History of Scandinavia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Scandinavia is the history of the geographical region of

Even though Scandinavians joined the European

Even though Scandinavians joined the European

Since prehistoric times, the Sami people of Arctic Europe have lived and worked in an area that stretches over the northern parts of the regions now known as Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola Peninsula. They have inhabited the northern arctic and sub-arctic regions of Fenno-Scandinavia and Russia for at least 5,000 years. The Sami are counted among the Arctic peoples and are members of circumpolar groups such as the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat.

Petroglyphs and archeological findings such as settlements dating from about 10,000 B.C. can be found in the traditional lands of the Sami. These hunters and gatherers of the late Paleolithic and early Mesolithic were named

Since prehistoric times, the Sami people of Arctic Europe have lived and worked in an area that stretches over the northern parts of the regions now known as Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola Peninsula. They have inhabited the northern arctic and sub-arctic regions of Fenno-Scandinavia and Russia for at least 5,000 years. The Sami are counted among the Arctic peoples and are members of circumpolar groups such as the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat.

Petroglyphs and archeological findings such as settlements dating from about 10,000 B.C. can be found in the traditional lands of the Sami. These hunters and gatherers of the late Paleolithic and early Mesolithic were named

During the Viking Age, the

During the Viking Age, the

The age of settlement began around 800 AD . The Vikings invaded and eventually settled in Scotland , England,

The age of settlement began around 800 AD . The Vikings invaded and eventually settled in Scotland , England,

Viking religious beliefs were heavily connected to

Viking religious beliefs were heavily connected to

The Kalmar Union (Danish/Norwegian/Swedish: ''Kalmarunionen'') was a series of

The Kalmar Union (Danish/Norwegian/Swedish: ''Kalmarunionen'') was a series of

The Danish intervention began when Christian IV (1577–1648) the King of Denmark-Norway, himself a Lutheran, helped the German Protestants by leading an army against the Holy Roman Empire, fearing that Denmark's sovereignty as a Protestant nation was being threatened. The period began in 1625 and lasted until 1629. Christian IV had profited greatly from his policies in northern Germany (Hamburg had been forced to accept Danish sovereignty in 1621, and in 1623 the Danish heir apparent was made Administrator of the Prince-Bishopric of Verden. In 1635 he became Administrator of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen too.) As an administrator, Christian IV had done remarkably well, obtaining for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe, paid for by the

The Danish intervention began when Christian IV (1577–1648) the King of Denmark-Norway, himself a Lutheran, helped the German Protestants by leading an army against the Holy Roman Empire, fearing that Denmark's sovereignty as a Protestant nation was being threatened. The period began in 1625 and lasted until 1629. Christian IV had profited greatly from his policies in northern Germany (Hamburg had been forced to accept Danish sovereignty in 1621, and in 1623 the Danish heir apparent was made Administrator of the Prince-Bishopric of Verden. In 1635 he became Administrator of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen too.) As an administrator, Christian IV had done remarkably well, obtaining for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe, paid for by the

The Swedish rise to power began under the rule of Charles IX. During the Ingrian War Sweden expanded its territories eastward. Several other wars with Poland, Denmark-Norway, and German countries enabled further Swedish expansion, although there were some setbacks such as the Kalmar War. Sweden began consolidating its empire. Several other wars followed soon after including the Northern Wars and the

The Swedish rise to power began under the rule of Charles IX. During the Ingrian War Sweden expanded its territories eastward. Several other wars with Poland, Denmark-Norway, and German countries enabled further Swedish expansion, although there were some setbacks such as the Kalmar War. Sweden began consolidating its empire. Several other wars followed soon after including the Northern Wars and the

Scandinavia was divided during the Napoleonic Wars. Denmark-Norway tried to remain neutral but became involved in the conflict after British demands to turn over the navy. Britain thereafter attacked the Danish fleet at the battle of Copenhagen (1801) and bombarded the city during the second

Scandinavia was divided during the Napoleonic Wars. Denmark-Norway tried to remain neutral but became involved in the conflict after British demands to turn over the navy. Britain thereafter attacked the Danish fleet at the battle of Copenhagen (1801) and bombarded the city during the second

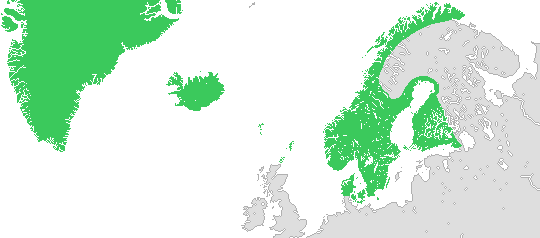

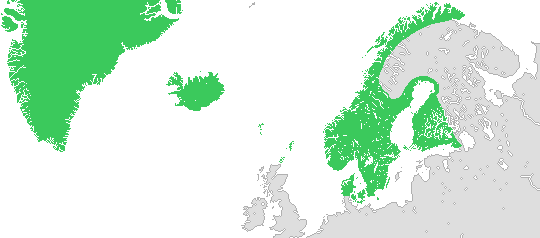

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

and its peoples. The region is located in Northern Europe, and consists of Denmark

)

, song = ( en, "King Christian stood by the lofty mast")

, song_type = National and royal anthem

, image_map = EU-Denmark.svg

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of Denmark

, establishe ...

, Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

and Sweden. Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of Bo ...

and Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

are at times, especially in English-speaking contexts, considered part of Scandinavia.

Pre-historic age

Little evidence remains in Scandinavia of the Stone Age, theBronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

, or the Iron Age

The Iron Age is the final epoch of the three-age division of the prehistory and protohistory of humanity. It was preceded by the Stone Age (Paleolithic, Mesolithic, Neolithic) and the Bronze Age (Chalcolithic). The concept has been mostly appl ...

except limited numbers of tools created from stone, bronze, and iron, some jewelry and ornaments, and stone burial cairns. One important collection that exists, however, is a widespread and rich collection of stone drawings known as petroglyph

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other descriptions ...

s.

Stone Age

During the Weichselian glaciation, almost all of Scandinavia was buried beneath a thick permanent sheet of ice and the Stone Age was delayed in this region. Some valleys close to the watershed were indeed ice-free around 30 000 years B.P. Coastal areas were ice-free several times between 75 000 and 30 000 years B.P. and the final expansion towards the late Weichselian maximum took place after 28 000 years B.P. As the climate slowly warmed up at the end of the ice age and deglaciation took place, nomadic hunters from central Europe sporadically visited the region, but it was not until around 12,000 BCE before permanent, but nomadic, habitation took root.Upper Paleolithic

As the ice receded,reindeer

Reindeer (in North American English, known as caribou if wild and ''reindeer'' if domesticated) are deer in the genus ''Rangifer''. For the last few decades, reindeer were assigned to one species, ''Rangifer tarandus'', with about 10 subsp ...

grazed on the flat lands of Denmark and southernmost Sweden. This was the land of the Ahrensburg culture

The Ahrensburg culture or Ahrensburgian (c. 12,900 to 11,700 BP) was a late Upper Paleolithic nomadic hunter culture (or technocomplex) in north-central Europe during the Younger Dryas, the last spell of cold at the end of the Weichsel glacia ...

