History Of Montana on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

This is a broad outline history of the state of

The

The

On April 30, 1803, the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed by representatives of the U.S. at Paris, France. The

On April 30, 1803, the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed by representatives of the U.S. at Paris, France. The

Major John Owen

arrived in the valley and set up camp north of St. Mary's. In time, Major Owen established a trading post and military strong point named Fort Owen, which served the Native people, settlers, and missionaries in the valley.

Following the

Following the

The

The

Efforts to write

Efforts to write

Cattle ranching has long been central to Montana's history and economy. Cattle ranching came early to Montana with the entrepreneurship of Johnny Grant in the Deer Lodge Valley in the late 1850s, who traded fat cattle to settlers in exchange for two trail-worn (but otherwise healthy) animals. He later sold his ranch to Conrad Kohrs, who developed a major cattle empire in the area. Today, Grant's core homestead is the Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site on the edge of

Cattle ranching has long been central to Montana's history and economy. Cattle ranching came early to Montana with the entrepreneurship of Johnny Grant in the Deer Lodge Valley in the late 1850s, who traded fat cattle to settlers in exchange for two trail-worn (but otherwise healthy) animals. He later sold his ranch to Conrad Kohrs, who developed a major cattle empire in the area. Today, Grant's core homestead is the Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site on the edge of

Failures mixed with successes in Montana business history. The closure in 1964 of the Missoula Brewing Company exemplified the difficulties small businesses faced when competing with large producers. Opened in 1900, the brewery closed during Prohibition but resumed production of its Highlander brand in 1933. Government regulation and taxation, isolation, out-of-state competition, and limited promotion reduced the Highlander share of the market following World War II. The brewery closed in 1964 to make way for an interstate highway, ending the era of Montana-brewed beer. Rainier bought the Highlander name, but the former failure in quality control had hurt the Highlander reputation.

Many entrepreneurs built stores, shops, and offices along Main Street. The most handsome ones used pre-formed, sheet iron facades, especially those manufactured by the Mesker Brothers of St. Louis. These neoclassical, stylized facades added sophistication to brick or wood-frame buildings throughout the state.

Failures mixed with successes in Montana business history. The closure in 1964 of the Missoula Brewing Company exemplified the difficulties small businesses faced when competing with large producers. Opened in 1900, the brewery closed during Prohibition but resumed production of its Highlander brand in 1933. Government regulation and taxation, isolation, out-of-state competition, and limited promotion reduced the Highlander share of the market following World War II. The brewery closed in 1964 to make way for an interstate highway, ending the era of Montana-brewed beer. Rainier bought the Highlander name, but the former failure in quality control had hurt the Highlander reputation.

Many entrepreneurs built stores, shops, and offices along Main Street. The most handsome ones used pre-formed, sheet iron facades, especially those manufactured by the Mesker Brothers of St. Louis. These neoclassical, stylized facades added sophistication to brick or wood-frame buildings throughout the state.

Prospectors discovered numerous small oil fields in the state after 1910. The oil went to small local refineries which marketed the gasoline locally through a network of service stations using the same brand name. After 1945 majors such as Standard Oil of New Jersey (now

Prospectors discovered numerous small oil fields in the state after 1910. The oil went to small local refineries which marketed the gasoline locally through a network of service stations using the same brand name. After 1945 majors such as Standard Oil of New Jersey (now

''Missoulian'', 25 December 2010 The number of registered users jumped from 2000 in 2009 to more than 30,000 by June 2011. The 2011 Montana Legislature attempted to repeal legalization, but their bill was vetoed by Gov.

''Great Falls Tribune'', Dec. 24, 2011

/ref> Court action ensued, and in the summer of 2011, a state District Court judge blocked parts of the law from taking effect. Advocates for medical marijuana sought to put a new referendum on the statewide ballot for 2012. The court case is on appeal to the Montana Supreme Court. On November 4, 2020 the Montana Supreme Court has legalized Marijuana completely.Mike Dennison, "Medical marijuana: State appeals ruling that blocked restrictions in Montana law", ''Missoulian'' 9 August 2011

/ref>

From Wilderness to Statehood: A History of Montana, 1805–1900

' (Bindfords & Mort, 1957) 627pp. * Howard, Joseph Kinsey.

Montana: High, Wide, and Handsome

' (1943; with new forward, University of Nebraska Press, 2003) * , the standard scholarly history * Smith, Duane A. ''Rocky Mountain Heartland: Colorado, Montana, and Wyoming in the 20th Century'' (2008) 305pp compares the interplay of tradition and modernization in the three states *Stout, Tom. ''Montana, its story and biography; a history of aboriginal and territorial Montana and three decades of statehood'' (1921

online free vol 1 vol 1 962pp

detailed history to 1920; biographies in vol 2 and 3 * WPA Federal Writers Project. ''Montana: A State Guide Book'' (Viking Press, 1939) classic guide to history, culture and every tow

online free Kindle edition

Capitalism on the Frontier: Billings and the Yellowstone Valley in the Nineteenth Century

' (University of Nebraska Press, 1993) * Hedges, James B.

The Colonization Work of the Northern Pacific Railroad

, ''Mississippi Valley Historical Review'' Vol. 13, No. 3 (Dec., 1926), pp. 311–342 * Jensen, Vernon H.

Heritage of Conflict: Labor Relations in the Nonferrous Metals Industry up to 1930

' (Cornell University Press, 1950)

excerpt

* Morrison, John, and Catherine Wright Morrison, eds. ''Mavericks: The Lives and Battles of Montana's Political Legends'' (2003), chapters on

Thomas J. Walsh: A Senator from Montana

' (1955). * Spritzer, Donald F. ''Senator James E. Murray and the Limits of Post-War Liberalism'' (1985). * Swibold, Dennis L. ''Copper chorus: mining, politics, and the Montana press, 1889–1959'' (2006) * Waldron, Ellis L. ''Montana politics since 1864: an atlas of elections'' (1958) 428 pages

Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

in the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

.

