history of the pitcairn islands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the

The history of the

After leaving Tahiti on 22 September 1789, Christian sailed ''Bounty'' west in search of a safe haven. He then formed the idea of settling on

After leaving Tahiti on 22 September 1789, Christian sailed ''Bounty'' west in search of a safe haven. He then formed the idea of settling on

After Young succumbed to asthma in 1800, Adams took responsibility for the education and well-being of the nine remaining women and 19 children. Using the ship's Bible from ''Bounty'', he taught literacy and Christianity, and kept peace on the island. This was the situation in February 1808, when the American sealer ''Topaz'' commanded by

After Young succumbed to asthma in 1800, Adams took responsibility for the education and well-being of the nine remaining women and 19 children. Using the ship's Bible from ''Bounty'', he taught literacy and Christianity, and kept peace on the island. This was the situation in February 1808, when the American sealer ''Topaz'' commanded by

Traditionally, Pitcairn Islanders consider that their islands "officially" became a British colony on 30 November 1838, at the same time becoming one of the first territories to extend voting rights to women.

Traditionally, Pitcairn Islanders consider that their islands "officially" became a British colony on 30 November 1838, at the same time becoming one of the first territories to extend voting rights to women.

. ''The World Factbook''. In 1938, the three islands, along with Pitcairn, were incorporated into a single administrative unit called the ''Pitcairn Group of Islands''. By the 1930s and 1940s, diminished shipping and tourism to the island resulted in the residents selling many of the pre-European cultural items and ''Bounty''-related paraphernalia to private individuals for income. In 1940 and 1941, the British government sent Henry Evans Maude and his wife

During the 20th century, most of the chief magistrates have been from the Christian and Young families, and contact with the outside world continued to increase. In 1970 the British high commissioners of New Zealand became the governors of Pitcairn. Since January 2018 the governor has been Laura Clarke, OBE. In 1999 the position of chief magistrate was replaced by the position of mayor. Another change for the community is the decline of the Adventist church, where there are now only eight regular worshippers.

Since the population peaked at 233 in 1937, the island has suffered from emigration, primarily to New Zealand, leaving current population of 56. The Islands rely heavily on tourism and landing fees as their main source of income as well as shipments from New Zealand.

During the 20th century, most of the chief magistrates have been from the Christian and Young families, and contact with the outside world continued to increase. In 1970 the British high commissioners of New Zealand became the governors of Pitcairn. Since January 2018 the governor has been Laura Clarke, OBE. In 1999 the position of chief magistrate was replaced by the position of mayor. Another change for the community is the decline of the Adventist church, where there are now only eight regular worshippers.

Since the population peaked at 233 in 1937, the island has suffered from emigration, primarily to New Zealand, leaving current population of 56. The Islands rely heavily on tourism and landing fees as their main source of income as well as shipments from New Zealand.

Brief history of Pitcairn

Pitcairn - The Early History

As told in contemporary books, reports, letters and other documents. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Pitcairn Islands

The history of the

The history of the Pitcairn Islands

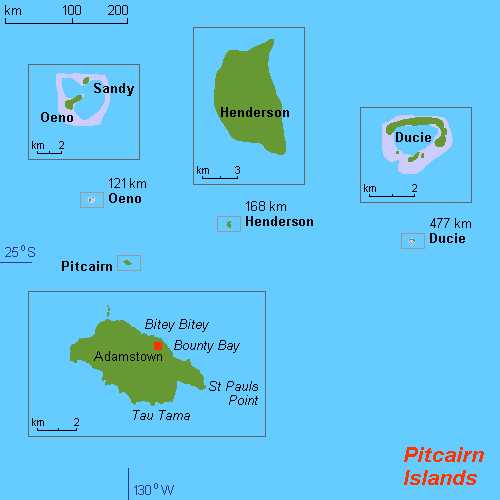

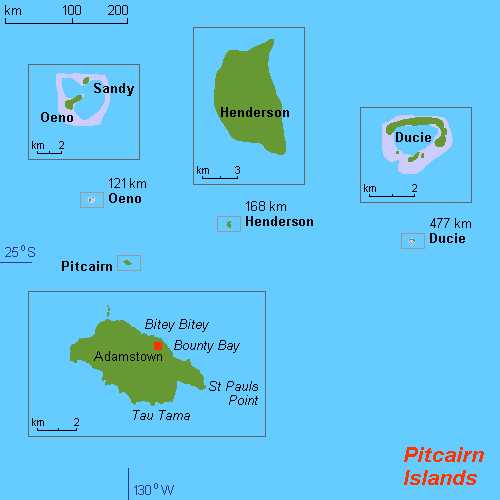

The Pitcairn Islands (; Pitkern: '), officially the Pitcairn, Henderson, Ducie and Oeno Islands, is a group of four volcanic islands in the southern Pacific Ocean that form the sole British Overseas Territory in the Pacific Ocean. The four isl ...

