History Of Fencing on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The oldest surviving manual on western swordsmanship dates back to the 14th century, although historical references date fencing schools back to the 12th century.

Sword fighting schools can be found in European historical records dating back to the 12th century. In later times sword fighting teachers were paid by rich patrons to produce books about their fighting systems, called treatises. Sword fighting schools were forbidden in some European cities (particularly in

Sword fighting schools can be found in European historical records dating back to the 12th century. In later times sword fighting teachers were paid by rich patrons to produce books about their fighting systems, called treatises. Sword fighting schools were forbidden in some European cities (particularly in  From 1400 onward, an increasing number of sword fighting treatises survived from across Europe, with the majority from the 15th century coming from

From 1400 onward, an increasing number of sword fighting treatises survived from across Europe, with the majority from the 15th century coming from  The

The

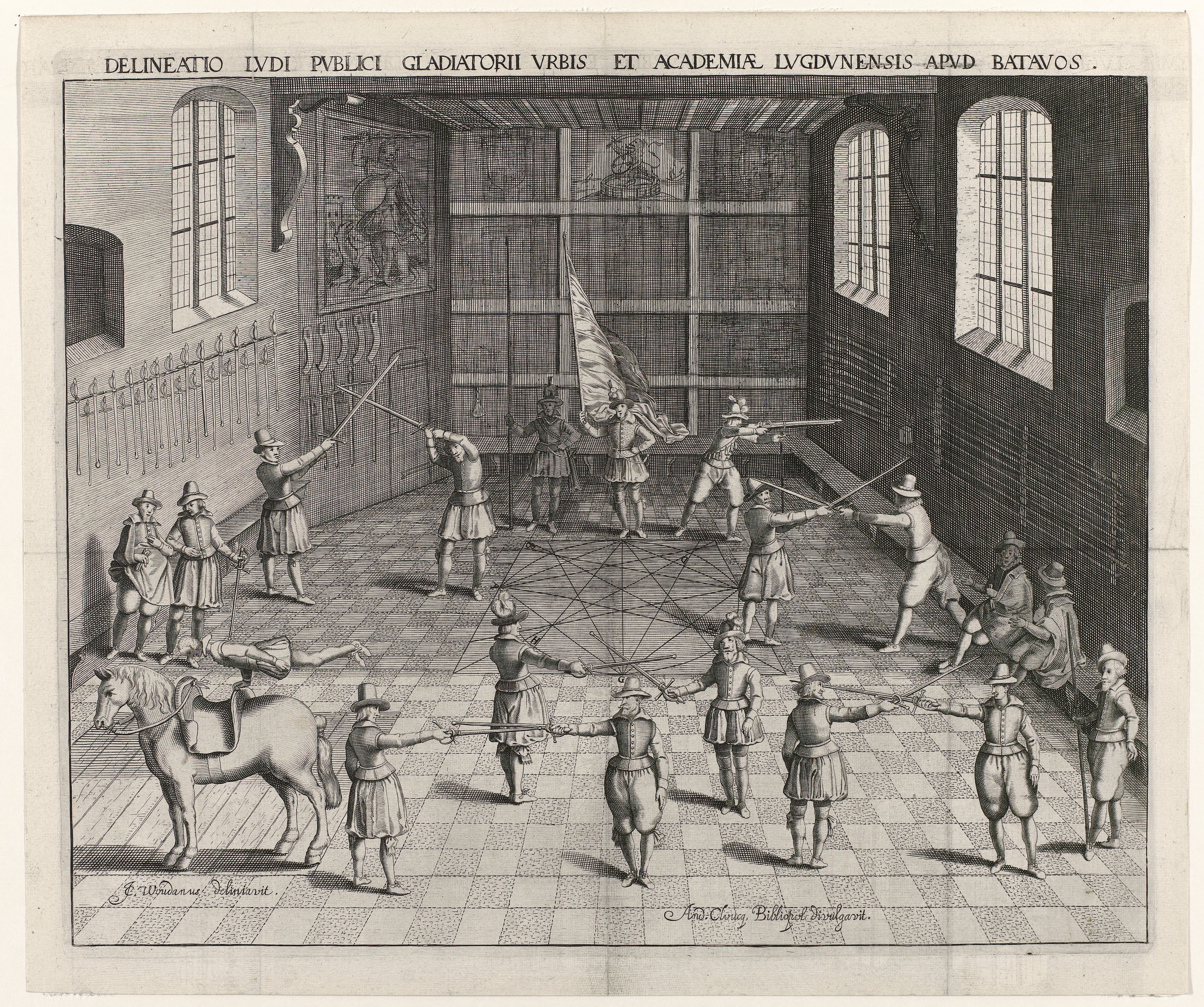

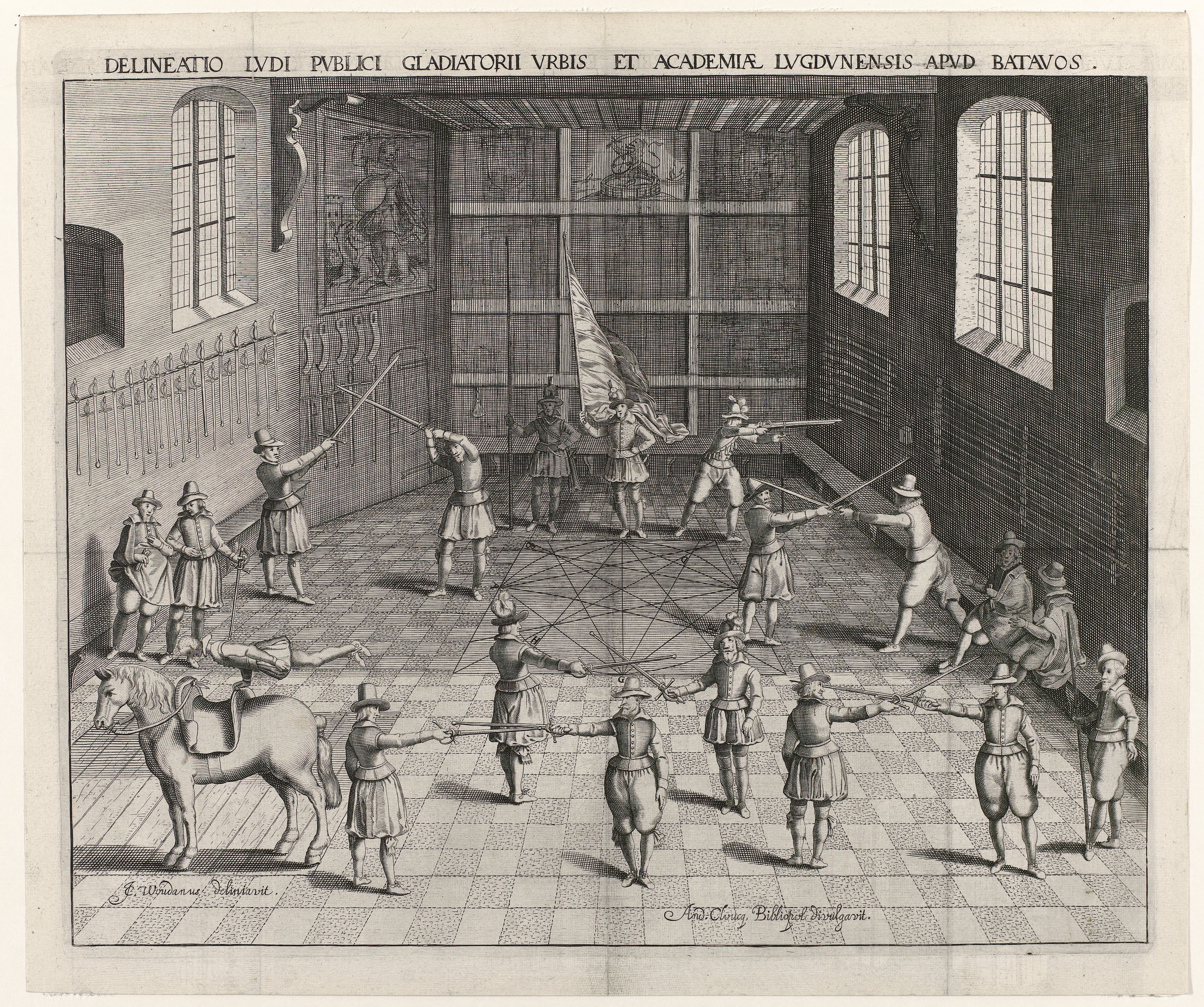

Fencing was a popular form of staged entertainment in 16th- and 17th-century England. It was also a fashionable (although somewhat controversial) martial art. In 1540

Fencing was a popular form of staged entertainment in 16th- and 17th-century England. It was also a fashionable (although somewhat controversial) martial art. In 1540  Around the same time, a number of significant fencing manuals were written in or translated into English. Prizefights were bloody but rarely lethal.

Around the same time, a number of significant fencing manuals were written in or translated into English. Prizefights were bloody but rarely lethal.

Until the first half of the 19th century all types of academic fencing can be seen as

Until the first half of the 19th century all types of academic fencing can be seen as

