The history of

Málaga

Málaga (; ) is a Municipalities in Spain, municipality of Spain, capital of the Province of Málaga, in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. With a population of 591,637 in 2024, it is the second-most populo ...

, shaped by the city's location in southern Spain on the western shore of the Mediterranean Sea, spans about 2,800 years, making it one of the

oldest cities in the world. The first inhabitants to settle the site may have been the

Bastetani,

an ancient

Iberian tribe. The Phoenicians founded their

colony

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their ''metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often orga ...

of Malaka

( )

(,

''Málaka'') about 770BC. From the 6th centuryBC, it was under the hegemony of

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

in present-day

Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

. From 218BC, Malaca was ruled by the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

; it was federated with the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

at the end of the 1st century during the reign of

Domitian

Domitian ( ; ; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was Roman emperor from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavian dynasty. Described as "a r ...

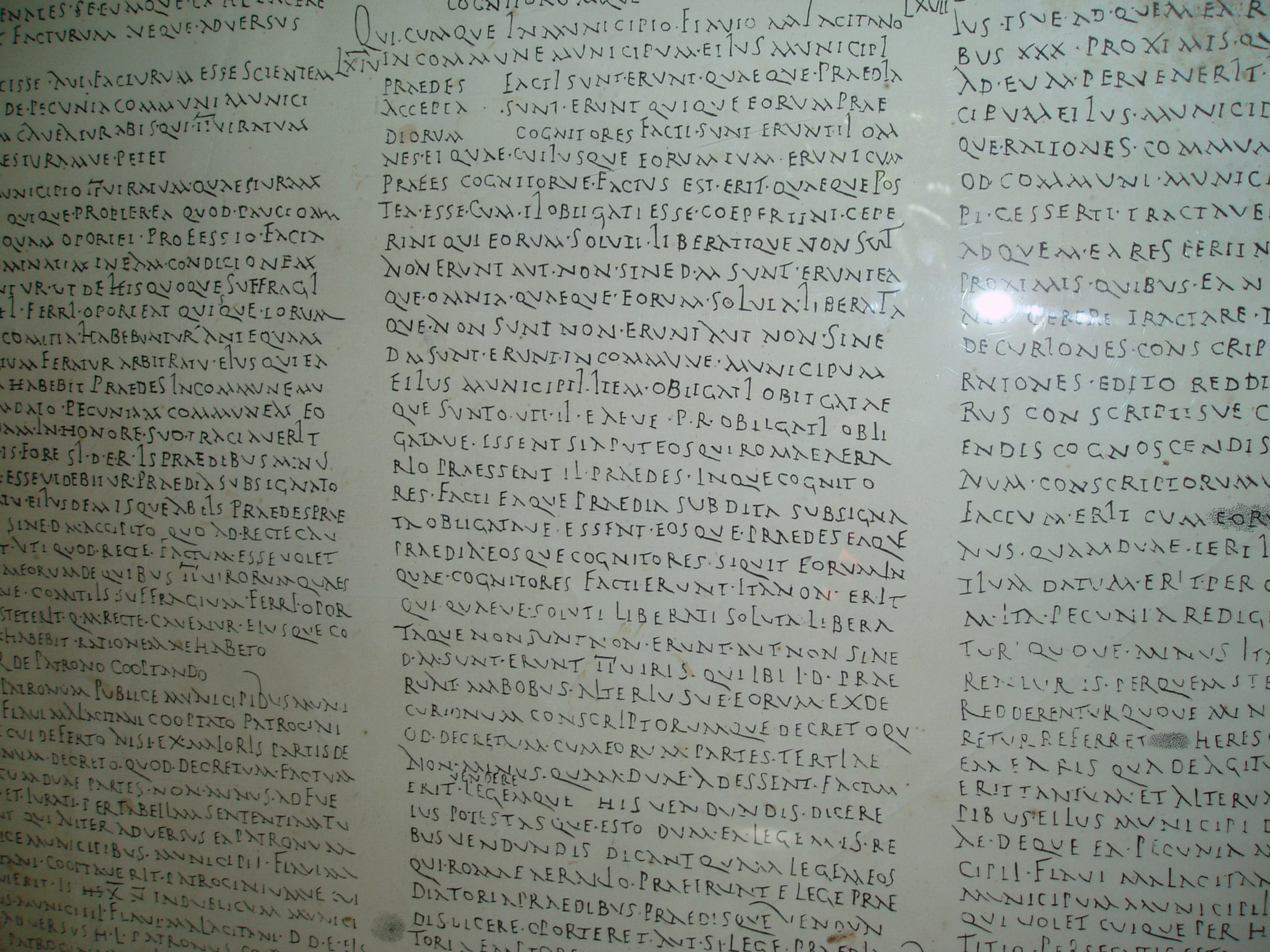

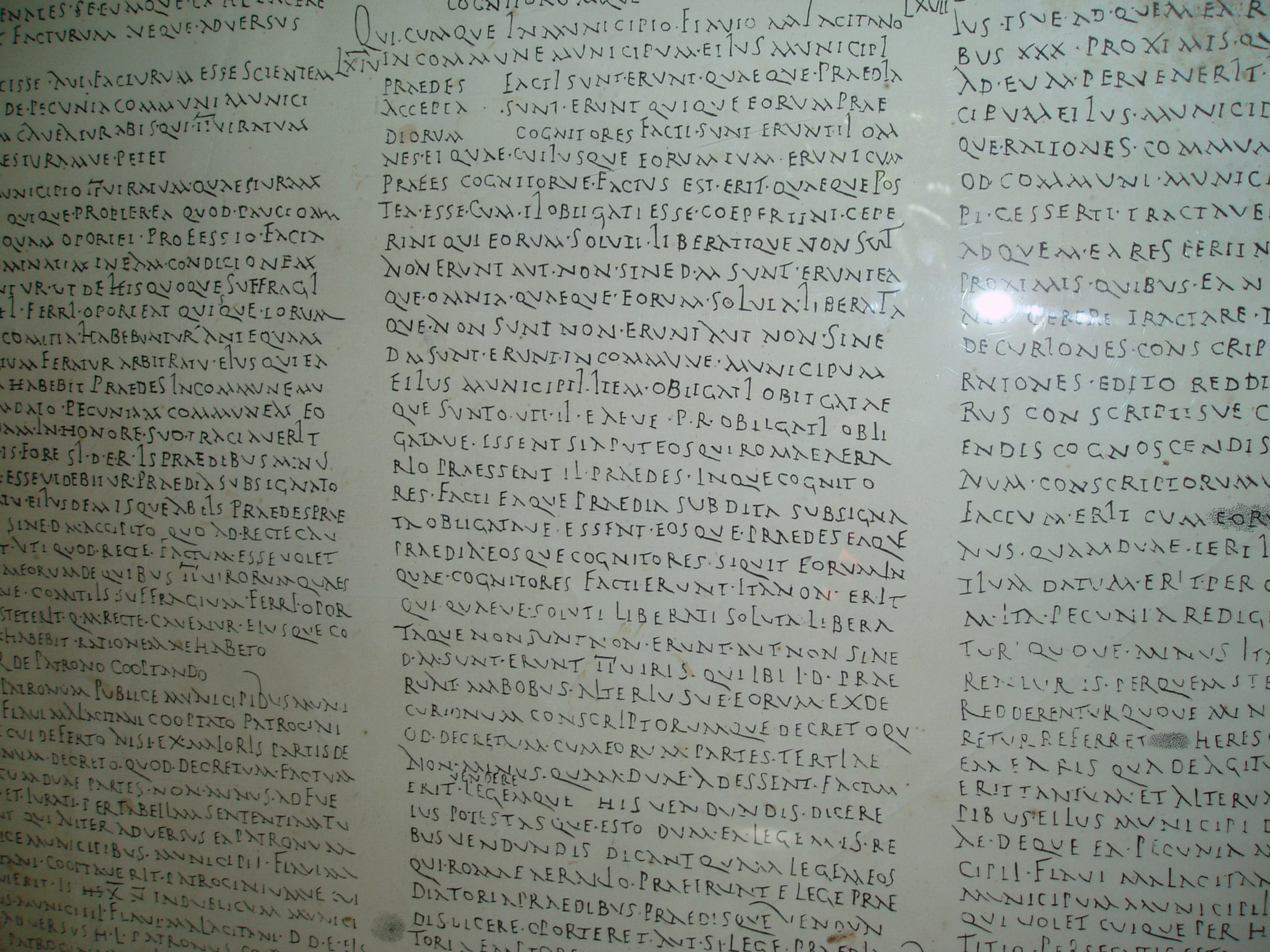

. Thereafter it was governed under its own municipal code, the ''

Lex Flavia Malacitana'', which granted free-born persons the privileges of

Roman citizenship

Citizenship in ancient Rome () was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, traditions, and cu ...

