History of quantum physics on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of

The history of

The theory of

The theory of

The Davisson–Germer experiment, which demonstrates the wave nature of the electron

/ref> in the

Compendium of Quantum Physics

Concepts, Experiments, History and Philosophy'', New York: Springer, 2009. . * * * F. Bayen, M. Flato, C. Fronsdal, A. Lichnerowicz and D. Sternheimer, Deformation theory and quantization I,and II, ''Ann. Phys. (N.Y.)'', 111 (1978) pp. 61–151. * D. Cohen, ''An Introduction to Hilbert Space and Quantum Logic'', Springer-Verlag, 1989. This is a thorough and well-illustrated introduction. * * A. Gleason. Measures on the Closed Subspaces of a Hilbert Space, ''Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics'', 1957. * R. Kadison. Isometries of Operator Algebras, ''Annals of Mathematics'', Vol. 54, pp. 325–38, 1951 * G. Ludwig. ''Foundations of Quantum Mechanics'', Springer-Verlag, 1983. * G. Mackey. ''Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics'', W. A. Benjamin, 1963 (paperback reprint by Dover 2004). * R. Omnès. ''Understanding Quantum Mechanics'', Princeton University Press, 1999. (Discusses logical and philosophical issues of quantum mechanics, with careful attention to the history of the subject). * N. Papanikolaou. ''Reasoning Formally About Quantum Systems: An Overview'', ACM SIGACT News, 36(3), pp. 51–66, 2005. * C. Piron. ''Foundations of Quantum Physics'', W. A. Benjamin, 1976. * Hermann Weyl. ''The Theory of Groups and Quantum Mechanics'', Dover Publications, 1950. * A. Whitaker. ''The New Quantum Age: From Bell's Theorem to Quantum Computation and Teleportation'', Oxford University Press, 2011, * Stephen Hawking. ''The Dreams that Stuff is Made of'', Running Press, 2011, * A. Douglas Stone. ''Einstein and the Quantum, the Quest of the Valiant Swabian'', Princeton University Press, 2006. * Richard P. Feynman. '' QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter''. Princeton University Press, 2006. Print.

A History of Quantum MechanicsHomepage of the Quantum History Project

{{DEFAULTSORT:Quantum mechanics History of chemistry History of physics zh:物理学史#量子理论

The history of

The history of quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, ...

is a fundamental part of the history of modern physics. Quantum mechanics' history, as it interlaces with the history of quantum chemistry

Quantum chemistry, also called molecular quantum mechanics, is a branch of physical chemistry focused on the application of quantum mechanics to chemical systems, particularly towards the quantum-mechanical calculation of electronic contributions ...

, began essentially with a number of different scientific discoveries: the 1838 discovery of cathode rays

Cathode rays or electron beam (e-beam) are streams of electrons observed in discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to ele ...

by Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inducti ...

; the 1859–60 winter statement of the black-body radiation

Black-body radiation is the thermal electromagnetic radiation within, or surrounding, a body in thermodynamic equilibrium with its environment, emitted by a black body (an idealized opaque, non-reflective body). It has a specific, continuous spect ...

problem by Gustav Kirchhoff; the 1877 suggestion by Ludwig Boltzmann that the energy state

A quantum mechanical system or particle that is bound—that is, confined spatially—can only take on certain discrete values of energy, called energy levels. This contrasts with classical particles, which can have any amount of energy. The te ...

s of a physical system could be ''discrete''; the discovery of the photoelectric effect by Heinrich Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz ( ; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's Maxwell's equations, equations of electrom ...

in 1887; and the 1900 quantum hypothesis by Max Planck that any energy-radiating atomic system can theoretically be divided into a number of discrete "energy elements" ''ε'' (Greek letter epsilon

Epsilon (, ; uppercase , lowercase or lunate ; el, έψιλον) is the fifth letter of the Greek alphabet, corresponding phonetically to a mid front unrounded vowel or . In the system of Greek numerals it also has the value five. It was der ...

) such that each of these energy elements is proportional to the frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

''ν'' with which each of them individually radiate energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of heat a ...

, as defined by the following formula:

:

where ''h'' is a numerical value called Planck's constant.

Then, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

in 1905, in order to explain the photoelectric effect previously reported by Heinrich Hertz

Heinrich Rudolf Hertz ( ; ; 22 February 1857 – 1 January 1894) was a German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves predicted by James Clerk Maxwell's Maxwell's equations, equations of electrom ...

in 1887, postulated consistently with Max Planck's quantum hypothesis that light itself is made of individual quantum particles, which in 1926 came to be called photons

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless, so they alway ...

by Gilbert N. Lewis

Gilbert Newton Lewis (October 23 or October 25, 1875 – March 23, 1946) was an American physical chemist and a Dean of the College of Chemistry at University of California, Berkeley. Lewis was best known for his discovery of the covalent bond a ...

