History Of PCR on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

:''(This article assumes familiarity with the terms and components used in the PCR process.)''

The history of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has variously been described as a classic "Eureka!" moment,Kary Mullis' Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1993

The history of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has variously been described as a classic "Eureka!" moment,Kary Mullis' Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1993

/ref> or as an example of cooperative teamwork between disparate researchers. Following is a list of events before, during, and after its development:

The history of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has variously been described as a classic "Eureka!" moment,Kary Mullis' Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1993

The history of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) has variously been described as a classic "Eureka!" moment,Kary Mullis' Nobel Lecture, December 8, 1993/ref> or as an example of cooperative teamwork between disparate researchers. Following is a list of events before, during, and after its development:

Prelude

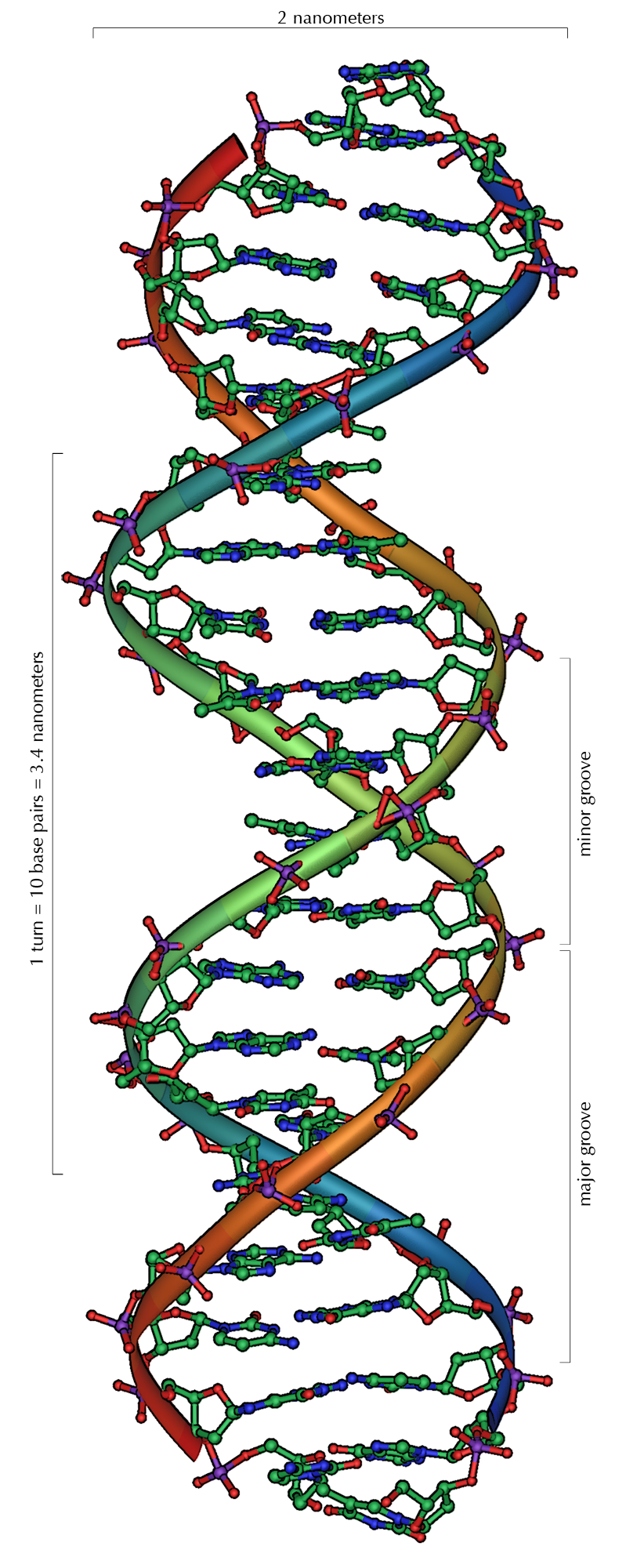

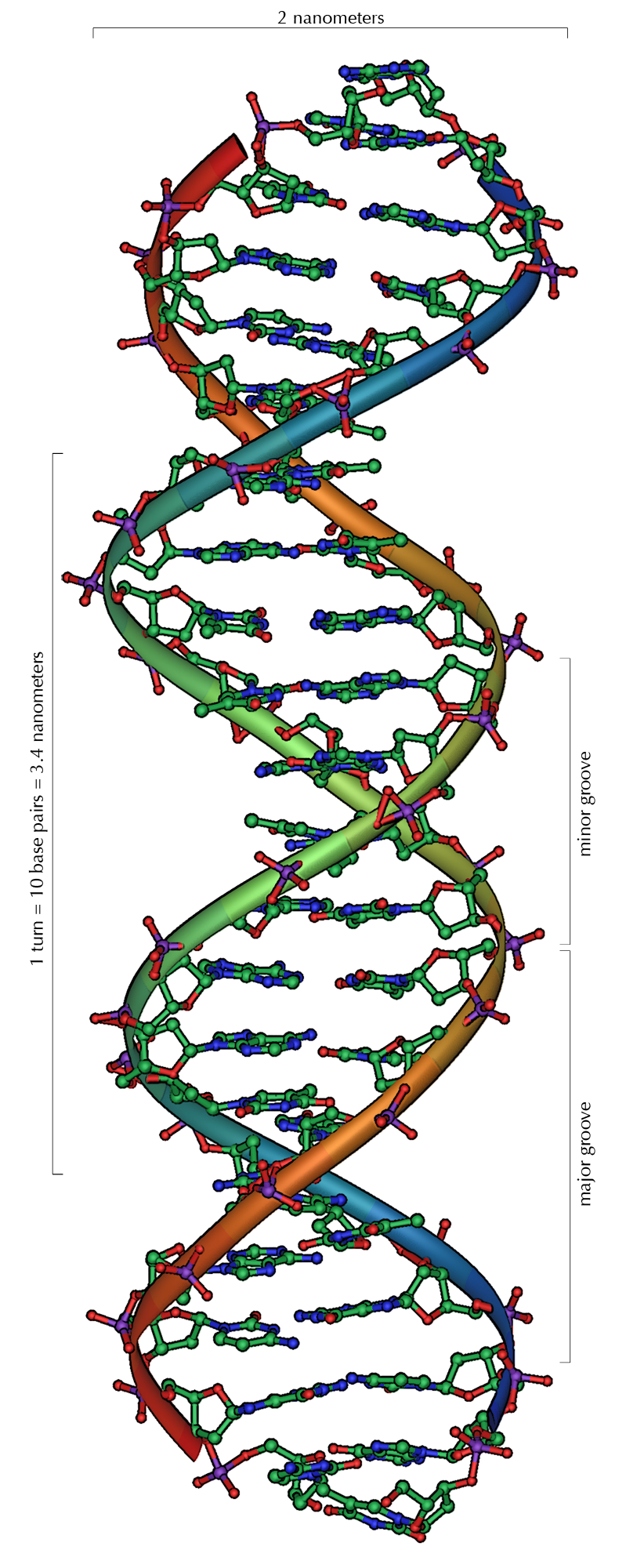

* On April 25, 1953James D. Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper proposing the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. Watson, Crick and ...

and Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

published "a radically different structure" for DNA, thereby founding the field of molecular genetics

Molecular genetics is a sub-field of biology that addresses how differences in the structures or expression of DNA molecules manifests as variation among organisms. Molecular genetics often applies an "investigative approach" to determine the ...

. Their structural model featured two strands of complementary

A complement is something that completes something else.

Complement may refer specifically to:

The arts

* Complement (music), an interval that, when added to another, spans an octave

** Aggregate complementation, the separation of pitch-class ...

base-paired DNA, running in opposite directions as a double helix. They concluded their report saying that "It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material". For this insight they were awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1962.

* Starting in the mid-1950s, Arthur Kornberg

Arthur Kornberg (March 3, 1918 – October 26, 2007) was an American biochemist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959 for the discovery of "the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic aci ...

began to study the mechanism of DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

. By 1957 he has identified the first DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create ...

