History Of The Episcopal Church (United States) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the

Where the Church of England was established,

Where the Church of England was established,

Embracing the symbols of the British presence in the American colonies, such as the monarchy, the episcopate, and even the language of the ''Book of Common Prayer'', the Church of England almost drove itself to extinction during the upheaval of the

Embracing the symbols of the British presence in the American colonies, such as the monarchy, the episcopate, and even the language of the ''Book of Common Prayer'', the Church of England almost drove itself to extinction during the upheaval of the

When peace returned in 1783, with the ratification of the new

When peace returned in 1783, with the ratification of the new  That same year, clerical and lay representatives from seven of the nine states south of Connecticut held the first General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. They drafted a constitution, an American ''Book of Common Prayer'', and planned for the consecration of additional bishops. In 1787, two priests— William White of Pennsylvania and

That same year, clerical and lay representatives from seven of the nine states south of Connecticut held the first General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. They drafted a constitution, an American ''Book of Common Prayer'', and planned for the consecration of additional bishops. In 1787, two priests— William White of Pennsylvania and

American bishops such as William White (1748–1836) continued to provide models of civic involvement, while newly consecrated bishops such as

American bishops such as William White (1748–1836) continued to provide models of civic involvement, while newly consecrated bishops such as

When the

When the

Women missionaries, while excluded from ordained ministry, staffed the schools and hospitals. The Woman's Auxiliary was established in 1871 and eventually became the major source of funding and personnel for the church's mission work.Roozen 2005, p. 191.

James Theodore Holly became the first African-American bishop on November 8, 1874. As Bishop of Haiti, Holly was the first African American to attend the

Women missionaries, while excluded from ordained ministry, staffed the schools and hospitals. The Woman's Auxiliary was established in 1871 and eventually became the major source of funding and personnel for the church's mission work.Roozen 2005, p. 191.

James Theodore Holly became the first African-American bishop on November 8, 1874. As Bishop of Haiti, Holly was the first African American to attend the

In 1940, the Episcopal Church's coat-of-arms was adopted. This is based on the

In 1940, the Episcopal Church's coat-of-arms was adopted. This is based on the

Acts of Convention: Resolution #1997-A053, Implement Mandatory Rights of Women Clergy under Canon Law

Retrieved 2008-10-31.

Acts of Convention: Resolution #1991-A104, Affirm the Church's Teaching on Sexual Expression, Commission Congregational Dialogue, and Direct Bishops to Prepare a Pastoral Teaching

Retrieved 2008-10-31. In 1994, the GC determined that church membership would not be determined on "marital status, sex, or sexual orientation". The first openly gay priest, Robert Williams, was ordained by

The first openly homosexual bishop,

The first openly homosexual bishop,

Resolution C056

. Retrieved August 18, 2010. The same General Convention also voted that "any ordained ministry" is open to gay men and lesbians.Laurie Goodstei

''

in JSTOR

* Brittain, Christopher Craig. ''A Plague on Both Their Houses: Liberal VS Conservative Christians and the Divorce of the Episcopal Church USA'' (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015). * Butler, Diana Hochstedt.''Standing against the Whirlwind: Evangelical Episcopalians in Nineteenth-Century America.'' (1996) * Cross, Arthur Lyon. ''The Anglican episcopate and the American colonies'' (1902)

online

* Greene, Evarts B. "The Anglican Outlook on the American Colonies in the Early Eighteenth Century." ''American Historical Review'' 20#1 (1914): 64–85

in JSTOR

* Hein, David, and Gardiner H. Shattuck Jr. ''The Episcopalians''. (2005). * Hein, David. ''Noble Powell and the Episcopal Establishment in the Twentieth Century''. (2001) * Holmes, David L. ''A Brief History of the Episcopal Church''. (1993). * Jones, Ronald W. "Christian Social Action and the Episcopal Church in Saint Louis, Mo: 1880-1920." ''Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church'' 45.3 (1976): 253–274

in JSTOR

* Kirkpatrick, Frank G. ''The Episcopal Church in crisis: How sex, the bible, and authority are dividing the faithful'' (Greenwood, 2008). * Painter, Bordon W. "The Vestry in Colonial New England." ''Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church'' 44#4 (1975): 381–408

in JSTOR

* Prichard, Robert W., ed. ''Readings from the History of the Episcopal Church''. (1986). * Shattuck, Gardiner H. ''Episcopalians and Race: Civil War to Civil Rights''. (2003) * Tarter, Brent. "Reflections on the Church of England in Colonial Virginia," ''Virginia Magazine of History and Biography,'' Vol. 112, No. 4 (2004), pp. 338–37

in JSTOR

* Wall, John N. ''A Dictionary for Episcopalians''. (2000). * Waukechon, John Frank. "The Forgotten Evangelicals: Virginia Episcopalians, 1790–1876". ''Dissertation Abstracts International,'' 2001, Vol. 61 Issue 8, pp 3322–3322 * Woolverton, John Frederick. Colonial Anglicanism in North America. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1984.

New Georgia Encyclopedia article on the Episcopal Church in the U.S. South

in JSTOR

* Mullin, Robert Bruce. "Trends in the Study of the History of the Episcopal Church," ''Anglican and Episcopal History,'' June 2003, Vol. 72 Issue 2, pp 153–165

in JSTOR

Episcopal Church in the United States of America

The Episcopal Church, based in the United States with additional dioceses elsewhere, is a member church of the worldwide Anglican Communion. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is divided into nine provinces. The presiding bishop o ...

has its origins in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, a church which stresses its continuity with the ancient Western church and claims to maintain apostolic succession

Apostolic succession is the method whereby the ministry of the Christian Church is held to be derived from the apostles by a continuous succession, which has usually been associated with a claim that the succession is through a series of bish ...

. Its close links to the Crown led to its reorganization on an independent basis in the 1780s. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was characterized sociologically by a disproportionately large number of high status Americans as well as English immigrants; for example, more than a quarter of all presidents of the United States

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. The officeholder leads the executive branch of the federal government and ...

have been Episcopalians (''see List of United States Presidential religious affiliations''). Although it was not among the leading participants of the abolitionist movement

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

in the early 19th century, by the early 20th century its social engagement had increased to the point that it was an important participant in the Social Gospel

The Social Gospel is a social movement within Protestantism that aims to apply Christian ethics to social problems, especially issues of social justice such as economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, racial tensions, slums, unclean envir ...

movement, though it never provided much support for the Prohibitionist movement. Like other mainline churches in the United States, its membership decreased from the 1960s. This was also a period in which the church took a more open attitude on the role of women and toward homosexuality, while engaging in liturgical revision parallel to that of the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

in the post Vatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions), each lasting between 8 and 1 ...

era.

