History of Nebraska on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of the U.S.

The history of the U.S.

, Twin Cities Development Corporation. Retrieved 8/30/07. Animals occupying the state during this period included

During the last

During the last

Several explorers from across Europe explored the lands that became Nebraska. In 1682,

Several explorers from across Europe explored the lands that became Nebraska. In 1682,

The

The

The

The

online edition

* Hickey, Donald R. et al. ''Nebraska Moments'' (U. of Nebraska Press, 2007), 39 short historical essays; 403pp; * Luebke, Frederick C. ''Nebraska: An Illustrated History'' (1995) * Morton, J. Sterling, ed. ''Illustrated History of Nebraska: A History of Nebraska from the Earliest Explorations of the Trans-Mississippi Region.'' 3 vols. (1905–13

online free vol 1

* Naugle, Ronald C., John J. Montag, and James C. Olson. ''History of Nebraska'' (4th ed. U of Nebraska Press, 2015). 568 pp

online review

** older editions: Olson, James C, and Ronald C. Naugle. ''History of Nebraska'' (3rd ed. University of Nebraska Press, 1997) 506pp * Sheldon, Addison Erwin. ''Nebraska: The Land and the People''. (3 vols. 1931). old detailed narrative, with biographies * Wishart, David J. ''Encyclopedia of the Great Plains'' (2004

excerpt

in JSTOR

* Berens; Charlyne. ''Chuck Hagel: Moving Forward'' (U. of Nebraska Press, 2006) GOP senator 1997–2008 * Cherny, Robert W. ''Populism, Progressivism and the Transformation of Nebraska Politics, 1885–1915'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1981) * Folsom, Burton W. "Tinkerers, tipplers, and traitors: ethnicity and democratic reform in Nebraska during the Progressive era." ''Pacific Historical Review'' 50.1 (1981): 53-75

online

* Folsom, Burton W, Jr. ''No More Free Markets or Free Beer: The Progressive Era in Nebraska, 1900–1924'' (1999). * Lowitt Richard. ''George W. Norris'' (3 vols. 1963–75), emphasis on national role * Luebke Frederick C. ''Immigrants and Politics: The Germans of Nebraska, 1880–1900'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1969). * Olson James C. ''J. Sterling Morton'' (U. of Nebraska Press, 1942). * Parsons Stanley B, Jr. ''The Populist Context: Rural versus Urban Power on a Great Plains Frontier'' (Greenwood Press, 1973). * Pederson James F, and Kenneth D. Wald. ''Shall the People Rule? A History of the Democratic Party in Nebraska Politics, 1854–1972'' (Lincoln: Jacob North, 1972). * Potter, James E. ''Standing Firmly by the Flag: Nebraska Territory and the Civil War, 1861–1867'' (University of Nebraska Press, 2012) 375 pp.

online free to borrow

* Dick, Everett. ''Vanguards of the frontier : a social history of the northern plains and Rocky Mountains from the fur traders to the sod busters'' (1941

online free to borrow

* Fink, Deborah. ''Agrarian Women: Wives and Mothers in Rural Nebraska, 1880–1940'' (1992) * Hurt, R. Douglas. ''The Great Plains During World War II'' (2008), 524pp * Meyering; Sheryl L. ''Understanding O Pioneers! and My Antonia: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historical Documents'' (Greenwood Press, 2002) * Pound, Louise. ''Nebraska Folklore'' (1913) (reprint University of Nebraska Press, 2006)

online review

* Aucoin; James. ''Water in Nebraska: Use, Politics, Policies'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1984) * Lavin, Stephen J. et al. ''Atlas of the Great Plains'' (U of Nebraska Press, 2011

excerpt

* Lonsdale, Richard E. ''Economic Atlas of Nebraska'' (1977) * Williams, James H, and Doug Murfield. ''Agricultural Atlas of Nebraska'' (1977)

''Nebraska Studies'': Archival photos, documents, letters, video segments, maps, and more ─ capturing the life and history of Nebraska from pre-1500 to present

* {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Nebraska Great Plains

The history of the U.S.

The history of the U.S. state

State may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Literature

* ''State Magazine'', a monthly magazine published by the U.S. Department of State

* ''The State'' (newspaper), a daily newspaper in Columbia, South Carolina, United States

* ''Our S ...

of Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

dates back to its formation as a territory

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

by the Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

, passed by the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

on May 30, 1854. The Nebraska Territory

The Territory of Nebraska was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 30, 1854, until March 1, 1867, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Nebraska. The Nebraska ...

was settled extensively under the Homestead Act of 1862

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of th ...

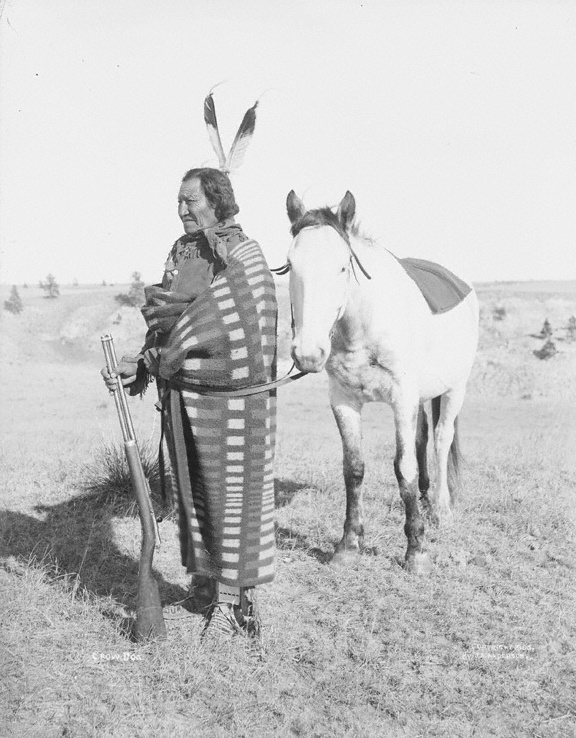

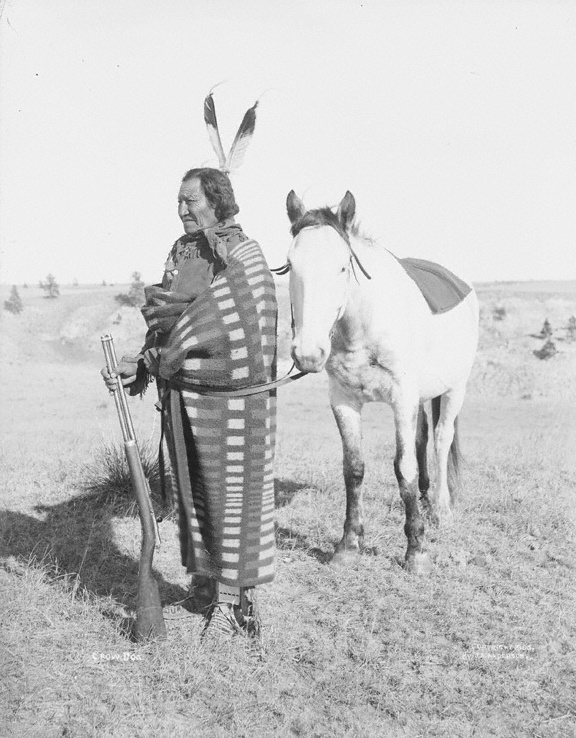

during the 1860s, and in 1867 was admitted to the Union as the 37th U.S. state. The Plains Indians are the descendants of a long line of succeeding cultures of indigenous peoples in Nebraska who occupied the area for thousands of years before European arrival and continue to do so today.

Pre-historic

Mesozoic

During theLate Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the younger of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''creta'', the ...