. The enzyme was limited, creating DNA in just one direction and requiring an existing primer

Primer may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Primer'' (film), a 2004 feature film written and directed by Shane Carruth

* ''Primer'' (video), a documentary about the funk band Living Colour

Literature

* Primer (textbook), a t ...

to initiate copying of the template strand. Overall, the DNA replication process is surprisingly complex, requiring separate proteins to open

Open or OPEN may refer to:

Music

* Open (band), Australian pop/rock band

* The Open (band), English indie rock band

* ''Open'' (Blues Image album), 1969

* ''Open'' (Gotthard album), 1999

* ''Open'' (Cowboy Junkies album), 2001

* ''Open'' (YF ...

the DNA helix, to keep

A keep (from the Middle English ''kype'') is a type of fortified tower built within castles during the Middle Ages by European nobility. Scholars have debated the scope of the word ''keep'', but usually consider it to refer to large towers in c ...

it open, to create primers, to synthesize new DNA, to remove the primers, and to tie

Tie has two principal meanings:

* Tie (draw), a finish to a competition with identical results, particularly sports

* Necktie, a long piece of cloth worn around the neck or shoulders

Tie or TIE may also refer to:

Engineering and technology

* Ti ...

the pieces all together. Kornberg was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1959.

* In the early 1960s H. Gobind Khorana

Har Gobind Khorana (9 January 1922 – 9 November 2011) was an Indian American biochemist. While on the faculty of the University of Wisconsin–Madison, he shared the 1968 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine with Marshall W. Nirenberg an ...

made significant advances in the elucidation of the genetic code

The genetic code is the set of rules used by living cells to translate information encoded within genetic material ( DNA or RNA sequences of nucleotide triplets, or codons) into proteins. Translation is accomplished by the ribosome, which links ...

. Afterwards, he initiated a large project to totally synthesize a functional human gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "...Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ba ...

. To achieve this, Khorana pioneered many of the techniques needed to make and use synthetic Synthetic things are composed of multiple parts, often with the implication that they are artificial. In particular, 'synthetic' may refer to:

Science

* Synthetic chemical or compound, produced by the process of chemical synthesis

* Synthetic o ...

DNA oligonucleotide

Oligonucleotides are short DNA or RNA molecules, oligomers, that have a wide range of applications in genetic testing, research, and forensics. Commonly made in the laboratory by solid-phase chemical synthesis, these small bits of nucleic acids c ...

s. Sequence-specific oligonucleotides were used both as building blocks for the gene, and as primers and templates for DNA polymerase. In 1968 Khorana was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

for his work on the Genetic Code.

* In 1969 Thomas D. Brock

Thomas Dale Brock (September 10, 1926 – April 4, 2021) was an American microbiologist known for his discovery of hyperthermophiles living in Geothermal areas of Yellowstone, hot springs at Yellowstone National Park. In the late 1960s, Brock di ...

reported the isolation of a new species of bacterium

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among ...

from a hot spring

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a spring produced by the emergence of geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow bodies of magma (molten rock) or by circ ...

in Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

. ''Thermus aquaticus

''Thermus aquaticus'' is a species of bacteria that can tolerate high temperatures, one of several thermophilic bacteria that belong to the ''Deinococcota'' phylum. It is the source of the heat-resistant enzyme ''Taq'' DNA polymerase, one of th ...

'' (Taq) became a standard source of enzymes able to withstand higher temperatures than those from ''E. coli

''Escherichia coli'' (),Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. also known as ''E. coli'' (), is a Gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escher ...

''.

* In 1970 Klenow reported a modified version of DNA Polymerase I from ''E. coli''. Treatment with a protease removed the 'forward' nuclease activity of this enzyme. The overall activity of the resulting Klenow fragment

The Klenow fragment is a large protein fragment produced when DNA polymerase I from '' E. coli'' is enzymatically cleaved by the protease subtilisin. First reported in 1970, it retains the 5' → 3' polymerase activity and the 3’ → 5’ ex ...

is therefore biased towards the synthesis of DNA, rather than its degradation.

* By 1971 researchers in Khorana's project, concerned over their yields of DNA, began looking at "repair synthesis" – an artificial system of primers and templates that allows DNA polymerase to copy segments of the gene they are synthesizing. Although similar to PCR in using repeated applications of DNA polymerase, the process they usually describePanet A, Khorana HG "Studies on Polynucleotides" J. Biol. Chem. vol. 249(16), pp. 5213–21 (1974). employs just a single primer-template complex, and therefore would not lead to the exponential amplification seen in PCR.

* Circa 1971 Kjell Kleppe

Kjell Kleppe (1934-1988) was a Norwegian biochemist and molecular biologist who was a pioneer in the PCR technique and built the first laboratory in the country for bio and gene technology.

Kjell Kleppe earned a B.S. degree from the University of ...