, tribes who hunted over vast territories and lived in lavvus on the tundra

In physical geography, tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. The term ''tundra'' comes through Russian (') from the Kildin Sámi word (') meaning "uplands", "treeless mo ...

. There was little forest in this region except for arctic white birch and rowan, but the taiga

Taiga (; rus, тайга́, p=tɐjˈɡa; relates to Mongolic and Turkic languages), generally referred to in North America as a boreal forest or snow forest, is a biome characterized by coniferous forests consisting mostly of pines, spruces ...

slowly appeared.

Mesolithic

From c. 9,000 to 6,000 B.P. (Middle to Late Mesolithic), Scandinavia was populated by mobile or semi-sedentary groups about whom little is known. They subsisted by hunting, fishing and gathering. Approximately 200 burial sites have been investigated in the region from this period of 3,000 years. In the 7th millennium BC, when the reindeer and their hunters had moved for northern Scandinavia, forests had been established in the land. The Maglemosian culture lived in Denmark and southern Sweden. To the north, in Norway and most of southern Sweden, lived the Fosna-Hensbacka culture, who lived mostly along the edge of the forest. The northern hunter/gatherers followed the herds and the salmon runs, moving south during the winters, moving north again during the summers. These early peoples followed cultural traditions similar to those practised throughout other regions in the far north – areas including modern Finland, Russia, and across the Bering Strait into the northernmost strip of North America. During the 6th millennium BC, southern Scandinavia was covered intemperate broadleaf and mixed forests

Temperate broadleaf and mixed forest is a temperate climate terrestrial habitat type defined by the World Wide Fund for Nature, with broadleaf tree ecoregions, and with conifer and broadleaf tree mixed coniferous forest ecoregions.

These f ...

. Fauna included aurochs

The aurochs (''Bos primigenius'') ( or ) is an extinct cattle species, considered to be the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle. With a shoulder height of up to in bulls and in cows, it was one of the largest herbivores in the Holocene ...

, wisent, moose

The moose (in North America) or elk (in Eurasia) (''Alces alces'') is a member of the New World deer subfamily and is the only species in the genus ''Alces''. It is the largest and heaviest extant species in the deer family. Most adult ma ...

and red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or hart, and a female is called a hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Iran, and parts of wes ...

. The Kongemose culture was dominant in this time period. They hunted seals and fished in the rich waters. North of the Kongemose people lived other hunter-gatherers in most of southern Norway and Sweden called the Nøstvet and Lihult cultures, descendants of the Fosna and Hensbacka cultures. Near the end of the 6th millennium BC, the Kongemose culture was replaced by the Ertebølle culture in the south.

Neolithic

During the 5th millennium BC, the Ertebølle people learned pottery from neighbouring tribes in the south, who had begun to cultivate the land and keep animals. They too started to cultivate the land, and by 3000 BC they became part of themegalith

A megalith is a large stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. There are over 35,000 in Europe alone, located widely from Sweden to the Mediterranean sea.

The ...

ic Funnelbeaker culture. During the 4th millennium BC, these Funnelbeaker tribes expanded into Sweden up to Uppland

Uppland () is a historical province or ' on the eastern coast of Sweden, just north of Stockholm, the capital. It borders Södermanland, Västmanland and Gästrikland. It is also bounded by lake Mälaren and the Baltic Sea. On the small un ...

. The Nøstvet and Lihult tribes learnt new technology from the advancing farmers (but not agriculture) and became the Pitted Ware cultures towards the end of the 4th millennium BC. These Pitted Ware tribes halted the advance of the farmers and pushed them south into southwestern Sweden, but some say that the farmers were not killed or chased away, but that they voluntarily joined the Pitted Ware culture and became part of them. At least one settlement appears to be mixed, the Alvastra pile-dwelling.

It is not known what language these early Scandinavians spoke, but towards the end of the 3rd millennium BC, they were overrun by new tribes who many scholars think spoke Proto-Indo-European

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is the reconstructed common ancestor of the Indo-European language family. Its proposed features have been derived by linguistic reconstruction from documented Indo-European languages. No direct record of Proto-Indo- ...

, the Battle-Axe culture

The Battle Axe culture, also called Boat Axe culture, is a Chalcolithic culture that flourished in the coastal areas of the south of the Scandinavian Peninsula and southwest Finland, from circa 2800 BC to circa 2300 BC.

The Battle Axe culture ...

. This new people advanced up to Uppland and the Oslofjord

The Oslofjord (, ; en, Oslo Fjord) is an inlet in the south-east of Norway, stretching from an imaginary line between the and lighthouses and down to in the south to Oslo in the north. It is part of the Skagerrak strait, connecting the Nor ...

, and they probably provided the language that was the ancestor of the modern Scandinavian languages. They were cattle herders, and with them most of southern Scandinavia entered the Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

. The transmission of metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the sci ...

to southern Scandinavia coincided with the introduction of long barrow

Long barrows are a style of monument constructed across Western Europe in the fifth and fourth millennia BCE, during the Early Neolithic period. Typically constructed from earth and either timber or stone, those using the latter material repre ...

s, causewayed enclosures, two-aisled houses, and certain types of artefacts, and seems to have enabled the establishment of a fully Neolithic society.

Nordic Bronze Age

Even though Scandinavians joined the European

Even though Scandinavians joined the European Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

cultures fairly late through trade, Scandinavian sites present rich and well-preserved objects made of wool, wood and imported Central European bronze and gold. During this period Scandinavia gave rise to the first known advanced civilization in this area following the Nordic Stone Age. The Scandinavians adopted many central European and Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

symbols at the same time that they created new styles and objects. Mycenaean Greece, the Villanovan Culture

The Villanovan culture (c. 900–700 BC), regarded as the earliest phase of the Etruscan civilization, was the earliest Iron Age culture of Italy. It directly followed the Bronze Age Proto-Villanovan culture which branched off from the Urnfie ...

, Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

and Ancient Egypt have all been identified as possible sources of influence in Scandinavian artwork from this period. The foreign influence is believed to originate with amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In M ...

trade, and amber found in Mycenaean graves from this period originates from the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and fr ...

. Several petroglyphs depict ships, and the large stone formations known as stone ships indicate that shipping played an important role in the culture. Several petroglyphs depict ships which could possibly be Mediterranean.

From this period there are many mounds and fields of petroglyphs

A petroglyph is an image created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading, as a form of rock art. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as "carving", "engraving", or other description ...

, but their signification is long since lost. There are also numerous artifacts of bronze and gold. The rather crude appearance of the petroglyphs compared to the bronze works have given rise to the theory that they were produced by different cultures or different social groups. No written language existed in the Nordic countries during the Bronze Age.

The Nordic Bronze Age was characterized by a warm climate (which is compared to that of the Mediterranean), which permitted a relatively dense population, but it ended with a climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to ...

consisting of deteriorating, wetter and colder climate (sometimes believed to have given rise to the legend of the Fimbulwinter) and it seems very likely that the climate pushed the Germanic tribes southwards into continental Europe. During this time there was Scandinavian influence in Eastern Europe. A thousand years later, the numerous East Germanic tribes that claimed Scandinavian origins ( Burgundians, Goths

The Goths ( got, 𐌲𐌿𐍄𐌸𐌹𐌿𐌳𐌰, translit=''Gutþiuda''; la, Gothi, grc-gre, Γότθοι, Gótthoi) were a Germanic people who played a major role in the fall of the Western Roman Empire and the emergence of medieval Euro ...

and Heruls), as did the Lombards

The Lombards () or Langobards ( la, Langobardi) were a Germanic people who ruled most of the Italian Peninsula from 568 to 774.

