Histologically on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of

For plants, the study of their tissues falls under the field of

For plants, the study of their tissues falls under the field of

Chemical fixatives are used to preserve and maintain the structure of tissues and cells; fixation also hardens tissues which aids in cutting the thin sections of tissue needed for observation under the microscope. Fixatives generally preserve tissues (and cells) by irreversibly cross-linking proteins. The most widely used fixative for light microscopy is 10% neutral buffered

Chemical fixatives are used to preserve and maintain the structure of tissues and cells; fixation also hardens tissues which aids in cutting the thin sections of tissue needed for observation under the microscope. Fixatives generally preserve tissues (and cells) by irreversibly cross-linking proteins. The most widely used fixative for light microscopy is 10% neutral buffered

For light microscopy,

For light microscopy,

For light microscopy, a knife mounted in a microtome is used to cut tissue sections (typically between 5-15

For light microscopy, a knife mounted in a microtome is used to cut tissue sections (typically between 5-15

In the 17th century the Italian

In the 17th century the Italian

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

which studies the microscopic anatomy

Anatomy () is the branch of biology concerned with the study of the structure of organisms and their parts. Anatomy is a branch of natural science that deals with the structural organization of living things. It is an old science, having its ...

of biological tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy

Gross anatomy is the study of anatomy at the visible or macroscopic level. The counterpart to gross anatomy is the field of histology, which studies microscopic anatomy. Gross anatomy of the human body or other animals seeks to understand the rel ...

, which looks at larger structures visible without a microscope

A microscope () is a laboratory instrument used to examine objects that are too small to be seen by the naked eye. Microscopy is the science of investigating small objects and structures using a microscope. Microscopic means being invisibl ...

. Although one may divide microscopic anatomy into ''organology'', the study of organs, ''histology'', the study of tissues, and ''cytology

Cell biology (also cellular biology or cytology) is a branch of biology that studies the structure, function, and behavior of cells. All living organisms are made of cells. A cell is the basic unit of life that is responsible for the living and ...

'', the study of cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

, modern usage places all of these topics under the field of histology. In medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

, histopathology

Histopathology (compound of three Greek words: ''histos'' "tissue", πάθος ''pathos'' "suffering", and -λογία '' -logia'' "study of") refers to the microscopic examination of tissue in order to study the manifestations of disease. Spe ...

is the branch of histology that includes the microscopic identification and study of diseased tissue. In the field of paleontology

Paleontology (), also spelled palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of life that existed prior to, and sometimes including, the start of the Holocene epoch (roughly 11,700 years before present). It includes the study of fossi ...

, the term paleohistology refers to the histology of fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

organisms.

Biological tissues

Animal tissue classification

There are four basic types of animal tissues:muscle tissue

Muscle tissue (or muscular tissue) is soft tissue that makes up the different types of muscles in most animals, and give the ability of muscles to contract. Muscle tissue is formed during embryonic development, in a process known as myogenesis. Mu ...

, nervous tissue

Nervous tissue, also called neural tissue, is the main tissue component of the nervous system. The nervous system regulates and controls body functions and activity. It consists of two parts: the central nervous system (CNS) comprising the brain ...

, connective tissue

Connective tissue is one of the four primary types of animal tissue, along with epithelial tissue, muscle tissue, and nervous tissue. It develops from the mesenchyme derived from the mesoderm the middle embryonic germ layer. Connective tiss ...

, and epithelial tissue

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is one of the four basic types of animal tissue, along with connective tissue, muscle tissue and nervous tissue. It is a thin, continuous, protective layer of compactly packed cells with a little intercellu ...

. All animal tissues are considered to be subtypes of these four principal tissue types (for example, blood is classified as connective tissue, since the blood cells are suspended in an extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix, is a three-dimensional network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide stru ...

, the plasma

Plasma or plasm may refer to:

Science

* Plasma (physics), one of the four fundamental states of matter

* Plasma (mineral), a green translucent silica mineral

* Quark–gluon plasma, a state of matter in quantum chromodynamics

Biology

* Blood pla ...

).

Plant tissue classification

For plants, the study of their tissues falls under the field of

For plants, the study of their tissues falls under the field of plant anatomy

Plant anatomy or phytotomy is the general term for the study of the internal structure of plants. Originally it included plant morphology, the description of the physical form and external structure of plants, but since the mid-20th century plant ...

, with the following four main types:

* Dermal tissue

The epidermis (from the Greek ''ἐπιδερμίς'', meaning "over-skin") is a single layer of cells that covers the leaves, flowers, roots and stems of plants. It forms a boundary between the plant and the external environment. The epidermis ...

* Vascular tissue

Vascular tissue is a complex conducting tissue, formed of more than one cell type, found in vascular plants. The primary components of vascular tissue are the xylem and phloem. These two tissues transport fluid and nutrients internally. There ...

* Ground tissue

The ground tissue of plants includes all tissues that are neither Epidermis (botany), dermal nor Vascular tissue, vascular. It can be divided into three types based on the nature of the cell walls.

