History Of Limerick (city) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of Limerick stretches back to its establishment by

The history of Limerick stretches back to its establishment by

The earliest record of

The earliest record of

The arrival of the

The arrival of the

Limerick was besieged several times in the 17th century. The first was in 1642, when the Irish Confederates took the King John's Castle from its English garrison. The city was besieged by

Limerick was besieged several times in the 17th century. The first was in 1642, when the Irish Confederates took the King John's Castle from its English garrison. The city was besieged by

While in 1695 the repressive penal laws were introduced that banned Catholics from public office, buying freehold land, voting or practising their religion in public, Limerick's position as the main port on the western side of Ireland meant that the city, and the Protestant upper class and the Catholic merchant class, began to prosper. The British version of

While in 1695 the repressive penal laws were introduced that banned Catholics from public office, buying freehold land, voting or practising their religion in public, Limerick's position as the main port on the western side of Ireland meant that the city, and the Protestant upper class and the Catholic merchant class, began to prosper. The British version of

The

The

On 5 December 1921

On 5 December 1921

Limerick's farm-based economy was reduced to a state of barter. This was the period during which Ireland's interventionist, control economic style was developed. The Laissez-faireism of the 1920s was abandoned in the face of skyrocketing unemployment, poverty and emigration. The state set up non-agricultural industries such as Turf Development Board (Later

Limerick's farm-based economy was reduced to a state of barter. This was the period during which Ireland's interventionist, control economic style was developed. The Laissez-faireism of the 1920s was abandoned in the face of skyrocketing unemployment, poverty and emigration. The state set up non-agricultural industries such as Turf Development Board (Later

The seemingly sudden economic growth of the 1990s, termed the ''

The seemingly sudden economic growth of the 1990s, termed the ''

The History of Limerick

'', Limerick: A Watson & Co., 1787. * Fisk, Robert, ''In Time of War'', Paladin: London, 1985. * Gray, Tony, ''The Lost Years, The Emergency in Ireland 1939–45'', London: Little Brown, 1997. * Kemmy Jim,

An Introduction of Limerick History

' The Old Limerick Journal, Vol. 22, Christmas 1987. * Keogh Dermot,

Jews in Twentieth-Century Ireland

'', Cork;

Local Studies at Limerick City LibraryJohn Begley, ''The Diocese of Limerick, Ancient and Medieval'' (1906)Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland (1849)

– contains the essay ''The Northmen of Limerick'' by Timothy Lee

The Limerick Soviet, 1919 Online edition of Liam Cahill's excellent bookYahoo Holiday's Guide – Limerick HistoryLocal History and Folklore of Limerick cityImages of Limerick from Flickr

{{DEFAULTSORT:History of Limerick

The history of Limerick stretches back to its establishment by

The history of Limerick stretches back to its establishment by Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

as a walled city on King's Island (an island in the River Shannon) in 812, and to the granting of Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

's city charter

A city charter or town charter (generically, municipal charter) is a legal document ('' charter'') establishing a municipality such as a city or town. The concept developed in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Traditionally the granting of a charte ...

in 1197.

King John ordered the building (1200) of a great castle. The city was besieged

Besieged may refer to:

* the state of being under siege

* ''Besieged'' (film), a 1998 film by Bernardo Bertolucci

{{disambiguation ...

three times in the 17th century, culminating in the famous 1691 Treaty of Limerick

}), signed on 3 October 1691, ended the 1689 to 1691 Williamite War in Ireland, a conflict related to the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War. It consisted of two separate agreements, one with military terms of surrender, signed by commanders of a French ...

and the flight

Flight or flying is the process by which an object moves through a space without contacting any planetary surface, either within an atmosphere (i.e. air flight or aviation) or through the vacuum of outer space (i.e. spaceflight). This can be a ...

of the defeated Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

leaders abroad

''Abroad'' ( ar, الغربة) is a short film directed by Lebanese filmmaker Zayn Alexander. The film made its world premiere at the 33rd Santa Barbara International Film Festival on February 2, 2018. The Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebane ...

. Much of the city was built during the following Georgian prosperity, which ended abruptly with the Act of Union in 1800. Today the city has a growing multicultural population.

Name

''Luimneach'' originally referred to the general area along the banks of the Shannon Estuary, which was known as ''Loch Luimnigh''. The original pre-Viking and Viking era settlement on Kings Island was known in the annals as ''Inis Sibhtonn'' and ''Inis an Ghaill Duibh''. The name dates from at least 561, but its original meaning is unclear. Early anglicised spellings of the name are ''Limnigh, Limnagh, Lumnigh'' and ''Lumnagh'', which are closer to the Irish spelling. There are numerous places of the same name throughout Ireland (anglicised as Luimnagh, Lumnagh, Limnagh etc.). According to P W Joyce in ''The Origin and History of Irish Names of Places II'', the name "signifies a bare or barren spot of land". Similarly, others have suggested that the name derives from ''loimeanach'' meaning "a bare marsh" or "a spot made bare by feeding horses". The ''Dindsenchas

''Dindsenchas'' or ''Dindshenchas'' (modern spellings: ''Dinnseanchas'' or ''Dinnsheanchas'' or ''Dınnṡeanċas''), meaning "lore of places" (the modern Irish word ''dinnseanchas'' means "topography"), is a class of onomastic text in early Ir ...

(The Metrical Dindsenchas III page 274)'', attempted to explain the name in a number of ways, connecting it particularly with ''luimnigthe'' ("cloaked") and ''luimnechda'' ("shielded").

Early history

Limerick's early history is virtually undocumented, other than by the oral tradition, because the Vikings were diligent in destroying Irish public records.William Camden

William Camden (2 May 1551 – 9 November 1623) was an English antiquarian, historian, topographer, and herald, best known as author of ''Britannia'', the first chorographical survey of the islands of Great Britain and Ireland, and the ''Ann ...

wrote that the Irish had been jealous about their antiquity since the deluge and were ambitious to memorialise important events for posterity.Ferrar (1787), pp. 1–3 The earliest provable settlement dates from 812;Ferrar (1787), p. 4 however, history suggests the presence of earlier settlements in the area surrounding King's Island, the island at the historical city centre. Antiquity's map-maker, Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

, produced in 150 AD the earliest map of Ireland, showing a place called "Regia" at the same site as King's Island. History also records an important battle involving Cormac mac Airt

Cormac mac Airt, also known as Cormac ua Cuinn (grandson of Conn) or Cormac Ulfada (long beard), was, according to medieval Irish legend and historical tradition, a High King of Ireland. He is probably the most famous of the ancient High Kings ...

in 221 and a visit by St. Patrick in 434 to baptise an Eóganachta

The Eóganachta or Eoghanachta () were an Irish dynasty centred on Cashel which dominated southern Ireland (namely the Kingdom of Munster) from the 6/7th to the 10th centuries, and following that, in a restricted form, the Kingdom of Desmond, an ...

king, Carthann the Fair. Saint Munchin, the first bishop of Limerick died in 652, indicating the city was a place of some note. In 812 Danes sailed up the Shannon and pillaged the town, burned the monastery of Mungret but were forced to flee when the Irish attacked and killed many of their number.

Viking origins

The earliest record of

The earliest record of Vikings

Vikings ; non, víkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and ...

at Limerick is in 845, reported by the '' Annals of Ulster'', and there are intermittent reports of Vikings in the region later in the 9th century. Permanent settlement on the site of modern Limerick had begun by 922. In that year a Viking jarl or prince called Tomrair mac Ailchi

Tomrair mac Ailchi, or Thormod/Thorir Helgason, was the Viking jarl and prince who reestablished the preexisting small Norse base or settlement at Limerick as a powerful kingdom in 922 overnight when he is recorded arriving there with a huge fl ...

—Thórir Helgason—led the Limerick fleet on raids along the River Shannon, from the lake of Lough Derg to the lake of Lough Ree

Lough Ree () is a lake in the midlands of Ireland, the second of the three major lakes on the River Shannon. Lough Ree is the second largest lake on the Shannon after Lough Derg. The other two major lakes are Lough Allen to the north, and Lou ...

, pillaging ecclesiastical settlements. Two years later, the Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of the Wicklow Mountains range. At the 2016 c ...