.

The decline of the Roman imperial power in the 5th century led to invasions of

Hispania Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces created in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) in 27 BC. Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of ...

by

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

, who were opposed by the

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. In

Visigothic Spain

The Visigothic Kingdom, Visigothic Spain or Kingdom of the Goths () was a Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian kingdom that occupied what is now southwestern France and the Iberian Peninsula from the 5th to the 8th centuries. One of the Germanic people ...

, the Byzantines took Malaca and other cities on the southeastern coast and founded the new province of

Spania

Spania () was a Roman province, province of the Eastern Roman Empire from 552 until 624 in the south of the Iberian Peninsula and the Balearic Islands. It was established by the List of Byzantine emperors, Emperor Justinian I in an effort to res ...

in 552. Malaca became one of the principal cities of the short-lived Byzantine ', which lasted until 624, when the Byzantines were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula. After the

Muslim conquest of Spain

The Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula (; 711–720s), also known as the Arab conquest of Spain, was the Umayyad conquest of the Visigothic Kingdom of Hispania in the early 8th century. The conquest resulted in the end of Christian rule in ...

(711–718), the city, then known as Mālaqah (), was encircled by walls, next to which Genoese and Jewish merchants settled in their own quarters. In 1026 it became the capital of the

Taifa of Málaga, an independent Muslim kingdom ruled by the

Hammudid dynasty in the

Caliphate of Córdoba

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

, which existed for four distinct time-periods: from 1026 to 1057, from 1073 to 1090, from 1145 to 1153 and from 1229 to 1239, when it was finally conquered by the

Nasrid Kingdom of Granada.

The siege of Mālaqa by

Isabella and Ferdinand in 1487 was one of the longest of the

Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

. The Muslim population was punished for its resistance by enslavement or death. Under

Castillian domination, churches and convents were built outside the walls to unite the Christians and encourage the formation of new neighborhoods. In the 16th century, the city entered a period of slow decline, exacerbated by epidemics of disease, several successive poor food crops, floods, and earthquakes.

With the advent of the 18th century the city began to recover some of its former prosperity. For much of the 19th century, Málaga was one of the most rebellious cities of the country, contributing decisively to the triumph of Spanish

liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

. Although this was a time of general political, economic and social crisis in Málaga, the city was a pioneer of the

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

on the

Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

, becoming the first industrialised city in Spain. This began the ascendancy of powerful Málagan

bourgeois

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and Aristocracy (class), aristocracy. They are tradition ...

families, some of them gaining influence in national politics. In the last third of the century, during the short regime of the

First Spanish Republic

The Spanish Republic (), historiographically referred to as the First Spanish Republic (), was the political regime that existed in Spain from 11 February 1873 to 29 December 1874.

The Republic's founding ensued after the abdication of King ...

, the social upheavals of the

Cantonal Revolution of 1873 culminated in the proclamation of the Canton of Málaga on 22 July 1873. Málaga political life then was characterised by a radical and extremist tone. The federal republican ''(republicanismo federal)'' movement gained strong support among the working classes and encouraged insurrection, producing great alarm among the affluent.

A new decline of the city began in 1880. The economic crisis of 1893 forced the closing of the La Constancia iron foundry and was accompanied by the collapse of the sugar industry and the spread of the

phylloxera

Grape phylloxera is an insect pest of grapevines worldwide, originally native to eastern North America. Grape phylloxera (''Daktulosphaira vitifoliae'' (Fitch 1855) belongs to the family Phylloxeridae, within the order Hemiptera, bugs); orig ...

blight, which devastated the vineyards surrounding Málaga. The early 20th century was a period of economic readjustment that produced a progressive industrial dismantling and fluctuating development of commerce. Economic depression, social unrest and political repression made it possible for

petite bourgeois republicanism and the labor movement to consolidate their positions.

In 1933, during the Second Spanish Republic, Málaga elected the first deputy of the

Communist Party of Spain

The Communist Party of Spain (; PCE) is a communist party that, since 1986, has been part of the United Left coalition, which is currently part of Sumar. Two of its politicians are Spanish government ministers: Yolanda Díaz (Minister of L ...

, or ''Partido Comunista de España'' (PCE). In February 1937 the nationalist army, with the help of Italian volunteers, launched an offensive against the city under the orders of

General Queipo de Llano, occupying it on 7 February. Local repression by the Francoist military dictatorship was perhaps the harshest of the civil war, with an estimated 17,000–20,000 citizens shot and buried in mass graves at the cemetery of San Rafael.

During the military dictatorship, the city experienced the rapid expansion of tourism from abroad on the

Costa del Sol

The Costa del Sol (; literally "Coast of the Sun") is a region in the south of Spain in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, comprising the coastal towns and communities along the coastline of the Province of ...

, igniting an economic boom in the city beginning in the 1960s. After the end of the Francoist military dictatorship, the first candidate for mayor on the ticket of the Spanish Socialist Workers Party or ''Partido Socialista Obrero Español'' (PSOE) was elected, and remained in office until 1995, when the conservative Popular Party or ''Partido Popular'' (PP) won the municipal elections and have governed since.

Prehistory and antiquity

The territory now occupied by the

Province of Málaga

The province of Málaga ( ) is located in Andalusia, Spain. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the south and by the provinces of Cádiz to the west, Seville to the northwest, Córdoba to the north, and Granada to the east.

The province ...

has been inhabited since prehistoric times, as evidenced by the cave paintings of the ''Cueva de la Pileta'' (Cave of the Pool) in

Benaoján, artefacts found at sites such as the

Dolmen of Menga near

Antequera

Antequera () is a city and municipality in the Comarca de Antequera, province of Málaga, part of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is known as "the heart of Andalusia" (''el corazón de An ...

and the Cueva del Tesoro (Treasure Cave) near ''Rincón de la Victoria'', as well as the pottery, tools and skeletons found in

Nerja. Paintings of seals from the Paleolithic and post-Paleolithic eras found in the

Nerja Caves and attributed to

Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

s may be about 42,000 years old and could be the first known works of art, according to José Luis Sanchidrián of the University of Córdoba.

Phoenician Malake

The first colonial settlement in the area, dating from around 770BC, was made by seafaring

Phoenicians

Phoenicians were an ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syrian coast. They developed a maritime civi ...

from

Tyre, on an islet in the estuary of the

River Guadalhorce at

Cerro del Villar (the coastline of Málaga has changed considerably since that time, as river silting and changes in river levels have filled the ancient estuary and moved the site inland).

Although the island was ill-suited for habitation, it is likely the Tyrians chose to settle it because of its strategic location, the possibilities for trade, and the excellent natural harbor. Sailboats heading towards the Strait of Gibraltar would have found protection there from powerful sea-currents and strong westerly winds.

From Cerro del Villar, the Phoenicians began trading with coastal indigenous villages and the small community at present-day San Pablo near the mouth of the river

Guadalmedina. Gradually the center of commerce was moved to the mainland and the new trading colony of Malake was founded, which was from the 8th century BC a vibrant commercial center.

The Phoenician colonial period lasted approximately from 770 to 550BC.

Economic development in the colony at Cerro del Villar, later to become Malaka, included industries for the production of

sea salt

Sea salt is salt that is produced by the evaporation of seawater. It is used as a seasoning in foods, cooking, cosmetics and for preserving food. It is also called bay salt, solar salt, or simply salt. Like mined rock salt, production of sea sal ...

and of

purple dye.

