Herakleitos Of Ephesos on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of

The main primary source for the life of Heraclitus is the

The main primary source for the life of Heraclitus is the

Heraclitus is said to have produced a single work on

Heraclitus is said to have produced a single work on

The hallmark of Heraclitus' philosophy is

The hallmark of Heraclitus' philosophy is

Like the Milesians before him,

Like the Milesians before him,

Heraclitus' writings have exerted a wide influence on

Heraclitus' writings have exerted a wide influence on

It is unknown whether or not Heraclitus had any students in his lifetime. Diogenes Laertius mentions an Antisthenes who wrote a commentary on Heraclitus.

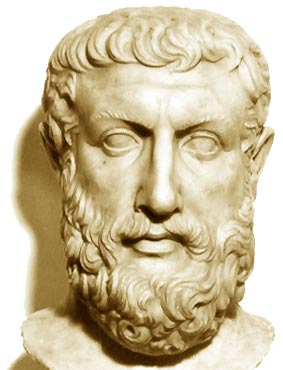

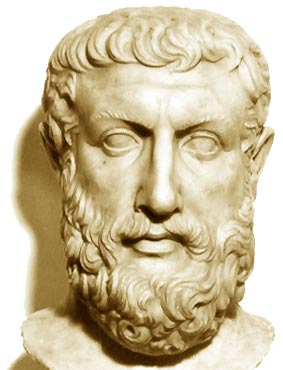

Parmenides, an

It is unknown whether or not Heraclitus had any students in his lifetime. Diogenes Laertius mentions an Antisthenes who wrote a commentary on Heraclitus.

Parmenides, an

Hera

In ancient Greek religion, Hera (; grc-gre, Ἥρα, Hḗrā; grc, Ἥρη, Hḗrē, label=none in Ionic and Homeric Greek) is the goddess of marriage, women and family, and the protector of women during childbirth. In Greek mythology, she ...

"; ) was an ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic peri ...

pre-Socratic

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of thes ...

philosopher from the city of Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

, which was then part of the Persian Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, wikt:𐎧𐏁𐏂𐎶, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an History of Iran#Classical antiquity, ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Bas ...

.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrote a single work, only fragments of which have survived. Most of the ancient stories about him are later said to be fabrications based on interpretations of the preserved fragments. His paradoxical philosophy and appreciation for wordplay and cryptic utterances has earned him the epithet "the obscure" since antiquity. He was considered a misanthrope

Misanthropy is the general hatred, dislike, distrust or contempt of the human species, human behavior or human nature. A misanthrope or misanthropist is someone who holds such views or feelings. The word's origin is from the Greek words μῖσ ...

who was subject to melancholia

Melancholia or melancholy (from el, µέλαινα χολή ',Burton, Bk. I, p. 147 meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly dep ...

. Consequently, he became known as "the weeping philosopher" in contrast to the ancient philosopher Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, who was known as "the laughing philosopher".

The central idea of Heraclitus' philosophy is the unity of opposites

The unity of opposites is the central category of dialectics, said to be related to the notion of non-duality in a deep sense.

. One of his most notable applications of this idea was to the concept of impermanence

Impermanence, also known as the philosophical problem of change, is a philosophical concept addressed in a variety of religions and philosophies. In Eastern philosophy it is notable for its role in the Buddhist three marks of existence. It is ...

; he saw the world as constantly in flux, changing as it remained the same, which he expressed in the saying, "No man ever steps in the same river twice." This changing aspect of his philosophy is contrasted with that of the ancient philosopher Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; grc-gre, Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family. His dates a ...

, who believed in "being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

" and in the static nature of the universe.

Life

The main primary source for the life of Heraclitus is the

The main primary source for the life of Heraclitus is the doxographer Doxography ( el, δόξα – "an opinion", "a point of view" + – "to write", "to describe") is a term used especially for the works of classical historians, describing the points of view of past philosophers and scientists. The term w ...

Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

; Although most of the information provided by Laertius is unreliable, the anecdote that Heraclitus relinquished the hereditary title of "king" to his younger brother may at least imply that Heraclitus was the eldest brother of an aristocratic family in Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

. In the 6th century BCE, Ephesus

Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἔφεσος, Éphesos; tr, Efes; may ultimately derive from hit, 𒀀𒉺𒊭, Apaša) was a city in ancient Greece on the coast of Ionia, southwest of present-day Selçuk in İzmir Province, Turkey. It was built in t ...

, like other cities in Ionia, was tied to both the rise of Lydia

Lydia (Lydian language, Lydian: 𐤮𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣𐤠, ''Śfarda''; Aramaic: ''Lydia''; el, Λυδία, ''Lȳdíā''; tr, Lidya) was an Iron Age Monarchy, kingdom of western Asia Minor located generally east of ancient Ionia in the mod ...

under Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

and to the overthrow of Croesus

Croesus ( ; Lydian: ; Phrygian: ; grc, Κροισος, Kroisos; Latin: ; reigned: c. 585 – c. 546 BC) was the king of Lydia, who reigned from 585 BC until his defeat by the Persian king Cyrus the Great in 547 or 546 BC.