Vikings led by Gofraid ua Ímair attacked Limerick, but were driven off. The war between Dublin and Limerick continued until 937 when the Dubliners, now led by Gofraid's son Amlaíb, captured Limerick's king Amlaíb Cenncairech

Amlaíb Cenncairech was a Norse ruler and presumably King of Limerick notable for his military activities in Ireland in the 930s, especially in the province of Connacht and apparently even in Ulster and Leinster. This period, the 920s and 930s, ...

and for some reason destroyed his fleet. However, no battle is actually recorded and so a traditional interpretation has been that Amlaíb mac Gofraid was actually recruiting Amlaíb of Limerick for his upcoming conflict with Athelstan of England, which would turn out be the famous Battle of Brunanburh

The Battle of Brunanburh was fought in 937 between Æthelstan, King of England, and an alliance of Olaf Guthfrithson, King of Dublin, Constantine II, King of Scotland, and Owain, King of Strathclyde. The battle is often cited as the poin ...

. The 920s and 930s are regarded as the height of Norse power in Ireland and only Limerick rivalled Dublin during this time.

The last Norse King of Limerick was Ivar of Limerick

Ivar of Limerick ( ga, Ímar Luimnich, rí Gall; Ímar ua Ímair; Ímar Ua hÍmair, Ard Rí Gall Muman ocus Gáedel; Íomhar Mór; non, Ívarr ; died 977), was the last Norse king of the city-state of Limerick, and penultimate ''King of the Fo ...

, who features prominently as an enemy of Mathgamain mac Cennétig

Mathgamain mac Cennétig (also known as Mahon) was King of Munster from around 970 to his death in 976. He was the elder brother of Brian Bóruma.

Mathgamain was the son of Cennétig mac Lorcáin of the Dál gCais. His father died in 951 and ...

and later his famous brother Brian Boru

Brian Boru ( mga, Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig; modern ga, Brian Bóramha; 23 April 1014) was an Irish king who ended the domination of the High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill and probably ended Viking invasion/domination of Ireland. Br ...

in the ''Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib

''Cogad Gáedel re Gallaib'' ("The War of the Irish with the Foreigners") is a medieval Irish text that tells of the depredations of the Vikings and Uí Ímair dynasty in Ireland and the Irish king Brian Boru's great war against them, beginnin ...

''. He and his allies were defeated by the Dál gCais, and after slaying Ivar, Brian would annex Norse Limerick and begin to make it the new capital of his kingdom.

The power of the Norsemen

The Norsemen (or Norse people) were a North Germanic ethnolinguistic group of the Early Middle Ages, during which they spoke the Old Norse language. The language belongs to the North Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages and is the pr ...

never recovered, and they were reduced to the level of a minor clan; however, they often played pivotal parts in the endless power struggles of the next few centuries.

Brian Boru's son, Donnchad (Donough), was routed by Diarmait mac Maíl na mBó, King of Leinster, in the year 1058 when Limerick was burned, a punishment he repeated five years later. A year later Diarmait defeated Donnchad again forcing him to flee overseas and installing Turlough instead. Obviously Limerick was of great importance as evidenced by being a contentious issue between neighbouring chieftains and foreigners who burned and pillaged the city.Ferrar (1787), pp. 11–12 Brian Boru's sons were usually called Kings of north Munster though their reigns were rather disturbed until 1164 when Donnchad mac Briain Donnchadh () is a masculine given name common to the Irish and Scottish Gaelic languages. It is composed of the elements ''donn'', meaning "brown" or "dark" from Donn a Gaelic God; and ''chadh'', meaning "chief" or "noble". The name is also written ...

became King of Munster. His reign was successful, founding monasteries and nunneries, constructing several monuments, including a church on the Rock of Cashel

The Rock of Cashel ( ga, Carraig Phádraig ), also known as Cashel of the Kings and St. Patrick's Rock, is a historic site located at Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland.

History

According to local legends, the Rock of Cashel originated in the ...

, and in his grant bestowing his Limerick Gothic palace to the church he styled himself ''King of Limerick''. However the Danes were still a powerful force who were able to obtain four sequential Danish bishops concentrated by the Archbishop of Canterbury not subservient to the See of Cashel.

Anglo-Norman era

Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

to the area in 1173 changed everything. Domnall Mór Ua Briain

Domnall Mór Ua Briain, or Domnall Mór mac Toirrdelbaig Uí Briain, was King of Thomond in Ireland from 1168 to 1194 and a claimant to the title King of Munster. He was also styled King of Limerick, a title belonging to the O'Brien dynas ...

, the last styled King of Limerick, burned the city to the ground in 1174 in a bid to keep it from the hands of the new invaders. After he died in 1194, the Normans

The Normans ( Norman: ''Normaunds''; french: Normands; la, Nortmanni/Normanni) were a population arising in the medieval Duchy of Normandy from the intermingling between Norse Viking settlers and indigenous West Franks and Gallo-Romans. ...

finally captured the area in 1195, under the leadership of Prince John. In 1197, King Richard I of England

Richard I (8 September 1157 – 6 April 1199) was King of England from 1189 until his death in 1199. He also ruled as Duke of Normandy, Aquitaine and Gascony, Lord of Cyprus, and Count of Poitiers, Anjou, Maine, and Nantes, and was ...

granted the city its first charter

A charter is the grant of authority or rights, stating that the granter formally recognizes the prerogative of the recipient to exercise the rights specified. It is implicit that the granter retains superiority (or sovereignty), and that the rec ...

, and its first Mayor, Adam Sarvant, ten years before London. A castle, built on the orders of King John and bearing his name, was completed around 1200. Under the general peace imposed by Norman rule, Limerick prospered as a port and trading centre. By this time the city was divided into an area which became known as "English Town" on King's Island surrounded by high walls, while another settlement, named "Irish Town", where the Irish and Danes lived, had grown on the south bank of the river. In 1216 King John further granted the areas North (as far as a tributary of the Shannon) and South of the River to City to be known as the "Northern" and "Southern" Liberties. Around 1395 construction started on walls around Irishtown that were not completed until the end of the 15th century.Kemmy, (1987), p. 4

The city opened a mint

MiNT is Now TOS (MiNT) is a free software alternative operating system kernel for the Atari ST system and its successors. It is a multi-tasking alternative to TOS and MagiC. Together with the free system components fVDI device drivers, XaA ...

in 1467. A 1574 document prepared for the Spanish ambassador attests to its wealth:

Limerick is stronger and more beautiful than all the other cities of Ireland, well walled with stout walls of hewn marble...there is no entrance except by stone bridges, one of the two of which has 14 arches, and the other eight ... for the most part the houses are of square stone of black marble and built in the form of towers and fortresses.

Luke Gernon

People

*Luke (given name), a masculine given name (including a list of people and characters with the name)

* Luke (surname) (including a list of people and characters with the name)

*Luke the Evangelist, author of the Gospel of Luke. Also known a ...

, an English-born judge and resident of Limerick, wrote a similar description in 1620:

Lofty building of marble; in the High Street it is built from one gate to the other in a single form, like the Colleges inIn the 15th and 16th centuries, Limerick became a city-state isolated from the principal area of effective English rule -theOxford Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ..., so magnificent that at my first entrance it did amaze me.

Pale

Pale may refer to:

Jurisdictions

* Medieval areas of English conquest:

** Pale of Calais, in France (1360–1558)

** The Pale, or the English Pale, in Ireland

*Pale of Settlement, area of permitted Jewish settlement, western Russian Empire (179 ...

. Nevertheless, the Crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, partic ...

remained in control throughout the succeeding centuries. During the Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

tensions arose between those loyal to the Catholic Church and those loyal to the newly established state religion — the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland ( ga, Eaglais na hÉireann, ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Kirk o Airlann, ) is a Christian church in Ireland and an autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the second ...

.

Siege and treaty

Limerick was besieged several times in the 17th century. The first was in 1642, when the Irish Confederates took the King John's Castle from its English garrison. The city was besieged by

Limerick was besieged several times in the 17th century. The first was in 1642, when the Irish Confederates took the King John's Castle from its English garrison. The city was besieged by Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

's army under Henry Ireton

Henry Ireton ((baptised) 3 November 1611 – 26 November 1651) was an English general in the Parliamentarian army during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and the son-in-law of Oliver Cromwell. He died of disease outside Limerick in November 16 ...

in 1651. The city had supported Confederate Ireland

Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, was a period of Irish Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1649, during the Eleven Years' War. Formed by Catholic aristocrats, landed gentry, clergy and military ...

since 1642 and was garrisoned by troops from Ulster. The Confederates supported the claims of Charles II to the English throne, and the besiegers fought for a parliamentary republic. Famine and plague lead to the death of 5,000 residents before heavy bombardment of Irishtown led to breach and surrender in late October of that year.