begins with the colonization of the islands by Polynesians

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sou ...

in the 11th century. Polynesian people established a culture that flourished for four centuries and then vanished. They lived on Pitcairn and Henderson Henderson may refer to:

People

*Henderson (surname), description of the surname, and a list of people with the surname

*Clan Henderson, a Scottish clan

Places Argentina

*Henderson, Buenos Aires

Australia

*Henderson, Western Australia

Canada

*He ...

Islands, and on Mangareva Island to the northwest, for about 400 years.

In 1790, nine of the Englishmen from the ''Bounty

Bounty or bounties commonly refers to:

* Bounty (reward), an amount of money or other reward offered by an organization for a specific task done with a person or thing

Bounty or bounties may also refer to:

Geography

* Bounty, Saskatchewan, a gh ...

'' led by Fletcher Christian, along with the 18 native Tahitian men and women settled on Pitcairn Islands and set fire to the ''Bounty''. Christian's group remained undiscovered on Pitcairn until 1808, by which time all but one of the mutineers and all of the male Tahitians were dead. The remaining women and children were led by John Adams.

Polynesian society

The earliest known settlers of the Pitcairn Islands werePolynesians

Polynesians form an ethnolinguistic group of closely related people who are native to Polynesia (islands in the Polynesian Triangle), an expansive region of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. They trace their early prehistoric origins to Island Sou ...

who appear to have settled on Pitcairn and Henderson Islands by at least the 11th Century, and on the more populous Mangareva Island to the northwest, for several centuries. These first inhabitants may have maintained a trading relationship with Mangareva, in which they exchanged basalt, volcanic glass (obsidian

Obsidian () is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock.

Obsidian is produced from felsic lava, rich in the lighter elements s ...

) and oven stones for goods, including coral and pearl shells. Most trade occurred within the Pitcairn Islands; however, material from Pitcairn Island has been discovered on the Tuamotus and Austral Islands in French Polynesia

)Territorial motto: ( en, "Great Tahiti of the Golden Haze")

, anthem =

, song_type = Regional anthem

, song = " Ia Ora 'O Tahiti Nui"

, image_map = French Polynesia on the globe (French Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of Frenc ...

. The alkaline basalt found at Tautama (on the south-east of Pitcairn Island) was used by early Polynesians to create some of the highest quality adzes in Polynesia; however, the adzes were not traded widely, likely due to the remoteness of the islands. It is not certain why this society disappeared, but it is probably related to the deforestation of Mangareva and the subsequent decline of its culture; Pitcairn was not capable of sustaining large numbers of people without a relationship with other populous islands. By the mid-1400s, the trade routes between the islands and French Polynesia had broken down. Important natural resources were exhausted and a period of civil war began on Mangareva, causing the small populations on Henderson and Pitcairn to be cut off and eventually become extinct.

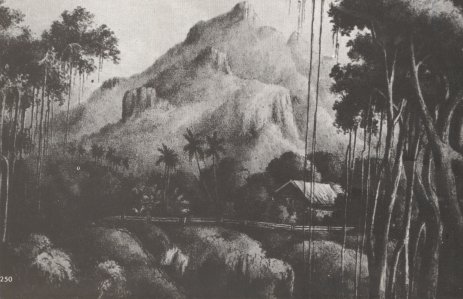

The islands were uninhabited when they were rediscovered by the Portuguese explorer Pedro Fernandes de Queirós, working in the employ of Spain, in January 1606. The British rediscovered the island on 3 July 1767 on a voyage led by Captain Philip Carteret, and named it after the fifteen-year-old Robert Pitcairn

Robert Pitcairn (May 6, 1836 – July 25, 1909) was a Scottish-American railroad executive who headed the Pittsburgh Division of the Pennsylvania Railroad in the late 19th century. He was the brother of the PPG Industries, Pittsburgh Plate Glass ...

