Historical Examples Of Flanking Maneuvers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In military tactics, a flanking maneuver, or flanking manoeuvre (also called a flank attack), is an attack on the sides of an opposing force. If a flanking maneuver succeeds, the opposing force would be surrounded from two or more directions, which significantly reduces the maneuverability of the outflanked force and its ability to defend itself.

Flanking maneuvers play a critical role in nearly every major battle in history; and have been used effectively by famous military leaders like

During the

During the

The December 1805

The December 1805

The ground campaign of

The ground campaign of

Hannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

, Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

, Khalid ibn al-Walid

Khalid ibn al-Walid ibn al-Mughira al-Makhzumi (; died 642) was a 7th-century Arab military commander. He initially headed campaigns against Muhammad on behalf of the Quraysh. He later became a Muslim and spent the remainder of his career in ...

, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

, Saladin

Yusuf ibn Ayyub ibn Shadi () ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known by the epithet Saladin,, ; ku, سهلاحهدین, ; was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from an ethnic Kurdish family, he was the first of both Egypt and ...

, Nader Shah

Nader Shah Afshar ( fa, نادر شاه افشار; also known as ''Nader Qoli Beyg'' or ''Tahmāsp Qoli Khan'' ) (August 1688 – 19 June 1747) was the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran and one of the most powerful rulers in Iranian h ...

, William Tecumseh Sherman and Stonewall Jackson

Thomas Jonathan "Stonewall" Jackson (January 21, 1824 – May 10, 1863) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, considered one of the best-known Confederate commanders, after Robert E. Lee. He played a prominent role in nearl ...

throughout. Sun Tzu's ''The Art of War

''The Art of War'' () is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ("Master Sun"), is com ...

'' strongly emphasizes the use of flanking, although it does not advocate completely surrounding the enemy force as this may induce it to fight with greater ferocity if it cannot escape.

A flanking maneuver is not always effective, as the flanking force may itself be ambushed while maneuvering, or the main force is unable to pin the defenders in place, allowing them to turn and face the flanking attack.

Ancient warfare

Battle of Salamis

During the

During the second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasion ...

, after great losses at the Battle of Thermopylae

The Battle of Thermopylae ( ; grc, Μάχη τῶν Θερμοπυλῶν, label=Greek, ) was fought in 480 BC between the Achaemenid Persian Empire under Xerxes I and an alliance of Greek city-states led by Sparta under Leonidas I. Lasting o ...

and the Battle of Artemisium, the Greeks once again brought the Persians to blows in the Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles and the Persian Empire under King Xerxes in 480 BC. It resulted in a decisive victory for the outnumbered Greeks. The battle was ...

in the year 480 BC. The Greek fleet numbered 378 triremes while the Persian may have numbered more than four times that. However, in the narrow confines of the straits, the numerical superiority of the Persians became an active hindrance. The Persians became disorganized in the cramped straits, and the Greeks were in a position to flank from the northwest. Retreating Persian ships were befouled by the approaching second and third lines who were advancing to the line of battle.

In the aftermath of the battle, Xerxes retreated to Asia with the majority of his army. In his wake he left Mardonius, who would be decisively defeated by the Greek army the following year in the Battle of Plataea

The Battle of Plataea was the final land battle during the second Persian invasion of Greece. It took place in 479 BC near the city of Plataea in Boeotia, and was fought between an alliance of the Greek city-states (including Sparta, Athens, C ...

.

Battle of Leuctra

In 371 BC, the armies ofSparta

Sparta ( Doric Greek: Σπάρτα, ''Spártā''; Attic Greek: Σπάρτη, ''Spártē'') was a prominent city-state in Laconia, in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (, ), while the name Sparta referre ...

and Thebes gave battle near the city of Leuctra, despite the superior numbers and fearful reputation of the Spartan army, the unbalanced Theban attack, with the Sacred Band of Thebes on the extreme left and in echelon formation

An echelon formation () is a (usually military) formation in which its units are arranged diagonally. Each unit is stationed behind and to the right (a "right echelon"), or behind and to the left ("left echelon"), of the unit ahead. The name of ...

disorganized the Spartan lines and spread confusion in its army. Before even the extreme Spartan right wing had entered the fray, the battle was lost for them. It was Epaminondas greatest triumph and shattered the myth of Spartan invincibility.