Colonial origins (1607–1775)

The Church of England in theAmerican colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

began with the founding of Jamestown, Virginia

The Jamestown settlement in the Colony of Virginia was the first permanent English settlement in the Americas. It was located on the northeast bank of the James (Powhatan) River about southwest of the center of modern Williamsburg. It was ...

, in 1607 under the charter of the Virginia Company of London

The London Company, officially known as the Virginia Company of London, was a division of the Virginia Company with responsibility for colonizing the east coast of North America between latitudes 34° and 41° N.

History Origins

The territor ...

. It grew slowly throughout the colonies along the east coast becoming the established church

A state religion (also called religious state or official religion) is a religion or creed officially endorsed by a sovereign state. A state with an official religion (also known as confessional state), while not secular, is not necessarily a t ...

in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

in 1609, the lower four counties of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

in 1693, Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

in 1702, South Carolina

)''Animis opibusque parati'' ( for, , Latin, Prepared in mind and resources, links=no)

, anthem = " Carolina";" South Carolina On My Mind"

, Former = Province of South Carolina

, seat = Columbia

, LargestCity = Charleston

, LargestMetro = ...

in 1706, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

in 1730, and Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

in 1758.Roozen, David A.; James R. Nieman, Editors (2005). ''Church, Identity, and Change: Theology and Denominational Structures in Unsettled Times''. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. . p. 188. By 1700, the Church of England's greatest strength was in Virginia and Maryland.

The overseas development of the Church of England in British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English overseas possessions, English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland (island), Newfound ...

challenged the insular view of the church at home. The editors of the 1662 ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'' found that they had to address the spiritual concerns of the contemporary adventurer. In the 1662 Preface, the editors note:

In 1649, Parliament granted a charter to found a missionary organization called the "Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in New England (also known as the New England Company or Company for Propagation of the Gospel in New England and the parts adjacent in America) is a British charitable organization created to promote ...

" or the "New England Society", for short. After 1702, the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts

A society is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction, or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. Societi ...

(SPG) began missionary activity throughout the colonies.

Where the Church of England was established,

Where the Church of England was established, parishes

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

received financial support from local taxes. With these funds, vestries

A vestry was a committee for the local secular and ecclesiastical government for a parish in England, Wales and some English colonies which originally met in the vestry or sacristy of the parish church, and consequently became known colloquially ...

controlled by local elites were able to build and operate churches as well as to conduct poor relief

In English and British history, poor relief refers to government and ecclesiastical action to relieve poverty. Over the centuries, various authorities have needed to decide whose poverty deserves relief and also who should bear the cost of hel ...

, maintain the roads, and other civic functions. The ministers were few, the glebe

Glebe (; also known as church furlong, rectory manor or parson's close(s))McGurk 1970, p. 17 is an area of land within an ecclesiastical parish used to support a parish priest. The land may be owned by the church, or its profits may be reserved ...

s small, the salaries inadequate, and the people quite uninterested in religion, as the vestry became in effect a kind of local government. One historian has explained the workings of the parish:

From 1635, the vestries and the clergy were loosely under the diocesan authority of the Bishop of London

A bishop is an ordained clergy member who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution.

In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance of dioceses. The role or office of bishop is ca ...

. During the English Civil War

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Parliamentarians (" Roundheads") and Royalists led by Charles I ("Cavaliers"), mainly over the manner of England's governance and issues of re ...

, the episcopate was under attack, and the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, William Laud

William Laud (; 7 October 1573 – 10 January 1645) was a bishop in the Church of England. Appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Charles I in 1633, Laud was a key advocate of Charles I's religious reforms, he was arrested by Parliament in 1640 ...

, was beheaded in 1645. Thus, the formation of a North American diocesan structure was hampered and hindered. In 1660, the clergy of Virginia petitioned for a bishop to be appointed to the colony; the proposal was vigorously opposed by powerful vestrymen, wealthy planters, who foresaw their interests being curtailed. Subsequent proposals from successive Bishops of London for the appointment of a resident suffragan bishop

A suffragan bishop is a type of bishop in some Christian denominations.

In the Anglican Communion, a suffragan bishop is a bishop who is subordinate to a metropolitan bishop or diocesan bishop (bishop ordinary) and so is not normally jurisdiction ...

, or another form of office with delegated authority to perform episcopal functions, met with equally robust local opposition. No bishop was ever appointed.

The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, with the support of the Bishop of London, wanted a bishop for the colonies. Strong opposition arose in the South, where a bishop would threaten the privileges of the lay vestry. Opponents conjured up visions of "episcopal palaces, or pontifical revenues, of spiritual courts, and all the pomp, grandeur, luxury and regalia of an American Lambeth". According to Patricia Bonomi, 'John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

would later claim that "the apprehension of Episcopacy" contributed as much as any other cause to the American Revolution, capturing the attention "not only of the inquiring mind, but of the common people... . The objection was not merely to the office of a bishop, though even that was dreaded, but to the authority of parliament, on which it must be founded"'.

Revolution and reorganization (1775–1800)

American Revolution (1775–1783)

Embracing the symbols of the British presence in the American colonies, such as the monarchy, the episcopate, and even the language of the ''Book of Common Prayer'', the Church of England almost drove itself to extinction during the upheaval of the

Embracing the symbols of the British presence in the American colonies, such as the monarchy, the episcopate, and even the language of the ''Book of Common Prayer'', the Church of England almost drove itself to extinction during the upheaval of the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

. Anglicans leaders realized, in the words of William Smith's 1762 report to the Bishop of London that, "The Church is the firmest Basis of Monarchy and the English Constitution." The danger he saw was that if dissenters of "more Republican ... Principles ith

The Ith () is a ridge in Germany's Central Uplands which is up to 439 m high. It lies about 40 km southwest of Hanover and, at 22 kilometres, is the longest line of crags in North Germany.

Geography

Location

The Ith is immediatel ...

little affinity to the established Religion and manners" of England ever gained the upper hand, the colonists might begin to think of "Independency and separate Government". Thus "in a Political as well as religious view", Smith stated emphatically, the church should be strengthened by an American bishop and the appointment of "prudent Governors who are friends of our Establishment". However, republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

was rapidly gaining strength and opposition to an Anglican bishop in America was fierce.