Croesus was ...

by Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia (; peo, 𐎤𐎢𐎽𐎢𐏁 ), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire, the first Persian empire. Schmitt Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Under his rule, the empire embraced ...

. Ephesus appears to have cultivated a close relationship with the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

; during the suppression of the Ionian revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Persian rule, lasting from 499 BC to 493 BC. At the heart of the rebellion was the dissatisfac ...

in 494 BCE, Ephesus was spared and emerged as the dominant Greek city in Ionia. As the eldest son of one of the richest families in the city, Heraclitus appears to have had little sympathy for democracy, but he was not "an unconditional partisan of the rich." but instead as "withdrawn from competing factions" - similar to Solon of Athens.

Heraclitus is traditionally considered to have flourished in the 69th Olympiad (504-501 BCE), but this date may simply be based on a prior account synchronizing his life with the reign of Darius the Great

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his d ...

. Two extant letters between Heraclitus and Darius I

Darius I ( peo, 𐎭𐎠𐎼𐎹𐎺𐎢𐏁 ; grc-gre, Δαρεῖος ; – 486 BCE), commonly known as Darius the Great, was a Persian ruler who served as the third King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning from 522 BCE until his ...

, which are quoted by Diogenes Laërtius, are also later forgeries. However, this date can be considered "roughly accurate" based on a fragment that references Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samos, Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionians, Ionian Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher and the eponymou ...

, Xenophanes

Xenophanes of Colophon (; grc, Ξενοφάνης ὁ Κολοφώνιος ; c. 570 – c. 478 BC) was a Greek philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φ ...

, and Hecataeus as older contemporaries, which would place him near the end of the sixth century BCE.

Writings

Heraclitus is said to have produced a single work on

Heraclitus is said to have produced a single work on papyrus

Papyrus ( ) is a material similar to thick paper that was used in ancient times as a writing surface. It was made from the pith of the papyrus plant, '' Cyperus papyrus'', a wetland sedge. ''Papyrus'' (plural: ''papyri'') can also refer to a ...

, which has not survived; however, over 100 fragments of this work survive in quotations by other authors. The title is unknown, but many later philosophers in this period refer to this work as ''On Nature''. Diogenes Laertius states that the book was divided into three parts, but Burnet notes that "it is not to be supposed that this division is due to eraclitushimself; all we can infer is that the work fell naturally into these parts when the Stoic

Stoic may refer to:

* An adherent of Stoicism; one whose moral quality is associated with that school of philosophy

*STOIC, a programming language

* ''Stoic'' (film), a 2009 film by Uwe Boll

* ''Stoic'' (mixtape), a 2012 mixtape by rapper T-Pain

*' ...

commentators took their editions of it in hand. Martin Litchfield West

Martin Litchfield West, (23 September 1937 – 13 July 2015) was a British philologist and classical scholar. In recognition of his contribution to scholarship, he was awarded the Order of Merit in 2014.

West wrote on ancient Greek music, Gree ...

notes that the existing fragments do not give much of an idea of the overall structure, but that the beginning of the discourse can probably be determined, starting with the opening lines, which are quoted by Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and ...

Some classicists and professors of ancient philosophy have disputed which of these fragments can truly be attributed to Heraclitus. M. M. McCabe

Mary Margaret Anne McCabe (born 18 December 1948), known as M. M. McCabe, is emerita professor of ancient philosophy at King's College London. She has written books on Plato and other ancient philosophers, including the pre-Socratics, Socrate ...

has argued that the three statements on rivers should all be read as fragments from a discourse. McCabe suggests reading them as though they arose in succession. The three fragments "could be retained, and arranged in an argumentative sequence". In McCabe's reading of the fragments, Heraclitus can be read as a philosopher capable of sustained argument

An argument is a statement or group of statements called premises intended to determine the degree of truth or acceptability of another statement called conclusion. Arguments can be studied from three main perspectives: the logical, the dialectic ...

, rather than just aphorism

An aphorism (from Greek ἀφορισμός: ''aphorismos'', denoting 'delimitation', 'distinction', and 'definition') is a concise, terse, laconic, or memorable expression of a general truth or principle. Aphorisms are often handed down by tra ...

.

According to Diogenes Laërtius

Diogenes Laërtius ( ; grc-gre, Διογένης Λαέρτιος, ; ) was a biographer of the Ancient Greece, Greek philosophers. Nothing is definitively known about his life, but his surviving ''Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers'' is a ...

, Heraclitus deposited the book in the Artemisium

Artemisium or Artemision (Greek: Ἀρτεμίσιον) is a cape in northern Euboea, Greece. The legendary hollow cast bronze statue of Zeus, or possibly Poseidon, known as the ''Artemision Bronze'', was found off this cape in a sunken ship,Wo ...

as a dedication. Kahn states: "Down to the time of Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

and Clement

Clement or Clément may refer to:

People

* Clement (name), a given name and surname

* Saint Clement (disambiguation)#People

Places

* Clément, French Guiana, a town

* Clement, Missouri, U.S.