# Parenchyma cells have thin primary walls and ...

* Meristematic tissue

The meristem is a type of biological tissue, tissue found in plants. It consists of undifferentiated cells (meristematic cells) capable of mitosis, cell division. Cells in the meristem can develop into all the other tissues and organs that occur i ...

Medical histology

Histopathology

Histopathology (compound of three Greek words: ''histos'' "tissue", πάθος ''pathos'' "suffering", and -λογία '' -logia'' "study of") refers to the microscopic examination of tissue in order to study the manifestations of disease. Spe ...

is the branch of histology that includes the microscopic identification and study of diseased tissue. It is an important part of anatomical pathology

Anatomical pathology (''Commonwealth'') or Anatomic pathology (''U.S.'') is a medical specialty that is concerned with the diagnosis of disease based on the macroscopic, microscopic, biochemical, immunologic and molecular examination ...

and surgical pathology

Surgical pathology is the most significant and time-consuming area of practice for most anatomical pathologists. Surgical pathology involves gross and microscopic examination of surgical specimens, as well as biopsies submitted by surgeons and ...

, as accurate diagnosis of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Possible signs and symptoms include a lump, abnormal b ...

and other diseases often requires histopathological examination of tissue samples. Trained physicians, frequently licensed pathologist

Pathology is the study of the causal, causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when us ...

s, perform histopathological examination and provide diagnostic information based on their observations.

Occupations

The field of histology that includes the preparation of tissues for microscopic examination is known as histotechnology. Job titles for the trained personnel who prepare histological specimens for examination are numerous and include histotechnicians, histotechnologists, histology technicians and technologists, medical laboratory technicians, andbiomedical scientist A biomedical scientist is a scientist trained in biology, particularly in the context of medical laboratory sciences or laboratory medicine. These scientists work to gain knowledge on the main principles of how the human body works and to find new w ...

s.

Sample preparation

Most histological samples need preparation before microscopic observation; these methods depend on the specimen and method of observation.Fixation

Chemical fixatives are used to preserve and maintain the structure of tissues and cells; fixation also hardens tissues which aids in cutting the thin sections of tissue needed for observation under the microscope. Fixatives generally preserve tissues (and cells) by irreversibly cross-linking proteins. The most widely used fixative for light microscopy is 10% neutral buffered

Chemical fixatives are used to preserve and maintain the structure of tissues and cells; fixation also hardens tissues which aids in cutting the thin sections of tissue needed for observation under the microscope. Fixatives generally preserve tissues (and cells) by irreversibly cross-linking proteins. The most widely used fixative for light microscopy is 10% neutral buffered formalin

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section Fo ...

, or NBF (4% formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section F ...

in phosphate buffered saline

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) is a buffer solution (pH ~ 7.4) commonly used in biological research. It is a water-based salt solution containing disodium hydrogen phosphate, sodium chloride and, in some formulations, potassium chloride and potass ...

).

For electron microscopy, the most commonly used fixative is glutaraldehyde

Glutaraldehyde is an organic compound with the formula . The molecule consists of a five carbon chain doubly terminated with formyl (CHO) groups. It is usually used as a solution in water, and such solutions exists as a collection of hydrates, c ...

, usually as a 2.5% solution in phosphate buffered saline

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) is a buffer solution (pH ~ 7.4) commonly used in biological research. It is a water-based salt solution containing disodium hydrogen phosphate, sodium chloride and, in some formulations, potassium chloride and potass ...

. Other fixatives used for electron microscopy are osmium tetroxide

Osmium tetroxide (also osmium(VIII) oxide) is the chemical compound with the formula OsO4. The compound is noteworthy for its many uses, despite its toxicity and the rarity of osmium. It also has a number of unusual properties, one being that the ...

or uranyl acetate

Uranyl acetate is the acetate salt of uranium oxide, a toxic yellow-green powder useful in certain laboratory tests. Structurally, it is a coordination polymer with formula UO2(CH3CO2)2(H2O)·H2O.

Structure

In the polymer, uranyl (UO22+) c ...

.

The main action of these aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred to as an aldehyde but can also be classified as a formyl grou ...

fixatives is to cross-link amino groups in proteins through the formation of methylene bridge

In organic chemistry, a methylene bridge, methylene spacer, or methanediyl group is any part of a molecule with formula ; namely, a carbon atom bound to two hydrogen atoms and connected by single bonds to two other distinct atoms in the rest of ...

s (-CH2-), in the case of formaldehyde, or by C5H10 cross-links in the case of glutaraldehyde. This process, while preserving the structural integrity of the cells and tissue can damage the biological functionality of proteins, particularly enzymes

Enzymes () are proteins that act as biological catalysts by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different molecule ...

.

Formalin fixation leads to degradation of mRNA, miRNA, and DNA as well as denaturation and modification of proteins in tissues. However, extraction and analysis of nucleic acids and proteins from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues is possible using appropriate protocols.

