Historiography of the Battle of France on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The historiography of the Battle of France describes how the German victory over French and British forces in the

The historiography of the Battle of France describes how the German victory over French and British forces in the

Tanks Break Through in Library of Congress Catalog

/ref>

Mungo Melvin (2001) wrote that German writing on the 1940 campaign sought answers to various questions,

Melvin wrote that Germans writing in 1940 showed apprehension rather than confidence. German army officers were astonished by the swiftness of the victory, the French collapse and the British escape. Later historians have hindsight and British writers can make much of Dunkirk but German writers take the view that although it was a big operational and perhaps strategic blunder, this could not be blamed on a German failure to have formed a concept of the war; Dunkirk might not have been decisive but was a fatal blow to German strategy. Melvin called the German victory a "stunning operational success"; the Germans had exploited Allied mistakes and recovered from theirs, despite the tensions in the German high command.

Mungo Melvin (2001) wrote that German writing on the 1940 campaign sought answers to various questions,

Melvin wrote that Germans writing in 1940 showed apprehension rather than confidence. German army officers were astonished by the swiftness of the victory, the French collapse and the British escape. Later historians have hindsight and British writers can make much of Dunkirk but German writers take the view that although it was a big operational and perhaps strategic blunder, this could not be blamed on a German failure to have formed a concept of the war; Dunkirk might not have been decisive but was a fatal blow to German strategy. Melvin called the German victory a "stunning operational success"; the Germans had exploited Allied mistakes and recovered from theirs, despite the tensions in the German high command.

In 1956, the English historian

In 1956, the English historian

In 2000, American scholar

In 2000, American scholar  May wrote that when Hitler demanded a plan to invade France in September 1939, the German officer corps thought that it was foolhardy and discussed a

May wrote that when Hitler demanded a plan to invade France in September 1939, the German officer corps thought that it was foolhardy and discussed a  May wrote that French and British rulers were at fault for tolerating poor performance by the intelligence agencies and that the Germans could achieve surprise in May 1940, showed that even with Hitler, the process of executive judgement in Germany had worked better than in France and Britain. Allied politicians showed far less common sense in judging circumstances and deciding on policy but the Germans were no wiser. May referred to Marc Bloch in ''Strange Defeat'' (1940), that the German victory was a "triumph of intellect", which depended on Hitler's "methodical opportunism". Despite the mistakes of the Allies, May wrote that the Germans could not have succeeded but for outrageous good luck. German commanders wrote during the campaign and after, that often only a small difference had separated success from failure. Prioux thought that a counter-offensive could still have worked up to 19 May but by then, Belgian refugees were crowded on the roads needed for redeployment and the French transport units, that had performed well in the advance into Belgium, failed for lack of plans to move them back. Maurice Gamelin had said "It is all a question of hours." but the decision to sack Gamelin and appoint Weygand, caused a delay of two days.

May wrote that French and British rulers were at fault for tolerating poor performance by the intelligence agencies and that the Germans could achieve surprise in May 1940, showed that even with Hitler, the process of executive judgement in Germany had worked better than in France and Britain. Allied politicians showed far less common sense in judging circumstances and deciding on policy but the Germans were no wiser. May referred to Marc Bloch in ''Strange Defeat'' (1940), that the German victory was a "triumph of intellect", which depended on Hitler's "methodical opportunism". Despite the mistakes of the Allies, May wrote that the Germans could not have succeeded but for outrageous good luck. German commanders wrote during the campaign and after, that often only a small difference had separated success from failure. Prioux thought that a counter-offensive could still have worked up to 19 May but by then, Belgian refugees were crowded on the roads needed for redeployment and the French transport units, that had performed well in the advance into Belgium, failed for lack of plans to move them back. Maurice Gamelin had said "It is all a question of hours." but the decision to sack Gamelin and appoint Weygand, caused a delay of two days.

In 2006, Tooze wrote that the German success could not be attributed to a great superiority in the machinery of

In 2006, Tooze wrote that the German success could not be attributed to a great superiority in the machinery of

Doughty noted that the 55th, 53rd and 71st Infantry divisions had collapsed at Sedan under little pressure from the Germans but that this was not a matter of French decadence but of soldiers being individuals within a group, which fights according to doctrine and strategy in the spirit by which they are led. The French divisions suffered from poor organisation, doctrine, training, leadership and a lack of confidence in their weapons, which would have caused any unit to fail. From Luxembourg to Dunkirk, the XIX Panzer Corps had 3,845 (7.0 percent) casualties, 640 (1.2 percent) killed and 3,205 men wounded (5.8 percent) of about 55,000 men. Of 1,500 officers, 53 (3.5 percent) were killed and 241 (16.1 percent) were wounded. The French Second Army had 12 percent casualties, from 3–4 percent killed and from 8–9 percent wounded. The German force had a far greater number of officer casualties and were able to keep fighting, because other officers could take over. The contrasting methods of command flowed from the rival armies' theories of war, the French system being a management of men and equipment model and the German system relying on rapid decision and personal influence at the decisive point in a mobile battle. By 16 May, the French army had been brought to the brink of collapse.

Doughty noted that the 55th, 53rd and 71st Infantry divisions had collapsed at Sedan under little pressure from the Germans but that this was not a matter of French decadence but of soldiers being individuals within a group, which fights according to doctrine and strategy in the spirit by which they are led. The French divisions suffered from poor organisation, doctrine, training, leadership and a lack of confidence in their weapons, which would have caused any unit to fail. From Luxembourg to Dunkirk, the XIX Panzer Corps had 3,845 (7.0 percent) casualties, 640 (1.2 percent) killed and 3,205 men wounded (5.8 percent) of about 55,000 men. Of 1,500 officers, 53 (3.5 percent) were killed and 241 (16.1 percent) were wounded. The French Second Army had 12 percent casualties, from 3–4 percent killed and from 8–9 percent wounded. The German force had a far greater number of officer casualties and were able to keep fighting, because other officers could take over. The contrasting methods of command flowed from the rival armies' theories of war, the French system being a management of men and equipment model and the German system relying on rapid decision and personal influence at the decisive point in a mobile battle. By 16 May, the French army had been brought to the brink of collapse.

online

Bibliography, pp 265–83. * * * de Konkoly Thege, Michel Marie. (2015) "Paul Reynaud and the Reform of France's Economic, Military and Diplomatic Policies of the 1930s." (Graduate Liberal Studies Works (MALS/MPhil). Paper 6, 2015)

online

bibliography pp 171–76. * Doughty, Robert Allan. (1985) ''The Seeds of Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919–1939'' (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1985) * * * Fishman, Sarah; Lake, David. (2000) ''France at War: Vichy & the Historians'' (2000). * Gunsberg, Jefferey. (1979) ''Divided and Conquered: The French High Command and the Defeat of the West, 1940'' (Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 1979). * * * Higham, Robin. (2012) ''Two Roads to War: The French and British Air Arms from Versailles to Dunkirk'' (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2012

online

* * Imlay, Talbot C. "Strategies, Commands, and Tactics, 1939–1941." in Thomas W. Zeiler and Daniel M. DuBois, eds. ''A Companion to World War II'' (2013) 2: 415–32. * * * * *

online

* * Nord, Philip. (2015) ''France 1940: Defending the Republic'' (Yale UP, 2015). * * * Shennan, Andrew. (2000) ''The Fall of France, 1940'' (2000)

Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

had been explained by historians and others. Many people in 1940 found the fall of France unexpected and earth shaking. Alexander notes that Belgium and the Netherlands fell to the German army in a matter of days and the British were soon driven back to the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles, ...