. The photoelectric effect was observed upon shining light of particular wavelengths on certain materials, such as metals, which caused electrons to be ejected from those materials only if the light quantum energy was greater than the work function

In solid-state physics, the work function (sometimes spelt workfunction) is the minimum thermodynamic work (i.e., energy) needed to remove an electron from a solid to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the solid surface. Here "immediately" m ...

of the metal's surface.

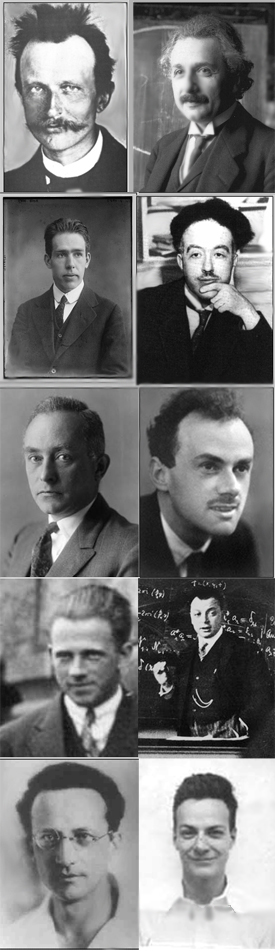

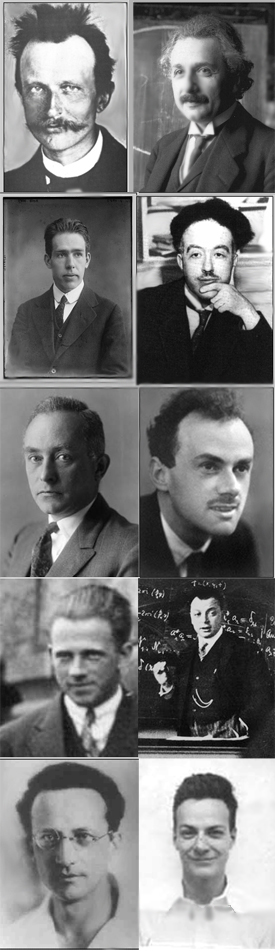

The phrase "quantum mechanics" was coined (in German, ''Quantenmechanik'') by the group of physicists including Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German physicist and mathematician who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics and supervised the work of a n ...

, Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg () (5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist and one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics. He published his work in 1925 in a breakthrough paper. In the subsequent series ...

, and Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli (; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist and one of the pioneers of quantum physics. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics fo ...

, at the University of Göttingen

The University of Göttingen, officially the Georg August University of Göttingen, (german: Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, known informally as Georgia Augusta) is a public research university in the city of Göttingen, Germany. Founded ...

in the early 1920s, and was first used in Born's 1924 paper ''"Zur Quantenmechanik"''. In the years to follow, this theoretical basis slowly began to be applied to chemical structure

A chemical structure determination includes a chemist's specifying the molecular geometry and, when feasible and necessary, the electronic structure of the target molecule or other solid. Molecular geometry refers to the spatial arrangement of at ...

, reactivity, and bonding.

Predecessors and the "old quantum theory"

During the early 19th century, chemical research byJohn Dalton

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English chemist, physicist and meteorologist. He is best known for introducing the atomic theory into chemistry, and for his research into colour blindness, which he had. Colour b ...

and Amedeo Avogadro lent weight to the atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter a ...

of matter, an idea that James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism and ligh ...

, Ludwig Boltzmann and others built upon to establish the kinetic theory of gases

Kinetic (Ancient Greek: κίνησις “kinesis”, movement or to move) may refer to:

* Kinetic theory, describing a gas as particles in random motion

* Kinetic energy, the energy of an object that it possesses due to its motion

Art and enter ...

. The successes of kinetic theory gave further credence to the idea that matter is composed of atoms, yet the theory also had shortcomings that would only be resolved by the development of quantum mechanics. The existence of atoms was not universally accepted among physicists or chemists; Ernst Mach

Ernst Waldfried Josef Wenzel Mach ( , ; 18 February 1838 – 19 February 1916) was a Moravian-born Austrian physicist and philosopher, who contributed to the physics of shock waves. The ratio of one's speed to that of sound is named the Mach ...

, for example, was a staunch anti-atomist.

Ludwig Boltzmann suggested in 1877 that the energy levels of a physical system, such as a molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioch ...

