History Of The United States (1849–1865) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the United States from 1849 to 1865 was dominated by the tensions that led to the American Civil War between North and South, and the bloody fighting in 1861–1865 that produced Northern victory in the war and ended slavery. At the same time

President Pierce was too closely associated with the horrors of "Bleeding Kansas" and was not renominated. Instead, the Democrats nominated former Secretary of State and current ambassador to Great Britain

President Pierce was too closely associated with the horrors of "Bleeding Kansas" and was not renominated. Instead, the Democrats nominated former Secretary of State and current ambassador to Great Britain

The

The

On April 12, 1861, after President Lincoln refused to give up

On April 12, 1861, after President Lincoln refused to give up

The Union assembled an army of 35,000 men (the largest ever seen in North America up to that point) under the command of General

The Union assembled an army of 35,000 men (the largest ever seen in North America up to that point) under the command of General

"On the Eve of War: North vs. South"

lesson plan for grades 9–12 from National Endowment for the Humanities "EDSITEMENT" series {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The United States (1849-1865) 1860s in the United States 1840s in the United States 1850s in the United States History of the United States by period

industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

and the transportation revolution changed the economics of the Northern United States

The Northern United States, commonly referred to as the American North, the Northern States, or simply the North, is a geographical and historical region of the United States.

History Early history

Before the 19th century westward expansion, the ...

and the Western United States

The Western United States (also called the American West, the Western States, the Far West, the Western territories, and the West) is List of regions of the United States, census regions United States Census Bureau.

As American settlement i ...

. Heavy immigration from Western Europe shifted the center of population further to the North.

Industrialization went forward in the Northeast

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west—eac ...

, from Pennsylvania to New England. A rail network and a telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas ...

network linked the nation economically, opening up new markets. Immigration brought millions of European workers and farmers to the Northern United States. In the Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, Dixieland, or simply the South) is List of regions of the United States, census regions defined by the United States Cens ...

, planters shifted operations (and slaves) from the poor soils of the Southeastern United States

The Southeastern United States, also known as the American Southeast or simply the Southeast, is a geographical List of regions in the United States, region of the United States located in the eastern portion of the Southern United States and t ...

to the rich cotton lands of the Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural list of regions of the United States, region of the United States that includes Arizona and New Mexico, along with adjacen ...

.

Issues of slavery in the new territories acquired in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

(1846–1848) were temporarily resolved by the Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

. One provision, the Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of slaves who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from the Fugi ...

, sparked intense controversy, as revealed in the enormous interest in the plight of the escaped slave in ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two Volume (bibliography), volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans ...

'', an 1852 anti-slavery novel and play.

In 1854, the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

reversed long-standing compromises by providing that each new state of the Union would decide its posture on slavery (popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

). The newly formed Republican Party stood against the expansion of slavery and won control of most Northern states (with enough electoral votes to win the presidency in 1860). The invasion of Kansas by sponsored pro- and anti-slavery factions intent on voting slavery up or down, with resulting bloodshed (Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

), angered both North and South. The Supreme Court tried unsuccessfully to resolve the issue of slavery in the territories with a pro-slavery ruling, in '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'', that angered the North.

After the 1860 election of Republican Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

, seven Southern states declared their secession from the United States between late 1860 and 1861, establishing a rebel government, the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

on February 9, 1861. The Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

began when Confederate General Pierre Beauregard opened fire upon Union troops at Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

in South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

. Four more states seceded as Lincoln called for troops to fight an insurrection.

The next four years were the darkest in American history as the nation tore at itself using the latest military technology and highly motivated soldiers. The urban, industrialized Northern states (the Union) eventually defeated the mainly rural, agricultural Southern states (the Confederacy), but between 600,000 and 700,000 American soldiers (on both sides combined) were killed, and much of the infrastructure of the South was devastated. About 8% of all white males aged 13 to 43 died in the war, including 6% in the North and an extraordinary 18% in the South. In the end, slavery was abolished, and the Union was restored, richer and more powerful than ever, while the South was embittered and impoverished.

Economic and cultural changes

Developing a market economy

By the 1840s, theIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

was transforming the Northeast, with a dense network of railroads, canals, textile mills, small industrial cities, and growing commercial centers, with hubs in Boston, New York City, and Philadelphia. Although manufacturing interests, especially in Pennsylvania, sought a high tariff, the actual tariff in effect was low, and was reduced several times, with the 1857 tariff the lowest in decades. The Midwest region, based on farming and increasingly on animal production, was growing rapidly, using the railroads and river systems to ship food to slave plantations in the south, industrial cities in the East, and industrial cities in Britain and Europe.

In the south, the cotton plantations were flourishing, thanks to the very high price of cotton on the world market. Cotton production wears out the land, and so the center of gravity was continually moving west. The annexation of Texas in 1845 opened up the last great cotton lands. Meanwhile, other commodities, such as tobacco in Virginia and North Carolina, were in the doldrums. Slavery was dying out in the upper South, and survived because of sales of slaves to the growing cotton plantations in the Southwest. While the Northeast was rapidly urbanizing, and urban centers such as Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Chicago were rapidly growing in the Midwest, the South remained overwhelmingly rural. The great wealth generated by slavery was used to buy new lands, and more slaves. At all times the great majority of Southern whites owned no slaves, and operated farms on a subsistence basis, serving small local markets.

A transportation revolution was underway thanks to heavy infusions of capital from London, Paris, Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. Hundreds of local short haul lines were being consolidated to form a railroad system, that could handle long-distance shipment of farm and industrial products, as well as passengers. In the South, there were few systems, and most railroad lines were short haul project designed to move cotton to the nearest river or ocean port. Meanwhile, steamboats provided a good transportation system on the inland rivers.

With the use of interchangeable parts

Interchangeable parts are parts (wikt:component#Noun, components) that are identical for practical purposes. They are made to specifications that ensure that they are so nearly identical that they will fit into any assembly of the same type. One ...

popularized by Eli Whitney

Eli Whitney Jr. (December 8, 1765January 8, 1825) was an American inventor, widely known for inventing the cotton gin in 1793, one of the key inventions of the Industrial Revolution that shaped the economy of the Antebellum South.

Whitney's ...

, the factory system

The factory system is a method of manufacturing whereby workers and manufacturing equipment are centralized in a factory, the work is supervised and structured through a division of labor, and the manufacturing process is mechanized.

Because ...

began in which workers assembled at one location to produce goods. The early textile factories such as the Lowell mills employed mainly women, but generally factories were a male domain.

By 1860, 16% of Americans lived in cities with 2500 or more people; a third of the nation's income came from manufacturing. Urbanized industry was limited primarily to the Northeast; cotton cloth production was the leading industry, with the manufacture of shoes, woolen clothing, and machinery also expanding. Energy was provided in most cases by water power from the rivers, but steam engines were being introduced to factories as well. By 1860, the railroads had made a transition from use of local wood supplies to coal for their locomotives. Pennsylvania became the center of the coal industry. Many, if not most, of the factory workers and miners were recent immigrants from Europe, or their children. Throughout the North, and in southern cities, entrepreneurs were setting up factories, mines, mills, banks, stores, and other business operations. In the great majority of cases, these were relatively small, locally owned, and locally operated enterprises.