The Battle of Leuctra has become the archetypal example of a flanking attack since. It inspired the adoption of the echelon formation

An echelon formation () is a (usually military) formation in which its units are arranged diagonally. Each unit is stationed behind and to the right (a "right echelon"), or behind and to the left ("left echelon"), of the unit ahead. The name of ...

by the Macedonian armies of Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

and Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, wikt:Ἀλέξανδρος, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Maced ...

.

Battle of Cannae

In 216 BCHannibal

Hannibal (; xpu, 𐤇𐤍𐤁𐤏𐤋, ''Ḥannibaʿl''; 247 – between 183 and 181 BC) was a Carthaginian general and statesman who commanded the forces of Carthage in their battle against the Roman Republic during the Second Puni ...

accomplished one of the most famous flanking maneuvers of all history at the Battle of Cannae

The Battle of Cannae () was a key engagement of the Second Punic War between the Roman Republic and Carthage, fought on 2 August 216 BC near the ancient village of Cannae in Apulia, southeast Italy. The Carthaginians and their allies, led by ...

. Using a double flanking maneuver known as a pincer movement, Hannibal managed to surround and kill nearly the entirety of a larger Consular Roman Army. The defeat sent the Roman Republic into complete disarray and remains a singular example of outstanding tactical leadership. As military historian Theodore Ayrault Dodge wrote:

Battle of Pharsalus

In 48 BC at theBattle of Pharsalus

The Battle of Pharsalus was the decisive battle of Caesar's Civil War fought on 9 August 48 BC near Pharsalus in central Greece. Julius Caesar and his allies formed up opposite the army of the Roman Republic under the command of Pompey. P ...

, Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

faced the army of Pompey

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (; 29 September 106 BC – 28 September 48 BC), known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a leading Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of ...

, which not only outnumbered his more than four to one, but was also in more or less friendly territory. Conversely, Caesar's own army, due to his blocked crossing of the Adriatic Sea, had been cut in half as well as cut off from their supply lines. The rest of the army lay on the opposing shores of the Adriatic, unable to aid their comrades.

Anticipating a turning of his flank, Caesar had hidden a line of reserves in this area. When Pompey turned Caesar's cavalry, rather than finding a route through which to attack his enemy in the rear, he encountered 2,000 legionnaires. These were armed with pila

Pila may refer to:

Architecture

* Pila (architecture), a type of veranda in Sri Lankan farm houses

Places

*Pila, Buenos Aires, a town in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

*Pila Partido, a country subdivision in Buenos Aires Province, Argentina

* ...

, normally a missile weapon such as a javelin

A javelin is a light spear designed primarily to be thrown, historically as a ranged weapon, but today predominantly for sport. The javelin is almost always thrown by hand, unlike the sling, bow, and crossbow, which launch projectiles with th ...

, but the legionnaires used their length as a stabbing anti-cavalry weapon instead. Having turned back the flank of his enemy, Caesar now found his own open flank, which he used to rout the army of Pompey.

After his defeat, Pompey fled to Egypt, and the battle marked the effective end of the Wars of the First Triumvirate.

Early modern warfare

Battle of Garigliano

On 29 December 1503, the Spanish army ofGonzalo Fernández de Córdoba

Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba (1 September 1453 – 2 December 1515) was a Spanish general and statesman who led successful military campaigns during the Conquest of Granada and the Italian Wars. His military victories and widespread po ...

crossed the River Garigliano using an upriver pontoon bridge to defeat the French army. The outnumbered Spaniard and Italian troops left the main army in front of the same positions they had keep against the French army of the Marquis of Saluzzo

The marquises (also marquesses or margraves) of Saluzzo were the medieval feudal rulers city of Saluzzo (today part of Piedmont, Italy) and its countryside from 1175 to 1549. Originally counts, the family received in ''feudum'' the city from the ...

. The bold maneuver of the Gran Capitán spread terror in the demoralized French army that began to retreat. The Spanish main body, led by Andrade and Mendoza, crossed the river in front of the retreating army and transformed the retreat into a rout.

Despite Chevalier Bayard

Pierre Terrail, seigneur de Bayard (c. 1476 – 30 April 1524) was a French knight and military leader at the transition between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, generally known as the Chevalier de Bayard. Throughout the centuries since his ...

brave rearguard actions at Mola bridge, the French army was forced to seek refuge in Gaeta where they surrendered a few days later.