, could be discrete (rather than continuous). Boltzmann's rationale for the presence of discrete energy levels in molecules such as those of iodine gas had its origins in his statistical thermodynamics and statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. It does not assume or postulate any natural laws, but explains the macroscopic be ...

theories and was backed up by mathematical arguments, as would also be the case twenty years later with the first quantum theory

Quantum theory may refer to:

Science

*Quantum mechanics, a major field of physics

*Old quantum theory, predating modern quantum mechanics

* Quantum field theory, an area of quantum mechanics that includes:

** Quantum electrodynamics

** Quantum ch ...

put forward by Max Planck.

In 1900, the German physicist Max Planck, who had never believed in discrete atoms, reluctantly introduced the idea that energy is ''quantized'' in order to derive a formula for the observed frequency dependence of the energy emitted by a black body, called Planck's law

In physics, Planck's law describes the spectral density of electromagnetic radiation emitted by a black body in thermal equilibrium at a given temperature , when there is no net flow of matter or energy between the body and its environment.

At ...

, that included a Boltzmann distribution (applicable in the classical limit). Planck's law can be stated as follows:

:

where

: ''I''(''ν'', ''T'') is the energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of heat a ...

per unit time (or the power) radiated per unit area of emitting surface in the normal direction per unit solid angle per unit frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

by a black body at temperature ''T'';

: ''h'' is the Planck constant

The Planck constant, or Planck's constant, is a fundamental physical constant of foundational importance in quantum mechanics. The constant gives the relationship between the energy of a photon and its frequency, and by the mass-energy equivale ...

;

: ''c'' is the speed of light

The speed of light in vacuum, commonly denoted , is a universal physical constant that is important in many areas of physics. The speed of light is exactly equal to ). According to the special theory of relativity, is the upper limit ...

in a vacuum;

: ''k'' is the Boltzmann constant

The Boltzmann constant ( or ) is the proportionality factor that relates the average relative kinetic energy of particles in a gas with the thermodynamic temperature of the gas. It occurs in the definitions of the kelvin and the gas constant, ...

;

: ''ν'' ( nu) is the frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

of the electromagnetic radiation;

: ''T'' is the temperature

Temperature is a physical quantity that expresses quantitatively the perceptions of hotness and coldness. Temperature is measured with a thermometer.

Thermometers are calibrated in various temperature scales that historically have relied o ...

of the body in kelvin

The kelvin, symbol K, is the primary unit of temperature in the International System of Units (SI), used alongside its prefixed forms and the degree Celsius. It is named after the Belfast-born and University of Glasgow-based engineer and phys ...

s.

The earlier Wien approximation

Wien's approximation (also sometimes called Wien's law or the Wien distribution law) is a law of physics used to describe the spectrum of thermal radiation (frequently called the blackbody function). This law was first derived by Wilhelm Wien in ...

may be derived from Planck's law by assuming .

In 1905, Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

used kinetic theory to explain Brownian motion. French physicist Jean Baptiste Perrin used the model in Einstein's paper to experimentally determine the mass, and the dimensions, of atoms, thereby giving direct empirical verification of the atomic theory. Also in 1905, Einstein explained the photoelectric effect by postulating that light, or more generally all electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) consists of waves of the electromagnetic field, electromagnetic (EM) field, which propagate through space and carry momentum and electromagnetic radiant energy. It includes radio waves, microwaves, inf ...

, can be divided into a finite number of "energy quanta" that are localized points in space. From the introduction section of his March 1905 quantum paper "On a heuristic viewpoint concerning the emission and transformation of light", Einstein states:

This statement has been called the most revolutionary sentence written by a physicist of the twentieth century. These ''energy quanta'' later came to be called "photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless, so they always ...

s", a term introduced by Gilbert N. Lewis

Gilbert Newton Lewis (October 23 or October 25, 1875 – March 23, 1946) was an American physical chemist and a Dean of the College of Chemistry at University of California, Berkeley. Lewis was best known for his discovery of the covalent bond a ...

in 1926. The idea that each photon had to consist of energy in terms of quanta was a remarkable achievement; it effectively solved the problem of black-body radiation attaining infinite energy, which occurred in theory if light were to be explained only in terms of waves.

An important step was taken in the evolution of quantum theory at the first Solvay Congress

The Solvay Conferences (french: Conseils Solvay) have been devoted to outstanding preeminent open problems in both physics and chemistry. They began with the historic invitation-only 1911 Solvay Conference on Physics, considered a turning point ...

of 1911. There the top physicists of the scientific community met to discuss the problem of “Radiation and the Quanta.” By this time the Ernest Rutherford model of the atom had been published, but much of the discussion involving atomic structure revolved around the quantum model of Arthur Haas

Arthur Erich Haas (April 30, 1884 in Brno – February 20, 1941 in Chicago) was an Austrian physicist, noted for a 1910 paper he submitted in support of his habilitation as ''Privatdocent'' at the University of Vienna that outlined a treatm ...

