Mississippi Territory, now central Alabama. On March 27, 1814, United States forces and Indian a ...

on June 16, which was a United States victory, the second attack on Fort Blue Mounds on June 20, and the Sinsinawa Mound raid

The Sinsinawa Mound raid occurred on June 29, 1832, near the Sinsinawa mining settlement in Michigan Territory (present-day Grant County, Wisconsin in the United States). This incident, part of the Black Hawk War, resulted in the deaths of two ...

on June 29. The Native Americans were defeated at the Battle of Wisconsin Heights

The Battle of Wisconsin Heights was the penultimate engagement of the 1832 Black Hawk War, fought between the United States state militia and allies, and the Sauk and Fox tribes, led by Black Hawk. The battle took place in what is now Dane Coun ...

on July 21, with forty to seventy killed and only one killed on the United States side. The Ho Chunk Nation fought on the side of the United States. The Black Hawk War ended with the Battle of Bad Axe on August 1–2, with over 150 of the British Band dead and 75 captured and only five killed in the United States forces. Those crossing the Mississippi were killed by Lakota, American and Ho Chunk Forces. Many of the British Band survivors were handed over to the United States on August 20 by the Lakota Tribe, with the exception of Black Hawk, who had retreated into Vernon County, Wisconsin and White Cloud, who surrendered on August 27, 1832. Black Hawk was captured by Decorah south of Bangor, Wisconsin, south of the headwaters of the La Crosse River. He was then sold to the U.S. military at Prairie du Chien, accepted by future Confederate president, Stephen Davis, who was a soldier at the time. Black Hawk's tribe had killed his daughter. Black Hawk moved back to Iowa in 1833, after being held prisoner by the United States government.

Territorial settlement

lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb (from the Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a heavy metal that is denser than most common materials. Lead is soft and malleable, and also has a relatively low melting point. When freshly cu ...

mining in southwest Wisconsin. This area had traditionally been mined by Native Americans. However, after a series of treaties removed the Indians, the lead mining region was opened to white miners. Thousands rushed in from across the country to dig for the "gray gold". By 1829, 4,253 miners and 52 licensed smelting works were in the region. Expert miners from Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlantic ...

in Britain informed a large part of the wave of immigrants. Boom towns like Mineral Point, Platteville, Shullsburg, Belmont, and New Diggings sprang up around mines. The first two federal land offices in Wisconsin were opened in 1834 at Green Bay and at Mineral Point. By the 1840s, southwest Wisconsin mines were producing more than half of the nation's lead, which was no small amount, as the United States was producing annually some 31 million pounds of lead. Wisconsin was dubbed the "Badger State" because of the lead miners who first settled there in the 1820s and 1830s. Without shelter in the winter, they had to "live like badgers" in tunnels burrowed into hillsides.

Although the lead mining area drew the first major wave of settlers, its population would soon be eclipsed by growth in Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

. Milwaukee, along with Sheboygan, Manitowoc, and Kewaunee, can be traced back to a series of trading posts established by the French trader Jacques Vieau

Jacques Le Vieux, dit Vieau (or Vieaux) (May 5, 1757 – July 1, 1852) was a French-Canadian fur trader and the first permanent white settler in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He was born near Montreal, Quebec, Canada and died in Howard, Wisconsin.

B ...

in 1795. Vieau's post at the mouth of the Milwaukee River

The Milwaukee River is a river in the state of Wisconsin. It is about long.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed May 19, 2011 Once a locus of industry, the river is now the c ...

was purchased in 1820 by Solomon Juneau

Solomon Laurent Juneau, or Laurent-Salomon Juneau (August 9, 1793 – November 14, 1856) was a French Canadian fur trader, land speculator, and politician who helped found the city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He was born in Repentigny, Quebec, Canad ...

, who had visited the area as early as 1818. Juneau moved to what is now Milwaukee and took over the trading post's operation in 1825.

When the fur trade began to decline, Juneau focused on developing the land around his trading post. In the 1830s, he formed a partnership with Green Bay lawyer Morgan Martin, and the two men bought 160 acres (0.6 km2) of land between Lake Michigan and the Milwaukee River. There they founded the settlement of Juneautown. Meanwhile, an Ohio businessman named Byron Kilbourn

Byron Kilbourn (September 8, 1801December 16, 1870) was an American surveyor, railroad executive, and politician who was an important figure in the founding of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He was the 3rd and 8th mayor of Milwaukee.