Selection and trimming

''Selection'' is the choice of relevant tissue in cases where it is not necessary to put the entire original tissue mass through further processing. The remainder may remain fixated in case it needs to be examined at a later time. ''Trimming'' is the cutting of tissue samples in order to expose the relevant surfaces for later sectioning. It also creates tissue samples of appropriate size to fit into cassettes.Embedding

Tissues are embedded in a harder medium both as a support and to allow the cutting of thin tissue slices. In general, water must first be removed from tissues (dehydration) and replaced with a medium that either solidifies directly, or with an intermediary fluid (clearing) that is miscible with the embedding media.Paraffin wax

For light microscopy,

For light microscopy, paraffin wax

Paraffin wax (or petroleum wax) is a soft colorless solid derived from petroleum, coal, or oil shale that consists of a mixture of hydrocarbon molecules containing between 20 and 40 carbon atoms. It is solid at room temperature and begins to m ...

is the most frequently used embedding material. Paraffin is immiscible with water, the main constituent of biological tissue, so it must first be removed in a series of dehydration steps. Samples are transferred through a series of progressively more concentrated ethanol

Ethanol (abbr. EtOH; also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound. It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol with the chemical formula . Its formula can be also written as or (an ethyl ...

baths, up to 100% ethanol to remove remaining traces of water. Dehydration is followed by a ''clearing agent'' (typically xylene

In organic chemistry, xylene or xylol (; IUPAC name: dimethylbenzene) are any of three organic compounds with the formula . They are derived from the substitution of two hydrogen atoms with methyl groups in a benzene ring; which hydrogens are sub ...

although other environmental safe substitutes are in use) which removes the alcohol and is miscible

Miscibility () is the property of two substances to mix in all proportions (that is, to fully dissolve in each other at any concentration), forming a homogeneous mixture (a solution). The term is most often applied to liquids but also applies ...

with the wax, finally melted paraffin wax is added to replace the xylene and infiltrate the tissue. In most histology, or histopathology laboratories the dehydration, clearing, and wax infiltration are carried out in ''tissue processors'' which automate this process. Once infiltrated in paraffin, tissues are oriented in molds which are filled with wax; once positioned, the wax is cooled, solidifying the block and tissue.

Other materials

Paraffin wax does not always provide a sufficiently hard matrix for cutting very thin sections (which are especially important for electron microscopy). Paraffin wax may also be too soft in relation to the tissue, the heat of the melted wax may alter the tissue in undesirable ways, or the dehydrating or clearing chemicals may harm the tissue. Alternatives to paraffin wax include,epoxy

Epoxy is the family of basic components or cured end products of epoxy resins. Epoxy resins, also known as polyepoxides, are a class of reactive prepolymers and polymers which contain epoxide groups. The epoxide functional group is also coll ...

, acrylic

Acrylic may refer to:

Chemicals and materials

* Acrylic acid, the simplest acrylic compound

* Acrylate polymer, a group of polymers (plastics) noted for transparency and elasticity

* Acrylic resin, a group of related thermoplastic or thermosett ...

, agar

Agar ( or ), or agar-agar, is a jelly-like substance consisting of polysaccharides obtained from the cell walls of some species of red algae, primarily from ogonori (''Gracilaria'') and "tengusa" (''Gelidiaceae''). As found in nature, agar is ...

, gelatin

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

, celloidin, and other types of waxes.

In electron microscopy epoxy resins are the most commonly employed embedding media, but acrylic resins are also used, particularly where immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the most common application of immunostaining. It involves the process of selectively identifying antigens (proteins) in cells of a tissue section by exploiting the principle of antibodies binding specifically to an ...

is required.

For tissues to be cut in a frozen state, tissues are placed in a water-based embedding medium. Pre-frozen tissues are placed into molds with the liquid embedding material, usually a water-based glycol, OCT, TBS, Cryogen, or resin, which is then frozen to form hardened blocks.