in 1910. Also, at the Solvay Congress in 1911 Hendrik Lorentz

Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (; 18 July 1853 – 4 February 1928) was a Dutch physicist who shared the 1902 Nobel Prize in Physics with Pieter Zeeman for the discovery and theoretical explanation of the Zeeman effect. He also derived the Lorentz t ...

suggested after Einstein’s talk on quantum structure that the energy of a rotator be set equal to nhv. This was followed by other quantum models such as the John William Nicholson model of 1912 which was nuclear and quantized angular momentum. Nicholson had introduced the spectra into his atomic model by using the oscillations of electrons in a nuclear atom perpendicular to the orbital plane thereby maintaining stability. Nicholson’s atomic spectra identified many unattributed lines in solar and nebular spectra.

In 1913, Bohr explained the spectral line

A spectral line is a dark or bright line in an otherwise uniform and continuous spectrum, resulting from emission or absorption of light in a narrow frequency range, compared with the nearby frequencies. Spectral lines are often used to iden ...

s of the hydrogen atom

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral atom contains a single positively charged proton and a single negatively charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb force. Atomic hydrogen consti ...

, again by using quantization, in his paper of July 1913 ''On the Constitution of Atoms and Molecules'' in which he discussed and cited the Nicholson model. In the Bohr model, the hydrogen atom is pictured as a heavy, positively-charged nucleus orbited by a light, negatively-charged electron. The electron can only exist in certain, discretely separated orbits, labeled by their angular momentum

In physics, angular momentum (rarely, moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a conserved quantity—the total angular momentum of a closed syst ...

, which is restricted to be an integer multiple of the reduced Planck constant.

The model's key success lay in explaining the Rydberg formula for the spectral emission lines

A spectral line is a dark or bright line in an otherwise uniform and continuous spectrum, resulting from emission or absorption of light in a narrow frequency range, compared with the nearby frequencies. Spectral lines are often used to iden ...

of atomic hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

by using the transitions of electrons between orbits. While the Rydberg formula had been known experimentally, it did not gain a theoretical underpinning until the Bohr model was introduced. Not only did the Bohr model explain the reasons for the structure of the Rydberg formula, it also provided a justification for the fundamental physical constants that make up the formula's empirical results.

Moreover, the application of Planck's quantum theory to the electron allowed Ștefan Procopiu

Ștefan Procopiu (; January 19, 1890 – August 22, 1972) was a Romanian physicist and a titular member of the Romanian Academy.

Biography

Procopiu was born in 1890 in Bârlad, Romania. His father, Emanoil Procopiu, was employed at the Bâr ...

in 1911–1913, and subsequently Niels Bohr in 1913, to calculate the magnetic moment

In electromagnetism, the magnetic moment is the magnetic strength and orientation of a magnet or other object that produces a magnetic field. Examples of objects that have magnetic moments include loops of electric current (such as electromagnets ...

of the electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

, which was later called the " magneton"; similar quantum computations, but with numerically quite different values, were subsequently made possible for both the magnetic moment

In electromagnetism, the magnetic moment is the magnetic strength and orientation of a magnet or other object that produces a magnetic field. Examples of objects that have magnetic moments include loops of electric current (such as electromagnets ...

s of the proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

and the neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , which has a neutral (not positive or negative) charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. Protons and neutrons constitute the nuclei of atoms. Since protons and neutrons beh ...

that are three orders of magnitude smaller than that of the electron.

These theories, though successful, were strictly phenomenological

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

: during this time, there was no rigorous justification for quantization, aside, perhaps, from Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré ( S: stress final syllable ; 29 April 1854 – 17 July 1912) was a French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathematics as "The ...

's discussion of Planck's theory in his 1912 paper .

They are collectively known as the '' old quantum theory''.

The phrase "quantum physics" was first used in Johnston's ''Planck's Universe in Light of Modern Physics'' (1931).

In 1923, the French physicist Louis de Broglie put forward his theory of matter waves by stating that particles can exhibit wave characteristics and vice versa. This theory was for a single particle and derived from special relativity theory. Building on de Broglie's approach, modern quantum mechanics was born in 1925, when the German physicists Werner Heisenberg

Werner Karl Heisenberg () (5 December 1901 – 1 February 1976) was a German theoretical physicist and one of the main pioneers of the theory of quantum mechanics. He published his work in 1925 in a breakthrough paper. In the subsequent series ...

, Max Born

Max Born (; 11 December 1882 – 5 January 1970) was a German physicist and mathematician who was instrumental in the development of quantum mechanics. He also made contributions to solid-state physics and optics and supervised the work of a n ...