Biography

Kilbour ...

began to invest in the land west of the Milwaukee River, forming the settlement of Kilbourntown. South of these two settlements, George H. Walker

George H. Walker (October 22, 1811September 20, 1866) was an American trader and politician, and was one of three key founders of the city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He served as the 5th and 7th Mayor of Milwaukee, and represented Milwaukee in the ...

founded the town of Walker's Point Walker's Point or Walkers Point may refer to:

Australia

* Walkers Point, Queensland, a locality in the Fraser Coast Region

* Walkers Point, Queensland (Bundaberg Region), a town in Woodgate in the Bundaberg Region

United States

*Walker's Point, ...

in 1835. Each of these three settlements engaged in a fierce competition to attract the most residents and become the largest of the three towns. In 1840, the Wisconsin State Legislature

The Wisconsin Legislature is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Wisconsin. The Legislature is a bicameral body composed of the upper house, Wisconsin State Senate, and the lower Wisconsin State Assembly, both of which have had Republican ...

ordered the construction of a bridge over the Milwaukee River to replace the inadequate ferry system. In 1845, Byron Kilbourn, who had been trying to isolate Juneautown to make it more dependent on Kilbourntown, destroyed a portion of the bridge, which started the Milwaukee Bridge War

The Milwaukee Bridge War, sometimes simply the Bridge War, was an 1845 conflict between people from different regions of what is now the city of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, over the construction of a bridge crossing the Milwaukee River.

Background

The ...

. For several weeks, skirmishes broke out between the residents of both towns. No one was killed but several people were injured, some seriously. On January 31, 1846 the settlements of Juneautown, Kilbourntown, and Walker's Point merged into the incorporated city of Milwaukee. Solomon Juneau was elected mayor. The new city had a population of about 10,000 people, making it the largest city in the territory. Milwaukee remains the largest city in Wisconsin to this day.

Wisconsin Territory

Wisconsin Territory

The Territory of Wisconsin was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 3, 1836, until May 29, 1848, when an eastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Wisconsin. Belmont was ...

was created by an act of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

on April 20, 1836. By fall of that year, the best prairie groves of the counties surrounding Milwaukee were occupied by New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

farmers. The new territory initially included all of the present day states of Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

, and Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

, as well as parts of North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

. At the time the Congress called it the "Wiskonsin Territory".

The first territorial governor of Wisconsin was Henry Dodge

Moses Henry Dodge (October 12, 1782 – June 19, 1867) was a Democratic member to the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate, Territorial Governor of Wisconsin and a veteran of the Black Hawk War. His son, Augustus C. Dodge, served as a ...

. He and other territorial lawmakers were initially busied by organizing the territory's government and selecting a capital city. The selection of a location to build a capitol caused a heated debate among the territorial politicians. At first, Governor Dodge selected Belmont, located in the heavily populated lead mining district, to be capital. Shortly after the new legislature convened there, however, it became obvious that Wisconsin's first capitol was inadequate. Numerous other suggestions for the location of the capital were given representing nearly every city that existed in the territory at the time, and Governor Dodge left the decision up to the other lawmakers. The legislature accepted a proposal by James Duane Doty

James Duane Doty (November 5, 1799 – June 13, 1865) was a land speculator and politician in the United States who played an important role in the development of Wisconsin and Utah Territory.

Early life and legal career

A descendant of ''Mayflo ...

to build a new city named Madison Madison may refer to:

People

* Madison (name), a given name and a surname

* James Madison (1751–1836), fourth president of the United States

Place names

* Madison, Wisconsin, the state capital of Wisconsin and the largest city known by this ...

on an isthmus between lakes Mendota and Monona and put the territory's permanent capital there. In 1837, while Madison was being built, the capitol was temporarily moved to Burlington

Burlington may refer to:

Places Canada Geography

* Burlington, Newfoundland and Labrador

* Burlington, Nova Scotia

* Burlington, Ontario, the most populous city with the name "Burlington"

* Burlington, Prince Edward Island

* Burlington Bay, no ...

. This city was transferred to Iowa Territory

The Territory of Iowa was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1838, until December 28, 1846, when the southeastern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Iowa. The remaind ...

in 1838, along with all the lands of Wisconsin Territory west of the Mississippi River.

Democracy on the Wisconsin frontier

Wyman calls Wisconsin a "palimpsest" of layer upon layer of peoples and forces, each imprinting permanent influences. He identified these layers as multiple "frontiers" over three centuries: Native American frontier, French frontier, English frontier, fur-trade frontier, mining frontier, and the logging frontier. Finally the coming of the railroad brought the end of the frontier. The historian of the frontier,Frederick Jackson Turner

Frederick Jackson Turner (November 14, 1861 – March 14, 1932) was an American historian during the early 20th century, based at the University of Wisconsin until 1910, and then Harvard University. He was known primarily for his frontier thes ...

, grew up in Wisconsin during its last frontier stage, and in his travels around the state he could see the layers of social and political development. One of Turner's last students, Merle Curti

Merle Eugene Curti (September 15, 1897 – March 9, 1996) was a leading American historian, who taught many graduate students at Columbia University and the University of Wisconsin, and was a leader in developing the fields of social history and ...

used in-depth analysis of local history in Trempeleau County to test Turner's thesis about democracy. Turner's view was that American democracy, "involved widespread participation in the making of decisions affecting the common life, the development of initiative and self-reliance, and equality of economic and cultural opportunity. It thus also involved Americanization of immigrant." Curti found that from 1840 to 1860 in Wisconsin the poorest groups gained rapidly in land ownership, and often rose to political leadership at the local level. He found that even landless young farm workers were soon able to obtain their own farms. Free land on the frontier therefore created opportunity and democracy, for both European immigrants as well as old stock Yankees.