The need to train swordsmen for combat in a nonlethal manner led fencing and swordsmanship to include a sport aspect from its beginnings, from before the medieval tournament right up to the modern age.

The shift towards fencing as a sport rather than as military training happened from the mid-18th century, and was led by

The need to train swordsmen for combat in a nonlethal manner led fencing and swordsmanship to include a sport aspect from its beginnings, from before the medieval tournament right up to the modern age.

The shift towards fencing as a sport rather than as military training happened from the mid-18th century, and was led by  As fencing progressed, the combat aspect slowly faded until only the rules of the

As fencing progressed, the combat aspect slowly faded until only the rules of the

Fencing history

(accessed 21 Jan 2016) Épée was introduced in 1900 (Paris). Foil was omitted from the 1908 (London) Olympics, but since 1912, fencing events for every weapon—Foil, Épée and Sabre—have been held at every

Modern fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the Foil (fencing), foil, the épée, and the Sabre (fencing), sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an ...

originated in the 18th century in the Italian school of fencing

The term Italian school of swordsmanship is used to describe the Italian style of fencing and edged-weapon combat from the time of the first extant Italian swordsmanship treatise (1409) to the days of Classical Fencing (up to 1900).

Although the ...

of the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, and, under its influence, was improved by the French school. The Spanish school didn't become prominent until the 19th century. Nowadays, these three schools are the most influential around the world.

Terminology

The English term ''fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, s ...

'', in the sense of "the action or art of using the sword scientifically" (OED

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the first and foundational historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP). It traces the historical development of the English language, providing a co ...