In the Williamite war in Ireland

The Williamite War in Ireland (1688–1691; ga, Cogadh an Dá Rí, "war of the two kings"), was a conflict between Jacobite supporters of deposed monarch James II and Williamite supporters of his successor, William III. It is also called th ...

, following the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ga, Cath na Bóinne ) was a battle in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II of England and Ireland, VII of Scotland, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and ...

in 1690, French and Irish forces (numbering 14,000) regrouped in behind Limerick's walls. Time and war had led to a terrible decay of the once proud fortifications. The occupying armies are recorded as claiming that the walls could be knocked down with rotten apples. The Williamite

A Williamite was a follower of King William III of England (r. 1689–1702) who deposed King James II and VII in the Glorious Revolution. William, the Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic, replaced James with the support of English Whigs.

One ...

besiegers, while numbering 20,000, were hampered by the loss of their heavier guns to an attack by Patrick Sarsfield

Patrick Sarsfield, 1st Earl of Lucan, ga, Pádraig Sáirseál, circa 1655 to 21 August 1693, was an Irish soldier, and leading figure in the Jacobite army during the 1689 to 1691 Williamite War in Ireland.

Born into a wealthy Catholic famil ...

. In fierce fighting, the walls were breached on three occasions, but the defenders prevailed. Eventually, the Williamites withdrew to Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

.

William's forces returned in August 1691. Limerick was now the last stronghold of the Catholic Jacobites

Jacobite means follower of Jacob or James. Jacobite may refer to:

Religion

* Jacobites, followers of Saint Jacob Baradaeus (died 578). Churches in the Jacobite tradition and sometimes called Jacobite include:

** Syriac Orthodox Church, sometime ...

, under the command of Sarsfield. The promised French reinforcement failed to arrive from the sea, and following the massacre of 850 defenders on Thomond Bridge, the city sued for peace. On 3 October 1691 the famous Treaty of Limerick

}), signed on 3 October 1691, ended the 1689 to 1691 Williamite War in Ireland, a conflict related to the 1688 to 1697 Nine Years' War. It consisted of two separate agreements, one with military terms of surrender, signed by commanders of a French ...

was signed using a large stone

In geology, rock (or stone) is any naturally occurring solid mass or aggregate of minerals or mineraloid matter. It is categorized by the minerals included, its Chemical compound, chemical composition, and the way in which it is formed. Rocks ...

set in the bridge as a table. The treaty allowed the Jacobites to leave under full military honours and sail to France. Two days later French reinforcements finally arrived. Sarsfield was urged to continue the fight but refused, insisting on abiding by the terms of the treaty. Sarsfield sailed to France with 19,000 troops and formed the Irish Brigade (see also the Flight of the Wild Geese

The Flight of the Wild Geese was the departure of an Irish Jacobite army under the command of Patrick Sarsfield from Ireland to France, as agreed in the Treaty of Limerick on 3 October 1691, following the end of the Williamite War in Ireland. ...

). From 1693 the Papacy supported James II again, and so the treaty was repudiated by the Williamites, for which the city became known as ''The City of the Violated Treaty'' and is a point of bitterness in the city to this day.

Georgian Limerick and Newtown Pery

While in 1695 the repressive penal laws were introduced that banned Catholics from public office, buying freehold land, voting or practising their religion in public, Limerick's position as the main port on the western side of Ireland meant that the city, and the Protestant upper class and the Catholic merchant class, began to prosper. The British version of

While in 1695 the repressive penal laws were introduced that banned Catholics from public office, buying freehold land, voting or practising their religion in public, Limerick's position as the main port on the western side of Ireland meant that the city, and the Protestant upper class and the Catholic merchant class, began to prosper. The British version of mercantilism

Mercantilism is an economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports for an economy. It promotes imperialism, colonialism, tariffs and subsidies on traded goods to achieve that goal. The policy aims to reduce a ...

required a great deal of trans-Atlantic trade, and Limerick profited somewhat by this. Many significant public buildings and infrastructure projects were paid for with local trade taxes. The first infirmary was founded by the surgeon Sylvester O'Halloran

Sylvester O'Halloran (31 December 1728 – 11 August 1807) was an Irish surgeon with an abiding interest in Gaelic poetry and history. For most of his life he lived and practised in Limerick, and was later elected a member of the Royal Iri ...

in 1761. The House of Industry was built on northern bank of the river in 1774, in part as a poorhouse and infirmary. The late 17th and early 18th century saw a rapid expansion of the city as Limerick took on the appearance of a Georgian City. It was during this time that the city centre took on its present-day look with the planned terraced Georgian Townhouses a characteristic of the city today. Georgian Limerick dates from this period as part of Edmund Sexton Pery

Edmund Sexton Pery, 1st Viscount Pery (8 April 1719 – 24 February 1806; middle name also spelt ''Sexten'') was an Ireland, Anglo-Irish politician who served as Speaker of the Irish House of Commons between 1771 and 1785.

Early life

He was born ...

's plan for the development of a new city on lands he owned to the south of the existing medieval city. In 1765, he commissioned the Italian engineer Davis Ducart

Davis Ducart (active from c. 1761, died 1780/81), was an architect and engineer in Ireland in the 1760s and 1770s. He designed several large buildings and engineering projects. He had associations with the canal builders of the time and the mining ...

to design a town plan on those lands which have since become known as Newtown Pery. The town was built in stages as Pery sold off leases to builders and developers who built four- and five-story townhouses in the Georgian fashion with long wide and elegant streets in grid plan design with O'Connell Street

O'Connell Street () is a street in the centre of Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, running north from the River Liffey. It connects the O'Connell Bridge to the south with Parnell Street to the north and is roughly split into two sections ...

(previously Georges street) being laid out at this time also and forming the centre of the new town. The earliest Georgian houses are located in John's Square in the Irishtown district of medieval Limerick and along Bank Place, Rutland Street & Patrick Street in the Newtown Pery district which were built by the Arthur family — a prominent Limerick family during the 18th century. Some of Ireland's finest examples of Georgian Architecture can be seen at the Crescent area and Pery Square. A basic sewer system was built in Newtownpery in the reign of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great Br ...

by simply closing over the gutters. By the time of George's reign, Limerick had 17 gates in the city walls, most of whose names continue in modern city placenames. St. Joseph's Hospital was completed in the south-side by 1827. Wellesley Bridge (later, Sarsfield Bridge) and new wet docks were also built during this time. Chief imports through the port included timber, coal, iron and tar. Exports included beef, pork, wheat, oats, flour and emigrants bound for North America. Exports of food continued during the Great Famine, often requiring the deployment of troops to protect the port.

The new, broad wide and elegant streets of Newtown Pery quickly attracted the city's wealthiest families who left the old overcrowded narrow lanes and streets of medieval Limerick (Englishtown & Irishtown) and marked the decline of the ancient and medieval quarter of Limerick. These parts of the city were left to the poorer citizens of Limerick and became characterised by poverty and squalor. Unfortunately some tangible links to Limerick's eventful past were lost as historically important buildings were lost due to lack of maintenance such as the Exchange, Ireton's Castle (from the siege of Limerick), and a collection of Flemish and Dutch styled housing that started after the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

(with some surviving up to the mid 20th Century) that fronted onto Nicholas Street, Mary Street, Broad Street & Mungret Street that were eventually knocked due to poor condition.

Great Irish Famine

No statistics exist on how many people in the Limerick area died during the famine. Nationally, the population declined by an average of 20%, half of whom died and half emigrated. While the Great Famine reduced the population ofCounty Limerick

"Remember Limerick"

, image_map = Island_of_Ireland_location_map_Limerick.svg

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Ireland

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = Munster

, subdivision ...

by 70,000, the population of the City actually rose slightly, as people fled to the workhouses

In Britain, a workhouse () was an institution where those unable to support themselves financially were offered accommodation and employment. (In Scotland, they were usually known as poorhouses.) The earliest known use of the term ''workhouse'' ...

.