, between 66 million to 99 million years ago, three-quarters of Nebraska was covered by the Western Interior Seaway

The Western Interior Seaway (also called the Cretaceous Seaway, the Niobraran Sea, the North American Inland Sea, and the Western Interior Sea) was a large inland sea that split the continent of North America into two landmasses. The ancient sea, ...

, a large body of water that covered one-third of the United States. The sea was occupied by mosasaur

Mosasaurs (from Latin ''Mosa'' meaning the 'Meuse', and Greek ' meaning 'lizard') comprise a group of extinct, large marine reptiles from the Late Cretaceous. Their first fossil remains were discovered in a limestone quarry at Maastricht on th ...

s, ichthyosaurs

Ichthyosaurs (Ancient Greek for "fish lizard" – and ) are large extinct marine reptiles. Ichthyosaurs belong to the order known as Ichthyosauria or Ichthyopterygia ('fish flippers' – a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1842, alt ...

, and plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria (; Greek: πλησίος, ''plesios'', meaning "near to" and ''sauros'', meaning "lizard") or plesiosaurs are an order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared ...

s. Additionally, shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimo ...

s such as ''Squalicorax

''Squalicorax'', commonly known as the crow shark, is a genus of extinct lamniform shark known to have lived during the Cretaceous period. The genus had a global distribution in the Late Cretaceous epoch. Multiple species within this genus are c ...

'', and fish such as '' Pachyrhizodus'', ''Enchodus

''Enchodus'' (from el, ἔγχος , 'spear' and el, ὀδούς 'tooth') is an extinct genus of aulopiform ray-finned fish related to lancetfish and lizardfish. Species of ''Enchodus'' flourished during the Late Cretaceous, and survived the ...

'', and the ''Xiphactinus

''Xiphactinus'' (from Latin and Greek for " sword-ray") is an extinct genus of large (Shimada, Kenshu, and Michael J. Everhart. "Shark-bitten Xiphactinus audax (Teleostei: Ichthyodectiformes) from the Niobrara Chalk (Upper Cretaceous) of Kansas. ...

'', a fish larger than any modern bony fish, occupied the sea. Other sea life included invertebrate

Invertebrates are a paraphyletic group of animals that neither possess nor develop a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''backbone'' or ''spine''), derived from the notochord. This is a grouping including all animals apart from the chordate ...

s such as mollusk

Mollusca is the second-largest phylum of invertebrate animals after the Arthropoda, the members of which are known as molluscs or mollusks (). Around 85,000 extant species of molluscs are recognized. The number of fossil species is e ...

s, ammonites

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

, squid-like belemnite

Belemnitida (or the belemnite) is an extinct order of squid-like cephalopods that existed from the Late Triassic to Late Cretaceous. Unlike squid, belemnites had an internal skeleton that made up the cone. The parts are, from the arms-most to ...

s, and plankton

Plankton are the diverse collection of organisms found in Hydrosphere, water (or atmosphere, air) that are unable to propel themselves against a Ocean current, current (or wind). The individual organisms constituting plankton are called plankt ...

. Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of an animal. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is the stable outer shell of an organism, the endoskeleton, which forms the support structure inside ...

s of these animals and period plants were embedded in mud that hardened into rock and became the limestone that appears today on the sides of ravines and along the streams of Nebraska.

Cenozoic

Pliocene

As the sea bottom slowly rose,marsh

A marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous rather than woody plant species.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p Marshes can often be found at ...

es and forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

s appeared. After thousands of years the land became drier, and trees of all kinds grew, including oak

An oak is a tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' (; Latin "oak tree") of the beech family, Fagaceae. There are approximately 500 extant species of oaks. The common name "oak" also appears in the names of species in related genera, notably ''L ...

, maple

''Acer'' () is a genus of trees and shrubs commonly known as maples. The genus is placed in the family Sapindaceae.Stevens, P. F. (2001 onwards). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 9, June 2008 nd more or less continuously updated since http ...

, beech

Beech (''Fagus'') is a genus of deciduous trees in the family Fagaceae, native to temperate Europe, Asia, and North America. Recent classifications recognize 10 to 13 species in two distinct subgenera, ''Engleriana'' and ''Fagus''. The ''Engle ...

and willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, from the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 400 speciesMabberley, D.J. 1997. The Plant Book, Cambridge University Press #2: Cambridge. of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist s ...

. Fossil leaves from ancient trees are found today in the state's red sandstone rocks."History of Nebraska", Twin Cities Development Corporation. Retrieved 8/30/07. Animals occupying the state during this period included

camel

A camel (from: la, camelus and grc-gre, κάμηλος (''kamēlos'') from Hebrew or Phoenician: גָמָל ''gāmāl''.) is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. C ...

s, tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk. Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South and Central America, with one species inhabit ...

s, monkey

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as the simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes, which constitutes an incomple ...

s, tiger

The tiger (''Panthera tigris'') is the largest living cat species and a member of the genus '' Panthera''. It is most recognisable for its dark vertical stripes on orange fur with a white underside. An apex predator, it primarily preys on u ...

s and rhinos. The state also had a variety of horses

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million yea ...

native to its lands.

Pleistocene

During the last

During the last ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gree ...

, continental ice sheets repeatedly covered eastern Nebraska. The exact timing that these glaciations occurred remain uncertain. Likely, they occurred between two million to 600,000 years ago. During the last two million years, the climate alternated between cold and warm phases, respectively called "glacial

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

" and "interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene in ...

" periods instead of a continuous ice age.Richmond, G.M. and D.S. Fullerton, 1986, ''Summation of Quaternary glaciations in the United States of America'', Quaternary Science Reviews. vol. 5, pp. 183–196. Clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4).

Clays develop plasticity when wet, due to a molecular film of water surrounding the clay par ...

ey tills and large boulder

In geology, a boulder (or rarely bowlder) is a rock fragment with size greater than in diameter. Smaller pieces are called cobbles and pebbles. While a boulder may be small enough to move or roll manually, others are extremely massive.

In c ...

s, called "glacial erratic

A glacial erratic is glacially deposited rock differing from the type of rock native to the area in which it rests. Erratics, which take their name from the Latin word ' ("to wander"), are carried by glacial ice, often over distances of hundred ...

s", were left on the hillsides during the period when ice sheets covered eastern Nebraska two or three times. During various periods of the remainder of the Pleistocene and into the Holocene, the glacial drift was buried by silty, wind-blown sediment called "loess

Loess (, ; from german: Löss ) is a clastic, predominantly silt-sized sediment that is formed by the accumulation of wind-blown dust. Ten percent of Earth's land area is covered by loess or similar deposits.

Loess is a periglacial or aeolian ...

".

Holocene (present-day)

As the climate became drier grassy plains appeared, rivers began to cut their present valleys, and present Nebraska topography was formed. Animals appearing during this period remain in the state to this day.European exploration: 1682–1853

Several explorers from across Europe explored the lands that became Nebraska. In 1682,

Several explorers from across Europe explored the lands that became Nebraska. In 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle (; November 22, 1643 – March 19, 1687), was a 17th-century French explorer and fur trader in North America. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, ...

claimed the area first when he named all the territory drained by the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

and its tributaries for France, naming it the Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

. In 1714, Etienne de Bourgmont traveled from the mouth of the Missouri River in Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

to the mouth of the Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itself ...

, which he called the Nebraskier River, becoming the first person to approximate the state's name.

In 1720, Spaniard Pedro de Villasur led an overland expedition that followed an Indian trail from Santa Fe to Nebraska. In a battle with the Pawnee Pawnee initially refers to a Native American people and its language:

* Pawnee people

* Pawnee language

Pawnee is also the name of several places in the United States:

* Pawnee, Illinois

* Pawnee, Kansas

* Pawnee, Missouri

* Pawnee City, Nebraska

* ...