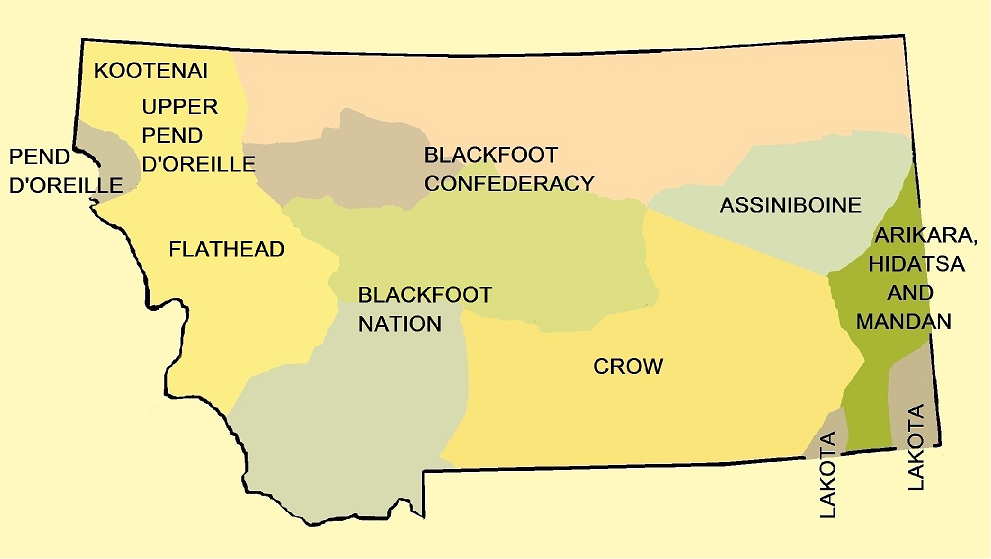

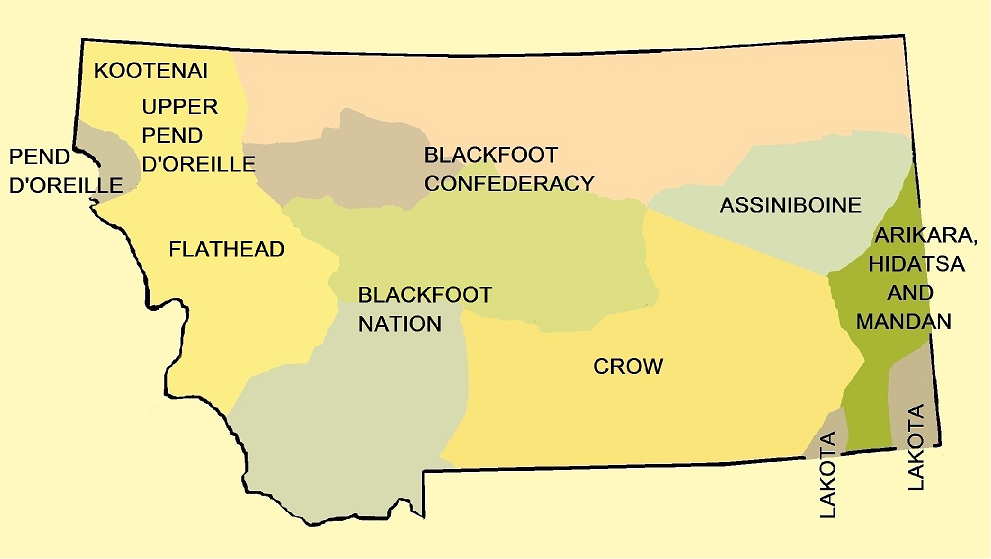

Indigenous peoples

Archeological

Archaeology or archeology is the scientific study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscape ...

evidence has shown indigenous peoples

Indigenous peoples are culturally distinct ethnic groups whose members are directly descended from the earliest known inhabitants of a particular geographic region and, to some extent, maintain the language and culture of those original people ...

lived in the area for more than 12,000 years. The oldest dated human burial site in North America was located in 1968 near Wilsall, Montana

Wilsall is a census-designated place (CDP) in Park County, Montana, Park County, Montana, United States. The population was 237 at the 2000 United States Census, 2000 census.

Description

Wilsall takes its name from Will Jordan, of the Jordan-Robe ...

at what is now known as the Anzick site (named for the discoverers). The human remains of a male infant, found at the Anzick site along with Clovis culture

The Clovis culture is a prehistoric Paleoamerican culture, named for distinct stone and bone tools found in close association with Pleistocene fauna, particularly two mammoths, at Blackwater Locality No. 1 near Clovis, New Mexico, in 1936 ...

artifacts, establish the earliest known human habitation in what is now Montana. In 2014 a group of scientists released the results of a major project in which they successfully reconstructed the genome of the Anzick boy, providing the first genetic evidence that the Clovis people were descended from Asians. Most indigenous people of the region were nomadic, following the buffalo herds and other game and living by seasonal cycles. Several major tribal groups made their home in and around the land that later became Montana.

The Crow

A crow is a bird of the genus ''Corvus'', or more broadly a synonym for all of ''Corvus''. Crows are generally black in colour. The word "crow" is used as part of the common name of many species. The related term "raven" is not pinned scientifical ...

, a Siouan

Siouan or Siouan–Catawban is a language family of North America that is located primarily in the Great Plains, Ohio and Mississippi valleys and southeastern North America with a few other languages in the east.

Name

Authors who call the entire ...

-language people, also known as the ''Apsáalooke'', were the first of the native nations currently living in Montana to arrive in the region. Around 1700 AD they moved from Alberta

Alberta ( ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is part of Western Canada and is one of the three prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to the west, Saskatchewan to the east, the Northwest Ter ...

to south-central Montana and northern Wyoming. In the 19th century, Crow warriors were allies and scouts for the United States Army The modern Crow Indian Reservation

The Crow Indian Reservation is the homeland of the Crow Tribe. Established 1868, the reservation is located in parts of Big Horn County, Montana, Big Horn, Yellowstone County, Montana, Yellowstone, and Treasure County, Montana, Treasure counties ...

is Montana's largest reservation, located in southeastern Montana along the Big Horn River, in the vicinity of Hardin, Montana

Hardin is a city in and the county seat of Big Horn County, Montana, United States. The population was 3,818 at the 2020 census.

It is located just north of the Crow Indian Reservation.

History

The city was named for Samuel Hardin, a friend o ...

.

The Cheyenne

The Cheyenne ( ) are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enroll ...

have a reservation in the southeastern portion of the state, east and adjacent to the Crow. The Cheyenne language is part of the larger Algonquian language group, but it is one of the few Plains Algonquian languages to have developed tonal characteristics. The closest linguistic relatives of the Cheyenne language are Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

and Ojibwa

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

. Little is known about the Cheyenne people before the 16th century when they were first recorded in European explorers' and traders' accounts.

The Blackfeet

The Blackfeet Nation ( bla, Aamsskáápipikani, script=Latn, ), officially named the Blackfeet Tribe of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation of Montana, is a federally recognized tribe of Siksikaitsitapi people with an Indian reservation in Monta ...

reservation today is located in northern Montana adjacent to Glacier National Park. Prior to the reservation era, the Blackfoot were fiercely independent and highly successful warriors whose territory stretched from the North Saskatchewan River

The North Saskatchewan River is a glacier-fed river that flows from the Canadian Rockies continental divide east to central Saskatchewan, where it joins with the South Saskatchewan River to make up the Saskatchewan River. Its water flows eventual ...

along what is now Edmonton

Edmonton ( ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Alberta. Edmonton is situated on the North Saskatchewan River and is the centre of the Edmonton Metropolitan Region, which is surrounded by Alberta's central region. The city ancho ...