This victory and the previous one at the battle of Cerignola formed the basis for the fearful reputation of the Spanish infantry, the Tercios Viejos that lasted for more than a century until the battle of Rocroi.

Nader Shah

Nader Shah Afshar ( fa, نادر شاه افشار; also known as ''Nader Qoli Beyg'' or ''Tahmāsp Qoli Khan'' ) (August 1688 – 19 June 1747) was the founder of the Afsharid dynasty of Iran and one of the most powerful rulers in Iranian h ...

Early Battles

Battle of Kirkuk The Battle of Kirkuk may refer to several historical battles over several conflicts:

* Battle of Kirkuk (1733) during the Ottoman–Persian War (1730–35)

* Battle of Kirkuk (1991), part of the 1991 uprisings in Iraq

* Battle of Kirkuk (2014), par ...

Battle of Kars

The Battle of Kars was a decisive Russian victory over the Ottoman Empire during the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878). The battle for the city took place on November 17th, 1877, and resulted in the Russians capturing the city along with a large por ...

Frederick the Great

Frederick II (german: Friedrich II.; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was King in Prussia from 1740 until 1772, and King of Prussia from 1772 until his death in 1786. His most significant accomplishments include his military successes in the Sil ...

Napoleon Bonaparte

Ulm Campaign

The Ulm Campaign of September to October 1805 saw Napoleon Bonaparte engage in a monthlong maneuver aimed at severing Austrian lines and eventually capturing an entire Austrian army. The casualties were exceptionally one-sided for a modern battle, with the French suffering 2,000 casualties and the Austrians suffering 60,000, mostly captured. As Trevor Dupuy put it:Ulm was not a battle; it was a strategic victory so complete and so overwhelming that the issue was never seriously contested in tactical combat. Also, This campaign opened the most brilliant year of Napoleon's career. His army had been trained to perfection; his plans were faultless.The aftermath of the campaign would quickly see the fall of Vienna, and the final exit of Austria as a member of the Allied forces. It is widely regarded as the inspiration for the Schlieffen Plan, as the world would see it unfold some 100 years later. The campaign would also prove the effectiveness of ''la manoeuvre sur les derrières'', wherein a pinning force was utilized to occupy the enemy while a flanking force descended at the critical moment to decide the battle.

