The history of the Assyrians encompasses nearly five millennia, covering the history of the ancient

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n civilization of

Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the ...

, including its territory, culture and people, as well as the later history of the

Assyrian people after the fall of the

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

in 609 BC. For purposes of

historiography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians ha ...

, ancient Assyrian history is often divided by modern researchers, based on political events and gradual changes in language, into the

Early Assyrian ( 2600–2025 BC),

Old Assyrian ( 2025–1364 BC),

Middle Assyrian ( 1363–912 BC),

Neo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

(911–609 BC) and

post-imperial (609 BC– AD 240) periods.

Assyria gets its name from the ancient city of

Assur

Aššur (; Sumerian: AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; syr, ܐܫܘܪ ''Āšūr''; Old Persian ''Aθur'', fa, آشور: ''Āšūr''; he, אַשּׁוּר, ', ar, اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal ...

, founded 2600 BC. During much of its early history, Assur was dominated by foreign states and polities from southern Mesopotamia, for instance falling under the

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

of the Sumerian city of

Kish

Kish may refer to:

Geography

* Gishi, Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan, a village also called Kish

* Kiş, Shaki, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality also spelled Kish

* Kish Island, an Iranian island and a city in the Persian Gulf

* Kish, Iran, ...

, being conquered by the

Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one ...

and falling under the rule of the

Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

. The city became an independent city-state under its own line of rulers during the collapse of the Third Dynasty of Ur, achieving independence under

Puzur-Ashur I

Puzur-Ashur I ( akk, , Pu-AMAR-Aš-ŠUR) was an Assyrian king in the 21st and 20th centuries BC. He is generally regarded as the founder of Assyria as an independent city-state, 2025 BC.

He is in the Assyrian King List and is referenced in the ...

2025 BC.

Puzur-Ashur's dynasty continued to govern Assur until the city was captured by the

Amorite

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied la ...

conqueror

Shamshi-Adad I

Shamshi-Adad ( akk, Šamši-Adad; Amorite: ''Shamshi-Addu''), ruled 1808–1776 BC, was an Amorite warlord and conqueror who had conquered lands across much of Syria, Anatolia, and Upper Mesopotamia.Some of the Mari letters addressed to Shamsi-Ad ...

1808 BC. After a few decades of foreign dominion and rule, Assur was restored as an independent city-state, perhaps by the king

Puzur-Sin Puzur-Sin was an Assyrian king in the 18th century BC, during the Old Assyrian period. One of the few known Assyrian rulers to be left out of the ''Assyrian King List'', Puzur-Sin was responsible for ending the rule of the dynasty of Shamshi-Adad I ...

. In the 15th century BC, Assur fell under the suzerainty of the

Mitanni

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or ''Naharin'' in ...

kingdom. After wars between Mitanni and the

Hittites

The Hittites () were an Anatolian people who played an important role in establishing first a kingdom in Kussara (before 1750 BC), then the Kanesh or Nesha kingdom (c. 1750–1650 BC), and next an empire centered on Hattusa in north-centra ...

, Assur broke free under

Ashur-uballit I ( 1363–1328 BC) and transitioned from a city-state to a territorial state governing an increasingly large stretch of land, transforming into the Middle Assyrian Empire.

Under the 13th-century BC warrior-kings

Adad-nirari I,

Shalmaneser I

Shalmaneser I (𒁹𒀭𒁲𒈠𒉡𒊕 md''sál-ma-nu-SAG'' ''Salmanu-ašared''; 1273–1244 BC or 1265–1235 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. Son of Adad-nirari I, he succeeded his father as king in 1265 BC.

Accord ...

and

Tukulti-Ninurta I

Tukulti-Ninurta I (meaning: "my trust is in he warrior godNinurta"; reigned 1243–1207 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. He is known as the first king to use the title "King of Kings".

Biography

Tukulti-Ninurta I su ...

, the Middle Assyrian Empire became one of the great powers of the

ancient Near East

The ancient Near East was the home of early civilizations within a region roughly corresponding to the modern Middle East: Mesopotamia (modern Iraq, southeast Turkey, southwest Iran and northeastern Syria), ancient Egypt, ancient Iran ( Elam, ...

, for a time even occupying

Babylonia in the south. After Tukulti-Ninurta's death, Assyria experienced a long period of decline, sometimes interrupted by energetic warrior-kings, which restricted Assyria to little more than the

Assyrian heartland

The Assyrian homeland, Assyria ( syc, ܐܬܘܪ, Āṯūr or syc, ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, Bêth Nahrin) refers to the homeland of the Assyrian people within which Assyrian civilisation developed, located in their indigenous Upper Mesopotamia. Th ...

. New efforts by the Assyrian kings of the 10th and 9th centuries BC reversed this decline. Under

Ashurnasirpal II in the 9th century BC, Assyria (now the Neo-Assyrian Empire) once more became the dominant political power of the Near East. Assyrian expansionism and power reached its peak under

Tiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, T ...

in the 8th century BC and the subsequent

Sargonid dynasty of kings, under whom the Neo-Assyrian Empire stretched from Egypt in the west to Iran in the east. Babylonia was recaptured and Assyrian campaigns were conducted into both

Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

and modern-day Armenia. The empire, and Assyria as a state, came to an end in the late 7th century BC as a result of the

Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire

The Medo-Babylonian conquest of the Assyrian Empire was the last war fought by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, between 626 and 609 BC. Succeeding his brother Ashur-etil-ilani (631–627 BC), the new king of Assyria, Sinsharishkun (627–612 BC), immedi ...

.

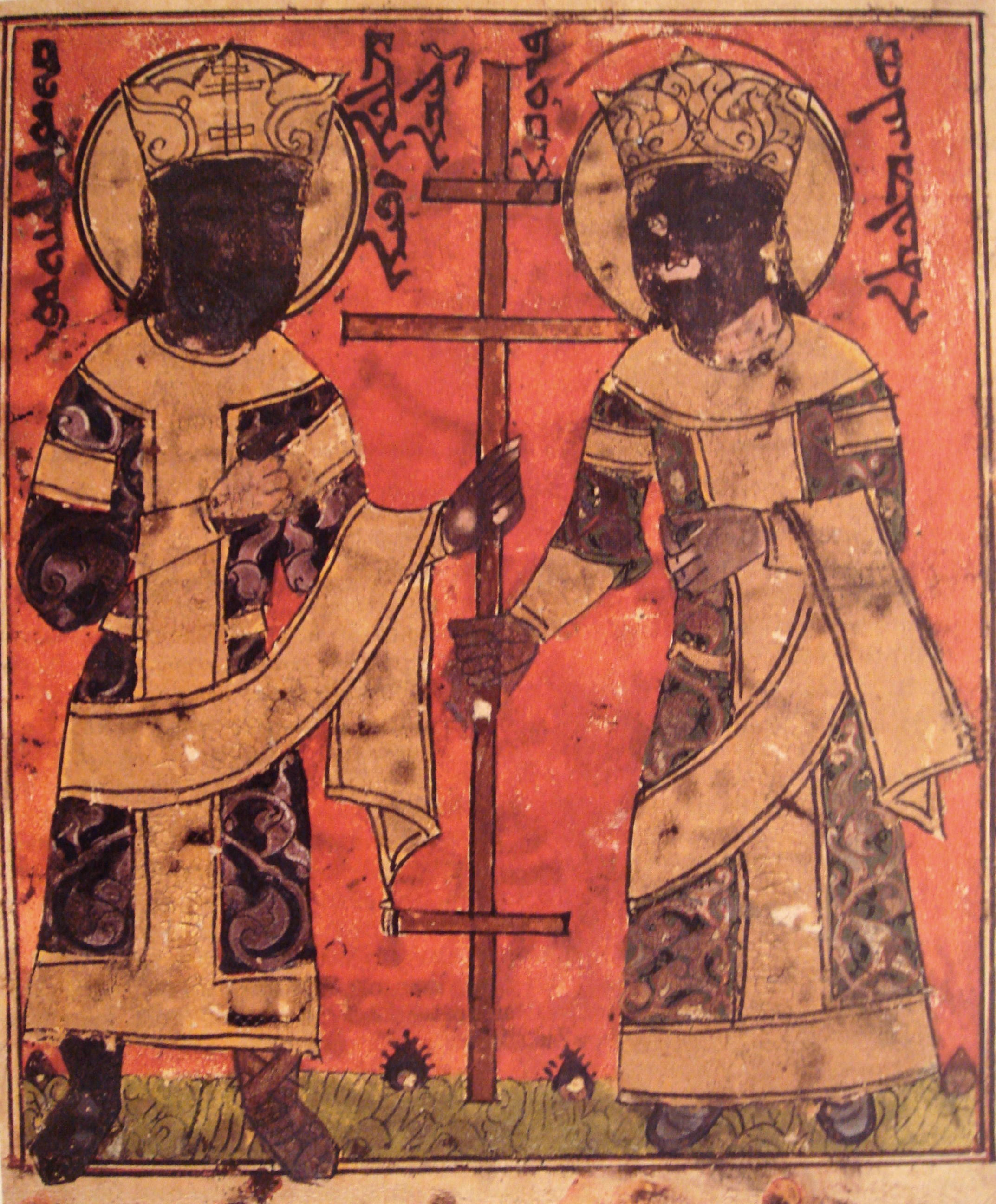

After the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the Assyrian people continued to survive northern Mesopotamia and Assyrian cultural traditions were kept alive. Though the Babylonians and Medes had extensively devastated Assyria, the region was significantly rebuilt and resettled under the rule of the

Seleucid

The Seleucid Empire (; grc, Βασιλεία τῶν Σελευκιδῶν, ''Basileía tōn Seleukidōn'') was a Greek state in West Asia that existed during the Hellenistic period from 312 BC to 63 BC. The Seleucid Empire was founded by the ...

and

Parthian empires, from the 4th century BC to the 3rd century AD. Assur itself flourished in the late post-imperial period, perhaps once more under its own line of rulers as a semi-autonomous city-state, though the city was sacked and destroyed for the last time by the

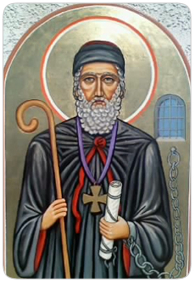

Sasanian Empire AD 240. Starting from the 1st century AD onwards, the Assyrians were

Christianized

Christianization ( or Christianisation) is to make Christian; to imbue with Christian principles; to become Christian. It can apply to the conversion of an individual, a practice, a place or a whole society. It began in the Roman Empire, conti ...