More than any other denomination, the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

divided both clergy and laity of the Church of England in America, and opinions covered a wide spectrum of political views: Patriots, conciliators, and Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

. On one hand, Patriots saw the Church of England as synonymous with "Tory

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. Th ...

" and " redcoat". On the other hand, about three-quarters of the signers of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

were nominally Anglican laymen, including Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, William Paca

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

, and George Wythe

George Wythe (; December 3, 1726 – June 8, 1806) was an American academic, scholar and judge who was one of the Founding Fathers of the United States. The first of the seven signatories of the United States Declaration of Independence from ...

, not to mention commander-in-chief George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

. A large fraction of prominent merchants and royal appointees were Anglicans and loyalists. About 27 percent of Anglican priests nationwide supported independence, especially in Virginia. Almost 40 percent (approaching 90 percent in New York and New England) were Loyalists. Out of 55 Anglican clergy in New York and New England, only three were Patriots, two of those being from Massachusetts. In Maryland, of the 54 clergy in 1775, only 16 remained to take oaths of allegiance to the new government.

Amongst the clergy, more or less, the northern clergy were Loyalist and the southern clergy were Patriot. Partly, their pocketbook can explain clergy sympathies, as the New England colonies did not establish the Church of England and clergy depended on their SPG stipend rather than their parishioners' gifts, so that when war broke out in 1775, these clergy looked to England for both their paycheck and their direction. Where the Church of England was established, mainly the southern colonies, financial support was local and loyalties were local. Of the approximately three hundred clergy in the Church of England in America between 1776 and 1783, over 80 percent in New England, New York, and New Jersey were Loyalists. This is in contrast to the less than 23 percent Loyalist clergy in the four southern colonies. In two northern colonies, only one priest was a Patriot—Samuel Provoost

Samuel Provoost (March 11, 1742 – September 6, 1815) was an American Clergyman. He was the first Chaplain of the United States Senate and the first Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, as well as the third Presiding Bishop of the Epis ...

, who would become a bishop, in New York and Robert Blackwell, who would serve as a chaplain in the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

, in New Jersey.

Many Church of England clergy remained Loyalists because they took their two ordination

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorization, authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominational ...

oaths very seriously. The first oath arises from the Church of England canons of 1604 where Anglican clergy must affirm that the king,

Thus, all Anglican clergy were obliged to swear publicly allegiance to the king. The second oath arose out of the Act of Uniformity of 1662

The Act of Uniformity 1662 (14 Car 2 c 4) is an Act of the Parliament of England. (It was formerly cited as 13 & 14 Ch.2 c. 4, by reference to the regnal year when it was passed on 19 May 1662.) It prescribed the form of public prayers, adm ...

where clergy were bound to use the official liturgy as found in the ''Book of Common Prayer'' and to read it verbatim. This included prayers for the king and the royal family and for the British Parliament. These two oaths and problems worried the consciences of clergy. Some were clever in their avoidance of these problems. Samuel Tingley, a priest in Delaware and Maryland, rather than praying "O Lord, save the King" opted for evasion and said "O Lord, save those whom thou hast made it our especial Duty to pray for."

In general, Loyalist clergy stayed by their oaths and prayed for the king or else suspended services. By the end of 1776, Anglican churches were closing. An SPG missionary would report that of the colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and Connecticut which he had intelligence of, only the Anglican churches in Philadelphia, a couple in rural Pennsylvania, those in British-controlled New York, and two parishes in Connecticut were open. Anglican priests held services in private homes or lay reader

In Anglicanism, a licensed lay minister (LLM) or lay reader (in some jurisdictions simply reader) is a person authorised by a bishop to lead certain services of worship (or parts of the service), to preach and to carry out pastoral and teaching f ...

s who were not bound by the oaths held Morning

Morning is the period from sunrise to noon. There are no exact times for when morning begins (also true of evening and night) because it can vary according to one's lifestyle and the hours of daylight at each time of year. However, morning strict ...

and Evening Prayer Evening Prayer refers to:

: Evening Prayer (Anglican), an Anglican liturgical service which takes place after midday, generally late afternoon or evening. When significant components of the liturgy are sung, the service is referred to as "Evensong ...

.

Nevertheless, some Loyalist clergy were defiant. In Connecticut, John Beach conducted worship throughout the war and swore that he would continue praying for the king. In Maryland, Jonathan Boucher took two pistols into the pulpit and even pointed a pistol at the head of a group of Patriots while he preached on loyalism. Charles Inglis, rector of Trinity Church in New York, persisted in reading the royal prayers even when George Washington was seated in his congregation and a Patriot militia company stood by observing the service. The consequences of such bravado were very serious. During 1775 and 1776, the Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

had issued decrees ordering churches to fast and pray on behalf of the Patriots. Starting July 4, 1776, Congress and several states passed laws making prayers for the king and British Parliament acts of treason.

The Patriot clergy in the south were quick to find reasons to transfer their oaths to the American cause and prayed for the success of the Revolution. One precedent was the transfer of oaths during the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

in England. Most of the Patriot clergy in the south were able to keep their churches open and services continued.

By the end of the Revolution, the Anglican Church was disestablished in all states where it had previously been a privileged religion. Thomas Buckley examines the debates in the Virginia legislature and local governments that culminated in the repeal of laws granting government property to the Episcopal Church (during the war Anglicans began using the terms "Episcopal" and "Episcopalian" to identify themselves). The Baptists

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only ( believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compe ...

took the lead in disestablishment, with support from Thomas Jefferson and, especially, James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

. Virginia was the only state to seize property belonging to the established Episcopal Church. The fight over the sale of the glebes, or church lands, demonstrated the strength of certain Protestant groups in the political arena when united for a course of action.

Post-Revolution re-organization (1783–1789)

When peace returned in 1783, with the ratification of the new

When peace returned in 1783, with the ratification of the new Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

by the Confederation Congress

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Marc ...

meeting in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, about 80,000 Loyalists (15 percent of the then American population) went into exile. About 50,000 headed for Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, including Charles Inglis, who became the first colonial bishop there. By 1790, in a nation of four million, Anglicans were reduced to about 10 thousand. In Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

, out of 107 parishes before the war only 42 survived. In Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the Caucasus region of Eurasia

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the Southeast United States

Georgia may also refer to:

Places

Historical states and entities

* Related to the ...