Immigration and labor

To fill the new factory jobs, immigrants poured into the United States in the first mass wave of immigration in the 1840s and 1850s. Known as the period of old immigration, this time saw 4.2 million immigrants come into the United States raising the overall population to over 20 million people. Historians often describe this as a time of "push-pull" immigration. People who were "pushed" to the United States immigrated because of poor conditions back home that made survival dubious while immigrants who were "pulled" came from stable environments to find greater economic success. One group who was "pushed" to the United States was the Irish, who were attempting to escape the Great Famine in their nation. Settling around the coastal cities ofBoston, Massachusetts

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

and New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, the Irish were not initially welcomed because of their poverty and Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

beliefs. They lived in crowded, filthy neighborhoods and performed low-paying and physically demanding jobs. The Catholic Church was widely distrusted by many Americans as a symbol of European autocracy. German immigration, on the other hand, was "pulled" to America to avoid a looming financial disaster in their nation. Unlike the Irish, the German immigrants often sold their possessions and arrived in America with money in hand. German immigrants were both Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

and Catholic, although the latter did not face the discrimination that the Irish did. Many Germans settled in communities in the Midwest rather than on the coast. Major cities such as Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati ( ; colloquially nicknamed Cincy) is a city in Hamilton County, Ohio, United States, and its county seat. Settled in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking River (Kentucky), Licking and Ohio Ri ...

and St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an Independent city (United States), independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Miss ...

developed large German populations. Unlike the Irish, most German immigrants were educated, middle-class people who mainly came to America for political rather than economic reasons. In the big cities such as New York, immigrants often lived in ethnic enclaves

In sociology, an ethnic enclave is a geographic area with high ethnic concentration, characteristic cultural identity, and economic activity. The term is usually used to refer to either a residential area or a workspace with a high concentration ...

called "ghettos" that were often impoverished and crime-ridden. The most infamous of these immigrant neighborhoods was the Five Points in New York City. With increasing labor agitation for higher wages and better working conditions, such as by the Lowell mill girls in Massachusetts, many factory owners began to replace female workers with immigrants who would work cheaper and were less demanding about factory conditions.

Political upheaval

Wilmot Proviso

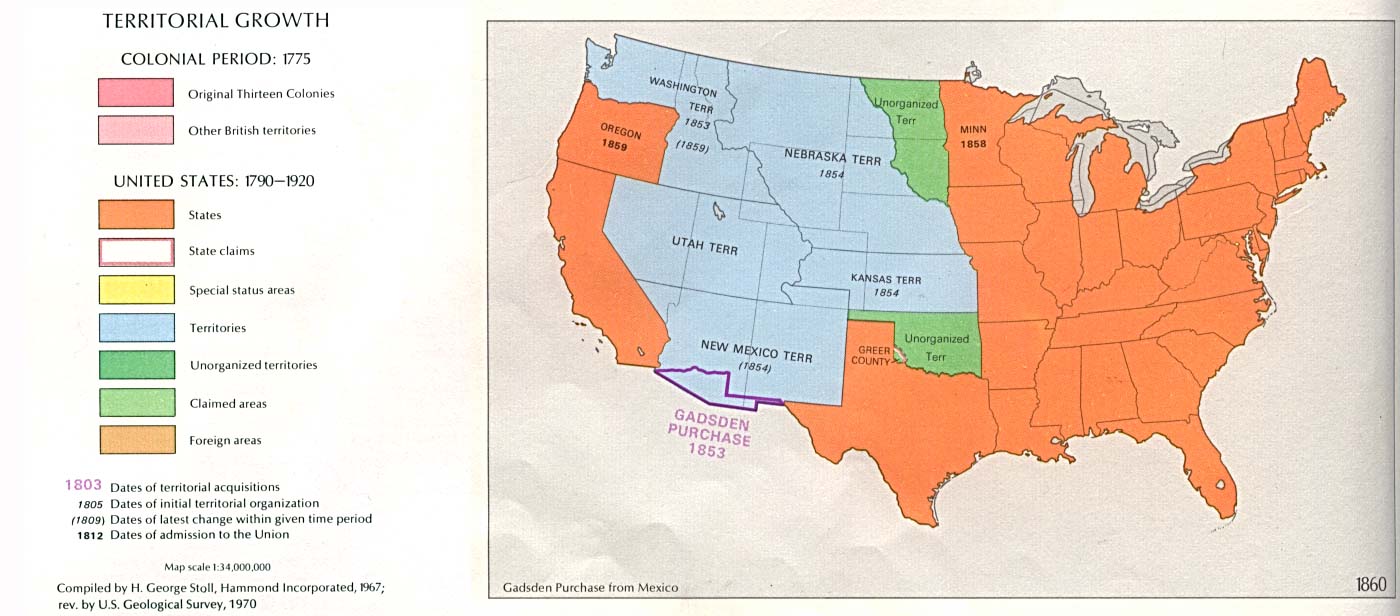

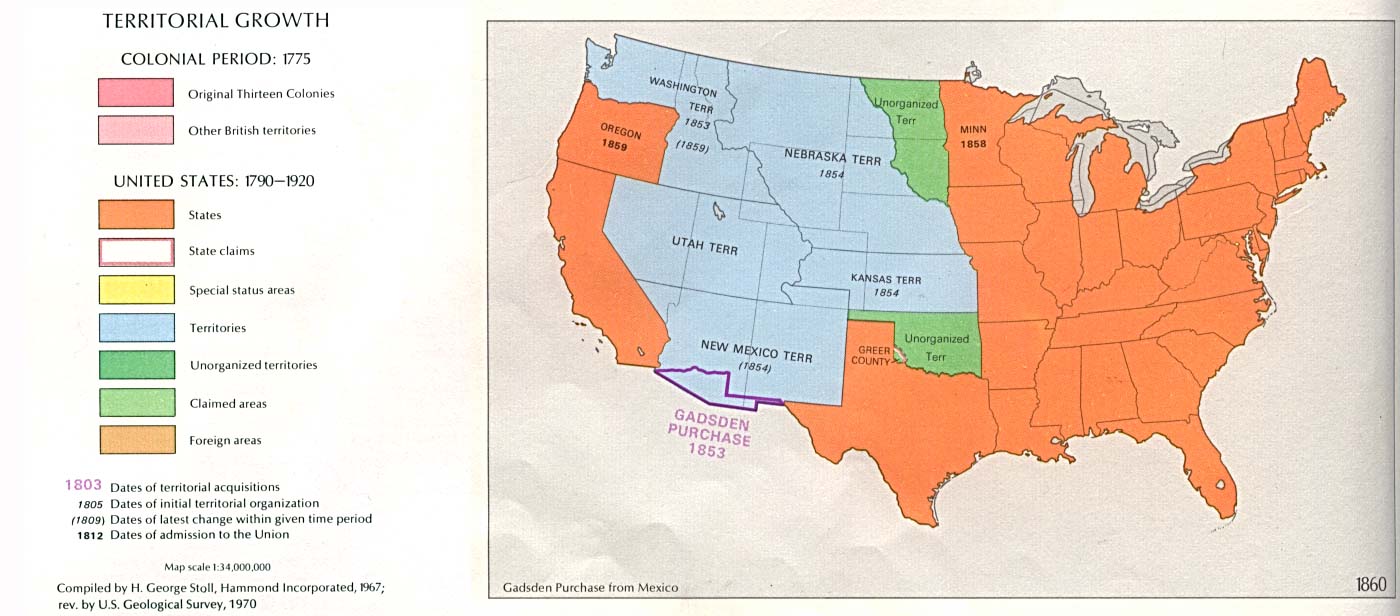

In 1848 the acquisition of new territory fromMexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ended the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). It was signed on 2 February 1848 in the town of Villa de Guadalupe, Mexico City, Guadalupe Hidalgo.