Ships berthed on the Limerick quaysides ready to transport produce from one of the most fertile parts of Ireland, the Golden Vale

The Golden Vale ()

is an area of rolling pastureland in the civil province of Munster, southwestern Ireland. Covering parts of three counties, Limerick, Tipperary and Cork, it is the best land in Ireland for dairy farming.

Historically it ...

, to the English ports.Laxton (1998), pp.. 185–187 Francis Spaight, a Limerick merchant, farmer, British magistrate and ship owner, recorded 386,909 barrels of oats, and 46,288 barrels of wheat being shipped out of Limerick between June 1846 and May 1847. Giving evidence to a British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative supremacy ...

select committee Select committee may refer to:

*Select committee (parliamentary system), a committee made up of a small number of parliamentary members appointed to deal with particular areas or issues

*Select or special committee (United States Congress)

*Select ...

inquiring into the famine, Spaight said that:

I found so great an advantage of getting rid of the pauper population upon my own property that I made every possible exertion to remove them ... I consider the failure of the potato crop to be the greatest possible value in one respect in enabling us to carry out the emigration system.The same quaysides were the departure point for many emigrant ships sailing over the Atlantic. One week in April 1850 saw four ships, ''Marie Brennan'', ''Congress'', ''Triumph'', an 1849

Youghal

Youghal ( ; ) is a seaside resort town in County Cork, Ireland. Located on the estuary of the River Blackwater, the town is a former military and economic centre. Located on the edge of a steep riverbank, the town has a long and narrow layout. ...

built ship, and ''Hannah'', the smallest emigrant ship, glide down the Shannon towards the Americas. The latter three ship had 357 people aboard mostly comprising young men and women, depriving Ireland of their vigour and prosperity which they would bring to other nations instead. The ''Hannah'' at 59 feet long could barely hold the 60 passengers and eight crew, yet made eight trans-Atlantic voyages.

Boycott against Limerick Jews

Census returns record one Jew in Limerick in 1861. This doubled by 1871 and doubled again by 1881. Increases to 35, 90 and 130 are shown for 1888, 1892, and 1896 respectively. A small number ofLithuanian Jewish

Lithuanian Jews or Litvaks () are Jews with roots in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania (covering present-day Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, the northeastern Suwałki and Białystok regions of Poland, as well as adjacent areas o ...

tradespeople, fleeing persecution in their homeland, began arriving in Limerick in 1878. They initially formed an accepted part of the city's retail trade, centred on Collooney St. The community established a synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

and a cemetery in the 1880s. Easter Sunday

Easter,Traditional names for the feast in English are "Easter Day", as in the ''Book of Common Prayer''; "Easter Sunday", used by James Ussher''The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4'') and Samuel Pepys''The Diary of Samuel ...

of 1884 saw the first of what were to be a series of sporadic violent antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

attacks and protests. The wife of Lieb Siev and their child were injured by stones and their house damaged by an angry crowd for which the ringleaders were sentenced to hard labour for a month.Keogh (1998), p. 19 In 1892 two families were beaten and a stoning took place on 24 November 1896. Many details about Limerick's Jewish families are recorded in the 1901 census that shows most were peddler

A peddler, in British English pedlar, also known as a chapman, packman, cheapjack, hawker, higler, huckster, (coster)monger, colporteur or solicitor, is a door-to-door and/or travelling vendor of goods.

In England, the term was mostly used fo ...

s, though a few were described as drapery dealers and grocers.Keogh (1998), pp.. 12–14

In 1904 a young Catholic priest, Father John Creagh

John Creagh (Thomondgate, Limerick, Ireland; 1870 – Wellington, New Zealand; 1947) was an Irish Redemptorist priest. Creagh is best known for, firstly, delivering antisemitic speeches in 1904 responsible for inciting riots against the smal ...

, of the Redemptorist

The Redemptorists officially named the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer ( la, links=no, Congregatio Sanctissimi Redemptoris), abbreviated CSsR,is a Catholic clerical religious congregation of pontifical right for men (priests and brother ...

order, delivered a fiery sermon castigating Jews for rejecting the divinity of Jesus Christ

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religious ...

, usury

Usury () is the practice of making unethical or immoral monetary loans that unfairly enrich the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is ch ...

Keogh (1998), pp.. 26–30 alliance with the Freemasons

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

then persecuting the Catholic Church in France

, native_name_lang = fr

, image = 060806-France-Paris-Notre Dame.jpg

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral Notre-Dame de Paris

, abbreviation =

, type ...

, taking over Limerick's economy, selling shoddy goods at inflated prices paid in instalments. He urged Catholics "not to deal with the Jews." Later, after 32 Jews left Limerick due to the agitation, Fr. Creagh was disowned by his superiors who said that: ''religious persecution had no place in Ireland.'' The Limerick Pogrom was the economic boycott waged against the small Jewish community for over two years. Keogh suggests the name derives from their previous Lithuanian experience even though no Jews in Limerick were killed or even seriously injured. Limerick's Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

s, many of whom were also traders, supported the Jews throughout the pogrom, but ultimately five Jewish families left the city and 26 families remained.

Some went to Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

, intending to embark on ships from Cobh

Cobh ( ,), known from 1849 until 1920 as Queenstown, is a seaport town on the south coast of County Cork, Ireland. With a population of around 13,000 inhabitants, Cobh is on the south side of Great Island in Cork Harbour and home to Ireland's ...

to travel to America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. The people of Cork welcomed them into their homes. Church halls were opened for the refugees, many of whom remained. Gerald Goldberg

Gerald Yael Goldberg (12 April 1912 – 31 December 2003) was an Irish lawyer and politician who in 1977 became the first Jewish Lord Mayor of Cork. Goldberg was the son of Lithuanian Jewish refugees; his father was put ashore in Cork with oth ...

, a son of this migration, became Lord Mayor of Cork

The Lord Mayor of Cork ( ga, Ard-Mhéara Chathair Chorcaí) is the honorific title of the Chairperson ( ga, Cathaoirleach) of Cork City Council which is the local government body for the city of Cork (city), Cork in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. ...

in 1977, and the Marcus brothers, David

David (; , "beloved one") (traditional spelling), , ''Dāwūd''; grc-koi, Δαυΐδ, Dauíd; la, Davidus, David; gez , ዳዊት, ''Dawit''; xcl, Դաւիթ, ''Dawitʿ''; cu, Давíдъ, ''Davidŭ''; possibly meaning "beloved one". w ...

and Louis Louis may refer to:

* Louis (coin)

* Louis (given name), origin and several individuals with this name

* Louis (surname)

* Louis (singer), Serbian singer

* HMS ''Louis'', two ships of the Royal Navy

See also

Derived or associated terms

* Lewis ( ...

, grandchildren of the pogrom, would become hugely influential in Irish literature and Irish film, respectively.

Struggle for independence

The

The IRA

Ira or IRA may refer to:

*Ira (name), a Hebrew, Sanskrit, Russian or Finnish language personal name

*Ira (surname), a rare Estonian and some other language family name

*Iran, UNDP code IRA

Law

*Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, US, on status of ...

and the independence movement of Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Gri ...

gained popular support in Limerick following the repressions and executions of 1916

Events

Below, the events of the First World War have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 1 – The British Royal Army Medical Corps carries out the first successful blood transfusion, using blood that had been stored and cooled.

* ...

. Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ga, Constáblacht Ríoga na hÉireann; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the country was part of the United Kingdom. A separate ...

carried out violent raids on the homes of suspected Sinn Féin sympathisers. Prisoners were interned without trial in Frongoch camp in North Wales

Wales ( cy, Cymru ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by England to the Wales–England border, east, the Irish Sea to the north and west, the Celtic Sea to the south west and the ...

. Following the arrest and death of Robert Byrne, a local republican and trade unionist, most of Limerick city and a part of the county were declared a "Special Military Area under the Defence of the Realm Act

The Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was passed in the United Kingdom on 8 August 1914, four days after it entered the First World War and was added to as the war progressed. It gave the government wide-ranging powers during the war, such as the p ...

". Special permits, to be issued by the RIC, would now be required to enter the city. In response, the Limerick Trades and Labour Council called for a general strike and boycott of the troops. A special strike committee was set up to print their own money and control food prices. ''The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

'' referred to this committee as a Limerick Soviet

The Limerick Soviet ( ga, Sóibhéid Luimnigh) was one of a number of self-declared Irish soviets that were formed around Ireland circa 1919. The Limerick Soviet existed for a two-week period from 15 to 27 April 1919. At the beginning of the Ir ...