, Christ Church, Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

was the only active parish in 1790. In Maryland, half of the parishes remained vacant by 1800. For a period after 1816, North Carolina

North Carolina () is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States. The state is the 28th largest and 9th-most populous of the United States. It is bordered by Virginia to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the east, Georgia and So ...

had no clergy when its last priest died. Samuel Provoost

Samuel Provoost (March 11, 1742 – September 6, 1815) was an American Clergyman. He was the first Chaplain of the United States Senate and the first Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, as well as the third Presiding Bishop of the Epis ...

, Bishop of New York, one of the first three Episcopal bishops, was so disheartened that he resigned his position in 1801 and retired to the country to study botany having given up on the Episcopal Church, which he was convinced would die out with the old colonial families.

Having lost their connection with the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, Anglicans were left without organization and an episcopacy.Roozen 2005, p. 189. They turned to rebuilding and reorganizing, but not everyone was in agreement on how to proceed. In the wake of the Revolution, American Episcopalians faced the task of preserving a hierarchical church structure in a society infused with republican values. Episcopacy continued to be feared after the Revolution and caused division between the low church, anti-bishop South and the high church, pro-bishop New England. Anglicans in Maryland held a convention in 1780 where the name "Protestant Episcopal Church" was first used. Conventions were organized in other states as well. In 1782, William White published an outline for organizing a national church that included both clergy and laity in its governance.Edward L. Bond and Joan R. Gundersen (2007), "The Episcopal Church in Virginia, 1607–2007", ''Virginia Magazine of History & Biography'' 115, no. 2: Chapter 2.

On March 25, 1783, 10 Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

clergy met in Woodbury, Connecticut

Woodbury is a town in Litchfield County, Connecticut, United States. The population was 9,723 at the 2020 census. The town center, comprising the adjacent villages of Woodbury and North Woodbury, is designated by the U.S. Census Bureau as the Woo ...

and elected Samuel Seabury

Samuel Seabury (November 30, 1729February 25, 1796) was the first American Episcopal bishop, the second Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, and the first Bishop of Connecticut. He was a leading Loyalist ...

as their prospective bishop. Seabury sought consecration

Consecration is the solemn dedication to a special purpose or service. The word ''consecration'' literally means "association with the sacred". Persons, places, or things can be consecrated, and the term is used in various ways by different grou ...

in England. The Oath of Supremacy

The Oath of Supremacy required any person taking public or church office in England to swear allegiance to the monarch as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Failure to do so was to be treated as treasonable. The Oath of Supremacy was ori ...

prevented Seabury's consecration in England, so he went to Scotland where the non-juring Scottish bishops consecrated him in Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), and ...

on November 14, 1784. He became, in the words of scholar Arthur Carl Piepkorn, "the first Anglican bishop appointed to minister outside the British Isles". In return, the Scottish bishops requested that the Episcopal Church use the longer Scottish prayer of consecration during the Eucharist

The Eucharist (; from Greek , , ), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord's Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instit ...

, instead of the English prayer. Seabury promised that he would endeavor to make it so. Seabury returned to Connecticut in 1785. At an August 2, 1785, reception at Christ Church on the South Green in Middletown, his letters of consecration were requested, read, and accepted. The next day the first ordinations on American soil took place when Henry Van Dyke, Philo Shelton, Ashbel Baldwin, and Colin Ferguson were ordained deacons. On August 7, 1785, Collin Ferguson was advanced to the priesthood, and Thomas Fitch Oliver was admitted to the diaconate.

That same year, clerical and lay representatives from seven of the nine states south of Connecticut held the first General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. They drafted a constitution, an American ''Book of Common Prayer'', and planned for the consecration of additional bishops. In 1787, two priests— William White of Pennsylvania and

That same year, clerical and lay representatives from seven of the nine states south of Connecticut held the first General Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. They drafted a constitution, an American ''Book of Common Prayer'', and planned for the consecration of additional bishops. In 1787, two priests— William White of Pennsylvania and Samuel Provoost

Samuel Provoost (March 11, 1742 – September 6, 1815) was an American Clergyman. He was the first Chaplain of the United States Senate and the first Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New York, as well as the third Presiding Bishop of the Epis ...

of New York—were consecrated as bishops by the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

, the Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers th ...

, and the Bishop of Bath and Wells

The Bishop of Bath and Wells heads the Church of England Diocese of Bath and Wells in the Province of Canterbury in England.

The present diocese covers the overwhelmingly greater part of the (ceremonial) county of Somerset and a small area of Do ...

, the legal obstacles having been removed by the passage through Parliament of the Consecration of Bishops Abroad Act 1786. Thus, there are two branches of Apostolic succession

Apostolic succession is the method whereby the ministry of the Christian Church is held to be derived from the apostles by a continuous succession, which has usually been associated with a claim that the succession is through a series of bish ...

for American bishops:

#Through the non-juring bishops of Scotland that consecrated Samuel Seabury.

#Through the English church that consecrated William White and Samuel Provoost.

All bishops in the Episcopal Church are ordained by at least three bishops; one can trace the succession of each back to Seabury, White and Provoost (see Succession of Bishops of the Episcopal Church). The fourth bishop of the Episcopal Church was James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, the first Bishop of Virginia

The Diocese of Virginia is the largest diocese of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, encompassing 38 counties in the northern and central parts of the state of Virginia. The diocese was organized in 1785 and is one of the Episco ...

. Madison was consecrated in 1790 under the Archbishop of Canterbury and two other English bishops. This third American bishop consecrated within the English line of succession occurred because of continuing unease within the Church of England over Seabury's nonjuring Scottish orders.

In 1789, representative clergy from nine original dioceses met in Philadelphia to ratify the church's initial constitution. The Episcopal Church was formally separated from the Church of England in 1789 so that American clergy would not be required to accept the supremacy of the British monarch

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Bailiwi ...

. A revised American version of the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 in the reign ...

'' was produced for the new Church in 1789.