, and Pascual Jordan developed matrix mechanics and the Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger invented wave mechanics and the non-relativistic Schrödinger equation as an approximation of the generalised case of de Broglie's theory. Schrödinger subsequently showed that the two approaches were equivalent. The first applications of quantum mechanics to physical systems were the algebraic determination of the hydrogen spectrum by Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli (; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist and one of the pioneers of quantum physics. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics fo ...

and the treatment of diatomic molecules by Lucy Mensing

Lucy Mensing (also Lucie), later Mensing-Schütz or Schütz, (11 March 1901 - 28 April 1995) was a German physicist and a pioneer of quantum mechanics.

Scientific career

Mensing studied mathematics, physics and chemistry at the University of Ha ...

.

Modern quantum mechanics

Heisenberg formulated an early version of theuncertainty principle

In quantum mechanics, the uncertainty principle (also known as Heisenberg's uncertainty principle) is any of a variety of mathematical inequalities asserting a fundamental limit to the accuracy with which the values for certain pairs of physic ...

in 1927, analyzing a thought experiment

A thought experiment is a hypothetical situation in which a hypothesis, theory, or principle is laid out for the purpose of thinking through its consequences.

History

The ancient Greek ''deiknymi'' (), or thought experiment, "was the most anci ...

where one attempts to measure an electron's position and momentum simultaneously. However, Heisenberg did not give precise mathematical definitions of what the "uncertainty" in these measurements meant, a step that would be taken soon after by Earle Hesse Kennard

Earle Hesse Kennard (August 2, 1885 – January 31, 1968) was a theoretical physicist and professor at Cornell University.

Biography

Kennard was born in Columbus, Ohio and studied at Pomona College and Oxford University as part of a Rhodes Sch ...

, Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Ernst Pauli (; ; 25 April 1900 – 15 December 1958) was an Austrian theoretical physicist and one of the pioneers of quantum physics. In 1945, after having been nominated by Albert Einstein, Pauli received the Nobel Prize in Physics fo ...

, and Hermann Weyl

Hermann Klaus Hugo Weyl, (; 9 November 1885 – 8 December 1955) was a German mathematician, theoretical physicist and philosopher. Although much of his working life was spent in Zürich, Switzerland, and then Princeton, New Jersey, he is assoc ...

. Starting around 1927, Paul Dirac

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English theoretical physicist who is regarded as one of the most significant physicists of the 20th century. He was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the Univer ...

began the process of unifying quantum mechanics with special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory regarding the relationship between space and time. In Albert Einstein's original treatment, the theory is based on two postulates:

# The laws o ...

by proposing the Dirac equation for the electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

. The Dirac equation achieves the relativistic description of the wavefunction of an electron that Schrödinger failed to obtain. It predicts electron spin and led Dirac to predict the existence of the positron

The positron or antielectron is the antiparticle or the antimatter counterpart of the electron. It has an electric charge of +1 '' e'', a spin of 1/2 (the same as the electron), and the same mass as an electron. When a positron collides ...

. He also pioneered the use of operator theory, including the influential bra–ket notation

In quantum mechanics, bra–ket notation, or Dirac notation, is used ubiquitously to denote quantum states. The notation uses angle brackets, and , and a vertical bar , to construct "bras" and "kets".

A ket is of the form , v \rangle. Mathema ...

, as described in his famous 1930 textbook. During the same period, Hungarian polymath John von Neumann

John von Neumann (; hu, Neumann János Lajos, ; December 28, 1903 – February 8, 1957) was a Hungarian-American mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, engineer and polymath. He was regarded as having perhaps the widest cove ...

formulated the rigorous mathematical basis for quantum mechanics as the theory of linear operators on Hilbert spaces, as described in his likewise famous 1932 textbook. These, like many other works from the founding period, still stand, and remain widely used.

The field of quantum chemistry

Quantum chemistry, also called molecular quantum mechanics, is a branch of physical chemistry focused on the application of quantum mechanics to chemical systems, particularly towards the quantum-mechanical calculation of electronic contributions ...

was pioneered by physicists Walter Heitler

Walter Heinrich Heitler (; 2 January 1904 – 15 November 1981) was a German physicist who made contributions to quantum electrodynamics and quantum field theory. He brought chemistry under quantum mechanics through his theory of valence bond ...

and Fritz London, who published a study of the covalent bond

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

of the hydrogen molecule

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxic, an ...

in 1927. Quantum chemistry was subsequently developed by a large number of workers, including the American theoretical chemist Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling (; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist, biochemist, chemical engineer, peace activist, author, and educator. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific top ...

at Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

, and John C. Slater

John Clarke Slater (December 22, 1900 – July 25, 1976) was a noted American physicist who made major contributions to the theory of the electronic structure of atoms, molecules and solids. He also made major contributions to microwave electroni ...

into various theories such as Molecular Orbital Theory or Valence Theory.