The medieval Lombard historian Paul the Deacon wrote in the '' History of the Lombards'' (written between 787 an ...

, rendered Scandinavia (Scandza

Scandza was described as a "great island" by Gothic-Byzantine historian Jordanes in his work ''Getica''. The island was located in the Arctic regions of the sea that surrounded the world. The location is usually identified with Scandinavia.

Jor ...

) the name "womb of nations" in Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') a ...

' ''Getica

''De origine actibusque Getarum'' (''The Origin and Deeds of the Getae oths'), commonly abbreviated ''Getica'', written in Late Latin by Jordanes in or shortly after 551 AD, claims to be a summary of a voluminous account by Cassiodorus of the ...

''.

Pre-Roman Iron Age

The Nordic Bronze Age ended with a deteriorating, colder and wetter climate. This period is known for being poor in archaeological finds. This is also the period when the Germanic tribes became known to the Mediterranean world and the Romans. In 113–101 BC two Germanic tribes originating from Jutland,Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. 'The Celts: A History'. Boydell Press, 2003. , . Length: 297 pages. Page 131 in modern-day Denmark, attacked the Roman Republic in what is today known as theCimbrian War

The Cimbrian or Cimbric War (113–101 BC) was fought between the Roman Republic and the Germanic and Celtic tribes of the Cimbri and the Teutons, Ambrones and Tigurini, who migrated from the Jutland peninsula into Roman controlled territor ...

. These two tribes, the Cimbri

The Cimbri (Greek Κίμβροι, ''Kímbroi''; Latin ''Cimbri'') were an ancient tribe in Europe. Ancient authors described them variously as a Celtic people (or Gaulish), Germanic people, or even Cimmerian. Several ancient sources indicate ...

and the Teutons, initially inflicted the heaviest losses that Rome had suffered since the Second Punic War. The Cimbri and the Teutons were eventually defeated by the Roman legions.

Initially iron was valuable and was used for decoration. The oldest objects were needles, but swords and sickles are found as well. Bronze continued to be used during the whole period but was mostly used for decoration. The traditions were a continuity from the Nordic Bronze Age, but there were strong influences from the Hallstatt culture

The Hallstatt culture was the predominant Western and Central European culture of Late Bronze Age (Hallstatt A, Hallstatt B) from the 12th to 8th centuries BC and Early Iron Age Europe (Hallstatt C, Hallstatt D) from the 8th to 6th centuries ...

in Central Europe. They continued with the Urnfield culture tradition of burning corpses and placing the remains in urns. During the last centuries, influences from the Central European La Tène culture

The La Tène culture (; ) was a European Iron Age culture. It developed and flourished during the late Iron Age (from about 450 BC to the Roman conquest in the 1st century BC), succeeding the early Iron Age Hallstatt culture without any defi ...

spread to Scandinavia from northwestern Germany, and there are finds from this period from all the provinces of southern Scandinavia. From this time archaeologists have found swords, shieldbosses, spearheads, scissors, sickles, pincers, knives, needles, buckles, kettles, etc. Bronze continued to be used for torque

In physics and mechanics, torque is the rotational equivalent of linear force. It is also referred to as the moment of force (also abbreviated to moment). It represents the capability of a force to produce change in the rotational motion of t ...

s and kettles, the style of which were a continuity from the Bronze Age. One of the most prominent finds is the Dejbjerg wagon from Jutland

Jutland ( da, Jylland ; german: Jütland ; ang, Ēota land ), known anciently as the Cimbric or Cimbrian Peninsula ( la, Cimbricus Chersonesus; da, den Kimbriske Halvø, links=no or ; german: Kimbrische Halbinsel, links=no), is a peninsula of ...

, a four-wheeled wagon of wood with bronze parts.

Roman Iron Age

While many Germanic tribes sustained continued contact with the culture and military presence of theRoman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, much of Scandinavia existed on the most extreme periphery of the Latin world. With the exception of the passing references to the Swedes ( Suiones) and the Geats

The Geats ( ; ang, gēatas ; non, gautar ; sv, götar ), sometimes called ''Goths'', were a large North Germanic tribe who inhabited ("land of the Geats") in modern southern Sweden from antiquity until the late Middle Ages. They are one of t ...

(Gautoi), much of Scandinavia remained unrecorded by Roman authors.

In Scandinavia, there was a great import of goods, such as coin

A coin is a small, flat (usually depending on the country or value), round piece of metal or plastic used primarily as a medium of exchange or legal tender. They are standardized in weight, and produced in large quantities at a mint in orde ...

s (more than 7,000), vessels, bronze images, glass beakers, enameled buckles, weapons, etc. Moreover, the style of metal objects and clay vessels was markedly Roman. Some objects appeared for the first time, such as shears and pawns.

There are also many bog bodies from this time in Denmark, Schleswig and southern Sweden. Together with the bodies, there are weapons, household wares and clothes of wool. Great ships made for rowing have been found from the 4th century in Nydam mosse

The Nydam Mose, also known as Nydam Bog, is an archaeological site located at Øster Sottrup, a town located in Sundeved, eight kilometres from Sønderborg, Denmark.

History

In the Nordic Iron Age, Iron Age, the site of the bog was a sacred plac ...

in Schleswig. Many were buried without burning, but the burning tradition later regained its popularity.

Through the 5th century and 6th century, gold and silver became more common. Much of this can be attributed to the ransacking of the Roman Empire by Germanic tribes, from which many Scandinavians returned with gold and silver.

Germanic Iron Age

The period succeeding the fall of the Roman Empire is known as theGermanic Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, northern Germany, Poland and the Netherlands.

The region ...

, and it is divided into the early Germanic Iron and the late Germanic Iron Age, which in Sweden is known as the Vendel Age, with rich burials in the basin of Lake Mälaren. The early Germanic Iron Age is the period when the Danes

Danes ( da, danskere, ) are a North Germanic ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

Danes generally regard ...

appear in history, and according to Jordanes

Jordanes (), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat widely believed to be of Gothic descent who became a historian later in life. Late in life he wrote two works, one on Roman history ('' Romana'') a ...

, they were of the same stock as the Swedes (''suehans'', ''suetidi'') and had replaced the Heruls.

During the fall of the Roman empire, there was an abundance of gold that flowed into Scandinavia, and there are excellent works in gold from this period. Gold was used to make scabbard

A scabbard is a sheath for holding a sword, knife, or other large blade. As well, rifles may be stored in a scabbard by horse riders. Military cavalry and cowboys had scabbards for their saddle ring carbine rifles and lever-action rifles on ...

mountings and bracteates; notable examples are the Golden horns of Gallehus.