, Villasur and 34 members of his party were killed near the juncture of the Loup and Platte River

The Platte River () is a major river in the State of Nebraska. It is about long; measured to its farthest source via its tributary, the North Platte River, it flows for over . The Platte River is a tributary of the Missouri River, which itself ...

s just south of present-day Columbus, Nebraska

Columbus is a city in and the county seat of Platte County, in the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. The population was 22,111 at the 2010 census. It is the 10th largest city in Nebraska, with 24,028 people as of the 2020 censu ...

. Marking a major defeat for Spanish control of the region, a monk was the only survivor from the party, apparently left alive as a warning to the colony of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

. With the goal of reaching Santa Fe by water, the pair of French-Canadian

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fr ...

explorers named Pierre and Paul Mallet reached the mouth of what they named the Platte River in 1739. They ended up following the south fork of the Platte into Colorado

Colorado (, other variants) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It encompasses most of the Southern Rocky Mountains, as well as the northeastern portion of the Colorado Plateau and the western edge of t ...

.

In 1762, by the Treaty of Fontainebleau after France's defeat by Great Britain in the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, France ceded its lands west of the Mississippi River to Spain, causing the future Nebraska to fall under the rule of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Am ...

, based in Mexico and the Southwest. In 1795 Jacques D'Eglise traveled the Missouri River Valley

The Missouri River Valley outlines the journey of the Missouri River from its headwaters where the Madison, Jefferson and Gallatin Rivers flow together in Montana to its confluence with the Mississippi River in the State of Missouri. At long th ...

on behalf of the Spanish crown. Searching for the elusive Northwest Passage

The Northwest Passage (NWP) is the sea route between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through the Arctic Ocean, along the northern coast of North America via waterways through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The eastern route along the Arct ...

, D'Eglise did not go any further than central North Dakota

North Dakota () is a U.S. state in the Upper Midwest, named after the Native Americans in the United States, indigenous Dakota people, Dakota Sioux. North Dakota is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Saskatchewan and Manitoba to the north a ...

.

Early European settlements

A group of St. Louis merchants, collectively known as the Missouri Company, funded a series of trading expeditions along the Missouri river. In 1794, Jean-Baptiste Truteau established a trading post 30 miles up theNiobrara River

The Niobrara River (; oma, Ní Ubthátha khe, , literally "water spread-out horizontal-the" or "The Wide-Spreading Water") is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long,U.S. Geological Survey. Many early settlers, such as Mari Sando ...

. A Scotsman

The Scots ( sco, Scots Fowk; gd, Albannaich) are an ethnic group and nation native to Scotland. Historically, they emerged in the early Middle Ages from an amalgamation of two Celtic-speaking peoples, the Picts and Gaels, who founded t ...

named John McKay established a trading post on the west bank of the Missouri River in 1795. The post called Fort Charles was located south of present-day Dakota City, Nebraska

Dakota City is a city in Dakota County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 1,919 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Dakota County. Tyson Foods' largest beef production plant is located in Dakota City.

History

Dakota City was p ...

.

In 1803, the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory

The Territory of Louisiana or Louisiana Territory was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from July 4, 1805, until June 4, 1812, when it was renamed the Missouri Territory. The territory was formed out of the ...

from France for $15,000,000. What became Nebraska was under the "rule" of the United States for the first time. In 1812, President James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

signed a bill creating the Missouri Territory

The Territory of Missouri was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from June 4, 1812, until August 10, 1821. In 1819, the Territory of Arkansas was created from a portion of its southern area. In 1821, a southeas ...

, including the present-day state of Nebraska. Manuel Lisa

Manuel Lisa, also known as Manuel de Lisa (September 8, 1772 in New Orleans Louisiana (New Spain) – August 12, 1820 in St. Louis, Missouri), was a Spanish citizen and later, became an American citizen who, while living on the western frontier, ...

, a Spanish fur trader from New Orleans, built a trading post called Fort Lisa in the Ponca Hills in 1812. His effort befriending local tribes is credited with thwarting British influence in the area during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

.

The U.S. Army established Fort Atkinson near today's Fort Calhoun in 1820, in order to protect the area's burgeoning fur trade industry. In 1822, the Missouri Fur Company

The Missouri Fur Company (also known as the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company or the Manuel Lisa Trading Company) was one of the earliest fur trading companies in St. Louis, Missouri. Dissolved and reorganized several times, it operated under various ...

built a headquarters and trading post about nine miles north of the mouth of the Platte River and called it Bellevue Bellevue means "beautiful view" in French. It may refer to:

Placenames

Australia

* Bellevue, Western Australia

* Bellevue Hill, New South Wales

* Bellevue, Queensland

* Bellevue, Glebe, an historic house in Sydney, New South Wales

Canada ...

, establishing the first town in Nebraska. In 1824, Jean-Pierre Cabanné established Cabanne's Trading Post

Cabanne's Trading Post was established in 1822 by the American Fur Company as Fort Robidoux near present-day Dodge Park in North Omaha, Nebraska, United States. It was named for the influential fur trapper Joseph Robidoux. Soon after it was ope ...

for John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by smuggling opium into China, and ...

's American Fur Company

The American Fur Company (AFC) was founded in 1808, by John Jacob Astor, a German immigrant to the United States. During the 18th century, furs had become a major commodity in Europe, and North America became a major supplier. Several British co ...

near Fort Lisa at the confluence of Ponca Creek and the Missouri River. It became a well-known post in the region.

In 1833, Moses P. Merill established a mission among the Otoe Indians. The Moses Merill Mission was sponsored by the Baptist Missionary Union

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christianity, Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe ...

. The Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

missionary John Dunbar built a settlement by the Pawnee Indian's main village in 1841 by modern-day Fremont, Nebraska

Fremont is a city and county seat of Dodge County in the eastern portion of the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. The population was 27,141 at the 2020 census. Fremont is the home of Midland University.

History

From the 1830 ...

. The settlement grew quickly as government-financed teachers, blacksmiths and farmers joined the Pawnees and Dunbar, but the settlement disappeared practically overnight when Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

raids scared the gathered whites off the plains. In 1842, John C. Frémont

John Charles Frémont or Fremont (January 21, 1813July 13, 1890) was an American explorer, military officer, and politician. He was a U.S. Senator from California and was the first Republican nominee for president of the United States in 1856 ...

completed his exploration of the Platte River country with Kit Carson

Christopher Houston Carson (December 24, 1809 – May 23, 1868) was an American frontiersman. He was a fur trapper, wilderness guide, Indian agent, and U.S. Army officer. He became a frontier legend in his own lifetime by biographies and n ...

in Bellevue. He sold his mules and government wagons at auction in there. On this mapping trip, Frémont used the Otoe word ''Nebrathka'' to designate the Platte River. Platte is from the French word for "flat", the translation of Ne-brath-ka, meaning "land of flat waters."

1854–1867

Territorial period

The

The Kansas–Nebraska Act

The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 () was a territorial organic act that created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska. It was drafted by Democratic Senator Stephen A. Douglas, passed by the 33rd United States Congress, and signed into law by ...

of 1854 established the 40th parallel north

The 40th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 40 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

At this latitude the sun is vis ...

as the dividing line between the territories of Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

and Nebraska. As such, the original territorial boundaries of Nebraska were much larger than today; the territory was bounded on the west by the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

between the Pacific and Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the " Old World" of Africa, Europe an ...

Oceans; on the north by the 49th parallel north

The 49th parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 49 ° north of Earth's equator. It crosses Europe, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

The city of Paris is about south of the 49th parallel and is the large ...