* Clement Township, Michigan, U.S.

Other uses

* ...

, if not later, the little book of Heraclitus was available in its original form to any reader who chose to seek it out". Laërtius comments on the notability of the text, stating: "The book acquired such fame that it produced partisans of his philosophy who were called Heracliteans". Prominent philosophers identified today as Heracliteans include Cratylus

Cratylus ( ; grc, Κρατύλος, ''Kratylos'') was an ancient Athenian philosopher from the mid-late 5th century BCE, known mostly through his portrayal in Plato's dialogue '' Cratylus''. He was a radical proponent of Heraclitean philosophy ...

and Antisthenes

Antisthenes (; el, Ἀντισθένης; 446 366 BCE) was a Greek philosopher and a pupil of Socrates. Antisthenes first learned rhetoric under Gorgias before becoming an ardent disciple of Socrates. He adopted and developed the ethical side o ...

—not to be confused with the cynic Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

quotes part of the opening line in the ''Rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

'' to outline the difficulty in punctuating Heraclitus without ambiguity; he debated whether "forever" applied to "being" or to "prove". Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routledge ...

says (in Diogenes Laërtius) "some parts of his work rehalf-finished, while other parts ade

Ade, Adé, or ADE may refer to:

Aeronautics

*Ada Air's ICAO code

* Aden International Airport's IATA code

*Aeronautical Development Establishment, a laboratory of the DRDO in India

Medical

* Adverse Drug Event

*Antibody-dependent enhancement

* A ...

a strange medley". According to Diogenes Laërtius, Timon of Phlius

Timon of Phlius ( ; grc, Τίμων ὁ Φλιάσιος, Tímōn ho Phliásios, , ; BCc. 235 BC) was a Greek Pyrrhonist philosopher, a pupil of Pyrrho, and a celebrated writer of satirical poems called ''Silloi'' (). He was born in P ...

called Heraclitus "the Riddler" (; ), saying Heraclitus wrote his book "rather unclearly" (''asaphesteron''); according to Timon, this was intended to allow only the "capable" to attempt it. By the time of Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, this epithet became "The Obscure" (; ) as he had spoken ''nimis obscurē'' ("too obscurely") concerning nature and had done so deliberately in order to be misunderstood. By the time of Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia (; el, Σιμπλίκιος ὁ Κίλιξ; c. 490 – c. 560 AD) was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian i ...

, a 6th century neoplatonic philosopher, who mentions Heraclitus 32 times but never quotes from him, Heraclitus' work was so rare that it was unavailable even to Simplicius and the other scholars at the Platonic Academy in Athens.

Flux and unity of opposites

flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport ph ...

and the unity of opposites

The unity of opposites is the central category of dialectics, said to be related to the notion of non-duality in a deep sense.

: Diogenes Laërtius summarizes Heraclitus's philosophy, stating; "All things come into being by conflict of opposites, and the sum of things ( ''ta hola'' ("the whole")) flows like a stream". Two fragments relating to this concept state, "As the same thing in us is living and dead, waking and sleeping, young and old. For these things having changed around are those, and those in turn having changed around are these" (B88) and "Cold things warm up, the hot cools off, wet becomes dry, dry becomes wet" (B126).

Heraclitus' doctrine on the unity of opposites suggests that unity of the world and its various parts is kept through the tension produced by the opposites. Furthermore, each polar substance contains its opposite, in a continual circular exchange and motion that results in the stability of the cosmos. Another of Heraclitus' famous axioms highlights this doctrine (B53): "War is father of all and king of all; and some he manifested as gods, some as men; some he made slaves, some free", where war means the creative tension that brings things into existence. In this union of opposites, of both generation and destruction, Heraclitus called the oppositional processes (), " strife", and hypothesizes the apparently stable state, (), "justice

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspective ...

", is a harmony

In music, harmony is the process by which individual sounds are joined together or composed into whole units or compositions. Often, the term harmony refers to simultaneously occurring frequencies, pitches ( tones, notes), or chords. However ...

of it, which Anaximander

Anaximander (; grc-gre, Ἀναξίμανδρος ''Anaximandros''; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 1, p. 403. a city of Ionia (in moder ...

described as injustice. Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

said Heraclitus disliked Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of the ...

because Homer wished that strife would leave the world, which according to Heraclitus would destroy the world; "there would be no harmony without high and low notes, and no animals without male and female, which are opposites".

Jonathan Barnes

Jonathan Barnes, British Academy, FBA (born 26 December 1942 in Wenlock, Shropshire) is an English scholar of Aristotelianism, Aristotelian and ancient philosophy.

Education and career

He was educated at the City of London School and Balliol Co ...

states that "''Panta rhei'', 'everything flows' is probably the most familiar of Heraclitus' sayings, yet few modern scholars think he said it." Barnes observes that although the ''exact'' phrase is not ascribed to Heraclitus until the 6th century by Simplicius of Cilicia

Simplicius of Cilicia (; el, Σιμπλίκιος ὁ Κίλιξ; c. 490 – c. 560 AD) was a disciple of Ammonius Hermiae and Damascius, and was one of the last of the Neoplatonists. He was among the pagan philosophers persecuted by Justinian i ...