Quantum field theory

Beginning in 1927, researchers attempted to apply quantum mechanics to fields instead of single particles, resulting inquantum field theories

In theoretical physics, quantum field theory (QFT) is a theoretical framework that combines classical field theory, special relativity, and quantum mechanics. QFT is used in particle physics to construct physical models of subatomic particles ...

. Early workers in this area include P.A.M. Dirac, W. Pauli, V. Weisskopf, and P. Jordan. This area of research culminated in the formulation of quantum electrodynamics by R.P. Feynman

Richard Phillips Feynman (; May 11, 1918 – February 15, 1988) was an American theoretical physicist, known for his work in the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics, the theory of quantum electrodynamics, the physics of the superflu ...

, F. Dyson, J. Schwinger, and S. Tomonaga during the 1940s. Quantum electrodynamics describes a quantum theory of electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

s, positron

The positron or antielectron is the antiparticle or the antimatter counterpart of the electron. It has an electric charge of +1 '' e'', a spin of 1/2 (the same as the electron), and the same mass as an electron. When a positron collides ...

s, and the electromagnetic field

An electromagnetic field (also EM field or EMF) is a classical (i.e. non-quantum) field produced by (stationary or moving) electric charges. It is the field described by classical electrodynamics (a classical field theory) and is the classical c ...

, and served as a model for subsequent quantum field theories

In theoretical physics, quantum field theory (QFT) is a theoretical framework that combines classical field theory, special relativity, and quantum mechanics. QFT is used in particle physics to construct physical models of subatomic particles ...

.

quantum chromodynamics

In theoretical physics, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the theory of the strong interaction between quarks mediated by gluons. Quarks are fundamental particles that make up composite hadrons such as the proton, neutron and pion. QCD is a type ...

was formulated beginning in the early 1960s. The theory as we know it today was formulated by Politzer Politzer is a surname deriving from Politz. Notable people with the surname include:

* Adam Politzer, Hungarian physician

**Politzerization, a treatment technique for ear infections, developed by him

* Georges Politzer, French philosopher

* H. Dav ...

, Gross and Wilczek in 1975.

Building on pioneering work by Schwinger, Higgs

Higgs may refer to:

Physics

*Higgs boson, an elementary particle

*Higgs mechanism, an explanation for electroweak symmetry breaking

*Higgs field, a quantum field

People

*Alan Higgs (died 1979), English businessman and philanthropist

*Blaine Higgs ...

and Goldstone, the physicists Glashow, Weinberg and Salam independently showed how the weak nuclear force and quantum electrodynamics could be merged into a single electroweak force

In particle physics, the electroweak interaction or electroweak force is the unified description of two of the four known fundamental interactions of nature: electromagnetism and the weak interaction. Although these two forces appear very differe ...

, for which they received the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then " ...

.

Quantum information

Quantum information science

Quantum information science is an interdisciplinary field that seeks to understand the analysis, processing, and transmission of information using quantum mechanics principles. It combines the study of Information science with quantum effects in p ...

developed in the latter decades of the 20th century, beginning with theoretical results like Holevo's theorem

Holevo's theorem is an important limitative theorem in quantum computing, an interdisciplinary field of physics and computer science. It is sometimes called Holevo's bound, since it establishes an upper bound to the amount of information that can ...

, the concept of generalized measurements or POVMs, the proposal of quantum key distribution by Bennett and Brassard, and Shor's algorithm

Shor's algorithm is a quantum algorithm, quantum computer algorithm for finding the prime factors of an integer. It was developed in 1994 by the American mathematician Peter Shor.

On a quantum computer, to factor an integer N , Shor's algorithm ...

.

Founding experiments

* Thomas Young'sdouble-slit experiment

In modern physics, the double-slit experiment is a demonstration that light and matter can display characteristics of both classically defined waves and particles; moreover, it displays the fundamentally probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics ...

demonstrating the wave nature of light. (c. 1801)

* Henri Becquerel discovers radioactivity. (1896)

*J. J. Thomson

Sir Joseph John Thomson (18 December 1856 – 30 August 1940) was a British physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be discovered.

In 1897, Thomson showed that c ...

's cathode ray tube experiments (discovers the electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

and its negative charge). (1897)

*The study of black-body radiation

Black-body radiation is the thermal electromagnetic radiation within, or surrounding, a body in thermodynamic equilibrium with its environment, emitted by a black body (an idealized opaque, non-reflective body). It has a specific, continuous spect ...

between 1850 and 1900, which could not be explained without quantum concepts.

*The photoelectric effect: Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theory ...

explained this in 1905 (and later received a Nobel prize for it) using the concept of photons, particles of light with quantized energy.