, a son of John Pitcairn, who was the crew member who first spotted the island; he was lost at sea three years later. Carteret, who sailed without the newly-invented marine chronometer, charted the island at , and although the latitude was reasonably accurate, his recorded longitude was incorrect by about 3° () west of the island. When the ''Bounty'' mutineers arrived on Pitcairn, it was uninhabited; however, a large number of archaeological items remained, such as marae, tiki carvings, adzes and adze flakes, rock carvings and petroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s.

English and Tahitian settlement

After leaving Tahiti on 22 September 1789, Christian sailed ''Bounty'' west in search of a safe haven. He then formed the idea of settling on

After leaving Tahiti on 22 September 1789, Christian sailed ''Bounty'' west in search of a safe haven. He then formed the idea of settling on Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff coastline. Unlike many other ...

, far to the east of Tahiti; the island had been reported in 1767, but its exact location was never verified. After months of searching, Christian rediscovered the island on 15 January 1790, east of its recorded position. This longitudinal error contributed to the mutineers' decision to settle on Pitcairn.

The group consisted of Englishmen Fletcher Christian, Ned Young

The complement of , the Royal Navy ship on which a historic mutiny occurred in the south Pacific on 28 April 1789, comprised 46 men on its departure from England in December 1787 and 44 at the time of the mutiny, including her commander Lieute ...

, John Adams, Matthew Quintal

The complement of , the Royal Navy ship on which a historic mutiny occurred in the south Pacific on 28 April 1789, comprised 46 men on its departure from England in December 1787 and 44 at the time of the mutiny, including her commander Lieute ...

, William McCoy, William Brown, Isaac Martin, John Mills and John Williams; six Polynesian men (Manarii/Menalee, Niau/Nehou, and Teirnua/Te Moa from Tahiti; Taroamiva/Tetahiti and Oher/Hu from Tubuai; and Taruro/Talalo from Raiatea by way of Tahiti) and twelve Tahitian women (Maimiti/Isabella, Teehuteatuaonoa/Jenny, Teraura/Susanah, Teio/Mary, Vahineatua/Bal'hadi/Prudence, Obuarei/Puarai, Tevarua/Sarah, Teatuahitea/Sarah, Faahotu/Fasto, Toofaiti/Hutia/Nancy, Mareva, and Tinafornea) as well as a Tahitian baby girl named Sarah/Sally, daughter of Teio, who would become a respected person in the community.

On arrival, the ship was unloaded and stripped of most of its masts and spars, for use on the island. On 23 January, five days after their arrival, as the seamen discussed whether to burn the ship, Quintal set the ship ablaze and destroyed it, either as an agreed-upon precaution against discovery or as an unauthorised act. There was now no means of escape.

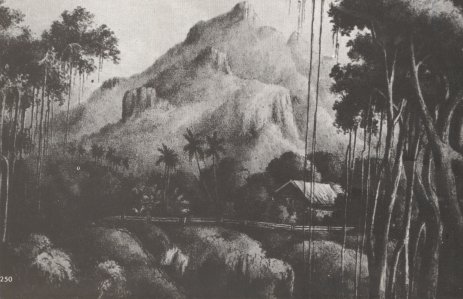

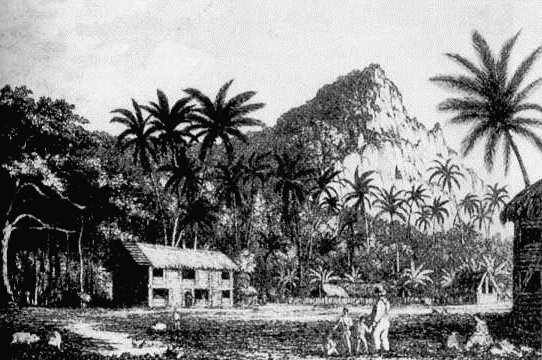

The island proved an ideal haven for the mutineers—uninhabited and virtually inaccessible, with plenty of food, water, and fertile land. For a while, the mutineers and Tahitians existed peaceably. Christian settled down with Isabella; a son, Thursday October Christian, was the first child born on the island, and others followed. Christian's authority as leader gradually diminished, and he became prone to long periods of brooding and introspection.