, a similar saying representing the same theory, ''panta chorei'', or "everything moves" is ascribed to Heraclitus by Plato in the ''Cratylus

Cratylus ( ; grc, Κρατύλος, ''Kratylos'') was an ancient Athenian philosopher from the mid-late 5th century BCE, known mostly through his portrayal in Plato's dialogue '' Cratylus''. He was a radical proponent of Heraclitean philosophy ...

''.

Since Plato, Heraclitus's theory of Flux has been associated with the metaphor of a flowing river, that which cannot be stepped into twice. This fragment from Heraclitus's writings has survived in three different forms: The German classicist and philosopher interprets the metaphor as illustrating what is stable, rather than the usual interpretation of illustrating change. "You will not find anything, in which the river remains constant ... Just the fact, that there is a particular river bed, that there is a source and an estuary etc. is something, that stays identical. And this is ... the concept of a river." There, Heraclitus claims we can not step into the same river twice, a position summarized with the slogan ''ta panta rhei'' (everything flows). One fragment reads: "Into the same rivers we both step and do not step; we both are and are not" ). Heraclitus is seemingly suggesting that not only the river is constantly changing, but we do as well, even hinting at existential questions about humankind.

Cosmology

Like the Milesians before him,

Like the Milesians before him, Thales

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded him ...

with water, Anaximander

Anaximander (; grc-gre, Ἀναξίμανδρος ''Anaximandros''; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 1, p. 403. a city of Ionia (in moder ...

with apeiron

''Apeiron'' (; ) is a Greek word meaning "(that which is) unlimited," "boundless", "infinite", or "indefinite" from ''a-'', "without" and ''peirar'', "end, limit", "boundary", the Ionic Greek form of ''peras'', "end, limit, boundary".

Origin ...

, and Anaximenes with air, Heraclitus was considered by Aristotle to have fire as the ''Arche

''Arche'' (; grc, ἀρχή; sometimes also transcribed as ''arkhé'') is a Greek word with primary senses "beginning", "origin" or "source of action" (: from the beginning, οr : the original argument), and later "first principle" or "element". ...

'', the fundamental element that gave rise to the other elements. In one fragment, Heraclitus writes: ''This world-order osmos

''Osmos'' is a 2009 puzzle video game developed by Canadian developer Hemisphere Games for various systems such as Microsoft Windows, Mac OS X, Linux, OnLive, iPad, iPhone, iPod Touch and Android.

Gameplay

The aim of the game is to propel o ...

the same of all, no god nor man did create, but it ever was and is and will be: everliving fire, kindling in measures and being quenched in measures''. From fire all things originate and all things return to it again in a process of eternal cycles. Heraclitus regarded the soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun ''soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest attes ...

as a mixture of fire and water, and that fire is the noble part of the soul and water is the ignoble part, and he considered mastery of one's worldly desires to be a noble pursuit that purified the soul's fire. These everlasting modifications explain his view that the cosmos ''was and is and will be''.

Heraclitus' description of a doctrine of purification of fire has also been investigated for influence from the Zoroastrian

Zoroastrianism is an Iranian religion and one of the world's oldest organized faiths, based on the teachings of the Iranian-speaking prophet Zoroaster. It has a dualistic cosmology of good and evil within the framework of a monotheistic on ...

concept of ''Atar

Atar, Atash, or Azar ( ae, 𐬁𐬙𐬀𐬭, translit=ātar) is the Zoroastrian concept of holy fire, sometimes described in abstract terms as "burning and unburning fire" or "visible and invisible fire" (Mirza, 1987:389). It is considered to b ...

''. Many of the doctrines of Zoroastrian fire do not match exactly with those of Heraclitus, such as the relation of fire to earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, but he may have taken some inspiration from them. Zoroastrian parallels to Heraclitus are often difficult to identify specifically due to a lack of surviving Zoroastrian literature from the period and mutual influence with Greek philosophy; the 9th century CE Dadestan i Denig preserves information on Zoroastrian cosmology, but also shows direct borrowings from Aristotle. The interchange of other elements with fire also has parallels in Vedic literature from the same time period, such as the Kaushitaki Upanishad and Taittiriya Upanishad

The Taittirīya Upanishad (Devanagari: तैत्तिरीय उपनिषद्) is a Vedic era Sanskrit text, embedded as three chapters (''adhyāya'') of the Yajurveda. It is a ''mukhya'' (primary, principal) Upanishad, and likely co ...

. and West stresses that these doctrines of the interchange of elements were common throughout written work on philosophy that has survived from that period, so Heraclitus' doctrine of fire can not be definitively be said to have been influenced by any other particular Iranian or Indian influence, but may have been part of a mutual interchange of influence over time across the Ancient Near East.