,

Contemporary comment

While the French armies were being defeated, the government turned to elderly warriors from the First World War. At a time many civilians felt there must be a wicked conspiracy afoot, these new leaders blamed a leftist culture inculcated by the schools for the failure, a theme that has repeatedly appeared in conservative commentary since 1940. GeneralMaxime Weygand

Maxime Weygand (; 21 January 1867 – 28 January 1965) was a French military commander in World War I and World War II.

Born in Belgium, Weygand was raised in France and educated at the Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris. After graduating in 1 ...

said as he took over in May 1940, "What we are paying for is twenty years of blunders and neglect. It is out of the question to punish the generals and not the teachers who have refused to develop in the children the sense of patriotism and sacrifice." He also claimed that reserve officers who abandoned their units were the products of "teachers who were Socialists and not patriots". The new national dictator of Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

, Marshal Philippe Pétain

Henri Philippe Benoni Omer Pétain (24 April 1856 – 23 July 1951), commonly known as Philippe Pétain (, ) or Marshal Pétain (french: Maréchal Pétain), was a French general who attained the position of Marshal of France at the end of World ...

, had his explanation: "Our defeat is punishment for our moral failures. The mood of sensual pleasure destroyed what the spirit of sacrifice had built up".

Early studies

From Lemberg to Bordeaux (1941)

''From Lemberg to Bordeaux

Leo Leixner (1908–1942) was an Austrian journalist and war correspondent. He is known for his boo''From Lemberg to Bordeaux'' a first-hand account of war in Poland, the Low Countries, and France, 1939–40, during World War II.

Early life and e ...

: A German War Correspondent’s Account of Battle in Poland, the Low Countries and France, 1939–40'' was written by Leo Leixner

Leo Leixner (1908–1942) was an Austrian journalist and war correspondent. He is known for his boo''From Lemberg to Bordeaux'' a first-hand account of war in Poland, the Low Countries, and France, 1939–40, during World War II.

Early life and e ...

, a journalist and war correspondent. The book is a witness account of the battles that led to the fall of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week afte ...

and France. In August 1939, Leixner joined the Wehrmacht as a war reporter, was promoted to sergeant and in 1941 published his recollections. The book was originally issued by Franz Eher Nachfolger

Franz Eher Nachfolger GmbH (''Franz Eher and Successors, LLC'', usually referred to as the Eher-Verlag (''Eher Publishing'')) was the central publishing house of the Nazi Party and one of the largest book and periodical firms during the Third Rei ...

, the central publishing house of the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

.

Tanks Break Through! (1940)

''Tanks Break Through!

Alfred-Ingemar Berndt (22 April 1905 – 28 March 1945) was a German Nazi journalist, writer and close collaborator of Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels.

Berndt joined the Nazi Party at the age of 18 and became ...

'' (''Panzerjäger Brechen Durch!''), written by Alfred-Ingemar Berndt

Alfred-Ingemar Berndt (22 April 1905 – 28 March 1945) was a German Nazi journalist, writer and close collaborator of Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda Joseph Goebbels.

Berndt joined the Nazi Party at the age of 18 and became ...

, a journalist and close associate of propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

, is a witness account of the battles that led to the fall of France. When the 1940 attack was in the offing, Berndt joined the Wehrmacht, was sergeant in an anti-tank

Anti-tank warfare originated from the need to develop technology and tactics to destroy tanks during World War I. Since the Triple Entente deployed the first tanks in 1916, the German Empire developed the first anti-tank weapons. The first deve ...

division and afterwards published his recollections. The book was originally issued by Franz Eher Nachfolger

Franz Eher Nachfolger GmbH (''Franz Eher and Successors, LLC'', usually referred to as the Eher-Verlag (''Eher Publishing'')) was the central publishing house of the Nazi Party and one of the largest book and periodical firms during the Third Rei ...

, the central publishing house of the Nazi Party, in 1940./ref>

''Strange Defeat'' (1940)

''L'Etrange Defaite temoignage ecrit en 1940'' (Strange Defeat

''Strange Defeat'' (french: L'Étrange Défaite) is a book written in the summer of 1940 by French historian Marc Bloch. The book was published in 1946; in the meanwhile, Bloch had been tortured and executed by the Gestapo in June 1944 for his pa ...

: A Statement of Evidence Written in 1940) was an account written by the Medieval historian Marc Bloch

Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch (; ; 6 July 1886 – 16 June 1944) was a French historian. He was a founding member of the Annales School of French social history. Bloch specialised in medieval history and published widely on Medieval France ov ...

and published posthumously in 1946. Bloch raised most of the issues historians have debated since and he blamed French leadership,

Guilt was widespread; Carole Fink wrote that Bloch

French interpretations

Martin Alexander (2001) wrote that many early French writers followed Bloch, asking why the French people accepted and even welcomed the defeat of the Third Republic. In ''The French Defeat of 1940: Reassessments'' (1997),Stanley Hoffman

Stanley Hoffmann (27 November 1928 – 13 September 2015) was a French political scientist and the Paul and Catherine Buttenwieser University Professor at Harvard University, specializing in French politics and society, European politics, U. ...

, a Frenchman who taught political science at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

, wrote that there was no "1940 syndrome". The syndrome was a hypothetical counterpart to "Vichy syndrome" described in the 1980s by Henry Rousso Henry Rousso (born 23 November 1954) is an Egyptian-born French historian specializing in World War II France.

Early life

Henry Rousso was born on 23 November 1954 in Cairo, Egypt to a Jewish family. Forced out of Egypt under anti-Semitic measures ...

and with "colonial

Colonial or The Colonial may refer to:

* Colonial, of, relating to, or characteristic of a colony or colony (biology)

Architecture

* American colonial architecture

* French Colonial

* Spanish Colonial architecture

Automobiles

* Colonial (1920 au ...

syndrome" caused by the exposure of French atrocities in Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, relig ...