After the Roman Empire had disappeared, gold became scarce and Scandinavians began to make objects of gilded bronze, with decorations of interlacing animals in Scandinavian style. The early Germanic Iron Age decorations show animals that are rather faithful anatomically, but in the late Germanic Iron Age they evolve into intricate shapes with interlacing and interwoven limbs that are well known from the Viking Age

The Viking Age () was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonizing, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. It followed the Migration Period

The ...

.

In February 2020, Secrets of the Ice Program researchers discovered a 1,500-year-old Viking arrowhead dating back to the Germanic Iron Age and locked in a glacier in southern Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and t ...

caused by the climate change in the Jotunheimen

Jotunheimen (; "the home of the Jötunn") is a mountainous area of roughly in southern Norway and is part of the long range known as the Scandinavian Mountains. The 29 highest mountains in Norway are all located in the Jotunheimen mountains, i ...

Mountains. The arrowhead made of iron was revealed with its cracked wooden shaft and a feather, is 17 cm long and weighs just 28 grams.

Sami peoples

Since prehistoric times, the Sami people of Arctic Europe have lived and worked in an area that stretches over the northern parts of the regions now known as Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola Peninsula. They have inhabited the northern arctic and sub-arctic regions of Fenno-Scandinavia and Russia for at least 5,000 years. The Sami are counted among the Arctic peoples and are members of circumpolar groups such as the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat.

Petroglyphs and archeological findings such as settlements dating from about 10,000 B.C. can be found in the traditional lands of the Sami. These hunters and gatherers of the late Paleolithic and early Mesolithic were named

Since prehistoric times, the Sami people of Arctic Europe have lived and worked in an area that stretches over the northern parts of the regions now known as Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Russian Kola Peninsula. They have inhabited the northern arctic and sub-arctic regions of Fenno-Scandinavia and Russia for at least 5,000 years. The Sami are counted among the Arctic peoples and are members of circumpolar groups such as the Arctic Council Indigenous Peoples' Secretariat.

Petroglyphs and archeological findings such as settlements dating from about 10,000 B.C. can be found in the traditional lands of the Sami. These hunters and gatherers of the late Paleolithic and early Mesolithic were named Komsa

The Komsa culture (''Komsakulturen'') was a Mesolithic culture of hunter-gatherers that existed from around 10,000 BC in Northern Norway.

The culture is named after Mount Komsa in the community of Alta, Finnmark, where the remains of the cult ...

by the researchers as what they identified themselves as is unknown.

The Sami have been recognized as an indigenous people in Norway since 1990 according to ILO convention 169, and hence, according to international law, the Sami people in Norway are entitled special protection and rights.

Viking Age

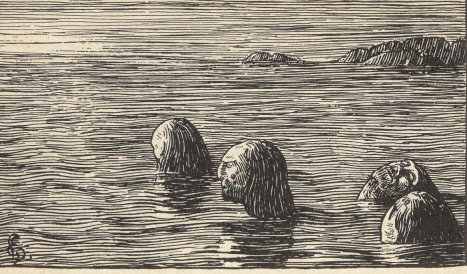

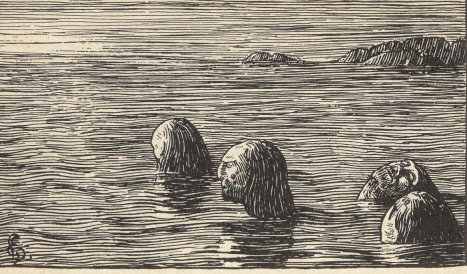

During the Viking Age, the

During the Viking Age, the Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

(Scandinavian warriors and traders) raided, colonized and explored large parts of Europe, the Middle East, northern Africa, as far west as Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

.

The beginning of the Viking Age is commonly given as 793, when Vikings pillaged the important British island monastery of Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also called Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th century AD; it was an important ...

, and its end is marked by the unsuccessful invasion of England attempted by Harald Hårdråde

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' (; modern no, Hardråde, roughly translated as "stern counsel" or "hard ruler") in the sagas, was King of Norway from 1046 t ...

in 1066 and the Norman conquest

The Norman Conquest (or the Conquest) was the 11th-century invasion and occupation of England by an army made up of thousands of Norman, Breton, Flemish, and French troops, all led by the Duke of Normandy, later styled William the Conq ...

.

Age of settlement

The age of settlement began around 800 AD . The Vikings invaded and eventually settled in Scotland , England,

The age of settlement began around 800 AD . The Vikings invaded and eventually settled in Scotland , England, Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

, the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic archipelago, island group and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotlan ...

, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

, Ireland , Livonia

Livonia ( liv, Līvõmō, et, Liivimaa, fi, Liivinmaa, German and Scandinavian languages: ', archaic German: ''Liefland'', nl, Lijfland, Latvian and lt, Livonija, pl, Inflanty, archaic English: ''Livland'', ''Liwlandia''; russian: Ли ...

, Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, the Shetland Islands, Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, Rus' and Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland ( non, Vínland ᚠᛁᚾᛚᛅᚾᛏ) was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and Jo ...

, on what is now known as the Island of Newfoundland

Newfoundland (, ; french: link=no, Terre-Neuve, ; ) is a large island off the east coast of the North American mainland and the most populous part of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. It has 29 percent of the province's land ...

. Swedish settlers were mostly present in Rus, Livonia, and other eastern regions while the Norwegians and the Danish were primarily concentrated in western and northern Europe . These eastern-traveling Scandinavian migrants were eventually known as Varangians

The Varangians (; non, Væringjar; gkm, Βάραγγοι, ''Várangoi'';Varangian

" Online Etymo ...

(''væringjar'', meaning "sworn men"),and according to the oldest Slavic sources , these varangians founded " Online Etymo ...

Kievan Rus

Kievan Rusʹ, also known as Kyivan Rusʹ ( orv, , Rusĭ, or , , ; Old Norse: ''Garðaríki''), was a state in Eastern and Northern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical Atlas o ...

, the major East European state prior to the Mongol

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal member ...

invasions. The western-led warriors, eventually known as Vikings, left great cultural marks on regions such as French Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, England, and Ireland, where the city of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 ...

was founded by Viking invaders. Iceland first became colonized in the late 9th century .

Relation with the Baltic Slavs

Before and during this age, the Norsemen significantly intermixed with the Slavs. The Slavic and Viking cultures influenced each other: Slavic and Viking tribes were "closely linked, fighting one another, intermixing and trading". In the Middle Ages, a significant amount of ware was transferred from Slavic areas to Scandinavia, and Denmark was "a melting pot of Slavic and Scandinavian elements". The presence of Slavs in Scandinavia is "more significant than previously thought" although "the Slavs and their interaction with Scandinavia have not been adequately investigated". A grave of a warrior-woman dating to the 10th century in Denmark was long thought to belong to a Viking. However, new analyses revealed that the woman was a Slav from present-day Poland. The first king of the Swedes,Eric

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, or Eirik is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-Norse ''* a ...

, was married to Gunhild, of the Polish House of Piast. Likewise, his son, Olof, fell in love with Edla, a Slavic woman, and took her as his '' frilla'' (concubine). She bore him a son and a daughter: Emund the Old, King of Sweden, and Astrid, Queen of Norway. Cnut the Great

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knútr inn ríki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway ...

, King of Denmark, England and Norway, was the son of a daughter of Mieszko I of Poland, possibly the former Polish queen of Sweden, wife of Eric.