, though holdouts of the old

ancient Mesopotamian religion

Mesopotamian religion refers to the religious beliefs and practices of the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, particularly Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia between circa 6000 BC and 400 AD, after which they largely gave way to Syria ...

continued to survive for centuries. The Assyrians continued to constitute a significant portion of the population in northern Mesopotamia until suppression and massacres under the

Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate, also spelled Il-khanate ( fa, ایل خانان, ''Ilxānān''), known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (, ''Qulug-un Ulus''), was a khanate established from the southwestern sector of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanid realm ...

and the

Timurid Empire

The Timurid Empire ( chg, , fa, ), self-designated as Gurkani (Chagatai language, Chagatai: کورگن, ''Küregen''; fa, , ''Gūrkāniyān''), was a PersianateB.F. Manz, ''"Tīmūr Lang"'', in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006 Tu ...

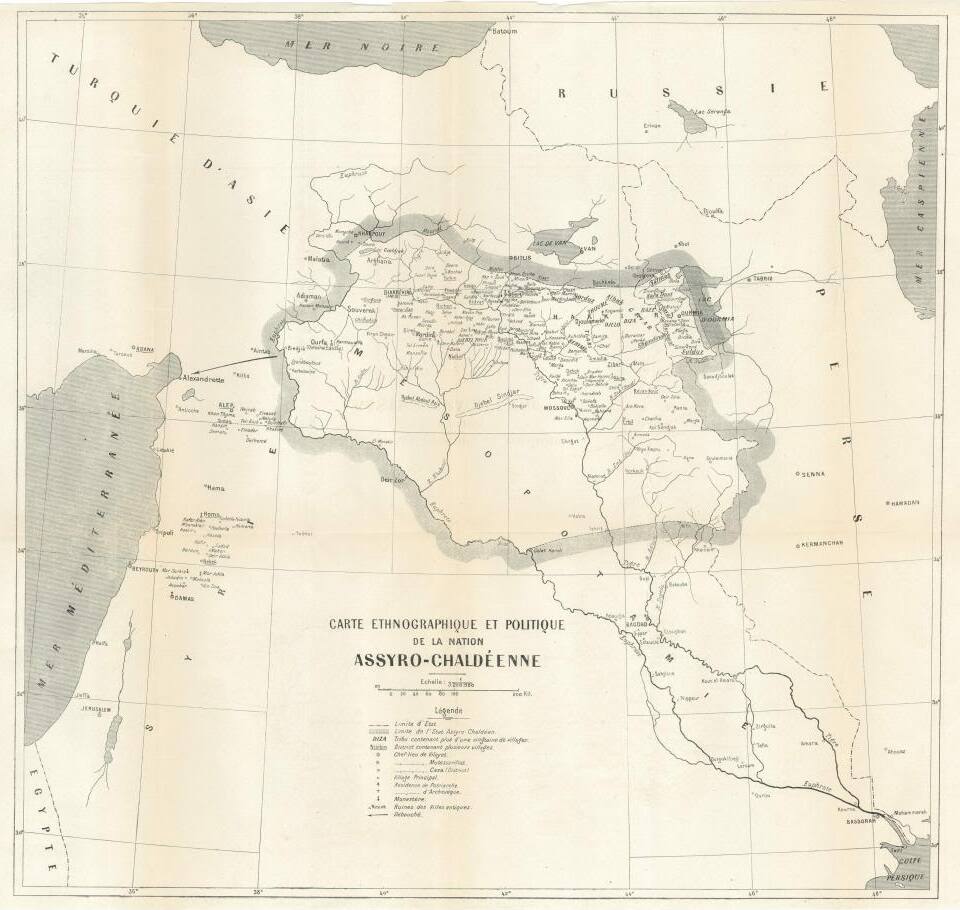

in the 14th century. These atrocities relegated the Assyrians to a local ethnic and religious minority. The late 19th century and early 20th century were marked by further persecution and massacres, most notably the ''

Sayfo

The Sayfo or the Seyfo (; see below), also known as the Assyrian genocide, was the mass slaughter and deportation of Assyrian / Syriac Christians in southeastern Anatolia and Persia's Azerbaijan province by Ottoman forces and some Kurdish t ...

'' (Assyrian genocide) of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

in the 1910s, which resulted in the deaths of as many as 250,000 Assyrians. This time of atrocities was also marked by an increasing Assyrian cultural consciousness; the first Assyrian newspaper, ''

Zahrirē d-Bahra'' ("Rays of Light"), began publishing in 1848 and the earliest Assyrian political party, the

Assyrian Socialist Party, was founded in 1917. Throughout the 20th century and still today, many unsuccessful

proposals have been made by the Assyrians for autonomy or independence. Further massacres and persecutions, enacted both by governments and by terrorist groups such as the

Islamic State

An Islamic state is a state that has a form of government based on Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a translation of the Arabic term ...

have resulted in most of the Assyrian people living in

diaspora.

Ancient Assyria (2600 BC–AD 240)

Early Assyrian period (2600–2025 BC)

Agricultural villages in the region that would later become

Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the ...

are known to have existed by the time of the

Hassuna culture

The Hassuna culture is a Neolithic archaeological culture in northern Mesopotamia dating to the early sixth millennium BC. It is named after the type site of Tell Hassuna in Iraq. Other sites where Hassuna material has been found include Tell ...

, 6300–5800 BC. Though the sites of some nearby cities that would later be incorporated into the Assyrian heartland, such as

Nineveh, are known to have been inhabited since the

Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several p ...

, the earliest archaeological evidence from

Assur

Aššur (; Sumerian: AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''Aš-šurKI'', "City of God Aššur"; syr, ܐܫܘܪ ''Āšūr''; Old Persian ''Aθur'', fa, آشور: ''Āšūr''; he, אַשּׁוּר, ', ar, اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal ...

dates to the

Early Dynastic Period, 2600 BC, a time in which the surrounding region was already relatively urbanized. It is possible that the city was founded earlier; much of the early historical remains of Assur may have been destroyed during the extensive construction projects of later

Assyrian kings

The king of Assyria (Akkadian: ''Išši'ak Aššur'', later ''šar māt Aššur'') was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian kingdom of Assyria, which was founded in the late 21st century BC and fell in the late 7th century BC. For much of its ear ...

, who worked to create level foundations for the buildings they erected in the city. There is no evidence that early Assur was an independent settlement, and it might not have been called Assur at all initially, but rather Baltil or Baltila, used in later times to refer to the city's oldest portion. The name "Assur" is first attested for the site in documents of the

Akkadian period in the 24th century BC.

Early Assur was probably a local religious and tribal center and must have been a town of some size since it had monumental temples. It was located in a highly strategic location, on a hill overlooking the

Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

river, protected by a river on one side and a canal on another. Surviving archaeological and literary evidence suggests that Assur in its earliest history was inhabited by

Hurrians and was the site of a

fertility cult devoted to the goddess

Ishtar

Inanna, also sux, 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒀭𒈾, nin-an-na, label=none is an ancient Mesopotamian goddess of love, war, and fertility. She is also associated with beauty, sex, divine justice, and political power. She was originally worshiped in Su ...

. The earliest known archaeological finds at the site are Early Dynastic-age temples dedicated to Ishtar. These temples and the artifacts within them also show considerable similarities to temples and artifacts from

Sumer in southern Mesopotamia, which might suggest that there was also a group of Sumerians living in the city or that it at some point was conquered by an unknown Sumerian ruler. The

Semitic-speaking ancestors of the later Assyrians settled the city and the surrounding region at some point prior to the 23rd century BC, either assimilating or displacing the previous population.

During much of the early Assyrian period, Assur was dominated by states and polities from southern Mesopotamia. Early on, Assur for a time fell under the loose

hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one State (polity), state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over oth ...

of the Sumerian city of

Kish

Kish may refer to:

Geography

* Gishi, Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan, a village also called Kish

* Kiş, Shaki, Azerbaijan, a village and municipality also spelled Kish

* Kish Island, an Iranian island and a city in the Persian Gulf

* Kish, Iran, ...

and it was later occupied by both the

Akkadian Empire

The Akkadian Empire () was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia after the long-lived civilization of Sumer. It was centered in the city of Akkad () and its surrounding region. The empire united Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one ...

and then the

Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

. The Akkadian Empire probably conquered Assur in the time of its first ruler,

Sargon ( 2334–2279 BC), and is known to have controlled the city at least from the reign of

Manishtushu

Manishtushu (, ''Ma-an-ish-tu-su'') was the third king of the Akkadian Empire, reigning from c. 2270 BC until his assassination in 2255 BC (Middle Chronology). He was the son of Sargon the Great, the founder of the Akkadian Empire, and he was su ...

( 2270–2255 BC) onwards since contemporary inscriptions dedicated to Manishtushu have been recovered from the city. The earliest historically attested rulers of Assur were local governors under the Akkadian kings, including figures such as

Ititi and

Azazu, who bore the title ''Išši'ak Aššur'' (governor of Assur). Assur was strongly influenced both culturally and linguistically by the period under Akkadian rule and the period would be regarded as a golden age by later Assyrian kings, who often sought to emulate the Akkadian rulers.

Assur was destroyed in the late Akkadian period, possibly by the

Lullubi

Lullubi, Lulubi ( akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈: ''Lu-lu-bi'', akk, 𒇻𒇻𒉈𒆠: ''Lu-lu-biki'' "Country of the Lullubi"), more commonly known as Lullu, were a group of tribes during the 3rd millennium BC, from a region known as ''Lulubum'', now the Sha ...