The phrase ''Ethos anthropoi daimon'' ("man's character is isfate") attributed to Heraclitus has led to numerous interpretations, and might mean one's luck is related to one's character. The translation of ''daimon'' in this context to mean "fate" is disputed; according to Thomas Cooksey, it lends much sense to Heraclitus's observations and conclusions about human nature in general. While the translation as "fate" is generally accepted as in Charles Kahn's "a man's character is his divinity."

A fundamental term in Heraclitus is ''logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, wikt:λόγος, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive ...

'', an ancient Greek word with a variety of meanings; Heraclitus might have used a different meaning of the word with each usage in his book. ''Logos'' seems like a universal law that unites the cosmos, according to a fragment: "Listening not to me but to the logos, it is wise to agree (homologein) that all things are one." While ''logos'' is everywhere, very few people are familiar with it. Another fragment reads: oi polloi"...do not know how to listen o Logos

O, or o, is the fifteenth Letter (alphabet), letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the English alphabet, modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in ...

or how to speak he truth

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (pronoun), an English pronoun

* He (kana), the romanization of the Japanese kana へ

* He (letter), the fifth letter of many Semitic alphabets

* He (Cyrillic), a letter of the Cyrillic script called ''He'' in ...

Heraclitus' thought on ''logos'' influenced the Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

, who referred to him to support their belief that rational law governs the universe.

Although many of the later Stoics interpreted Heraclitus as having a " logos-doctrine" where the "logos" was a first principle

In philosophy and science, a first principle is a basic proposition or assumption that cannot be deduced from any other proposition or assumption.

First principles in philosophy are from First Cause attitudes and taught by Aristotelians, and nua ...

that ran through all things, West observes that Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; grc-gre, Θεόφραστος ; c. 371c. 287 BC), a Greek philosopher and the successor to Aristotle in the Peripatetic school. He was a native of Eresos in Lesbos.Gavin Hardy and Laurence Totelin, ''Ancient Botany'', Routledge ...

, and Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and ...

all make no mention of this doctrine, and concludes that the language and thought are "obviously Stoic" and not attributable to Heraclitus. Kahn stresses that Heraclitus used the word in multiple senses and Guthrie observes that there is no evidence Heraclitus used it in a way that was significantly different from that in which it was used by contemporaneous speakers of Greek. Guthrie considers the ''Logos'' as a public fact like a proposition

In logic and linguistics, a proposition is the meaning of a declarative sentence. In philosophy, " meaning" is understood to be a non-linguistic entity which is shared by all sentences with the same meaning. Equivalently, a proposition is the no ...

or formula

In science, a formula is a concise way of expressing information symbolically, as in a mathematical formula or a ''chemical formula''. The informal use of the term ''formula'' in science refers to the general construct of a relationship betwee ...

, though he admits that Heraclitus would not have considered these facts as abstract objects

In metaphysics, the distinction between abstract and concrete refers to a divide between two types of entities. Many philosophers hold that this difference has fundamental metaphysical significance. Examples of concrete objects include plants, hum ...

or immaterial

Immaterial may refer to:

* The opposite of matter, material, materialism, or materialistic

* Maya (illusion), a concept in all Indian religions, that all matter is a grand illusion

* Incorporeality

* Immaterialism, including subjective idealism ...

things.

Although the early Christian philosophers, following the Stoics, interpreted the logos in terms of a personal God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

, modern scholars do not believe these associations are represented in the original thought of Heraclitus. When Heraclitus speaks of "God" he does not mean a single deity as an omnipotent and omniscient or God as Creator, the universe being eternal; he meant the divine as opposed to human, the immortal as opposed to the mortal and the cyclical as opposed to the transient; to him, it is arguably more accurate to speak of "the Divine" and not of "God".

Legacy

Heraclitus' writings have exerted a wide influence on

Heraclitus' writings have exerted a wide influence on Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

, including the works of Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

. Parmenides

Parmenides of Elea (; grc-gre, Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia.

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family. His dates a ...

is generally agreed to either have influenced or have been influenced by him, either as an influence or response to Heraclitean doctrines, or as an extension of them. Some of the writings in Hippocratic corpus

The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: ''Corpus Hippocraticum''), or Hippocratic Collection, is a collection of around 60 early Ancient Greek medical works strongly associated with the physician Hippocrates and his teachings. The Hippocratic Corpus cove ...

also shows signs of Heraclitean themes, as do some of the surviving fragments of other pre-Socratic philosophers including Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the fo ...

and Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

. The sophists such as Protagoras

Protagoras (; el, Πρωταγόρας; )Guthrie, p. 262–263. was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher and rhetorical theorist. He is numbered as one of the sophists by Plato. In his dialogue '' Protagoras'', Plato credits him with inventing the r ...

may also have been influenced by Heraclitus. Many of the later Stoic, Cynic, and Skeptical philosophers also interpreted Heraclitus in terms of their own doctrines. In modern times, Heraclitus has also been seen as a process philosopher due to the influence of G.W.F. Hegel and Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centur ...