; however, the high degree of involvement of the Catholic Church shows that it was in fact quite different from the recent Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks (russian: Большевики́, from большинство́ ''bol'shinstvó'', 'majority'),; derived from ''bol'shinstvó'' (большинство́), "majority", literally meaning "one of the majority". also known in English ...

uprising. An American army officer arriving in Limerick had to appear before the permits committee to get a lift to visit relatives outside Limerick, following which he said,

I guess it is some puzzle to know who rules these parts. You have to get a military permit to get in and be brought before a committee to get a permit to leave.After 14 days the strike ended with a compromise on the permits issue. Open conflict erupted on Roches Street in April 1920 between the

Royal Welch Fusiliers

The Royal Welch Fusiliers ( cy, Ffiwsilwyr Brenhinol Cymreig) was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, and part of the Prince of Wales' Division, that was founded in 1689; shortly after the Glorious Revolution. In 1702, it was designated ...

and the general population, involving bayonets on the one side and stones and bottles on the other. The troops fired indiscriminately, killing a publican and an usherette from the Coliseum Cinema. The British Government organised a new force to quell the population. The Black and Tans

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white have ...

, known as "the sweepings of English jails", were formed of ex-servicemen. On the night of 6 March 1921, Limerick's Mayor, George Clancy, and his wife were shot in their home by three Tans. On the same night the previous Mayor, Michael O'Callaghan, and Volunteer Joe O'Donoghue were murdered in their own homes after curfew. These assassinations became known as the Curfew Murders. IRA reprisals included the unsuccessful attack on six RIC men leaving a pub on Mungret Street and the shooting dead of a Black and Tan on Church Street. A truce between the IRA and the British forces came into effect on 9 July 1921.