, a researcher in Khorana's lab, envisioned a process very similar to PCR. At the end of a paper on the earlier technique,Kleppe K, Ohtsuka E, Kleppe R, Molineux I, Khorana HG "Studies on polynucleotides. XCVI. Repair replications of short synthetic DNA's as catalyzed by DNA polymerases." J. Molec. Biol. vol. 56, pp. 341–61 (1971). he described how a two-primer system might lead to replication of a specific segment of DNA:

:::one would hope to obtain two structures, each containing the full length of the template strand appropriately complexed with the primer. DNA polymerase will be added to complete the process of repair replication. Two molecules of the original duplex should result. The whole cycle could be repeated, there being added every time a fresh dose of the enzyme.:No results are shown there, and the mention of unpublished experiments in another paper may (or may not) refer to the two-primer replication system. (These early precursors to PCR were carefully scrutinized in a patent lawsuit, and are discussed in Mullis' chapters in ''The Polymerase Chain Reaction'' (1994).) * Also in 1971,

Cetus Corporation

Cetus Corporation was one of the first biotechnology companies. It was established in Berkeley, California, in 1971, but conducted most of its operations in nearby Emeryville. Before merging with Chiron Corporation in 1991 (now a part of Novarti ...

was founded in Berkeley, California

Berkeley ( ) is a city on the eastern shore of San Francisco Bay in northern Alameda County, California, United States. It is named after the 18th-century Irish bishop and philosopher George Berkeley. It borders the cities of Oakland and Emer ...

, by Ronald Cape, Peter Farley, and Donald Glaser. Initially the company screened for microorganisms capable of producing components used in the manufacture of food, chemicals, vaccines, or pharmaceuticals. After moving to nearby Emeryville Emeryville may refer to:

* Emeryville, California

Emeryville is a city located in northwest Alameda County, California, in the United States. It lies in a corridor between the cities of Berkeley and Oakland, with a border on the shore of San ...

, they began projects involving the new biotechnology

Biotechnology is the integration of natural sciences and engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms, cells, parts thereof and molecular analogues for products and services. The term ''biotechnology'' was first used b ...

industry, primarily the cloning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, cl ...

and expression

Expression may refer to:

Linguistics

* Expression (linguistics), a word, phrase, or sentence

* Fixed expression, a form of words with a specific meaning

* Idiom, a type of fixed expression

* Metaphorical expression, a particular word, phrase, o ...

of human genes, but also the development of diagnostic tests for genetic mutations.

* In 1976 a DNA polymerase

A DNA polymerase is a member of a family of enzymes that catalyze the synthesis of DNA molecules from nucleoside triphosphates, the molecular precursors of DNA. These enzymes are essential for DNA replication and usually work in groups to create ...

Chien A, Edgar DB, Trela JM "Deoxyribonucleic acid polymerase from the extreme thermophile Thermus aquaticus" J. Bacteriol. vol. 174 pp. 1550–1557 (1976). was isolated from ''T. aquaticus''. It was found to retain its activity at temperatures above 75 °C.

* In 1977 Frederick Sanger

Frederick Sanger (; 13 August 1918 – 19 November 2013) was an English biochemist who received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry twice.

He won the 1958 Chemistry Prize for determining the amino acid sequence of insulin and numerous other p ...

reported a method

Method ( grc, μέθοδος, methodos) literally means a pursuit of knowledge, investigation, mode of prosecuting such inquiry, or system. In recent centuries it more often means a prescribed process for completing a task. It may refer to:

*Scien ...

for determining the sequence of DNA. The technique employed an oligonucleotide primer

Primer may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Primer'' (film), a 2004 feature film written and directed by Shane Carruth

* ''Primer'' (video), a documentary about the funk band Living Colour

Literature

* Primer (textbook), a t ...

, DNA polymerase, and modified nucleotide precursors that block further extension of the primer in sequence-dependent manner. For this innovation he was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in 1980.

By 1980 all of the components needed to perform PCR amplification were known to the scientific community. The use of DNA polymerase to extend oligonucleotide primers was a common procedure in DNA sequencing and the production of cDNA

In genetics, complementary DNA (cDNA) is DNA synthesized from a single-stranded RNA (e.g., messenger RNA (mRNA) or microRNA (miRNA)) template in a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme reverse transcriptase. cDNA is often used to express a speci ...

for cloning

Cloning is the process of producing individual organisms with identical or virtually identical DNA, either by natural or artificial means. In nature, some organisms produce clones through asexual reproduction. In the field of biotechnology, cl ...

and expression

Expression may refer to:

Linguistics

* Expression (linguistics), a word, phrase, or sentence

* Fixed expression, a form of words with a specific meaning

* Idiom, a type of fixed expression

* Metaphorical expression, a particular word, phrase, o ...