After the defeat of its army and the fall of the cap ...

renewed the sectional debate over slavery. The question of whether the new territory would allow slavery was the main question, with Northern Congressmen hoping to limit slavery and Southern Congressmen hoping to expand the territory in which it was legal. Soon after the Mexican–American War began, Democratic Congressman David Wilmot proposed that territory won from Mexico should be free from the institution of slavery. Called the Wilmot Proviso

The Wilmot Proviso was an unsuccessful 1846 proposal in the United States Congress to ban slavery in territory acquired from Mexico in the Mexican–American War. The conflict over the Wilmot Proviso was one of the major events leading to the ...

, the measure failed to pass Congress and thus never became law. This served to unify the majority of Southerners, who saw the Proviso as an attack on their society and their constitutional rights.

Popular sovereignty debate

With the failure of the Wilmot Proviso, SenatorLewis Cass

Lewis Cass (October 9, 1782June 17, 1866) was a United States Army officer and politician. He represented Michigan in the United States Senate and served in the Cabinets of two U.S. Presidents, Andrew Jackson and James Buchanan. He was also the 1 ...

introduced the idea of popular sovereignty

Popular sovereignty is the principle that the leaders of a state and its government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associativ ...

in Congress. In an attempt to hold the Congress together as it continued to divide along sectional rather than party lines, Cass proposed that Congress did not have the power to determine whether territories could allow slavery, since this was not an enumerated power

The enumerated powers (also called expressed powers, explicit powers or delegated powers) of the United States Congress are the powers granted to the federal government of the United States by the United States Constitution. Most of these powers ar ...

listed in the Constitution. Instead, Cass proposed that the people living in the territories themselves should decide the slavery issue. For the Democrats, the solution was not as clear as it appeared. Northern Democrats called for "squatter sovereignty", in which the people living in the territory could decide the issue when a territorial legislature was convened. Southern Democrats disputed this idea, arguing that the issue of slavery must be decided at the time of adoption of a state constitution, when the request was made to Congress for admission as a state. Cass and other Democratic leaders failed to clarify the issue so that neither section of the country felt slighted as the election approached. After Cass' defeat in 1848, Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas ( né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party to run for president in the 1860 ...

assumed a leading role in the party and became closely associated with popular sovereignty with his proposal of the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

California gold rush

The election of 1848 produced a new president from the Whig Party,Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military officer and politician who was the 12th president of the United States, serving from 1849 until his death in 1850. Taylor was a career officer in the United States ...

. James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (; November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. A protégé of Andrew Jackson and a member of the Democratic Party, he was an advocate of Jacksonian democracy and ...

did not seek reelection because he achieved all his objectives in his first term and because his health was declining. From the election emerged the Free Soil Party

The Free Soil Party, also called the Free Democratic Party or the Free Democracy, was a political party in the United States from 1848 to 1854, when it merged into the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party. The party was focused o ...

, a group of anti-slavery Democrats who supported Wilmot's Proviso. The creation of the Free Soil Party foreshadowed the collapse of the Second Party System

The Second Party System was the Political parties in the United States, political party system operating in the United States from about 1828 to early 1854, after the First Party System ended. The system was characterized by rapidly rising leve ...

; the existing parties could not contain the debate over slavery for much longer.

The question of slavery became all the more urgent with the discovery of gold in California in 1848. The next year, there was a massive influx of prospectors

Prospecting is the first stage of the geological analysis (followed by exploration) of a territory. It is the search for minerals, fossils, precious metals, or mineral specimens. It is also known as fossicking.

Traditionally prospecting rel ...

and miners

A miner is a person who extracts ore, coal, chalk, clay, or other minerals from the earth through mining. There are two senses in which the term is used. In its narrowest sense, a miner is someone who works at the rock face (mining), face; cutt ...

looking to strike it rich. Most migrants to California (so-called 'Forty-Niners') abandoned their jobs, homes, and families looking for gold. This huge migration of white settlers to the Pacific coast led to confrontations with Native populations, including the ethnic cleansing

Ethnic cleansing is the systematic forced removal of ethnic, racial, or religious groups from a given area, with the intent of making the society ethnically homogeneous. Along with direct removal such as deportation or population transfer, it ...

of thousands of Native inhabitants. Some historians (and a state governor) have referred to this period lasting into the early 1870s as the California genocide

The California genocide was a series of genocidal massacres of the indigenous peoples of California by United States soldiers and settlers during the 19th century. It began following the American conquest of California in the Mexican–Americ ...

.

It also attracted some of the first Chinese Americans

Chinese Americans are Americans of Chinese ancestry. Chinese Americans constitute a subgroup of East Asian Americans which also constitute a subgroup of Asian Americans. Many Chinese Americans have ancestors from mainland China, Hong Kong ...

to the West Coast of the United States

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast and the Western Seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the Contiguous United States, contig ...

. Most Forty-Niners never found gold but instead settled in the urban center of San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

or in the new municipality of Sacramento

Sacramento ( or ; ; ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of California and the seat of Sacramento County. Located at the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers in Northern California's Sacramento Valley, Sacramento's 2020 p ...

.

Compromise of 1850

The influx of population led to California's application for statehood in 1850. This created a renewal of sectional tension because California's admission into the Union threatened to upset the balance of power in Congress. The imminent admission of Oregon,New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

, and Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. It also borders Wyoming to the northea ...

also threatened to upset the balance. Many Southerners also realized that the climate of those territories did not lend themselves to the extension of slavery (it was not yet foreseen that the Central Valley in California would someday become a center of cotton farming). Debate raged in Congress until a resolution was found in 1850.

President Taylor threatened to personally command an army against any Southern state that would secede from the Union, and he also threatened force against Texas, which laid claim to the eastern half of New Mexico. However, Taylor died of an intestinal ailment in July 1850, and his successor, Vice President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853. He was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House, and the last to be neither a De ...

, was a lawyer by training and far less war-like.

The Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states during the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designe ...

was proposed by "The Great Compromiser", Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

and was passed by Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

. Through the compromise, California was admitted as a free state, Texas was financially compensated for the loss of its Western territories, the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

(not slavery) was abolished in the District of Columbia

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, the Fugitive Slave Law

The fugitive slave laws were laws passed by the United States Congress in 1793 and 1850 to provide for the return of slaves who escaped from one state into another state or territory. The idea of the fugitive slave law was derived from the Fugi ...

was passed as a concession to the South, and, most importantly, the New Mexico Territory

The Territory of New Mexico was an organized incorporated territory of the United States from September 9, 1850, until January 6, 1912. It was created from the U.S. provisional government of New Mexico, as a result of '' Nuevo México'' becomi ...

(including modern day Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

and the Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th st ...

) would determine its status (either free or slave) by popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the tota ...

. A group of Southern extremists, still not satisfied with the compromise, held two conventions in Nashville, Tennessee calling for secession, one during the summer of 1850 and the other late in the year, but by that point the Compromise had already passed through Congress and been accepted by the Southern states.