*Robert Millikan

Robert Andrews Millikan (March 22, 1868 – December 19, 1953) was an American experimental physicist honored with the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1923 for the measurement of the elementary electric charge and for his work on the photoelectric e ...

's oil-drop experiment

The oil drop experiment was performed by Robert A. Millikan and Harvey Fletcher in 1909 to measure the elementary electric charge (the charge of the electron). The experiment took place in the Ryerson Physical Laboratory at the University of Chi ...

, which showed that electric charge

Electric charge is the physical property of matter that causes charged matter to experience a force when placed in an electromagnetic field. Electric charge can be ''positive'' or ''negative'' (commonly carried by protons and electrons respe ...

occurs as '' quanta'' (whole units). (1909)

* Ernest Rutherford's gold foil experiment

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile meta ...

disproved the plum pudding model of the atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, and ...

which suggested that the mass and positive charge of the atom are almost uniformly distributed. This led to the planetary model of the atom (1911).

*James Franck

James Franck (; 26 August 1882 – 21 May 1964) was a German physicist who won the 1925 Nobel Prize for Physics with Gustav Hertz "for their discovery of the laws governing the impact of an electron upon an atom". He completed his doctorate in ...

and Gustav Hertz's electron collision experiment shows that energy absorption by mercury atoms is quantized. (1914)

*Otto Stern

:''Otto Stern was also the pen name of German women's rights activist Louise Otto-Peters (1819–1895)''.

Otto Stern (; 17 February 1888 – 17 August 1969) was a German-American physicist and Nobel laureate in physics. He was the second most n ...

and Walther Gerlach conduct the Stern–Gerlach experiment, which demonstrates the quantized nature of particle spin

Spin or spinning most often refers to:

* Spinning (textiles), the creation of yarn or thread by twisting fibers together, traditionally by hand spinning

* Spin, the rotation of an object around a central axis

* Spin (propaganda), an intentionally b ...

. (1920)

*Arthur Compton

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radia ...

with Compton scattering experiment (1923)

*Clinton Davisson

Clinton Joseph Davisson (October 22, 1881 – February 1, 1958) was an American physicist who won the 1937 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of electron diffraction in the famous Davisson–Germer experiment. Davisson shared the Nobel Priz ...

and Lester Germer Lester Halbert Germer (October 10, 1896 – October 3, 1971) was an American physicist. With Clinton Davisson, he proved the wave-particle duality of matter in the Davisson–Germer experiment, which was important to the development of the elect ...

demonstrate the wave nature of the electron

The electron ( or ) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family,

and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no kn ...

/ref> in the

electron diffraction

Electron diffraction refers to the bending of electron beams around atomic structures. This behaviour, typical for waves, is applicable to electrons due to the wave–particle duality stating that electrons behave as both particles and waves. Si ...

experiment. (1927)

* Carl David Anderson with the discovery positron

The positron or antielectron is the antiparticle or the antimatter counterpart of the electron. It has an electric charge of +1 '' e'', a spin of 1/2 (the same as the electron), and the same mass as an electron. When a positron collides ...

(1932), validated Paul Dirac

Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (; 8 August 1902 – 20 October 1984) was an English theoretical physicist who is regarded as one of the most significant physicists of the 20th century. He was the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at the Univer ...

's theoretical prediction of this particle (1928)

* Lamb– Retherford experiment discovered Lamb shift (1947), which led to the development of quantum electrodynamics.

*Clyde L. Cowan

Clyde Lorrain Cowan Jr (December 6, 1919 – May 24, 1974) was an American physicist, the co-discoverer of the neutrino along with Frederick Reines. The discovery was made in 1956 in the neutrino experiment.

Frederick Reines received the Nobel Pr ...

and Frederick Reines confirm the existence of the neutrino in the neutrino experiment. (1955)

*Clauss Jönsson

In modern physics, the double-slit experiment is a demonstration that light and matter can display characteristics of both classically defined waves and particles; moreover, it displays the fundamentally probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics ...

's double-slit experiment

In modern physics, the double-slit experiment is a demonstration that light and matter can display characteristics of both classically defined waves and particles; moreover, it displays the fundamentally probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics ...

with electrons. (1961)

*The quantum Hall effect, discovered in 1980 by Klaus von Klitzing. The quantized version of the Hall effect has allowed for the definition of a new practical standard for electrical resistance

The electrical resistance of an object is a measure of its opposition to the flow of electric current. Its reciprocal quantity is , measuring the ease with which an electric current passes. Electrical resistance shares some conceptual parallels ...

and for an extremely precise independent determination of the fine-structure constant.

*The experimental verification of quantum entanglement by John Clauser and Stuart Freedman

Stuart Jay Freedman (January 13, 1944 – November 10, 2012) was an American physicist, known for his work on a Bell test experiment with John Clauser at the University of California, Berkeley as well as for his contributions to nuclear and part ...