Racial tensions

Gradually, tensions and rivalries arose over the increasing extent to which the Europeans regarded the Tahitians as their property, in particular the women who, according to Alexander, were "passed around from one 'husband' to the other". The lower-caste Tahitian man, Hu, was often a victim of the white men's beatings and abuse. Martin treated the islanders including his wife with disdain, causing increasing discord. McCoy figured out how to distill brandy from ti-root and built a still. He, Quintal, and some of the women were continually drunk. In 1791, after working side-by-side with the islanders to perform the daily tasks that sustained the colony, some of the seamen decided to loaf in the shade all day while they coerced the Polynesian men to complete the tasks too hard for the women to perform. Quintal and McCoy required the unmarried man Te Moa to do all their work, and Martin and Mills similarly abused the other lower-caste islander, Nihau. McCoy and Quintal often abused and bullied both the Polynesian women and men. Rosalind Young, a descendant ofNed Young

The complement of , the Royal Navy ship on which a historic mutiny occurred in the south Pacific on 28 April 1789, comprised 46 men on its departure from England in December 1787 and 44 at the time of the mutiny, including her commander Lieute ...

, relayed a story handed down to her that Tevarua went fishing one day but failed to catch enough fish to satisfy Quintal. He punished her by biting off her ear. He may have been drunk at the time, because he and William McCoy were drunk most of the time, consuming McCoy's brandy. Tevarua fell – or, some believe, killed herself, by leaping off a cliff in 1799. The two Tahitian noblemen, Minarii and Tetahiti, still enjoyed lives of relative independence and dignity.

John Williams had sex with Hutia, the wife of Tararu, and the Tahitian leader Minarii attacked him over this insult to Minarii's family. William's wife Fasto died soon after, possibly by suicide, after learning of her husband's infidelity. Hu and Tararu plotted to kill the white men in retribution. Hu tried unsuccessfully to kill Martin by pushing him off a cliff. After Fasto died, Williams took Hutia away from Tararu to live with him, and Tararu tried and failed to murder Williams. Hutia decided to poison Tararu in retaliation and unwittingly killed both Tararu and Hu.

McCoy decided to put to a vote a proposal that the arable land be divided among the seamen, excluding the Polynesians. Christian strongly objected. He reminded the Englishmen that on Tahiti, where Minarii and Tetahiti had been chiefs, landless men were deemed outcasts. McCoy's proposal carried by a vote of five to four. When Tetahiti learned of the vote, he went to Minarii to discuss the issue with him, only to find him standing near a pile of smoldering ashes. Quintal had burned the chieftain's new home.

Massacre day

On 20 September 1793, the four remaining Polynesian men stole muskets and set out to kill all of the Englishmen. Within hours they beheaded Martin and Mills, shot Williams and Brown dead, and fatally wounded Christian in a carefully executed series of murders. Christian was set upon while working in his fields, first shot and then butchered with an axe; his last words, supposedly, were: "Oh, dear!" Three of the Englishmen's wives took revenge, killing Te Moa and Niuha.Teraura

Teraura, also Susan or Susannah Young ( – July 1850), was a Tahitian woman who settled on Pitcairn Island with the ''Bounty'' Mutineers. She took part in Ned Young's plot to murder male Polynesians who had travelled on HMS ''Bounty'' and kill ...

, the wife of Ned Young, beheaded Tetahiti while he slept. Quintal killed Minarii in a violent fight.

Adams leads women and children

Young and Adams assumed leadership and secured a tenuous calm disrupted by the drunken behaviour of McCoy and Quintal. The two men and some of the women spent their days in an alcoholic stupor. Some of the women attempted to leave the island in a makeshift boat but could not launch it successfully. On 20 April 1798, McCoy attached a rock to his neck with a rope and leapt over a cliff to his death. Quintal became increasingly erratic. He demanded to take Isabella, Fletcher Christian's widow, as his wife, and threatened to kill Christian's children if his demands were not granted. Ned Young and John Adams invited him to Young's home. There they overpowered him, and killed him with an axe. Young and Adams became interested in Christianity, and Young taught Adams to read using the Bounty's Bible. Young died of an asthma attack in 1800. Adams lived until 1829.Contact reestablished