. The use of DNA polymerase for nick translation

Nick translation (or head translation), developed in 1977 by Peter Rigby and Paul Berg, is a tagging technique in molecular biology in which DNA Polymerase I is used to replace some of the nucleotides of a DNA sequence with their labeled analogu ...

was the most common method used to label DNA probes

In molecular biology, a hybridization probe (HP) is a fragment of DNA or RNA of usually 15–10000 nucleotide long which can be radioactively or fluorescently labeled. HP can be used to detect the presence of nucleotide sequences in analyzed RNA ...

for Southern blot

A Southern blot is a method used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detecti ...

ting.

Theme

* In 1979Cetus Corporation

Cetus Corporation was one of the first biotechnology companies. It was established in Berkeley, California, in 1971, but conducted most of its operations in nearby Emeryville. Before merging with Chiron Corporation in 1991 (now a part of Novarti ...

hired Kary Mullis

Kary Banks Mullis (December 28, 1944August 7, 2019) was an American biochemist. In recognition of his role in the invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, he shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Michael Smith and wa ...

to synthesize oligonucleotides for various research and development projects throughout the company.Mullis KB "The Unusual Origins of the Polymerase Chain Reaction" Scientific American, vol. 262, pp. 56–65 (April 1990). These oligos were used as probes for screening cloned genes, as primers for DNA sequencing and cDNA synthesis, and as building blocks for gene construction. Originally synthesizing these oligos by hand, Mullis later evaluated early prototypes for automated synthesizers.

* By May 1983 Mullis synthesized oligonucleotide probes for a project at Cetus to analyze a sickle cell anemia

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a group of blood disorders typically inherited from a person's parents. The most common type is known as sickle cell anaemia. It results in an abnormality in the oxygen-carrying protein haemoglobin found in red blo ...

mutation. Hearing of problems with their work, Mullis proposed an alternative technique based on Sanger's DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Th ...

method. Realizing the difficulty in making the Sanger method specific to a single location in the genome, Mullis then modified the idea to add a second primer on the opposite strand. Repeated applications of polymerase could lead to a chain reaction of replication for a specific segment of the genome – PCR.

* Later in 1983 Mullis began to test his idea. His first experiment did not involve thermal cycling – he hoped that the polymerase could perform continued replication on its own. Later experiments that year included repeated thermal cycling, and targeted small segments of a cloned gene. Mullis considered these experiments a success, but could not convince other researchers.

* In June 1984 Cetus held its annual meeting in Monterey, California

Monterey (; es, Monterrey; Ohlone: ) is a city located in Monterey County on the southern edge of Monterey Bay on the U.S. state of California's Central Coast. Founded on June 3, 1770, it functioned as the capital of Alta California under bo ...

. Its scientists and consultants presented their results, and considered future projects. Mullis presented a poster on the production of oligonucleotides by his laboratory, and presented some of the results from his experiments with PCR. Only Joshua Lederberg

Joshua () or Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' lit. 'Yahweh is salvation') ''Yēšūaʿ''; syr, ܝܫܘܥ ܒܪ ܢܘܢ ''Yəšūʿ bar Nōn''; el, Ἰησοῦς, ar , يُوشَعُ ٱبْنُ نُونٍ '' Yūšaʿ ...

, a Cetus consultant, showed any interest. Later at the meeting, Mullis was involved in a physical altercation with another Cetus researcher over a dispute unrelated to PCR. The other scientist left the company, and Mullis was removed as head of the oligo synthesis lab.

Development

* In September 1984 Tom White, VP of Research at Cetus (and a close friend), pressured Mullis to take his idea to the group developing the genetic mutation assay. Together, they spent the following months designing experiments that could convincingly show that PCR is working on genomic DNA. Unfortunately, the expected amplification product was not visible inagarose gel electrophoresis

Agarose gel electrophoresis is a method of gel electrophoresis used in biochemistry, molecular biology, genetics, and clinical chemistry to separate a mixed population of macromolecules such as DNA or proteins in a matrix of agarose, one of the ...