, Alberta in Canada, to the Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains an ...

of Montana, and from the Rocky Mountains east to the Saskatchewan River

The Saskatchewan River (Cree: ''kisiskāciwani-sīpiy'', "swift flowing river") is a major river in Canada. It stretches about from where it is formed by the joining together of the North Saskatchewan and South Saskatchewan Rivers to Lake Winn ...

. Their nation consisted of three main branches, the Piegan, the Blood, and the Siksika. In the summer, they lived a nomadic, hunting lifestyle, and in the winter, the Blackfeet people lived in various winter camps dispersed perhaps a day's march apart along a wooded river valley. They did not move camp in winter unless food for the people and horses or firewood became depleted.

The Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakoda ...

also known by the Ojibwe

The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains.

According to the U.S. census, in the United States Ojibwe people are one of ...

exonym

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, ...

''Asiniibwaan'' ("Stone Sioux"), today live on the Fort Peck Indian Reservation

The Fort Peck Indian Reservation ( asb, húdam wįcášta, dak, Waxchį́ca oyáte) is located near Fort Peck, Montana, in the northeast part of the state. It is the home of several federally recognized bands of Assiniboine

The Assinibo ...

in Northeastern Montana shared with a branch of the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

nation. Intermarriage has led to some of the people now identifying as "Assiniboine Sioux". Prior to the reservation era, they inhabited the Northern Great Plains

The Great Plains (french: Grandes Plaines), sometimes simply "the Plains", is a broad expanse of flatland in North America. It is located west of the Mississippi River and east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, an ...

area of North America, specifically present-day Montana and parts of Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan ( ; ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Western Canada, western Canada, bordered on the west by Alberta, on the north by the Northwest Territories, on the east by Manitoba, to the northeast by Nunavut, and on t ...

, Alberta and southwestern Manitoba

Manitoba ( ) is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada at the Centre of Canada, longitudinal centre of the country. It is Canada's Population of Canada by province and territory, fifth-most populous province, with a population o ...

around the US/Canada border. They were well known throughout much of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Images of Assiniboine people were painted by such 19th-century artists as Karl Bodmer

Johann Carl Bodmer (11 February 1809 – 30 October 1893) was a Swiss-French printmaker, etcher, lithographer, zinc engraver, draughtsman, painter, illustrator and hunter. Known as Karl Bodmer in literature and paintings, as a Swiss and French c ...

and George Catlin

George Catlin (July 26, 1796 – December 23, 1872) was an American adventurer, lawyer, painter, author, and traveler, who specialized in portraits of Native Americans in the United States, Native Americans in the Old West.

Traveling to the We ...

. The Assiniboine have many similarities to the Lakota Sioux in lifestyle, language, and cultural habits. They are considered a band

Band or BAND may refer to:

Places

*Bánd, a village in Hungary

*Band, Iran, a village in Urmia County, West Azerbaijan Province, Iran

* Band, Mureș, a commune in Romania

*Band-e Majid Khan, a village in Bukan County, West Azerbaijan Province, I ...

of the Nakoda, or middle division of the Sioux nation. Pooling their research, historians

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human race; as well as the stu ...

, linguists

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

and anthropologists

An anthropologist is a person engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropology is the study of aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms and v ...

have concluded the Assiniboine broke away from the Lakota and Dakota Sioux bands in the 17th century.

The

The Gros Ventre

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning "big belly"), also known as the Aaniiih, A'aninin, Haaninin, Atsina, and White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in north central Montana. Today the Gros Ventre people are ...

are located today in north-central Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

and govern the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation

The Fort Belknap Indian Reservation ( ats, ’ak3ɔ́ɔyɔ́ɔ, lit=the fence or ats, ’ɔ’ɔ́ɔ́ɔ́nííítaan’ɔ, lit=Gros Ventre tribe, label=none) is shared by two Native American tribes, the A'aninin (Gros Ventre) and the Nakoda ...

. ''Gros Ventre'' is the exonym given by the French, who misinterpreted the name given to them by neighboring tribes as "the people who have enough to eat", referring to their relative wealth, as "big bellies". The people call themselves (autonym) ''A'ani'' or ''A'aninin'' (white clay people), perhaps related to natural physical formations. They were called the ''Atsina'' by the Assiniboine. The Ajani has 3,682 members and they share Fort Belknap Indian Reservation with the Assiniboine, though the two were traditional enemies. The Ajani is classified as a band of Arapaho; they speak a variant of Arapaho called ''Gros Ventre'' or ''Atsina''.

The Kootenai

The Kutenai ( ), also known as the Ktunaxa ( ; ), Ksanka ( ), Kootenay (in Canada) and Kootenai (in the United States), are an indigenous people of Canada and the United States. Kutenai bands live in southeastern British Columbia, northern ...

people live west of the Continental Divide. The Kootenai name is also spelled ''Kutenai'' or ''Ktunaxa'' . They are one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana, and they form the Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

. There are also Kootenai populations in Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

and Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

. The Salish

Salish () may refer to:

* Salish peoples, a group of First Nations/Native Americans

** Coast Salish peoples, several First Nations/Native American groups in the coastal regions of the Pacific Northwest

** Interior Salish peoples, several First Nat ...

and Pend Oreilles people also live on the Flathead Indian Reservation

The Flathead Indian Reservation, located in western Montana on the Flathead River, is home to the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles tribes – also known as the

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation. The ...

. The smaller Pend d'Oreille and Kalispell tribes originally lived around Flathead Lake

Flathead Lake ( fla, člq̓etkʷ, label=Salish, kut, yawuʔnik̓ ʔa·kuq̓nuk) is a large natural lake in northwest Montana.

The lake is a remnant of the ancient, massive glacial dammed lake, Lake Missoula of the era of the last interglacial. ...

and the western mountains, respectively.

The territories of the different tribes were defined by multiple and varied treaties with the United States, generally shrinking their land boundaries with each revision.

The Ojibwe and Cree

The Cree ( cr, néhinaw, script=Latn, , etc.; french: link=no, Cri) are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people. They live primarily in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada ...

people today jointly share the Rocky Boy's Reservation

Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation (also known as Rocky Boy Reservation) is one of seven Native American reservations in the U.S. state of Montana. Established by an act of Congress on September 7, 1916, it was named after ''Ahsiniiwin'' ( Stone Ch ...

in north-central Montana. Rocky Boy's reservation was created after most of the others as a home for some of the "landless" tribes who did not obtain reservation lands elsewhere. The creation of the reservation was largely due to the efforts of the Chippewa leader Stone Child (aka "Rocky Boy"). The Little Shell Chippewa

Little Shell Tribe of Chippewa Indians of Montana is a federally-recognized tribe of Ojibwe people in Montana.