The Phoenicians had discovered in the waters off the coast

murex sea snails, the source of the famed

Tyrian purple

Tyrian purple ( ''porphúra''; ), also known as royal purple, imperial purple, or imperial dye, is a reddish-purple natural dye. The name Tyrian refers to Tyre, Lebanon, once Phoenicia. It is secreted by several species of predatory sea snails ...

. As in other Phoenician colonies, Malaka's urban development was associated with religious devotion, demonstrated by the centrality accorded the religious emporium or temple before Malaka's urban core was laid out in this section of the city.

The dominance of the Phoenicians as a Mediterranean trading power waned after Babylonian king

Nebuchadnezzar

Nebuchadnezzar II, also Nebuchadrezzar II, meaning "Nabu, watch over my heir", was the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from the death of his father Nabopolassar in 605 BC to his own death in 562 BC. Often titled Nebuchadnezzar ...

finally took the city of Tyre, sometime around 572BC, after a lengthy series of campaigns.

According to the

Cyropaedia

The ''Cyropaedia'', sometimes spelled ''Cyropedia'', is a partly fictional biography of Cyrus the Great, the founder of Persia's Achaemenid Empire. It was written around 370 BC by Xenophon, the Athens, Athenian-born soldier, historian, and studen ...

,

Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

's mostly fictitious biography of

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

, the founder of the

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

conquered Phoenicia in 539BC, but many scholars believe this information is dubious.

While the influence of the Phoenicians declined, it did not disappear entirely in the western Mediterranean, however, as their place was taken by the Carthaginians, whose capital city of

Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

had been founded as a Phoenician trading outpost in 814BC. It is likely that much of the Phoenician population migrated to Carthage and other colonies following the Persian conquest. Having gained independence around 650BC, Carthage soon developed its own considerable mercantile presence in the Mediterranean.

Greek Mainake

The Phoenician settlements were more densely concentrated on the coastline east of Gibraltar than they were further up the coast. Market rivalry had attracted the Greeks to Iberia, who established their own trading colonies along the northeastern coast before venturing into the Phoenician corridor. They were encouraged by the Tartessians, who may have desired to end the Phoenician economic monopoly.

Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

mentions that around 630 BC, the

Phocaea

Phocaea or Phokaia (Ancient Greek language, Ancient Greek: Φώκαια, ''Phókaia''; modern-day Foça in Turkey) was an ancient Ionian Ancient Greece, Greek city on the western coast of Anatolia. Colonies in antiquity, Greek colonists from Phoc ...

ns established relations with King

Arganthonios

Arganthonios () was a king of ancient Tartessos (in Andalusia, southern Spain) who according to Herodotus, was visited by Colaeus, Kolaios of Samos. Given the legendary status of Geryon, Gargoris and Habis, Arganthonios is the earliest documente ...

(670–550 BC) of

Tartessos

Tartessos () is, as defined by archaeological discoveries, a historical civilization settled in the southern Iberian Peninsula characterized by its mixture of local Prehistoric Iberia, Paleohispanic and Phoenician traits. It had a writing syste ...

, who gave them money to build walls around their city.

Later they founded

Mainake (, ''Mainákē'') on the Málaga coast (Strabo. 3.4.2).

Dominion of Carthage

Nebuchadnezzar II had recaptured mainland Tyre and Sidon from

Amasis II

Amasis II ( ; ''ḤMS'') or Ahmose II was a pharaoh (reigned 570526 BCE) of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty of Egypt, the successor of Apries at Sais, Egypt, Sais. He was the last great ruler of Ancient Egypt, Egypt before the Achaemenid Empire, Persian ...

sometime between 572 and 562BC, with the intention of appropriating the rich Tyrian trade.

After his successful siege of Tyre, and with the transition to Carthaginian domination of the western Mediterranean, Malaka became in 573BC a colony of the Punic empire of Carthage, which sent its own settlers.

The mercantile nature of the city, which developed during Phoenician rule,

had taken hold, as well as such idiosyncratic cultural features as the religious cults devoted to the gods

Melqart

Melqart () was the tutelary god of the Phoenician city-state of Tyre and a major deity in the Phoenician and Punic pantheons. He may have been central to the founding-myths of various Phoenician colonies throughout the Mediterranean, as well ...

and

Tanit

Tanit or Tinnit (Punic language, Punic: 𐤕𐤍𐤕 ''Tīnnīt'' (JStor)) was a chief deity of Ancient Carthage; she derives from a local Berber deity and the consort of Baal Hammon. As Ammon is a local Libyan deity, so is Tannit, who represents ...

.

The second half of the sixth century BC marks the transition between the Phoenician and the

Punic

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians (and sometimes as Western Phoenicians), were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' ...

periods of Málaga.

When the Phoenician city-states of the eastern Mediterranean were assimilated into the Persian empire in the 6th century BC, Carthage took advantage of their diminishing control over maritime trade. For two hundred years the Phoenician settlements had maintained close relationships with the "mother cities" on the coast of Syria and Lebanon, but from the mid-6th century, these connections shifted to the north African city of Carthage as it expanded its hegemony. With the arrival of the

Magonid dynasty around 550 BC, Carthaginian foreign policy seems to have changed dramatically. Carthage now took the lead, establishing itself as the dominant Phoenician military power in the western Mediterranean. Although a Punic-Etruscan fleet of 120 ships was defeated by a Greek force of Phocaean ships in the naval

Battle of Alalia between 540 BC and 535 BC, and Carthage lost two more major naval battles with

Massalia

Massalia (; ) was an ancient Greek colonisation, Greek colony (''apoikia'') on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast, east of the Rhône. Settled by the Ionians from Phocaea in 600 BC, this ''apoikia'' grew up rapidly, and its population se ...

, it still managed to close the

Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

The two continents are separated by 7.7 nautical miles (14.2 kilometers, 8.9 miles) at its narrowest point. Fe ...

to Greek shipping and thus contained the Greek expansion in Spain by 480 BC.

Carthage proceeded to destroy Tartessos and to drive the Greeks from southern Iberia. It defended its trade monopoly in the western Mediterranean vigilantly, attacking the merchant ships of its rivals. During the 3rd century BC, Carthage made Iberia the new base for its empire and its campaigns against the Roman Republic. Although they had little influence in the hinterland behind the coastal mountains, the Carthaginians occupied most of Andalusia, expanding along the northern Mediterranean coast and establishing a new capital at Cartagena.

The Romans conquered the city as well as the other regions under the rule of Carthage after the

Punic Wars

The Punic Wars were a series of wars fought between the Roman Republic and the Ancient Carthage, Carthaginian Empire during the period 264 to 146BC. Three such wars took place, involving a total of forty-three years of warfare on both land and ...

in 218BC.

Roman Malaca

The romanisation of Málaga was, as in most of southern

Hispania Ulterior

Hispania Ulterior (English: "Further Hispania", or occasionally "Thither Hispania") was a Roman province located in Hispania (on the Iberian Peninsula) during the Roman Republic, roughly located in Baetica and in the Guadalquivir valley of moder ...

, effected peacefully through a ', a treaty recognising both parties as equals, obligated to assist each other in defensive wars or when otherwise summoned. The Romans unified the people of the coast and interior under a common power; Roman settlers in Malaca exploited the local natural resources and introduced Latin as the language of the ruling classes, establishing new manners and customs that gradually changed the culture of the native people. Malaca was integrated into the Roman Republic as part of Hispania Ulterior, but Romanisation seems to have progressed slowly, as indicated by the discovery of inscriptions dating to the 1st century AD written in the Phoenician alphabet. During this period the Municipium Malacitanum became a transit point on the ''

Via Herculea'', which revitalised the city both economically and culturally by connecting it with other developed enclaves in the interior of Hispania and with other ports of the Mediterranean Sea.