Federalist Era (1789–1800)

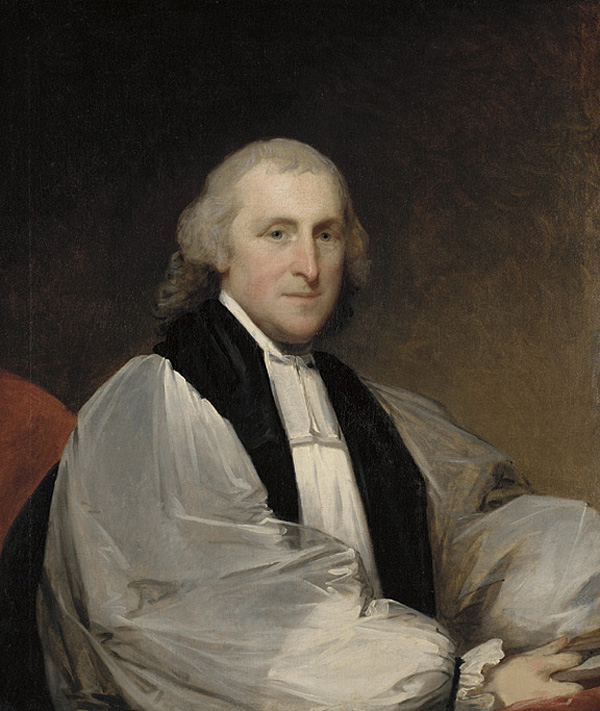

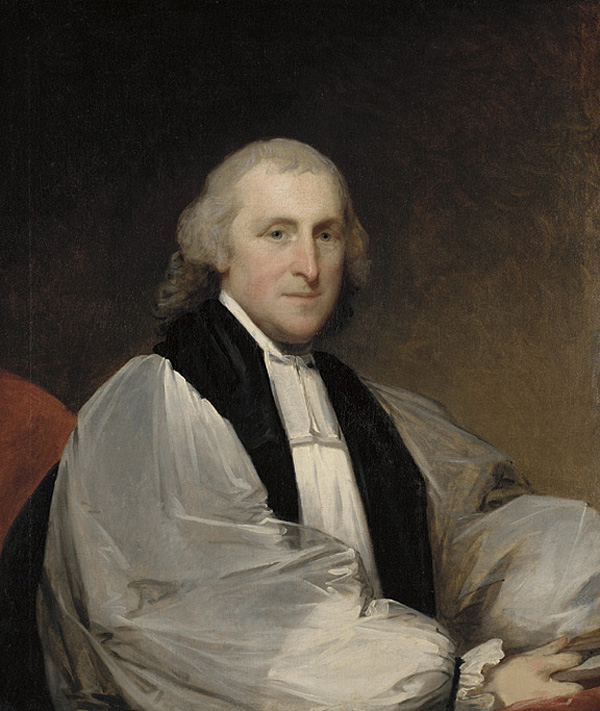

American bishops such as William White (1748–1836) provided a model of civic involvement.Robert Bruce Mullin, "The Office of Bishop among Episcopalians, 1780–1835," ''Lutheran Quarterly,'' Spring 1992, Vol. 6 Issue 1, pp 69-8319th century

Antebellum Church (1800–1861)

American bishops such as William White (1748–1836) continued to provide models of civic involvement, while newly consecrated bishops such as

American bishops such as William White (1748–1836) continued to provide models of civic involvement, while newly consecrated bishops such as John Henry Hobart

John Henry Hobart (September 14, 1775 – September 12, 1830) was the third Episcopal bishop of New York (1816–1830). He vigorously promoted the extension of the Episcopal Church in upstate New York, as well as founded both the General Th ...

(1775–1830), and Philander Chase

Philander Chase (December 14, 1775 – September 20, 1852) was an Episcopal Church bishop, educator, and pioneer of the United States western frontier, especially in Ohio and Illinois.

Early life and family

Born in Cornish, New Hampshire to o ...

(1775–1852) began to provide models of pastoral dedication and evangelism, respectively, as well.

During the first four decades of the church's existence, Episcopalians were more interested in organizing and expanding the church within their own states than in establishing centralized structures or attempting to spread their faith in other places. However, in 1821, the General Convention created a General Seminary for the whole church and established the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of the Protestant Episcopal Church. In 1835, the General Convention declared that all members of the Episcopal Church were to constitute the membership of the Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society and elected the first domestic missionary bishop, Jackson Kemper

Jackson Kemper (December 24, 1789 – May 24, 1870) in 1835 became the first missionary bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America. Especially known for his work with Native American peoples, he also founded parishes in wha ...

, for Missouri and Indiana. The first two foreign missionary bishops, William Boone for China and Horatio Southgate

Horatio Southgate (July 5, 1812 – April 11, 1894) was born in Portland, Maine, and studied for the ordained ministry at Andover Theological Seminary as a Congregationalist. In 1834 he became a member of the Episcopal Church in the United States ...

for Constantinople, were elected in 1844. The church would later establish a presence in Japan and Liberia. On both the domestic and foreign fields, the Episcopal Church's missions could be characterized as "good schools, good hospitals and right ordered worship".Roozen 2005, p. 190.

The first society for African Americans in the Episcopal Church was founded before the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

in 1856 by James Theodore Holly

James Theodore Augustus Holly (3 October 1829 in Washington, D.C. – 13 March 1911 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti) was the first African-American bishop in the Protestant Episcopal church, and spent most of his episcopal career as missionary bishop of ...

. Named ''The Protestant Episcopal Society for Promoting the Extension of the Church Among Colored People'', the society argued that blacks should be allowed to participate in seminaries and diocesan conventions. The group lost its focus when Holly emigrated to Haiti, but other groups followed after the Civil War. The current Union of Black Episcopalians

The Union of Black Episcopalians, formerly the Union of Black Clergy and Laity, is an organization of The Episcopal Church.

History

The union was formed on February 8, 1968, by a group of African-American clergy who met in St. Philip's Episcop ...

traces its history to the society.

Civil War era (1861–1865)

When the

When the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

began in 1861, Episcopalians in the South formed its own Protestant Episcopal Church. However, in the North the separation was never officially recognized. After the war, the Presiding Bishop, John Henry Hopkins

John Henry Hopkins (January 30, 1792 – January 9, 1868) was the first bishop of Episcopal Diocese of Vermont and the eighth Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America. He was also an artist (in both watercolor and ...

, Bishop of Vermont, wrote to every Southern bishop to attend the convocation in Philadelphia in October 1865 to pull the church back together again. Only Thomas Atkinson of North Carolina and Henry C. Lay of Arkansas attended from the South. Atkinson, whose opinions represented his own diocese better than it did his fellow Southern bishops, did much nonetheless to represent the South while at the same time paving the way for reunion. A General Council of the Southern Church meeting in Atlanta in November permitted dioceses to withdraw from the church. All withdrew by 16 May 1866, rejoining the national church.