(the boundary between the United States and Canada), and on the east by the White Earth and Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

rivers. However, the creation of new territories by acts of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

progressively reduced the size of Nebraska.

Most settlers were farmers, but another major economic activity involved support for travelers using the Platte River trails. After gold was discovered in Wyoming in 1859, a rush of speculators followed overland trails through the interior of Nebraska. The Missouri River towns became important terminals of an overland freighting business that carried goods brought up the river in steamboats over the plains to trading posts and Army forts in the mountains. Stagecoaches provided passenger, mail, and express service, and for a few months in 1860–1861 the famous Pony Express

The Pony Express was an American express mail service that used relays of horse-mounted riders. It operated from April 3, 1860, to October 26, 1861, between Missouri and California. It was operated by the Central Overland California and Pik ...

provided mail service.

Many wagon trains trekked through Nebraska on the way west. They were assisted by soldiers at Ft. Kearny and other Army forts guarding the Platte River Road between 1846 and 1869. Fort commanders assisted destitute civilians by providing them with food and other supplies while those who could afford it purchased supplies from post sutlers. Travelers also received medical care, had access to blacksmithing and carpentry services for a fee, and could rely on fort commanders to act as law enforcement officials. Fort Kearny also provided mail services and, by 1861, telegraph services. Moreover, soldiers facilitated travel by making improvements on roads, bridges, and ferries. The forts additionally gave rise to towns along the Platte River route.

The wagon trains gave way to railroad traffic as the Union Pacific Railroad

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

—the eastern half of the first transcontinental railroad—was constructed west from Omaha through the Platte Valley. It opened service to California in 1869. In 1867 Colorado was split off and Nebraska, reduced in size to its modern boundaries, was admitted to the Union.

Land changes

On February 28, 1861,Colorado Territory

The Territory of Colorado was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from February 28, 1861, until August 1, 1876, when it was admitted to the Union as the State of Colorado.

The territory was organized in the w ...

took portions of the territory south of 41° N and west of 102°03' W (25° W of Washington, DC). On March 2, 1861, Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of No ...

took all of the portions of Nebraska Territory north of 43° N (the present-day Nebraska–South Dakota

South Dakota (; Sioux language, Sioux: , ) is a U.S. state in the West North Central states, North Central region of the United States. It is also part of the Great Plains. South Dakota is named after the Lakota people, Lakota and Dakota peo ...

border), along with the portion of present-day Nebraska between the 43rd parallel north

The 43rd parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 43 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

On 21 June the sun averages, wi ...

and the Keya Paha and Niobrara rivers (this land would be returned to Nebraska in 1882). The act creating the Dakota Territory also included provisions granting Nebraska small portions of Utah Territory

The Territory of Utah was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from September 9, 1850, until January 4, 1896, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Utah, the 45th state. ...

and Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

—present-day southwestern Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

, bounded by the 41st parallel north

The 41st parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 41 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

At this latitude the sun is vis ...

, the 43rd parallel north

The 43rd parallel north is a circle of latitude that is 43 degrees north of the Earth's equatorial plane. It crosses Europe, the Mediterranean Sea, Asia, the Pacific Ocean, North America, and the Atlantic Ocean.

On 21 June the sun averages, wi ...

, and the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

. On March 3, 1863, Idaho Territory

The Territory of Idaho was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1863, until July 3, 1890, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as Idaho.

History

1860s

The territory w ...

took everything west of 104°03' W (27° W of Washington, DC).

Civil War

GovernorAlvin Saunders

Alvin Saunders (July 12, 1817November 1, 1899) was a U.S. Senator from Nebraska, as well as the final and longest-serving governor of the Nebraska Territory, a tenure he served during most of the American Civil War.

Education

Saunders was bor ...

guided the territory during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

(1861–1865), as well as the first two years of the postbellum

may refer to:

* Any post-war period or era

* Post-war period following the American Civil War (1861–1865); nearly synonymous to Reconstruction era (1863–1877)

* Post-war period in Peru following its defeat at the War of the Pacific (1879� ...

era. He worked with the territorial legislature to help define the borders of Nebraska, as well as to raise troops to serve in the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

. No battles were fought in the territory, but Nebraska raised three regiments of cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from "cheval" meaning "horse") are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry ...

to help the war effort, and more than 3,000 Nebraskans served in the military.

Capital changes

Thecapital

Capital may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** List of national capital cities

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter Economics and social sciences

* Capital (economics), the durable produced goods used f ...

of the Nebraska Territory was at Omaha

Omaha ( ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Nebraska and the county seat of Douglas County. Omaha is in the Midwestern United States on the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's 39th-largest city ...

. During the 1850s there were numerous unsuccessful attempts to move the capital to other locations, including Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilancio demografico an ...

and Plattsmouth

Plattsmouth is a city and county seat of Cass County, Nebraska, United States. The population was 6,502 at the 2010 census.

History

The Lewis and Clark Expedition passed the mouth of the Platte River, just north of what is now Main Street Pla ...

. In the Scriptown Scriptown was the name of the first subdivision in the history of Omaha, which at the time was located in Nebraska Territory. It was called "Scriptown" because scrip was used as payment, similar to how a company would pay employees when regular mon ...

corruption scheme, ruled illegal by the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

in the case of '' Baker v. Morton'', local businessmen tried to secure land in the Omaha area to give away to legislators. The capital remained at Omaha until 1867 when Nebraska gained statehood, at which time the capital was moved to Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

, which was called Lancaster at that point.

1867–1900

Statehood

A constitution for Nebraska was drawn up in 1866. There was some controversy over Nebraska's admission as a state, in view of a provision in the 1866 constitution restrictingsuffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise, is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally i ...

to White

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

voters; eventually, on February 8, 1867, the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

voted to admit Nebraska as a state provided that suffrage was not denied to non-white voters. The bill admitting Nebraska as a state was vetoed by President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

, but the veto was overridden by a supermajority

A supermajority, supra-majority, qualified majority, or special majority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of more than one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority ru ...

in both Houses of Congress. Nebraska became the first–and to this day the only–state to be admitted to the Union

''Admitted'' is a 2020 Indian Hindi-language docudrama film directed by Chandigarh-based director Ojaswwee Sharma. The film is about Dhananjay Chauhan, the first transgender student at Panjab University. The role of Dhananjay Chauhan has been p ...

by means of a veto override.

All land north of the Keya Paha River (which includes most of Boyd County and a smaller portion of neighboring Keya Paha County) was not originally part of Nebraska at the time of statehood, but was transferred from Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of No ...

in 1882.