Christianization

Viking religious beliefs were heavily connected to

Viking religious beliefs were heavily connected to Norse mythology

Norse, Nordic, or Scandinavian mythology is the body of myths belonging to the North Germanic peoples, stemming from Old Norse religion and continuing after the Christianization of Scandinavia, and into the Nordic folklore of the modern peri ...

. Vikings placed heavy emphasis on battle, honor and focused on the idea of Valhalla, a mythical home with the gods for fallen warriors. Another Norse tradition was that of blood feuds, which particularly had devastated Iceland.

Christianity in Scandinavia came later than most parts of Europe. In Denmark Harald Bluetooth Christianized the country around 980. The process of Christianization began in Norway during the reigns of Olaf Tryggvason (reigned 995 AD–c.1000 AD) and Olaf II Haraldsson

Olaf II Haraldsson ( – 29 July 1030), later known as Saint Olaf (and traditionally as St. Olave), was King of Norway from 1015 to 1028. Son of Harald Grenske, a petty king in Vestfold, Norway, he was posthumously given the title ''Rex Perpet ...

(reigned 1015 AD–1030 AD). Olaf and Olaf II had been baptized voluntarily outside of Norway. Olaf II managed to bring English clergy to his country. Norway's conversion from the Norse religion

Old Norse religion, also known as Norse paganism, is the most common name for a branch of Germanic religion which developed during the Proto-Norse period, when the North Germanic peoples separated into a distinct branch of the Germanic peop ...

to Christianity was mostly the result of English missionaries. As a result of the adoption of Christianity by the monarchy and eventually the entirety of the country, traditional shaman

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a Spirit world (Spiritualism), spirit world through Altered state of consciousness, altered states of consciousness, such as tranc ...

istic practices were marginalized and eventually persecuted. Völvas, practitioners of seid, a Scandinavian pre-Christian tradition, were executed or exiled under newly Christianized governments in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

The Icelandic Commonwealth

The Icelandic Commonwealth, also known as the Icelandic Free State, was the political unit existing in Iceland between the establishment of the Althing in 930 and the pledge of fealty to the Norwegian king with the Old Covenant in 1262. With th ...

adopted Christianity in 1000 AD, after pressure from Norway. The '' Goði''-chieftain Þorgeirr Ljósvetningagoði was instrumental in bringing this about. By formulating a law that made Christianity the official religion, but also that religious practice in the private sphere was outside of the law, he managed to stave off the threat from Norway, limiting the feuds and avoiding an religiously motivated civil war.

Sweden required a little more time to transition to Christianity, with indigenous religious practices commonly held in localized communities well until the end of the eleventh century. A brief Swedish civil war ensued in 1066 primarily reflecting the divisions between practitioners of indigenous religions and advocates of Christianity; by the mid-twelfth century, the Christian faction appeared to have triumphed; the once resistant center of Uppsala

Uppsala (, or all ending in , ; archaically spelled ''Upsala'') is the county seat of Uppsala County and the List of urban areas in Sweden by population, fourth-largest city in Sweden, after Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö. It had 177,074 inha ...

became the seat of the Swedish Archbishop in 1164. The Christianization of Scandinavia occurred nearly simultaneously with the end of the Viking era. The adoption of Christianity is believed to have aided in the absorption of Viking communities into the greater religious and cultural framework of the European continent.

Middle Ages (1100–1600)

Union

The Kalmar Union (Danish/Norwegian/Swedish: ''Kalmarunionen'') was a series of

The Kalmar Union (Danish/Norwegian/Swedish: ''Kalmarunionen'') was a series of personal union

A personal union is the combination of two or more State (polity), states that have the same monarch while their boundaries, laws, and interests remain distinct. A real union, by contrast, would involve the constituent states being to some e ...

s (1397–1520) that united the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway and Sweden under a single monarch. The countries had given up their sovereignty but not their independence, and diverging interests (especially Swedish dissatisfaction over the Danish and Holstein

Holstein (; nds, label= Northern Low Saxon, Holsteen; da, Holsten; Latin and historical en, Holsatia, italic=yes) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost state of Germ ...

ish dominance) gave rise to a conflict that would hamper it from the 1430s until its final dissolution in 1523.

The Kalmar War in 1611–1613 was the last serious (although possibly unrealistic) attempt by a Danish King ( Christian IV) to re-create the Kalmar Union by force. However, The Kalmar War ended with a minor Danish victory and not the total defeat of the Swedes. No more Danish attempts would be made to re-create the Kalmar Union following this war.

Reformation

TheProtestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

came to Scandinavia in the 1530s, and Scandinavia soon became one of the heartlands of Lutheranism

Lutheranism is one of the largest branches of Protestantism, identifying primarily with the theology of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German monk and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practice of the Cathol ...

. Catholicism almost completely vanished in Scandinavia, except for a small population in Denmark.

17th century

Thirty Years War

TheThirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War was one of the longest and most destructive conflicts in European history, lasting from 1618 to 1648. Fought primarily in Central Europe, an estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died as a result of battl ...

was a conflict fought between the years 1618 and 1648, principally in the Central European territory of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

but also involving most of the major continental powers. Although it was from its outset a religious conflict between Protestants

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and Catholics, the self-preservation of the Habsburg dynasty was also a central motive. The Danes and then Swedes intervened at various points to protect their interests.

The Danish intervention began when Christian IV (1577–1648) the King of Denmark-Norway, himself a Lutheran, helped the German Protestants by leading an army against the Holy Roman Empire, fearing that Denmark's sovereignty as a Protestant nation was being threatened. The period began in 1625 and lasted until 1629. Christian IV had profited greatly from his policies in northern Germany (Hamburg had been forced to accept Danish sovereignty in 1621, and in 1623 the Danish heir apparent was made Administrator of the Prince-Bishopric of Verden. In 1635 he became Administrator of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen too.) As an administrator, Christian IV had done remarkably well, obtaining for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe, paid for by the

The Danish intervention began when Christian IV (1577–1648) the King of Denmark-Norway, himself a Lutheran, helped the German Protestants by leading an army against the Holy Roman Empire, fearing that Denmark's sovereignty as a Protestant nation was being threatened. The period began in 1625 and lasted until 1629. Christian IV had profited greatly from his policies in northern Germany (Hamburg had been forced to accept Danish sovereignty in 1621, and in 1623 the Danish heir apparent was made Administrator of the Prince-Bishopric of Verden. In 1635 he became Administrator of the Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen too.) As an administrator, Christian IV had done remarkably well, obtaining for his kingdom a level of stability and wealth that was virtually unmatched elsewhere in Europe, paid for by the Øresund

Øresund or Öresund (, ; da, Øresund ; sv, Öresund ), commonly known in English as the Sound, is a strait which forms the Danish–Swedish border, separating Zealand (Denmark) from Scania (Sweden). The strait has a length of ; its width ...

toll and extensive war reparations from Sweden. It also helped that the French regent Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duke of Richelieu (; 9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a French clergyman and statesman. He was also known as ''l'Éminence rouge'', or "the Red Eminence", a term derived from the ...

was willing to pay for a Danish incursion into Germany. Christian IV invaded at the head of a mercenary army of 20,000 men, but the Danish forces were severely beaten, and Christian IV had to sign an ignominious defeat, the first in a series of military setbacks to weaken his kingdom.