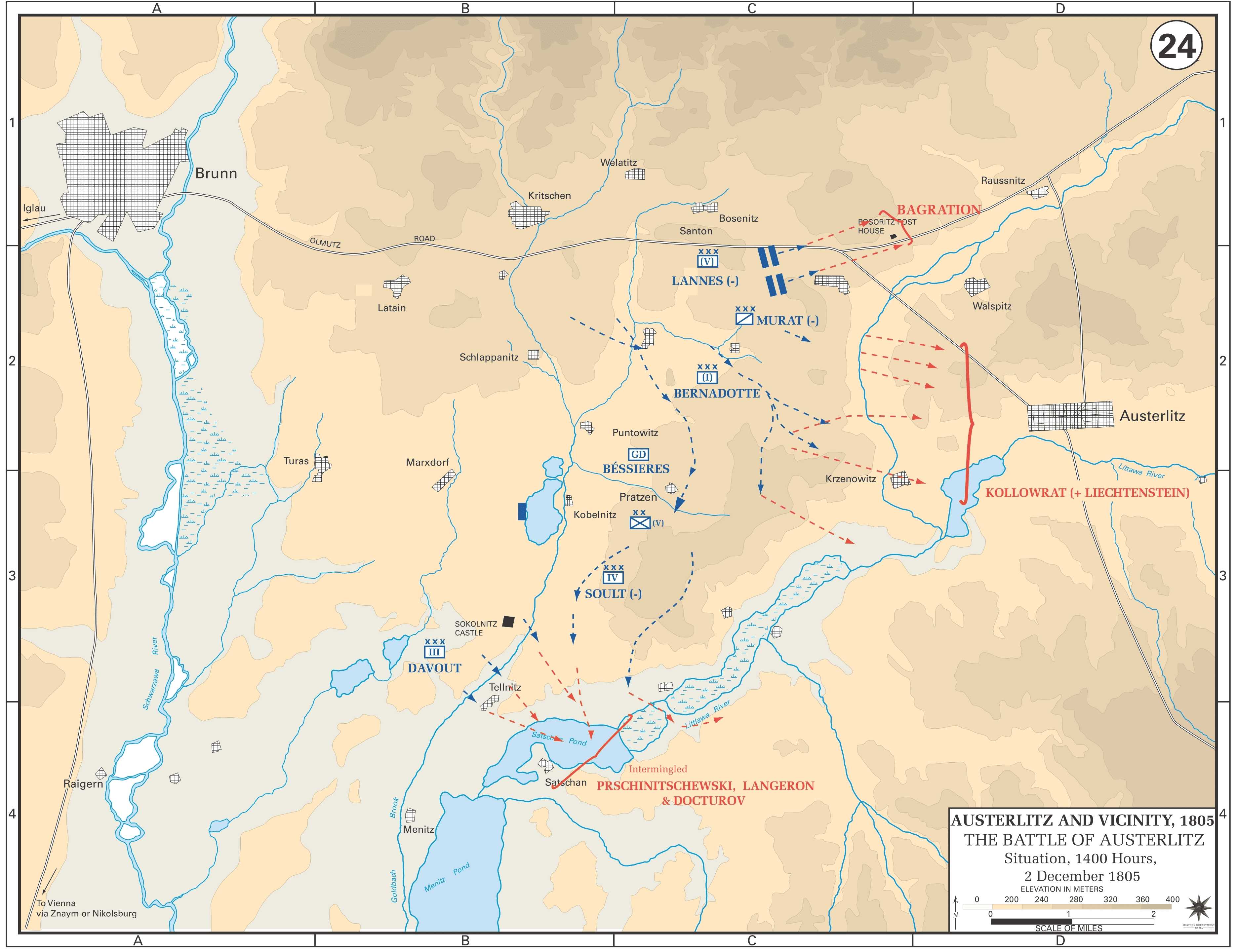

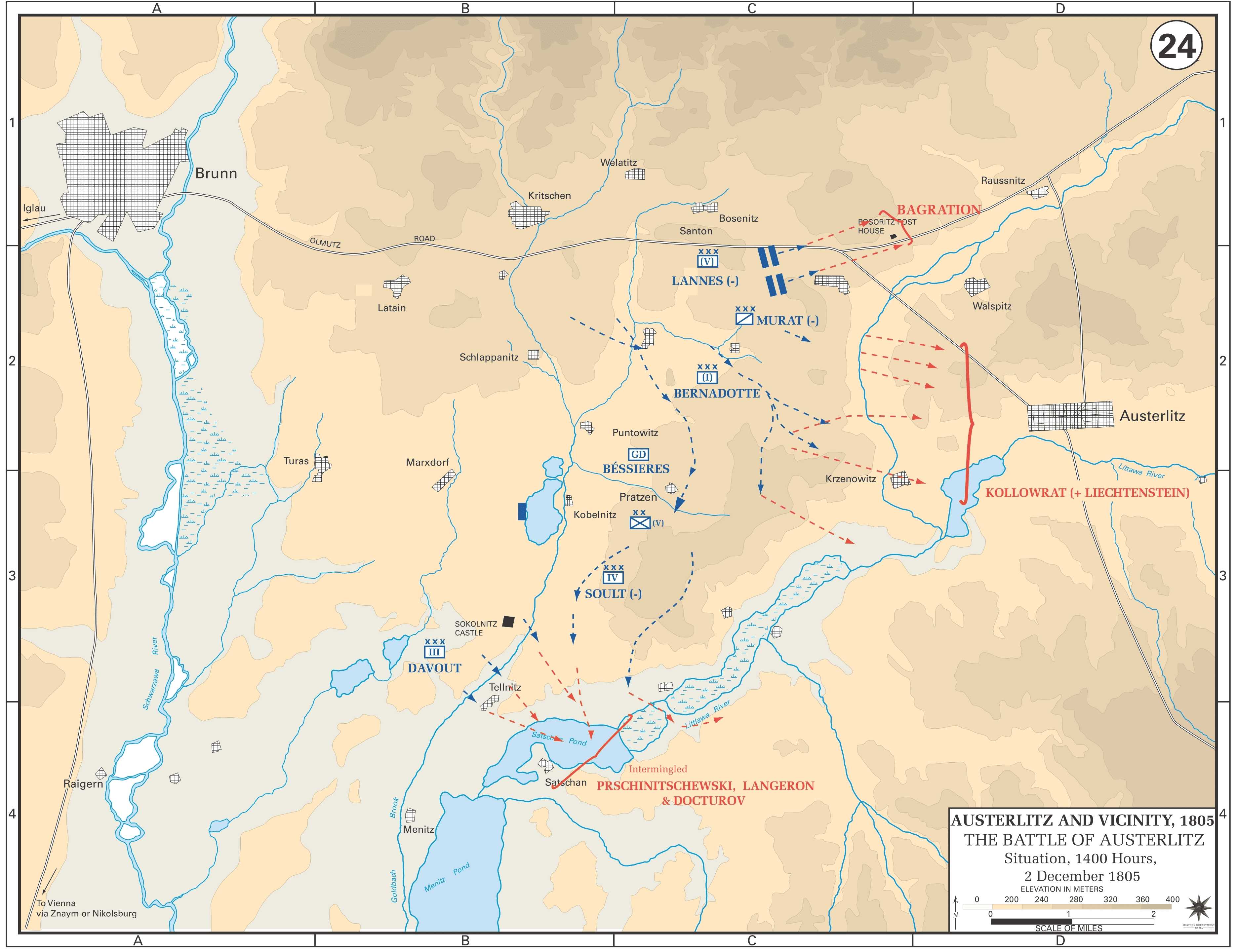

Battle of Austerlitz

The December 1805

The December 1805 Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important and decisive engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near the town of Austerlitz in ...

is widely seen as a tactical masterpiece of the same stature as Cannae, the celebrated triumph by Hannibal some 2,000 years before. Prior to the engagement, Napoleon went to great lengths to indicate to the Russians and Austrians that his forces were weak and he was on the verge of seeking a peace. He successfully hid the presence of some 75,000 troops from his enemies while still keeping them within reinforcement range, and even went so far as to retire, and give his enemies the confidence of occupying the high ground, as well as intentionally weakening his right flank.

The engagement resulted in the final exit of Austria from the war, and the expulsion of the Russian Army from the continental war. The French Army had lost about 13% of its numbers, while the Allies lost a full 36,000 men, 42% of their total force.

Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War was marked by two devastating encirclements by the Prussian Army of the French. Although a spirited resistance movement continued in France for some time, these effectively ended large scale fighting for the rest of the war.Siege of Metz

Following a loss at theBattle of Gravelotte

The Battle of Gravelotte (or Battle of Gravelotte–St. Privat) on 18 August 1870 was the largest battle of the Franco-Prussian War. Named after Gravelotte, a village in Lorraine, it was fought about west of Metz, where on the previous day, ha ...

, the French Army of the Rhine retreated to the defenses of Metz. Given their fortified entrenchment, the Prussians readily encircled the position and laid siege. The army would be forced to surrender two months later, but not before a doomed attempt by Napoleon III to rescue the Army of the Rhine.

Battle of Sedan