Free State

On 5 December 1921

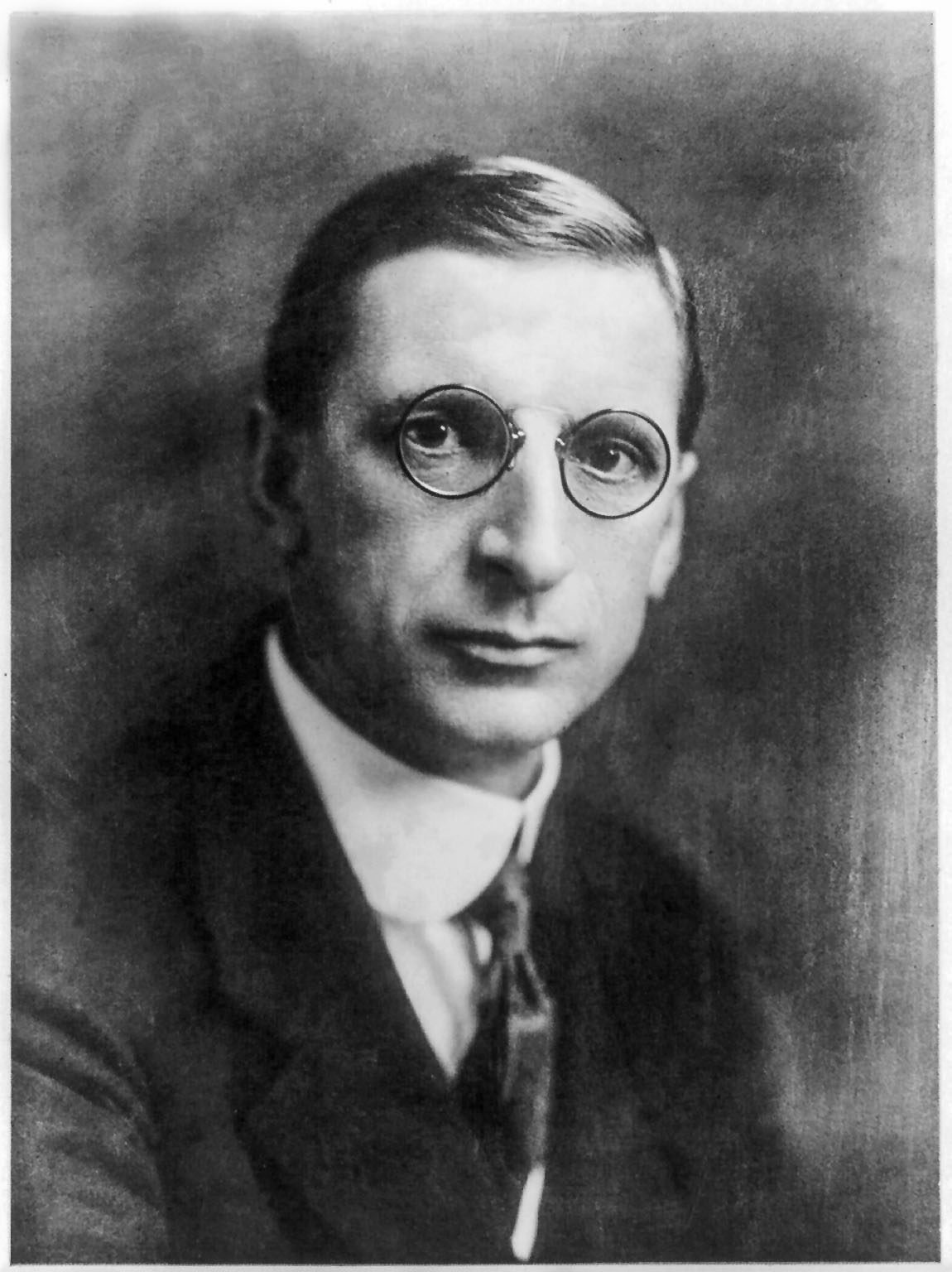

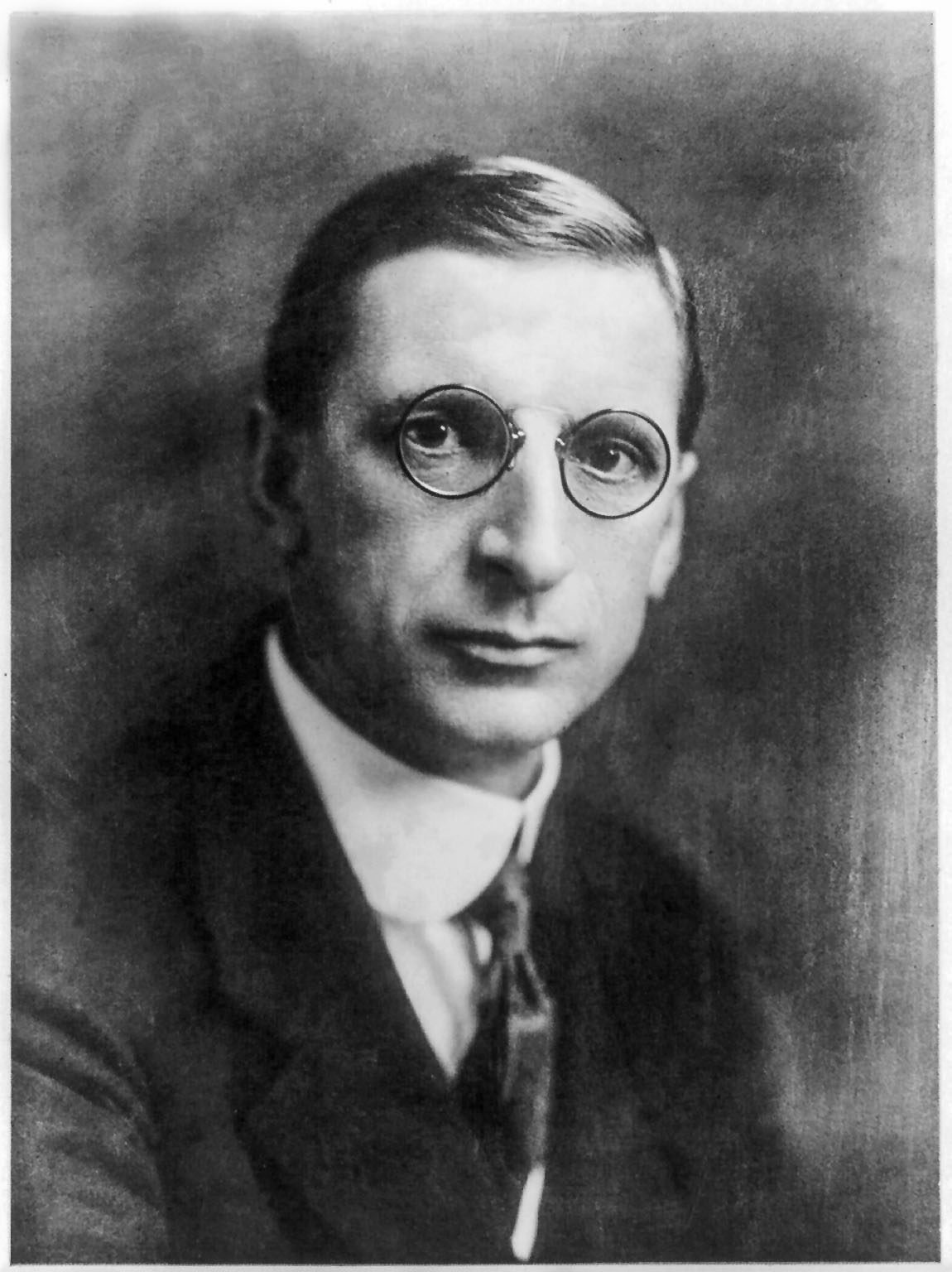

On 5 December 1921 Éamon de Valera

Éamon de Valera (, ; first registered as George de Valero; changed some time before 1901 to Edward de Valera; 14 October 1882 – 29 August 1975) was a prominent Irish statesman and political leader. He served several terms as head of governm ...

gave a speech (in what is now The Strand Hotel on the Ennis Road) cautioning against optimism in the peace process. A few hours later in London, Michael Collins Michael Collins or Mike Collins most commonly refers to:

* Michael Collins (Irish leader) (1890–1922), Irish revolutionary leader, soldier, and politician

* Michael Collins (astronaut) (1930–2021), American astronaut, member of Apollo 11 and Ge ...

signed the Anglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty ( ga , An Conradh Angla-Éireannach), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the ...

, granting limited independence to the southern portion of Ireland as the Irish Free State

The Irish Free State ( ga, Saorstát Éireann, , ; 6 December 192229 December 1937) was a state established in December 1922 under the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921. The treaty ended the three-year Irish War of Independence between th ...

, while retaining the six counties of Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. The treaty also gifted the ports of Berehaven

Castletownbere () is a town in County Cork in Ireland. It is located on the Beara Peninsula by Berehaven Harbour. It is also known as Castletown Berehaven.

A regionally important fishing port, the town also serves as a commercial and retail hub ...

, Cobh and Lough Swilly

Lough Swilly () in Ireland is a glacial fjord or sea inlet lying between the western side of the Inishowen, Inishowen Peninsula and the Fanad Peninsula, in County Donegal. Along with Carlingford Lough and Killary Harbour it is one of three glaci ...

to the United Kingdom as UK sovereign bases, while annuities would continue to be paid to the British government in lieu of money loaned to Irish tenants under various land acts. De Valera and others virulently opposed the treaty's compromises. The scene was set for the civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

.

In Limerick, the first signs of trouble came when the British forces withdrew early in the New Year. Three separate Irish factions rushed in to fill the vacuum: The pro-Treaty Claremen of the First-Western Division under General Michael Brennan, who was asked by the new Free-State government to occupy the city because of doubts about the loyalty of Liam Forde's Mid-Limerick Brigade. In the event the Brigade split into pro- and anti-Treaty factions, the latter led by Forde.

William St. became a battle zone by 7 p.m. on 11 July 1922, when the Free State troops opened fire on the Republican garrison holding the Ordnance Barracks. In the chaos, Roches Stores, which still stands on Sarsfield St, was looted. On 17 July, Eoin O'Duffy

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy; 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was an Irish military commander, police commissioner and politician. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a prominent figure in ...

arrived in the city as part of a nationwide offensive, in command of 1,500 Free State reinforcements equipped with artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

.

The Free State forces brought up an 18-pounder gun on the 19th and blasted a breach in walls of the Ordnance Barracks, which they then stormed. The Castle Barracks was captured the following day. The Republicans then abandoned the city, burning the barracks still in their hands. Limerick Prison, designed to hold 120, contained 800 prisoners by November. The fighting in the city in July 1922, left six Free State soldiers and 12 civilians dead, with a further 87 wounded. The press reports stated that about thirty Anti-Treaty IRA men had been killed but a recent study puts their fatalities at just five.

The Civil War ended the following May in victory for the Free State. De Valera and the Republicans would refuse to take their seats in the new Dáil Éireann

Dáil Éireann ( , ; ) is the lower house, and principal chamber, of the Oireachtas (Irish legislature), which also includes the President of Ireland and Seanad Éireann (the upper house).Article 15.1.2º of the Constitution of Ireland read ...

until 1927.

The Free State government set about rebuilding the county in the spirit of the times, with grand plans and schemes. The Shannon Scheme

The Shannon hydroelectric Scheme was a major development by the Irish Free State in the 1920s to harness the power of the River Shannon. Its product, the Ardnacrusha power plant, is a hydroelectric power station which is still producing power ...

, the plan to build a Hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other renewable sources combined and ...

power station utilising the energy of Ireland's largest river, was begun in 1925. The German electric company Siemens-Schuckertwerke

Siemens-Schuckert (or Siemens-Schuckertwerke) was a German electrical engineering company headquartered in Berlin, Erlangen and Nuremberg that was incorporated into the Siemens AG in 1966.

Siemens Schuckert was founded in 1903 when Siemens & ...

(today Siemens AG

Siemens AG ( ) is a German multinational conglomerate corporation and the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe headquartered in Munich with branch offices abroad.

The principal divisions of the corporation are ''Industry'', '' ...

) was awarded the 5.2 million pound contract, providing employment for 750 people. The Electricity Supply Board

The Electricity Supply Board (ESB; ga, Bord Soláthair an Leictreachais) is a state owned (95%; the rest are owned by employees) electricity company operating in the Republic of Ireland. While historically a monopoly, the ESB now operates as ...

set up to manage the project gradually oversaw the electrification of rural Ireland.

The Emergency

Almost from the moment that de Valera and his newFianna Fáil

Fianna Fáil (, ; meaning 'Soldiers of Destiny' or 'Warriors of Fál'), officially Fianna Fáil – The Republican Party ( ga, audio=ga-Fianna Fáil.ogg, Fianna Fáil – An Páirtí Poblachtánach), is a conservative and Christian- ...

party were elected in 1932, Ireland was plunged into a series of "emergencies". De Valera fulfilled an election promise to suspend the payment of land annuities to Britain, and Britain retaliated by raising import duties on agricultural products to 40%. De Valera swept through the Dáil the "Emergency Imposition of Duties order" imposing reciprocal taxes. The Anglo-Irish Trade War

The Anglo-Irish Trade War (also called the Economic War) was a retaliatory trade war between the Irish Free State and the United Kingdom from 1932 to 1938. The Irish government refused to continue reimbursing Britain with land annuities from fi ...

had begun.

Limerick's farm-based economy was reduced to a state of barter. This was the period during which Ireland's interventionist, control economic style was developed. The Laissez-faireism of the 1920s was abandoned in the face of skyrocketing unemployment, poverty and emigration. The state set up non-agricultural industries such as Turf Development Board (Later

Limerick's farm-based economy was reduced to a state of barter. This was the period during which Ireland's interventionist, control economic style was developed. The Laissez-faireism of the 1920s was abandoned in the face of skyrocketing unemployment, poverty and emigration. The state set up non-agricultural industries such as Turf Development Board (Later Bord na Móna

Bord na Móna (; English: "The Peat Board"), is a semi-state company in Ireland, created in 1946 by the Turf Development Act 1946. The company began developing the peatlands of Ireland with the aim to provide economic benefit for Irish Midland c ...

) and Aer Rianta

DAA (styled "daa"), previously Dublin Airport Authority, is a commercial semi-state airport company in Ireland. The company owns and operates Dublin Airport and Cork Airport. Its other subsidiaries include the travel retail business Aer Rianta ...

(airports authority). In 1935 Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

was consulted on the building of an airport on the Shannon Estuary at Rineanna (later renamed Shannon Airport

Shannon Airport ( ga, Aerfort na Sionainne) is an international airport located in County Clare in the Republic of Ireland. It is adjacent to the Shannon Estuary and lies halfway between Ennis and Limerick. The airport is the third busiest ai ...