, but was rebuilt and later conquered by the Sumerian

Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

in the late 20th or early 19th century BC. Under the rulers of Ur, Assur became a peripheral city under its own governors, such as

Zariqum

Zariqum or Zarriqum was a Sumerian governor (''šakkanakkum'') of the city of Assur under the Third Dynasty of Ur, attested there between the 44th year of Shulgi () and the 5th year of Amar-Sin ().

He is the only governor of the city during this ...

, who paid tribute to the southern kings. This period of Sumerian dominance over the city came to an end as the last king of the Third Dynasty of Ur,

Ibbi-Sin

Ibbi-Sin ( sux, , ), son of Shu-Sin, was king of Sumer and Akkad and last king of the Ur III dynasty, and reigned c. 2028–2004 BCE ( Middle chronology) or possibly c. 1964–1940 BCE (Short chronology). During his rei ...

( 2028–2004 BC) lost his administrative grip on the peripheral regions of his empire and Assur became an independent

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world since the dawn of history, including cities such as ...

under its own rulers, beginning with

Puzur-Ashur I

Puzur-Ashur I ( akk, , Pu-AMAR-Aš-ŠUR) was an Assyrian king in the 21st and 20th centuries BC. He is generally regarded as the founder of Assyria as an independent city-state, 2025 BC.

He is in the Assyrian King List and is referenced in the ...

2025 BC.

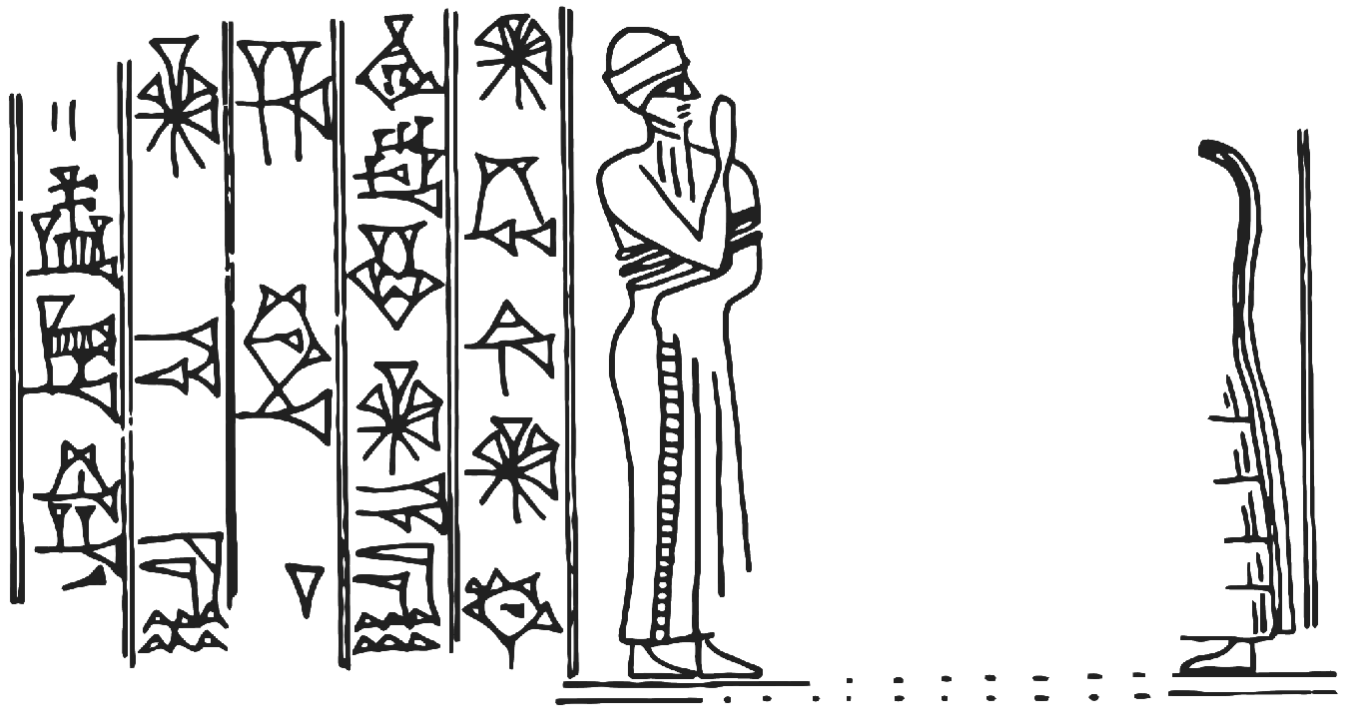

Old Assyrian period (2025–1364 BC)

Puzur-Ashur I and the succeeding kings of his dynasty, the

Puzur-Ashur dynasty, did not technically claim the dignity of "king" (''šar'') for themselves, but continued to use the style rulers of Assur had used while the city was under foreign rule, ''Išši'ak'' ("governor"). The use of this style asserted that the actual king of the city was the Assyrian national deity

Ashur and that the Assyrian ruler was merely his representative on Earth. It is probable that Ashur took form as a deity at some point during the Early Assyrian period as a personification of the city of Assur itself. During the rule of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty, Assur was home to less than 10,000 people and the military power of the city is likely to have been extremely limited; no sources describe any military institutions whatsoever and no surrounding cities were subjected to the rule of the Assyrian kings. The earliest known surviving inscription by an Assyrian king was written by Puzur-Ashur I's son and successor

Shalim-ahum, and records the king having built a temple dedicated to Ashur "for his own life and the life of his city". The fourth king of the dynasty,

Erishum I

Erishum I or Erišu(m) I (inscribed m''e-ri-šu'', or mAPIN''-ìš'' in later texts but always with an initial ''i'' in his own seal, inscriptions, and those of his immediate successors, “he has desired,”) 1974–1935 BC (middle chronology),So ...

( 1974–1934 BC), is the earliest king whose length of reign is recorded in the ''

Assyrian King List

The king of Assyria (Akkadian: ''Išši'ak Aššur'', later ''šar māt Aššur'') was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian kingdom of Assyria, which was founded in the late 21st century BC and fell in the late 7th century BC. For much of its ear ...

'', a later document recording the kings of Assyria and their reigns. Erishum is noteworthy for being the earliest known ruler in world history to experiment with

free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. It can also be understood as the free market idea applied to international trade. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold econ ...

, leaving the initiative for trade and large-scale foreign transactions entirely to his populace. Though large institutions, such as the temples and the king himself, did take part in trade, the financing itself was provided by private bankers, who in turn bore nearly all the risk (but also earned nearly all the profits) of the trading ventures. The king earned a portion of the profit through imposing tolls and the money gained was used to expand Assur and its institutions. Through Erishum's efforts, Assur quickly established itself as a prominent trading city in northern Mesopotamia.

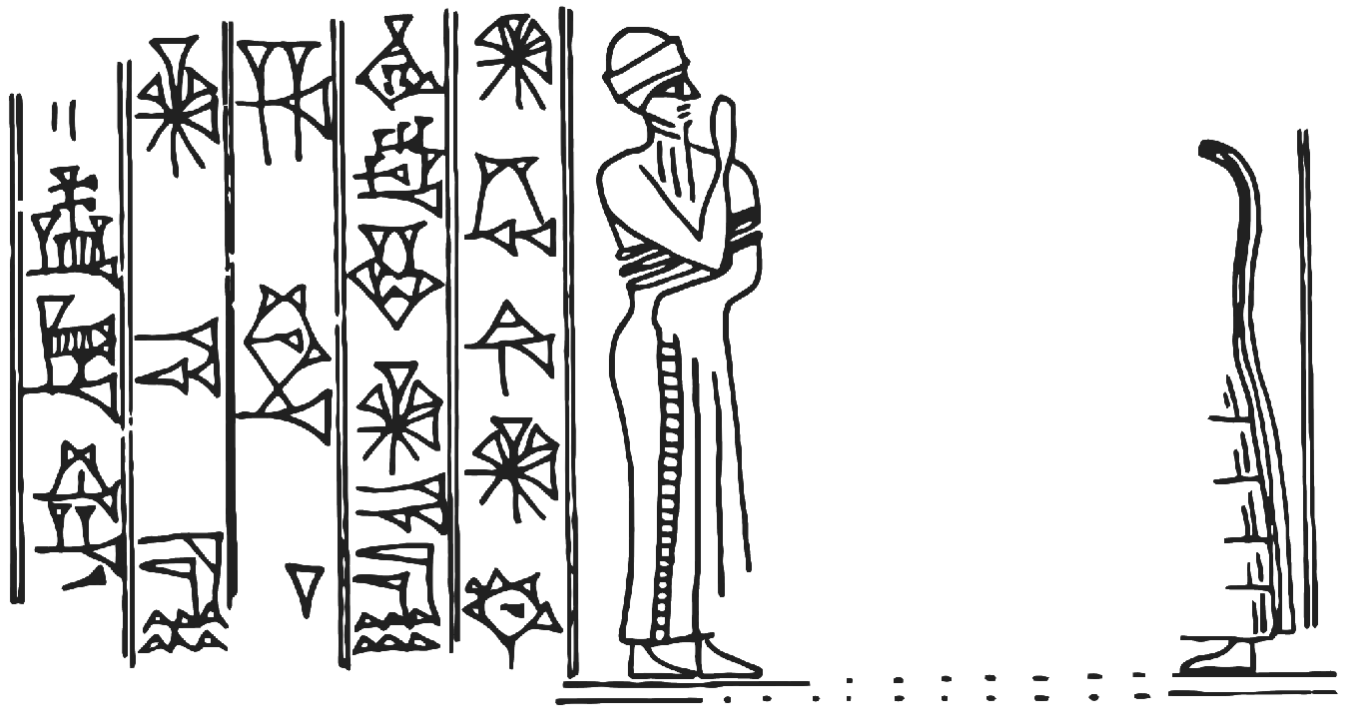

It is clear that an extensive long-distance Assyrian trade network was established relatively quickly, the first notable impression Assyria left in the historical record. Notable collections of Old Assyrian cuneiform tablets have been found in trading colonies established by the Assyrians in their trade network. The most notable locality excavated is

Kültepe

Kültepe ( Turkish: ''ash-hill''), also known as Kanesh or Nesha, is an archaeological site in Kayseri Province, Turkey, inhabited from the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, in the Early Bronze Age.Kloekhorst, Alwin, (2019)Kanišite Hittite: ...