The Swedish intervention began in 1630 and lasted until 1635. Some within Ferdinand II's court believed that Wallenstein wanted to take control of the German princes and thus gain influence over the emperor. Ferdinand II dismissed Wallenstein in 1630. He later recalled him after Gustavus Adolphus

Gustavus Adolphus (9 December N.S 19 December">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 19 December15946 November Old Style and New Style dates">N.S 16 November] 1632), also known in English as G ...

attacked the empire and prevailed in a number of significant battles.

Gustavus Adolphus, like Christian IV before him, came to aid the German Lutherans to forestall Catholic aggression against their homeland and to obtain economic influence in the German states around the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and fr ...

. Also like Christian IV, Gustavus Adolphus was subsidized by Richelieu, the Chief Minister of King Louis XIII of France, and by the Dutch. From 1630 to 1634, they drove the Catholic forces back and regained much of the occupied Protestant lands.

Rise of Sweden and the Swedish Empire

The Swedish rise to power began under the rule of Charles IX. During the Ingrian War Sweden expanded its territories eastward. Several other wars with Poland, Denmark-Norway, and German countries enabled further Swedish expansion, although there were some setbacks such as the Kalmar War. Sweden began consolidating its empire. Several other wars followed soon after including the Northern Wars and the

The Swedish rise to power began under the rule of Charles IX. During the Ingrian War Sweden expanded its territories eastward. Several other wars with Poland, Denmark-Norway, and German countries enabled further Swedish expansion, although there were some setbacks such as the Kalmar War. Sweden began consolidating its empire. Several other wars followed soon after including the Northern Wars and the Scanian War

The Scanian War ( da, Skånske Krig, , sv, Skånska kriget, german: Schonischer Krieg) was a part of the Northern Wars involving the union of Denmark–Norway, Brandenburg and Sweden. It was fought from 1675 to 1679 mainly on Scanian soil, ...

. Denmark suffered many defeats during this period. Finally under the rule of Charles XI the empire was consolidated under a semi-absolute monarchy.

18th century

Great Northern War

TheGreat Northern War

The Great Northern War (1700–1721) was a conflict in which a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the anti-Swed ...

was fought between a coalition of Russia, Denmark-Norway and Saxony

Saxony (german: Sachsen ; Upper Saxon: ''Saggsn''; hsb, Sakska), officially the Free State of Saxony (german: Freistaat Sachsen, links=no ; Upper Saxon: ''Freischdaad Saggsn''; hsb, Swobodny stat Sakska, links=no), is a landlocked state of ...

-Poland (from 1715 also Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an ...

and Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

) on one side and Sweden on the other side from 1700 to 1721. It started by a coordinated attack on Sweden by the coalition in 1700 and ended 1721 with the conclusion of the Treaty of Nystad

The Treaty of Nystad (russian: Ништадтский мир; fi, Uudenkaupungin rauha; sv, Freden i Nystad; et, Uusikaupunki rahu) was the last peace treaty of the Great Northern War of 1700–1721. It was concluded between the Tsardom of ...

and the Stockholm treaties. As a result of the war, Russia supplanted Sweden as the dominant power on the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden and the North and Central European Plain.

The sea stretches from 53°N to 66°N latitude and fr ...

and became a major player in European politics.

Colonialism

Both Sweden and Denmark-Norway maintained a number of colonies outside Scandinavia starting in the 17th century lasting until the 20th century.Greenland

Greenland ( kl, Kalaallit Nunaat, ; da, Grønland, ) is an island country in North America that is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. It is located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, east of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Greenland is ...

, Iceland

Iceland ( is, Ísland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavík, which (along with its ...

and The Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic were Norwegian dependencies that were incorporated into the united kingdom of Denmark-Norway. In the Caribbean, Denmark started a colony on St Thomas in 1671, St John

Saint John or St. John usually refers to John the Baptist, but also, sometimes, to John the Apostle.

Saint John or St. John may also refer to:

People

* John the Baptist (0s BC–30s AD), preacher, ascetic, and baptizer of Jesus Christ

* John t ...

in 1718, and purchased Saint Croix

Saint Croix; nl, Sint-Kruis; french: link=no, Sainte-Croix; Danish and no, Sankt Croix, Taino: ''Ay Ay'' ( ) is an island in the Caribbean Sea, and a county and constituent district of the United States Virgin Islands (USVI), an unincor ...

from France in 1733. Denmark also maintained colonies in India, Tranquebar

Tharangambadi (), formerly Tranquebar ( da, Trankebar, ), is a town in the Mayiladuthurai district of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu on the Coromandel Coast. It lies north of Karaikal, near the mouth of a distributary named Uppanar of the ...

and Frederiksnagore. The Danish East India Company

The Danish East India Company ( da, Ostindisk Kompagni) refers to two separate Danish-Norwegian chartered companies. The first company operated between 1616 and 1650. The second company existed between 1670 and 1729, however, in 1730 it was re-f ...

operated out of Tranquebar

Tharangambadi (), formerly Tranquebar ( da, Trankebar, ), is a town in the Mayiladuthurai district of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu on the Coromandel Coast. It lies north of Karaikal, near the mouth of a distributary named Uppanar of the ...

. Sweden also chartered a Swedish East India Company. During its heyday, the Danish and Swedish East India Companies imported more tea than the British East India Company – and smuggled 90% of it into Britain where it could be sold at a huge profit. Both East India Companies folded over the course of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

. Sweden had the short lived colony New Sweden

New Sweden ( sv, Nya Sverige) was a Swedish colony along the lower reaches of the Delaware River in what is now the United States from 1638 to 1655, established during the Thirty Years' War when Sweden was a great military power. New Sweden fo ...

in Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacen ...

in North America during the 1630s and later acquired the islands of Saint-Barthélemy (1785–1878) and Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe (; ; gcf, label=Antillean Creole, Gwadloup, ) is an archipelago and overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands— Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galante, La Désirade, and the ...

in the Caribbean.

19th century

Napoleonic Wars

battle of Copenhagen (1807)

The Second Battle of Copenhagen (or the Bombardment of Copenhagen) (16 August – 7 September 1807) was a British bombardment of the Danish capital, Copenhagen, in order to capture or destroy the Dano-Norwegian fleet during the Napoleonic War ...

. Most of the Danish fleet was captured following the Second Battle of Copenhagen in 1807. The bombardment of Copenhagen led to an alliance with France and outright war with Britain, whose navy blockaded Denmark-Norway and severely impeded communication between the two kingdoms and caused a famine in Norway. Sweden, allied with Britain at the time, seized the opportunity to invade Norway in 1807 but was beaten back. The war with Britain was fought at sea in a series of battles, Battle of Zealand Point, Battle of Lyngør, and Battle of Anholt, by the remnants of the Danish fleet in the ensuing years, as the Danes tried to break the British blockade, in what became known as the Gunboat War

The Gunboat War (, ; 1807–1814) was a naval conflict between Denmark–Norway and the British during the Napoleonic Wars. The war's name is derived from the Danish tactic of employing small gunboats against the materially superior Royal N ...