The Compromise of 1850 temporarily defused the divisive issue, but the peace was not to last long.

Presidential election of 1852

Having lost two presidential elections to Whig war heroes, the Democratic Party tried their own by nominatingFranklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

of New Hampshire, who had served without great distinction in the Mexican War. Endorsed by Southern Democrats, Pierce openly supported the Compromise and the Fugitive Slave Act. The Whigs rejected the idea of running incumbent President Fillmore, and so instead turned to another war hero in General Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as Commanding General of the United States Army from 1841 to 1861, and was a veteran of the War of 1812, American Indian Wars, Mexica ...

. Although a capable man, Scott's haughty personality alienated many voters and Pierce won an easy victory at the ballot box.

Foreign affairs

The acquisition of the Southwest had made the United States a Pacific power. Diplomatic and commercial ties withChina

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

had been first established in 1844, and American merchants and shippers began urging an opening of ties with Japan, a country that had virtually isolated itself from the outside world for the past 300 years. In 1853, a fleet commanded by Commodore Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a United States Navy officer who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War. He led the Perry Expedition that Bakumatsu, ended Japan' ...

arrived in Japan and forced the shogunate to sign a treaty with US, although Japanese fears of Russian encroachment also moved matters along.

Closer to home, Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

was long coveted by Southerners as the choicest slave territory available. If annexed by the US and split into 3–4 states, it would restore the slave versus free state balance in Congress. President Polk had in 1845 offered the island's owner, Spain, $100 million for the island, but it was refused and Madrid made it clear that they would not part with the island under any circumstance. Southerners were not about to give up their designs on Cuba, and several filibustering expeditions were mounted. They were easily repulsed by the Spanish authorities, and the last attempt ended in fifty Americans being captured and executed for piracy, including many men from the leading families of the South. A group of enraged Southerners responded by ransacking the Spanish consulate in New Orleans.

In 1854, the Spanish authorities captured the steamer ''Black Warrior'' on a technicality. War appeared to threaten, and Southerners in Congress were aggressively pushing President Pierce for it. Since the European powers were distracted with the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

, there was also nobody that could come to Madrid's assistance. Meanwhile, the US ambassadors to Spain, Britain, and France met in secret in Ostend, Belgium where they proposed a "battle plan" that involved offering Spain up to $120 million for Cuba. If Madrid still refused, then US was justified in taking the island by force. However, the Ostend Manifesto soon leaked out, and an outcry from free soil Northerners forced the Pierce Administration to give up its ambitions on Cuba. Coincidentally, just as Southerners had their eye on territories in the Caribbean, Northerners in the 1850s also developed renewed designs on Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

. In the end, both sides stalemated each other and got nothing as a result.

Antislavery and abolitionism

The debate over slavery in the pre-Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

United States has several sides. Abolitionists grew directly out of the Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

and the European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

and saw slavery as an affront to God and/or reason. Abolitionism had roots similar to the temperance movement

The temperance movement is a social movement promoting Temperance (virtue), temperance or total abstinence from consumption of alcoholic beverages. Participants in the movement typically criticize alcohol intoxication or promote teetotalism, and ...

. The publishing of Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and wrote the popular novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (185 ...

's ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two Volume (bibliography), volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans ...

'', in 1852, galvanized the abolitionist movement.

Most debates over slavery, however, had to do with the constitutionality of the extension of slavery rather than its morality. The debates took the form of arguments over the powers of Congress rather than the merits of slavery. The result was the so-called "Free Soil Movement". Free-soilers believed that slavery was dangerous because of what it did to whites. The " peculiar institution" ensured that elites controlled most of the land, property, and capital in the South. The Southern United States was, by this definition, undemocratic. To fight the "slave power conspiracy", the nation's democratic ideals had to be spread to the new territories and the South.

In the South, however, slavery was justified in many ways. The Nat Turner Uprising of 1831 had terrified Southern whites. Moreover, the expansion of "King Cotton

"King Cotton" is a slogan that summarized the strategy used before the American Civil War (of 1861–1865) by secessionists in the southern states (the future Confederate States of America) to claim the feasibility of secession and to prove ther ...

" into the Deep South

The Deep South or the Lower South is a cultural and geographic subregion of the Southern United States. The term is used to describe the states which were most economically dependent on Plantation complexes in the Southern United States, plant ...

further entrenched the institution into Southern society. John Calhoun's treatise, ''The Pro-Slavery Argument'', stated that slavery was not simply a necessary evil but a positive good. Slavery was a blessing to so-called African savages. It civilized them and provided them with the lifelong security that they needed. Under this argument, the pro-slavery proponents believed that the African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

s were unable to take care of themselves because they were biologically inferior. Furthermore, white Southerners looked upon the North and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

as soulless industrial societies with little culture. Whereas the North was dirty, dangerous, industrial, fast-paced, and greedy, pro-slavery proponents believed that the South was civilized, stable, orderly, and moved at a 'human pace.'

According to the 1860 U.S. census, fewer than 385,000 individuals (i.e. 1.4% of whites

White is a racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly European ancestry. It is also a skin color specifier, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, ethnicity and point of view.

De ...

in the country, or 4.8% of southern whites) owned one or more slaves. 95% of blacks lived in the South, comprising one-third of the population there as opposed to 1% of the population of the North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

.

Kansas–Nebraska Act

With the admission of California as a state in 1850, the Pacific Coast had finally been reached.Manifest Destiny

Manifest destiny was the belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American pioneer, American settlers were destined to expand westward across North America, and that this belief was both obvious ("''m ...

had brought Americans to the end of the continent. President Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800 – March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853. He was the last president to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House, and the last to be neither a De ...

hoped to continue Manifest Destiny, and with this aim he sent Commodore Matthew Perry to Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

in the hopes of arranging trade agreements in 1853.

A railroad to the Pacific was planned, and Senator Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

wanted the transcontinental railway to pass through Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

. Southerners protested, insisting that it run through Texas, Southern California and end in New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

. Douglas decided to compromise and introduced the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law b ...

of 1854. In exchange for having the railway run through Chicago, he proposed 'organizing' (open for white settlement) the territories of Kansas and Nebraska

Nebraska ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. It borders South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Ka ...

.

Douglas anticipated Southern opposition to the act and added in a provision that stated that the status of the new territories would be subject to popular sovereignty. In theory, the new states could become slave states under this condition. Under Southern pressure, Douglas added a clause which explicitly repealed the Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise (also known as the Compromise of 1820) was federal legislation of the United States that balanced the desires of northern states to prevent the expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand ...

. President Franklin Pierce

Franklin Pierce (November 23, 1804October 8, 1869) was the 14th president of the United States, serving from 1853 to 1857. A northern Democratic Party (United States), Democrat who believed that the Abolitionism in the United States, abolitio ...

supported the bill as did the South and a fraction of northern Democrats.

The act split the Whigs. Northern Whigs generally opposed the Kansas–Nebraska Act while Southern Whigs supported it. Most Northern Whigs joined the new Republican Party. Some joined the Know-Nothing Party

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock nativist political movement in the United States in the 1850s. Members of the m ...

which refused to take a stance on slavery. The southern Whigs tried different political moves, but could not reverse the regional dominance of the Democratic Party.