, near the modern city of

Kayseri in Turkey. At this time, Kültepe was also a city-state ruled by its own line of kings. Over 22,000 Assyrian cuneiform clay tablets have been found at the site. In some way, Assur was able to maintain its central position in its trade network despite being small and having no known history of military success. Assur's importance as a trading center declined in the 19th century BC, perhaps chiefly because of increasing conflict between states and rulers of the ancient Near East leading to a general decrease in trade. From this time to the end of the Old Assyrian period, Assur frequently fell under the control of larger foreign states and empires. In particular, the nearby centers of

Eshnunna

Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar in Diyala Governorate, Iraq) was an ancient Sumerian (and later Akkadian) city and city-state in central Mesopotamia 12.6 miles northwest of Tell Agrab and 15 miles northwest of Tell Ishchali. Although situated in th ...

and

Ekallatum Ekallatum ( Akkadian: 𒌷𒂍𒃲𒈨𒌍, URUE2.GAL.MEŠ, Ekallātum, "the Palaces") was an ancient Amorite city-state and kingdom in upper Mesopotamia. The exact location of it has not yet been identified, but it is thought to be located somewher ...

threatened the continued existence of the Assur city-state. The original city-state came to an end 1808 BC when it was conquered by the

Amorite

The Amorites (; sux, 𒈥𒌅, MAR.TU; Akkadian: 𒀀𒈬𒊒𒌝 or 𒋾𒀉𒉡𒌝/𒊎 ; he, אֱמוֹרִי, 'Ĕmōrī; grc, Ἀμορραῖοι) were an ancient Northwest Semitic-speaking people from the Levant who also occupied la ...

ruler of Ekallatum,

Shamshi-Adad I

Shamshi-Adad ( akk, Šamši-Adad; Amorite: ''Shamshi-Addu''), ruled 1808–1776 BC, was an Amorite warlord and conqueror who had conquered lands across much of Syria, Anatolia, and Upper Mesopotamia.Some of the Mari letters addressed to Shamsi-Ad ...

, who deposed

Erishum II ErishumI or Erišum II, the son and successor of Naram-Sin, was the king of the city-state Assur from 1828/1818 BC to 1809 BC. Like his predecessors, he bore the titles “Išši’ak Aššur” (Steward of Assur) and “ensí”. The length of Er ...

, the last king of the Puzur-Ashur dynasty, and took the city for himself.

Shamshi-Adad's extensive conquests in northern Mesopotamia eventually made him the ruler of the entire region, founding what some scholars have termed the "

Kingdom of Upper Mesopotamia". To rule his realm, Shamshi-Adad established his capital at the city of

Shubat-Enlil. Around 1785 BC, Shamshi-Adad placed his two sons in control of different parts of the kingdom, the elder son

Yasmah-Adad

Yasmah-Adad (Yasmah-Addu, Yasmakh-Adad, Ismah-Adad, Iasmakh-Adad) was the younger son of the Amorite king of Upper Mesopotamia, Shamshi-Adad I. He was put on throne of Mari by his father after a successful military attack following the assassinati ...

being granted

Mari and the younger son

Ishme-Dagan I

Ishme-Dagan I ( akk, Išme-Dagān, script=Latn, italic=yes) was a monarch of Ekallatum and Assur during the Old Assyrian period. The much later Assyrian King List (AKL) credits Ishme-Dagan I with a reign of forty years; however, it is now known fr ...

being granted Ekallatum and Assur. Though the locals in Assur considered Shamshi-Adad and his family to be foreign conquerors, Shamshi-Adad did have certain respect for Assur and sometimes stayed in the city and partook in its religious ceremonies. Shamshi-Adad also oversaw the renovation of the city, the rebuilding of the temple of Ashur and the addition of a sanctuary dedicated to the head of the Mesopotamian pantheon,

Enlil. It is possible that Shamshi-Adad promoted a theology that equated Ashur and Enlil as one and the same. In that case, his theology was hugely influential as Assyrians in later times attributed the role of "king of the gods" to Ashur, a role otherwise typically attributed to Enlil. In the 18th century BC, Shamshi-Adad's kingdom became surrounded by competing large states, particularly the southern kingdoms of

Larsa

Larsa ( Sumerian logogram: UD.UNUGKI, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult ...

,

Babylon

''Bābili(m)''

* sux, 𒆍𒀭𒊏𒆠

* arc, 𐡁𐡁𐡋 ''Bāḇel''

* syc, ܒܒܠ ''Bāḇel''

* grc-gre, Βαβυλών ''Babylṓn''

* he, בָּבֶל ''Bāvel''

* peo, 𐎲𐎠𐎲𐎡𐎽𐎢 ''Bābiru''

* elx, 𒀸𒁀𒉿𒇷 ''Babi ...

and Eshnunna and the western kingdoms of

Yamhad

Yamhad was an ancient Semitic kingdom centered on Ḥalab (Aleppo), Syria. The kingdom emerged at the end of the 19th century BC, and was ruled by the Yamhadite dynasty kings, who counted on both military and diplomacy to expand their realm. ...

and

Qatna

Qatna (modern: ar, تل المشرفة, Tell al-Mishrifeh) (also Tell Misrife or Tell Mishrifeh) was an ancient city located in Homs Governorate, Syria. Its remains constitute a tell situated about northeast of Homs near the village of al-M ...

. The success and survival of his own realm chiefly relied on his personal strength and charisma. Shamshi-Adad's death in 1776 BC led to the collapse of the kingdom. His principal successor, Ishme-Dagan I, ruled from Ekallatum and retained control only of that city and of Assur.

The time between the collapse of Shamshi-Adad's kingdom in the 18th century BC and the rise of the

Middle Assyrian Empire

The Middle Assyrian Empire was the third stage of Assyrian history, covering the history of Assyria from the accession of Ashur-uballit I 1363 BC and the rise of Assyria as a territorial kingdom to the death of Ashur-dan II in 912 BC. ...

in the 14th century BC is often regarded by modern scholars as an Asyrian "Dark Age" due to the lack of sufficient historical evidence to clearly establish events during this time. It is clear from surviving records that the geopolitical situation in northern Mesopotamia was highly volatile, with frequent shifts in power. In 1772 BC

Ibal-pi-el II Ibal pi’el II was a king of the city kingdom of Eshnunna in ancient Mesopotamia. He reigned c. 1779–1765 BC).

He was the son of Dadusha and nephew of Naram-Suen of Eshnunna.

He conquered the cities of Diniktum and Rapiqum. With Ḫammu-rāp ...

of Eshnunna invaded and conquered Ishme-Dagan's kingdom, though he returned to power not long thereafter. A few years later, an army from

Elam

Elam (; Linear Elamite: ''hatamti''; Cuneiform Elamite: ; Sumerian: ; Akkadian: ; he, עֵילָם ''ʿēlām''; peo, 𐎢𐎺𐎩 ''hūja'') was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of modern-day Iran, stretc ...

invaded northern Mesopotamia and seized a few cities. In 1761 BC, Assur, perhaps only briefly, fell under the control of the

Old Babylonian Empire

The Old Babylonian Empire, or First Babylonian Empire, is dated to BC – BC, and comes after the end of Sumerian power with the destruction of the Third Dynasty of Ur, and the subsequent Isin-Larsa period. The chronology of the first dynasty ...

under

Hammurabi

Hammurabi (Akkadian: ; ) was the sixth Amorite king of the Old Babylonian Empire, reigning from to BC. He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered Elam and the city-states ...

. At some point, Assur returned to being an independent city-state. There was during this time also significant infighting within the government of Assur itself, as members of

Shamshi-Adad's dynasty fought with native Assyrians and Hurrians for control of the city. Eventually, the Shamshi-Adad dynasty's rule over Assur came to an end through the Assyrian usurper

Puzur-Sin Puzur-Sin was an Assyrian king in the 18th century BC, during the Old Assyrian period. One of the few known Assyrian rulers to be left out of the ''Assyrian King List'', Puzur-Sin was responsible for ending the rule of the dynasty of Shamshi-Adad I ...

re-establishing native rule. This did not mean an end to the troubles, as there was a time of non-dynastic kings and further infighting before the rise of

Bel-bani

Bel-bani or Bēl-bāni, inscribed mdEN''-ba-ni'', “the Lord is the creator,” was the king of Assyria from 1700 to 1691 BC and was the first ruler of what was later to be called the dynasty of the Adasides. His reign marks the inauguration of a ...

1700 BC. Bel-bani founded the

Adaside dynasty, which after his reign ruled Assyria for about a thousand years.

In large parts, the invasion or raid of Mesopotamia by the

Hittite king

Mursili I

Mursili I (also known as Mursilis; sometimes transcribed as Murshili) was a king of the Hittites 1620-1590 BC, as per the middle chronology, the most accepted chronology in our times, (or alternatively c. 1556–1526 BC, short chronology), and w ...

in 1595 BC was critical to Assyria's later development. This invasion destroyed the then dominant power in Mesopotamia, the Old Babylonian Empire, which created a vacuum of power that led to the formation of the

Kassite

The Kassites () were people of the ancient Near East, who controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire c. 1531 BC and until c. 1155 BC (short chronology).

They gained control of Babylonia after the Hittite sack of Babylon ...

kingdom of Babylonia in the south and the Hurrian

Mitanni

Mitanni (; Hittite cuneiform ; ''Mittani'' '), c. 1550–1260 BC, earlier called Ḫabigalbat in old Babylonian texts, c. 1600 BC; Hanigalbat or Hani-Rabbat (''Hanikalbat'', ''Khanigalbat'', cuneiform ') in Assyrian records, or ''Naharin'' in ...

state in the north. Assyrian rulers from 1520 to 1430 were more politically assertive than their predecessors, both regionally and internationally.