After Young succumbed to asthma in 1800, Adams took responsibility for the education and well-being of the nine remaining women and 19 children. Using the ship's Bible from ''Bounty'', he taught literacy and Christianity, and kept peace on the island. This was the situation in February 1808, when the American sealer ''Topaz'' commanded by

After Young succumbed to asthma in 1800, Adams took responsibility for the education and well-being of the nine remaining women and 19 children. Using the ship's Bible from ''Bounty'', he taught literacy and Christianity, and kept peace on the island. This was the situation in February 1808, when the American sealer ''Topaz'' commanded by Mayhew Folger

Mayhew Folger (March 9, 1774 – September 1, 1828) was an American whaler who captained the sealing ship ''Topaz'' that rediscovered the Pitcairn Islands in 1808, while one of 's mutineers was still living.

Early life and family

Mayhew was born ...

came unexpectedly upon Pitcairn, landed, and discovered the, by then, thriving community. News of ''Topaz''s discovery did not reach Britain until 1810, when it was overlooked by an Admiralty preoccupied by war with France.

In 1814, two British warships, and HMS ''Tagus'', chanced upon Pitcairn. Among those who greeted them were Thursday October Christian and George Young (Edward Young's son). The captains, Sir Thomas Staines and Philip Pipon, reported that Christian's son displayed "in his benevolent countenance, all the features of an honest English face". On shore they found a population of 46 mainly young islanders led by Adams, upon whom the islanders' welfare was wholly dependent, according to the captains' report. After receiving Staines's and Pipon's report, the Admiralty decided to take no action.

Henderson Island was rediscovered on 17 January 1819 by British Captain James Henderson of the British East India Company ship ''Hercules''. Captain Henry King, sailing on ''Elizabeth'', landed on 2 March to find the king's colours already flying. His crew scratched the name of their ship into a tree. Oeno Island was discovered on 26 January 1824 by American captain George Worth aboard the whaler .

In 1832, a Church Missionary Society missionary arrived. He reported that by March 1833, he had founded a Temperance Society to combat drunkenness, a "Maundy Thursday Society", a monthly prayer meeting, a juvenile society, a Peace Society and a school.

In the following years, many ships called at Pitcairn Island and heard Adams's various stories of the foundation of the Pitcairn settlement. Adams died in 1829, honoured as the founder and father of a community that became celebrated over the next century as an exemplar of Victorian morality. Over the years, many recovered ''Bounty'' artefacts have been sold by islanders as souvenirs; in 1999, the Pitcairn Project was established by a consortium of Australian academic and historical bodies, to survey and document all the material remaining on-site, as part of a detailed study of the settlement's development.

The Pitcairners were visited often by ships. During the 1820s, three British adventurers named John Buffett, John Evans and George Nobbs settled on the island and married children of the mutineers. Following Adams's death in 1829, a power vacuum emerged. Nobbs, a veteran of the British and Chilean navies, was Adams's chosen successor, but Buffett and Thursday October Christian, the son of Fletcher and the first child born on the island, who had the task of greeting visiting ships, were also important leaders during this time.

Resettlement

Fearing overcrowding, the islanders requested the British government transport them to Tahiti. In 1831 the British government relocated the islanders there. But they found it unlike the home they remembered, full of "immorality, saloons, vile dances, gambling, and scarlet women." The descendants could not adapt to the changes in Tahiti, and a dozen people, including Thursday October Christian, had died of disease. The islanders were now even more leaderless, as alcoholism became a problem. They returned to Pitcairn after six months aboard the ship ofWilliam Driver

Old Glory is a nickname for the flag of the United States. The original "Old Glory" was a flag owned by the 19th-century American sea captain William Driver (March 17, 1803 – March 3, 1886), who flew the flag during his career at sea and ...

.

New settlers

In 1832, an adventurer namedJoshua Hill Joshua or Josh Hill may refer to:

* Joshua Hill (baseball) (born 1983), Australian baseball player

* Joshua Hill (Pitcairn Island leader) (1773–c. 1844), American adventurer

* Joshua Hill (politician) (1812–1891), American politician

* Josh ...

, claiming to be an agent of Britain, arrived on the island and was elected leader, styling himself President of the Commonwealth of Pitcairn. He ordered Buffett, Evans and Nobbs to be exiled, banned alcohol and ordered imprisonments for the slightest infractions. He was eventually driven off the island in 1838, and a British ship captain helped the islanders draw up a law code. The islanders set up a system whereby they would elect a chief magistrate every year as the leader of the island.