Statehood

By the mid-1840s, the population of Wisconsin Territory had exceeded 150,000, more than twice the number of people required for Wisconsin to become a state. In 1846, the territorial legislature voted to apply for statehood. That fall, 124 delegates debated the state constitution. The document produced by this convention was considered extremely progressive for its time. It banned commercial banking, granted married women the right to own property, and left the question of African-Americansuffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

to a popular vote. Most Wisconsinites considered the first constitution to be too radical, however, and voted it down in an April 1847 referendum.

In December 1847, a second constitutional convention was called. This convention resulted in a new, more moderate state constitution that Wisconsinites approved in a March 1848 referendum, enabling Wisconsin to become the 30th state on May 29, 1848. Wisconsin was the last state entirely east of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

(and by extension the last state formed entirely from territory assigned to the U.S. in the 1783 Treaty of Paris) to be admitted to the Union.

With statehood, came the creation of the University of Wisconsin–Madison

A university () is an educational institution, institution of higher education, higher (or Tertiary education, tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several Discipline (academia), academic disciplines. Universities ty ...

, which is the state's oldest public university. The creation of this university was set aside in the state charter.

Early state economy

In 1847, the ''Mineral Point Tribune'' reported that the town's furnaces were producing 43,800 pounds (19,900 kg) of lead each day. Lead mining in southwest Wisconsin began to decline after 1848 and 1849 when the combination of less easily accessible lead ore and theCalifornia Gold Rush

The California Gold Rush (1848–1855) was a gold rush that began on January 24, 1848, when gold was found by James W. Marshall at Sutter's Mill in Coloma, California. The news of gold brought approximately 300,000 people to California fro ...

made miners leave the area. The lead mining industry in mining communities such as Mineral Point managed to survive into the 1860s, but the industry was never as prosperous as it was before the decline.

By 1850 Wisconsin's population was 305,000. Roughly a third (103,000) were Yankee

The term ''Yankee'' and its contracted form ''Yank'' have several interrelated meanings, all referring to people from the United States. Its various senses depend on the context, and may refer to New Englanders, residents of the Northern United St ...

s from New England and western New York state. The second largest group were the Germans, numbering roughly 38,000, followed by 28,000 British immigrants from England, Scotland and Wales. There were roughly 63,000 Wisconsin-born residents of the state. The Yankee migrants would be the dominant political class in Wisconsin for many years.

A railroad frenzy swept Wisconsin shortly after it achieved statehood. The first railroad line in the state was opened between Milwaukee and Waukesha in 1851 by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad

The Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad (CMStP&P), often referred to as the "Milwaukee Road" , was a Class I railroad that operated in the Midwest and Northwest of the United States from 1847 until 1986.

The company experience ...

. The railroad pushed on, reaching Milton, Wisconsin

Milton is a city in Rock County, Wisconsin, United States. The population was 5,716 at the 2020 census.

History

The city was formed as a result of the 1967 merger of the villages of Milton and Milton Junction. In November of that year, ballot ...

in 1852, Stoughton, Wisconsin

Stoughton is a city in Dane County, Wisconsin, United States. It straddles the Yahara River about 20 miles southeast of the state capital, Madison. Stoughton is part of the Madison Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2020 census, the populati ...

in 1853, and the capital city of Madison in 1854. The company reached its goal of completing a rail line across the state from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River when the line to Prairie du Chien was completed in 1857. Shortly after this, other railroad companies completed their own tracks, reaching La Crosse

La Crosse is a city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of La Crosse County, Wisconsin, La Crosse County. Positioned alongside the Mississippi River, La Crosse is the largest city on Wisconsin's western border. La Crosse's populat ...

in the west and Superior

Superior may refer to:

*Superior (hierarchy), something which is higher in a hierarchical structure of any kind

Places

*Superior (proposed U.S. state), an unsuccessful proposal for the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to form a separate state

*Lake ...

in the north, spurring development in those cities. By the end of the 1850s, railroads crisscrossed the state, enabling the growth of other industries that could now easily ship products to markets across the country.

Early state politics

Nelson Dewey

Nelson Webster Dewey (December 19, 1813July 21, 1889) was an American pioneer, lawyer, and politician. He was the first Governor of Wisconsin.

Early life

Dewey was born in Lebanon, Connecticut, on December 19, 1813, to Ebenezer and Lucy (né ...

, the first governor of Wisconsin

The governor of Wisconsin is the head of government of Wisconsin and the commander-in-chief of the state's army and air forces. The governor has a duty to enforce state laws, and the power to either approve or veto bills passed by the Wiscons ...

, was a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

. Born in Lebanon, Connecticut

Lebanon is a town in New London County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 7,142 at the 2020 census. The town lies just to the northwest of Norwich, directly south of Willimantic, north of New London, and east of Hartford. The farm ...