Puzur-Ashur III

Puzur-Ashur III was the king of Assyria from 1521 BC to 1498 BC. According to the Assyrian King List, he was the son and successor of Ashur-nirari I and ruled for 24 years (or 14 years, according to another copy). He is also the first Assyrian kin ...

( 1521–1498 BC) is the earliest Assyrian king to appear in the ''

Synchronistic History'', a later text concerning border disputes between Assyria and Babylonia, suggesting that Assyria first entered into diplomacy and conflict with Babylonia at this time and that Assur at this time ruled a small stretch of territory beyond the city itself. Around 1430 BC, Assur was subjugated by Mitanni and forced to become a vassal, an arrangement that lasted for about 70 years, until 1360 BC. Assur retained some autonomy under the Mitanni kings, as Assyrian kings during this time are attested as commissioning building projects, trading with Egypt and signing boundary agreements with the Kassites in Babylon. Another Hittite invasion, by

Šuppiluliuma I

Suppiluliuma I () or Suppiluliumas I () was king of the Hittites (r. c. 1344–1322 BC (short chronology)). He achieved fame as a great warrior and statesman, successfully challenging the then-dominant New Kingdom of Egypt, Egyptian Empire for con ...

in the 14th century BC, effectively crippled the Mitanni kingdom. After his invasion, Assyria succeeded in freeing itself from its suzerain, achieving independence once more under

Ashur-uballit I ( 1363–1328 BC), whose rise to power and independence traditionally marks the transition between the Old and Middle Assyrian periods.

Middle Assyrian period (1363–912 BC)

Rise of Assyria

Ashur-uballit I was the first native Assyrian ruler to claim the royal title ''šar'' ("king"). Shortly after achieving independence, he further claimed the dignity of a great king on the level of the Egyptian

pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: ''pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the an ...

s and the

Hittite kings The dating and sequence of the Hittite kings is compiled from fragmentary records, supplemented by the recent find in Hattusa of a cache of more than 3500 seal impressions giving names and titles and genealogy of Hittite kings. All dates given here ...

. Ashur-uballit's claim to be a great king meant that he also embedded himself in the ideological implications of that role; a great king was expected to expand the borders of his realm to incorporate "uncivilized" territories, ideally eventually ruling the entire world. Ashur-uballit's reign was often regarded by later generations of Assyrians as the true birth of Assyria. The term "land of

Ashur" (''māt Aššur''), i.e. designating Assyria as comprising a larger kingdom, is first attested as being used in his time. Assyria's rise was intertwined with the decline and fall of the Mitanni kingdom, its former suzerain, which allowed the early Middle Assyrian kings to expand and consolidate territories in northern Mesopotamia. Ashur-uballit mainly warred against small states in the southern vicinity of the Assyrian heartland. He engaged in diplomacy with both Babylonia, ruled by

Burnaburiash II

Burna-Buriaš II, rendered in cuneiform as ''Bur-na-'' or ''Bur-ra-Bu-ri-ia-aš'' in royal inscriptions and letters, and meaning ''servant'' or ''protégé of the Lord of the lands'' in the Kassite language, where Buriaš (, dbu-ri-ia-aš₂) is a ...

, and Egypt, ruled by

Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Echnaton, Akhenaton, ( egy, ꜣḫ-n-jtn ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning "Effective for the Aten"), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dy ...

. Ashur-uballit's successors

Enlil-nirari

Enlil-nirari (“ Enlil is my helper”) was King of Assyria from 1327 BC to 1318 BC during the Middle Assyrian Empire. He was the son of Aššur-uballiṭ I. He was apparently the earliest king to have been identified as having held eponym, o ...

( 1327–1318 BC) and

Arik-den-ili

Arik-den-ili, inscribed mGÍD-DI-DINGIR, “long-lasting is the judgment of god,” was King of Assyria 1317–1306 BC, ruling the Middle Assyrian Empire. He succeeded Enlil-nirari, his father, and was to rule for twelve years and inaugurate the t ...

( 1317–1306 BC) were less successful than Ashur-uballit in expanding and consolidating Assyrian power, and as such the new kingdom developed somewhat haltingly and remained fragile. Enlil-nirari's reign was the beginning of the historical enmity between Assyria and Babylonia after

Kurigalzu II

Kurigalzu II (c. 1332–1308 BC short chronology) was the 22nd king of the Kassite or 3rd dynasty that ruled over Babylon. In more than twelve inscriptions, Kurigalzu names Burna-Buriaš II as his father. Kurigalzu II was possibly placed on th ...

, a king the Assyrians had helped gain the Babylonian throne, attacked Assyria. Kurigalzu's betrayal resulted in deep trauma and was still referenced in Assyrian writings concerning Babylonia more than a century later.

Under the warrior-kings

Adad-nirari I ( 1305–1274 BC),

Shalmaneser I

Shalmaneser I (𒁹𒀭𒁲𒈠𒉡𒊕 md''sál-ma-nu-SAG'' ''Salmanu-ašared''; 1273–1244 BC or 1265–1235 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. Son of Adad-nirari I, he succeeded his father as king in 1265 BC.

Accord ...

( 1273–1244 BC) and

Tukulti-Ninurta I

Tukulti-Ninurta I (meaning: "my trust is in he warrior godNinurta"; reigned 1243–1207 BC) was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian Empire. He is known as the first king to use the title "King of Kings".

Biography

Tukulti-Ninurta I su ...

( 1243–1207 BC), Assyria began to realize its aspirations of becoming a significant regional power. Adad-nirari was the first Assyrian king to march against the remnants of the Mitanni kingdom and the first Assyrian king to include lengthy narratives of his campaigns in his royal inscriptions. Adad-nirari early in his reign defeated

Shattuara I of Mitanni and forced him to pay tribute to Assyria as a vassal ruler. After a revolt by Shattuara's son

Wasashatta

Wasashatta, also spelled Wasašatta, was a king of the Hurrian kingdom of Mittani ca. the early thirteenth century BC.

Like his father Shattuara, Wasashatta was an Assyrian vassal. He revolted against his master Adad-nirari I (c. 1295-1263 BC ( ...

Adad-niari annexed some Mitanni lands and constructed a royal palace for himself at

Taite Taite (called ''Taidu'' in Assyrian sources) was one of the capitals of the Mitanni Empire. Its exact location is still unknown, although it is speculated to be in the Khabur region. The site of Tell Hamidiya (Tall al-hamidiya) has recently been id ...

, a former Mitanni capital. Adad-nirari also fought with Babylonia, defeating the Babylonian king

Nazi-Maruttash

Nazi-Maruttaš, typically inscribed ''Na-zi-Ma-ru-ut-ta-aš'' or m''Na-zi-Múru-taš'', ''Maruttaš'' (a Kassite god synonymous with Ninurta) ''protects him'', was a Kassite king of Babylon c. 1307–1282 BC (short chronology) and self-proclaimed ...

at the

Battle of Kār Ištar

The Battle of Kār Ištar was a battle fought between Assyria and the Kassites of Babylon sometime during the reign of Assyrian king Adad-nirari I.

Under the reign of Assyrian King Ashur-uballit I, the Assyrians destroyed Mitanni, a kingdom in no ...

1280 BC and redrawing the border between the two kingdoms in Assyria's favor.

Assyrian campaigns and conquests intensified under Shalmaneser I. Shalmaneser's most significant wars were those directed towards the west. After the Mitanni king

Shattuara II Shattuara II, also spelled Šattuara II, was the last known king of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni (Hanigalbat) in the thirteenth century BC, before the Assyrian conquest.

A king named Shattuara is suggested to have ruled Hanigalbat during the reig ...

rebelled against Assyrian authority, Shalmaneser campaigned against him to suppress the resistance. As a result of Shalmaneser's victory in the campaign, the Mitanni capital of

Washukanni

Washukanni (also spelled Waššukanni) was the capital of the Hurrian kingdom of Mitanni, from around 1500 BC to the 13th century BC.

Location

The precise location of Waššukanni is unknown. A proposal by Dietrich Opitz located it under the lar ...

was sacked and the Mitanni lands were formally annexed into the Assyrian Empire. Shalmaneser's reign also saw worsening relations with the Hittites, who had supported Shattuara II's revolt. Shalmaneser warred several times against Hittite vassals in the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

. Conflict with the Hittites continued in the reign of Shalmaneser's son Tukulti-Ninurta I until the Assyrian victory at the

Battle of Nihriya

The Battle of Niḫriya was the culminating point of the hostilities between the Hittites and the Assyrians for control over the remnants of the former empire of Mitanni.

When Hittite king Šuppiluliuma I (r. c. 1344–1322 BC) conquered Mitanni, ...

1237 BC, which marked the beginning of the end of Hittite influence in northern Mesopotamia. In addition to his various campaigns and conquests, which brought the Middle Assyrian Empire to its greatest extent, Tukulti-Ninurta is also famous for being the first Assyrian king to transfer the capital of Assyria away from Assur itself. In his eleventh year as king ( 1233 BC), Tukulti-Ninurta inaugurated the new capital city

Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, named after himself (the name meaning "fortress of Tukulti-Ninurta"). The city only served as the capital during Tukulti-Ninurta's reign, with later kings returning to ruling from Assur.