. (1972)

*The Mach–Zehnder interferometer experiment conducted by Paul Kwiat Paul Gregory Kwiat is an American physicist.

Kwiat earned a doctorate at the University of California, Berkeley in 1993, where he was advised by Raymond Chiao and authored the dissertation ''Nonclassical effects from spontaneous parametric down-con ...

, Harold Wienfurter, Thomas Herzog, Anton Zeilinger

Anton Zeilinger (; born 20 May 1945) is an Austrian quantum physicist and Nobel laureate in physics of 2022. Zeilinger is professor of physics emeritus at the University of Vienna and senior scientist at the Institute for Quantum Optics and Qua ...

, and Mark Kasevich, providing experimental verification of the Elitzur–Vaidman bomb tester, proving interaction-free measurement is possible. (1994)

See also

*Golden age of physics

A golden age of physics appears to have been delineated for certain periods of progress in the physics sciences, and this includes the previous and current developments of cosmology and astronomy. Each "golden age" introduces significant advanceme ...

* Einstein's thought experiments

*History of quantum field theory

In particle physics, the history of quantum field theory starts with its creation by Paul Dirac, when he attempted to quantize the electromagnetic field in the late 1920s. Heisenberg was awarded the 1932 Nobel Prize in Physics "for the creation o ...

*History of chemistry

The history of chemistry represents a time span from ancient history to the present. By 1000 BC, civilizations used technologies that would eventually form the basis of the various branches of chemistry. Examples include the discovery of fire, e ...

*History of molecular theory

In chemistry, the history of molecular theory traces the origins of the concept or idea of the existence of strong chemical bonds between two or more atoms.

The modern concept of molecules can be traced back towards pre-scientific and Greek phi ...

*History of thermodynamics

The history of thermodynamics is a fundamental strand in the history of physics, the history of chemistry, and the history of science in general. Owing to the relevance of thermodynamics in much of science and technology, its history is finely wo ...

*Timeline of atomic and subatomic physics

A timeline of atomic physics, atomic and subatomic particle, subatomic physics.

Early beginnings

*In 6th century BCE, Acharya Kaṇāda (philosopher), Kanada proposed that all matter must consist of indivisible particles and called them "anu". He ...

References

Further reading

* * * * Greenberger, Daniel,Hentschel, Klaus

Klaus Hentschel (born 4 April 1961) is a German physicist, historian of science and Professor and head of the History of Science and Technology section in the History Department of the University of Stuttgart. He is known for his contributions in ...

, Weinert, Friedel (Eds.) Compendium of Quantum Physics

Concepts, Experiments, History and Philosophy'', New York: Springer, 2009. . * * * F. Bayen, M. Flato, C. Fronsdal, A. Lichnerowicz and D. Sternheimer, Deformation theory and quantization I,and II, ''Ann. Phys. (N.Y.)'', 111 (1978) pp. 61–151. * D. Cohen, ''An Introduction to Hilbert Space and Quantum Logic'', Springer-Verlag, 1989. This is a thorough and well-illustrated introduction. * * A. Gleason. Measures on the Closed Subspaces of a Hilbert Space, ''Journal of Mathematics and Mechanics'', 1957. * R. Kadison. Isometries of Operator Algebras, ''Annals of Mathematics'', Vol. 54, pp. 325–38, 1951 * G. Ludwig. ''Foundations of Quantum Mechanics'', Springer-Verlag, 1983. * G. Mackey. ''Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics'', W. A. Benjamin, 1963 (paperback reprint by Dover 2004). * R. Omnès. ''Understanding Quantum Mechanics'', Princeton University Press, 1999. (Discusses logical and philosophical issues of quantum mechanics, with careful attention to the history of the subject). * N. Papanikolaou. ''Reasoning Formally About Quantum Systems: An Overview'', ACM SIGACT News, 36(3), pp. 51–66, 2005. * C. Piron. ''Foundations of Quantum Physics'', W. A. Benjamin, 1976. * Hermann Weyl. ''The Theory of Groups and Quantum Mechanics'', Dover Publications, 1950. * A. Whitaker. ''The New Quantum Age: From Bell's Theorem to Quantum Computation and Teleportation'', Oxford University Press, 2011, * Stephen Hawking. ''The Dreams that Stuff is Made of'', Running Press, 2011, * A. Douglas Stone. ''Einstein and the Quantum, the Quest of the Valiant Swabian'', Princeton University Press, 2006. * Richard P. Feynman. '' QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter''. Princeton University Press, 2006. Print.

External links

A History of Quantum Mechanics

{{DEFAULTSORT:Quantum mechanics History of chemistry History of physics zh:物理学史#量子理论