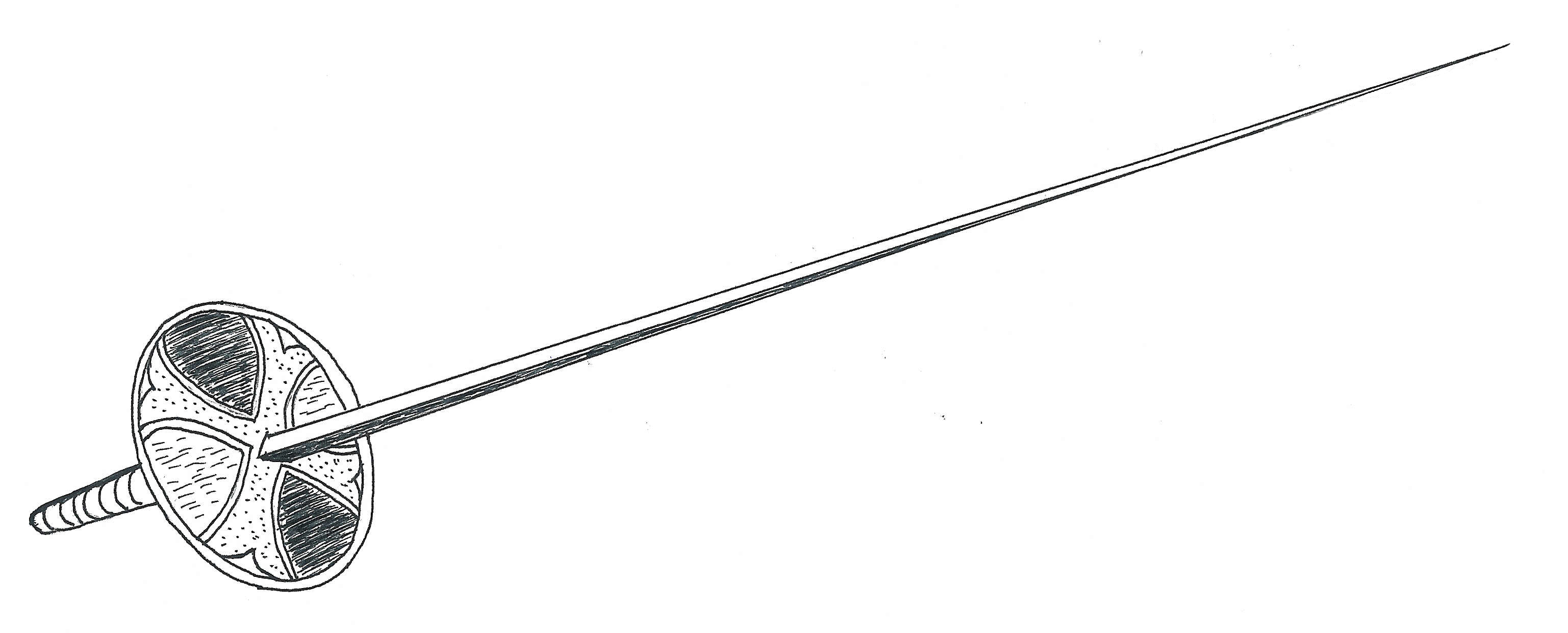

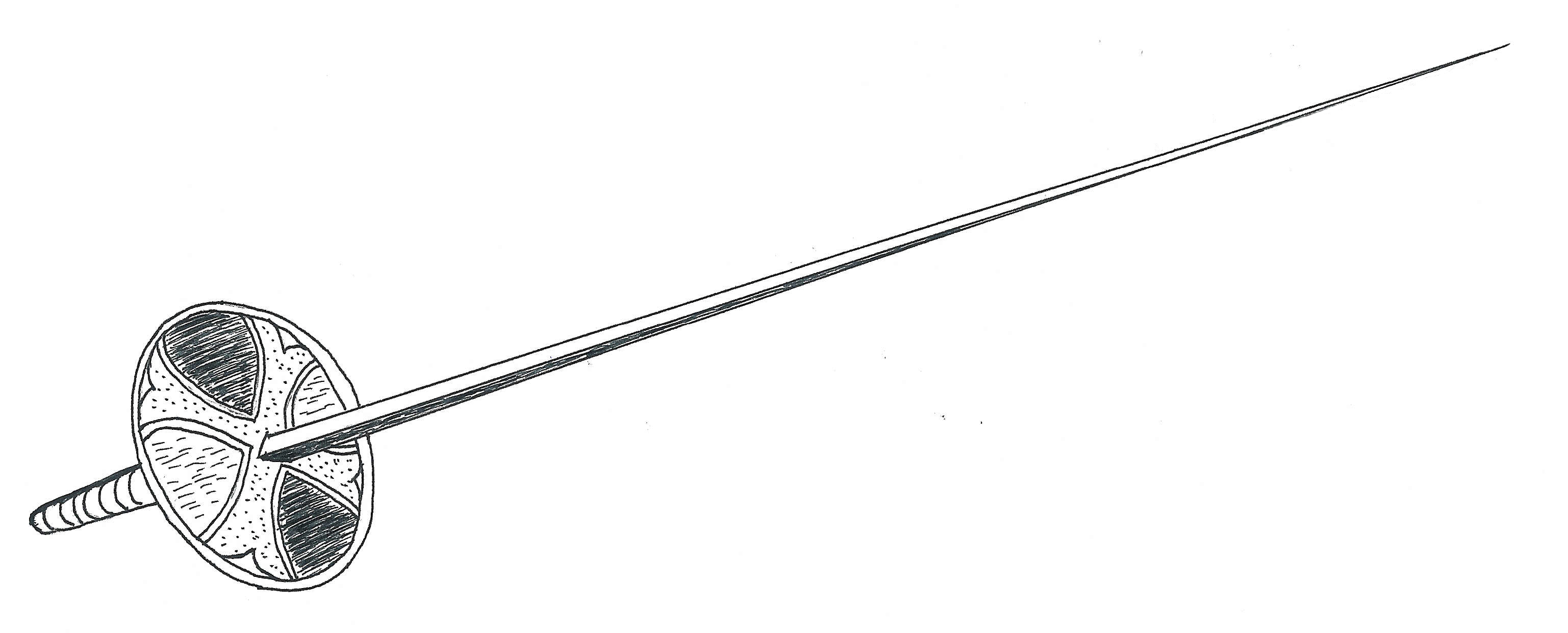

), dates to the late 16th century, when it denoted systems designed for the Renaissance rapier

A rapier () or is a type of sword with a slender and sharply-pointed two-edged blade that was popular in Western Europe, both for civilian use (dueling and self-defense) and as a military side arm, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

Impor ...

. It is derived from the latinate ''defence'' (while conversely, the Romance term for fencing, ''scherma, escrima'' are derived from the Germanic (Old Frankish) '' *skrim'' "to shield, cover, defend").

The verb ''to fence'' derived from the noun ''fence'', originally meaning "the act of defending", etymologically

Etymology ()The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p. 633 "Etymology /ˌɛtɪˈmɒlədʒi/ the study of the class in words and the way their meanings have changed throughout time". is the study of the history of the form of words an ...

derived from Old French ''defens'' "defence

Defense or defence may refer to:

Tactical, martial, and political acts or groups

* Defense (military), forces primarily intended for warfare

* Civil defense, the organizing of civilians to deal with emergencies or enemy attacks

* Defense industr ...

", ultimately from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

. The first attestation of Middle English

Middle English (abbreviated to ME) is a form of the English language that was spoken after the Norman conquest of 1066, until the late 15th century. The English language underwent distinct variations and developments following the Old English p ...

''fens'' "defence" dates to the 14th century; the derived meaning "to surround with a fence" dates to c. 1500.

The first known English use of ''fence'' in reference to Renaissance swordsmanship is in William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

's ''Merry Wives of Windsor

''The Merry Wives of Windsor'' or ''Sir John Falstaff and the Merry Wives of Windsor'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare first published in 1602, though believed to have been written in or before 1597. The Windsor of the play's title is a ref ...

'', (act i, scene 1), "with playing at sword and dagger with a master of fence," , and later, (act 2, scene 3) "Alas sir, I cannot fence" the term "fencer" is used in Much Ado About Nothing

''Much Ado About Nothing'' is a comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599.See textual notes to ''Much Ado About Nothing'' in ''The Norton Shakespeare'' ( W. W. Norton & Company, 1997 ) p. 1387 The play ...

, "blunt as the fencer's foils, which hit, but hurt not." This specialized usage replaced the generic ''fight

Combat ( French for ''fight'') is a purposeful violent conflict meant to physically harm or kill the opposition. Combat may be armed (using weapons) or unarmed ( not using weapons). Combat is sometimes resorted to as a method of self-defense, or ...

'' (Old English

Old English (, ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain, Anglo ...

''feohtan'', cognate with the German ''fechten'', which remains the standard term for "fencing" in Modern German).

Antiquity

The origins of armed combat are prehistoric, beginning withclub

Club may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Club'' (magazine)

* Club, a ''Yie Ar Kung-Fu'' character

* Clubs (suit), a suit of playing cards

* Club music

* "Club", by Kelsea Ballerini from the album ''kelsea''

Brands and enterprises

...

, spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

, axe

An axe ( sometimes ax in American English; see spelling differences) is an implement that has been used for millennia to shape, split and cut wood, to harvest timber, as a weapon, and as a ceremonial or heraldic symbol. The axe has ma ...

, and knife

A knife ( : knives; from Old Norse 'knife, dirk') is a tool or weapon with a cutting edge or blade, usually attached to a handle or hilt. One of the earliest tools used by humanity, knives appeared at least 2.5 million years ago, as evidenced ...