Tukulti-Ninurta's main goal was Babylonia in the south; he intentionally escalated conflict with the Babylonian king

Kashtiliash IV

Kaštiliašu IV was the twenty-eighth Kassite king of Babylon and the kingdom contemporarily known as Kar-Duniaš, c. 1232–1225 BC ( short chronology). He succeeded Šagarakti-Šuriaš, who could have been his father, ruled for eight years,Ki ...

through claiming "traditionally Assyrian" lands along the eastern

Tigris

The Tigris () is the easternmost of the two great rivers that define Mesopotamia, the other being the Euphrates. The river flows south from the mountains of the Armenian Highlands through the Syrian and Arabian Deserts, and empties into the ...

river. Shortly thereafter, he invaded Babylonia in an unprovoked attack. After capturing cities such as

Sippar

Sippar ( Sumerian: , Zimbir) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its '' tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell Abu Habbah near Yusufiyah in Iraq's Baghdad Governorate, some ...

and

Dur-Kurigalzu

Dur-Kurigalzu (modern ' in Baghdad Governorate, Iraq) was a city in southern Mesopotamia, near the confluence of the Tigris and Diyala rivers, about west of the center of Baghdad. It was founded by a Kassite king of Babylon, Kurigalzu I (died ...

and defeating Kashtiliash in battle, Tukulti-Ninurta eventually succeeded in conquering Babylonia 1225 BC. He was the first Assyrian king to assume the traditionally southern Mesopotamian title "

king of Sumer and Akkad

King of Sumer and Akkad ( Sumerian: ''lugal-ki-en-gi-ki-uri'', Akkadian: ''šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi'') was a royal title in Ancient Mesopotamia combining the titles of "King of Akkad", the ruling title held by the monarchs of the Akkadian E ...

". Assyrian control over Babylonia was quite indirect, ruling through appointing vassal kings such as

Adad-shuma-iddina

Adad-šuma-iddina, inscribed mdIM-MU-SUM''-na'', ("Adad has given a name") and dated to around ca. 1222–1217 BC (short chronology), was the 31st king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon''Kinglist A'', BM 33332, ii 10. and the country conte ...

. After putting down a Babylonian uprising, Tukulti-Ninurta added to his title the style ''šamšu kiššat niše'' ("sun

odof all people"), a highly unusual style since the Assyrian king was typically regarded to be the representative of a god and not divine himself. Eventually Babylonia fell out of Tukulti-Ninurta's grasp. An uprising led by

Adad-shuma-usur

Adad-šuma-uṣur, inscribed dIM-MU-ŠEŠ, meaning "O Adad, protect the name!," and dated very tentatively ca. 1216–1187 BC (short chronology), was the 32nd king of the 3rd or Kassite dynasty of Babylon and the country contemporarily known as Ka ...

, perhaps a son of Kashtiliash IV, drove the Assyrians out of Babylonia 1216 BC. The loss of Babylonia increased growing dissatisfaction with Tukulti-Ninurta's rule. His long and prosperous reign ended with his assassination, which in turn was followed by inter-dynastic conflict and a significant drop in Assyrian power.

Troubles and decline

The successors of Tukulti-Ninurta were unable to maintain Assyrian power and the empire became increasingly restricted to just the Assyrian heartland. The decline of the Middle Assyrian Empire broadly coincided with the

Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a time of widespread societal collapse during the 12th century BC, between c. 1200 and 1150. The collapse affected a large area of the Eastern Mediterranean (North Africa and Southeast Europe) and the Near East ...

, a time when the ancient Near East experienced monumental geopolitical changes; within a single generation, the Hittite Empire and the Kassite dynasty of Babylon had fallen, and Egypt had been severely weakened through losing its lands in the Levant. Modern researchers tend to varyingly ascribe the Bronze Age collapse to large-scale migrations, invasions by the mysterious

Sea Peoples

The Sea Peoples are a hypothesized seafaring confederation that attacked ancient Egypt and other regions in the East Mediterranean prior to and during the Late Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE).. Quote: "First coined in 1881 by the Fren ...

, new warfare technology and its effects, starvation, epidemics, climate change and an unsustainable exploitation of the working population. Tukulti-Ninurta's direct dynastic line came to an end 1192 BC, when the grand vizier

Ninurta-apal-Ekur

Ninurta-apal-Ekur, inscribed mdMAŠ-A-''é-kur'', meaning “Ninurta is the heir of the Ekur,” was a king of Assyria in the early 12th century BC who usurped the throne and styled himself king of the universe and priest of the gods Enlil and Ninu ...

, a descendant of Adad-nirari I, took the throne for himself. Ninurta-apal-Ekur and his immediate successors were no more able than Tukulti-Ninurta's descendants to halt the decline of the empire.

Ninurta-apal-Ekur's son

Ashur-dan I

Aššur-dān I, m''Aš-šur-dān''(kal)an, was the 83rd king of Assyria, reigning for 46Khorsabad King List and the SDAS King List both read, iii 19, 46 MU.MEŠ KI.MIN. (variant: 36Nassouhi King List reads, 26+x MU. EŠ LUGAL-ta DU.uš.) years, c. ...

( 1178–1133 BC), improved the situation somewhat, campaigning against the Babylonian king

Zababa-shuma-iddin, but his two sons

Ninurta-tukulti-Ashur

Ninurta-tukultī-Aššur, inscribed md''Ninurta''2''-tukul-ti-Aš-šur'', was briefly king of Assyria 1132 BC, the 84th to appear on the Assyrian Kinglist, marked as holding the throne for his ''ṭuppišu'', "his tablet," a period thought to corr ...

and

Mutakkil-Nusku

Mutakkil-Nusku, inscribed m''mu-ta''/''tak-kil-''dPA.KU, "he whom Nusku endows with confidence," was king of Assyria

Assyria ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian ...

struggled for power with each other after his death. Though Mutakkil-Nusku emerged victorious, he ruled for less than a year. Mutakkil-Nusku warred against the Babylonian king

Itti-Marduk-balatu

Itti-Marduk-balāṭu may refer to

Known period

* Itti-Marduk-balāṭu (vizier), vizier to Kassite Babylonian king Kadašman-Enlil II, ca. 1263 BC

* Itti-Marduk-balāṭu (eunuch), Kassite Babylonian king Meli-Šipak’s (ca. 1186–1172 BC) e ...

, a conflict which continued in the reign of his son

Ashur-resh-ishi I (1132–1115 BC). In the

Synchronistic History (a later Assyrian document), Ashur-resh-ishi is cast as a savior of the Assyrian Empire, defeating the Babylonian king

Nebuchadnezzar I

Nebuchadnezzar I or Nebuchadrezzar I (), reigned 1121–1100 BC, was the fourth king of the Second Dynasty of Isin and Fourth Dynasty of Babylon. He ruled for 22 years according to the ''Babylonian King List C'', and was the most prominent monar ...

in several battles. In some of his inscriptions, Ashur-resh-ishi claimed the epithet "avenger of Assyria" (''mutēr gimilli māt Aššur'').

Due to Ashur-resh-ishi's victories over Babylonia, his son

Tiglath-Pileser I

Tiglath-Pileser I (; from the Hebraic form of akk, , Tukultī-apil-Ešarra, "my trust is in the son of Ešarra") was a king of Assyria during the Middle Assyrian period (1114–1076 BC). According to Georges Roux, Tiglath-Pileser was "one of t ...

(1114–1076 BC) could focus his attention on other territories without worrying about southern attacks. Texts written already during his first few regnal years demonstrate that Tiglath-Pileser ruled with more confidence than his immediate predecessors, using titles such as "unrivalled

king of the universe

King of the Universe ( Sumerian: ''lugal ki-sár-ra'' or ''lugal kiš-ki'', Akkadian: ''šarru kiššat māti'', ''šar-kiššati'' or ''šar kiššatim''), also interpreted as King of Everything, King of the Totality, King of All or King of the ...

,

king of the four quarters

King of the Four Corners of the World ( Sumerian: ''lugal-an-ub-da-limmu-ba'', Akkadian: ''šarru kibrat 'arbaim'', ''šar kibrāti arba'i'', or ''šar kibrāt erbetti''), alternatively translated as King of the Four Quarters of the World, King ...

, king of all princes, lord of lords" and epithets such as "splendid flame which covers the hostile land like a rain storm". Tiglath-Pileser went on significant campaigns to the west and north, incorporating both territories lost after Tukulti-Ninurta's reign and territories that had never before been under Assyrian rule. Tiglath-Pileser's inscriptions are the first Assyrian inscriptions to describe punitive measures against rebelling cities and regions in any detail. He also increased the size of the Assyrian cavalry and introducing

war chariots

A chariot is a type of cart driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, dated to c. 2000&nb ...

on a grander scale than previous kings. Though one of the most successful Middle Assyrian kings, Tiglath-Pileser's conquests were not long-lasting and several territories, especially in the west, were likely lost again before his death. Assyria became overstretched and Tiglath-Pileser's successors were forced to adapt to be on the defensive. An increasing problem from the late reign of Tiglath-Pileser onwards were the

Aramean

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean h ...

tribes in the west. Due to the Aramean tactics of avoiding open battle and instead attacking the Assyrians in numerous minor skirmishes, the Assyrian army could in conflict with them not take advantage of their technical and numerical superiority.

From the time of

Eriba-Adad II Erība-Adad II, inscribed mSU-dIM, “Adad has replaced,” was the king of Assyria 1056/55–1054 BC, the 94th to appear on the ''Assyrian Kinglist''.''SDAS Kinglist'', iii 31.''Nassouhi Kinglist'', iv 12. He was the son of Aššur-bēl-kala whom ...

(1056–1054 BC) onwards, the kings were unable to maintain the achievements of their predecessors. This period of renewed decline was not reversed until the middle of the 10th century BC. Though this period is poorly documented, it is clear that Assyria underwent a major crisis. The Arameans continued to be Assyria's most prominent enemies, at times raiding deep into the Assyrian heartland. Their attacks were uncoordinated raids carried out by individual groups, which meant that even though the Assyrians defeated several Aramean groups in battle, their

guerrilla tactics

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics ...

and ability to withdraw into difficult terrain quickly prevented the Assyrians from ever achieving a lasting victory. Though control was lost over most of the Assyrian Empire, the Assyrian heartland remained safe and intact, protected by its geographical remoteness. Assyria was not the only realm fragmented during this period, which meant that the fragmented territories now surrounding the Assyrian heartland in time proved to be easy conquests for the Assyrian army.

