Discovery

In an 1864 presentation, published in 1865, James Clerk Maxwell proposed theories of

In an 1864 presentation, published in 1865, James Clerk Maxwell proposed theories of by Heinrich Rudolph Hertz (English translation by Daniel Evan Jones), Macmillan and Co., 1893, pp. 1–5 Thus, given Hertz comprehensive discoveries, radio waves were referred to as "Hertzian waves".

Exploration of optical qualities

After the discovery of what came to be called "Hertzian waves" (it would take almost 20 years for the term "radio" to be universally adopted for this type of electromagnetic radiation) many scientists and inventors experimented with transmitting and detecting them. Maxwell's theory showing that light and Hertzian electromagnetic waves were the same phenomenon at different wavelengths led "Maxwellian" scientists such as John Perry,

After the discovery of what came to be called "Hertzian waves" (it would take almost 20 years for the term "radio" to be universally adopted for this type of electromagnetic radiation) many scientists and inventors experimented with transmitting and detecting them. Maxwell's theory showing that light and Hertzian electromagnetic waves were the same phenomenon at different wavelengths led "Maxwellian" scientists such as John Perry, Oliver Lodge: Almost the Father of Radio

page 5-6, from Antique Wireless

Building on the work of Lodge,Mukherji, Visvapriya, ''Jagadish Chandra Bose, 2nd ed.'' 1994. Builders of Modern India series, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. . the Bengali Indian physicist

Building on the work of Lodge,Mukherji, Visvapriya, ''Jagadish Chandra Bose, 2nd ed.'' 1994. Builders of Modern India series, Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. . the Bengali Indian physicist Proposed applications

Between 1890 and 1892 physicists such as John Perry,''

Marconi and radio telegraphy

In 1894, the young Italian inventor

In 1894, the young Italian inventor "The Inventor of Wireless Telegraphy: A Reply"

from Guglielmo Marconi (3 May 1902, pages 556-558) an

"Wireless Telegraphy: A Rejoinder"

from Silvanus P. Thompson (10 May 1902, pages 598-599) Marconi's apparatus is also credited with saving the 700 people who survived the tragic ''

Winter 2003-2004 (FCC.gov) In 1896, Marconi was awarded British patent 12039, ''Improvements in transmitting electrical impulses and signals and in apparatus there-for'', the first patent ever issued for a Hertzian wave (radio wave) base wireless telegraphic system. In 1897, he established a radio station on the

Audio transmission

In the late 1890s, Canadian-American inventor

In the late 1890s, Canadian-American inventor Part I

January 26, 1907, pages 49–51

Part II

February 2, 1907, pages 68–70, 79–80. which appears to have been the first successful audio transmission using radio signals. Although successful, the sound transmitted was far too distorted to be commercially practical. According to some sources, notably Fessenden's wife Helen's biography, on

Broadcasting

The Dutch company ''Nederlandsche Radio-Industrie'' and its owner engineer,Wavelength (meters) vs. frequency (kilocycles,

Radio companies

British Marconi

Using variousTelefunken

The companyTechnological development

Amplitude-modulated (AM)

The invention of amplitude-modulated (AM) radio, so that more than one station can send signals (as opposed to spark-gap radio, where one transmitter covers the entire bandwidth of the spectrum) is attributed toCrystal sets

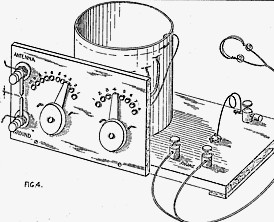

The most common type of receiver before vacuum tubes was the

The most common type of receiver before vacuum tubes was the Vacuum tubes

During the mid-1920s, amplifying

During the mid-1920s, amplifying Transistor technology

Following development of

Following development of Radio telex

Radio navigation

One of the first developments in the early 20th century was that aircraft used commercial AM radio stations for navigation, AM stations are still marked on U.S. aviation charts.FM

In 1933,FM in Europe

After World War II,Television

In the 1930s, regularColor television

* 1953:Mobile phones

In 1947 AT&T commercialized theby Tom Farley .

by Kathi Ann Brown (extract from ''Bringing Information to People'', 1993) (MilestonesPast.com) gave much more capacity. It was the primary analog mobile phone system in North America (and other locales) through the 1980s and into the 2000s. In 1947, AT&T commercialized the