In September 1870, Napoleon III had formed the Army of Châlons to attempt to relieve the 150,000 French troops invested at Metz. After losing a hard battle at Beaumont-en-Argonne, the Army of Châlons retreated toward Sedan. Exhausted and short on supplies, the French planned to rest in the town before reengaging the Prussian forces. Unfortunately for the French, the well rested and supplied Prussians split their forces into three groups, which they quickly used to flank and encircle the French, forcing them to fight the quite adverseBattle of Sedan

The Battle of Sedan was fought during the Franco-Prussian War from 1 to 2 September 1870. Resulting in the capture of Emperor Napoleon III and over a hundred thousand troops, it effectively decided the war in favour of Prussia and its allies, ...

. After staggering casualties, the force along with the king surrendered the following morning. Along with the surrender of the King, came the implicit surrender of the French government. Along with the surrender of the Army of Châlons, came the inevitable surrender of the force at Metz, which they were intended to relieve.

The First World War

Western Front

The First World War began with one of the largest flanking maneuvers in military history, both in terms of the strength of the forces in the field as well as the vast geographic area through which they were deployed. Originally, the Schlieffen Plan for invasion of France by Germany called for a force of 1.36 million troops in a "scythe-sweep" through Belgium and into France toward Paris The eventual force deployed by Helmuth von Moltke the Younger in 1914 totaled instead, 970,000 troops. While the German Army did manage to successfully occupy virtually all of Belgium, the offensive became mired in a number of costly and indecisive battles, such as those in Yser and Ypres, and eventually was halted in large part with theFirst Battle of the Marne

The First Battle of the Marne was a battle of the First World War fought from 5 to 12 September 1914. It was fought in a collection of skirmishes around the Marne River Valley. It resulted in an Entente victory against the German armies in the ...