With the fall of the Republic and the advent of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, the territory of Malaca, which had already been occupied for two centuries by the Romans, was framed administratively as one of four legal convents into which the province of

Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces created in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) in 27 BC. Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of ...

, newly created by order of

Caesar Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in ...

, was divided. Baetica by this time was rich and completely Romanised; the emperor

Vespasian

Vespasian (; ; 17 November AD 9 – 23 June 79) was Roman emperor from 69 to 79. The last emperor to reign in the Year of the Four Emperors, he founded the Flavian dynasty, which ruled the Empire for 27 years. His fiscal reforms and consolida ...

rewarded the province by granting it the

ius latii, which extended the rights of Roman citizenship (''latinitas'') to its inhabitants, an honor that secured the loyalty of the Baetian elite and the middle class.

According to the Greek geographer Strabo, the city had an irregular plan, in the manner of the Phoenician cities. The Romans began the construction of important public works: the

Flavian dynasty

The Flavian dynasty, lasting from 69 to 96 CE, was the second dynastic line of emperors to rule the Roman Empire following the Julio-Claudian dynasty, Julio-Claudians, encompassing the reigns of Vespasian and his two sons, Titus and Domitian. Th ...

improved the port and

Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

built the

Roman theater. Thereafter the emperor

Titus

Titus Caesar Vespasianus ( ; 30 December 39 – 13 September AD 81) was Roman emperor from 79 to 81. A member of the Flavian dynasty, Titus succeeded his father Vespasian upon his death, becoming the first Roman emperor ever to succeed h ...

of the Flavian family granted Malaca its privileges as a municipality.

Malaca reached a high cultural and civic development in this period, having been converted into a federated city of the empire, and was governed by its own code of laws, the ''

Lex Flavia Malacitana''. The presence of an educated populace and their patronage of the arts had a significant bearing on this. The great Roman baths, remains of which have been found in the subsoil of the Pintor Nogales and the Cistercian Abbey, also belong to this period, as well as numerous sculptures now preserved in the

Museo de Málaga.

The Roman

Roman theater, which dates from the 1st century BC, was rediscovered by accident in 1951. The theater is well preserved but has not been completely excavated. The Augustan character of the inscriptions found there date it from this period. The theater appears to have been abandoned in the 3rd century, as it was covered with a dump rich in small finds of the 3rd–4th centuries. The upper part of the stage was not covered, and its material was reused by the Arabs in the

Alcazaba.

The economy and the wealth of the territory were dependent mainly on agriculture in the inland areas, the abundance of the fishery in the waters off the coast, and the productions of local artisanal works. Among noteworthy Malacan products for export were wine, olive oil and the ''

garum

Garum is a fermentation (food), fermented fish sauce that was used as a condiment in the cuisines of Phoenicia, Ancient Greek cuisine, ancient Greece, Ancient Roman cuisine, Rome, Carthage and later Byzantine cuisine, Byzantium. Liquamen is a si ...

malacitano'', a fermented fish sauce famed throughout the empire and in demand as a luxury item in Rome. Regarding the social aspects of religious practice in Malaca, it can be said that each ethnic group adhered to its own cult, as did imported

slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

who clung to their native religions. In 325, the year of the

Council of Nicaea, Malaca figured as one of the few Roman enclaves in Hispania where Christianity was strongly rooted. Previously, there had been frequent uprisings of an anti-Roman character catalyzed by the opposition to paganism of those Hispano-Romans affiliated with Christianity.

Spain's present languages, its religion, and the basis of its laws originate from the Roman period. The centuries of uninterrupted Roman rule and settlement left a deep and enduring imprint upon the culture of what is now Málaga.

Germanic invasions and Visigothic rule

In the 5th century,

Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were tribal groups who lived in Northern Europe in Classical antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. In modern scholarship, they typically include not only the Roman-era ''Germani'' who lived in both ''Germania'' and parts of ...

, including the

Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

,

Suevi

file:1st century Germani.png, 300px, The approximate positions of some Germanic peoples reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 1st century. Suebian peoples in red, and other Irminones in purple.

The Suebi (also spelled Suavi, Suevi or Suebians ...

,

Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

, and

Visigoths

The Visigoths (; ) were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian military group unite ...

, as well as the

Alans

The Alans () were an ancient and medieval Iranian peoples, Iranic Eurasian nomads, nomadic pastoral people who migrated to what is today North Caucasus – while some continued on to Europe and later North Africa. They are generally regarded ...

of

Sarmatian

The Sarmatians (; ; Latin: ) were a large confederation of Ancient Iranian peoples, ancient Iranian Eurasian nomads, equestrian nomadic peoples who dominated the Pontic–Caspian steppe, Pontic steppe from about the 5th century BCE to the 4t ...

descent, crossed the

Pyrenees

The Pyrenees are a mountain range straddling the border of France and Spain. They extend nearly from their union with the Cantabrian Mountains to Cap de Creus on the Mediterranean coast, reaching a maximum elevation of at the peak of Aneto. ...

mountain range into the Iberian peninsula. The Visigoths eventually emerged as the dominant power, and in about 511, they moved onto the Malaca coast. However, Hispania remained relatively Romanised under their rule—it did not see a decline in the perpetuation of classical culture comparable to that in Britain, Gaul, Lombardy and Germany. The Visigoths adopted Roman culture and language, and maintained more of the old Roman institutions. They had a respect for the legal codes that resulted in continuous frameworks and historical records for most of the period between 415, when Visigothic rule in parts of Spain began, and 711, when it is traditionally said to end. The Catholic bishops were the rivals of Visigothic power and culture until the end of the 6th and beginning of the 7th century—the period of transition from

Arianism

Arianism (, ) is a Christology, Christological doctrine which rejects the traditional notion of the Trinity and considers Jesus to be a creation of God, and therefore distinct from God. It is named after its major proponent, Arius (). It is co ...

to Catholicism in the Visigothic kingdom—excepting a brief incursion of Byzantine power.

Under Visigothic rule, Malaca became an episcopal see. The earliest known bishop was Patricius, consecrated about 290, and present at the Council of Eliberis (Elvira).

After the division of the Roman Empire and its

final crisis

"Final Crisis" is a crossover storyline that appeared in comic books published by DC Comics in 2008, primarily the seven-issue miniseries of the same name written by Grant Morrison. Originally DC announced the project as being illustrated solely ...

in 476, Malaca was one of the areas of the peninsula affected by further migrations of the Germanic tribes, especially the

Silingi

The Silings or Silingi (; – ) were a Germanic tribe, part of the larger Vandal group. The Silingi at one point lived in Silesia, and the names ''Silesia'' and ''Silingi'' may be related.Jerzy Strzelczyk, "Wandalowie i ich afrykańskie państw ...

Vandals, who during the 5th century introduced the Arian heresy to western Europe. The province lost much of the wealth and infrastructure achieved under Roman rule, but maintained a certain prosperity, even as it suffered the destruction of some of its most important towns, as at Acinipo, Nescania, and Singilia Barba, which were not rebuilt.

Byzantine Malaca

The Byzantine Emperor

Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

(482–565) conceived a military and foreign policy, the

renovatio imperii

''Renovatio imperii Romanorum'' ("renewal of the empire of the Romans") was a formula declaring an intention to restore or revive the Roman Empire. The formula (and variations) was used by several emperors of the Carolingian and Ottonian dynast ...

, to recover the territories which had formerly comprised the Western Roman Empire and were under the rule of the barbarians. It was led by his brilliant general,

Belisarius

BelisariusSometimes called Flavia gens#Later use, Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see (; ; The exact date of his birth is unknown. March 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under ...

, and succeeded in regaining North Africa, southern Iberia and most of Italy.

Malaca and the surrounding territory were conquered in 552; Malaca then became one of the most important cities of the Byzantine province of Spania.