Broadcast and copyright

The British government and the state-owned postal services found themselves under massive pressure from the wireless industry (including telegraphy) and early radio adopters to open up to the new medium. In an internal confidential report from February 25, 1924, the ''Imperial Wireless Telegraphy Committee'' stated: :"We have been asked 'to consider and advise on the policy to be adopted as regards the Imperial Wireless Services so as to protect and facilitate public interest.' It was impressed upon us that the question was urgent. We did not feel called upon to explore the past or to comment on the delays which have occurred in the building of the Empire Wireless Chain. We concentrated our attention on essential matters, examining and considering the facts and circumstances which have a direct bearing on policy and the condition which safeguard public interests." When radio was introduced in the early 1920s, many predicted it would kill theRegulations of radio stations in the U.S

Wireless Ship Act of 1910

Radio technology was first used for ships to communicate at sea. To ensure safety, theRadio Act of 1912

In 1912, distress calls to aid the sinking ''Titanic'' were met with a large amount of interfering radio traffic, severely hampering the rescue effort. Subsequently, the US government passed theThe Radio Act of 1927

TheThe Communications Act of 1934

The introduction of theThe Telecommunications Act of 1996

TheLicensed commercial public radio stations

The question of the 'first' publicly targeted licensed radio station in the U.S. has more than one answer and depends on semantics. Settlement of this 'first' question may hang largely upon what constitutes 'regular' programming

* It is commonly attributed to KDKA in

The question of the 'first' publicly targeted licensed radio station in the U.S. has more than one answer and depends on semantics. Settlement of this 'first' question may hang largely upon what constitutes 'regular' programming

* It is commonly attributed to KDKA in See also

;Histories *''

Footnotes

References

Primary sources

* De Lee Forest. ''Father of Radio: The Autobiography of Lee de Forest'' (1950). * Gleason L. Archer Personal Papers (MS108), Suffolk University Archives, Suffolk University; Boston, MassachusettsGleason L. Archer Personal Papers (MS108) finding aid

* Kahn Frank J., ed. ''Documents of American Broadcasting,'' fourth edition (Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1984). * Lichty Lawrence W., and Topping Malachi C., eds. ''American Broadcasting: A Source Book on the History of Radio and Television'' (Hastings House, 1975).

Secondary sources

* Aitkin, Hugh G. J. ''The Continuous Wave: Technology and the American Radio, 1900-1932'' (Princeton University Press, 1985). * Anderson, Leland. "''Nikola Tesla On His Work With Alternating Currents and Their Application to Wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power''", Sun Publishing Company, LC , (''ed''* Anderson, Leland I. ''Priority in the Invention of Radio �

', Antique Wireless Association monograph, 1980, examining the 1943 decision by the

Fessenden and Marconi: Their Differing Technologies and Transatlantic Experiments During the First Decade of this Century

'". International Conference on 100 Years of Radio (5–7 September 1995). * Briggs, Asa. ''The BBC — the First Fifty Years'' (Oxford University Press, 1984). * Briggs, Asa. ''The History of Broadcasting in the United Kingdom'' (Oxford University Press, 1961). * Brodsky, Ira. "The History of Wireless: How Creative Minds Produced Technology for the Masses" (Telescope Books, 2008) * Butler, Lloyd (VK5BR), "

Before Valve Amplification

- Wireless Communication of an Early Era''" * Coe, Douglas and Kreigh Collins (ills), "''Marconi, pioneer of radio''". New York, J. Messner, Inc., 1943. LCCN 43010048 * Covert, Cathy and Stevens John L. ''Mass Media Between the Wars'' (Syracuse University Press, 1984). * Craig, Douglas B. ''Fireside Politics: Radio and Political Culture in the United States, 1920–1940'' (2005) * Crook, Tim. ''International Radio Journalism: History, Theory and Practice'' Routledge, 1998 * Douglas, Susan J., ''Listening in : radio and the American imagination : from Amos ’n’ Andy and Edward R. Murrow to Wolfman Jack and Howard Stern '', New York, N.Y. : Times Books, 1999. * Ewbank Henry and Lawton Sherman P. ''Broadcasting: Radio and Television'' (Harper & Brothers, 1952). * Garratt, G. R. M., "''The early history of radio : from Faraday to Marconi''", London, Institution of Electrical Engineers in association with the Science Museum, History of technology series, 1994. LCCN gb 94011611 * Geddes, Keith, "''Guglielmo Marconi, 1874-1937''". London : H.M.S.O., A Science Museum booklet, 1974. LCCN 75329825 (''ed''. Obtainable in the US from Pendragon House Inc., Palo Alto, California.) * Gibson, George H. ''Public Broadcasting; The Role of the Federal Government, 1919-1976'' (Praeger Publishers, 1977). * Hancock, Harry Edgar, "''Wireless at sea; the first fifty years. A history of the progress and development of marine wireless communications written to commemorate the jubilee of the Marconi International Marine Communication Company limited''". Chelmsford, Eng., Marconi International Marine Communication Co., 1950. LCCN 51040529 /L * Jackaway, Gwenyth L. ''Media at War: Radio's Challenge to the Newspapers, 1924-1939'' Praeger Publishers, 1995 * Journal of the Franklin Institute. "