It was also during the American Civil War that James Theodore Holly emigrated to Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, where he founded the Anglican Church in Haiti, which later became the largest diocese of the Episcopal Church.

Post-Civil War (1865–1900)

Lambeth Conference

The Lambeth Conference is a decennial assembly of bishops of the Anglican Communion convened by the Archbishop of Canterbury. The first such conference took place at Lambeth in 1867.

As the Anglican Communion is an international association ...

. However, he was consecrated by the American Church Missionary Society, an Evangelical Episcopal branch of the Church. In 1875, the Haitian church became a diocese of the Episcopal Church.

Samuel David Ferguson

Samuel David Ferguson (January 1, 1842 – August 2, 1916) was an African American clergyman in Liberia. He was the first African American to be elected as a bishop of the Episcopal Church in Liberia.

Biography

Samuel David Ferguson was born in ...

was the first black bishop consecrated by the Episcopal Church, the first to practice in the U.S. and the first black person to sit in the House of Bishops

The House of Bishops is the third House in a General Synod of some Anglican churches and the second house in the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America.

. Ferguson was consecrated on June 24, 1885, with the then-Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church acting as a consecrator.

By the middle of the 19th century, evangelical Episcopalians disturbed by High Church

The term ''high church'' refers to beliefs and practices of Christian ecclesiology, liturgy, and theology that emphasize formality and resistance to modernisation. Although used in connection with various Christian traditions, the term originate ...

Tractarianism

The Oxford Movement was a movement of high church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the University of O ...

, while continuing to work in interdenominational agencies, formed their own voluntary societies, and eventually, in 1874, a faction objecting to the revival of ritual practices established the Reformed Episcopal Church

The Reformed Episcopal Church (REC) is an Anglican church of evangelical Episcopalian heritage. It was founded in 1873 in New York City by George David Cummins, a former bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church.

The REC is a founding member of ...

.

20th century

In 1919, the church's structure underwent greater centralization. Constitutional changes transformed the presiding bishop into an elected executive officer (formerly, the presiding bishop was simply the most senior bishop and only presided overHouse of Bishops

The House of Bishops is the third House in a General Synod of some Anglican churches and the second house in the General Convention of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America.

meetings) and created a national council to coordinate the church's missionary, educational, and social work.Roozen 2005, pp. 191–192. It was during this period that the ''Book of Common Prayer'' was revised, first in 1892 and later in 1928.

In 1940, the Episcopal Church's coat-of-arms was adopted. This is based on the

In 1940, the Episcopal Church's coat-of-arms was adopted. This is based on the St George's Cross

In heraldry, Saint George's Cross, the Cross of Saint George, is a red cross on a white background, which from the Late Middle Ages became associated with Saint George, the military saint, often depicted as a crusader.

Associated with the cru ...

, a symbol of England (mother of world Anglicanism), with a saltire

A saltire, also called Saint Andrew's Cross or the crux decussata, is a heraldic symbol in the form of a diagonal cross, like the shape of the letter X in Roman type. The word comes from the Middle French ''sautoir'', Medieval Latin ''saltator ...

reminiscent of the Cross of St Andrew in the canton

Canton may refer to:

Administrative division terminology

* Canton (administrative division), territorial/administrative division in some countries, notably Switzerland

* Township (Canada), known as ''canton'' in Canadian French

Arts and ent ...

, in reference to the historical origins of the American episcopate in the Scottish Episcopal Church

The Scottish Episcopal Church ( gd, Eaglais Easbaigeach na h-Alba; sco, Scots Episcopal(ian) Kirk) is the ecclesiastical province of the Anglican Communion in Scotland.

A continuation of the Church of Scotland as intended by King James VI, and ...

.

After the Revolution of 1949

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led government of the Republic of China and forces of the Chinese Communist Party, continuing intermittently since 1 August 1927 until 7 December 1949 with a Communist victory on mainl ...

and the expulsion of missionaries from China, the Episcopal Church focused its efforts in Latin America.

Social issues and sociology

In the early 20th century, the Episcopal Church was shaped by theSocial Gospel

The Social Gospel is a social movement within Protestantism that aims to apply Christian ethics to social problems, especially issues of social justice such as economic inequality, poverty, alcoholism, crime, racial tensions, slums, unclean envir ...

movement and a revived sense of being a "national church" in the Anglican tradition. A mostly female labor force formed the backbone of the church's urban outreach providing health care, education, and economic assistance to the disabled and disadvantaged. These activities made the Episcopal Church a leader in the Social Gospel movement. In its missionary work, the church saw as its responsibility to "spread the riches of American society and the richness of Anglican tradition at home and overseas". Spurred by American imperialism

American imperialism refers to the expansion of American political, economic, cultural, and media influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conquest ...

, the church expanded into Alaska, Cuba, Mexico, Brazil, Haiti, Honolulu, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and the Panama Canal Zone.

Highly prominent laity such as banker J. P. Morgan

John Pierpont Morgan Sr. (April 17, 1837 – March 31, 1913) was an American financier and investment banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the Gilded Age. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known ...

, industrialist Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that mi ...

, and art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner

Isabella Stewart Gardner (April 14, 1840 – July 17, 1924) was a leading American art collector, philanthropist, and patron of the arts. She founded the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston.

Gardner possessed an energetic intellectual cur ...

played a central role in shaping a distinctive upper-class Episcopalian ethos, especially with regard to preserving the arts and history. Moreover, despite the relationship between Anglo-Catholicism

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholic heritage and identity of the various Anglican churches.

The term was coined in the early 19th century, although movements emphasising the Catholic nature of Anglica ...

and Episcopalian involvement in the arts, most of these laypeople were not inordinately influenced by religious thought. These philanthropists propelled the Episcopal Church into a quasi-national position of importance while at the same time giving the church a central role in the cultural transformation of the country. Another mark of influence is the fact that more than a quarter of all presidents of the United States

The president of the United States is the head of state and head of government of the United States, indirectly elected to a four-year term via the Electoral College. The officeholder leads the executive branch of the federal government and ...

have been Episcopalians (''see List of United States Presidential religious affiliations'').

Modernization

The modernization of the church has included both controversial and non-controversial moves related to racism, theology, worship, homosexuality, the ordination of women, the institution of marriage, and the adoption of a new prayer book, which can be dated to the General Convention of 1976. The first women were admitted as delegates to General Convention in 1970. In 1975, Vaughan Booker, who confessed to the murder of his wife and was sentenced to life in prison, was ordained to the diaconate in Graterford State Prison's chapel inPennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

, after having repented of his sins, becoming a symbol of redemption and atonement.