Other important positions on the island were those of schoolmaster, doctor and pastor. Nobbs, however, was the effective leader of the island. Under this law code, Pitcairn became the first British colony

The British Overseas Territories (BOTs), also known as the United Kingdom Overseas Territories (UKOTs), are fourteen territories with a constitutional and historical link with the United Kingdom. They are the last remnants of the former Bri ...

in the Pacific and also the second country in the world, after Corsica

Corsica ( , Upper , Southern ; it, Corsica; ; french: Corse ; lij, Còrsega; sc, Còssiga) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the 18 regions of France. It is the fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of ...

under Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; french: link=no, Pascal Paoli; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Genoese and later ...

in 1755, to give women the right to vote.

British colony

Traditionally, Pitcairn Islanders consider that their islands "officially" became a British colony on 30 November 1838, at the same time becoming one of the first territories to extend voting rights to women.

Traditionally, Pitcairn Islanders consider that their islands "officially" became a British colony on 30 November 1838, at the same time becoming one of the first territories to extend voting rights to women.

Move to Norfolk Island

By the mid-1850s the Pitcairn community was outgrowing the island and they appealed to Queen Victoria for help. Queen Victoria offered themNorfolk Island

Norfolk Island (, ; Norfuk: ''Norf'k Ailen'') is an external territory of Australia located in the Pacific Ocean between New Zealand and New Caledonia, directly east of Australia's Evans Head and about from Lord Howe Island. Together with ...

. In 1856, all 163 residents boarded ''Morayshire'' and crossed the Pacific to Norfolk Island, formerly a prison colony, an isolated rock between the North Island of New Zealand and New Caledonia. They arrived on 8 June after a miserable five-week trip. Eighteen months later, sixteen returned, and they were followed by 27 others in 1864.

In 1858, while the island was uninhabited, survivors of the shipwreck of the clipper

A clipper was a type of mid-19th-century merchant sailing vessel, designed for speed. Clippers were generally narrow for their length, small by later 19th century standards, could carry limited bulk freight, and had a large total sail area. "C ...

''Wild Wave'' spent several months there until rescued by . These visitors had dismantled some houses for wood and nails and had vandalised John Adams' grave. The island was also nearly annexed by France, whose government did not realise that the island had just been inhabited. George Nobbs and John Buffett stayed on Norfolk Island. By this time, an American family named Warren settled on Pitcairn Island.

During the 1860s further immigration to the island was banned. In 1886 the Seventh-day Adventist layman John Tay

John I. Tay (1832 – 8 January 1892) was a Seventh-day Adventist missionary who was known for his pioneering work in the South Pacific. It was through his efforts that most of the inhabitants of Pitcairn Island were converted to Adventism, and th ...

visited Pitcairn and persuaded most of the islanders to convert from the Church of England to his faith. He returned in 1890 on the missionary schooner with an ordained minister to perform baptisms. Since then, the majority of Pitcairn Islanders have been Adventists.

Important leaders of Pitcairn during this time were Thursday October Christian II

Thursday October Christian II (1 October 1820 – 27 May 1911)"thePeerage.com - Gonzalo, Rey de Sobrarbe and others" (family tree), April 16, 2006, ''thePeerage.com'' webpage was a Pitcairn Islands political leader. He was the grandson of Fl ...

, Simon Young and James Russell McCoy

James Russell McCoy (4 September 1845 – 14 February 1924) served as Magistrate of the British Overseas Territory of Pitcairn Island 7 times, between 1870 and 1904. McCoy was among the first wave of settlers to return to Pitcairn from Norf ...

. McCoy, who was sent to England for education as a child, spent much of his later life on missionary journeys. In 1887, Britain officially annexed the island, and it was officially put under the jurisdiction of the governors of Fiji

Fiji ( , ,; fj, Viti, ; Fiji Hindi: फ़िजी, ''Fijī''), officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists ...

.