, leading to confusion as to whether the reaction was specific to the targeted region.

* In November 1984 the amplification products were analyzed by Southern blot

A Southern blot is a method used in molecular biology for detection of a specific DNA sequence in DNA samples. Southern blotting combines transfer of electrophoresis-separated DNA fragments to a filter membrane and subsequent fragment detecti ...

ting, which clearly demonstrated increasing amounts of the expected 110 bp DNA product.Saiki RK et al. "Enzymatic Amplification of β-globin Genomic Sequences and Restriction Site Analysis for Diagnosis of Sickle Cell Anemia" Science vol. 230 pp. 1350–54 (1985). Having the first visible signal, the researchers began optimizing the process. Later, the amplified products were cloned and sequenced, showing that most of the amplified DNA was the desired target, and that the Klenow fragment

The Klenow fragment is a large protein fragment produced when DNA polymerase I from '' E. coli'' is enzymatically cleaved by the protease subtilisin. First reported in 1970, it retains the 5' → 3' polymerase activity and the 3’ → 5’ ex ...

then being used only rarely incorporated incorrect nucleotides during replication.

Exposition

* Following normal industrial practice, Mullis applied for apatent

A patent is a type of intellectual property that gives its owner the legal right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention for a limited period of time in exchange for publishing an enabling disclosure of the invention."A p ...

covering the basic idea of PCR and many potential applications, and was asked by the PTO to include more results. On March 28, 1985, Mullis' development group filed an application focused on the analysis of the sickle cell anemia mutation via PCR and Oligomer restriction Oligomer Restriction (abbreviated OR) is a procedure to detect an altered DNA sequence in a genome. A labeled oligonucleotide probe is hybridized to a target DNA, and then treated with a restriction enzyme. If the probe exactly matches the target ...

. After modification, both patents were approved on July 28, 1987.

* In the spring of 1985 the development group began to apply the PCR technique to other targets. Primers and probes were designed for a variable segment of the Human leukocyte antigen

The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system or complex is a complex of genes on chromosome 6 in humans which encode cell-surface proteins responsible for the regulation of the immune system. The HLA system is also known as the human version of th ...

DQα gene. This reaction was much more specific than that for the β-hemoglobin target – the expected PCR product is directly visible on agarose gel electrophoresis

Agarose gel electrophoresis is a method of gel electrophoresis used in biochemistry, molecular biology, genetics, and clinical chemistry to separate a mixed population of macromolecules such as DNA or proteins in a matrix of agarose, one of the ...

. The amplification products from various sources were also cloned and sequenced, the first determination of new alleles by PCR. At the same time the original Oligomer Restriction assay technique was replaced with the more general Allele specific oligonucleotide An allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) is a short piece of synthetic DNA complementary to the sequence of a variable target DNA. It acts as a probe for the presence of the target in a Southern blot assay or, more commonly, in the simpler Dot bl ...

method.Saiki et al. "Analysis of enzymatically amplified β-globin and HLA DQα DNA with allele-specific oligonucleotide probes." Nature vol. 324 (6093) pp. 163–6 (1986).

* Also early in 1985, the group began using a thermostable DNA polymerase (the enzyme

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecules known as products. A ...

used in the original reaction is destroyed at each heating step). At the time only two had been described, from Taq Taq may refer to:

* Taq, Iran, a village in Semnan Province, Iran

* ''Taq'' polymerase, a heat-stable enzyme used in polymerase chain reaction, or ''Thermus aquaticus'', the species of bacteria from which the polymerase is naturally derived

* The ...

and Bst. The report on Taq polymerase was more detailed, so it was chosen for testing. The Bst polymerase was later found to be unsuitable for PCR. That summer Mullis attempted to isolate the enzyme, and a group outside of Cetus was contracted to make it, all without success. In the Fall of 1985 Susanne Stoffel and David Gelfand at Cetus succeed in making the polymerase, and it was immediately found by Randy Saiki to support the PCR process.