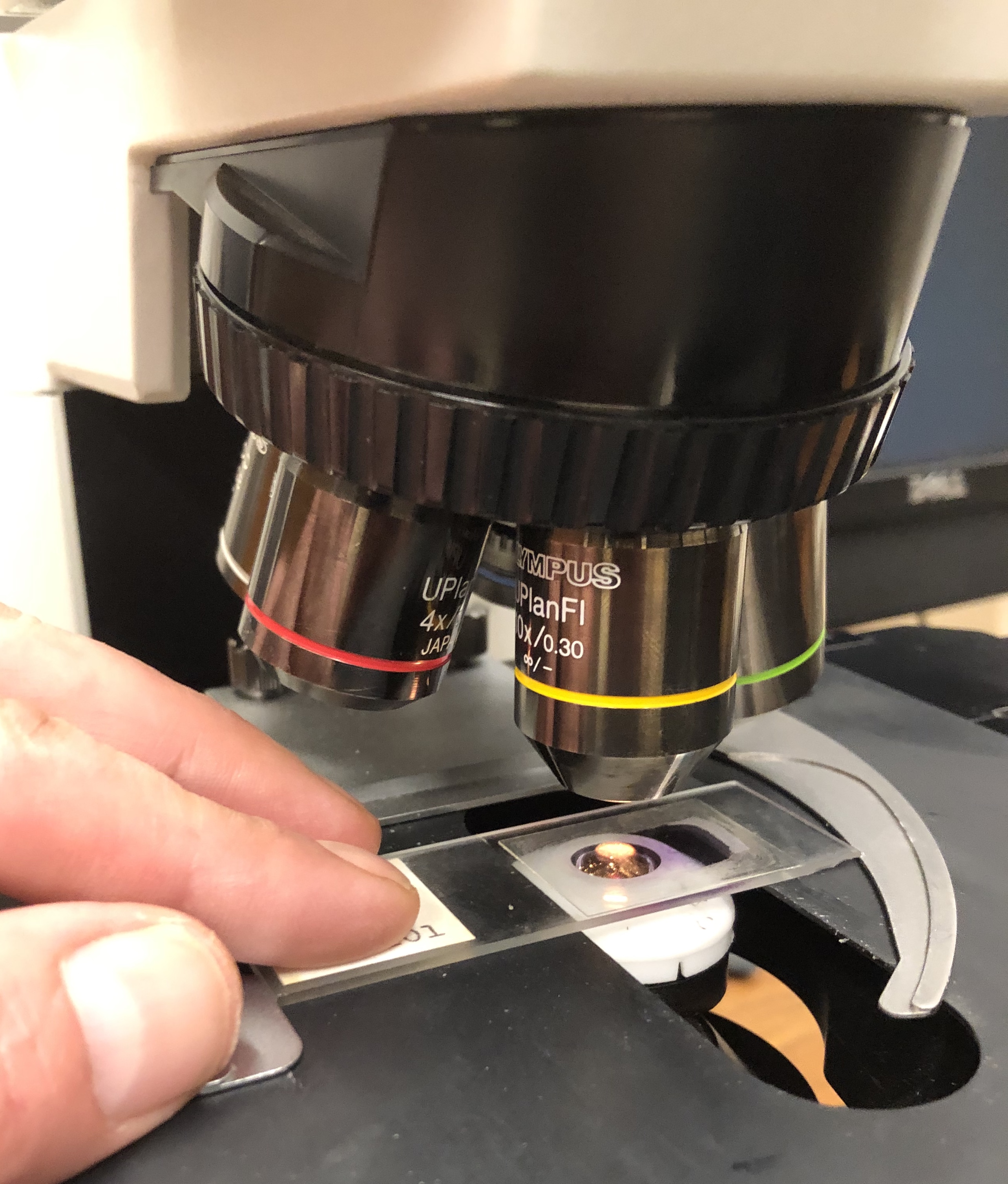

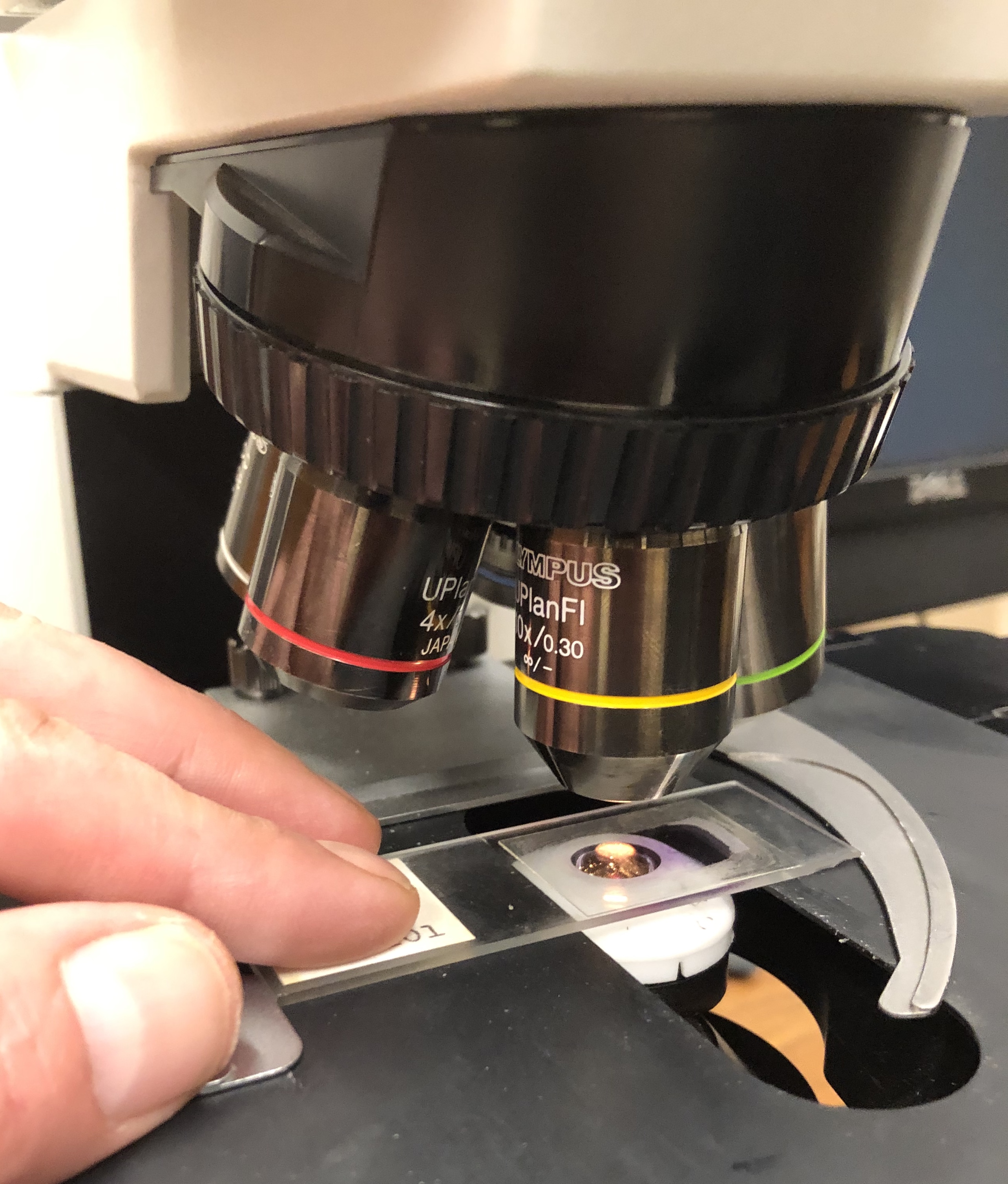

Sectioning

For light microscopy, a knife mounted in a microtome is used to cut tissue sections (typically between 5-15

For light microscopy, a knife mounted in a microtome is used to cut tissue sections (typically between 5-15 micrometers

The micrometre (American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American and British English spelling differences# ...

thick) which are mounted on a glass microscope slide

A microscope slide is a thin flat piece of glass, typically 75 by 26 mm (3 by 1 inches) and about 1 mm thick, used to hold objects for examination under a microscope. Typically the object is mounted (secured) on the slide, and then b ...

. For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), a diamond or glass knife mounted in an ultramicrotome

A microtome (from the Greek ''mikros'', meaning "small", and ''temnein'', meaning "to cut") is a cutting tool used to produce extremely thin slices of material known as ''sections''. Important in science, microtomes are used in microscopy, allo ...

is used to cut between 50 and 150 nanometer

330px, Different lengths as in respect to the molecular scale.

The nanometre (international spelling as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: nm) or nanometer (American and British English spelling differences#-re ...

thick tissue sections.

Staining

Biological tissue has little inherent contrast in either the light or electron microscope.Staining

Staining is a technique used to enhance contrast in samples, generally at the microscopic level. Stains and dyes are frequently used in histology (microscopic study of biological tissues), in cytology (microscopic study of cells), and in the ...

is employed to give both contrast to the tissue as well as highlighting particular features of interest. When the stain is used to target a specific chemical component of the tissue (and not the general structure), the term histochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the most common application of immunostaining. It involves the process of selectively identifying antigens (proteins) in cells of a tissue section by exploiting the principle of antibodies binding specifically to ant ...