Bleeding Kansas

With the opening of Kansas, both pro- and anti-slavery supporters rushed to settle in the new territory. Violent clashes soon erupted between them. Abolitionists fromNew England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

settled in Topeka

Topeka ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Shawnee County, Kansas, Shawnee County. It is along the Kansas River in the central part of Shawnee County, in northeaste ...

, Lawrence, and Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

. Pro-slavery advocates, mainly from Missouri, settled in Leavenworth and Lecompton.

In 1855, elections were held for the territorial legislature. While there were only 1,500 legal voters, migrants from Missouri swelled the population to over 6,000. The result was that a pro-slavery majority was elected to the legislature. Free-soilers were so outraged that they set up their own delegates in Topeka. A group of pro-slavery Missourians sacked Lawrence on May 21, 1856. Violence continued for two more years until the promulgation of the Lecompton Constitution

The Lecompton Constitution (1858) was the second of four proposed state constitutions of Kansas. Named for the city of Lecompton, Kansas where it was drafted, it was strongly pro-slavery. It never went into effect.

History Purpose

The Lecompton ...

.

The violence, known as "Bleeding Kansas

Bleeding Kansas, Bloody Kansas, or the Border War, was a series of violent civil confrontations in Kansas Territory, and to a lesser extent in western Missouri, between 1854 and 1859. It emerged from a political and ideological debate over the ...

", scandalized the Democratic administration and began a more heated sectional conflict. Charles Sumner

Charles Sumner (January 6, 1811March 11, 1874) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Massachusetts in the United States Senate from 1851 until his death in 1874. Before and during the American Civil War, he was a leading American ...

of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

gave a speech in the Senate entitled "The Crime Against Kansas". The speech was a scathing criticism of the South and the " peculiar institution". As an example of rising sectional tensions, days after delivering the speech, South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

Representative Preston Brooks

Preston Smith Brooks (August 5, 1819 – January 27, 1857) was an American slaver, politician, and member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina, serving as a member of the Democratic Party from 1853 until his resignation i ...

approached Sumner during a recess of the Senate and caned him.

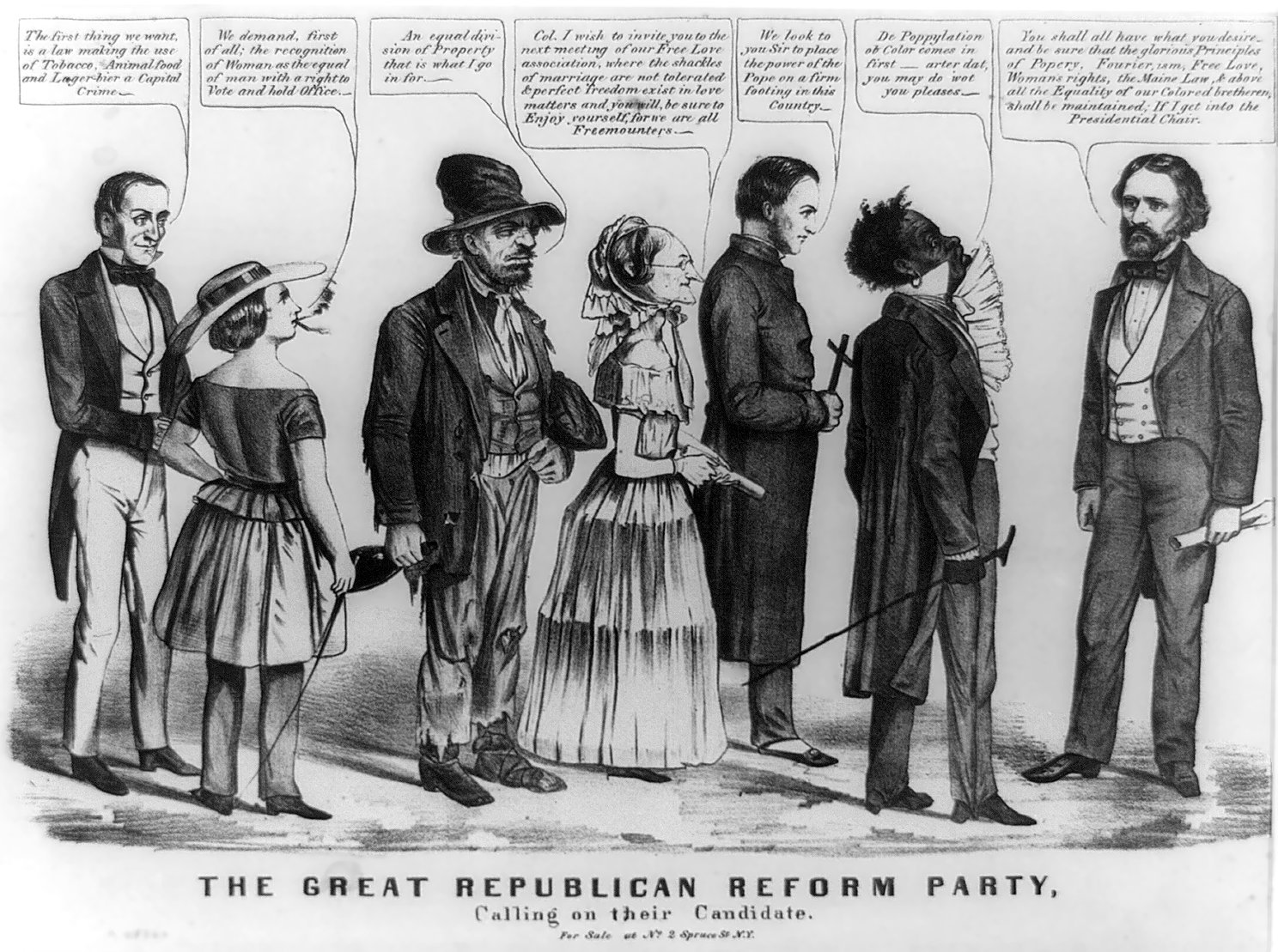

The new Republican Party

The new Republican party emerged in 1854–1856 in the North; it had minimal support in the South. Most members were former Whigs or Free Soil Democrats. The Party was ideological, with a focus on stopping the spread of slavery, and modernizing the economy through tariffs, banks, railroads and free homestead land for farmers. Without using the term "containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

", the new Party in the mid-1850s proposed a system of containing slavery, once it gained control of the national government. Historian James Oakes explains the strategy:

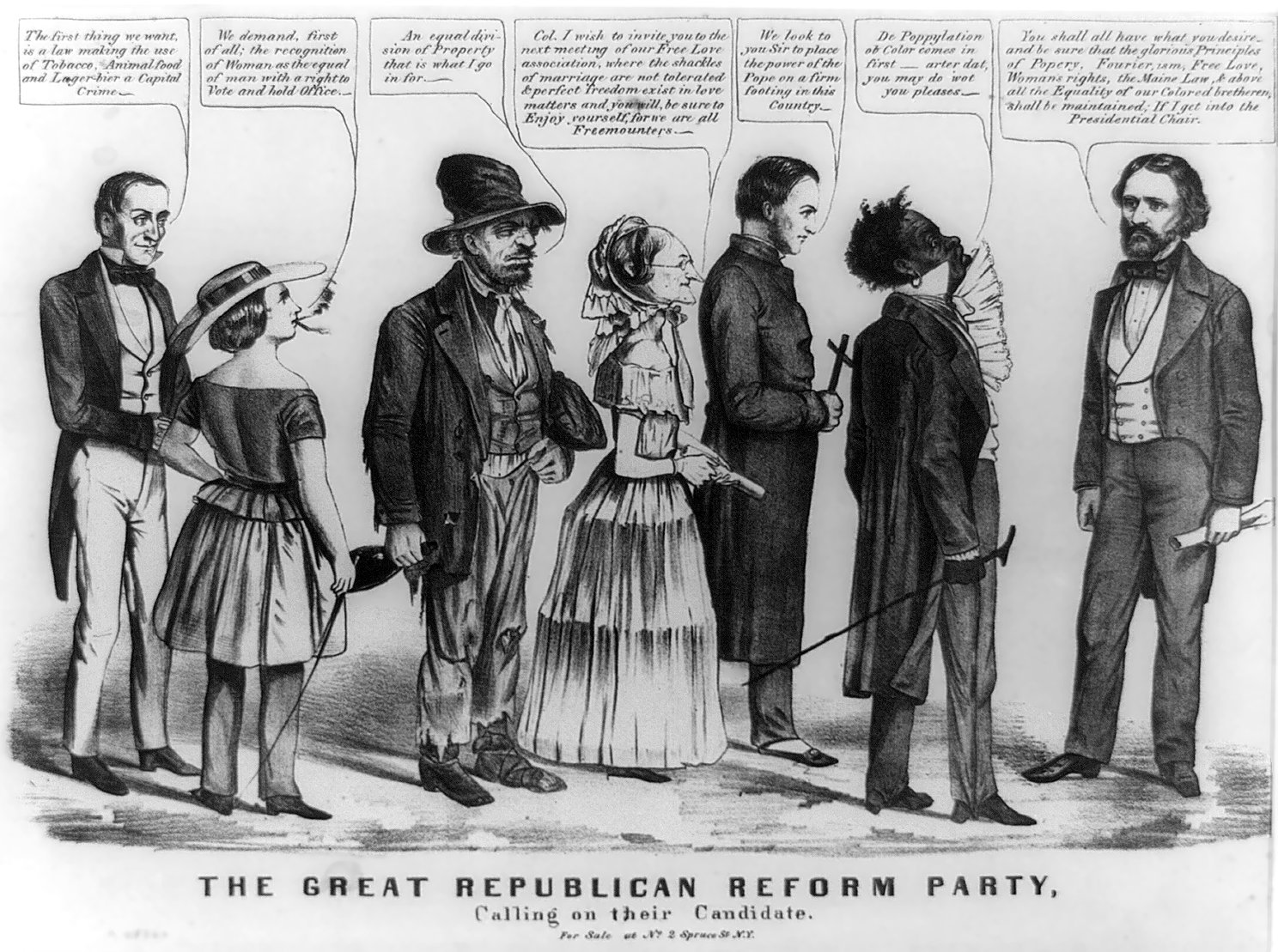

Presidential election of 1856

President Pierce was too closely associated with the horrors of "Bleeding Kansas" and was not renominated. Instead, the Democrats nominated former Secretary of State and current ambassador to Great Britain

President Pierce was too closely associated with the horrors of "Bleeding Kansas" and was not renominated. Instead, the Democrats nominated former Secretary of State and current ambassador to Great Britain James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was the 15th president of the United States, serving from 1857 to 1861. He also served as the United States Secretary of State, secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and represented Pennsylvan ...

, The Know Nothing

The American Party, known as the Native American Party before 1855 and colloquially referred to as the Know Nothings, or the Know Nothing Party, was an Old Stock Americans, Old Stock Nativism in United States politics, nativist political movem ...

Party nominated former President Millard Fillmore, who campaigned on a platform that mainly opposed immigration and urban corruption of the sort associated with Irish Catholics. The Republicans nominated famed soldier-explorer John Frémont under the slogan of "Free soil, free labor, free speech, free men, Frémont and victory!" Frémont won most of the North and nearly won the election. A slight shift of votes in Pennsylvania and Illinois would have resulted in a Republican victory. It had a strong base with majority support in most Northern states. It dominated in New England, New York and the northern Midwest, and had a strong presence in the rest of the North. It had almost no support in the South, where it was roundly denounced in 1856–60 as a divisive force that threatened civil war.

The election campaign was a bitter one with a high degree of personal attacks levied at all three candidates—Buchanan, aged 65, was mocked as being too old to be president and for not being married. Fremont was ridiculed for being born out of wedlock to a teenage mother. More damaging to the latter was the accusation by Know-Nothings that he was a secret Roman Catholic. Some Southern leaders threatened secession if a "free soiler" Northern candidate were elected. The two-year-old Republican Party nonetheless had a strong showing in its first presidential contest, and might have won except for Fillmore.

An uninspiring figure, Buchanan won the election with 174 electoral votes to Fremont's 114. Immediately following Buchanan's inauguration in March 1857, there was a sudden depression, known as the Panic of 1857

The Panic of 1857 was a financial crisis in the United States caused by the declining international economy and over-expansion of the domestic economy. Because of the invention of the telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission ...

, which weakened the credibility of the Democratic Party further. He feuded incessantly with Stephen Douglas for control of the Democratic Party, while the Republicans remained united and the Fillmore's third party collapsed.

Dred Scott decision

On March 6, 1857, a mere two days after Buchanan's inauguration, the Supreme Court handed down the infamous '' Dred Scott v. Sandford'' decision. Dred Scott, a slave, had lived with his master for a few years in Illinois and Wisconsin, and with the support of abolitionist groups, was now suing for his freedom on the grounds that he resided in a free state. The Supreme Court quickly ruled on the very obvious—that slaves were not US citizens and thus had no right to sue in a Federal court. It also ruled that since slaves were private property, their master was fully within his rights to reclaim runaways, even if they were in a state where slavery did not exist, on the grounds that the Fifth Amendment forbade Congress to deprive a citizen of his property without due process of law. Furthermore, the Supreme Court decided that the Missouri Compromise, which had been replaced a few years earlier by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, had always been unconstitutional and Congress had no authority to restrict slavery within a territory, regardless of its citizens' wishes. The decision outraged Northern opponents of slavery such as Abraham Lincoln and lent substance to the Republican charge that aSlave Power

The Slave Power, or Slavocracy, referred to the perceived political power held by American slaveholders in the federal government of the United States during the Antebellum period. Antislavery campaigners charged that this small group of wealth ...

controlled the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court had sanctioned the hardline Southern view. This emboldened Southerners to demand even more rights for slavery, just as Northern opposition hardened. Anti-slavery speakers protested that the Supreme Court could merely interpret law, not make it, and thus the Dred Scott Decision could not legally open a territory to slavery.

Lincoln-Douglas debates

The seven famous Lincoln-Douglas debates were held for the Senatorial election in Illinois between incumbentStephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (né Douglass; April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. As a United States Senate, U.S. senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party (United States) ...

and Abraham Lincoln, whose political experience was limited to a single term in Congress that had been mainly notable for his opposition to the Mexican War. The debates are remembered for their relevance and eloquence.