. After the war, Denmark was forced to cede Heligoland to Britain.

Sweden joined the Third Coalition against Napoleon in 1805, but the coalition fell apart after the peace at Tilsit in 1807, forcing Russia to become the ally of France. Russia invaded Finland in 1808 and forced Sweden to cede that province at the peace of Fredrikshamn in 1809. The inept government of King Gustav IV Adolf led to his deposition and banishment. A new constitution was introduced, and his uncle Charles XIII was enthroned. Since he was childless, Sweden chose as his successor the commander in chief of the Norwegian army, Prince Christian August of Augustenborg. However, his sudden death in 1810 forced the Swedes to look for another candidate, and once more they chose an enemy officer. Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte

sv, Karl Johan Baptist Julius

, spouse =

, issue = Oscar I of Sweden

, house = Bernadotte

, father = Henri Bernadotte

, mother = Jeanne de Saint-Jean

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Pau, ...

, Marshal of France

Marshal of France (french: Maréchal de France, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished ( ...

, would be named the next king. Baron Karl Otto Mörner, an obscure member of the Diet, was the one who initially extended the offer of the Swedish crown to the young soldier. Bernadotte was originally one of Napoleon's eighteen Marshals.

Sweden decided to join the alliance against France in 1813 and was promised Norway as a reward. After the battle of Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as ...

in October 1813, Bernadotte abandoned the pursuit of Napoleon and marched against Denmark, where he forced the king of Denmark-Norway to conclude the Treaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel ( da, Kieltraktaten) or Peace of Kiel (Swedish and no, Kielfreden or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the ...

on 14 January 1814. Norway was ceded to the king of Sweden, but Denmark retained the Norwegian Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

possessions of the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic archipelago, island group and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotlan ...

, Iceland, and Greenland. However, the treaty of Kiel never came into force. Norway declared its independence, adopted a liberal constitution, and elected Prince Christian Frederik as king. After a short war with Sweden, Norway had to concede to a personal union with Sweden at the Convention of Moss

The Convention of Moss (''Mossekonvensjonen'') was a ceasefire agreement signed on 14 August 1814 between the King of Sweden and the Norwegian government. It followed the Swedish-Norwegian War due to Norway's claim to sovereignty. It also bec ...

. King Christian Frederik abdicated and left for Denmark in October, and the Norwegian Storting

The Storting ( no, Stortinget ) (lit. the Great Thing) is the supreme legislature of Norway, established in 1814 by the Constitution of Norway. It is located in Oslo. The unicameral parliament has 169 members and is elected every four years ...

(parliament) elected the Swedish king as King of Norway, after having enacted such amendments to the constitution as were necessary to allow for the union with Sweden.

Sweden and Norway

On 14 January 1814, at theTreaty of Kiel

The Treaty of Kiel ( da, Kieltraktaten) or Peace of Kiel (Swedish and no, Kielfreden or ') was concluded between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and the Kingdom of Sweden on one side and the Kingdoms of Denmark and Norway on the ...

, the king of Denmark-Norway ceded Norway to the king of Sweden. The terms of the treaty provoked widespread opposition in Norway. The Norwegian vice-roy and heir to the throne of Denmark-Norway, Christian Frederik took the lead in a national uprising, assumed the title of regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

, and convened a constitutional assembly at Eidsvoll

Eidsvoll (; sometimes written as ''Eidsvold'') is a municipality in Akershus in Viken county, Norway. It is part of the Romerike traditional region. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Sundet.

General information ...

. On 17 May 1814 the Constitution of Norway

nb, Kongeriket Norges Grunnlov

nn, Kongeriket Noregs Grunnlov

, jurisdiction = Kingdom of Norway

, date_created =10 April - 16 May 1814

, date_ratified =16 May 1814

, system =Constitutional monarchy

, ...

was signed by the assembly, and Christian Frederik was elected as king of independent Norway.

The Swedish king rejected the premise of an independent Norway and launched a military campaign on 27 July 1814, with an attack on the Hvaler

Hvaler is a municipality that is a group of islands in the southern part of Viken County, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the village of Skjærhalden, on the island of Kirkeøy. The only police station in the municip ...

islands and the city of Fredrikstad

Fredrikstad (; previously ''Frederiksstad''; literally "Fredrik's Town") is a city and municipality in Viken county, Norway. The administrative centre of the municipality is the city of Fredrikstad.

The city of Fredrikstad was founded in 1 ...

. The Swedish army was superior in numbers, was better equipped and trained, and was led by one of Napoleon's foremost generals, the newly elected Swedish crown prince, Jean Baptiste Bernadotte. Battles were short and decisively won by the Swedes. Armistice negotiations concluded on 14 August 1814.

In the peace negotiations, Christian Frederik agreed to relinquish claims to the Norwegian crown and return to Denmark if Sweden would accept the democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

Norwegian constitution and a loose personal union. On 4 November 1814, the Norwegian Parliament adopted the constitutional amendments required to enter a union with Sweden, and elected king Charles XIII as king of Norway.

Following growing dissatisfaction with the union in Norway, the parliament unanimously declared its dissolution on 7 June 1905. This unilateral action met with Swedish threats of war. A plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

on 13 August confirmed the parliamentary decision. Negotiations in Karlstad led to agreement with Sweden on 23 September and mutual demobilization. Both parliaments revoked the Act of Union 16 October, and the deposed king Oscar II of Sweden

Oscar II (Oscar Fredrik; 21 January 1829 – 8 December 1907) was King of Sweden from 1872 until his death in 1907 and King of Norway from 1872 to 1905.

Oscar was the son of King Oscar I and Josephine of Leuchtenberg, Queen Josephine. He inheri ...

renounced his claim to the Norwegian throne and recognized Norway as an independent kingdom on 26 October. The Norwegian parliament offered the vacant throne to Prince Carl of Denmark, who accepted after another plebiscite had confirmed the monarchy. He arrived in Norway on 25 November 1905, taking the name Haakon VII.

Finnish War

TheFinnish War

The Finnish War ( sv, Finska kriget, russian: Финляндская война, fi, Suomen sota) was fought between the Kingdom of Sweden and the Russian Empire from 21 February 1808 to 17 September 1809 as part of the Napoleonic Wars. As a res ...

was fought between Sweden and Russia from February 1808 to September 1809. As a result of the war, Finland which formed the eastern third of Sweden proper

Sweden proper ( sv, Egentliga Sverige) is a term used to distinguish those territories that were fully integrated into the Kingdom of Sweden, as opposed to the dominions and possessions of, or states in union with, Sweden. Only the estates of t ...

became the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland

The Grand Duchy of Finland ( fi, Suomen suuriruhtinaskunta; sv, Storfurstendömet Finland; russian: Великое княжество Финляндское, , all of which literally translate as Grand Principality of Finland) was the predecess ...

within Imperial Russia

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. T ...

. Finland remained as a part of Russian Empire until 1917 at which point it became independent. Another notable effect was the Swedish parliament's adoption of a new constitution and a new royal house, that of Bernadotte.