Due to conflicts with federal authorities in the 19th century, the Little Shell Chippewa Tribe went without an Indian reservation for ...

also have a presence in Montana, however they do not have a reservation.

Other native people had a significant presence in Montana, though today do not have a reservation within the state. These nations included the Lakota, the Arapaho, and the Shoshone

The Shoshone or Shoshoni ( or ) are a Native American tribe with four large cultural/linguistic divisions:

* Eastern Shoshone: Wyoming

* Northern Shoshone: southern Idaho

* Western Shoshone: Nevada, northern Utah

* Goshute: western Utah, easter ...

. The Kiowa

Kiowa () people are a Native American tribe and an indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries,Pritzker 326 and eve ...

and the Kiowa-Apache

The Plains Apache are a small Southern Athabaskan group who live on the Southern Plains of North America, in close association with the linguistically unrelated Kiowa Tribe. Today, they are centered in Southwestern Oklahoma and Northern Texas and ...

claim an early history in the late 17th century) as nomadic hunters between the Yellowstone and Missouri.

Louisiana Purchase

On April 30, 1803, the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed by representatives of the U.S. at Paris, France. The

On April 30, 1803, the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed by representatives of the U.S. at Paris, France. The United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

ratified the treaty on October 20 and President Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

announced the treaty to the American people on July 4, 1803. The area covered by the purchase included much of the present-day United States between the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

and the Mississippi River, encompassing the Great Plains including part of what is now Montana, particularly the Missouri River drainage. The rights to the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

territory cost the U.S. $15 million, which came out to an average of 3 cents an acre. On March 10, 1804, a formal ceremony was conducted in St. Louis, Missouri

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi River, Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the Greater St. Louis, ...

, to transfer ownership of the territory from France to the United States of America. The lands of present-day Montana were practically unknown and too distant from the seats of power for this political boundary change to have much impact upon them, but the Louisiana Purchase would prove a sea-change for the area.

Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Louisiana Purchase sparked interest in knowing the character of the lands the nation had purchased, including their flora and fauna and the peoples who inhabited them. PresidentThomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, an advocate of exploration and scientific inquiry, had the Congress appropriate $2,500 for an expedition up the Missouri River and down the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

to the Pacific Ocean. He had envisioned an expedition of this nature since at least the early 1790s, due to his driving interest to secure a route for the U.S. to trade interests on the Pacific coast. Jefferson tapped his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

, to lead the expedition, and Lewis recruited William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

, an experienced soldier and frontiersman who became an equal co-leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

. They were to study, map and record information on the native people, natural history, geology, terrain, and river systems. The expedition floated up the Missouri River, making winter camp near the Mandan

The Mandan are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still res ...

villages, east of the present border of Montana and North Dakota. The following spring, the Corps of Discovery ascended to the headwaters of the Missouri River, obtained horses from the Shoshone people to cross the Continental Divide, eventually floating down the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

to the Pacific Ocean.

On the return trip heading east through present-day Montana, in July 1806, after again crossing the Continental Divide, the Corps split into two groups so Lewis could explore and map the Marias River

The Marias River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 210 mi (338 km) long, in the U.S. state of Montana. It is formed in Glacier County, in northwestern Montana, by the confluence of the Cut Bank Creek and the Two Medi ...

and Clark could do the same on the Yellowstone River

The Yellowstone River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately long, in the Western United States. Considered the principal tributary of upper Missouri, via its own tributaries it drains an area with headwaters across the mountains an ...

. While proceeding down the Yellowstone, Clark signed his name northeast of modern-day Billings

Billings is the largest city in the U.S. state of Montana, with a population of 117,116 as of the 2020 census. Located in the south-central portion of the state, it is the seat of Yellowstone County and the principal city of the Billings Metrop ...

. The inscription consists of his signature and the date July 25, 1806. Clark named the pillar after Jean Baptiste Charbonneau

Jean Baptiste Charbonneau (February 11, 1805 – May 16, 1866) was a Native American-French Canadian explorer, guide, fur trapper, trader, military scout during the Mexican–American War, ''alcalde'' (mayor) of Mission San Luis Rey de Franc ...

, nicknamed "Pompy", the son of Sacagawea

Sacagawea ( or ; also spelled Sakakawea or Sacajawea; May – December 20, 1812 or April 9, 1884)Sacagawea

...

, a Shoshone woman who had helped to guide the expedition and, along with her husband ...

Toussaint Charbonneau

Toussaint Charbonneau (March 20, 1767 – August 12, 1843) was a French-Canadian explorer, trader and a member of the Lewis and Clark Expedition. He is also known as the husband of Sacagawea.

Early years

Charbonneau was born in Boucherv ...

, had acted as an interpreter. Clark's inscription is the only remaining physical evidence found along the route that was followed by the expedition. In the meantime, Lewis' group descending the Marias met a small party of Piegan Blackfeet

The Piegan ( Blackfoot: ''Piikáni'') are an Algonquian-speaking people from the North American Great Plains. They were the largest of three Blackfoot-speaking groups that made up the Blackfoot Confederacy; the Siksika and Kainai were the oth ...

. Their initial meeting was cordial, but during the night, the Blackfeet tried to steal their weapons. In the ensuing struggle, two men were killed, the only native deaths attributable to the expedition. To prevent further bloodshed, the group of four—Lewis, Drouillard, and the two Field brothers—fled over in a day before they camped again. Lewis's and Clark's separate parties rejoined one another at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers on August 12, 1806. Thus reunited, and heading downstream, they were able to quickly return to St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

. During the trip, the expedition spent more of its time in what today is Montana than any other place.

First settlements

St. Mary's Mission was the first permanent European settlement in Montana. Through interactions withIroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

between 1812 and 1820, the Salish

Salish () may refer to:

* Salish peoples, a group of First Nations/Native Americans

** Coast Salish peoples, several First Nations/Native American groups in the coastal regions of the Pacific Northwest

** Interior Salish peoples, several First Nat ...

people learned about Christianity and the Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

(known as "blackrobes"), who worked with Native tribes teaching about agriculture, medicine, and religion. Interest in these "blackrobes" grew among the Salish. In 1831, four young Salish men were dispatched to St. Louis, Missouri to request a "blackrobe" to return with them to their homeland in the Bitterroot Valley. The four Salish men were directed to the home and office of William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

(of Lewis and Clark fame) to make their request. At that time Clark was in charge of administering the territory they called home. Through the perils of their trip, two died at the home of General Clark. The remaining two secured a visit with St. Louis Bishop Joseph Rosati

Joseph Rosati (30 January 1789 – 25 September 1843) was an Italian-born Catholic missionary to the United States who served as the first bishop of the Diocese of Saint Louis between 1826 and 1843. A member of the Congregation of the Mission, ...

, who assured them that missionaries would be sent to the Bitterroot Valley

The Bitterroot Valley is located in southwestern Montana, along the Bitterroot River between the Bitterroot Range and Sapphire Mountains, in the Northwestern United States.