is used.

Light microscopy

Hematoxylin

Haematoxylin or hematoxylin (), also called natural black 1 or C.I. 75290, is a compound extracted from heartwood of the logwood tree (''Haematoxylum campechianum'') with a chemical formula of . This naturally derived dye has been used as a h ...

and eosin

Eosin is the name of several fluorescent acidic compounds which bind to and form salts with basic, or eosinophilic, compounds like proteins containing amino acid residues such as arginine and lysine, and stains them dark red or pink as a resul ...

(H&E stain

Hematoxylin and eosin stain ( or haematoxylin and eosin stain or hematoxylin-eosin stain; often abbreviated as H&E stain or HE stain) is one of the principal tissue stains used in histology. It is the most widely used stain in medical diagnos ...

) is one of the most commonly used stains in histology to show the general structure of the tissue. Hematoxylin stains cell nuclei blue; eosin, an acidic

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

dye, stains the cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. The ...

and other tissues in different stains of pink.

In contrast to H&E, which is used as a general stain, there are many techniques that more selectively stain cells, cellular components, and specific substances. A commonly performed histochemical technique that targets a specific chemical is the Perls' Prussian blue

In histology, histopathology, and clinical pathology, Perls Prussian blue is a commonly used method to detect the presence of iron in tissue or cell samples. Perls Prussian Blue derives its name from the German pathologist Max Perls (1843–1881 ...

reaction, used to demonstrate iron deposits in diseases like hemochromatosis

Iron overload or hemochromatosis (also spelled ''haemochromatosis'' in British English) indicates increased total accumulation of iron in the body from any cause and resulting organ damage. The most important causes are hereditary haemochromatosi ...

. The Nissl method

Franz Alexander Nissl (9 September 1860, in Frankenthal – 11 August 1919, in Munich) was a German psychiatrist and medical researcher. He was a noted neuropathologist.