Lincoln was opposed to the extension of slavery into any new territories. Douglas, however, believed that the people should decide the future of slavery in their own territories. This was known as popular sovereignty. Lincoln, however, argued that popular sovereignty was pro-slavery since it was inconsistent with the Dred Scott Decision. Lincoln said that Chief Justice Roger Taney was the first person who said that the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

did not apply to blacks and that Douglas was the second. In response, Douglas came up with what is known as the Freeport Doctrine. Douglas stated that while slavery may have been legally possible, the people of the state could refuse to pass laws favourable to slavery.

In his famous " House Divided Speech" in Springfield, Illinois

Springfield is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Illinois. Its population was 114,394 at the 2020 United States census, which makes it the state's List of cities in Illinois, seventh-most populous cit ...

, Lincoln stated:

:"A house divided against itself cannot stand." I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved. I do not expect the house to fall, but I do expect that it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery will arrest further the spread of it and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward until it shall become alike lawful in all the states, old as well as new, North as well as South.

During the debates, Lincoln argued that his speech was not abolitionist, writing at the Charleston debate that:

:I am not in favor of making voters or jurors of Negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office.

The debates attracted thousands of spectators and featured parades and demonstrations. Lincoln ultimately lost the election but vowed:

:The fight must go on. The cause of civil liberty must not be surrendered at the end of one or even 100 defeats.

John Brown's raid

The debate took a new, violent turn with the actions of an abolitionist fromConnecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

. John Brown was a militant abolitionist who advocated guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

to combat pro-slavery advocates. Receiving arms and financial aid from a group of prominent Massachusetts business and social leaders known collectively as the Secret Six, Brown participated in the violence of Bleeding Kansas and directed the Pottawatomie massacre on May 24, 1856, in response to the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas. In 1859, Brown went to Virginia to liberate slaves. On October 17, Brown seized the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. His plan was to arm slaves in the surrounding area, creating a slave army to sweep through the South, attacking slaveowners and liberating slaves. Local slaves did not rise up to support Brown. He killed five civilians and took hostages. He also stole a sword that Frederick the Great

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself ''King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prussia ...

had given George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

. He was captured by an armed military force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

. He was tried for treason to the Commonwealth of Virginia and hanged on December 2, 1859. On his way to the gallows, Brown handed a jailkeeper a note, chilling in its prophecy, predicting that the "sin" of slavery would never be cleansed from the United States without bloodshed.

The raid on Harper's Ferry horrified Southerners who saw Brown as a criminal, and they became increasingly distrustful of Northern abolitionists who celebrated Brown as a hero and a martyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

.

Presidential election of 1860

The

The Democratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 18 ...

for the Election of 1860 was held in Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the List of municipalities in South Carolina, most populous city in the U.S. state of South Carolina. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint of South Carolina's coastline on Charleston Harbor, an inlet of the Atla ...

, despite it usually being held in the North. When the convention endorsed the doctrine of popular sovereignty, 50 Southern delegates walked out. The inability to come to a decision on who should be nominated led to a second meeting in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the List of United States ...

. At Baltimore, 110 Southern delegates, led by the so-called " fire eaters", walked out of the convention when it would not adopt a platform that endorsed the extension of slavery into the new territories. The remaining Democrats nominated Stephen A. Douglas for the presidency. The Southern Democrats

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States.

Before the American Civil War, Southern Democrats mostly believed in Jacksonian democracy. In the 19th century, they defended slavery in the ...

held a convention in Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, and nominated John Breckinridge. Both claimed to be the true voice of the Democratic Party.

Former Know Nothings and some Whigs formed the Constitutional Union Party which ran on a platform based around supporting only the Constitution and the laws of the land.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

won the support of the Republican National Convention

The Republican National Convention (RNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1856 by the Republican Party in the United States. They are administered by the Republican National Committee. The goal o ...

after it became apparent that William Seward had alienated certain branches of the Republican Party. Moreover, Lincoln had been made famous in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates and was well known for his eloquence and his moderate position on slavery.

Lincoln won a majority of votes in the electoral college

An electoral college is a body whose task is to elect a candidate to a particular office. It is mostly used in the political context for a constitutional body that appoints the head of state or government, and sometimes the upper parliament ...

, but only won two-fifths of the popular vote

Popularity or social status is the quality of being well liked, admired or well known to a particular group.

Popular may also refer to:

In sociology

* Popular culture

* Popular fiction

* Popular music

* Popular science

* Populace, the tota ...

. The Democratic vote was split three ways and Lincoln was elected as the 16th president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal government of t ...

.

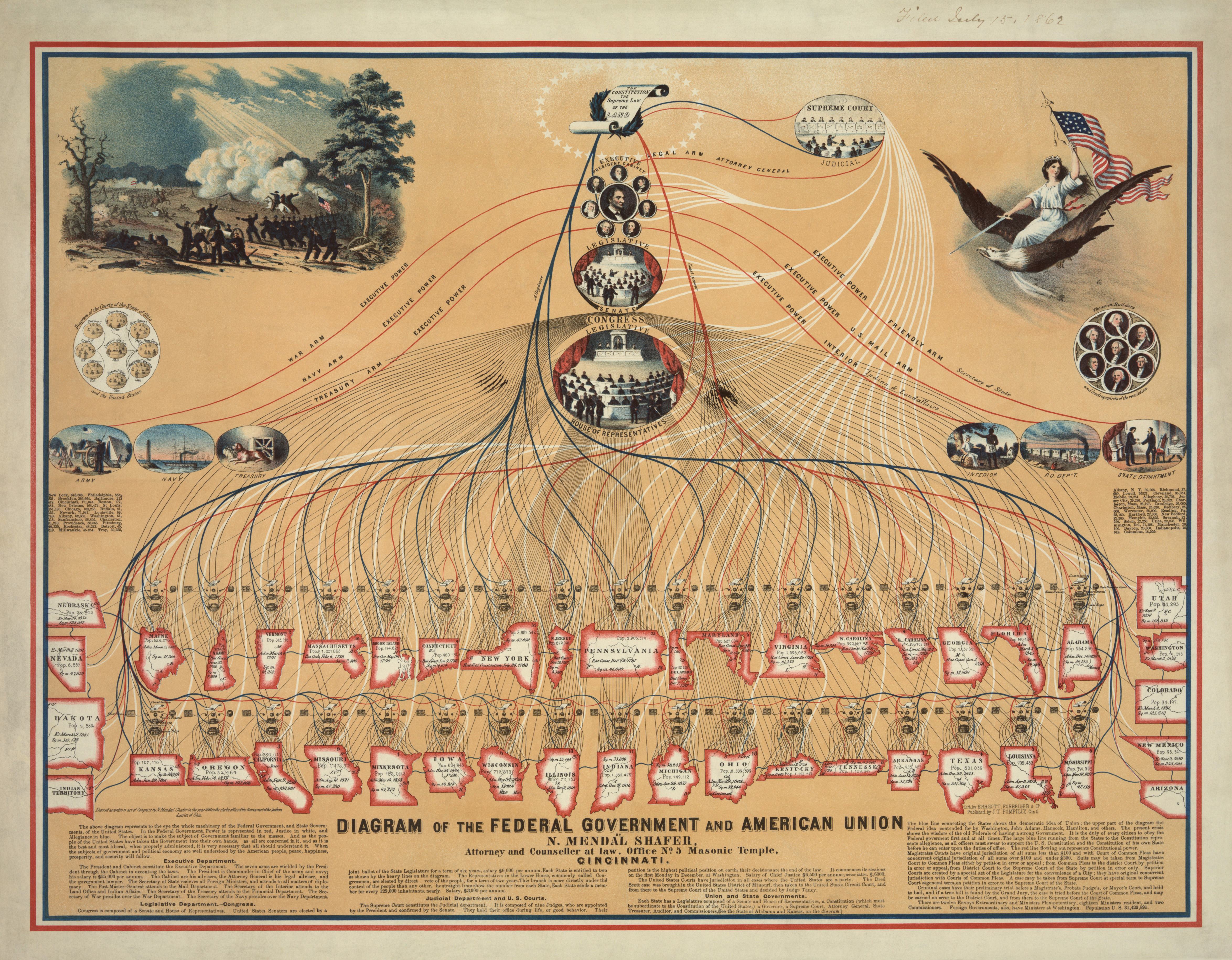

Secession

Lincoln's election in November led to a declaration ofsecession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

by South Carolina on December 20, 1860. Before Lincoln took office in March 1861, six other states had declared their secession from the Union: Mississippi

Mississippi ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Alabama to the east, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, Louisiana to the s ...