. French historians

This is a list of French historians limited to those with a biographical entry in either English or French Wikipedia. Major chroniclers, annalists, philosophers, or other writers are included, if they have important historical output. Names are lis ...

had shown little interest in the military events from April to June 1940, being more interested in the consequences, particularly the establishment of the Vichy regime in July 1940. Overlooked accounts of the campaign by participants, portrayed brave, puzzled French soldiers but the definitive history of the war fought by the fighting men had yet to be written. Alexander called the British and French in 1940 "neighbouring nations conducting a war in parallel rather than as one unified endeavour" and wrote that the relationship between the national histories was similar, parallel myths and literatures had come about and continued sixty years on.

German interpretations

Mungo Melvin (2001) wrote that German writing on the 1940 campaign sought answers to various questions,

Melvin wrote that Germans writing in 1940 showed apprehension rather than confidence. German army officers were astonished by the swiftness of the victory, the French collapse and the British escape. Later historians have hindsight and British writers can make much of Dunkirk but German writers take the view that although it was a big operational and perhaps strategic blunder, this could not be blamed on a German failure to have formed a concept of the war; Dunkirk might not have been decisive but was a fatal blow to German strategy. Melvin called the German victory a "stunning operational success"; the Germans had exploited Allied mistakes and recovered from theirs, despite the tensions in the German high command.

Mungo Melvin (2001) wrote that German writing on the 1940 campaign sought answers to various questions,

Melvin wrote that Germans writing in 1940 showed apprehension rather than confidence. German army officers were astonished by the swiftness of the victory, the French collapse and the British escape. Later historians have hindsight and British writers can make much of Dunkirk but German writers take the view that although it was a big operational and perhaps strategic blunder, this could not be blamed on a German failure to have formed a concept of the war; Dunkirk might not have been decisive but was a fatal blow to German strategy. Melvin called the German victory a "stunning operational success"; the Germans had exploited Allied mistakes and recovered from theirs, despite the tensions in the German high command.

Fuller (1956)

J. F. C. Fuller

Major-General John Frederick Charles "Boney" Fuller (1 September 1878 – 10 February 1966) was a senior British Army officer, military historian, and strategist, known as an early theorist of modern armoured warfare, including categorising pr ...

called the military operations on the Meuse in 1940, "the Second Battle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War from 1 to 2 September 1870. Resulting in the capture of Emperor Napoleon III and over a hundred thousand troops, it effectively decided the war in favour of Prussia and its allies, ...

". Fuller called the German operation an ''attack by paralyzation'' but Robert Doughty wrote that what some writers later called blitzkrieg

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air su ...

had influenced few German officers, except for Guderian Guderian is a German surname. Other spellings are ''Guderjahn'' and ''Guderjan''. It is present in Greater Poland and Mazovia in the 19th century. Notable people with the surname include:

*Heinz Guderian, Heinz Wilhelm Guderian (1888–1954), Germa ...

and Manstein and that the dispute between Guderian and Kleist Kleist, or von Kleist, is a surname.

von Kleist:

*August von Kleist (1818–1890), Prussian Major General

*Conrad von Kleist (1839-1900), German politician (German Conservative Party), member of Reichstag

*Ewald Georg von Kleist (ca. 1700–1748), ...

that led Guderian to resign on 17 May, showed the apprehensions of the higher commanders about the "pace and vulnerability" of the XIX Panzer Corps. Doughty wrote that the development of the German plan suggested that sending armoured forces through the Ardennes was traditional ''Vernichtungsstrategie'' ( strategy of annihilation), to encircle opposing forces and destroy them in a ''Kesselschlacht'' (cauldron

A cauldron (or caldron) is a large pot (kettle) for cooking or boiling over an open fire, with a lid and frequently with an arc-shaped hanger and/or integral handles or feet. There is a rich history of cauldron lore in religion, mythology, and ...

battle). Weapons had changed but the methods were the same as those at Ulm

Ulm () is a city in the German state of Baden-Württemberg, situated on the river Danube on the border with Bavaria. The city, which has an estimated population of more than 126,000 (2018), forms an urban district of its own (german: link=no, ...

(1805), Sedan (1870) and Tannenberg (1914).

Fuller had also written that the German army was an armoured battering-ram, covered by fighters and dive-bombers working as flying artillery, which broke through at several points. Doughty wrote that the XIX, XLI and XV Panzer corps had been the vanguard of the advance through the Ardennes

The Ardennes (french: Ardenne ; nl, Ardennen ; german: Ardennen; wa, Årdene ; lb, Ardennen ), also known as the Ardennes Forest or Forest of Ardennes, is a region of extensive forests, rough terrain, rolling hills and ridges primarily in Be ...

but the most determined French resistance at Bodange, the mushroom of Glaire

Glaire () is a commune in the Ardennes department in northern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Ardennes department

The following is a list of the 449 communes of the Ardennes department of France.

The communes cooperate ...

, Vendresse

Vendresse () is a commune in the Ardennes department and Grand Est region of north-eastern France.

Population

The inhabitants of Vendresse are known as ''Vendressois''.

Sights

*Arboretum de Vendresse

See also

*Communes of the Ardennes de ...

, La Horgne and Bouvellement, had been defeated by the combined attacks of infantry, artillery and tanks. The XIX Panzer Corps had only acted as a battering ram against the French covering forces in the Ardennes. Only long after 1940 was the importance of German infantry fighting and of combined operations

In current military use, combined operations are operations conducted by forces of two or more allied nations acting together for the accomplishment of a common strategy, a strategic and operational and sometimes tactical cooperation. Interactio ...

south and to the south-west of Sedan recognised. Doughty also wrote that Fuller was wrong about the role of the ''Luftwaffe'', which had not operated as flying artillery because German ground forces depended on conventional artillery. German bombing around Sedan on 13 May had managed to deplete the morale of the French 55th Division and ground attacks had helped to force on the ground advance but French bunkers were captured by hard infantry fighting, supported by direct-fire artillery and tanks, not destroyed by bombs; only two tanks of the French Second Army

The Second Army (french: IIe Armée) was a field army of the French Army during World War I and World War II. The Army became famous for fighting the Battle of Verdun in 1916 under Generals Philippe Pétain and Robert Nivelle.

Commanders

World ...

were reported destroyed by aircraft.

Recent analyses

May (2000)

Ernest R. May

Ernest Richard May (November 19, 1928 – June 1, 2009) was an American historian of international relations, whose 14 published books include analyses of American involvement in World War I and the causes of the Fall of France during World War ...

argued that Hitler had a better insight into the French and British governments than vice versa and knew that they would not go to war over Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

and Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, because he concentrated on politics rather than the state and national interest. From 1937 to 1940, Hitler stated his views on events, their importance and his intentions, then defended them against contrary opinion from the likes of Ludwig Beck

Ludwig August Theodor Beck (; 29 June 1880 – 20 July 1944) was a German general and Chief of the German General Staff during the early years of the Nazi regime in Germany before World War II. Although Beck never became a member of the Na ...