Railroads

Land sales

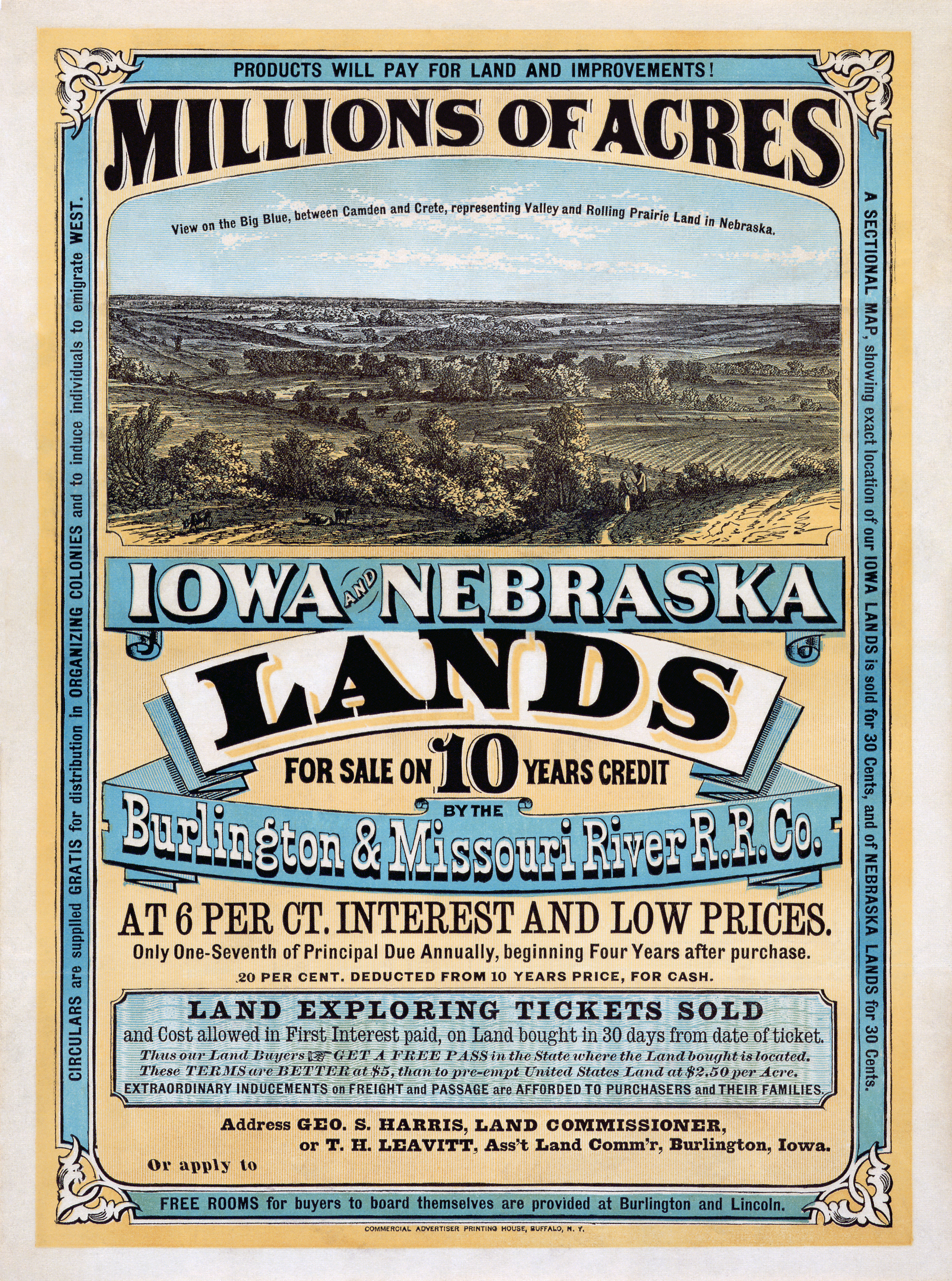

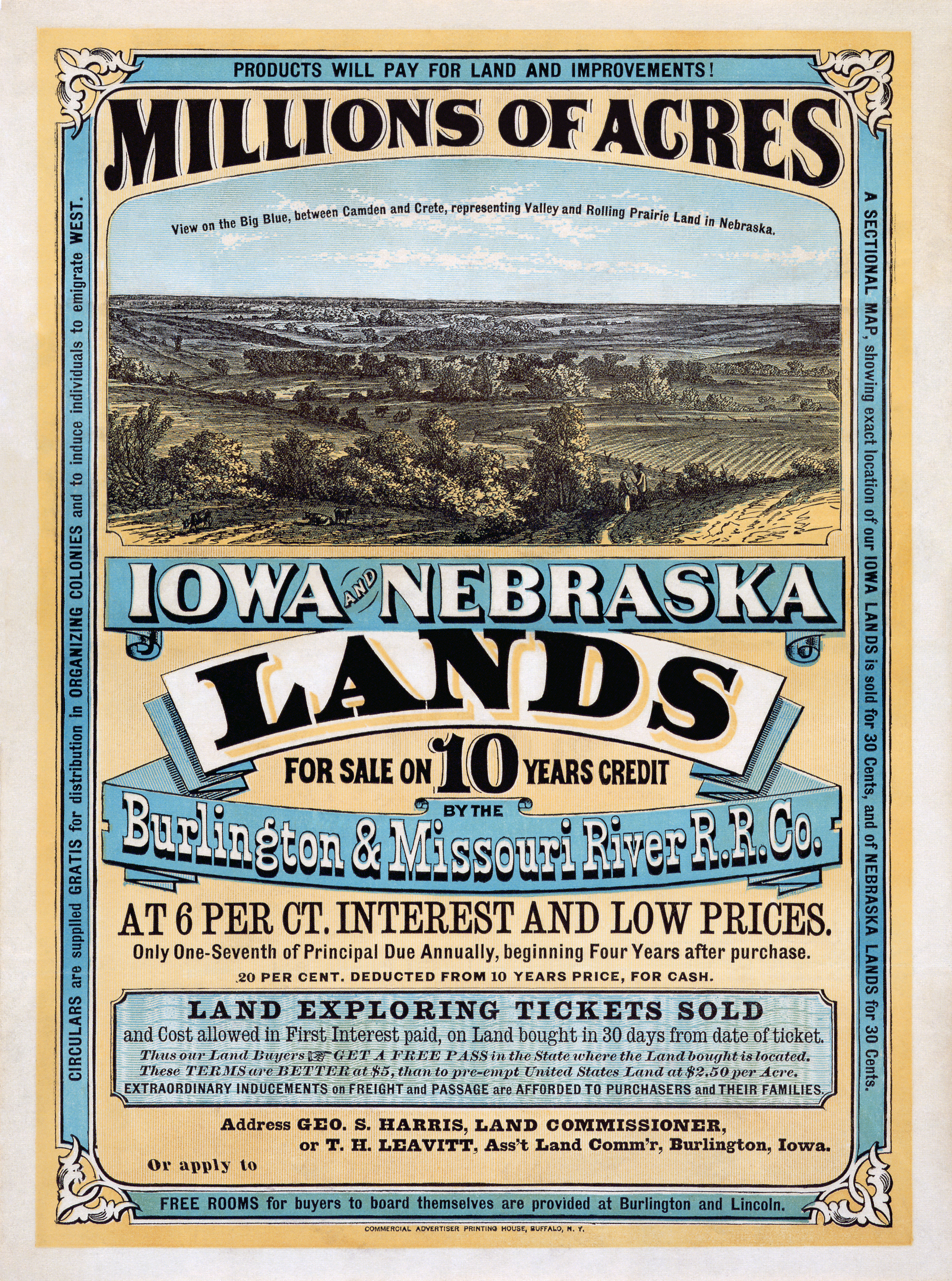

Railroads played a central role in the settlement of Nebraska. The land was good for farms and ranches, but without transportation would be impossible to raise commercial crops. The railroad companies had been given large land grants that were used to back the borrowings from New York and London that financed construction. They were anxious to locate settlers upon the land as soon as possible, ensuring there would be a steady outflow of farm products and a steady inflow of manufactured items purchased by the farmers. Railroads like Union Pacific also built towns that were needed to service the railroad itself, with dining halls for passengers, construction crews, repair shops and housing for train crews. These towns attracted cattle drives and cowboys. In the 1870s and 1880s Civil War veterans and immigrants from Europe came by the thousands to take up land in Nebraska, with this migratory influx helping to rapidly extend westward the frontier line of settlement despite severe droughts, grasshopper plagues, economic distress, and other harsh conditions confronting the new settlers. Most of the great cattle ranches that had grown up near the ends of the trails from Texas gave way to farms, although the Sand Hills remained essentially a ranching country. The

The Union Pacific

The Union Pacific Railroad , legally Union Pacific Railroad Company and often called simply Union Pacific, is a freight-hauling railroad that operates 8,300 locomotives over routes in 23 U.S. states west of Chicago and New Orleans. Union Paci ...

