Kuwait

Kuwait (; ar, الكويت ', or ), officially the State of Kuwait ( ar, دولة الكويت '), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated in the northern edge of Eastern Arabia at the tip of the Persian Gulf, bordering Iraq to the nort ...

is a sovereign state in

Western Asia

Western Asia, West Asia, or Southwest Asia, is the westernmost subregion of the larger geographical region of Asia, as defined by some academics, UN bodies and other institutions. It is almost entirely a part of the Middle East, and includes Ana ...

located at the head of the

Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

. The geographical region of Kuwait has been occupied by humans since antiquity, particularly due to its strategic location at the head of the Persian Gulf.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Kuwait was a prosperous maritime port city and the most important trade port in the northern Gulf region.

In the modern era, Kuwait is best known for the

Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a Coalition of the Gulf War, 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Ba'athist Iraq, ...

(1990–1991).

Antiquity

Mesopotamia

Following the post-glacial flooding of the Persian Gulf basin, debris from the

Tigris–Euphrates river formed a substantial delta, creating most of the land in present-day Kuwait and establishing the present coastlines.

One of the earliest evidence of human habitation in Kuwait dates back to 8000 BC where

Mesolithic tools were found in

Burgan.

During the

Ubaid period

The Ubaid period (c. 6500–3700 BC) is a prehistoric period of Mesopotamia. The name derives from Tell al-'Ubaid where the earliest large excavation of Ubaid period material was conducted initially in 1919 by Henry Hall and later by Leonard Wo ...

(6500 BC), Kuwait was the central site of interaction between the peoples of

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

and Neolithic

Eastern Arabia

Eastern Arabia, historically known as al-Baḥrayn ( ar, البحرين) until the 18th century, is a region stretched from Basra to Khasab along the Persian Gulf coast and included parts of modern-day Bahrain, Kuwait, Eastern Saudi Arabia, Unite ...

,

including

Bahra 1 and

site H3 in

Subiya.

The Neolithic inhabitants of Kuwait were among the world's earliest maritime traders.

One of the world's earliest reed-boats was discovered at

site H3 dating back to the Ubaid period.

Other Neolithic sites in Kuwait are located in Khiran and

Sulaibikhat.

s first settled in the Kuwaiti island of

Failaka

Failaka Island ( ar, فيلكا '' / ''; Kuwaiti Arabic: فيلچا ) is a Kuwaiti Island in the Persian Gulf. The island is 20 km off the coast of Kuwait City in the Persian Gulf. The name "Failaka" is thought to be derived from the ancie ...

in 2000 B.C.

[ Traders from the Sumerian city of Ur inhabited Failaka and ran a mercantile business.][ The island had many Mesopotamian-style buildings typical of those found in ]Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to the north, Iran to the east, the Persian Gulf and K ...

dating from around 2000 B.C. In 4000 BC until 2000 BC, the

In 4000 BC until 2000 BC, the bay of Kuwait

Jōn al Kuwayt ( ar, جون الكويت, Gulf Arabic pronunciation: /d͡ʒoːn‿ɪlkweːt/), also known as Kuwait Bay, is a bay in Kuwait. It is the head of the Persian Gulf. Kuwait City lies on a tip of the bay.

History

Following the post-glac ...

was home to the Dilmun civilization

Dilmun, or Telmun, ( Sumerian: , later 𒉌𒌇(𒆠), ni.tukki = DILMUNki; ar, دلمون) was an ancient East Semitic-speaking civilization in Eastern Arabia mentioned from the 3rd millennium BC onwards.

Based on contextual evidence, it was ...

.[ Umm an Namil,][ and ]Failaka

Failaka Island ( ar, فيلكا '' / ''; Kuwaiti Arabic: فيلچا ) is a Kuwaiti Island in the Persian Gulf. The island is 20 km off the coast of Kuwait City in the Persian Gulf. The name "Failaka" is thought to be derived from the ancie ...

.[ Dilmun first appears in Sumerian ]cuneiform

Cuneiform is a logo-syllabic script that was used to write several languages of the Ancient Middle East. The script was in active use from the early Bronze Age until the beginning of the Common Era. It is named for the characteristic wedge-sh ...

clay tablets dated to the end of fourth millennium BC, found in the temple of goddess Inanna in the city of Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.Harm ...

. The adjective Dilmun is used to describe a type of axe and one specific official; in addition there are lists of rations of wool issued to people connected with Dilmun.

Dilmun was mentioned in two letters dated to the reign of Burna-Buriash II

Burna-Buriaš II, rendered in cuneiform as ''Bur-na-'' or ''Bur-ra-Bu-ri-ia-aš'' in royal inscriptions and letters, and meaning ''servant'' or ''protégé of the Lord of the lands'' in the Kassite language, where Buriaš (, dbu-ri-ia-aš₂) is a ...

(c. 1370 BC) recovered from Nippur, during the Kassite

The Kassites () were people of the ancient Near East, who controlled Babylonia after the fall of the Old Babylonian Empire c. 1531 BC and until c. 1155 BC (short chronology).

They gained control of Babylonia after the Hittite sack of Babylon ...

dynasty of Babylon. These letters were from a provincial official, Ilī-ippašra, in Dilmun to his friend Enlil-kidinni in Mesopotamia. The names referred to are Akkadian.

There is both literary and archaeological evidence of extensive trade between ancient Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley civilization (probably correctly identified with the land called ''Meluhha

or ( sux, ) is the Sumerian language, Sumerian name of a prominent trading partner of Sumer during the Middle Bronze Age. Its identification remains an open question, but most scholars associate it with the Indus Valley civilisation.

Etymolo ...

'' in Akkadian). Impressions of clay seals from the Indus Valley city of Harappa were evidently used to seal bundles of merchandise, as clay seal impressions with cord or sack marks on the reverse side testify. A number of these Indus Valley seals have turned up at Ur and other Mesopotamian sites.

The "Persian Gulf" types of circular, stamped (rather than rolled) seals known from Dilmun, that appear at Lothal

Lothal () was one of the southernmost sites of the ancient Indus Valley civilisation, located in the Bhāl region of the modern state of Gujarāt. Construction of the city is believed to have begun around 2200 BCE.

Archaeological Survey of ...

in Gujarat

Gujarat (, ) is a state along the western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the fifth-largest Indian state by area, covering some ; and the ninth ...

, India, and Failaka, as well as in central Mesopotamia, are convincing corroboration of the long-distance sea trade. What the commerce consisted of is less known: timber and precious woods, ivory, lapis lazuli, gold, and luxury goods such as carnelian and glazed stone beads, pearls from the Persian Gulf, shell and bone inlays, were among the goods sent to Mesopotamia in exchange for silver, tin, woolen textiles, olive oil and grains. Copper ingots from Oman and bitumen which occurred naturally in Mesopotamia may have been exchanged for cotton textiles and domestic fowl, major products of the Indus region that are not native to Mesopotamia. Instances of all of these trade goods have been found. The importance of this trade is shown by the fact that the weights and measures used at Dilmun were in fact identical to those used by the Indus, and were not those used in Southern Mesopotamia.

Mesopotamian trade documents, lists of goods, and official inscriptions mentioning Meluhha supplement Harappan seals and archaeological finds. Literary references to Meluhhan trade date from the Akkadian Empire, the Third Dynasty of Ur

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC ( middle chronology) Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider t ...

, and Isin-Larsa

Larsa ( Sumerian logogram: UD.UNUGKI, read ''Larsamki''), also referred to as Larancha/Laranchon (Gk. Λαραγχων) by Berossos and connected with the biblical Ellasar, was an important city-state of ancient Sumer, the center of the cult ...

Periods (c. 2350–1800 BC), but the trade probably started in the Early Dynastic Period (c. 2600 BC). Some Meluhhan vessels may have sailed directly to Mesopotamian ports, but by the Isin-Larsa Period, Dilmun monopolized the trade.

In the Mesopotamian epic poem ''

In the Mesopotamian epic poem ''Epic of Gilgamesh

The ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' () is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and is regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature and the second oldest religious text, after the Pyramid Texts. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with ...

'', Gilgamesh

sux, , label=none

, image = Hero lion Dur-Sharrukin Louvre AO19862.jpg

, alt =

, caption = Possible representation of Gilgamesh as Master of Animals, grasping a lion in his left arm and snake in his right hand, in an Assy ...

had to pass through Mount Mashu

Mashu, as described in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh'' of Mesopotamian mythology, is a great cedar mountain through which the hero-king Gilgamesh passes via a tunnel on his journey to Dilmun after leaving the Cedar Forest, a forest of ten thousand lea ...

to reach Dilmun, Mount Mashu is usually identified with the whole of the parallel Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

and Anti-Lebanon

The Anti-Lebanon Mountains ( ar, جبال لبنان الشرقية, Jibāl Lubnān ash-Sharqiyyah, Eastern Mountains of Lebanon; Lebanese Arabic: , , "Eastern Mountains") are a southwest–northeast-trending mountain range that forms most of ...

ranges, with the narrow gap between these mountains constituting the tunnel.Sumerian creation myth

The earliest record of a Sumerian creation myth, called The Eridu Genesis by historian Thorkild Jacobsen, is found on a single fragmentary tablet excavated in Nippur by the Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania in 1893, and first recognized ...

, and the place where the deified Sumerian hero of the flood, Utnapishtim

Ut-napishtim or Uta-na’ishtim (in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''), Atra-Hasis, Ziusudra ( Sumerian), Xisuthros (''Ξίσουθρος'', in Berossus) ( akk, ) is a character in ancient Mesopotamian mythology. He is tasked by the god Enki (Akkadian: ...

(Ziusudra

Ziusudra ( Old Babylonian: , Neo-Assyrian: , grc-gre, Ξίσουθρος, Xísouthros) of Shuruppak (c. 2900 BC) is listed in the WB-62 Sumerian King List recension as the last king of Sumer prior to the Great Flood. He is subsequently r ...

), was taken by the gods to live forever. Thorkild Jacobsen

Thorkild Peter Rudolph Jacobsen (; 7 June 1904 – 2 May 1993) was a renowned Danish historian specializing in Assyriology and Sumerian literature. He was one of the foremost scholars on the ancient Near East.

Biography

Thorkild Peter Rudolph Ja ...

's translation of the Eridu Genesis calls it ''"Mount Dilmun"'' which he locates as a ''"faraway, half-mythical place"''.Ninhursag

, deity_of=Mother goddess, goddess of fertility, mountains, and rulers

, image= Mesopotamian - Cylinder Seal - Walters 42564 - Impression.jpg

, caption= Akkadian cylinder seal impression depicting a vegetation goddess, possibly Ninhursag, sittin ...

as the site at which the Creation occurred. The promise of Enki to Ninhursag, the Earth Mother: For Dilmun, the land of my lady's heart, I will create long waterways, rivers and canals,

whereby water will flow to quench the thirst of all beings and bring abundance to all that lives.

The Sumerian goddess of air and wind Ninlil

Ninlil ( DINGIR, DNIN (cuneiform), NIN.LÍL; meaning uncertain) was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of Enlil. She shared many of his functions, especially the responsibility for declaring destinies, and like him was regarded as a senio ...

had her home in Dilmun. It is also featured in the ''Epic of Gilgamesh''. However, in the early epic ''Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta

''Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta'' is a legendary Sumerian account, preserved in early post-Sumerian copies, composed in the Neo-Sumerian period (ca. 21st century BC).

It is one of a series of accounts describing the conflicts between Enmerkar, ...

'', the main events, which center on Enmerkar

Enmerkar was an ancient Sumerian ruler to whom the construction of Uruk and a 420-year reign was attributed. According to literary sources, he led various campaigns against the land of Aratta.

Historical king

Late Uruk period

The tradition ...

's construction of the ziggurat

A ziggurat (; Cuneiform: 𒅆𒂍𒉪, Akkadian: ', D-stem of ' 'to protrude, to build high', cognate with other Semitic languages like Hebrew ''zaqar'' (זָקַר) 'protrude') is a type of massive structure built in ancient Mesopotamia. It has ...

s in Uruk

Uruk, also known as Warka or Warkah, was an ancient city of Sumer (and later of Babylonia) situated east of the present bed of the Euphrates River on the dried-up ancient channel of the Euphrates east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.Harm ...

and Eridu

Eridu (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , NUN.KI/eridugki; Akkadian language, Akkadian: ''irîtu''; modern Arabic language, Arabic: Tell Abu Shahrain) is an archaeological site in southern Mesopotamia (modern Dhi Qar Governorate, Iraq). Eridu was l ...

, are described as taking place in a world "before Dilmun had yet been settled".

From about 1650 BC there is a further inscription on a seal found at Failaka and preserving a king's name. The short text readsː '' aù-la Panipa, daughter of Sumu-lěl, the servant of Inzak

Inzak (also Enzag, Enzak, Anzak; in older publications Enshag) was the main god of the pantheon of Dilmun. The precise origin of his name remains a matter of scholarly debate. He might have been associated with date palms. His cult center was Ag ...

of Akarum''. Sumu-lěl was evidently a third king of Dilmun belonging to about this period. ''Servant of Inzak of Akarum'' was the king's title in Dilmun. The names of these later rulers are Amoritic.

Despite the scholarly consensus that ancient Dilmun encompasses three modern locations - the eastern littoral of Arabia from the vicinity of modern Kuwait to Bahrain; the island of Bahrain; the island of Failaka of Kuwait - few researchers have taken into account the radically different geography of the basin represented by the Persian Gulf before its reflooding as sea levels rose about 6000 BCE. During the Dilmun era (from ca. 3000 BC), Failaka was known as " Agarum", the land of Enzak

Inzak (also Enzag, Enzak, Anzak; in older publications Enshag) was the main god of the pantheon of Dilmun. The precise origin of his name remains a matter of scholarly debate. He might have been associated with date palms. His cult center was Ag ...

, a great god in the Dilmun civilization according to Sumerian cuneiform texts found on the island.[ During the Neo-Babylonian Period, Enzak was identified with ]Nabu

Nabu ( akk, cuneiform: 𒀭𒀝 Nabû syr, ܢܵܒܼܘܼ\ܢܒܼܘܿ\ܢܵܒܼܘܿ Nāvū or Nvō or Nāvō) is the ancient Mesopotamian patron god of literacy, the rational arts, scribes, and wisdom.

Etymology and meaning

The Akkadian "nab ...

, the ancient Mesopotamian patron god of literacy, the rational arts, scribes and wisdom. As part of Dilmun, Failaka became a hub for the civilization from the end of the 3rd to the middle of the 1st millennium BC.[ Failaka was settled following 2000 BC after a drop in sea level.

After the Dilmun civilization, Failaka was inhabited by the Kassites of ]Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

,[ Studies indicate traces of human settlement can be found on Failaka dating back to as early as the end of the 3rd millennium BC, and extending until the 20th century AD.]Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; grc-gre, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου, ''Antiókheia hē epì Oróntou'', Learned ; also Syrian Antioch) grc-koi, Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπὶ Ὀρόντου; or Ἀντιόχεια ἡ ἐπ� ...

.

Under Nebuchadnezzar II, the bay of Kuwait was under Babylonian control. Cuneiform documents found in Failaka indicate the presence of Babylonians in the island's population. Babylonian Kings

The king of Babylon (Akkadian: ''šakkanakki Bābili'', later also ''šar Bābili'') was the ruler of the ancient Mesopotamian city of Babylon and its kingdom, Babylonia, which existed as an independent realm from the 19th century BC to its fall ...

were present in Failaka during the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC and bei ...

period, Nabonidus had a governor in Failaka and Nebuchadnezzar II had a palace and temple in Falaika.[

Most of present-day Kuwait is still archaeologically unexplored.][ Although there is no scholarly consensus, several famous archaeologists and geologists have proposed that Kuwait was likely the original location of the Pishon River which watered the Garden of Eden.][The Pishon River - Found](_blank)

/ref>[James K. Hoffmeier, ''The Archaeology of the Bible'', Lion Hudson: Oxford, England, 34-35] Juris Zarins argued that the Garden of Eden was situated at the head of the Persian Gulf (present-day Kuwait), where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers run into the sea, from his research on this area using information from many different sources, including LANDSAT

The Landsat program is the longest-running enterprise for acquisition of satellite imagery of Earth. It is a joint NASA / USGS program. On 23 July 1972, the Earth Resources Technology Satellite was launched. This was eventually renamed to La ...

images from space. His suggestion about the Pishon River was supported by James A. Sauer of the American Center of Oriental Research.Farouk El-Baz

Farouk El-Baz ( arz, فاروق الباز, ''Pronunciation'': ) (born January 2, 1938) is an Egyptian American space scientist and geologist, who worked with NASA in the scientific exploration of the Moon and the planning of the Apollo program. ...

traced the dry channel from Kuwait up the Wadi Al-Batin.

Ancient Greece

After an apparent abandonment of about seven centuries, the bay of Kuwait was repopulated during the

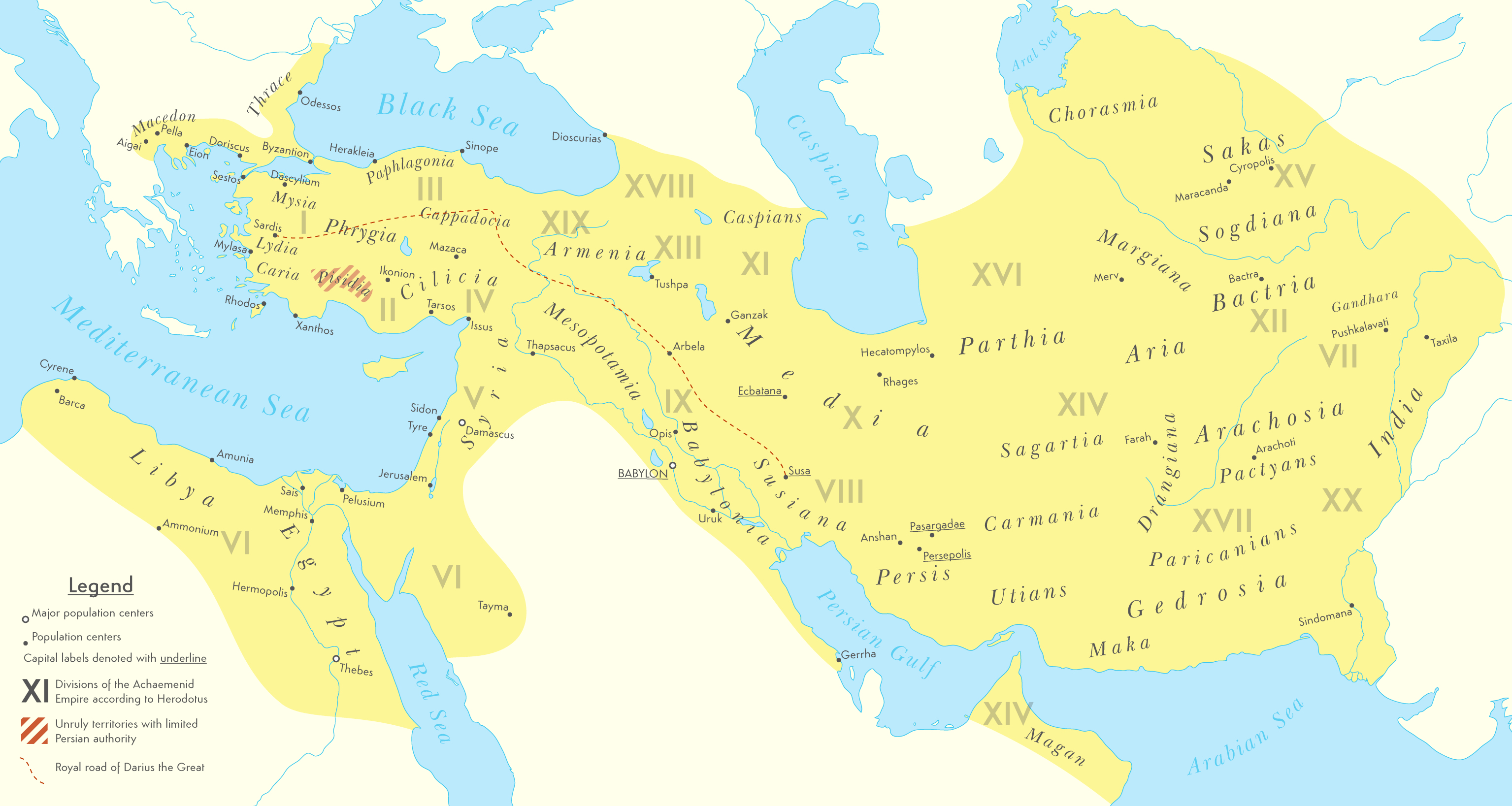

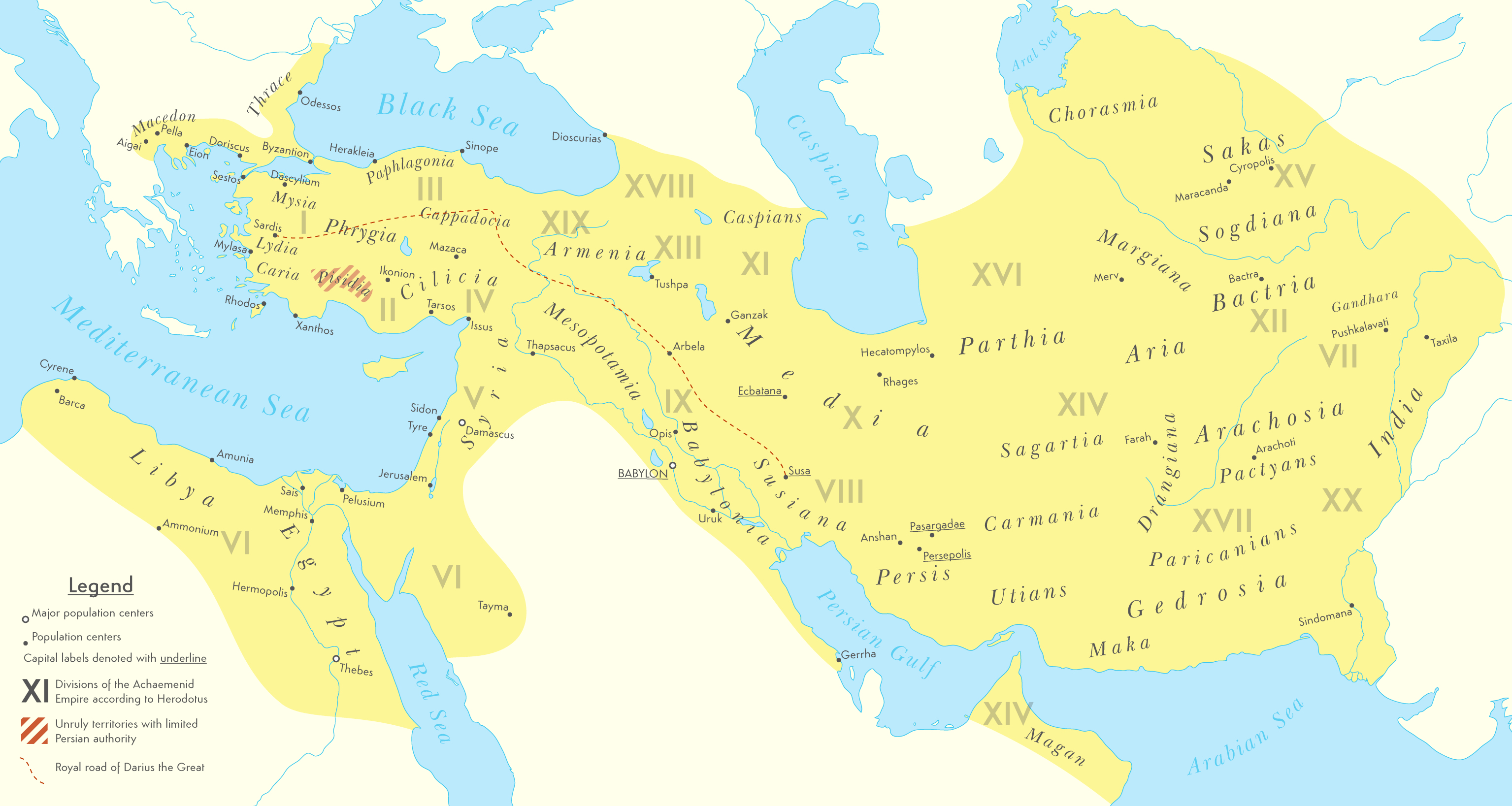

After an apparent abandonment of about seven centuries, the bay of Kuwait was repopulated during the Achaemenid period

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

(c. 550‒330 BC).ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

colonized the bay of Kuwait under Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

, the ancient Greeks named mainland Kuwait ''Larissa'' and Failaka was named '' Ikaros''.

According to Strabo and Arrian, Alexander the Great named Failaka ''Ikaros'' because it resembled the Aegean island of that name in size and shape. Various elements of Greek mythology

A major branch of classical mythology, Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the ancient Greeks, and a genre of Ancient Greek folklore. These stories concern the origin and nature of the world, the lives and activities ...

were mixed with the local cults in Failaka. "Ikaros" was also the name of a prominent city situated in Failaka.

According to another account, having returned from his Indian campaign to Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Alexander the Great ordered the island to be called Icarus, after the Icarus island in the Aegean Sea.Hellenization

Hellenization (other British spelling Hellenisation) or Hellenism is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonization often led to the Hellenization of indigenous peoples; in the H ...

of the local name Akar (Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

'KR), derived from the ancient bronze-age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second prin ...

toponym Agarum. Another suggestion is that the name Ikaros was influenced by the local É-kara temple, dedicated to the Babylonian sun-god Shamash. That both Failaka and the Aegean Icarus housed bull cults would have made the identification tempting all the more.

During Hellenistic times, there was a temple of Artemis

In ancient Greek mythology and religion, Artemis (; grc-gre, Ἄρτεμις) is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, care of children, and chastity. She was heavily identified wit ...

on the island.[Arrian, Anabasis of Alexander, §7.20](_blank)

/ref> The wild animals on the island were dedicated to goddess and no one should harm them.Apollo

Apollo, grc, Ἀπόλλωνος, Apóllōnos, label=genitive , ; , grc-dor, Ἀπέλλων, Apéllōn, ; grc, Ἀπείλων, Apeílōn, label= Arcadocypriot Greek, ; grc-aeo, Ἄπλουν, Áploun, la, Apollō, la, Apollinis, label ...

and an oracle of Artemis (Tauropolus) (μαντεῖον Ταυροπόλου). The island is also mentioned by Stephanus of Byzantium and Ptolemaeus

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

.

Remains of the settlement include a large Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

fort

A fortification is a military construction or building designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is also used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from Latin ''fortis'' ("strong") and ''facere'' ...

and two Greek temple

Greek temples ( grc, ναός, naós, dwelling, semantically distinct from Latin , "temple") were structures built to house deity statues within Greek sanctuaries in ancient Greek religion. The temple interiors did not serve as meeting places, s ...

s. Failaka was also a trading post ( emporion) of the kingdom of Characene

Characene (Ancient Greek: Χαρακηνή), also known as Mesene (Μεσσήνη) or Meshan, was a kingdom founded by the Iranian Hyspaosines located at the head of the Persian Gulf mostly within modern day Iraq. Its capital, Charax Spasinou (� ...

.[ Archaeological remains of Greek colonization were also discovered in Akkaz, Umm an Namil, and Subiya.][ At the Hellenistic fortress in Failaka, ]pigs

The pig (''Sus domesticus''), often called swine, hog, or domestic pig when distinguishing from other members of the genus '' Sus'', is an omnivorous, domesticated, even-toed, hoofed mammal. It is variously considered a subspecies of ''Sus ...

represented 20 percent of the total population, but no pig remains were found in nearby Akkaz.

Nearchos

Nearchus or Nearchos ( el, Νέαρχος; – 300 BC) was one of the Greeks, Greek officers, a navarch, in the army of Alexander the Great. He is known for his celebrated expeditionary voyage starting from the Indus river, Indus River, through t ...

was likely the first Greek to have explored Failaka.[ Failaka might have been fortified and settled during the days of ]Seleucus I

Seleucus I Nicator (; ; grc-gre, Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ , ) was a Macedonian Greek general who was an officer and successor ( ''diadochus'') of Alexander the Great. Seleucus was the founder of the eponymous Seleucid Empire. In the pow ...

or Antiochos I.[

At the time of Alexander the Great, the mouth of the Euphrates River was located in northern Kuwait.][ The Euphrates river flowed directly into the Persian Gulf via Khor Subiya which was a river channel at the time.][ By the first century BC, the Khor Subiya river channel dried out completely.][

]

Ancient Iran

During the

During the Achaemenid period

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

(c. 550‒330 BC), the bay of Kuwait was repopulated.[ Failaka was under the control of the Achaemenid Empire as evidenced by the archaeological discovery of Achaemenid strata.][ There are ]Aramaic

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated in ...

inscriptions that testify Achaemenid presence.[

In 127 BC, Kuwait was part of the ]Parthian Empire

The Parthian Empire (), also known as the Arsacid Empire (), was a major Iranian political and cultural power in ancient Iran from 247 BC to 224 AD. Its latter name comes from its founder, Arsaces I, who led the Parni tribe in conque ...

and the kingdom of Characene

Characene (Ancient Greek: Χαρακηνή), also known as Mesene (Μεσσήνη) or Meshan, was a kingdom founded by the Iranian Hyspaosines located at the head of the Persian Gulf mostly within modern day Iraq. Its capital, Charax Spasinou (� ...

was established around Teredon

Teredon was an ancient port city in southern Mesopotamia. The place could not be localized so far archaeologically, but is believed to be in Kuwait near Basra. The place is mentioned several times by ancient writers. It is said to have been founded ...

in present-day Kuwait.Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, an ...

'' by Greek scholar Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importance ...

.[

In 224 AD, Kuwait became part of the Sassanid Empire. At the time of the Sassanid Empire, Kuwait was known as ''Meshan'', which was an alternative name of the kingdom of Characene.

Late Sassanian settlements were discovered in Failaka.]Sassanian

The Sasanian () or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians (, ) and also referred to by historians as the Neo-Persian Empire, was the last Iranian empire before the early Muslim conquests of the 7th-8th centuries AD. Named ...

site;[ the Sassanid religion's ]tower of silence

A ''dakhma'' ( fa, دخمه), also known as a Tower of Silence, is a circular, raised structure built by Zoroastrians for excarnation (that is, the exposure of human corpses to the elements for decomposition), in order to avert contamina ...

was discovered in northern Akkaz.Bubiyan

Bubiyan Island ( ar, جزيرة بوبيان) is the largest island in the Kuwaiti coastal island chain situated in the north-western corner of the Persian Gulf, with an area of . Bubiyan Island is part of the Shatt al-Arab delta. The Mubarak A ...

, there is archaeological evidence of Sassanian periods of human presence as evidenced by the recent discovery of torpedo-jar pottery sherds on several prominent beach ridges.Kazma

Kazma () is an ancient city in Kuwait. It is located in Al Jahra Governorate, north of Kuwait City, the capital of Kuwait. It is an ancient city with a long history, known to Persians and Arabs since the Sassanid, Jahiliyyah and the early Isla ...

.[ At the time, Kuwait was under the control of the Sassanid Empire.][ The Battle of Chains was the first battle of the Rashidun Caliphate in which the Muslim army sought to extend its frontiers.

]

Early to late Islamic era

As a result of Rashidun victory in 636 AD, the bay of Kuwait was home to the city of Kazma

Kazma () is an ancient city in Kuwait. It is located in Al Jahra Governorate, north of Kuwait City, the capital of Kuwait. It is an ancient city with a long history, known to Persians and Arabs since the Sassanid, Jahiliyyah and the early Isla ...

(also known as "Kadhima" or "Kāzimah") in the early Islamic era.[ The city functioned as a trade port and resting place for pilgrims on their way from Iraq to Hejaz. The city was controlled by the kingdom of Al-Hirah in Iraq.][ In the early Islamic period, the bay of Kuwait was known for being a fertile area.]Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

and Mesopotamia en route to the Arabian Peninsula. The poet Al-Farazdaq was born in the Kuwaiti city of Kazma.[

Early to late Islamic settlements were discovered in Subiya, Akkaz, Kharaib al-Dasht, Umm al-Aish, Al-Rawdatain, Al Qusur, Umm an Namil, Miskan, and Kuwait's side of Wadi Al-Batin.]Bubiyan

Bubiyan Island ( ar, جزيرة بوبيان) is the largest island in the Kuwaiti coastal island chain situated in the north-western corner of the Persian Gulf, with an area of . Bubiyan Island is part of the Shatt al-Arab delta. The Mubarak A ...

.

Christian Nestorian

Christian Nestorian

Nestorianism is a term used in Christian theology and Church history to refer to several mutually related but doctrinarily distinct sets of teachings. The first meaning of the term is related to the original teachings of Christian theologian ...

settlements flourished in the bay of Kuwait from the 5th century until the 9th century.[ Excavations have revealed several farms, villages and two large churches dating from the 5th and 6th century.][ Archaeologists are currently excavating nearby sites to understand the extent of the settlements that flourished in the eighth and ninth centuries A.D.][ An old island tradition is that a community grew up around a Christian mystic and hermit.][ The small farms and villages were eventually abandoned.][ Parts of Kuwait came under the ]Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediter ...

. Remains of Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire primarily in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinopl ...

era Nestorian churches were found in Akkaz and Al-Qusur.[ Pottery at the Al-Qusur site can be dated from as early as the first half of the 7th century through the 9th century.

]

Founding of modern Kuwait (1613–1716)

In 1521, Kuwait was under Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

control. In the late 16th century, the Portuguese built a defensive settlement in Kuwait. In 1613, Kuwait City was founded as a fishing village

A fishing village is a village, usually located near a fishing ground, with an economy based on catching fish and harvesting seafood. The continents and islands around the world have coastlines totalling around 356,000 kilometres (221,000 ...

predominantly populated by fishermen. Administratively, it was a sheikhdom, ruled by local sheikhs from Bani Khalid clan.Bani Utbah

The Bani Utbah ( ar, بني عتبة, banī ʿUtbah, plural Utub; ar, العتوب ', singular Utbi; ar, العتبي ') is an Arab tribal confederation that originated in Najd. The confederation is thought to have been formed when a group of ...

settled in Kuwait City, which at this time was still inhabited by fishermen

A fisher or fisherman is someone who captures fish and other animals from a body of water, or gathers shellfish.

Worldwide, there are about 38 million commercial and subsistence fishers and fish farmers. Fishers may be professional or recreati ...

and primarily functioned as a fishing village under Bani Khalid control.[

]

Early growth (1716–1945)

Port city

In the eighteenth century, Kuwait prospered and rapidly became the principal commercial center for the transit of goods between India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Muscat

Muscat ( ar, مَسْقَط, ) is the capital and most populated city in Oman. It is the seat of the Governorate of Muscat. According to the National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI), the total population of Muscat Governorate was ...

, Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon. I ...

, and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plat ...

.[ During the Persian siege of Basra in 1775–1779, Iraqi merchants took refuge in Kuwait and were partly instrumental in the expansion of Kuwait's boat-building and trading activities.][

] Between the years 1775 and 1779, the Indian trade routes with Baghdad, Aleppo,

Between the years 1775 and 1779, the Indian trade routes with Baghdad, Aleppo, Smyrna

Smyrna ( ; grc, Σμύρνη, Smýrnē, or , ) was a Greek city located at a strategic point on the Aegean coast of Anatolia. Due to its advantageous port conditions, its ease of defence, and its good inland connections, Smyrna rose to promi ...

and Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth (Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya ( Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

were diverted to Kuwait.East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and South ...

was diverted to Kuwait in 1792.India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

and the east coasts of Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

.[ After the Persians withdrew from Basra in 1779, Kuwait continued to attract trade away from Basra.][

Regional geopolitical turbulence helped foster economic prosperity in Kuwait in the second half of the 18th century.]Ottoman government

The Ottoman Empire developed over the years as a despotism with the Sultan as the supreme ruler of a centralized government that had an effective control of its provinces, officials and inhabitants. Wealth and rank could be inherited but were j ...

persecution.boat building

Boat building is the design and construction of boats and their systems. This includes at a minimum a hull, with propulsion, mechanical, navigation, safety and other systems as a craft requires.

Construction materials and methods

Wood

Wo ...

in the Persian Gulf region. Kuwaiti ship vessels were renowned throughout the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by t ...

.sailor

A sailor, seaman, mariner, or seafarer is a person who works aboard a watercraft as part of its crew, and may work in any one of a number of different fields that are related to the operation and maintenance of a ship.

The profession of the s ...

s in the Persian Gulf.[ In the 19th century, Kuwait became significant in the horse trade,][ In the mid 19th century, it was estimated that Kuwait was exporting an average of 800 horses to India annually.][

During the reign of Mubarak, Kuwait was dubbed the " Marseilles of the Persian Gulf" because its economic vitality attracted a large variety of people.]Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

, and Armenians

Armenians ( hy, հայեր, '' hayer'' ) are an ethnic group native to the Armenian highlands of Western Asia. Armenians constitute the main population of Armenia and the ''de facto'' independent Artsakh. There is a wide-ranging diasp ...

.religious tolerance

Religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, mistaken, or harmful". ...

.typewriters

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selectively ...

and followed European culture

The culture of Europe is rooted in its art, architecture, film, different types of music, economics, literature, and philosophy. European culture is largely rooted in what is often referred to as its "common cultural heritage".

Definition ...

with curiosity. In the early 20th century, Kuwait immensely declined in regional economic importance,

In the early 20th century, Kuwait immensely declined in regional economic importance,World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

imposed a trade blockade against Kuwait because Kuwait's ruler supported the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. In 1937,

In 1937, Freya Stark

Dame Freya Madeline Stark (31 January 18939 May 1993), was a British-Italian explorer and travel writer. She wrote more than two dozen books on her travels in the Middle East and Afghanistan as well as several autobiographical works and essays ...

wrote about the extent of poverty in Kuwait at the time:

Merchants

Merchants had the most economic power in Kuwait before oil.[ The inauguration of the oil era freed the rulers from their financial dependency on merchant wealth.]

Al Sabahs

Al Sabah became Kuwait's dynastic monarchy in 1938.House of Sabah

The House of Sabah ( ar, آل صباح ''Āl Ṣubāḥ'') is the ruling family of Kuwait.

History Origin

The Al Sabah family originate from the Bani Utbah confederation. Prior to settling in Kuwait, the Al Sabah family were expelled from Umm ...

and other notable Kuwaiti families provided protection of city housed within Kuwait's wall. The man chosen was a Sabah, Sabah I bin Jaber

His Highness Sheikh Abu Salman Sabah I bin Jaber Al Sabah ( ar, أبو سلمان صباح بن جابر الصباح الأول) (c. 1700–1762) was the first ruler of the Sheikhdom of Kuwait. He was chosen by his community for the position of ...

. Sabah diplomacy may have also been important with neighbouring tribes, especially as Bani Khalid power declined. This selection is usually dated to 1752.Abdullah

Abdullah may refer to:

* Abdullah (name), a list of people with the given name or surname

* Abdullah, Kargı, Turkey, a village

* ''Abdullah'' (film), a 1980 Bollywood film directed by Sanjay Khan

* '' Abdullah: The Final Witness'', a 2015 Pakis ...

. Shortly before Sabah's death, in 1766, the al-Khalifa and, soon after, the al-Jalahima, left Kuwait en masse for Zubara

Zubarah ( ar, الزبارة), also referred to as Al Zubarah or Az Zubarah, is a ruined and ancient fort located on the north western coast of the Qatar peninsula in the Al Shamal municipality, about 105 km from the Qatari capital of Doha. ...

in Qatar. Domestically, the al-Khalifa and al-Jalahima had been among the top contenders for power. Their emigration left the Sabahs in undisputed control, and by the end of Abdullah I's long rule (1776-1814), Sabah rule was secure, and the political hierarchy in Kuwait was well established, the merchants deferring to direct orders from the Shaikh. By the 19th century, not only was the ruling Sabah much stronger than a desert Shaikh but also capable of naming his son successor. This influence was not just internal but enabled the al-Sabah to conduct foreign diplomacy. They soon established good relations with the British East India Company in 1775.

Assassination of Muhammad Bin Sabah

Although Kuwait was technically governed from Basra, the Kuwaitis had traditionally maintained a somewhat moderate degree of autonomous status.Shaikh

Sheikh (pronounced or ; ar, شيخ ' , mostly pronounced , plural ' )—also transliterated sheekh, sheyikh, shaykh, shayk, shekh, shaik and Shaikh, shak—is an honorific title in the Arabic language. It commonly designates a chief of a ...

Muhammad Al-Sabah

His Highness Mohammad Sabah Al-Salem Al-Sabah (; born 10 October 1955) is the former Deputy Prime Minister of Kuwait. The Emir of Kuwait HRH Sheikh Nawaf Al-Ahmad issued an Emiri Decree on Tuesday 19 July 2022 appointing him Prime Minister. On 2 ...

was assassinated by his half-brother, Mubarak, who, in early 1897, was recognized, by the Ottoman sultan, as the ''qaimmaqam'' (provincial sub-governor) of Kuwait.

Mubarak the Great

Mubarak's seizure of the throne via murder left his brother's former allies as a threat to his rule, especially as his opponents gained the backing of the Ottomans.

Mubarak's seizure of the throne via murder left his brother's former allies as a threat to his rule, especially as his opponents gained the backing of the Ottomans.gunboat

A gunboat is a naval watercraft designed for the express purpose of carrying one or more guns to bombard coastal targets, as opposed to those military craft designed for naval warfare, or for ferrying troops or supplies.

History Pre-ste ...

s along the Kuwaiti coast. Britain saw Mubarak's desire for an alliance as an opportunity to counteract German influence in the region and so agreed.Bahrain

Bahrain ( ; ; ar, البحرين, al-Bahrayn, locally ), officially the Kingdom of Bahrain, ' is an island country in Western Asia. It is situated on the Persian Gulf, and comprises a small archipelago made up of 50 natural islands and an ...

their main trade point, which negatively affected the Kuwaiti economy. However, Mubarak went to Bahrain and apologized for raising taxes and the three business men returned to Kuwait. In 1915, Mubarak the Great died and was succeeded by his son Jaber II Al-Sabah

Jaber II Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah, (1860 – 5 February 1917), was the eighth ruler of the Sheikhdom of Kuwait from the Al-Sabah dynasty. He was the eldest son of Mubarak Al-Sabah and is the ancestor of the Al-Jaber branch of the Al-Sabah family. H ...

, who reigned for just over one year until his death in early 1917. His brother Sheikh Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah succeeded him.

Anglo-Ottoman convention (1913)

In the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913

The Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, also known as the "Blue Line", was an agreement between the Sublime Porte of the Ottoman Empire and the Government of the United Kingdom which defined the limits of Ottoman jurisdiction in the area of the P ...

, the British concurred with the Ottoman Empire in defining Kuwait as an autonomous kaza

A kaza (, , , plural: , , ; ota, قضا, script=Arab, (; meaning 'borough')

* bg, околия (; meaning 'district'); also Кааза

* el, υποδιοίκησις () or (, which means 'borough' or 'municipality'); also ()

* lad, kaza

, ...

of the Ottoman Empire and that the Shaikhs of Kuwait were not independent leaders, but rather ''qaimmaqams'' (provincial sub-governors) of the Ottoman government.

The convention ruled that Sheikh Mubarak had authority over an area extending out to a radius of 80 km, from the capital. This region was marked by a red circle and included the islands of Auhah, Bubiyan

Bubiyan Island ( ar, جزيرة بوبيان) is the largest island in the Kuwaiti coastal island chain situated in the north-western corner of the Persian Gulf, with an area of . Bubiyan Island is part of the Shatt al-Arab delta. The Mubarak A ...

, Failaka, Kubbar, Mashian, and Warbah

Warbah Island ( ar, جزيرة وربة) is an island belonging to Kuwait, located in the Persian Gulf, near the mouth of the Euphrates River. It is located roughly east of the Kuwaiti mainland, north of Bubiyan Island, and south of the Iraqi ...

. A green circle designated an area extending out an additional 100 km, in radius, within which the ''qaimmaqam'' was authorized to collect tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of land which the state conqu ...

and taxes from the natives.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

disrupted elements of Kuwait's politics, society, economy and trans-regional networks.

Mesopotamian Campaign (1914)

On 6 November 1914, British offensive action began with the naval bombardment of the old fort at Fao

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)french: link=no, Organisation des Nations unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture; it, Organizzazione delle Nazioni Unite per l'Alimentazione e l'Agricoltura is an intern ...

in Iraq, located at the point where the Shatt-al-Arab

The Shatt al-Arab ( ar, شط العرب, lit=River of the Arabs; fa, اروندرود, Arvand Rud, lit=Swift River) is a river of some in length that is formed at the confluence of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers in the town of al-Qurnah in ...

meets the Persian Gulf. At the Fao Landing

The Fao Landing occurred from November 6, 1914 to November 8, 1914 with British forces attacking the Ottoman stronghold of Fao and its fortress. The landing was met with little resistance from the Turkish defenders who fled after intense shellin ...

, the British Indian Expeditionary Force D

The Indian Army during World War I was involved World War I. Over one million Indian troops served overseas, of whom 62,000 died and another 67,000 were wounded. In total at least 74,187 Indian soldiers died during the war.

In World War I the ...

(IEF D), comprising the 6th (Poona) Division

The 6th (Poona) Division was a division of the British Indian Army. It was formed in 1903, following the Kitchener reforms of the Indian Army.

World War I

The 6th (Poona) Division served in the Mesopotamian campaign. Led by Major General Barr ...

led by Lieutenant General Arthur Barrett with Sir Percy Cox

Major-General Sir Percy Zachariah Cox (20 November 1864 – 20 February 1937) was a British Indian Army officer and Colonial Office administrator in the Middle East. He was one of the major figures in the creation of the current Middle East.

...

as Political Officer, was opposed by 350 Ottoman troops and 4 guns. After a sharp engagement, the fort was overrun. By mid-November the Poona Division was fully ashore and began moving towards the city of Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

.

The same month, the ruler of Kuwait, Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah

Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah (1837 – 28 November 1915) ( ar, الشيخ مبارك بن صباح الصباح) "the Great" ( ar, مبارك الكبير) was the seventh ruler of the Sheikhdom of Kuwait from 18 May 1896 until his death on 18 Novem ...

, contributed to the Allied war effort by sending forces to attack Ottoman troops at Umm Qasr

Umm Qasr ( ar, أم قصر, also transliterated as ''Um-qasir'', ''Um-qasser, Um Qasr'') is a port city in southern Iraq. It stands on the canalised Khawr az-Zubayr, part of the Khawr Abd Allah estuary which leads to the Persian Gulf. It is se ...

, Safwan, Bubiyan

Bubiyan Island ( ar, جزيرة بوبيان) is the largest island in the Kuwaiti coastal island chain situated in the north-western corner of the Persian Gulf, with an area of . Bubiyan Island is part of the Shatt al-Arab delta. The Mubarak A ...

, and Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is han ...

. In exchange the British government recognised Kuwait as an "independent government under British protection."

Kuwait–Najd War (1919–21)

The Kuwait-Najd War erupted in the aftermath of World War I, when the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

was defeated and the British invalidated the Anglo-Ottoman Convention. The power vacuum, left by the fall of the Ottomans, sharpened the conflict between Kuwait and Najd (Ikhwan

The Ikhwan ( ar, الإخوان, al-ʾIkhwān, The Brethren), commonly known as Ikhwan min ta'a Allah ( ar, إخوان من أطاع الله), was a traditionalist religious militia made up of traditionally nomadic tribesmen which formed a signif ...

). The war resulted in sporadic border clashes throughout 1919–20.

Battle of Jahra

The Battle of Jahra

The Battle of Jahra was a battle during the Kuwait–Najd War, fought between Kuwaiti forces and Saudi-supported militants. The battle took place in Al-Jahra, west of Kuwait City on 10 October 1920 around the Kuwait Red Fort.

The battle

The ba ...

was a battle during the Kuwait-Najd War. The battle took place in Al Jahra

Al Jahra ( ar, الجهراء) is a town and city located west of the centre of Kuwait City in Kuwait. Al Jahra is the capital of the Al Jahra Governorate of Kuwait as well as the surrounding Al Jahra District which is agriculturally based. Ency ...

, west of Kuwait City on 10 October 1920 between Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah

Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah (; born 1864 – 23 February 1921) was the ninth ruler of the Sheikhdom of Kuwait.

He was the second son of Mubarak I and is the ancestor of the Al-Salim branch of the Al-Sabah family. He ruled from 5 February 1917 to ...

ruler of Kuwait and Ikhwan

The Ikhwan ( ar, الإخوان, al-ʾIkhwān, The Brethren), commonly known as Ikhwan min ta'a Allah ( ar, إخوان من أطاع الله), was a traditionalist religious militia made up of traditionally nomadic tribesmen which formed a signif ...

Wahhabi followers of Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia

Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman Al Saud ( ar, عبد العزيز بن عبد الرحمن آل سعود, ʿAbd al ʿAzīz bin ʿAbd ar Raḥman Āl Suʿūd; 15 January 1875Ibn Saud's birth year has been a source of debate. It is generally accepted ...

, king of Saudi Arabia.

A force of 4,000 Saudi Ikhwan, led by Faisal Al-Dawish

Faisal bin Sultan al-Duwaish (Arabic: فيصل بن سلطان .الدويش المطيري c. 1882 – 1931) was Prince of the Mutair tribe and one of Arabia's Ikhwan leaders, who assisted Abdulaziz in the unification of Saudi Arabia. The moth ...

, attacked the Kuwait Red Fort at Al-Jahra, defended by 2,000 Kuwaiti men. The Kuwaitis were largely outnumbered by the Ikhwan of Najd.

Sheikh Khaz'al turns down the throne of Kuwait

When Percy Cox

Major-General Sir Percy Zachariah Cox (20 November 1864 – 20 February 1937) was a British Indian Army officer and Colonial Office administrator in the Middle East. He was one of the major figures in the creation of the current Middle East.

...

was informed of the border clashes in Kuwait, he sent a letter to Mohammerah Sheikh Khazʽal Ibn Jabir

Khazal bin Jabir bin Merdaw al-Kabi ( ar, خزعل بن جابر بن مرداو الكعبي، fa, شیخ خزعل) (18 August 1863 – 24 May 1936), ''Muaz us-Sultana'', and ''Sardar-e- Aqdas'' (''Most Sacred Officer of the Imperial Order ...

offering the Kuwaiti throne to either him or one of his heirs, knowing that Khaz'al would be a wiser ruler than the Al Sabah family. Khaz'al, who considered the Al Sabah as his own family, replied "Do you expect me to allow the stepping down of Al Mubarak from the throne of Kuwait? Do you think I can accept this?"

The Uqair protocol

In response to tribal raids, the British High Commissioner in Baghdad, Percy Cox

Major-General Sir Percy Zachariah Cox (20 November 1864 – 20 February 1937) was a British Indian Army officer and Colonial Office administrator in the Middle East. He was one of the major figures in the creation of the current Middle East.

...

, imposed the Uqair Protocol of 1922

The Uqair Protocol or Uqair Convention was an agreement at Uqair on 2 December 1922 that defined the boundaries between Mandatory Iraq, the Sultanate of Nejd and Sheikhdom of Kuwait. It was imposed by Percy Cox, the British High Commissioner to I ...

which defined the boundaries between Iraq, Kuwait and Nejd. In April 1923, Shaikh Ahmad al-Sabah wrote the British Political Agent in Kuwait, Major John More, "I still do not know what the border between Iraq and Kuwait is, I shall be glad if you will kindly give me this information." More, upon learning that al-Sabah claimed the outer green line of the Anglo-Ottoman Convention (4 April), would relay the information to Sir Percy.

On 19 April, Sir Percy stated that the British government recognized the outer line of the convention as the border between Iraq and Kuwait. This decision limited Iraq's access to the Persian Gulf at 58 km of mostly marshy and swampy coastline. As this would make it difficult for Iraq to become a naval power (the territory did not include any deepwater harbours), the Iraqi King Faisal I

Faisal I bin Al-Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashemi ( ar, فيصل الأول بن الحسين بن علي الهاشمي, ''Faysal el-Evvel bin al-Ḥusayn bin Alī el-Hâşimî''; 20 May 1885 – 8 September 1933) was King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria ...

(whom the British installed as a puppet king in Iraq) did not agree to the plan. However, as his country was under British mandate, he had little say in the matter. Iraq and Kuwait would formally ratify the border in August. The border was re-recognized in 1932.

Attempts by Faisal I to build an Iraqi railway to Kuwait and port facilities on the Gulf were rejected by Britain. These and other similar British colonial policies made Kuwait a focus of the Arab national movement in Iraq, and a symbol of Iraqi humiliation at the hands of the British.

1930–1939: Iraq–Kuwait Reunification Movement

Throughout the 1930s, Kuwaiti people opposed the British imposed separation of Kuwait from Iraq.

In the 1930's, a popular movement emerged in Kuwait which called for the reunification of the country with Iraq.Free Kuwaiti Movement

Free may refer to:

Concept

* Freedom, having the ability to do something, without having to obey anyone/anything

* Freethought, a position that beliefs should be formed only on the basis of logic, reason, and empiricism

* Emancipate, to procure ...

in 1938, which was established by Kuwaiti youths who were opposed to British influence in the region. The movement submitted a petition to the Iraqi government demanding that it support the reunification of Kuwait and Iraq.[ Fearing that the movement would turn into an armed rebellion, the Al Sabah family agreed to the establishment of a legislative council to represent the Free Kuwaiti Movement and its political demands.]Ghazi of Iraq

Ghazi ibn Faisal ( ar, غازي ابن فيصل, Gâzî ibn-i Faysal) (21 March 1912 – 4 April 1939) was the King of Iraq from 1933 to 1939 having been briefly Crown Prince of the Kingdom of Syria in 1920. He was born in Mecca, the only son ...

publicly demanded that the prisoners be released and the Al Sabah family end their repressive policies towards members of the Free Kuwaiti Movement.[Batatu, Hanna 1978. "The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq's Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of its Communists, Ba'athists and Free Officers" Princeton p. 189]

Modern era

Independence and early state-building (1946–89)

Between 1946 and 1982, Kuwait experienced a period of prosperity driven by oil and its liberal atmosphere; this period is called the "golden era".constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

, Kuwait held its first parliamentary elections in 1963. Kuwait was the first Arab state in the Persian Gulf to establish a constitution and parliament.

Although Kuwait formally gained independence in 1961, Iraq initially refused to recognize the country's independence by maintaining that Kuwait is part of Iraq, albeit Iraq later briefly backed down following a show of force by Britain and Arab League support of Kuwait's independence.

Although Kuwait formally gained independence in 1961, Iraq initially refused to recognize the country's independence by maintaining that Kuwait is part of Iraq, albeit Iraq later briefly backed down following a show of force by Britain and Arab League support of Kuwait's independence.Operation Vantage

Operation Vantage was a British military operation in 1961 to support the newly independent state of Kuwait against territorial claims by its neighbour, Iraq. The UK reacted to a call for protection from Sheikh Abdullah III Al-Salim Al-Sabah of Kuw ...

crisis evolved in July 1961, as the Iraqi government threatened to invade Kuwait and the invasion was finally averted following plans by the Arab League to form an international Arab force against the potential Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. As a result of Operation Vantage, the Arab League took over the border security of Kuwait and the British had withdrawn their forces by 19 October.Abd al-Karim Qasim

Abd al-Karim Qasim Muhammad Bakr al-Fadhli al-Zubaidi ( ar, عبد الكريم قاسم ' ) (21 November 1914 – 9 February 1963) was an Iraqi Army brigadier and nationalist who came to power when the Iraqi monarchy was overthrown d ...

was killed in a coup in 1963 but, although Iraq recognised Kuwaiti independence and the military threat was perceived to be reduced, Britain continued to monitor the situation and kept forces available to protect Kuwait until 1971. There had been no Iraqi military action against Kuwait at the time: this was attributed to the political and military situation within Iraq which continued to be unstable.Kuwait-Iraq 1973 Sanita border skirmish

Following the deterring effect of Operation Vantage (1961), Kuwait gained its recognition by Iraq in 1963. Both countries had ongoing border disputes throughout most of the 1960s, although often resolved and restrained within the history of Arab ...

evolved on 20 March 1973, when Iraqi army units occupied El-Samitah near the Kuwaiti border, which evoked an international crisis.

On 6 February 1974, Palestinian militants occupied the Japanese embassy in Kuwait, taking the ambassador and ten others hostage. The militants' motive was to support the Japanese Red Army

The was a militant communist organization active from 1971 to 2001. It was designated a terrorist organization by Japan and the United States. The JRA was founded by Fusako Shigenobu and Tsuyoshi Okudaira in February 1971 and was most active i ...

members and Palestinian militants who were holding hostages on a Singaporean ferry in what is known as the ''Laju'' incident. Ultimately, the hostages were released, and the guerrillas allowed to fly to Aden. This was the first time Palestinian guerrillas struck in Kuwait as the Al Sabah ruling family, headed by Sheikh Sabah Al-Salim Al-Sabah, funded the Palestinian resistance movement. Kuwait had been a regular endpoint for Palestinian plane hijacking in the past and had considered itself safe.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Kuwait was the most developed country in the region.Kuwait Investment Authority

The Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) is Kuwait's sovereign wealth fund, managing the state’s reserve and the state’s future generation fund (FGF).

Founded in 1953, the KIA is the world's oldest sovereign wealth fund. As of April 2022, it ...

as the world's first sovereign wealth fund

A sovereign wealth fund (SWF), sovereign investment fund, or social wealth fund is a state-owned investment fund that invests in real and financial assets such as stocks, bonds, real estate, precious metals, or in alternative investments such as ...

. From the 1970s onward, Kuwait scored highest of all Arab countries on the Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the education system), and per capita income indicators, wh ...

,[ and ]Kuwait University

Kuwait University ( ar, جامعة الكويت, abbreviated as Kuniv) is a public university located in Kuwait City, Kuwait.

History

Kuwait University (KU), (in Arabic: جامعة الكويت), was established in October 1966 under Act N. 29 ...

, founded in 1966, attracted students from neighboring countries. Kuwait's theatre industry was renowned throughout the Arab world.[

At the time, Kuwait's press was described as one of the freest in the world.][ Additionally, Kuwait became a haven for writers and journalists in the region, and many, like the Iraqi poet Ahmed Matar, moved to Kuwait for its strong ]freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The right to freedom of expression has been recog ...

laws, which surpassed those of any other country in the region.economic crisis

An economy is an area of the production, distribution and trade, as well as consumption of goods and services. In general, it is defined as a social domain that emphasize the practices, discourses, and material expressions associated with th ...

after the Souk Al-Manakh stock market crash and decrease in oil price.

During the Iran–Iraq War

The Iran–Iraq War was an armed conflict between Iran and Ba'athist Iraq, Iraq that lasted from September 1980 to August 1988. It began with the Iraqi invasion of Iran and lasted for almost eight years, until the acceptance of United Nations S ...

, Kuwait supported Iraq. Throughout the 1980s, there were several terror attacks in Kuwait, including the 1983 Kuwait bombings

The 1983 Kuwait bombings were attacks on six key foreign and Kuwaiti installations on 12 December 1983, two months after the 1983 Beirut barracks bombing. The 90-minute coordinated attack on two embassies, the country's main airport, and petro-c ...

, hijacking of several Kuwait Airways planes and attempted assassination of Emir Jaber in 1985. Kuwait was a regional hub of science and technology in the 1960s and 1970s up until the early 1980s,[

In 1986, the constitution was again suspended, along with the National Assembly.]Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

's province of Basra, something that Iraq said made Kuwait rightful Iraqi territory.protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over most of its int ...

agreement in 1899 that assigned responsibility for Kuwait's foreign affairs to the United Kingdom. The UK drew the border between Kuwait and Iraq in 1922, making Iraq almost entirely landlocked by limiting its access to the Persian Gulf coastline. Kuwait rejected Iraq's attempts to secure further coastline provisions in the region.Rumaila oil field

The Rumaila oil field is a super-giant oil field located in southern Iraq, approximately from the Kuwaiti border. Discovered in 1953 by the Basrah Petroleum Company (BPC), an associate company of the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), the field is e ...

. At the same time, Saddam looked for closer ties with those Arab states that had supported Iraq in the war. This move was supported by the US, who believed that Iraqi ties with pro-Western Gulf states would help bring and maintain Iraq inside the US' sphere of influence.Umm Qasr

Umm Qasr ( ar, أم قصر, also transliterated as ''Um-qasir'', ''Um-qasser, Um Qasr'') is a port city in southern Iraq. It stands on the canalised Khawr az-Zubayr, part of the Khawr Abd Allah estuary which leads to the Persian Gulf. It is se ...

was rejected.The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and '' The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the ...

''. Following Saddam's declaration that "binary chemical weapons" would be used on Israel if it used military force against Iraq, Washington halted part of its funding.Israeli-occupied territories

Israeli-occupied territories are the lands that were captured and occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War of 1967. While the term is currently applied to the Palestinian territories and the Golan Heights, it has also been used to refer to a ...

, where riots had resulted in Palestinian deaths, was veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president or monarch vetoes a bill to stop it from becoming law. In many countries, veto powers are established in the country's constitution. Veto ...

ed by the US, making Iraq deeply skeptical of US foreign policy aims in the region, combined with the reliance of the US on Middle Eastern energy reserves.

Gulf War (1990–91)

Tensions increased further in summer 1990, after Iraq complained to OPEC claiming that Kuwait was stealing its oil from a field near the border by slant drilling of the Rumaila field

The Rumaila oil field is a super-giant oil field located in southern Iraq, approximately from the Kuwaiti border. Discovered in 1953 by the Basrah Petroleum Company (BPC), an associate company of the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), the field is e ...

.CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

reported that Iraq had moved 30,000 troops to the Iraq-Kuwait border, and the US naval fleet in the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf ( fa, خلیج فارس, translit=xalij-e fârs, lit=Gulf of Fars, ), sometimes called the ( ar, اَلْخَلِيْجُ ٱلْعَرَبِيُّ, Al-Khalīj al-ˁArabī), is a mediterranean sea in Western Asia. The bod ...

was placed on alert. Saddam believed an anti-Iraq conspiracy was developingKuwait had begun talks with Iran, and Iraq's rival Syria had arranged a visit to Egypt.aerial refuelling

Aerial refueling, also referred to as air refueling, in-flight refueling (IFR), air-to-air refueling (AAR), and tanking, is the process of transferring aviation fuel from one aircraft (the tanker) to another (the receiver) while both aircraft a ...

planes and combat ships to the Persian Gulf in response to these threats. Discussions in Jeddah mediated on the Arab League's behalf by Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak

Muhammad Hosni El Sayed Mubarak, (; 4 May 1928 – 25 February 2020) was an Egyptian politician and military officer who served as the fourth president of Egypt from 1981 to 2011.

Before he entered politics, Mubarak was a career officer in ...

, were held on 31 July and led Mubarak to believe that a peaceful course could be established.[Finlan (2003). pp. 25–26.]

On the 25th, Saddam met with April Glaspie

April Catherine Glaspie (born April 26, 1942) is an American former diplomat and senior member of the Foreign Service, best known for her role in the events leading up to the Gulf War.

Early life

Glaspie was born in Vancouver, British Columb ...

, the US Ambassador to Iraq, in Baghdad. The Iraqi leader attacked American policy with regards to Kuwait and the UAE:

Glaspie replied:

Saddam stated that he would attempt last-ditch negotiations with the Kuwaitis but Iraq "would not accept death". The invasion of Kuwait and annexation by Iraq took place on 2 August 1990. The initial casus belli was claimed to be support for a Kuwaiti rebellion against the Al Sabah family.

The invasion of Kuwait and annexation by Iraq took place on 2 August 1990. The initial casus belli was claimed to be support for a Kuwaiti rebellion against the Al Sabah family.[ The resistance predominantly consisted of ordinary citizens who lacked any form of training and supervision.]United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

, an American-led coalition of 34 nations fought the Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a Coalition of the Gulf War, 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Ba'athist Iraq, ...

to liberate Kuwait. Aerial bombardments began on 17 January 1991, and after several weeks a U.S.-led United Nations (UN) coalition began a ground assault on 23 February 1991 that achieved a complete removal of Iraqi forces from Kuwait in four days.

Controversies

=Oil spill

=

On 23 January 1991, Iraq dumped of crude oil into the Persian Gulf, causing the largest offshore oil spill in history at that time.

On 23 January 1991, Iraq dumped of crude oil into the Persian Gulf, causing the largest offshore oil spill in history at that time.

=Kuwaiti oil fires

=

The Kuwaiti oil fires were caused by the

The Kuwaiti oil fires were caused by the Iraqi military

The Iraqi Armed Forces ( ar, القوات المسلحة العراقية romanized: ''Al-Quwwat Al-Musallahah Al-Iraqiyyah'') ( Kurdish: هێزە چەکدارەکانی عێراق) are the military forces of the Republic of Iraq. They consist ...

setting fire to 700 oil wells as part of a scorched earth policy while retreating from Kuwait in 1991 after conquering the country but being driven out by coalition forces. The fires started in January and February 1991, and the last one was extinguished by November.

The resulting fires burned uncontrollably because of the dangers of sending in firefighting crews. Land mines

A land mine is an explosive device concealed under or on the ground and designed to destroy or disable enemy targets, ranging from combatants to vehicles and tanks, as they pass over or near it. Such a device is typically detonated automati ...

had been placed in areas around the oil wells, and a military cleaning of the areas was necessary before the fires could be put out. Somewhere around of oil were lost each day. Eventually, privately contracted crews extinguished the fires, at a total cost of US$1.5 billion to Kuwait. By that time, however, the fires had burned for approximately 10 months, causing widespread pollution in Kuwait.

The Kuwaiti Oil Minister estimated between twenty-five and fifty million barrels of unburned oil from damaged facilities pooled to create approximately 300 oil lakes, that contaminated around 40 million tons of sand and earth. The mixture of desert sand, unignited oil spilled and soot

Soot ( ) is a mass of impure carbon particles resulting from the incomplete combustion of hydrocarbons. It is more properly restricted to the product of the gas-phase combustion process but is commonly extended to include the residual pyrolysed ...

generated by the burning oil wells formed layers of hard "tarcrete", which covered nearly five percent of Kuwait's land mass.United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), formerly simply known as the Geological Survey, is a scientific agency of the United States government. The scientists of the USGS study the landscape of the United States, its natural resources, ...

Campbell, Robert Wellman, ed. 1999. ''Iraq and Kuwait: 1972, 1990, 1991, 1997.'' Earthshots: Satellite Images of Environmental Change. U.S. Geological Survey. http://earthshots.usgs.gov

, revised February 14, 1999.United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmoniz ...

''Updated Scientific Report on the Environmental Effects of the Conflict between Iraq and Kuwait''

March 8, 1993.

=Highway of Death

=

On the night of 26–27 February 1991, several Iraqi forces began leaving Kuwait on the main highway north of

On the night of 26–27 February 1991, several Iraqi forces began leaving Kuwait on the main highway north of Al Jahra

Al Jahra ( ar, الجهراء) is a town and city located west of the centre of Kuwait City in Kuwait. Al Jahra is the capital of the Al Jahra Governorate of Kuwait as well as the surrounding Al Jahra District which is agriculturally based. Ency ...

in a column of some 1,400 vehicles. A patrolling E-8 Joint STARS