, the German army chief of staff until August 1938 and Ernst von Weizsäcker

Ernst Heinrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker (25 May 1882 – 4 August 1951) was a German naval officer, diplomat and politician. He served as State Secretary at the Foreign Office of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1943, and as its Ambassador t ...

the ''Staatssekretär'' (State Secretary, the deputy Foreign Minister). Hitler sometimes concealed aspects of his thinking but he was unusually frank about what came first and his assumptions. May referred to Wheeler-Bennett (1964),

and that in Paris, London and other capitals, there was an inability to believe that someone might ''want'' another world war. Given public reluctance to contemplate another war and a need to conciliate more centres of power, to reach consensus about Germany. The rulers of France and Britain were ''reticent'', which limited dissent at the cost of enabling assumptions that suited their convenience. In France, French Prime Minister Daladier withheld information until the last moment, then presented the cabinet a fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman Conquest, before the language settled into what became Modern Engli ...

in September 1938 over the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, Germany, the United Kingdom, French Third Republic, France, and Fa ...

, to avoid discussion over whether Britain would follow France into war or if the military balance was really in Germany's favour or how significant it was. The decision for war in September 1939 and the plan devised in the winter of 1939–1940 by Daladier for possible war with the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, followed the same pattern.

Hitler miscalculated Franco-British reactions to the invasion of Poland in September 1939, because he had not realised that a watershed in public opinion had occurred in mid-1939. May also wrote that the French and British could have defeated Germany in 1938 with Czechoslovakia as an ally and also in late 1939, when German forces in the west were incapable of preventing a French occupation of the Ruhr

The Ruhr ( ; german: Ruhrgebiet , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr area, sometimes Ruhr district, Ruhr region, or Ruhr valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 2,800/km ...

, which would force a capitulation or a futile German resistance in a war of attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from ...

. France did not invade Germany in 1939, because it wanted British lives to be at risk too and because of hopes that a blockade might force a German surrender without a bloodbath. The French and British also believed that they were militarily superior and guaranteed victory through the blockade or by desperate German attacks. The run of victories enjoyed by Hitler from 1938–1940, could only be understood in the context of defeat being inconceivable to French and British leaders.

coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

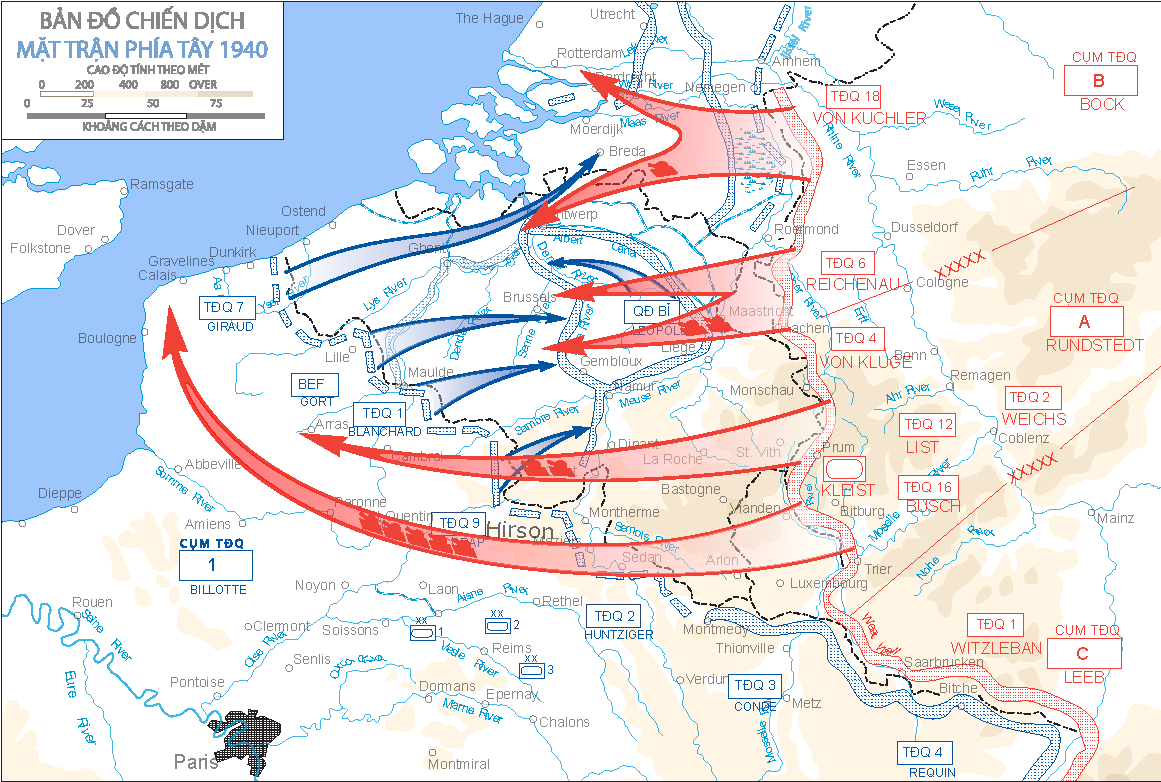

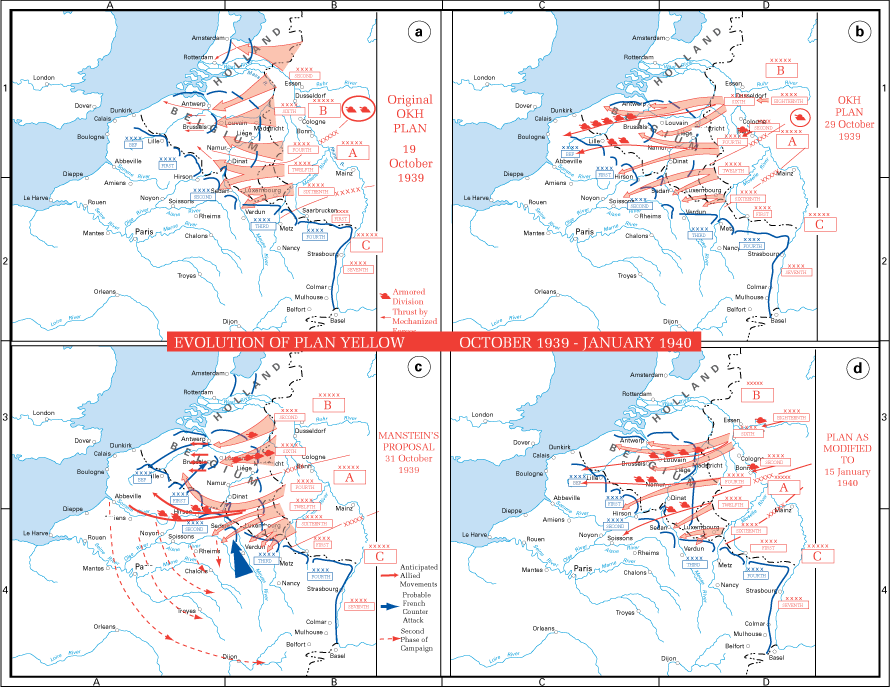

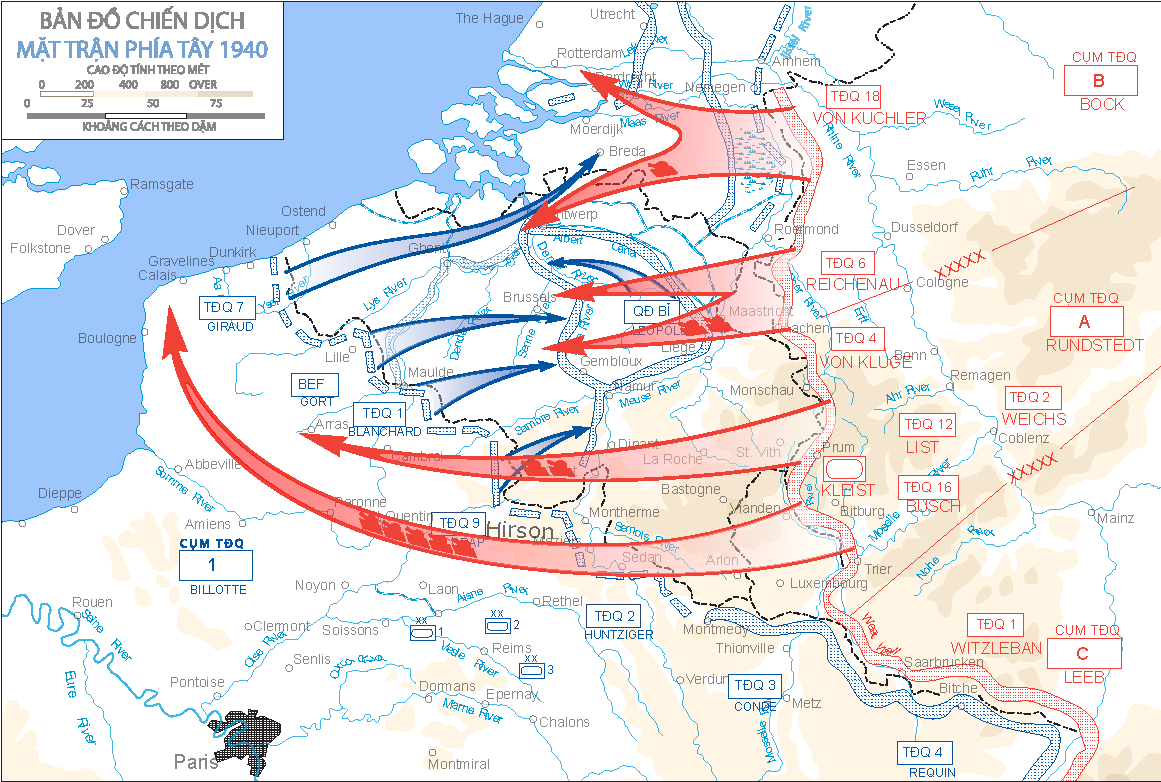

, only backing down when doubtful of the loyalty of the soldiers to them. With the deadline for the attack on France being postponed so often, OKH

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat at ...

had time to revise ''Fall Gelb

The Manstein Plan or Case Yellow (german: Fall Gelb) also known as Operation Sichelschnitt (german: Sichelschnittplan, from the English language, English term sickle cut), was the Military operation plan, war plan of the German Army (Wehrmacht), ...

'' (Case Yellow) for an invasion over the Belgian

Belgian may refer to:

* Something of, or related to, Belgium

* Belgians, people from Belgium or of Belgian descent

* Languages of Belgium, languages spoken in Belgium, such as Dutch, French, and German

*Ancient Belgian language, an extinct languag ...

Plain several times. In January 1940, Hitler came close to ordering the invasion but was prevented by bad weather. Until the Mechelen Incident

The Mechelen incident of 10 January 1940, also known as the Mechelen affair, took place in Belgium during the Phoney War in the first stages of World War II. A German aircraft with an officer on board carrying the plans for ''Fall Gelb'' (Case Ye ...

in January forced a fundamental revision of ''Fall Gelb'', the main effort (''schwerpunkt

Blitzkrieg ( , ; from 'lightning' + 'war') is a word used to describe a surprise attack using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with close air s ...

'') of the German army in Belgium would have been confronted by first-rate French and British forces, equipped with more and better tanks and with a great advantage in artillery. After the Mechelen Incident, OKH devised an alternative and hugely risky plan to make the invasion of Belgium a decoy, with the main effort switched to the Ardennes, to cross the Meuse and reach the Channel coast. May wrote that the alternative plan has been called the Manstein Plan

(Case Yellow), the invasion of France and the Low Countries

, scope = Strategic

, type =

, location = South-west Netherlands, central Belgium, northern France

, coordinates =

, planned = 1940

, planned_by = Erich von ...

but that Guderian, Manstein, Rundstedt, Halder and Hitler had been equally important in its creation.

War games held by ''Generalmajor'' (Major-General) Kurt von Tippelskirch

__NOTOC__

Kurt Oskar Heinrich Ludwig Wilhelm von Tippelskirch (9 October 1891 – 10 May 1957) was a general in the Wehrmacht of Nazi Germany during World War II who commanded several armies and Army Group Vistula. He surrendered to the United S ...

, the chief of army intelligence and Oberst Ulrich Liss of ''Fremde Heere West'' (FHW, Foreign Armies West), tested the concept of an offensive through the Ardennes. Liss thought that swift reactions could not be expected from the "systematic French or the ponderous English" and used French and British methods, which made no provision for surprise and reacted slowly, when one was sprung. The results of the war games persuaded Halder that the Ardennes scheme could work, even though he and many other commanders still expected it to fail. May wrote that without the reassurance of intelligence analysis and the results of the war games, the possibility of Germany adopting the last version of ''Fall Gelb'' would have been remote. The French Dyle-Breda variant of the Allied deployment plan, was based on an accurate prediction of the German intentions, until the delays caused by the winter weather and shock of the Mechelen Incident led to the radical revision of ''Fall Gelb''. The French sought to assure the British that they would act to prevent the ''Luftwaffe'' using bases in the Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

and the Meuse valley and to encourage the Belgian and Dutch governments. The politico-strategic aspects of the plan ossified French thinking and the Phoney War

The Phoney War (french: Drôle de guerre; german: Sitzkrieg) was an eight-month period at the start of World War II, during which there was only one limited military land operation on the Western Front, when French troops invaded Germ ...

led to demands for Allied offensives in Scandinavia or the Balkans and the plan to start a war with the USSR. Changes to the Dyle-Breda variant might lead to forces being taken from the Western Front.