Late 19th century

visited Pitcairn Island on 18 April 1881 and "found the people very happy and contented, and in perfect health". At that time the population was 96, an increase of six since the visit of Admiral de Horsey in September 1878. Stores had recently been delivered from friends in England, including two whale-boats and Portland cement, which was used to make the reservoir watertight. HMS ''Thetis'' gave the islanders of biscuits, of candles, and 100 lb of soap and clothing to the value of £31, donated by the ship's company. An American trading ship called ''Venus'' had recently bestowed a supply of cotton seed, to provide the islanders with a crop for future trade.20th century

The islands of Henderson, Oeno and Ducie were annexed by Britain in 1902: Henderson on 1 July, Oeno on 10 July, and Ducie on 19 December. The population peaked at 233 in 1937. It has since decreased owing to emigration, primarily toAustralia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

and New Zealand.Country Comparison: Population. ''The World Factbook''. In 1938, the three islands, along with Pitcairn, were incorporated into a single administrative unit called the ''Pitcairn Group of Islands''. By the 1930s and 1940s, diminished shipping and tourism to the island resulted in the residents selling many of the pre-European cultural items and ''Bounty''-related paraphernalia to private individuals for income. In 1940 and 1941, the British government sent Henry Evans Maude and his wife

Honor Maude

Honor Courtney Maude (née King; Wem, Shropshire; 10 July 1905 – 15 April 2001, Canberra, Australia) was a British-Australian authority on Oceanic string figures,

to the islands to modernise the government, and to establish a post office and issue stamps in order to generate revenue for the people.

Current society

During the 20th century, most of the chief magistrates have been from the Christian and Young families, and contact with the outside world continued to increase. In 1970 the British high commissioners of New Zealand became the governors of Pitcairn. Since January 2018 the governor has been Laura Clarke, OBE. In 1999 the position of chief magistrate was replaced by the position of mayor. Another change for the community is the decline of the Adventist church, where there are now only eight regular worshippers.

Since the population peaked at 233 in 1937, the island has suffered from emigration, primarily to New Zealand, leaving current population of 56. The Islands rely heavily on tourism and landing fees as their main source of income as well as shipments from New Zealand.

During the 20th century, most of the chief magistrates have been from the Christian and Young families, and contact with the outside world continued to increase. In 1970 the British high commissioners of New Zealand became the governors of Pitcairn. Since January 2018 the governor has been Laura Clarke, OBE. In 1999 the position of chief magistrate was replaced by the position of mayor. Another change for the community is the decline of the Adventist church, where there are now only eight regular worshippers.

Since the population peaked at 233 in 1937, the island has suffered from emigration, primarily to New Zealand, leaving current population of 56. The Islands rely heavily on tourism and landing fees as their main source of income as well as shipments from New Zealand.

Sex crimes convictions

On 30 September 2004, seven male residents of Pitcairn, about one-third of the male population, and six others living abroad, were tried on 55 sex-related offences. Among the accused was Steve Christian, Pitcairn's Mayor, who faced several charges of rape, indecent assault, and child abuse. On 25 October 2004, six men were convicted, including Steve Christian. A seventh, the island's former MagistrateJay Warren

Jay Calvin Warren (born 29 July 1956) is a political figure from the Pacific territory of the Pitcairn Islands.

Political roles

Jay Warren was elected mayor of the last remaining British dependency in Oceania in the general election held on 15 ...

, was acquitted. In 2004, the islanders surrendered about 20 firearms ahead of the sexual assault trials.

After the six men lost their final appeal, the British government set up a prison on the island at Bob's Valley. The men began serving their sentences in late 2006. By 2010, all had served their sentences or been granted home detention status.

In 2010, mayor Mike Warren was charged with 25 counts of possessing child pornography on his computer. In 2016, Warren was found guilty of downloading more than 1,000 images and videos of child sexual abuse. Warren began downloading the images some time after the 2004 sexual assault convictions. During the time he downloaded the images, he was working in child protection. Warren was also convicted of engaging in a "sex chat" with someone he believed was a 15-year-old girl.

First female Mayor

Charlene Warren-Peu

Charlene Evelyn Dolly Warren-Peu (born 9 June 1979)Who Are the Pitcairners? ...

(born 9 June 1979) was elected in 2019 as Mayor of the Pitcairn Islands. She is the first woman to hold the position on a permanent basis. She previously served as Deputy Mayor and was on the Island Council.

Footnotes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * *External links

Brief history of Pitcairn

Pitcairn - The Early History

As told in contemporary books, reports, letters and other documents. {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of The Pitcairn Islands