Geography

The valley extends approximately from Lost Trail Pass in Id ...

when funds and missionaries were available in the future.

Again in 1835 and 1837 the Salish people dispatched men to St. Louis to request missionaries but to no avail. Finally in 1839 a group of Iroquois and Salish met Father Pierre-Jean DeSmet

Pierre-Jean De Smet, SJ ( ; 30 January 1801 – 23 May 1873), also known as Pieter-Jan De Smet, was a Flemish Catholic priest and member of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). He is known primarily for his widespread missionary work in the mid-19th ...

in Council Bluffs, Iowa

Council Bluffs is a city in and the county seat of Pottawattamie County, Iowa, Pottawattamie County, Iowa, United States. The city is the most populous in Southwest Iowa, and is the third largest and a primary city of the Omaha–Council Bluffs ...

. The meeting resulted in Father DeSmet promising to fulfill their request for a missionary the following year. DeSmet arrived in present-day Stevensville on September 24, 1841, and called the settlement St. Mary's Mission. Construction of a chapel immediately began, followed by other permanent structures including log cabins and Montana's first pharmacy.

In 185Major John Owen

arrived in the valley and set up camp north of St. Mary's. In time, Major Owen established a trading post and military strong point named Fort Owen, which served the Native people, settlers, and missionaries in the valley.

Military history

Fort Benton

The first permanent settlement in Montana was Fort Benton, established as afur trading

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the most ...

post in 1847. It was named in honor of Senator Thomas Hart Benton, who encouraged settlement of the West. The U.S. Army took over the commercial fort in 1869 and a detachment of the 7th Infantry remained in the town until 1881. Its location on the Missouri River marked the farthest practical point upriver that steamboats could navigate. With the arrival of the first steamboats in 1860, the town of Fort Benton began to develop outside the fort's walls and developed into a major trading center over the next 27 years, until it was supplanted with the arrival of railroads in the Montana Territory. An original blockhouse still remaining in the largely reconstructed fort is the oldest building in Montana still on its original foundations, giving rise to the town's reputation as "the birthplace of Montana".

Fort Ellis

Built near the head of theGallatin Valley

Gallatin County is located in the U.S. state of Montana. With its county seat in Bozeman, Montana, Bozeman, it is the List of counties in Montana, second-most populous county in Montana, with a population of 118,960 in the 2020 United States cen ...

, Fort Ellis

Fort Ellis was a United States Army fort established August 27, 1867, east of present-day Bozeman, Montana. Troops from the fort participated in many major campaigns of the Indian Wars. The fort was closed on August 2, 1886.

History

The fort w ...

played an important role in many of the early Indian conflicts in the territory. Elements of the 2nd Cavalry stationed here took part in both the Marias Massacre

The Marias Massacre (also known as the Baker Massacre or the Piegan Massacre) was a massacre of Piegan Blackfeet Native peoples which was committed by the United States Army as part of the Indian Wars. The massacre took place on January 23, 1870 ...

and the Great Sioux War of 1876-77

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of the war was the ...

. It also provided a staging location for many missions of exploration and survey into the region that became Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

.

Fort Shaw

Fort Shaw

Fort Shaw (originally named Camp Reynolds) was a United States Army fort located on the Sun River 24 miles west of Great Falls, Montana, in the United States. It was founded on June 30, 1867, and abandoned by the Army in July 1891. It later serv ...

was established in the spring of 1867 located west of Great Falls

Great may refer to: Descriptions or measurements

* Great, a relative measurement in physical space, see Size

* Greatness, being divine, majestic, superior, majestic, or transcendent

People

* List of people known as "the Great"

*Artel Great (born ...

in the Sun River Valley. Two posts built at the time were Camp Cooke on the Judith River

The Judith River is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 124 mi (200 km) long, running through central Montana in the United States. It rises in the Little Belt Mountains and flows northeast past Utica and Hobson. It is ...

and Fort C.F. Smith on the Bozeman Trail

The Bozeman Trail was an overland route in the western United States, connecting the gold rush territory of southern Montana to the Oregon Trail in eastern Wyoming. Its most important period was from 1863–68. Despite the fact that the major pa ...

in south central Montana Territory. Fort Shaw was built of adobe and lumber by the 13th Infantry. The fort had a parade ground that was 400 feet (120 m) square, and consisted of barracks for officers, a hospital, and a trading post, and could house up to 450 soldiers. The soldiers mainly guarded the Benton-Helena Road, the major supply-line from Fort Benton, which was the head of navigation on the Missouri River, to the gold mining districts in southwestern Montana Territory. The fort was decommissioned in 1891. The following year, 1892, the 20 buildings on the site were adapted for the Fort Shaw Indian Industrial School. The school boarded young Native people to assimilate them, teach them English, and educate them in modern technology; it had as many as 17 faculty members, 11 Native assistants, and 300 students.

Montana Territory

After the discovery of gold in the region, Montana was designated as a United States territory (Montana Territory

The Territory of Montana was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from May 26, 1864, until November 8, 1889, when it was admitted as the 41st state in the Union as the state of Montana.

Original boundaries

T ...

) on May 26, 1864 and, with rapid population growth, as the 41st state on November 8, 1889.

Montana territory was organized from the existing Idaho Territory

The Territory of Idaho was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1863, until July 3, 1890, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as Idaho.

History

1860s

The territory w ...

by Act of Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

and signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

on May 28, 1864. The areas east of the continental divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

had been previously part of the Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

and Dakota

Dakota may refer to:

* Dakota people, a sub-tribe of the Sioux

** Dakota language, their language

Dakota may also refer to:

Places United States

* Dakota, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Dakota, Illinois, a town

* Dakota, Minnesota, a ...

territories and had been acquired by the United States in the Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

.

The territory also included land west of the continental divide, which had been acquired by the United States in the Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty is a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to t ...

, and originally included in the Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Ori ...

. (The part of the Oregon Territory that became part of Montana had been split off as part of the Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

.)

The boundary between the Washington Territory and Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of No ...

was the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

(as shown on the 1861 map); however, the boundary between the Idaho Territory

The Territory of Idaho was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1863, until July 3, 1890, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as Idaho.

History

1860s

The territory w ...

and the Montana Territory followed the Bitterroot Range

The Bitterroot Range is a mountain range and a subrange of the Rocky Mountains that runs along the border of Montana and Idaho in the northwestern United States. The range spans an area of and is named after the bitterroot (''Lewisia rediviva' ...

north of 46°30'N (as shown on the 1864 map). Popular legend says a drunken survey party followed the wrong mountain ridge and mistakenly moved the boundary west into the Bitterroot Range.