French and British intelligence sources were better than the German equivalents, which suffered from too many competing agencies but intelligence analysis was not as well integrated into Allied planning and decision-making. Information was delivered to operations officers but there was no mechanism like the German practice of allowing intelligence officers to comment on planning assumptions about opponents and allies. The insularity of the French and British intelligence agencies, meant that had they been asked if Germany would continue with a plan to attack across the Belgian plain after the Mechelen Incident, they would not have been able to point out how risky the Dyle-Breda variant was. May wrote that the wartime performance of the Allied intelligence services was abysmal. Daily and weekly evaluations had no analysis of fanciful predictions about German intentions and a May 1940 report from Switzerland, that the Germans would attack through the Ardennes, was marked as a German spoof. More items were obtained about invasions of Switzerland or the Balkans and German behaviour consistent with an Ardennes attack, such as the dumping of supplies and communications equipment on the Luxembourg

Luxembourg ( ; lb, Lëtzebuerg ; french: link=no, Luxembourg; german: link=no, Luxemburg), officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, ; french: link=no, Grand-Duché de Luxembourg ; german: link=no, Großherzogtum Luxemburg is a small lan ...

border and the concentration of ''Luftwaffe'' air reconnaissance around Sedan and Charleville-Mézières

or ''Carolomacérienne''

, image flag=Flag of Charleville Mezieres.svg

Charleville-Mézières () is a commune of northern France, capital of the Ardennes department, Grand Est.

Charleville-Mézières is located on the banks of the river Meuse. ...

was overlooked.

May wrote that French and British rulers were at fault for tolerating poor performance by the intelligence agencies and that the Germans could achieve surprise in May 1940, showed that even with Hitler, the process of executive judgement in Germany had worked better than in France and Britain. Allied politicians showed far less common sense in judging circumstances and deciding on policy but the Germans were no wiser. May referred to Marc Bloch in ''Strange Defeat'' (1940), that the German victory was a "triumph of intellect", which depended on Hitler's "methodical opportunism". Despite the mistakes of the Allies, May wrote that the Germans could not have succeeded but for outrageous good luck. German commanders wrote during the campaign and after, that often only a small difference had separated success from failure. Prioux thought that a counter-offensive could still have worked up to 19 May but by then, Belgian refugees were crowded on the roads needed for redeployment and the French transport units, that had performed well in the advance into Belgium, failed for lack of plans to move them back. Maurice Gamelin had said "It is all a question of hours." but the decision to sack Gamelin and appoint Weygand, caused a delay of two days.

May wrote that French and British rulers were at fault for tolerating poor performance by the intelligence agencies and that the Germans could achieve surprise in May 1940, showed that even with Hitler, the process of executive judgement in Germany had worked better than in France and Britain. Allied politicians showed far less common sense in judging circumstances and deciding on policy but the Germans were no wiser. May referred to Marc Bloch in ''Strange Defeat'' (1940), that the German victory was a "triumph of intellect", which depended on Hitler's "methodical opportunism". Despite the mistakes of the Allies, May wrote that the Germans could not have succeeded but for outrageous good luck. German commanders wrote during the campaign and after, that often only a small difference had separated success from failure. Prioux thought that a counter-offensive could still have worked up to 19 May but by then, Belgian refugees were crowded on the roads needed for redeployment and the French transport units, that had performed well in the advance into Belgium, failed for lack of plans to move them back. Maurice Gamelin had said "It is all a question of hours." but the decision to sack Gamelin and appoint Weygand, caused a delay of two days.

Frieser (2005)

In 2005, Frieser wrote that theGerman general staff

The German General Staff, originally the Prussian General Staff and officially the Great General Staff (german: Großer Generalstab), was a full-time body at the head of the Prussian Army and later, the German Army, responsible for the continuou ...

had tried to fight quick wars to avoid long two-front conflicts because of the vulnerable geographical position of the German state. The campaign of 1940 had not been planned as a blitzkrieg and study of the preparations for the campaign, especially of armaments show that the German commanders expected a long war similar to the First World War and was surprised by the success of the offensive. The war in the west occurred at a watershed in military history when military technology was favourable to the attack. The way that German armoured and air forces operated, led to a revival of the operational war of movement rather than position warfare, which made German command principles unexpectedly effective. By accident the German methods created a revolution in warfare, that France and its allies could not resist, still using the static thinking of the First World War. German officers were just as astonished but because of their training in mission tactics and operational thinking, could adapt much quicker.

Frieser argued that the unprecedented operational success of the Manstein Plan could only occur because the Allies fell into the trap, over and again, German success depended on forestalling Allied counter-moves, sometimes only by a few hours. Nazi and Allied propagandists later created a myth of an unstoppable German army, yet the Allies were superior in strength and in Case Red managed to adapt to German methods, although too late to avoid defeat. The German generals had been lukewarm about the Manstein Plan, Army Group A

Army Group A (Heeresgruppe A) was the name of several German Army Groups during World War II. During the Battle of France, the army group named Army Group A was composed of 45½ divisions, including 7 armored panzer divisions. It was responsible ...

wanting to limit the speed of the attack to that of marching infantry. The breakthrough on the Meuse at Sedan created such an opportunity that the panzer divisions raced ahead of the infantry divisions. OKH

The (; abbreviated OKH) was the high command of the Army of Nazi Germany. It was founded in 1935 as part of Adolf Hitler's rearmament of Germany. OKH was ''de facto'' the most important unit within the German war planning until the defeat at ...

and OKW occasionally lost control and in such unique circumstances, some German commanders ignored orders and regulations, claiming the discretion to follow mission tactics, the most notable being the unauthorised break-out from the Sedan bridgehead by Guderian. The events of 1940 had no relation to a blitzkrieg strategy ascribed to Hitler. Far from Hitler planning world domination by fighting a series of short wars, Hitler had not planned a war of any kind against the Allies.

Frieser argued that German rearmament

German rearmament (''Aufrüstung'', ) was a policy and practice of rearmament carried out in Germany during the interwar period (1918–1939), in violation of the Treaty of Versailles which required German disarmament after WWI to prevent Germa ...

was incomplete in 1939 and it had been France and Britain that had declared war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national government, i ...

on Germany; Hitler's gamble failed and left Germany with no way out, in a war against a more powerful coalition, with time on the Allies' side. Hitler chose flight forward and staked everything on a surprise attack, not supported by an officer corps mindful of the failure of the 1914 invasion. Allied generals did not anticipate the "daring leap" from the Meuse to the Channel and were as surprised as Hitler. Stopping the panzers short of Dunkirk was a mistake that forfeited the intended strategic success. The German campaign in the west was an "operational act of despair" to escape a dire strategic situation and ''blitzkrieg thinking'' occurred only ''after'' the Battle of France, it being the consequence, not the cause of victory. For the German army the triumph was hubristic, leading to exaggerated expectations about manoeuvre warfare and an assumption that victory over the USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

would be easy.