Early life

Nissl was born in Frankenthal to Theodor Nissl and Maria Haas. ...

for Nissl substance and Golgi's method

Golgi's method is a silver staining technique that is used to visualize nervous tissue under light microscopy. The method was discovered by Camillo Golgi, an Italian physician and scientist, who published the first picture made with the technique ...

(and related silver stains In pathology, silver staining is the use of silver to selectively alter the appearance of a target in microscopy of histological sections; in temperature gradient gel electrophoresis; and in polyacrylamide gels.

In traditional stained glass, silve ...

) are useful in identifying neuron

A neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that communicates with other cells via specialized connections called synapses. The neuron is the main component of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and placozoa. N ...

s are other examples of more specific stains.

Historadiography

Inhistoradiography Historadiography is a technique formerly utilized in the fields of histology and cellular biology to provide semiquantitative information regarding the density of a tissue sample. It is usually synonymous with microradiography. This is achieved by ...

, a slide (sometimes stained histochemically) is X-rayed. More commonly, autoradiography

An autoradiograph is an image on an X-ray film or nuclear emulsion produced by the pattern of decay emissions (e.g., beta particles or gamma rays) from a distribution of a radioactive substance. Alternatively, the autoradiograph is also available ...

is used in visualizing the locations to which a radioactive substance has been transported within the body, such as cells in S phase

S phase (Synthesis Phase) is the phase of the cell cycle in which DNA is replicated, occurring between G1 phase and G2 phase. Since accurate duplication of the genome is critical to successful cell division, the processes that occur during ...

(undergoing DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all living organisms acting as the most essential part for biological inheritanc ...

) which incorporate tritiated thymidine

Thymidine (symbol dT or dThd), also known as deoxythymidine, deoxyribosylthymine, or thymine deoxyriboside, is a pyrimidine deoxynucleoside. Deoxythymidine is the DNA nucleoside T, which pairs with deoxyadenosine (A) in double-stranded DNA. I ...

, or sites to which radiolabeled nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

probes bind in in situ hybridization

''In situ'' hybridization (ISH) is a type of hybridization that uses a labeled complementary DNA, RNA or modified nucleic acids strand (i.e., probe) to localize a specific DNA or RNA sequence in a portion or section of tissue (''in situ'') or ...

. For autoradiography on a microscopic level, the slide is typically dipped into liquid nuclear tract emulsion, which dries to form the exposure film. Individual silver grains in the film are visualized with dark field microscopy

Dark-field microscopy (also called dark-ground microscopy) describes microscopy methods, in both light and electron microscopy, which exclude the unscattered beam from the image. As a result, the field around the specimen (i.e., where there is ...

.

Immunohistochemistry

Recently,antibodies

An antibody (Ab), also known as an immunoglobulin (Ig), is a large, Y-shaped protein used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as pathogenic bacteria and viruses. The antibody recognizes a unique molecule of the ...

have been used to specifically visualize proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids. This process is called immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is the most common application of immunostaining. It involves the process of selectively identifying antigens (proteins) in cells of a tissue section by exploiting the principle of antibodies binding specifically to an ...

, or when the stain is a fluorescent

Fluorescence is the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. It is a form of luminescence. In most cases, the emitted light has a longer wavelength, and therefore a lower photon energy, tha ...

molecule, immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence is a technique used for light microscopy with a fluorescence microscope and is used primarily on microbiological samples. This technique uses the specificity of antibodies to their antigen to target fluorescent dyes to specif ...

. This technique has greatly increased the ability to identify categories of cells under a microscope. Other advanced techniques, such as nonradioactive ''in situ'' hybridization, can be combined with immunochemistry to identify specific DNA or RNA molecules with fluorescent probes or tags that can be used for immunofluorescence and enzyme-linked fluorescence amplification (especially alkaline phosphatase

The enzyme alkaline phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.1, alkaline phosphomonoesterase; phosphomonoesterase; glycerophosphatase; alkaline phosphohydrolase; alkaline phenyl phosphatase; orthophosphoric-monoester phosphohydrolase (alkaline optimum), systematic ...

and tyramide signal amplification). Fluorescence microscopy

A fluorescence microscope is an optical microscope that uses fluorescence instead of, or in addition to, scattering, reflection, and attenuation or absorption, to study the properties of organic or inorganic substances. "Fluorescence microsc ...

and confocal microscopy

Confocal microscopy, most frequently confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) or laser confocal scanning microscopy (LCSM), is an optical imaging technique for increasing optical resolution and contrast of a micrograph by means of using a sp ...

are used to detect fluorescent signals with good intracellular detail.

Electron microscopy

For electron microscopyheavy metals

upright=1.2, Crystals of osmium, a heavy metal nearly twice as dense as lead">lead.html" ;"title="osmium, a heavy metal nearly twice as dense as lead">osmium, a heavy metal nearly twice as dense as lead

Heavy metals are generally defined as ...

are typically used to stain tissue sections. Uranyl acetate

Uranyl acetate is the acetate salt of uranium oxide, a toxic yellow-green powder useful in certain laboratory tests. Structurally, it is a coordination polymer with formula UO2(CH3CO2)2(H2O)·H2O.