. Fighting with shield

A shield is a piece of personal armour held in the hand, which may or may not be strapped to the wrist or forearm. Shields are used to intercept specific attacks, whether from close-ranged weaponry or projectiles such as arrows, by means of a ...

and sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

developed in the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

; bladed weapons such as the khopesh

The ''khopesh'' ('; also vocalized khepesh) is an Egyptian sickle-shaped sword that evolved from battle axes.

Description

A typical ''khopesh'' is 50–60 cm (20–24 inches) in length, though smaller examples also exist. The inside c ...

appeared in the Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

and the proper sword in the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

.

The first historical evidence from archaeology of a fencing contest was found on the wall of a temple within Egypt built at a time dated to approximately 1190 B.C.

Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

's ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odysse ...

'' includes some of the earliest descriptions of combat with shield, sword and spear, usually between two heroes who pick one another for a duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

. Roman gladiator

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gla ...

s engaged in dual combat in a sport-like setting, evolving out of Etruscan __NOTOC__

Etruscan may refer to:

Ancient civilization

*The Etruscan language, an extinct language in ancient Italy

*Something derived from or related to the Etruscan civilization

**Etruscan architecture

**Etruscan art

**Etruscan cities

** Etrusca ...

ritual. Tomb fresco

Fresco (plural ''frescos'' or ''frescoes'') is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaste ...

es from Paestum

Paestum ( , , ) was a major ancient Greek city on the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea in Magna Graecia (southern Italy). The ruins of Paestum are famous for their three ancient Greek temples in the Doric order, dating from about 550 to 450 BC, whic ...

(4th century BC) show paired fighters with helmets, spears and shields, in a propitiatory funeral blood rite

A blood ritual is any ritual that involves the intentional release of blood.

A common blood ritual is the blood brother ritual, which started in ancient Europe and Asia. Two or more people, typically male, intermingle their blood in some way. Th ...

that anticipates gladiator games.

Romans who frequented the gym

A gymnasium, also known as a gym, is an indoor location for athletics. The word is derived from the ancient Greek term " gymnasium". They are commonly found in athletic and fitness centres, and as activity and learning spaces in educational ins ...

nasia and baths often fenced with a stick whose point was covered with a ball. Vegetius

Publius (or Flavius) Vegetius Renatus, known as Vegetius (), was a writer of the Later Roman Empire (late 4th century). Nothing is known of his life or station beyond what is contained in his two surviving works: ''Epitoma rei militaris'' (also re ...

, the Late Roman military

The military of ancient Rome, according to Titus Livius, one of the more illustrious historians of Rome over the centuries, was a key element in the rise of Rome over "above seven hundred years" from a small settlement in Latium to the capital of ...

writer, described practicing against a post and fencing with other soldiers. Vegetius describes how the Romans preferred the thrust over the cut, because puncture wounds enter the vital organ

In biology, an organ is a collection of tissues joined in a structural unit to serve a common function. In the hierarchy of life, an organ lies between tissue and an organ system. Tissues are formed from same type cells to act together in a ...

s directly whereas cuts are often stopped by armour

Armour (British English) or armor (American English; see spelling differences) is a covering used to protect an object, individual, or vehicle from physical injury or damage, especially direct contact weapons or projectiles during combat, or fr ...

and bone

A bone is a Stiffness, rigid Organ (biology), organ that constitutes part of the skeleton in most vertebrate animals. Bones protect the various other organs of the body, produce red blood cell, red and white blood cells, store minerals, provid ...

. Raising the arm to deliver a cut exposes the side to a thrust. This doctrine was exploited by Italian fencing masters in the 16th Century and became the primary rationale behind both the Italian and French schools of fencing.

Middle Ages and Renaissance

Sword fighting schools can be found in European historical records dating back to the 12th century. In later times sword fighting teachers were paid by rich patrons to produce books about their fighting systems, called treatises. Sword fighting schools were forbidden in some European cities (particularly in

Sword fighting schools can be found in European historical records dating back to the 12th century. In later times sword fighting teachers were paid by rich patrons to produce books about their fighting systems, called treatises. Sword fighting schools were forbidden in some European cities (particularly in England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

) during the medieval period, though court records show that such schools operated illegally.

The earliest surviving treatise on sword fighting, stored at the Royal Armouries Museum

The Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England, is a national museum which displays the National Collection of Arms and Armour. It is part of the Royal Armouries family of museums, with other sites at the Royal Armouries' traditio ...

in Leeds

Leeds () is a city and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds district in West Yorkshire, England. It is built around the River Aire and is in the eastern foothills of the Pennines. It is also the third-largest settlement (by populati ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, dates from around 1300 AD and is from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

. It is known as I.33

Royal Armouries Ms. I.33 is the earliest known surviving European ''fechtbuch'' (combat manual), and one of the oldest surviving martial arts manuals dealing with armed combat worldwide. I.33 is also known as the Walpurgis manuscript, after a fig ...

and written in medieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. In this region it served as the primary written language, though local languages were also written to varying degrees. Latin functioned ...

and Middle High German

Middle High German (MHG; german: Mittelhochdeutsch (Mhd.)) is the term for the form of German spoken in the High Middle Ages. It is conventionally dated between 1050 and 1350, developing from Old High German and into Early New High German. High ...

and deals with an advanced system of using the sword

A sword is an edged, bladed weapon intended for manual cutting or thrusting. Its blade, longer than a knife or dagger, is attached to a hilt and can be straight or curved. A thrusting sword tends to have a straighter blade with a pointed ti ...

and buckler

A buckler (French ''bouclier'' 'shield', from Old French ''bocle, boucle'' 'boss') is a small shield, up to 45 cm (up to 18 in) in diameter, gripped in the fist with a central handle behind the boss. While being used in Europe since an ...

(smallest shield) together.

From 1400 onward, an increasing number of sword fighting treatises survived from across Europe, with the majority from the 15th century coming from

From 1400 onward, an increasing number of sword fighting treatises survived from across Europe, with the majority from the 15th century coming from Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

and Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

. In this period these arts were largely reserved for the knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the Gr ...

hood and the nobility – hence most treatises deal with knightly weapons such as the rondel dagger

A rondel dagger or roundel dagger was a type of stiff-bladed dagger in Europe in the late Middle Ages (from the 14th century onwards), used by a variety of people from merchants to knights. It was worn at the waist and might be used as a util ...

, longsword

A longsword (also spelled as long sword or long-sword) is a type of European sword characterized as having a cruciform hilt with a grip for primarily two-handed use (around ), a straight double-edged blade of around , and weighing approximatel ...

, spear

A spear is a pole weapon consisting of a shaft, usually of wood, with a pointed head. The head may be simply the sharpened end of the shaft itself, as is the case with fire hardened spears, or it may be made of a more durable material fasten ...

, pollaxe

The poleaxe (also pollaxe, pole-axe, pole axe, poleax, polax) is a European polearm that was widely used by medieval infantry.