Ashur-dan II

Ashur-Dan II (Aššur-dān) (934–912 BC), son of Tiglath Pileser II, was the earliest king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. He was best known for recapturing previously held Assyrian territory and restoring Assyria to its natural borders, from Tur ...

(934–912 BC) reversed Assyrian decline, campaigning in the peripheries of the Assyrian heartland, primarily in the northeast and northwest. His campaigns paved the way for grander efforts to restore and expand Assyrian power under his successors and the end of his reign marks the transition to the

Neo-Assyrian period

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history and the final and greatest phase of Assyria as an independent state. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew t ...

.

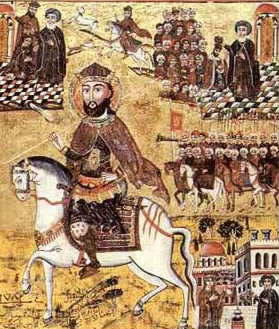

Neo-Assyrian period (911–609 BC)

Revitalization, expansion and dominance

Through decades of military conquests, the early Neo-Assyrian kings worked to retake the former lands of their empire and re-establish the position of Assyria as it was at the height of the Middle Assyrian Empire. The reigns of

Adad-nirari II

Adad-nirari II (reigned from 911 to 891 BC) was the first King of Assyria in the Neo-Assyrian period.

Biography

Adad-nirari II's father was Ashur-dan II, whom he succeeded after a minor dynastic struggle. It is probable that the accession encour ...

(911–891 BC) and

Tukulti-Ninurta II Tukulti-Ninurta II was King of Assyria from 890 BC to 884 BC. He was the second king of the Neo Assyrian Empire.

History

His father was Adad-nirari II, the first king of the Neo-Assyrian period. Tukulti-Ninurta consolidated the gains made by his f ...

(890–884 BC) saw the slow beginning of this project. Since the ''reconquista'' had to begun nearly from scratch, its eventual success was an extraordinary achievement. Adad-nirari's most important conquest was the city of

Arrapha

Arrapha or Arrapkha (Akkadian: ''Arrapḫa''; ar, أررابخا ,عرفة) was an ancient city in what today is northeastern Iraq, thought to be on the site of the modern city of Kirkuk.

In 1948, ''Arrapha'' became the name of the residential ...

(modern-day

Kirkuk

Kirkuk ( ar, كركوك, ku, کەرکووک, translit=Kerkûk, , tr, Kerkük) is a city in Iraq, serving as the capital of the Kirkuk Governorate, located north of Baghdad. The city is home to a diverse population of Turkmens, Arabs, Kurds, ...

), which in later times served as the launching point of innumerable Assyrian campaigns to the east. Adad-nirari also managed to secure a border agreement with the Babylonian king

Nabu-shuma-ukin I

Nabû-šuma-ukin I, inscribed md''Nābû-šuma-ú-kin'',''Synchronistic King List'' iii 16 and variant fragments KAV 10 ii 7, KAV 182 iii 10. meaning “Nabû has established legitimate progeny,” was the 5th king listed in the sequence of the so ...

, a clear indicator that Assyrian power was on the rise. The second and more substantial phase of early Neo-Assyrian expansion began under Tukulti-Ninurta's son

Ashurnasirpal II (883–859 BC), whose conquests made the Neo-Assyrian Empire the dominant political power in the Near East.

One of Ashurnasirpal's most persistent enemies was the Aramean king

Ahuni of

Bit Adini

Bit Adini, a city or region of Syria, called sometimes ''Bit Adini'' in Assyrian sources, was an Aramaean state that existed as an independent kingdom during the 10th and 9th centuries BC, with its capital at Til Barsib (now Tell Ahmar). The city ...

. Ahuni's forces broke through across the Khabur and Euphrates several times and it was only after years of war that he at last accepted Ashurnasirpal as his

suzerain

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is calle ...

. Ahuni's defeat was highly important since it marked the first time since

Ashur-bel-kala

Aššūr-bēl-kala, inscribed m''aš-šur-''EN''-ka-la'' and meaning “Aššur is lord of all,” was the king of Assyria 1074/3–1056 BC, the 89th to appear on the ''Assyrian Kinglist''. He was the son of Tukultī-apil-Ešarra I, succeeded his ...

(1073–1056 BC), two centuries prior, that Assyrian forces had the opportunity to campaign further west than the Euphrates. Making use of this opportunity, Ashurnasirpal in his ninth campaign marched to the coast of the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

, collecting tribute from various kingdoms on the way. A significant development during Ashurnasirpal's reign was the second transfer of the Assyrian capital away from Assur. Ashurnasirpal restored the ancient and ruined town of

Nimrud

Nimrud (; syr, ܢܢܡܪܕ ar, النمرود) is an ancient Assyrian city located in Iraq, south of the city of Mosul, and south of the village of Selamiyah ( ar, السلامية), in the Nineveh Plains in Upper Mesopotamia. It was a majo ...

, also located in the Assyrian heartland, and in 879 BC designated that city as the new capital of the empire, employing thousands of workers to construct new fortifications, palaces and temples in the city. Though no longer the political capital, Assur remained the ceremonial and religious center of Assyria.

The reign of Ashurnasirpal's son

Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (''Šulmānu-ašarēdu'', "the god Shulmanu is pre-eminent") was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Ashurnasirpal II in 859 BC to his own death in 824 BC.

His long reign was a constant series of campai ...

(859–824 BC) also saw a considerable expansion of Assyrian territory. Lands conquered under Ashurnasirpal were consolidated and divided into further provinces and Shalmaneser's campaigns were also more wide-ranging than those of his predecessors. The most powerful and threatening enemy of Assyria at this point was

Urartu

Urartu (; Assyrian: ',Eberhard Schrader, ''The Cuneiform inscriptions and the Old Testament'' (1885), p. 65. Babylonian: ''Urashtu'', he, אֲרָרָט ''Ararat'') is a geographical region and Iron Age kingdom also known as the Kingdom of Va ...

in the north; following in the footsteps of the Assyrians, the Urartian administration, culture, writing system and religion closely followed those of Assyria. The Urartian kings were also autocrats very similar to the Assyrian kings. The imperialist expansionism of both states often led to military clashes, despite being separated by the

Taurus Mountains

The Taurus Mountains ( Turkish: ''Toros Dağları'' or ''Toroslar'') are a mountain complex in southern Turkey, separating the Mediterranean coastal region from the central Anatolian Plateau. The system extends along a curve from Lake Eğirdir ...

. Shalmaneser for a time neutralized the Urartian threat after he in an ambitious campaign in 856 BC sacked the Urartian capital of

Arzashkun

Arzashkun or Arṣashkun (Armenian: Արծաշկուն) was the capital of the early kingdom of Urartu in the 9th century BC, before Sarduri I moved it to Tushpa in 832 BC. Arzashkun had double walls and towers, but was captured by Shalmaneser III ...

and devastated the heartland of the kingdom. In 853 BC, Shalmaneser was forced to fight against a large coalition of western states assembled at

Tell Qarqur

, alternate_name =

, image = Qarquruppertell.jpg

, alt = Photograph of a double, overgrown mound

, caption = The upper mound of Tell Qarqur as seen from the northern, lower mound

, map_type = Syria

, map_alt =

, map_size =

, loc ...

in Syria, led by

Hadadezer

Hadadezer (; "he god Hadad is help"); also known as Adad-Idri ( akk, 𒀭𒅎𒀉𒊑, dIM-id-ri), and possibly the same as Bar-Hadad II ( Aram.) or Ben-Hadad II ( Heb.), was the king of Aram Damascus between 865 and 842 BC.

The Hebrew Bible st ...

, the king of

Aram-Damascus

The Kingdom of Aram-Damascus () was an Aramean polity that existed from the late-12th century BCE until 732 BCE, and was centred around the city of Damascus in the Southern Levant. Alongside various tribal lands, it was bounded in its later ye ...

. Though Shalmaneser fought them at the

Battle of Qarqar

The Battle of Qarqar (or Ḳarḳar) was fought in 853 BC when the army of the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by Emperor Shalmaneser III encountered an allied army of eleven kings at Qarqar led by Hadadezer, called in Assyrian ''Adad-idir'' and possibly ...

in the same year, the battle appears to have been indecisive. After Qarqar, Shalmaneser focused on the south. He allied with the Babylonian king

Marduk-zakir-shumi I

Marduk-zâkir-šumi, inscribed mdAMAR.UTU''-za-kir-''MU in a reconstruction of two kinglists,''Synchronistic Kinglist'' KAV 10 (VAT 11261) ii 9.''Synchronistic Kinglist'' KAV 182 (Ass. 13956dh) iii 12. “Marduk pronounced the name,” was a king ...

, aiding his southern neighbor in both defeating the usurper

Marduk-bel-ushati and in fighting against the

Chaldea

Chaldea () was a small country that existed between the late 10th or early 9th and mid-6th centuries BCE, after which the country and its people were absorbed and assimilated into the indigenous population of Babylonia. Semitic-speaking, it was ...

ns in the far south of Mesopotamia. After the death of Hadadezer in 841 BC, Shalmaneser managed to incorporate some further western territories. In the 830s, his armies reached into

Cilicia

Cilicia (); el, Κιλικία, ''Kilikía''; Middle Persian: ''klkyʾy'' (''Klikiyā''); Parthian: ''kylkyʾ'' (''Kilikiyā''); tr, Kilikya). is a geographical region in southern Anatolia in Turkey, extending inland from the northeastern coa ...

in

Anatolia

Anatolia, tr, Anadolu Yarımadası), and the Anatolian plateau, also known as Asia Minor, is a large peninsula in Western Asia and the westernmost protrusion of the Asian continent. It constitutes the major part of modern-day Turkey. The ...

and in 836, Shalmaneser reached

Ḫubušna (near modern-day

Ereğli), one of the westernmost places ever reached by Assyrian forces. Though successful, Shalmaneser's conquests had been very quick and had not been fully consolidated by the time of his death.