Contrary to legend, the boundary is precisely where the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

intended. The Organic Act of the Territory of Montana defines the boundary as extending from the modern intersection of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

, Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

, and Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

at:

the forty-fourth degree and thirty minutes of north latitude; thence due west along said forty-fourth degree and thirty minutes of north latitude to a point formed by its intersection with the crest of the Rocky Mountains; thence following the crest of the Rocky Mountains northward till its intersection with the Bitter Root Mountains; thence northward along the crest of the Bitter Root Mountains to its intersection with the thirty-ninth degree of longitude west from Washington; thence along said thirty-ninth degree of longitude northward to the boundary line of the British possessions.The boundaries of Montana territory did not change during its existence. Montana was admitted to the Union as the

state of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia ...

on November 8, 1889.

Indian Wars

Battle of the Little Big Horn

TheBattle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

—also called Custer's Last Stand and the Battle of the Greasy Grass—was an armed engagement between a Lakota

Lakota may refer to:

*Lakota people, a confederation of seven related Native American tribes

*Lakota language, the language of the Lakota peoples

Place names

In the United States:

*Lakota, Iowa

*Lakota, North Dakota, seat of Nelson County

*Lakota ...

(Sioux)-Northern Cheyenne

The Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation ( chy, Tsėhéstáno; formerly named the Tongue River) is the federally recognized Northern Cheyenne tribe. Located in southeastern Montana, the reservation is approximately ...

-Arapaho

The Arapaho (; french: Arapahos, ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho band ...

combined force and the 7th Cavalry of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

. It occurred June 25–June 26, 1876, near the Little Bighorn River in eastern Montana Territory near present-day Hardin, Montana

Hardin is a city in and the county seat of Big Horn County, Montana, United States. The population was 3,818 at the 2020 census.

It is located just north of the Crow Indian Reservation.

History

The city was named for Samuel Hardin, a friend o ...

, on land that today is part of the Crow Indian Reservation

The Crow Indian Reservation is the homeland of the Crow Tribe. Established 1868, the reservation is located in parts of Big Horn County, Montana, Big Horn, Yellowstone County, Montana, Yellowstone, and Treasure County, Montana, Treasure counties ...

. The Crow tribe sided with the U.S. army. George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the American Indian Wars.

Custer graduated from West Point in 1861 at the bottom of his class, b ...

, with 257 troops attacked a much larger force of Native Americans, who were defending their civilian encampments, and in three hours the Custer battalion was completely annihilated. Only two men from the 7th Cavalry later claimed to have seen the battle: a young Crow whose name translated as Curley

Curley is a surname, given name, nickname or stage name. It may refer to:

Surname

* August Curley (born 1960), American football player

* Arthur Curley (1938 – 1998), American librarian

* Barney Curley (1939 – 2021), Irish racehorse traine ...

, and a trooper named Peter Thompson, who had fallen behind Custer's column, and most accounts of the last moments of Custer's forces are conjecture. Lakota accounts assert that Crazy Horse

Crazy Horse ( lkt, Tȟašúŋke Witkó, italic=no, , ; 1840 – September 5, 1877) was a Lakota war leader of the Oglala band in the 19th century. He took up arms against the United States federal government to fight against encroachment by wh ...

personally led one of the large groups of Lakota who overwhelmed the cavalry. While exact numbers are difficult to determine, it is commonly estimated that the Northern Cheyenne and Lakota outnumbered the 7th Cavalry by approximately 3:1, a ratio that was extended to 5:1 during the fragmented parts of the battle.

Later, the Sioux

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin (; Dakota language, Dakota: Help:IPA, /otʃʰeːtʰi ʃakoːwĩ/) are groups of Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribes and First Nations in Canada, First Nations peoples in North America. The ...

were defeated in a series of subsequent battles by the reinforced U.S. Army who continued attacking even in the winter, and most were forced to move onto reservations, mostly outside of Montana, primarily by tactics such as preventing buffalo hunts and enforcing government food-distribution policies to "friendlies" only. The Lakota were compelled to sign a treaty in 1877 ceding the Black Hills

The Black Hills ( lkt, Ȟe Sápa; chy, Moʼȯhta-voʼhonáaeva; hid, awaxaawi shiibisha) is an isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into Wyoming, United States. Black Elk P ...

to the United States, but a low-intensity war continued, culminating, fourteen years later, in the killing of Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( lkt, Tȟatȟáŋka Íyotake ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. He was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock I ...

(December 15, 1890) at Standing Rock

The Standing Rock Reservation ( lkt, Íŋyaŋ Woslál Háŋ) lies across the border between North and South Dakota in the United States, and is inhabited by ethnic "Hunkpapa and Sihasapa bands of Lakota Oyate and the Ihunktuwona and Pabaksa ...

and the Wounded Knee Massacre (December 29, 1890) at Pine Ridge.

Northern Cheyenne exodus

Following the

Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn, known to the Lakota and other Plains Indians as the Battle of the Greasy Grass, and also commonly referred to as Custer's Last Stand, was an armed engagement between combined forces of the Lakota Sioux, Nor ...

, attempts by the U.S. Army to capture the Cheyenne intensified. A group of 972 Cheyenne was escorted to Indian Territory

The Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the Federal government of the United States, United States Government for the relocation of Native Americans in the United St ...

in Oklahoma in 1877. The government intended to re-unite the Northern and Southern Cheyenne into one nation. There the conditions were dire; the Northern Cheyenne were not used to the climate and soon many became ill with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

. In addition, the food rations were insufficient and of poor quality. In 1878, the two principal Chiefs, Little Wolf

Little Wolf (''Cheyenne'': ''Ó'kôhómôxháahketa'', sometimes transcribed ''Ohcumgache'' or ''Ohkomhakit'', more correctly translated Little Coyote, 18201904) was a Northern Só'taeo'o Chief and Sweet Medicine Chief of the Northern Cheyenne. ...

and Morning Star (Dull Knife

Morning Star (Cheyenne: ''Vóóhéhéve''; also known by his Lakota Sioux name ''Tȟamílapȟéšni'' or its translation, Dull Knife) (1810–1883) was a great chief of the Northern Cheyenne people and headchief of the ''Notameohmésêhese'' ("N ...

) pressed for the release of the Cheyenne so they could travel back north. However, they were denied permission, so that same year the two men led a group of 353 Northern Cheyenne who left Indian Territory to travel back north. The Army and other civilian volunteers were in hot pursuit of the Cheyenne as they traveled north. It is estimated that a total of 13,000 Army soldiers and volunteers were sent to pursue the Cheyenne over the whole course of their journey north.

After crossing into Nebraska, the group split into two. One group was led by Little Wolf

Little Wolf (''Cheyenne'': ''Ó'kôhómôxháahketa'', sometimes transcribed ''Ohcumgache'' or ''Ohkomhakit'', more correctly translated Little Coyote, 18201904) was a Northern Só'taeo'o Chief and Sweet Medicine Chief of the Northern Cheyenne. ...