Structure

In the polymer, uranyl (UO22+) c ...

and lead citrate are commonly used to impart contrast to tissue in the electron microscope.

Specialized techniques

Cryosectioning

Similar to thefrozen section procedure

The frozen section procedure is a pathological laboratory procedure to perform rapid microscopic analysis of a specimen. It is used most often in oncological surgery. The technical name for this procedure is cryosection. The microtome device that ...

employed in medicine, cryosectioning is a method to rapidly freeze, cut, and mount sections of tissue for histology. The tissue is usually sectioned on a cryostat

A cryostat (from ''cryo'' meaning cold and ''stat'' meaning stable) is a device used to maintain low cryogenic temperatures of samples or devices mounted within the cryostat. Low temperatures may be maintained within a cryostat by using various ...

or freezing microtome. The frozen sections are mounted on a glass slide and may be stained to enhance the contrast between different tissues. Unfixed frozen sections can be used for studies requiring enzyme localization in tissues and cells. Tissue fixation is required for certain procedures such as antibody-linked immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence is a technique used for light microscopy with a fluorescence microscope and is used primarily on microbiological samples. This technique uses the specificity of antibodies to their antigen to target fluorescent dyes to specif ...

staining. Frozen sections are often prepared during surgical removal of tumor

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

s to allow rapid identification of tumor margins, as in Mohs surgery

Mohs surgery, developed in 1938 by a general surgeon, Frederic E. Mohs, is microscopically controlled surgery used to treat both common and rare types of skin cancer. During the surgery, after each removal of tissue and while the patient waits, t ...

, or determination of tumor malignancy, when a tumor is discovered incidentally during surgery.

Ultramicrotomy

Ultramicrotomy is a method of preparing extremely thin sections fortransmission electron microscope

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is a microscopy technique in which a beam of electrons is transmitted through a specimen to form an image. The specimen is most often an ultrathin section less than 100 nm thick or a suspension on a gr ...

(TEM) analysis. Tissues are commonly embedded in epoxy

Epoxy is the family of basic components or cured end products of epoxy resins. Epoxy resins, also known as polyepoxides, are a class of reactive prepolymers and polymers which contain epoxide groups. The epoxide functional group is also coll ...

or other plastic resin. Very thin sections (less than 0.1 micrometer in thickness) are cut using diamond or glass knives on an ultramicrotome

A microtome (from the Greek ''mikros'', meaning "small", and ''temnein'', meaning "to cut") is a cutting tool used to produce extremely thin slices of material known as ''sections''. Important in science, microtomes are used in microscopy, allo ...

.

Artifacts

Artifacts are structures or features in tissue that interfere with normal histological examination. Artifacts interfere with histology by changing the tissues appearance and hiding structures. Tissue processing artifacts can include pigments formed by fixatives, shrinkage, washing out of cellular components, color changes in different tissues types and alterations of the structures in the tissue. An example is mercury pigment left behind after using Zenker's fixative to fix a section. Formalin fixation can also leave a brown to black pigment under acidic conditions.History

In the 17th century the Italian

In the 17th century the Italian Marcello Malpighi

Marcello Malpighi (10 March 1628 – 30 November 1694) was an Italian biologist and physician, who is referred to as the "Founder of microscopical anatomy, histology & Father of physiology and embryology". Malpighi's name is borne by several phy ...

used microscopes to study tiny biological entities; some regard him as the founder of the fields of histology and microscopic pathology. Malpighi analyzed several parts of the organs of bats, frogs and other animals under the microscope. While studying the structure of the lung, Malpighi noticed its membranous alveoli and the hair-like connections between veins and arteries, which he named capillaries. His discovery established how the oxygen breathed in enters the blood stream and serves the body.

In the 19th century histology was an academic discipline in its own right. The French anatomist Xavier Bichat

Marie François Xavier Bichat (; ; 14 November 1771 – 22 July 1802) was a French anatomist and pathologist, known as the father of modern histology. Although he worked without a microscope, Bichat distinguished 21 types of elementary tissues ...

introduced the concept of tissue in anatomy in 1801, and the term "histology" ( de , Histologie), coined to denote the "study of tissues", first appeared in a book by Karl Meyer in 1819. Bichat described twenty-one human tissues, which can be subsumed under the four categories currently accepted by histologists. The usage of illustrations in histology, deemed as useless by Bichat, was promoted by Jean Cruveilhier

Jean Cruveilhier (; 9 February 1791 – 7 March 1874) was a French anatomist and pathologist.

Academic career

Cruveilhier was born in Limoges, France. As a student in Limoges, he planned to enter the priesthood. He later developed an inte ...

.

In the early 1830s Purkynĕ invented a microtome with high precision.

During the 19th century many fixation techniques were developed by Adolph Hannover

Adolph Hannover (24 November 1814 - 7 July 1894) was a Danish pathologist who in 1843 carried out the first definitive microscopic description of a cancer cell. Hannover is said to have introduced the microscope to Denmark, but his work had wides ...