(UP) land grant gave it ownership of 12,800 acres per mile of finished track. The federal government kept every other section of land, rendering a surplus of 12,800 acres to sell or give away to homesteaders. The UP's goal was not to make a profit, but rather to build up a permanent clientele of farmers and townspeople who would form a solid basis for routine sales and purchases. The UP, like other major lines, opened sales offices in the East and in Europe to advertise their lands heavily far away and abroad, offering attractive package rates for migrant farmers to sell out and moved their entire family and necessary agricultural tools to the new destination. In 1870 the UP sold rich Nebraska farmland at five dollars an acre, with one fourth down and the remainder in three annual installments. It gave a 10 percent discount for cash. Farmers could also homestead land, getting it free from the federal government after five years, or even sooner by paying $1.50 an acre. Sales were improved by offering large blocks to ethnic colonies of European immigrants. Germans and Scandinavians, for example, could sell out their small farm back home and buy much larger farms for the same money. European ethnics comprised half of the population of Nebraska in the late 19th century. Married couples were usually the homesteaders, but single women were also eligible on their own.

A typical development program was that undertaken by the Burlington and Missouri River Railroad

The Burlington and Missouri River Railroad (B&MR) or sometimes (B&M) was an American railroad company incorporated in Iowa in 1852, with headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska. It was developed to build a railroad across the state of Iowa and began oper ...

to promote settlement in southeastern Nebraska during 1870–80. The company participated enthusiastically in the boosterism campaigns that drew optimistic settlers to the state. The railroad offered farmers the opportunity to purchase land grant parcels on easy credit terms. Soil quality, topography, and distance from the railroad line generally determined railroad land prices. Immigrants and native-born migrants sometimes clustered in ethnic-based communities, but mostly the settlement of railroad land was by diverse mixtures of migrants. By deliberate campaigns, land sales, and a vast transportation network, the railroads facilitated and accelerated the peopling and development of the Great Plains, with railroads and water key to the potential for success in the Plains environment.

Populism

Populism was a farmers' movement of the early 1890s that emerged in a period of simultaneous crises in agriculture and politics. Farmers who attempted to raise corn and hogs in the dry regions of Nebraska faced economic disaster when drought unexpectedly occurred. When they sought relief through political means, they found the Republican Party complacent, resting on its past achievement of prosperity. The Democratic Party, meanwhile, was preoccupied with the prohibition issue. The farmers turn to radical politicians leading the Populist party, but it became so enmeshed in vehement battles that it accomplished little for the farmers. Omaha was the location of the 1892 convention that formed the Populist Party, with its aptly titled ''Omaha Platform

The Omaha Platform was the party program adopted at the formative convention of the Populist (or People's) Party held in Omaha, Nebraska on July 4, 1892. Origin

The platform preamble was written by Ignatius L. Donnelly. The Omaha platform was ...

'' written by "radical farmers" from throughout the Midwest.

20th century

Progressive Era

In 1900 Populism faded and the Republicans regained power in the state. In 1907 they enacted a number of progressive reform measures, including a direct primary law and a child labor act, in what was one of the most significant legislative sessions in Nebraska's history. Prohibition was of central importance in progressive politics before World War I. Many British-stock and Scandinavian Protestants advocated prohibition as a solution to social problems, while Catholics and German Lutherans attacked prohibition as a menace to their social customs and personal liberty. Prohibitionists supported direct democracy to enable voters to bypass the state legislature in lawmaking. The Republican Party championed the interests of the prohibitionists, while the Democratic Party represented ethnic group interests. After 1914 the issue shifted to the Germans' opposition to Woodrow Wilson's foreign policy. Then both Republicans and Democrats joined in reducing direct democracy in order to reduce German influence in state politics. The political leader of the state's progressive movement wasGeorge W. Norris

George William Norris (July 11, 1861September 2, 1944) was an American politician from the state of Nebraska in the Midwestern United States. He served five terms in the United States House of Representatives as a Republican, from 1903 until 1913 ...

(1861 – 1944). He served five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives as a Republican from 1903 until 1913 and five terms in the U.S. Senate from 1913 until 1943, four terms as a Republican and the final term as an independent. In the 1930s he supported President Franklin Roosevelt, a Democrat, and the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

. Norris was defeated for reelection in 1942.

Land use

Since 1870 the average size of farms has steadily increased, whereas number of farms rapidly increased until about 1900, remained stable until about 1930, then rapidly decreased, as farmers buyout their neighbors and consolidate the holdings. Total area of cropland in Nebraska increased until the 1930s, but then showed long-term stability with large short-term fluctuations. Crop diversity was highest during 1955–1965, then slowly decreased; corn was always a dominant crop, but sorghum and oats were increasingly replaced by soybeans after the 1960s. Land-use changes were affected by farm policies and programs attempting to stabilize commodity supply and demand, reduce erosion, and reduce impacts to wildlife and ecological systems; technological advances (e.g., mechanization, seeds, pesticides, fertilizers); and population growth and redistribution.Transportation

The 450 miles of the Lincoln Highway in Nebraska followed the route of the Platte River Valley, along the narrow corridor where pioneer trails, the Pony Express, and the main line of the Union Pacific Railroad ran. Construction began in 1913, as the road was promoted by a network of state and local boosters until it became U.S. Highway 30 and part of the nation's numbered highway system, with federal highway standards and subsidies. Before 1929 only sixty of its miles were hard surface in Nebraska. Its route was altered repeatedly, most importantly when Omaha was bypassed in 1930. The final section of the roadway was paved west of North Platte, Nebraska, in November 1935. The Lincoln Highway was planned as the most direct route across the country, but such a transcontinental highway was not realized until the 1970s, when Interstate 80 was built parallel to U.S. 30, giving the Lincoln Highway over to local traffic.Retail stores

In the rural areas farmers and ranchers depended on general stores that had a limited stock and slow turnover; they made enough profit to stay in operation by selling at high prices. Prices were not marked on each item; instead the customer negotiated a price. Men did most of the shopping, since the main criterion was credit rather than quality of goods. Indeed, most customers shopped on credit, paying off the bill when crops or cattle were later sold; the owner's ability to judge credit worthiness was vital to his success. In the cities consumers had much more choice, and bought their dry goods and supplies at locally owned department stores. They had a much wider selection of goods than in the country general stores; price tags that gave the actual selling price. The department stores provided a very limited credit, and set up attractive displays and, after 1900, window displays as well. Their clerks were experienced salesmen whose knowledge of the products appealed to the better educated middle-class housewives who did most of the shopping. The keys to success were a large variety of high-quality brand-name merchandise, high turnover, reasonable prices, and frequent special sales. The larger stores sent their buyers to Denver, Minneapolis, and Chicago once or twice a year to evaluate the newest trends in merchandising and stock up on the latest fashions. By the 1920s and 1930s, large mail-order houses such as Sears, Roebuck & Co. and Montgomery Ward provided serious competition, so the department stores relied even more on salesmanship, and close integration with the community. Many entrepreneurs built stores, shops, and offices along Main Street. The most handsome ones used pre-formed, sheet iron facades, especially those manufactured by the Mesker Brothers of St. Louis. These neoclassical, stylized facades added sophistication to brick or wood-frame buildings throughout the state.Government

Senator Norris campaigned for the abolition of the bicameral system in the state legislature, arguing it was outdated, inefficient and unnecessarily expensive, and was based on the "inherently undemocratic" BritishHouse of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

. In 1934, a state constitutional amendment was passed mandating a single-house legislature, and also introducing non-partisan

Nonpartisanism is a lack of affiliation with, and a lack of bias towards, a political party.