, and the other by Dull Knife. Little Wolf and his band made it back to Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

. Dull Knife and his band were captured and escorted to Fort Robinson

Fort Robinson is a former U.S. Army fort and now a major feature of Fort Robinson State Park, a public recreation and historic preservation area located west of Crawford on U.S. Route 20 in the Pine Ridge region of northwest Nebraska.

The for ...

, Nebraska

Nebraska () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by South Dakota to the north; Iowa to the east and Missouri to the southeast, both across the Missouri River; Kansas to the south; Colorado to the southwe ...

and sequestered. They were ordered to return to Oklahoma but they refused. Conditions at the fort grew tense through the end of 1878 and soon the Cheyenne were confined to barracks with no food, water, or heat. In January 1879, Dull Knife and his group broke out of Ft. Robinson. Much of the group was gunned down as they ran away from the fort, and others were discovered near the fort during the following days and ordered to surrender but most of the escapees chose to fight because they would rather be killed than taken back into custody. It is estimated that only 50 survived the breakout, including Dull Knife. Several of the escapees later had to stand trial for the murders that had been committed in Kansas. The remains of those killed were repatriated in 1994.

Ultimately, the military gave up attempting to relocate the Northern Cheyenne in Oklahoma. The persistence of the Northern Cheyenne resulted in the creation of the Northern Cheyenne reservation in Montana.

The flight of the Nez Perce

The

The Nez Perce people

The Nez Percé (; autonym in Nez Perce language: , meaning "we, the people") are an Indigenous people of the Plateau who are presumed to have lived on the Columbia River Plateau in the Pacific Northwest region for at least 11,500 years.Ames, K ...

were settled what today is Washington and Oregon, though made hunting forays into western Montana. However, in 1877 pressure from white settlers led to several incidents of violence and a significant number of the Nez Perce were forced from their home region and fled rather than submit to being moved to a reservation. With 2000 U.S. soldiers in pursuit, 800 Nez Perce spent over three months outmaneuvering and battling their pursuers, led by General Howard. They traveled across Oregon, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, Idaho, Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

, and Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

. In the process, they held off the Army at the Battle of the Big Hole

The Battle of the Big Hole was fought in Montana Territory, August 9–10, 1877, between the United States Army and the Nez Perce tribe of Native Americans during the Nez Perce War. Both sides suffered heavy casualties. The Nez Perce withd ...

in southwestern Montana, dropped into Yellowstone Park, then traveled into east-central Montana where they attempted to ally with both the Crow and the Arapaho, but were rebuffed due to tensions surrounding the aftermath of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. They then turned north, attempting to reach Canada.

General Howard, leading the United States cavalry, was impressed with the skill with which the Nez Perce fought, using advance and rear guards, skirmish lines, and field fortifications. However, unbeknownst to the Nez Perce, a force led by Nelson A. Miles

Nelson Appleton Miles (August 8, 1839 – May 15, 1925) was an American military general who served in the American Civil War, the American Indian Wars, and the Spanish–American War.

From 1895 to 1903, Miles served as the last Commanding Gen ...

was dispatched from eastern Montana on a quick march to intercept them, which occurred less than south of Canada in the Bear Paw Mountains

The Bears Paw Mountains (Bear Paw Mountains, Bear's Paw Mountains or Bearpaw Mountains) are an insular-montane island range in the Central Montana Alkalic Province in north-central Montana, United States, located approximately 10 miles south of ...

, not far from present-day Chinook in Blaine County. Finally, after a devastating five-day battle during freezing weather conditions with no food or blankets, having lost the major war leaders, Chief Joseph formally surrendered to General Miles on October 5, 1877.

Louis Riel and the Metis

SomeMétis

The Métis ( ; Canadian ) are Indigenous peoples who inhabit Canada's three Prairie Provinces, as well as parts of British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and the Northern United States. They have a shared history and culture which derives ...

from the British territory to the north settled in Montana in the latter half of the 19th century. For a time, Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first ...

, the Métis leader from Manitoba in exile, taught school at St. Peter's Mission in Montana and was active in the local Republican Party. Democrats alleged he helped Métis men, who were not American citizens, to vote for the Republicans. In the summer of 1884, a delegation of Métis leaders including Gabriel Dumont and James Isbister

James Isbister (November 29, 1833 – October 16, 1915) was a Canadian Métis leader of the 19th century. Prominent among the Anglo-Métis of the area, he is considered to be the founder of the city of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

Life

An i ...

, convinced Riel to return north, where in the following year he led the Métis revolt against Canadian rule, known as the North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion (french: Rébellion du Nord-Ouest), also known as the North-West Resistance, was a resistance by the Métis people under Louis Riel and an associated uprising by First Nations Cree and Assiniboine of the District of S ...

. Following the defeat of the Métis rebels and the imprisonment and later hanging to Riel, Gabriel Dumont fled to exile in Montana.

Railroads

The railroads were the engine of settlement in the state. Major development occurred in the 1880s. TheNorthern Pacific Railroad

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by 38th United States Congress, Congress in 1864 and given ...

was given land grants by the federal government so that it could borrow money to build its system, reaching Billings

Billings is the largest city in the U.S. state of Montana, with a population of 117,116 as of the 2020 census. Located in the south-central portion of the state, it is the seat of Yellowstone County and the principal city of the Billings Metrop ...

in 1882. The federal government kept every other section of land, and gave it away to homesteaders. At first the railroad sold much of its holdings at low prices to land speculators in order to realize quick cash profits, and also to eliminate sizable annual tax bills. The speculators in turn parceled out the land on credit to farmers and ranchers eager to develop operations near a railroad. By 1905 the company changed its land policies as it realized it had been a costly mistake to have sold so much land at wholesale prices. With better railroad service and improved methods of farming the Northern Pacific easily sold what had been heretofore "worthless" land directly to farmers at good prices. By 1910 the railroad's holdings in North Dakota had been greatly reduced. Meanwhile, the Great Northern Railroad energetically promoted settlement along its lines in the northern part of the state. The Great Northern bought its lands from the federal government—it received no land grants—and resold them to farmers one by one. It operated agencies in Germany and Scandinavia that promoted its lands, and brought families over at low cost.

The village of Taft, located in western Montana near the Idaho border, was representative of numerous short lived railroad construction camps. In 1907-09 Taft served as a boisterous construction town for the Chicago, Milwaukee, & St. Paul Railroad. The camp included many ethnic groups, numerous saloons and prostitutes, and substantial violence. When construction was finished, the camp was abandoned.

In 1882 the Northern Pacific platted Livingston, Montana

Livingston is a city and county seat of Park County, Montana, United States. It is in southwestern Montana, on the Yellowstone River, north of Yellowstone National Park. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 8,040.

History

T ...

, a major division point, repair and maintenance center, and gateway to Yellowstone National Park

Yellowstone National Park is an American national park located in the western United States, largely in the northwest corner of Wyoming and extending into Montana and Idaho. It was established by the 42nd U.S. Congress with the Yellowston ...