The city was conquered and sacked again by the Visigoths under King

Sisebut

Sisebut (; ; also ''Sisebuth'', ''Sisebur'', ''Sisebod'' or ''Sigebut''; 565 – February 621) was Visigothic Kingdom, King of the Visigoths and ruler of Hispania, Gallaecia, and Septimania from 612 until his death in 621. His rule was marked ...

in 615. In 625, during the reigns of the Visigothic king

Suintila (or Swinthil) and the Byzantine Emperor

Heraclius

Heraclius (; 11 February 641) was Byzantine emperor from 610 to 641. His rise to power began in 608, when he and his father, Heraclius the Elder, the Exarch of Africa, led a revolt against the unpopular emperor Phocas.

Heraclius's reign was ...

, the Byzantines definitively abandoned their last settlements in the narrow area they still held.

It is known that Sisebut devastated much of the city, and although it remained an episcopal see and the site of a mint built by

Sisenand,

its population was drastically reduced and its prosperous economy ruined. There is clear documentary evidence of the violent destruction of at least one commercial district. Such was the devastation that the first Islamic invaders of the old Visigothic county of Malacitana initially had to locate their capital in the interior, at

Archidona

Archidona is a town and municipality in the province of Málaga, part of the autonomous community of Andalusia in southern Spain. It is the center of the comarca of Nororiental de Málaga and the head of the judicial district that bears its name. ...

.

Eight centuries of Muslim rule

The

Chronicle of 754, covering the years 610 to 754, indicates the Arabs began disorganised raids and only undertook to conquer the peninsula with the fortuitous deaths of

Roderic

Roderic (also spelled Ruderic, Roderik, Roderich, or Roderick; Spanish language, Spanish and , ; died 711) was the Visigoths, Visigothic king in Hispania between 710 and 711. He is well known as "the last king of the Goths". He is actually an ex ...

and much of the Visigothic nobility. They were probably killed at the

Battle of Guadalete

The Battle of Guadalete was the first major battle of the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula, fought in 711 at an unidentified location in what is now southern Spain between the Visigoths under their king, Roderic, and the invading forces o ...

against an invading force of Muslim Arabs and Berbers under the command of

Ṭāriq ibn Ziyad. Roderic was the last king of the Visigoths, but his disputed succession to the throne and the resulting internal conflict may have contributed to the collapse of the Visigoth kingdom before the advance of the Moorish invaders. The Visigoths elected their kings outright rather than making the throne hereditary by

right of succession, but Roderic had apparently led a coup and usurped the throne in 711. Hearing of Tariq's landing, Roderic had gathered his followers and engaged the Arab-Berber invaders, making several expeditions against them before he was deserted by his troops and killed in battle in 712.

[Collins, p.133] After Roderic's defeat, the Muslim armies, reinforced by more troops from Africa, faced little opposition as they moved north. By 714, the Muslims were in control of all of Hispania, except for a narrow strip along the north coast. Malacitana was settled by Arabs and Berbers, while much of the indigenous population fled into the mountains. The Muslims called the city Mālaqa (Arabic: مالقة), designating it as part of the region of

al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

. The military and political leader

Abd al-Aziz ibn Musa became governor of the city, but his tenure did not last long. For forty years following his assassination in 716, al-Andalus was filled with chaos and turmoil as the Hispano-Romano residents rebelled against Muslim rule, until in 743 Málaga came decisively under Arab domination.

The invading forces were mostly Berber tribesmen from the Maghreb (the northwest of Africa), under Arab leadership. They and the other Muslim soldiers fighting with them were united by their religion. After the battle of Guadalete the city passed into the hands of the Arabs, and the bishopric was suppressed. Málaga then became for a time a possession of the Caliphate of Cordova. After the fall of the Umayyad dynasty, it became the capital of a distinct kingdom (taifa), dependent on Granada.

The ''Muladi'' or ''

Muwallads'', were in almost constant revolt against the Arab and Berber immigrants who had carved out large estates for themselves, which were farmed by Christian serfs or slaves. The most famous of these revolts was led by a rebel named

Umar ibn Hafsun in the region of Málaga and the Ronda mountains. Ibn Hafsun ruled over several mountain valleys for nearly forty years, having the castle Bobastro (Arabic: بُبَشْتَر) as his residence.

He rallied disaffected muwallads and mozárabs to his cause, and eventually renounced Islam in 889 with his sons and became a Christian. He took the name Samuel and proclaimed himself not only the leader of the Christian nationalist movement, but also the champion at the same time of a regular crusade against Islam. However, his conversion soon cost him the support of most of his Muwallad supporters who had no intention of ever becoming Christians, and led to the gradual erosion of his power.

When Hafs, son of Umar ibn Hafsun, finally laid down his arms in 928 and surrendered the town of Bobastro,

Abd-al-Rahman III imposed the Islamic system of civil organisation in Mālaqa province. This allowed a new population distribution that encouraged urban development and the proliferation of farms in rural areas, as opposed to the pattern of

feudalism

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

dominant in the rest of Europe. The farmers practiced intensive irrigation-based agriculture, while artisanry and trade flourished in the cities—leading to prosperity and an era of peace in the province.

Surrounded by a walled enclosure with five large gates, Mālaqa city itself thrived; the

Alcazaba, a Moorish citadel, was built in the mid-11th century on Mount

Gibralfaro, a hill in the center of the city overlooking the port. The fortress comprised two walled enclosures situated to conform to the steep terrain. The Alcazaba was fortified with three walls towards the sea, and two facing the town.

Antonio de Nebrija

Antonio de Nebrija (14445 July 1522) was the most influential Spanish humanist of his era. He wrote poetry, commented on literary works, and encouraged the study of classical languages and literature, but his most important contributions were i ...

counted, in the circumference of the castle, 110 large towers, and a great number of turrets, the largest of which were those that surrounded the Atarazanas.

[Carter, p.308-309] New suburbs formed as the city expanded, including walled neighborhoods, within which evolved the ''adarves'' characteristic of medieval Islamic cities; these were streets leading to private homes, with a gate at the beginning. The banks of the ''Wad-al-Medina'' (Guadalmedina river) were lined with orchards, and crossed from east to west by a route that connected the harbor and the fortress inside the city walls. Near the enclosure rose neighborhoods settled by Genoese and Jewish merchants, independent of the rest of the city. The Jewish quarter of the

medina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

produced one of Mālaqa's most illustrious sons: the Jewish philosopher and poet, Solomon Ibn Gabirol, who would be the first to use the term "Paradise City" to refer to his hometown.

Besides the splendid

Alcazaba, the marble gate of the

Nasrid shipyards ''(atarazanas)'', and part of the Jewish quarter, other vestiges of Moorish Mālaqa remain today: a section of the monumental cemetery of Yabal Faruh, considered the largest in Andalusian Spain, has been excavated on the slopes of Mount Gibralfaro. Two burial mosques, part of a mausoleum, and the remains of a pantheon (a temple dedicated to all the gods) have been preserved as well on Calle Agua. The mosques date from the 12th and 13th centuries and were built on a quadrangular plan with single naves and

mihrab

''Mihrab'' (, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "''qibla'' wall".

...

s.

Taifa of Mālaqa

In 1026 Mālaqa became the capital of the

Taifa of Málaga, an independent Muslim kingdom which existed for four distinct periods: it was ruled by the

Hammudid dynasty as the Rayya Cora in the

Caliphate of Córdoba

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

from 1026 to 1057, by the Zirí dynasty from 1073 to 1090, by the Hassoun from 1145 to 1153 and the Zannun from 1229 to 1239 when it was finally conquered by the

Nasrid Kingdom of Granada.

Vestiges of the urban plan of this era are preserved in the historical center: in its two principal monuments, the Alcazaba and the castle of Gibralfaro; and ''La Coracha'', a walled passage of double ramparts built to secure communication between the fortress and the Alcazaba. Mālaqa had two suburbs outside the walls and enjoyed a thriving trade with the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

. The city had an important pottery industry—terra cotta tiles were fired there and its ornamental vases, called Málagan lusterware, came to be recognised throughout the Mediterranean. Trade was regulated by the "Proper Governance of the Souk", a treatise on

Hisba (business accountability) written by Abu Abd Allah al-Saqati of Mālaqa, in the 13th century.