Regarding racism the 1976 General Convention passed a resolution calling for an end to apartheid

Apartheid (, especially South African English: , ; , "aparthood") was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was ...

in South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

and in 1985 called for "dioceses, institutions, and agencies" to create equal employment opportunity

Equal employment opportunity is equal opportunity to attain or maintain employment in a company, organization, or other institution. Examples of legislation to foster it or to protect it from eroding include the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity ...

and affirmative action policies to address any potential "racial inequities" in clergy placement. In 1991 the General Convention declared "the practice of racism is sin" and in 2006 a unanimous House of Bishops endorsed Resolution A123 apologizing for complicity in the institution of slavery and silence over "Jim Crow" laws, segregation, and racial discrimination.

Liturgical reform

The 1976 General Convention also approved a new prayer book, which was a substantial revision and modernization of the previous 1928 edition. It incorporated many principles of the Roman Catholic Church'sliturgical movement

The Liturgical Movement was a 19th-century and 20th-century movement of scholarship for the reform of worship. It began in the Catholic Church and spread to many other Christian churches including the Anglican Communion, Lutheran and some other Pro ...

, which had been discussed at Vatican II

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions), each lasting between 8 and 1 ...

. This version was adopted as the official prayer book in 1979 after an initial three-year trial use. A number of conservative parishes, however, continued to use the 1928 version.

Women's ordination

Initially, the priesthood in the Episcopal Church was restricted to men only, as was true of most other Christian denominations prior to the mid-20th century and still true for some. Objections to the ordination of women have been different from time to time and place to place. Some believe that it is fundamentally impossible for a woman to be validly ordained, while others believe it is possible but inappropriate. Considerations cited include local social conditions, ecumenical implications, or the symbolic character of the priesthood, an ancient tradition including an all-male priesthood, as well as certain biblical texts. Following upon years of discussion in the Episcopal Church and elsewhere, in 1976, the General Convention amended canon law to permit theordination of women

The ordination of women to ministerial or priestly office is an increasingly common practice among some contemporary major religious groups. It remains a controversial issue in certain Christian traditions and most denominations in which "ordina ...

to the priesthood. The first women were canonically ordained to the priesthood in 1977. (Previously, the "Philadelphia Eleven

The Philadelphia Eleven are eleven women who were the first women ordained as priests in the Episcopal Church on July 29, 1974, two years before General Convention affirmed and explicitly authorized the ordination of women to the priesthood.

Ba ...

" were uncanonically ordained on July 29, 1974, in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

. Another four "irregular" ordinations (the "Washington Four

The Philadelphia Eleven are eleven women who were the first women ordained as priests in the Episcopal Church (United States), Episcopal Church on July 29, 1974, two years before General Convention of the Episcopal Church in the United States of A ...

") also occurred in 1975 in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

These "irregular" ordinations were also reconciled at the 1976 GC.) Many other churches in the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

, including the Church of England, now ordain women as deacons or priests, but only a few have women serving as bishops.

The first woman to become a bishop, Barbara Harris, was consecrated on February 11, 1989. The General Convention reaffirmed in 1994 that both men and women may enter into the ordination process, but also recognized that there is value to the theological position of those who oppose women's ordination. It was not until 1997 that the GC declared that "the ordination, licensing and deployment of women are mandatory" and that dioceses that have not ordained women by 1997 "shall give status reports on their implementation".The Archives of the Episcopal Church,Acts of Convention: Resolution #1997-A053, Implement Mandatory Rights of Women Clergy under Canon Law

Retrieved 2008-10-31.

Homosexuality

The Episcopal Church affirmed at the 1976 General Convention thathomosexuals

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

are "children of God" who deserve acceptance and pastoral care from the church. It also called for homosexual persons to have equal protection under the law. This was reaffirmed in 1982. Despite these affirmations of gay rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , 3 ...

, the General Convention affirmed in 1991 that "physical sexual expression" is only appropriate within the monogamous

Monogamy ( ) is a form of Dyad (sociology), dyadic Intimate relationship, relationship in which an individual has only one Significant other, partner during their lifetime. Alternately, only one partner at any one time (Monogamy#Serial monogamy, ...

, lifelong "union of husband and wife".The Archives of the Episcopal ChurchActs of Convention: Resolution #1991-A104, Affirm the Church's Teaching on Sexual Expression, Commission Congregational Dialogue, and Direct Bishops to Prepare a Pastoral Teaching

Retrieved 2008-10-31. In 1994, the GC determined that church membership would not be determined on "marital status, sex, or sexual orientation". The first openly gay priest, Robert Williams, was ordained by

John Shelby Spong

John Shelby "Jack" Spong (June 16, 1931 – September 12, 2021) was an American bishop of the Episcopal Church. From 1979 to 2000, he was the Bishop of Newark, New Jersey. A liberal Christian theologian, religion commentator, and author, he call ...

in 1989. The ordination provoked a furor. The next year Barry Stopfel was ordained a deacon by Spong's assistant, Walter Righter. Because Stopfel was not celibate, this resulted in a trial under canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

. The church court dismissed the charges on May 15, 1996, stating that "no clear doctrine" prohibits ordaining a gay or lesbian person in a committed relationship.

21st century Anglican issues

Gay and lesbian access to marriage and the episcopate

The first openly homosexual bishop,

The first openly homosexual bishop, Gene Robinson

Vicky Gene Robinson (born May 29, 1947) is a former bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire. Robinson was elected bishop coadjutor in 2003 and succeeded as bishop diocesan in March 2004. Before becoming bishop, he served as Canon to th ...

, was elected on June 7, 2003, at St. Paul's Church in Concord, New Hampshire

Concord () is the capital city of the U.S. state of New Hampshire and the seat of Merrimack County. As of the 2020 census the population was 43,976, making it the third largest city in New Hampshire behind Manchester and Nashua.

The village of ...