Industrialization

Industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econ ...

began in the mid 19th century in Scandinavia. In Denmark industrialization began in, and was confined to, Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( or .; da, København ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a proper population of around 815.000 in the last quarter of 2022; and some 1.370,000 in the urban area; and the wider Copenhagen metropolitan ar ...

until the 1890s, after which smaller towns began to grow rapidly. Denmark remained primarily agricultural until well into the 20th century, but agricultural processes were modernized and processing of dairy and meats became more important than the export of raw agricultural products.

Industrialization of Sweden

The industrialization of Sweden began during the second half of the nineteenth century. The industrial breakthrough occurred in the 1870s during the international boom period, and it carried on through the decades in response to the growing dema ...

experienced a boom during the First World War. The construction of a railway connecting southern Sweden and the northern mines was of primary importance.

Scandinavism

The modern use of the term Scandinavia rises from theScandinavist

Scandinavism ( da, skandinavisme; no, skandinavisme; sv, skandinavism), also called Scandinavianism or pan-Scandinavianism,First war of Schleswig (1848–1850), in which Sweden and Norway contributed with considerable military force, and the Second war of Schleswig (1864) when the Riksdag of the Estates denounced the King's promises of military support for Denmark.

The figure for Norway represents almost 80% of the national population in 1800. The most popular destinations in North America were Minnesota, Iowa, the Dakotas, Wisconsin, Michigan, the Canadian prairies and Ontario.

The Scandinavian Monetary Union was a monetary union formed by Sweden and Denmark on 5 May 1873, by fixing their currencies against the

The Scandinavian Monetary Union was a monetary union formed by Sweden and Denmark on 5 May 1873, by fixing their currencies against the

. The monetary union was one of the few tangible results of the Scandinavian political movement of the 19th century. The union provided fixed exchange rates and stability in monetary terms, but the member countries continued to issue their own separate currencies. Even if it was not initially foreseen, the perceived security led to a situation where the formally separate currencies were accepted on a basis of "as good as" the legal tender virtually throughout the entire area. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought an end to the monetary union. Sweden abandoned the tie to gold on 2 August 1914, and without a fixed exchange rate the free circulation came to an end.

Near the beginning of World War II in late 1939, both the Allies of World War II, Allies and the

Near the beginning of World War II in late 1939, both the Allies of World War II, Allies and the

online

* Barton, H. Arnold. ''Scandinavia in the Revolutionary Era 1760–1815'', University of Minnesota Press, 1986. . * Birch J. H. S. ''Denmark In History'' (1938

online

* * Clerc, Louis; Glover, Nikolas; Jordan, Paul, eds. ''Histories of Public Diplomacy and Nation Branding in the Nordic and Baltic Countries: Representing the Periphery'' (Leiden: Brill Nijhoff, 2015). 348 pp. ISBN 978- 90-04-30548-9

online review

* Derry, T.K. “Scandinavia” in C.W. Crawley, ed. ''The New Cambridge Modern History: IX. War and Peace in an age of upheaval 1793–1830'' (Cambridge University Press, 1965) pp 480–494

online

* Derry, T.K. ''A History of Scandinavia: Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland, Iceland''. (U of Minnesota Press, 1979. ). * Helle, Knut, ed. ''The Cambridge History of Scandinavia: Vol. 1'' (Cambridge University Press, 2003) * Hesmyr, Atle: ''Scandinavia in the Early Modern Era; From Peasant Revolts and Witch Hunts to Constitution Drafting Yeomen'' (Nisus Publications, 2015). * Hodgson, Antony. ''Scandinavian Music: Finland and Sweden.'' (1985). 224 pp. * Horn, David Bayne. ''Great Britain and Europe in the eighteenth century'' (1967) covers 1603–1702; pp 236–69. * Ingebritsen, Christine. ''Scandinavia in world politics'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 2006) * Jacobsen, Helge Seidelin. ''An outline history of Denmark'' (1986

online

* Jonas, Frank. ''Scandinavia and the Great Powers in the First World War'' (2019

online review

* Lindström, Peter, and Svante Norrhem. ''Flattering Alliances: Scandinavia, Diplomacy and the Austrian-French Balance of Power, 1648–1740'' (Nordic Academic Press, 2013). * Mathias, Peter, ed. '' Cambridge Economic History of Europe. Vol. 7: Industrial Economies. Capital, Labour and Enterprise. Part 1 Britain, France, Germany and Scandinavia'' (1978) * Milward, Alan S, and S. B. Saul, eds. ''The economic development of continental Europe: 1780–1870 '' (1973)

online

PP 467–536. * Moberg, Vilhelm, and Paul Britten Austin. ''A History of the Swedish People: Volume II: From Renaissance to Revolution'' (2005) * Nissen, Henrik S., ed. ''Scandinavia during the Second World War'' (Universitetsforlaget, 1983) * Olesen, Thorsten B., ed. ''The Cold War and the Nordic countries: Historiography at a crossroads'' (University Press of Southern Denmark, 2004). * * Price, T. Douglas. 2015.

'. Oxford University Press. *Salmon, Patrick. ''Scandinavia and the great powers 1890–1940'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002). * Sejersted, Francis. ''The Age of Social Democracy: Norway and Sweden in the Twentieth Century'' (Princeton UP, 2011); 543 pages; Traces the history of the Scandinavian social model after 1905. * Treasure, Geoffrey. ''The Making of Modern Europe, 1648–1780'' (3rd ed. 2003). pp 494–526.

Guides and travel tips about: Scandinavia For Visitors

Scandophile

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Scandinavia

Emigration

Many Scandinavians emigrated to Canada, the United States, Australia, Africa, and New Zealand during the later nineteenth century. The main wave of Scandinavian emigration occurred in the 1860s lasting until the 1880s, although substantial emigration continued until the 1930s. The vast majority of emigrants left from the countryside in search of better farming and economic opportunities. Together with Finland and Iceland, almost a third of the population left in the eighty years after 1850. Part of the reason for the large exodus was the increasing population caused by falling death rates, which increased unemployment. Norway had the largest percentage of emigrants and Denmark the least. Between 1820 and 1920 just over two million Scandinavians settled in the United States. One million came from Sweden, 300,000 from Denmark, and 730,000 from NorwayThe figure for Norway represents almost 80% of the national population in 1800. The most popular destinations in North America were Minnesota, Iowa, the Dakotas, Wisconsin, Michigan, the Canadian prairies and Ontario.

Monetary Union

The Scandinavian Monetary Union was a monetary union formed by Sweden and Denmark on 5 May 1873, by fixing their currencies against the

The Scandinavian Monetary Union was a monetary union formed by Sweden and Denmark on 5 May 1873, by fixing their currencies against the gold standard

A gold standard is a Backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

at par to each other. Norway, which was in union with Sweden entered the union two years later, in 1875 by pegging its currency to gold at the same level as Denmark and Sweden (.403 gram. The monetary union was one of the few tangible results of the Scandinavian political movement of the 19th century. The union provided fixed exchange rates and stability in monetary terms, but the member countries continued to issue their own separate currencies. Even if it was not initially foreseen, the perceived security led to a situation where the formally separate currencies were accepted on a basis of "as good as" the legal tender virtually throughout the entire area. The outbreak of World War I in 1914 brought an end to the monetary union. Sweden abandoned the tie to gold on 2 August 1914, and without a fixed exchange rate the free circulation came to an end.

20th century

First World War