* With patents submitted, work proceeded to report PCR to the general scientific community. An abstract for an American Society of Human Genetics

The American Society of Human Genetics (ASHG), founded in 1948, is a professional membership organization for specialists in human genetics. As of 2009, the organization had approximately 8,000 members. The Society's members include researchers, a ...

meeting in Salt Lake City

Salt Lake City (often shortened to Salt Lake and abbreviated as SLC) is the Capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Utah, most populous city of Utah, United States. It is the county seat, seat of Salt Lake County, Utah, Sal ...

was submitted in April 1985, and the first announcement of PCR was made there by Saiki in October. Two publications were planned – an 'idea' paper from Mullis, and an 'application' paper from the entire development group. Mullis submitted his manuscript to the journal Nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physics, physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomenon, phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. ...

, which rejected it for not including results. The other paper, mainly describing the OR analysis assay, was submitted to ''Science'' on September 20, 1985, and was accepted in November. After the rejection of Mullis' report in December, details on the PCR process were hastily added to the second paper, which appears on December 20, 1985.

* In May 1986 Mullis presented PCR at the Cold Spring Harbor Symposium, and published a modified version of his original 'idea' manuscript much later. The first non-Cetus report using PCR was submitted on September 5, 1986, indicating how quickly other laboratories began implementing the technique. The Cetus development group published their detailed sequence analysis of PCR products on September 8, 1986, and their use of ASO probes on November 13, 1986.

* The use of Taq polymerase in PCR was announced by Henry Erlich at a meeting

A meeting is when two or more people come together to discuss one or more topics, often in a formal or business setting, but meetings also occur in a variety of other environments. Meetings can be used as form of group decision making.

Defini ...

in Berlin on September 20, 1986, submitted for publication in October 1987, and was published early the next year'.Saiki et al. "Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase." Science vol. 239 pp. 487–91 (1988). The patent for PCR with Taq polymerase was filed on June 17, 1987, and was issued on October 23, 1990.

Variation

In December 1985 a joint venture between Cetus andPerkin-Elmer

PerkinElmer, Inc., previously styled Perkin-Elmer, is an American global corporation focused in the business areas of diagnostics, life science research, food, environmental and industrial testing. Its capabilities include detection, imaging, inf ...

was established to develop instruments and reagents for PCR. Complex thermal cycler

The thermal cycler (also known as a thermocycler, PCR machine or DNA amplifier) is a laboratory apparatus most commonly used to amplify segments of DNA via the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Thermal cyclers may also be used in laboratories to fa ...

s were constructed to perform the Klenow-based amplifications, but never marketed. Simpler machines for Taq-based PCR were developed, and on November 19, 1987, a press release announces the commercial availability of the "PCR-1000 Thermal Cycler" and "AmpliTaq DNA Polymerase".

In the spring of 1985 John Sninsky at Cetus began to use PCR for the difficult task of measuring the amount of HIV circulating in blood. A viable test was announced on April 11, 1986, and published in May 1987. Donated blood could then be screened for the virus, and the effect of antiviral drugs directly monitored.

In 1985 Norm Arnheim, also a member of the development team, concluded his sabbatical at Cetus and assumed an academic position at University of Southern California

The University of Southern California (USC, SC, or Southern Cal) is a Private university, private research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Founded in 1880 by Robert M. Widney, it is the oldest private research university in C ...

. He began to investigate the use of PCR to amplify samples containing just a single copy of the target sequence. By 1989 his lab developed multiplex-PCR on single sperm to directly analyze the products of meiotic recombination. These single-copy amplifications, which had first been run during the characterization of Taq polymerase, became vital to the study of ancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient specimens. Due to degradation processes (including cross-linking, deamination and fragmentation) ancient DNA is more degraded in comparison with contemporary genetic material. Even under the bes ...

, as well as the genetic typing of preimplanted embryos.

In 1986 Edward Blake, a forensics scientist working in the Cetus building, collaborated with Henry Erlich a researcher at Cetus, to apply PCR to the analysis of criminal evidence. A panel of DNA samples from old cases was collected and coded, and was analyzed blind by Saiki using the HLA DQα assay. When the code was broken, all of the evidence and perpetrators matched. Blake and Erlich's group used the technique almost immediately in ''Pennsylvania v. Pestinikas'', the first use of PCR in a criminal case. This DQα test is developed by Cetus as one of their "Ampli-Type" kits, and became part of early protocols for the testing of forensic evidence, such as in the O. J. Simpson murder case

''The People of the State of California v. Orenthal James Simpson'' was a criminal trial in Los Angeles County Superior Court starting in 1994, in which O. J. Simpson, a former National Football League (NFL) player, broadcaster and actor, was ...