While an Oxford English Dictionary definition of ''partisan'' includes adherents of a party, cause, person, etc., in most cases, nonpartisan refers sp ...

elections (where members do not stand as members of political parties).

Government was heavily dominated by men, but there were a few niche roles for women. For example, Nellie Newmark (1888–1978) was the clerk of the District Court at Lincoln for a half-century, 1907–56. She gained a reputation for assisting judges and new attorneys assigned to the court.

Regulation of industry

With no cohesive federal protective legislation, Nebraska's Live Stock Sanitary Commission was created in 1885 to safeguard the public interest of Nebraska citizens through the regulation of the livestock industry. In 1887 the commission was reorganized into the Board of Live Stock Agents; it increased its collaborative efforts with the federal Bureau of Animal Industry. The Nebraska leadership led to more federal involvement in the livestock industry, including passage of the federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906. The Nebraska initiative exemplified the spirit of theProgressive Movement

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techno ...

in the quest to impose scientific standards especially in areas related to public health.

Women

Farm life

In Nebraska, very few single men attempted to operate a farm or ranch; farmers clearly understood the need for a hard-working wife, and numerous children, to handle the many chores, including child-rearing, feeding and clothing the family, managing the housework, feeding the hired hands, and, especially after the 1930s, handling the paperwork and financial details. During the early years of settlement in the late 19th century, farm women played an integral role in assuring family survival by working outdoors. After a generation or so, women increasingly left the fields, thus redefining their roles within the family. New conveniences such as sewing and washing machines encouraged women to turn to domestic roles. The scientific housekeeping movement, promoted across the land by the media and government extension agents, as well as county fairs which featured achievements in home cookery and canning, advice columns for women in the farm papers, and home economics courses in the schools. Although the eastern image of farm life in the prairies emphasizes the isolation of the lonely farmer and farm life, in reality rural Nebraskans created a rich social life for themselves. They often sponsored activities that combined work, food, and entertainment such as barn raisings, corn huskings, quilting bees, Grange meeting, church activities, and school functions. The womenfolk organized shared meals and potluck events, as well as extended visits between families.Teachers

There were few jobs available for young women awaiting marriage. Prairie schoolwomen, or teachers, played a vital role in modernizing the state. Some were from local families, perhaps with their father on the school board, and they took a job that kept money in the community. Others were well educated and more cosmopolitan, and looked at teaching as a career. They believed in universal education and social reform and were generally accepted as members of the community and as extended members of local families. Teachers were deeply involved in social and community activities. In the rural one-room schools, qualifications of the teachers were minimal and salaries were low: male teachers were paid about as much as a hired hand; women were paid less, about the same as those of a domestic servant. In the towns and especially in the cities, the teachers had some college experience, and were better paid. Those farm families that value the education of their children highly, often moved to town or bought a farm close to town, so their children could attend schools. Those few farm youth who attended high school often boarded in town.Great Depression

TheGreat Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

hit Nebraska hard, as grain and livestock prices fell in half, and unemployment was widespread in the cities. The collapse of the stock market in October 1929 did not result in great personal fortunes being lost. The greatest effect the crash had on Nebraska was the fall of farm prices because the state's economy was greatly dependent on their crop. Crop prices began to drop in the final quarter of the year and continued until December 1932 where they reached their lowest in state history. Governor Charles W. Bryan, a Democrat, was at first unwilling to request aid from the national government, but when the Federal Emergency Relief Act became law in 1933 Nebraska took part. Rowland Haynes, the state's emergency relief director, was the major force in implementing such national New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

relief programs as the Federal Emergency Relief Administration

The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) was a program established by President Franklin Roosevelt in 1933, building on the Hoover administration's Emergency Relief and Construction Act. It was replaced in 1935 by the Works Progress Adm ...

(FERA) and the Civil Works Administration. Robert L. Cochran, a Democrat who became governor in 1935, sought federal assistance and placed Nebraska among the first American states to adopt a social security law. The enduring impact of FERA and social security in Nebraska was to shift responsibility for social welfare from counties to the state, which henceforth accepted federal funding and guidelines. The change in state and national relations may have been the most important legacy of these New Deal programs in Nebraska.

World War II

Nebraska fully mobilized its labor and economic resources when the federal call to action came at America's entrance into World War II. Besides many young Nebraskan men serving overseas during the war, food production was expanded and munitions plants, such as theNebraska Ordnance Plant The Nebraska Ordnance Plant is a former United States Army ammunition plant located approximately ½ mile south of Mead, Nebraska and 30 miles west of Omaha, Nebraska in Saunders County. It originally extended across producing weapons from 1942-45 ...

, were built. The Cornhusker Ordnance Plant (COP) in Grand Island, produced its first bombs in November 1942. At its peak it employed 4,200 workers, over 40% of whom were "Women Ordnance Workers" or "WOW's." The WOW's were a major reason that the Quaker Oats Company

The Quaker Oats Company, known as Quaker, is an American food conglomerate based in Chicago. It has been owned by PepsiCo since 2001.

History Precursor miller companies

In the 1850s, Ferdinand Schumacher and Robert Stuart founded oat mills. S ...

, which managed the plant, started one of the nation's earliest corporate child care programs. For Grand Island, the plant brought good wages, high retail sales, severe housing shortages, and an end to Depression-level unemployment. The plant became a major social force, demonstrated by its sponsoring of such wide ranging community groups as local sporting teams and Boy Scouts troops. The city adjusted to the plant's closing in August 1945 with surprising ease. During the Korean and Vietnam conflicts COP resumed production, the ordnance plant finally shutting down in 1973.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

Nebraska was home to several prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

camps. Scottsbluff, Fort Robinson

Fort Robinson is a former U.S. Army fort and now a major feature of Fort Robinson State Park, a public recreation and historic preservation area located west of Crawford on U.S. Route 20 in the Pine Ridge region of northwest Nebraska.

The for ...

, and Camp Atlanta Camp Atlanta () was a World War II camp for German prisoners of war (POWs) located next to Atlanta, Nebraska. Over three years, it housed nearly 3,000 prisoners. After the war, a number of soldiers and prisoners from the camp returned to live in ...

(outside Holdrege) were the main camps. There were many smaller satellite camps at Alma, Bayard, Bertrand, Bridgeport, Elwood, Fort Crook, Franklin, Grand Island, Hastings, Hebron, Indianola, Kearney, Lexington, Lyman, Mitchell, Morrill, Ogallala, Palisade, Sidney, and Weeping Water. Fort Omaha

Fort Omaha, originally known as Sherman Barracks and then Omaha Barracks, is an Indian War-era United States Army supply installation. Located at 5730 North 30th Street, with the entrance at North 30th and Fort Streets in modern-day North Omaha, ...

housed Italian POWs. Altogether there were 23 large and small camps scattered across the state. In addition, several U.S. Army Airfields were constructed at various locations across the state.

Postwar

After the war, conservative Republicans held most of the state major offices. A progressive breakthrough came during the administration of Republican GovernorNorbert Tiemann

Norbert Theodore "Nobby" Tiemann (July 18, 1924 – June 19, 2012) was an American Republican politician from Wausa, Nebraska, and was the 32nd Governor of Nebraska, serving from 1967 to 1971.

Biography

Tiemann was born in Minden, Nebraska. He ...

(1967–1971) who successfully pushed for a number of major changes. A new revenue act included a sales tax and an income tax, replacing the state property tax and other taxes. The Municipal University of Omaha joined the state University of Nebraska

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, the ...

system as the University of Nebraska, Omaha. A new department of economic development was created as well as a state personnel office. State economic initiatives paved the way for the bond indebted financing of highway and sewage treatment plant construction projects. Improvement of state mental health facilities and fair housing practices were also enacted, along with the first minimum wage law and new of open-housing legislation.