Notes and comments; Telegraphy without wires

'", Journal of the Franklin Institute, December 1897, pages 463–464. * Katz, Randy H., "

'". History of Communications Infrastructures. * Lazarsfeld, Paul F. ''The People Look at Radio'' (University of North Carolina Press, 1946). * Maclaurin, W. Rupert. ''Invention and Innovation in the Radio Industry'' (The Macmillan Company, 1949). * Marconi's Wireless Telegraph Company, "''Year book of wireless telegraphy and telephony''", London : Published for the Marconi Press Agency Ltd., by the St. Catherine Press / Wireless Press. LCCN 14017875 sn 86035439 * Marincic, Aleksandar and Djuradj Budimir, "

Tesla contribution to radio wave propagation

'". (

The Early Days of Radio in America

'".

Invention of Radio Celebrated in S.F.

100th birthday exhibit this weekend ''". San Francisco Chronicle, 1995. * ''The Prestige'', 2006, Touchstone Pictures. * The Radio Staff of the Detroit News, ''WWJ-The Detroit News'' (The Evening News Association, Detroit, 1922). * Ray, William B. ''FCC: The Ups and Downs of Radio-TV Regulation'' (Iowa State University Press, 1990). * Rosen, Philip T. ''The Modern Stentors; Radio Broadcasting and the Federal Government 1920-1934'' (Greenwood Press, 1980). ** Rugh, William A. ''Arab Mass Media: Newspapers, Radio, and Television in Arab Politics'' Praeger, 2004 * Scannell, Paddy, and Cardiff, David. ''A Social History of British Broadcasting, Volume One, 1922-1939'' (Basil Blackwell, 1991). * Schramm Wilbur, ed. ''Mass Communications'' (University of Illinois Press, 1960). * Schwoch James. ''The American Radio Industry and Its Latin American Activities, 1900-1939'' (University of Illinois Press, 1990). * Seifer, Marc J., "''The Secret History of Wireless''". Kingston, Rhode Island. * Slater, Robert. ''This ... is CBS: A Chronicle of 60 Years'' (Prentice Hall, 1988). * Smith, F. Leslie, John W. Wright II, David H. Ostroff; ''Perspectives on Radio and Television: Telecommunication in the United States'' Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998 * Sterling, Christopher H. ''Electronic Media, A Guide to Trends in Broadcasting and Newer Technologies 1920–1983'' (Praeger, 1984). * Sterling, Christopher, and Kittross John M. ''Stay Tuned: A Concise History of American Broadcasting'' (Wadsworth, 1978). * Stone, John Stone. "John Stone Stone on Nikola Tesla's Priority in Radio and Continuous-Wave Radiofrequency Apparatus"

Twenty First Century Books, 2005

* Sungook Hong, "''Wireless: from Marconi's Black-box to the Audion''", Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2001, * Waldron, Richard Arthur, "''Theory of guided electromagnetic waves''". London, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1970. LCCN 69019848 //r86 * Weightman, Gavin, "''Signor Marconi's magic box : the most remarkable invention of the 19th century & the amateur inventor whose genius sparked a revolution''" 1st Da Capo Press ed., Cambridge, Massachusetts : Da Capo Press, 2003. * White, Llewellyn. ''The American Radio'' (University of Chicago Press, 1947). * White, Thomas H. "

'", United States Early Radio History. * Wunsch, A. David "

'" Mercurians.org.

Media and documentaries

* '' Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio'' (1992) byExternal links

*"A Comparison of the Tesla and Marconi Low-Frequency Wireless Systems

''". Twenty First Century Books, Breckenridge, Co.

. Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers. Held at the Engineering Society Building, New York City, Friday evening, May 18, 1917. *

An important chapter in the Death of Distance''. Nova Scotia, Canada, March 14, 2006.

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Radio Guglielmo Marconi