Etymology

Most etymological authorities consider the ''poll''- prefix historically unrelated to "pole", instead mea ...

and armoured fighting mounted and on foot. Some treatises cover weapons available to the common classes, such as großes Messer

A messer (German for "knife") is a single-edged sword with a knife-like hilt. While the various names are often used synonymously, messers are divided into two types:

''Lange Messer'' ("long knives") are one-handed swords used for self-defence ...

and sword and buckler. Wrestling

Wrestling is a series of combat sports involving grappling-type techniques such as clinch fighting, throws and takedowns, joint locks, pins and other grappling holds. Wrestling techniques have been incorporated into martial arts, combat ...

, both with and without weapons, armoured and unarmoured, was also featured heavily in the early sword fighting treatises.

The very first manual of fencing was published during 1471, by Diego de Valera

Mosén Diego de Valera (1412–1488) was a Spanish nobleman, author, and historian who has been described as having had "chivalrous adventures" that took him "as far as Bohemia" where he was a participant in the Hussite Wars. He authored letter ...

.(in spite of the title, the book of Diego de Valera was mainly focused on heraldry). Fencing practice went through a revival, with the ''Marxbruder'' group, sometime about 1487 A.D. the group having formed some form of Fencing Guild.

Francisco Román published in 1532 the Tratado de la esgrima con figuras. It meant a change in the approach to fencing, with a more mathematical approach, and started a new tradition in Spanish fencing.

The Spanish rapier was apparently introduced to England during a time circa to 1540 (according to listings of the armoury of Henry the VIIIth). During 1587 a certain Rowland Yorke (of otherwise ill-repute) might have introduced a particular technique with the rapier-sword to somewhere in England.

In 1582 was finally published Jerónimo Carranza's seminal treatise De la Filosofía de las Armas y de su Destreza y la Aggression y Defensa Cristiana, one of the main works of the Spanish tradition on Verdadera Destreza. Its precepts are based on reason, geometry, and tied to intellectual, philosophical, and moral ideals, incorporating various aspects of a well-rounded Renaissance humanist education, with a special focus on the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle, Euclid or Plato. Its represents a break from an older tradition of fencing in Spain, the so-called esgrima vulgar or esgrima común ('vulgar or common fencing'). That older tradition, with roots in medieval times, was represented by the works of authors such as Jaime Pons s; ca(1474), Pedro de la Torre (1474) and Francisco Román (1532). Writers on destreza took great care to distinguish their "true art" from the "vulgar" or "common" fencing. The older school continued to exist alongside la verdadera destreza, with Spanish soldiers working as fencing masters across Europe, but was increasingly influenced by the new destreza forms and concepts.

During the 16th century the Italian masters Agrippa Agrippa may refer to:

People Antiquity

* Agrippa (mythology), semi-mythological king of Alba Longa

* Agrippa (astronomer), Greek astronomer from the late 1st century

* Agrippa the Skeptic, Skeptic philosopher at the end of the 1st century

* Agri ...

, Capo ferro, di Grassi, Fabris, Giganti, Marozzo, and Viggiani wrote treatises which established Italy as the originator of modern fencing.

By the 16th century, with the widespread adoption of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in wh ...

, the increase in the urban population and other social changes, the number of treatises increased dramatically. After around 1500 carrying swords became more acceptable in most parts of Europe. The growing middle classes meant that more men could afford to carry swords, learn fighting and be seen as gentlemen. By the middle of the 16th century many European cities contained great numbers of swordsmanship schools and fencing was invented with the invention of the rapier. Often schools clustered together, such as in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

at "Hanging Sword Lane". Italian fencing masters were particularly popular and set up schools in many foreign cities. The Italians brought concepts of science to the art, appealing to the Renaissance mindset.

In 16th-century Germany compendia of older ''Fechtbücher'' techniques were produced, some of them printed; notably by Paulus Hector Mair

Paulus Hector Mair (1517–1579) was a German civil servant fencing master from Augsburg. He collected Fechtbücher and undertook to compile all knowledge of the art of fencing in a compendium surpassing all earlier books. For this, he engaged the ...

(in the 1540s) and by Joachim Meyer

Joachim Meyer (ca. 1537–1571) was a self described Freifechter (literally, Free Fencer) living in the then Free Imperial City of Strasbourg in the 16th century and the author of a fechtbuch '' Gründtliche Beschreibung der Kunst des Fechten ...

(in the 1570s) and based on 14th-century teachings of the Liechtenauer Johannes Liechtenauer (also ''Lichtnauer'', ''Hans Lichtenawer'') was a German fencing master who had a great level of influence on the German fencing tradition in the 14th century.

Biography

Liechtenauer seems to have been active during the m ...

tradition. In this period German fencing developed sportive tendencies.

The

The rapier

A rapier () or is a type of sword with a slender and sharply-pointed two-edged blade that was popular in Western Europe, both for civilian use (dueling and self-defense) and as a military side arm, throughout the 16th and 17th centuries.

Impor ...

's popularity peaked in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Dardi school of the 1530s, as exemplified by Achille Marozzo

Achille Marozzo (1484–1553) was an Italian fencing master, one of the most important teachers in the Dardi or Bolognese tradition.Castle, Egerton (1885), ''Schools and Masters of Fenc'', Londra, G. Bell, rist. (2003) ''Schools and Masters of Fen ...

, still taught the two-handed spadone, but preferred the single–handed sword. The success of Italian masters such as Marozzo and Fabris outside of Italy shaped a new European mainstream of fencing. One master, Girolamo Cavalcabo of Bologna, was employed by the French Court to tutor the future Louis XIII in fencing, and his influence may be seen in later French treatises, such as that by François Dancie in 1623.

The ''Ecole Française d'Escrime'' founded in 1567 under Charles IX produced masters such as Henry de Sainct-Didier who introduced the French fencing terminology that remains in use today.

Rapier gave rise to the first recognisable ancestor of modern foil: a training weapon with a narrow triangular blade and a flat "nail head" point. Such a weapon (with a swept hilt and a rapier length blade) is on display at the Royal Armouries Museum

The Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England, is a national museum which displays the National Collection of Arms and Armour. It is part of the Royal Armouries family of museums, with other sites at the Royal Armouries' traditio ...

. However, the first known version of foil rules only came to be written down towards the end of the 17th century (also in France).

Early modern period

Fencing was a popular form of staged entertainment in 16th- and 17th-century England. It was also a fashionable (although somewhat controversial) martial art. In 1540

Fencing was a popular form of staged entertainment in 16th- and 17th-century England. It was also a fashionable (although somewhat controversial) martial art. In 1540 Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and for his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disa ...

granted a monopoly on the running of fencing schools in London to The Company of Masters. Fencers were specifically included in the 1597 Vagabonds Act ("all fencers, bearwards, common players of interludes, and minstrels"). A number of notable fencing masters from the late 16th century (Vincentio Saviolo

Fencing master Vincentio Saviolo (d. 1598/9), though Italian born and raised, authored one of the first books on fencing to be available in the English language.