From the late reign of Shalmaneser III onwards, the Neo-Assyrian Empire entered into what scholars call the "age of the magnates", when powerful officials and generals were the principal wielders of political power, rather than the king. The last few campaigns of Shalmaneser's reign were not led by the king, probably on account of old age, but rather by the ''

turtanu "Turtanu" or "Turtan" (Akkadian: 𒌉𒋫𒉡 ''tur-ta-nu''; he, תַּרְתָּן ''tartān''; el, Θαρθαν; la, Tharthan; arc, ܬܵܪܬܵܢ ''tartan'') is an Akkadian word/title meaning 'commander in chief' or 'prime minister'. In Assyri ...

'' (commander-in-chief)

Dayyan-Assur

Dayyan-Assur was commander-in-chief, or Tartan (turtānu), of the Assyrian army during the reign of Shalmaneser III (859 - 824 BC).

According to the Black Obelisk, he personally led some of the military campaigns outside Assyria, which is rather u ...

. Shalmaneser's final years became preoccupied by an internal crisis when one of his sons,

Ashur-danin-pal, rebelled in an attempt to seize the throne, possibly because the younger son

Shamshi-Adad had been designated as heir instead of himself. When Shalmaneser died in 824 BC, Ashur-danin-pal was still in revolt, supported by a significant portion of the country, most notably the former capital of Assur. Shamshi-Adad acceded to the throne as Shamshi-Adad V, perhaps initially a minor and a puppet of Dayyan-Assur. Though Dayyan-Assur died during the early stages of the civil war, Shamshi-Adad was eventually victorious, apparently due to help from the Babylonian king Marduk-zakir-shumi or his successor

Marduk-balassu-iqbi

Marduk-balāssu-iqbi, inscribed mdAMAR.UTU-TI''-su-iq-bi''Kudurru AO 6684 in the Louvre, published as RA 16 (1919) 126 iv 17. or mdSID-TI-''zu''-DUG4,''Synchronistic King List'' fragment, Ass 13956dh (KAV 182), iii 13. meaning "Marduk has promised ...

. The age of the magnates is typically characterized as a period of decline, with little to no territorial expansion and weak central power. This does not mean that there were no successes in this time. In 812 BC, Shamshi-Adad managed to termporarily conquer large portions of Babylonia and numerous campaigns were conducted under his son

Adad-nirari III

Adad-nirari III (also Adad-narari) was a King of Assyria from 811 to 783 BC. Note that this assumes that the longer version of the Assyrian Eponym List, which has an additional eponym for Adad-nirari III, is the correct one. For the shorter eponym ...

(811–783 BC) which resulted in new territory both in the west and east. Early in Adad-nirari's reign, Adad-nirari and his mother

Shammuramat

Shammuramat (Akkadian: ''Sammu-rāmat'' or ''Sammu-ramāt''), also known as Sammuramat or Shamiram, was a powerful queen of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. Beginning her career as the primary consort of the king Shamshi-Adad V (824–811 BC), Shammura ...

expanded Assyrian control in Syria. The low point of the age of the magnates were the reigns of Adad-nirari's sons

Shalmaneser IV

Shalmaneser IV ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 783 BC to his death in 773 BC. Shalmaneser was the son and successor of his predecessor, Adad-nirari III, and ruled during a pe ...

(783–773 BC),

Ashur-dan III

Ashur-dan III ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning " Ashur is strong") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 773 BC to his death in 755 BC. Ashur-dan was a son of Adad-nirari III (811–783 BC) and succeeded his brother Shalmaneser IV as kin ...

(773–755 BC) and

Ashur-nirari V

Ashur-nirari V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning " Ashur is my help") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 755 BC to his death in 745 BC. Ashur-nirari was a son of Adad-nirari III (811–783 BC) and succeeded his brother Ashur-dan III as ...

(755–745 BC), from which very few royal documents are known and officials grew even more bold, in some cases no longer even crediting the kings for their achievements.

Ashur-nirari V was succeeded by

Tiglath-Pileser III

Tiglath-Pileser III ( Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "my trust belongs to the son of Ešarra"), was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 745 BC to his death in 727. One of the most prominent and historically significant Assyrian kings, T ...

(745–727 BC), probably his brother and generally assumed to have usurped the throne. Tiglath-Pileser's accession ushered in a new age of the Neo-Assyrian Empire; while the conquests of earlier kings were impressive, they contributed little to Assyria's full rise as a consolidated empire. Through campaigns aimed at outright conquest and not just extraction of seasonal tribute, as well as reforms meant to efficiently organize the army and centralize the realm, Tiglath-Pileser is by some regarded as the first true initiator of Assyria's "imperial" phase. Tiglath-Pileser is the earliest Assyrian king mentioned in the

Babylonian Chronicles

The Babylonian Chronicles are a series of tablets recording major events in Babylonian history. They are thus one of the first steps in the development of ancient historiography. The Babylonian Chronicles were written in Babylonian cuneiform, fr ...

and in the

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

and thus the earliest king for which there exists important outside perspectives on his reign. Early on, Tiglath-Pileser reduced the influence of the powerful magnates. Tiglath-Pileser campaigned in all directions with resounding success. His most impressive achievements were the conquest and vassalization of the

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

all the way to the Egyptian border and the 729 conquest of Babylonia, after which he and later Assyrian kings often ruled as both "king of Assyria" and "king of Babylon". By the time of his death in 727 BC, Tiglath-Pileser had more than doubled the territory of the empire. His policy of direct rule rather than rule through vassal states brought important changes to the Assyrian state and its economy; rather than tribute, the empire grew more reliant on taxes collected by provincial governors, a development which increased administrative costs but also reduced the need for military intervention. Also noteworthy was the large scale in which Tiglath-Pileser undertook

resettlement policies, settling tens, if not hundreds, of thousand foreigners in both the Assyrian heartland and in far-away underdeveloped provinces.

Sargonid dynasty

Tiglath-Pileser's son

Shalmaneser V

Shalmaneser V (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "Salmānu is foremost"; Biblical Hebrew: ) was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Tiglath-Pileser III in 727 BC to his deposition and death in 722 BC. Though Shalman ...

(727–722 BC) was after only a brief reign usurped by

Sargon II

Sargon II (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is general ...

(722–705 BC), either his brother or a non-dynastic usurper. Sargon founded the

Sargonid dynasty, which would rule until the fall of the Assyrian Empire. Sargon's accession, possible marking the end of the nearly thousand-year long Adaside dynasty, was met with considerable internal unrest. In his own inscriptions Sargon claims to have deported 6,300 "guilty Assyrians", probably Assyrians from the heartland who opposed his accession. Several peripheral regions of the empire also revolted and regained their independence. The most significant of the revolts was the successful uprising of the Chaldean warlord

Marduk-apla-iddina II

Marduk-apla-iddina II (Akkadian language, Akkadian: ; in the Bible Merodach-Baladan, also called Marduk-Baladan, Baladan and Berodach-Baladan, lit. ''Marduk has given me an heir'') was a Chaldean leader from the Bit-Yakin tribe, originally establi ...

, who took control of Babylon, restoring Babylonian independence, and allied with the Elamite king

Ḫuban‐nikaš I. While Sargon was campaigning in the east in 720 BC, his generals also put down a major revolt in the western provinces, led by

Yau-bi'di of

Hamath

, timezone = EET

, utc_offset = +2

, timezone_DST = EEST

, utc_offset_DST = +3

, postal_code_type =

, postal_code =

, ar ...

.

After securing the silver treasury of the city of

Carchemish

Carchemish ( Turkish: ''Karkamış''; or ), also spelled Karkemish ( hit, ; Hieroglyphic Luwian: , /; Akkadian: ; Egyptian: ; Hebrew: ) was an important ancient capital in the northern part of the region of Syria. At times during its ...

in 717 BC, Sargon began construction of another new imperial capital. The new city was named

Dur-Sharrukin

Dur-Sharrukin ("Fortress of Sargon"; ar, دور شروكين, Syriac: ܕܘܪ ܫܪܘ ܘܟܢ), present day Khorsabad, was the Assyrian capital in the time of Sargon II of Assyria. Khorsabad is a village in northern Iraq, 15 km northeast of Mo ...

("Fort Sargon") after himself. Unlike Ashurnasirpal's project at Nimrud, Sargon was not simply expanding an existing, albeit ruined, site but building a new settlement from scratch. Sargon was militarily successful and frequently went to war. Between just 716 and 713, Sargon fought against Urartu, the

Medes

The Medes (Old Persian: ; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Greek: ; Latin: ) were an ancient Iranian people who spoke the Median language and who inhabited an area known as Media between western and northern Iran. Around the 11th century BC, the ...

, Arab tribes, and

Ionian pirates in the eastern Mediterranean. In 710 BC, Sargon retook Babylon, driving Marduk-apla-iddina into exile in Elam. Between 710 and 707 BC, Sargon resided in Babylon, receiving foreign delegations there and participating in local traditions, such as the ''

Akitu

Akitu or Akitum is a spring festival held on the first day of Nisan in ancient Mesopotamia, to celebrate the sowing of barley. The Assyrian and Babylonian Akitu festival has played a pivotal role in the development of theories of religion, myth ...

'' festival. In 707 BC, Sargon returned to Nimrud and in 706 BC, Dur-Sharrukin was inaugurated as the empire's new capital. Sargon did not get to enjoy his new city for long; in 705 BC he embarked on his final campaign, directed against

Tabal

Tabal (c.f. biblical ''Tubal''; Assyrian: 𒋫𒁄) was a Luwian speaking Neo-Hittite kingdom (and/or collection of kingdoms) of South Central Anatolia during the Iron Age. According to archaeologist Kurt Bittel, references to Tabal first appear ...

, and died in battle in Anatolia.

Sargon's son

Sennacherib

Sennacherib (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: or , meaning " Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from the death of his father Sargon II in 705BC to his own death in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynast ...

(705–681 BC) moved the capital to