), and in 1937 Foynes

Foynes (; ) is a town and major port in County Limerick in the midwest of Ireland, located at the edge of hilly land on the southern bank of the Shannon Estuary. The population of the town was 520 as of the 2016 census.

Foynes's role as seap ...

was developed as a stopping point on the flying boat

A flying boat is a type of fixed-winged seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in that a flying boat's fuselage is purpose-designed for floatation and contains a hull, while floatplanes rely on fusela ...

route across the Atlantic. During this time, the de Valera government introduced several ''emergency'' laws to suppress the IRA and General Eoin O'Duffy

Eoin O'Duffy (born Owen Duffy; 28 January 1890 – 30 November 1944) was an Irish military commander, police commissioner and politician. O'Duffy was the leader of the Monaghan Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and a prominent figure in ...

's Blueshirt Anti-Fianna Fáil supporters.

This first ''Emergency

An emergency is an urgent, unexpected, and usually dangerous situation that poses an immediate risk to health, life, property, or environment and requires immediate action. Most emergencies require urgent intervention to prevent a worsening ...

'' ended in 1938 with the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement

The Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement was signed on 25 April 1938 by Ireland and the United Kingdom. It aimed to resolve the Anglo-Irish Trade War which had been on-going from 1933.

Scope

The prime minister Neville Chamberlain summarised the 4 possibl ...

, when Neville Chamberlain

Arthur Neville Chamberlain (; 18 March 18699 November 1940) was a British politician of the Conservative Party who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from May 1937 to May 1940. He is best known for his foreign policy of appeasemen ...

's appeasement policy allowed a climb down. The UK would end economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they may ...

and return the treaty ports

Treaty ports (; ja, 条約港) were the port cities in China and Japan that were opened to foreign trade mainly by the unequal treaties forced upon them by Western powers, as well as cities in Korea opened up similarly by the Japanese Empire.

...

in exchange for a once-off payment of £10m.

The following year, the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

forced the introduction of the Emergency Powers Act 1939

The Emergency Powers Act 1939 (EPA) was an Act of the Oireachtas (Irish parliament) enacted on 3 September 1939, after an official state of emergency had been declared on 2 September 1939 in response to the outbreak of the Second World War. The ...

to control communications, media, prices and imports. Ireland, with no native merchant fleet, and no coal, gas, or oil supplies faced hard times indeed. An army officer named Captain McKenna described it as the day "''Realisation dawned on Ireland that the country was surrounded by water, and that the sea was of vital importance to her''." Towards the end of the war, shortages of rubber and petrol particularly ended all non-emergency motorised transport, including rail, to and within the city. Lord Adare restarted a four-horse stagecoach route to his hotel in Co. Limerick, a sight not seen since the 19th century.

The army was expanded massively to over 300,000 in preparation for the expected invasion by either Germany, attempting a stepping-stone approach to the invasion of Britain, or Britain herself, seeking use of the ports. Knockalisheen barracks (later Knockalisheen Refugee Camp) was built near Limerick at Meelick to house the new defence forces.

Post war

The economy of the Limerick area was largely neglected in the post war period and the city and county became characterised by extremely high emigration and unemployment. With the exception ofShannon Airport

Shannon Airport ( ga, Aerfort na Sionainne) is an international airport located in County Clare in the Republic of Ireland. It is adjacent to the Shannon Estuary and lies halfway between Ennis and Limerick. The airport is the third busiest ai ...

and a few related businesses and a few clothing factories, Limerick had no industry. The economy was based on farming and services, fuelled in no insignificant part by remittances from the extensive diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of origin. Historically, the word was used first in reference to the dispersion of Greeks in the Hellenic world, and later Jews after ...

. A few of the many who left became successful abroad, including the actor Richard Harris

Richard St John Francis Harris (1 October 1930 – 25 October 2002) was an Irish actor and singer. He appeared on stage and in many films, notably as Corrado Zeller in Michelangelo Antonioni's '' Red Desert'', Frank Machin in ''This Sporting ...

, the BBC presenter Terry Wogan

Sir Michael Terence Wogan (; 3 August 1938 – 31 January 2016) was an Irish radio and television broadcaster who worked for the BBC in the UK for most of his career. Between 1993 and his semi-retirement in December 2009, his BBC Radio 2 weekd ...

, and the school teacher turned memoirist, Frank McCourt

Francis McCourt (August 19, 1930July 19, 2009) was an Irish-American teacher and writer. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his book ''Angela's Ashes'', a tragicomic memoir of the misery and squalor of his childhood.

Early life and education

Frank McC ...

.

Limerick also had a few famous visitors during this time. In 1963 Irish-American US President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until his assassination ...

visited Limerick as part of his tour of Ireland. He was presented with a locally produced christening robe made of Limerick Lace

Limerick lace is a specific class of lace originating in Limerick, Ireland, which was later produced throughout the country. It evolved from the invention of a machine which made net in 1808. Until John Heathcoat invented a net-making machine in D ...

. From 1956, about 500 Hungarian refugee

A refugee, conventionally speaking, is a displaced person who has crossed national borders and who cannot or is unwilling to return home due to well-founded fear of persecution.

s were housed in Knockalisheen, near Meelick a few kilometres from the city, following the failed uprising in their country. A few settled, but the majority moved on within a few years to new lives in the UK and North America due to the bad economic situation in Limerick.

Shannon Airport also attracted a varied crowd. At this time nearly all transatlantic flights stopped at the airport, the most westerly in Europe, to refuel. Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

journalist Arthur Quinlan who was based at Shannon boasts at having interviewed every US president from Harry Truman

Harry S. Truman (May 8, 1884December 26, 1972) was the 33rd president of the United States, serving from 1945 to 1953. A leader of the Democratic Party, he previously served as the 34th vice president from January to April 1945 under Franklin ...

to George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushSince around 2000, he has been usually called George H. W. Bush, Bush Senior, Bush 41 or Bush the Elder to distinguish him from his eldest son, George W. Bush, who served as the 43rd president from 2001 to 2009; pr ...

and many Soviet leaders, including Andrey Vyshinsky

Andrey Yanuaryevich Vyshinsky (russian: Андре́й Януа́рьевич Выши́нский; pl, Andrzej Wyszyński) ( – 22 November 1954) was a Soviet politician, jurist and diplomat.

He is known as a state prosecutor of Joseph ...

and Andrei Gromyko

Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko (russian: Андрей Андреевич Громыко; be, Андрэй Андрэевіч Грамыка; – 2 July 1989) was a Soviet communist politician and diplomat during the Cold War. He served as ...

. He also famously taught Fidel Castro

Fidel Alejandro Castro Ruz (; ; 13 August 1926 – 25 November 2016) was a Cuban revolutionary and politician who was the leader of Cuba from 1959 to 2008, serving as the prime minister of Cuba from 1959 to 1976 and president from 1976 to 200 ...

how to make an Irish coffee

Irish coffee ( ga, caife Gaelach) is a caffeinated alcoholic drink consisting of Irish whiskey, hot coffee and sugar, which has been stirred and topped with cream (sometimes cream liqueur). The coffee is drunk through the cream.

Origin

Different ...

and interviewed Che Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

. On 13 March 1965, Guevara suddenly arrived at the airport when his flight from Prague to Cuba developed mechanical problems, and Quinlan was on hand to interview him. Guevara talked of his Irish connections through the name Lynch and of his grandmother's Irish roots in Galway

Galway ( ; ga, Gaillimh, ) is a City status in Ireland, city in the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, which is the county town of County Galway. It lies on the River Corrib between Lo ...

. Later, Che, and some of his Cuban comrades, went to Limerick city and adjourned to the Hanratty's Hotel on Glentworth Street. According to Quinlan, they returned that evening all wearing sprigs of shamrock, for Shannon and Limerick were preparing for the St. Patrick's Day celebrations.

In 1968, the government published the Buchanan Report on the regional dimension to economic planning which had largely been ignored. The report recommended on the social and economic sustainability of industry in the regions, which gradually lead to investment and improvement in the Limerick area.

Celtic Tiger

Celtic Tiger

The "Celtic Tiger" ( ga, An Tíogar Ceilteach) is a term referring to the economy of the Republic of Ireland, economy of Ireland from the mid-1990s to the late 2000s, a period of rapid real economic growth fuelled by foreign direct investment. ...

'', making Ireland one of the richest countries in the world, had deep foundations stretching back through the 1980s and 1970s. Shipping in Shannon estuary was developed extensively during the period with more than two billion pounds investment. A tanker terminal at Foynes and an oil jetty at Shannon Airport were built. In 1982 a massive alumina extraction plant was built at Aughinish. Now, 60,000-ton cargo vessels carry raw bauxite from West African mines to the plant, where it is refined to alumina. This is then exported to Canada, where it is further refined to aluminium. In 1985, a huge power plant began operating at Moneypoint, fed by regular visits by 150,000-tonne tankers. European Economic Community

The European Economic Community (EEC) was a regional organization created by the Treaty of Rome of 1957,Today the largely rewritten treaty continues in force as the ''Treaty on the functioning of the European Union'', as renamed by the Lisb ...

funding was poured into infrastructure. Industrial estates at Raheen and Plassey

Palashi or Plassey ( bn, পলাশী, Palāśī, translit-std=ISO, , ) is a village on the east bank of Bhagirathi River, located approximately 50 kilometres north of the city of Krishnanagar in Kaliganj CD Block in the Nadia Distric ...

(Castletroy

Castletroy (, meaning O'Troy's Landing or O'Troy's Callow) is a suburb of Limerick, Ireland. The town was named after Castle Troy also known as The Black Castle, which is located on the southern bank of the River Shannon, roughly 2km East of th ...

), and energetic government intervention, brought in numerous foreign firms, notably Analog Devices

Analog Devices, Inc. (ADI), also known simply as Analog, is an American multinational semiconductor company specializing in data conversion, signal processing and power management technology, headquartered in Wilmington, Massachusetts.

The co ...

, Wang Laboratories

Wang Laboratories was a US computer company founded in 1951 by An Wang and G. Y. Chu. The company was successively headquartered in Cambridge, Massachusetts (1954–1963), Tewksbury, Massachusetts (1963–1976), and finally in Lowell, Massachusett ...

and Dell Computers. A science and engineering focused third-level college called '' NIHE, Limerick'', elevated in 1989 to university status as the University of Limerick

The University of Limerick (UL) ( ga, Ollscoil Luimnigh) is a Public university, public research university institution in Limerick, Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Founded in 1972 as the National Institute for Higher Education, Limerick, it beca ...

, and the establishment of Limerick Institute of Technology

The Limerick Institute of Technology (LIT; ga, Institiúid Teicneolaíochta Luimnigh) was an institute of technology, located in Limerick, Ireland. The institute had five campuses that were located in Limerick, Thurles, Clonmel, as well as a r ...

, furthered the area's reputation as Ireland's Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley is a region in Northern California that serves as a global center for high technology and innovation. Located in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, it corresponds roughly to the geographical areas San Mateo County ...

. Thomond College of Education, Limerick

Thomond College of Education, Limerick (''Coláiste Oideachais Thuamhurnhan, Luimneach'' in Irish) was established in 1973 in Limerick, Ireland as the ''National College of Physical Education'' to train physical education teachers. The college w ...

was a successful teacher training college and was integrated into the university in 1991.

In 1996, the city had a brief moment of world attention when the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

writer Frank McCourt

Francis McCourt (August 19, 1930July 19, 2009) was an Irish-American teacher and writer. He won a Pulitzer Prize for his book ''Angela's Ashes'', a tragicomic memoir of the misery and squalor of his childhood.

Early life and education

Frank McC ...

published ''Angela's Ashes

''Angela's Ashes: A Memoir'' is a 1996 memoir by the Irish-American author Frank McCourt, with various anecdotes and stories of his childhood. The book details his very early childhood in Brooklyn, New York, US but focuses primarily on his life ...

'' for which he won the Pulitzer prize

The Pulitzer Prize () is an award for achievements in newspaper, magazine, online journalism, literature, and musical composition within the United States. It was established in 1917 by provisions in the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made h ...

. The book tells of the author's childhood in a rundown and dirty slum of the 1930s and 40s, In 1999, it was made into a feature film

A feature film or feature-length film is a narrative film (motion picture or "movie") with a running time long enough to be considered the principal or sole presentation in a commercial entertainment program. The term ''feature film'' originall ...

. The slums spoken of in the book had long since been removed, and local people were embarrassed by the sudden unflattering discussion of the city. When McCourt wrote the book's sequel, '' 'Tis'', it was answered with the locally written ''Tisn't'', which painted a better face on the city.

The appearance of the city has been undergoing a gradual face-lift: two new bridges over the Shannon, and a newly opened tunnel complete the orbital road

A ring road (also known as circular road, beltline, beltway, circumferential (high)way, loop, bypass or orbital) is a road or a series of connected roads encircling a town, city, or country. The most common purpose of a ring road is to assist i ...

; many of the older buildings have been replaced, some controversially such as the ancient Cruises Hotel (see Architecture of Limerick

As with other cities in Ireland, Limerick has a history of great architecture. A 1574 document prepared for the Spanish ambassador attests to its wealth and fine architecture:

:Limerick is stronger and more beautiful than all the other cities o ...

). Former city architect, Jim Barrett, led the way in turning Limerick around to face the river. Ireland's third tallest building, the Riverpoint

Riverpoint is a two-tower mixed-use building complex located in Limerick, Ireland. Standing at it is currently the eight-tallest storeyed building in the nation, the sixteenth-tallest on the island of Ireland and the third-tallest in Munster a ...

, was completed in 2006 near Steamboat Quay, an area of fashionable restaurants overlooking the Shannon. The new wealth not only halted the high levels of emigration chronic through the 1980s, but led to the first large-scale immigration for centuries. The city now boasts a Russian delicatessen, a Chinese supermarket and several South Asian, African and Caribbean food shops. Near the Crescent Shopping Centre

The Crescent Shopping Centre is a major shopping centre serving Limerick, Ireland. It is located in Dooradoyle, on the southern outskirts of the city. The complex in its original form was opened in 1973, making it one of the earlier shopping cen ...

, and down the road from the LDS Church

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a Nontrinitarianism, nontrinitarian Christianity, Christian church that considers itself to be the Restorationism, restoration of the ...

, is Limerick's first Mosque.

Post-2008 Crash

The2008 Global Financial Crisis

8 (eight) is the natural number following 7 and preceding 9.

In mathematics

8 is:

* a composite number, its proper divisors being , , and . It is twice 4 or four times 2.

* a power of two, being 2 (two cubed), and is the first number of t ...

, and the resulting Post-2008 Irish economic downturn

The post-2008 Irish economic downturn in the Republic of Ireland, coincided with a series of banking scandals, followed the 1990s and 2000s Celtic Tiger period of rapid real economic growth fuelled by foreign direct investment, a subsequent pr ...

caused economic damage to Limerick. Like other cities in Ireland, house prices collapsed by 50% from the pre-crash highs and took more than a decade to recover. By 2017 the local economy was again performing well.

Annalistic references

SeeAnnals of Inisfallen

Annals ( la, annāles, from , "year") are a concise historical record in which events are arranged chronologically, year by year, although the term is also used loosely for any historical record.

Scope

The nature of the distinction between ann ...

(AI)

* ''AI927.2 A slaughter of the foreigners of Port Láirge as inflicted

As, AS, A. S., A/S or similar may refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* A. S. Byatt (born 1936), English critic, novelist, poet and short story writer

* As (song), "As" (song), by Stevie Wonder

* , a Spanish sports newspaper

* , an academic ...

at Cell Mo-Chellóc by the men of Mumu and by the foreigners of Luimnech.''

* ''AI930.1 Kl. A naval encampment ade

Ade, Adé, or ADE may refer to:

Aeronautics

*Ada Air's ICAO code

*Aden International Airport's IATA code

*Aeronautical Development Establishment, a laboratory of the DRDO in India

Medical

* Adverse Drug Event

*Antibody-dependent enhancement

*ADE ...

by the foreigners of Luimnech at Loch Bethrach in Osraige

Osraige (Old Irish) or Osraighe (Classical Irish), Osraí (Modern Irish), anglicized as Ossory, was a medieval Irish kingdom comprising what is now County Kilkenny and western County Laois, corresponding to the Diocese of Ossory. The home of t ...