Saviolo was born in Padua. He arrived in London at an unknown date and is first ...

, Rocco Bonetti, and William Joyner) ran schools in and around Blackfriars Blackfriars, derived from Black Friars, a common name for the Dominican Order of friars, may refer to:

England

* Blackfriars, Bristol, a former priory in Bristol

* Blackfriars, Canterbury, a former monastery in Kent

* Blackfriars, Gloucester, a f ...

(then the main theatre district of London).

Around the same time, a number of significant fencing manuals were written in or translated into English. Prizefights were bloody but rarely lethal.

Around the same time, a number of significant fencing manuals were written in or translated into English. Prizefights were bloody but rarely lethal. Samuel Pepys

Samuel Pepys (; 23 February 1633 – 26 May 1703) was an English diarist and naval administrator. He served as administrator of the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament and is most famous for the diary he kept for a decade. Pepys had no mariti ...

describes visiting at least two prizefights held in London's Beargarden

The Beargarden was a facility for bear-baiting, bull-baiting, and other "animal sports" in the London area during the 16th and 17th centuries, from the Elizabethan era to the English Restoration period. Baiting is a blood sport where an animal ...

in 1667 – the contestants were tradesmen rather than fencing masters; both fights ended after one of the contestants was unable to continue because of wrist injuries. On the whole, the English public opinion of fencing during this period was rather low; it was viewed in much the same light as cage fighting

Mixed martial arts (MMA), sometimes referred to as cage fighting, no holds barred (NHB), and ultimate fighting, and originally referred to as Vale Tudo is a full-contact combat sport based on striking, grappling and ground fighting, incorp ...

today.

An almost exclusively thrusting style first became popular in France during the 17th century. The French were enthusiastic adopters of the smallsword, which was light and short, and, therefore, well suited to fast, intricate handwork. Light, smaller training weapons were developed on the basis of an existing template: narrow rectangular blade with a "nail head" at the end. The first documented competition with rules resembling contemporary foil took place in Toulouse

Toulouse ( , ; oc, Tolosa ) is the prefecture of the French department of Haute-Garonne and of the larger region of Occitania. The city is on the banks of the River Garonne, from the Mediterranean Sea, from the Atlantic Ocean and from Par ...

in the late 17th century.

Academic and classical fencing

Brawling and fighting were regular occupations of students in the German-speaking areas during the early modern period. In line with developments in the aristocracy and the military, regulated duels were introduced to the academic environment, as well. Students wore special clothes, developed special kinds of festivities, sang student songs, and fought duels. Thefoil

Foil may refer to:

Materials

* Foil (metal), a quite thin sheet of metal, usually manufactured with a rolling mill machine

* Metal leaf, a very thin sheet of decorative metal

* Aluminium foil, a type of wrapping for food

* Tin foil, metal foil ...

was invented in France as a training weapon in the middle of the 18th century to practice fast and elegant thrust fencing. Fencers blunted the point by wrapping a foil around the blade or fastening a knob on the point ("blossom", French ''fleuret''). In addition to practising, some fencers took away the protection and used the sharp foil for duels. German students took up that practice and developed the ''Pariser'' ("Parisian") thrusting small sword for the ''Stoßmensur'' ("thrusting mensur"). After the dress sword was abolished, the ''Pariser'' became the only weapon for academic thrust fencing in Germany.

Since fencing on thrust with a sharp point is quite dangerous, many students died from their lungs being pierced (''Lungenfuchser''), which made breathing difficult or impossible. However, the counter movement had already started in Göttingen in the 1760s. Here the ''Göttinger Hieber'' was invented, the predecessor of the modern ''Korbschläger'', a new weapon for cut fencing. In the following years, the ''Glockenschläger'' was invented in east German universities for cut fencing as well.

Thrust fencing (using ''Pariser'') and cut fencing (using ''Korbschläger'' or ''Glockenschläger'') existed in parallel in Germany during the first decades of the 19th century—with local preferences. So thrust fencing was especially popular in Jena

Jena () is a German city and the second largest city in Thuringia. Together with the nearby cities of Erfurt and Weimar, it forms the central metropolitan area of Thuringia with approximately 500,000 inhabitants, while the city itself has a popu ...

, Erlangen

Erlangen (; East Franconian German, East Franconian: ''Erlang'', Bavarian language, Bavarian: ''Erlanga'') is a Middle Franconian city in Bavaria, Germany. It is the seat of the administrative district Erlangen-Höchstadt (former administrative d ...

, Würzburg

Würzburg (; Main-Franconian: ) is a city in the region of Franconia in the north of the German state of Bavaria. Würzburg is the administrative seat of the ''Regierungsbezirk'' Lower Franconia. It spans the banks of the Main River.

Würzburg is ...

and Ingolstadt

Ingolstadt (, Austro-Bavarian: ) is an independent city on the Danube in Upper Bavaria with 139,553 inhabitants (as of June 30, 2022). Around half a million people live in the metropolitan area. Ingolstadt is the second largest city in Upper Bav ...

/Landshut

Landshut (; bar, Landshuad) is a town in Bavaria in the south-east of Germany. Situated on the banks of the River Isar, Landshut is the capital of Lower Bavaria, one of the seven administrative regions of the Free State of Bavaria. It is also t ...

, two towns where the predecessors of Munich University were located. The last thrust ''Mensur'' is recorded to have taken place in Würzburg in 1860.

Until the first half of the 19th century all types of academic fencing can be seen as

Until the first half of the 19th century all types of academic fencing can be seen as duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

s, since fencing with sharp weapons was about honour. No combat with sharp blades took place without a formal insult. For duels involving non-students, e.g. military officers, the ''academic sabre'' became usual, apparently derived from the military sabre. It was then a heavy weapon with a curved blade and a hilt similar to the ''Korbschläger''.

Classical fencing

Classical fencing is the style of fencing as it existed during the 19th and early 20th centuries. According to the 19th-century fencing master Louis Rondelle,Rondelle, Louis, Foil and sabre; a grammar of fencing in detailed lessons for professo ...

derives most directly from the 19th- and early 20th-century national fencing schools, especially in Italy

Italy ( it, Italia ), officially the Italian Republic, ) or the Republic of Italy, is a country in Southern Europe. It is located in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, and its territory largely coincides with the homonymous geographical re ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, although other pre–World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

styles such as Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

n and Hungarian are also considered classical. Masters and legendary fencing figures such as Giuseppe Radaelli Giuseppe Radaelli (1833 - 1882) was a 19th-century Milanese fencing master and soldier. Often regarded as "the father of modern sabre fencing", his sabre fencing principles were popularised throughout Europe via his students such as Luigi Barbasetti ...