, and a potential source for understanding the Ancient Greek religion

Religious practices in ancient Greece encompassed a collection of beliefs, rituals, and mythology, in the form of both popular public religion and cult practices. The application of the modern concept of "religion" to ancient cultures has been ...

since the discovery of the Derveni papyrus

The Derveni papyrus is an ancient Greek papyrus roll that was found in 1962. It is a philosophical treatise that is an allegorical commentary on an Orphic poem, a theogony concerning the birth of the gods, produced in the circle of the philosopher ...

.Flux and the unchanging universe of Parmenides

It is unknown whether or not Heraclitus had any students in his lifetime. Diogenes Laertius mentions an Antisthenes who wrote a commentary on Heraclitus.

Parmenides, an

It is unknown whether or not Heraclitus had any students in his lifetime. Diogenes Laertius mentions an Antisthenes who wrote a commentary on Heraclitus.

Parmenides, an Eleatic

The Eleatics were a group of pre-Socratic philosophers in the 5th century BC centered around the ancient Italian Greek colony of Elea ( grc, Ἐλέα), located in present-day Campania in southern Italy.

The primary philosophers who are associat ...

philosopher who was a near-contemporary of Heraclitus, proposed a doctrine of changelessness, which has been contrasted with the doctrine of flux put forth by Heraclitus. Different philosophers have argued that either one of them may have substantially influenced each other, some taking Heraclitus to be responding to Parmenides, others that Parmenides is responding to Heraclitus, and some arguing that any direct chain of influence between the two is impossible to determine. Although Heraclitus refers to older figures such as Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos ( grc, Πυθαγόρας ὁ Σάμιος, Pythagóras ho Sámios, Pythagoras the Samos, Samian, or simply ; in Ionian Greek; ) was an ancient Ionians, Ionian Ancient Greek philosophy, Greek philosopher and the eponymou ...

, neither Parmenides or Heraclitus directly refer to each other in any surviving fragments, so any speculation on influence must be based on interpretations of the surviving fragments.Impermenance in Plato's Cratylus

Plato is the most famous philosopher who tried to reconcile Heraclitus and Parmenides; through Plato, both of these figures influenced virtually all subsequent Western philosophy. According to Aristotle, Plato knew of the teachings of Heraclitus through his followerCratylus

Cratylus ( ; grc, Κρατύλος, ''Kratylos'') was an ancient Athenian philosopher from the mid-late 5th century BCE, known mostly through his portrayal in Plato's dialogue '' Cratylus''. He was a radical proponent of Heraclitean philosophy ...

, who went a step beyond his master's doctrine and said one cannot step into the same river once Plato presented Cratylus as a linguistic naturalist , one who believes names must apply naturally to their objects. According to Aristotle, Cratylus took the view nothing can be said about the ever-changing world and "ended by thinking that one need not say anything, and only moved his finger". Cratylus may have thought continuous change warrants skepticism because one cannot define a thing that does not have a permanent nature.

Logos in Stoicism and early Christianity

TheStoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

believed major tenets of their philosophy derived from the thought of Heraclitus, including a commentary by Cleanthes

Cleanthes (; grc-gre, Κλεάνθης; c. 330 BC – c. 230 BC), of Assos, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and boxer who was the successor to Zeno of Citium as the second head ('' scholarch'') of the Stoic school in Athens. Originally a boxe ...

which has not survived. In surviving stoic writings, this is most evident in the writings of Marcus Aurelius. Explicit connections of the earliest Stoics to Heraclitus showing how they arrived at their interpretation are missing, but they can be inferred from the Stoic fragments, which Long concludes are "modifications of Heraclitus". Heraclitus states, "We should not act and speak like children of our parents", which Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

interpreted to mean one should not simply accept what others believe. Marcus Aurelius understood the ''Logos'' as "the account which governs everything", but Burnet cautions that these modifications of Heraclitus in the Stoic fragments make it harder to use the fragments to interpret Heraclitus himself, as the Stoics ascribed their own interpretations of terms like "logos" and "ekpyrosis" to Heraclitus. The Cynics were also influenced by Heraclitus, attributing several of the later Cynic epistles

The Cynic epistles are a collection of letters expounding the principles and practices of Cynic philosophy mostly written in the time of the Roman empire but purporting to have been written by much earlier philosophers.

Letters and dating

The tw ...

to his authorship.

Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome (, ; c. 170 – c. 235 AD) was one of the most important second-third century Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communities include Rome, Palestin ...

, one of the early Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

of the Christian Church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a synonym fo ...

identified Heraclitus along with the other Pre-Socratics

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of thes ...

and Platonic Academy, Academics as sources of heresy, and identified the logos as meaning the Christian "Word of God", such as in John 1:1, "In the beginning was the Word (''logos'') and the Word was God"; however, modern scholars such as John Burnet viewed the relationship between Heraclitean logos and Johannine logos as fallacious, saying; "the Johannine doctrine of the logos has nothing to do with Herakleitos or with anything at all in Greek philosophy, but comes from the Hebrew Wisdom literature". The Christian apologist Justin Martyr took a more positive view of Heraclitus. In his First Apology, he said both Socrates and Heraclitus were Christians before Christ: "those who lived reasonably are Christians, even though they have been thought atheists; as, among the Greeks, Socrates and Heraclitus, and men like them".Dialectic in Pyrrhonic skepticism