The nationwide farm crisis of the 1980s hit the state hard with a wave of farm foreclosures. On the positive side, Omaha's geographic centrality in the American Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Highway System in the United States. Th ...

and large well-educated population made the city an attractive place for many small manufacturing concerns to set up shop. By the early 1990s, Omaha had become a major center of the telecommunications industry, which surpassed meat-packing in terms of employment. After 2000, however, Omaha's call centers faced stiff competition from outsourced foreign operators in India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and other developing nations.

On December 5, 2007, the state's deadliest mass shooting occurred at Westroads Mall in Omaha. Nine people died and five were injured.

Culture

FollowingWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, and especially after the 1960s, fine arts

In European academic traditions, fine art is developed primarily for aesthetics or creative expression, distinguishing it from decorative art or applied art, which also has to serve some practical function, such as pottery or most metalwork ...

projects flourished in Nebraska. During this period existing orchestras were expanded and new ones chartered while local museums and art galleries sprung up in communities across the state, this renaissance occurring in no small part due to the energetic support of Nebraska's higher education institutions and the National Endowment for the Humanities

The National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) is an independent federal agency of the U.S. government, established by thNational Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act of 1965(), dedicated to supporting research, education, preserv ...

funded Nebraska Arts Council and Nebraska Humanities Council Humanities Nebraska (HN) is a non-profit affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) based in Lincoln, Nebraska. HN creates and supports public humanities programs with the goal of engaging the public with history and culture.

His ...

.

Hispanics

Hispanic Americans

Hispanic and Latino Americans ( es, Estadounidenses hispanos y latinos; pt, Estadunidenses hispânicos e latinos) are Americans of Spaniards, Spanish and/or Latin Americans, Latin American ancestry. More broadly, these demographics include a ...

have lived in the region since before Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

became a state in 1867, but large scale migration didn't began until the 1980s and 1990s. In 1972, Nebraska was the first state to establish a statutory agency devoted to the needs of Hispanics, a group which then numbered about 30,000. Mexicans generally entered low skilled, low-wage occupations in the hospitality, manufacturing, food processing, and agricultural industries. One example was the small city of Schuyler Schuyler may refer to:

Places United States

* Schuyler County, Illinois

* Schuyler County, Missouri

* Schuyler, Nebraska, a city

* Schuyler County, New York

* Schuyler, New York, a town

* Schuyler Island, Lake Champlain, New York

* Schuyler C ...

in Colfax County, an area previously dominated by German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

and Czech

Czech may refer to:

* Anything from or related to the Czech Republic, a country in Europe

** Czech language

** Czechs, the people of the area

** Czech culture

** Czech cuisine

* One of three mythical brothers, Lech, Czech, and Rus'

Places

* Czech, ...

ethnics who settled there around the turn of the last century. Another case study is Lexington, seat of Dawson County. The Hispanic population soared tenfold between 1990 and 2000, from just over 400 to about 4,000, and the city's overall population grew from 6,600 to over 10,000. The positive economic trends in the 1990s contrasted sharply with the 1980s, when Dawson County's population and overall employment rate declined rapidly. Fears that immigration would depress wages and raise unemployment rates across the state were unfounded. Indeed, just the reverse happened. The Hispanic migration wave increased both labor supply and demand, businessmen discovering that they could profitably expand their operations in Douglas County with a fresh supply of willing labor. The net result of the growing Hispanic population in Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

was an upsurge in employment, average wages, and economic prosperity for all sectors.Örn Bodvarsson, and Hendrik VandenBerg, "The Impact of Immigration on a Local Economy: The Case of Dawson County, Nebraska", ''Great Plains Research'', September 2003, Vol. 13 Issue 2, pp. 291–309.

Notes

Bibliography

Surveys

* Andreas, Alfred T. ''History of the State of Nebraska'' (1882), a rich mine of informatioonline edition

* Hickey, Donald R. et al. ''Nebraska Moments'' (U. of Nebraska Press, 2007), 39 short historical essays; 403pp; * Luebke, Frederick C. ''Nebraska: An Illustrated History'' (1995) * Morton, J. Sterling, ed. ''Illustrated History of Nebraska: A History of Nebraska from the Earliest Explorations of the Trans-Mississippi Region.'' 3 vols. (1905–13

online free vol 1

* Naugle, Ronald C., John J. Montag, and James C. Olson. ''History of Nebraska'' (4th ed. U of Nebraska Press, 2015). 568 pp

online review

** older editions: Olson, James C, and Ronald C. Naugle. ''History of Nebraska'' (3rd ed. University of Nebraska Press, 1997) 506pp * Sheldon, Addison Erwin. ''Nebraska: The Land and the People''. (3 vols. 1931). old detailed narrative, with biographies * Wishart, David J. ''Encyclopedia of the Great Plains'' (2004

excerpt

Politics

* Barnhart John D. "Rainfall and the Populist Party in Nebraska." ''American Political Science Review'' 19 (1925): 527–40in JSTOR

* Berens; Charlyne. ''Chuck Hagel: Moving Forward'' (U. of Nebraska Press, 2006) GOP senator 1997–2008 * Cherny, Robert W. ''Populism, Progressivism and the Transformation of Nebraska Politics, 1885–1915'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1981) * Folsom, Burton W. "Tinkerers, tipplers, and traitors: ethnicity and democratic reform in Nebraska during the Progressive era." ''Pacific Historical Review'' 50.1 (1981): 53-75

online

* Folsom, Burton W, Jr. ''No More Free Markets or Free Beer: The Progressive Era in Nebraska, 1900–1924'' (1999). * Lowitt Richard. ''George W. Norris'' (3 vols. 1963–75), emphasis on national role * Luebke Frederick C. ''Immigrants and Politics: The Germans of Nebraska, 1880–1900'' (University of Nebraska Press, 1969). * Olson James C. ''J. Sterling Morton'' (U. of Nebraska Press, 1942). * Parsons Stanley B, Jr. ''The Populist Context: Rural versus Urban Power on a Great Plains Frontier'' (Greenwood Press, 1973). * Pederson James F, and Kenneth D. Wald. ''Shall the People Rule? A History of the Democratic Party in Nebraska Politics, 1854–1972'' (Lincoln: Jacob North, 1972). * Potter, James E. ''Standing Firmly by the Flag: Nebraska Territory and the Civil War, 1861–1867'' (University of Nebraska Press, 2012) 375 pp.

Social and economic history

* Bogue, Allen G. ''Money at Interest: The Farm Mortgage on the Middle Border'' (Cornell University Press, 1955) * Brunner Edmund de S. ''Immigrant Farmers and Their Children'' (1929), sociological study. * Combs, Barry B. "The Union Pacific Railroad and the Early Settlement of Nebraska." ''Nebraska History'' 50#1 (1969): 1-26. * Dick, Everett. ''The Sod-House Frontier: 1854–1890'' (1937), on town and farm life before 1900online free to borrow

* Dick, Everett. ''Vanguards of the frontier : a social history of the northern plains and Rocky Mountains from the fur traders to the sod busters'' (1941

online free to borrow

* Fink, Deborah. ''Agrarian Women: Wives and Mothers in Rural Nebraska, 1880–1940'' (1992) * Hurt, R. Douglas. ''The Great Plains During World War II'' (2008), 524pp * Meyering; Sheryl L. ''Understanding O Pioneers! and My Antonia: A Student Casebook to Issues, Sources, and Historical Documents'' (Greenwood Press, 2002) * Pound, Louise. ''Nebraska Folklore'' (1913) (reprint University of Nebraska Press, 2006)

Geography and environment