, Louis Rondelle, Masaniello Parise, the Greco brothers, Aldo Nadi and his rival Lucien Gaudin

Lucien Alphonse Paul Gaudin (27 September 1886 – 23 September 1934) was a French fencer. He competed in foil and in épée

The ( or , ), sometimes spelled epee in English, is the largest and heaviest of the three weapons used in the spor ...

were typical practitioners of this period.

Dueling went into sharp decline after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Training for duels, once fashionable for males of aristocratic

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At the time of the word's ...

backgrounds (although fencing masters such as Hope suggest that many people considered themselves trained from taking only one or two lessons), all but disappeared, along with the classes themselves. Fencing continued as a sport, with tournaments and championships. However, the need to actually prepare for a duel with "sharps" vanished, changing both training and technique.

Development into a sport

Domenico Angelo

Domenico Angelo (1717 Leghorn, Italy – 1802, Twickenham, England), was an Italian sword and fencing master, also known as Angelo Domenico Malevolti Tremamondo. The son of a merchant, he was the founder of the Angelo Family of fencers. He has ...

, who established a fencing academy, Angelo's School of Arms, in Carlisle House, Soho

Soho is an area of the City of Westminster, part of the West End of London. Originally a fashionable district for the aristocracy, it has been one of the main entertainment districts in the capital since the 19th century.

The area was develop ...

, London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in 1763. There, he taught the aristocracy

Aristocracy (, ) is a form of government that places strength in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats. The term derives from the el, αριστοκρατία (), meaning 'rule of the best'.

At t ...

the fashionable art of swordsmanship which they had previously had to go the continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

to learn, and also set up a riding school in the former rear garden of the house. He was fencing instructor to the Royal Family

A royal family is the immediate family of kings/queens, emirs/emiras, sultans/ sultanas, or raja/ rani and sometimes their extended family. The term imperial family appropriately describes the family of an emperor or empress, and the term ...

. With the help of artist Gwyn Delin, he had an instruction book published in England in 1763 which had 25 engraved plates demonstrating classic positions from the old schools of fencing. His school was run by three generations of his family and dominated the art of European fencing for almost a century.

He established the essential rules of posture

Posture or posturing may refer to:

Medicine

* Human position

** Abnormal posturing, in neurotrauma

** Spinal posture

** List of human positions

* Posturography Posturography is the technique used to quantify postural control in upright stance in ...

and footwork that still govern modern sport fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the Foil (fencing), foil, the épée, and the Sabre (fencing), sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an ...

, although his attacking and parry

PARRY was an early example of a chatbot, implemented in 1972 by psychiatrist Kenneth Colby.

History

PARRY was written in 1972 by psychiatrist Kenneth Colby, then at Stanford University. While ELIZA was a tongue-in-cheek simulation of a Rogeria ...

ing methods were still much different from current practice. Although he intended to prepare his students for real combat, he was the first fencing master yet to emphasize the health

Health, according to the World Health Organization, is "a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity".World Health Organization. (2006)''Constitution of the World Health Organiza ...

and sporting benefits of fencing more than its use as a killing art, particularly in his influential book ''L’École des armes'' (''The School of Fencing''), published in 1763. According to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', "Angelo was the first to emphasize fencing as a means of developing health, poise, and grace. As a result of his insight and influence, fencing changed from an art of war to a sport."

As fencing progressed, the combat aspect slowly faded until only the rules of the

As fencing progressed, the combat aspect slowly faded until only the rules of the sport

Sport pertains to any form of Competition, competitive physical activity or game that aims to use, maintain, or improve physical ability and Skill, skills while providing enjoyment to participants and, in some cases, entertainment to specta ...

remained. While the fencing taught in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was intended to serve both for competition and the duel

A duel is an arranged engagement in combat between two people, with matched weapons, in accordance with agreed-upon Code duello, rules.

During the 17th and 18th centuries (and earlier), duels were mostly single combats fought with swords (the r ...

(while understanding the differences between the two situations), the type of fencing taught in a modern sport fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the Foil (fencing), foil, the épée, and the Sabre (fencing), sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an ...

salle is intended only to train the student to compete in the most effective manner within the rules of the sport.

The first regularized fencing competition was held at the inaugural Grand Military Tournament and Assault at Arms in 1880, held at the Royal Agricultural Hall

The Business Design Centre is a Grade II listed building located between Upper Street and Liverpool Road in the district of Islington in London, England. It was opened in 1862, originally named the Agricultural Hall and from 1884 the Royal Agri ...

, in Islington

Islington () is a district in the north of Greater London, England, and part of the London Borough of Islington. It is a mainly residential district of Inner London, extending from Islington's High Street to Highbury Fields, encompassing the ar ...

in June. The Tournament featured a series of competitions between army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

officers and soldiers. Each bout was fought for five hits and the foils were pointed with black to aid the judges. In the United States, the Amateur Fencers League of America drew up a rulebook for fencing in 1891,; in Britain the Amateur Gymnastic & Fencing Association drew up an official set of fencing regulations in 1896.

Olympic event

Only Foil and Sabre events were part of the firstOlympic Games

The modern Olympic Games or Olympics (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques) are the leading international sporting events featuring summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a var ...

in the summer of 1896.FIE HistoryFencing history

(accessed 21 Jan 2016) Épée was introduced in 1900 (Paris). Foil was omitted from the 1908 (London) Olympics, but since 1912, fencing events for every weapon—Foil, Épée and Sabre—have been held at every

Summer Olympics

The Summer Olympic Games (french: link=no, Jeux olympiques d'été), also known as the Games of the Olympiad, and often referred to as the Summer Olympics, is a major international multi-sport event normally held once every four years. The inau ...

.

Women's foil was first competed at the Olympics in 1924 in Paris.

The (so called) 'advanced weapons', Épée and Sabre deemed unsuitable or inappropriate for women, were not included in the Olympic program until late in the 20th century. Women's Épée events were first introduced in 1996 (Atlanta) Olympics and Women's Sabre events in 2000 (Sydney).

In the early years of competition fencing, four judges determined whether a touch had been made. Two side judges stood behind and beside each fencer, watching for hits made by that fencer. A director observed from several metres away. At the end of each action, the director called "Halt," described the action, and then polled the judges. If the judges differed, or abstained, the director could overrule. The Director (also referred to head referee) always has the final say. What he says goes. The only way for a call to be changed is for one of the competitors to ask for a review (protest). If the Director acknowledged his own error, he may change the call.