Tooze (2006)

industrial warfare

Industrial warfare is a period in the history of warfare ranging roughly from the early 19th century and the start of the Industrial Revolution to the beginning of the Atomic Age, which saw the rise of nation-states, capable of creating and equi ...

. German rearmament showed no evidence of a strategic synthesis claimed by the supporters of the blitzkrieg thesis. There had been an acceleration in war spending after 1933 but no obvious strategy or realistic prediction of the war Germany would come to fight. The huge armaments plans of 1936 and 1938 were for a big partially-mechanised army, a strategic air force and an ocean-going fleet. In early 1939, a balance of payments crisis led to chaos in the armaments programme; the beginning of the war led to armaments output increasing again but still with no sign of a blitzkrieg concept determining the programme. The same discrepancy between German military-industrial preparations and the campaign can be seen in the plans formed for the war in the west. There was no plan before September 1939 and the first version in October was a compromise that satisfied no-one but the capture the Channel coast to conduct an air war against Britain, was apparently the purpose determining armaments production from December 1939.

Tooze wrote that the plan failed to offer the possibility of a decisive victory in the west desired by Hitler but lasted until the Mechelen Incident of February 1940. The incident was the catalyst for an alternative plan for an encircling move through the Ardennes proposed by Manstein but it came too late to change the armaments programme. The swift victory in France was not the consequence of a thoughtful strategic synthesis but a lucky gamble, an improvisation to resolve the strategic problems that the generals and Hitler had failed to resolve by February 1940. The Allies and the Germans were equally reluctant to reveal the casual way that the Germans gained their biggest victory. The blitzkrieg myth suited the Allies, because it did not refer to their military incompetence; it was expedient to exaggerate the excellence of German equipment. The Germans avoided an analysis based on technical determinism, since this contradicted Nazi ideology and ''OKW'' attributed the victory to the "revolutionary dynamic of the Third Reich and its National Socialist leadership".

Tooze wrote that by contradicting the technology version of the blitzkrieg myth, recent writing had tended to vindicate the regime view, that success was due to the Manstein Plan and the fighting power of German troops. Tooze wrote that although there had been no strategic synthesis, the human element could be overstated. The success of the German offensive was dependent on the mobilisation of the German economy in 1939 and the geography of western Europe. The number of German tanks in May 1940 showed that output of armoured vehicles had not been the priority of the German armaments effort since 1933 but without the tank production drive of autumn 1939, the position would have been far worse. After the invasion of Poland there were only 2,701 serviceable vehicles, most being Panzer I

The Panzer I was a light tank produced in Nazi Germany in the 1930s. Its name is short for (German for "armored fighting vehicle mark I"), abbreviated as . The tank's official German ordnance inventory designation was ''Sd.Kfz. 101'' ...

and Panzer II

The Panzer II is the common name used for a family of German tanks used in World War II. The official German designation was ''Panzerkampfwagen'' II (abbreviated PzKpfw II).

Although the vehicle had originally been designed as a stopgap while la ...

, only the 541 Panzer III

The ''Panzerkampfwagen III'', commonly known as the Panzer III, was a medium tank developed in the 1930s by Germany, and was used extensively in World War II. The official German ordnance designation was Sd.Kfz. 141. It was intended to fight oth ...

and IV tanks being suitable for a western campaign. Had these tanks been used according to the October 1939 plan, the Germans would have been lucky to achieve a draw. By 10 May 1940, the Germans had 1,456 tanks, 785 Panzer III, 290 Panzer IV and 381 Panzer 35(t)

The Panzerkampfwagen 35(t), commonly shortened to Panzer 35(t) or abbreviated as Pz.Kpfw. 35(t), was a Czechoslovak-designed light tank used mainly by Nazi Germany during World War II. The letter (t) stood for ''tschechisch'' (German for "Czech" ...

and Panzer 38(t)

The 38(t), originally known as the ČKD LT vz. 38, was a tank designed during the 1930s, which saw extensive service during World War II. Developed in Czechoslovakia by ČKD, the type was adopted by Nazi Germany following the annexation of Cze ...

tanks. None of the German panzers were a match for the best French tanks and no anti-tank gun was effective against the Char B but German tanks had good fighting compartments and excellent wireless equipment, making the tanks that the Germans did have an effective armoured force.

Tooze wrote that the Manstein Plan

(Case Yellow), the invasion of France and the Low Countries

, scope = Strategic

, type =

, location = South-west Netherlands, central Belgium, northern France

, coordinates =

, planned = 1940

, planned_by = Erich von ...

contained no new and revolutionary theory of armoured warfare

Armoured warfare or armored warfare (mechanized forces, armoured forces or armored forces) (American English; American and British English spelling differences#-our, -or, see spelling differences), is the use of armoured fighting vehicle, armo ...

and was not based on faith in the superiority of German soldiers but the Napoleonic formula of achieving superiority at one point, known in German terms as ''Schwerpunktbildung''; the plan combined materialism and military art. With 135 German divisions facing 151 Allied divisions, concentration and surprise which were the principles of operational doctrine, were indispensable and the German success in achieving these explains the victory, not better equipment or morale. The Germans committed 29 divisions to the diversion in Belgium and the Netherlands which were countered by 57 Allied divisions, including the best French and British formations. Along the Rhine valley, the Germans had 19 mediocre divisions and the French garrisoned the Maginot Line with 36 divisions, odds of about 2:1 against the Germans. The Germans were able to mass 45 elite divisions in the Ardennes against 18 second-rate Belgian and French divisions, a ratio of 3:1 in favour of the Germans, multiplied in effect by deception and speed of manoeuvre. No panzer division was held in reserve and had the attempt failed there would have been no armoured units to oppose an Allied counter-offensive. Daily losses were high but the short campaign meant that the total number of casualties was low.

By keeping much of their air forces in reserve, the Allies conceded air superiority to the ''Luftwaffe'' but operations on 10 May cost 347 aircraft and by the end of the month the ''Luftwaffe'' had lost 30 percent of its aircraft, with another 13 percent badly damaged. Intensive and costly air operations were made in support of Panzer Group Kleist

The XXII Motorised Corps (''XXII. Armeekorps (motorisiert)'') was a German army corps during World War II.''

History

The XXII. Armeekorps (motorisiert) was created on 26 August 1939 in Wehrkreis X (Schleswig-Holstein, Hamburg, Bremen).

The Cor ...