Nasrid Mālaqa

After the death in 1238 of Ibn Zannun, the last king of the Mālaqa Taifa, the city was captured in 1239 by

Muhammad I of Granada

Abu Abdullah Muhammad ibn Yusuf ibn Nasr (; 22 January 1273), also known as Ibn al-Ahmar (, ) and by his honorific al-Ghalib billah (, ), was the first ruler of the Emirate of Granada, the last independent Muslim state on the Iberian Peninsula, ...

and became part of the Moorish kingdom of Granada. His brother Isma`il became the governor of Mālaqa during Mohammed's reign (until 1257). When Isma'il died, Mohammed ibn Al-Ahamar raised his nephews Mohammed and Abu Said Faraj, the latter of whom would become governor of Mālaqa in his father's place. Mālaqa remained under the rule of the Nasrid dynasty till the reconquista of the Catholic Monarchs.

During the reign of the Nasrids, Mālaqa became a center of shipbuilding and international trade.

In 1279, Muhammad II signed an economic and trade agreement with the Republic of Genoa,

and Genoese traders obtained a privileged position in the port.

By the mid-fourteenth century, Mālaqa was the maritime gateway of the Nasrid kingdom, assuming many of the functions formerly held by Almería.

The Genoese established a network of trade centers under their control around the Mediterranean Sea and connected the Iberian trade with that of northern Africa by Atlantic routes as well. Many of these communities organised cooperative institutions known as ''consulados'' (consulates) to connect merchants regionally and internationally. A ship's registry (logbook) written by Filippo de Nigro in 1445 shows that Mālaqa was an important part of this trade network and describes the regional system controlled by the Genoese

Spinola family

The House of Spinola, or Spinola family, is a Genoese noble family which played a leading role in the Republic of Genoa. Their influence was at its greatest extent in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

Notable members

Guido Spinola was ...

. As a stopover on the coastal navigation routes, Mālaqa became a crucial business hub with the rise of associated commercial activity.

[Porras, 2010]

Fine ceramics made in Mālaqa were frequently given as diplomatic gifts. In the mid-15th century the king of Granada sent ambassadors to the Mameluke sultan in Cairo bearing them as presents. The workshops for their manufacture were located in the suburb known as Fontanalla in the foothills of the mountain El Ejido.

The Mālaqa shipyards, the ''Atarazanas'', were built during the reign (1354–1391) of Mohammed V to strengthen his political and military power. The main building, constructed as a naval workshop with probably some limited use as a warehouse, was one of Mālaqa's largest and most impressive, and was noted for its seven monumental horseshoe arches. During this period the coast was further inland and the Atarazanas was at the edge of the sea, so low that the water flowed in and formed a basin capacious enough to contain 20 galleys. The walls around it were eighty feet high; the arches, for the reception of ships, were sixty feet high by thirty wide, and twelve feet thick, and each of these arches had its own gates.

The southern facade was described by

Hieronymus Münzer in 1494: it had six open arches providing access to a high vaulted nave with transverse ribs under which the ships anchored. The seventh arch, located on the left, and still in existence today, was the entranceway to a large columned courtyard. There are two heraldic shields above the arch, designed in Castilian style and having diagonal bands inscribed in Arabic with the Nasrid motto, ''

Wah lâ ghâlib ilâ Allâh'' (There is no victor other than God). At the western corner was a square tower attached to the portal and from there a wall joined the ''Borch Hayta'', or ''Torre del Clamor'', which closed the natural inlet between it and the Genoese castle, which is no longer extant. The tower served as a minaret for the muezzin to call the faithful to prayer at the mosque.

At this time about 15,000 people lived in Mālaqa; most of them were Muslims strictly observant of religious orthodoxy as taught by the

Fuqahā', the expert jurists of Islamic law. There was a sizable minority of Jews, while the presence of Christians was reduced to those captives taken in war, enslaved, and forced to labor in the shipyards, where light ships were built for patrolling the coast. The small colony of foreign traders was mostly Genoese. The governor of the city was typically a Moorish prince serving as a representative of the Sultan, and resided in the Alcazaba with his retinue of personal secretaries and lawyers. The large massive city walls, with their many towers, monumental gates and moat, all surmounted by the fortress of Gibralfaro, made the defences of the city nearly impregnable.

The generally mountainous land around Mālaqa did not favor agriculture, but the Muslim peasants organised an efficient irrigation system, and with their simple tools were able to grow crops on the slopes; spring wheat being the staple of their diet. An unusual feature of Mālaqi

viticulture

Viticulture (, "vine-growing"), viniculture (, "wine-growing"), or winegrowing is the cultivation and harvesting of grapes. It is a branch of the science of horticulture. While the native territory of ''Vitis vinifera'', the common grape vine ...

was the interplanting of grape vines and fig trees, grown mostly in the

Axarquía

Axarquía () is a in the province of Málaga, Andalusia in southern Spain. It is the wedge-shaped area east of Málaga. Its name is traced back to Arabic (, meaning "the eastern egion). It extends along the coast and inland. Its coastal towns m ...

area east of Mālaqa. The raising of livestock, absent pigs because of Muslim dietary restrictions, played only a secondary role in the local economy. The production of olives was low, and olive oil was actually imported from the

Aljarafe

Asharaf or Axarafe is the olive-cultivating hilly region around the Guadiamar river located between Seville and Niebla in Andalusia.

Olive production

Olive oil was a significant commodity in 16th century Seville, exported to "all the Kingdom, t ...

. Other fruit and nut trees, such as figs, hazelnuts, walnuts, chestnuts, and almonds were abundant and provided important winter foodstuffs, as did the mulberry trees introduced by the Arabs, their fruit being used to make juice.

Trade in hides and skins and leatherworking was a major industry in Mālaqa, as was

metalsmith

A metalsmith or simply smith is a craftsperson fashioning useful items (for example, tools, kitchenware, tableware, jewelry, armor and weapons) out of various metals. Smithing is one of the oldest list of metalworking occupations, metalworking o ...

ing, especially of knives and scissors; gold inlaid ceramics and porcelain were manufactured as well. The production of silk textiles was still important and closely linked to the Moorish sector of the population. Light ships for patrolling the coast were built in the Atarazanas.

In 1348, while the black plague ravaged Europe, the Alcazaba and the castle of Gibralfaro took their final shape. The city had several gates that allowed passage through the walls, some of which still stand today, such as the ''Puerta Oscura'' (Dark Gate) and the ''Puerta del Mar'' (Sea Gate). Looming over the port, the

Alcazaba was the Moorish citadel built on the hill called Mount Gibralfaro in the center of the city, on whose summit was the castle. The citadel and the castle were connected by a corridor known as ''La Coracha'' between two zig-zagging walls that followed the contours of the land. Erected in the 11th century, the Alcazaba combined defensive fortifications with residential palaces and inner gardens; it was fortified with three walls towards the sea, and two facing the town.

Antonio de Nebrija

Antonio de Nebrija (14445 July 1522) was the most influential Spanish humanist of his era. He wrote poetry, commented on literary works, and encouraged the study of classical languages and literature, but his most important contributions were i ...

counted, in the circumference of the castle, 110 large towers, besides a great number of turrets. The same walls also enclosed the whole compound, though each building had its own entrance. The ''Puerta de los Arcos'' (Gate of the Arch) of the ''Torre del Tinel'' (Tower of Tinel) was the entrance to the Nasrid palace in the enclosure dating to the 13th and 14th centuries. Remnants of the old city wall remain today in Calle Alamos and Calle Carreteria.

In May 1487 Ferdinand and Isabella began their

siege of Mālaqa, which after a desperate resistance was compelled to surrender. The victory was a bloody episode in the war for the conquest of the Kingdom of Granada, but the Christian religion was restored, and with it the episcopal see.

The Catholic Monarchs had already taken the city of Ronda by storm on 22 May 1485. Its warden (''arraez''), the Moorish chieftain Hamet el Zegrí (Hamad al-Tagri), refused Ferdinand and Isabella's offer to accept his vassalage, and took refuge in Mālaqa, where he led the Muslim resistance. The siege began on May 5, 1487; the Nasrid troops held out till August, when only the Alcazaba, under the command of the merchant Ali Dordux, and the fortress of the Gibralfaro, under the command of Hamet el Zegrí and Ali Derbal, still resisted.