. Built in symmetrical fashion along both sides of the track, the city grew to 7,000 by 1914. Several structures built between 1883 and 1914 still exist and provide a physical record of the era and indicate the city's role as a rail and tourist center. The Northern Pacific depot reflects the desire to impress the tourists who disembarked here for Yellowstone Park, and the railroad's machine shops reveal the city's industrial history.

Women

In Montana, very few single men attempted to operate a farm or ranch; farmers clearly understood the benefits of marriage and family. A wife and numerous children could help the head of the household handle many chores, including child-rearing, feeding the family, manufacturing clothing, managing housework, feeding the hired hands, and, especially after the 1930s, handling the paperwork and financial details. Efforts to write

Efforts to write woman suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Beginning in the start of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to gran ...

into Montana's 1889 constitution failed. Montana women, especially "society women", did not strongly support the suffragists. However, help from national leaders and the efforts of Montana supporters of suffrage such as Jeannette Rankin

Jeannette Pickering Rankin (June 11, 1880 – May 18, 1973) was an American politician and women's rights advocate who became the first woman to hold federal office in the United States in 1917. She was elected to the U.S. House of Representat ...

(1880–1973), led to success in 1914 when voters ratified a suffrage amendment passed by the legislature in 1913. In 1916, Rankin, a Republican, became the first woman ever elected to Congress. She was elected again in 1940. Rankin was a peace activist, who voted against American entry into both World War I and World War II.

The status of women in the 19th-century West has drawn the attention of numerous scholars, whose interpretations fall into three types: 1) the Frontier school influenced by Frederick Jackson Turner

Frederick Jackson Turner (November 14, 1861 – March 14, 1932) was an American historian during the early 20th century, based at the University of Wisconsin until 1910, and then Harvard University. He was known primarily for his frontier thes ...

, which argues that the West was a liberating experience for women and men; 2) the reactionists, who view the West as a place of drudgery for women, who reacted unfavorably to the isolation and difficult work environment in the West; and 3) those writers who claim the West had no distinctive effect on women's lives, that it was a static, neutral frontier. Cole (1990) uses legal records to argue that the Turner thesis best explains the improvement in women's status in Montana and the early achievement of suffrage.

Women's clubs expressed the interests, needs, and beliefs of middle-class women around the start of the 20th century. While accepting the domestic role established by the cult of domesticity

The Culture of Domesticity (often shortened to Cult of Domesticity) or Cult of True Womanhood is a term used by historians to describe what they consider to have been a prevailing value system among the upper and middle classes during the 19th cen ...

, their reformist activities reveal a persistent demand for self-expression outside the home. Homesteading was a significant experience for altering women's perceptions of their roles. They expressed their aesthetic interests in gardens and organized social activities. Though these clubs allowed women to fulfill their traditional roles they also encouraged women to pursue social, intellectual, and community interests. Women took an active role in the Progressive Movement

Progressivism holds that it is possible to improve human societies through political action. As a political movement, progressivism seeks to advance the human condition through social reform based on purported advancements in science, techno ...

, especially in battles for suffrage, prohibition, and better schools. Women were also prominent in church activities, charity work, and crime reduction.

Childbirth was serious and sometimes life-threatening for rural women well into the 20th century. Although large families were favored by farm families, most women employed birth control methods to space their children and limit their family size. Pregnant women had little access to modern knowledge about prenatal care. Delivery was the big gamble; the great majority gave birth at home, with the services of a midwife or an experienced neighbor. Despite the increased availability of hospital care after the 1920s, modern medical benefits to mitigate the danger of childbirth were not available to most rural Montana women until the World War II era.

Agricultural history

Cattle ranching

Cattle ranching has long been central to Montana's history and economy. Cattle ranching came early to Montana with the entrepreneurship of Johnny Grant in the Deer Lodge Valley in the late 1850s, who traded fat cattle to settlers in exchange for two trail-worn (but otherwise healthy) animals. He later sold his ranch to Conrad Kohrs, who developed a major cattle empire in the area. Today, Grant's core homestead is the Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site on the edge of

Cattle ranching has long been central to Montana's history and economy. Cattle ranching came early to Montana with the entrepreneurship of Johnny Grant in the Deer Lodge Valley in the late 1850s, who traded fat cattle to settlers in exchange for two trail-worn (but otherwise healthy) animals. He later sold his ranch to Conrad Kohrs, who developed a major cattle empire in the area. Today, Grant's core homestead is the Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site on the edge of Deer Lodge

Deer Lodge is a city in and the county seat of Powell County, Montana, United States. The population was 2,938 at the 2020 census.

Description

The city is perhaps best known as the home of the Montana State Prison, a major local employer. ...

, and is maintained as a living demonstration of the ranching style of the late 19th century. It is operated by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an agency of the United States federal government within the U.S. Department of the Interior that manages all national parks, most national monuments, and other natural, historical, and recreational propertie ...

.

In 1866 Nelson Story brought the first herd of Texas longhorn

The Texas Longhorn is an American list of cattle breeds, breed of beef cattle, characterized by its long horns, which can span more than from tip to tip. It derives from cattle brought from the Iberian Peninsula to the Americas by Spanish con ...

s up from Texas. Additional herds came into Montana east of the divide and initially expanded greatly on the open range

In the Western United States and Canada, open range is rangeland where cattle roam freely regardless of land ownership. Where there are "open range" laws, those wanting to keep animals off their property must erect a fence to keep animals out; th ...

. Montana stockmen and farmers survived the slump in mining during the early 1870s and were ready by mid-decade to expand eastward onto the plains, as a recovery in mining led to improved markets. However, cattle ranching expanded beyond the carrying capacity of the land, and a drought year combined with the harsh winter of 1886-1887 decimated Montana's cattle industry. The ranchers who survived began to fence in their ranches and the era of the open range

In the Western United States and Canada, open range is rangeland where cattle roam freely regardless of land ownership. Where there are "open range" laws, those wanting to keep animals off their property must erect a fence to keep animals out; th ...

came to an end.

The memories of cattle ranching form an important part of Montana's modern identity.

Farming

By 1908, theopen range

In the Western United States and Canada, open range is rangeland where cattle roam freely regardless of land ownership. Where there are "open range" laws, those wanting to keep animals off their property must erect a fence to keep animals out; th ...

that had sustained Native American tribes and government-subsidized cattle barons was pockmarked with small ranchers and struggling farmers. The revised Homestead Act

The Homestead Acts were several laws in the United States by which an applicant could acquire ownership of government land or the public domain, typically called a homestead. In all, more than of public land, or nearly 10 percent of th ...

of the early 1900s greatly affected the settlement of Montana. This act expanded the land that was provided by the Homestead Act of 1862 from 160acres to 320 (). When the latter act was signed by President William Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pre ...