Aenesidemus, one of the major ancient Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosophers, claimed in a now-lost work that Pyrrhonism was a way to Heraclitean philosophy because Pyrrhonist practice helps one to see how opposites appear to be the case about the same thing. Once one sees this, it leads to understanding the Heraclitean view of opposites being the case about the same thing. A later Pyrrhonist philosopher,Sextus Empiricus

Sextus Empiricus ( grc-gre, Σέξτος Ἐμπειρικός, ; ) was a Ancient Greece, Greek Pyrrhonism, Pyrrhonist philosopher and Empiric school physician. His philosophical works are the most complete surviving account of ancient Greek and ...

, disagreed, arguing opposites' appearing to be the case about the same thing is not a dogma of the Pyrrhonists but a matter occurring to the Pyrrhonists, to the other philosophers, and to all of humanity.

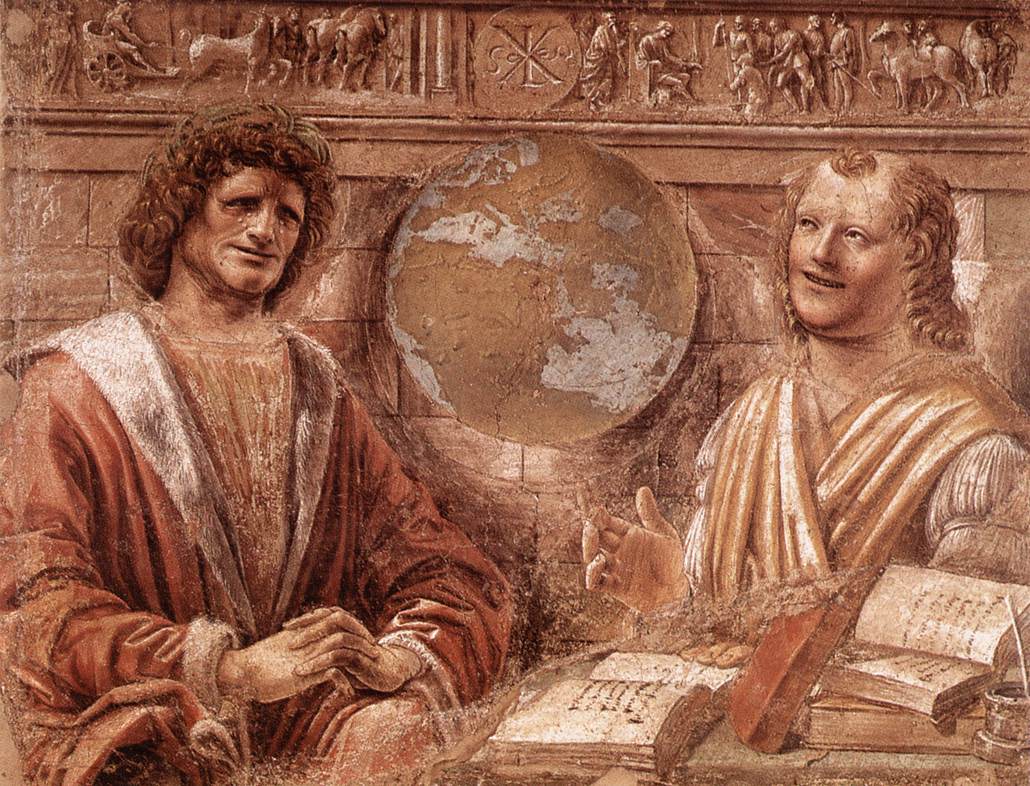

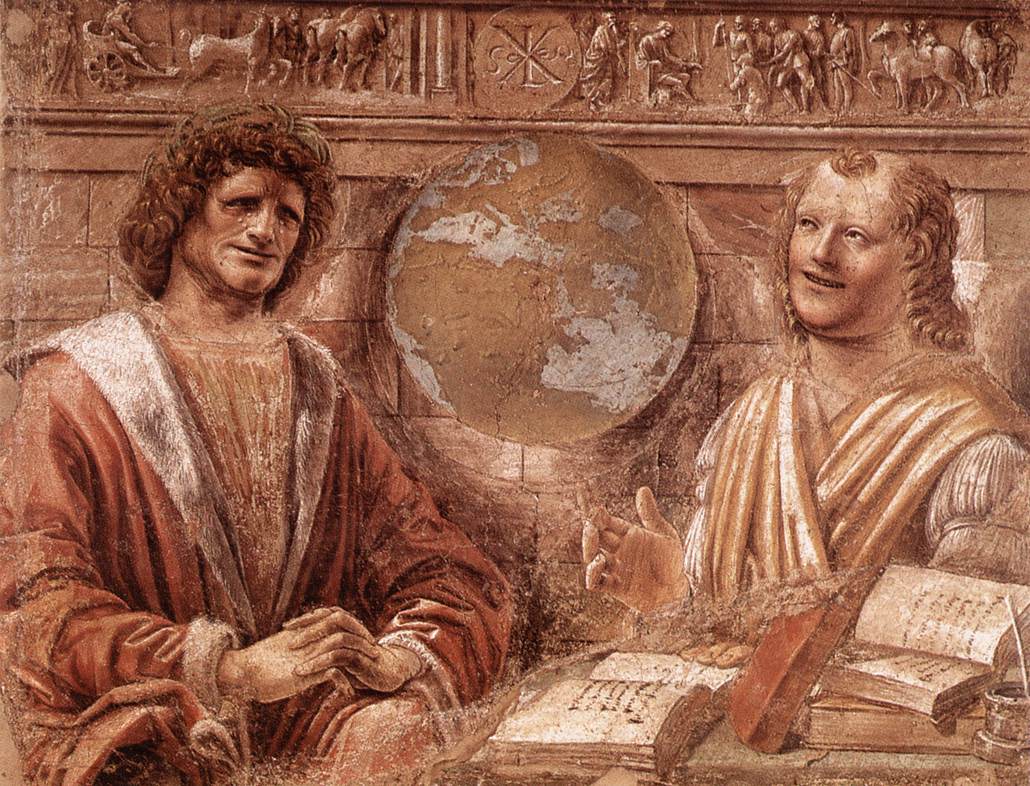

Weeping philosopher

In Lucian, Lucian of Samosata's "Philosophies for Sale," Heraclitus is auctioned off as the "weeping philosopher" alongsideDemocritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

, who is known as the "laughing philosopher" part of the weeping and laughing philosopher motif. This pairing, which may have originated with the Cynic philosopher Menippus, has been portrayed several times in renaissance art, where it generally references their reactions to the folly of mankind. Heraclitus also appears in Raphael's ''School of Athens.''

Modern Reception

Heraclitus has been the subject of numerous interpretations. According to the ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'', Heraclitus has been seen as a "Material monism, material monist or a process philosophy, process philosopher; a scientific cosmologist, a Metaphysics, metaphysician and a religious thinker; an empiricism, empiricist, a rationalism, rationalist, a mysticism, mystic; a conventional thinker and a revolutionary; a developer of logic — one who denied the law of non-contradiction; the first genuine philosopher and an Anti-intellectualism, anti-intellectual Obscurantism, obscurantist." G.W.F. Hegel interpreted Heraclitus as a Process philosophy, process philosopher, seeing the "becoming" in Heraclitus as a natural result of the ontology of "being" and "non-being" in Parmenides.Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger (; ; 26 September 188926 May 1976) was a German philosopher who is best known for contributions to phenomenology, hermeneutics, and existentialism. He is among the most important and influential philosophers of the 20th centur ...