Though it was universally used, this method had serious limitations. This is described by the London newspaper, the '' Daily Telegraph & Courier'', on June 25, 1896:

On Tuesday night, a 10 Warwick Street, Regent Street, the Salle d’Armes of the veteran fencing-master M. Bertrand, an exhibition was given of an exceedingly clever invention. Every one who has watched a bout with the foils knows that the task of judging the hits is with a pair of amateurs difficult enough, and with a well-matched pair of maîtres d’escrime well-nigh impossible... The invention is the work of Mr. Little, the well-known amateur swordsman, and is designed to do away with this uncertainty and useless expenditure of energy. It is hardly necessary to say that the inventor has called electricity to his aid. Briefly, the invention consists of an automatic electric recorder. The instrument is fastened to the wall and connected with the collar of the combatant, from whence the current is conveyed down the sleeve into the handle of the foil. The blade of the foil pressing into the handle completes the connection; the current is conveyed to a bell in the instrument, and thus each hit is recorded. At the exhibition the invention proved an unalloyed success, and ought to be a boon both to competitors and judges—to the former on account of its certainty, and to the latter because it not only lightens their labours, but also frees them from any suspicion of partiality."There also were problems with bias: well–known fencers were often given the benefit of mistakes (so–called "reputation touches"), and in some cases there was outright cheating. Aldo Nadi complained about this in his autobiography ''

The Living Sword

Aldo Nadi (29 April 1899 – 10 November 1965) was one of the greatest Italian fencers of all time.

Biography

Aldo was born into a fencing family in Livorno, Italy, and both Aldo and his brother Nedo Nadi were fencers from a very young age. T ...

'' in regard to his famous match with Lucien Gaudin

Lucien Alphonse Paul Gaudin (27 September 1886 – 23 September 1934) was a French fencer. He competed in foil and in épée

The ( or , ), sometimes spelled epee in English, is the largest and heaviest of the three weapons used in the spor ...

. The ''Daily Courier'' article described a new invention, the electrical scoring machine, that would revolutionize fencing.

Starting with épée

The ( or , ), sometimes spelled epee in English, is the largest and heaviest of the three weapons used in the sport of fencing. The modern derives from the 19th-century , a weapon which itself derives from the French small sword. This contains ...

in 1933, side judges were replaced by the Laurent-Pagan electrical scoring apparatus, with an audible tone and a red or green light indicating when a touch landed. Foil

Foil may refer to:

Materials

* Foil (metal), a quite thin sheet of metal, usually manufactured with a rolling mill machine

* Metal leaf, a very thin sheet of decorative metal

* Aluminium foil, a type of wrapping for food

* Tin foil, metal foil ...

was automated in 1956, sabre

A sabre ( French: �sabʁ or saber in American English) is a type of backsword with a curved blade associated with the light cavalry of the early modern and Napoleonic periods. Originally associated with Central European cavalry such as th ...

in 1988. The scoring box reduced the bias in judging, and permitted more accurate scoring of faster actions, lighter touches, and more touches to the back and flank than before.

Historical Schools

Venetian school of fencing

The Venetian school of fencing is a style of fencing that occurred in Venice in the early 12th century, and prevailed until the beginning of the 19th century.Школы и мастера фехтования. Благородное искусство владения клинком, Эгертон Кастл, Litres, 12 янв. 2017 г. – Всего страниц: 7632 The basics of the Venetian fencing are expounded in the following five treatises: * Giacomo di Grassi "The Reasons of Victorious Weapon Handling for Attack and Defense" (1570); * Francesco Alfieri “The Art of Excellent Handling of the Sword” (1653); * Camillo Agrippa "The Treatise on the Science of Weapons with Philosophical Reflections" (1553); * Nicoletto Giganti “School or Theater” (1606); * Salvator Fabris "Fencing or the science of weapons" (1606) The Venetians were masters of the art, and shared with their colleagues of Bologna the sound principles of fencing known as Bolognese or Venetian. For the first time Venetian fencing was detailed in some directions, it was described the properties of different parts of the blade, which were used in defense and offense. With this approach, the swordsman had an idea of one thing, what now we calling like "center of percussion". It was suggested some divisions of a sword. The blade was divided into four parts, the first two parts from Ephesus should be used for protection; the third one near the center of the blow was used for striking; and the fourth part at the tip was used for pricking.German school of fencing

The German school of fencing is a historical combat system, a style of fencing that was widespread in the Holy Roman Empire and existed in the late Middle Ages, Renaissance and early Modern times (from the end of XIV to XVII century). The first document of the German heritage, which describes the methods of fencing, is considered to be the Manuscript I.33 which was written around 1300.Neapolitan fencing school

Neapolitan fencing is a style of fencing that originated in the city of Naples at the beginning of the 15th century. Neapolitan Fencing School is considered to be one of the most powerful fencing schools in Italy.Mensur

Fencing has a long history with universities and schools for at least 500 years. At least one style of fencing,Mensur

Academic fencing (german: link=no, akademisches Fechten) or is the traditional kind of fencing practiced by some student corporations () in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Latvia, Estonia, and, to a minor extent, in Belgium, Lithuania, and Pol ...

in Germany, is practiced only within academic fraternities.

Mounted Service School

Prior to advances in modern weaponry post World War I, theUnited States Cavalry

The United States Cavalry, or U.S. Cavalry, was the designation of the mounted force of the United States Army by an act of Congress on 3 August 1861.Price (1883) p. 103, 104 This act converted the U.S. Army's two regiments of dragoons, one ...

taught swordsmanship (mounted and dismounted) in Fort Riley

Fort Riley is a United States Army installation located in North Central Kansas, on the Kansas River, also known as the Kaw, between Junction City and Manhattan. The Fort Riley Military Reservation covers 101,733 acres (41,170 ha) in Gear ...

, Kansas at its Mounted Service School

The United States Army Cavalry School was part of a series of training programs and centers for its horse mounted troops or cavalry branch.

History

In 1838, a Cavalry School of Practice was established at Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, which i ...

. George S. Patton Jr.

George Smith Patton Jr. (November 11, 1885 – December 21, 1945) was a General (United States), general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations, Mediterranean Theater ...

, while still a young lieutenant, was named " Master of the Sword," an honor reserved for the top instructor. He invented what came to be known as the "Patton Saber," in 1913, based on his studies with M. Clery L'Adjutant, reputed to be the finest Fencing Master in Europe at the time. While teaching at Fort Riley, he wrote two training manuals teaching the art of swordsmanship to Army Cavalry Officers, "Saber Exercise 1914" and "Diary of the Instructor in Swordsmanship."Patton, George S. Jr. "Diary of the Instructor in Swordsmanship." Silver Spring, MD: Dale Street Books, 2016.

See also

*History of martial arts

Although the earliest evidence of martial arts goes back millennia, the true roots are difficult to reconstruct. Inherent patterns of human aggression which inspire practice of mock combat (in particular wrestling) and optimization of serious close ...

* History of physical training and fitness

Physical training has been present in human societies throughout history. Usually, it was performed for the purposes of preparing for physical competition or display, improving physical, emotional and mental health, and looking attractive. It ...

References

{{History of sports FencingFencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, s ...

Fencing

Fencing is a group of three related combat sports. The three disciplines in modern fencing are the foil, the épée, and the sabre (also ''saber''); winning points are made through the weapon's contact with an opponent. A fourth discipline, s ...