(solutions of chromates and chromic acid

The term chromic acid is usually used for a mixture made by adding concentrated sulfuric acid to a dichromate, which may contain a variety of compounds, including solid chromium trioxide. This kind of chromic acid may be used as a cleaning mixt ...

), Franz Schulze and Max Schultze

Max Johann Sigismund Schultze (25 March 1825 – 16 January 1874) was a German microscopic anatomist noted for his work on cell theory.

Biography

Schultze was born in Freiburg im Breisgau (Baden). He studied medicine at Greifswald and Berlin, and ...

(osmic acid

Osmium tetroxide (also osmium(VIII) oxide) is the chemical compound with the formula OsO4. The compound is noteworthy for its many uses, despite its toxicity and the rarity of osmium. It also has a number of unusual properties, one being that th ...

), Alexander Butlerov

Alexander Mikhaylovich Butlerov (Алекса́ндр Миха́йлович Бу́тлеров; 15 September 1828 – 17 August 1886) was a Russian chemist, one of the principal creators of the theory of chemical structure (1857–1861 ...

(formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is a naturally occurring organic compound with the formula and structure . The pure compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde (refer to section F ...

) and Benedikt Stilling (freezing

Freezing is a phase transition where a liquid turns into a solid when its temperature is lowered below its freezing point. In accordance with the internationally established definition, freezing means the solidification phase change of a liquid o ...

).

Mounting techniques were developed by Rudolf Heidenhain

Rudolf Peter Heinrich Heidenhain (; 29 January 1834 – 13 October 1897) was a German physiologist born in Marienwerder, East Prussia (now Kwidzyn, Poland). His son, Martin Heidenhain, was a highly regarded anatomist.

Academic career

He studie ...

(1824-1898), who introduced gum Arabic

Gum arabic, also known as gum sudani, acacia gum, Arabic gum, gum acacia, acacia, Senegal gum, Indian gum, and by other names, is a natural gum originally consisting of the hardened sap of two species of the '' Acacia'' tree, ''Senegalia sen ...

; Salomon Stricker

Salomon Stricker (1 January 1834 – 2 April 1898) was an Austrian pathologist and histologist.

Career

Stricker was born in Waag-Neustadtl (Hungarian: Vágújhely, now Nové Mesto nad Váhom in Slovakia). He studied at the University of Vienna, ...

(1834-1898), who advocated a mixture of wax and oil; and Andrew Pritchard

Andrew Pritchard FRSE (14 December 1804 – 24 November 1882) was an English naturalist and natural history dealer who made significant improvements to microscopy and studied microscopic organisms. His belief that God and nature were one led him ...

(1804-1884) who, in 1832, used a gum/isinglass

Isinglass () is a substance obtained from the dried swim bladders of fish. It is a form of collagen used mainly for the clarification or fining of some beer and wine. It can also be cooked into a paste for specialised gluing purposes.

The E ...

mixture. In the same year, Canada balsam appeared on the scene, and in 1869 Edwin Klebs

Theodor Albrecht Edwin Klebs (6 February 1834 – 23 October 1913) was a German-Swiss microbiologist. He is mainly known for his work on infectious diseases. His works paved the way for the beginning of modern bacteriology, and inspired Louis Pas ...

(1834-1913) reported that he had for some years embedded his specimens in paraffin.

The 1906 Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; sv, Nobelpriset ; no, Nobelprisen ) are five separate prizes that, according to Alfred Nobel's will of 1895, are awarded to "those who, during the preceding year, have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind." Alfr ...

in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to histologists Camillo Golgi

Camillo Golgi (; 7 July 184321 January 1926) was an Italian biologist and pathologist known for his works on the central nervous system. He studied medicine at the University of Pavia (where he later spent most of his professional career) betwee ...

and Santiago Ramon y Cajal

Santiago (, ; ), also known as Santiago de Chile, is the capital and largest city of Chile as well as one of the largest cities in the Americas. It is the center of Chile's most densely populated region, the Santiago Metropolitan Region, whose ...

. They had conflicting interpretations of the neural structure of the brain based on differing interpretations of the same images. Ramón y Cajal won the prize for his correct theory, and Golgi for the silver-staining technique

Technique or techniques may refer to:

Music

* The Techniques, a Jamaican rocksteady vocal group of the 1960s

*Technique (band), a British female synth pop band in the 1990s

* ''Technique'' (album), by New Order, 1989

* ''Techniques'' (album), by M ...

that he invented to make it possible.

Future directions

''In vivo'' histology

Currently there is intense interest in developing techniques for ''in vivo'' histology (predominantly usingMRI

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a medical imaging technique used in radiology to form pictures of the anatomy and the physiological processes of the body. MRI scanners use strong magnetic fields, magnetic field gradients, and radio waves ...

), which would enable doctors to non-invasively gather information about healthy and diseased tissues in living patients, rather than from fixed tissue samples.

Notes

References

External links

* {{Authority control Histotechnology Staining Histochemistry Anatomy