, which had 1,222 tanks, 545 half-track

A half-track is a civilian or military vehicle with regular wheels at the front for steering and continuous tracks at the back to propel the vehicle and carry most of the load. The purpose of this combination is to produce a vehicle with the cro ...

s and 39,373 lorries and cars, enough to cover of road. On the approach to the Meuse crossings, the panzer group moved in four -long columns over only four roads and had to reach the crossings by the evening of 13 May or the Allies might have time to react. Huge risks were taken to get the columns forward, including running petrol lorries in the armoured columns to refuel vehicles at every stop. Had Allied bombers been able to pierce the fighter screen, the German advance could have been turned into a disaster. To keep going for three days and nights, drivers were given Pervitin

Methamphetamine (contracted from ) is a potent central nervous system (CNS) stimulant that is mainly used as a recreational drug and less commonly as a second-line treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and obesity. Methamph ...

stimulants. Tooze wrote that these expedients were limited to about 12 divisions and that the rest of the German army invaded France on foot, supplied by horse and cart from railheads as in 1914. The Channel coast provided a natural obstacle about away, a distance over which motorised supply could function efficiently over the dense French road network, commandeering supplies from French farms as they went.

Tooze wrote that the German victories of 1940 appeared to be of less significance than the changes they caused in the US, where hostility to German ambitions had been manifest since 1938. On 16 May, the day after the German breakthrough on the Meuse, Roosevelt laid before Congress a plan to create the greatest military-industrial complex in history, capable of building 50,000 aircraft a year. Congress passed the Two-Ocean Navy Act

The Two-Ocean Navy Act, also known as the Vinson-Walsh Act, was a United States law enacted on July 19, 1940, and named for Carl Vinson and David I. Walsh, who chaired the Naval Affairs Committee in the House and Senate respectively. The largest n ...

and in September the US, for the first time, began conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

in peacetime to raise an army of 1.4 million men. By 1941, the US was producing a similar quantity of armaments to Britain or Germany and financing the first permanent increase in civilian consumption since the 1920s. The British post-Dunkirk strategy was a gamble on access to the resources of the US and the empire and that the US would supply weapons and materials even when British had exhausted their ability to pay. Unless Britain was defeated, Germany was confronted by a fundamental strategic problem, that the US had the means to use its industrial power against the Third Reich.

Doughty (2014)

Robert A. Doughty

Robert Allan Doughty (born November 4, 1943) is an American military historian and retired United States Army officer.

Early life

Doughty was born in Tullos, Louisiana, on November 4, 1943, to parents John and Georgia Doughty.

Career

He a ...

, a history department chair at West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), also known Metonymy, metonymically as West Point or simply as Army, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York. It was originally established as a f ...

, has explored numerous facets of 20th century French military history. He wrote that the German offensive was complicated and at times chaotic, rather than a simple armoured rush through the Ardennes and across France. French strategy had left the Allies vulnerable to a breakthrough along the Ardennes and the army failed adequately to react to the breakthrough and the massing of tanks; tactically the German tanks and infantry had defeated French defences that were rarely formidable. French military intelligence also failed to identify the main German attack and even on the morning of 13 May, thought that the ''Schwerpunkt'' (main effort) was in central Belgium. The French had made the grave error of concentrating on evidence that supported their assumptions rather than assess German capacity and give credence to reports that the Germans were not conforming to French expectations. The French had based their strategy on a theory of methodical battle and firepower against a German theory of manoeuvre, surprise and speed. French centralised authority was not suited to the practice of hasty counter-attacks or bold manoeuvres, sometimes appearing to move in "slow motion".

Doughty wrote that methodical battle might have succeeded against a similar opponent but was inadequate against the fast and aggressive Germans, who seized the initiative and were strategically, operationally and tactically superior at the decisive point, defeating the French who were unable to react quickly enough as deep German advances disorganised French counter-moves. Experience in Poland was used to improve the German army and make officers and units more flexible and a willingness to be pragmatic allowed reforms to be made which, while incomplete, showed their value in France. The French had been overconfident and after the fall of Poland had speeded the assembly of large armoured units but failed to re-think the theory that guided their use. After the defences at Sedan had been criticised, Huntziger had written, "I believe that no urgent measures are necessary to reinforce the Sedan sector."; the Second Army had made no effort to improve them.

In the German tradition of delegation, sometimes known as '' Auftagstaktik'' (mission command), leaders were trained to take the initiative, within the commander's intent, to accomplish the mission. The German system worked better than the French emphasis on obedience, following ''doctrine'' and eschewing novelty. ''Auftragstaktik'' was not a panacea as the argument between Kleist and Guderian demonstrated but Guderian's refusals orders would have been intolerable to a French officer. On 14 May, Lieutenant-General Jean-Marie-Léon Etcheberrigaray refused to order the 53rd Division to counter-attack, due to a lack of time; Major-General Georges-Louis-Marie Brocard commander of the 3e ''Division Cuirassée'' (3e DCr), could not attack for lack of supplies and was sacked for the failure to supply and move the division. Command from the front was possible for German commanders, because their chiefs of staff were accustomed to wield executive authority, managing the flow of units and supplies, tasks which in the French army were reserved for the commanding officer. Guderian had been free to move around during the fighting at Sedan, while Grandsard and Huntziger remained at their headquarters, unable to hurry on units and overrule hesitant commanders.

See also

*Historiography of World War II The historiography of World War II is the study of how historians portray the causes, conduct, and outcomes of World War II.

There are different perspectives on the causes of the war; the three most prominent are the Orthodox from the 1950s, Revisi ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

Books * * * * * * * * * Journals *Further reading

Books * * * * * * Connors, Joseph David. (1977) "Paul Reynaud and French national defense, 1933-1939." (PhD Loyola University of Chicago, 1977)online

Bibliography, pp 265–83. * * * de Konkoly Thege, Michel Marie. (2015) "Paul Reynaud and the Reform of France's Economic, Military and Diplomatic Policies of the 1930s." (Graduate Liberal Studies Works (MALS/MPhil). Paper 6, 2015)

online

bibliography pp 171–76. * Doughty, Robert Allan. (1985) ''The Seeds of Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919–1939'' (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1985) * * * Fishman, Sarah; Lake, David. (2000) ''France at War: Vichy & the Historians'' (2000). * Gunsberg, Jefferey. (1979) ''Divided and Conquered: The French High Command and the Defeat of the West, 1940'' (Westport CT: Greenwood Press, 1979). * * * Higham, Robin. (2012) ''Two Roads to War: The French and British Air Arms from Versailles to Dunkirk'' (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2012

online

* * Imlay, Talbot C. "Strategies, Commands, and Tactics, 1939–1941." in Thomas W. Zeiler and Daniel M. DuBois, eds. ''A Companion to World War II'' (2013) 2: 415–32. * * * * *

online

* * Nord, Philip. (2015) ''France 1940: Defending the Republic'' (Yale UP, 2015). * * * Shennan, Andrew. (2000) ''The Fall of France, 1940'' (2000)

excerpt

{{Short pages monitor