.

By 1989 Alec Jeffreys

Sir Alec John Jeffreys, (born 9 January 1950) is a British geneticist known for developing techniques for genetic fingerprinting and DNA profiling which are now used worldwide in forensic science to assist police detective work and to resolv ...

, who had earlier developed and applied the first DNA Fingerprinting

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's DNA characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is called DNA barcoding.

DNA profiling is a forensic tec ...

tests, used PCR to increase their sensitivity. With further modification, the amplification of highly polymorphic Variable number tandem repeat

A variable number tandem repeat (or VNTR) is a location in a genome where a short nucleotide sequence is organized as a tandem repeat. These can be found on many chromosomes, and often show variations in length (number of repeats) among individua ...

(VNTR) loci became the standard protocol for National DNA Database

A DNA database or DNA databank is a database of DNA profiles which can be used in the analysis of genetic diseases, genetic fingerprinting for criminology, or genetic genealogy. DNA databases may be public or private, the largest ones being nat ...

s such as Combined DNA Index System

The Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) is the United States national DNA database created and maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation. CODIS consists of three levels of information; Local DNA Index Systems (LDIS) where DNA profiles orig ...

(CODIS).

In 1987 Russ Higuchi succeeded in amplifying DNA from a human hair. This work expanded to develop methods for the amplification of DNA from highly degraded samples, such as from ancient DNA

Ancient DNA (aDNA) is DNA isolated from ancient specimens. Due to degradation processes (including cross-linking, deamination and fragmentation) ancient DNA is more degraded in comparison with contemporary genetic material. Even under the bes ...

and in forensic

Forensic science, also known as criminalistics, is the application of science to Criminal law, criminal and Civil law (legal system), civil laws, mainly—on the criminal side—during criminal investigation, as governed by the legal standard ...

evidence.

Coda

* On December 22, 1989, the journal ''Science'' awarded Taq Polymerase (and PCR) its first "Molecule of the Year". The 'Taq PCR' paper became for several years the mostcited

A citation is a reference to a source. More precisely, a citation is an abbreviated alphanumeric expression embedded in the body of an intellectual work that denotes an entry in the bibliographic references section of the work for the purpose of ...

publication in biology.

* After the publication of the first PCR paper, the United States Government

The federal government of the United States (U.S. federal government or U.S. government) is the national government of the United States, a federal republic located primarily in North America, composed of 50 states, a city within a fede ...

sent a stern letter to Randy Saiki, admonishing him for publishing a report on "chain reactions" without the required prior review and approval by the U.S. Department of Energy

The United States Department of Energy (DOE) is an executive department of the U.S. federal government that oversees U.S. national energy policy and manages the research and development of nuclear power and nuclear weapons in the United States. ...

. Cetus responded, explaining the differences between PCR and the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

.

* On July 23, 1991, Cetus announced that its sale to the neighboring biotechnology company Chiron

In Greek mythology, Chiron ( ; also Cheiron or Kheiron; ) was held to be the superlative centaur amongst his brethren since he was called the "wisest and justest of all the centaurs".

Biography

Chiron was notable throughout Greek mythology ...

. As part of the sale, rights to the PCR patents were sold for US$300 million to Hoffman-La Roche

F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG, commonly known as Roche, is a Swiss multinational healthcare company that operates worldwide under two divisions: Pharmaceuticals and Diagnostics. Its holding company, Roche Holding AG, has shares listed on the SIX S ...

(who in 1989 had bought limited rights to PCR). Many of the Cetus PCR researchers moved to the Roche subsidiary, Roche Molecular Systems.

* On October 13, 1993, Kary Mullis

Kary Banks Mullis (December 28, 1944August 7, 2019) was an American biochemist. In recognition of his role in the invention of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) technique, he shared the 1993 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Michael Smith and wa ...

, who had left Cetus in 1986, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

. On the morning of his acceptance speech, he was nearly arrested by Swedish authorities for the "inappropriate use of a laser pointer".Mullis KB "Dancing Naked in the Mind Field" Pantheon Books (1998)

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Polymerase Chain ReactionPolymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) t ...

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a method widely used to rapidly make millions to billions of copies (complete or partial) of a specific DNA sample, allowing scientists to take a very small sample of DNA and amplify it (or a part of it) t ...