The

Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Isabella I of Castile, Queen Isabella I of Crown of Castile, Castile () and Ferdinand II of Aragon, King Ferdinand II of Crown of Aragón, Aragon (), whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of ...

besieged Mālaqa for six months, one of the longest sieges in the

Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

. They cut off the supplies of food and water to the city, forcing its Muslim garrison to eventually surrender. On 13 August the Castilian army, over 45,000 strong, took the city defended by 15,000 African (Maghrebi) mercenaries and Mālaqi warriors. King Ferdinand decided to make an example of the resistors and refused to grant them an honorable capitulation, The civilian population was punished by enslavement or execution, with the exception of twenty-five families allowed to stay as Mudéjar converts in the Moorish compound.

On August 18, Ali Dordux, after negotiating his group's status as mudejars, surrendered the citadel, but Gibralfaro had to be taken by assault, and its defenders were sold as slaves, while Hamet el Zegrí was executed. The conquest of Mālaqa was a final blow to the Nasrid kingdom of Granada, which lost its principal maritime port.

The troops who served in the army of the Spanish victors were paid by the customary division of properties, the ''repartimientos''. Between 5,000 and 6,000 Christians from Extremadura, Leon, Castile, Galicia and the

Levante repopulated the province, of which about a thousand settled in the capital, now called by its Castilian name, Málaga. The city spread beyond its walls with the creation of the religious convents of La Trinidad, Los Angeles, Santuario de la Victoria, and the Capuchin monastery.

Early Modern Era

The Mudéjars (1485–1501)

The word ''Mudéjar'' is a Medieval Spanish corruption of the Arabic word ''Mudajjan'' (مدجن), meaning "domesticated", in reference to the Muslims who submitted to the rule of the Christian monarchs. By this means many Islamic communities survived in the Málaga area after the Reconquista, protected by the capitulations they signed during the war. These covenants were feudal in nature: the Moors recognised the sovereignty of the Catholic Monarchs, surrendered their fortresses, delivered all Christian captives, and committed to continue paying traditional taxes. In return, they received protection for their persons and property, and legal assurances that their beliefs, laws and social customs would be respected.

The

Treaty of Granada

The Treaty of Granada, also known as the Surrender of Granada or the Capitulations, was signed and ratified on November 25, 1491, between Boabdil, the sultan of Granada, and Ferdinand and Isabella, the King and Queen of Castile, León, Aragon ...

had protected religious and cultural freedoms for Muslims and Jews in the imminent transition from being the Emirate of Granada to being a province of Castile. After the

fall of Granada in January 1492, Mudéjars kept their protected religious status, but in the mid-16th century, they were forced to convert to Christianity. From that time, because of suspicions that they were not truly converted, they were known as

Moriscos

''Moriscos'' (, ; ; " Moorish") were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Catholic Church and Habsburg Spain commanded to forcibly convert to Christianity or face compulsory exile after Spain outlawed Islam. Spain had a sizeable M ...

. In 1610 those who refused to convert to Christianity were expelled from Málaga.

The layout of the Muslim city was changed in the 16th century to suit the needs of the Christian conquerors, beginning with the construction of a wide road to allow the transport of merchandise from the main square, the ''Plaza Mayor'' (now ''Plaza de la Constitución'') to the ''Puerta del Mar'' gate, in present-day Calle Nueva. At this time also the transept, nave and main chapel of the

Cathedral of Málaga were built on the foundations of the old mosque. New churches and convents raised outside the walled enclosure of the city attracted the populace, leading to the formation of new neighborhoods like La Trinidad and El Perchel.

The artisanal productions of Málaga included textiles, leather, clay, metal, wood, building construction and prepared food. The city became a shipping center for export of the surplus agricultural output of the kingdoms of Cordoba, Jaen and Granada, as well as an entry point into Andalusia for a range of goods.

16th–18th centuries

In 1585, Philip II ordered a new survey of the port, and in 1588 commissioned the building of a new dam in the eastern part, along with repairs of the Coracha. In the next two centuries the port was expanded both to the east and west.

Trade, dominated by foreign merchants,

was the main source of wealth in Málaga of the 16th century, with wine and raisins as the principal commodity exports. The public works on the port as well as those on the Antequera and Velez roadways provided the necessary infrastructure for distribution of the renowned Málaga wines. The production of silk textiles was still important and closely linked to the Moorish part of the population. The real estate of the aristocracy was increased through the "

refeudalization" occasioned by the sale of manors, a policy implemented by the nobility who monopolised high office. The mercantile operations of the town and its port were important to the national Spanish economy and the raising of revenue for the

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

government, but they suffered from the general corruption of the time, including the sale of important offices.

From the 17th century to the 18th century, the city entered a period of decline,

a consequence not only of the social disruption caused by the expulsion of the Moors, but also of flooding of the Guadalmedina River and several successive crop failures. Other disasters and disruptive events of the 17th century included earthquakes, explosions of gunpowder mills, and the conscription of men to serve in battle; nevertheless, the population increased.

Málaga, as headquarters of the ''Capitanía General de Granada'' (Captaincy General of the Kingdom of Granada) on the coast played an essential role in the foreign policy of the Bourbon kings of Spain. The regional military, the supply of the North African presidios, and the defence of the Mediterranean were administered in the city. This involved massive defence spending on fortification of the harbor, the building of coastal towers and the organising of militias. The

loss of Gibraltar to a

Second Grand Alliance force and an inconclusive naval engagement

off Málaga of 1704 made the city the key to military defence of the Strait.

During the second half of the 18th century Málaga solved its chronic water supply problems with the completion of one of the largest infrastructure projects carried out in Spain at the time: the building of the Aqueduct of San Telmo,

designed by the architect

Martín de Aldehuela. After the success of this impressive feat of engineering, the city enjoyed an economic recovery with a new expansion of the port, the revival of the works of the Cathedral, and the erection of the new Customs building, the Palacio de la Aduana, begun in 1791. The peasantry and the working classes still made up the vast majority of the population, but the emergence of a business-oriented middle-class lay the foundations for the 19th-century economic boom.

By the 18th century, the port of Málaga, the linchpin of the city's economy, was again one of the most important on Andalusia's Mediterranean coast.

Following the Decree of Free Trade in 1778 by

King Charles III

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

, which allowed the Spanish American ports to trade directly with ports in Spain, commercial traffic at the port increased further, and the population grew considerably. Major urban renovations were made in Málaga under the influence of the ideas of the

European Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

, bestowing on it many of its most characteristic features: the Cathedral, the harbor of the port and its Customs House, the Alameda, and the Antequera and Velez roadways. In 1783 a bayfront boulevard, the Paseo de la Alameda, a symbol of urban prosperity, was built on land reclaimed from the sea with sand dredged from the Guadalmedina River. By 1792 mansions had risen on either side of the avenue in the fashionable new residential area settled by the Málaga merchant class.

19th century

The 19th century was a turbulent time of political, economic and social crisis in Málaga. Spanish involvement in the

War of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition () was a European conflict lasting from 1805 to 1806 and was the first conflict of the Napoleonic Wars. During the war, First French Empire, France and French client republic, its client states under Napoleon I an ...

opened up her merchant fleet to attacks by

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

warships while the deadly 1803–1804 epidemic of Yellow Fever killed more than 26,000 people in Málaga alone. The city suffered the further ravages of the Peninsular War, conflicts between royal

absolutists and liberals, the end of the transatlantic trade with the Americas, the collapse of its industry, and finally the

phylloxera

Grape phylloxera is an insect pest of grapevines worldwide, originally native to eastern North America. Grape phylloxera (''Daktulosphaira vitifoliae'' (Fitch 1855) belongs to the family Phylloxeridae, within the order Hemiptera, bugs); orig ...

epidemic that destroyed the vineyards of the region.