. Thirty-nine clergy votes and 83 lay votes was the threshold necessary to elect a bishop in the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire

The Episcopal Church of New Hampshire, a diocese of the Episcopal Church in the United States of America (ECUSA), covers the entire state of New Hampshire. It was originally part of the Diocese of Massachusetts, but became independent in 1841. ...

at that time. The clergy voted 58 votes for Robinson and the laity voted 96 for Robinson on the second ballot. Consent to the election of Robinson was given at the 2003 General Convention. The House of Bishops voted in the affirmative, with 62 in favor, 43 opposed, and 2 abstaining. The House of Deputies, which consists of laypersons and priests, also voted in the affirmative: the laity voted 63 in favor, 32 opposed, and 13 divided; the clergy voted 65 in favor, 31 opposed, and 12 divided.

In response, a meeting of the Anglican primates (the heads of the Anglican Communion's 38 member churches) was convened in October 2003, which warned that if Robinson's consecration proceeded, it could "tear the fabric of the communion at its deepest level." The primates also appointed a commission to study these issues, which issued the Windsor Report

In 2003, the Lambeth Commission on Communion was appointed by the Anglican Communion to study problems stemming from the consecration of Gene Robinson, the first noncelibate self-identifying gay priest to be ordained as an Anglican bishop, in the E ...

the following year. At the request of the commission issuing the Windsor Report, the Episcopal Church released ''To Set Our Hope on Christ'' on June 21, 2005, which explains "how a person living in a same gender union may be considered eligible to lead the flock of Christ."

Robinson was consecrated on November 2, 2003, in the presence of Frank Griswold, the Presiding Bishop, and 47 bishops.

The General Convention of 2003 also passed a resolution discouraging the use of conversion therapy

Conversion therapy is the pseudoscientific practice of attempting to change an individual's sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender expression to align with heterosexual and cisgender norms. In contrast to evidence-based medicine and cli ...

to attempt to change homosexuals

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or sexual behavior between members of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to pe ...

into heterosexuals

Heterosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction or sexual behavior between people of the opposite sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, heterosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexual attractions" to ...

.

In 2009, the General Convention responded to societal, political and legal changes in the status of civil marriage for same-sex couples by giving bishops an option to provide "generous pastoral support" especially where civil authorities have legalized same-gender marriage, civil unions, or domestic partnerships. It also charged the Standing Commission on Liturgy and Music to develop theological and liturgical resources for same-sex blessings and report back to the General Convention in 2012.76th General Convention LegislationResolution C056

. Retrieved August 18, 2010. The same General Convention also voted that "any ordained ministry" is open to gay men and lesbians.Laurie Goodstei

''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

, July 14, 2009''. Retrieved on July 21, 2009. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' said the move was "likely to send shockwaves through the Anglican Communion." This vote ended a moratorium on ordaining gay bishops passed in 2006 and passed in spite of Archbishop Rowan Williams

Rowan Douglas Williams, Baron Williams of Oystermouth, (born 14 June 1950) is a Welsh Anglican bishop, theologian and poet. He was the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury, a position he held from December 2002 to December 2012. Previously the Bish ...

's personal call at the start of the convention that, "I hope and pray that there won't be decisions in the coming days that will push us further apart." A noted Evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide Interdenominationalism, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being "bor ...

scholar of the New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

, N. T. Wright, who is also Bishop of Durham

The Bishop of Durham is the Anglican bishop responsible for the Diocese of Durham in the Province of York. The diocese is one of the oldest in England and its bishop is a member of the House of Lords. Paul Butler has been the Bishop of Durham ...

in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

, wrote in ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

'' (London) that the vote "marks a clear break with the rest of the Anglican Communion" and formalizes the Anglican schism. However, in another resolution the Convention voted to "reaffirm the continued participation" and "reaffirm the abiding commitment" of the Episcopal Church with Anglican Communion.

A woman as Presiding Bishop

The 2006 election of The Rev. Katharine Jefferts Schori as the Church's 26th presiding bishop was controversial in the wider Anglican Communion because she is a woman and the full Anglican communion does not recognize the ordination of women. She is the only national leader of a church in the Anglican Communion who is a woman. Prior to her election she was Bishop of Nevada. She was elected at the 75th General Convention on June 18, 2006, and invested at theWashington National Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul in the City and Diocese of Washington, commonly known as Washington National Cathedral, is an American cathedral of the Episcopal Church. The cathedral is located in Washington, D.C., the cap ...

on November 4, 2006.

Jefferts Schori generated controversy when she voted to confirm openly gay Gene Robinson as a bishop and for allowing blessings of same-sex unions in her diocese of Nevada.

During her time as Presiding Bishop, ten primates

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

of the Anglican communion stated that they did not recognize Jefferts Schori as a primate. In addition, eight American dioceses rejected her authority and asked Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

Rowan Williams

Rowan Douglas Williams, Baron Williams of Oystermouth, (born 14 June 1950) is a Welsh Anglican bishop, theologian and poet. He was the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury, a position he held from December 2002 to December 2012. Previously the Bish ...

to assign them another national leader.

Conservative reactions to these developments

These innovations have been responded to in various ways. The opposition to Ritualism produced theReformed Episcopal Church

The Reformed Episcopal Church (REC) is an Anglican church of evangelical Episcopalian heritage. It was founded in 1873 in New York City by George David Cummins, a former bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church.

The REC is a founding member of ...

in 1873. Opposition to the ordination of women priests and to theological revisions incorporated into the Episcopal Church's 1979 Book of Common Prayer led to the formation of the Continuing Anglican movement

The Continuing Anglican Movement, also known as the Anglican Continuum, encompasses a number of Christian churches, principally based in North America, that have an Anglican identity and tradition but are not part of the Anglican Communion.

The ...

in 1977; and opposition to the consecration of the first ever openly homosexual bishop led to the creation of the Anglican Church in North America

The Anglican Church in North America (ACNA) is a Christian denomination in the Anglican tradition in the United States and Canada. It also includes ten congregations in Mexico, two mission churches in Guatemala, and a missionary diocese in Cuba ...

. It officially organized in 2009, forming yet another ecclesiastical structure apart from the Episcopal Church. This grouping, which reported at its founding that it represented approximately 100,000 Christians through its over 700 parishes, elected former Episcopal priest Robert Duncan as its primate. The ACNA has not been received as an official member of the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is the third largest Christian communion after the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches. Founded in 1867 in London, the communion has more than 85 million members within the Church of England and other ...

by the Church of England, and is not in communion with the see of Canterbury, but many Anglican churches of the Global South

The concept of Global North and Global South (or North–South divide in a global context) is used to describe a grouping of countries along socio-economic and political characteristics. The Global South is a term often used to identify region ...

, such as the Church of Nigeria