was also influenced by Heraclitus, as seen in his Introduction to Metaphysics (Heidegger), ''Introduction to Metaphysics''. Heidegger believed that the thinking of Heraclitus and Parmenides was the origin of philosophy and misunderstood by Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

and Aristotle, leading all of Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

astray.W. Julian Korab-Karpowicz, ''The Presocratics in the Thought of Martin Heidegger'' (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2016), page 58.

Notes

Explanatory Notes

Fragment Numbers

Citations

References

Ancient Testimony

In the Diels-Kranz numbering for testimony and fragments of Pre-Socratic philosophy, Heraclitus is catalogued as number 22. The most recent edition of this catalogue is *.Life and Doctrines

*A1. *A2. *A3. *A4. * A5. * A6. * A5. * A8. * A9. * A10. * A11-14. * A15. * A16. * A17. * A18. * A19. * A20. * A21. * A22. * A23.Fragments

*B1-2. *B3. *B4. *B5. *B6. *B7. *B8-9. *B10-11. *B12. *B13. *B14-15. *B16. *B17-36. *B37. *B38. *B39. *B40-46. *B47. *B49. *B49a. *B50-67. *B67a. *B68-69. *B70. *B71-75. *B78-80. *B81. *B82-83. *B84a-84b. *B85-86. *B87. *B88. *B89. *B90-91. *B92-93. *B94. *B95-96. *B97. *B98. *B99. *B100. *B101. *B101a. *B104. *B106. *B107.Imitation

*C1. *C2. *C4. *C5.Modern Scholarship

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * Chapters 4-6 deal with HeraclitusFurther reading

* * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* * * {{Authority control Heraclitus, 6th-century BC Greek people 6th-century BC philosophers 5th-century BC Greek people 5th-century BC philosophers 530s BC births 470s BC deaths Ancient Ephesians Ancient Greek cosmologists Ancient Greek ethicists Ancient Greek metaphilosophers Ancient Greek metaphysicians Ancient Greek physicists Ancient Greeks from the Achaemenid Empire Deaths from edema Ancient Greek epistemologists Founders of philosophical traditions Moral philosophers Natural philosophers Ontologists Philosophers of ancient Ionia Philosophers of ethics and morality Ancient Greek philosophers of mind Philosophers of religion Philosophers of time Ancient Greek political philosophers Presocratic philosophers