On

2 May 1808 the people of Madrid rebelled against the French occupation of their city; this event was followed by the abdication of the royal family in

Bayonne

Bayonne () is a city in southwestern France near the France–Spain border, Spanish border. It is a communes of France, commune and one of two subprefectures in France, subprefectures in the Pyrénées-Atlantiques departments of France, departm ...

and the proclamation of Napoleon's brother Joseph as king of Spain. When news of the uprising reached Málaga, its citizens revolted against the French invaders, with the guerrillas in the mountains putting up the fiercest resistance.

The Military Governor of Málaga province, General

Theodor von Reding

Field Marshal Theodor von Reding (5 July 1755 – 23 April 1809) was a Spanish Army officer who served as the Captain General of Catalonia in 1809.

Biography

Reding was born in Schwyz, Switzerland, to Theodor Anton Reding and Magdalena Freule ...

, held command of the First Division of the Spanish Army of Andalusia and was architect of the Spanish victory in the

Battle of Bailen

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

during the (

Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

). The French encountered strong resistance in Málaga and left much of the city in ruins when they withdrew. The war and revolts against Napoleon's occupation led to the adoption of the

Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy (), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz () and nicknamed ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitution of Spain and one of the earliest codified constitutions in world history. The Constitution ...

, later a cornerstone of European liberalism, by the

Cortes of Cádiz

The Cortes of Cádiz was a revival of the traditional ''Cortes Generales, cortes'' (Spanish parliament), which as an institution had not functioned for many years, but it met as a single body, rather than divided into estates as with previous o ...

. Málaga elected representatives to send to the national legislative assembly and a new constitutional Town Council which immediately implemented reconstruction plans. The French were decisively defeated at the

Battle of Vitoria

At the Battle of Vitoria (21 June 1813), a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British, Kingdom of Portugal, Portuguese and Spanish Empire, Spanish army under the Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, Marquess of Wellington bro ...

in 1813, and the following year,

Ferdinand VII

Ferdinand VII (; 14 October 1784 – 29 September 1833) was King of Spain during the early 19th century. He reigned briefly in 1808 and then again from 1813 to his death in 1833. Before 1813 he was known as ''el Deseado'' (the Desired), and af ...

was restored as King of Spain. The burden of war had destroyed the social and economic fabric of Spain and ushered in an era of social turbulence, political instability and economic stagnation.

Although the ''juntas'', which forced the French to leave Spain, had sworn by the liberal

Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy (), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz () and nicknamed ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitution of Spain and one of the earliest codified constitutions in world history. The Constitution w ...

, Ferdinand openly held that it was too liberal for the country. On his return to Spain on April 16, 1814, he refused to swear by the constitution himself, and continued to rule in the authoritarian fashion of his forebears. Thus the first bourgeois revolution ended in 1814.

[Karl Marx, p. 391] The reign of Ferdinand VII from 1814 to 1820 was a period of a stagnant economy and political instability. Much of the country was devastated after the Peninsular War, and government coffers were drained to fight against the

independence movements

Below are the articles listing active separatist movements by continent:

* List of active separatist movements in Africa

*List of active separatist movements in Asia

*List of active separatist movements in Europe

* List of active separatist m ...

in the Latin American colonies. Political conflict between liberals and royal absolutists further diverted energy and resources needed to rebuild the country.

There were several attempts to install a liberal regime during the absolutist reign (1814–1820). In 1820, an expedition intended for the American colonies revolted in

Cádiz

Cádiz ( , , ) is a city in Spain and the capital of the Province of Cádiz in the Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia. It is located in the southwest of the Iberian Peninsula off the Atlantic Ocean separated fr ...

. When armies throughout Spain pronounced themselves in sympathy with the revolters led by

Rafael del Riego

Rafael del Riego y Flórez (7 April 1784 – 7 November 1823) was a Spanish general and liberal politician who played a key role in the establishment of the Liberal Triennium (''Trienio liberal'' in Spanish). The failure of the Cádiz army to se ...

, Ferdinand was forced to relent. On 9 March 1820 he finally accepted the liberal Constitution of 1812, and appointed new ministers of state, thus ushering in the so-called

Liberal Triennium ''(Trienio Liberal)'', a period of three years of liberal government and popular rule in Spain. This was the start of the second bourgeois revolution in Spain, which would last from 1820 to 1823. Once again in the revolution of 1820, it was the independent towns such as Málaga that led the drive for constitutional change in Spain. Ferdinand himself was placed under effective house arrest for the duration of the liberal experiment.

The tumultuous

three years of liberal rule that followed were marked by various absolutist conspiracies. The liberal government was looked on with hostility by the

Congress of Verona

The Congress of Verona met at Verona from 20 October to 14 December 1822 as part of the series of international conferences or congresses that opened with the Congress of Vienna in 1814–15, which had instituted the Concert of Europe at the ...

in 1822, and France was authorised to intervene. A French army under the command of

Duke of Angoulême

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

, invaded Spain in the so-called

Spanish expedition and overwhelmed the armies of the liberal government with massive force. Ferdinand was restored as absolute monarch in 1823, marking the end of the second Spanish bourgeois revolution.

During the "

Ominous Decade" (1823–1833), the name given to this period of return to the reactionary power of absolutism, the liberals suffered under a wave of repression and acts of vengeance. In 1831, the liberal general José María Torrijos, who fought against the absolutist regime of Ferdinand VII and for the restoration of the Constitution of 1812, set his field of operations in Málaga province. He and his men were captured in

Alhaurin de la Torre after their betrayal by the governor of the city; they were executed by firing squad on the beach of San Andrés. Torrijos' remains are buried under the obelisk erected in his honor at the Plaza de la Merced.

As Málaga pioneered the Industrial Revolution in Spain, its educated and entrepreneurial merchant class agitated for modernity in government, making Málaga one of the most rebellious cities of the country. The bourgeoisie led several uprisings in favor of a more liberal regime to encourage free commercial enterprise. In 1834, soon after the death of Ferdinand VII, a revolt was organised against the inefficiency of the government of the

Count of Toreno ''(Conde de Toreno)'', who had been appointed prime minister by the queen regent,

Maria Christina on 7 June. His tenure in the premiership lasted only till 14 September. A year later the civil and military governors of Málaga, the Conde Donadio and Señor San Justo, were killed in a violent insurrection.

[Blackwood's, p.572]

The

Ecclesiastical Confiscations of Mendizabal in 1836 resulted in a new initiative to modernize the city. Religious convents had accumulated property since the reconquest, and by the end of the 18th century a fourth of the urban properties bounded by the ancient city walls belonged to religious orders or similar fraternal organisations. With the seizure of the church holdings, many of these buildings were demolished and new buildings or streets or squares were built to replace them. The site of the convent of San Pedro de Alcantara became the ''Plaza del Teatro'', while the convent of San Francisco was replaced by an architecturally refined square which became the home of the Lyceum and the Philharmonic Society.

Economic expansion and industrialisation (1833–1868)

The second half of the 19th century began a period of prosperity in Málaga, with an economy energised by the resumption of traditional mercantile activities and new industrial employment. This positioned the city as an important European manufacturing centre; urban renewal projects and the modernisation of local infrastructure were initiated by local government. Manuel Agustin Heredia's ironworks, La Constancia, located in San Andrés, started a run of productivity in 1834 that made it the country's leading iron foundry.

Commerce grew significantly as the city attracted business entrepreneurs, and powerful families rose from the merchant class, some gaining influence in national politics. Notable among them were the Larios and the Lorings, the conservative politician Canovas del Castillo, the industrialist Manuel Agustin Heredia, and the

Marquis of Salamanca.

From 1834 to 1843, in the period known as Spain's third bourgeois revolution, the country was ruled under the liberal government of the

Progressive Party ''(Partido Progresista)''. After these years of progressivist domination, the

Moderate Party

The Moderate Party ( , , M), commonly referred to as the Moderates ( ), is a Liberal conservatism, liberal-conservative*

*

*

*

* List of political parties in Sweden, political party in Sweden. The party generally supports tax cuts, the free ma ...

''(Partido Moderado)'' gained control. It held power continuously during the so-called ''