. In November 1914 Erich von Falkenhayn

General Erich Georg Sebastian Anton von Falkenhayn (11 September 1861 – 8 April 1922) was the second Chief of the German General Staff of the First World War from September 1914 until 29 August 1916. He was removed on 29 August 1916 after t ...

, who had replaced Moltke in September, informed the Kaiser that no great successes could be expected on the Western Front, and that strength, morale, and supplies were exhausted.

The eventual outcome of this strategy was the Race to the Sea, where a series of flanking attempts by both sides resulted in an unbroken line stretching from Switzerland in the south to the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

in the north. From this point forward on the Western Front, flanking became impossible and the war eventually devolved into a protracted war of attrition.

Sinai and Palestine Front

On several occasions during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign the German and Ottoman forces were successfully outflanked by the mobileEgyptian Expeditionary Force

The Egyptian Expeditionary Force (EEF) was a British Empire military formation, formed on 10 March 1916 under the command of General Archibald Murray from the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force and the Force in Egypt (1914–15), at the beginning of ...

. At the Battle of Mughar Ridge and Battle of Megiddo they were outflanked, while at the Battle of Magdhaba

The Battle of Magdhaba took place on 23 December 1916 during the Defence of Egypt section of the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in the First World War.The Battles Nomenclature Committee assigned 'Affair' to those engagements between forces small ...

and Battle of Beersheba they were surrounded.

The Second World War

While the First World War saw the introduction of large scale mechanization in modern warfare, the lack of tactical experience of the commanders and the technical limitations of the weapon systems greatly limited their usefulness. For example, the Mark V tank employed by the allies boasted a maximum speed of five miles per hour and an operational limit of 10 hours under ideal circumstances. In the reality of the battlefield, this could be greatly reduced, and many tanks were greatly slowed or dead-lined by adverse terrain. However, by the start of the Second World War armies had been thoroughly mechanized and the available weapon systems had greatly increased their capabilities. In comparison to the Mark V, theM4 Sherman

}

The M4 Sherman, officially Medium Tank, M4, was the most widely used medium tank by the Military history of the United States during World War II, United States and Allies of World War II, Western Allies in World War II. The M4 Sherman prove ...

utilized by the Allies featured a maximum speed of 30 miles per hour and an operational range of up to 120 miles. These increased capabilities revolutionized the battlefield. Whereas cavalry, the traditional flanking force, had been rendered moot in the previous war by artillery and automatic weapons fire, armor emerged in this new conflict as the mobile flanking force of the modern era.

Invasion of Poland

In theInvasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week aft ...

Germany utilized the speed of its mechanized strength to break through the flanks of, or between the flanks of Polish forces and into the interior of the country. The result of this was, rather than maintaining a front line opposing the enemy, the Poles found themselves in multiple isolated pockets with the mass of the German army occupying the original front, and the German mobile divisions behind their own positions.

They were therefore unable to retreat, resupply, or be reinforced. Furthermore, as makes intuitive sense, a less mobile force finding itself in a pocket or salient, even if a breakout is achieved, cannot but find themselves encircled again.

Desert Storm

The ground campaign of

The ground campaign of Desert Storm

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

during the 1991 Gulf War

The Gulf War was a 1990–1991 armed campaign waged by a 35-country military coalition in response to the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Spearheaded by the United States, the coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: ...

was characterised by the flanking attack of the Coalition forces, the massive "left hook" which avoided the Iraqi forces dug in along the Kuwait–Saudi border; but instead swept past them in the west. Once the allies had penetrated deep into Iraqi territory, they turned eastward, launching a flank attack against the elite Republican Guard before it could escape. The Iraqis resisted fiercely from dug-in positions and stationary vehicles, and even mounted armored charges.

Unlike many previous engagements, the destruction of the first Iraqi tanks did not result in a mass surrender. The Iraqis suffered massive losses and lost dozens of tanks and vehicles, while U.S. casualties were comparatively low, with a single Bradley knocked out.Twentieth Century Battlefields: The Gulf War

References

{{Reflist Military tactics