(January 9, 1861), Florida

Florida ( ; ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders the Gulf of Mexico to the west, Alabama to the northwest, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the north, the Atlantic ...

(January 10), Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

(January 11), Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

(January 19), Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

(January 26), and Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

(February 1).

Men from both North and South met in Virginia to try to hold together the Union, but the proposals for amending the Constitution were unsuccessful. In February 1861, the seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama. Named for Continental Army major general Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River on the Gulf Coastal Plain. The population was 2 ...

, and formed a new government: the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), also known as the Confederate States (C.S.), the Confederacy, or Dixieland, was an List of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United State ...

. The first Confederate Congress

The Confederate States Congress was both the provisional and permanent legislative assembly/legislature of the Confederate States of America that existed from February 1861 to April/June 1865, during the American Civil War. Its actions were, ...

was held on February 4, 1861, and adopted a provisional constitution. On February 8, 1861, Jefferson Davis

Jefferson F. Davis (June 3, 1808December 6, 1889) was an American politician who served as the only President of the Confederate States of America, president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the Unite ...

was nominated President of the Confederate States

The president of the Confederate States was the head of state and head of government of the unrecognized breakaway Confederate States. The president was the chief executive of the federal government and commander-in-chief of the Confederate A ...

.

Civil War

Fort Sumter

Fort Sumter is a historical Coastal defense and fortification#Sea forts, sea fort located near Charleston, South Carolina. Constructed on an artificial island at the entrance of Charleston Harbor in 1829, the fort was built in response to the W ...

, the federal base in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina, the new Confederate government under President Jefferson Davis ordered General P.G.T. Beauregard to open fire on the fort. It fell two days later, without casualty, spreading the flames of war across America. Immediately, rallies were held in every town and city, north and south, demanding war. Lincoln called for troops to retake lost federal property, which meant an invasion of the South. In response, four more states seceded: Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

(April 17, 1861), Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the West South Central region of the Southern United States. It borders Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, Texas to the southwest, and Oklahoma ...

(May 6, 1861), Tennessee

Tennessee (, ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina t ...

(May 7, 1861), and North Carolina

North Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, South Carolina to the south, Georgia (U.S. stat ...

(May 20, 1861). The four remaining slave states, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

, Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic and South Atlantic states, South Atlantic regions of the United States. It borders Maryland to its south and west, Pennsylvania to its north, New Jersey ...

, Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, and Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

, under heavy pressure from the Federal government did not secede; Kentucky tried, and failed, to remain neutral.

Each side had its relative strengths and weaknesses. The North had a larger population and a far larger industrial base and transportation system. It would be a defensive war for the South and an offensive one for the North, and the South could count on its huge geography, and an unhealthy climate, to prevent an invasion. In order for the North to emerge victorious, it would have to conquer and occupy the Confederate States of America. The South, on the other hand, only had to keep the North at bay until the Northern public lost the will to fight. The Confederacy adopted a military strategy designed to hold their territory together, gain worldwide recognition, and inflict so much punishment on invaders that the North would grow weary of the war and negotiate a peace treaty that would recognize the independence of the CSA. The only point of seizing Washington, or invading the North (besides plunder) was to shock Yankees into realizing they could not win. The Confederacy moved its capital from a safe location in Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama. Named for Continental Army major general Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River on the Gulf Coastal Plain. The population was 2 ...

, to the more cosmopolitan city of Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

, only 100 miles from the enemy capital in Washington. Richmond was heavily exposed, and at the end of a long supply line; much of the Confederacy's manpower was dedicated to its defense. The North had far greater potential advantages, but it would take a year or two to mobilize them for warfare. Meanwhile, everyone expected a short war.

War in the East

The Union assembled an army of 35,000 men (the largest ever seen in North America up to that point) under the command of General

The Union assembled an army of 35,000 men (the largest ever seen in North America up to that point) under the command of General Irvin McDowell

Irvin McDowell (October 15, 1818 – May 4, 1885) was an American army officer. He is best known for his defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run, the first large-scale battle of the American Civil War. In 1862, he was given command of the ...

. With great fanfare, these untrained soldiers set out from Washington DC with the idea that they would capture Richmond in six weeks and put a quick end to the conflict. At the Battle of Bull Run on July 21, however, disaster ensued as McDowell's army was completely routed and fled back to the nation's capitol. Major General George McClellan

George Brinton McClellan (December 3, 1826 – October 29, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 24th governor of New Jersey and as Commanding General of the United States Army from November 1861 to March 186 ...

of the Union was put in command of the Army of the Potomac

The Army of the Potomac was the primary field army of the Union army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was created in July 1861 shortly after the First Battle of Bull Run and was disbanded in June 1865 following the Battle of ...

following the battle on July 26, 1861. He began to reconstruct the shattered army and turn it into a real fighting force, as it became clear that there would be no quick, six-week resolution of the conflict. Despite pressure from the White House, McClellan did not move until March 1862, when the Peninsular Campaign began with the purpose of capturing the capitol of the Confederacy, Richmond, Virginia

Richmond ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. Incorporated in 1742, Richmond has been an independent city (United States), independent city since 1871. ...

. It was initially successful, but in the final days of the campaign, McClellan faced strong opposition from Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a general officers in the Confederate States Army, Confederate general during the American Civil War, who was appointed the General in Chief of the Armies of the Confederate ...

, the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

. From June 25 to July 1, in a series of battles known as the Seven Days Battles

The Seven Days Battles were a series of seven battles over seven days from June 25 to July 1, 1862, near Richmond, Virginia, during the American Civil War. Confederate States Army, Confederate General Robert E. Lee drove the invading Union Army ...

, Lee forced the Army of the Potomac to retreat. McClellan was recalled to Washington and a new army assembled under the command of John Pope.

In August, Lee fought the Second Battle of Bull Run

The Second Battle of Bull Run or Battle of Second Manassas was fought August 28–30, 1862, in Prince William County, Virginia, as part of the American Civil War. It was the culmination of the Northern Virginia Campaign waged by Confederate ...

(Second Manassas) and defeated John Pope's Army of Virginia. Pope was dismissed from command and his army merged with McClellan's. The Confederates then invaded Maryland, hoping to obtain European recognition and an end to the war. The two armies met at Antietam on September 17. This was the single bloodiest day in American history. The Union victory allowed Abraham Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation