History Of Japanese Americans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Japanese American history is the history of

Japanese American history is the history of

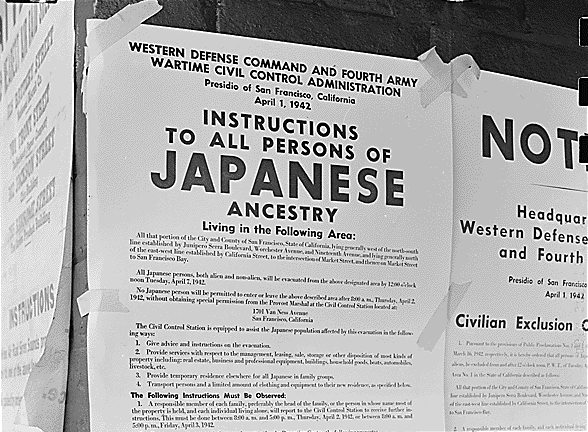

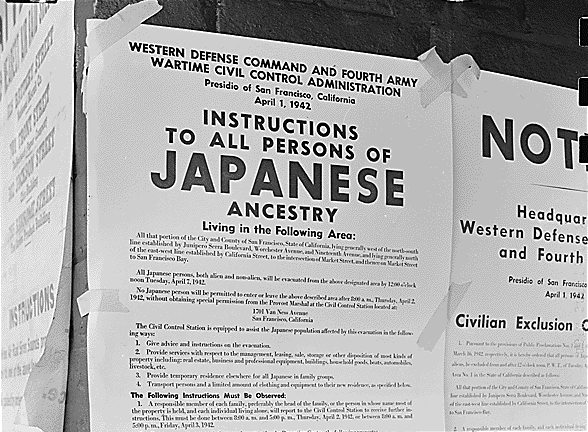

During World War II, an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals or citizens residing in the United States were forcibly

During World War II, an estimated 120,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals or citizens residing in the United States were forcibly

There is evidence to suggest that the first Japanese individual to land in North America was a young boy accompanying Franciscan friar, Martín Ignacio Loyola, in October 1587, on Loyola's second circumnavigation trip around the world.

There is evidence to suggest that the first Japanese individual to land in North America was a young boy accompanying Franciscan friar, Martín Ignacio Loyola, in October 1587, on Loyola's second circumnavigation trip around the world.

Text of the Immigration Act of 1907

online

24 articles by experts, mostly about California. * Chin, Frank. ''Born in the USA: A Story of Japanese America, 1889–1947'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002). * Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. ''Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians'' (Washington, GPO: 1982) * Conroy, Hilary, and Miyakawa T. Scott, eds. ''East Across the Pacific: Historical & Sociological Studies of Japanese Immigration & Assimilation'' (1972), essays by scholars * Daniels, Roger. ''Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850'' (U of Washington Press, 1988

online edition

* Daniels, Roger. ''Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II'' (1981). * Daniels, Roger. ''The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion'' (2nd ed. 1978) * Daniels, Roger, et al. eds. ''Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress'' (2nd ed. 1991) * Easton, Stanley E. and Lucien Ellington. "Japanese Americans." in ''Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America,'' edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 2, Gale, 2014, pp. 537–555

Online

* * Ichioka, Yuji. "Amerika Nadeshiko: Japanese Immigrant Women in the United States, 1900-1924," ''Pacific Historical Review'' Vol. 49, No. 2 (May, 1980), pp. 339–35

in JSTOR

* Ichioka, Yuji. "Japanese Associations and the Japanese Government: A Special Relationship, 1909–1926," ''Pacific Historical Review'' Vol. 46, No. 3 (Aug., 1977), pp. 409–43

in JSTOR

* Ichioka, Yuji. "Japanese Immigrant Response to the 1920 California Alien Land Law," ''Agricultural History'' Vol. 58, No. 2 (Apr., 1984), pp. 157–17

in JSTOR

* Matsumoto, Valerie J. ''Farming the Home Place: A Japanese American Community in California, 1919–1982'' (1993) * Modell John. ''The Economics and Politics of Racial Accommodation: The Japanese of Los Angeles, 1900–1942'' (1977) * Niiya, Brian, ed. ''Encyclopedia of Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present.'' (2001)

online free to borrow

* Takaki, Ronald. ''Strangers from a Different Shore'' (2nd ed. 1998) * Wakatsuki Yasuo. "Japanese Emigration to the United States, 1866–1924: A Monograph." ''Perspectives in American History'' 12 (1979): 387–516. {{DEFAULTSORT:Japanese American History Japanese American

Japanese American history is the history of

Japanese American history is the history of Japanese Americans

are Americans of Japanese ancestry. Japanese Americans were among the three largest Asian American ethnic communities during the 20th century; but, according to the 2000 census, they have declined in number to constitute the sixth largest Asi ...

or the history of ethnic Japanese in the United States. People from Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

began immigrating to the U.S. in significant numbers following the political, cultural, and social changes stemming from the 1868 Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

. Large-scale Japanese immigration started with immigration to Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

during the first year of the Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

in 1868.

Japanese American history before World War II

Immigration

There is evidence to suggest that the first Japanese individual to land in North America was a young boy accompanying Franciscan friar, Martín Ignacio Loyola, in October 1587, on Loyola's second circumnavigation trip around the world. Japanese castawayOguri Jukichi

was one of the first Japanese citizens known to have reached present day California. He and his fourteen-man crew, bound for Edo, were sailing off the Japanese coast in 1813 when their ship, the ''Tokujomaru'', was disabled in a storm. The ship ...

was among the first Japanese citizens known to have reached present day California (1815),Frank, Sarah., ''Filipinos in America''(Minnesota, 2005) while Otokichi

, also known as Yamamoto Otokichi and later known as John Matthew Ottoson (1818 – January 1867), was a Japanese castaway originally from the area of Onoura near modern-day Mihama, on the west coast of the Chita Peninsula in Aichi Prefecture ...

and two fellow castaways reached present day Washington state (1834).

Japan emerged from isolation following Commodore Matthew Perry's expedition to Japan, where he successfully negotiated a treaty opening Japan to American trade. Further developments included the start of direct shipping between San Francisco and Japan in 1855 and established official diplomatic relations in 1860.Kashima, T., ‘Nisei and Issei’, in. Personal Justice Denied (2nd ed, United States of America, 2000) p. 30

Japanese immigration to the United States was mostly economically motivated. Stagnating economic conditions causing poor living conditions and high unemployment pushed Japanese people to search elsewhere for a better life. Japan's population density had increased from 1,335 per square in 1872 to 1,885 in 1903 intensifying economic pressure on working class populations. Rumors of better standards of living in the “land of promise” encouraged a rise in immigration to the US, especially by younger sons who (due in large part to the Japanese practice of primogeniture

Primogeniture ( ) is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit the parent's entire or main estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relativ ...

) were motivated to independently establish themselves abroad. Only fifty-five Japanese were recorded as living in the United States in 1870, but by 1890 there had been more than two thousand new arrivals.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

had a significant impact for Japanese immigration, as it left room for 'cheap labor' and an increasing recruitment of Japanese from both Hawaii and Japan as they sought industrialists to replace Chinese laborers. 'Between 1901 and 1908, a time of unrestricted immigration, 127,000 Japanese entered the U.S.'Kashima, T., ‘Nisei and Issei’, in. Personal Justice Denied (2nd ed, United States of America, 2000)

The numbers of new arrivals peaked in 1907 with as many as 30,000 Japanese immigrants counted (economic and living conditions were particularly bad in Japan at this point as a result of the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

of 1904–5).Masakazu, Iwata,. ‘The Japanese Immigrants in California Agriculture’, agricultural history 36.1 (Jan 1996), pp. 25–37 Japanese immigrants who moved to mainland U.S. settled on the West Coast primarily in California.

Anti-Japanese sentiment

Nonetheless, there was a history of legalized discrimination in American immigration laws which heavily restricted Japanese immigration. As the number of Japanese in the United States increased, resentment against their success in the farming industry and fears of a "yellow peril

The Yellow Peril (also the Yellow Terror and the Yellow Specter) is a racist, racial color terminology for race, color metaphor that depicts the peoples of East Asia, East and Southeast Asia as an existential danger to the Western world. As a ...

" grew into an anti-Japanese movement similar to that faced by earlier Chinese immigrants.

Increased pressure from the Asiatic Exclusion League

The Asiatic Exclusion League (often abbreviated AEL) was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

United States

In May 1905, a mass meeting was he ...

and the San Francisco Board of Education

The San Francisco Board of Education is the school board for the San Francisco, City and County of San Francisco. It is composed of seven Commissioners, elected by voters across the city to serve 4-year terms. It is subject to local, state, and f ...

, forced President Roosevelt to negotiate the Gentlemen's Agreement

A gentlemen's agreement, or gentleman's agreement, is an informal and legally non-binding agreement between two or more parties. It is typically oral, but it may be written or simply understood as part of an unspoken agreement by convention or th ...

with Japan in 1907. It was agreed that Japan would stop issuing valid passports for the U.S. This agreement was intended to curtail Japanese immigration to the U.S, but Japanese women were still allowed to immigrate if they were the wives of U.S. residents. Prior to 1908, about seven out of eight ethnic Japanese in the United States were men. By 1924, the ratio had changed to approximately four women to every six men. Japanese immigration to the U.S. effectively ended when Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

which banned all but a token few Japanese people.

The ban on immigration produced unusually well-defined generational groups within the Japanese American community. Initially, there was an immigrant generation, the Issei

is a Japanese-language term used by ethnic Japanese in countries in North America and South America to specify the Japanese people who were the first generation to immigrate there. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are ...

, and their U.S.-born children, the Nisei Japanese American

During the early years of World War II, Japanese Americans were forcibly relocated from their homes in the West Coast because military leaders and public opinion combined to fan unproven fears of sabotage. As the war progressed, many of the ...

. The Issei were exclusively those who had immigrated before 1924. Because no new immigrants were permitted, all Japanese Americans born after 1924 were — by definition — born in the US. This generation, the Nisei, became a distinct cohort from the Issei generation in terms of age, citizenship, and English language ability, in addition to the usual generational differences. Institutional and interpersonal racism led many of the Nisei to marry other Nisei, resulting in a third distinct generation of Japanese Americans, the Sansei

is a Japanese and North American English term used in parts of the world such as South America and North America to specify the children of children born to ethnic Japanese in a new country of residence. The ''nisei'' are considered the second g ...

.Muller, E. L., The Hunt for Japanese American Disloyalty in World War II (North Carolina, 2007)

It was only in 1952 that the Senate and House voted the McCarran-Walter Act

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (), also known as the McCarran–Walter Act, codified under Title 8 of the United States Code (), governs immigration to and citizenship in the United States. It came into effect on June 27, 1952. Before ...

which allowed Japanese immigrants to become naturalized U.S. citizens. But significant Japanese immigration did not occur again until the Immigration Act of 1965

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, is a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The l ...

which ended 40 years of bans against immigration from Japan and other countries.

Farming

Japanese-Americans have made significant contributions to agricultural development in Western-Pacific parts of the United States. Similar toEuropean American

European Americans (also referred to as Euro-Americans) are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes people who are descended from the first European settlers in the United States as well as people who are descended from more recent Eu ...

settlers, the ''Issei

is a Japanese-language term used by ethnic Japanese in countries in North America and South America to specify the Japanese people who were the first generation to immigrate there. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are ...

'', the majority of whom were young adult males, immigrated to America searching for better economic conditions and the majority settled in Western Pacific states settling for manual labor jobs in various industries such as ‘railroad, cannery and logging camp laborers. The Japanese workforce were diligent and extremely hardworking, inspired to earn enough money to return and retire in Japan. Consequently, this collective ambition enabled the ''Issei'' to work in agriculture as tenant farmers fairly promptly and by ‘1909 approximately 30,000 Japanese laborers worked in the Californian agriculture’. This transition occurred relatively smoothly due to a strong inclination to work in agriculture which had always been an occupation that had been looked upon with respect in Japan.

Progress was made by the ''Issei'' in agriculture despite struggles faced cultivating the land, including harsh environment problems such as harsh weather and persistent issues with grass-hoppers. Economic difficulties and discriminating socio-political pressures such as the anti-alien laws (see California Alien Land Law of 1913

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 (also known as the Webb–Haney Act) prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it, but permitted leases lasting up to three years. It affe ...

) were further obstacles. Nevertheless, second-generation ''Nisei'' were not impacted by these laws as a result of being legal American citizens, therefore their important roles in West Coast agriculture persisted Japanese immigrants brought a sophisticated knowledge of cultivation including knowledge of soils, fertilizers, skills in land reclamation, irrigation and drainage. This knowledge combined with Japanese traditional culture respecting the soil and hard-work, led successful cultivation of crops on previously marginal lands. According to sources, by 1941 Japanese Americans ‘were producing between thirty and thirty-five per cent by value of all commercial truck crops grown in California as well as occupying a dominant position in the distribution system of fruits and vegetables.’

The role of ''Issei'' in agriculture prospered in the early twentieth century. It was only in the event of the Internment of Japanese Americans

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

in 1942 that many lost their agricultural businesses and farms. Although this was the case, Japanese Americans remain involved in these industries today, particularly in southern California

Southern California (commonly shortened to SoCal) is a geographic and Cultural area, cultural region that generally comprises the southern portion of the U.S. state of California. It includes the Los Angeles metropolitan area, the second most po ...

and to some extent, Arizona

Arizona ( ; nv, Hoozdo Hahoodzo ; ood, Alĭ ṣonak ) is a state in the Southwestern United States. It is the 6th largest and the 14th most populous of the 50 states. Its capital and largest city is Phoenix. Arizona is part of the Fou ...

by the areas' year-round agricultural economy, and descendants of Japanese pickers who adapted farming in Oregon and Washington state.Ingram, Scott,. Asher, Robert., 'Immigrants (Immigration To The United States)'(Nov 2004)

Agriculture also played a key role during the internment of Japanese Americans. World War II internment camps, were located in desolate spots such as Poston, in the Arizona desert, and Tule Lake

Tule Lake ( ) is an intermittent lake covering an area of , long and across, in northeastern Siskiyou County and northwestern Modoc County in California, along the border with Oregon.

Geography

Tule Lake is fed by the Lost River. The elevat ...

, California, at a dry mountain lake bed. Agricultural programs were put in place at relocation centers with the aim of growing food for direct consumption by inmates. There was also a less important aim of cultivating 'war crops' for the war effort. Agriculture in internment camps was faced with multiple challenges such as harsh weather and climate conditions however, on the most part the agricultural programs were a success mainly due to inmate knowledge and interest in agriculture. Due to their tenacious efforts, these farm lands remain active today.

nps

By the 1930s the ethnic Japanese population living in Seattle had reached 8,448, out of a total city population of 368,583 meaning that, "Japanese were Seattle’s largest non-white group, and the fourth-largest group behind several European nationalities." Prior to World War II, Seattle's Nihonmachi had become the second largest Japantown on the West Coast of North America. East of Lake Washington

Lake Washington is a large freshwater lake adjacent to the city of Seattle.

It is the largest lake in King County and the second largest natural lake in the state of Washington, after Lake Chelan. It borders the cities of Seattle on the west, ...

, Japanese immigrant labor helped clear recently logged land to make it suitable to support small scale farming on leased plots. During the 20th century, the Japanese farming community became increasingly well established. Prior to World War II, some 90 percent of the agricultural workforce on the " Eastside" was of Japanese ancestry, also 90% of produce sold at the Pike Place market in Seattle were from the Japanese-American farms from Bellevue and the White river valley.

Internment

interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

in ten different camps across the US, mostly in the west. The Internment was a 'system of legalized racial oppression' and were based on the race or ancestry rather than activities of the interned. Families, including children, were interned together. Each member of the family was allowed to bring two suitcases of their belongings. Each family, regardless of its size, was given one room to live in. The camps were fenced in and patrolled by armed guards. For the most part, the internees remained in the camps until the end of the war, when they left the camps to rebuild their lives.

World War II service

Many Japanese Americans served with great distinction during World War II in the American forces. Nebraska NiseiBen Kuroki

Ben Kuroki (May 16, 1917 – September 1, 2015) was the only American of Japanese Americans, Japanese descent in the United States Army Air Forces to serve in combat operations in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, Pacific theater of World ...

became a famous Japanese-American soldier of the war after he completed 30 missions as a gunner on B-24 Liberators with the 93rd Bombardment Group in Europe. When he returned to the US he was interviewed on radio and made numerous public appearances, including one at San Francisco's Commonwealth Club where he was given a ten-minute standing ovation after his speech. Kuroki's acceptance by the California businessmen was the turning point in attitudes toward Japanese on the West Coast. Kuroki volunteered to fly on a B-29 crew against his parents' homeland and was the only Nisei to fly missions over Japan. He was awarded a belated Distinguished Service Medal by President George W. Bush in August 2005.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team

The 442nd Infantry Regiment ( ja, 第442歩兵連隊) was an infantry regiment of the United States Army. The regiment is best known as the most decorated in U.S. military history and as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-gene ...

/100th Infantry Battalion

The 100th Infantry Battalion ( ja, 第100歩兵大隊, ''Dai Hyaku Hohei Daitai'') is the only infantry unit in the United States Army Reserve. In World War II, the then-primarily Nisei battalion was composed largely of former members of the Haw ...

is one of the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history. Composed of Japanese Americans, the 442nd/100th fought valiantly in the European Theater. The 522nd Nisei Field Artillery Battalion was one of the first units to liberate the prisoners of the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau

,

, commandant = List of commandants

, known for =

, location = Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany

, built by = Germany

, operated by = ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS)

, original use = Political prison

, construction ...

. Hawaii Senator Daniel Inouye

Daniel Ken Inouye ( ; September 7, 1924 – December 17, 2012) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States senator from Hawaii from 1963 until his death in 2012. Beginning in 1959, he was the first U.S. representative f ...

was a veteran of the 442nd. Additionally the Military Intelligence Service

The Military Intelligence Service ( ja, アメリカ陸軍情報部, ''America Rikugun Jōhōbu'') was a World War II U.S. military unit consisting of two branches, the Japanese American unit (described here) and the German-Austrian unit based ...

consisted of Japanese Americans who served in the Pacific Front.

On October 5, 2010, Congress approved the granting of the Congressional Gold Medal

The Congressional Gold Medal is an award bestowed by the United States Congress. It is Congress's highest expression of national appreciation for distinguished achievements and contributions by individuals or institutions. The congressional pract ...

to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 100th Infantry Battalion, as well as the 6,000 Japanese Americans who served in the Military Intelligence Service

The Military Intelligence Service ( ja, アメリカ陸軍情報部, ''America Rikugun Jōhōbu'') was a World War II U.S. military unit consisting of two branches, the Japanese American unit (described here) and the German-Austrian unit based ...

during the war.

Post-World War II and redress

In the U.S., the right to redress is defined as a constitutional right, as it is decreed in the First Amendment to the Constitution. Redress may be defined as follows: * 1. the setting right of what is wrong: redress of abuses. * 2. relief from wrong or injury. * 3. compensation or satisfaction from a wrong or injury Reparation is defined as: * 1. the making of amends for wrong or injury done: reparation for an injustice. * 2. compensation in money, material, labor, etc., payable by a defeated country to another country or to an individual for loss suffered during or as a result of war. * 3. restoration to good condition. * 4. repair. (“Legacies of Incarceration,” 2002) The campaign for redress against internment was launched by Japanese Americans in 1978. The Japanese American Citizens’ League (JACL) asked for three measures to be taken as redress: $25,000 to be awarded to each person who was detained, an apology from Congress acknowledging publicly that the U.S. government had been wrong, and the release of funds to set up an educational foundation for the children of Japanese American families. Eventually, theCivil Liberties Act of 1988

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (, title I, August 10, 1988, , et seq.) is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been wrongly interned by the United States government during World War II. The act was ...

granted reparations to surviving Japanese-Americans who had been interned by the United States government during World War II and officially acknowledged the "fundamental violations of the basic civil liberties and constitutional rights" of the internment.

Under the 2001 budget of the United States, it was decreed that the ten sites on which the detainee camps were set up are to be preserved as historical landmarks: “places like Manzanar

Manzanar is the site of one of ten American concentration camps, where more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II from March 1942 to November 1945. Although it had over 10,000 inmates at its peak, it was one o ...

, Tule Lake, Heart Mountain, Topaz, Amache, Jerome, and Rohwer will forever stand as reminders that this nation failed in its most sacred duty to protect its citizens against prejudice, greed, and political expediency” (Tateishi and Yoshino 2000).

Timeline

There is evidence to suggest that the first Japanese individual to land in North America was a young boy accompanying Franciscan friar, Martín Ignacio Loyola, in October 1587, on Loyola's second circumnavigation trip around the world.

There is evidence to suggest that the first Japanese individual to land in North America was a young boy accompanying Franciscan friar, Martín Ignacio Loyola, in October 1587, on Loyola's second circumnavigation trip around the world. Tanaka Shōsuke

Tanaka Shōsuke (田中 勝助, also 田中 勝介) was an important Japanese technician and trader in metals from Kyoto during the beginning of the 17th century.

According to Japanese archives (駿府記) he was a representative of the great Osa ...

visited North American in 1610 and 1613. Japanese castaway Oguri Jukichi

was one of the first Japanese citizens known to have reached present day California. He and his fourteen-man crew, bound for Edo, were sailing off the Japanese coast in 1813 when their ship, the ''Tokujomaru'', was disabled in a storm. The ship ...

was among the first Japanese citizens known to have reached present day California (1815). Otokichi

, also known as Yamamoto Otokichi and later known as John Matthew Ottoson (1818 – January 1867), was a Japanese castaway originally from the area of Onoura near modern-day Mihama, on the west coast of the Chita Peninsula in Aichi Prefecture ...

and two fellow castaways reached present day Washington state (1834).

* 1841: June 27 Captain Whitfield, commanding a New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

sailing vessel, rescues five shipwrecked Japanese sailors. Four disembark at Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

, however Manjiro Nakahama stays on board returning with Whitfield to Fairhaven, Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

. After attending school in New England and adopting the name John Manjiro, he later became an interpreter for Commodore Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a commodore of the United States Navy who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). He played a leading role in the o ...

.

* 1850: Seventeen survivors of a Japanese shipwreck are saved by the American freighter ''Auckland'' off the coast of California. In 1852, the group is sent to Macau

Macau or Macao (; ; ; ), officially the Macao Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China (MSAR), is a city and special administrative region of China in the western Pearl River Delta by the South China Sea. With a pop ...

to join Commodore Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a commodore of the United States Navy who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). He played a leading role in the o ...

as a gesture to help open diplomatic relations with Japan. One of them, Joseph Heco

Joseph Heco (born September 20, 1837 – December 12, 1897) was the first Japanese person to be naturalized as a United States citizen and the first to publish a Japanese language newspaper.

Early years

Hikozō Hamada was born in Harima pro ...

(Hikozo Hamada), goes on to become the first Japanese person to become a naturalized

Naturalization (or naturalisation) is the legal act or process by which a non-citizen of a country may acquire citizenship or nationality of that country. It may be done automatically by a statute, i.e., without any effort on the part of the in ...

American citizen.

* 1861: The utopian minister Thomas Lake Harris

Thomas Lake Harris (May 15, 1823 – March 23, 1906) was an Anglo-American preacher, spiritualistic prophet, poet, and vintner. Harris is best remembered as the leader of a series of communal religious experiments, culminating with a group called ...

of the Brotherhood of the New Life visits England, where he meets Nagasawa Kanaye, who becomes a convert. Nagasawa returns to the U.S. with Harris and follows him to Fountaingrove in Santa Rosa, California

Santa Rosa (Spanish language, Spanish for "Rose of Lima, Saint Rose") is a city and the county seat of Sonoma County, California, Sonoma County, in the North Bay (San Francisco Bay Area), North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area, Bay Area ...

. When Harris leaves the Californian commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

, Nagasawa became the leader and remained there until his death in 1932.

* 1866: Japanese students arrive in the United States, supported by the Japan Mission of the Reformed Church in America

The Reformed Church in America (RCA) is a Mainline Protestant, mainline Reformed tradition, Reformed Protestant Christian denomination, denomination in Canada and the United States. It has about 152,317 members. From its beginning in 1628 unti ...

which had opened in 1859 at Kanagawa

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Kantō region of Honshu. Kanagawa Prefecture is the List of Japanese prefectures by population, second-most populous prefecture of Japan at 9,221,129 (1 April 2022) and third-dens ...

.

* 1869: A group of Japanese people arrive at Gold Hills, California and build the Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony

The Wakamatsu Tea and Silk Farm Colony is believed to be the first permanent Japanese settlement in North America and the only settlement by samurai outside of Japan. The group was made up of 22 people from samurai families during the Boshin Civi ...

. Okei becomes the first recorded Japanese woman to die and be buried in the United States.

* 1882: The Chinese Exclusion Act

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law excluded merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplom ...

of 1882. This arguably left room for agricultural labor, encouraging immigration and recruitment of Japanese from both Hawaii and Japan.Kashima, T., ‘Nisei and Issei’, in. Personal Justice Denied (2nd edn, United States of America, 2000) p. 30

* 1884: The Japanese grants passports for contract labor in Hawaii where there was a demand for cheap labor.

* 1885: On February 8, the first official intake of Japanese migrants to a U.S.-controlled entity occurs when 676 men, 159 women, and 108 children arrive in Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

on board the Pacific Mail passenger freighter ''City of Tokio

SS ''City of Tokio'' (sometimes spelled ''City of Tokyo'') was an iron steamship built in 1874 by Delaware River Iron Ship Building and Engine Works for the Pacific Mail Steamship Company. ''City of Tokio'' and her sister ship '' City of Peking' ...

''. These immigrants, the first of many Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, have come to work as laborers on the island's sugar plantations via an assisted passage scheme organized by the Hawaiian government.

* 1886: The Japanese government legalizes emigration.

* 1893: The San Francisco Board of Education

The San Francisco Board of Education is the school board for the San Francisco, City and County of San Francisco. It is composed of seven Commissioners, elected by voters across the city to serve 4-year terms. It is subject to local, state, and f ...

attempts to introduce segregation for Japanese American children, but withdraws the measure following protests by the Japanese government.

* 1900s: Japanese immigrants begin to lease land and sharecrop.

* 1902: Yone Noguchi

was an influential Japanese writer of poetry, fiction, essays and literary criticism in both English and Japanese. He is known in the west as Yone Noguchi. He was the father of noted sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

Biography

Early life in Japan

Nogu ...

publishes ''The American Diary of a Japanese Girl

''The American Diary of a Japanese Girl'' is the first English-language novel published in the United States by a Japanese writer. Acquired for ''Frank Leslie's Illustrated Monthly Magazine'' by editor Ellery Sedgwick in 1901, it appeared in two e ...

'', the first Japanese American novel.

* 1903: In ''Yamataya v. Fisher

''Yamataya v. Fisher'', 189 U.S. 86 (1903), popularly known as the Japanese Immigrant Case, is a Supreme Court of the United States case about the federal government's power to exclude and deport certain classes of alien immigrants under the Immig ...

'' (Japanese Immigrant Case) the Supreme Court held that Japanese Kaoru Yamataya was subject to deportation since her Fifth Amendments due process was not violated in regards to the appeals process of the 1891 Immigration Act. This allowed for individuals to challenge their deportation in the courts by challenging the legitimacy of the procedures.

* 1906: The San Francisco Board of Education

The San Francisco Board of Education is the school board for the San Francisco, City and County of San Francisco. It is composed of seven Commissioners, elected by voters across the city to serve 4-year terms. It is subject to local, state, and f ...

orders the segregation of Asian students in public schools.

* 1907: The Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907

The was an informal agreement between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan whereby Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States and the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigrants already ...

between United States and Japan results in Japan ending the issuance passports for new laborers. Anti-Asian race riots took place in San Francisco took place in May.

* 1908: Japanese "picture bride

The term picture bride refers to the practice in the early 20th century of immigrant workers (chiefly Japanese, Okinawan, and Korean) in Hawaii and the West Coast of the United States and Canada, as well as Brazil selecting brides from their nat ...

s" enter the United States.

* 1913: The California Alien Land Law of 1913

The California Alien Land Law of 1913 (also known as the Webb–Haney Act) prohibited "aliens ineligible for citizenship" from owning agricultural land or possessing long-term leases over it, but permitted leases lasting up to three years. It affe ...

bans Japanese from purchasing land; whites felt threatened by Japanese success in independent farming ventures.

* 1924: The federal Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Eastern ...

banned immigration from Japan.

* 1927: Kinjiro Matsudaira

was an American inventor and politician who served as the mayor of Edmonston, Maryland in 1927 and 1943.

Biography

Matsudaira was born in Pennsylvania on September 13, 1885, as the son of a Japanese father, Tadaatsu, and an American mother, ...

becomes the first Japanese American to be elected mayor of a U.S. city (town of Edmonston, Maryland

Edmonston is a town in Prince George's County, Maryland, United States. As of the 2010 census, the town population was 1,445.

The community is located from Washington, D.C. Edmonston's ZIP code is 20781.

History

The area of present-day Edmon ...

).

* 1930s: ''Issei

is a Japanese-language term used by ethnic Japanese in countries in North America and South America to specify the Japanese people who were the first generation to immigrate there. are born in Japan; their children born in the new country are ...

'' become economically stable for the first time in California and Hawaii.

* 1941: Attack on Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, j ...

: Imperial Japanese forces attack the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

base at Naval Station Pearl Harbor

Naval Station Pearl Harbor is a United States naval base on the island of Oahu, Hawaii. In 2010, along with the United States Air Force's Hickam Air Force Base, the facility was merged to form Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam. Pearl Harbor is ...

in Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

. Japanese-American community leaders are arrested and detained by federal authorities.

* 1942: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

signs Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the secretary of war to prescribe certain ...

on February 19, beginning Japanese American internment

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

. Over the course of the war, approximately 110,000 Japanese Americans and Japanese who lived on the West Coast of the United States

The West Coast of the United States, also known as the Pacific Coast, Pacific states, and the western seaboard, is the coastline along which the Western United States meets the North Pacific Ocean. The term typically refers to the contiguous U.S ...

are uprooted from their homes and interned

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

.

* 1942: Japanese American soldiers from Hawaii form the 100th Infantry Battalion

The 100th Infantry Battalion ( ja, 第100歩兵大隊, ''Dai Hyaku Hohei Daitai'') is the only infantry unit in the United States Army Reserve. In World War II, the then-primarily Nisei battalion was composed largely of former members of the Haw ...

of the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

in June 1942. Subsequently, the battalion fights in Europe beginning in September 1943. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/100th%20Infantry%20Battalion/

* 1944: Ben Kuroki

Ben Kuroki (May 16, 1917 – September 1, 2015) was the only American of Japanese Americans, Japanese descent in the United States Army Air Forces to serve in combat operations in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II, Pacific theater of World ...

became the only Japanese-American in the U.S. Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

to serve in combat operations overseas, both in the European Theater, then in the Pacific Ocean theater of World War II.

* 1944: The U.S. Army 100th Battalion merges with the all-volunteer Japanese American 442nd Regimental Combat Team

The 442nd Infantry Regiment ( ja, 第442歩兵連隊) was an infantry regiment of the United States Army. The regiment is best known as the most decorated in U.S. military history and as a fighting unit composed almost entirely of second-gene ...

that was formed with men from Hawaii and the continental U.S. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/442nd%20Regimental%20Combat%20Team/

* 1945: Thirty thousand Japanese Americans were in Japan, unable to return to the United States since the nations were at war.

* 1945: The only Nisei unit of the U.S. Army in Bavaria assists in both the liberation of some of the satellite camps of Dachau, and by May 2, halts the Dachau-Austria death march, saving hundreds of prisoners.

* 1945: By war's end, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team is awarded 18,143 decorations, including 9,486 Purple Hearts, becoming the most decorated military unit in United States history

The history of the lands that became the United States began with the arrival of the first people in the Americas around 15,000 BC. Numerous indigenous cultures formed, and many saw transformations in the 16th century away from more densely ...

.

* 1947: Wally Kaname Yonamine

, was a Japanese American multi-sport athlete who played in the All-America Football Conference (AAFC) and Japan's Nippon Professional Baseball.

Early life

Kaname Yonamine, a Nisei Japanese American, was born in Olowalu, Maui, Hawaii to parents ...

plays football for the San Francisco 49ers

The San Francisco 49ers (also written as the San Francisco Forty-Niners) are a professional American football team based in the San Francisco Bay Area. The 49ers compete in the National Football League (NFL) as a member of the league's National ...

.

* 1947: Wataru Misaka

Wataru Misaka (December 21, 1923 – November 20, 2019) was an American professional basketball player. A point guard of Japanese descent, he broke a color barrier in professional basketball by being the first non-white player and the first p ...

plays basketball for the New York Knicks

The New York Knickerbockers, shortened and more commonly referred to as the New York Knicks, are an American professional basketball team based in the New York City borough of Manhattan. The Knicks compete in the National Basketball Associat ...

.

* 1952: The McCarran–Walter Act eliminates race as a basis for naturalization, allowing Issei to become US citizens.

* 1952: Tommy Kono

Tamio "Tommy" Kono (June 27, 1930 – April 24, 2016) was a Japanese American weightlifter in the 1950s and 1960s. Kono set world records in four different weight classes: lightweight (149 pounds or 67.5 kilograms), middleweight (165 lb or ...

(weightlifting), Yoshinobu Oyakawa

Yoshinobu Oyakawa (born August 9, 1933) is an American former competition swimming (sport), swimmer, Olympic champion, and former world record-holder in the 100-meter backstroke. Oyakawa is considered to be the last of the great "straight-arm-pu ...

(100-meter backstroke), and Ford Konno

Ford Hiroshi Konno (born January 1, 1933) is a Japanese–American former competition swimmer, two-time Olympic champion, and former world record-holder in three events.

Konno was born in Honolulu, Hawaii. He attended McKinley High School in Ho ...

(1500-meter freestyle) each win gold medals and set records during the Summer Olympics in Helsinki.

* 1957: Miyoshi Umeki

was a Japanese-American singer and actress.Bernstein, Adam ''The Washington Post''. 5 September 2007. Umeki was a Tony Award- and Golden Globe-nominated actress and the first East Asian-American woman to win an Academy Award for acting.

Life

Bo ...

wins the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress.

* 1957: James Kanno

James Kanno (December 22, 1925 – July 15, 2017) served as the first mayor of Fountain Valley, California from 1957 to 1962. He was one of the first mayors of Asian descent in the United States.

Biography

Kanno was born in an unincorporated ...

is elected as the first mayor of California's Fountain Valley.

* 1959: Daniel K. Inouye is elected to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

, becoming the first Japanese American to serve in Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

.

* 1962: Minoru Yamasaki

was an American architect, best known for designing the original World Trade Center in New York City and several other large-scale projects. Yamasaki was one of the most prominent architects of the 20th century. He and fellow architect Edward D ...

is awarded the contract to design the World Trade Center

World Trade Centers are sites recognized by the World Trade Centers Association.

World Trade Center may refer to:

Buildings

* List of World Trade Centers

* World Trade Center (2001–present), a building complex that includes five skyscrapers, a ...

, becoming the first Japanese American architect to design a supertall skyscraper in the United States.

* 1963: Daniel K. Inouye becomes the first Japanese American in the United States Senate.

* 1965: Patsy T. Mink

Patsy Matsu Mink (née Takemoto; December 6, 1927 – September 28, 2002) was an American attorney and politician from the U.S. state of Hawaii. Mink was a third-generation Japanese American, having been born and raised on the island of Maui ...

becomes the first woman of color in Congress.

* 1971: Norman Y. Mineta

Norman Yoshio Mineta ( ja, 峯田 良雄, November 12, 1931 – May 3, 2022) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, Mineta served in the United States Cabinet for Presidents Bill Clinton, a Democrat, and George W. Bush, a R ...

is elected mayor of San Jose, California

San Jose, officially San José (; ; ), is a major city in the U.S. state of California that is the cultural, financial, and political center of Silicon Valley and largest city in Northern California by both population and area. With a 2020 popul ...

, becoming the first Asian American mayor of a major U.S. city.

* 1972: Robert A. Nakamura produces ''Manzanar

Manzanar is the site of one of ten American concentration camps, where more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II from March 1942 to November 1945. Although it had over 10,000 inmates at its peak, it was one o ...

'', the first personal documentary about internment.

* 1974: Fujio Matsuda becomes the first Asian-American president of a major American university, as president of the University of Hawaiʻi

The University of Hawaiʻi System, formally the University of Hawaiʻi and popularly known as UH, is a public college and university system that confers associate, bachelor's, master's, and doctoral degrees through three universities, seven com ...

.

* 1974: George R. Ariyoshi becomes the first elected Japanese American governor in the State of Hawaii.

* 1976: S. I. Hayakawa of California and Spark Matsunaga

Spark Masayuki Matsunaga ( ja, 松永 正幸, October 8, 1916April 15, 1990) was an American politician and attorney who served as United States Senator for Hawaii from 1977 until his death in 1990. Matsunaga also represented Hawaii in the U.S. ...

of Hawaii become the second and third U.S. Senators of Japanese descent.

* 1977: Michiko (Miki) Gorman wins both the Boston and New York City marathons in the same year. It's her second victory in each race.

* 1978: Ellison S. Onizuka becomes the first Asian American astronaut. Onizuka was one of the seven astronauts to die in the Space Shuttle ''Challenger'' disaster in 1986.

* 1980: Congress creates the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) was a group of nine people appointed by the U.S. Congress in 1980 to conduct an official governmental study into the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

Pr ...

to investigate internment during World War II.

* 1980: Eunice Sato

Eunice Noda Sato (June 8, 1921 – February 12, 2021) was an American politician. She served as mayor of Long Beach, California from 1980 to 1982. As such she was the first Asian-American female mayor of a major American city, as well as the firs ...

becomes the first Asian-American female mayor of a major American city when she was elected mayor of Long Beach, California

Long Beach is a city in Los Angeles County, California. It is the 42nd-most populous city in the United States, with a population of 466,742 as of 2020. A charter city, Long Beach is the seventh-most populous city in California.

Incorporate ...

.

* 1983: The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians reports that Japanese-American internment was not justified by military necessity and that internment was based on "race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership." The Commission recommends an official Government apology; redress payments of $20,000 to each of the survivors; and a public education fund to help ensure that this would not happen again.

* 1987: Charles J. Pedersen

Charles John Pedersen ( ja, 安井 良男, ''Yasui Yoshio'', October 3, 1904 – October 26, 1989) was an American organic chemist best known for describing methods of synthesizing crown ethers during his entire 42-year career as a chemist for D ...

wins the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his methods of synthesizing crown ethers

* 1988: President Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan ( ; February 6, 1911June 5, 2004) was an American politician, actor, and union leader who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He also served as the 33rd governor of California from 1967 ...

signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 (, title I, August 10, 1988, , et seq.) is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been wrongly interned by the United States government during World War II. The act was ...

, apologizing for Japanese-American internment and providing reparations of $20,000 to each former internee who was still alive when the act was passed.

* 1992: The Japanese American National Museum

The is located in Los Angeles, California, and dedicated to preserving the history and culture of Japanese Americans. Founded in 1992, it is located in the Little Tokyo area near downtown. The museum is an affiliate within the Smithsonian Affil ...

opens in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles

Little Tokyo ( ja, リトル・トーキョー) also known as Little Tokyo Historic District, is an ethnically Japanese American district in downtown Los Angeles and the heart of the largest Japanese-American population in North America. It is t ...

.

* 1992: Kristi Yamaguchi

Kristine Tsuya Yamaguchi (born July 12, 1971) is an American former figure skater. In ladies' singles, Yamaguchi is the 1992 Olympic champion, a two-time World champion (1991 and 1992), and the 1992 U.S. champion. In 1992, she became the first ...

wins the Olympic gold medal and her second World Championship title in figure skating.

* 1994: Mazie K. Hirono

Mazie Keiko Hirono (; Japanese name: , ; born November 3, 1947) is an American lawyer and politician serving as the Seniority in the United States Senate, junior United States Senate, United States senator from Hawaii since 2013. A member of the ...

is elected Lieutenant Governor of Hawaii

The lieutenant governor of Hawaii ( haw, Hope kiaʻāina o Hawaiʻi) is the assistant chief executive of the U.S. state of Hawaii and its various agencies and departments, as provided in the Article V, Sections 2 though 6 of the Constitution of H ...

, becoming the first Japanese immigrant elected state lieutenant governor of a state. Hirono later is elected in the U.S. House of Representatives.

* 1996: A. Wallace Tashima

Atsushi Wallace Tashima (born June 24, 1934) is a Senior United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and a former United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the Central Distric ...

is nominated to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit (in case citations, 9th Cir.) is the U.S. federal court of appeals that has appellate jurisdiction over the U.S. district courts in the following federal judicial districts:

* District ...

and becomes the first Japanese American to serve as a judge of a United States court of appeals

United may refer to:

Places

* United, Pennsylvania, an unincorporated community

* United, West Virginia, an unincorporated community

Arts and entertainment Films

* ''United'' (2003 film), a Norwegian film

* ''United'' (2011 film), a BBC Two fi ...

.

* 1998: Chris Tashima

Christopher Inadomi Tashima (born March 24, 1960) is a Japanese American actor and director. He is co-founder of the entertainment company Cedar Grove Productions and Artistic Director of its Asian American theatre company, Cedar Grove OnStage. T ...

becomes the first U.S.-born Japanese American actor to win an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

for his role in the film ''Visas and Virtue

''Visas and Virtue'' is a 1997 narrative short film directed by Chris Tashima and starring Chris Tashima, Susan Fukuda, Diana Georger and Lawrence Craig. It was inspired by the true story of Holocaust rescuer Chiune "Sempo" Sugihara, who is known ...

''.

* 1999: U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

General Eric Shinseki

Eric Ken Shinseki (; born November 28, 1942) is a retired United States Army general who served as the seventh United States Secretary of Veterans Affairs (2009–2014). His final United States Army post was as the 34th Chief of Staff of the Arm ...

becomes the first Asian American to serve as chief of staff of a branch of the armed forces

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

. Shinseki later served as Secretary of Veterans Affairs

The United States secretary of veterans affairs is the head of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, the department concerned with veterans' benefits, health care, and national veterans' memorials and cemeteries. The secretary is a me ...

(2009–2014).

* 2000: Norman Y. Mineta

Norman Yoshio Mineta ( ja, 峯田 良雄, November 12, 1931 – May 3, 2022) was an American politician. A member of the Democratic Party, Mineta served in the United States Cabinet for Presidents Bill Clinton, a Democrat, and George W. Bush, a R ...

becomes the first Asian American appointed to the United States Cabinet

The Cabinet of the United States is a body consisting of the vice president of the United States and the heads of the executive branch's departments in the federal government of the United States. It is the principal official advisory body to ...

. He serves as Secretary of Commerce

The United States secretary of commerce (SecCom) is the head of the United States Department of Commerce. The secretary serves as the principal advisor to the president of the United States on all matters relating to commerce. The secretary rep ...

from 2000–2001 and Secretary of Transportation

A secretary, administrative professional, administrative assistant, executive assistant, administrative officer, administrative support specialist, clerk, military assistant, management assistant, office secretary, or personal assistant is a wh ...

from 2001–2006.

* 2008: Yoichiro Nambu

was a Japanese-American physicist and professor at the University of Chicago. Known for his contributions to the field of theoretical physics, he was awarded half of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2008 for the discovery in 1960 of the mechanism ...

wins the Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on quantum chromodynamics and spontaneous symmetry breaking.

* 2010: Daniel K. Inouye becomes the highest ranking Asian American politician in U.S. history when he succeeds Robert Byrd

Robert Carlyle Byrd (born Cornelius Calvin Sale Jr.; November 20, 1917 – June 28, 2010) was an American politician and musician who served as a United States senator from West Virginia for over 51 years, from 1959 until his death in 2010. A ...

as President pro tempore of the United States Senate

The president pro tempore of the United States Senate (often shortened to president pro tem) is the second-highest-ranking official of the United States Senate, after the Vice President of the United States, vice president. According to Articl ...

.

* 2011: The Nisei Soldiers of World War II Congressional Gold Medal The Nisei Soldiers of World War II Congressional Gold Medal is an award made for the Japanese American World War II veterans of the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the Military Intelligence Service. The Congressional G ...

was awarded in recognition of the World War II service of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, the 100th Infantry Battalion, and Nisei serving in the Military Intelligence Service on November 2, 2011.

* 2014: Shuji Nakamura

is a Japanese-born American electronic engineer and inventor specializing in the field of semiconductor technology, professor at the Materials Department of the College of Engineering, University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB), and is regar ...

wins the 2014 Nobel Prize in Physics for the invention of efficient blue light-emitting diodes.

* 2018: Chief Justice Roberts

John Glover Roberts Jr. (born January 27, 1955) is an American lawyer and jurist who has served as the 17th Chief Justice of the United States, chief justice of the United States since 2005. Roberts has authored the majority opinion in sever ...

, in writing the majority opinion of the Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

in ''Trump v. Hawaii

''Trump v. Hawaii'', No. 17-965, 585 U.S. ___ (2018), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case involving Presidential Proclamation 9645 signed by President Donald Trump, which restricted travel into the United States by people from sever ...

'', effectively repudiates the 1944 decision ''Korematsu v. United States

''Korematsu v. United States'', 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States to uphold the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has been wid ...

'' that had upheld the constitutionality of Executive Order 9066

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the secretary of war to prescribe certain ...

.

See also

*Japanese diaspora

The Japanese diaspora and its individual members, known as Nikkei (日系) or as Nikkeijin (日系人), comprise the Japanese emigrants from Japan (and their descendants) residing in a country outside Japan. Emigration from Japan was recorded as ...

* Nisei Baseball Research Project

The Nisei Baseball Research Project (NBRP) is a non-profit 501(c)(3) organization documenting, preserving and exhibiting history of Japanese American baseball. It was founded by Kerry Yo Nakagawa, the author of ''Through a Diamond: 100 Years of ...

References

Text of the Immigration Act of 1907

Further reading

* "Present-Day Immigration with Special Reference to the Japanese," ''Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science'' (Jan 1921), pp. 1–232online

24 articles by experts, mostly about California. * Chin, Frank. ''Born in the USA: A Story of Japanese America, 1889–1947'' (Rowman & Littlefield, 2002). * Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. ''Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians'' (Washington, GPO: 1982) * Conroy, Hilary, and Miyakawa T. Scott, eds. ''East Across the Pacific: Historical & Sociological Studies of Japanese Immigration & Assimilation'' (1972), essays by scholars * Daniels, Roger. ''Asian America: Chinese and Japanese in the United States since 1850'' (U of Washington Press, 1988

online edition

* Daniels, Roger. ''Concentration Camps, North America: Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II'' (1981). * Daniels, Roger. ''The Politics of Prejudice: The Anti-Japanese Movement in California and the Struggle for Japanese Exclusion'' (2nd ed. 1978) * Daniels, Roger, et al. eds. ''Japanese Americans: From Relocation to Redress'' (2nd ed. 1991) * Easton, Stanley E. and Lucien Ellington. "Japanese Americans." in ''Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America,'' edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 2, Gale, 2014, pp. 537–555

Online

* * Ichioka, Yuji. "Amerika Nadeshiko: Japanese Immigrant Women in the United States, 1900-1924," ''Pacific Historical Review'' Vol. 49, No. 2 (May, 1980), pp. 339–35

in JSTOR

* Ichioka, Yuji. "Japanese Associations and the Japanese Government: A Special Relationship, 1909–1926," ''Pacific Historical Review'' Vol. 46, No. 3 (Aug., 1977), pp. 409–43

in JSTOR

* Ichioka, Yuji. "Japanese Immigrant Response to the 1920 California Alien Land Law," ''Agricultural History'' Vol. 58, No. 2 (Apr., 1984), pp. 157–17

in JSTOR

* Matsumoto, Valerie J. ''Farming the Home Place: A Japanese American Community in California, 1919–1982'' (1993) * Modell John. ''The Economics and Politics of Racial Accommodation: The Japanese of Los Angeles, 1900–1942'' (1977) * Niiya, Brian, ed. ''Encyclopedia of Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present.'' (2001)

online free to borrow

* Takaki, Ronald. ''Strangers from a Different Shore'' (2nd ed. 1998) * Wakatsuki Yasuo. "Japanese Emigration to the United States, 1866–1924: A Monograph." ''Perspectives in American History'' 12 (1979): 387–516. {{DEFAULTSORT:Japanese American History Japanese American